Report | Wages, Incomes, and Wealth

“Women’s work” and the gender pay gap : How discrimination, societal norms, and other forces affect women’s occupational choices—and their pay

Report • By Jessica Schieder and Elise Gould • July 20, 2016

Download PDF

Press release

Share this page:

What this report finds: Women are paid 79 cents for every dollar paid to men—despite the fact that over the last several decades millions more women have joined the workforce and made huge gains in their educational attainment. Too often it is assumed that this pay gap is not evidence of discrimination, but is instead a statistical artifact of failing to adjust for factors that could drive earnings differences between men and women. However, these factors—particularly occupational differences between women and men—are themselves often affected by gender bias. For example, by the time a woman earns her first dollar, her occupational choice is the culmination of years of education, guidance by mentors, expectations set by those who raised her, hiring practices of firms, and widespread norms and expectations about work–family balance held by employers, co-workers, and society. In other words, even though women disproportionately enter lower-paid, female-dominated occupations, this decision is shaped by discrimination, societal norms, and other forces beyond women’s control.

Why it matters, and how to fix it: The gender wage gap is real—and hurts women across the board by suppressing their earnings and making it harder to balance work and family. Serious attempts to understand the gender wage gap should not include shifting the blame to women for not earning more. Rather, these attempts should examine where our economy provides unequal opportunities for women at every point of their education, training, and career choices.

Introduction and key findings

Women are paid 79 cents for every dollar paid to men (Hegewisch and DuMonthier 2016). This is despite the fact that over the last several decades millions more women have joined the workforce and made huge gains in their educational attainment.

Critics of this widely cited statistic claim it is not solid evidence of economic discrimination against women because it is unadjusted for characteristics other than gender that can affect earnings, such as years of education, work experience, and location. Many of these skeptics contend that the gender wage gap is driven not by discrimination, but instead by voluntary choices made by men and women—particularly the choice of occupation in which they work. And occupational differences certainly do matter—occupation and industry account for about half of the overall gender wage gap (Blau and Kahn 2016).

To isolate the impact of overt gender discrimination—such as a woman being paid less than her male coworker for doing the exact same job—it is typical to adjust for such characteristics. But these adjusted statistics can radically understate the potential for gender discrimination to suppress women’s earnings. This is because gender discrimination does not occur only in employers’ pay-setting practices. It can happen at every stage leading to women’s labor market outcomes.

Take one key example: occupation of employment. While controlling for occupation does indeed reduce the measured gender wage gap, the sorting of genders into different occupations can itself be driven (at least in part) by discrimination. By the time a woman earns her first dollar, her occupational choice is the culmination of years of education, guidance by mentors, expectations set by those who raised her, hiring practices of firms, and widespread norms and expectations about work–family balance held by employers, co-workers, and society. In other words, even though women disproportionately enter lower-paid, female-dominated occupations, this decision is shaped by discrimination, societal norms, and other forces beyond women’s control.

This paper explains why gender occupational sorting is itself part of the discrimination women face, examines how this sorting is shaped by societal and economic forces, and explains that gender pay gaps are present even within occupations.

Key points include:

- Gender pay gaps within occupations persist, even after accounting for years of experience, hours worked, and education.

- Decisions women make about their occupation and career do not happen in a vacuum—they are also shaped by society.

- The long hours required by the highest-paid occupations can make it difficult for women to succeed, since women tend to shoulder the majority of family caretaking duties.

- Many professions dominated by women are low paid, and professions that have become female-dominated have become lower paid.

This report examines wages on an hourly basis. Technically, this is an adjusted gender wage gap measure. As opposed to weekly or annual earnings, hourly earnings ignore the fact that men work more hours on average throughout a week or year. Thus, the hourly gender wage gap is a bit smaller than the 79 percent figure cited earlier. This minor adjustment allows for a comparison of women’s and men’s wages without assuming that women, who still shoulder a disproportionate amount of responsibilities at home, would be able or willing to work as many hours as their male counterparts. Examining the hourly gender wage gap allows for a more thorough conversation about how many factors create the wage gap women experience when they cash their paychecks.

Within-occupation gender wage gaps are large—and persist after controlling for education and other factors

Those keen on downplaying the gender wage gap often claim women voluntarily choose lower pay by disproportionately going into stereotypically female professions or by seeking out lower-paid positions. But even when men and women work in the same occupation—whether as hairdressers, cosmetologists, nurses, teachers, computer engineers, mechanical engineers, or construction workers—men make more, on average, than women (CPS microdata 2011–2015).

As a thought experiment, imagine if women’s occupational distribution mirrored men’s. For example, if 2 percent of men are carpenters, suppose 2 percent of women become carpenters. What would this do to the wage gap? After controlling for differences in education and preferences for full-time work, Goldin (2014) finds that 32 percent of the gender pay gap would be closed.

However, leaving women in their current occupations and just closing the gaps between women and their male counterparts within occupations (e.g., if male and female civil engineers made the same per hour) would close 68 percent of the gap. This means examining why waiters and waitresses, for example, with the same education and work experience do not make the same amount per hour. To quote Goldin:

Another way to measure the effect of occupation is to ask what would happen to the aggregate gender gap if one equalized earnings by gender within each occupation or, instead, evened their proportions for each occupation. The answer is that equalizing earnings within each occupation matters far more than equalizing the proportions by each occupation. (Goldin 2014)

This phenomenon is not limited to low-skilled occupations, and women cannot educate themselves out of the gender wage gap (at least in terms of broad formal credentials). Indeed, women’s educational attainment outpaces men’s; 37.0 percent of women have a college or advanced degree, as compared with 32.5 percent of men (CPS ORG 2015). Furthermore, women earn less per hour at every education level, on average. As shown in Figure A , men with a college degree make more per hour than women with an advanced degree. Likewise, men with a high school degree make more per hour than women who attended college but did not graduate. Even straight out of college, women make $4 less per hour than men—a gap that has grown since 2000 (Kroeger, Cooke, and Gould 2016).

Women earn less than men at every education level : Average hourly wages, by gender and education, 2015

The data below can be saved or copied directly into Excel.

The data underlying the figure.

Source : EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

Copy the code below to embed this chart on your website.

Steering women to certain educational and professional career paths—as well as outright discrimination—can lead to different occupational outcomes

The gender pay gap is driven at least in part by the cumulative impact of many instances over the course of women’s lives when they are treated differently than their male peers. Girls can be steered toward gender-normative careers from a very early age. At a time when parental influence is key, parents are often more likely to expect their sons, rather than their daughters, to work in science, technology, engineering, or mathematics (STEM) fields, even when their daughters perform at the same level in mathematics (OECD 2015).

Expectations can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. A 2005 study found third-grade girls rated their math competency scores much lower than boys’, even when these girls’ performance did not lag behind that of their male counterparts (Herbert and Stipek 2005). Similarly, in states where people were more likely to say that “women [are] better suited for home” and “math is for boys,” girls were more likely to have lower math scores and higher reading scores (Pope and Sydnor 2010). While this only establishes a correlation, there is no reason to believe gender aptitude in reading and math would otherwise be related to geography. Parental expectations can impact performance by influencing their children’s self-confidence because self-confidence is associated with higher test scores (OECD 2015).

By the time young women graduate from high school and enter college, they already evaluate their career opportunities differently than young men do. Figure B shows college freshmen’s intended majors by gender. While women have increasingly gone into medical school and continue to dominate the nursing field, women are significantly less likely to arrive at college interested in engineering, computer science, or physics, as compared with their male counterparts.

Women arrive at college less interested in STEM fields as compared with their male counterparts : Intent of first-year college students to major in select STEM fields, by gender, 2014

Source: EPI adaptation of Corbett and Hill (2015) analysis of Eagan et al. (2014)

These decisions to allow doors to lucrative job opportunities to close do not take place in a vacuum. Many factors might make it difficult for a young woman to see herself working in computer science or a similarly remunerative field. A particularly depressing example is the well-publicized evidence of sexism in the tech industry (Hewlett et al. 2008). Unfortunately, tech isn’t the only STEM field with this problem.

Young women may be discouraged from certain career paths because of industry culture. Even for women who go against the grain and pursue STEM careers, if employers in the industry foster an environment hostile to women’s participation, the share of women in these occupations will be limited. One 2008 study found that “52 percent of highly qualified females working for SET [science, technology, and engineering] companies quit their jobs, driven out by hostile work environments and extreme job pressures” (Hewlett et al. 2008). Extreme job pressures are defined as working more than 100 hours per week, needing to be available 24/7, working with or managing colleagues in multiple time zones, and feeling pressure to put in extensive face time (Hewlett et al. 2008). As compared with men, more than twice as many women engage in housework on a daily basis, and women spend twice as much time caring for other household members (BLS 2015). Because of these cultural norms, women are less likely to be able to handle these extreme work pressures. In addition, 63 percent of women in SET workplaces experience sexual harassment (Hewlett et al. 2008). To make matters worse, 51 percent abandon their SET training when they quit their job. All of these factors play a role in steering women away from highly paid occupations, particularly in STEM fields.

The long hours required for some of the highest-paid occupations are incompatible with historically gendered family responsibilities

Those seeking to downplay the gender wage gap often suggest that women who work hard enough and reach the apex of their field will see the full fruits of their labor. In reality, however, the gender wage gap is wider for those with higher earnings. Women in the top 95th percentile of the wage distribution experience a much larger gender pay gap than lower-paid women.

Again, this large gender pay gap between the highest earners is partially driven by gender bias. Harvard economist Claudia Goldin (2014) posits that high-wage firms have adopted pay-setting practices that disproportionately reward individuals who work very long and very particular hours. This means that even if men and women are equally productive per hour, individuals—disproportionately men—who are more likely to work excessive hours and be available at particular off-hours are paid more highly (Hersch and Stratton 2002; Goldin 2014; Landers, Rebitzer, and Taylor 1996).

It is clear why this disadvantages women. Social norms and expectations exert pressure on women to bear a disproportionate share of domestic work—particularly caring for children and elderly parents. This can make it particularly difficult for them (relative to their male peers) to be available at the drop of a hat on a Sunday evening after working a 60-hour week. To the extent that availability to work long and particular hours makes the difference between getting a promotion or seeing one’s career stagnate, women are disadvantaged.

And this disadvantage is reinforced in a vicious circle. Imagine a household where both members of a male–female couple have similarly demanding jobs. One partner’s career is likely to be prioritized if a grandparent is hospitalized or a child’s babysitter is sick. If the past history of employer pay-setting practices that disadvantage women has led to an already-existing gender wage gap for this couple, it can be seen as “rational” for this couple to prioritize the male’s career. This perpetuates the expectation that it always makes sense for women to shoulder the majority of domestic work, and further exacerbates the gender wage gap.

Female-dominated professions pay less, but it’s a chicken-and-egg phenomenon

Many women do go into low-paying female-dominated industries. Home health aides, for example, are much more likely to be women. But research suggests that women are making a logical choice, given existing constraints . This is because they will likely not see a significant pay boost if they try to buck convention and enter male-dominated occupations. Exceptions certainly exist, particularly in the civil service or in unionized workplaces (Anderson, Hegewisch, and Hayes 2015). However, if women in female-dominated occupations were to go into male-dominated occupations, they would often have similar or lower expected wages as compared with their female counterparts in female-dominated occupations (Pitts 2002). Thus, many women going into female-dominated occupations are actually situating themselves to earn higher wages. These choices thereby maximize their wages (Pitts 2002). This holds true for all categories of women except for the most educated, who are more likely to earn more in a male profession than a female profession. There is also evidence that if it becomes more lucrative for women to move into male-dominated professions, women will do exactly this (Pitts 2002). In short, occupational choice is heavily influenced by existing constraints based on gender and pay-setting across occupations.

To make matters worse, when women increasingly enter a field, the average pay in that field tends to decline, relative to other fields. Levanon, England, and Allison (2009) found that when more women entered an industry, the relative pay of that industry 10 years later was lower. Specifically, they found evidence of devaluation—meaning the proportion of women in an occupation impacts the pay for that industry because work done by women is devalued.

Computer programming is an example of a field that has shifted from being a very mixed profession, often associated with secretarial work in the past, to being a lucrative, male-dominated profession (Miller 2016; Oldenziel 1999). While computer programming has evolved into a more technically demanding occupation in recent decades, there is no skills-based reason why the field needed to become such a male-dominated profession. When men flooded the field, pay went up. In contrast, when women became park rangers, pay in that field went down (Miller 2016).

Further compounding this problem is that many professions where pay is set too low by market forces, but which clearly provide enormous social benefits when done well, are female-dominated. Key examples range from home health workers who care for seniors, to teachers and child care workers who educate today’s children. If closing gender pay differences can help boost pay and professionalism in these key sectors, it would be a huge win for the economy and society.

The gender wage gap is real—and hurts women across the board. Too often it is assumed that this gap is not evidence of discrimination, but is instead a statistical artifact of failing to adjust for factors that could drive earnings differences between men and women. However, these factors—particularly occupational differences between women and men—are themselves affected by gender bias. Serious attempts to understand the gender wage gap should not include shifting the blame to women for not earning more. Rather, these attempts should examine where our economy provides unequal opportunities for women at every point of their education, training, and career choices.

— This paper was made possible by a grant from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

— The authors wish to thank Josh Bivens, Barbara Gault, and Heidi Hartman for their helpful comments.

About the authors

Jessica Schieder joined EPI in 2015. As a research assistant, she supports the research of EPI’s economists on topics such as the labor market, wage trends, executive compensation, and inequality. Prior to joining EPI, Jessica worked at the Center for Effective Government (formerly OMB Watch) as a revenue and spending policies analyst, where she examined how budget and tax policy decisions impact working families. She holds a bachelor’s degree in international political economy from Georgetown University.

Elise Gould , senior economist, joined EPI in 2003. Her research areas include wages, poverty, economic mobility, and health care. She is a co-author of The State of Working America, 12th Edition . In the past, she has authored a chapter on health in The State of Working America 2008/09; co-authored a book on health insurance coverage in retirement; published in venues such as The Chronicle of Higher Education , Challenge Magazine , and Tax Notes; and written for academic journals including Health Economics , Health Affairs, Journal of Aging and Social Policy, Risk Management & Insurance Review, Environmental Health Perspectives , and International Journal of Health Services . She holds a master’s in public affairs from the University of Texas at Austin and a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Anderson, Julie, Ariane Hegewisch, and Jeff Hayes 2015. The Union Advantage for Women . Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn 2016. The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations . National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 21913.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). 2015. American Time Use Survey public data series. U.S. Census Bureau.

Corbett, Christianne, and Catherine Hill. 2015. Solving the Equation: The Variables for Women’s Success in Engineering and Computing . American Association of University Women (AAUW).

Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata (CPS ORG). 2011–2015. Survey conducted by the Bureau of the Census for the Bureau of Labor Statistics [ machine-readable microdata file ]. U.S. Census Bureau.

Goldin, Claudia. 2014. “ A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter .” American Economic Review, vol. 104, no. 4, 1091–1119.

Hegewisch, Ariane, and Asha DuMonthier. 2016. The Gender Wage Gap: 2015; Earnings Differences by Race and Ethnicity . Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Herbert, Jennifer, and Deborah Stipek. 2005. “The Emergence of Gender Difference in Children’s Perceptions of Their Academic Competence.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology , vol. 26, no. 3, 276–295.

Hersch, Joni, and Leslie S. Stratton. 2002. “ Housework and Wages .” The Journal of Human Resources , vol. 37, no. 1, 217–229.

Hewlett, Sylvia Ann, Carolyn Buck Luce, Lisa J. Servon, Laura Sherbin, Peggy Shiller, Eytan Sosnovich, and Karen Sumberg. 2008. The Athena Factor: Reversing the Brain Drain in Science, Engineering, and Technology . Harvard Business Review.

Kroeger, Teresa, Tanyell Cooke, and Elise Gould. 2016. The Class of 2016: The Labor Market Is Still Far from Ideal for Young Graduates . Economic Policy Institute.

Landers, Renee M., James B. Rebitzer, and Lowell J. Taylor. 1996. “ Rat Race Redux: Adverse Selection in the Determination of Work Hours in Law Firms .” American Economic Review , vol. 86, no. 3, 329–348.

Levanon, Asaf, Paula England, and Paul Allison. 2009. “Occupational Feminization and Pay: Assessing Causal Dynamics Using 1950-2000 U.S. Census Data.” Social Forces, vol. 88, no. 2, 865–892.

Miller, Claire Cain. 2016. “As Women Take Over a Male-Dominated Field, the Pay Drops.” New York Times , March 18.

Oldenziel, Ruth. 1999. Making Technology Masculine: Men, Women, and Modern Machines in America, 1870-1945 . Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2015. The ABC of Gender Equality in Education: Aptitude, Behavior, Confidence .

Pitts, Melissa M. 2002. Why Choose Women’s Work If It Pays Less? A Structural Model of Occupational Choice. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Working Paper 2002-30.

Pope, Devin G., and Justin R. Sydnor. 2010. “ Geographic Variation in the Gender Differences in Test Scores .” Journal of Economic Perspectives , vol. 24, no. 2, 95–108.

See related work on Wages, Incomes, and Wealth | Women

See more work by Jessica Schieder and Elise Gould

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

It's Equal Pay Day. The gender pay gap has hardly budged in 20 years. What gives?

Stacey Vanek Smith

Women earn about 82 cents for every dollar men make, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office. That means on March 14, women's pay catches up to what men made in 2022. Klaus Vedfelt/Getty Images hide caption

Women earn about 82 cents for every dollar men make, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office. That means on March 14, women's pay catches up to what men made in 2022.

Tuesday is Equal Pay Day: March 14th represents how far into the year women have had to work to catch up to what their male colleagues earned the previous year.

In other words, women have to work nearly 15 months to earn what men make in 12 months.

82 cents on the dollar, and less for women of color

This is usually referred to as the gender pay gap. Here are the numbers: - Women earn about 82 cents for every dollar a man earns - For Black women, it's about 65 cents - For Latina women, it's about 60 cents

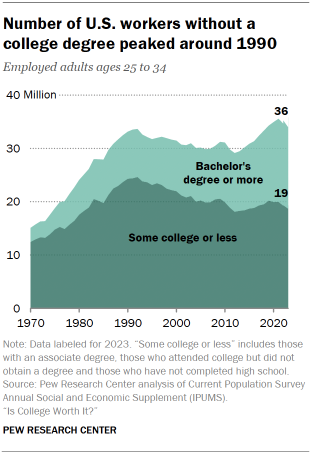

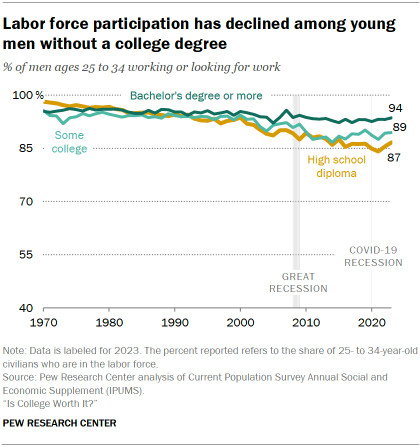

Those gaps widen when comparing what women of color earn to the salaries of White men . These numbers have basically not budged in 20 years . That's particularly strange because so many other things have changed:

- More women now graduate from college than men - More women graduate from law school than men - Medical school graduates are roughly half women

That should be seen as progress. So why hasn't the pay gap improved too?

On Equal Pay Day, women are trying to make a dollar out of 83 cents

Francine Blau, an economist at Cornell who has been studying the gender pay gap for decades, calls this the $64,000 question. "Although if you adjust for inflation, it's probably in the millions by now," she jokes.

The Indicator from Planet Money

Women, career and family: a conversation with claudia goldin, the childcare conundrum.

Blau says one of the biggest factors here is childcare. Many women shy away from really demanding positions or work only part time because they need time and flexibility to care for their kids . "Women will choose jobs or switch to occupations or companies that are more family friendly," she explains. "But a lot of times those jobs will pay less." Other women leave the workforce entirely. For every woman at a senior management level who gets promoted, two women leave their jobs , most citing childcare as a major reason.

The "unexplained pay gap"

Even if you account for things like women taking more flexible jobs, working fewer hours, taking time off for childcare, etc., paychecks between the sexes still aren't square. Blau and her research partner Lawrence Kahn controlled for "everything we could find reliable data on" and found that women still earn about 8% less than their male colleagues for the same job .

"It's what we call the 'unexplained pay gap,'" says Blau, then laughs. "Or, you could just call it discrimination."

Planet Money

Mind the pay gap, mend the gap.

One way women could narrow the unexplained pay gap is, of course, to negotiate for higher salaries. But Blau points out that women are likely to experience backlash when they ask for more money. And it can be hard to know how much their male colleagues make and, therefore, what to ask for.

That is changing: a handful of states now require salary ranges be included in job postings.

The big reveal: New laws require companies to disclose pay ranges on job postings.

Blau says that information can be a game changer at work for women and other marginalized groups: "They can get a real sense of, 'Oh, this is the bottom of the range and this is the top of the range. What's reasonable to ask for?'"

A pay raise, if the data is any indication.

Where there's gender equality, people tend to live longer

Everything you need to know about pushing for pay equity

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to E-mail

Workers worldwide look forward to payday. But while a paycheck may bring a sense of relief, satisfaction, or joy, it can also represent an injustice—a stark reminder of persistent inequalities between men and women in the workplace.

The gender pay gap stands at 20 per cent , meaning women workers earn 80 per cent of what men do. For women of colour, migrant women, those with disabilities, and women with children, the gap is even greater.

The cumulative effect of pay disparities has real, daily negative consequences for women, their families, and society, especially during crises. The widespread effects of COVID-19 have plunged up to 95 million people into extreme poverty, with one in every 10 women globally living in extreme poverty . If current trends continue, 342.4 million women and girls will be living on less than $2.15 a day by 2030.

What do we mean by equal pay for work of equal value?

Equal pay for work of equal value, as defined by the ILO Equal Remuneration Convention , means that all workers are entitled to receive equal remuneration not only for identical tasks but also for different work considered of equal value. This distinction is crucial because jobs held by women and men may involve varying qualifications, skills, responsibilities, or working conditions, yet hold equal value and warrant equal pay.

In 2020, New Zealand passed the Equal Pay Amendment Bill , ensuring that women and men are paid equally for work that’s different but has equal value, including in chronically underpaid female-dominated industries.

It is also important to recognize that remuneration is more than a basic wage; it encompasses all the elements of earnings. This includes overtime pay, bonuses, travel allowances, company shares, insurance, and other benefits.

Why does the gender pay gap persist?

The gender pay gap originates from ingrained inequalities. Women, particularly migrant women, are overrepresented in the informal sector. Look around you, from street vending to domestic service, from coffee shop attendants to subsistence farming. Women fill informal jobs that often fall outside the domains of labour laws, trapping them in low-paying, unsafe working environments, without social benefits. These poor conditions for women workers perpetuate the gender pay gap.

Women also do three more hours of daily care work than men , globally. This includes household tasks such as cooking, cleaning, fetching firewood and water, and taking care of children and the elderly. Although care work is the backbone of thriving families, communities, and economies, it remains undervalued and underrecognized. Try calculating your daily load with UN Women’s unpaid care calculator .

The motherhood penalty exacerbates pay inequity, with working mothers facing lower wages, a disparity that jumps as the number of children a woman has increases. Lower wages for mothers are linked to reduced working time, employment in more family-friendly jobs that tend to be lower paying, hiring and promotion decisions that penalize the careers of mothers, and a lack of programmes to support women’s return to work after time out of the labour market.

Restrictive, traditional gender roles are also spurring pay inequalities. Gender stereotypes steer women away from occupations traditionally dominated by men and push them toward care-focused work that is often regarded as “unskilled,” or “soft-skilled” and therefore, lower paid.

Furthermore, discriminatory hiring practices and promotion decisions that prevent women from gaining leadership roles and highly paid positions sustain the gender pay gap.

Why is pay equity an urgent issue?

Pay equity matters because it is a glaring injustice and subjects millions of women and families to lives of entrenched poverty and opportunity gaps. At the current rate, we risk leaving more than 340 million women and girls in abject poverty by 2030 , and an alarming 4 per cent could grapple with extreme food insecurity by that year.

Women also experience significantly lower social protection coverage than men, a discrepancy that largely reflects and reproduces their lower labour force participation rates, higher levels of temporary and precarious work, and informal employment. All these factors contribute to lower income , savings, and pensions of women and gendered poverty in old age.

What should be done?

As more women are plunged into poverty, the fight for equal pay and pay equity takes on a new sense of urgency because those who earn the least are most damaged by income discrepancy.

In the United States, Black women earn only 63.7 cents , Native women 59 cents , and Latinas 57 cents for every dollar that white men earn. Where money is tight, lower pay can prevent women and families from putting food on the table, securing safe housing, and accessing critical medical care and education—impacts that can perpetuate cycles of poverty across generations.

It is urgent that we put female workers on equal footing as male workers. In a world on the brink of a looming care deficit, women make up 67 per cent of workers providing essential health and social care services globally . Governments must address underpaid and undervalued jobs in the care sector, including in education, health care and social services, all jobs that women predominantly occupy.

What does the data say about pay equity around the world?

Unequal pay is a stubborn and universal problem. Despite significant progress in women’s education and labour market participation, progress in closing the gender pay gap has been too slow. At this pace, it will take almost 300 years to achieve economic gender parity .

Women workers’ average pay is generally lower than men’s in all countries and for all levels of education, and age groups, with women earning on average 80 per cent what men ear n. Women in male-dominated industries may earn more than those in female-dominated industries, but the gender pay gap persists across all sectors.

While gender pay gap estimates can vary substantially across regions and even within countries, higher income countries tend to have lower levels of wage inequality compared to low and middle-income countries. However, estimates of the gender pay gap understate the real extent of the issue, particularly in developing countries, because of a lack of information about informal economies, which are disproportionately made up of women workers, so the full picture is likely worse than what the available data shows us.

Explore UN Women’s report on the gender pay gap in Eastern and Southern Africa .

Closing the gender pay gap requires a set of measures that push for decent work for all people. This includes measures that promote the formalization of the informal economy, bringing informal workers under the umbrella of legal and effective protection and empowering them to better defend their interests.

Ensuring workers’ right to organize and bargain collectively is an important part of the solution. Women must be involved in employer and union leadership, enabling legislation that establishes comprehensive frameworks for gender equality in the workplace.

Economic empowerment Chief at UN Women Dr. Jemimah Njuki says that, “The gender pay gap requires all stakeholders, including employers, governments, trade unions take full responsibility and work side by side to address these challenges. Women deserve equal pay for work of equal value”.

[Last updated February 2024]

- Gender-responsive procurement

- Gender wage gap

Related content

Op-ed: Improving women’s access to decent jobs

Speech: Ambitiously proactive – Generation Equality brings hope to stalled progress and financing

EntreprenHER programme empowers women entrepreneurs in Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa

Economic Inequality by Gender

How big are the inequalities in pay, jobs, and wealth between men and women? What causes these differences?

By: Esteban Ortiz-Ospina , Joe Hasell and Max Roser

This page was first published in March 2018 and last revised in March 2024.

On this page, you can find writing, visualizations, and data on how big the inequalities in pay, jobs, and wealth are between men and women, how they have changed over time, and what may be causing them

Although economic gender inequalities remain common and large, they are today smaller than they used to be some decades ago.

Related topics

Women's Employment

How does women’s labor force participation differ across countries? How has it changed over time? What is behind these differences and changes?

Women’s Rights

How has the protection of women’s rights changed over time? How does it differ across countries? Explore global data and research on women’s rights.

Maternal Mortality

What could be more tragic than a mother losing her life in the moment that she is giving birth to her newborn? Why are mothers dying and what can be done to prevent these deaths?

See all interactive charts on economic inequality by gender ↓

How does the gender pay gap look like across countries and over time?

The 'gender pay gap' comes up often in political debates , policy reports , and everyday news . But what is it? What does it tell us? Is it different from country to country? How does it change over time?

Here we try to answer these questions, providing an empirical overview of the gender pay gap across countries and over time.

The gender pay gap measures inequality but not necessarily discrimination

The gender pay gap (or the gender wage gap) is a metric that tells us the difference in pay (or wages, or income) between women and men. It's a measure of inequality and captures a concept that is broader than the concept of equal pay for equal work.

Differences in pay between men and women capture differences along many possible dimensions, including worker education, experience, and occupation. When the gender pay gap is calculated by comparing all male workers to all female workers – irrespective of differences along these additional dimensions – the result is the 'raw' or 'unadjusted' pay gap. On the contrary, when the gap is calculated after accounting for underlying differences in education, experience, etc., then the result is the 'adjusted' pay gap.

Discrimination in hiring practices can exist in the absence of pay gaps – for example, if women know they will be treated unfairly and hence choose not to participate in the labor market. Similarly, it is possible to observe large pay gaps in the absence of discrimination in hiring practices – for example, if women get fair treatment but apply for lower-paid jobs.

The implication is that observing differences in pay between men and women is neither necessary nor sufficient to prove discrimination in the workplace. Both discrimination and inequality are important. But they are not the same.

In most countries, there is a substantial gender pay gap

Cross-country data on the gender pay gap is patchy, but the most complete source in terms of coverage is the United Nation's International Labour Organization (ILO). The visualization here presents this data. You can add observations by clicking on the option 'add country' at the bottom of the chart.

The estimates shown here correspond to differences between the average hourly earnings of men and women (expressed as a percentage of average hourly earnings of men), and cover all workers irrespective of whether they work full-time or part-time. 1

As we can see: (i) in most countries the gap is positive – women earn less than men, and (ii) there are large differences in the size of this gap across countries. 2

In most countries, the gender pay gap has decreased in the last couple of decades

How is the gender pay gap changing over time? To answer this question, let's consider this chart showing available estimates from the OECD. These estimates include OECD member states, as well as some other non-member countries, and they are the longest available series of cross-country data on the gender pay gap that we are aware of.

Here we see that the gap is large in most OECD countries, but it has been going down in the last couple of decades. In some cases the reduction is remarkable. In the United States, for example, the gap declined by more than half.

These estimates are not directly comparable to those from the ILO, because the pay gap is measured slightly differently here: The OECD estimates refer to percent differences in median earnings (i.e. the gap here captures differences between men and women in the middle of the earnings distribution), and they cover only full-time employees and self-employed workers (i.e. the gap here excludes disparities that arise from differences in hourly wages for part-time and full-time workers).

However, the ILO data shows similar trends.

The conclusion is that in most countries with available data, the gender pay gap has decreased in the last couple of decades.

The gender pay gap is larger for older workers

The United States Census Bureau defines the pay gap as the ratio between median wages – that is, they measure the gap by calculating the wages of men and women at the middle of the earnings distribution, and dividing them.

By this measure, the gender wage gap is expressed as a percent (median earnings of women as a share of median earnings of men) and it is always positive. Here, values below 100% mean that women earn less than men, while values above 100% mean that women earn more. Values closer to 100% reflect a lower gap.

The next chart shows available estimates of this metric for full-time workers in the US, by age group.

First, we see that the series trends upwards, meaning the gap has been shrinking in the last couple of decades. Secondly, we see that there are important differences by age.

The second point is crucial to understanding the gender pay gap: the gap is a statistic that changes during the life of a worker. In most rich countries, it’s small when formal education ends and employment begins, and it increases with age. As we discuss in our analysis of the determinants below, the gender pay gap tends to increase when women marry and when/if they have children.

The gender pay gap is smaller in middle-income countries – which tend to be countries with low labor force participation of women

The chart here plots available ILO estimates on the gender pay gap against GDP per capita. As we can see there is a weak positive correlation between GDP per capita and the gender pay gap. However, the chart shows that the relationship is not really linear. Actually, middle-income countries tend to have the smallest pay gap.

The fact that middle-income countries have low gender wage gaps is, to a large extent, the result of selection of women into employment . Olivetti and Petrongolo (2008) explain it as follows: “[I]f women who are employed tend to have relatively high‐wage characteristics, low female employment rates may become consistent with low gender wage gaps simply because low‐wage women would not feature in the observed wage distribution.” 3

Olivetti and Petrongolo (2008) show that this pattern holds in the data: unadjusted gender wage gaps across countries tend to be negatively correlated with gender employment gaps. That is, the gender pay gaps tend to be smaller where relatively fewer women participate in the labor force .

So, rather than reflect greater equality, the lower wage gaps observed in some countries could indicate that only women with certain characteristics – for instance, with no husband or children – are entering the workforce.

Why is there a gender pay gap?

In almost all countries, if you compare the wages of men and women you find that women tend to earn less than men. These inequalities have been narrowing across the world. In particular, most high-income countries have seen sizeable reductions in the gender pay gap over the last couple of decades.

How did these reductions come about and why do substantial gaps remain?

Before we get into the details, here is a preview of the main points.

- An important part of the reduction in the gender pay gap in rich countries over the last decades is due to a historical narrowing, and often even reversal of the education gap between men and women.

- Today, education is relatively unimportant in explaining the remaining gender pay gap in rich countries. In contrast, the characteristics of the jobs that women tend to do, remain important contributing factors.

- The gender pay gap is not a direct metric of discrimination. However, evidence from different contexts suggests discrimination is indeed important to understand the gender pay gap. Similarly, social norms affecting the gender distribution of labor are important determinants of wage inequality.

- On the other hand, the available evidence suggests differences in psychological attributes and non-cognitive skills are at best modest factors contributing to the gender pay gap.

Differences in human capital

The adjusted pay gap.

Differences in earnings between men and women capture differences across many possible dimensions, including education, experience, and occupation.

For example, if we consider that more educated people tend to have higher earnings, it is natural to expect that the narrowing of the pay gap across the world can be partly explained by the fact that women have been catching up with men in terms of educational attainment, in particular years of schooling.

Indeed, since differences in education partly contribute to explaining differences in wages, it is common to distinguish between 'unadjusted' and 'adjusted' pay differences.

When the gender pay gap is calculated by comparing all male and female workers, irrespective of differences in worker characteristics, the result is the raw or unadjusted pay gap. In contrast to this, when the gap is calculated after accounting for underlying differences in education, experience, and other factors that matter for the pay gap, then the result is the adjusted pay gap.

The idea of the adjusted pay gap is to make comparisons within groups of workers with roughly similar jobs, tenure, and education. This allows us to tease out the extent to which different factors contribute to observed inequalities.

The chart here, from Blau and Kahn (2017) shows the evolution of the adjusted and unadjusted gender pay gap in the US. 4

More precisely, the chart shows the evolution of female-to-male wage ratios in three different scenarios: (i) Unadjusted; (ii) Adjusted, controlling for gender differences in human capital, i.e. education and experience; and (iii) Adjusted, controlling for a full range of covariates, including education, experience, job industry, and occupation, among others. The difference between 100% and the full specification (the green bars) is the “unexplained” residual. 5

Several points stand out here.

- First, the unadjusted gender pay gap in the US shrunk over this period. This is evident from the fact that the blue bars are closer to 100% in 2010 than in 1980.

- Second, if we focus on groups of workers with roughly similar jobs, tenure, and education, we also see a narrowing. The adjusted gender pay gap has shrunk.

- Third, we can see that education and experience used to help explain a very large part of the pay gap in 1980, but this changed substantially in the decades that followed. This third point follows from the fact that the difference between the blue and red bars was much larger in 1980 than in 2010.

- And fourth, the green bars grew substantially in the 1980s, but stayed fairly constant thereafter. In other words: Most of the convergence in earnings occurred during the 1980s, a decade in which the "unexplained" gap shrunk substantially.

Education and experience have become much less important in explaining gender differences in wages in the US

The next chart shows a breakdown of the adjusted gender pay gaps in the US, factor by factor, in 1980 and 2010.

When comparing the contributing factors in 1980 and 2010, we see that education and work experience have become much less important in explaining gender differences in wages over time, while occupation and industry have become more important. 6

In this chart we can also see that the 'unexplained' residual has gone down. This means the observable characteristics of workers and their jobs explain wage differences better today than a couple of decades ago. At first sight, this seems like good news – it suggests that today there is less discrimination, in the sense that differences in earnings are today much more readily explained by differences in 'productivity' factors. But is this really the case?

The unexplained residual may include aspects of unmeasured productivity (i.e. unobservable worker characteristics that could not be accounted for in the study), while the "explained" factors may themselves be vehicles of discrimination.

For example, suppose that women are indeed discriminated against, and they find it hard to get hired for certain jobs simply because of their sex. This would mean that in the adjusted specification, we would see that occupation and industry are important contributing factors – but that is precisely because discrimination is embedded in occupational differences!

Hence, while the unexplained residual gives us a first-order approximation of what is going on, we need much more detailed data and analysis in order to say something definitive about the role of discrimination in observed pay differences.

Gender pay differences around the world are better explained by occupation than by education

The set of three maps here, taken from the World Development Report (2012) , shows that today gender pay differences are much better explained by occupation than by education. This is consistent with the point already made above using data for the US: as education expanded radically over the last few decades, human capital has become much less important in explaining gender differences in wages.

Justin Sandefur at the Center for Global Development shows that education also fails to explain wage gaps if we include workers with zero income (i.e. if we decompose the wage gap after including people who are not employed).

Looking beyond worker characteristics

Job flexibility.

All over the world women tend to do more unpaid care work at home than men – and women tend to be overrepresented in low-paying jobs where they have the flexibility required to attend to these additional responsibilities.

The most important evidence regarding this link between the gender pay gap and job flexibility is presented and discussed by Claudia Goldin in the article ' A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter ', where she digs deep into the data from the US. 8 There are some key lessons that apply both to rich and non-rich countries.

Goldin shows that when one looks at the data on occupational choice in some detail, it becomes clear that women disproportionately seek jobs, including full-time jobs, that tend to be compatible with childrearing and other family responsibilities. In other words, women, more than men, are expected to have temporal flexibility in their jobs. Things like shifting hours of work and rearranging shifts to accommodate emergencies at home. And these are jobs with lower earnings per hour, even when the total number of hours worked is the same.

The importance of job flexibility in this context is very clearly illustrated by the fact that, over the last couple of decades, women in the US increased their participation and remuneration in only some fields. In a recent paper, Goldin and Katz (2016) show that pharmacy became a highly remunerated female-majority profession with a small gender earnings gap in the US, at the same time as pharmacies went through substantial technological changes that made flexible jobs in the field more productive (e.g. computer systems that increased the substitutability among pharmacists). 9

The chart here shows how quickly female wages increased in pharmacy, relative to other professions, over the last few decades in the US.

The motherhood penalty

Closely related to job flexibility and occupational choice is the issue of work interruptions due to motherhood. On this front, there is again a great deal of evidence in support of the so-called 'motherhood penalty'.

Lundborg, Plug, and Rasmussen (2017) provide evidence from Denmark – more specifically, Danish women who sought medical help in achieving pregnancy. 10

By tracking women’s fertility and employment status through detailed periodic surveys, these researchers were able to establish that women who had a successful in vitro fertilization treatment, ended up having lower earnings down the line than similar women who, by chance, were unsuccessfully treated.

Lundborg, Plug, and Rasmussen summarise their findings as follows: "Our main finding is that women who are successfully treated by [in vitro fertilization] earn persistently less because of having children. We explain the decline in annual earnings by women working less when children are young and getting paid less when children are older. We explain the decline in hourly earnings, which is often referred to as the motherhood penalty, by women moving to lower-paid jobs that are closer to home."

The fact that the motherhood penalty is indeed about ‘motherhood’ and not ‘parenthood’, is supported by further evidence.

A recent study , also from Denmark, tracked men and women over the period 1980-2013 and found that after the first child, women’s earnings sharply dropped and never fully recovered. But this was not the case for men with children, nor the case for women without children.

These patterns are shown in the chart here. The first panel shows the trend in earnings for Danish women with and without children. The second panel shows the same comparison for Danish men.

Note that these two examples are from Denmark – a country that ranks high on gender equality measures and where there are legal guarantees requiring that a woman can return to the same job after taking time to give birth.

This shows that, although family-friendly policies contribute to improving female labor force participation and reducing the gender pay gap , they are only part of the solution. Even when there is generous paid leave and subsidized childcare, as long as mothers disproportionately take additional work at home after having children, inequities in pay are likely to remain.

Ability, personality, and social norms

The discussion so far has emphasized the importance of job characteristics and occupational choice in explaining the gender pay gap. This leads to obvious questions: What determines the systematic gender differences in occupational choice? What makes women seek job flexibility and take a disproportionate amount of unpaid care work?

One argument usually put forward is that, to the extent that biological differences in preferences and abilities underpin gender roles, they are the main factors explaining the gender pay gap. In their review of the evidence, Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn (2017) show that there is limited empirical support for this argument. 11

To be clear, yes, there is evidence supporting the fact that men and women differ in some key attributes that may affect labor market outcomes. For example, standardized tests show that there are statistical gender gaps in maths scores in some countries ; and experiments show that women avoid more salary negotiations , and they often show particular predisposition to accept and receive requests for tasks with low promotion potential . However, these observed differences are far from being biologically fixed – 'gendering' begins early in life and the evidence shows that preferences and skills are highly malleable. You can influence tastes, and you can certainly teach people to tolerate risk, to do maths, or to negotiate salaries.

What's more, independently of where they come from, Blau and Kahn show that these empirically observed differences can typically only account for a modest portion of the gender pay gap.

In contrast, the evidence does suggest that social norms and culture, which in turn affect preferences, behavior, and incentives to foster specific skills, are key factors in understanding gender differences in labor force participation and wages. You can read more about this farther below.

Discrimination and bias

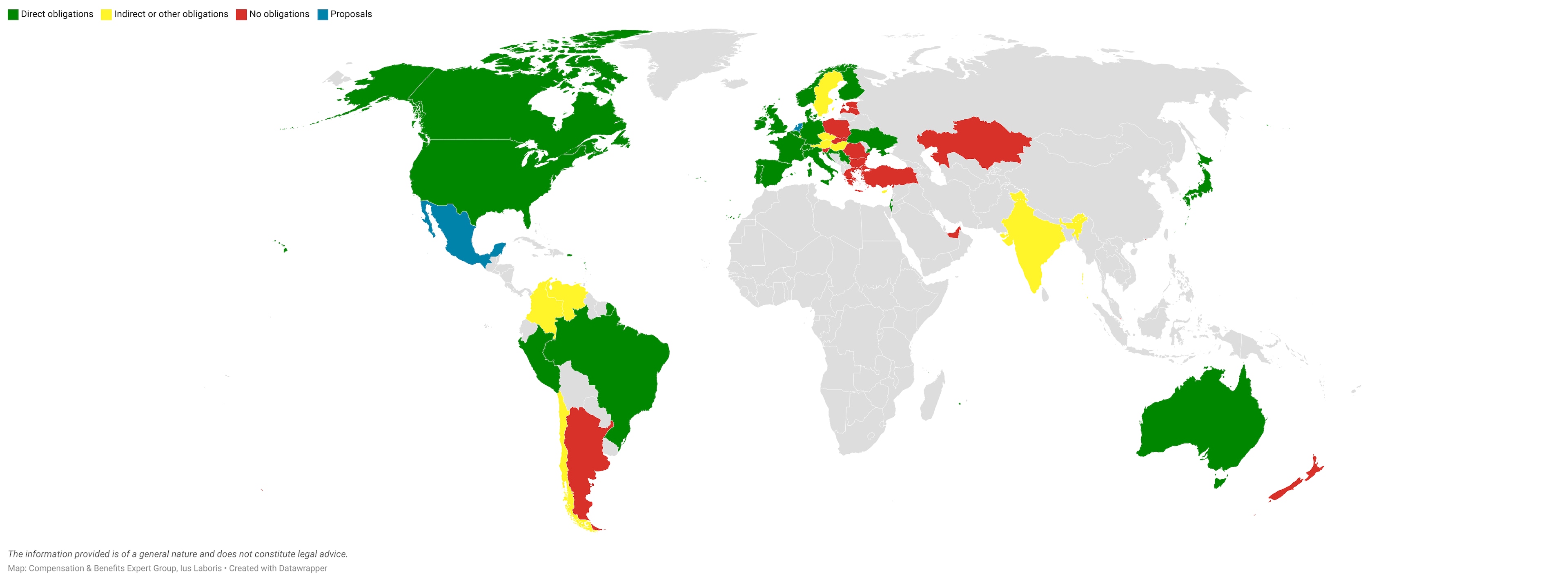

Independently of the exact origin of the unequal distribution of gender roles, it is clear that our recent and even current practices show that these roles persist with the help of institutional enforcement. Goldin (1988), for instance, examines past prohibitions against the training and employment of married women in the US. She touches on some well-known restrictions, such as those against the training and employment of women as doctors and lawyers, before focusing on the lesser known but even more impactful 'marriage bars' that arose in the late 1800s and early 1900s. These work prohibitions are important because they applied to teaching and clerical jobs – occupations that would become the most commonly held among married women after 1950. Around the time the US entered World War II, it is estimated that 87% of all school boards would not hire a married woman and 70% would not retain an unmarried woman who married. 12

The map here highlights that to this day, explicit barriers limit the extent to which women are allowed to do the same jobs as men in some countries. 13

However, even after explicit barriers are lifted and legal protections put in place, discrimination and bias can persist in less overt ways. Goldin and Rouse (2000), for example, look at the adoption of "blind" auditions by orchestras and show that by using a screen to conceal the identity of a candidate, impartial hiring practices increased the number of women in orchestras by 25% between 1970 and 1996. 14

Many other studies have found similar evidence of bias in different labor market contexts. Biases also operate in other spheres of life with strong knock-on effects on labor market outcomes. For example, at the end of World War II only 18% of people in the US thought that a wife should work if her husband was able to support her . This obviously circles back to our earlier point about social norms. 15

Strategies for reducing the gender pay gap

In many countries wage inequality between men and women can be reduced by improving the education of women. However, in many countries, gender gaps in education have been closed and we still have large gender inequalities in the workforce. What else can be done?

An obvious alternative is fighting discrimination. But the evidence presented above shows that this is not enough. Public policy and management changes on the firm level matter too: Family-friendly labor-market policies may help. For example, maternity leave coverage can contribute by raising women’s retention over the period of childbirth, which in turn raises women’s wages through the maintenance of work experience and job tenure. 16

Similarly, early education and childcare can increase the labor force participation of women — and reduce gender pay gaps — by alleviating the unpaid care work undertaken by mothers. 17

Additionally, the experience of women's historical advance in specific professions (e.g. pharmacists in the US), suggests that the gender pay gap could also be considerably reduced if firms did not have the incentive to disproportionately reward workers who work long hours, and fixed, non-flexible schedules. 18

Changing these incentives is of course difficult because it requires reorganizing the workplace. But it is likely to have a large impact on gender inequality, particularly in countries where other measures are already in place. 19

Implementing these strategies can have a positive self-reinforcing effect. For example, family-friendly labor-market policies that lead to higher labor-force attachment and salaries for women will raise the returns on women's investment in education – so women in future generations will be more likely to invest in education, which will also help narrow gender gaps in labor market outcomes down the line. 20

Nevertheless, powerful as these strategies may be, they are only part of the solution. Social norms and culture remain at the heart of family choices and the gender distribution of labor. Achieving equality in opportunities requires ensuring that we change the norms and stereotypes that limit the set of choices available both to men and women. It is difficult, but as the next section shows, social norms can be changed, too.

How well do biological differences explain the gender pay gap?

Across the world, women tend to take on more family responsibilities than men. As a result, women tend to be overrepresented in low-paying jobs where they are more likely to have the flexibility required to attend to these additional responsibilities.

These two facts – documented above – are often used to claim that, since men and women tend to be endowed with different tastes and talents, it follows that most of the observed gender differences in wages stem from biological sex differences. But what’s the broader evidence for these claims?

In a nutshell, here's what the research and data shows:

- There is evidence supporting the fact that statistically speaking, men and women tend to differ in some key aspects, including psychological attributes that may affect labor-market outcomes.

- There is no consensus on the exact weight that nurture and nature have in determining these differences, but whatever the exact weight, the evidence does show that these attributes are strongly malleable.

- Regardless of the origin, these differences can only explain a modest part of the gender pay gap.

Some context regarding the gender distribution of labor

Before we get into the discussion of whether biological attributes explain wage differences via gender roles, let's get some perspective on the gender distribution of work.

The following chart shows, by country, the female-to-male ratio of time devoted to unpaid care work, including tasks like taking care of children at home, housework, or doing community work. As can be seen, all over the world there is a radical unbalance in the gender distribution of labor – everywhere women take a disproportionate amount of unpaid work.

This is of course closely related to the fact that in most countries there are gender gaps in labor force participation and wages .

“Boys are better at maths”

Differences in biological attributes that determine our ability to develop 'hard skills', such as maths, are often argued to be at the heart of the gender pay gap. 21 Do large gender differences in maths skills really exist? If so, is this because of differences in the attributes we are born with?

Let's look at the data.

Are boys better in the mathematics section of the PISA standardized test ? One could argue that looking at top scores is more relevant here since top scores are more likely to determine gaps in future professional trajectories – for example, gaps in access to 'STEM degrees' at the university level.

The chart shows the share of male and female test-takers scoring at the highest level on the PISA test (that's level 6). As we can see, most countries lie above the diagonal line marking gender parity; so yes, achieving high scores in maths tends to be more common among boys than girls. However, there is huge cross-country variation – the differences between countries are much larger than the differences between the sexes. And in many countries, the gap is effectively inexistent. 22

Similarly, researchers have found that within countries there is also large geographic variation in gender gaps in test scores. So clearly these gaps in mathematical ability do not seem to be fully determined by biological endowments. 23

Indeed, research looking at the PISA cross-country results suggests that improved social conditions for women are related to improved math performance by girls. 24

Not only do statistical gaps in test scores vary substantially across societies – they also vary substantially across time. This suggests that social factors play a large role in explaining differences between the sexes.

In the US, for example, the gender gap in mathematics has narrowed in recent decades. 25 And this narrowing took place as high school curricula of boys and girls became more similar. The following chart shows this: In the US boys in 1957 took far more math and science courses than did girls; but by 1992 there was virtual parity in almost all science and math courses.

More importantly for the question at hand, gender gaps in 'hard skills' are not large enough to explain the gender gaps in earnings. In their review of the evidence, Blau and Kahn (2017) concludes that gaps in test scores in the US are too small to explain much of the gender pay at any point in time. 26

So, taken together, the evidence suggests that statistical gaps in maths test scores are both relatively small and heavily influenced by social and environmental factors.

“It’s about personality”

Biological differences in tastes (e.g. preferences for 'people' over 'things'), psychological attributes (e.g. 'risk aversion'), and soft skills (e.g. the ability to get along with others) are also often argued to be at the heart of the gender pay gap.

There are hundreds of studies trying to establish whether there are gender differences in preferences, personality traits, and 'soft skills'. The quality and general relevance (i.e. the internal and external validity) of these studies is the subject of much discussion, as illustrated in the recent debate that ensued from the Google Memo affair .

A recent article from the 'Heterodox Academy ', which was produced specifically in the context of the Google Memo, provides a fantastic overview of the evidence on this topic and the key points of contention among scholars.

For the purpose of this blog post, let's focus on the review of the evidence presented in Blau and Kahn (2017) – their review is particularly helpful because they focus on gender differences in the context of labor markets.

Blau and Kahn point out that, yes, researchers have found statistical differences between men and women that are important in the context of labor-market outcomes. For example, studies have found statistical gender differences in 'people skills' (i.e. ability to listen, communicate, and relate to others). Similarly, experimental studies have found that women more often avoid salary negotiations , and they often show a particular predisposition to accept and receive requests for tasks with low promotability. But are the origins of these differences mainly biological or are they social? And are they strong enough to explain pay gaps?

The available evidence here suggests these factors can only explain a relatively small fraction of the observed differences in wages. 27 And they are anyway far from being purely biological – preferences and skills are highly malleable and 'gendering' begins early in life. 28

Here is a concrete example: Leibbrandt and List (2015) did an experiment in which they assessed how men and women reacted to job advertisements. 29 They found that although men were more likely to negotiate than women when there was no explicit statement that wages were negotiable, the gender difference disappeared and even reversed when it was explicitly stated that wages were negotiable. This suggests that it is not as much about 'talent', as it is about norms and rules.

“A man should earn more than his wife”

The experiment in which researchers found that gender differences in negotiation attitudes disappeared when it was explicitly stated that wages were negotiable, emphasizes the important role that social norms and culture play in labor-market outcomes.

These concepts may seem abstract: What do social norms and culture actually look like in the context of the gender pay gap?

The reproduction of stereotypes through everyday positive enforcement can be seen in a range of aspects: A study analyzing 124 prime-time television programs in the US found that female characters continue to inhabit interpersonal roles with romance, family, and friends, while male characters enact work-related roles. 30 In the realm of children’s books, a study of 5,618 books found that compared to females, males are represented nearly twice as often in titles and 1.6 times as often as central characters. 31 Qualitative research shows that even in the home, parents are often enforcers of gender norms – especially when it comes to fathers endorsing masculinity in male children. 32

Of particular relevance in the context of labor markets, social norms also often take the form of specific behavioral prescriptions such as "a man should earn more than his wife".

The following chart depicts the distribution of the share of the household income earned by the wife, across married couples in the US.

Consistent with the idea that "a man should earn more than his wife", the data shows a sharp drop at 0.5, the point where the wife starts to earn more than the husband.

Distribution of income share earned by the wife across married couples in the US – Bertrand, Kamenica, and Pan (2015) 33

This is the result of two factors. First, it is about the matching of men and women before they marry – 'matches' in which the woman has higher earning potential are less common. Second, it is a result of choices after marriage – the researchers show that married women with higher earning potential than their husbands often stay out of the labor force, or take 'below-potential' jobs. 34

The authors of the study from which this chart is taken explored the data in more detail and found that in couples where the wife earns more than the husband, the wife spends more time on household chores, so the gender gap in unpaid care work is even larger; and these couples are also less satisfied with their marriage and are more likely to divorce than couples where the wife earns less than the husband.

The empirical exploration in this study highlights the remarkable power that gender norms and identity have on labor-market outcomes.

Why do gender norms and identity matter?

Does it actually matter if social norms and culture are important determinants of gender roles and labor-market outcomes? Are social norms in our contemporary societies really less fixed than biological traits?

The available research suggests that the answers to these questions are yes and yes. There is evidence that social norms can be actively and rapidly changed.

Here is a concrete example: Jensen and Oster (2009) find that the introduction of cable television in India led to a significant decrease in the reported acceptability of domestic violence towards women and son preference, as well as increases in women’s autonomy and decreases in fertility. 35

Of course, TV is a small aspect of all the big things that matter for social norms. But this study is important for the discussion because it is hard to study how social norms can be changed. TV introduction is a rare opportunity to see how a group that is exposed to a driver of social change actually changes.

As Jensen and Oster point out, most popular cable TV shows in India feature urban settings where lifestyles differ radically from those in rural areas. For example, many female characters on popular soap operas have more education, marry later, and have smaller families than most women in rural areas. And, similarly, many female characters in these tv shows are featured working outside the home as professionals, running businesses, or are shown in other positions of authority.

The bar chart below shows how cable access changed attitudes toward the self-reported preference for their child to be a son. As the authors note, "reported desire for the next child to be a son is relatively unchanged in areas with no change in cable status, but it decreases sharply between 2001 and 2002 for villages that get cable in 2002, and between 2002 and 2003 (but notably not between 2001 and 2002) for those that get cable in 2003. For both measures of attitudes, the changes are large and striking, and correspond closely to the timing of introduction of cable."

To conclude: The evidence suggests that biological differences are not a key driver of gender inequality in labor-market outcomes; while social norms and culture – which in turn affect preferences, behavior, and incentives to foster specific skills – are very important.

This matters for policy because social norms are not fixed – they can be influenced in a number of ways, including through intergenerational learning processes, exposure to alternative norms, and activism such as that which propelled the women's movement. 36

How are women represented across jobs?

Representation of women at the top of the income distribution.

Despite having fallen in recent decades, there remains a substantial pay gap between the average wages of men and women .

But what does gender inequality look like if we focus on the very top of the income distribution? Do we find any evidence of the so-called 'glass ceiling' preventing women from reaching the top? How did this change over time?

Answers to these questions are found in the work of Atkinson, Casarico and Voitchovsky (2018). Using tax records, they investigated the incomes of women and men separately across nine high-income countries. As such, they were restricted to those countries in which taxes are collected on an individual basis, rather than as couples. 37

In addition to wages they also take into account income from investments and self-employment.

Whilst investment income tends to make up a larger share of the total income of rich individuals in general, the authors found this to be particularly marked in the case of women in top-income groups.

The two charts present the key figures from the study.

One chart shows the proportion of women out of all individuals falling into the top 10%, 1%, and 0.1% of the income distribution. The open circle represents the share of women in the top income brackets back in 2000; the closed circle shows the latest data, which is from 2013.

The other chart shows the data over time for individual countries. You can explore data for other countries using the 'Change country' button on the chart.

The two charts allow us to answer the initial questions:

- Women are greatly under-represented in top income groups – they make up much less than 50% across each of the nine countries. Within the top 1% women account for around 20% and there is surprisingly little variation across countries.

- The proportion of women is lower the higher you look up the income distribution. In the top 10% up to every third income-earner is a woman; in the top 0.1% only every fifth or tenth person is a woman.

- The trend is the same in all countries of this study: Women are now better represented in all top-income groups than they were in 2000.

- But improvements have generally been more limited at the very top. With the exception of Australia, we see a much smaller increase in the share of women amongst the top 0.1% than amongst the top 10%.

Overall, despite recent inroads, we continue to see remarkably few women making it to the top of the income distribution today.

Representation of women in management positions

The chart here plots the proportion of women in senior and middle management positions around the world. It shows that women all over the world are underrepresented in high-profile jobs, which tend to be better paid.

The next chart provides an alternative perspective on the same issue. Here we show the share of firms that have a woman as manager. We highlight world regions by default, but you can remove them and add specific countries.

As we can see, all over the world firms tend to be managed by men. And, globally, only about 18% of firms have a female manager.

Firms with female managers tend to be different to firms with male managers. For example, firms with female managers tend to also be firms with more female workers .

Representation of women in low-paying jobs

Above we show that women all over the world are underrepresented in high-profile jobs, which tend to be better paid. As it turns out, in many countries women are at the same time overrepresented in low-paying jobs.

This is shown in the chart here, where 'low-pay' refers to workers earning less than two-thirds of the median (i.e. the middle) of the earnings distribution.

A share above 50% implies that women are 'overrepresented', in the sense that among those with low wages, there are more women than men.

The fact that women in rich countries are overrepresented in the bottom of the income distribution goes together with the fact that working women in these countries are overrepresented in low-paying occupations. The chart shows this for the US.

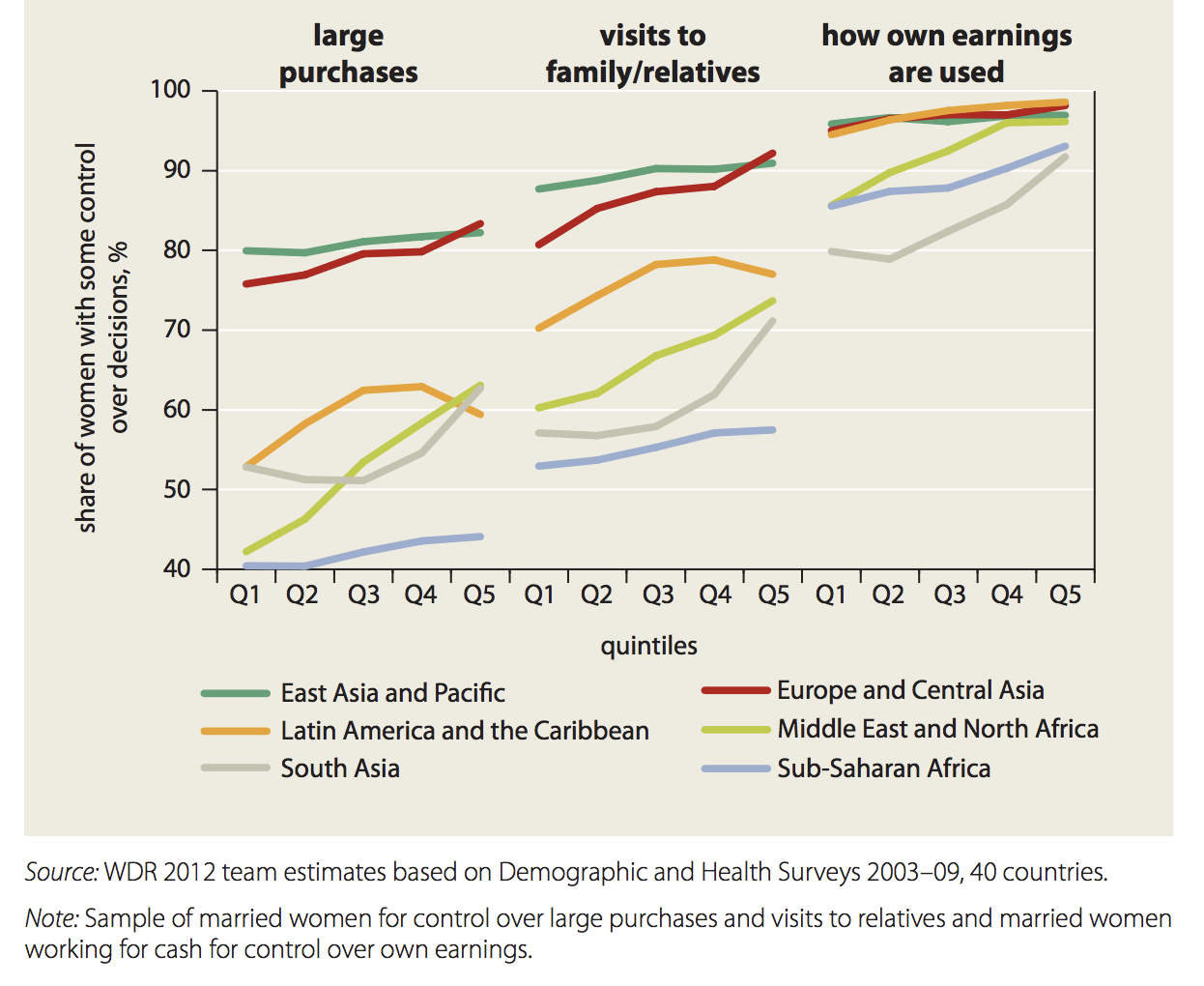

How much control do women have over household resources?

Women often have no control over their personal earned income.

The next chart plots cross-country estimates of the share of women who are not involved in decisions about their own income. The line shows national averages, while the dots show averages for rich and poor households (i.e. averages for women in households within the top and bottom quintiles of the corresponding national income distribution).

As we can see, in many countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, a large fraction of women are not involved in household decisions about spending their personal earned income. And this pattern is stronger among low-income households within low-income countries.

Percentage of women not involved in decisions about their own income – World Development Report (2012) 39

In many countries, women have limited influence over important household decisions

Above we focus on whether women get to choose how their own personal income is spent. Now we look at women's influence over total household income.

In this chart, we plot the share of currently married women who report having a say in major household purchase decisions, against national GDP per capita.

We see that in many countries, notably in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, an important number of women have limited influence over major spending decisions.

The chart above shows that women’s control over household spending tends to be greater in richer countries. In the next chart, we show that this correlation also holds within countries: Women’s control is greater in wealthier households. Household wealth is shown by the quintile in the wealth distribution on the x-axis – the poorest households are in the lowest quintiles (Q1) on the left.

There are many factors at play here, and it's important to bear in mind that this correlation partly captures the fact that richer households enjoy greater discretionary income beyond levels required to cover basic expenditure, while at the same time, in richer households women often have greater agency via access to broader networks as well as higher personal assets and incomes.

Land ownership is more often in the hands of men