Advertisement

Supported by

In Her Fiction, Ayana Mathis Refuses to Ignore Black History

Her second novel, “The Unsettled,” follows three generations in a family divided between the North and the South in 1980s America.

- Share full article

By Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

Honorée Fanonne Jeffers is the author, most recently, of “The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois.”

- Apple Books

- Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

THE UNSETTLED , by Ayana Mathis

As a novelist and a student of history, I’m interested in the question of whether Black novelists must acknowledge history in our work, or if it is possible, in the name of artistic freedom, to truly set it aside. I, for one, submit that Black history will always hover over American literature, whether or not the author intends it to. As Toni Morrison wrote in 1992, the Black American population “preceded every American writer of renown and was, I have come to believe, one of the most furtively radical impinging forces on the country’s literature.”

Ayana Mathis’s explicitly historical second novel, “The Unsettled” — appearing nearly 11 years after her acclaimed debut, “ The Twelve Tribes of Hattie ” — makes a strong case for the fact that the past can never truly be shaken off. Mathis follows three central characters across time and geography: the emotionally delicate Ava, a young mother trying to create a sense of home for herself and her son in 1980s Philadelphia; her wonderfully profane mother, Dutchess, who still lives in Ava’s tiny, all-Black hometown in Alabama; and Ava’s precocious son, Toussaint, who is arguably the book’s protagonist. He begins the novel with a short prologue in which he’s 13, has run away from foster care and is heading down to Bonaparte, Ala., to find Dutchess. Ava is now in prison.

The novel introduces these mysteries — Why is Ava in prison? Where is Toussaint’s father? Why is the boy running toward instead of away from Alabama, as so many Black folks have done since the Great Migration? — before jumping back a few years, to 1985, when Ava drags 10-year-old Toussaint into a homeless shelter in Philadelphia. The mother and son have been thrown out of the home they shared with Abemi, Ava’s abusive husband and Toussaint’s stepfather, in New Jersey. What brought them to this point?

Mathis renders Ava and Toussaint’s time in the shelter in poignant, heartbreaking detail. The staff members are at best cold and insensitive, at worst sexually exploitative. Though Ava tries her best, she increasingly loses connection with reality, reminiscing about her past with Toussaint’s father, Cass, in a series of disorienting, fragmented memories. These episodes, along with the residual trauma from Abemi's abuse, prevent her from nurturing Toussaint, who is left to his own devices, essentially adultified. Her maternal neglect tests the reader’s sympathy as she leaves her child to ready himself for school, forgets to take him to the shelter cafeteria for their meals, doesn’t search for him when he disappears for hours at a time.

Things come to a head when the charismatic Cass comes back into the picture, recruiting Ava for the Black collective he’s founded called Ark — where Ava cuts her hair, becomes a vegetarian, and continues to ignore her son as she falls under the sway of Cass’s unhinged magnetism.

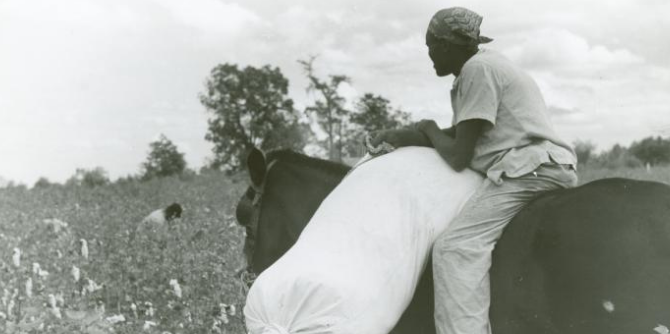

Down south, Dutchess is in a painful predicament of her own: trying to save Bonaparte from white supremacists seeking to displace her from her land, which has been occupied by formerly enslaved African Americans since Reconstruction. “Ava’s pop said Bonaparte was a place for free people,” Mathis writes, “they and the Indians had been helping each other stay free for a hundred years.” Now, white citizens are arriving from the surrounding areas to physically attack the Black residents, with the support of the county’s white sheriff; and local white lawmakers are using legal shenanigans (allegations of unpaid taxes and deeds never filed) to slice off acres of land from Black ownership.

The difference between mother and daughter, however, is that Dutchess is much stronger than Ava — why, we never really find out. Perhaps because she stayed in Bonaparte? Is this where Dutchess learned to fight and to hold onto what is real?

Throughout these two story lines Mathis skillfully and subtly drops allusions to historical events, sending the reader on a kind of intellectual treasure hunt. The title itself evokes the aftermath of settler colonialism, the centuries-long ejection of nonwhites from their homes, which continues to wreak havoc on this country’s Black and Indigenous citizens. And there is the son’s namesake, Toussaint Louverture , the formerly enslaved Haitian general who led the Haitian Revolution and became a hero in the African diaspora. Bonaparte itself is reminiscent of Alabama’s historic Africatown, founded by descendants of the stolen passengers on the slave ship Clotilda . (The name Mathis gives this place is presumably a nod to the French exiles who received plots of land from the U.S. government after the Napoleonic Wars — land formerly inhabited by the Choctaw tribe — on which to settle and grow olives and wine grapes.)

But perhaps most crucial to Mathis’s plot is the 1985 bombing, by the Philadelphia Police Department, of the West Philadelphia rowhouse that was home to MOVE, a collective of radical Black activists committed to self-determination and to their shared ancestral lineage (all members assumed the last name “Africa”). Where the MOVE compound attracted police attention for noise and trash pollution, in “The Unsettled” the police focus on Ark for drug crimes. In using MOVE as a model, though, Mathis nudges us toward residual outrage and grief over this bombing. Yes, the MOVE activists conflicted with their neighbors, but the bombing ordered by Mayor Wilson Goode — the city’s first Black mayor — killed 11 occupants, including five children. The inhumanity of this act continues to traumatize Philadelphia’s Black community nearly 40 years on.

Over the course of the novel Mathis toggles frequently between third-person and first-person points of view, including those of the protagonists and satellite characters alike. It’s not always clear why she chooses to inhabit a given mind, like that of a rude and classist social worker who clearly takes personal offense at other Black women experiencing emotional and financial distress. And there are other perspectives that are left unexplored, like that of the white sheriff who harasses Bonaparte. The shifts in perspective can try the reader’s patience, but they mirror the reality that every historical event inspires multiple, conflicting points of view.

Together, the melding of history and fiction in Mathis’s moving prose reveals a fundamental truth: Black folks want to lead a life of self-determination, free from white supremacist oppression. We’ve been searching, fighting for this self-determination since Europeans forced our African ancestors across the wide water. As “The Unsettled” shows, for Black writers, our history remains ready, eager to shout or whisper onto the page.

THE UNSETTLED | By Ayana Mathis | 321 pp. | Alfred A. Knopf | $29

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

James McBride’s novel sold a million copies, and he isn’t sure how he feels about that, as he considers the critical and commercial success of “The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store.”

How did gender become a scary word? Judith Butler, the theorist who got us talking about the subject , has answers.

You never know what’s going to go wrong in these graphic novels, where Circus tigers, giant spiders, shifting borders and motherhood all threaten to end life as we know it .

When the author Tommy Orange received an impassioned email from a teacher in the Bronx, he dropped everything to visit the students who inspired it.

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

‘The Unsettled’ is an invitation to reject the impersonal

The first novel from ayana mathis since her 2012 bestseller is an antidote to the casual depersonalization its characters endure.

Asked to fill out forms at the Cherry Street Intake Center for the Homeless in Philadelphia, Ava Carson writes a story full of details that have no bearing on her placement in a shelter. She is 45 years old, and her personal history exceeds the allotted space. It is not that she does not understand the task: “She knew that wasn’t the kind of answer they wanted, but she had to tell somebody.” Later, as an imposing shelter official reviews the paperwork, Ava, unprompted, begins to describe her wedding: “Philadelphia. West Oak Lane. Pale yellow dress. Empire waist.”

“ The Unsettled ” by Ayana Mathis is an invitation to reject the impersonal, to find “the real story” in the details that cannot fit on forms. The third-person narration roams throughout the shelter, though there are bursts of first-person from the perspective of Ava’s estranged mother, Dutchess, who lives in the Alabama town of Bonaparte. When Mathis hands the point of view to Miss Simmons, a shelter employee, the language is striking for both its coolness and its degradation of Ava: She is “Miss Carson,” then “this Carson woman,” then “813,” the number of the room she and Toussaint, her 10-year-old son, are assigned.

Read the review of ‘The Twelve Tribes of Hattie’ by Ayana Mathis

This novel, the second from Mathis after her 2012 bestseller, “The Twelve Tribes of Hattie,” is an antidote to the casual depersonalization its characters endure, just as its title can be read as an alternative to the term “homeless.” Ava has left one home, at the insistence of her ex-husband, Abemi, and struggles to find another. In 1986, after a stint in a family shelter, she is reunited with Toussaint’s father, Cass, and the family begins sharing a house with others. At first, it seems conditions for Ava have improved. Of the communal home, Mathis writes, “Their fellowship was called Ark” because “they were a refuge from the devastation and deluge of the city.”

In a wall-mounted “manifesto,” Cass announces, “The fierce are the inheritors of the earth.” Claiming self-sufficiency, he resorts to theft. “Ark was one body,” Mathis writes. “Ava didn’t mind being the hands.” Mathis effectively conveys both the allure and lack of credibility from Cass. The novel is less interested in his machinations than it is in Ava’s choice to overlook them. Her willingness to “be the hands” attenuates slowly. Mathis refuses to rush Ava to the seemingly inevitable break from Cass, a wise decision that extends and deepens the suspense.

Cass makes a glancing reference to “inheritors,” a nod to the thematic importance of inheritance. Mathis also includes street names, house numbers and even intersections, emphasizing how critical it is for people to know where they are and to whom the land or structure belongs. Property is essential to identity of Dutchess back in Alabama, where her sections are simply called Bonaparte, as if she and the town are one, and she makes sacrifices to ward off a development company called Progress and maintain the local Black ownership. “My three hundred acres ain’t going nowhere,” she says. “If I don’t keep it there won’t be any Bonaparte left.”

It is unsurprising that Cass sees Bonaparte as an opportunity for himself. Readers will recognize his scheme long before Ava does. When she finally talks to Dutchess, the call is part reunion and part revelation. The rift between mother and daughter remains slightly opaque throughout the novel. Though they are not particularly compatible, the length and intensity of the estrangement are confounding. “She has convinced herself I had it in for her,” Dutchess says. “She wants things to be simple, but they never were and she thinks that’s my fault.”

Sign up for the Book World newsletter from The Washington Post

Whether in the shelter or the Ark, Ava cannot find what she needs. By contrast, Mathis offers a resonant image of caretaking in Bonaparte. During a time of hardship and hunger, young Ava finds “a pot sitting on the porch” and feeds her grieving mother by the spoonful. A neighbor, Mathis writes, “saved them with her pot of dumplings in the worst winter of their lives.” The pot is an object of nourishment and dignity, a warm relief from the repetitive paperwork, sanctimony and violence that Mathis evokes so well.

Jackie Thomas-Kennedy has written for American Short Fiction and One Story. She was a Wallace Stegner fellow at Stanford University .

The Unsettled

By Ayana Mathis

Knopf. 336 pp. $29.

More from Book World

Best books of 2023: See our picks for the 10 best books of 2023 or dive into the staff picks that Book World writers and editors treasured in 2023. Check out the complete lists of 50 notable works for fiction and the top 50 non-fiction books of last year.

Find your favorite genre: These four new memoirs invite us to sit with the pleasures and pains of family. Lovers of hard facts should check out our roundup of some of the summer’s best historical books . Audiobooks more your thing? We’ve got you covered there, too . We also predicted which recent books will land on Barack Obama’s own summer 2023 list . And if you’re looking forward to what’s still ahead, we rounded up some of the buzziest releases of the summer .

Still need more reading inspiration? Every month, Book World’s editors and critics share their favorite books that they’ve read recently . You can also check out reviews of the latest in fiction and nonfiction .

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

Knowledge is power

Stay in the know about climate impacts and solutions. Subscribe to our weekly newsletter.

By clicking submit, you agree to share your email address with the site owner and Mailchimp to receive emails from the site owner. Use the unsubscribe link in those emails to opt out at any time.

Yale Climate Connections

A critical review of Steven Koonin’s ‘Unsettled’

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

I would normally ignore a book by a non-climate scientist promising “the truth about climate science that you aren’t getting elsewhere.” Such language is a red flag. But I’ve known the author of “Unsettled” since I took his quantum mechanics course as a Ph.D. student at Caltech in the 1970s. He’s smart and I like him, so I’m inclined to give his book a chance.

But smart scientists aren’t always right, and nice guys are still prone to biases – especially if they listen to the wrong people. In an apparent quest for fairness when he led a committee of the American Physical Society (one of my professional organizations) to assess its statement on climate change, he recruited three scientists to represent the 97% consensus, and three contrarians, presumably to speak for the other 3%. The lack of proportionate representation amplified the contrary opinions that he heard, and only in one direction. He completely ignored another, equally unfounded, contrary view. The position sometimes referred to as “doomism” (the belief that the worst-case is inevitable and it is too late to prevent it) was not represented.

The three contrarians had a long and well-documented history of engaging in ad hominem attacks on mainstream climate scientists and misrepresenting their work. Most of the technical mistakes and misrepresentations in “Unsettled” may simply be attributable to Koonin’s trust of those advisors and lack of rigorous independent verification.

Some books CAN be told by their cover. This is one of them.

Unfortunately, “Unsettled” is a book you can accurately judge by its cover. Koonin’s title hints at a logical fallacy called the “strawman” argument. The blurb on the flap confirms this with its opening sentence: “When it comes to climate change, the media, politicians, and other prominent voices have declared that ‘the science is settled.’”

A bit of fact checking by the author or publisher would have shown that this claim is not true. In fact, Koonin makes use of an old strawman concocted by opponents of climate science in the 1990s to create an illusion of arrogant scientists, biased media, and lying politicians – making them easier to attack.

The phrase “science is settled” is repeated as Koonin’s target throughout the book, even though it has never been in common use by climate scientists and their supporters. If it were, then Google and LexisNexis searches would surely turn up instances, but the opposite is true. All the examples I found were from critics claiming that advocates of the consensus had said it.

Bogus ‘ science is settled ‘ rhetoric dating back 25 years

The earliest published use I found was a July 11, 1996, letter to the Wall Street Journal from prominent denier Fred Singer, falsely claiming that the IPCC report had been inappropriately tampered with for political purposes and that “politicians and activists” were “anxious to stipulate that the science is settled. ”

Singer’s strawman gained traction a year later when William O’Keefe, the chairman of Global Climate Coalition (a lobbying organization opposed to climate action) claimed in a statement to Congress that “the [Clinton] Administration repeatedly quotes that [IPCC] sentiment out of context in its statements that the ‘science is settled.’” It stands to reason that repeated use of the phrase “science is settled” would be found in searches if true.

Searches do, however, turn up (in the White House archive) what Clinton actually said only two weeks before Singer’s letter. “The science is clear and compelling: We humans are changing the global climate.” Nobody could argue with that at the time, nor can they now.

There are many examples of physical problems that are difficult to model, have large uncertainties and unpredictable outcomes, put people at risk, and require policy decisions and international treaties. My primary field of planetary defense is one. It’s a clear and compelling fact that the Earth will be hit by another asteroid. We just don’t know where, when, or how bad it will be.

The recent re-entry of an errant Chinese upper stage provides a more concrete analogy. The fact that its orbit would decay and it was going to come down was not in question, and could rightly be called “a settled fact.” Various models had huge uncertainties, disagreed with one another, and could not predict the reentry location. But those inadequacies cannot be used as evidence for any absurd claim that it was going to stay in orbit. Anyone taking that position would be guilty of the same logical fallacy (called “impossible expectations”) that Koonin directs toward climate science.

Unpacking the ‘strawman’ argument

Another example of a strawman argument in “Unsettled” is the claim that the term “climate change denial” is intended to invoke Holocaust denial, an assertion that triggers strong emotions. Koonin says, “I find it particularly abhorrent to have a call for open scientific discussion equated with Holocaust denial, especially since the Nazis killed more than two hundred of my relatives in Eastern Europe.” I do not doubt the sincerity of his anger, but it is misdirected.

First, it’s aimed at a strawman. Climate change deniers are (by definition) not asking for open scientific discussion. The term “denier” is reserved for those who simply deny.

Second, there is no evidence that the term “climate change denial” is intended to invoke Holocaust denial. Ironically, this connection was first made by the late Hollywood screenwriter Michael Crichton, speaking at a 2003 lecture at Caltech, where Koonin was provost. The word “denier” literally means “one that denies” and the term has been used this way since the 1400s. The term Holocaust denier didn’t come into widespread use until the 1980s. By the early 1990s “denier” was independently being used to describe those who deny the science of climate change.

Third, it is climate scientists, not deniers, who have been compared to Nazis and perpetrators of genocide. In fact it was Crichton himself, in the appendix to his 2004 book “State of Fear,” who directly equated climate scientists to eugenicists who had a role in “killing of ten million undesirables.” Crichton also explicitly compared climate scientists to Trofim Lysenko, whose work he described as resulting in “famines that killed millions and purges that sent hundreds of dissenting Soviet scientists to the gulags or the firing squads.” Nevertheless, Koonin praises Crichton and cites “State of Fear” as evidence that he was an “outspoken advocate for scientific integrity” who “looked askance at the public presentation of climate science.”

Whether one thinks it is more abhorrent to be described by the same word as those who deny other things, including the Holocaust, or to be explicitly equated to those who carried out the Holocaust is a matter of personal opinion but may indicate unconscious bias.

More uncertainty amounts to more risk

Koonin’s bias became evident in the introduction by his use of biased language. Climate scientists “adjust model results to obfuscate shortcomings.” “Climate alarmism has come to dominate US politics.” By speaking openly about uncertainty, he had “inadvertently broken some code of silence, like the Mafia’s omerta .”

Koonin implies throughout the book that climate scientists have conspired to downplay uncertainty and exaggerate the risk, apparently unaware of the fact that increased uncertainty means increased risks. Nowhere does he mention that climate sensitivity is described in the scientific literature by a probability density function that is highly skewed, with a long high-sensitivity tail that we cannot discount with certainty. Risk is the integrated product of probability and consequences. It’s hard to argue that the consequences of climate change don’t get worse with sensitivity.

If a pilot isn’t sure about having enough fuel to get you to your destination, if an astronomer isn’t sure that an incoming asteroid will miss the Earth, if your doctor isn’t sure if you have a terminal disease, if you’re not sure you turned the stove off: In each of these cases, the uncertainty is unsettling. Why does Koonin think that unsettled questions in climate science are any kind of comfort when the consequences of doing nothing can be catastrophic? “Unsettled” should leave serious scientists feeling unsettled.

Readers would do well to see crankyuncle.com for information about logical fallacies used by climate change deniers.

Mark Boslough is a Fellow of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. He has served on the Executive Committee of the American Physical Society Topical Group on the Physics of Climate and created, convened, and for several years chaired American Geophysical Union sessions on “Uncertainty Quantification and its Application to Climate Change.”

May 13, 2021

A New Book Manages to Get Climate Science Badly Wrong

In Unsettled, Steven Koonin deploys that highly misleading label to falsely suggest that we don’t understand the risks well enough to take action

By Gary Yohe

Warren Faidley Getty Images

Steven Koonin, a former undersecretary for science of the Department of Energy in the Obama administration, but more recently considered for an advisory post to Scott Pruitt when he was administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, has published a new book. Released on May 4 and entitled Unsettled: What Climate Science Tells Us, What It Doesn’t, and Why It Matters, its major theme is that the science about the Earth’s climate is anything but settled. He argues that pundits and politicians and most of the population who feel otherwise are victims of what he has publicly called “ consensus science .”

Koonin is wrong on both counts. The science is stronger than ever around findings that speak to the likelihood and consequences of climate impacts, and has been growing stronger for decades. In the early days of research, the uncertainty was wide; but with each subsequent step that uncertainty has narrowed or become better understood. This is how science works, and in the case of climate, the early indications detected and attributed in the 1980s and 1990s, have come true, over and over again and sooner than anticipated.

This is not to say that uncertainty is being eliminated, but decision makers have become more comfortable dealing with the inevitable residuals. They are using the best and most honest science to inform prospective investments in abatement (reducing greenhouse gas emissions to diminish the estimated likelihoods of dangerous climate change impacts) and adaptation (reducing vulnerabilities to diminish their current and projected consequences).

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Koonin’s intervention into the debate about what to do about climate risks seems to be designed to subvert this progress in all respects by making distracting, irrelevant, misguided, misleading and unqualified statements about supposed uncertainties that he thinks scientists have buried under the rug. Here, I consider a few early statements in his own words. They are taken verbatim from his introductory pages so he must want the reader to see them as relevant take-home findings from the entire book. They are evaluated briefly in their proper context, supported by findings documented in the latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change . It is important to note that Koonin recognizes this source in his discussion of assessments, and even covers the foundations of the confidence and likelihood language embedded in its findings (specific references from the IPCC report are presented in brackets).

Two such statements by Koonin followed the simple preamble “For example, both the literature and government reports that summarize and assess the state of climate science say clearly that…”:

“Heat waves in the US are now no more common than they were in 1900, and that the warmest temperatures in the US have not risen in the past fifty years.” (Italics in the original.) This is a questionable statement depending on the definition of “heat wave”, and so it is really uninformative. Heat waves are poor indicators of heat stress. Whether or not they are becoming more frequent, they have clearly become hotter and longer over the past few decades while populations have grown more vulnerable in large measure because they are, on average, older [Section 19.6.2.1]. Moreover, during these longer extreme heat events, it is nighttime temperatures that are increasing most. As a result, people never get relief from insufferable heat and more of them are at risk of dying .

“The warmest temperatures in the US have not risen in the past fifty years.” According to what measure? Highest annual global averages? Absolutely not. That the planet is has warmed since the industrial revolution is unequivocal with more than 30 percent of that warming having occurred over the last 25 years, and the hottest annual temperatures in that history have followed suit [Section SPM.1].

Here are a few more statements from Koonin’s first two pages under the introduction that “Here are three more that might surprise you, drawn from recently published research or the latest assessments of climate science published by the US government and the UN”:

“Greenland’s ice sheet isn’t shrinking any more rapidly today than it was eighty years ago.” For a risk-based approach to climate discussions about what we “should do,” this statement is irrelevant. It is the future that worries us. Observations from 11 satellite missions monitoring the Arctic and Antarctic show that ice sheets are losing mass six times faster than they were in the 1990s. Is this the beginning of a new trend? Perhaps. The settled state of the science for those who have adopted a risk management approach is that this is a high-risk possibility (huge consequences) that should be taken seriously and examined more completely. This is even more important because, even without those contributions to the historical trend that is accelerating, rising sea levels will continue to exaggerate coastal exposure by dramatically shrinking the return times of all variety of storms [Section 19.6.2.1]; that is, 1-in-100 year storms become 1-in-50 year events, and 1-in-50 year storms become 1-in-10 year events and eventually nearly annual facts of life.

“The net economic impact of human-induced climate change will be minimal through at least the end of this century.” It is unconscionable to make a statement like this, and not just because the adjective “minimal” is not at all informative. It is unsupportable without qualification because aggregate estimates are so woefully incomplete [Section 19.6.3.5]. Nonetheless, Swiss Re recently released a big report on climate change saying that insurance companies are underinsuring against rising climate risks that are rising now and projected to continue to do so over the near term. Despite the uncertainty, they see an imminent source of risk, and are not waiting until projections of the end of the century clear up to respond.

The first of these misdirection statements about Greenland is even more troubling because the rise in global mean sea level has accelerated. This is widely known despite claims to the contrary in Chapter 8 which is described in the introduction as a “levelheaded look at sea levels, which have been rising over the past many millennia.” Koonin continues: “We’ll untangle what we really know about human influences on the current rate of rise (about one foot per century) and explain why it’s very hard to believe that surging seas will drown the coasts any time soon.”

The trouble is that while seas have risen eight to nine inches since 1880, more than 30 percent of that increase has occurred during the last two decades: 30 percent of the historical record over the past 14 percent of the time series. This is why rising sea levels are expected with very high confidence to exaggerate coastal exposure and economic consequences [Section 19.6.2.1].

His teaser for Chapter 7 is an equally troubling misdirection. He promises to highlight “some points likely to surprise anyone who follows the news—for instance, that the global area burned by fires each year has declined by 25 percent since observations began in 1998.” Global statistics are meaningless in this context. Wildfires (if that is what he is talking about) are local events whose regional patterns of intensity and frequency fit well into risk-based calibrations because they are increasing in many locations. Take, for example, the 2020 experience. Record wildfires were seen across the western United States, Siberia, Indonesia and Australia (extending from 2019) to name a few major locations.

Take a more specific example. From August through October of 2020, California suffered through what became the largest wildfire in California history. It was accompanied by the third, fourth, fifth and sixth largest conflagrations in the state’s history ; and all five of them were still burning on October 3. Their incredible intensity and coincidence can only be explained by the confluence of four climate change consequences that have been attributed to climate changes so far: record numbers of nighttime dry lightning strikes during a long and record-setting drought, a record-setting heat wave extending from July through August, a decade of bark-beetle infestation that killed 85 percent of the trees across enormous tracks of forests, and long-term warming that has extended the fire season by 75 days.

So, what is the takeaway message? Regardless of what Koonin has written in his new book, the science is clear, and the consensus is incredibly wide. Scientists are generating and reporting data with more and more specificity about climate impacts and surrounding uncertainties all the time. This is particularly true with regard to the exaggerated natural, social and economic risks associated with climate extremes—the low-probability, high-consequence events that are such a vital part of effective risk management. This is not an unsettled state of affairs. It is living inside a moving picture of what is happening portrayed with sharper clarity and more detail with every new peer-reviewed paper.

The author benefited from conversations with Henry Jacoby, Richard Richel and Benjamin Santer in preparing this essay.

This is an opinion and analysis article.

- Home Design Experts

- Senior Living

- Wedding Experts

- Real Estate Agents

- Private Schools

- Mortgage Professionals

- 50 Best Restaurants

- Restaurant Finder

- Be Well Philly

- Find a Dentist

- Find a Doctor

- Life & Style

- Properties & News

- Find a Home & Design Pro

- Find a Real Estate Agent

- Find a Mortgage Professional

- Events in Philly

- Philly Mag Events

- Guides & Advice

- Find a Wedding Expert

- Bubbly Brunch Event

- Best of Philly

- Newsletters

If you're a human and see this, please ignore it. If you're a scraper, please click the link below :-) Note that clicking the link below will block access to this site for 24 hours.

Ten Years After Oprah Book Pick, Philly’s Ayana Mathis Is Back

The early reviews are stellar for The Unsettled , which was partly inspired by the MOVE bombing.

Get a compelling long read and must-have lifestyle tips in your inbox every Sunday morning — great with coffee!

Ayana Mathis / Photograph by Linette & Kyle Kielinski

In 2012, Germantown native Ayana Mathis suddenly found herself thrust into the spotlight when Oprah Winfrey singled out her debut novel for the famous book club. It’s taken a while, but Mathis just released her second novel , another work of historical Black fiction. Here, she talks about the MOVE bombing’s influence on the book, growing up poor, and the one thing from Philly she wishes she could import to New York City. We spoke with her on September 27th.

Good afternoon, Ayana. Hi, Victor. What’s happening in Philly?

Interesting you should ask. Last night was a bit chaotic. Dozens of arrests for looting in Center City. On the other hand, the Phillies clinched a playoff berth. [ Laughs ] I shouldn’t be laughing. But that is just so very Philly. Such a city of contradictions.

Indeed. Congratulations on the release of your second novel, The Unsettled . What does one do on the day of one’s major book release? One paces around one’s apartment anxiously. [ laughs ]

I’m assuming that like most creative types I know who live in New York, you live in Brooklyn. I do not! Ha! Sorry that I can’t perpetuate that for you. I used to live in Brooklyn; I’ve been in Washington Heights for seven years.

I’m not sure I’ve ever been to Washington Heights. It’s the northern part of Manhattan. I’m on 180th Street, and the island ends at 220th Street. It reminds me of a New York that used to be. Just regular people and families, as opposed to the super-cool and the super-hip. It’s a real neighborhood. I mean, we still have a shoe-repair place! But I’m also right by the A train, so I’m only 25 minutes from Midtown.

Why did New York pull you away from us? After graduating from Girls’ High, I went to NYU. I had what I would call a “varied” undergraduate career. After a year at NYU, I wound up with my mom back in Philly, because I was in an accident and needed to heal. Then I wound up at Temple, where I had the amazing fortune to study with the renowned poet Sonia Sanchez. And then back to New York again for more college. And then I just wound up staying here.

My students have big questions and strong opinions about why we are reading what we’re reading. But, I ask them, what is the point of completely erasing something? Why not debate it and loudly critique it as intelligent, thinking people? Just simply erasing things, as many people are doing, is a very big problem.” — Ayana Mathis

Do you still consider yourself a Philadelphian? I do. When people ask me what my core identity is, all of these things come to mind, but, basically, I am a poor Black girl from Philly. That’s who I understand myself to be.

How poor are we talking? Very. We had lots of housing instability. I grew up in Germantown and Mount Airy and, for a bit, on City Line Avenue in Wynnefield. But mostly in Germantown.

Without giving away too much of your book, MOVE and the bombing of MOVE provide major inspiration for some of the characters and part of the plotline. What was your experience with MOVE as a kid in Philly? There was so much mystery surrounding MOVE. I was 11 when the bombing happened, and I saw what I saw on TV. But in my family, we just didn’t talk about it. I knew that there was something very wrong and that something fundamentally bad had happened. But in my house, there were just certain kinds of discussions that weren’t really had. Was it similar for you?

Yes. I remember watching it on TV. It was this horrible spectacle that nobody discussed. I didn’t really “get” it. I carried it around as a wound, and it wasn’t until I was much older and in college, taking African American studies and reading African American literature and writings about protest movements, that I was really able to interrogate the dynamics of that time and to be able to talk about MOVE in a coherent way.

Only serious hardliners think there was any cause for Philly to bomb its own citizens. That said, a lot of people are quick to point out that MOVE was a terrible neighbor. There were guns in the compound and other factors involved. How does history judge MOVE and the actions of the city? That’s a big and complicated question. I should say, for the record, that my book is not about MOVE. MOVE is an inspiration for things that happen in my book. But yes, it is 100 percent the case that the police should not have done what they did, and it was also the case that MOVE were bad neighbors. The question becomes: In a civil society, what do we do when neighbors have legitimate complaints about a neighbor? Certainly, the response is not that we bomb the bad neighbor. Was MOVE a menace? Yes. But being a menace doesn’t mean you should be murdered.

MOVE also had perfectly valid points about the “system” and Black autonomy. What do we do with people who decide to live outside the system as separatists? And what are the challenges those people face from within and without? MOVE should inspire in us mourning, outrage, and a whole lot of questions about how the state and the powers that be meet Black people — or any other people — who want to live differently.

Some of the Philly authors I’ve interviewed publish a book a year. Your first novel, The Twelve Tribes of Hattie , came out 11 years ago, to great acclaim. Did you take a long break after Hattie ? Or did you just take it slowly? I did take my time, that’s for sure. But I didn’t intentionally take a break. Hattie was such an intense whirlwind, mostly because Oprah chose it for her book club. So after it came out, I was touring off and on for two years, all around the world. The whole experience was so loud and shocking that it required a recalibration of my self — my relationship to writing and to my privacy. And then once I was ready, yes, there was a lot of: I like this sentence, I don’t like this sentence, this character works, this character doesn’t. The Unsettled was also just a very difficult book to write, very different from Hattie . It required an entirely different set of tools and style of narration. It was a recalcitrant book that took a long time to gel and become itself.

And are you wholly satisfied with the results, or did there come a point where your publisher said, “Okay, enough. You need to turn this in”? I was way past my deadline. This book was literally three or four years late. But thank God, my editor was like, “I just want it to be a good book, so when we’re done, we’re done.” I am happy with it. I think every book is always this idealized thing in your head, this shining jewel that exists in your mind, but you can never actually make or fully realize that thing. So is it the thing in my head? No. No, it is not. Nothing I write will ever be. But I am so proud of it.

So will I need to wait until 2034 for your third novel? My kids will be 27 and 28 by then, Ayana. You’ll be going to weddings!

Don’t say that. [ Laughs ] I know, right? In our very East Coast bubble, people get married in their 30s. Even though it’s a perfectly valid decision to marry in your mid-20s, it does seem strange these days to some of us. … But no, I don’t think it will be that long. A sophomore novel is notoriously difficult to write, and even more so when reception to the first novel was what it was for Hattie . I know nothing about what that third book will be, but I hope it doesn’t take that long, nor do I think it will.

How has the book industry changed since Hattie ? It’s changed so much. Things are so fragmented. Cultural information now comes from so many different sorts of sources, and it’s increasingly siloed, with the algorithm dictating what you find out about. So it will be interesting for me to see how this one rolls out.

Oprah Winfrey with Ayana Mathis at the O Magazine offices at the Hearst building in 2012. / Photograph via O, The Oprah Magazine /Rob Howard

You mentioned growing up poor. Then you write this novel that becomes part of Oprah’s Book Club and stays on best-seller lists for months. Did this have a big impact for you financially, or are you like some of my friends who have millions of Spotify streams but can’t pay their rent? It had a very intense economic impact on my life. Not as much as some people thought. When I was on tour, I would encounter people who thought I was a sudden millionaire. That was not at all the case. But the impact was certainly significant.

As for the sales of The Unsettled , clearly people are buying fewer books than they used to. Booksellers definitely sell fewer books, but even when Hattie came out, people were saying books and publishing were dead. But that’s not true. We see so many independent bookstores opening and thriving, and we see a lot of people out there on social media with huge followings advocating for books just because they love them.

I also recall when e-books were supposedly going to wipe out physical books. But that hasn’t happened by any means. My kids refuse to read books digitally. They want to hold actual paper in their hands. Yes, I think there may be a rebellion against digital from younger millennials and Gen Z. This is anecdotal, but it seems to me there’s a pushback from those people against their lives being hijacked by digitized everything. I see young people every day on the subway reading physical books, and it’s refreshing.

But at the same time, when I’m out to dinner in nice restaurants, I see so many parents sticking iPads in their kids’ hands and headphones in their ears during dinner. I know! Parents are going to ruin everything. [ laughs ]

I find that there are two types of artists — those who never read reviews, and those who claim they don’t but secretly do. Which are you? I totally read the reviews. Can’t help it. I also write book reviews for the New York Times , and I find reviews to be a really interesting form of writing. Actually, as we sit here right now, I am anxiously awaiting the Washington Post ’s review of Unsettled . That said, I don’t pay attention to the reviews on Goodreads or Amazon. That’s just too much, too overwhelming.

Both of your novels heavily incorporate Black history. But neither includes more modern Black history, like the history since you became an adult. Do you ever see yourself incorporating, say, Black Lives Matter or the murder of George Floyd? I write historical novels, but it’s really kind of impossible for me to write a novel where I have to contend with social media or cell phones, so I want to stop everything by 1990. So many things that happened back then can’t happen now thanks to cell phones — or at least, they would happen very differently. I am very analog, at least when it comes to my fiction.

Ayana Mathis, author of the new book The Unsettled , speaking at the Literacy Partners 2023 Gala in New York (Getty Images)

You write book reviews. I occasionally step into the fray of cultural reviews in my writing. But I was just involved in a social media fracas where a bunch of people — people younger than me — were arguing that professional critique has no place in society today. What’s your read on that? There is a generational difference here. There’s some justifiable distrust there in the sense that for years, there were gatekeepers who would decide what would get in and what wouldn’t, and these gatekeepers weren’t representative of the community. We’re also now a ratings culture, where everybody wants to say who has the best french fries, and thanks to all the apps, they can do that. This chips away at professional reviewing. But I am hoping that as the gatekeepers change, which is happening slowly, there will be more respect for critique.

Back to Girls’ High. So many women I’ve talked to have raved about their experiences at Girls’ High. The one that stands out the most is Gloria Allred, who said she wouldn’t be who she was without Girls’ High. Actually, I’ve never heard one bad thing about Girls’ High, which seems weird. What was your experience? I’m sorry, but I’m not going to disrupt the narrative. [ laughs ] It was great. Girls’ High was a haven for me at a time when my life outside of school was tumultuous. When I was there in the late ’80s, there was a real inattentiveness in society to the feminist issues playing out in classrooms. In 1987, nobody was thinking about the fact that the boys were always the ones who spoke out the loudest and who were allowed to speak for the longest. But at Girls’ High, the people to speak the loudest and longest were all girls. The sports stars were all girls. Those four years really changed my sense of self and my confidence.

I know you teach at Hunter College. So much has been said lately about free speech and academic freedom on campus. Buzz Bissinger not long ago revealed to me that he refuses to teach his biggest work in his writing course at Penn after a student raised holy hell because he used the N-word in it. Do you find the current academic environment limiting? I’m very lucky. My students have big questions and strong opinions about why we are reading what we’re reading. But, I ask them, what is the point of completely erasing something? Why not debate it and loudly critique it, as intelligent, thinking people? Just simply erasing things, as many people are doing, is a very big problem.

We’re out of time, and I feel my editor staring at me and saying, “Make her say more about Philly!” After all, this is Philly Mag. So for this final question, I want to know what one thing from Philadelphia you wish you could import to New York. Wider streets! And the fierce honesty and authenticity that you get from Philadelphians. But really, if you make me pick one thing, it would have to be the Reading Terminal Market, which I look forward to visiting again soon. A brisket sandwich with broccoli rabe and sharp provolone from DiNic’s is the thing I long most for.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Published as “A Writer’s Return” in the November 2023 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

- MOVE Bombing

- On the Record

Your Guide to the 2023 Eagles Season

Everything You Need to Know Before the 76ers Enter the NBA Playoffs

A 2023 User’s Manual to Dating Apps

20 Years After the Vet: A Remembrance of Philly’s Storied Stadium

John bolaris claims return to tv while trashing his ex-girlfriend, who killed the philly pops, artificial intelligence expert: we’re all going to die, philadelphia had more exonerations last year than 46 states, in this section.

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

THE UNSETTLED

by Ayana Mathis ‧ RELEASE DATE: Sept. 26, 2023

An affecting and carefully drawn story of a family on the brink.

A family’s struggles in Philadelphia are echoed in turmoil in its ancestral Alabama.

Mathis’ follow-up to her brilliant debut, the novel-in-stories The Twelve Tribes of Hattie (2013), concerns three generations of one Black family. In 1985, Ava Carson has escaped her abusive husband, Abemi Reed, but is left homeless and jobless; the shelter that accepts her and her young son, Toussaint, is roach-infested, and lingering trauma interferes with her ability to get her life in order. Toussaint, meanwhile, plays truant and becomes enmeshed in the neighborhood’s street life. Mathis alternates Ava and Toussaint’s ongoing plight with a storyline narrated by Ava’s mother, Dutchess, a one-time traveling blues singer. She’s one of the last residents of an Alabama town, Bonaparte, which is slowly becoming overrun, at times violently, by encroaching white developers from the ironically named Progress Corp., which “pulled it up like a weed and threw it facedown in the dirt.” A glimmer of hope appears with the re-emergence of Toussaint’s father, Cassius Wright, a doctor and former Black Panther who’s trying to launch a much-needed (if technically illegal) neighborhood health clinic and strictly run commune. But order proves slippery, and the novel’s very structure implies that Black families separated by distance and broken by (mainly white) policing and development become nearly impossible to sustain. Mathis’ themes, and sometimes her prose, echo Their Eyes Were Watching God and Sula , two similarly lyrical stories rooted in place and relationships. Though this novel doesn’t enter their ranks, Mathis powerfully evokes the heartbreak and ways best efforts are undermined by social and legal machinery. A determination among all three characters defines the story—Dutchess, Ava, and Toussaint are inheritors of abuse, but Mathis makes them objects of indomitability, not pity.

Pub Date: Sept. 26, 2023

ISBN: 9780525519935

Page Count: 336

Publisher: Knopf

Review Posted Online: July 15, 2023

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Aug. 15, 2023

FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP

Share your opinion of this book

More by Ayana Mathis

BOOK REVIEW

by Ayana Mathis

More About This Book

PERSPECTIVES

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

New York Times Bestseller

by Kristin Hannah ‧ RELEASE DATE: Feb. 6, 2024

A dramatic, vividly detailed reconstruction of a little-known aspect of the Vietnam War.

A young woman’s experience as a nurse in Vietnam casts a deep shadow over her life.

When we learn that the farewell party in the opening scene is for Frances “Frankie” McGrath’s older brother—“a golden boy, a wild child who could make the hardest heart soften”—who is leaving to serve in Vietnam in 1966, we feel pretty certain that poor Finley McGrath is marked for death. Still, it’s a surprise when the fateful doorbell rings less than 20 pages later. His death inspires his sister to enlist as an Army nurse, and this turn of events is just the beginning of a roller coaster of a plot that’s impressive and engrossing if at times a bit formulaic. Hannah renders the experiences of the young women who served in Vietnam in all-encompassing detail. The first half of the book, set in gore-drenched hospital wards, mildewed dorm rooms, and boozy officers’ clubs, is an exciting read, tracking the transformation of virginal, uptight Frankie into a crack surgical nurse and woman of the world. Her tensely platonic romance with a married surgeon ends when his broken, unbreathing body is airlifted out by helicopter; she throws her pent-up passion into a wild affair with a soldier who happens to be her dead brother’s best friend. In the second part of the book, after the war, Frankie seems to experience every possible bad break. A drawback of the story is that none of the secondary characters in her life are fully three-dimensional: Her dismissive, chauvinistic father and tight-lipped, pill-popping mother, her fellow nurses, and her various love interests are more plot devices than people. You’ll wish you could have gone to Vegas and placed a bet on the ending—while it’s against all the odds, you’ll see it coming from a mile away.

Pub Date: Feb. 6, 2024

ISBN: 9781250178633

Page Count: 480

Publisher: St. Martin's

Review Posted Online: Nov. 4, 2023

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Dec. 1, 2023

FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP | GENERAL FICTION | HISTORICAL FICTION

More by Kristin Hannah

by Kristin Hannah

BOOK TO SCREEN

Kirkus Reviews' Best Books Of 2023

THE FIVE-STAR WEEKEND

by Elin Hilderbrand ‧ RELEASE DATE: June 13, 2023

The people in her books may screw up, but Hilderbrand always gets it right. Kind of amazing.

A dreamy Nantucket house party given by a meticulous hostess goes off the rails.

“When Hollis posts a potato and white cheddar tart with a crispy bacon crust, her foodie community breaks the one-million-member milestone. (Leave it to bacon!)” And leave it to Hilderbrand, in her 30th book of Nantucket-based fiction, to cook up more literary bacon, this time focusing on female friendship, female “friendship,” and the power of the internet and social media. When Hollis Shaw's doctor husband dies in a crash on the way to the airport, she steps back from Hungry With Hollis, her popular website. After moping around her house in “Swellesley” for a while, she returns to Nantucket for the summer, planning a kick-out-the-stops weekend party that will involve one girlfriend from each phase of her life—youth, college, motherhood—plus her favorite internet follower, an Atlanta-based airline pilot, whom she's never actually met. Two of these old pals are definitely not as close to Hollis as they once were, one of them has done her secret harm, and Hollis dramatically increases the potential for trouble by paying her angry 20-something daughter to document the weekend on film. Add two bottles each of Casa Dragones tequila, Triple 8 vodka, and Veuve Clicquot, plus some Hendricks gin and Mount Gay rum—what could possibly go wrong? Known for gently inserting social commentary into her plots, Hilderbrand here highlights the ridiculous fickleness of cancel culture when one of the characters—Dru-Ann, an extremely successful Black sports agent—almost loses her clients, her job, and her boyfriend when a video clip of a private conversation in a restaurant is posted on social media. Everyone says there's no way forward without a self-effacing apology. Dru-Ann says pass the Casa Dragones. Meanwhile, Hollis is about to learn that friendships forged on the internet are not always what they seem. Hilderbrand has announced plans to retire in 2024. Wait—that's next year! No!

Pub Date: June 13, 2023

ISBN: 9780316258777

Page Count: 384

Publisher: Little, Brown

Review Posted Online: Feb. 7, 2023

Kirkus Reviews Issue: March 1, 2023

FAMILY LIFE & FRIENDSHIP | GENERAL FICTION

More by Elin Hilderbrand

by Elin Hilderbrand

SEEN & HEARD

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

- Book Reviews

- LSE Comment

- Phelan US Centre

- Email updates

August 15th, 2021

Book review: unsettled: what climate science tells us, what it doesn’t, and why it matters by steve koonin.

9 comments | 16 shares

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

In Unsettled: What Climate Science Tells Us, What It Doesn’t, and Why It Matters , Steve Koonin sets out his scepticism about the science of climate change, arguing that increasing global temperatures could be down to natural variability rather than human activities. Bob Ward finds that the book is not a robust guide to the subject and is based on a number of inaccurate and misleading claims, flawed studies, and cherrypicked information.

A new book, ‘Unsettled: What Climate Science Tells Us, What It Doesn’t, and Why It Matters’ has been seized upon by American opponents of climate change action. But climate scientists have condemned it as little more than propaganda.

The author, Professor Steve Koonin , trained as a theoretical physicist and left his job as chief scientist at BP to take up the role of Under Secretary for Science in the US Department of Energy in May 2009. He left the Obama Administration in November 2011 and became Director of the Center for Urban Science and Progress at New York University. Shortly afterwards he started to publicly express his scepticism about the science of climate change, particularly through a long article under the headline ‘Climate Science Is Not Settled’ in ‘The Wall Street Journal’ in September 2014.

As Koonin admits in the introduction, his book is an updated and extended version of his newspaper article. Some of the early chapters are interesting and informative on how greenhouse gas concentrations and global temperature have changed. But most of the book is drenched in the author’s sense of self-importance, with Professor Koonin clearly believing that the global community of climate scientists are hiding some important facts and he alone speaks the truth.

For instance, in the introduction, he writes: “As a scientist, I felt the scientific community was letting the public down by not telling the whole truth plainly. And as a citizen, I was concerned that the public and political debates were being misinformed. So I began to speak out…It seems that by highlighting those uncertainties so plainly and publicly, I had inadvertently broken some code of silence, like the Mafia’s omerta.”

Professor Koonin argues that many of the consequences that have been attributed to the undeniable rise in atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, including the rise in global mean surface temperature, could be due instead to natural variability. He alleges that climate science is “broken”, and argues that human society should focus on adapting to the potential impacts of climate change instead of seeking to prevent them by ending annual emissions of greenhouse gases.

The author recommends that readers act warily by “checking up on what you’ve read in the media by looking at the primary research cited”. This is good advice. Fact-checking Professor Koonin’s claims leads the reader to realise how he has cherrypicked and carelessly misrepresented many of his sources.

For instance, in one chapter on “Tempest Terrors”, Professor Koonin attacks media coverage of the link between climate change and tropical cyclone activity, alleging that it “continues to promulgate unsupported alarm”. He cites a journal paper on ‘ Global increase in major tropical cyclone exceedance probability over the past four decades ’, and refers to a report on it in the newspaper ‘USA Today’, which summarised the conclusions as: “Human-caused global warming has strengthened the wind speeds of hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones around the globe”.

Photo by Mika Baumeister on Unsplash

To justify his complaint, Professor Koonin draws attention to the following quote from the final paragraph of the journal paper: “Ultimately, there are many factors that contribute to the characteristics and observed changes in TC [tropical cyclone] intensity, and this work makes no attempt to formally disentangle all of these factors. In particular, the significant trends identified in this empirical study do not constitute a traditional formal detection, and cannot precisely quantify the contribution from anthropogenic factors.”

However, Professor Koonin omits the sentence that followed: “From a storyline, balance-of-evidence, or Type-II error avoidance perspective, the consistency of the trends identified here with expectations based on physical understanding and greenhouse warming simulations increases confidence that TCs have become substantially stronger, and that there is a likely human fingerprint on this increase.”

Similarly, Professor Koonin complains about the following statement from a speech in September 2015 by the then Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney: “Despite winter 2014 being England’s wettest since the time of King George III; forecasts suggest we can expect at least a further 10% increase in rainfall during future winters.”

Professor Koonin writes: “To support that assertion, he cited Britain’s Met Office ‘research into climate observations, projections, and impacts.’ These were model forecasts for the next five years, so you might expect they’d be more accurate than those attempting to project climate fifty years out”. He concludes that “the Met Office models Carney cited back in 2014 all turned out to be dead wrong”. This was simply false. Mr Carney was referring accurately to projections for the 2080s , not over the next five years.

The inaccurate and misleading claims in the book are not limited to the science and include the economics of climate change. For instance, Professor Koonin states that “many analyses suggest that a warming of less than 2ºC is likely to have a small net positive economic impact, thanks to improved agricultural conditions and reduced heating costs in the temperate northern latitudes”. But he cites a flawed study that actually found just a single outlier paper suggesting net positive economic impacts from a warming of less than 2°C.

Overall, ‘Unsettled’ is a perfect embodiment of the strategy recommended in a cynical memo by pollster Frank Luntz to Republican activists during the Presidency of George W. Bush: “Should the public come to believe that the scientific issues are settled, their views about global warming will change accordingly. Therefore, you need to continue to make the lack of scientific certainty a primary issue in the debate”.

Predictably, Professor Koonin’s unreliable account of the facts about climate change has been panned by many researchers . Equally predictably, the book has received glowing reviews from conservative climate change deniers in the United States and abroad. Professor Koonin has accepted an invitation to follow in the footsteps of other male “experts”, such as Cardinal George Pell and former Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott, by delivering the annual lecture for the Global Warming Policy Foundation , the UK lobby group.

However, the publication in August 2021 of a new assessment of the science by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the world’s most authoritative source on the subject, shows very clearly that Professor Koonin’s book is not a robust guide to the subject.

Please read our comments policy before commenting .

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3iKMJet

About the reviewer

Bob Ward – LSE Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment Bob Ward is policy and communications director at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

About the author

RE: Book Review: Unsettled: What Climate Science Tells Us, What It Doesn’t, and Why It Matters by Steve Koonin

Hello Could you please explain why in the above article there is a pejorative reference to “male experts” regarding climate- on what scientific basis do you propose that one’s expertise on a matter is reduced through possessing male gender? I have shared your articles with friends, family and work colleagues and the response to poor journalism has not been favourable. I look forward to your reply. Sincerely. Doug McIntyre

I’m reading Koonin’s book now, and some of the criticisms in this and other reviews did ring alarms, indeed. This particular review was doing a fine job until the “…other male experts” jab, sadly destroying the whole apparent legitimacy of the review. The last thing we need in this already tensely debated topic is the interference of wokism to judge a scientist credibility. In all fairness I can’t share this otherwise useful review due to this unnecessary flaw, disclosing the biased motivation of the writer.

Two points. The first is, there is no reference to 2080’s as a projection date in Mark Carney’s speech that I could find. What page is it on? Secondly, Mark Carney did say that sea levels at The Battery, New York have risen 8 inches over the last 71 years. Really? Where did he get that figure from? Maybe I should read Professor Koonin’s book..

to Roger Bellamy

You claim “there is no reference to 2080’s as a projection date in Mark Carney’s speech that I could find. What page is it on?”

If you follow footnote 14 (page 7 of his speech) you will find the Met Office paper, with 10% additional UK rainfall projections to 2100 included in it (on pages 66 – 67), which matches Mark Carney’s comments in the speech. The link, in the speech, to the Met Office paper seems to be broken currently, but I did a google search to find the relevant Met Office paper. The paper can be found independently at:

https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/binaries/content/assets/metofficegovuk/pdf/research/climate-science/climate-observations-projections-and-impacts/uk.pdf

You describe Koonin as “trained” in theoretical physics. He was a professor of physics at Cal Tech, and then provost there.

Yet Steven Koonin quotes the IPCC many times in his 2021 GWPF lecture.

Roger Pielke, Jr., Professor of Environmental Studies at the University of Colorado and Distinguished Fellow of Japan’s Institute of Energy Economics – does not argue against anthropogenic effects on climate but does argue that dramatic climate events like hurricanes and floods have not changed significantly in frequency or intensity since the early 20thC. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uFOzhXxVSxA

Manhattan is actually sinking due to the extraordinary vertical masses built upon the mantle there. It is not a place of certainty in terms of ocean levels. The data using Manhattan therefore of ocean levels means nothing.

I’ve now bought Prof Koonin’s book. I was hoping he’d read enough of the papers that I wouldn’t have to. It seems that this may be a forlorn hope.

Is there any hope that he, Willie Soons, James Hansen and Michael Mann would ever get together and debate the matter in public or would it just collapse into acrimony? Two are more sceptical a) that it’s all man-made b) that we can do anything ‘world-changing’ about it.

To be fair, scientists worth their salt don’t get acrimonious in a public forum. They usually speak in barely-disguised code if they think someone else’s methodology was flawed, whether accidentally (incompetent) or deliberately (worse).

I have a colleague, not a ‘full’ scientist, who seems to have latched onto Hansen as a ‘trusted source’. However, Hansen is conveying a far more alarmist message than Soons or Koonin.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Related Posts

Book Review: The Covid Consensus: The New Politics of Global Inequality by Toby Green

February 20th, 2022.

Book Review: The Public and their Platforms: Public Sociology in an Era of Social Media by Mark Carrigan and Lambros Fatsis

July 25th, 2021.

Book Review: There is Nothing for You Here: Finding Opportunity in the Twenty-First Century by Fiona Hill

July 10th, 2022.

Book Review: Being Property Once Myself: Blackness and the End of Man by Joshua Bennett

January 17th, 2021.

Latest LSE Events podcasts

- The search for democracy in the world's largest democracy March 26, 2024

- The trading game March 21, 2024

- Who's afraid of gender? March 20, 2024

- The politics and philosophy of AI March 19, 2024

- Digital cities for humans or for profit? March 18, 2024

- Recasting the global economy and international institutions: collaboration, competition, and the new growth story March 14, 2024

- Look again: the power of noticing what was always there March 13, 2024

- A new growth story: structural transformation; policies and institutions March 13, 2024

- A world re-drawn; a world in crisis; a moment in history; the agenda for growth and transformation March 12, 2024

- Building prosperity through social solidarity and economic dynamism March 12, 2024

Authors & Events

Recommendations

- New & Noteworthy

- Bestsellers

- Popular Series

- The Must-Read Books of 2023

- Popular Books in Spanish

- Coming Soon

- Literary Fiction

- Mystery & Thriller

- Science Fiction

- Spanish Language Fiction

- Biographies & Memoirs

- Spanish Language Nonfiction

- Dark Star Trilogy

- Ramses the Damned

- Penguin Classics

- Award Winners

- The Parenting Book Guide

- Books to Read Before Bed

- Books for Middle Graders

- Trending Series

- Magic Tree House

- The Last Kids on Earth

- Planet Omar

- Beloved Characters

- The World of Eric Carle

- Llama Llama

- Junie B. Jones

- Peter Rabbit

- Board Books

- Picture Books

- Guided Reading Levels

- Middle Grade

- Activity Books

- Trending This Week

- Top Must-Read Romances

- Page-Turning Series To Start Now

- Books to Cope With Anxiety

- Short Reads

- Anti-Racist Resources

- Staff Picks

- Memoir & Fiction

- Features & Interviews

- Emma Brodie Interview

- James Ellroy Interview

- Nicola Yoon Interview

- Qian Julie Wang Interview

- Deepak Chopra Essay

- How Can I Get Published?

- For Book Clubs

- Reese's Book Club

- Oprah’s Book Club

- happy place " data-category="popular" data-location="header">Guide: Happy Place

- the last white man " data-category="popular" data-location="header">Guide: The Last White Man

- Authors & Events >

- Our Authors

- Michelle Obama

- Zadie Smith

- Emily Henry

- Amor Towles

- Colson Whitehead

- In Their Own Words

- Qian Julie Wang

- Patrick Radden Keefe

- Phoebe Robinson

- Emma Brodie

- Ta-Nehisi Coates

- Laura Hankin

- Recommendations >

- 21 Books To Help You Learn Something New

- The Books That Inspired "Saltburn"

- Insightful Therapy Books To Read This Year

- Historical Fiction With Female Protagonists

- Best Thrillers of All Time

- Manga and Graphic Novels

- happy place " data-category="recommendations" data-location="header">Start Reading Happy Place

- How to Make Reading a Habit with James Clear

- Why Reading Is Good for Your Health

- 10 Facts About Taylor Swift

- New Releases

- Memoirs Read by the Author

- Our Most Soothing Narrators

- Press Play for Inspiration

- Audiobooks You Just Can't Pause

- Listen With the Whole Family

Reading Guide

Look Inside | Reading Guide

The Unsettled

By ayana mathis on tour, by ayana mathis on tour read by bahni turpin, category: fiction, category: literary fiction, category: literary fiction | audiobooks.

Jun 04, 2024 | ISBN 9780525435617 | 5-3/16 x 8 --> | ISBN 9780525435617 -->

Oct 17, 2023 | ISBN 9780593793039 | 6-1/8 x 9-1/4 --> | ISBN 9780593793039 --> Buy

Sep 26, 2023 | ISBN 9780525519935 | 6-1/8 x 9-1/4 --> | ISBN 9780525519935 --> Buy

Sep 26, 2023 | ISBN 9780525519942 | ISBN 9780525519942 --> Buy

Sep 26, 2023 | 687 Minutes | ISBN 9780593788424 --> Buy

Buy from Other Retailers:

Preorder from:

Jun 04, 2024 | ISBN 9780525435617

Oct 17, 2023 | ISBN 9780593793039

Sep 26, 2023 | ISBN 9780525519935

Sep 26, 2023 | ISBN 9780525519942

Sep 26, 2023 | ISBN 9780593788424

687 Minutes

Buy the Audiobook Download:

- audiobooks.com

About The Unsettled

A NEW YORK TIMES NOTABLE BOOK • A BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR • From the best-selling author of The Twelve Tribes of Hattie , a searing multi-generational novel—set in the 1980s in racially and politically turbulent Philadelphia and in the tiny town of Bonaparte, Alabama—about a mother fighting for her sanity and survival “Emotionally propulsive … Through a chorus of distinctive and virtuosic voices, we gather the story of a mother, a daughter, and the land that both unites and divides them.”– Oprah Daily • “Showcases Ayana Mathis’s grace on the page, as writer, as storyteller. A book to be read and re-read.” – Jesmyn Ward, author of Let Us Descend Two bold, utopic communities are at the heart of Ayana Mathis’s searing follow-up to her bestselling debut, The Twelve Tribes of Hattie . Bonaparte, Alabama – once 10,000 glorious Black-owned acres – is now a ghost town vanishing to depopulation, crooked developers, and an eerie mist closing in on its shoreline. Dutchess Carson, Bonaparte’s fiery, tough-talking protector, fights to keep its remaining one thousand acres in the hands of the last five residents. Meanwhile, in Philadelphia, her estranged daughter Ava is drawn into Ark – a seductive, radical group with a commitment to Black self-determination in the spirit of the Black Panthers and MOVE, with a dash of the Weather Underground’s violent zeal. Ava’s eleven-year-old son Toussaint wants out – his future awaits him on his grandmother’s land, where the sounds of cicada and frog song might save him if only he can make it there. In Mathis’s electrifying novel, Bonaparte is both mythic landscape and spiritual inheritance, and 1980s Philadelphia is its raw, darkly glittering counterpoint. The Unsettled is a spellbinding portrait of two fierce women reckoning with the steep cost of resistance: What legacy will we leave our children? Where can we be free?

Listen to a sample from The Unsettled

Also by ayana mathis.

About Ayana Mathis

AYANA MATHIS’s first novel, The Twelve Tribes of Hattie was a New York Times best seller, an NPR Best Book of 2013, the second selection for Oprah’s Book Club 2.0. and has been translated into sixteen languages. Her nonfiction has… More about Ayana Mathis

Product Details

You may also like.

The Lost Wife

The Bookshop of the Broken Hearted

Under the Tamarind Tree

Dreaming in Cuban

Woman of Light

The Last Lifeboat

The Flight Portfolio

Crook Manifesto