An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Can Commun Dis Rep

- v.43(9); 2017 Sep 7

Scientific writing

Critical appraisal toolkit (cat) for assessing multiple types of evidence.

1 Memorial University School of Nursing, St. John’s, NL

2 Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, ON

Contributor: Jennifer Kruse, Public Health Agency of Canada – Conceptualization and project administration

Healthcare professionals are often expected to critically appraise research evidence in order to make recommendations for practice and policy development. Here we describe the Critical Appraisal Toolkit (CAT) currently used by the Public Health Agency of Canada. The CAT consists of: algorithms to identify the type of study design, three separate tools (for appraisal of analytic studies, descriptive studies and literature reviews), additional tools to support the appraisal process, and guidance for summarizing evidence and drawing conclusions about a body of evidence. Although the toolkit was created to assist in the development of national guidelines related to infection prevention and control, clinicians, policy makers and students can use it to guide appraisal of any health-related quantitative research. Participants in a pilot test completed a total of 101 critical appraisals and found that the CAT was user-friendly and helpful in the process of critical appraisal. Feedback from participants of the pilot test of the CAT informed further revisions prior to its release. The CAT adds to the arsenal of available tools and can be especially useful when the best available evidence comes from non-clinical trials and/or studies with weak designs, where other tools may not be easily applied.

Introduction

Healthcare professionals, researchers and policy makers are often involved in the development of public health policies or guidelines. The most valuable guidelines provide a basis for evidence-based practice with recommendations informed by current, high quality, peer-reviewed scientific evidence. To develop such guidelines, the available evidence needs to be critically appraised so that recommendations are based on the "best" evidence. The ability to critically appraise research is, therefore, an essential skill for health professionals serving on policy or guideline development working groups.

Our experience with working groups developing infection prevention and control guidelines was that the review of relevant evidence went smoothly while the critical appraisal of the evidence posed multiple challenges. Three main issues were identified. First, although working group members had strong expertise in infection prevention and control or other areas relevant to the guideline topic, they had varying levels of expertise in research methods and critical appraisal. Second, the critical appraisal tools in use at that time focused largely on analytic studies (such as clinical trials), and lacked definitions of key terms and explanations of the criteria used in the studies. As a result, the use of these tools by working group members did not result in a consistent way of appraising analytic studies nor did the tools provide a means of assessing descriptive studies and literature reviews. Third, working group members wanted guidance on how to progress from assessing individual studies to summarizing and assessing a body of evidence.

To address these issues, a review of existing critical appraisal tools was conducted. We found that the majority of existing tools were design-specific, with considerable variability in intent, criteria appraised and construction of the tools. A systematic review reported that fewer than half of existing tools had guidelines for use of the tool and interpretation of the items ( 1 ). The well-known Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) rating-of-evidence system and the Cochrane tools for assessing risk of bias were considered for use ( 2 ), ( 3 ). At that time, the guidelines for using these tools were limited, and the tools were focused primarily on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomized controlled trials. For feasibility and ethical reasons, clinical trials are rarely available for many common infection prevention and control issues ( 4 ), ( 5 ). For example, there are no intervention studies assessing which practice restrictions, if any, should be placed on healthcare workers who are infected with a blood-borne pathogen. Working group members were concerned that if they used GRADE, all evidence would be rated as very low or as low quality or certainty, and recommendations based on this evidence may be interpreted as unconvincing, even if they were based on the best or only available evidence.

The team decided to develop its own critical appraisal toolkit. So a small working group was convened, led by an epidemiologist with expertise in research, methodology and critical appraisal, with the goal of developing tools to critically appraise studies informing infection prevention and control recommendations. This article provides an overview of the Critical Appraisal Toolkit (CAT). The full document, entitled Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines Critical Appraisal Tool Kit is available online ( 6 ).

Following a review of existing critical appraisal tools, studies informing infection prevention and control guidelines that were in development were reviewed to identify the types of studies that would need to be appraised using the CAT. A preliminary draft of the CAT was used by various guideline development working groups and iterative revisions were made over a two year period. A pilot test of the CAT was then conducted which led to the final version ( 6 ).

The toolkit is set up to guide reviewers through three major phases in the critical appraisal of a body of evidence: appraisal of individual studies; summarizing the results of the appraisals; and appraisal of the body of evidence.

Tools for critically appraising individual studies

The first step in the critical appraisal of an individual study is to identify the study design; this can be surprisingly problematic, since many published research studies are complex. An algorithm was developed to help identify whether a study was an analytic study, a descriptive study or a literature review (see text box for definitions). It is critical to establish the design of the study first, as the criteria for assessment differs depending on the type of study.

Definitions of the types of studies that can be analyzed with the Critical Appraisal Toolkit*

Analytic study: A study designed to identify or measure effects of specific exposures, interventions or risk factors. This design employs the use of an appropriate comparison group to test epidemiologic hypotheses, thus attempting to identify associations or causal relationships.

Descriptive study: A study that describes characteristics of a condition in relation to particular factors or exposure of interest. This design often provides the first important clues about possible determinants of disease and is useful for the formulation of hypotheses that can be subsequently tested using an analytic design.

Literature review: A study that analyzes critical points of a published body of knowledge. This is done through summary, classification and comparison of prior studies. With the exception of meta-analyses, which statistically re-analyze pooled data from several studies, these studies are secondary sources and do not report any new or experimental work.

* Public Health Agency of Canada. Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines Critical Appraisal Tool Kit ( 6 )

Separate algorithms were developed for analytic studies, descriptive studies and literature reviews to help reviewers identify specific designs within those categories. The algorithm below, for example, helps reviewers determine which study design was used within the analytic study category ( Figure 1 ). It is based on key decision points such as number of groups or allocation to group. The legends for the algorithms and supportive tools such as the glossary provide additional detail to further differentiate study designs, such as whether a cohort study was retrospective or prospective.

Abbreviations: CBA, controlled before-after; ITS, interrupted time series; NRCT, non-randomized controlled trial; RCT, randomized controlled trial; UCBA, uncontrolled before-after

Separate critical appraisal tools were developed for analytic studies, for descriptive studies and for literature reviews, with relevant criteria in each tool. For example, a summary of the items covered in the analytic study critical appraisal tool is shown in Table 1 . This tool is used to appraise trials, observational studies and laboratory-based experiments. A supportive tool for assessing statistical analysis was also provided that describes common statistical tests used in epidemiologic studies.

The descriptive study critical appraisal tool assesses different aspects of sampling, data collection, statistical analysis, and ethical conduct. It is used to appraise cross-sectional studies, outbreak investigations, case series and case reports.

The literature review critical appraisal tool assesses the methodology, results and applicability of narrative reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

After appraisal of individual items in each type of study, each critical appraisal tool also contains instructions for drawing a conclusion about the overall quality of the evidence from a study, based on the per-item appraisal. Quality is rated as high, medium or low. While a RCT is a strong study design and a survey is a weak design, it is possible to have a poor quality RCT or a high quality survey. As a result, the quality of evidence from a study is distinguished from the strength of a study design when assessing the quality of the overall body of evidence. A definition of some terms used to evaluate evidence in the CAT is shown in Table 2 .

* Considered strong design if there are at least two control groups and two intervention groups. Considered moderate design if there is only one control and one intervention group

Tools for summarizing the evidence

The second phase in the critical appraisal process involves summarizing the results of the critical appraisal of individual studies. Reviewers are instructed to complete a template evidence summary table, with key details about each study and its ratings. Studies are listed in descending order of strength in the table. The table simplifies looking across all studies that make up the body of evidence informing a recommendation and allows for easy comparison of participants, sample size, methods, interventions, magnitude and consistency of results, outcome measures and individual study quality as determined by the critical appraisal. These evidence summary tables are reviewed by the working group to determine the rating for the quality of the overall body of evidence and to facilitate development of recommendations based on evidence.

Rating the quality of the overall body of evidence

The third phase in the critical appraisal process is rating the quality of the overall body of evidence. The overall rating depends on the five items summarized in Table 2 : strength of study designs, quality of studies, number of studies, consistency of results and directness of the evidence. The various combinations of these factors lead to an overall rating of the strength of the body of evidence as strong, moderate or weak as summarized in Table 3 .

A unique aspect of this toolkit is that recommendations are not graded but are formulated based on the graded body of evidence. Actions are either recommended or not recommended; it is the strength of the available evidence that varies, not the strength of the recommendation. The toolkit does highlight, however, the need to re-evaluate new evidence as it becomes available especially when recommendations are based on weak evidence.

Pilot test of the CAT

Of 34 individuals who indicated an interest in completing the pilot test, 17 completed it. Multiple peer-reviewed studies were selected representing analytic studies, descriptive studies and literature reviews. The same studies were assigned to participants with similar content expertise. Each participant was asked to appraise three analytic studies, two descriptive studies and one literature review, using the appropriate critical appraisal tool as identified by the participant. For each study appraised, one critical appraisal tool and the associated tool-specific feedback form were completed. Each participant also completed a single general feedback form. A total of 101 of 102 critical appraisals were conducted and returned, with 81 tool-specific feedback forms and 14 general feedback forms returned.

The majority of participants (>85%) found the flow of each tool was logical and the length acceptable but noted they still had difficulty identifying the study designs ( Table 4 ).

* Number of tool-specific forms returned for total number of critical appraisals conducted

The vast majority of the feedback forms (86–93%) indicated that the different tools facilitated the critical appraisal process. In the assessment of consistency, however, only four of ten analytic studies appraised (40%), had complete agreement on the rating of overall study quality by participants, the other six studies had differences noted as mismatches. Four of the six studies with mismatches were observational studies. The differences were minor. None of the mismatches included a study that was rated as both high and low quality by different participants. Based on the comments provided by participants, most mismatches could likely have been resolved through discussion with peers. Mismatched ratings were not an issue for the descriptive studies and literature reviews. In summary, the pilot test provided useful feedback on different aspects of the toolkit. Revisions were made to address the issues identified from the pilot test and thus strengthen the CAT.

The Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines Critical Appraisal Tool Kit was developed in response to the needs of infection control professionals reviewing literature that generally did not include clinical trial evidence. The toolkit was designed to meet the identified needs for training in critical appraisal with extensive instructions and dictionaries, and tools applicable to all three types of studies (analytic studies, descriptive studies and literature reviews). The toolkit provided a method to progress from assessing individual studies to summarizing and assessing the strength of a body of evidence and assigning a grade. Recommendations are then developed based on the graded body of evidence. This grading system has been used by the Public Health Agency of Canada in the development of recent infection prevention and control guidelines ( 5 ), ( 7 ). The toolkit has also been used for conducting critical appraisal for other purposes, such as addressing a practice problem and serving as an educational tool ( 8 ), ( 9 ).

The CAT has a number of strengths. It is applicable to a wide variety of study designs. The criteria that are assessed allow for a comprehensive appraisal of individual studies and facilitates critical appraisal of a body of evidence. The dictionaries provide reviewers with a common language and criteria for discussion and decision making.

The CAT also has a number of limitations. The tools do not address all study designs (e.g., modelling studies) and the toolkit provides limited information on types of bias. Like the majority of critical appraisal tools ( 10 ), ( 11 ), these tools have not been tested for validity and reliability. Nonetheless, the criteria assessed are those indicated as important in textbooks and in the literature ( 12 ), ( 13 ). The grading scale used in this toolkit does not allow for comparison of evidence grading across organizations or internationally, but most reviewers do not need such comparability. It is more important that strong evidence be rated higher than weak evidence, and that reviewers provide rationales for their conclusions; the toolkit enables them to do so.

Overall, the pilot test reinforced that the CAT can help with critical appraisal training and can increase comfort levels for those with limited experience. Further evaluation of the toolkit could assess the effectiveness of revisions made and test its validity and reliability.

A frequent question regarding this toolkit is how it differs from GRADE as both distinguish stronger evidence from weaker evidence and use similar concepts and terminology. The main differences between GRADE and the CAT are presented in Table 5 . Key differences include the focus of the CAT on rating the quality of individual studies, and the detailed instructions and supporting tools that assist those with limited experience in critical appraisal. When clinical trials and well controlled intervention studies are or become available, GRADE and related tools from Cochrane would be more appropriate ( 2 ), ( 3 ). When descriptive studies are all that is available, the CAT is very useful.

Abbreviation: GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

The Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines Critical Appraisal Tool Kit was developed in response to needs for training in critical appraisal, assessing evidence from a wide variety of research designs, and a method for going from assessing individual studies to characterizing the strength of a body of evidence. Clinician researchers, policy makers and students can use these tools for critical appraisal of studies whether they are trying to develop policies, find a potential solution to a practice problem or critique an article for a journal club. The toolkit adds to the arsenal of critical appraisal tools currently available and is especially useful in assessing evidence from a wide variety of research designs.

Authors’ Statement

DM – Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data collection and curation and writing – original draft, review and editing

TO – Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data collection and curation and writing – original draft, review and editing

KD – Conceptualization, review and editing, supervision and project administration

Acknowledgements

We thank the Infection Prevention and Control Expert Working Group of the Public Health Agency of Canada for feedback on the development of the toolkit, Lisa Marie Wasmund for data entry of the pilot test results, Katherine Defalco for review of data and cross-editing of content and technical terminology for the French version of the toolkit, Laurie O’Neil for review and feedback on early versions of the toolkit, Frédéric Bergeron for technical support with the algorithms in the toolkit and the Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control of the Public Health Agency of Canada for review, feedback and ongoing use of the toolkit. We thank Dr. Patricia Huston, Canada Communicable Disease Report Editor-in-Chief, for a thorough review and constructive feedback on the draft manuscript.

Conflict of interest: None.

Funding: This work was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Conducting a Literature Review

- Literature Review

- Developing a Topic

- Planning Your Literature Review

- Developing a Search Strategy

- Managing Citations

- Critical Appraisal Tools

- Writing a Literature Review

Appraise Your Research Articles

The structure of a literature review should include the following :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Value -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

Reviewing the Literature

While conducting a review of the literature, maximize the time you devote to writing this part of your paper by thinking broadly about what you should be looking for and evaluating. Review not just what the articles are saying, but how are they saying it.

Some questions to ask:

- How are they organizing their ideas?

- What methods have they used to study the problem?

- What theories have been used to explain, predict, or understand their research problem?

- What sources have they cited to support their conclusions?

- How have they used non-textual elements [e.g., charts, graphs, figures, etc.] to illustrate key points?

- When you begin to write your literature review section, you'll be glad you dug deeper into how the research was designed and constructed because it establishes a means for developing more substantial analysis and interpretation of the research problem.

Tools for Critical Appraisal

Now, that you have found articles based on your research question you can appraise the quality of those articles. These are resources you can use to appraise different study designs.

Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (Oxford)

University of Glasgow

"AFP uses the Strength-of-Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT), to label key recommendations in clinical review articles."

- SORT: Rating the Strength of Evidence American Family Physician and other family medicine journals use the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT) system for rating bodies of evidence for key clinical recommendations.

- The Interprofessional Health Sciences Library

- 123 Metro Boulevard

- Nutley, NJ 07110

- [email protected]

- Visiting Campus

- News and Events

- Parents and Families

- Web Accessibility

- Career Center

- Public Safety

- Accountability

- Privacy Statements

- Report a Problem

- Login to LibApps

- University of Texas Libraries

- UT Libraries

Systematic Reviews & Evidence Synthesis Methods

Critical appraisal.

- Types of Reviews

- Formulate Question

- Find Existing Reviews & Protocols

- Register a Protocol

- Searching Systematically

- Supplementary Searching

- Managing Results

- Deduplication

- Glossary of terms

- Librarian Support

- Video tutorials This link opens in a new window

- Systematic Review & Evidence Synthesis Boot Camp

Some reviews require a critical appraisal for each study that makes it through the screening process. This involves a risk of bias assessment and/or a quality assessment. The goal of these reviews is not just to find all of the studies, but to determine their methodological rigor, and therefore, their credibility.

"Critical appraisal is the balanced assessment of a piece of research, looking for its strengths and weaknesses and them coming to a balanced judgement about its trustworthiness and its suitability for use in a particular context." 1

It's important to consider the impact that poorly designed studies could have on your findings and to rule out inaccurate or biased work.

Selection of a valid critical appraisal tool, testing the tool with several of the selected studies, and involving two or more reviewers in the appraisal are good practices to follow.

1. Purssell E, McCrae N. How to Perform a Systematic Literature Review: A Guide for Healthcare Researchers, Practitioners and Students. 1st ed. Springer ; 2020.

Evaluation Tools

- The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation Instrument (AGREE II) The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation Instrument (AGREE II) was developed to address the issue of variability in the quality of practice guidelines.

- Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM). Critical Appraisal Tools "contains useful tools and downloads for the critical appraisal of different types of medical evidence. Example appraisal sheets are provided together with several helpful examples."

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Checklists Critical Appraisal checklists for many different study types

- Critical Review Form for Qualitative Studies Version 2, developed out of McMaster University

- Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS) Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, et al. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016;6:e011458. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458

- Downs & Black Checklist for Assessing Studies Downs, S. H., & Black, N. (1998). The Feasibility of Creating a Checklist for the Assessment of the Methodological Quality Both of Randomised and Non-Randomised Studies of Health Care Interventions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (1979-), 52(6), 377–384.

- GRADE The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) working group "has developed a common, sensible and transparent approach to grading quality (or certainty) of evidence and strength of recommendations."

- Grade Handbook Full handbook on the GRADE method for grading quality of evidence.

- MAGIC (Making GRADE the Irresistible choice) Clear succinct guidance in how to use GRADE

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tools "JBI’s critical appraisal tools assist in assessing the trustworthiness, relevance and results of published papers." Includes checklists for 13 types of articles.

- Latitudes Network This is a searchable library of validity assessment tools for use in evidence syntheses. This website also provides access to training on the process of validity assessment.

- Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool A tool that can be used to appraise a mix of studies that are included in a systematic review - qualitative research, RCTs, non-randomized studies, quantitative studies, mixed methods studies.

- RoB 2 Tool Higgins JPT, Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Hróbjartsson A, Boutron I, Reeves B, Eldridge S. A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials In: Chandler J, McKenzie J, Boutron I, Welch V (editors). Cochrane Methods. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 10 (Suppl 1). dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD201601.

- ROBINS-I Risk of Bias for non-randomized (observational) studies or cohorts of interventions Sterne J A, Hernán M A, Reeves B C, Savović J, Berkman N D, Viswanathan M et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions BMJ 2016; 355 :i4919 doi:10.1136/bmj.i4919

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Critical Appraisal Notes and Checklists "Methodological assessment of studies selected as potential sources of evidence is based on a number of criteria that focus on those aspects of the study design that research has shown to have a significant effect on the risk of bias in the results reported and conclusions drawn. These criteria differ between study types, and a range of checklists is used to bring a degree of consistency to the assessment process."

- The TREND Statement (CDC) Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N, and the TREND Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: The TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:361-366.

- Assembling the Pieces of a Systematic Reviews, Chapter 8: Evaluating: Study Selection and Critical Appraisal.

- How to Perform a Systematic Literature Review, Chapter: Critical Appraisal: Assessing the Quality of Studies.

Other library guides

- Duke University Medical Center Library. Systematic Reviews: Assess for Quality and Bias

- UNC Health Sciences Library. Systematic Reviews: Assess Quality of Included Studies

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 11:05 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/systematicreviews

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 16 September 2004

A systematic review of the content of critical appraisal tools

- Persis Katrak 1 ,

- Andrea E Bialocerkowski 2 ,

- Nicola Massy-Westropp 1 ,

- VS Saravana Kumar 1 &

- Karen A Grimmer 1

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 4 , Article number: 22 ( 2004 ) Cite this article

157k Accesses

208 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

Consumers of research (researchers, administrators, educators and clinicians) frequently use standard critical appraisal tools to evaluate the quality of published research reports. However, there is no consensus regarding the most appropriate critical appraisal tool for allied health research. We summarized the content, intent, construction and psychometric properties of published, currently available critical appraisal tools to identify common elements and their relevance to allied health research.

A systematic review was undertaken of 121 published critical appraisal tools sourced from 108 papers located on electronic databases and the Internet. The tools were classified according to the study design for which they were intended. Their items were then classified into one of 12 criteria based on their intent. Commonly occurring items were identified. The empirical basis for construction of the tool, the method by which overall quality of the study was established, the psychometric properties of the critical appraisal tools and whether guidelines were provided for their use were also recorded.

Eighty-seven percent of critical appraisal tools were specific to a research design, with most tools having been developed for experimental studies. There was considerable variability in items contained in the critical appraisal tools. Twelve percent of available tools were developed using specified empirical research. Forty-nine percent of the critical appraisal tools summarized the quality appraisal into a numeric summary score. Few critical appraisal tools had documented evidence of validity of their items, or reliability of use. Guidelines regarding administration of the tools were provided in 43% of cases.

Conclusions

There was considerable variability in intent, components, construction and psychometric properties of published critical appraisal tools for research reports. There is no "gold standard' critical appraisal tool for any study design, nor is there any widely accepted generic tool that can be applied equally well across study types. No tool was specific to allied health research requirements. Thus interpretation of critical appraisal of research reports currently needs to be considered in light of the properties and intent of the critical appraisal tool chosen for the task.

Peer Review reports

Consumers of research (clinicians, researchers, educators, administrators) frequently use standard critical appraisal tools to evaluate the quality and utility of published research reports [ 1 ]. Critical appraisal tools provide analytical evaluations of the quality of the study, in particular the methods applied to minimise biases in a research project [ 2 ]. As these factors potentially influence study results, and the way that the study findings are interpreted, this information is vital for consumers of research to ascertain whether the results of the study can be believed, and transferred appropriately into other environments, such as policy, further research studies, education or clinical practice. Hence, choosing an appropriate critical appraisal tool is an important component of evidence-based practice.

Although the importance of critical appraisal tools has been acknowledged [ 1 , 3 – 5 ] there appears to be no consensus regarding the 'gold standard' tool for any medical evidence. In addition, it seems that consumers of research are faced with a large number of critical appraisal tools from which to choose. This is evidenced by the recent report by the Agency for Health Research Quality in which 93 critical appraisal tools for quantitative studies were identified [ 6 ]. Such choice may pose problems for research consumers, as dissimilar findings may well be the result when different critical appraisal tools are used to evaluate the same research report [ 6 ].

Critical appraisal tools can be broadly classified into those that are research design-specific and those that are generic. Design-specific tools contain items that address methodological issues that are unique to the research design [ 5 , 7 ]. This precludes comparison however of the quality of different study designs [ 8 ]. To attempt to overcome this limitation, generic critical appraisal tools have been developed, in an attempt to enhance the ability of research consumers to synthesise evidence from a range of quantitative and or qualitative study designs (for instance [ 9 ]). There is no evidence that generic critical appraisal tools and design-specific tools provide a comparative evaluation of research designs.

Moreover, there appears to be little consensus regarding the most appropriate items that should be contained within any critical appraisal tool. This paper is concerned primarily with critical appraisal tools that address the unique properties of allied health care and research [ 10 ]. This approach was taken because of the unique nature of allied health contacts with patients, and because evidence-based practice is an emerging area in allied health [ 10 ]. The availability of so many critical appraisal tools (for instance [ 6 ]) may well prove daunting for allied health practitioners who are learning to critically appraise research in their area of interest. For the purposes of this evaluation, allied health is defined as encompassing "...all occasions of service to non admitted patients where services are provided at units/clinics providing treatment/counseling to patients. These include units primarily concerned with physiotherapy, speech therapy, family panning, dietary advice, optometry occupational therapy..." [ 11 ].

The unique nature of allied health practice needs to be considered in allied health research. Allied health research thus differs from most medical research, with respect to:

• the paradigm underpinning comprehensive and clinically-reasoned descriptions of diagnosis (including validity and reliability). An example of this is in research into low back pain, where instead of diagnosis being made on location and chronicity of pain (as is common) [ 12 ], it would be made on the spinal structure and the nature of the dysfunction underpinning the symptoms, which is arrived at by a staged and replicable clinical reasoning process [ 10 , 13 ].

• the frequent use of multiple interventions within the one contact with the patient (an occasion of service), each of which requires appropriate description in terms of relationship to the diagnosis, nature, intensity, frequency, type of instruction provided to the patient, and the order in which the interventions were applied [ 13 ]

• the timeframe and frequency of contact with the patient (as many allied health disciplines treat patients in episodes of care that contain multiple occasions of service, and which can span many weeks, or even years in the case of chronic problems [ 14 ])

• measures of outcome, including appropriate methods and timeframes of measuring change in impairment, function, disability and handicap that address the needs of different stakeholders (patients, therapists, funders etc) [ 10 , 12 , 13 ].

Search strategy

In supplementary data [see additional file 1 ].

Data organization and extraction

Two independent researchers (PK, NMW) participated in all aspects of this review, and they compared and discussed their findings with respect to inclusion of critical appraisal tools, their intent, components, data extraction and item classification, construction and psychometric properties. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third member of the team (KG).

Data extraction consisted of a four-staged process. First, identical replica critical appraisal tools were identified and removed prior to analysis. The remaining critical appraisal tools were then classified according to the study design for which they were intended to be used [ 1 , 2 ]. The scientific manner in which the tools had been constructed was classified as whether an empirical research approach has been used, and if so, which type of research had been undertaken. Finally, the items contained in each critical appraisal tool were extracted and classified into one of eleven groups, which were based on the criteria described by Clarke and Oxman [ 4 ] as:

• Study aims and justification

• Methodology used , which encompassed method of identification of relevant studies and adherence to study protocol;

• Sample selection , which ranged from inclusion and exclusion criteria, to homogeneity of groups;

• Method of randomization and allocation blinding;

• Attrition : response and drop out rates;

• Blinding of the clinician, assessor, patient and statistician as well as the method of blinding;

• Outcome measure characteristics;

• Intervention or exposure details;

• Method of data analyses ;

• Potential sources of bias ; and

• Issues of external validity , which ranged from application of evidence to other settings to the relationship between benefits, cost and harm.

An additional group, " miscellaneous ", was used to describe items that could not be classified into any of the groups listed above.

Data synthesis

Data was synthesized using MS Excel spread sheets as well as narrative format by describing the number of critical appraisal tools per study design and the type of items they contained. Descriptions were made of the method by which the overall quality of the study was determined, evidence regarding the psychometric properties of the tools (validity and reliability) and whether guidelines were provided for use of the critical appraisal tool.

One hundred and ninety-three research reports that potentially provided a description of a critical appraisal tool (or process) were identified from the search strategy. Fifty-six of these papers were unavailable for review due to outdated Internet links, or inability to source the relevant journal through Australian university and Government library databases. Of the 127 papers retrieved, 19 were excluded from this review, as they did not provide a description of the critical appraisal tool used, or were published in languages other than English. As a result, 108 papers were reviewed, which yielded 121 different critical appraisal tools [ 1 – 5 , 7 , 9 , 15 – 102 , 116 ].

Empirical basis for tool construction

We identified 14 instruments (12% all tools) which were reported as having been constructed using a specified empirical approach [ 20 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 35 , 40 , 49 , 51 , 70 – 72 , 79 , 103 , 116 ]. The empirical research reflected descriptive and/or qualitative approaches, these being critical review of existing tools [ 40 , 72 ], Delphi techniques to identify then refine data items [ 32 , 51 , 71 ], questionnaires and other forms of written surveys to identify and refine data items [ 70 , 79 , 103 ], facilitated structured consensus meetings [ 20 , 29 , 30 , 35 , 40 , 49 , 70 , 72 , 79 , 116 ], and pilot validation testing [ 20 , 40 , 72 , 103 , 116 ]. In all the studies which reported developing critical appraisal tools using a consensus approach, a range of stakeholder input was sought, reflecting researchers and clinicians in a range of health disciplines, students, educators and consumers. There were a further 31 papers which cited other studies as the source of the tool used in the review, but which provided no information on why individual items had been chosen, or whether (or how) they had been modified. Moreover, for 21 of these tools, the cited sources of the critical appraisal tool did not report the empirical basis on which the tool had been constructed.

Critical appraisal tools per study design

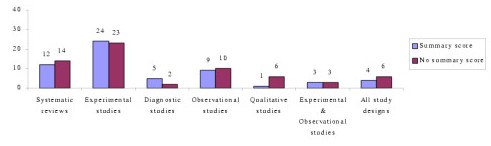

Seventy-eight percent (N = 94) of the critical appraisal tools were developed for use on primary research [ 1 – 5 , 7 , 9 , 18 , 19 , 25 – 27 , 34 , 37 – 41 ], while the remainder (N = 26) were for secondary research (systematic reviews and meta-analyses) [ 2 – 5 , 15 – 36 , 116 ]. Eighty-seven percent (N = 104) of all critical appraisal tools were design-specific [ 2 – 5 , 7 , 9 , 15 – 90 ], with over one third (N = 45) developed for experimental studies (randomized controlled trials, clinical trials) [ 2 – 4 , 25 – 27 , 34 , 37 – 73 ]. Sixteen critical appraisal tools were generic. Of these, six were developed for use on both experimental and observational studies [ 9 , 91 – 95 ], whereas 11 were purported to be useful for any qualitative and quantitative research design [ 1 , 18 , 41 , 96 – 102 , 116 ] (see Figure 1 , Table 1 ).

Number of critical appraisal tools per study design [1,2]

Critical appraisal items

One thousand, four hundred and seventy five items were extracted from these critical appraisal tools. After grouping like items together, 173 different item types were identified, with the most frequently reported items being focused towards assessing the external validity of the study (N = 35) and method of data analyses (N = 28) (Table 2 ). The most frequently reported items across all critical appraisal tools were:

Eligibility criteria (inclusion/exclusion criteria) (N = 63)

Appropriate statistical analyses (N = 47)

Random allocation of subjects (N = 43)

Consideration of outcome measures used (N = 43)

Sample size justification/power calculations (N = 39)

Study design reported (N = 36)

Assessor blinding (N = 36)

Design-specific critical appraisal tools

Systematic reviews.

Eighty-seven different items were extracted from the 26 critical appraisal tools, which were designed to evaluate the quality of systematic reviews. These critical appraisal tools frequently contained items regarding data analyses and issues of external validity (Tables 2 and 3 ).

Items assessing data analyses were focused to the methods used to summarize the results, assessment of sensitivity of results and whether heterogeneity was considered, whereas the nature of reporting of the main results, interpretation of them and their generalizability were frequently used to assess the external validity of the study findings. Moreover, systematic review critical appraisal tools tended to contain items such as identification of relevant studies, search strategy used, number of studies included and protocol adherence, that would not be relevant for other study designs. Blinding and randomisation procedures were rarely included in these critical appraisal tools.

Experimental studies

One hundred and twenty thirteen different items were extracted from the 45 experimental critical appraisal tools. These items most frequently assessed aspects of data analyses and blinding (Tables 1 and 2 ). Data analyses items were focused on whether appropriate statistical analysis was performed, whether a sample size justification or power calculation was provided and whether side effects of the intervention were recorded and analysed. Blinding was focused on whether the participant, clinician and assessor were blinded to the intervention.

Diagnostic studies

Forty-seven different items were extracted from the seven diagnostic critical appraisal tools. These items frequently addressed issues involving data analyses, external validity of results and sample selection that were specific to diagnostic studies (whether the diagnostic criteria were defined, definition of the "gold" standard, the calculation of sensitivity and specificity) (Tables 1 and 2 ).

Observational studies

Seventy-four different items were extracted from the 19 critical appraisal tools for observational studies. These items primarily focused on aspects of data analyses (see Tables 1 and 2 , such as whether confounders were considered in the analysis, whether a sample size justification or power calculation was provided and whether appropriate statistical analyses were preformed.

Qualitative studies

Thirty-six different items were extracted from the seven qualitative study critical appraisal tools. The majority of these items assessed issues regarding external validity, methods of data analyses and the aims and justification of the study (Tables 1 and 2 ). Specifically, items were focused to whether the study question was clearly stated, whether data analyses were clearly described and appropriate, and application of the study findings to the clinical setting. Qualitative critical appraisal tools did not contain items regarding sample selection, randomization, blinding, intervention or bias, perhaps because these issues are not relevant to the qualitative paradigm.

Generic critical appraisal tools

Experimental and observational studies.

Forty-two different items were extracted from the six critical appraisal tools that could be used to evaluate experimental and observational studies. These tools most frequently contained items that addressed aspects of sample selection (such as inclusion/exclusion criteria of participants, homogeneity of participants at baseline) and data analyses (such as whether appropriate statistical analyses were performed, whether a justification of the sample size or power calculation were provided).

All study designs

Seventy-eight different items were contained in the ten critical appraisal tools that could be used for all study designs (quantitative and qualitative). The majority of these items focused on whether appropriate data analyses were undertaken (such as whether confounders were considered in the analysis, whether a sample size justification or power calculation was provided and whether appropriate statistical analyses were preformed) and external validity issues (generalization of results to the population, value of the research findings) (see Tables 1 and 2 ).

Allied health critical appraisal tools

We found no critical appraisal instrument specific to allied health research, despite finding at least seven critical appraisal instruments associated with allied health topics (mostly physiotherapy management of orthopedic conditions) [ 37 , 39 , 52 , 58 , 59 , 65 ]. One critical appraisal development group proposed two instruments [ 9 ], specific to quantitative and qualitative research respectively. The core elements of allied health research quality (specific diagnosis criteria, intervention descriptions, nature of patient contact and appropriate outcome measures) were not addressed in any one tool sourced for this evaluation. We identified 152 different ways of considering quality reporting of outcome measures in the 121 critical appraisal tools, and 81 ways of considering description of interventions. Very few tools which were not specifically targeted to diagnostic studies (less than 10% of the remaining tools) addressed diagnostic criteria. The critical appraisal instrument that seemed most related to allied health research quality [ 39 ] sought comprehensive evaluation of elements of intervention and outcome, however this instrument was relevant only to physiotherapeutic orthopedic experimental research.

Overall study quality

Forty-nine percent (N = 58) of critical appraisal tools summarised the results of the quality appraisal into a single numeric summary score [ 5 , 7 , 15 – 25 , 37 – 59 , 74 – 77 , 80 – 83 , 87 , 91 – 93 , 96 , 97 ] (Figure 2 ). This was achieved by one of two methods:

Number of critical appraisal tools with, and without, summary quality scores

An equal weighting system, where one point was allocated to each item fulfilled; or

A weighted system, where fulfilled items were allocated various points depending on their perceived importance.

However, there was no justification provided for any of the scoring systems used. In the remaining critical appraisal tools (N = 62), a single numerical summary score was not provided [ 1 – 4 , 9 , 25 – 36 , 60 – 73 , 78 , 79 , 84 – 90 , 94 , 95 , 98 – 102 ]. This left the research consumer to summarize the results of the appraisal in a narrative manner, without the assistance of a standard approach.

Psychometric properties of critical appraisal tools

Few critical appraisal tools had documented evidence of their validity and reliability. Face validity was established in nine critical appraisal tools, seven of which were developed for use on experimental studies [ 38 , 40 , 45 , 49 , 51 , 63 , 70 ] and two for systematic reviews [ 32 , 103 ]. Intra-rater reliability was established for only one critical appraisal tool as part of its empirical development process [ 40 ], whereas inter-rater reliability was reported for two systematic review tools [ 20 , 36 ] (for one of these as part of the developmental process [ 20 ]) and seven experimental critical appraisal tools [ 38 , 40 , 45 , 51 , 55 , 56 , 63 ] (for two of these as part of the developmental process [ 40 , 51 ]).

Critical appraisal tool guidelines

Forty-three percent (N = 52) of critical appraisal tools had guidelines that informed the user of the interpretation of each item contained within them (Table 2 ). These guidelines were most frequently in the form of a handbook or published paper (N = 31) [ 2 , 4 , 9 , 15 , 20 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 36 , 37 , 41 , 50 , 64 – 67 , 69 , 80 , 84 – 87 , 89 , 90 , 95 , 100 , 116 ], whereas in 14 critical appraisal tools explanations accompanied each item [ 16 , 26 , 27 , 40 , 49 , 51 , 57 , 59 , 79 , 83 , 91 , 102 ].

Our search strategy identified a large number of published critical appraisal tools that are currently available to critically appraise research reports. There was a distinct lack of information on tool development processes in most cases. Many of the tools were reported to be modifications of other published tools, or reflected specialty concerns in specific clinical or research areas, without attempts to justify inclusion criteria. Less than 10 of these tools were relevant to evaluation of the quality of allied health research, and none of these were based on an empirical research approach. We are concerned that although our search was systematic and extensive [ 104 , 105 ], our broad key words and our lack of ready access to 29% of potentially useful papers (N = 56) potentially constrained us from identifying all published critical appraisal tools. However, consumers of research seeking critical appraisal instruments are not likely to seek instruments from outdated Internet links and unobtainable journals, thus we believe that we identified the most readily available instruments. Thus, despite the limitations on sourcing all possible tools, we believe that this paper presents a useful synthesis of the readily available critical appraisal tools.

The majority of the critical appraisal tools were developed for a specific research design (87%), with most designed for use on experimental studies (38% of all critical appraisal tools sourced). This finding is not surprising as, according to the medical model, experimental studies sit at or near the top of the hierarchy of evidence [ 2 , 8 ]. In recent years, allied health researchers have strived to apply the medical model of research to their own discipline by conducting experimental research, often by using the randomized controlled trial design [ 106 ]. This trend may be the reason for the development of experimental critical appraisal tools reported in allied health-specific research topics [ 37 , 39 , 52 , 58 , 59 , 65 ].

We also found a considerable number of critical appraisal tools for systematic reviews (N = 26), which reflects the trend to synthesize research evidence to make it relevant for clinicians [ 105 , 107 ]. Systematic review critical appraisal tools contained unique items (such as identification of relevant studies, search strategy used, number of studies included, protocol adherence) compared with tools used for primary studies, a reflection of the secondary nature of data synthesis and analysis.

In contrast, we identified very few qualitative study critical appraisal tools, despite the presence of many journal-specific guidelines that outline important methodological aspects required in a manuscript submitted for publication [ 108 – 110 ]. This finding may reflect the more traditional, quantitative focus of allied health research [ 111 ]. Alternatively, qualitative researchers may view the robustness of their research findings in different terms compared with quantitative researchers [ 112 , 113 ]. Hence the use of critical appraisal tools may be less appropriate for the qualitative paradigm. This requires further consideration.

Of the small number of generic critical appraisal tools, we found few that could be usefully applied (to any health research, and specifically to the allied health literature), because of the generalist nature of their items, variable interpretation (and applicability) of items across research designs, and/or lack of summary scores. Whilst these types of tools potentially facilitate the synthesis of evidence across allied health research designs for clinicians, their lack of specificity in asking the 'hard' questions about research quality related to research design also potentially precludes their adoption for allied health evidence-based practice. At present, the gold standard study design when synthesizing evidence is the randomized controlled trial [ 4 ], which underpins our finding that experimental critical appraisal tools predominated in the allied health literature [ 37 , 39 , 52 , 58 , 59 , 65 ]. However, as more systematic literature reviews are undertaken on allied health topics, it may become more accepted that evidence in the form of other research design types requires acknowledgement, evaluation and synthesis. This may result in the development of more appropriate and clinically useful allied health critical appraisal tools.

A major finding of our study was the volume and variation in available critical appraisal tools. We found no gold standard critical appraisal tool for any type of study design. Therefore, consumers of research are faced with frustrating decisions when attempting to select the most appropriate tool for their needs. Variable quality evaluations may be produced when different critical appraisal tools are used on the same literature [ 6 ]. Thus, interpretation of critical analysis must be carefully considered in light of the critical appraisal tool used.

The variability in the content of critical appraisal tools could be accounted for by the lack of any empirical basis of tool construction, established validity of item construction, and the lack of a gold standard against which to compare new critical tools. As such, consumers of research cannot be certain that the content of published critical appraisal tools reflect the most important aspects of the quality of studies that they assess [ 114 ]. Moreover, there was little evidence of intra- or inter-rater reliability of the critical appraisal tools. Coupled with the lack of protocols for use, this may mean that critical appraisers could interpret instrument items in different ways over repeated occasions of use. This may produce variable results [123].

Based on the findings of this evaluation, we recommend that consumers of research should carefully select critical appraisal tools for their needs. The selected tools should have published evidence of the empirical basis for their construction, validity of items and reliability of interpretation, as well as guidelines for use, so that the tools can be applied and interpreted in a standardized manner. Our findings highlight the need for consensus to be reached regarding the important and core items for critical appraisal tools that will produce a more standardized environment for critical appraisal of research evidence. As a consequence, allied health research will specifically benefit from having critical appraisal tools that reflect best practice research approaches which embed specific research requirements of allied health disciplines.

National Health and Medical Research Council: How to Review the Evidence: Systematic Identification and Review of the Scientific Literature. Canberra. 2000

Google Scholar

National Health and Medical Research Council: How to Use the Evidence: Assessment and Application of Scientific Evidence. Canberra. 2000

Joanna Briggs Institute. [ http://www.joannabriggs.edu.au ]

Clarke M, Oxman AD: Cochrane Reviewer's Handbook 4.2.0. 2003, Oxford: The Cochrane Collaboration

Crombie IK: The Pocket Guide to Critical Appraisal: A Handbook for Health Care Professionals. 1996, London: BMJ Publishing Group

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Systems to Rate the Strength of Scientific Evidence. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 47, Publication No. 02-E016. Rockville. 2002

Elwood JM: Critical Appraisal of Epidemiological Studies and Clinical Trials. 1998, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2

Sackett DL, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB: Evidence Based Medicine. How to Practice and Teach EBM. 2000, London: Churchill Livingstone

Critical literature reviews. [ http://www.cotfcanada.org/cotf_critical.htm ]

Bialocerkowski AE, Grimmer KA, Milanese SF, Kumar S: Application of current research evidence to clinical physiotherapy practice. J Allied Health Res Dec.

The National Health Data Dictionary – Version 10. http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/hwi/nhdd12/nhdd12-v1.pdf and http://www.aihw.gov.au/publications/hwi/nhdd12/nhdd12-v2.pdf

Grimmer K, Bowman P, Roper J: Episodes of allied health outpatient care: an investigation of service delivery in acute public hospital settings. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2000, 22 (1/2): 80-87.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Grimmer K, Milanese S, Bialocerkowski A: Clinical guidelines for low back pain: A physiotherapy perspective. Physiotherapy Canada. 2003, 55 (4): 1-9.

Grimmer KA, Milanese S, Bialocerkowski AE, Kumar S: Producing and implementing evidence in clinical practice: the therapies' dilemma. Physiotherapy. 2004,

Greenhalgh T: How to read a paper: papers that summarize other papers (systematic reviews and meta-analysis). BMJ. 1997, 315: 672-675.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Auperin A, Pignon J, Poynard T: Review article: critical review of meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials in hepatogastroenterology. Alimentary Pharmacol Therapeutics. 1997, 11: 215-225. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.131302000.x.

CAS Google Scholar

Barnes DE, Bero LA: Why review articles on the health effects of passive smoking reach different conclusions. J Am Med Assoc. 1998, 279: 1566-1570. 10.1001/jama.279.19.1566.

Beck CT: Use of meta-analysis as a teaching strategy in nursing research courses. J Nurs Educat. 1997, 36: 87-90.

Carruthers SG, Larochelle P, Haynes RB, Petrasovits A, Schiffrin EL: Report of the Canadian Hypertension Society Consensus Conference: 1. Introduction. Can Med Assoc J. 1993, 149: 289-293.

Oxman AD, Guyatt GH, Singer J, Goldsmith CH, Hutchinson BG, Milner RA, Streiner DL: Agreement among reviewers of review articles. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991, 44: 91-98. 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90205-N.

Sacks HS, Reitman D, Pagano D, Kupelnick B: Meta-analysis: an update. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. 1996, 63: 216-224.

Smith AF: An analysis of review articles published in four anaesthesia journals. Can J Anaesth. 1997, 44: 405-409.

L'Abbe KA, Detsky AS, O'Rourke K: Meta-analysis in clinical research. Ann Intern Med. 1987, 107: 224-233.

PubMed Google Scholar

Mulrow CD, Antonio S: The medical review article: state of the science. Ann Intern Med. 1987, 106: 485-488.

Continuing Professional Development: A Manual for SIGN Guideline Developers. [ http://www.sign.ac.uk ]

Learning and Development Public Health Resources Unit. [ http://www.phru.nhs.uk/ ]

FOCUS Critical Appraisal Tool. [ http://www.focusproject.org.uk ]

Cook DJ, Sackett DL, Spitzer WO: Methodologic guidelines for systematic reviews of randomized control trials in health care from the Potsdam Consultation on meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995, 48: 167-171. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00172-M.

Cranney A, Tugwell P, Shea B, Wells G: Implications of OMERACT outcomes in arthritis and osteoporosis for Cochrane metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 1997, 24: 1206-1207.

Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Sinclair JC, Hoyward R, Cook DJ, Cook RJ: User's guide to the medical literature. IX. A method for grading health care recommendations. J Am Med Assoc. 1995, 274: 1800-1804. 10.1001/jama.274.22.1800.

Gyorkos TW, Tannenbaum TN, Abrahamowicz M, Oxman AD, Scott EAF, Milson ME, Rasooli Iris, Frank JW, Riben PD, Mathias RG: An approach to the development of practice guidelines for community health interventions. Can J Public Health. 1994, 85: S8-13.

Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF: Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet. 1999, 354: 1896-1900. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04149-5.

Oxman AD, Cook DJ, Guyatt GH: Users' guides to the medical literature. VI. How to use an overview. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. J Am Med Assoc. 1994, 272: 1367-1371. 10.1001/jama.272.17.1367.

Pogue J, Yusuf S: Overcoming the limitations of current meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 1998, 351: 47-52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08461-4.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB: Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. J Am Med Assoc. 2000, 283: 2008-2012. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008.

Irwig L, Tosteson AN, Gatsonis C, Lau J, Colditz G, Chalmers TC, Mostellar F: Guidelines for meta-analyses evaluating diagnostic tests. Ann Intern Med. 1994, 120: 667-676.

Moseley AM, Herbert RD, Sherrington C, Maher CG: Evidence for physiotherapy practice: A survey of the Physiotherapy Evidence Database. Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 2002, 48: 43-50.

Cho MK, Bero LA: Instruments for assessing the quality of drug studies published in the medical literature. J Am Med Assoc. 1994, 272: 101-104. 10.1001/jama.272.2.101.

De Vet HCW, De Bie RA, Van der Heijden GJ, Verhagen AP, Sijpkes P, Kipschild PG: Systematic reviews on the basis of methodological criteria. Physiotherapy. 1997, 83: 284-289.

Downs SH, Black N: The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998, 52: 377-384.

Evans M, Pollock AV: A score system for evaluating random control clinical trials of prophylaxis of abdominal surgical wound infection. Br J Surg. 1985, 72: 256-260.

Fahey T, Hyde C, Milne R, Thorogood M: The type and quality of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in UK public health journals. J Public Health Med. 1995, 17: 469-474.

Gotzsche PC: Methodology and overt and hidden bias in reports of 196 double-blind trials of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Control Clin Trials. 1989, 10: 31-56. 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90017-2.

Imperiale TF, McCullough AJ: Do corticosteroids reduce mortality from alcoholic hepatitis? A meta-analysis of the randomized trials. Ann Int Med. 1990, 113: 299-307.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ: Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary?. Control Clin Trials. 1996, 17: 1-12. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4.

Khan KS, Daya S, Collins JA, Walter SD: Empirical evidence of bias in infertility research: overestimation of treatment effect in crossover trials using pregnancy as the outcome measure. Fertil Steril. 1996, 65: 939-945.

Kleijnen J, Knipschild P, ter Riet G: Clinical trials of homoeopathy. BMJ. 1991, 302: 316-323.

Liberati A, Himel HN, Chalmers TC: A quality assessment of randomized control trials of primary treatment of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1986, 4: 942-951.

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, for the CONSORT Group: The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. J Am Med Assoc. 2001, 285: 1987-1991. 10.1001/jama.285.15.1987.

Reisch JS, Tyson JE, Mize SG: Aid to the evaluation of therapeutic studies. Pediatrics. 1989, 84: 815-827.

Sindhu F, Carpenter L, Seers K: Development of a tool to rate the quality assessment of randomized controlled trials using a Delphi technique. J Advanced Nurs. 1997, 25: 1262-1268. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.19970251262.x.

Van der Heijden GJ, Van der Windt DA, Kleijnen J, Koes BW, Bouter LM: Steroid injections for shoulder disorders: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Br J Gen Pract. 1996, 46: 309-316.

Van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Bouter LM: Conservative treatment of acute and chronic nonspecific low back pain. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the most common interventions. Spine. 1997, 22: 2128-2156. 10.1097/00007632-199709150-00012.

Garbutt JC, West SL, Carey TS, Lohr KN, Crews FT: Pharmacotherapy for Alcohol Dependence. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 3, AHCPR Publication No. 99-E004. Rockville. 1999

Oremus M, Wolfson C, Perrault A, Demers L, Momoli F, Moride Y: Interarter reliability of the modified Jadad quality scale for systematic reviews of Alzheimer's disease drug trials. Dement Geriatr Cognit Disord. 2001, 12: 232-236. 10.1159/000051263.

Clark O, Castro AA, Filho JV, Djubelgovic B: Interrater agreement of Jadad's scale. Annual Cochrane Colloqium Abstracts. 2001, [ http://www.biomedcentral.com/abstracts/COCHRANE/1/op031 ]October Lyon

Jonas W, Anderson RL, Crawford CC, Lyons JS: A systematic review of the quality of homeopathic clinical trials. BMC Alternative Medicine. 2001, 1: 12-10.1186/1472-6882-1-12.

Van Tulder M, Malmivaara A, Esmail R, Koes B: Exercises therapy for low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration back review group. Spine. 2000, 25: 2784-2796. 10.1097/00007632-200011010-00011.

Van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Vlaeyen JWS, Linton SJ, Morley SJ, Assendelft WJJ: Behavioral treatment for chronic low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the cochrane back. Spine. 2000, 25: 2688-2699. 10.1097/00007632-200010150-00024.

Aronson N, Seidenfeld J, Samson DJ, Aronson N, Albertson PC, Bayoumi AM, Bennett C, Brown A, Garber ABA, Gere M, Hasselblad V, Wilt T, Ziegler MPHK, Pharm D: Relative Effectiveness and Cost Effectiveness of Methods of Androgen Suppression in the Treatment of Advanced Prostate Cancer. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 4, AHCPR Publication No.99-E0012. Rockville. 1999

Chalmers TC, Smith H, Blackburn B, Silverman B, Schroeder B, Reitman D, Ambroz A: A method for assessing the quality of a randomized control trial. Control Clin Trials. 1981, 2: 31-49. 10.1016/0197-2456(81)90056-8.

der Simonian R, Charette LJ, McPeek B, Mosteller F: Reporting on methods in clinical trials. New Eng J Med. 1982, 306: 1332-1337.

Detsky AS, Naylor CD, O'Rourke K, McGeer AJ, L'Abbe KA: Incorporating variations in the quality of individual randomized trials into meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992, 45: 255-265. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90085-2.

Goudas L, Carr DB, Bloch R, Balk E, Ioannidis JPA, Terrin MN: Management of Cancer Pain. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 35 (Contract 290-97-0019 to the New England Medical Center), AHCPR Publication No. 99-E004. Rockville. 2000

Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Cook DJ: Users' guides to the medical literature. II. How to use an article about therapy or prevention. A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. J Am Med Assoc. 1993, 270: 2598-2601. 10.1001/jama.270.21.2598.

Khan KS, Ter Riet G, Glanville J, Sowden AJ, Kleijnen J: Undertaking Systematic Reviews of Research on Effectiveness: Centre of Reviews and Dissemination's Guidance for Carrying Out or Commissioning Reviews: York. 2000

McNamara R, Bass EB, Marlene R, Miller J: Management of New Onset Atrial Fibrillation. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No.12, AHRQ Publication No. 01-E026. Rockville. 2001

Prendiville W, Elbourne D, Chalmers I: The effects of routine oxytocic administration in the management of the third stage of labour: an overview of the evidence from controlled trials. Br J Obstet Gynae Col. 1988, 95: 3-16.

Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG: Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. J Am Med Assoc. 1995, 273: 408-412. 10.1001/jama.273.5.408.

The Standards of Reporting Trials Group: A proposal for structured reporting of randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Assoc. 1994, 272: 1926-1931. 10.1001/jama.272.24.1926.

Verhagen AP, de Vet HC, de Bie RA, Kessels AGH, Boers M, Bouter LM, Knipschild PG: The Delphi list: a criteria list for quality assessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998, 51: 1235-1241. 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00131-0.

Zaza S, Wright-De Aguero LK, Briss PA, Truman BI, Hopkins DP, Hennessy MH, Sosin DM, Anderson L, Carande-Kullis VG, Teutsch SM, Pappaioanou M: Data collection instrument and procedure for systematic reviews in the guide to community preventive services. Task force on community preventive services. Am J Prevent Med. 2000, 18: 44-74. 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00122-1.

Haynes BB, Wilczynski N, McKibbon A, Walker CJ, Sinclair J: Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically sound studies in MEDLINE. J Am Informatics Assoc. 1994, 1: 447-458.

Greenhalgh T: How to read a paper: papers that report diagnostic or screening tests. BMJ. 1997, 315: 540-543.

Arroll B, Schechter MT, Sheps SB: The assessment of diagnostic tests: a comparison of medical literature in 1982 and 1985. J Gen Int Med. 1988, 3: 443-447.

Lijmer JG, Mol BW, Heisterkamp S, Bonsel GJ, Prins MH, van der Meulen JH, Bossuyt PM: Empirical evidence of design-related bias in studies of diagnostic tests. J Am Med Assoc. 1999, 282: 1061-1066. 10.1001/jama.282.11.1061.

Sheps SB, Schechter MT: The assessment of diagnostic tests. A survey of current medical research. J Am Med Assoc. 1984, 252: 2418-2422. 10.1001/jama.252.17.2418.

McCrory DC, Matchar DB, Bastian L, Dutta S, Hasselblad V, Hickey J, Myers MSE, Nanda K: Evaluation of Cervical Cytology. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 5, AHCPR Publication No.99-E010. Rockville. 1999

Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig LM, Lijmer JG, Moher D, Rennie D, DeVet HCW: Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative. Clin Chem. 2003, 49: 1-6. 10.1373/49.1.1.

Greenhalgh T: How to Read a Paper: Assessing the methodological quality of published papers. BMJ. 1997, 315: 305-308.

Angelillo I, Villari P: Residential exposure to electromagnetic fields and childhood leukaemia: a meta-analysis. Bull World Health Org. 1999, 77: 906-915.

Ariens G, Mechelen W, Bongers P, Bouter L, Van der Wal G: Physical risk factors for neck pain. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2000, 26: 7-19.

Hoogendoorn WE, van Poppel MN, Bongers PM, Koes BW, Bouter LM: Physical load during work and leisure time as risk factors for back pain. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1999, 25: 387-403.

Laupacis A, Wells G, Richardson WS, Tugwell P: Users' guides to the medical literature. V. How to use an article about prognosis. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. J Am Med Assoc. 1994, 272: 234-237. 10.1001/jama.272.3.234.

Levine M, Walter S, Lee H, Haines T, Holbrook A, Moyer V: Users' guides to the medical literature. IV. How to use an article about harm. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. J Am Med Assoc. 1994, 271: 1615-1619. 10.1001/jama.271.20.1615.

Carey TS, Boden SD: A critical guide to case series reports. Spine. 2003, 28: 1631-1634. 10.1097/00007632-200308010-00001.

Greenhalgh T, Taylor R: How to read a paper: papers that go beyond numbers (qualitative research). BMJ. 1997, 315: 740-743.

Hoddinott P, Pill R: A review of recently published qualitative research in general practice. More methodological questions than answers?. Fam Pract. 1997, 14: 313-319. 10.1093/fampra/14.4.313.

Mays N, Pope C: Quality research in health care: Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000, 320: 50-52. 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50.

Mays N, Pope C: Rigour and qualitative research. BMJ. 1995, 311: 109-112.

Colditz GA, Miller JN, Mosteller F: How study design affects outcomes in comparisons of therapy. I: Medical. Stats Med. 1989, 8: 441-454.

Turlik MA, Kushner D: Levels of evidence of articles in podiatric medical journals. J Am Pod Med Assoc. 2000, 90: 300-302.

Borghouts JAJ, Koes BW, Bouter LM: The clinical course and prognostic factors of non-specific neck pain: a systematic review. Pain. 1998, 77: 1-13. 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00058-X.

Spitzer WO, Lawrence V, Dales R, Hill G, Archer MC, Clark P, Abenhaim L, Hardy J, Sampalis J, Pinfold SP, Morgan PP: Links between passive smoking and disease: a best-evidence synthesis. A report of the working group on passive smoking. Clin Invest Med. 1990, 13: 17-46.

Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR, Sheldon TA, Song F: Systematic reviews of trials and other studies. Health Tech Assess. 1998, 2: 1-276.

Chestnut RM, Carney N, Maynard H, Patterson P, Mann NC, Helfand M: Rehabilitation for Traumatic Brain Injury. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 2, Agency for Health Care Research and Quality Publication No. 99-E006. Rockville. 1999

Lohr KN, Carey TS: Assessing best evidence: issues in grading the quality of studies for systematic reviews. Joint Commission J Qual Improvement. 1999, 25: 470-479.

Greer N, Mosser G, Logan G, Halaas GW: A practical approach to evidence grading. Joint Commission J Qual Improvement. 2000, 26: 700-712.

Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, Lohr KN, Mulrow CD, Teutsch SM, Atkins D: Current methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prevent Med. 2001, 20: 21-35. 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00261-6.

Anonymous: How to read clinical journals: IV. To determine etiology or causation. Can Med Assoc J. 1981, 124: 985-990.

Whitten PS, Mair FS, Haycox A, May CR, Williams TL, Hellmich S: Systematic review of cost effectiveness studies of telemedicine interventions. BMJ. 2002, 324: 1434-1437. 10.1136/bmj.324.7351.1434.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Forrest JL, Miller SA: Evidence-based decision making in action: Part 2-evaluating and applying the clinical evidence. J Contemp Dental Pract. 2002, 4: 42-52.

Oxman AD, Guyatt GH: Validation of an index of the quality of review articles. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991, 44: 1271-1278. 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90160-B.

Jones T, Evans D: Conducting a systematic review. Aust Crit Care. 2000, 13: 66-71.

Papadopoulos M, Rheeder P: How to do a systematic literature review. South African J Physiother. 2000, 56: 3-6.

Selker LG: Clinical research in Allied Health. J Allied Health. 1994, 23: 201-228.

Stevens KR: Systematic reviews: the heart of evidence-based practice. AACN Clin Issues. 2001, 12: 529-538.

Devers KJ, Frankel RM: Getting qualitative research published. Ed Health. 2001, 14: 109-117. 10.1080/13576280010021888.

Canadian Journal of Public Health: Review guidelines for qualitative research papers submitted for consideration to the Canadian Journal of Public Health. Can J Pub Health. 2000, 91: I2-

Malterud K: Shared understanding of the qualitative research process: guidelines for the medical researcher. Fam Pract. 1993, 10: 201-206.

Higgs J, Titchen A: Research and knowledge. Physiotherapy. 1998, 84: 72-80.

Maggs-Rapport F: Best research practice: in pursuit of methodological rigour. J Advan Nurs. 2001, 35: 373-383. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01853.x.

Cutcliffe JR, McKenna HP: Establishing the credibility of qualitative research findings: the plot thickens. J Advan Nurs. 1999, 30: 374-380. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01090.x.

Andresen EM: Criteria for assessing the tools of disability outcomes research. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2000, 81: S15-S20. 10.1053/apmr.2000.20619.

Beatie P: Measurement of health outcomes in the clinical setting: applications to physiotherapy. Phys Theory Pract. 2001, 17: 173-185. 10.1080/095939801317077632.

Charnock DF, (Ed): The DISCERN Handbook: Quality criteria for consumer health information on treatment choices. 1998, Radcliffe Medical Press

Pre-publication history