North American Cuisine Guides

- Recipes by World Cuisine

- Serious Eats

- World Cuisines

- North American

Explore North American Cuisines

More in world cuisines.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Student Editorial Contest Winner

Free World Cuisines & Food Culture Essay Examples & Topics

Food is one of the greatest pleasures humans have in life. It does more than just helping us sustain our bodies. It has the capacity to bring us back in time and across the borders. In this article, we will help you explore it in your essay about food and culture.

Food culture is the practices, beliefs, attitudes around the production, distribution, and consumption of food. Speaking about it, you can touch upon your local traditions or foreign cuisine. In essays, you can explore a variety of customs and habits related to food.

In this article, our experts have gathered tips on writing food culture essays. It will be easy for you to write an academic paper with them in mind. Moreover, you will find topics for your essay and will be able to see free samples written by other students. They are great to use for research or as guidelines.

Foreign Cuisine & Food Culture Essay Tips

Writing a cuisine essay is not much different from working on any other academic piece. And because of that, you need to apply the regular rules for writing, structuring, and formatting. As a student, you probably know them well now. However, it is not that easy to keep everything in mind, isn’t it? In this section, you’ll see what rules you need to follow when writing a food and culture essay.

- Follow a typical essay structure.

A. Start with an introduction. Its goal is to intrigue your audience and establish your topic. B. Add a thesis statement. It’s the main idea expressed in the last sentence of the introductory paragraph. C. The body is where you argue your thesis statement and present your arguments and examples. D. In your conclusion, summarize your arguments and restate your thesis. Bring the essay to a new level by creating an impression that stays with the reader.

- Do not skip brainstorming.

Gathering different ideas is one of the first steps of essay writing. Collect as many thoughts and arguments as possible. Later, in your research phase, you can develop only the best ones. Write at least ten different ideas, and then choose the one that interests you the most.

- Choose a win-win essay topic.

Food is a necessity; however, it is way more than that. We associate food with the most memorable moments of our life. Choosing a topic that demonstrates this connection is not an easy task. The issue needs to be well developed but narrow at the same time. Most importantly, try to write about something you are genuinely passionate about and have a formed opinion on.

- Write for your audience.

Knowing your audience can help you decide what topic to pick and even what information to include in your paper. It also influences the tone, the voice, and the arguments you use. Consider your audience’s needs and academic background. It will help you determine your paper’s terminology, examples, and theoretical framework.

- Keep your topic in mind.

After you formulate your topic, it is time to dig into numerous sources. You can start by going to your school library and searching on the Internet. Consider visiting some ethnic restaurants in your area to get a first-hand experience of food culture. Every time you find new sources, ask yourself if this information necessary for your topic. Throughout this process, take notes. Write down precise numbers, dates, locations, names. All this data will help you greatly to write a cuisine essay in one sit.

- Write an outline.

Once your research is done, and you’ve determined the correct format for your food and culture essay, outline your work. You won’t lose track of the essential points and examples when you have the structure in front of you. An outline is like a map of your essay. It will show you how the entire piece works together.

- Proofread your essay several times.

This step is vital if you want to avoid any unnecessary mistakes and typos. Sometimes great ideas can have less impact due to errors. There are several things you can do. Try reading out loud, asking a friend for feedback, or using an online grammar checker .

13 Food and Culture Essay Topics

If you still did not choose a topic for yourself, this is a place to start. We’ve gathered this list so you can pick one and develop a good essay about food and culture. Besides, check our title generator that will come up with more ideas.

Here you go:

- The place of food in Indian culture and its connection with the religion.

- A comparison of Mexican street food and Tex-Mex culinary style.

- Advantages and disadvantages of healthy eating habits.

- How did American fast food infiltrate the Chinese market?

- Why is Japanese food so important in their culture?

- Spanish influence on Filipino cuisine.

- Why is street food so essential in Korean cuisine and culture?

- Characteristics of Italian cuisine by regions and cities.

- The development of Thai eating culture and Thai cuisine.

- What is Pakistani food etiquette?

- Relationships between gastronomy, cooking, and culture in American culture.

- Key factors that influence food habits and nutrition in different countries.

- How does national cuisine reflect national mentality and traditions?;

Thanks for your attention! Hopefully, you found our tips helpful. Good luck and Bon appetite! Further down, you can click the links and read food culture and foreign cuisine essays for your inspiration.

103 Best Essay Examples on World Cuisines & Food Culture

Filipino food essay, different cooking techniques research.

- Words: 2535

Food Habits and Culture: Factors Influence

- Words: 1380

Globalization and Food Culture Essay

- Words: 3588

Ramen Culture as a Vital Part of the Traditions in Japan

- Words: 1971

Preserving and Promoting Traditional Cuisine

- Words: 12030

Food Critiques for the Three Dishes: Integral Part of French Cuisine

Lasagna cooking process and noodle preparing tips, gordon ramsay as a favorite chef, indian cuisine and its modernization, cultural role of crepes in france, indian cuisine: personal experiences, food preferences and nutrition culture.

- Words: 1397

The Triumph of French Cuisine

- Words: 2419

Chinese and Korean Cuisines Differences

The history and diversity of turkish cuisine.

- Words: 2186

Hotpot Concept and Cultural Value

- Words: 2248

Sushi: History, Origin and the Cultural Landscape

- Words: 1812

The Differences in Diet Between Chinese and Western People

- Words: 1670

Food, Eating Behavior, and Culture in Chinese Society

- Words: 1166

Weird Chinese Foods: Cultural Practices and Eating Culture

- Words: 1239

Massimo Bottura: Biography, Main Ideas, and Messages

- Words: 1042

Problem-Solution on Convenience Food in Singapore

Comparison between mexican and spanish cuisines, coffee in the historical and cultural context.

- Words: 1383

Food and Culture Links

- Words: 1119

The Concept of Food as a Leisure Experience

- Words: 1384

“Eating the Landscape” Book by Enrique Salmón

- Words: 1146

Barbecue as a Southern Cultural Icon

- Words: 2635

“The Riddle of the Sacred Cow” by Marvin Harris

- Words: 1044

Globalization and Food in Japan

- Words: 1941

Food Culture in Mexican Cuisine

“food colombusing” and cultural appropriation, the nutritional and dietary practices of indians.

- Words: 1204

The Culture of Veganism Among the Middle Class

- Words: 2778

The Fancy Street Foods in Japan: The Major Street Dishes and Traditions

- Words: 1950

Foodways: Cultural Norms and Attitudes Toward Food

Tiramisu: classic and original recipe.

- Words: 1512

Boka Drinks Entry to the Mexican Soft Drinks Market

- Words: 1471

Food and Farming: Urban Farming Benefits the Local Economy

The issue of the “cuisine” concept, “the cuisine and empire” by rachel laudan: cooking in world history, new scandinavian cuisine: honey-glazed chicken with black pepper, culinary modernization in the army, chef perceptions of modernist equipment and techniques, researching of lazio-rome cuisine, cultural tour: grocery market in mount vernon, casa mono: a multi-sensory experience as a food critic.

- Words: 1213

The Peking Duck Food System’s Sustainability

Mediterranean diet: recipes and marketing.

- Words: 2334

The Process of Korean Kimchi Fermentation

Mexican-american cuisine artifact, recipe for alice: stir-fried pasta, mangu recipe in cuisine of dominican republic, investigation of orange as a food commodity.

- Words: 1619

Brazil Food Culture and Dietary Patterns

- Words: 1763

A Sociology of Food and Nutrition: Unity of Traditions and Culture

- Words: 1934

Cocoa Production: Analysis and Traceability

Starbucks vs. dunkin coffee in terms of taste, ”the ritual of fast food” by margaret visser, the restaurant chain bueno y sano: trend overview, kelowna wine museum field trip.

- Words: 1053

Gastronomy of Tiramisu and Its Development

- Words: 2132

Gastronomy in Commercial Food Science Operation

- Words: 1870

Asian Studies Japanese Tea

History of beer: brief retrospective from the discovery of beer to nowadays.

- Words: 2098

The Process of Home Brewing Beer

The food served in venice: world famous italian foods.

- Words: 1485

Food Choices and Dietary Habits: An Interview With a Mexican Immigrant

- Words: 1381

The Most Delicious Rice Dishes

Culinary arts and garde manger investigation.

- Words: 1270

Jamaican Menu Planning: From Appetizer to Dessert

How to create a deep dish oven baked pasta, beverage management. rum: rules of thumb, beverage management: cognac as a bar product, frozen peanut butter and jelly sandwich recipe, lasagna: secrets of cooking a delicious dish, the 38th winter fancy food shows in san francisco.

- Words: 1396

Farmer’s Market as a Food Event: Fresh and Straight From the Farm

- Words: 1404

East Asian Food and Its Identifying Factors

- Words: 1139

South Korean and Japanese Cuisines and Identity

Chinese restaurant: cultural and aesthetic perspectives.

- Words: 1688

Food Nexus Models in Abu Dhabi

Family food and meals traditions in dubai history, the science of why you crave comfort food, kitchen and cooking in kalymnos people, customs and etiquette in chinese dining, bolognese sauce and italian gastronomic tradition.

- Words: 1651

American Food, Its History and Global Distribution

California restaurants’ history and cuisine style.

- Words: 1150

Mexican Cuisine’s Transition to Comfort Food

Turkey cooking: festive recipe.

- Words: 1599

The Cultural Presentation of Sushi and Okonomiyaki Recipes

- Words: 1460

Fish as a Staple of the Human Diet

- Words: 1785

Eating Chinese: Culture on the Menu

Food and culture: food habits in cape breton.

- Words: 1756

Halal Meat’s Specific Regulations

- Words: 1906

The Origins, Production and Consumption of Cumin, Trace and Explored

- Words: 2713

Culture and Food: Sanumá Relation to Food Taboos

The american way of dining out.

- Words: 1747

American Food Over the Decades

Rice: thailand native foods.

American Food Culture Essay Example

- Pages: 5 (1183 words)

- Published: April 16, 2022

Americans have exceptionally active food culture at different levels. To them, food is many things; sustenance, socialization, enjoyment, nutrition and it regularly becomes the occasion for various arguments be it political, legal action or press coverage. All Americans want to be well fed. Food satisfaction is viewed in terms of quantity and quality or even both. They are demanding and some opt fast food that can be easily accessed and at a cheaper cost. Other Americans on the extreme often look for a new experience in dining, artisanal breads and cheeses, meat and vegetables, specialty fruits, exotic gourmet products, foods that are tasty and innovative convenient for their freezers. Currently, the average American food market even in communities that are small carries gourmet and food items that are international which could only be fo

und in big cities more than twenty years ago(Nazaryan 1)

Some specific food items can be regarded as typically American as they can be found in all the places within the country. These include fried chicken and hamburgers. Every region in America nonetheless, has its own specialties and culture with regards to food. Different ethnic cuisines from all over the world also do well in the country, have an impact on the tastes of Americans and they are also affected by the eating customs of America and their food industry(Newcomb 3). A good example of a food item that had an impact on Americans is the pizza which was derived from Italy and conquered Americans and was subsequently metamorphosed into their food with modifications that could not be identified by Italians today. Cuisines from Mexico and China have also undergone through the sam

phenomenon that have seen the supermarkets in the country selling varieties of American sushi.

In America, cooking has iconic significance. American hold in the highest regard celebrity television chefs, participate in as well as watch cooking competitions and gather at food exhibition and fairs venues. Various television programs in the country show dream kitchens. Numerous Americans obtain recipes and cookbooks contending on having equipment, gadgets, cutting boards or knives and pots and pans that are endorsed by celebrities that are recent. They attend cooking classes be it professional ones or even amateur. A considerable number of them assemble all the information they can acquire on cooking from magazines, television, culinary books, the internet even though a majority of them are either very busy or lazy to cook. This results to obtaining food from fast food joints most of which are not healthy health wise (Shapiro & Dana 44)

Many Americans prefer their food to be quick, cheap and convenient irrespective of if they from a supermarket or local fast-food franchise. They go for things that are fast and simple and which require less personal or financial sacrifice. They value their image and go for food items that are appealing with some even keen on spending a lot of money on the food items that makes them appear good as when they dine in restaurant that are expensive. Cost, convenience and appearance are the main characteristics of the dominant food culture of Americans.

This contributes to a lot of illnesses and eating disorders that are related to food and particularly obesity which in America is of great concern. Big industries dealing with weight loss issues are thriving. Obesity in

children and issues of nutrition in school are continuously being discussed in the news together with other food issues such as food contamination and safety and the likelihood of food supply being contaminated by terrorists. Also on the news are the subjects’ food items that are modified genetically, food additives and livestock treatment through hormone. Always in a flux are the Federal government nutritional standards with the labelling requirements. Thriving as a result of this is big nutritional supplement industry (Nazaryan 3).

The bad food habits and illnesses that results from them haveseen the emergence of new food ethics in the country that challenges the dominant values. The demand for organic food is growing at a rapid rate which approximates at more than 20% yearly for more than ten years. These foods are not cheap neither are they attractive as compared to conventional foods and they are not even convenient in their acquisition. The initial consumers of organic foods were labelled as counter-cultural and not trend setters as they were obviously expressing a food ethic that is different. Agricultural organizations that are community supported, farmers markets and other sources of direct food advertisement have experienced rates of growth that are same to those of organic foods. The new food ethic thus cannot be defined as avoidance to genetic engineering or agricultural chemicals(Nazaryan 4). The new food ethic intends to build relations with farmers, through farmers and with the universe. Some organic consumers are certainly concerned with their well-being physically even if not exclusively. Others purchase organic foods as the roots of organics philosophically are in community and stewardship, in taking care of the earth and its

inhabitants. A majority of the people who buy food at the markets of farmers look for farmers who share the new American food ethic irrespective of whether or not their goods are organic certified.

The new food culture if viewed only in terms of sales of substitute food items such as organic, natural, free from pesticide among others may seem insignificant. This is because the sales of such goods normally amount to little than 1% of the total food sold not including the labelling of food as natural or healthy that is not dissimilar from conventional foods in substance. A lot of doubts and outright displeasure is being expressed by an increasing number of Americans with the current food system in the country. The displeasure however in not in terms of cost, appearance or convenience but rather the lack of trust in the manufacturers and distributors of corporate food, or the safety and their food nutritional value be ensured by the government. These Americans are looking for food items that will echo a different set of values ethically and not only in the food itself but also in its production and who are the beneficiaries and losers as a result of its production (Newcomb 5).

In summary, just as we can’t be tied to particular food habits because of the fears we may have, we are tied to our society and often deeply dictated by its habits and values. The people living in D.C, occupied by people who are fit and SweetGreen stores are more probable to feel pressured by the public to live and eat in a similar manner. The ones who live in areas where

people mock those who are healthy obsessively are more likely to pass by KFC for dinner. Whichever the case, we are subjected from pressure both from within and without to eat and live in a particular way which seems extremely complicated.

- Nazaryan, Alexander. "Eating Our Words." Newsweek Global 161.40 (2013): 1-4

- Newcomb, Tim. "From Steamed Hot Dogs To Fancy Flavors: NFL’S Stadium Food Revolution." Time.Com (2016): N.PAG.

- Shapiro, Laura, and Dana Goodyear. "Chefs Gone Wild." Atlantic 312.4 (2013): 40-44.

- Bruni Struggles With His Weight and Eating Essay Example

- Eating Habits Essay

- Anorexia essays

- Breakfast essays

- Caffeine essays

- Chewing gum essays

- Child Development essays

- Chocolate essays

- Diet essays

- Dieting essays

- Eating essays

- Eating Habits essays

- Energy Drink essays

- Food essays

- Genetically Modified Food essays

- Genetically Modified Organisms essays

- Junk Food essays

- Metabolism essays

- Milk essays

- vegetarian essays

- Vitamin essays

- Weight Loss essays

Haven't found what you were looking for?

Search for samples, answers to your questions and flashcards.

- Enter your topic/question

- Receive an explanation

- Ask one question at a time

- Enter a specific assignment topic

- Aim at least 500 characters

- a topic sentence that states the main or controlling idea

- supporting sentences to explain and develop the point you’re making

- evidence from your reading or an example from the subject area that supports your point

- analysis of the implication/significance/impact of the evidence finished off with a critical conclusion you have drawn from the evidence.

Unfortunately copying the content is not possible

Tell us your email address and we’ll send this sample there..

By continuing, you agree to our Terms and Conditions .

Essays About Food: Top 5 Examples and 6 Writing Prompts

Food is one of the greatest joys of life; it is both necessary to live and able to lift our spirits. If you are writing essays about food, read our guide.

Many people live and die by food. While its primary purpose is to provide us with the necessary nutrients to carry out bodily functions, the satisfaction food can give a person is beyond compare. For people of many occupations, such as chefs, waiters, bakers, and food critics, food has become a way of life.

Why do so many people enjoy food? It can provide us with the sensory pleasure we need to escape from the trials of daily life. From the moist tenderness of a good-quality steak to the sweet, rich decadence of a hot fudge sundae, food is truly magical. Instead of eating to stay alive, many even joke that they “live to eat.” In good food, every bite is like heaven.

5 Top Essay Examples

1. food essay by evelin tapia, 2. why japanese home cooking makes healthy feel effortless by kaki okumura, 3. why i love food by shuge luo.

- 4. My Favorite Food by Jayasurya Mayilsamy

- 5. Osteria Francescana: does the world’s best restaurant live up to the hype? by Tanya Gold

6 Prompts for Essays About Food

1. what is your favorite dish, 2. what is your favorite cuisine, 3. is a vegan diet sustainable, 4. the dangers of fast food, 5. a special food memory, 6. the food of your home country.

“Food has so many things in them such as calories and fat. Eating healthy is important for everyone to live a healthy life. You can eat it, but eating it daily is bad for you stay healthy and eat the right foods. Deep fried foods hurt your health in many ways. Eat healthy and exercise to reduce the chances of any health problems.”

In this essay, Tapia writes about deep-fried foods and their effects on people’s health. She says they are high in trans fat, which is detrimental to one’s health. On the other hand, she notes reasons why people still eat foods such as potato chips and french fries, including exercise and simply “making the most of life.” Despite this, Tapia asserts her position that these foods should not be eaten in excess and can lead to a variety of health issues. She encourages people to live healthy lives by enjoying food but not overeating.

“Because while a goal of many vegetables a day is admirable, in the beginning it’s much more sustainable to start with something as little as two. I learned that with an approach of two-vegetable dishes at a time, I would be a lot more consistent, and over time a large variety would become very natural. In fact, now following that framework and cooking a few simple dishes a day, I often find that it’s almost difficult to not reach at least several kinds of vegetables a day.”

Okumura discusses simple, healthy cooking in the Japanese tradition. While many tend to include as many vegetables as possible in their dishes for “health,” Okumura writes that just a few vegetables are necessary to make healthy but delicious dishes. With the help of Japanese pantry staples like miso and soy sauce, she makes a variety of traditional Japanese side dishes. She shows the wonders of food, even when executed in its simplest form.

“I make pesto out of kale stems, toast the squash seeds for salad and repurpose my leftovers into brand new dishes. I love cooking because it’s an exercise in play. Cooking is forgiving in improvisation, and it can often surprise you. For example, did you know that adding ginger juice to your fried rice adds a surprisingly refreshing flavor that whets your appetite? Neither did I, until my housemate showed me their experiment.”

In her essay, Luo writes about her love for food and cooking, specifically how she can combine different ingredients from different cuisines to make delicious dishes. She recalls experiences with her native Chinese food and Italian, Singaporean, and Japanese Cuisine. The beauty of food, she says, is the way one can improvise a dish and create something magical.

4. My Favorite Food by Jayasurya Mayilsamy

“There is no better feeling in the world than a warm pizza box on your lap. My love for Pizza is very high. I am always hungry for pizza, be it any time of the day. Cheese is the secret ingredient of any food it makes any food taste yummy. Nearly any ingredient can be put on pizza. Those diced vegetables, jalapenos, tomato sauce, cheese and mushrooms make me eat more and more like a unique work of art.”

Mayilsamy writes about pizza, a food he can’t get enough of, and why he enjoys it as much as he does. He explains the different elements of a good pizza, such as cheese, tomato sauce, other toppings, and the crust. He also briefly discusses the different types of pizzas, such as thin crust and deep dish. Finally, he gives readers an excellent description of a mouthwatering pizza, reminding them of the feeling of eating their favorite food.

5. Osteria Francescana: does the world’s best restaurant live up to the hype? by Tanya Gold

“After three hours, I am exhausted from eating Bottura’s dreams, and perhaps that is the point. If some of it is delicious, it is also consuming. That is the shadow cast by the award in the hallway, next to the one of a man strangled by food. I do not know if this is the best restaurant on Earth, or even if such a claim is possible. I suspect such lists are designed largely for marketing purposes: when else does Restaurant magazine, which runs the competition, get global coverage for itself and its sponsors?”

Gold reviews the dishes at Osteria Francescana, which is regarded by many as the #1 restaurant in the world. She describes the calm, formal ambiance and the polished interiors of the restaurants. Most importantly, she goes course by course, describing each dish in detail, from risotto inspired by the lake to parmesan cheese in different textures and temperatures. Gold concludes that while a good experience, a meal at the restaurant is time-consuming, and her experience is inconclusive as to whether or not this is the best restaurant in the world.

Everyone has a favorite food; in your essay, write about a dish you enjoy. You can discuss the recipe’s history by researching where it comes from, the famous chefs who created it, or which restaurants specialize in this dish. Provide your readers with an ingredients list, and describe how each ingredient is used in the recipe. Conclude your essay with a review of your experience recreating this recipe at home, discuss how challenging the recipe is, and if you enjoyed the experience.

Aside from a favorite dish, everyone prefers one type of cuisine. Discuss your favorite cuisine and give examples of typical dishes, preparations for food, and factors that influence your chosen cuisine. For example, you could choose Italian cuisine and discuss pasta, pizza, gelato, and other famous food items typically associated with Italian food.

Many people choose to adopt a vegan diet that consists of only plant-based food. For your essay, you can discuss this diet and explain why some people choose it. Then, research the sustainability of a plant-based diet and if a person can maintain a vegan diet while remaining healthy and energized. Provide as much evidence as possible by conducting interviews, referencing online sources, and including survey data.

Fast food is a staple part of diets worldwide; children are often raised on salty bites of chicken, fries, and burgers. However, it has been linked to many health complications, including cancer and obesity . Research the dangers of fast food, describe each in your essay, and give examples of how it can affect you mentally and physically.

Is there a memory involving food that you treasure? Perhaps it could be a holiday celebration, a birthday, or a regular day when went to a restaurant. Reflect on this memory, retelling your story in detail, and describe the meal you ate and why you remember it so fondly.

Every country has a rich culture, a big component of which is food. Research the history of food in your native country, writing about common native dishes and ingredients used in cooking. If there are religious influences on your country’s cuisine, note them as well. Share a few of these recipes in your essay for an engaging piece of writing.

Tip: If writing an essay sounds like a lot of work, simplify it. Write a simple 5 paragraph essay instead.

For help picking your next essay topic, check out the best essay topics about social media .

Martin is an avid writer specializing in editing and proofreading. He also enjoys literary analysis and writing about food and travel.

View all posts

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Asian American Food Scapes

Related Papers

John Burdick

American Quarterly

Timothy K August

Dun-Ying Yu

and Keywords The study of food in Asian American literary and cultural studies is particularly concerned with the political significance of rhetorically linking of identity and cuisine. Addressing the ways eating, cooking, and preparing food is represented in a number of literary works and cultural texts, these academic studies investigate how culinary and literary tastes serve as boundaries that define and manage racial expression. Indeed, Asian American studies scholars approach food by taking culinary taste, ethnicity, and racialized labor as co-constitutive, rather than given. For the ways Asian American chefs, cooks, eaters, and food workers engage food, in part, defines their cultural position, both internally and to the US population at large. The performative force of these acts is transformed by writers and artists into personal and sensual histories, that for various gendered, linguistic, and economic reasons would otherwise be silenced. Further, Asian American authors and artists can strategically use an interest in food and cuisine to convey the complexity, multiplicity, and history of Asian American identities and politics. Recently the study of food has been transformed into a critical practice used to combat the challenges Asian Americans endure surrounding the question of authenticity. Stories of culinary ethnic affiliation are marketable, and Frank Chin's calls of "food pornography" loom whenever a predominately white audience wolfs down overly saccharine stories of Asian American culinary solidarity. But in the same breath the genre is also commercially viable because of its unique ability to communicate culturally specific stories in ways that are appealing to younger generations unfamiliar with, or who want to learn more about, customs, traditions, and historical events. Indeed, these stories are unique insofar as they can provide material histories that explain how socioeconomic institutions reproduce racial inequity; yet remain palatable for those outside the ethnic group, even if these readers are those whose subject position comes under review. This article will serve as a reminder, then, that culinary writing remains a robust literary form that makes use of its market appeal to write about Asian America in a manner that is at once personal, material, and historically potent, while the study of this work recognizes

Life Writing

Catalog Description: The main purpose of ASAM151W is to introduce students to the conventions of academic writing and critical thinking. Students will learn Anthropological and Sociological techniques of academic writing through the lens of Asian American foodways that explore the political, economic, religious, social, and cultural context of food in Asia and Asian American Studies. Course Description: This course offers an introduction to writing at the upper-division level on the topic of Asian Foodways and considers how globalization shapes Asian Foodways. The main purpose of ASAM151W is to introduce students to the conventions of academic writing and critical thinking. Students will learn writing techniques from the field of Anthropology and Sociology. We will explore various facets of writing, using the subject of Asian and Asian American Foodways, farmers/producers, consumers, and innovators. Additionally, we will go over the pivotal roles of Asian global foodways seen in tea, noodles, siracha, soy sauce, and other food items.

Choice Reviews Online

Katharina Vester

Journal of Intercultural Studies, vol. 21, no. 3

Stefano Occhipinti , Louise Edwards

Mustafa Koc

RELATED PAPERS

Farid Wajdi

Nadia Bonora

AJIT-e Online Academic Journal of Information Technology

Nursel Yalçın

REI - REVISTA ESTUDOS INSTITUCIONAIS

Danilo dos Santos Almeida

Maria do Rosário Ribeiro

Jurnal Layanan Masyarakat (Journal of Public Services)

Puguh Nugroho

Journal of Biological Chemistry

Maria Luisa Guzman-Hernandez

Technology, Knowledge and Learning

Antri (Andry) Avraamidou

Carmen Lúcia Mottin Duro

Katja Franke

Flávia Pires

International Journal of Research in E-learning

Kateryna Yalova

Health Education Research

Nina Wallerstein

International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics

Pediatric Rheumatology

Natalia Cabrera

Journal of Business Venturing

Karla Abarca

Asian Spine Journal

Nursing Clinics of North America

Susan Westneat

2017 13th International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC)

António Furtado

ghfkfg fdgdsf

Iraqi journal of science

Huda Alabbody

Acta Crystallographica Section E Structure Reports Online

Kouakou franck junior Konan

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Comparing American and Spanish Cultures

This essay about the differences and similarities between Spanish and American food cultures explores how meal timings, social settings, and regional cuisines reflect each country’s cultural values. It discusses the communal nature of Spanish meals versus the more individualistic and convenience-oriented American approach. The essay also highlights the growing trend towards global culinary influences and sustainability in both countries, underscoring a shared appreciation for diverse and changing food practices.

How it works

The culinary traditions of Spain and the United States provide a rich ground for comparison, revealing distinct practices and attitudes towards food that echo each nation’s history, geography, and societal values. This essay delves into how these food cultures contrast with and resemble each other, and what these patterns suggest about broader cultural identities.

Meal timing and the social importance of eating starkly differ between Spain and the U.S. In Spain, meals are central social events. Spaniards typically enjoy lengthy midday breaks known as ‘la siesta,’ which extend to two hours or more, allowing time for leisure and conversation post-lunch.

Dinner occurs late, often after 9 PM, reflecting a relaxed approach to daily life. Conversely, American meals tend to be shorter and more pragmatic, with lunches often eaten quickly and alone, and dinners scheduled earlier to accommodate a faster-paced life.

In terms of meal structure, Spanish cuisine is renowned for its tapas—varied small plates that are shared amongst diners, fostering a communal eating experience. This practice highlights the Spanish emphasis on community and collective enjoyment. American dining, however, often focuses on individual servings and prioritizes convenience, exemplified by the prevalence of fast food. This reflects broader American values of efficiency and individuality.

Regional culinary diversity is another area where Spanish food culture shines. Depending on the area—coastal regions like Galicia or inland like Castile—the cuisine varies significantly, influenced by local ingredients and historical contexts. This regional specificity underscores strong local identities within Spain. American cuisine, while diverse, tends to be more uniform across the country, especially in chain dining, suggesting a more consolidated national identity.

The approach to ingredients also varies. Spanish dishes commonly use fresh, local produce, supporting nearby farmers and reflecting the health-oriented Mediterranean diet. In contrast, the American diet often includes more processed foods, though there is a growing trend towards sustainability and fresh, locally sourced ingredients through the farm-to-table movement.

Despite these differences, both Spanish and American food cultures have embraced international cuisines, thanks to globalization and diverse populations. This reflects a shared openness to global influences and the multicultural character of each society. Moreover, both cultures display a deep affection for desserts and sweet dishes, a testament to a universal love for treats.

In summary, while the food cultures of Spain and the U.S. exhibit significant differences in how meals are valued, prepared, and consumed, they also show similarities that point to a global appreciation of culinary diversity and change. These parallels and distinctions not only illuminate unique cultural traits but also connect to larger global narratives about how food is intertwined with cultural identity, economic trends, and health consciousness. Through examining these food cultures, we gain insights into not only national characteristics but also the shared aspects of human culture.

Cite this page

Comparing American And Spanish Cultures. (2024, Apr 22). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/comparing-american-and-spanish-cultures/

"Comparing American And Spanish Cultures." PapersOwl.com , 22 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/comparing-american-and-spanish-cultures/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Comparing American And Spanish Cultures . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/comparing-american-and-spanish-cultures/ [Accessed: 24 Apr. 2024]

"Comparing American And Spanish Cultures." PapersOwl.com, Apr 22, 2024. Accessed April 24, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/comparing-american-and-spanish-cultures/

"Comparing American And Spanish Cultures," PapersOwl.com , 22-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/comparing-american-and-spanish-cultures/. [Accessed: 24-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Comparing American And Spanish Cultures . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/comparing-american-and-spanish-cultures/ [Accessed: 24-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Soul Food — Soul Food in the African American Community

Soul Food in The African American Community

- Categories: African American Culture African American History Soul Food

About this sample

Words: 1349 |

Published: Oct 2, 2020

Words: 1349 | Pages: 3 | 7 min read

Works Cited

- Henderson, L. (2009). Soul Food as Cultural Creation. In C. D. Green & C. R. Sheller (Eds.), Consuming the Caribbean: From Arawaks to Zombies (pp. 89-106). University of Virginia Press.

- Opie, F. (2008). The Food of My Soul: Soul Food, Space, and Identity. In E. N. Wilk & A. L. Barbosa (Eds.), Rice and Beans: A Unique Dish in a Hundred Places (pp. 251-268). Berg Publishers.

- Edge, J. T. (2017). The Potlikker Papers: A Food History of the Modern South. Penguin Books.

- Twitty, M. W. (2017). The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South. HarperCollins.

- Opie, F. (2008). Hog and Hominy: Soul Food from Africa to America. Columbia University Press.

- McWilliams, M. (2018). Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Opie, F. (2009). Culinary History at the Crossroads. The Southern Quarterly, 46(2), 12-26.

- Harris, J. (2011). High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America. Bloomsbury USA.

- Opie, F. (2008). Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine. In J. Wallach (Ed.), Cooking Up Country Music (pp. 153-167). University Press of Kentucky.

- Williams-Forson, P. A. (2006). Building Houses out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power. The University of North Carolina Press.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Arts & Culture History Life

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 1659 words

4 pages / 1912 words

6 pages / 2954 words

1 pages / 1454 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Soul Food

Food is more than just sustenance; it is an integral part of our lives. From the moment we are born, food plays a crucial role in our growth, development, and overall well-being. Not only does it provide us with the necessary [...]

Within every ethnic group there are many forms of culture. Each culture is divided into various categories. These categories can be referred to as subcultures. Subcultures are smaller segments of a culture that are not against [...]

Giorgio Bassani’s novel The Garden of the Finzi-Continis is told from the perspective of an unnamed speaker who is recalling his time spent with the Finzi-Contini family prior to the family members' deaths in the Holocaust. [...]

Christopher Marlowe’s play entitled, Doctor Faustus, tells the story of a curious and ambitious man who has grown tired of focusing on all of the traditional areas of study, and wishes to learn something less known by [...]

Goals are the most important thing in a person’s life, without them your life would just be plain and boring not excitement at all. Without making goals in your life you would have nothing to look forward to, or even have [...]

Adams, J. T. (1931). The Epic of America. Little, Brown, and Company.Bellamy, E. (1888). Looking Backward: 2000-1887. Ticknor and Company.Dixon, T. (2015). The Essential America: Our Founders and the Liberal Tradition. Pelican [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

What It Means To Be Asian in America

The lived experiences and perspectives of asian americans in their own words.

Asians are the fastest growing racial and ethnic group in the United States. More than 24 million Americans in the U.S. trace their roots to more than 20 countries in East and Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent.

The majority of Asian Americans are immigrants, coming to understand what they left behind and building their lives in the United States. At the same time, there is a fast growing, U.S.-born generation of Asian Americans who are navigating their own connections to familial heritage and their own experiences growing up in the U.S.

In a new Pew Research Center analysis based on dozens of focus groups, Asian American participants described the challenges of navigating their own identity in a nation where the label “Asian” brings expectations about their origins, behavior and physical self. Read on to see, in their own words, what it means to be Asian in America.

Table of Contents

Introduction, this is how i view my identity, this is how others see and treat me, this is what it means to be home in america, about this project, methodological note, acknowledgments.

No single experience defines what it means to be Asian in the United States today. Instead, Asian Americans’ lived experiences are in part shaped by where they were born, how connected they are to their family’s ethnic origins, and how others – both Asians and non-Asians – see and engage with them in their daily lives. Yet despite diverse experiences, backgrounds and origins, shared experiences and common themes emerged when we asked: “What does it mean to be Asian in America?”

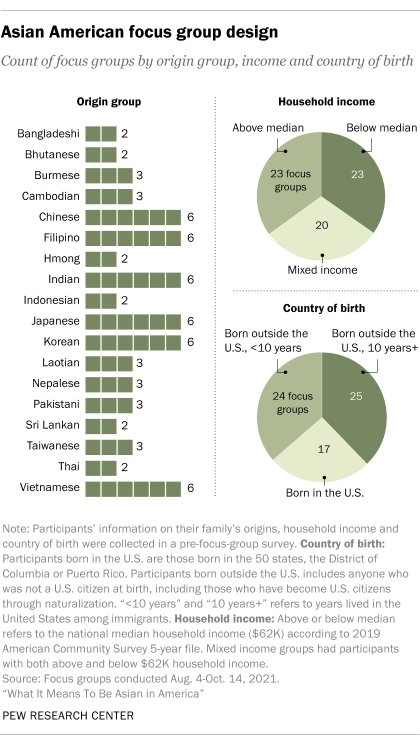

In the fall of 2021, Pew Research Center undertook the largest focus group study it had ever conducted – 66 focus groups with 264 total participants – to hear Asian Americans talk about their lived experiences in America. The focus groups were organized into 18 distinct Asian ethnic origin groups, fielded in 18 languages and moderated by members of their own ethnic groups. Because of the pandemic, the focus groups were conducted virtually, allowing us to recruit participants from all parts of the United States. This approach allowed us to hear a diverse set of voices – especially from less populous Asian ethnic groups whose views, attitudes and opinions are seldom presented in traditional polling. The approach also allowed us to explore the reasons behind people’s opinions and choices about what it means to belong in America, beyond the preset response options of a traditional survey.

The terms “Asian,” “Asians living in the United States” and “Asian American” are used interchangeably throughout this essay to refer to U.S. adults who self-identify as Asian, either alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic identity.

“The United States” and “the U.S.” are used interchangeably with “America” for variations in the writing.

Multiracial participants are those who indicate they are of two or more racial backgrounds (one of which is Asian). Multiethnic participants are those who indicate they are of two or more ethnicities, including those identified as Asian with Hispanic background.

U.S. born refers to people born in the 50 U.S. states or the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, or other U.S. territories.

Immigrant refers to people who were not U.S. citizens at birth – in other words, those born outside the U.S., Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories to parents who were not U.S. citizens. The terms “immigrant,” “first generation” and “foreign born” are used interchangeably in this report.

Second generation refers to people born in the 50 states or the District of Columbia with at least one first-generation, or immigrant, parent.

The pan-ethnic term “Asian American” describes the population of about 22 million people living in the United States who trace their roots to more than 20 countries in East and Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. The term was popularized by U.S. student activists in the 1960s and was eventually adopted by the U.S. Census Bureau. However, the “Asian” label masks the diverse demographics and wide economic disparities across the largest national origin groups (such as Chinese, Indian, Filipino) and the less populous ones (such as Bhutanese, Hmong and Nepalese) living in America. It also hides the varied circumstances of groups immigrated to the U.S. and how they started their lives there. The population’s diversity often presents challenges . Conventional survey methods typically reflect the voices of larger groups without fully capturing the broad range of views, attitudes, life starting points and perspectives experienced by Asian Americans. They can also limit understanding of the shared experiences across this diverse population.

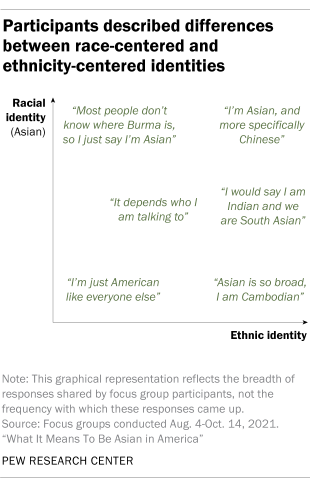

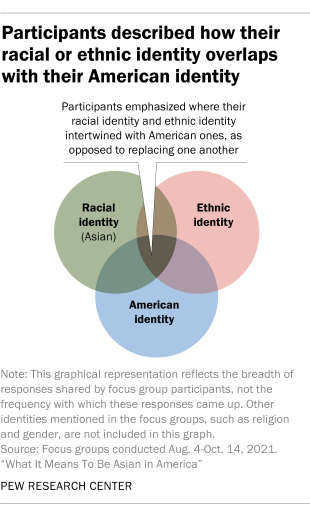

Across all focus groups, some common findings emerged. Participants highlighted how the pan-ethnic “Asian” label used in the U.S. represented only one part of how they think of themselves. For example, recently arrived Asian immigrant participants told us they are drawn more to their ethnic identity than to the more general, U.S.-created pan-ethnic Asian American identity. Meanwhile, U.S.-born Asian participants shared how they identified, at times, as Asian but also, at other times, by their ethnic origin and as Americans.

Another common finding among focus group participants is the disconnect they noted between how they see themselves and how others view them. Sometimes this led to maltreatment of them or their families, especially at heightened moments in American history such as during Japanese incarceration during World War II, the aftermath of 9/11 and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic. Beyond these specific moments, many in the focus groups offered their own experiences that had revealed other people’s assumptions or misconceptions about their identity.

Another shared finding is the multiple ways in which participants take and express pride in their cultural and ethnic backgrounds while also feeling at home in America, celebrating and blending their unique cultural traditions and practices with those of other Americans.

This focus group project is part of a broader research agenda about Asians living in the United States. The findings presented here offer a small glimpse of what participants told us, in their own words, about how they identify themselves, how others see and treat them, and more generally, what it means to be Asian in America.

Illustrations by Jing Li

Publications from the Being Asian in America project

- Read the data essay: What It Means to Be Asian in America

- Watch the documentary: Being Asian in America

- Explore the interactive: In Their Own Words: The Diverse Perspectives of Being Asian in America

- View expanded interviews: Extended Interviews: Being Asian in America

- About this research project: More on the Being Asian in America project

- Q&A: Why and how Pew Research Center conducted 66 focus groups with Asian Americans

One of the topics covered in each focus group was how participants viewed their own racial or ethnic identity. Moderators asked them how they viewed themselves, and what experiences informed their views about their identity. These discussions not only highlighted differences in how participants thought about their own racial or ethnic background, but they also revealed how different settings can influence how they would choose to identify themselves. Across all focus groups, the general theme emerged that being Asian was only one part of how participants viewed themselves.

The pan-ethnic label ‘Asian’ is often used more in formal settings

“I think when I think of the Asian Americans, I think that we’re all unique and different. We come from different cultures and backgrounds. We come from unique stories, not just as a group, but just as individual humans.” Mali , documentary participant

Many participants described a complicated relationship with the pan-ethnic labels “Asian” or “Asian American.” For some, using the term was less of an active choice and more of an imposed one, with participants discussing the disconnect between how they would like to identify themselves and the available choices often found in formal settings. For example, an immigrant Pakistani woman remarked how she typically sees “Asian American” on forms, but not more specific options. Similarly, an immigrant Burmese woman described her experience of applying for jobs and having to identify as “Asian,” as opposed to identifying by her ethnic background, because no other options were available. These experiences highlight the challenges organizations like government agencies and employers have in developing surveys or forms that ask respondents about their identity. A common sentiment is one like this:

“I guess … I feel like I just kind of check off ‘Asian’ [for] an application or the test forms. That’s the only time I would identify as Asian. But Asian is too broad. Asia is a big continent. Yeah, I feel like it’s just too broad. To specify things, you’re Taiwanese American, that’s exactly where you came from.”

–U.S.-born woman of Taiwanese origin in early 20s

Smaller ethnic groups default to ‘Asian’ since their groups are less recognizable

Other participants shared how their experiences in explaining the geographic location and culture of their origin country led them to prefer “Asian” when talking about themselves with others. This theme was especially prominent among those belonging to smaller origin groups such as Bangladeshis and Bhutanese. A Lao participant remarked she would initially say “Asian American” because people might not be familiar with “Lao.”

“[When I fill out] forms, I select ‘Asian American,’ and that’s why I consider myself as an Asian American. [It is difficult to identify as] Nepali American [since] there are no such options in forms. That’s why, Asian American is fine to me.”

–Immigrant woman of Nepalese origin in late 20s

“Coming to a big country like [the United States], when people ask where we are from … there are some people who have no idea about Bhutan, so we end up introducing ourselves as being Asian.”

–Immigrant woman of Bhutanese origin in late 40s

But for many, ‘Asian’ as a label or identity just doesn’t fit

Many participants felt that neither “Asian” nor “Asian American” truly captures how they view themselves and their identity. They argue that these labels are too broad or too ambiguous, as there are so many different groups included within these labels. For example, a U.S.-born Pakistani man remarked on how “Asian” lumps many groups together – that the term is not limited to South Asian groups such as Indian and Pakistani, but also includes East Asian groups. Similarly, an immigrant Nepalese man described how “Asian” often means Chinese for many Americans. A Filipino woman summed it up this way:

“Now I consider myself to be both Filipino and Asian American, but growing up in [Southern California] … I didn’t start to identify as Asian American until college because in [the Los Angeles suburb where I lived], it’s a big mix of everything – Black, Latino, Pacific Islander and Asian … when I would go into spaces where there were a lot of other Asians, especially East Asians, I didn’t feel like I belonged. … In media, right, like people still associate Asian with being East Asian.”

–U.S.-born woman of Filipino origin in mid-20s

Participants also noted they have encountered confusion or the tendency for others to view Asian Americans as people from mostly East Asian countries, such as China, Japan and Korea. For some, this confusion even extends to interactions with other Asian American groups. A Pakistani man remarked on how he rarely finds Pakistani or Indian brands when he visits Asian stores. Instead, he recalled mostly finding Vietnamese, Korean and Chinese items.

Among participants of South Asian descent, some identified with the label “South Asian” more than just “Asian.” There were other nuances, too, when it comes to the labels people choose. Some Indian participants, for example, said people sometimes group them with Native Americans who are also referred to as Indians in the United States. This Indian woman shared her experience at school:

“I love South Asian or ‘Desi’ only because up until recently … it’s fairly new to say South Asian. I’ve always said ‘Desi’ because growing up … I’ve had to say I’m the red dot Indian, not the feather Indian. So annoying, you know? … Always a distinction that I’ve had to make.”

–U.S.-born woman of Indian origin in late 20s

Participants with multiethnic or multiracial backgrounds described their own unique experiences with their identity. Rather than choosing one racial or ethnic group over the other, some participants described identifying with both groups, since this more accurately describes how they see themselves. In some cases, this choice reflected the history of the Asian diaspora. For example, an immigrant Cambodian man described being both Khmer/Cambodian and Chinese, since his grandparents came from China. Some other participants recalled going through an “identity crisis” as they navigated between multiple identities. As one woman explained:

“I would say I went through an identity crisis. … It’s because of being multicultural. … There’s also French in the mix within my family, too. Because I don’t identify, speak or understand the language, I really can’t connect to the French roots … I’m in between like Cambodian and Thai, and then Chinese and then French … I finally lumped it up. I’m just an Asian American and proud of all my roots.”

–U.S.-born woman of Cambodian origin in mid-30s

In other cases, the choice reflected U.S. patterns of intermarriage. Asian newlyweds have the highest intermarriage rate of any racial or ethnic group in the country. One Japanese-origin man with Hispanic roots noted:

“So I would like to see myself as a Hispanic Asian American. I want to say Hispanic first because I have more of my mom’s culture in me than my dad’s culture. In fact, I actually have more American culture than my dad’s culture for what I do normally. So I guess, Hispanic American Asian.”

–U.S.-born man of Hispanic and Japanese origin in early 40s

Other identities beyond race or ethnicity are also important

Focus group participants also talked about their identity beyond the racial or ethnic dimension. For example, one Chinese woman noted that the best term to describe her would be “immigrant.” Faith and religious ties were also important to some. One immigrant participant talked about his love of Pakistani values and how religion is intermingled into Pakistani culture. Another woman explained:

“[Japanese language and culture] are very important to me and ingrained in me because they were always part of my life, and I felt them when I was growing up. Even the word itadakimasu reflects Japanese culture or the tradition. Shinto religion is a part of the culture. They are part of my identity, and they are very important to me.”

–Immigrant woman of Japanese origin in mid-30s

For some, gender is another important aspect of identity. One Korean participant emphasized that being a woman is an important part of her identity. For others, sexual orientation is an essential part of their overall identity. One U.S.-born Filipino participant described herself as “queer Asian American.” Another participant put it this way:

“I belong to the [LGBTQ] community … before, what we only know is gay and lesbian. We don’t know about being queer, nonbinary. [Here], my horizon of knowing what genders and gender roles is also expanded … in the Philippines, if you’ll be with same sex, you’re considered gay or lesbian. But here … what’s happening is so broad, on how you identify yourself.”

–Immigrant woman of Filipino origin in early 20s

Immigrant identity is tied to their ethnic heritage

Participants born outside the United States tended to link their identity with their ethnic heritage. Some felt strongly connected with their ethnic ties due to their citizenship status. For others, the lack of permanent residency or citizenship meant they have stronger ties to their ethnicity and birthplace. And in some cases, participants said they held on to their ethnic identity even after they became U.S. citizens. One woman emphasized that she will always be Taiwanese because she was born there, despite now living in the U.S.

For other participants, family origin played a central role in their identity, regardless of their status in the U.S. According to some of them, this attitude was heavily influenced by their memories and experiences in early childhood when they were still living in their countries of origin. These influences are so profound that even after decades of living in the U.S., some still feel the strong connection to their ethnic roots. And those with U.S.-born children talked about sending their kids to special educational programs in the U.S. to learn about their ethnic heritage.

“Yes, as for me, I hold that I am Khmer because our nationality cannot be deleted, our identity is Khmer as I hold that I am Khmer … so I try, even [with] my children today, I try to learn Khmer through Zoom through the so-called Khmer Parent Association.”

–Immigrant man of Cambodian origin in late 50s

Navigating life in America is an adjustment

Many participants pointed to cultural differences they have noticed between their ethnic culture and U.S. culture. One of the most distinct differences is in food. For some participants, their strong attachment to the unique dishes of their families and their countries of origin helps them maintain strong ties to their ethnic identity. One Sri Lankan participant shared that her roots are still in Sri Lanka, since she still follows Sri Lankan traditions in the U.S. such as preparing kiribath (rice with coconut milk) and celebrating Ramadan.

For other participants, interactions in social settings with those outside their own ethnic group circles highlighted cultural differences. One Bangladeshi woman talked about how Bengalis share personal stories and challenges with each other, while others in the U.S. like to have “small talk” about TV series or clothes.

Many immigrants in the focus groups have found it is easier to socialize when they are around others belonging to their ethnicity. When interacting with others who don’t share the same ethnicity, participants noted they must be more self-aware about cultural differences to avoid making mistakes in social interactions. Here, participants described the importance of learning to “fit in,” to avoid feeling left out or excluded. One Korean woman said:

“Every time I go to a party, I feel unwelcome. … In Korea, when I invite guests to my house and one person sits without talking, I come over and talk and treat them as a host. But in the United States, I have to go and mingle. I hate mingling so much. I have to talk and keep going through unimportant stories. In Korea, I am assigned to a dinner or gathering. I have a party with a sense of security. In America, I have nowhere to sit, and I don’t know where to go and who to talk to.”

–Immigrant woman of Korean origin in mid-40s

And a Bhutanese immigrant explained:

“In my case, I am not an American. I consider myself a Bhutanese. … I am a Bhutanese because I do not know American culture to consider myself as an American. It is very difficult to understand the sense of humor in America. So, we are pure Bhutanese in America.”

–Immigrant man of Bhutanese origin in early 40s

Language was also a key aspect of identity for the participants. Many immigrants in the focus groups said they speak a language other than English at home and in their daily lives. One Vietnamese man considered himself Vietnamese since his Vietnamese is better than his English. Others emphasized their English skills. A Bangladeshi participant felt that she was more accepted in the workplace when she does more “American” things and speaks fluent English, rather than sharing things from Bangladeshi culture. She felt that others in her workplace correlate her English fluency with her ability to do her job. For others born in the U.S., the language they speak at home influences their connection to their ethnic roots.

“Now if I go to my work and do show my Bengali culture and Asian culture, they are not going to take anything out of it. So, basically, I have to show something that they are interested in. I have to show that I am American, [that] I can speak English fluently. I can do whatever you give me as a responsibility. So, in those cases I can’t show anything about my culture.”

–Immigrant woman of Bangladeshi origin in late 20s

“Being bi-ethnic and tri-cultural creates so many unique dynamics, and … one of the dynamics has to do with … what it is to be Americanized. … One of the things that played a role into how I associate the identity is language. Now, my father never spoke Spanish to me … because he wanted me to develop a fluency in English, because for him, he struggled with English. What happened was three out of the four people that raised me were Khmer … they spoke to me in Khmer. We’d eat breakfast, lunch and dinner speaking Khmer. We’d go to the temple in Khmer with the language and we’d also watch videos and movies in Khmer. … Looking into why I strongly identify with the heritage, one of the reasons is [that] speaking that language connects to the home I used to have [as my families have passed away].”

–U.S.-born man of Cambodian origin in early 30s

Balancing between individualistic and collective thinking

For some immigrant participants, the main differences between themselves and others who are seen as “truly American” were less about cultural differences, or how people behave, and more about differences in “mindset,” or how people think . Those who identified strongly with their ethnicity discussed how their way of thinking is different from a “typical American.” To some, the “American mentality” is more individualistic, with less judgment on what one should do or how they should act . One immigrant Japanese man, for example, talked about how other Japanese-origin co-workers in the U.S. would work without taking breaks because it’s culturally inconsiderate to take a break while others continued working. However, he would speak up for himself and other workers when they are not taking any work breaks. He attributed this to his “American” way of thinking, which encourages people to stand up for themselves.

Some U.S.-born participants who grew up in an immigrant family described the cultural clashes that happened between themselves and their immigrant parents. Participants talked about how the second generation (children of immigrant parents) struggles to pursue their own dreams while still living up to the traditional expectations of their immigrant parents.

“I feel like one of the biggest things I’ve seen, just like [my] Asian American friends overall, is the kind of family-individualistic clash … like wanting to do your own thing is like, is kind of instilled in you as an American, like go and … follow your dream. But then you just grow up with such a sense of like also wanting to be there for your family and to live up to those expectations, and I feel like that’s something that’s very pronounced in Asian cultures.”

–U.S.-born man of Indian origin in mid-20s

Discussions also highlighted differences about gender roles between growing up in America compared with elsewhere.

“As a woman or being a girl, because of your gender, you have to keep your mouth shut [and] wait so that they call on you for you to speak up. … I do respect our elders and I do respect hearing their guidance but I also want them to learn to hear from the younger person … because we have things to share that they might not know and that [are] important … so I like to challenge gender roles or traditional roles because it is something that [because] I was born and raised here [in America], I learn that we all have the equal rights to be able to speak and share our thoughts and ideas.”

U.S. born have mixed ties to their family’s heritage

“I think being Hmong is somewhat of being free, but being free of others’ perceptions of you or of others’ attempts to assimilate you or attempts to put pressure on you. I feel like being Hmong is to resist, really.” Pa Houa , documentary participant

How U.S.-born participants identify themselves depends on their familiarity with their own heritage, whom they are talking with, where they are when asked about their identity and what the answer is used for. Some mentioned that they have stronger ethnic ties because they are very familiar with their family’s ethnic heritage. Others talked about how their eating habits and preferred dishes made them feel closer to their ethnic identity. For example, one Korean participant shared his journey of getting closer to his Korean heritage because of Korean food and customs. When some participants shared their reasons for feeling closer to their ethnic identity, they also expressed a strong sense of pride with their unique cultural and ethnic heritage.

“I definitely consider myself Japanese American. I mean I’m Japanese and American. Really, ever since I’ve grown up, I’ve really admired Japanese culture. I grew up watching a lot of anime and Japanese black and white films. Just learning about [it], I would hear about Japanese stuff from my grandparents … myself, and my family having blended Japanese culture and American culture together.”

–U.S.-born man of Japanese origin in late 20s

Meanwhile, participants who were not familiar with their family’s heritage showed less connection with their ethnic ties. One U.S.-born woman said she has a hard time calling herself Cambodian, as she is “not close to the Cambodian community.” Participants with stronger ethnic ties talked about relating to their specific ethnic group more than the broader Asian group. Another woman noted that being Vietnamese is “more specific and unique than just being Asian” and said that she didn’t feel she belonged with other Asians. Some participants also disliked being seen as or called “Asian,” in part because they want to distinguish themselves from other Asian groups. For example, one Taiwanese woman introduces herself as Taiwanese when she can, because she had frequently been seen as Chinese.

Some in the focus groups described how their views of their own identities shifted as they grew older. For example, some U.S.-born and immigrant participants who came to the U.S. at younger ages described how their experiences in high school and the need to “fit in” were important in shaping their own identities. A Chinese woman put it this way:

“So basically, all I know is that I was born in the United States. Again, when I came back, I didn’t feel any barrier with my other friends who are White or Black. … Then I got a little confused in high school when I had trouble self-identifying if I am Asian, Chinese American, like who am I. … Should I completely immerse myself in the American culture? Should I also keep my Chinese identity and stuff like that? So yeah, that was like the middle of that mist. Now, I’m pretty clear about myself. I think I am Chinese American, Asian American, whatever people want.”

–U.S.-born woman of Chinese origin in early 20s

Identity is influenced by birthplace

“I identified myself first and foremost as American. Even on the forms that you fill out that says, you know, ‘Asian’ or ‘Chinese’ or ‘other,’ I would check the ‘other’ box, and I would put ‘American Chinese’ instead of ‘Chinese American.’” Brent , documentary participant

When talking about what it means to be “American,” participants offered their own definitions. For some, “American” is associated with acquiring a distinct identity alongside their ethnic or racial backgrounds, rather than replacing them. One Indian participant put it this way:

“I would also say [that I am] Indian American just because I find myself always bouncing between the two … it’s not even like dual identity, it just is one whole identity for me, like there’s not this separation. … I’m doing [both] Indian things [and] American things. … They use that term like ABCD … ‘American Born Confused Desi’ … I don’t feel that way anymore, although there are those moments … but I would say [that I am] Indian American for sure.”

–U.S.-born woman of Indian origin in early 30s

Meanwhile, some U.S.-born participants view being American as central to their identity while also valuing the culture of their family’s heritage.

Many immigrant participants associated the term “American” with immigration status or citizenship. One Taiwanese woman said she can’t call herself American since she doesn’t have a U.S. passport. Notably, U.S. citizenship is an important milestone for many immigrant participants, giving them a stronger sense of belonging and ultimately calling themselves American. A Bangladeshi participant shared that she hasn’t received U.S. citizenship yet, and she would call herself American after she receives her U.S. passport.

Other participants gave an even narrower definition, saying only those born and raised in the United States are truly American. One Taiwanese woman mentioned that her son would be American since he was born, raised and educated in the U.S. She added that while she has U.S. citizenship, she didn’t consider herself American since she didn’t grow up in the U.S. This narrower definition has implications for belonging. Some immigrants in the groups said they could never become truly American since the way they express themselves is so different from those who were born and raised in the U.S. A Japanese woman pointed out that Japanese people “are still very intimidated by authorities,” while those born and raised in America give their opinions without hesitation.

“As soon as I arrived, I called myself a Burmese immigrant. I had a green card, but I still wasn’t an American citizen. … Now I have become a U.S. citizen, so now I am a Burmese American.”

–Immigrant man of Burmese origin in mid-30s

“Since I was born … and raised here, I kind of always view myself as American first who just happened to be Asian or Chinese. So I actually don’t like the term Chinese American or Asian American. I’m American Asian or American Chinese. I view myself as American first.”

–U.S.-born man of Chinese origin in early 60s

“[I used to think of myself as] Filipino, but recently I started saying ‘Filipino American’ because I got [U.S.] citizenship. And it just sounds weird to say Filipino American, but I’m trying to … I want to accept it. I feel like it’s now marry-able to my identity.”

–Immigrant woman of Filipino origin in early 30s

For others, American identity is about the process of ‘becoming’ culturally American

Immigrant participants also emphasized how their experiences and time living in America inform their views of being an “American.” As a result, some started to see themselves as Americans after spending more than a decade in the U.S. One Taiwanese man considered himself an American since he knows more about the U.S. than Taiwan after living in the U.S. for over 52 years.

But for other immigrant participants, the process of “becoming” American is not about how long they have lived in the U.S., but rather how familiar they are with American culture and their ability to speak English with little to no accent. This is especially true for those whose first language is not English, as learning and speaking it without an accent can be a big challenge for some. One Bangladeshi participant shared that his pronunciation of “hot water” was very different from American English, resulting in confusions in communication. By contrast, those who were more confident in their English skills felt they can better understand American culture and values as a result, leading them to a stronger connection with an American identity.

“[My friends and family tease me for being Americanized when I go back to Japan.] I think I seem a little different to people who live in Japan. I don’t think they mean anything bad, and they [were] just joking, because I already know that I seem a little different to people who live in Japan.”

–Immigrant man of Japanese origin in mid-40s

“I value my Hmong culture, and language, and ethnicity, but I also do acknowledge, again, that I was born here in America and I’m grateful that I was born here, and I was given opportunities that my parents weren’t given opportunities for.”

–U.S.-born woman of Hmong origin in early 30s