- Research Briefs

- Articles for Practitioners

- Lessons from Practice

Research Grants

- Upcoming events

- Past Events

- GATE Newsletter

- Multimedia Resources

- MBA Student Fellows and Interns

- Student Clubs

- Courses and training

- Case Studies

- Stories of impact

- Supporting GATE

- Our Partners

- Search for:

To support rigorous research, GATE offers annual research grants to qualified applicants.

2023-2024 grant recipients.

Gender Differences in Job Application Strategies: An Experimental Investigation

The Promise of Ranked-Choice Voting: Can It Improve Diversity?

Gendered Patterns in the Language that Experts Use in their Endorsements

The Impact of Registered Indian Status: Evidence from Bill C-31

The Effect of Federal Fair Lending Regulations on Sexual Orientation Discrimination in the Mortgage Market

Revolutionary Care: Technology Use in Precarious Care Work

Gender-Based Price Discrimination: An Antitrust Concern?

Where Does Creativity Come From? How the Gendered Nature of Creativity Beliefs Impacts Organizational Recruiting

Quantifying and Understanding Gender Disadvantages in Reactions to Incorrect Teaching

Female Economic Immigrants Driven Out of Japan Due to Gender Inequality: Exploring their Economic Integration in Canada

How Marginalized Actors Develop New Market Strategies After Institutional Reform

Regulating Biases: The Impact of Anti-Discriminating Policies on Firms

Gender Inequality and Household Purchase Decisions: The Case of Automobiles in China

2022-2023 Grant Recipients

Gender Differences in Accusations and Believability

Promoting Economic Inclusion among Racialized Migrant Women

Gender Discrimination in Remote and On-Site Work: A Survey of Managers’ Perceptions

Strengthening the investment case for action on gender-based violence and child maltreatment in Canada

2021-2022 Grant Recipients

Read about their research in VoxDev .

2020-2021 Grant Recipients

Read Rie's paper in International Journal of STEM Education .

Read gate's brief on rie's research., learn more in this article on biomed central ..

2019-2020 Grant Recipients

Read their paper in Cognitive Science .

Read András' paper in American Sociological Review .

Read gate's research brief on andrás' research., 2018-2019 grant recipients.

Salary disclosure laws and the gender wage gap

Read their paper in American Economic Journal .

Learn more about this research in harvard business review ..

Choice architecture and women’s leadership ascension

Read their paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences .

Read gate's research brief of their paper., learn more about joyce, sonia, and nico's research in voxeu..

Read their latest working paper.

Read their paper in Journal of Business Ethics .

Read their paper in Labour Economics .

Read gate's research brief on their paper..

View a short film based on their research here.

2017-2018 grant recipients.

Impact on the gender pay gap of CEO exposure to gender imbalance during formative years

Read Mikhail's publication in The Review of Financial Studies .

Watch mikhail discuss his research at the rotman magazine event, "art of change.".

Scaling Up Gender Equality (how different ratings scales shape outcomes by gender)

Winner, American Sociological Association Granovetter Award for best article in economic sociology.

Learn more about András' research in this article for Harvard Business Review.

Read gate's research brief on andrás' paper..

Race, Gender and Agency in Leadership: An Examination of Intersectional Identities and Agentic Penalties

Adding More Women to Corporate Boards: The Impact on Boards’ Advisory Effectiveness

Read Daehyun's paper in American Economic Review .

Read an interview about this research in forbes india ..

Playing the Inside Game versus the Outside Offer Game: How Men and Women Respond to Workplace Successes and Failures May Drive the Gender Pay Gap

Shifting Stereotypes to Improve Leadership Aspiration and Self‐Efficacy among Female Leaders

Read their paper in Academy of Management .

Learn more about this research in ucla anderson review ..

Barriers to Reporting Sexual Harassment and Assault

Gender and Awards in Financial Industries

We’re talking about

Since its launch in 2016, GATE has funded 61 researchers investigating topics such as the impact of CEO characteristics on the corporate gender gap, barriers to reporting sexual harassment and assault, increasing the number of girls and women pursuing STEM careers, and the double-bind that women face in entering the job market and advancing in their careers.

- Events & Workshops

- Funding Opportunities

- SCORE Program

- In The News

- SCORE Seed Grant in Sex & Gender Differences

- The BIRCWH Program

Funding Opportunities for Women’s Health and Gender Research

Pilot grants and research funding.

An important part of the Center’s mission is to serve as a resource for funding in women's health, sex, and gender differences research.

Need help writing a grant?

Get Funding Through the SADII SCORE

The Johns Hopkins Sex and Age Differences in Immunity to Influenza (SADII) is part of the Specialized Centers of Research Excellence (SCORE) on Sex Differences program , a signature program of the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health(ORWH).

BIRCWH Funding for Johns Hopkins Junior Faculty

The Johns Hopkins Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (JH-BIRCWH) was established to develop highly qualified, independent investigators to conduct women’s health and sex and gender differences research. Meet our BIRCHW scholars and explore their work.

Funding is available only to full-time junior faculty scholars from within Johns Hopkins University, with priority given to investigators from groups underrepresented in research.

More Women’s Health Grants and Funding Opportunities

Funding for research projects in women’s health, gender-based differences, and sex-based biology is available from institutions inside and outside the Johns Hopkins community.

- Maternal and Child Health Bureau Research Program

- The NIH Guide to Grants and Contracts.

- Funding from Johns Hopkins ICTR

- Seed Grants for Research on Sex/Gender Differences in Medicine and Public Health

- Society for Women’s Health Research

- Susan G. Komen for the Cure

- Epilepsy Foundation

- Research Webnotes: External and Internal Funding and Prizes

Gender Disparity in the Funding of Diseases by the U.S. National Institutes of Health

Affiliation.

- 1 Independent Researcher, Castro Valley, California, USA.

- PMID: 33232627

- PMCID: PMC8290307

- DOI: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8682

Background: Gender bias has been an ongoing issue in health care, examples being underrepresentation of women in health studies, trivialization of women's physical complaints, and discrimination in the awarding of research grants. We examine here a different issue-gender disparity when it comes to the allocation of research funding among diseases. Materials and Methods: We perform an analysis of funding by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) to ascertain possible gender disparity in its allocation of funds across diseases. We normalize funding level to disease burden, as measured by the Disability Adjusted Life Year, and we specifically consider diseases for which both disease burden and funding level are provided. We apply a power-law regression analysis to model funding commensurate with disease burden. Results: We find that in nearly three-quarters of the cases where a disease afflicts primarily one gender, the funding pattern favors males, in that either the disease affects more women and is underfunded (with respect to burden), or the disease affects more men and is overfunded. Moreover, the disparity between actual funding and that which is commensurate with burden is nearly twice as large for diseases that favor males versus those that favor females. A chi-square test yields a p -value of 0.015, suggesting that our conclusions are representative of the full NIH disease portfolio. Conclusions: NIH applies a disproportionate share of its resources to diseases that affect primarily men, at the expense of those that affect primarily women.

Keywords: National Institutes of Health; gender disparity; research funding for diseases.

- Biomedical Research*

- Cost of Illness

- National Institutes of Health (U.S.)

- Quality-Adjusted Life Years

- United States

Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University

Policy Careers May 2, 2019

How big is the gender gap in science research funding, two new studies look at who wins the prestigious grants and prizes that can make or break a scientist’s career..

Diego FM Oliveira

Teresa Woodruff

Women are entering the biomedical sciences in record rates. But what happens to these female doctors and scientists once they’re established in their careers? Do they receive the same support as their male colleagues?

In several key ways, according to new research, they don’t. Women biomedical researchers receive less grant funding from the National Institute of Health (NIH) and less prize money when they win scientific awards. That’s the conclusion from two related papers from Brian Uzzi , a professor of management and organizations at the Kellogg School, and Teresa K. Woodruff , a professor at Northwestern’s Fienberg School of Medicine and Northwestern’s associate provost for graduate education. These findings may not surprise anyone familiar with the overall gender wage gap. But Woodruff says it was important to quantify the disparity. “Having the data allows us to understand root causes and allows us to understand intervention,” she says.

The sobering results may also help explain why women are still underrepresented in top scientific positions—despite earning PhDs at historically high levels. Women researchers are at a fiscal disadvantage, Woodruff says, “from the very beginning, from the very first grant.” That, in turn, may limit their ability to do the cutting-edge research that would allow them to advance. Uzzi agrees. The study on prize money, he says, shows another way that women don’t receive “equal recognition for their contributions. That tends to lower motivation, and it tends to have women look to other fields where their contributions will be better acknowledged and better rewarded.”

Measuring the Funding Gender Gap

Grants are the lifeblood of biomedical research, and there is no more important funding source than the NIH, which invests nearly $40 billion each year . The first grant that scientists receive from the federal agency can help start their career on the right track. That’s why Woodruff and Uzzi, along with and Yifang Ma, a postdoctoral fellow at the Northwestern Institute on Complex Systems , and Diego F. M. Oliveira, a scientist at the Army Research Lab, decided to analyze NIH grants to first-time principal investigators (PIs), who are the lead researchers on a project. After analyzing more than 53,000 grants awarded between 2006 and 2017, they found that the median grant size for first-time female PIs was $126,615. That’s a striking 24 percent less than the $165,721 awarded to first-time male PIs.

“What’s important to me is that we continue to develop the strategies that will ensure that tomorrow’s female faculty succeeds more easily than my generation.” —Teresa Woodruff

The team still isn’t sure why the disparity exists. As part of their study they examined potentially confounding factors such as the quantity of papers the researchers had published, citations their papers received, and topics the researchers studied. But there was no systemic difference in those numbers that could explain why first-time female PIs ultimately got smaller grants. They also analyzed Big Ten and Ivy League universities separately, thinking that institutional prestige or school-specific factors, like grant-application advice or overhead charges, could affect levels of grant funding. In both instances, they still found a significant gender disparity—a median difference in grants between men and women of $81,711 at Big Ten schools and $19,513 in the Ivy League, with some schools showing no differences and other schools showing differences of up to 66 percent. Restricting the analysis to men and women applying for the same grant, which controlled for grant budget and length, also showed that the discrepancies by gender persisted on average—although like the analysis at the institutional level, the difference in funding amounts was concentrated in certain grants. Woodruff says the team is trying to get to the bottom of the issue. They are examining the possibility that women are simply asking for less, although she doesn’t think that’s likely. It could be that women aren’t getting the right kind of support from their home institutions—such as lab space—that would make for a more compelling grant application. Unconscious bias at the NIH could also be to blame.

Whatever the reason, it’s essential that it be addressed so that women and men can move through their career on equal footing. Now that scientists know about the funding disparity, “we’re all going to be able to look at our own areas and see what we can come up with as ways to intervene,” Woodruff says.

Prize Money: Even When Women Win, They Lose

Unfortunately, funding disparities don’t go away as women advance in their career. This was the takeaway from Uzzi and Woodruff’s second study, which focused on prize money that biomedical researchers receive for industry awards. This line of research was sparked by some online book browsing. Uzzi, a fan of mixed martial arts, stumbled across a book called Prize Fights on Amazon, only to discover it was actually about research prizes. “That’s how it happens sometimes in science,” he says. Prizes are the “coin of the realm in science in terms of recognition for your work,” he says. “Deans and promotion committees all pay attention to the kind of prizes you have, because they really highlight and draw awareness to the quality of your work.” The team collected data on 628 prizes awarded in the biomedical sciences from 1968 to 2017. These included prominent prizes for research, as well as prizes for professional service, such as teaching and mentoring.

There were some encouraging results: between 2007 and 2017, women won 27 percent of prizes. This is a major improvement from 1968 to 1977, when women received just 5 percent of prizes, and is about what you’d expect, given that 31 percent of papers in the field have at least one female author. But even when women win prizes, they lose. That’s because women do not tend to win the most prestigious and lucrative prizes, the group found. In fact, women made up just 14.6 percent of winners of the top five percent of prizes.

Overall, women won an average of 64.4 cents of the prize money for every dollar men received. If you exclude the most and least lucrative prizes to avoid outliers, the picture looks even bleaker: on average, women receive just 60.2 cents for every dollar men win. That amount, Uzzi says, could make the difference between “a thriving lab or a lab that is always choked for money,” since researchers often funnel prize money into their labs, and the prestige of a prize can attract other funding, as well.

“Deans and promotion committees all pay attention to the kind of prizes you have.” —Brian Uzzi

Interestingly, women are winning more service prizes than men, the analysis found. But these prizes, which are awarded for things such as working on committees or mentoring students, while critical to science, are both less remunerative and less highly regarded than research prizes. That suggests female scientists are doing more than their fair share of service, and perhaps paying a price for it. “If you’re spending your time doing a lot of service, it drains time away that you would spend on your research,” Uzzi says.

From Research to Intervention

Now that they have named and quantified the scale of the problem, Uzzi and Woodruff hope to identify solutions. And they aren’t alone. They’ve already heard from a member of the Nobel Prize committee who wanted to know how they could change their nomination process so that more women are in contention. For its part, the NIH issued a statement that said it’s “aware and concerned” about the disparity in funding between men and women researchers. “What’s important to me is that we continue to develop the strategies that will ensure that tomorrow’s female faculty succeeds more easily than my generation,” Woodruff says. “If we can put into place [a system] that allows my students who are now becoming faculty to actually have a fair shake at the economics that allow us to make the discoveries that are necessary to all of our lives, then we will have done a good thing.”

Richard L. Thomas Professor of Leadership and Organizational Change; Professor of Management and Organizations

About the Writer Susie Allen is a freelance writer in Chicago.

About the Research Uzzi, Brian, Diego FM Oliveira, Yifang Ma, and Teresa Woodruff. 2019. “Comparison of National Institutes of Health Grant Amounts to First-Time Male and Female Principal Investigators.” Journal of the American Medical Association. 321(9): 898–900. Ma, Yifang, Teresa Woodruff, and Brian Uzzi. 2019. “Women Who Win Prizes Get Less Money and Prestige." Nature. 565: 287–288.

Fund for Gender Equality

The Fund for Gender Equality (FGE) has one guiding purpose: to support national, women-led civil society organizations in achieving women’s economic and political empowerment and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

An instrument for feminist philanthropy based on principles of accessibility, trust, and women’s ownership, the Fund is a unique global grant-making model . It transforms financing from diverse donors into high-impact initiatives by women-led organizations, investing in their ideas and abilities to pursue interventions closely attuned to women and girls left furthest behind —97 per cent of its projects working with at least one category of vulnerable groups, and 70 per cent involving two or more.

Since its creation in 2009, the Fund has strengthened the capacities of 131 organizations and delivered USD 65 million in grants to 121 projects in 80 countries. Projects have directly improved the lives of 570,000 people and benefitted millions more through lasting changes to public policy.

To maintain the highest standards of quality and impact, the Fund constantly learns from past experiences while looking ahead and exploring new ways of working . With select grantees, it is currently experimenting with alternative grant-making approaches involving upscaling and social innovation .

In this section

Featured publication

Fund for Gender Equality annual report 2018–2019 Supported by photos, data, infographics, and individual stories of impact, UN Women's Fund for Gender Equality (FGE) annual report presents main aggregated results achieved by its 25 active projects. It highlights the process and outcomes of its fourth grant-making cycle, 2018–2019, a scaling and innovation initiative. The report also features FGE’s South-South and triangular cooperation strategy, a few impact news from past projects, and two grantee partners’ op-eds. More

Featured video

- ‘One Woman’ – The UN Women song

- UN Under-Secretary-General and UN Women Executive Director Sima Bahous

- Kirsi Madi, Deputy Executive Director for Resource Management, Sustainability and Partnerships

- Nyaradzayi Gumbonzvanda, Deputy Executive Director for Normative Support, UN System Coordination and Programme Results

- Guiding documents

- Report wrongdoing

- Programme implementation

- Career opportunities

- Application and recruitment process

- Meet our people

- Internship programme

- Procurement principles

- Gender-responsive procurement

- Doing business with UN Women

- How to become a UN Women vendor

- Contract templates and general conditions of contract

- Vendor protest procedure

- Facts and Figures

- Global norms and standards

- Women’s movements

- Parliaments and local governance

- Constitutions and legal reform

- Preguntas frecuentes

- Global Norms and Standards

- Macroeconomic policies and social protection

- Sustainable Development and Climate Change

- Rural women

- Employment and migration

- Facts and figures

- Creating safe public spaces

- Spotlight Initiative

- Essential services

- Focusing on prevention

- Research and data

- Other areas of work

- UNiTE campaign

- Conflict prevention and resolution

- Building and sustaining peace

- Young women in peace and security

- Rule of law: Justice and security

- Women, peace, and security in the work of the UN Security Council

- Preventing violent extremism and countering terrorism

- Planning and monitoring

- Humanitarian coordination

- Crisis response and recovery

- Disaster risk reduction

- Inclusive National Planning

- Public Sector Reform

- Tracking Investments

- Strengthening young women's leadership

- Economic empowerment and skills development for young women

- Action on ending violence against young women and girls

- Engaging boys and young men in gender equality

- Leadership and Participation

- National Planning

- Violence against Women

- Access to Justice

- Regional and country offices

- Regional and Country Offices

- Liaison offices

- UN Women Global Innovation Coalition for Change

- Commission on the Status of Women

- Economic and Social Council

- General Assembly

- Security Council

- High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development

- Human Rights Council

- Climate change and the environment

- Other Intergovernmental Processes

- World Conferences on Women

- Global Coordination

- Regional and country coordination

- Promoting UN accountability

- Gender Mainstreaming

- Coordination resources

- System-wide strategy

- Focal Point for Women and Gender Focal Points

- Entity-specific implementation plans on gender parity

- Laws and policies

- Strategies and tools

- Reports and monitoring

- Training Centre services

- Publications

- Government partners

- National mechanisms

- Civil Society Advisory Groups

- Benefits of partnering with UN Women

- Business and philanthropic partners

- Goodwill Ambassadors

- National Committees

- UN Women Media Compact

- UN Women Alumni Association

- Editorial series

- Media contacts

- Annual report

- Progress of the world’s women

- SDG monitoring report

- World survey on the role of women in development

- Reprint permissions

- Secretariat

- 2023 sessions and other meetings

- 2022 sessions and other meetings

- 2021 sessions and other meetings

- 2020 sessions and other meetings

- 2019 sessions and other meetings

- 2018 sessions and other meetings

- 2017 sessions and other meetings

- 2016 sessions and other meetings

- 2015 sessions and other meetings

- Compendiums of decisions

- Reports of sessions

- Key Documents

- Brief history

- CSW snapshot

- Preparations

- Official Documents

- Official Meetings

- Side Events

- Session Outcomes

- CSW65 (2021)

- CSW64 / Beijing+25 (2020)

- CSW63 (2019)

- CSW62 (2018)

- CSW61 (2017)

- Member States

- Eligibility

- Registration

- Opportunities for NGOs to address the Commission

- Communications procedure

- Grant making

- Accompaniment and growth

- Results and impact

- Knowledge and learning

- Social innovation

- UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women

- About Generation Equality

- Generation Equality Forum

- Action packs

- Open access

- Published: 03 May 2023

Gender differences in peer reviewed grant applications, awards, and amounts: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Karen B. Schmaling 1 &

- Stephen A. Gallo 2

Research Integrity and Peer Review volume 8 , Article number: 2 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

4145 Accesses

5 Citations

174 Altmetric

Metrics details

Differential participation and success in grant applications may contribute to women’s lesser representation in the sciences. This study’s objective was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to address the question of gender differences in grant award acceptance rates and reapplication award acceptance rates (potential bias in peer review outcomes) and other grant outcomes.

The review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021232153) and conducted in accordance with PRISMA 2020 standards. We searched Academic Search Complete, PubMed, and Web of Science for the timeframe 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2020, and forward and backward citations. Studies were included that reported data, by gender, on any of the following: grant applications or reapplications, awards, award amounts, award acceptance rates, or reapplication award acceptance rates. Studies that duplicated data reported in another study were excluded. Gender differences were investigated by meta-analyses and generalized linear mixed models. Doi plots and LFK indices were used to assess reporting bias.

The searches identified 199 records, of which 13 were eligible. An additional 42 sources from forward and backward searches were eligible, for a total of 55 sources with data on one or more outcomes. The data from these studies ranged from 1975 to 2020: 49 sources were published papers and six were funders’ reports (the latter were identified by forwards and backwards searches). Twenty-nine studies reported person-level data, 25 reported application-level data, and one study reported both: person-level data were used in analyses. Award acceptance rates were 1% higher for men, which was not significantly different from women (95% CI 3% more for men to 1% more for women, k = 36, n = 303,795 awards and 1,277,442 applications, I 2 = 84%). Reapplication award acceptance rates were significantly higher for men (9%, 95% CI 18% to 1%, k = 7, n = 7319 applications and 3324 awards, I 2 = 63%). Women received smaller award amounts ( g = -2.28, 95% CI -4.92 to 0.36, k = 13, n = 212,935, I 2 = 100%).

Conclusions

The proportions of women that applied for grants, re-applied, accepted awards, and accepted awards after reapplication were less than the proportion of eligible women. However, the award acceptance rate was similar for women and men, implying no gender bias in this peer reviewed grant outcome. Women received smaller awards and fewer awards after re-applying, which may negatively affect continued scientific productivity. Greater transparency is needed to monitor and verify these data globally.

Peer Review reports

Funding is needed to conduct most research and is key to scientists’ success. For example, extramural funding was among the criteria for tenure and promotion in the majority of a random sample of 92 biomedical sciences faculties, selected from among the top 852 universities in the world based on publication productivity [ 1 ]. Funded applications reflect positive evaluations of the significance and proposed methods of the research, and of the expertise of the investigator.

Around the world, women comprise an estimated 29.3% of researchers, which varies by country [ 2 ]. Women are underrepresented among researchers: in the United States (US), for example, women comprised 35.2% of doctorates in science, engineering, and health, but only 29.8% – a gap of 5.5% –was substantially engaged in research in 2017 [ 3 ]. Concerns about women’s underrepresentation in the sciences have focused on the leaky pipeline, unsupportive environments, and lack of mentoring, among other factors [ 4 ]. Biased evaluations, including peer reviewed grant applications, have been posited as another potential cause for differential success in the sciences [ 4 ]. Biases may be explicit or implicit, as reflected in overt discrimination or in automatic preferences, respectively. Men are more strongly associated with science than are women; this robust implicit bias effect has been replicated in 60 countries [ 5 ] and among STEM faculty at highly ranked universities in the US [ 6 ]. It seems plausible that biases and preferences may affect grant application and review processes, resulting in gender differences.

Evidence of gender bias in peer review has been inconsistent. Some narrative reviews have concluded that there is no evidence for gender bias in grant peer review [ 7 , 8 ]. Other narrative reviews provide a mixed picture. For example, men have been observed to apply for grants more than women, but the proportions of successful applicants are similar [ 9 ]. Another review cited studies that showed both gender differences and lack of differences in grant applications outcomes [ 10 ], which are sensitive to context [ 11 ].

Quantitative reviews have been rare. Two studies used different analytic methods to examine a dataset comprised of 66 gender comparisons from 21 studies that spanned the years 1987–2005 [ 12 , 13 ]. The earlier study compared odds ratios of applications and awards among women to those among men. They found that men were 7% more likely to receive an award than women, which was statistically significant, albeit associated with a small effect size [ 12 ]. The later study used more complex multilevel analyses that controlled for discipline, country, and year, and did not find significant gender differences [ 13 ].

Moderating variables, such as the nations studied, have contributed to an inconsistent literature on the association between gender and grant outcomes [ 11 , 13 ]. Recent gender equity efforts in the EU include a mandate that “gender… (is) a ranking criterion for proposals with the same score” [ 14 ], which may result in better gender parity than in nations without such laws, including the United States (US).

The purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature since 2005 regarding gender differences in grant outcomes by conducting meta-analyses and mixed models of each outcome. This study addressed the question of gender differences in grant applications, awards, award acceptance rates, award amounts, and reapplication award acceptance rates. We also examined nation (US vs. non-US) as a potential moderator of gender differences [ 11 , 13 ].

The review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA 2020 standards [ 15 ].

Protocol registration

The study protocol was submitted to PROSPERO on 19 January 2021 and was registered on 19 February 2021 (#CRD42021232153). This paper differs from the registered protocol as follows: the protocol did not list all of the measures of effect for each outcome measure; two of the proposed subgroup analyses (the type/level of grant mechanism and the gender of the study authors) could not be addressed in the scope of this paper.

Search strategy and study identification

Three search engines were chosen to provide comprehensive coverage of the literature after consultation with an academic librarian: Academic Search Complete, PubMed, and Web of Science. The keywords used were “peer review” AND grant AND gender; the range of publication dates was 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2020; languages were English or French. The searches were last performed on 2 February 2021. The beginning date was chosen based on the most recent year in the previous quantitative reviews [ 12 , 13 ].

Three people independently searched each database in January 2021 and compared the number of results. There was perfect agreement on the number of results from each search on each database. Next, two people independently screened the abstracts identified by each search and judged if each abstract clearly met or did not meet inclusion criteria.

The full text article of each possibly relevant manuscript was obtained and independently reviewed by two people to determine if it met inclusion criteria. The results of the three searches and the decision to include or exclude each study were combined and duplicate studies were eliminated. Relevant data (see below) were extracted by one person; all extracted data were checked by a second person. For articles in which incomplete data were reported, up to three emails were sent to corresponding authors to request additional data.

Additional relevant articles were found based on forward and backward searches of the articles identified through the systematic review. The reference lists of articles that met inclusion criteria were reviewed for earlier possibly relevant articles. Each search engine was used to identify later possibly relevant publications that had cited articles that met inclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included, the study needed to report data on numbers of peer reviewed grant applications, awards, or reapplications, or amounts of funding (mean or median and standard deviation or interquartile range) separately by gender. Studies were excluded that reported none of these variables, if the data had been reported in the previous review [ 12 , 13 ], or if the data in the study were superseded by a more comprehensive report. The last inclusion criterion was intended to identify independent, nonduplicated data sources: for example, a report of R-type applications by men and women otolaryngologists to the NIH in 2015 would be superseded by data from all NIH institutes regarding R-type applications from 2005–2020. If a report contained both unique data not included in another report and data superseded by another report, only the unique data were retained.

Extracted variables

Characteristics of the included studies were extracted including the country, type or name of the granting agencies, years studied, data source (data extracted from archives or obtained through survey), characteristics of the participants, if participants were referred to by sex (female, male) or gender (women, men) based on biological or socially-defined characteristics, respectively, grant type or mechanism, data on eligible populations (as included in the study or obtained through searching for data that reflected study characteristics including country, year, disciplines, and sector, e.g., higher education), and presence or absence of each outcome variable and the level of data reporting (person-level, application-level, or both). Finally, each study’s assessment of gender bias was extracted, noting if there was a conclusion that there was bias (or similar phrases including difference, gap, disparity, discrepancy, was inequitable, etc.), was no bias, the results were mixed or equivocal, or did not make this determination (i.e., only reported data), accompanied by a quotation from the article supporting the assessment.

Extracted outcome variables, by gender, were the number of grant applications, number of awards, award acceptance rate (awards divided by applications), amounts of awards, number of reapplications, number of awards after reapplication, and reapplication award acceptance rate. Proportions of applications, awards, reapplications, and awards after reapplications were calculated by the number for women divided by the total for men and women. For studies that reported more than one data source, data from each was extracted and preserved on a separate row. Reapplications and resubmissions were of two types: competitive renewals (e.g., a competitive renewal application following an R01 award) or resubmissions following unfunded applications. Award amounts were standardized by first converting the original currency to 2021 values using on-line calculators (see the Supplementary file eMethods ) and then converting to US$ using Google’s on-line currency converter. For studies that reported award amounts’ medians and interquartile ranges, a macro estimated means and standard deviations (see the Supplementary file eMethods ). Pre-specified moderator variables were extracted: the country in which the study was conducted (US or non-US).

The authors extracted and checked all data; disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data analysis

Datasets and analysis syntax are available on the project website. Descriptive statistics were calculated for each outcome variable, by gender. MetaXL version 5.3 [ 16 ] was used for the meta-analyses of gender differences using the raw (unweighted) data and compared subgroups of US versus non-US studies when 10 or more studies were available. Inverse variance heterogeneity models were used because of methodological diversity [ 17 ]. Forest plots were used to depict the effect size and 95% confidence interval (CI) of each study, grouped by US and non-US studies. Separate meta-analyses of gender differences were calculated for each outcome variable using the following effect sizes: award acceptance rates and reapplication award acceptance rates used rate differences; award amounts used Hedges’ g ; and analyses of proportions (applications, awards, reapplications) used double arcsine transformed prevalence [ 18 ]. Sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding each study in turn [ 19 ] (see the Supplementary file eResults ).

The dispersion of effect sizes was quantified with Q and I 2 statistics. Doi plots and the LFK index were used to assess reporting bias [ 20 ]. Doi plots graph the effect on the x axis and the Z -score of the quantile on the y axis; a vertical line appears at the Z -score closest to zero. Heterogeneity was evident when the two limbs of studies’ effects on either side of the vertical line formed a non-symmetrical inverted V shape. The LFK index was the difference in the area under each limb of the plot on either side of the vertical line. Values of the LKF index less than -1.0 and greater than 1.0 reflected asymmetry in the distribution of the studies’ Z -scores compared to the effect (proportion, rate difference, or g ).

In meta-analyses of proportions, forest plots and visual representations of effect size dispersion have been recommended to see the effects in individual studies but generalized linear mixed models with logit link function are recommended to estimate overall effects [ 21 ]. Thus, generalized linear mixed models (GLMM: IBM SPSS v28, Chicago IL) were used to estimate overall effects of gender and nation (US versus non-US) for the proportions of grant applications and awards, with the following assumptions: binomial probability distribution, logit link function, random effects for studies and intercepts; fixed effects for gender and nation (coded as US or non-US); repeated measure for gender. There were insufficient data to compare nations for the GLMMs of the proportions of application resubmissions or awards after resubmissions.

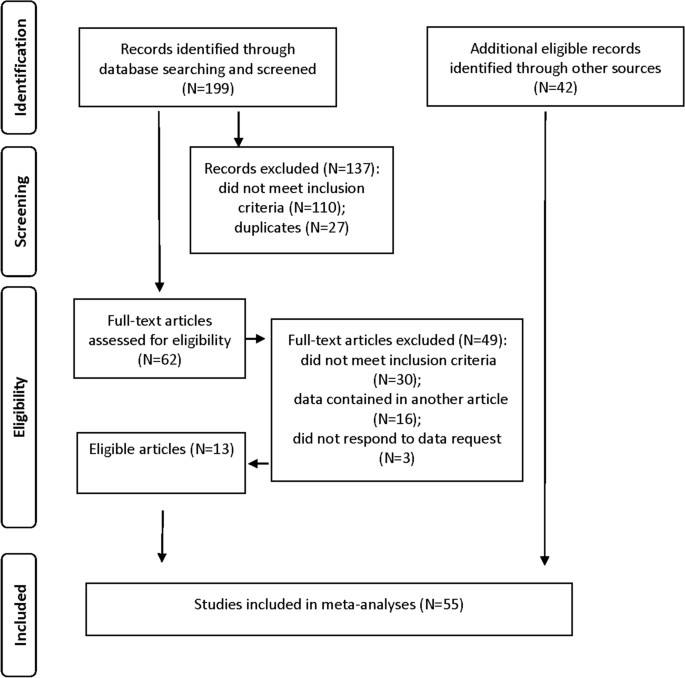

Included studies

A flow diagram [ 22 ] is shown in Fig. 1 . In summary, 241 studies were identified by the searches and other sources. After excluding studies that did not meet inclusion criteria, were duplicates, or contained data superseded by other studies, 55 studies provided data on one or more of the outcome variables [ 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 ].

Flow Diagram

These 55 studies provided data from 14 nations and the EU, reported data from 1975 to 2020 (see the Supplementary file eResults ) from diverse funding sources: 45 funding sources were named in the studies; additionally, five studies examined multiple funding sources (e.g., government, industry, foundation, intramural) but did not list the specific funders [ 34 , 40 , 42 , 72 , 73 ]. Most studies reported complete archival data on their population except for four studies that surveyed samples of participants [ 23 , 40 , 58 , 72 ]. Fourteen studies only referred to investigators by gender (25%), one study only referred to investigators by sex (2%, “male”, “female”), and 40 studies (73%) used both sex- and gender-linked terms regarding investigators.

Award acceptance rate

There were 29 sources comprising 36 samples that provided data for this meta-analysis ( n = 303,795 awards and 1,277,442 applications). (See Table 1 for meta-analysis results; see the Supplementary file eResults for forest plots, Doi plots and sensitivity analyses.) Unweighted average award acceptance rates were 22.7% for women and 24.3% for men. The pooled effect revealed a 1% lower award acceptance rate for women than men (95% CI 3% more for men to 1% more for women), which was not significantly different. Individual studies ranged from a 17% greater award acceptance rate for men in an intramural program [ 41 ] to a 5% greater award acceptance rate for women in a grant-writing program [ 74 ]. There was significant heterogeneity ( Q = 212.96, p < 0.001, I 2 = 84%) with evidence of reporting bias (LFK = -2.85). Among these 36 samples, the pooled award acceptance rate was 2% higher for men than women in non-US nations and 1% higher for men than women in the US, which was not significantly different.

Reapplication award acceptance rate

There were seven samples from six sources in this meta-analysis ( n = 3,324 awards and 7,318 applications). The pooled funding rate after reapplication was significantly (9%) lower for women than men ( k = 7; 95% CI 18% to 1%): unweighted data revealed a 38% funding rate for women versus 48% for men with moderate heterogeneity ( Q = 16.28, p = 0.01, I 2 = 63%) and no significant reporting bias (LFK = -0.44). Individual studies ranged from no gender difference among early career investigators in the Netherlands [ 71 ] to a 42% higher funding rate for men in otolaryngology who had previously received small grants [ 33 ]. There were five samples from the US and two from outside of the US, which were insufficient for nation comparisons.

Award amounts

There were 13 samples from nine sources that provided data for this meta-analysis ( n = 212,935 awards). The unweighted averages (and standard deviations) were $341,735.54 ($275,465.79) for women and $659,081.00 ($967,813.34) for men. Men received significantly larger award amounts than did women by a factor of 2.28 (95% CI 4.92 to 0.36). While all studies reported larger awards to men, the gender differential ranged from 0.11 for a Canadian program in the cognitive sciences [ 69 ] to a factor of 5.13 for NIH research project grants [ 52 ]. There was significant heterogeneity ( Q = 119,416.86, p < 0.001, I 2 = 100%), but no significant reporting bias (LFK = 0.67). In subgroup comparisons, the disparity between men’s and women’s award amounts was greater in the US than in non-US nations (factor of 5.11 compared to 0.24).

Proportions of applications

Thirty-two sources provided 39 independent samples of applications ( n = 1,311,5552, median per source = 3615, IQR = 15,464). Women accounted for 30% of applications (95% CI 22% to 38%). As shown in the forest plot, the proportion of women applicants ranged from 13% in the agricultural sciences [ 51 ] to 70% among a small cohort of biomedical researchers in a grant writing coaching program [ 74 ]. There was significant heterogeneity in effect sizes ( Q = 17,060, p < 0.001, I 2 = 100%) and in data sources with numbers of applications ranging from 64 to over 771,000. There was significant reporting bias (LFK = 2.87).

In subgroup comparisons of these 39 samples, there were similar pooled proportions of applications from women in US and non-US studies (30% and 31%, respectively). The results of the GLMM procedure showed a strong main effect for gender ( F (1,74) = 649.80, p < 0.001, but the main effect of nation and the gender by nation interaction were not significant ( F (1,74) = 0.00 and 1.08, p = 1.00 and 0.30, respectively).

Proportions of reapplications

Application resubmissions were reported by ten sources ( n = 44,138, median per source = 899, IQR = 3526) among previously successful (i.e., awardees) and unsuccessful applicants: women accounted for 31% of resubmissions (95% CI 24% to 37%). In individual studies the proportions of women reapplicants ranged from 23% in a study of Harvard Medical School faculty [ 73 ] to 62% among obstetrics-gynecology K awardees [ 54 ]. There was significant heterogeneity ( Q = 195.04, p < 0.001, I 2 = 95%) and evidence favoring reports of greater proportions of applications from women (LFK = 3.37). The results of the GLMM procedure revealed a strong main effect for gender ( F (1,18) = 534.54, p < 0.001). There were insufficient studies to conduct nation comparisons.

Proportions of awards

Forty-one sources provided 47 independent samples of the proportion of awards by gender ( n = 615,653 awards, median per source = 2377, IQR = 3785): women accounted for 24% of awards (95% CI 14% to 34%). The proportion of awards to women ranged from 17% in a Swiss program [ 37 ] to 72% among grant-writing program participants [ 72 ]. Reflecting the diversity in methodology, there was significant heterogeneity ( Q = 15,711.24, p < 0.001, I 2 = 100%) and evidence favoring reports of greater proportions of awards to women (LKF = 7.07).

Using these 47 samples, the proportion of awards to women was 6% higher in non-US nations than in the US (29% and 23%, respectively). The results of the GLMM procedure showed a strong main effect for gender ( F (1,88) = 437.08, p < 0.001, and a gender by nation interaction ( F (1,88) = 11.11, p = 0.001, but the main effect of nation was not significant ( F (1,88) = 0.00, p = 1.00). The proportion of awards to women in the US was smaller than to women elsewhere, and the proportion of awards to men in the US was larger than to men elsewhere.

Proportions of awards after reapplications

Based on ten sources, women received 30% of awards ( n = 156,574, median per source = 221, IQR = 854) after reapplication among previously funded scientists (95% CI 19% to 42%). The proportions of reapplying women awardees ranging from 8% among otolaryngologists who had previously received small grants [ 31 ], to 60% among previous obstetrics-gynecology K awardees [ 54 ] and among previous developmental psychopathology T recipients [ 60 ]. There was significant heterogeneity ( Q = 116.83, p < 0.001, I 2 = 92%) and evidence favoring reports of greater proportions of awards to women (LFK = 2.82). The results of the GLMM procedure showed a strong main effect for gender ( F (1,18) = 3487.11, p < 0.001). There were insufficient studies for nation comparisons.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses showed the extent to which excluding some of the large datasets would alter the outcomes, especially the NIH data [ 52 ]. Regarding the award acceptance rate and amount comparisons, when each study was excluded in turn, excluding the NIH data would have increased men’s greater award acceptance rate to 1.6% from a pooled rate of 1.0%, and men’s greater award amounts would have decreased to a factor of 0.24 more than women’s from a pooled factor of 2.28. For the proportion of applications, excluding the NIH data would decrease the proportion of applications from women to 28.5% from a pooled proportion of 30% with all studies included. For the proportion of awards, excluding the NIH data would have decreased the proportion of awards to women to 21.6%, compared to 24% with all studies included. Excluding the NIH data would have decreased the proportion of women receiving awards after resubmission to 27.3% from 30%. Finally, the sensitivity analyses of the proportions of application resubmissions and reapplication award acceptance rates showed small changes, less than 1%, when studies were excluded. None of the sensitivity analyses substantially changed heterogeneity such that statistically significant Q and large I 2 statistics were no longer so.

Representation of eligible researchers by gender

It is important to place these results in the context of the proportion of eligible researchers by gender. Supplementary file eResults (eTable2) summarizes the proportion outcomes for each study (from eFigures 10 , 13 , 16 , 19 ).

Proportions of eligible women researchers were estimated for each study ( n = 13,553,340, median per source = 17,585, IQR = 119,387). The pooled estimate of eligible women was 36% (95% CI 33% to 39%). As shown in the forest plot, the proportion of eligible women ranged from 13% in Italian agricultural sciences [ 51 ] to 67% among pediatric residents [ 41 ], developmental psychobiology postdoctoral trainees [ 60 ], and biomedical researchers in a grant writing coaching program [ 74 ]. There was significant heterogeneity in effect sizes ( Q = 130,375, p < 0.001, I 2 = 100%) and significant reporting bias (LFK = 2.07).

For each study, two columns in eTable 2 appraise the application/reapplication and award/award after reapplication proportions as less than, greater than, or equivalent to the eligible proportions (see Supplemental file eMethods ). Fewer women applied than were eligible in 54% of studies (25 of 46); more applied than were eligible in 22% of studies (10 of 46); and the proportions were equivalent in 24% of studies (11 of 46). Fewer women received awards in 65% of comparisons to eligible proportion estimates (33 of 51); more women in 20% (10 of 51); and equivalent proportions in 16% (8 of 51) (percentages are rounded). In the majority of papers, women were less likely to apply and to receive awards compared to those who were eligible.

A systematic review of the 2005–2020 literature yielded 55 sources of gender data on peer reviewed grants, predominantly from Europe and North America. The proportions of women that applied for grants (30%), re-applied (31%), accepted awards (24%), and accepted awards after reapplication (30%) were less than the proportion of eligible women (36%). However, the award acceptance rate was similar for women and men, implying no gender bias in this peer reviewed grant outcome. Additionally, women received smaller award amounts and fewer awards after re-applying, but these estimates were based on smaller numbers of studies.

This lack of gender difference in award acceptance rate is consistent with earlier observations [ 9 , 13 , 56 , 78 ]. A previous analysis of 1987–2005 grant award acceptance rates from Australia, western Europe and the United States found a 7% higher award acceptance rate for men albeit with a small effect size [ 12 ], but multilevel analyses of the same data that controlled for several factors found insignificant gender effects [ 13 ]. The 7% disparity was greater than the 1% higher award acceptance rate for men found in this study, which was not significant because the 95% confidence interval included zero. Thus, both current and past [ 13 ] reviews found nonsignificant gender differences for award acceptance rates. The previous review focused on one outcome – the gender difference in award acceptance rates – and all of the studies in their review provided data on this outcome. The present study examined other outcomes in addition to award acceptance rate and the outcomes reported by each source varied: not all sources provided data on all outcome variables. Ideally, all outcome variables would be available from each source to facilitate interpretation and comparison. The previous review performed a broader search (seven databases compared with three in the present study), but both studies used similar search terms (peer review; gender) and the sources were from similar geographic regions. The previous review used multilevel models; our study used traditional meta-analyses to examine gender albeit with a novel inverse variance heterogeneity model [ 17 ], augmented by multilevel models for outcomes expressed as proportions.

To further compare our data with the previous review [ 12 , 13 ], we input their data, aggregated all data for each source and conducted analyses of the proportions of applications and awards as we had done in the present study. The pooled prevalence of the proportions of women’s applications and awards were 21% and 19% based on the earlier data, as compared to 30% and 24% in the present study, suggesting that there have been significant gains in the representation of women among applicants and awardees since 2005 (see eDiscussion), consistent with a recent narrative review [ 11 ].

Persistence and securing continued funding are necessary for continued scientific productivity and advancement. Women submitted 31% of reapplications, however, their reapplication acceptance rate was significantly lower (9%) than men. The gap between the pooled gender disparities for the general award acceptance rate and the reapplication acceptance rate – 1% versus 9% – may result from underlying variability in the studies that contributed data to each statistic. Some of the reapplication studies examined reapplication of the same applications, and some examined continued funding or advancement in research, such as awards of research grants among previous career or small grant awardees.

Peer review of grant applications typically includes an evaluation of the investigator’s suitability to conduct the research, based on their past accomplishments, such as prior publications. Evaluations of women’s research accomplishments suffer when their research is devalued and their publications are less cited [ 79 ]. Increasingly, however, the use of metrics such as journal impact factor is discouraged, e.g., by projects DORA/TARA [ 80 ]. Women are less represented as academic rank increases, although the causes of women’s lesser representation are unclear [ 2 ]. Relatively few studies reported data on resubmissions after unsuccessful applications, competitive renewals, or maturation in funding mechanisms. In general, women resubmitted applications in similar proportions to overall applications: about 31%. Women comprised proportionally more of those with awards after resubmissions (30%) than women with general awards (24%).

Women’s 9% lower award acceptance rate after reapplication may reflect possible bias and the leaky pipeline [ 4 ] more than any other result in this study. This result was also consistent with the majority of studies’ conclusions that there was gender bias favoring men (see eResults). Male applicants have reported receiving more constructive feedback from peer reviewers than did female applicants [ 81 ], which may contribute to better outcomes after reapplication. Women were more likely to interpret peer reviewers’ feedback more negatively than did men, which in turn was related to less intention to reapply [ 28 ]. Women may be more discouraged by grant rejections than men, contributing to differential research productivity and longevity [ 82 ]. Women’s lesser success than men’s after reapplying for grants sheds no light on the potential processes contributing to this phenomenon, which are worthy of study. Furthermore, a focus on outcomes, as in the present study, does not address the complex interaction of individual, systemic, and social barriers that may produce and maintain such outcomes [ 11 , 79 ].

Women received significantly smaller award amounts than did men. This effect was especially pronounced for US-based studies: nation has been suggested as a potential moderator of gender differences in previous studies [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]. While the comparison of US and other nations’ amounts is novel, others have observed that women request and receive smaller award amounts than men. This effect could be because of different types and costs of research, lower salaries [ 83 ], or differential entitlement resulting from professional mentoring or other qualities [ 45 ]. Administrative budget reductions also could be a source of gender disparities. NIH awards are often less than requested: for example, the National Institute of Aging reduced continuing awards by an average of 20% in FY 2022 [ 84 ]. However, it would be unusual for other funders to award a lesser amount than requested, such as the Wellcome Trust [ 85 ]. In two papers in our review, women and men received similar proportions of their requested amounts in one [ 73 ], and in the other, men’s awarded amounts were significantly greater than women’s although their requested amounts did not differ [ 56 ], which the authors posit could be due to a bias against women engaging in risky research. Investigator requests, peer reviewer recommendations, and administrative decisions are all potential sources of gender differences in grant award amounts.

In comparisons of the US to non-US studies, there was a small difference in the proportion of applications submitted by women (1% more in non-US studies) and a 6% higher proportion of awards to women in non-US studies. These findings are potentially consistent with a 2020 report from the World Economic Forum in which the US ranked 53 rd in gender equality among 153 countries [ 86 ]. In contrast to the US, gender equity laws and policies exist in many EU countries [ 14 ].

It is important to place these results in the context of the representation of researchers by gender but challenging to do so. In the majority of studies, women were less likely to apply and to receive awards compared to estimates of eligible populations. However, these comparisons should be interpreted cautiously. Some estimates of the eligible population were precise (e.g., [ 63 ]), but other estimates were less specific to the sample. For example, some studies’ eligible proportions were based on all researchers whereas the grant applications were for early career researchers (e.g., [ 48 ]) and unsurprisingly, women’s share of applications was greater than the eligible proportion because women are better represented in the earlier academic ranks.

This study contributes to the reviews of gender participation in peer reviewed grants and is the only review of which we are aware to use systematic review and meta-analytic techniques since the 2007 and 2009 papers [ 12 , 13 ]. It is also unique in its consideration of several variables reflecting different aspects of participation and review. It also had several limitations. First, the data used in the study did not include all nations, mechanisms, and the entire 2005–2020 period. The sources were limited to those identified by searching the published literature and those cited by or citing the published literature, which included some reports from nations’ funders. It would be valuable to conduct a systematic review based on funders’ reports. Population data from funding sources would likely provide more stable estimates of outcomes. A search of the Pivot-RP database of funders (ProQuest, Inc) identified 8,857 government (national, state, local), industry, foundation, institutional, private, and other funders in the geographic regions of the studies in our review. Thus, our report stemming from the published literature represents data from a minority of possible funders. As shown in Fig. 1 , records in the meta-analysis found by the database searches were fewer than the additional sources identified by reviewing citated or citing articles of the records found through database searches. Some of the articles found through database searching were superseded by other sources or were included in the previous review (see Fig. 1 ). The additional sources were not identified by the database searches for several reasons. Of the 42 additional sources, 30 were indexed in PubMed; of those, 1 was not indexed, 7 (23%) were not indexed as gender; 10 (33%) were not indexed as grants or research support; and 15 (50%) were not indexed as peer review. The diversity of the additional sources suggests that the original search strategy was appropriate, but this literature had inconsistent index terms.

Some authors and funding agencies were responsive to our requests for additional data, but some did not respond or indicated they would not or could not provide data. For example, one national funding agency compiled data in response to our request, but its release to us was embargoed by its authorities. Such missing data could have contributed to the evidence of reporting bias found for most of the variables we examined.

Second, our goal was to use non-overlapping datasets. Most of the otherwise eligible studies identified by our searches were excluded because their data were superseded by another source. However, some overlap was still possible. For example, applications by Harvard school of medicine faculty to diverse funders probably included the NIH [ 73 ], but we were unable to examine applications separately by funding entity.

Third, we combined years of data because some sources could not be disaggregated by year or funding mechanism. The inability to disaggregate data by year and add a time variable to the analyses was a limitation of the study. The prior meta-analysis found no effect for the year that the study was published but noted that the year of the data collection may be a more appropriate comparator [ 12 ]. In future studies it would be valuable to examine the trajectories of change in award acceptance rates and other outcomes over time, particularly given the increased emphasis on gender equity initiatives and policies in recent years, some appear to result in a narrowing gender gap [ 2 ].

Sources varied in reporting data aggregated across funding mechanisms, or separately for different mechanisms. Although formal comparisons of outcomes for different mechanisms were beyond the scope of this paper, for example, women appeared to be more successful with personnel mechanisms (e.g., NWO “talent”, Swiss NSF career, NIH K) than research mechanisms (e.g., NWO “free competition”, Swiss NSF project, NIH research project grants). There would be value in examining data disaggregated by funding mechanism in addition to year.

Fourth, for some studies’ award amounts, we estimated the mean and standard deviation from median and IQR. Those studies’ data may not have been normally distributed, so the estimation of the mean and standard deviation may not be valid. Fifth, as most studies reported data on their population of interest, we did not conduct quality assessments on the small numbers of studies that surveyed samples. Sixth, studies were heterogeneous in size and focus, which may have contributed to the variability in effect sizes observed in most of the analyses.

Narrative reviews have stated that “grant peer review is a gender fair process” ([ 7 ], p. 3160] based on grant award acceptance rates. But conclusions about processes should not be inferred from outcomes [ 11 ]. Inferences about peer review processes should be based on process studies – for example, entailing blind reviews or experimental manipulation of gender pronouns – rather than on outcomes. While outcomes are suggestive, they are an insufficient basis for conclusions about processes. Also, a focus on variables beyond award acceptance rates is important to provide a more complete picture of gender similarities and differences. Differences in the submission of grant applications or the receipt of grant awards reflect different processes and involve different individuals, including investigators, mentors, peer reviewers, and scientific review officers. Additionally, the extant literature may include incorrect or misinterpreted information. For example, a widely cited study [ 45 ] reported that same number of applications by men to both NSF and NIH, and one of its authors affirmed that the number of applications to NSF was an error. This error raises concerns about others’ conclusions based on the data therein.

Future research on this topic would address the limitations in this study. Ideally, data would be disaggregated by year to inspect trends over time, and by gender or sex, with the latter concepts clearly identified and defined. Every source should provide person-level data on all outcome variables to facilitate the following comparisons: applicants to eligible applicants; rates of accepted awards to applications; reapplicants to eligible reapplicants; rates of accepted awards after reapplication to reapplications; awarded amounts to requested amounts. Moderator variables should include investigator variables of discipline, age, career level, institution type, percent of effort dedicated to research, previous productivity (papers, grants); funder variables of type (public, private), funding mechanism, and if the funder is subject to gender equity laws or policies; and contextual variables of author gender (e.g., proportion of women authors of the report) and proportion of eligible women or women in the discipline. The foundation of this study was a systematic review of the published literature, followed by forwards and backwards searches, which yielded heterogenous sources from small intramural grant programs to large, national funders. Analyses of more homogeneous sources would be valuable, such as data from national funders separately from private foundations, and from intramural mechanisms.

Evidence of differential gender participation in peer reviewed grant applications and awards has led to recommended [ 4 ] and implemented policies, such as “structural priority funding” to women ( [ 25 ], p. 3). Increasing the proportions of women grant peer reviewers is also recommended. A recent study of NIH study sections found women comprised about one-third of reviewers [ 87 ]. They recommended increasing women’s involvement in the review process for “opportunities to impact the nation’s research agenda” ([ 87 ], p. 3). More fundamentally, participation in peer review provides invaluable insight into the peer review process, to cutting edge ideas, and to new colleagues for collaboration, mentoring, and sources of external review letters. Europe has been a leader in policies to promote gender equality in research funding, such as Horizon Europe [ 14 ], gender quotas on review panels [ 88 ], and the Marie Sklodowska-Curie actions: the latter reported that from 2014 to 2018, women received 53.2% of the projects for experienced researchers [ 89 ]. Other countries’ gender equity policies and initiatives have not yet met with this level of success. In the UK, the representation of women professors in UK institutions of higher education grew from 24.2% in 2012/2013 to 26.8% in 2016/2017, but the growth was not clearly linked to institutions’ level of engagement with the Athena Scientific Women’s Academic Network (SWAN) initiative [ 90 ]. In the US, women faculty in STEM among awardees of NSF Institutional Transformation grants grew 8% to 24% and comparator institutions grew relatively less (5%) but had better overall representation (27%) [ 91 ]. Individuals’ outcomes – the focus of this review – cannot reflect cumulative systemic and social inequalities and disadvantages [ 11 , 79 ] that are contextually important to and drivers of such outcomes. Equity initiatives hold promise to compensate for some sources of gender disparities.

Women submitted only 30% of grant applications – less than those eligible to do so – but their award acceptance rate was similar to men. However, women received smaller award amounts and fewer awards after reapplying, which may negatively affect continued scientific productivity. These estimates were based on smaller numbers of data points than for award acceptance rates. Greater transparency in grant funding is needed to monitor and verify these data globally, and to allow for analysis of changes over time.

Availability of data and materials

The analysis syntax and datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available at the Open Science repository, https://osf.io/e5t4v/ .

Rice DB, Raffoul H, Ioannidis JP, Moher D. Academic criteria for promotion and tenure in biomedical sciences faculties: cross sectional analysis of international sample of universities. BMJ. 2020;m2081. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2081 .

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Women in Science. Fact Sheet 55, June 2019. http://uis.unesco.org/en/topic/women-science# . Accessed 5 June 2022.

Foley DJ, Selfa LA, Grigorian KH. Number of women with US doctorates in science, engineering, or health employed in the United States more than doubles since 1997. National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, February 2019, NSF 19–307. https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2019/nsf19307/nsf19307.pdf . Accessed 5 June 2022.

Committee on Maximizing the Potential of Women in Academic Science and Engineering (US). Beyond bias and barriers: Fulfilling the potential of women in academic science and engineering. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007.

Google Scholar

Miller DI, Eagly AH, Linn MC. Women’s representation in science predicts national gender-science stereotypes: evidence from 66 nations. J Educ Psychol. 2015;107(3):631–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000005 .

Article Google Scholar

Marini M, Banaji MR. An implicit gender sex-science association in the general population and STEM faculty. J Gen Psychol, 2020;1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.2020.1853502

Ceci SJ, Williams WM. Understanding current causes of women’s underrepresentation in science. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(8):3157–62. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1014871108 .

Ceci SJ, Ginther DK, Kahn S, Williams WM. Women in academic science: a changing landscape. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2014;15(3):75–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100614541236 .

Marsh HW, Jayasinghe UW, Bond NW. Improving the peer-review process for grant applications: reliability, validity, bias, and generalizability. Am Psychol. 2008;63(3):160–8. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.63.3.160 .

Lee CJ, Sugimoto CR, Zhang G, Cronin B. Bias in peer review. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2013;64(1):2–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22784 .

Cruz-Castro L, Ginther DK, Sanz-Menendez L. Gender and underrepresented minority differences in research funding. Working paper 30107, National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2022. https://doi.org/10.3386/w30107 . Accessed 14 Jan 2023.

Bornmann L, Mutz R, Daniel H. Gender differences in grant peer review: A meta-analysis. J Informetr. 2007;1(3):226–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2007.03.001 .

Marsh HW, Bornmann L, Mutz R, Daniel H-D, O’Mara A. Gender effects in the peer reviews of grant proposals: a comprehensive meta-analysis comparing traditional and multilevel approaches. Rev Educational Res. 2009;79(3):1290–326. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654309334143 .

European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. Horizon Europe, gender equality: a strengthened commitment in Horizon Europe. Publications Office, 2021, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/97891 https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/97891

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PMPRISMA, et al. explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2020;2021(372):n160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160 .

Barendregt J. MetaXL User Guide version 5.3. EpiGear International. [cited 2021 Feb 2]. Available from: https://www.epigear.com/ .

Doi SAR, Barendregt JJ, Khan S, Thalib L, Williams GM. Advances in the meta-analysis of heterogeneous clinical trials I: the inverse variance heterogeneity model. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45:130–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2015.05.009 .

Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(11):974–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2013-203104 .

Viechtbauer W, Cheung MW-L. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):112–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.11 .

Furuya-Kanamori L, Barendregt JJ, Doi SAR. A new improved graphical and quantitative method for detecting bias in meta-analysis. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2018;16(4):195–203. https://doi.org/10.1097/xeb.0000000000000141 .

Lin L, Xu C. Arcsine-based transformations for meta-analysis of proportions: pros, cons, and alternatives. Health Sci Rep. 2020;3(3):e178. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.178 .

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 .

Akabas MH, Brass LF. The national MD-PhD program outcomes study: Outcomes variation by sex, race, and ethnicity. JCI Insight. 2019;4(19). https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.133010 .

Andersson ER, Hagberg CE, Hägg S. Gender bias impacts top-merited candidates. Front Res Metr Anal. 2021;6(594424). https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2021.594424 .

Australian Government, National Health and Medical Research Council. Investigator Grants 2019/2020 Outcomes Factsheet. 2020. [cited 2021 March 14]. Available from: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/funding/data-research/outcomes#download .

Bautista-Puig N, García-Zorita C, Mauleón E. European Research Council: excellence and leadership over time from a gender perspective. Res Eval. 2019;28(4):370–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvz023 .

Beck R, Halloin V. Gender and research funding success: case of the Belgian F.R.S.-FNRS. Res Eval. 2017;26(2):115–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvx008 .

Biernat M, Carnes M, Filut A, Kaatz A. Gender, race, and grant reviews: Translating and responding to research feedback. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2019;46(1):140–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219845921 .

Boyington JEA, Antman MD, Patel KC, Lauer MS. Toward independence: resubmission rate of unfunded National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute R01 research grant applications among early stage investigators. Acad Med. 2016;91(4):556–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001025 .

Boyle PJ, Smith LK, Cooper NJ, Williams KS, O’Connor H. Gender balance: women are funded more fairly in social science. Nature. 2015;525(7568):181–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/525181a .

Burns KE, Straus SE, Liu K, Rizvi L, Guyatt G. Gender differences in grant and personnel award funding rates at the Canadian Institutes of Health Research based on research content area: a retrospective analysis. PLoS Med. 2019;16(e1002935). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002935 .

Danish Independent Research Foundation. Annual Report 2020. [Cited 29 April 2021.] https://dff.dk/aktuelt/publikationer/annual-report-2020 .

Dorismond C, Prince AC, Farzal Z, Zanation AM. Long-term academic outcomes of triological society research career development award recipients. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(2):288–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.28714 .

Dubosh NM, Boyle KL, Carreiro S, Yankama T, Landry AM. Gender differences in funding among grant recipients in emergency medicine: a multicenter analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(7):1357–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.11.006 .

Eloy JA, Svider PF, Folbe AJ, Setzen M, Baredes S. AAO-HNSF CORE grant acquisition is associated with greater scholarly impact. Otolaryngology Head Neck Surg. 2013;150(1):53–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599813510258 .

Escobar-Alvarez SN, Myers ER. The Doris Duke clinical scientist development award. Acad Med. 2013;88(11):1740–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e3182a7a38e .

Escobar-Alvarez SN, Jagsi R, Abbuhl SB, Lee CJ, Myers ER. Promoting gender equity in grant making: what can a funder do? Lancet. 2019;393(10171). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30211-9 .

Fabila-Castillo LH. Funding of basic science in Mexico: The role of gender and research experience on success. Tapuya: Latin Am Sci Technol Soc. 2019;2(1):340–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/25729861.2019.1667157 .

Fischer C, Reckling F. Factors influencing approval probability in FWF decision-making procedures. Vienna, Austria: Fonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung (FWF) 2010 [Cited 16 March 2021]. https://m.fwf.ac.at/fileadmin/files/Dokumente/Ueber_den_FWF/Publikationen/FWF-Selbstevaluation/FWF-ApprovalProbability_P-99-08_15-12-2010.pdf

Gallo S, Thompson L, Schmaling K, Glisson S. Risk evaluation in peer review of grant applications. Environ Syst Decis. 2018;38(2):216–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-018-9677-6 .

Gordon MB, Osganian SK, Emans SJ, Lovejoy FH. Gender differences in research grant applications for pediatric residents. Pediatrics. 2009124(2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-3626 .

Head MG, Fitchett JR, Cooke MK, Wurie FB, Atun R. Differences in research funding for women scientists: a systematic comparison of UK investments in global infectious disease research during 1997–2010. BMJ Open. 2013;3(12). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003362 .

Hechtman LA, Moore NP, Schulkey CE, Miklos AC, Calcagno AM, Aragon R, et al. NIH funding longevity by gender. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(31):7943–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1800615115 .

Heggeness ML, Evans L, Pohlhaus JR, Mills SL. Measuring diversity of the National Institutes of Health–funded workforce. Acad Med. 2016;91(8):1164–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001209 .

Hosek SD, Cox AG, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Kofner A, Ramphal NR, Scott J, et al. Gender differences in major federal external grant programs. RAND Corporation. 2005 [cited 2021 May 19]. Available from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR307.html

Johnson S, Kirk J. Dual-anonymization yields promising results for reducing gender bias: a naturalistic field experiment of applications for Hubble Space Telescope Time. Publ Astron Soc Pac. 2020;132(1009):034503. https://doi.org/10.1088/1538-3873/ab6ce0 .

Kalyani RR, Yeh H-C, Clark JM, Weisfeldt ML, Choi T, MacDonald SM. Sex differences among career development awardees in the attainment of independent research funding in a Department of Medicine. J Womens Health. 2015;24(11):933–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2015.5331 .

Ledin A, Bornmann L, Gannon F, Wallon G. A persistent problem. EMBO Rep. 2007;8(11):982–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7401109 .