- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- The Research Problem/Question

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A research problem is a definite or clear expression [statement] about an area of concern, a condition to be improved upon, a difficulty to be eliminated, or a troubling question that exists in scholarly literature, in theory, or within existing practice that points to a need for meaningful understanding and deliberate investigation. A research problem does not state how to do something, offer a vague or broad proposition, or present a value question. In the social and behavioral sciences, studies are most often framed around examining a problem that needs to be understood and resolved in order to improve society and the human condition.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Guba, Egon G., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. “Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 105-117; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

Importance of...

The purpose of a problem statement is to:

- Introduce the reader to the importance of the topic being studied . The reader is oriented to the significance of the study.

- Anchors the research questions, hypotheses, or assumptions to follow . It offers a concise statement about the purpose of your paper.

- Place the topic into a particular context that defines the parameters of what is to be investigated.

- Provide the framework for reporting the results and indicates what is probably necessary to conduct the study and explain how the findings will present this information.

In the social sciences, the research problem establishes the means by which you must answer the "So What?" question. This declarative question refers to a research problem surviving the relevancy test [the quality of a measurement procedure that provides repeatability and accuracy]. Note that answering the "So What?" question requires a commitment on your part to not only show that you have reviewed the literature, but that you have thoroughly considered the significance of the research problem and its implications applied to creating new knowledge and understanding or informing practice.

To survive the "So What" question, problem statements should possess the following attributes:

- Clarity and precision [a well-written statement does not make sweeping generalizations and irresponsible pronouncements; it also does include unspecific determinates like "very" or "giant"],

- Demonstrate a researchable topic or issue [i.e., feasibility of conducting the study is based upon access to information that can be effectively acquired, gathered, interpreted, synthesized, and understood],

- Identification of what would be studied, while avoiding the use of value-laden words and terms,

- Identification of an overarching question or small set of questions accompanied by key factors or variables,

- Identification of key concepts and terms,

- Articulation of the study's conceptual boundaries or parameters or limitations,

- Some generalizability in regards to applicability and bringing results into general use,

- Conveyance of the study's importance, benefits, and justification [i.e., regardless of the type of research, it is important to demonstrate that the research is not trivial],

- Does not have unnecessary jargon or overly complex sentence constructions; and,

- Conveyance of more than the mere gathering of descriptive data providing only a snapshot of the issue or phenomenon under investigation.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Brown, Perry J., Allen Dyer, and Ross S. Whaley. "Recreation Research—So What?" Journal of Leisure Research 5 (1973): 16-24; Castellanos, Susie. Critical Writing and Thinking. The Writing Center. Dean of the College. Brown University; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Selwyn, Neil. "‘So What?’…A Question that Every Journal Article Needs to Answer." Learning, Media, and Technology 39 (2014): 1-5; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types and Content

There are four general conceptualizations of a research problem in the social sciences:

- Casuist Research Problem -- this type of problem relates to the determination of right and wrong in questions of conduct or conscience by analyzing moral dilemmas through the application of general rules and the careful distinction of special cases.

- Difference Research Problem -- typically asks the question, “Is there a difference between two or more groups or treatments?” This type of problem statement is used when the researcher compares or contrasts two or more phenomena. This a common approach to defining a problem in the clinical social sciences or behavioral sciences.

- Descriptive Research Problem -- typically asks the question, "what is...?" with the underlying purpose to describe the significance of a situation, state, or existence of a specific phenomenon. This problem is often associated with revealing hidden or understudied issues.

- Relational Research Problem -- suggests a relationship of some sort between two or more variables to be investigated. The underlying purpose is to investigate specific qualities or characteristics that may be connected in some way.

A problem statement in the social sciences should contain :

- A lead-in that helps ensure the reader will maintain interest over the study,

- A declaration of originality [e.g., mentioning a knowledge void or a lack of clarity about a topic that will be revealed in the literature review of prior research],

- An indication of the central focus of the study [establishing the boundaries of analysis], and

- An explanation of the study's significance or the benefits to be derived from investigating the research problem.

NOTE : A statement describing the research problem of your paper should not be viewed as a thesis statement that you may be familiar with from high school. Given the content listed above, a description of the research problem is usually a short paragraph in length.

II. Sources of Problems for Investigation

The identification of a problem to study can be challenging, not because there's a lack of issues that could be investigated, but due to the challenge of formulating an academically relevant and researchable problem which is unique and does not simply duplicate the work of others. To facilitate how you might select a problem from which to build a research study, consider these sources of inspiration:

Deductions from Theory This relates to deductions made from social philosophy or generalizations embodied in life and in society that the researcher is familiar with. These deductions from human behavior are then placed within an empirical frame of reference through research. From a theory, the researcher can formulate a research problem or hypothesis stating the expected findings in certain empirical situations. The research asks the question: “What relationship between variables will be observed if theory aptly summarizes the state of affairs?” One can then design and carry out a systematic investigation to assess whether empirical data confirm or reject the hypothesis, and hence, the theory.

Interdisciplinary Perspectives Identifying a problem that forms the basis for a research study can come from academic movements and scholarship originating in disciplines outside of your primary area of study. This can be an intellectually stimulating exercise. A review of pertinent literature should include examining research from related disciplines that can reveal new avenues of exploration and analysis. An interdisciplinary approach to selecting a research problem offers an opportunity to construct a more comprehensive understanding of a very complex issue that any single discipline may be able to provide.

Interviewing Practitioners The identification of research problems about particular topics can arise from formal interviews or informal discussions with practitioners who provide insight into new directions for future research and how to make research findings more relevant to practice. Discussions with experts in the field, such as, teachers, social workers, health care providers, lawyers, business leaders, etc., offers the chance to identify practical, “real world” problems that may be understudied or ignored within academic circles. This approach also provides some practical knowledge which may help in the process of designing and conducting your study.

Personal Experience Don't undervalue your everyday experiences or encounters as worthwhile problems for investigation. Think critically about your own experiences and/or frustrations with an issue facing society or related to your community, your neighborhood, your family, or your personal life. This can be derived, for example, from deliberate observations of certain relationships for which there is no clear explanation or witnessing an event that appears harmful to a person or group or that is out of the ordinary.

Relevant Literature The selection of a research problem can be derived from a thorough review of pertinent research associated with your overall area of interest. This may reveal where gaps exist in understanding a topic or where an issue has been understudied. Research may be conducted to: 1) fill such gaps in knowledge; 2) evaluate if the methodologies employed in prior studies can be adapted to solve other problems; or, 3) determine if a similar study could be conducted in a different subject area or applied in a different context or to different study sample [i.e., different setting or different group of people]. Also, authors frequently conclude their studies by noting implications for further research; read the conclusion of pertinent studies because statements about further research can be a valuable source for identifying new problems to investigate. The fact that a researcher has identified a topic worthy of further exploration validates the fact it is worth pursuing.

III. What Makes a Good Research Statement?

A good problem statement begins by introducing the broad area in which your research is centered, gradually leading the reader to the more specific issues you are investigating. The statement need not be lengthy, but a good research problem should incorporate the following features:

1. Compelling Topic The problem chosen should be one that motivates you to address it but simple curiosity is not a good enough reason to pursue a research study because this does not indicate significance. The problem that you choose to explore must be important to you, but it must also be viewed as important by your readers and to a the larger academic and/or social community that could be impacted by the results of your study. 2. Supports Multiple Perspectives The problem must be phrased in a way that avoids dichotomies and instead supports the generation and exploration of multiple perspectives. A general rule of thumb in the social sciences is that a good research problem is one that would generate a variety of viewpoints from a composite audience made up of reasonable people. 3. Researchability This isn't a real word but it represents an important aspect of creating a good research statement. It seems a bit obvious, but you don't want to find yourself in the midst of investigating a complex research project and realize that you don't have enough prior research to draw from for your analysis. There's nothing inherently wrong with original research, but you must choose research problems that can be supported, in some way, by the resources available to you. If you are not sure if something is researchable, don't assume that it isn't if you don't find information right away--seek help from a librarian !

NOTE: Do not confuse a research problem with a research topic. A topic is something to read and obtain information about, whereas a problem is something to be solved or framed as a question raised for inquiry, consideration, or solution, or explained as a source of perplexity, distress, or vexation. In short, a research topic is something to be understood; a research problem is something that needs to be investigated.

IV. Asking Analytical Questions about the Research Problem

Research problems in the social and behavioral sciences are often analyzed around critical questions that must be investigated. These questions can be explicitly listed in the introduction [i.e., "This study addresses three research questions about women's psychological recovery from domestic abuse in multi-generational home settings..."], or, the questions are implied in the text as specific areas of study related to the research problem. Explicitly listing your research questions at the end of your introduction can help in designing a clear roadmap of what you plan to address in your study, whereas, implicitly integrating them into the text of the introduction allows you to create a more compelling narrative around the key issues under investigation. Either approach is appropriate.

The number of questions you attempt to address should be based on the complexity of the problem you are investigating and what areas of inquiry you find most critical to study. Practical considerations, such as, the length of the paper you are writing or the availability of resources to analyze the issue can also factor in how many questions to ask. In general, however, there should be no more than four research questions underpinning a single research problem.

Given this, well-developed analytical questions can focus on any of the following:

- Highlights a genuine dilemma, area of ambiguity, or point of confusion about a topic open to interpretation by your readers;

- Yields an answer that is unexpected and not obvious rather than inevitable and self-evident;

- Provokes meaningful thought or discussion;

- Raises the visibility of the key ideas or concepts that may be understudied or hidden;

- Suggests the need for complex analysis or argument rather than a basic description or summary; and,

- Offers a specific path of inquiry that avoids eliciting generalizations about the problem.

NOTE: Questions of how and why concerning a research problem often require more analysis than questions about who, what, where, and when. You should still ask yourself these latter questions, however. Thinking introspectively about the who, what, where, and when of a research problem can help ensure that you have thoroughly considered all aspects of the problem under investigation and helps define the scope of the study in relation to the problem.

V. Mistakes to Avoid

Beware of circular reasoning! Do not state the research problem as simply the absence of the thing you are suggesting. For example, if you propose the following, "The problem in this community is that there is no hospital," this only leads to a research problem where:

- The need is for a hospital

- The objective is to create a hospital

- The method is to plan for building a hospital, and

- The evaluation is to measure if there is a hospital or not.

This is an example of a research problem that fails the "So What?" test . In this example, the problem does not reveal the relevance of why you are investigating the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., perhaps there's a hospital in the community ten miles away]; it does not elucidate the significance of why one should study the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., that hospital in the community ten miles away has no emergency room]; the research problem does not offer an intellectual pathway towards adding new knowledge or clarifying prior knowledge [e.g., the county in which there is no hospital already conducted a study about the need for a hospital, but it was conducted ten years ago]; and, the problem does not offer meaningful outcomes that lead to recommendations that can be generalized for other situations or that could suggest areas for further research [e.g., the challenges of building a new hospital serves as a case study for other communities].

Alvesson, Mats and Jörgen Sandberg. “Generating Research Questions Through Problematization.” Academy of Management Review 36 (April 2011): 247-271 ; Choosing and Refining Topics. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; D'Souza, Victor S. "Use of Induction and Deduction in Research in Social Sciences: An Illustration." Journal of the Indian Law Institute 24 (1982): 655-661; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); How to Write a Research Question. The Writing Center. George Mason University; Invention: Developing a Thesis Statement. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Problem Statements PowerPoint Presentation. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Procter, Margaret. Using Thesis Statements. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518; Trochim, William M.K. Problem Formulation. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Walk, Kerry. Asking an Analytical Question. [Class handout or worksheet]. Princeton University; White, Patrick. Developing Research Questions: A Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2009; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

- << Previous: Background Information

- Next: Theoretical Framework >>

- Last Updated: May 20, 2024 9:47 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Table of Contents

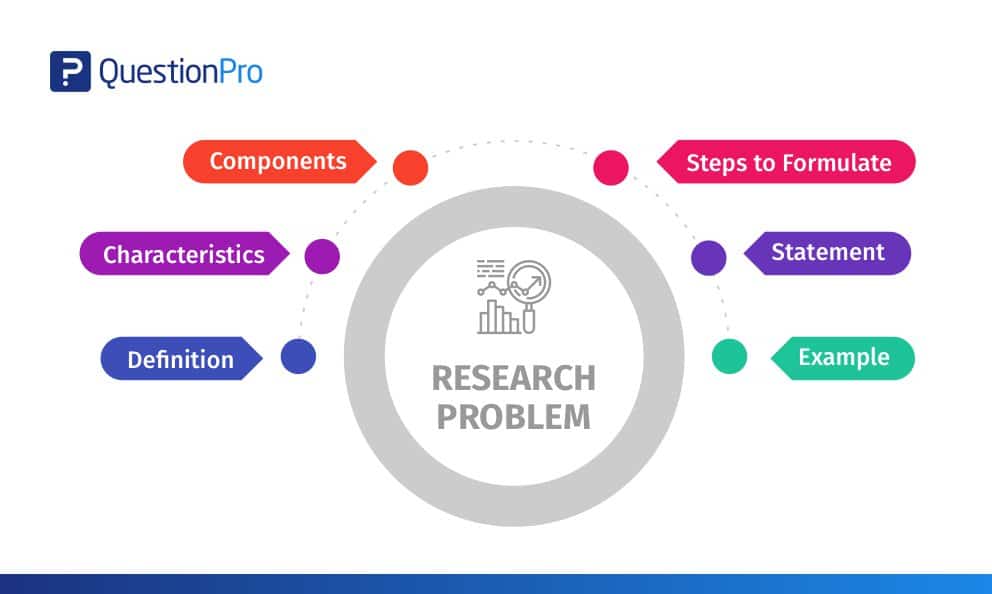

Research Problem

Definition:

Research problem is a specific and well-defined issue or question that a researcher seeks to investigate through research. It is the starting point of any research project, as it sets the direction, scope, and purpose of the study.

Types of Research Problems

Types of Research Problems are as follows:

Descriptive problems

These problems involve describing or documenting a particular phenomenon, event, or situation. For example, a researcher might investigate the demographics of a particular population, such as their age, gender, income, and education.

Exploratory problems

These problems are designed to explore a particular topic or issue in depth, often with the goal of generating new ideas or hypotheses. For example, a researcher might explore the factors that contribute to job satisfaction among employees in a particular industry.

Explanatory Problems

These problems seek to explain why a particular phenomenon or event occurs, and they typically involve testing hypotheses or theories. For example, a researcher might investigate the relationship between exercise and mental health, with the goal of determining whether exercise has a causal effect on mental health.

Predictive Problems

These problems involve making predictions or forecasts about future events or trends. For example, a researcher might investigate the factors that predict future success in a particular field or industry.

Evaluative Problems

These problems involve assessing the effectiveness of a particular intervention, program, or policy. For example, a researcher might evaluate the impact of a new teaching method on student learning outcomes.

How to Define a Research Problem

Defining a research problem involves identifying a specific question or issue that a researcher seeks to address through a research study. Here are the steps to follow when defining a research problem:

- Identify a broad research topic : Start by identifying a broad topic that you are interested in researching. This could be based on your personal interests, observations, or gaps in the existing literature.

- Conduct a literature review : Once you have identified a broad topic, conduct a thorough literature review to identify the current state of knowledge in the field. This will help you identify gaps or inconsistencies in the existing research that can be addressed through your study.

- Refine the research question: Based on the gaps or inconsistencies identified in the literature review, refine your research question to a specific, clear, and well-defined problem statement. Your research question should be feasible, relevant, and important to the field of study.

- Develop a hypothesis: Based on the research question, develop a hypothesis that states the expected relationship between variables.

- Define the scope and limitations: Clearly define the scope and limitations of your research problem. This will help you focus your study and ensure that your research objectives are achievable.

- Get feedback: Get feedback from your advisor or colleagues to ensure that your research problem is clear, feasible, and relevant to the field of study.

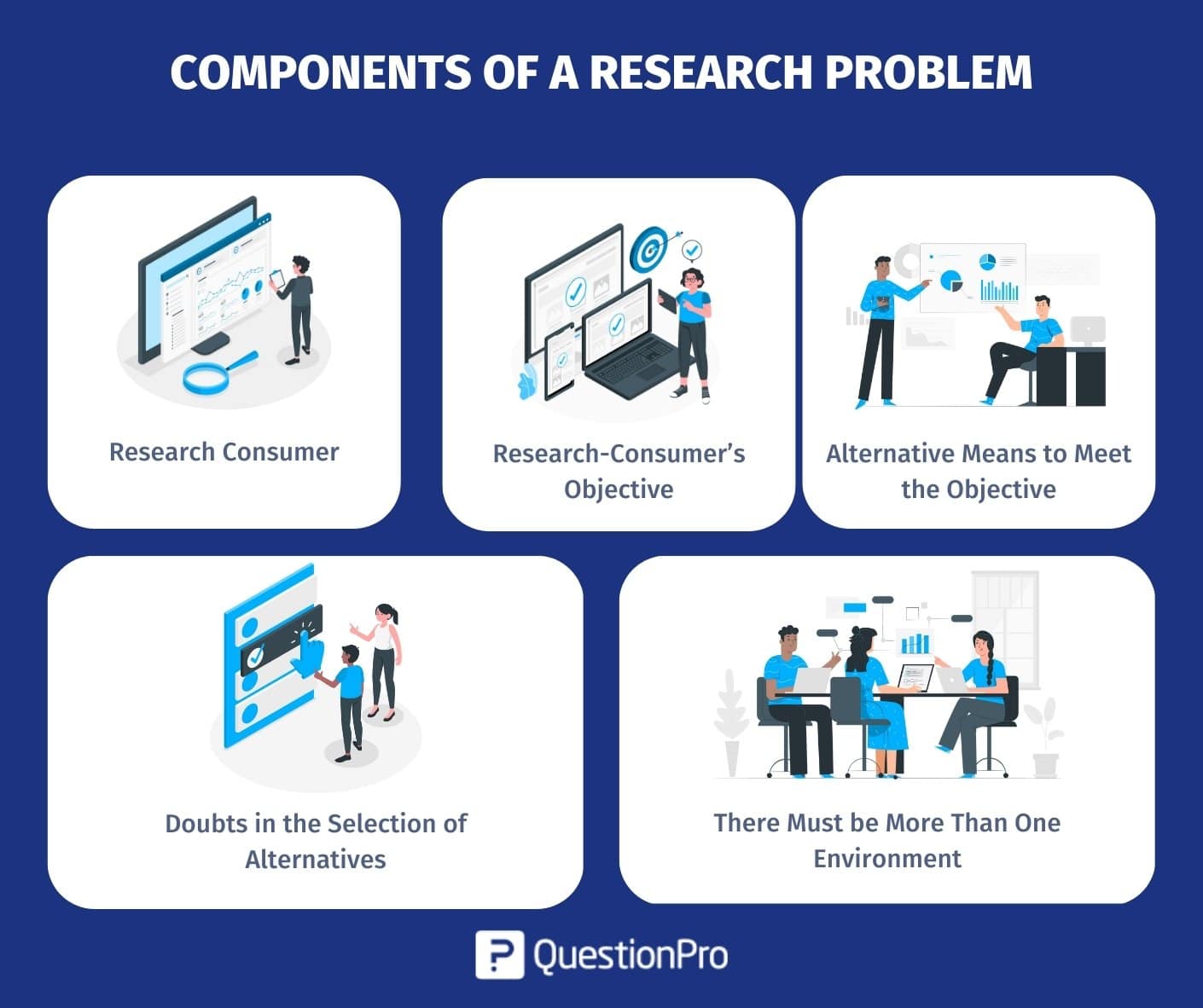

Components of a Research Problem

The components of a research problem typically include the following:

- Topic : The general subject or area of interest that the research will explore.

- Research Question : A clear and specific question that the research seeks to answer or investigate.

- Objective : A statement that describes the purpose of the research, what it aims to achieve, and the expected outcomes.

- Hypothesis : An educated guess or prediction about the relationship between variables, which is tested during the research.

- Variables : The factors or elements that are being studied, measured, or manipulated in the research.

- Methodology : The overall approach and methods that will be used to conduct the research.

- Scope and Limitations : A description of the boundaries and parameters of the research, including what will be included and excluded, and any potential constraints or limitations.

- Significance: A statement that explains the potential value or impact of the research, its contribution to the field of study, and how it will add to the existing knowledge.

Research Problem Examples

Following are some Research Problem Examples:

Research Problem Examples in Psychology are as follows:

- Exploring the impact of social media on adolescent mental health.

- Investigating the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for treating anxiety disorders.

- Studying the impact of prenatal stress on child development outcomes.

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to addiction and relapse in substance abuse treatment.

- Examining the impact of personality traits on romantic relationships.

Research Problem Examples in Sociology are as follows:

- Investigating the relationship between social support and mental health outcomes in marginalized communities.

- Studying the impact of globalization on labor markets and employment opportunities.

- Analyzing the causes and consequences of gentrification in urban neighborhoods.

- Investigating the impact of family structure on social mobility and economic outcomes.

- Examining the effects of social capital on community development and resilience.

Research Problem Examples in Economics are as follows:

- Studying the effects of trade policies on economic growth and development.

- Analyzing the impact of automation and artificial intelligence on labor markets and employment opportunities.

- Investigating the factors that contribute to economic inequality and poverty.

- Examining the impact of fiscal and monetary policies on inflation and economic stability.

- Studying the relationship between education and economic outcomes, such as income and employment.

Political Science

Research Problem Examples in Political Science are as follows:

- Analyzing the causes and consequences of political polarization and partisan behavior.

- Investigating the impact of social movements on political change and policymaking.

- Studying the role of media and communication in shaping public opinion and political discourse.

- Examining the effectiveness of electoral systems in promoting democratic governance and representation.

- Investigating the impact of international organizations and agreements on global governance and security.

Environmental Science

Research Problem Examples in Environmental Science are as follows:

- Studying the impact of air pollution on human health and well-being.

- Investigating the effects of deforestation on climate change and biodiversity loss.

- Analyzing the impact of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems and food webs.

- Studying the relationship between urban development and ecological resilience.

- Examining the effectiveness of environmental policies and regulations in promoting sustainability and conservation.

Research Problem Examples in Education are as follows:

- Investigating the impact of teacher training and professional development on student learning outcomes.

- Studying the effectiveness of technology-enhanced learning in promoting student engagement and achievement.

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to achievement gaps and educational inequality.

- Examining the impact of parental involvement on student motivation and achievement.

- Studying the effectiveness of alternative educational models, such as homeschooling and online learning.

Research Problem Examples in History are as follows:

- Analyzing the social and economic factors that contributed to the rise and fall of ancient civilizations.

- Investigating the impact of colonialism on indigenous societies and cultures.

- Studying the role of religion in shaping political and social movements throughout history.

- Analyzing the impact of the Industrial Revolution on economic and social structures.

- Examining the causes and consequences of global conflicts, such as World War I and II.

Research Problem Examples in Business are as follows:

- Studying the impact of corporate social responsibility on brand reputation and consumer behavior.

- Investigating the effectiveness of leadership development programs in improving organizational performance and employee satisfaction.

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful entrepreneurship and small business development.

- Examining the impact of mergers and acquisitions on market competition and consumer welfare.

- Studying the effectiveness of marketing strategies and advertising campaigns in promoting brand awareness and sales.

Research Problem Example for Students

An Example of a Research Problem for Students could be:

“How does social media usage affect the academic performance of high school students?”

This research problem is specific, measurable, and relevant. It is specific because it focuses on a particular area of interest, which is the impact of social media on academic performance. It is measurable because the researcher can collect data on social media usage and academic performance to evaluate the relationship between the two variables. It is relevant because it addresses a current and important issue that affects high school students.

To conduct research on this problem, the researcher could use various methods, such as surveys, interviews, and statistical analysis of academic records. The results of the study could provide insights into the relationship between social media usage and academic performance, which could help educators and parents develop effective strategies for managing social media use among students.

Another example of a research problem for students:

“Does participation in extracurricular activities impact the academic performance of middle school students?”

This research problem is also specific, measurable, and relevant. It is specific because it focuses on a particular type of activity, extracurricular activities, and its impact on academic performance. It is measurable because the researcher can collect data on students’ participation in extracurricular activities and their academic performance to evaluate the relationship between the two variables. It is relevant because extracurricular activities are an essential part of the middle school experience, and their impact on academic performance is a topic of interest to educators and parents.

To conduct research on this problem, the researcher could use surveys, interviews, and academic records analysis. The results of the study could provide insights into the relationship between extracurricular activities and academic performance, which could help educators and parents make informed decisions about the types of activities that are most beneficial for middle school students.

Applications of Research Problem

Applications of Research Problem are as follows:

- Academic research: Research problems are used to guide academic research in various fields, including social sciences, natural sciences, humanities, and engineering. Researchers use research problems to identify gaps in knowledge, address theoretical or practical problems, and explore new areas of study.

- Business research : Research problems are used to guide business research, including market research, consumer behavior research, and organizational research. Researchers use research problems to identify business challenges, explore opportunities, and develop strategies for business growth and success.

- Healthcare research : Research problems are used to guide healthcare research, including medical research, clinical research, and health services research. Researchers use research problems to identify healthcare challenges, develop new treatments and interventions, and improve healthcare delivery and outcomes.

- Public policy research : Research problems are used to guide public policy research, including policy analysis, program evaluation, and policy development. Researchers use research problems to identify social issues, assess the effectiveness of existing policies and programs, and develop new policies and programs to address societal challenges.

- Environmental research : Research problems are used to guide environmental research, including environmental science, ecology, and environmental management. Researchers use research problems to identify environmental challenges, assess the impact of human activities on the environment, and develop sustainable solutions to protect the environment.

Purpose of Research Problems

The purpose of research problems is to identify an area of study that requires further investigation and to formulate a clear, concise and specific research question. A research problem defines the specific issue or problem that needs to be addressed and serves as the foundation for the research project.

Identifying a research problem is important because it helps to establish the direction of the research and sets the stage for the research design, methods, and analysis. It also ensures that the research is relevant and contributes to the existing body of knowledge in the field.

A well-formulated research problem should:

- Clearly define the specific issue or problem that needs to be investigated

- Be specific and narrow enough to be manageable in terms of time, resources, and scope

- Be relevant to the field of study and contribute to the existing body of knowledge

- Be feasible and realistic in terms of available data, resources, and research methods

- Be interesting and intellectually stimulating for the researcher and potential readers or audiences.

Characteristics of Research Problem

The characteristics of a research problem refer to the specific features that a problem must possess to qualify as a suitable research topic. Some of the key characteristics of a research problem are:

- Clarity : A research problem should be clearly defined and stated in a way that it is easily understood by the researcher and other readers. The problem should be specific, unambiguous, and easy to comprehend.

- Relevance : A research problem should be relevant to the field of study, and it should contribute to the existing body of knowledge. The problem should address a gap in knowledge, a theoretical or practical problem, or a real-world issue that requires further investigation.

- Feasibility : A research problem should be feasible in terms of the availability of data, resources, and research methods. It should be realistic and practical to conduct the study within the available time, budget, and resources.

- Novelty : A research problem should be novel or original in some way. It should represent a new or innovative perspective on an existing problem, or it should explore a new area of study or apply an existing theory to a new context.

- Importance : A research problem should be important or significant in terms of its potential impact on the field or society. It should have the potential to produce new knowledge, advance existing theories, or address a pressing societal issue.

- Manageability : A research problem should be manageable in terms of its scope and complexity. It should be specific enough to be investigated within the available time and resources, and it should be broad enough to provide meaningful results.

Advantages of Research Problem

The advantages of a well-defined research problem are as follows:

- Focus : A research problem provides a clear and focused direction for the research study. It ensures that the study stays on track and does not deviate from the research question.

- Clarity : A research problem provides clarity and specificity to the research question. It ensures that the research is not too broad or too narrow and that the research objectives are clearly defined.

- Relevance : A research problem ensures that the research study is relevant to the field of study and contributes to the existing body of knowledge. It addresses gaps in knowledge, theoretical or practical problems, or real-world issues that require further investigation.

- Feasibility : A research problem ensures that the research study is feasible in terms of the availability of data, resources, and research methods. It ensures that the research is realistic and practical to conduct within the available time, budget, and resources.

- Novelty : A research problem ensures that the research study is original and innovative. It represents a new or unique perspective on an existing problem, explores a new area of study, or applies an existing theory to a new context.

- Importance : A research problem ensures that the research study is important and significant in terms of its potential impact on the field or society. It has the potential to produce new knowledge, advance existing theories, or address a pressing societal issue.

- Rigor : A research problem ensures that the research study is rigorous and follows established research methods and practices. It ensures that the research is conducted in a systematic, objective, and unbiased manner.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

The Research Problem & Statement

What they are & how to write them (with examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | March 2023

If you’re new to academic research, you’re bound to encounter the concept of a “ research problem ” or “ problem statement ” fairly early in your learning journey. Having a good research problem is essential, as it provides a foundation for developing high-quality research, from relatively small research papers to a full-length PhD dissertations and theses.

In this post, we’ll unpack what a research problem is and how it’s related to a problem statement . We’ll also share some examples and provide a step-by-step process you can follow to identify and evaluate study-worthy research problems for your own project.

Overview: Research Problem 101

What is a research problem.

- What is a problem statement?

Where do research problems come from?

- How to find a suitable research problem

- Key takeaways

A research problem is, at the simplest level, the core issue that a study will try to solve or (at least) examine. In other words, it’s an explicit declaration about the problem that your dissertation, thesis or research paper will address. More technically, it identifies the research gap that the study will attempt to fill (more on that later).

Let’s look at an example to make the research problem a little more tangible.

To justify a hypothetical study, you might argue that there’s currently a lack of research regarding the challenges experienced by first-generation college students when writing their dissertations [ PROBLEM ] . As a result, these students struggle to successfully complete their dissertations, leading to higher-than-average dropout rates [ CONSEQUENCE ]. Therefore, your study will aim to address this lack of research – i.e., this research problem [ SOLUTION ].

A research problem can be theoretical in nature, focusing on an area of academic research that is lacking in some way. Alternatively, a research problem can be more applied in nature, focused on finding a practical solution to an established problem within an industry or an organisation. In other words, theoretical research problems are motivated by the desire to grow the overall body of knowledge , while applied research problems are motivated by the need to find practical solutions to current real-world problems (such as the one in the example above).

As you can probably see, the research problem acts as the driving force behind any study , as it directly shapes the research aims, objectives and research questions , as well as the research approach. Therefore, it’s really important to develop a very clearly articulated research problem before you even start your research proposal . A vague research problem will lead to unfocused, potentially conflicting research aims, objectives and research questions .

What is a research problem statement?

As the name suggests, a problem statement (within a research context, at least) is an explicit statement that clearly and concisely articulates the specific research problem your study will address. While your research problem can span over multiple paragraphs, your problem statement should be brief , ideally no longer than one paragraph . Importantly, it must clearly state what the problem is (whether theoretical or practical in nature) and how the study will address it.

Here’s an example of a statement of the problem in a research context:

Rural communities across Ghana lack access to clean water, leading to high rates of waterborne illnesses and infant mortality. Despite this, there is little research investigating the effectiveness of community-led water supply projects within the Ghanaian context. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the effectiveness of such projects in improving access to clean water and reducing rates of waterborne illnesses in these communities.

As you can see, this problem statement clearly and concisely identifies the issue that needs to be addressed (i.e., a lack of research regarding the effectiveness of community-led water supply projects) and the research question that the study aims to answer (i.e., are community-led water supply projects effective in reducing waterborne illnesses?), all within one short paragraph.

Need a helping hand?

Wherever there is a lack of well-established and agreed-upon academic literature , there is an opportunity for research problems to arise, since there is a paucity of (credible) knowledge. In other words, research problems are derived from research gaps . These gaps can arise from various sources, including the emergence of new frontiers or new contexts, as well as disagreements within the existing research.

Let’s look at each of these scenarios:

New frontiers – new technologies, discoveries or breakthroughs can open up entirely new frontiers where there is very little existing research, thereby creating fresh research gaps. For example, as generative AI technology became accessible to the general public in 2023, the full implications and knock-on effects of this were (or perhaps, still are) largely unknown and therefore present multiple avenues for researchers to explore.

New contexts – very often, existing research tends to be concentrated on specific contexts and geographies. Therefore, even within well-studied fields, there is often a lack of research within niche contexts. For example, just because a study finds certain results within a western context doesn’t mean that it would necessarily find the same within an eastern context. If there’s reason to believe that results may vary across these geographies, a potential research gap emerges.

Disagreements – within many areas of existing research, there are (quite naturally) conflicting views between researchers, where each side presents strong points that pull in opposing directions. In such cases, it’s still somewhat uncertain as to which viewpoint (if any) is more accurate. As a result, there is room for further research in an attempt to “settle” the debate.

Of course, many other potential scenarios can give rise to research gaps, and consequently, research problems, but these common ones are a useful starting point. If you’re interested in research gaps, you can learn more here .

How to find a research problem

Given that research problems flow from research gaps , finding a strong research problem for your research project means that you’ll need to first identify a clear research gap. Below, we’ll present a four-step process to help you find and evaluate potential research problems.

If you’ve read our other articles about finding a research topic , you’ll find the process below very familiar as the research problem is the foundation of any study . In other words, finding a research problem is much the same as finding a research topic.

Step 1 – Identify your area of interest

Naturally, the starting point is to first identify a general area of interest . Chances are you already have something in mind, but if not, have a look at past dissertations and theses within your institution to get some inspiration. These present a goldmine of information as they’ll not only give you ideas for your own research, but they’ll also help you see exactly what the norms and expectations are for these types of projects.

At this stage, you don’t need to get super specific. The objective is simply to identify a couple of potential research areas that interest you. For example, if you’re undertaking research as part of a business degree, you may be interested in social media marketing strategies for small businesses, leadership strategies for multinational companies, etc.

Depending on the type of project you’re undertaking, there may also be restrictions or requirements regarding what topic areas you’re allowed to investigate, what type of methodology you can utilise, etc. So, be sure to first familiarise yourself with your institution’s specific requirements and keep these front of mind as you explore potential research ideas.

Step 2 – Review the literature and develop a shortlist

Once you’ve decided on an area that interests you, it’s time to sink your teeth into the literature . In other words, you’ll need to familiarise yourself with the existing research regarding your interest area. Google Scholar is a good starting point for this, as you can simply enter a few keywords and quickly get a feel for what’s out there. Keep an eye out for recent literature reviews and systematic review-type journal articles, as these will provide a good overview of the current state of research.

At this stage, you don’t need to read every journal article from start to finish . A good strategy is to pay attention to the abstract, intro and conclusion , as together these provide a snapshot of the key takeaways. As you work your way through the literature, keep an eye out for what’s missing – in other words, what questions does the current research not answer adequately (or at all)? Importantly, pay attention to the section titled “ further research is needed ”, typically found towards the very end of each journal article. This section will specifically outline potential research gaps that you can explore, based on the current state of knowledge (provided the article you’re looking at is recent).

Take the time to engage with the literature and develop a big-picture understanding of the current state of knowledge. Reviewing the literature takes time and is an iterative process , but it’s an essential part of the research process, so don’t cut corners at this stage.

As you work through the review process, take note of any potential research gaps that are of interest to you. From there, develop a shortlist of potential research gaps (and resultant research problems) – ideally 3 – 5 options that interest you.

Step 3 – Evaluate your potential options

Once you’ve developed your shortlist, you’ll need to evaluate your options to identify a winner. There are many potential evaluation criteria that you can use, but we’ll outline three common ones here: value, practicality and personal appeal.

Value – a good research problem needs to create value when successfully addressed. Ask yourself:

- Who will this study benefit (e.g., practitioners, researchers, academia)?

- How will it benefit them specifically?

- How much will it benefit them?

Practicality – a good research problem needs to be manageable in light of your resources. Ask yourself:

- What data will I need access to?

- What knowledge and skills will I need to undertake the analysis?

- What equipment or software will I need to process and/or analyse the data?

- How much time will I need?

- What costs might I incur?

Personal appeal – a research project is a commitment, so the research problem that you choose needs to be genuinely attractive and interesting to you. Ask yourself:

- How appealing is the prospect of solving this research problem (on a scale of 1 – 10)?

- Why, specifically, is it attractive (or unattractive) to me?

- Does the research align with my longer-term goals (e.g., career goals, educational path, etc)?

Depending on how many potential options you have, you may want to consider creating a spreadsheet where you numerically rate each of the options in terms of these criteria. Remember to also include any criteria specified by your institution . From there, tally up the numbers and pick a winner.

Step 4 – Craft your problem statement

Once you’ve selected your research problem, the final step is to craft a problem statement. Remember, your problem statement needs to be a concise outline of what the core issue is and how your study will address it. Aim to fit this within one paragraph – don’t waffle on. Have a look at the problem statement example we mentioned earlier if you need some inspiration.

Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- A research problem is an explanation of the issue that your study will try to solve. This explanation needs to highlight the problem , the consequence and the solution or response.

- A problem statement is a clear and concise summary of the research problem , typically contained within one paragraph.

- Research problems emerge from research gaps , which themselves can emerge from multiple potential sources, including new frontiers, new contexts or disagreements within the existing literature.

- To find a research problem, you need to first identify your area of interest , then review the literature and develop a shortlist, after which you’ll evaluate your options, select a winner and craft a problem statement .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

I APPRECIATE YOUR CONCISE AND MIND-CAPTIVATING INSIGHTS ON THE STATEMENT OF PROBLEMS. PLEASE I STILL NEED SOME SAMPLES RELATED TO SUICIDES.

Very pleased and appreciate clear information.

Your videos and information have been a life saver for me throughout my dissertation journey. I wish I’d discovered them sooner. Thank you!

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- How it works

Research Problem – Definition, Steps & Tips

Published by Jamie Walker at August 12th, 2021 , Revised On October 3, 2023

Once you have chosen a research topic, the next stage is to explain the research problem: the detailed issue, ambiguity of the research, gap analysis, or gaps in knowledge and findings that you will discuss.

Here, in this article, we explore a research problem in a dissertation or an essay with some research problem examples to help you better understand how and when you should write a research problem.

“A research problem is a specific statement relating to an area of concern and is contingent on the type of research. Some research studies focus on theoretical and practical problems, while some focus on only one.”

The problem statement in the dissertation, essay, research paper, and other academic papers should be clearly stated and intended to expand information, knowledge, and contribution to change.

This article will assist in identifying and elaborating a research problem if you are unsure how to define your research problem. The most notable challenge in the research process is to formulate and identify a research problem. Formulating a problem statement and research questions while finalizing the research proposal or introduction for your dissertation or thesis is necessary.

Why is Research Problem Critical?

An interesting research topic is only the first step. The real challenge of the research process is to develop a well-rounded research problem.

A well-formulated research problem helps understand the research procedure; without it, your research will appear unforeseeable and awkward.

Research is a procedure based on a sequence and a research problem aids in following and completing the research in a sequence. Repetition of existing literature is something that should be avoided in research.

Therefore research problem in a dissertation or an essay needs to be well thought out and presented with a clear purpose. Hence, your research work contributes more value to existing knowledge. You need to be well aware of the problem so you can present logical solutions.

Formulating a research problem is the first step of conducting research, whether you are writing an essay, research paper, dissertation , or research proposal .

Looking for dissertation help?

Researchprospect to the rescue then.

We have expert writers on our team who are skilled at helping students with dissertations across a variety of STEM disciplines. Guaranteeing 100% satisfaction!

Step 1: Identifying Problem Area – What is Research Problem

The most significant step in any research is to look for unexplored areas, topics, and controversies . You aim to find gaps that your work will fill. Here are some research problem examples for you to better understand the concept.

Practical Research Problems

To conduct practical research, you will need practical research problems that are typically identified by analysing reports, previous research studies, and interactions with the experienced personals of pertinent disciplines. You might search for:

- Problems with performance or competence in an organization

- Institutional practices that could be enhanced

- Practitioners of relevant fields and their areas of concern

- Problems confronted by specific groups of people within your area of study

If your research work relates to an internship or a job, then it will be critical for you to identify a research problem that addresses certain issues faced by the firm the job or internship pertains to.

Examples of Practical Research Problems

Decreased voter participation in county A, as compared to the rest of the country.

The high employee turnover rate of department X of company Y influenced efficiency and team performance.

A charity institution, Y, suffers a lack of funding resulting in budget cuts for its programmes.

Theoretical Research Problems

Theoretical research relates to predicting, explaining, and understanding various phenomena. It also expands and challenges existing information and knowledge.

Identification of a research problem in theoretical research is achieved by analysing theories and fresh research literature relating to a broad area of research. This practice helps to find gaps in the research done by others and endorse the argument of your topic.

Here are some questions that you should bear in mind.

- A case or framework that has not been deeply analysed

- An ambiguity between more than one viewpoints

- An unstudied condition or relationships

- A problematic issue that needs to be addressed

Theoretical issues often contain practical implications, but immediate issues are often not resolved by these results. If that is the case, you might want to adopt a different research approach to achieve the desired outcomes.

Examples of Theoretical Research Problems

Long-term Vitamin D deficiency affects cardiac patients are not well researched.

The relationship between races, sex, and income imbalances needs to be studied with reference to the economy of a specific country or region.

The disagreement among historians of Scottish nationalism regarding the contributions of Imperial Britain in the creation of the national identity for Scotland.

Hire an Expert Writer

Proposal and dissertation orders completed by our expert writers are

- Formally drafted in academic style

- Plagiarism free

- 100% Confidential

- Never Resold

- Include unlimited free revisions

- Completed to match exact client requirements

Step 2: Understanding the Research Problem

The researcher further investigates the selected area of research to find knowledge and information relating to the research problem to address the findings in the research.

Background and Rationale

- Population influenced by the problem?

- Is it a persistent problem, or is it recently revealed?

- Research that has already been conducted on this problem?

- Any proposed solution to the problem?

- Recent arguments concerning the problem, what are the gaps in the problem?

How to Write a First Class Dissertation Proposal or Research Proposal

Particularity and Suitability

- What specific place, time, and/or people will be focused on?

- Any aspects of research that you may not be able to deal with?

- What will be the concerns if the problem remains unresolved?

- What are the benefices of the problem resolution (e.g. future researcher or organisation’s management)?

Example of a Specific Research Problem

A non-profit institution X has been examined on their existing support base retention, but the existing research does not incorporate an understanding of how to effectively target new donors. To continue their work, the institution needs more research and find strategies for effective fundraising.

Once the problem is narrowed down, the next stage is to propose a problem statement and hypothesis or research questions.

If you are unsure about what a research problem is and how to define the research problem, then you might want to take advantage of our dissertation proposal writing service. You may also want to take a look at our essay writing service if you need help with identifying a research problem for your essay.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is research problem with example.

A research problem is a specific challenge that requires investigation. Example: “What is the impact of social media on mental health among adolescents?” This problem drives research to analyse the relationship between social media use and mental well-being in young people.

How many types of research problems do we have?

- Descriptive: Describing phenomena as they exist.

- Explanatory: Understanding causes and effects.

- Exploratory: Investigating little-understood phenomena.

- Predictive: Forecasting future outcomes.

- Prescriptive: Recommending actions.

- Normative: Describing what ought to be.

What are the principles of the research problem?

- Relevance: Addresses a significant issue.

- Re searchability: Amenable to empirical investigation.

- Clarity: Clearly defined without ambiguity.

- Specificity: Narrowly framed, avoiding vagueness.

- Feasibility: Realistic to conduct with available resources.

- Novelty: Offers new insights or challenges existing knowledge.

- Ethical considerations: Respect rights, dignity, and safety.

Why is research problem important?

A research problem is crucial because it identifies knowledge gaps, directs the inquiry’s focus, and forms the foundation for generating hypotheses or questions. It drives the methodology and determination of study relevance, ensuring that research contributes meaningfully to academic discourse and potentially addresses real-world challenges.

How do you write a research problem?

To write a research problem, identify a knowledge gap or an unresolved issue in your field. Start with a broad topic, then narrow it down. Clearly articulate the problem in a concise statement, ensuring it’s researchable, significant, and relevant. Ground it in the existing literature to highlight its importance and context.

How can we solve research problem?

To solve a research problem, start by conducting a thorough literature review. Formulate hypotheses or research questions. Choose an appropriate research methodology. Collect and analyse data systematically. Interpret findings in the context of existing knowledge. Ensure validity and reliability, and discuss implications, limitations, and potential future research directions.

You May Also Like

How to write a hypothesis for dissertation,? A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested with the help of experimental or theoretical research.

Not sure how to approach a company for your primary research study? Don’t worry. Here we have some tips for you to successfully gather primary study.

Find how to write research questions with the mentioned steps required for a perfect research question. Choose an interesting topic and begin your research.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Clin Epidemiol

From ideas to studies: how to get ideas and sharpen them into research questions

Jan p vandenbroucke.

1 Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands

2 Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark

3 Department of Medical Statistics and Centre for Global NCDs, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK

Neil Pearce

Where do new research questions come from? This is at best only partially taught in courses or textbooks about clinical or epidemiological research. Methods are taught under the assumption that a researcher already knows the research question and knows which methods will fit that question. Similarly, the real complexity of the thought processes that lead to a scientific undertaking is almost never described in published papers. In this paper, we first discuss how to get an idea that is worth researching. We describe sources of new ideas and how to foster a creative attitude by “cultivating your thoughts”. Only a few of these ideas will make it into a study. Next, we describe how to sharpen and focus a research question so that a study becomes feasible and a valid test of the underlying idea. To do this, the idea needs to be “pruned”. Pruning a research question means cutting away anything that is unnecessary, so that only the essence remains. This includes determining both the latent and the stated objectives, specific pruning questions, and the use of specific schemes to structure reasoning. After this, the following steps include preparation of a brief protocol, conduct of a pilot study, and writing a draft of the paper including draft tables. Then you are ready to carry out your research.

Introduction

How do you get an idea for a study? How do you turn your idea into a testable hypothesis, and turn this into an appropriate and feasible study design? This is usually at best only partially taught in epidemiology courses. Most courses and textbooks assume that you know your research question and the general methods that you will need to answer it. Somehow it is assumed that you can readily translate your idea into a specific framework, such as the PICO framework (Patient, Intervention, Control or Comparison, Outcome) 1 or the FINER framework (Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, and Relevant) 2 or that you can fit it into counterfactual reasoning. 3 However, before describing your project in one of these frameworks, you first need to have an idea for your study and think about it in general terms: why you might do a study and how you might do a study.

This paper considers the complex process of having ideas, keeping track of them, turning them into studies, trying them out in pilot studies, and writing a draft paper before you finally embark on your study.

The paper is intended for novice researchers in clinical or public health epidemiology. It is not intended to be a comprehensive literature review about creativity, nor a sociology or philosophical treatise about why scientists get particular ideas (and not other ideas). It is based on our personal experience of (a combined) 70+ epidemiologic research-years. We have worked on very different topics, mostly on opposite sides of the globe, yet found that our experiences are quite similar. The fact that these issues are rarely covered in epidemiology courses has provided motivation to reflect on our experience.

Getting new ideas

So how do you get an idea? How some juxtaposition of neural patterns in our brain suddenly creates a new idea is a process that we are far from understanding. According to Karl Popper, the origin of new ideas does not matter; the only thing of interest is to devise how to test them. 4 Over the past decades, the literature has been enriched with new ideas about “being creative” in science – as witnessed in the book Innovation Generation by Ness. 5

In the present paper, we will not cover the literature about creativity and discovery in depth, but we will discuss the issues that we consider relevant to epidemiologic research. We will first consider the more general principles.

The real complexity of the thought processes that lead to a scientific undertaking is almost never described in published papers. Immunologist Medawar claimed that in this respect almost all scientific papers may be a fraud – not in the sense that scientists deliberately produce misleading data, but in the sense that the real thought processes that lead to the data and conclusions are not mentioned. 6 Scientists tell us about their real thought processes in memoirs, inaugural, or valedictory lectures – which is why these are so much more interesting than “standard” papers or presentations.

What strikes our minds: regularities or anomalies?

All sciences study a particular “object of knowledge” (eg, “matter”, “life”). Ideas come from experience and previous knowledge or facts about this object of knowledge, although this knowledge is always filtered through the perspective of one or more theories. 7 Epidemiology studies the distribution and determinants of disease in human populations, 8 and epidemiological ideas arise from observing and thinking about populations. 9 These could be clinical populations (ie, clinical experience, sometimes involving just a few patients), exposure-based populations (eg, workers exposed to a particular chemical), or general populations (geographically defined or sociologically defined). Whatever the population we are interested in, ideas come from observing either regularities or anomalies.

The observation of regularities (“induction”) is a common origin of new ideas. 4 , 10 – 13 Philosopher David Hume described “Induction” as: regularly seeing two things happening in succession (like pushing a switch and a light going on) leads to suspicions of causality. As he pointed out, causality can never be proven by the mere observation of “constant conjunctions”, but observing regularities can start our train of thought. 12

An anomaly (or irregularity) strikes our mind, because it defies our expectations. The regularity that we expected was our “hypothesis” (even if it was not really explicitly formulated); the anomaly is a “refutation”. 4 , 13 It forces us to think about other explanations, and these lead to new hypotheses that we then try to test. Thus, scientists do not usually start from hypotheses that are nicely formulated “out of the blue”, but instead start from previous knowledge and experience; when they are challenged by anomalies, scientists seek new explanations. 14

An interesting way to discover anomalies is to enter a new field of research; since you have other background experience than the people already in the field, you see things that they take for granted but that strike you as odd – at the same time, you may also see new explanations for these anomalies. One of the pioneers of clinical epidemiology, Sackett, once wrote that scientists should “retire” from a field as soon as they become “experts”. 15 When you are too long in a field, you will no longer see the anomalies, and you may even obstruct newcomers with new explanations. Of course, there are differences between scientists: some roam across various fields and others stick to a problem area that they explore with increasing depth – then the increasing depth and the new techniques that one needs for advancing one’s thoughts will be like a “new field”.

Taxonomies of discovery

Few researchers have listed the different ways in which one can arrive at new ideas, that is, lists of ways of discovery. We will present two of them – which have very different origins but remarkable similarities. Several examples of studies corresponding to items on these two lists are given in Appendix Examples A1–A10 .

Sources for new ideas about health care evaluation were described by Crombie and Davies in the chapter “Developing the research question” of their book on Research in Health Care that reflects a UK public health experience. 16

- “Review existing practice […] the current organisation and delivery of health care is not as good as it could be […]”

- “Challenge accepted ideas […] much of health care is based on accepted practice rather than research evidence […]” ( Appendix Example A3 )

- “Look for conflicting views […] which indicate either that there is not enough evidence, or that some practitioners are misinformed”

- “Investigate geographical variation […] reflecting on the reasons [for geographical variation] can be a fruitful source of research questions […]” ( Appendix Example A6 )

- “Identify Cinderella topics […] important areas of health care are often overlooked […]”

- “Let loose the imagination […] look for wild or impossible ideas […] free the mind from the constraints of conventional wisdom […].”

A taxonomy for sources of clinical research questions about medical care and clinical problems was proposed by Hulley and Cummings, in the context of clinical research in the US: 2

- “Build on experience;” your own experience, that of close colleagues with whom you can freely discuss your research ideas, and that of a good mentor, because young researchers might not yet have much experience, “An essential strategy for a young investigator is to apprentice himself to an experienced senior scientist who has the time and interest to work with him regularly.”

- ○ By harvesting “the medical literature and attending journal clubs, national and international meetings, seeking informal conversations with other scientists and colleagues”

- ○ “A sceptical attitude about prevailing beliefs can stimulate good research questions”

- ○ Be alert to “careful observation of patients, which has historically been one of the major sources of descriptive studies” ( Appendix Examples A1 and A2 )

- ○ Your experiences in teaching; having to explain something may make you aware of gaps in your knowledge; questions by patients and colleagues may similarly identify things that we do not fully understand or ignore

- “Keep the imagination roaming […]” by a mixture of creativity and tenacity; “put an unresolved question clearly in view and turn on the mental switch that lets the mind run freely toward it”.

A special mention needs to be made about the last categories of both the lists: “Let loose the imagination” and “Keep the imagination roaming”. These are especially important to find innovative solutions. In many situations wherein you cannot do a perfect study and you run a grave danger of potential confounding or bias, it helps to “get deeply immersed”: to understand the problem biologically, clinically, socially, organizationally, and environmentally will help you to think about what is happening, why it is happening, and whether you can find situations in which the potential confounders or biases do not exist or exists in reverse. You should forget formal designs and think out of the box: you will find instances of studies that mutually reinforce each other and may even arrive at formulating new designs or analytic solutions (see Appendix Examples A7–A10 ).

Keeping track of your ideas

It is not only important to have good ideas but also important to develop them. Researchers who work in laboratories have the habit of keeping “lab logs”. They write down briefly the results of an experiment, note why they think it went wrong, and how they will perform the next experiment. This permits them to trace how they changed the experiments or even the content and the direction of their research. We should do the same in epidemiologic and clinical research, particularly in the stage of creating new ideas. Such notes about ideas can include not only hypotheses and views or results by others but also drawing directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) (see “Intermezzo: specific schemes to structure reasoning” section) to make the causal structures of ideas clear.

The greatest minds kept track of their thoughts. Charles Darwin’s notebooks document his ideas, his observations, his readings, and new theories and facts that struck him. 17 For example, Darwin noted a story that he heard from his father, a medical practitioner. His father recounted that he had been struck by one of his patients’ ways of expressing himself, because he had attended a parent of the patient who had had the same mannerisms – even though the parent had died when the patient was still an infant. Remarks like these still have relevance today when we think about the heredity and evolution of behavior.

The sociologist C Wright Mills carried the description of the process one step further in the appendix of his book on The Sociological Imagination . 18 He encourages young sociologists to set up a file of stacked cards to keep track of “[…] personal experience and professional activities, studies underway and studies planned […]” which “[…] encourages you to capture ‘fringe thoughts’: various ideas which may be by-products of everyday life, stretches of conversations […]”. These notes are continuously reshuffled, regrouped under new headings, and pondered. Mills denounced the habit of most (social) scientists who feel the need to write about their plans only when they are going to apply for a grant. He thought that scientists should continually work with their file of ideas and regularly take stock of how these have evolved.

Such strategies are still relevant today, even if our “logs” are kept in electronic form, particularly because grant writing has become more demanding, hectic, and time-consuming. From such files, new research projects are born: while your ideas gradually develop, you keep wondering what data you might need to prove a certain proposition, and how you might get those data in the easiest way possible. Often, ideas are reshuffled and regrouped under new headings. A new observation, a new piece of literature may make old ones fall into place, or there may suddenly be a new opportunity to work out an old idea.

A complementary advice recently came in a blog from a contemporary sociologist, Aldrich: his advice is to “Write as if you don’t have the data”, that is, to write “[…] the literature review and planning phase of a project, preferably before it has been locked into a specific research design”. 19

The role of emotions

Underlying the discovery process, there are often two emotions: “surprise” and “indignation”. Surprise is the intellectual emotion when we see something happening against expectation: a patient with an unusual exposure, unusual disease manifestation, sudden cure, or sudden ill-understood deterioration; a laboratory result that is an anomaly; and a sudden epidemic of disease in a population. Indignation is the moral emotion: a group of patients is not being treated well because we lack sufficient knowledge, or because we are blundering in organizing health care or in transmitting and applying public health knowledge. Some passion is useful to bring any undertaking to a good end, be it that the passion should be restrained and channeled into polite undertakings, like in a research protocol. While doing the research project, maintaining some of the original passion will help you to find ways to overcome the daily hassles of research, the misadventures, the difficulties of getting others to collaborate, and the difficulties of getting published ( Appendix Example A11 ).

Sharpening the research question: the pruning

Pruning a research question means cutting away anything that is unnecessary, so that only the essence remains.