National Historical Publications & Records Commission

The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Stanford University

Additional information: https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/publications/king-papers

A comprehensive edition of the papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929 –1968) clergyman, activist, and leader in the African-American Civil Rights Movement. He is best known for his role in the advancement of civil rights using nonviolent civil disobedience. King has become a national icon in the history of American progressivism. A Baptist minister, King became a civil rights activist early in his career. He led the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott and helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957, serving as its first president. With the SCLC, King led an unsuccessful struggle against segregation in Albany, Georgia, in 1962, and organized nonviolent protests in Birmingham, Alabama, that attracted national attention following television news coverage of the brutal police response. King also helped to organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech. This edition of speeches, sermons, correspondence, and other papers of America’s foremost leader of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The project was initiated by the King Center in Atlanta before moving to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford.

Seven completed volumes of a planned 14-volume edition

Martin Luther King, Jr. addresses the crowd at the Civil Rights March, August 28, 1963. National Archives.

Previous Record | Next Record | Return to Index

- Martin Luther King, Jr.

- King's Writings

- Research Databases

Primary Sources

- Civil Rights Movement Guide This link opens in a new window

- African American Studies Guide This link opens in a new window

- Online King Records Access (Stanford)

- Smithsonian - Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

- FBI Records: The Vault - Martin Luther King, Jr.

- JFK Presidential Library - Martin Luther King, Jr.

- Letter From a Birmingham Jail, April 16, 1963

- "I Have a Dream," August 28, 1963

- Official Program for the March on Washington, August 28, 1963

- "Who Speaks for the Negro?," March 18, 1964

- "Beyond Vietnam," April 4, 1967

- “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” April 3, 1968

- Black Freedom Struggle Primary Source Collection (ProQuest) This link opens in a new window In this website, the editors present primary source documents from several of the time periods in American History when the river of the Black Freedom Struggle ran more powerfully, while not losing sight of the fierce, often violent opposition that Black people have faced on the road to freedom.

- African American Newspapers (NewsBank) This link opens in a new window Over 270 African American newspapers published between 1827 and 1998.

- New York Times Historical, 1851-2019 (ProQuest) This link opens in a new window This historical newspaper provides genealogists, researchers and scholars with online, easily-searchable first-hand accounts and unparalleled coverage of the politics, society and events of the time.

- << Previous: Research Databases

- Next: Multimedia >>

- Last Updated: May 10, 2024 3:35 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uwf.edu/mlk

Black Power

Although African American writers and politicians used the term “Black Power” for years, the expression first entered the lexicon of the civil rights movement during the Meredith March Against Fear in the summer of 1966. Martin Luther King, Jr., believed that Black Power was “essentially an emotional concept” that meant “different things to different people,” but he worried that the slogan carried “connotations of violence and separatism” and opposed its use (King, 32; King, 14 October 1966). The controversy over Black Power reflected and perpetuated a split in the civil rights movement between organizations that maintained that nonviolent methods were the only way to achieve civil rights goals and those organizations that had become frustrated and were ready to adopt violence and black separatism.

On 16 June 1966, while completing the march begun by James Meredith , Stokely Carmichael of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) rallied a crowd in Greenwood, Mississippi, with the cry, “We want Black Power!” Although SNCC members had used the term during informal conversations, this was the first time Black Power was used as a public slogan. Asked later what he meant by the term, Carmichael said, “When you talk about black power you talk about bringing this country to its knees any time it messes with the black man … any white man in this country knows about power. He knows what white power is and he ought to know what black power is” (“Negro Leaders on ‘Meet the Press’”). In the ensuing weeks, both SNCC and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) repudiated nonviolence and embraced militant separatism with Black Power as their objective.

Although King believed that “the slogan was an unwise choice,” he attempted to transform its meaning, writing that although “the Negro is powerless,” he should seek “to amass political and economic power to reach his legitimate goals” (King, October 1966; King, 14 October 1966). King believed that “America must be made a nation in which its multi-racial people are partners in power” (King, 14 October 1966). Carmichael, on the other hand, believed that black people had to first “close ranks” in solidarity with each other before they could join a multiracial society (Carmichael, 44).

Although King was hesitant to criticize Black Power openly, he told his staff on 14 November 1966 that Black Power “was born from the wombs of despair and disappointment. Black Power is a cry of pain. It is in fact a reaction to the failure of White Power to deliver the promises and to do it in a hurry … The cry of Black Power is really a cry of hurt” (King, 14 November 1966).

As the Southern Christian Leadership Conference , the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People , and other civil rights organizations rejected SNCC and CORE’s adoption of Black Power, the movement became fractured. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Black Power became the rallying call of black nationalists and revolutionary armed movements like the Black Panther Party, and King’s interpretation of the slogan faded into obscurity.

“Black Power for Whom?” Christian Century (20 July 1966): 903–904.

Branch, At Canaan’s Edge , 2006.

Carmichael and Hamilton, Black Power , 1967.

Carson, In Struggle , 1981.

King, Address at SCLC staff retreat, 14 November 1966, MLKJP-GAMK .

King, “It Is Not Enough to Condemn Black Power,” October 1966, MLKJP-GAMK .

King, Statement on Black Power, 14 October 1966, TMAC-GA .

King, Where Do We Go from Here , 1967.

“Negro Leaders on ‘Meet the Press,’” 89th Cong., 2d sess., Congressional Record 112 (29 August 1966): S 21095–21102.

- Divisions and Offices

- Grants Search

- Manage Your Award

- NEH's Application Review Process

- Professional Development

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- NEH Virtual Grant Workshops

- Awards & Honors

- American Tapestry

- Humanities Magazine

- NEH Resources for Native Communities

- Search Our Work

- Office of Communications

- Office of Congressional Affairs

- Office of Data and Evaluation

- Budget / Performance

- Contact NEH

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Human Resources

- Information Quality

- National Council on the Humanities

- Office of the Inspector General

- Privacy Program

- State and Jurisdictional Humanities Councils

- Office of the Chair

- NEH-DOI Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Partnership

- NEH Equity Action Plan

- GovDelivery

The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Division of research programs.

Martin Luther King Jr, 1964.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

This definitive edition of Dr. King’s most significant speeches, sermons, correspondence, public statements, published writings and unpublished manuscripts documents King’s family roots, his rise to prominence, and influence as a national spokesperson for civil rights.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Martin Luther King Jr.

By: History.com Editors

Updated: January 25, 2024 | Original: November 9, 2009

Martin Luther King Jr. was a social activist and Baptist minister who played a key role in the American civil rights movement from the mid-1950s until his assassination in 1968. King sought equality and human rights for African Americans, the economically disadvantaged and all victims of injustice through peaceful protest. He was the driving force behind watershed events such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the 1963 March on Washington , which helped bring about such landmark legislation as the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act . King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 and is remembered each year on Martin Luther King Jr. Day , a U.S. federal holiday since 1986.

When Was Martin Luther King Born?

Martin Luther King Jr. was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia , the second child of Martin Luther King Sr., a pastor, and Alberta Williams King, a former schoolteacher.

Along with his older sister Christine and younger brother Alfred Daniel Williams, he grew up in the city’s Sweet Auburn neighborhood, then home to some of the most prominent and prosperous African Americans in the country.

Did you know? The final section of Martin Luther King Jr.’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech is believed to have been largely improvised.

A gifted student, King attended segregated public schools and at the age of 15 was admitted to Morehouse College , the alma mater of both his father and maternal grandfather, where he studied medicine and law.

Although he had not intended to follow in his father’s footsteps by joining the ministry, he changed his mind under the mentorship of Morehouse’s president, Dr. Benjamin Mays, an influential theologian and outspoken advocate for racial equality. After graduating in 1948, King entered Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania, where he earned a Bachelor of Divinity degree, won a prestigious fellowship and was elected president of his predominantly white senior class.

King then enrolled in a graduate program at Boston University, completing his coursework in 1953 and earning a doctorate in systematic theology two years later. While in Boston he met Coretta Scott, a young singer from Alabama who was studying at the New England Conservatory of Music . The couple wed in 1953 and settled in Montgomery, Alabama, where King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church .

The Kings had four children: Yolanda Denise King, Martin Luther King III, Dexter Scott King and Bernice Albertine King.

Montgomery Bus Boycott

The King family had been living in Montgomery for less than a year when the highly segregated city became the epicenter of the burgeoning struggle for civil rights in America, galvanized by the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954.

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks , secretary of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ( NAACP ), refused to give up her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery bus and was arrested. Activists coordinated a bus boycott that would continue for 381 days. The Montgomery Bus Boycott placed a severe economic strain on the public transit system and downtown business owners. They chose Martin Luther King Jr. as the protest’s leader and official spokesman.

By the time the Supreme Court ruled segregated seating on public buses unconstitutional in November 1956, King—heavily influenced by Mahatma Gandhi and the activist Bayard Rustin —had entered the national spotlight as an inspirational proponent of organized, nonviolent resistance.

King had also become a target for white supremacists, who firebombed his family home that January.

On September 20, 1958, Izola Ware Curry walked into a Harlem department store where King was signing books and asked, “Are you Martin Luther King?” When he replied “yes,” she stabbed him in the chest with a knife. King survived, and the attempted assassination only reinforced his dedication to nonviolence: “The experience of these last few days has deepened my faith in the relevance of the spirit of nonviolence if necessary social change is peacefully to take place.”

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

Emboldened by the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, in 1957 he and other civil rights activists—most of them fellow ministers—founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), a group committed to achieving full equality for African Americans through nonviolent protest.

The SCLC motto was “Not one hair of one head of one person should be harmed.” King would remain at the helm of this influential organization until his death.

In his role as SCLC president, Martin Luther King Jr. traveled across the country and around the world, giving lectures on nonviolent protest and civil rights as well as meeting with religious figures, activists and political leaders.

During a month-long trip to India in 1959, he had the opportunity to meet family members and followers of Gandhi, the man he described in his autobiography as “the guiding light of our technique of nonviolent social change.” King also authored several books and articles during this time.

Letter from Birmingham Jail

In 1960 King and his family moved to Atlanta, his native city, where he joined his father as co-pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church . This new position did not stop King and his SCLC colleagues from becoming key players in many of the most significant civil rights battles of the 1960s.

Their philosophy of nonviolence was put to a particularly severe test during the Birmingham campaign of 1963, in which activists used a boycott, sit-ins and marches to protest segregation, unfair hiring practices and other injustices in one of America’s most racially divided cities.

Arrested for his involvement on April 12, King penned the civil rights manifesto known as the “ Letter from Birmingham Jail ,” an eloquent defense of civil disobedience addressed to a group of white clergymen who had criticized his tactics.

March on Washington

Later that year, Martin Luther King Jr. worked with a number of civil rights and religious groups to organize the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, a peaceful political rally designed to shed light on the injustices Black Americans continued to face across the country.

Held on August 28 and attended by some 200,000 to 300,000 participants, the event is widely regarded as a watershed moment in the history of the American civil rights movement and a factor in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 .

"I Have a Dream" Speech

The March on Washington culminated in King’s most famous address, known as the “I Have a Dream” speech, a spirited call for peace and equality that many consider a masterpiece of rhetoric.

Standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial —a monument to the president who a century earlier had brought down the institution of slavery in the United States—he shared his vision of a future in which “this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.'”

The speech and march cemented King’s reputation at home and abroad; later that year he was named “Man of the Year” by TIME magazine and in 1964 became, at the time, the youngest person ever awarded the Nobel Peace Prize .

In the spring of 1965, King’s elevated profile drew international attention to the violence that erupted between white segregationists and peaceful demonstrators in Selma, Alabama, where the SCLC and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had organized a voter registration campaign.

Captured on television, the brutal scene outraged many Americans and inspired supporters from across the country to gather in Alabama and take part in the Selma to Montgomery march led by King and supported by President Lyndon B. Johnson , who sent in federal troops to keep the peace.

That August, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act , which guaranteed the right to vote—first awarded by the 15th Amendment—to all African Americans.

Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

The events in Selma deepened a growing rift between Martin Luther King Jr. and young radicals who repudiated his nonviolent methods and commitment to working within the established political framework.

As more militant Black leaders such as Stokely Carmichael rose to prominence, King broadened the scope of his activism to address issues such as the Vietnam War and poverty among Americans of all races. In 1967, King and the SCLC embarked on an ambitious program known as the Poor People’s Campaign, which was to include a massive march on the capital.

On the evening of April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King was assassinated . He was fatally shot while standing on the balcony of a motel in Memphis, where King had traveled to support a sanitation workers’ strike. In the wake of his death, a wave of riots swept major cities across the country, while President Johnson declared a national day of mourning.

James Earl Ray , an escaped convict and known racist, pleaded guilty to the murder and was sentenced to 99 years in prison. He later recanted his confession and gained some unlikely advocates, including members of the King family, before his death in 1998.

After years of campaigning by activists, members of Congress and Coretta Scott King, among others, in 1983 President Ronald Reagan signed a bill creating a U.S. federal holiday in honor of King.

Observed on the third Monday of January, Martin Luther King Day was first celebrated in 1986.

Martin Luther King Jr. Quotes

While his “I Have a Dream” speech is the most well-known piece of his writing, Martin Luther King Jr. was the author of multiple books, include “Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story,” “Why We Can’t Wait,” “Strength to Love,” “Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?” and the posthumously published “Trumpet of Conscience” with a foreword by Coretta Scott King. Here are some of the most famous Martin Luther King Jr. quotes:

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

“Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.”

“The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.”

“Freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

“The time is always right to do what is right.”

"True peace is not merely the absence of tension; it is the presence of justice."

“Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.”

“Free at last, Free at last, Thank God almighty we are free at last.”

“Faith is taking the first step even when you don't see the whole staircase.”

“In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.”

"I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality. This is why right, temporarily defeated, is stronger than evil triumphant."

“I have decided to stick with love. Hate is too great a burden to bear.”

“Be a bush if you can't be a tree. If you can't be a highway, just be a trail. If you can't be a sun, be a star. For it isn't by size that you win or fail. Be the best of whatever you are.”

“Life's most persistent and urgent question is, 'What are you doing for others?’”

Photo Galleries

HISTORY Vault: Voices of Civil Rights

A look at one of the defining social movements in U.S. history, told through the personal stories of men, women and children who lived through it.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

About Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Dr. king jr..

Drawing inspiration from both his Christian faith and the peaceful teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, Dr. King led a nonviolent movement in the late 1950s and ‘ 60s to achieve legal equality for African-Americans in the United States. While others were advocating for freedom by “any means necessary,” including violence, Martin Luther King, Jr. used the power of words and acts of nonviolent resistance, such as protests, grassroots organizing, and civil disobedience to achieve seemingly-impossible goals. He went on to lead similar campaigns against poverty and international conflict, always maintaining fidelity to his principles that men and women everywhere, regardless of color or creed, are equal members of the human family.

Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, Nobel Peace Prize lecture and “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” are among the most revered orations and writings in the English language. His accomplishments are now taught to American children of all races, and his teachings are studied by scholars and students worldwide. He is the only non-president to have a national holiday dedicated in his honor and is the only non-president memorialized on the Great Mall in the nation’s capital. He is memorialized in hundreds of statues, parks, streets, squares, churches and other public facilities around the world as a leader whose teachings are increasingly-relevant to the progress of humankind.

Some of Dr. King’s Most Important Achievements

In 1957 , Dr. King was elected president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), an organization designed to provide new leadership for the now burgeoning civil rights movement. He would serve as head of the SCLC until his assassination in 1968, a period during which he would emerge as the most important social leader of the modern American civil rights movement.

In 1963 , he led a coalition of numerous civil rights groups in a nonviolent campaign aimed at Birmingham, Alabama, which at the time was described as the “most segregated city in America.” The subsequent brutality of the city’s police, illustrated most vividly by television images of young blacks being assaulted by dogs and water hoses, led to a national outrage resulting in a push for unprecedented civil rights legislation. It was during this campaign that Dr. King drafted the “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” the manifesto of Dr. King’s philosophy and tactics, which is today required-reading in universities worldwide.

Later in 1963 , Dr. King was one of the driving forces behind the March for Jobs and Freedom, more commonly known as the “March on Washington,” which drew over a quarter-million people to the national mall. It was at this march that Dr. King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, which cemented his status as a social change leader and helped inspire the nation to act on civil rights. Dr. King was later named Time magazine’s “Man of the Year.”

Also in 1964 , partly due to the March on Washington, Congress passed the landmark Civil Rights Act, essentially eliminating legalized racial segregation in the United States. The legislation made it illegal to discriminate against blacks or other minorities in hiring, public accommodations, education or transportation, areas which at the time were still very segregated in many places.

The next year, 1965 , Congress went on to pass the Voting Rights Act, which was an equally-important set of laws that eliminated the remaining barriers to voting for African-Americans, who in some locales had been almost completely disenfranchised. This legislation resulted directly from the Selma to Montgomery, AL March for Voting Rights lead by Dr. King.

Between 1965 and 1968, Dr. King shifted his focus toward economic justice – which he highlighted by leading several campaigns in Chicago, Illinois – and international peace – which he championed by speaking out strongly against the Vietnam War. His work in these years culminated in the “Poor Peoples Campaign,” which was a broad effort to assemble a multiracial coalition of impoverished Americans who would advocate for economic change.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s less than thirteen years of nonviolent leadership ended abruptly and tragically on April 4th, 1968 , when he was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. Dr. King’s body was returned to his hometown of Atlanta, Georgia, where his funeral ceremony was attended by high-level leaders of all races and political stripes.

- For more information regarding the Transcription of the King Family Press Conference on the MLK Assassination Trial Verdict December 9, 1999, Atlanta, GA. Click Here

- For more information regarding the Civil Case: King family versus Jowers. Click here .

- Later in 1968, Dr. King’s wife, Mrs. Coretta Scott King, officially founded the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change, which she dedicated to being a “living memorial” aimed at continuing Dr. King’s work on important social ills around the world.

We envision the Beloved Community where injustice ceases and love prevails.

Contact Info

449 Auburn Avenue, NE Atlanta, Georgia 30312

404.526.8900

Quick Links

- History Timeline

- King Holiday

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

Latest News

- Spotlight on Women’s History Month with The King Center

- The King Center Joins the King Family in Mourning the Loss of Naomi Barber King, wife of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr’s Late Brother

Stay Connected

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Martin Luther King Jr.’s Legacy 60 Years After the March on Washington

Americans’ views of progress on racial equality, different forms of protest and what needs to change

Table of contents.

- King’s impact on the country

- King’s impact on personal views on racial equality

- Familiarity with King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech

- The country’s progress on racial equality in the last 60 years

- Efforts to ensure equal rights for all, regardless of race or ethnicity

- The future of racial equality

- 3. Achieving racial equality

- Acknowledgments

- The American Trends Panel survey methodology

Pew Research Center conducted this study to explore how Americans view the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. and the United States’ progress on racial equality 60 years after the March on Washington, which took place on Aug. 28, 1963.

This analysis is based on a survey of 5,073 U.S. adults conducted April 10-16, 2023. Everyone who took part is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. Address-based sampling ensures that nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Read more about the questions used for this report and the report’s methodology .

References to White, Black and Asian adults include those who are not Hispanic and identify as only one race. Hispanics are of any race.

All references to party affiliation include those who lean toward that party. Republicans include those who identify as Republicans and those who say they lean toward the Republican Party. Democrats include those who identify as Democrats and those who say they lean toward the Democratic Party.

On Aug. 28, 1963, about 250,000 people gathered at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom , where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his historic “I Have a Dream” speech advocating for economic and civil rights for Black Americans.

As the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington approaches, we asked Americans about their views on:

- King’s legacy

- The country’s progress on racial equality

- What needs to change in order to achieve racial equality

For this report, we surveyed 5,073 U.S. adults from April 10 to April 16, 2023, using Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel . 1

Key findings:

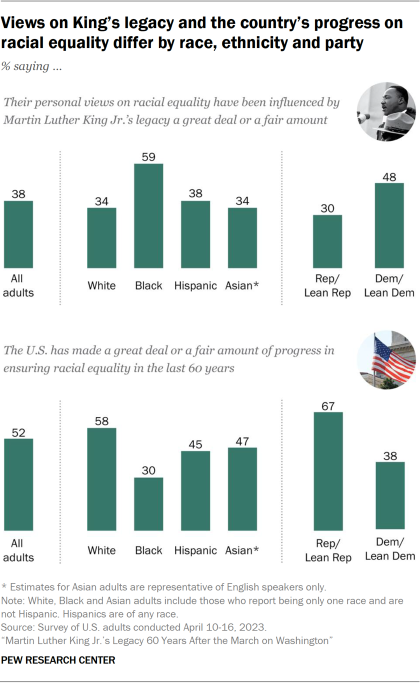

- Most Americans say King has had a positive impact on the country, with 47% saying he has had a very positive impact. Fewer (38%) say their own views on racial equality have been influenced by King’s legacy a great deal or a fair amount.

- 60% of Americans say they have heard or read a great deal or a fair amount about King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Black adults are the most likely to say this at 80%, compared with 60% of White adults, 49% of Hispanic adults and 41% of Asian adults.

- 52% of Americans say there has been a great deal or a fair amount of progress on racial equality in the last 60 years. A third say there’s been some progress and 15% say there has been not much or no progress at all. Still, more say efforts to ensure equality for all, regardless of race or ethnicity, haven’t gone far enough (52%) than say they have gone too far (20%) or been about right (27%).

- A majority (58%) of those who say efforts to ensure equality haven’t gone far enough think it’s unlikely that there will be racial equality in their lifetime. Those who say efforts have been about right are more optimistic: Within this group, 39% say racial equality is extremely or very likely in their lifetime, while 36% say it is somewhat likely and 24% say it’s not too or not at all likely.

- Many people who say efforts to ensure racial equality haven’t gone far enough say several systems need to be completely rebuilt to ensure equality. The prison system is at the top of the list, with 44% in this group saying it needs to be completely rebuilt. More than a third say the same about policing (38%) and the political system (37%).

- 70% of Americans say marches and demonstrations that don’t disrupt everyday life are always or often acceptable ways to protest racial inequality. And 59% say the same about boycotts. Fewer than half (39%) see sit-ins as an acceptable form of protest. And much smaller shares say the same about activities that disrupt everyday life, such as shutting down streets or traffic (13%) and actions that result in damage to public or private property (5%).

Demographic and partisan differences

These survey findings often differ by race, ethnicity and partisanship – and in some cases also by age and education.

Some examples:

- 59% of Black Americans say their personal views on racial equality have been influenced by Martin Luther King Jr. a great deal or a fair amount. Smaller shares of Hispanic (38%), White (34%) and Asian (34%) Americans say the same.

- Adults ages 65 and older and those with at least a bachelor’s degree are more likely than younger adults and those with less education to be highly familiar with King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

- 58% of White adults say there has been a great deal or a fair amount of progress on racial equality in the last 60 years. This compares with 47% of Asian adults, 45% of Hispanic adults and 30% of Black adults. Republicans and those who lean Republican (67%) are more likely than Democrats and Democratic leaners (38%) to say this.

- 83% of Black adults say efforts to ensure equality for all, regardless of race and ethnicity, haven’t gone far enough. This is larger than the shares of Hispanic (58%), Asian (55%) and White (44%) adults who say the same. Most Democrats (78%) say these efforts haven’t gone far enough, compared with 24% of Republicans. Some 37% of Republicans say these efforts have gone too far .

- Black Americans, Democrats and adults younger than 30 who say efforts to ensure racial equality haven’t gone far enough are among the most likely to say several systems, ranging from the economic system to the prison system, need to be completely rebuilt to ensure equality.

- Read more in the Methodology section of the report. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Black Americans

- Discrimination & Prejudice

- Partisanship & Issues

- Racial Bias & Discrimination

A look at Black-owned businesses in the U.S.

8 facts about black americans and the news, black americans’ views on success in the u.s., among black adults, those with higher incomes are most likely to say they are happy, fewer than half of black americans say the news often covers the issues that are important to them, most popular, report materials.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Martin Luther King Jr.

“Heed Their Rising Voices”: Annotated

“I Have A Dream”: Annotated

The Kerner Commission Report on White Racism, 50 Years On

Why MLK Believed Jazz Was the Perfect Soundtrack for Civil Rights

Colleges’ Reluctant Embrace of MLK Day

The African Roots of MLK’s Vision

How the Memphis Sanitation Strike Changed History

Martin Luther King Jr. in His Own Words

What Time is it When You Pass Through A Wrinkle in Time ?

How Septima Poinsette Clark Spoke Up for Civil Rights

Support jstor daily, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

- BU Libraries Home

- African Studies Library

- Astronomy Library

- Mugar Library

- Music Library

- Pardee Management Library

- Pickering Educational Resources Library

- Science & Engineering Library

- Stone Science Library

- All BU Library Locations

My Library Account Advanced Search Search Help

BU Libraries

Dr. martin luther king, jr. archive, finding aid and content.

View contents of this collection in Boston University ArchivesSpace

Download the Dr. King Collection finding aid and inventory [PDF]

About the Collection – Scope & Content Notes

The Martin Luther King, Jr. collection, donated in 1964, consists of manuscripts, notebooks, correspondence, printed material, financial and legal papers, a small number of photographs and other items dating from 1947 to 1963.

Manuscripts include class notes, examinations and papers written by Dr. King while a student at Morehouse College (1944-1948), Crozer Theological Seminary (1948-1951) and Boston University (1951-1953). Among the notable documents are: a paper entitled Ritual (1947), composed at Morehouse; An Autobiography of Religious Development (1950), an assignment for the “Religious Development of Personality” class at Crozer taught by one of King’s mentors, George W. Davis; and notes and drafts of his doctoral dissertation, A Comparison of the Conceptions of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman (1955). Additional manuscripts in the collection include drafts of speeches, sermons and three books: Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story (Harper, 1958), about the 1955-1956 bus boycott; Strength to Love (Harper & Row, 1963), a collection of several of his best-known sermons including “A Knock at Midnight,” “Shattered Dreams,” “The Death of Evil Upon the Seashore,” and “The Three Dimensions of a Complete Life;” and Why We Can’t Wait (Harper & Row, 1964), which includes the famed “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

Dr. King’s office files, which date from 1955 to 1963, make up the bulk of the collection and consist primarily of letters, but also include itineraries, financial and legal documents, printed items, news clippings, and similar documents. There is material related to both the Dexter Avenue Church in Montgomery, Alabama, and the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Georgia. Additionally, there are extensive files related to the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Other organizations which prominently figure include the American Friends Service Committee, which helped to finance Dr. King’s 1959 trip to India; the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE); the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); and the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA).

Notable correspondence from figures in the Civil Rights movement includes letters from Bayard Rustin, Malcolm X, Adam Clayton Powell, Ella J. Baker, Medgar Evers, Roy Wilkins, Rosa Parks, Maya Angelou, William Sloane Coffin, Allan Knight Chalmers, Sidney Poitier, Jackie Robinson, A. Philip Randolph, Harry Belafonte, and Ralph Abernathy. Distinguished U.S. Government correspondents include Alabama Gov. John Patterson, Robert F. Kennedy, Sargent Shriver, Paul Douglas, Prescott Bush, Ralph Bunche, Eleanor Roosevelt, Hubert Humphrey, Richard M. Nixon, Dean Rusk, Walter Reuther, Adlai Stevenson, Earl Warren, Harry S. Truman, and Lyndon B. Johnson. Other eminent correspondents include James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, Jawaharlal Nehru, Linus Pauling, Nat King Cole, Cass Canfield, Ralph Ginzburg, Julian Huxley, Paul Tillich, and Stanley Levison.

Photographs in the collection include images of King with his family and congregation, a formal portrait, a photograph of the knife with which he was stabbed in 1958, and his coffin being transported by airplane.

Awards for King in the collection include an honorary Doctor of Divinity diploma from the Chicago Theological Seminary (1957); a certificate from the Alabama Association of Women’s Clubs (1957); Man of the Year Award from the Capital Press Club (1957); the Social Justice Award from the Religion and Labor Foundation (1957); the New York City proclamation of May 16, 1961 as “Desegregation Day” in honor of King, by Mayor Robert Wagner (1961); a citation from Americans for Democratic Action (1961); a certificate from the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (1963); an award from the Institute of Adult Education, Our Lady of Mt. Carmel, Bayonne, New Jersey (1964); and King’s certificate of membership in the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity at Boston University.

Audio in the collection includes recordings of King delivering a speech at Bennett College in Greensboro, North Carolina (1958); an interview with Bayard Rustin (1963); King’s visit to Boston University in 1964 to donate his papers; King giving a speech at the Golden Jubilee Convention of the United Synagogues of America (Nov. 19, 1964); King speaking to District 65 DWA; and King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

Other items in the collection include telephone log books (1961–1963); King’s diary regarding his arrest on July 27, 1962; numerous clippings, pamphlets, flyers, articles, and other printed items; and a monogrammed leather briefcase owned by King. An addendum to the collection includes correspondence pertaining to the Joan Daves Agency’s dealings with King and the King Estate. These letters date from 1958 to 1993 and cover advertising and promotion, King’s Massey Lectures (1967), publishing rights, permissions, and other subjects.

Facsimiles of select materials are available on permanent display in the Martin Luther King Jr. Reading Room on the 3rd floor of the Mugar Memorial Library .

- Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center

- Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

- Elie Wiesel

- Partisan Review

- Rules for Access and Use

- Exhibitions

- About the Gotlieb Center

Library News

- Apr 30, 2024 Mugar open 24 hours with overnight shuttle for study period and finals Memorial Library will be open 24 hours per day beginning on Wednesday,...

- Apr 16, 2024 African Studies Library hosts visitors from the US Department of State’s IVL Program The BU Libraries recently welcomed two delegations from U.S. Department of State's......

- Apr 12, 2024 Upcoming Event: SARPtastic Read & Raffle on April 18 The BU Libraries and BU’s Sexual Assault Response & Prevention Center, known......

Boston University

Libraries & Archives

- Alumni Medical Library

- Fineman & Pappas Law Libraries

- Mugar Memorial Library

- Pardee Management Library

- Science & Engineering Library

- Theology Library

- Additional BU Libraries

Boston University Libraries, 771 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, MA 02215 | Reference Desk: 617-353-2700

Celebrate the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. with the University Libraries

This year University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill honors the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. with the theme “The Time is Now.” To coincide with this celebration, the University Libraries has gathered this list of books, films and other materials to help you learn about King’s impact and engage with his ideals.

E-books and Audiobooks

Throughout January, the University Libraries’ Honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. OverDrive collection will highlight dozens of books on topics related to King’s legacy. From King’s own Where Do We Go from Here to John Lewis’s co-authored graphic novel March , you can engage with the history and impact of King’s work and the movement he helped lead.

Films

The Media & Design Center has created a list of films about King and his legacy, which can be accessed via streaming, DVD or VHS. (The center can also provide devices to play physical media). Films include Selma , Tony Brown’s essay on Martin Luther King Jr. and In Remembrance of Martin .

Selected Materials from the Wilson Special Collections Library

Collections in Wilson Library contain materials related to Martin Luther King Jr., including MLK buttons, a vintage church hand fan bearing King’s image and recordings of King’s speeches.

There are also some materials that you can access online. For example, have you ever wondered how the University reacted to news about the assassination of King? What happened at Carolina’s first MLK celebration in 1982? Blog posts from the University Archives take a look back at these moments in University history.

Wilson Library also holds recordings featuring Dr. King. For example, you can hear him in a 1963 mass meeting along with Ralph Abernathy in this recording from the Guy and Candie Carawan Collection . King discusses the historical significance of the civil rights movement in Birmingham, the importance of perseverance and unity, and jailing of children and other participants in the civil rights movement, among other topics.

The Carawan Collection also includes a press conference from the same year featuring King, Abernathy and Fred Shuttlesworth. The three address questions about the details of negotiations between leaders of the civil rights movement and business leaders and public officials, as well as specific developments in the civil rights movement in the preceding weeks. ( Part 1 ; Part 2 ; Part 3.)

This collection of resources was first published in January of 2023. It was updated in January 2024.

Motives and Influences: Unraveling the Reasons Behind James Earl Ray’s Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

This essay about James Earl Ray’s assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. examines the complex motives behind the act, attributing it to Ray’s troubled upbringing, racist ideologies, and the racially charged atmosphere of the 1960s. It discusses how King’s leadership in the civil rights movement positioned him as a target for those resistant to change, and considers conspiracy theories suggesting Ray might not have acted alone. The essay highlights the broader societal impact and the personal failings that drove Ray to commit this historic crime.

How it works

James Earl Ray’s assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, stands as one of the most significant and tragic events in American history. The killing not only marked the end of the life of one of the most influential civil rights leaders but also sent shockwaves through the fabric of American society, altering the course of the civil rights movement and shaping the national conversation about race and justice. Understanding the motives and influences behind Ray’s decision to assassinate King involves delving into a complex interplay of personal beliefs, societal tensions, and historical context.

James Earl Ray was born in 1928 in Alton, Illinois, into a poor and tumultuous family background marked by crime and instability. His early life was characterized by a series of petty crimes, leading to repeated incarcerations. This pattern of criminal behavior indicates a troubled upbringing devoid of positive role models, which could have played a significant role in shaping his worldview.

Historians and psychologists have suggested that Ray’s motives for assassinating King were deeply rooted in a personal ideology laced with racism and resentment. The 1960s in America were a period of intense racial strife, and King was at the forefront of the civil rights movement, advocating for equality and justice for African Americans. This advocacy was seen by many, including Ray, as a threat to the existing social order. Ray’s racist beliefs, likely reinforced by his time in Missouri State Penitentiary—a place known for its own racial tensions—may have motivated him to target King, whom he possibly viewed as the epitome of the forces altering his perceived world.

Additionally, the influence of the broader societal context cannot be overlooked. The 1960s were marked by significant civil rights activities, legislative changes, and an overall push towards racial equality. King, as a prominent leader of this movement, often became a symbolic figure both for those who supported the cause and those who opposed it. For individuals like Ray, who harbored deep-seated racial prejudices, the changes being advocated threatened their sense of identity and security. King’s prominence and influence made him a focal point for this animosity.

Conspiracy theories have also surrounded the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., with some suggesting that Ray was not acting alone but was part of a larger plot orchestrated by forces opposed to the civil rights movement. These theories, though not conclusively proven, point to the possibility of external influences on Ray, including interactions with individuals or groups who shared his ideological leanings. The FBI’s intense surveillance and hostility towards King under J. Edgar Hoover’s leadership reflect the extent of institutional antagonism towards the civil rights leader, which could have indirectly emboldened individuals like Ray.

The decision to assassinate King could also be seen as a twisted bid for recognition and notoriety. Ray’s life, marked by failures and frequent imprisonments, was devoid of any significant achievements. In his distorted view, targeting a high-profile leader like King could have been seen as an act that would finally grant him a place in history, albeit for a heinous act. This desire for recognition, combined with his ideological leanings and the racially charged environment of the time, might have culminated in the fateful decision to assassinate King.

In conclusion, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. by James Earl Ray was the result of a confluence of personal, societal, and possibly conspiratorial factors. Ray’s troubled background, imbued with criminal activities and racist ideologies, intersected with a period of significant racial tension and transformation in the United States. King’s role as a leader and symbol of the civil rights movement made him a target for those who felt threatened by the changes he championed. Understanding these layers of motivation provides insight into not only the mind of an assassin but also the turbulent times in which these events unfolded.

Cite this page

Motives and Influences: Unraveling the Reasons Behind James Earl Ray’s Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.. (2024, May 12). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/motives-and-influences-unraveling-the-reasons-behind-james-earl-rays-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr/

"Motives and Influences: Unraveling the Reasons Behind James Earl Ray’s Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.." PapersOwl.com , 12 May 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/motives-and-influences-unraveling-the-reasons-behind-james-earl-rays-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Motives and Influences: Unraveling the Reasons Behind James Earl Ray’s Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/motives-and-influences-unraveling-the-reasons-behind-james-earl-rays-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr/ [Accessed: 16 May. 2024]

"Motives and Influences: Unraveling the Reasons Behind James Earl Ray’s Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.." PapersOwl.com, May 12, 2024. Accessed May 16, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/motives-and-influences-unraveling-the-reasons-behind-james-earl-rays-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr/

"Motives and Influences: Unraveling the Reasons Behind James Earl Ray’s Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.," PapersOwl.com , 12-May-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/motives-and-influences-unraveling-the-reasons-behind-james-earl-rays-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr/. [Accessed: 16-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Motives and Influences: Unraveling the Reasons Behind James Earl Ray’s Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/motives-and-influences-unraveling-the-reasons-behind-james-earl-rays-assassination-of-martin-luther-king-jr/ [Accessed: 16-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

70 Years of Abandonment: The Failed Promise of ‘Brown v. Board’

- Share article

Editor’s note: For additional perspectives on the 70th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education , Education Week Opinion Contributor Bettina L. Love invited R. L’Heureux Lewis-McCoy to contribute an essay for a brief series on the U.S. Supreme Court decision.

Ten years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., while speaking at The New School in New York City, told the crowd : “The Negro had been deeply disappointed over the slow pace of school desegregation. … At the beginning of 1963, nine years after this historic decision, approximately 9 percent of Southern Negro students were attending integrated schools. If this pace were maintained, it would be the year 2054 before integration in Southern schools would be a reality.”

While King’s insightful analysis primarily centers on the South, it would be incomplete not to mention that several Northern cities, including Boston , New York City , and Philadelphia viciously resisted school integration, oftentimes picking up arms to keep schools white .

White America’s outright rejection of school integration from the onset is far from over, even as this year marks the 70-year anniversary of Brown . The case was intended to overturn the Plessy v. Ferguson doctrine known as “separate but equal,” but what children of color have endured since the 1954 ruling is a resistance so powerful, so pervasive, and full of white rage that it has created a public school system that is separate and unequal by design to not only appease white dissent but to ensure a racial caste. Seventy years after Brown , public schools across the country are still deeply segregated and unequal .

Atlanta, the city that birthed and raised Rev. King, is also the city I have called home for over 20 years. Although it is known for its racial progress, Atlanta’s racial disparities are so repugnant that injustice is the norm. Public officials would like Atlantans to believe that these injustices are a special condition of circumstance, not structure.

According to the 2020 census data , Atlanta’s population was nearly 50 percent Black and 40 percent white; however, white residents have 46 times more wealth than Black residents . In its 2022 working paper, the National Bureau of Economic Research reported that the racial wealth gap in the United States in 2020 was “effectively the same value” as it was in the 1950s.

In 2022, 7 of the 10 public high schools in Atlanta did not have a single white student in attendance, according to Kamau Bobb, who served as an alternate on the city’s superintendent-search panel. In one of the three remaining schools that are integrated, white students are overrepresented in the International Baccalaureate program, essentially carving out primarily white elite private schools within public schools with public dollars. This level of segregation is cynically unsurprising in a city with a wealth gap akin to the days of the civil rights movement.

Moreover, nationwide data from the fall of 2022 shows that 75 percent of white students in America went to majority-white public schools.

School integration is no longer moving at a slow pace, it is in reverse motion “with all deliberate speed” because Brown continues to be gutted legislatively, locally, and at the school level. Immediately after the Brown ruling, segregation academies were opened in the South and received federal tax exemptions . In 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court decided in San Antonio Independent School District v . Rodriguez that funding schools based on local property taxes rather than equally distributing funding among all school districts did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause, effectively allowing unequal school funding to continue.

According to a 2019 report from EdBuild for the 2015-16 school year, a $23 billion funding gap exists between white school districts and districts that serve Black and brown students even as “they serve the same number of children.”

The 1974 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Milliken v. Bradley , in a major setback to Brown , rejected a desegregation plan that encompassed the Detroit school district and the neighboring suburban school districts, which were all-white. The Court exempted the suburban districts from the desegregation plan, holding that the district lines had not been drawn with a racist intent and therefore were not responsible for Detroit’s segregated schools. In his dissenting opinion, Justice Thurgood Marshall , joined by three other justices, wrote: “Under such a plan, white and Negro students will not go to school together. Instead, Negro children will continue to attend all-Negro schools. The very evil that Brown 1 was aimed at will not be cured but will be perpetuated for the future.”

Today, the last vestiges of Brown ’s legacy are fading quickly. According to recent UCLA data from the Civil Rights Project , intensely segregated public schools (with a zero percent to 10 percent white student population) nearly tripled over the last 30 years nationwide, rising from 7.4 percent to 20 percent.

We must take a critical look at the fundamental issue: If this nation is going to outright refuse integration through every possible personal, political, and legislative measure, then Black people must demand this country revisit the separate but equal doctrine. Centuries have taught us that we cannot force this country to live up to the promise of integration.

As we mark the 70-year anniversary of a decision this country has clearly shown it never intended to uphold beyond the window dressing of the rhetoric of integration, let us turn to the reality and not idealism. Our schools are separate, and most white Americans appear unwilling to integrate them based on the evidence. So, if separate is the reality for millions of Black and brown students for the foreseeable future, the demand needs to be for reparations .

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. Volume I

Volume I begins with the childhood letters Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote to his mother and father.

A series of letters written while he was working at a summer job on a tobacco farm in Connecticut reveal his initial impressions of life outside the segregated South. A few years later, King would refer to this time as a crucial period in his religious evolution when he “felt and inescapable urge to serve society... in a sense of responsibility which I could not escape.”

As a teenager at Morehouse College, the young King initially planned to become a lawyer or physician rather than become a minister like his father. Greatly affected by the influence of Morehouse College’s president Benjamin E. Mays, King described his studies at Morehouse as “very exciting.” He persistently questioned literal interpretations of biblical texts and criticized traditional Baptist teachings. But by his senior year, he decided to follow his father’s “noble example” into the ministry. King’s continuing struggle to resolve his religious doubts is revealed in the essays and examinations written while he was at Crozer Theological Seminary in Philadelphia. The intensity of his search for a sense of theological certainty and the depth of his deliberations regarding his ultimate decision to accept his religious calling are clearly revealed. By the time he left Crozer, he had found new value in his early religious experiences and had reached enduring conclusions about his own faith.

Download Introduction to Volume 1 (pdf)

Chronology

In this publication, crozer theological seminary placement committee: confidential evaluation of martin luther king, jr., by george w. davis.

Davis, George W. (Washington) (Crozer Theological Seminary) November 15, 1950

To Martin Luther King, Sr.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. January 18, 1940

More Publications

The papers of martin luther king, jr. volume v, the papers of martin luther king, jr. volume iii, the martin luther king, jr., encyclopedia.

The New York Sun

The radically different lives of martin luther king jr. and john lewis.

Lewis’s vulnerability disarms his biographer, whereas King for all his noble rhetoric and moral suasion had a crass side that permits a biographer to be a little more earthy than this one.

‘King: A Life’ By Jonathan Eig Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 688 pages

‘John Lewis: In Search of the Beloved Community’ By Raymond Arsenault Yale University Press, 588 pages

John Lewis first shows up in Jonathan Eig’s trenchant biography as the kind of courageous and determined civil rights activist that Martin Luther King Jr., a brilliant preacher but no organizer, depended on.

Lewis suffered blows that boxer Muhammad Ali, one of Mr. Eig’s other subjects, never had to endure — such as getting hit on the head with a Coca-Cola crate aboard a Freedom Riders bus protesting segregation. Raymond Arsenault continues the story, describing Lewis as he went down, his knees collapsing, everything turning white, then black, as he lost consciousness.

Lewis sometimes took a harsher tone than King, wary of the Kennedy administration’s effort to mollify civil rights protestors; King, in Mr Eig’s account of the March on Washington, surveyed the gathering of something like 250,000 people and approached the podium with a slight smile, even as those closest to him watched for anyone who looked suspicious.

While Lewis and other radical figures like Malcolm X advocated militant action, King, in Mr. Eig’s words, “saw strength in restraint,” which gave the white supremacists no cause to cast civil rights leaders as aggressive.

Mr. Eig announces that he “seeks to recover the real man from the gray mist of hagiography: canonized by the “I Have a Dream” speech. The biographer credits King with bringing the nation “closer than it had ever been to reckoning with the reality of having treated people as property and secondary citizens,” but he also wants to recall the man who “chewed his fingernails, twice attempted suicide as an adolescent, depended on his wife Coretta and cheated on her compulsively.”

Mr. Arsenault begins his biography in a different realm from King’s — not in urban Alabama as a preacher’s son, but in the state’s cotton fields, in a “static rural society seemingly impervious to change and mobility.”

More than other civil rights leaders, Lewis ended up behind bars with a “bandage on his head,” as Mr. Arsenault reports. Lewis believed that a leader had to be blooded to “help redeem the soul of America.” Yet he never turned bitter, no matter how militant he might sound. He went beyond King in forays into the political system, so that, in Mr. Arsenault’s words, he “won recognition as ‘the conscience of Congress.’”

Mr. Arsenault ranks Lewis with a “small number of other transcendent historical figures — Martin Luther King Jr., Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman” — an appropriate assemblage since Lewis grew up in the Black Belt, not that far distant from the enslavement that Tubman and Douglass escaped and excoriated.

It is less likely that Lewis would have developed so quickly as a leader without King, whose words, Lewis said, set him on fire, articulating “everything I’d been feeling and fighting to figure out for years.”

How biographies present their subjects depends not only on style and structure but on what can be known about the subject and the subject’s conduct. While Mr. Arsenault desires to get at Lewis’s private experiences, the biographer’s approach seems a little tender — not surprising since Lewis inspired extraordinary sensitivity in those he met and worked with.

Lewis’s vulnerability disarms his biographer, whereas King for all his noble rhetoric and moral suasion had a crass side that permits a biographer to be a little more earthy than Mr. Arsenault, who acknowledges the strain of telling an admirable man’s story while avoiding, he says, “hero worship.”

Mr. Arsenault has written a biography that has quite a different feel from Mr. Eig’s, since Mr. Arsenault enjoyed a 20-year friendship with his subject, and in that time did not see a dark side that went beyond what he calls “mistakes and misjudgments.” If the biographer comes close to hagiography — in spite of protestations to the contrary — it may be because this is the subject he had to work with, open-minded and assertive, but also just shy enough to make it difficult to find any significant fault with him.

Mr. Rollyson is the author of “A Higher Form of Cannibalism? Adventures in the Art and Politics of Biography.”

Mr. Rollyson is the author of The Life of William Faulkner and The Last Days of Sylvia Plath. He has published fourteen biographies and has written about biography for The Wall Street Journal, The Washington, Post, The San Francisco Chronicle, The New Criterion, and other publications.

© 2024 The New York Sun Company, LLC. All rights reserved.

Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy . The material on this site is protected by copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, cached or otherwise used.

Sign in or create a free account

COMMENTS

Introduction. Martin Luther King, Jr., made history, but he was also transformed by his deep family roots in the African-American Baptist church, his formative experiences in his hometown of Atlanta, his theological studies, his varied models of religious and political leadership, and his extensive network of contacts in the peace and social ...

Building upon the achievements of Stanford University's Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project, the King Institute supports a broad range of educational activities illuminating Dr. King's life and the movements he inspired. ... The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. Web Login Address. Cypress Hall D 466 Via Ortega ...

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project has made the writings and spoken words of one of the twentieth century's most influential figures widely available through the publication of The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., a projected fourteen-volume edition of King's most historically significant speeches, sermons, correspondence, published writings, and unpublished manuscripts.

Enlarge Martin Luther King, Jr. at the Soviet Border of the Berlin Wall, 1964. View in National Archives Catalog Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was born in Atlanta, GA on January 15th, 1929. He was one of the most important and influential Civil Rights leaders in the 1950s and 1960s. The cornerstones of his activism were based on non-violence and civil disobedience, both of which were inspired by ...

This edition of speeches, sermons, correspondence, and other papers of America's foremost leader of the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The project was initiated by the King Center in Atlanta before moving to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford. Seven completed volumes of a planned 14-volume ...

Source: MLKP-MBU, Martin Luther King, Jr., Papers, 1954-1968, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center, Boston University, Boston ... The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. Web Login Address. Cypress Hall D 466 Via Ortega Stanford, CA 94305-4146 United States. Facebook; Twitter; P: (650) 723-2092 F: (650) 723-2093 ...

Primary Sources. The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. (Vols. 1-6) by Clayborne Carson, Ralph E. Luker, and Penny A. Russell, Eds. Call Number: E185.97.K5 A2 1992. Publication Date: 1992. More than two decades since his death, Martin Luther King, Jr.'s ideas - his call for racial equality, his faith in the ultimate triumph of justice, and his ...

Although African American writers and politicians used the term "Black Power" for years, the expression first entered the lexicon of the civil rights movement during the Meredith March Against Fear in the summer of 1966. Martin Luther King, Jr., believed that Black Power was "essentially an emotional concept" that meant "different ...

Martin Luther King, Jr. (born January 15, 1929, Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.—died April 4, 1968, Memphis, Tennessee) was a Baptist minister and social activist who led the civil rights movement in the United States from the mid-1950s until his death by assassination in 1968. His leadership was fundamental to that movement's success in ending the ...

The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. Division of Research Programs. Photo caption. This definitive edition of Dr. King's most significant speeches, sermons, correspondence, public statements, published writings and unpublished manuscripts documents King's family roots, his rise to prominence, and influence as a national spokesperson for ...

Early histories of the civil rights movement that appeared prior to the 1980s were primarily biographies of Martin Luther King, Jr. Collectively, these works helped to create the familiar "Montgomery to Memphis" narrative framework for understanding the history of the civil rights movement in the United States.

Stephen F. Somerstein/Getty Images. Martin Luther King Jr. was a social activist and Baptist minister who played a key role in the American civil rights movement from the mid-1950s until his ...

During the less than 13 years of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s leadership of the modern American Civil Rights Movement, from December 1955 until April 4, 1968, African Americans achieved more genuine progress toward racial equality in America than the previous 350 years had produced. Dr. King is widely regarded as America's pre-eminent advocate of nonviolence and one of the greatest ...

Initiated by The King Center in Atlanta, the Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project is one of only a few large-scale research ventures focusing on an African American. In 1985, King Center's founder and president Coretta Scott King invited Stanford University historian Clayborne Carson to become the Project's director. Mission of the Papers Project

Pew Research Center conducted this study to explore how Americans view the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. and the United States' progress on racial equality 60 years after the March on Washington, which took place on Aug. 28, 1963. This analysis is based on a survey of 5,073 U.S. adults conducted April 10-16, 2023.

Martin Luther King, Jr.'s iconic speech, annotated with relevant scholarship on the literary, political, and religious roots of his words. Education & Society. The Kerner Commission Report on White Racism, 50 Years On. ... Research about intellectual humility has exploded in the past decade. Psychologist Elizabeth Krumrei-Mancuso offers an ...

The Martin Luther King, Jr. collection, donated in 1964, consists of manuscripts, notebooks, correspondence, printed material, financial and legal papers, a small number of photographs and other items dating from 1947 to 1963. Manuscripts include class notes, examinations and papers written by Dr. King while a student at Morehouse College (1944 ...

The Martin Luther King Jr. Papers Project addresses authorship issues on pp. 25-26 of Volume II of The Papers of Martin Luther King Jr., entitled "Rediscovering Precious Values, July 1951 - November 1955", Clayborne Carson, Senior Editor. Following is an excerpt from these pages:

such as power abuse, inequality, and dominance. Chiefly, this paper will present a conducted research on. Martin Luther's king "I have a dream" using Critical di scourse analysis methodology ...

"The Influence of the Mystery Religions on Christianity" is an essay written from November 29, 1949, to February 15, 1950, by Martin Luther King Jr. It was written for a course on "The Development of Christian Ideas" at the Crozer Theological Seminary taught by George Washington Davis, who gave it an A grade. It duplicates some material from "A Study of Mithraism" (1949), a previous essay King ...

Martin Luther King Jr. was a towering figure in the civil rights movement of the 20th century, renowned for his unwavering commitment to nonviolent protest and his advocacy for racial equality and social justice. Through his eloquent speeches, including the iconic "I Have a Dream", King inspired millions to join the fight against racial discrimination and systemic oppression.

The Media & Design Center has created a list of films about King and his legacy, which can be accessed via streaming, DVD or VHS. (The center can also provide devices to play physical media). Films include Selma, Tony Brown's essay on Martin Luther King Jr. and In Remembrance of Martin. Selected Materials from the Wilson Special Collections ...

Essay Example: James Earl Ray's assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, stands as one of the most significant and tragic events in American history. The killing not only marked the end of the life of one of the most influential civil rights leaders but also sent shockwaves

Board of Education decision, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., while speaking at The New School in New York City, told the crowd: "The Negro had been deeply disappointed over the slow pace of ...

Explore the first volume of the papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., covering his early life and education, his call to serve as a pastor, and his involvement in the civil rights movement. Learn about his personal and professional achievements, his challenges and struggles, and his vision for a more just and peaceful world.

Mr. Arsenault ranks Lewis with a "small number of other transcendent historical figures — Martin Luther King Jr., Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman" — an appropriate assemblage since Lewis grew up in the Black Belt, not that far distant from the enslavement that Tubman and Douglass escaped and excoriated.

Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote, "Education must enable one to sift and weigh evidence, to discern the true from the false, the real from the unreal, and the facts from the fiction."