- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

‘How’s this for a beginning?’: the tricky work of writing the story of Australian history

Anna Clark set out to write the history of Australian history. In grappling with the past, she faced up to the giants in her own family

- Get our weekend culture and lifestyle email and listen to our podcast

A nna Clark took seven years to write her latest book, Making Australian History, but it seems a wonder it didn’t take her twice as long. During her many years of research, the 43-year-old celebrated author and historian wasn’t at all sure what her opening chapter ought to be.

Perhaps that’s not surprising when you consider the almost limitless scope of the ambitious challenge she set herself: to write what is, effectively, a history of Australian history.

A chronological approach common to so much academic and popular history wasn’t going to cut it. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander experience – those thousands of generations, those 60-plus millennia (and counting) of human experiences that span time, place and cosmology in a way that challenges non-Indigenous sensibility and intellect – is, of course, omnipresent.

But how to explain that in any “traditional” chronological history that aimed to examine what we call “Australian history”, with all its vagaries and ongoing cultural skirmishes, political captivations, blind spots and deliberate omissions?

“For example, the term ‘ Deep Time’ – history that’s tens of thousands of years old – has only come into use relatively recently,” Clark ponders in her early pages. “Does that mean it goes at the beginning or the end of a history of Australian History?”

Clark, whose previous work has won major history awards and who holds an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship at the Australian Centre for Public History at UTS, Sydney, says she “just didn’t know how to do it”.

“And then I thought, ‘What if I did chapter 1 as a history of chapter ones which shows how the idea of chapter ones change over time?’” she says.

This, in turn, helped her to devise a structure whereby each chapter – among them “Nation”, “Memory”, “Contact”, “Colour”, “Family” (about which, more, shortly) and “Gender” – is propelled by the interrogation of a text or image.

So, for example, “Chapter 0, Making histories” contemplates the Dyarubbin (Aboriginal) rock engraving Woman in a crinoline dress, while “Chapter 1, Beginnings” launches off from The History of New Holland, From Its First Discovery in 1616 to the Present Time – published in London in the pre-invasion year, 1787.

Chapter 1 begins: “How’s this for a beginning?”

Not bad, you’d have to say, given the inherent provocation of The History of New Holland, this country’s first “history”, published before the cataclysmic clash of civilisations that gathered pace with the First Fleet’s arrival a year later.

It works. Clark is a wonderful historian, one of her generation’s best. As a writer she is also an admirable stylist. Possessed of a novelist’s eye for detail, her tone is distinctively, laconically, Australian, her elegant prose marked by clarity and an absence of old-school academic pomposity and verbosity.

This won’t surprise any who know of Clark’s commitment to democratising what she does in the name of “public history” and of her other work including Private Lives, Public History and her wonderful story of Australian fishing, The Catch.

Clark will tell you that she is an obsessive “fisho” and is most comfortable about – or under – the sea.

Once she’d nailed the structure of Making Australian History, Clark spent precious, memorable months writing at a secluded south coast New South Wales family property, Ness, near Wapengo. Her family lived there during her long service leave in 2019, then through the Covid lockdown in 2020.

“I wrote according to the tides so that I could go fishing. And I thought about place a lot. And particularly, you know, Country. And changing conceptions of Country,” she says.

“I was really struck by living in the bush for that long and how much it affected how I thought about the past. You know, walking down to the beach you would be walking through middens every day – so someone had obviously been there thinking about this place and eating from it and even making histories on it for a really long time – several thousand generations.

“And it definitely made me think about the timelines and that question that I brought up earlier – you know, when does Australian history begin? And if it begins in deep time, how do we register those histories of Australia from back then?”

Making Australian History is replete with that pervasive tension between the stories of the past that early colonial historians – and many of the 20th century – chose to record as having happened on the continent and those they thought a “proud” new nation shouldn’t remind itself of.

The violence of Indigenous dispossession – the land grabs, massacres and attempted genocide – and the unsavoury convict experience wouldn’t do. And federation in 1901, she says, did not feel like a relatable human experience. Gallipoli filled the breach.

“They [early 20th-century historians] were really looking for an origin story … They had a nation and it clearly had a history but it wasn’t really up to scratch … with the convict legend and frontier violence. Those two profound origin stories weren’t the uplifting national narratives that a proud Australia should have,” Clark says.

“It [Anzac] shows that even though that history is confected and highly curated, obviously for it to have that endurance it does hang on many threads of genuine connectedness to many people, as opposed to the federation narrative, for example, which is not really about the people.”

Sign up for the fun stuff with our rundown of must-reads, pop culture and tips for the weekend, every Saturday morning

Another tension Clark had to wrestle was how her history of Australian history would deal with the work of Manning Clark , this country’s pre-eminent 20th-century historian – and her paternal grandfather. It was not an easy emotional hurdle for Clark who, as an undergraduate Arts student, avoided doing history until a timetable clash made it unavoidable.

How did she reckon with the titanic legacy of Manning when she began, finally, studying – and loving – Australian history?

“I pretended I wasn’t connected to him. I just sort of didn’t talk about him. Ever. I’ve tried to totally separate my professional life from my family life and he died when I was 12 so to me he really was just my granddad … it was almost like I had just managed to separate it somehow,” she says.

“And even when I conceived of this project – and I can’t believe I’m saying this now – I sort of didn’t really think that I would have to mention him, or that if I did, that I would have to mention him in a particular way.”

It is a mark of Clark’s modesty – well known to friends and colleagues – that she was concerned detailing her grandfather’s legacy (on her and the nation) might be misinterpreted as “self-indulgent”.

Ultimately, she dealt squarely with Manning Clark’s contribution to the nation’s understanding of itself throughout the book – not least in a chapter on family histories.

She says, “I don’t have any misgivings about my love for him. You know, I really did love him very much. But in order just to feel like I was making my own mark, I suppose, I didn’t always want to be known as Manning’s granddaughter.”

Making Australian History by Anna Clark is out now through Vintage Australia

- Australian books

- History books

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

What is ‘Deep Time’ history of the First Nations People of Australia?

When we think of history, we often think of events that happened in the last few centuries or millennia. But history is much more than that.

History is the story of life on Earth, and it goes back billions of years. This is what we call 'Deep Time'.

Deep Time is the concept that the Earth and its inhabitants have a long and complex history that spans geological eras and evolutionary changes.

It is a way of understanding the natural world and our place in it.

Deep Time in Australian First Nations' histories

But Deep Time is not only a scientific idea. It is also a cultural and spiritual one. For Australia's First Nations peoples , Deep Time is part of their identity and worldview.

They have lived in Australia for more than 60,000 years , making them one of the world's oldest continuous cultures.

During this time, they have witnessed and adapted to many environmental and climatic changes.

As a result, they have developed belief systems that reflect their deep connection to the land, the sea and the sky.

In addition, their stories, traditions , and knowledge systems have been passed down through countless generations.

It has produced a unique understanding of the Australian landscape and its evolution.

How indigenous peoples remember Deep Time

It is important to note that the history of Australia's First Nations peoples is not written in books or documents.

Instead, it is said to be written in the landscape , in the stories, in the objects, in the ceremonies and in the memories.

In this way, it is a living history that is passed down from generation to generation.

Here are some specific ways that First Nations People remember Deep Time:

Dreamtime stories

Central to Indigenous Australian cosmology are the Dreamtime stories. These narratives explain the origins of the land, its features, and the creatures that inhabit it.

They are also deeply rooted in the present. When the stories are shared, they help teach the social norms, laws, and spiritual beliefs to new generations.

Land management

The deep connection to the land is evident in the sophisticated land management practices of Indigenous Australians.

Through controlled burns, water resource management, and sustainable hunting and gathering, they shaped the Australian landscape in harmony with its natural rhythms.

Art and expression

While often forgotten, ancient rock art found across Australia also serves as a testament to the deep history of First Nations peoples.

These artworks, some dating back over 17,000 years, capture the evolving relationship between humans and their environment.

Deep Time: A bridge to understanding

For many non-Indigenous Australians, understanding the depth and complexity of First Nations history can be challenging.

As a result, the concept of Deep Time can serve as a bridge: by grasping the vastness of time, one can begin to appreciate the depth of Indigenous connection to the land.

It's not just about recognizing that Indigenous Australians have been on the continent for a very long time; it's about understanding that their culture, knowledge, and traditions have evolved and been refined over these immense time scales.

This perspective can foster a deeper respect for Indigenous knowledge systems and their contributions to modern Australia.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

- Search Catalogue

- Search Bookshop

- Search Website

- Search Societies

The knowledge solution: Australian history: What place does history have in a post-truth world? edited by Anna Clark

What can we learn from recurring events across the recent history of Australia, of colonisation, nationalism, racism, fighting on foreign shores, land booms, industrial campaigns and culture wars? Arguments about the discipline of Australian History, from thinkers across the ideological and historical spectrum, are distilled in these extracts and essays.

The Knowledge Solution: Australian History is the second collection in a series that draws from the remarkable books published by Australia’s oldest university press.

262 pp, 2019

$ 40.00 $ 29.95

Book Reviews Reviews

There are no reviews yet.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Name *

Email *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Description

Additional information.

- Reviews (0)

Related products

THE ANZACS, RELIGION AND GOD – The Spiritual Journeys of Twenty-Seven Members of the AIF by Daniel Reynaud

The Ways of the Bushwalker on foot in Australia by Melissa Harper

Writing Histories by Ann Curthoys and Ann McGrath

Australia: a cultural history. By John Rickard

Shop All Categories

Sell Your Books via the History Victoria Bookshop

Visit or Contact Us

Recognition

Distinguished lecturer series, let's connect.

Subscribe to the RHSV newsletter

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Educational resources about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures

By ABC Education

- X (formerly Twitter)

Many wonderful organisations provide quality educational resources that can be used to learn about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures.

The following collection of websites and resources is not only valuable for teachers, students and schools, but also all Australians looking to better understand and celebrate Australia's First Peoples and rich Indigenous history.

1. Reconciliation Australia — What is Reconciliation?

Established in 2001, Reconciliation Australia inspires and enables relationships, respect and trust between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and non-Indigenous Australians, for the benefit of all Australians. They have many great resources, including a Reconciliation timeline; fact sheets about Sorry Day and the Mabo Decision ; and resources to help celebrate National Reconciliation Week , held annually from 27 May to 3 June.

Their Share our Pride website also provides a great starting point on a number of topics, such as identity , culture , intergenerational trauma , and family and kinship.

2. ABC Education — Classroom resources, mapped to the Australian Curriculum

Discover hundreds of free resources about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history and culture in this wonderful collection. Choose from videos, audio clips and footage from the ABC archives that relate to history, geography, science, English, technologies and the arts.

There are also engaging collections that teach students about topics, such as Aboriginal agriculture and technology ; place names ; and colonisation stories .

3. Behind The News — Indigenous culture

For more than fifty years, BTN has been broadcasting news for upper primary and lower secondary students, helping them understand issues and events outside their own lives. They have a fantastic collection of resources about Indigenous culture , including Indigenous recognition , the call for a treaty , the history of the Aboriginal flag , discrimination , the apology to Australia's Indigenous peoples , Aboriginal Anzacs and much more.

4. First Languages Australia — Maintain and revive Australia's first languages

First Languages Australia is working with language centres nationally to develop a map of languages that reflects the names and groupings favoured by community. Explore the Gambay map that showcases more that 780 languages, watch videos, listen to people sharing their languages and use the accompanying teachers' notes .

First Languages Australia has also worked with each of the states and territories to compile Nintrianganyi: National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Teaching and Employment Strategy and the companion document Global lessons: Indigenous languages and multilingualism in school programs . These resources are designed to help education departments, schools and local communities understand what's needed to sustain the provision of a local language curriculum.

5. NAIDOC — Celebrate history, culture and achievements

The National Aboriginal and Islander Day Observance Committee (NAIDOC) makes keys decisions about activities, such as NAIDOC Week. The NAIDOC teaching resources directly support teachers in addressing the Australian Curriculum's cross-curriculum priority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures. Check out their fabulous archive of posters dating back to 1972.

6. ABC TV documentaries aligned to the Curriculum

ABC Education has worked with reputable Indigenous institutions, such as Culture is Life, to align fantastic ABC documentaries to the Australian Curriculum. Documentaries include The Australian Dream , In My Blood It Runs , Archie Roach and Back to Nature .

The resources offer questions for students to answer and things for students to think about to direct their learning. Each resource also comes with a guide for teachers, which highlights cultural considerations when teaching these resources to a class.

7. Healing Foundation — Learn about the Stolen Generations

Developed with Stolen Generations members, teachers, parents and curriculum writers, the Healing Foundation resources aim to promote greater understanding about an often-overlooked part of Australia’s history in a safe and age-appropriate way. The resource kit includes professional learning tools for teachers, along with suggested lesson plans that have been mapped to the Australian Curriculum (Foundation to Year 9).

8. SBS Learn — Perspectives for NAIDOC Week and beyond

Working with the National NAIDOC Committee, SBS Learn has launched resources for NAIDOC Week. The resources are relevant to a broad range of learners and topics and provide Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives in classrooms beyond NAIDOC Week. The resources cover English, HASS, science, history, geography, the Arts and more.

9. Narragunnawali — Create a RAP for your school

Narragunnawali's online platform provides practical ways to introduce meaningful reconciliation initiatives in the classroom, around the school and with the community. Schools and early learning services can use the platform to develop a Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP), and teachers and educators can access professional learning and curriculum resources to support the implementation of reconciliation initiatives.

10. Reading Australia — Books about Indigenous themes

Reading Australia makes it easier for teachers to spread a love for Australian texts. They present many great books by Indigenous authors that celebrate Indigenous culture and history and raise awareness about the issues faced today by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Books are accompanied by teacher resources and essays.

11. Jarjums — Children's programming on National Indigenous Television (NITV)

Jarjums is the NITV programming dedicated to children. Catering to all kids — and kids at heart — they have fun educational Indigenous and First Nations content from Australia and around the world. It includes Little J & Big Cuz, which provides a young Indigenous audience with relatable characters and offers an insight into traditional Aboriginal culture, Country and language.

12. AIATSIS — Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

AIATSIS is a world-renowned research, collections and publishing organisation. They promote knowledge and understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, traditions, languages and stories, past and present. Use their subject guides to find materials relating to specific topics and check out their teachers’ notes and free resources .

13. Respect Relationships Reconciliation — Teacher education

The Respect Relationships Reconciliation (3Rs) study resources are designed to support teachers and educators in incorporating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander content in initial teacher education courses. There are three study modules: Know yourself (know your world), Know your students and Know what you teach. They also provide resources to help schools review existing units of study .

14. First Contact stories — Challenge preconceptions about Indigenous people

In SBS's First Contact series , Ray Martin takes a group of six well-known Australians with diverse, deeply intrenched preconceptions and opinions about our nation's Indigenous people on a journey into Aboriginal Australia. Take the discussion into the classroom with the First Contact classroom clips from the series and curriculum-linked activities (history, English and media arts for Years 9–12). There are also Teacher Notes you can download.

15. Guidance from Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL)

AITSL have great resources that help identify what teachers need to know and be able to do in order to teach Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students, and to teach all students about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages, history and culture. These resources have been developed to help Initial Teacher Education (ITE) providers and pre-service teachers understand how to meet initial teacher education and ongoing professional learning.

16. National Museum of Australia — Objects with stories

The National Museum of Australia has free curriculum-linked classroom resources to help bring the stories behind the objects in their collection to life, for students and teachers. Learn about the evidence of First Peoples , rock art , the boomerang , Pemulwuy , Mungo Lady and Uluru Statement from the Heart .

You can also watch the Australian Journey web series , which explores Australia's history through objects from the National Museum of Australia, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture and history. There's also a learning module on Rights and freedoms Defining Moments, 1945–present for year 10 classrooms.

17. Reconciliation Film Club — Documentaries to ignite conversation

Reconciliation Australia, NITV and SBS have proudly partnered to launch the Reconciliation Film Club , an online platform that helps you host screenings of a curated selection of Indigenous documentaries from Australia’s leading Indigenous filmmakers. The website has downloadable screening kits, discussion guides, and articles and ideas to support a successful event. Bring people together to develop a deeper understanding of Indigenous people’s perspectives and histories, ignite conversation and spark change.

18. Righting Wrongs — The 1967 referendum

On 27 May 1967, Australians voted in a referendum to change how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were referred to in the Constitution — a record 90.77 per cent of votes said YES to change the Constitution. Explore personal stories, opinions and historical recordings of what happened, what life was like for Indigenous people before the vote and how far we have come since 1967.

Find more classroom resources about Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures on ABC Education.

Reposted 3 May 2022. First published 8 July 2019.

Classroom resources about important Indigenous topics

Teach Aboriginal history and truths in the classroom

Classroom resources to help schools promote a broader understanding of the Stolen Generations

- QUT Library

- Library guides

- Library course and unit guides

- Course guide: Indigenous Education

Australian history

- Acknowledgement

- About this guide

- Indigenous cultures and lifeways

- Indigenous knowledges and perspectives

- Indigenous politics

- Contemporary Indigenous lives

- Best practice in Indigenous education

- Knowledge protocols

- Culturally-responsive pedagogy

- Community connections

- Critical reflection

- Indigenous language resources

- Resources for learning about Indigenous Australia

- Resources for learning through Indigenous perspectives

- Resources for Curriculum Teaching Areas

- Critical Indigenous Studies

- Indigenous Standpoint Theory and Indigenous Research

- Cultural frameworks for education

- Web Resources

These are texts that cover an aspect of Australian history, generally since 1788, with a specific focus on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander experiences.

- First Australians by Blackfella Films Publication Date: 2008 This series is useful for learning about the experiences of First Nations people through Australian history. This series was written and produced by Rachel Perkins, and Arrernte and Kalkadoon woman. The 7 episodes work through Australian history chronologically, from the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788 through to Native title, covering experiences across Australia. It brings together amazing images, photos, film and audio, as well as First Nations knowledge holders.

- Sydney: first encounters by ABC This podcast is useful for learning about the arrival of the First Fleet and the interactions between peoples that occurred. This podcast has been created by a non-Indigenous journalist – Keri Phillips – and features Indigenous and non-Indigenous historians.

- In the shadow of Terra Nullius by ABC This series of podcasts is useful for learning about Australian history that has impacted on First Nations people from 1901 to 2017. These podcasts are produced by a non-Indigenous presenter – Annabelle Quince – and feature the voices of many First Nations researchers, activists and identities. Together, the 4 podcasts explain the policies that were applied to First Nations people and the fight for recognition that took many forms since 1901.

- Stolen Generations’ Testimonies by Stolen Generations’ Testimonies Foundation This website is useful for learning about the personal impacts of being removed from your family as a First Nations child. This website contains many personal stories of members of the Stolen Generations who share their experiences. The experience of being removed impacts on people for their entire lives, and also impacts on their descendants. This is not a past event, but a continuing trauma.

- << Previous: Indigenous politics

- Next: Contemporary Indigenous lives >>

- Last Updated: Jan 3, 2024 11:40 AM

- URL: https://libguides.library.qut.edu.au/indigenous_education

Global links and information

- Current students

- Current staff

- TEQSA Provider ID: PRV12079 (Australian University)

- CRICOS No. 00213J

- ABN 83 791 724 622

- Accessibility

- Right to Information

Acknowledgement of Traditional Owners

QUT acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the lands where QUT now stands.

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, aboriginal knowledge, the history classroom and the australian university.

History of Education Review

ISSN : 0819-8691

Article publication date: 24 November 2021

Issue publication date: 22 November 2022

This article considers the impact of competing knowledge structures in teaching Australian Indigenous history to undergraduate university students and the possibilities of collaborative teaching in this space.

Design/methodology/approach

The authors, one Aboriginal and one non-Aboriginal, draw on a history of collaborative teaching that stretches over more than a decade, bringing together conceptual reflective work and empirical data from a 5-year project working with Australian university students in an introductory-level Aboriginal history subject.

It argues that teaching this subject area in ways which are culturally safe for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff and students, and which resist knowledge structures associated with colonial ways of conveying history, is not only about content but also about building learning spaces that encourage students to decolonise their relationships with Australian history.

Originality/value

This article considers collaborative approaches to knowledge transmission in the university history classroom as an act of decolonising knowledge spaces rather than as a model of reconciliation.

- Indigenous knowledge

- Ways of knowing

- Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories

- Teaching Indigenous history

- Collaborative knowledge transmission

Acknowledgements

This paper forms part of a special section “The history of knowledge and the history of education”, guest edited by Joel Barnes and Tamson Pietsch.

The authors would like to acknowledge that the student data collection discussed in this article began as part of an ACU Teaching and Development Grant, “Embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives in curriculum—for staff and students”. That project, mentored by Associate Professor Theda Thomas, had two strands, one based in the ACU National School of Education (led by Associate Professor Nerida Blair) and one based in the ACU National School of Arts (led by the authors). We would like to thank and acknowledge these women, and all of the other staff who participated in the project's workshop, for their contributions to the big picture thinking that prompted our longitudinal study.

Musgrove, N. and Wolfe, N. (2022), "Aboriginal knowledge, the history classroom and the Australian university", History of Education Review , Vol. 51 No. 2, pp. 123-136. https://doi.org/10.1108/HER-04-2021-0010

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

Australian History Quiz

History Hit

01 jan 2020.

From the Frontier Wars to the landings at Gallipoli – test your knowledge on Australian History.

If you enjoyed this quiz and would like to try some more, you can view our full set of quizzes here ., enjoy our range of australian history programmes.

Slide Anything shortcode error: A valid ID has not been provided

You May Also Like

Mac and Cheese in 1736? The Stories of Kensington Palace’s Servants

The Peasants’ Revolt: Rise of the Rebels

10 Myths About Winston Churchill

Medusa: What Was a Gorgon?

10 Facts About the Battle of Shrewsbury

5 of Our Top Podcasts About the Norman Conquest of 1066

How Did 3 People Seemingly Escape From Alcatraz?

5 of Our Top Documentaries About the Norman Conquest of 1066

1848: The Year of Revolutions

What Prompted the Boston Tea Party?

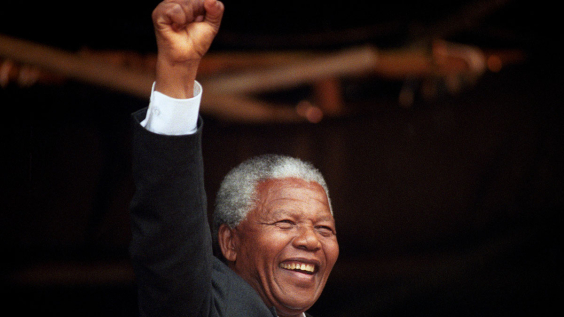

15 Quotes by Nelson Mandela

The History of Advent

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

The history of education in australia.

- Troy Heffernan Troy Heffernan La Trobe University - Melbourne Campus

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1459

- Published online: 26 May 2021

Education in Australia’s history stretches back tens of thousands of years, but only a small number of changes have altered its shape in that time. The first period of education lasted for thousands of years and was an Indigenous education as knowledge of religious beliefs, society, and laws was shared from one generation to the next. Knowledge of Australia’s significant environmental diversity was also taught because possessing the skills to find appropriate shelter for the conditions, while developing methods of hunting, gathering, and fishing, was knowledge that needed to be taught to ensure survival.

Education changed when Europeans invaded Indigenous lands. Settlers who brought children as well as those who gave birth to children wanted their offspring to be part of an education system that mimicked England’s. Ex-convicts and later members of the Church provided this service and began the tradition of non-Indigenous education in Australia. It was during the 19th century as cities and towns increased in size, and the population more generally, that the final two significant periods of Australian education began. The nation’s wealthiest required religious and grammar schools that prepared children for secondary education and for university overseas, as well as in Australia as universities were established and slowly increased in number. When private education began, it was largely the only option for those seeking university degrees for their children, but this began a series of events in Australia that still sees approximately one-third of all school students attending private schools.

Public and compulsory education began in the late 19th century and gradually became more accessible. Public education, in some respects, began as governments saw the benefit in the social advantages of education, and economic incentives in creating educated laborers. However, even through the austerity of world wars and financial depression, successive generations of publicly educated individuals saw the need for increasingly continuing education beyond the compulsory school age. Public education subsequently increased in popularity through the 20th century as a growing number of students stayed beyond compulsory schooling age. Education in Australia is still seeing policies change to make schooling accessible and open to all members of society regardless of background. In the 21st century, secondary schooling is being completed by most demographic groups, and university has become accessible to a diverse group of students, many of whom may not have had access to such options only a few decades ago. This is not to suggest that systemic issues of racism and ostracism have been eradicated, but steps have been made to begin addressing these issues.

- public education

- Catholic education

- grammar schools

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 28 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.154]

- 81.177.182.154

Character limit 500 /500

- F-10 curriculum

- General capabilities

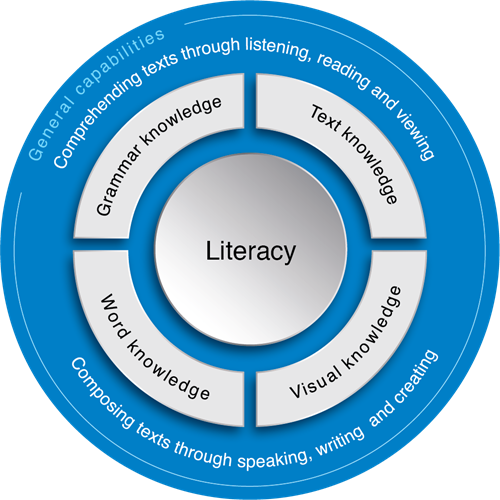

Literacy (Version 8.4)

In the Australian Curriculum, students become literate as they develop the knowledge, skills and dispositions to interpret and use language confidently for learning and communicating in and out of school and for participating effectively in society. Literacy involves students listening to, reading, viewing, speaking, writing and creating oral, print, visual and digital texts, and using and modifying language for different purposes in a range of contexts.

Literacy encompasses the knowledge and skills students need to access, understand, analyse and evaluate information, make meaning, express thoughts and emotions, present ideas and opinions, interact with others and participate in activities at school and in their lives beyond school. Success in any learning area depends on being able to use the significant, identifiable and distinctive literacy that is important for learning and representative of the content of that learning area.

Becoming literate is not simply about knowledge and skills. Certain behaviours and dispositions assist students to become effective learners who are confident and motivated to use their literacy skills broadly. Many of these behaviours and dispositions are also identified and supported in other general capabilities. They include students managing their own learning to be self-sufficient; working harmoniously with others; being open to ideas, opinions and texts from and about diverse cultures; returning to tasks to improve and enhance their work; and being prepared to question the meanings and assumptions in texts.

The key ideas for Literacy are organised into six interrelated elements in the learning continuum, as shown in the figure below.

Organising elements for Literacy

The Literacy continuum incorporates two overarching processes: Comprehending texts through listening, reading and viewing; and Composing texts through speaking, writing and creating.

The following areas of knowledge apply to both processes: Text knowledge; Grammar knowledge; Word knowledge and Visual knowledge.

Texts in the Literacy Continuum

Texts provide the means for communication. They can be written, spoken, visual, multimodal, and in print or digital/online forms. Multimodal texts combine language with other means of communication such as visual images, soundtrack or spoken words, as in film or computer presentation media. Texts include all forms of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC), for example gesture, signing, real objects, photographs, pictographs and braille. Texts provide important opportunities for learning about aspects of human experience and about aesthetic value. Many of the tasks that students undertake in and out of school involve understanding and producing imaginative, informative and persuasive texts, media texts, everyday texts and workplace texts.

The usefulness of distinctions among types of texts relates largely to how clearly at each year level these distinctions can guide the selection of materials for students to listen to, read, view, write and create, and the kinds of purposeful activities that can be organised around these materials. Although many types of texts will be easy to recognise on the basis of their subject matter, forms and structures, the distinctions between types of texts need not be sharp or formulaic. The act of creating texts, by its nature, involves experimentation and adaptation of language and textual elements from many different writing styles and categories of texts. As a result, It is not unusual for an imaginative text to have strong persuasive elements, or for a persuasive text to contain features more typically seen in informative texts, such as subheadings or bullet points.

Comprehending texts through listening, reading and viewing

This element is about receptive language and involves students using skills and strategies to access and interpret spoken, written, visual and multimodal texts.

Students navigate, read and view texts using applied topic knowledge, vocabulary, word and visual knowledge. They listen and respond to spoken audio and multimodal texts, including listening for information, listening to carry out tasks and listening as part of participating in classroom activities and discussions. Students use a range of strategies to comprehend, interpret and analyse these texts, including retrieving and organising literal information, making and supporting inferences and evaluating information and points of view. In developing and acting with literacy, students:

- navigate, read and view learning area texts

- listen and respond to learning area texts

- interpret and analyse learning area texts.

The element of Comprehending texts can apply to students at any point in their schooling. The beginning of the learning sequence for this element has been extended by four extra levels (Levels 1a to 1d) to describe in particular the early development of communication skills. The descriptions for Comprehending texts at these levels apply across the elements of Text knowledge, Grammar knowledge, Word knowledge and Visual knowledge.

Composing texts through speaking, writing and creating

This element is about expressive language and involves students composing different types of texts for a range of purposes as an integral part of learning in all curriculum areas.

These texts include spoken, written, visual and multimodal texts that explore, communicate and analyse information, ideas and issues in the learning areas. Students create formal and informal texts as part of classroom learning experiences including group and class discussions, talk that explores and investigates learning area topics, and formal and informal presentations and debates. In developing and acting with literacy, students:

- compose spoken, written, visual and multimodal learning area texts

- use language to interact with others

- deliver presentations.

The element of Composing texts can apply to students at any point in their schooling. The beginning of the learning sequence for this element has been extended by four extra levels (Levels 1a to 1d) to describe in particular the development of communication skills. The descriptions for Composing texts at these levels apply across the elements of Text knowledge, Grammar knowledge, Word knowledge and Visual knowledge.

The following areas of knowledge apply to both processes.

Text knowledge

This element involves students understanding how the spoken, written, visual and multimodal texts they compose and comprehend are structured to meet the range of purposes needed in the learning areas.

Students understand the different types of text structures that are used within learning areas to present information, explain processes and relationships, argue and support points of view and investigate issues. They develop understanding of how whole texts are made cohesive through various grammatical features that link and strengthen the text’s internal structure. In developing and acting with literacy, students:

- use knowledge of text structures

- use knowledge of text cohesion.

Grammar knowledge

This element involves students understanding the role of grammatical features in the construction of meaning in the texts they compose and comprehend.

Students understand how different types of sentence structures present, link and elaborate ideas, and how different types of words and word groups convey information and represent ideas in the learning areas. They gain understanding of the grammatical features through which opinion, evaluation, point of view and bias are constructed in texts. In developing and acting with literacy, students:

- use knowledge of sentence structures

- use knowledge of words and word groups

- express opinion and point of view.

Word Knowledge

This element involves students understanding the increasingly specialised vocabulary and spelling needed to compose and comprehend learning area texts.

Students develop strategies and skills for acquiring a wide topic vocabulary in the learning areas and the capacity to spell the relevant words accurately. In developing and acting with literacy, students:

- understand learning area vocabulary

- use spelling knowledge.

Visual Knowledge

This element involves students understanding how visual information contributes to the meanings created in learning area texts.

Students interpret still and moving images, graphs, tables, maps and other graphic representations, and understand and evaluate how images and language work together in distinctive ways in different curriculum areas to present ideas and information in the texts they compose and comprehend. In developing and acting with literacy, students:

- understand how visual elements create meaning.

Literacy in the learning areas

Literacy presents those aspects of the Language and Literacy strands of the Australian Curriculum: English that should also be applied in all other learning areas. Students learn literacy knowledge and skills as they engage with these strands of English. Literacy is not a separate component of the Australian Curriculum and does not contain new content.

While much of the explicit teaching of literacy occurs in the English learning area, literacy is strengthened, made specific and extended in other learning areas as students engage in a range of learning activities with significant literacy demands. Paying attention to the literacy demands of each learning area ensures that students’ literacy development is strengthened so that it supports subject-based learning. This means that:

- all teachers are responsible for teaching the subject-specific literacy of their learning area/s

- all teachers need a clear understanding of the literacy demands and opportunities of their learning area/s

- literacy appropriate to each learning area is embedded in the content descriptions and elaborations of the learning area and is identified using the literacy icon.

The learning area or subject with the highest proportion of content descriptions tagged with Literacy is placed first in the list.

The Australian Curriculum: English has a central role in the development of literacy in a manner that is more explicit and foregrounded than is the case in other learning areas.

Literacy is developed through the specific study of the English language in all its spoken, written and visual forms, enabling students to become confident readers and meaning-makers as they learn about the creative and communicative potential of a wide range of subject-specific and everyday texts from across the curriculum. Students understand how the language in use is determined by the many different social contexts and specific purposes for reading and viewing, speaking and listening, writing and creating. Through critically interpreting information and evaluating the way it is organised in different types of texts, for example, the role of subheadings, visuals and opening statements, students learn to make increasingly sophisticated language choices in their own texts. The English learning area has a direct role in the development of language and literacy skills. It seeks to empower students in a manner that is more explicit than is the case in other learning areas. Students learn about language and how it works in the Language strand, and gradually develop and apply this knowledge to the practical skills of the Literacy strand in English, where students systematically and concurrently apply phonic, contextual, semantic and grammatical knowledge within their growing literacy capability to interpret and create spoken, print, visual and multimodal texts with appropriateness, accuracy and clarity.

Learning in the Australian Curriculum: Languages develops overall literacy. It is in this sense ‘value added’, strengthening literacy-related capabilities that are transferable across languages, both the language being learnt and all other languages that are part of the learner’s repertoire. Languages learning also strengthens literacy-related capabilities across domains of use, such as the academic domain and the domains of home language use, and across learning areas.

Literacy development involves conscious attention and focused learning. It involves skills and knowledge that need guidance, time and support to develop. These skills include the ability to decode and encode from sound and written systems, the learning of grammatical, orthographic and textual conventions, and the development of semantic, pragmatic and interpretive, critical and reflective literacy skills.

Literacy development for second language learners is cognitively demanding. It involves these same elements but often without the powerful support of a surrounding oral culture and context. The strangeness of the additional language requires scaffolding. In the language classroom, analysis is prioritised alongside experience. Explicit, explanatory and exploratory talk around language and literacy is a core element. Learners are supported to develop their own meta–awareness, to be able to think and talk about how the language works and about how they learn to use it. Similarly, for first language learners, literacy development that extends to additional domains and contexts of use requires comparative analysis that extends literacy development in their first language and English.

F-6/7 Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS)

In the F–6/7 Australian Curriculum: Humanities and Social Sciences, students develop literacy capability as they learn how to build discipline-specific knowledge about history, geography, civics and citizenship, and economics and business. Students use a wide range of informative, persuasive and imaginative texts in multiple modes to pose questions, research, analyse, evaluate and communicate information, concepts and ideas.

Students progressively learn to use stories, narratives, recounts, reports, lists, explanations, arguments, illustrations, timelines, maps, tables, graphs, spreadsheets, photographs, images including remotely sensed and satellite images, and realia – to examine, interpret and communicate data, information, ideas, points of view, perspectives and conclusions.

They learn to use language features and text structures to comprehend and compose cohesive texts about the past, present and future, including: discipline-specific vocabulary; appropriate tense verbs for recounting events and processes; complex sentences to establish sequential, cause-and-effect and comparative relationships; features and structures of persuasive texts; wide use of adverbs that describe places, people, events, processes, systems and perspectives; and extended noun groups using descriptive adjectives.

Students learn to make increasingly sophisticated language and text choices, understanding that language varies according to context and purpose and using language flexibly. Their texts are often accompanied by graphics that provide significant information and are supported by references and quotations, and they understand geography’s scientific and expressive modes of writing.

As students participate in inquiry, they learn to ask distinctively discipline-specific questions and to apply participatory knowledge in discussions and debates. They learn to evaluate texts for shades of meaning, feeling and opinion, and develop considered points of view, communicating conclusions and preferred futures to a range of audiences.

7-10 History

In the Australian Curriculum: History, students develop literacy capability as they learn how to build historical knowledge and to explore, analyse, question, discuss and communicate historical information, concepts and ideas. In history, students progressively learn to use a wide range of informative, persuasive and imaginative texts in multiple modes. These texts – which include stories, narratives, recounts, reports, lists, explanations, arguments, illustrations, timelines, maps, tables, graphs, photographs and images, and realia – are often supported by references and quotations from primary and secondary sources.

Students learn to make increasingly sophisticated language and text choices, understanding that language varies according to context, and they develop their ability to use language flexibly. They learn to use language features and text structures to comprehend and compose cohesive texts about the past, present and future, including: topic-specific vocabulary; appropriate tense verbs for recounting events and processes; complex sentences to establish sequential, cause-and-effect and comparative relationships; features and structures of persuasive texts; wide use of adverbs that describe people, places, events and perspectives and extended noun groups using descriptive adjectives.

7-10 Geography

In the Australian Curriculum: Geography, students develop literacy capability as they learn how to build geographical knowledge and understanding and how to explore, discuss, analyse and communicate geographical information, concepts and ideas. They use a wide range of informative and literary texts, for example, interviews, reports, stories, photographs and maps, to help them understand the places that make up our world, learning to evaluate these texts and recognising how language and images can be used to make and manipulate meaning.

Students develop oral and written skills, making increasingly sophisticated language and text choices. They understand that language varies according to context and they develop their ability to use language flexibly. They use language to ask distinctively geographical questions. They plan a geographical inquiry, collect and evaluate information, communicate their findings, reflect on the conduct of their inquiry and respond to what they have learnt. Students progressively learn to use geography’s scientific and expressive modes of writing and the vocabulary of the discipline, including complex sentences to establish sequential, cause-and-effect and comparative relationships and wide use of adverbs and adjectives that describe places, people, events, processes, systems and perspectives. They learn to comprehend and compose graphical and visual texts through working with maps, diagrams, photographs and remotely sensed and satellite images.

7-10 Civics and Citizenship

In the Australian Curriculum: Civics and Citizenship, students develop literacy capability as they research, read and analyse sources of information on aspects of Australia’s political and legal systems and contemporary civics and citizenship issues. They learn to understand and use language to discuss and communicate information, concepts and ideas related to their studies. They learn to evaluate texts for shades of meaning, feeling and opinion, learning to distinguish between fact and opinion and how language and images can be used to manipulate meaning on political and social issues. Communication is critical in Civics and Citizenship, in particular for articulating, debating and evaluating ideas, points of view and preferred futures and participating in group discussions.

7-10 Economics and Business

In the Australian Curriculum: Economics and Business, students learn to examine and interpret a variety of economics and business data and/or information. They learn to use effectively the specialised language and terminology of economics and business when applying concepts to contemporary issues and events, and communicating conclusions to a range of audiences through a range of multimodal approaches. They learn to use language features and text structures to comprehend and compose cohesive texts involving economics and business issues and events, including: discipline-specific vocabulary; appropriate tense verbs for describing events and processes; complex sentences to establish sequential, cause-and-effect and comparative relationships; and wide use of adverbs and adjectives that describe events, processes, systems and perspectives. Students learn to evaluate texts for shades of meaning and opinion, participating in debates and discussions, developing a considered point of view when communicating conclusions and preferred futures to a range of audiences.

In the Australian Curriculum: The Arts, students use literacy to develop, apply and communicate their knowledge and skills as artists and as audiences. Through making and responding, students enhance and extend their literacy skills as they create, compose, design, analyse, comprehend, discuss, interpret and evaluate their own and others’ artworks.

Each Arts subject requires students to learn and use specific terminology of increasing complexity as they move through the curriculum. Students understand that the terminologies of The Arts vary according to context and they develop their ability to use language dynamically and flexibly.

Technologies

In the Australian Curriculum: Technologies, students develop literacy as they learn how to communicate ideas, concepts and detailed proposals to a variety of audiences; read and interpret detailed written instructions for specific technologies, often including diagrams and procedural writings such as software user manuals, design briefs, patterns and recipes; prepare accurate, annotated engineering drawings, software instructions and coding; write project outlines, briefs, concept and project management proposals, evaluations, engineering, life cycle and project analysis reports; and prepare detailed specifications for production.

By learning the literacy of technologies, students understand that language varies according to context and they increase their ability to use language flexibly. Technologies vocabulary is often technical and includes specific terms for concepts, processes and production. Students learn to understand that much technological information is presented in the form of drawings, diagrams, flow charts, models, tables and graphs. They also learn the importance of listening, talking and discussing in technologies processes, especially in articulating, questioning and evaluating ideas.

Health and Physical Education

The Australian Curriculum: Health and Physical Education assists in the development of literacy by introducing specific terminology used in health and physical activity contexts. Students understand the language used to communicate and connect respectfully with other people, describe their own health status, as well as products, information and services. They also develop skills that empower them to be critical consumers able to access, interpret, analyse, challenge and evaluate the ever-expanding and changing knowledge base and influences in the fields of health and physical education. In physical activity settings, as consumers, performers and spectators, students develop an understanding of the language of movement and movement sciences. This is essential in analysing their own and others’ movement and levels of fitness.

Students also learn to comprehend and compose texts related to the Australian Curriculum: Health and Physical Education. This includes learning to communicate effectively for a variety of purposes to different audiences, express their own ideas and opinions, evaluate the viewpoints of others, ask for help and express their emotions appropriately in a range of social and physical activity contexts.

Mathematics

In the Australian Curriculum: Mathematics, students learn the vocabulary associated with number, space, measurement and mathematical concepts and processes. This vocabulary includes synonyms, technical terminology, passive voice and common words with specific meanings in a mathematical context. Students develop the ability to create and interpret a range of texts typical of mathematics ranging from calendars and maps to complex data displays. Students use literacy to understand and interpret word problems and instructions that contain the particular language features of mathematics. They use literacy to pose and answer questions, engage in mathematical problem-solving, and to discuss, produce and explain solutions.

In the Australian Curriculum: Science, students develop a broader literacy capability as they explore and investigate their world. They are required to comprehend and compose texts including those that provide information, describe events and phenomena, recount experiments, present and evaluate data, give explanations and present opinions or claims. They will also need to comprehend and compose multimedia texts such as charts, graphs, diagrams, pictures, maps, animations, models and visual media. Language structures are used to link information and ideas, give descriptions and explanations, formulate hypotheses and construct evidence-based arguments capable of expressing an informed position.

By learning the literacy of science, students understand that language varies according to context and they increase their ability to use language flexibly. Scientific vocabulary is often technical and includes specific terms for concepts and features of the world, as well as terms that encapsulate an entire process in a single word, such as ‘photosynthesis’. Language is therefore essential in providing the link between the concept itself and student understanding and for assessing whether the student has understood the concept.

Work Studies

In the Australian Curriculum: Work Studies, Years 9–10, students develop literacy capability as they adopt an appreciation of the skills of listening, speaking, reading, writing and interacting with others. They are given opportunities to locate and evaluate information, express ideas, thoughts and emotions, justify opinions, interact effectively with others, debrief and reflect and participate in a range of communication activities to support the development of literacy skills.

The development of critical workplace-related literacy skills is essential for students to become effective workforce participants who can access, interpret, analyse, challenge and evaluate the knowledge and skills required in a constantly growing and changing world of work.

PDF documents

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

- Buy Tickets

- Join & Give

Indigenous Australians: Australia’s First Peoples exhibition 1996-2015

- Updated 04/06/21

- Share this page:

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Linkedin

- Share via Email

- Print this page

The exhibition had five core themes explored through multimedia, art, cultural material and collection objects.

These extended family relationships are the core of Indigenous kinship systems that are central to the way culture is passed on and society is organised.

"All people with the same skin grouping as my mother are my mothers... They have the right, the same as my mother, to watch over me, to control what I'm doing, to make sure that I do the right thing. It's an extended family thing... It's a wonderful secure system." Wadjularbinna Doomadgee, Gungalidda leader, Gulf of Carpentaria, 1996

Kinship systems define where a person fits in to the community, binding people together in relationships of sharing and obligation. These systems may vary across communities but they serve similar functions across Australia. Kinship defines roles and responsibilities for raising and educating children and structures systems of moral and financial support within the community.

Learn about Indigenous family relationships

Elders bridge the past and the present and provide guidance for the future. They teach important traditions and pass on their skills, knowledge and personal experiences. It is for these reasons that in Indigenous societies elders are treated with respect.

Family Ties

In Aboriginal Society the family unit is very large and extended, often with ties to the community... Having that family unit broken down has just opened the floodgates for a lot of problems, a lot of emotional problems, mental and physical turmoil. If you want to use a really hard term to describe the impact that removal of Aboriginal children has had on Aboriginal families,'attempted cultural genocide' is a good phrase. Carol Kendal in 'Indigenous People and the Law' , C. Cunneen & T. Libesman (eds) Reed international Books, 1995

Indigenous communities have strong family values that are rarely endorsed or understood by government authorities. Children are not just the concern of the biological parents, but the entire community. Therefore, the raising, care, education and discipline of children are the responsibility of everyone - male, female, young and old.

Indigenous education stresses the relationship between the child and its social and natural environment, which children learn by close observation and practice. However, some knowledges are secret and are revealed only when the child is ready.

The government policies in which families and communities were separated were more than just heartbreaking for the individuals involved - they also effectively halted the passing of cultural knowledge from one generation to another.

Passing the Culture to Children - Storytelling

In Aboriginal Australian society storytelling makes up a large part of everyday life. Storytelling is not only about entertaining people but is also vital in educating children about life.

Storytelling is used in a variety of ways. It is used to teach children how they should behave and why, and to pass on knowledge about everyday life such as how and when to find certain foods. Stories are also used to explain peoples' spirituality, heritage and the laws. Dreaming stories pass on information to young people about creation, how the land was formed and populated, creation of plants, animals and humans, information about ancestral beings and places, the boundaries of peoples' tribal lands, how ancestors came to Australia, how people migrated across the country and arrived in a particular part of the country.

However, not all information can be known by all people. Some information can only be revealed to certain people. This information is known as sacred. For example, some sacred information can only be told to certain initiated women or men after they have carried out certain initiation rites.

The elders use every opportunity to educate the children about the way of life of their people. Stories are told while walking down to the waterhole or grinding up seeds to make damper (bread) or sitting around the campfire at night. As children grew older more information is passed on about their culture. Once a person becomes an adult they are responsible for passing on the information they had learned to the younger people.

Storytelling ensures that Aboriginal heritage is passed on to the younger people. This is how Dreaming stories have been passed down for thousands of years and continue to be passed on today.

Storytelling today

Today storytelling in Indigenous Australia is still a very important way of passing on information to people. For thousands of years information has been passed on through stories and songs. Today you can also see and hear it in many types of music, plays, poetry, books, artwork, on television and on the Web and you can now read in books the traditional stories that were once only spoken.

These stories keep alive the traditions and heritage of Indigenous Australia not only within Indigenous communities but also within the wider community. This helps to increase understanding and awareness between people.

Today, as well as elders in the communities, we have professional story tellers who visit schools and other educational groups passing on their knowledge about Indigenous culture and beliefs.

Indigenous children across Australia often make their own toys, and like children everywhere, they are incredibly resourceful. Some toys are models of traditional tools and weapons, such as boomerangs, spears, baskets or boats, while others are model airplanes, torches or telephones. Some toys are created specifically for Indigenous games. Special throwing objects called weet weets were used in boys' throwing game in northern Queensland. This selection of toys is just a sample of the range found across the country.

String games are common in both Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultures around the world. String figure designs often resembled objects that were, and in some parts of Australian still are, used in everyday life such as dilly bags and baskets, or they represented animals and people, or abstract ideas such as the forces of nature. As people played the string game designs would change quickly from one thing to another. This game was also used to help tell stories.

The stolen generation

They just came down and say, "We taking these kids". They just take you out if your mothers arms. That's what they done to me. I was still at my mother's breast when they took me. Alec Kruger, 1995

The greatest assault on Indigenous cultures and family life was the forced separation or 'taking away' of Indigenous children from their families. This occurred in every Australian state form the late 1800s until the practice was officially ended in 1969. During this time as many as 100 000 children were separated from their families. These children became known as the Stolen Generation.

The separation of children from their families placed into Indigenous children into government-run institutions; adoption of children by white families; and the fostering of children into white families. The last two strategies were particularly applied to 'fair-skinned' children.

These forced separations were part of deliberate policies of assimilation. Their aim was to cut children off from their culture to have them raised to think and act as 'white'.

What is Link Up?

Well there was nine of us in the family, old (Lambert) came along and said: "You can't look after these kids by yourself Mrs Clayton", but we were for months without welfare coming near us. We had the two grandmothers and all our uncles and aunties there and our father's brothers were there. We weren't short of an extended family by any means. We never went without anything. But they still took us away. What right did they have? I am still seeking answers to [my] family's removal. Iris Clayton, Wiradjuri Elder, Leeton/Canberra in 'Link-Up' Booklet 1995

Link-Up was formed in 1980 to work with Aboriginal adults who were separated as children from families. They may have been raised in state or sectarian institiutions specifically for Aboriginal children or in non-Aboriginal institutions, foster homes or adoptive homes.

Most of the children separated from their families grew up knowing little about their Aboriginal names, families, culture and heritage. These circumstances made it very difficult for those who wanted to find their families.

According to Link-Up, "empowerment is the basis of our work. Empowerment means that as workers we acknowledge the person's experience and we respect their ability to make decisions about their needs and their healing process. They are the experts of their own experience". Link-Up provides support and counselling before, during and after the reunion of families. Since its beginning Link-Up has worked with thousands of Aboriginal families.

Government Institutions for Children

Kinchela is a 13 hectare area of fertile land at the mouth of the Macleay River on the mid-north coast of New South Wales. In 1924, the Aboriginal Protection Board opened the Kinchela Boys Home with the 'official' purpose of providing training for Aboriginal boys between the ages of five and fifteen. These boys were taken from their families by the State from all over New South Wales.

Conditions at Kinchela were harsh. The boys received a poor education from unqualified teachers and worked long hours on vegetable and dairy farms run by the Board on the reserve land. Boys were beaten, tied up, given little emotional support, and no attention was given to developing skills of individual boys.

At the age of fifteen, the boys were sent to work as rural labourers. The board kept control of most of their earnings, which were supposed to be kept in trust for them until they reached adulthood. Most never saw their trust money.

Conditions improved in 1940, when the Protection Board was abolished and replaced by the Aboriginal Welfare Board. From the 1950s boys were sent to high school in Kempsey where they won many local athletics and sporting championships. Despite improvements, the fact remains that Kinchela was a home for 'stolen children'.

Kinchela closed down in 1969, when the Aboriginal Welfare Board was finally disbanded.

Cootamundra Girls Home

Cootamundra Girls Home, established in 1911, was the first of the homes for Aboriginal children set up by the Aborigines Protection Board. The main aim of the Board was to 'rescue' Aboriginal children from their families and assimilate them into the white community. Girls were the main target of the Board, especially so-called 'half-caste' or 'mixed blood' girls. The girls were trained as domestic servants and sent out to work for middle class white families.

At Cootamundra, Aboriginal girls were instructed to 'think white, look white, act white'. This was part of the process to make the girls suitable wives for white men, in the hope that through interracial marriages, Aboriginal blood would be 'bred out'. They were taught to look down on their own people and to fear Aboriginal men.

Girls in the home were not allowed to communicate with their families. They were often told that their parents were dead and even given forged death certificates. As a result, many of the girls in the home lost their families forever.

Cootamundra Home was closed in 1968, the year before the Aboriginal Welfare Board (previously the Aborigines Protection Board) was abolished.

Social Justice

These rights have been difficult to achieve for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders because of a history of governmental and colonial racism.

Social justice is what faces you in the morning. It is awakening in a house with adequate water supply, cooking facilities and sanitation. It is the ability to nourish your children and send them to school where their education not only equips them for employment but reinforces their knowledge and understanding of their cultural inheritance. It is the prospect of genuine employment and good health: a life of choices and opportunity, free from discrimination. Mick Dodson, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Sydney Morning Herald, 25 January, 1997

What is social justice?

Non-Aboriginal Australia has developed on the racist assumption of an ingrained sense of superiority that it knows best what is good for Aboriginal people. Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, National Report

Redfern Park Speech

[I]t might help if we non-Aboriginal Australians imagined ourselves dispossessed of the land we lived on for 50 000 years, and then imagined ourselves told that it had never been ours. Imagine if ours was the oldest culture in the world and we were told that it was worthless. Imagine if we had resisted this settlement, suffered and died in the defence of our land, and then were told in history books that we had given it up without a fight. Imagine if non-Aboriginal Australians had served their country in peace and war and were then ignored in history books. Imagine if our feats on the sporting field has inspired admiration and patriotism and yet did nothing to diminish prejudice. Imagine if our spiritual life was denied and ridiculed. Imagine if we had suffered the injustice and then were blamed for it. Extract from the speech by Mr Paul Keating, Prime Minister of Australia, Redfern Park, 10 December 1993 at the launch of Australia's celebration of the International Year of the World's Indigenous People.

Social Justice - keeping score

The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody found a long history of social injustice in a number of crucial areas for Indigenous Australians. The following statistics measure progress in achieving social justice for Indigenous Australians in these areas.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations comprise just over 1.6% of the total Australian population.

Two thirds of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders live in rural or remote areas. However, more Indigenous people live in Western Sydney than anywhere else in Australia.

Indigenous Australians are ten times more likely to suffer from diabetes mellitus than non-Indigenous Australians. Indigenous Australians are seven times more likely to die of a respiratory disease.

The rate of Indigenous infant mortality is two to three times greater than for non-Indigenous Australians.

The life expectancy for Indigenous Australians is between 16-18 years less than non-Indigenous Australians.

In 1991, the unemployment rate for Indigenous Australians was nearly three times that of the national average.

Employment rate in 1991:

- Indigenous Australian 30.8 %

- National 11.7 %

Indigenous Australians earn less than two thirds the national average.

Average income per year in 1991:

- Indigenous Australian $11 491

- National $17 614

For more detailed statistics go to the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission website.

Over 30 percent of Indigenous Australian family dwellings are 'over-occupied', by national standards. The national average is eight percent.

27 percent of Indigenous Australians own their own homes. The national rate for home ownership is 69 percent.

Law and Justice

At 30 June, 2016:

- There were 10,596 prisoners who identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, a 7% increase (711 prisoners) from 30 June, 2015 (9,885 prisoners). The number of non-Indigenous prisoners increased by 8% (2,002 prisoners).

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners accounted for just over a quarter (27%) of the total Australian prisoner population.

- From 30 June, 2015, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander imprisonment rate increased by 4%, from 2,253 to 2,346 prisoners per 100,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population. The non-Indigenous rate increased by 6% over the same period from 146 to 154 prisoners per 100,000 non-Indigenous population.

- The proportion of adult prisoners who identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ranged from 8% in Victoria (535 prisoners) to 84% (1,393 prisoners) in the Northern Territory.

(Australian Bureau of Statistics)