- IMC Library

- Library Guides

Legal Method, Research and Writing

- Academic Writing in Law

- Legal Research Basics

- Law Database Guides

- Referencing in Law

- Other Research Resources for Law

Email Ettiquette

THE BASIC RULES

- Don't use an unprofessional email address

- Start with a new e-mail

- Include an appropriate subject heading

- Write a salutation

- Write well!

- Provide context and background information

- Write a clear and concise message

- Sign your name

- Proofread the e-mail

- Allow adequate time for a reply

- Writing Professional Emails More detailed advice about how to write emails to academic staff

Academic Writing and Research in Law

- UTS Guide to Writing in Law A highly recommended helpful and comprehensive guide to writing law papers.

- Monash University Guide to Writing in Law Law writing guide with helpful Q&A's and tips for planning out case argumentation.

- University of Queensland Legal Research Essentials Introduction to Legal Research by The University of Queensland, Australia

Other Help:

- Quoting, Paraphrasing, Summarising The basic differences in how to writes quotes, how to write paraphrases, and how to write summaries of the sources you find.

Basic Rules

Academic and professional legal writing requires you to develop an argument and demonstrate relationships between the ideas you are expressing.

Therefore, the ability to express yourself clearly and accurately is important. Here you will find information to help you improve your writing for any purpose in your law degree.

Academic writing in law is:

Academic writing in law does not:

Steps to Writing a Law Essay

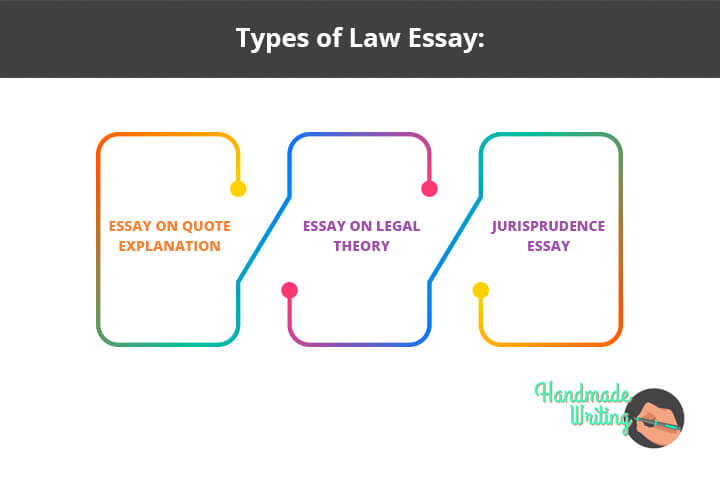

Throughout your law degree, you will be expected to write a range of different texts, including research essays, responses to problem questions, and case notes.

Not matter the type of text you are asked to produce for an assignment, make sure you follow these steps:

- Plan : read the questions carefully and think about how you will answer it

- Research : read, read and read! Make use of everything available to you - don't forget the library!

- Make thorough notes : include all important (and relevant) details and quotes and take note of the source. Make sure you organise your notes so as to make the writing task easier

- Write the first draft : before you start writing your first draft, refer back to your initial plan and make any necessary changes now you have done your research and gathered your notes.

- Review and edit : remember to proofread your work!

The IRAC Method

IRAC is an acronym that stands for: Issue, Rule, Application, and Conclusion. It functions as a methodology for legal analysis and is used as a framework for organising your answer to an essay question in law school.

[ Open All | Close All ]

In legal writing, issues are the core of the essay.

This part of the essay should:

- Identify and state the issue

- Name those involved (plaintiff and defendant) and briefly describe their individual issues

- Work out what body of law may govern the resolution of the issue (e.g. Contract Law)

The rule describes which law applies to the issue. The rule should be stated as a general principle, and not a conclusion to the particular case being briefed.

- Outline the legal principles that will be used to address to the issue

- Source legal principles from cases and legislation

The application is the most important and longest part of your answer. It involves applying the Rule to the facts of the issue and demonstrating how those facts do or do not meet the requirements laid down by the rules. Discuss both sides of the case when possible.

- Explain why the plaintiff's claims are or are not justified

- Identify how the law will be used by the plaintiff and defendant to argue their case

- Use relevant cases and legal principles to support your writing

- Do not try to strengthen your argument by leaving out elements or facts that will hurt it

As with all essays, the conclusion is a statement that identifies your answer to the issue.

- Identify what the result of your argument ir, or what it should be

- State who is liable for what and to what extent

- Consider how the plaintiff and defendant could have acted to avoid this legal issue

Useful Links:

- UWA IRAC Guide This guide from the University of Western Australia offers examples of how the IRAC method can be applied to different cases.

- Law School Survival: The IRAC Method A useful site that presents a detailed outline of the IRAC method as well as skeleton outlines.

Law Writing Media

Additional Resource

Featured Resource

Further Support

Related Guides

Proofreading Tool

- Last Updated: Jan 17, 2024 3:38 PM

- URL: https://top-au.libguides.com/legal-method-research-and-writing

Copyright © 2019 Australian National Institute of Management and Commerce (IMC) Registered Higher Education Provider TEQSA PRV12059 | CRICOS 02491D Top Education Group Ltd ACN 098 139 176 trading as Australian National Institute of Management and Commerce (IMC) All content is subject to change.

Username or email *

Password *

Forgotten password?

[email protected]

+44 (0)20 8834 4579

How to Write a First-Class Law Essay

Studying law at university entails lots of essay writing. This article takes you through the key steps to writing a top law essay.

Writing a law essay can be a challenging task. As a law student, you’ll be expected to analyse complex legal issues and apply legal principles to real-world scenarios. At the same time, you’ll need to be able to communicate your ideas clearly and persuasively. In this article, we’ll cover some top tips to guide you through the process of planning, researching, structuring and writing a first-class law essay with confidence.

1. Start In Advance

Give yourself plenty of time to plan, research and write your law essay. Always aim to start your law essay as soon as you have the question. Leaving it until the last minute does not only create unnecessary stress, but it also leaves you insufficient time to write, reference and perfect your work.

2. Understand The Question

Do not begin until you fully comprehend the question. Take the time to read the question carefully and make sure that you understand what it’s asking you to do. Highlight key terms and annotate the question with definitions of key concepts and any questions that you have have. Think about how the question links back to what you’ve learned during your lectures or through your readings.

3. Conduct Thorough Research

Conducting thorough research around your topic is one of the most fundamental parts of the essay writing process. You should aim to use a range of relevant sources, such as cases, academic articles, books and any other legal materials. Ensure that the information you collect is taken from relevant, reliable and up to date sources. Use primary over secondary material as much as possible.

Avoid using outdated laws and obscure blog posts as sources of information. Always aim to choose authoritative sources from experts within the field, such as academics, politicians, lawyers and judges. Using high-quality and authoritative sources and demonstrating profound and critical insight into your topic are what will earn you top marks.

4. Write A Detailed Plan

Once you’ve done your research, it’s time to plan your essay. When writing your plan, you’ll need to create an outline that clearly identifies the main points that you wish to make throughout your article. Try to write down what you wish to achieve in each paragraph, what concepts you want to discuss and arguments you want to make.

Your outline should be organised in a clear, coherent and logical manner to ensure that the person grading your essay can follow your line of thought and arguments easily. You may also wish to include headings and subheadings to structure your essay effectively This makes it easier when it comes to writing the essay as starting without a plan can get messy. The essay must answer the question and nothing but the question so ensure all of your points relate to it.

Start Writing Like A Lawyer

Read our legal writing tips now

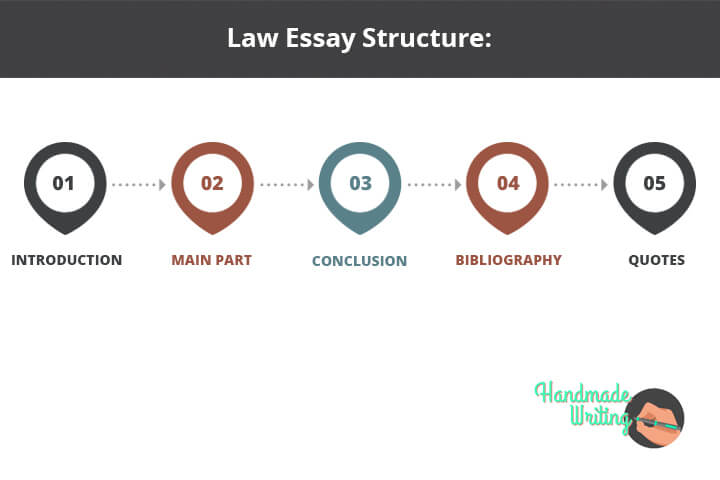

5. Write A Compelling Introduction

A great introduction should, firstly, outline the research topic. The introduction is one of the most crucial parts of the law essay as it sets the tone for the rest of the paper. It should capture the readers attention and provide the background context on the topic. Most importantly, it should state the thesis of your essay.

When writing your introduction, avoid simply repeating the given question. Secondly, create a road map for the reader, letting them know how the essay will approach the question. Your introduction must be concise. The main body of the essay is where you will go into detail.

6. Include A Strong Thesis Statement

Your thesis should clearly set out the argument you are going to be making throughout your essay and should normally go in the introduction. Your thesis should adopt a clear stance rather than being overly general or wishy-washy. To obtain the best grades, you’ll need to show a unique perspective based upon a critical analysis of the topic rather than adopting the most obvious point of view.

Once you’ve conducted your research and had a chance to reflect on your topic, ask yourself whether you can prove your argument within the given word count or whether you would need to adopt a more modest position for your paper. Always have a clear idea of what your thesis statement is before you begin writing the content of your essay.

7. Present the Counter-argument

To demonstrate your deeper understanding of the topic, it’s important to show your ability to consider the counter-arguments and address them in a careful and reasoned manner. When presenting your counterarguments, aim to depict them in the best possible light, aiming to be fair and reasonable before moving on to your rebuttal. To ensure that your essay is convincing, you will need to have a strong rebuttal that explains why your argument is stronger and more persuasive. This will demonstrate your capacity for critical analysis, showing the reader that you have carefully considered differing perspectives before coming to a well-supported conclusion.

8. End With A Strong Conclusion

Your conclusion is your opportunity to summarise the key points made throughout your essay and to restate the thesis statement in a clear and concise manner. Avoid simply repeating what has already been mentioned in the body of the essay. For top grades, you should use the conclusion as an opportunity to provide critical reflection and analysis on the topic. You may also wish to share any further insights or recommendations into alternative avenues to consider or implications for further research that could add value to the topic.

9. Review The Content Of Your Essay

Make sure you factor in time to edit the content of your essay. Once you’ve finished your first draft, come back to it the next day. Re-read your essay with a critical perspective. Do your arguments make sense? Do your paragraphs flow in a logical manner? You may also consider asking someone to read your paper and give you critical feedback. They may be able to add another perspective you haven’t considered or suggest another research paper that could add value to your essay.

10. Proofread For Grammatical Mistakes

Once you’re happy with the content of your essay, the last step is to thoroughly proofread your essay for any grammatical errors. Ensure that you take time to ensure that there are no grammar, spelling or punctuation errors as these can be one of the easiest ways to lose marks. You can ask anyone to proofread your paper, as they would not necessarily need to have a legal background – just strong grammar and spelling skills!

11. Check Submission Guidelines

Before submitting, ensure that your paper conforms with the style, referencing and presentation guidelines set out by your university. This includes the correct font, font size and line spacing as well as elements such as page numbers, table of content etc. Referencing is also incredibly important as you’ll need to make sure that you are following the correct referencing system chosen by your university. Check your university’s guidelines about what the word count is and whether you need to include your student identification number in your essay as well. Be thorough and don’t lose marks for minor reasons!

12. Use Legal Terms Accurately

Always make sure that you are using legal terms accurately throughout your essay. Check an authoritative resource if you are unsure of any definitions. While being sophisticated is great, legal jargon if not used correctly or appropriately can weaken your essay. Aim to be concise and to stick to the point. Don’t use ten words when only two will do.

12. Create a Vocabulary Bank

One recurring piece of advice from seasoned law students is to take note of phrases from books and articles, key definitions or concepts and even quotes from your professors. When it comes to writing your law essay, you will have a whole range of ideas and vocabulary that will help you to develop your understanding and thoughts on a given topic. This will make writing your law essay even easier!

13. Finally, Take Care of Yourself

Last but certainly not least, looking after your health can improve your attitude towards writing your law essay your coursework in general. Sleep, eat, drink and exercise appropriately. Take regular breaks and try not to stress. Do not forget to enjoy writing the essay!

Words by Karen Fulton

Free Guides

Our free guides cover everything from deciding on law to studying and practising law abroad. Search through our vast directory.

Upcoming Events

Explore our events for aspiring lawyers. Sponsored by top institutions, they offer fantastic insights into the legal profession.

Join Our Newsletter

Join our mailing list for weekly updates and advice on how to get into law.

Law Quizzes

Try our selection of quizzes for aspiring lawyers for a fun way to gain insight into the legal profession!

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

Legal Writing: Start Writing Like a Lawyer!

NEXT ARTICLE

LLM Jobs for Graduates

Loading More Content

The Concepts of Law

Thanks to John Gerring, Brian Leiter, Saul Levmore, Simone Sepe, and Lawrence Solum for superb comments.

- Share The University of Chicago Law Review | The Concepts of Law on Facebook

- Share The University of Chicago Law Review | The Concepts of Law on Twitter

- Share The University of Chicago Law Review | The Concepts of Law on Email

- Share The University of Chicago Law Review | The Concepts of Law on LinkedIn

Concepts are the building blocks of legal doctrine. All legal rules and standards, in fact, are formed by combining concepts in different ways. But despite their centrality, legal concepts are not well understood. There is no agreement as to what makes a legal concept useful or ineffective—worth keeping or in need of revision. Social scientists, however, have developed a set of criteria for successful concepts. Of these, the most important is measurability: the ability, at least in principle, to assess a concept with data. In this Essay, we apply the social scientific criteria to a number of concepts and conceptual relationships in American constitutional law. We show that this field includes both poor and effective concepts and conceptual links. We also explain how the examples of poor concepts could be improved.

I. A Primer on Conceptualization and Measurement

A. Concepts and Conceptualization

Concepts provide the mental architecture by which we understand the world and are ubiquitous in social science as well as law. Conceptualization involves the process of formulating a mental construct at a particular level of abstraction. 10 A large debate in the philosophy of cognitive science grapples with different views of concepts. 11 Some regard concepts as essentially nominal in character, meaning that they are about definitions of phenomena rather than the phenomena themselves. Some see concepts as marking mental representations of phenomena. 12 Others see concepts as ontological claims or “theories about the fundamental constitutive elements of a phenomenon.” 13

“Concept” itself is a tricky concept. For our purposes, concepts can be distinguished from other phenomena of interest to law such as words or rules. Law is composed of words or labels, but these are different from the concepts that are the building blocks of law. To see why, consider that a single label can refer to multiple concepts: a right means one thing when giving directions, but quite another when discussing the legal system. Even within the law, the concept of a right is different when thinking about an individual’s freedom from torture than when talking about Mother Nature’s right to remediation. 14 Conversely, a similar concept can be represented by different words.

Concepts are also distinct from rules . Rules provide decision procedures to categorize behavior as, for example, legal or illegal. A legal rule is composed of multiple concepts put together in a particular kind of relationship: if someone engages in murder , she shall be subject to a penalty of imprisonment . Each of these concepts might have subconcepts: murder , for example, is killing with malice aforethought or intent . The rule provides the criteria for decision, but relies on abstract ideas—concepts—with more or less intuitive appeal. This simple example demonstrates that law is built of concepts and subconcepts, structured together in particular ways.

Some concepts are developed through necessary, or necessary and sufficient, attributes. It is necessary that a mammal be an animal; it is necessary and sufficient that it be an animal that secretes milk to feed its young. Another way of approaching attributes is to list all the desirable ones, and perhaps to treat them additively, so that more of them will get one closer to the ideal of the particular concept. This is sometimes called a maximal strategy of conceptualization and is exemplified at the extreme by Max Weber’s concept of an ideal type, which may never be met in practice. 15 A third approach relies on the “family resemblance” of phenomena, so that even if no single attribute is necessary or sufficient, the presence of enough attributes will suffice to mark the presence of the concept. 16 Bearing live young, possessing fur, and secreting milk are common or typical attributes of mammals, even though the platypus, a mammal, does not have all of these features. Finally, and most relevant to our project here, some believe that concepts are always embedded in a broader theory, so that their essential features may not be observable at all, but instead are defined as part of the background theory. This is known as the “theory theory” of concepts. 17

Many legal tests are formulated as having necessary and sufficient attributes. If one has a duty to behave in a particular way, has breached this duty, and has caused damage to another, then one has, by definition, committed a tort. But some legal concepts are formulated as multipart tests in which factors are added and weighed, with an eye toward seeing if the ideal is met. In deciding if an attorney in a prevailing ERISA claim is to be awarded fees, for example, courts apply a five-factor test:

(1) the degree of culpability or bad faith attributable to the losing party; (2) the depth of the losing party’s pocket, i.e., his or her capacity to pay an award; (3) the extent (if at all) to which such an award would deter other persons acting under similar circumstances; (4) the benefit (if any) that the successful suit confers on plan participants or beneficiaries generally; and (5) the relative merit of the parties’ positions. 18

The implicit concept here is an ideal type of what might be called appropriate fee-shifting. None of the five elements is absolutely necessary, but if all five are plainly met, the ideal type will be achieved. The closer one gets to the ideal type, the more likely one is to get an award. The internal participant within the legal system, in this case a judge, will engage in the process of running through the attributes to see if they are met.

Legal concepts come in different levels of abstraction, often nested within one another. Private law is more encompassing than tort, which in turn encompasses negligent infliction of emotional distress. Unlike in social science, however, there is not much explicit legal work on concept formation, and few of the rich definitional debates that mark social scientific literatures on, say, democracy or even the rule of law. Our argument is that paying attention to legal concepts can improve the structure of the law.

B. What Makes a Good Concept?

There are several different social scientific conceptualizations about what it is that makes a good concept. A common approach is a listing of attributes, such as parsimony, explanatory power, and distinction from other concepts. These lists vary from scholar to scholar, but we rely on a recent contribution from the prominent social scientist Professor John Gerring, who argues that a good social scientific concept can be evaluated on several dimensions. 19 It should have resonance, in that it should “make[ ] sense” to observers; it should have a stipulated domain over which it applies; it should be consistent, in the sense of conveying the same meaning in different contexts; it should be “fecund,” meaning that it has richness and depth; it should be differentiated from other neighboring concepts; it should have causal utility, meaning that it is useful; and it should in principle be measurable, that is, capable of being operationalized within social scientific frameworks. 20 Let us describe each of these in a bit more detail, with an application to law.

Resonance is a quality that is essentially linguistic in character, and can easily be applied to law. For example, we can ask whether a legal test is resonant with the relevant audience. Does the framework of examining tiers of scrutiny “make sense” to observers? Is proportionality an intuitive concept in terms of advancing ideas about justice? Is it faithful to established definitions? 21 We can also compare legal concepts for linguistic resonance: For example, in considering instances when a government diminishes an investment’s value, is “indirect expropriation” or “regulatory taking” a better concept? Resonance is essentially about labels and how well they communicate an idea to an audience.

Many legal concepts are clearly resonant. However, it is an interesting feature of some legal concepts that they are in fact distinct from the ordinary meaning attached to the same terms. Only in law does “intent” include reckless disregard as well as intending the outcome; “statutory rape” adds the adjective precisely because the conduct it condemns is consensual. There is thus some variation across legal concepts in terms of resonance.

Domain simply refers to the realm in which a concept applies, and is fairly clear when applied to law. 22 The domain of legal concepts is, in fact, the legal system, and is not meant to encompass anything outside it. Thus, specialized language within the law is deployed internally. Common-law marriage refers to the idea that the marriage is legal, even if not formally recorded.

Consistency requires that a concept carry the same meaning in different empirical contexts. 23 If the concept of felony murder is different in Louisiana and California, this would violate the requirement of consistency. Observe that the legal definitions in the two states might diverge, maybe even dramatically, but this does not mean that the concept would differ. But it is also the case that, for example, multipart tests may put pressure on conceptual consistency across contexts. To use the fee-shifting example described above, if an award were based primarily on the wealth of the losing party, it would imply a different purpose than if it were based on deterrence considerations. These might be seen as internally inconsistent applications of the test, ultimately based on different concepts.

Fecundity is defined by Gerring as referring to “coherence, depth, fruitfulness, illumination, informative-ness, insight, natural kinds, power, productivity, richness, or thickness.” 24 This collection of descriptors has to do with a concept’s ability to describe reality in a rich way, and in some sense to reveal a structure that might not be apparent without the concept. 25 It is a desirable feature of social science, though not so important in law in our view, because some legal concepts can be limited to very narrow technical applications. For example, in social science, in thinking about different types of political “regimes,” one might distinguish authoritarian regimes from democracies, or might alternately look at particular subtypes within each category: electoral authoritarians, totalitarians, military regimes, and absolute monarchies, 26 or presidential and parliamentary democracies. 27 An analogously fecund legal concept might be “rights,” which has generated many subtypes. But other legal concepts can be narrow and yet still effective within their specific domain: a lien or a stay, for example, reveals no deep structure.

Differentiation refers to the distinction between a concept and a neighboring concept. 28 Sometimes concepts are defined by their neighboring concepts. As Gerring notes, nation-states are defined in contrast with empires, political parties in contrast with interest groups. 29 It is thus the case that new concepts are best when they fit within existing concepts. When a new legal idea is created—sexual harassment, for example—it is helpful to mark how it differs from existing concepts. 30

Causal utility refers to the usefulness of a concept. 31 Obviously, this is domain specific. Professor Gary Goertz focuses on the utility of concepts for social scientific methods. 32 But in law we might ask how easy the concept is for courts to apply, and how effective it is in differentiating lawful from unlawful behavior.

The requirement that a concept be measurable is a frequent desideratum in social scientific accounts of concepts (in which it is sometimes called operationalizability). The idea here is not that there must be available data or indicators that meet the standard tests of social science. Instead, the point of measurability is that in principle there ought to be data that could be deployed to test theories that use the concept. 33 For legal tests, it may be prudent to consider whether measures can be developed in principle. This might help to ensure that the analyst is proposing a workable test that is capable of achieving its aims.

Consider an example of an internal legal doctrine, drawn again from the five-part test for attorney’s fees in the ERISA context. 34 Some of the elements are more amenable to empirical verification than others: the wealth of the losing party and the potential deterrent effect of an award are, in principle, quantifiable. The other elements—culpability, benefits, and relative merit—are less so. To successfully deploy this conceptual test, courts will thus have to aggregate, by an unknown weighting formula, five different elements that are fairly discrete, possibly incommensurable, and difficult to operationalize. To the extent that the elements are measurable, this exercise could be more precise, transparent, and ultimately legitimate. Our view is that measurability, even in principle, can bring precision and discipline to law.

C. Relationships among Concepts

Many of the central questions in social science involve relationships among different concepts. Does democracy increase economic growth? Does race correlate with voting behavior? Do people behave rationally in their investment decisions? Are military alliances stable across time? Each of these questions features at least two different concepts, which might in theory take on different meanings and surely could be measured in many different ways. Each also features a relationship among concepts, whether causal or correlative.

Examining these relationships among concepts also requires operationalizing them. This means we must come up with tractable indicators or measures that can then be deployed into a research design. Indeed, some argue that this is the central criterion of a good social scientific concept. If a concept is not capable of being operationalized, then it is lacking a central characteristic, and even the presence of many other desirable features may not be able to save it. 35

Law, too, is centrally concerned with relationships among concepts. The variety of conceptual relationships in law is very large. The multipart tests mentioned above aggregate a variety of concepts into a single framework, which is fundamentally an additive approach to linking concepts. In contrast, the famous framework of Professor Wesley Hohfeld distinguished between conceptual correlates and conceptual opposites. 36 Correlative relationships are exemplified by the binary of right and duty, which co-occur so that if someone has a right, someone else has a duty. Opposites, on the other hand, are conceptually distinct. For example, someone with no duty has a privilege to do something or not; privilege and duty are opposites in Hohfeld’s framework. 37 In other cases, concepts are nested within one another in fields: tort includes intentional infliction of emotional distress. Still other concepts can cut across fields: the concept of intent is used in multiple fields of law, sometimes in different ways. Many further types of semantic relationships are conceivable as well.

Rather than try to exhaustively categorize all possible relationships, we are most concerned here with a particular kind of connection among legal concepts: that of a causal character. Causal relationships are very common in legal concepts. At the most basic level, law often seeks to advance particular interests. Some of these interests, such as efficiency, justice, or fairness, are external to the law itself. Others may themselves be defined by the law, and so can be characterized as internal concepts. Either way, there is an assumption that legal rules have some causal efficacy in advancing interests. This is what is sometimes called an instrumental view of law. 38 While it is not the only view on offer, we adopt it for present purposes. We need not offer an absolute defense of the instrumental view, even if we are partial to it; the reader need accept only that it is a common view.

Causation is a good example of a concept that is used in both law and social science, in slightly different ways. Causation in social science is essentially conceived of in probabilistic terms. 39 If we say that X causes Y , we are saying that a change in the value of X will likely be associated with a change in the value of Y , holding all else constant. The tools of social science, and the rules of inference, are designed to help identify such relationships. In contrast, legal causation is more normative, focusing on the kinds of responsibility for harms that warrant liability and the kinds that do not. 40

Other examples of causal legal relationships abound. When we ask if a regulation constitutes a taking of property (or an indirect expropriation, to use the international law term), we want to know whether a change in the level of regulation would lead to a change in one’s ability to use the property to the point that the owner should receive compensation. 41 When we ask whether a policy has a discriminatory impact on a group under the Fair Housing Act 42 or Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 43 we need to identify baseline levels of demographic concentration, and then ask whether a different policy would lead to a different level of treatment for the group. 44 We also want to compare alternative policies. Is it the case that once a particular level of impact is reached, one can stop the inquiry? Or is it a matter of cost-benefit analysis, such that increases in the impact may be outweighed by benefits on the other side? If so, does the disparate impact increase in a linear way with increments of the policy? These types of questions are rarely considered by lawyers or judges, who use causal language in a more heuristic way.

As these examples suggest, recognizing that legal concepts often involve relationships implies that we ought to favor concepts whose connections can in fact be identified and established. This is because such concepts can in principle be applied in consistent and precise ways across cases. While we know that not every concept can be captured by a real-world indicator or variable, we still think it valuable for lawyers and judges to focus on relationships for which the basic logic of X and Y holds.

Of course, the fact that not every relationship between concepts can be measured poses challenges for certain analyses. For instance, legal philosophers have wrestled with the idea of incommensurability, “the absence of a scale or metric.” 45 When values are not capable of being arrayed on a single scale, we think of them as incommensurable. Thinking about relationships that in principle can be ordered and tested on the same scale will, ceteris paribus, make the law more tractable. Similarly, the idea of outright necessity is subtly different from the more feasible notions of causation and correlation. Proving that only X can achieve Y is much more difficult—in fact, impossible in many contexts—than showing that X is one of the factors that drive Y .

II. Conceptualizing Constitutional Law

To reiterate the discussion to this point: Social scientists have developed reasonably determinate criteria for distinguishing between effective and ineffective concepts, and between conceptual relationships that can and cannot be demonstrated. In brief, the hallmarks of effective concepts are resonance, domain specificity, consistency, fecundity, differentiation from other concepts, causal utility, and, above all, measurability. Similarly, conceptual relationships involving correlation or causality are more easily established than ones involving necessity or the weighing of incommensurable quantities.

How well does law perform under these criteria? Are its concepts and conceptual relationships satisfactory or in need of improvement? These questions are far too broad to be answered fully here, but we begin to address them using a series of examples from American constitutional law. These examples include both poor concepts and relationships (for which we suggest improvement) and effective ones (for which we explain why they are useful). Constitutional law also strikes us as an unusually fertile field to plow for illustrations. It is a subject that brims with concepts and complex linkages among them. These concepts and linkages are largely (though not entirely) judicially created, meaning that they can be revised by the courts as well. And, not unimportantly for a project that potentially implicates law’s entire empire, constitutional law is a discrete domain with which we are relatively familiar.

A. Poor Concepts

Before labeling any concept as poor, we must note a number of caveats. First, our tags are based not on a rigorous examination of all constitutional concepts (a daunting task to say the least), but rather on an impressionistic survey of several high-profile areas. In other words, we do not claim to have identified the worst (or best) concepts, but only a few concepts that mostly fail (or satisfy) the social scientific criteria for conceptualization. Second, our treatment of each concept is necessarily brief. We hit what we see as the essential points, but we cannot grapple here with each concept’s full complexity. And third, though our mode is diagnostic, criticizing certain concepts and praising others, our ultimate aim is prescriptive. That is, we are interested in contemplating how constitutional law might look if its concepts were more effective—and in finding ways to push the doctrine in that direction.

Having disposed of these preliminaries, corruption is our first example of a concept that we regard as unhelpful. The prevention of corruption is the only justification the Supreme Court has recognized for burdening First Amendment rights by restricting the financing of political campaigns. 46 Corruption is also unquestionably a resonant and fecund concept, in that it is intuitively undesirable to most observers and conveys a rich array of negative meanings. This rich array, though, is part of the problem. Precisely because corruption can mean many different things, the term can be—and has been—defined in many different ways. 47 The Court, in particular, has toggled back and forth between three conceptions: a narrower version limited to explicit quid pro quos, or overt exchanges of money for official governmental acts; 48 a broader version covering funders’ access to and influence over officeholders; 49 and a still more expansive version extending to the distortion of electoral outcomes due to corporate spending. 50

In terms of the social scientific criteria, these shifting notions mean that corruption lacks domain specificity, consistency, and differentiation from other concepts. Domain specificity is missing because the narrower version applies to only the restriction of campaign contributions, while the two broader versions justify the limitation of campaign expenditures as well. 51 Consistency is absent for the obvious reason that the Court has adopted three in consistent definitions of corruption in the span of just a single generation. And depending on how it is construed, corruption bleeds into bribery (whose trademark is the quid pro quo exchange), skewed representation (responsive to funders rather than voters), or inequality (in electoral influence). 52

One might respond that most of these difficulties would be avoided if the Court could only settle on a single notion of corruption. But there is no easy way in which the Court could do so because, as several scholars have pointed out, corruption is a derivative concept that becomes intelligible only through an antecedent theory of purity for the entity at issue. 53 With respect to legislators, for example, one can say they are corrupt only if one first has an account of how they should behave when they are pure. One thus needs a model of representation before one can arrive at a definition of legislative corruption—a definition that would correspond to deviation from this model. Of course, the Court could choose to embrace a particular representational approach, but this is hardly a straightforward matter, and it is one in which the Court has evinced no interest to date.

Moreover, even if the Court somehow managed to stick to a single notion of corruption, it would run into further issues of measurability and causal utility. These issues stem from the covert nature of most corrupt activities. When politicians trade votes for money, they do so in secret. When officeholders merely offer access or influence to their funders, they again do so as furtively as possible. Precisely for these reasons, social scientists have rarely been able to quantify corruption itself, resorting instead to rough proxies such as people’s trust in government 54 and the volume of public officials convicted of bribery. 55 Unsurprisingly, given the crudity of these metrics, no significant relationships have been found between campaign finance regulation and corruption. 56 Greater regulation seems neither to increase people’s faith in their rulers nor to reduce the number of officials taken on perp walks.

Thanks to its poor performance on almost every criterion, we consider corruption to be an unsalvageable concept. It has not been, nor can it be, properly defined or measured. If it were abandoned, though, what would take its place in the campaign finance case law? We see two options. Less controversially, corruption could be swapped for one of the concepts into which it blurs, such as bribery. More provocatively (because further doctrinally afield), campaign finance regulation could be justified based on its promotion of distinct values such as electoral competitiveness, voter participation, or congruence with the median voter’s preferences. 57 This is not the place to defend these values, though offhand all seem more tractable than corruption. Our point, rather, is that when a particular concept is unworkable, it is often possible to replace it with a more suitable alternative.

We turn next to our second example of a flawed constitutional concept: political powerlessness , which is one of the four indicia of suspect class status under equal protection law. 58 Like corruption, powerlessness is a self-evidently resonant and fecund concept. To say that a group is powerless is to say something important about it, to convey a great deal of information about the group’s position, organization, and capability. Also, as with corruption, the amount of information conveyed is a bug, not a feature. The many inferences supported by powerlessness give rise to many definitions of the term by the Court, including a group’s small numerical size, inability to vote, lack of descriptive representation, low socioeconomic status, and failure to win the passage of protective legislation. 59

And again as with corruption, these multiple notions of powerlessness sap the concept of consistency and differentiation from other concepts. The inconsistency is obvious; the notions of powerlessness are not just multiple, but also irreconcilable. 60 Depending on how it is defined, powerlessness also becomes difficult to distinguish from concepts such as disenfranchisement, underrepresentation, and even poverty. And while the different conceptions of powerlessness do not directly undermine its domain specificity, this criterion is not satisfied either, due to the uncertainty over how powerlessness relates to the other indicia of suspect class status. It is unclear whether powerlessness is a necessary, sufficient, or merely conducive condition for a class to be deemed suspect. 61

However, unlike with corruption, a particular definition of powerlessness may be theoretically compelled—and is certainly not theoretically precluded. The powerlessness factor has its roots in United States v Carolene Products Co ’s 62 account of “those political processes ordinarily to be relied upon to protect minorities.” 63 “Those political processes,” in turn, refer to pluralism: the idea that society is divided into countless overlapping groups, from whose shifting coalitions public policy emerges. 64 And pluralism implies a specific notion of group power: one that is continuous rather than binary, spans all issues, focuses on policy enactment, and controls for group size and type. 65 Thus, powerlessness not only can, but arguably must, be conceived of in a certain way if it is to remain true to its pluralist pedigree.

Furthermore, if powerlessness is so understood, it becomes possible to measure and apply it. Social scientists have compiled extensive data on both the policy preferences of different groups and whether these preferences are realized in enacted law. 66 Combining this information, a group’s odds of getting its preferred policies passed can be determined, adjusted for the group’s size, and then compared to the odds of other groups. 67 This method yields the conclusions that blacks and women (both already suspect classes) are relatively powerless compared to whites and men. 68 Interestingly, it also indicates that the poor (not currently a suspect class) have far less clout than the middle class and the wealthy. 69

Because powerlessness can be—even though it has not been—defined and measured properly, we come to a different verdict for it than for corruption. That is, we recommend discarding the Court’s various notions of it and replacing them with the pluralist conception outlined above. Considering corruption and powerlessness in tandem also allows us to hazard a guess as to why the Court sometimes adopts faulty concepts. In both of these (potentially unrepresentative) cases, the Court borrowed complex ideas from democratic theory without fully grasping the ideas’ internal logic. At best (as with powerlessness), this approach leads to the circulation of numerous definitions of the concept, one of which is eventually found to be theoretically and practically defensible. At worst (as with corruption), the approach causes multiple definitions to be bandied about, none of which is theoretically legitimate or capable of being operationalized. Plainly, this is a far cry from textbook concept formation.

B. Effective Concepts

We doubt that the Court ever complies perfectly with any social scientific textbook. But the Court does, on occasion, recognize constitutional concepts that are significantly more effective than the ones analyzed to this point. As a first example of a successful concept, take partisan symmetry , which five justices tentatively endorsed in a recent case as a potential foundation for a test for partisan gerrymandering. 70 Partisan symmetry “requires that the electoral system treat similarly-situated parties equally,” so that they are able to convert their popular support into legislative representation with approximately equal ease. 71 The Court cautiously backed symmetry only after struggling for decades with—and ultimately rejecting—a host of other possible linchpins for a gerrymandering test: seat-vote proportionality (inconsistent with single-member districts), predominant partisan intent (too difficult to discern), district noncompactness (not itself a meaningful value), and so on. 72

Partisan symmetry performs suitably well along all of the relevant dimensions. It is resonant and fecund because it captures the core harm of gerrymandering: a district plan that enables one party to translate its votes into seats more efficiently than its rival. 73 It is limited to the domain of electoral systems. It is defined identically in both the case law and the academic literature. 74 It is distinct from the other concepts the Court has considered in this area—including proportionality, which is a property that symmetric plans may, but need not, exhibit. 75 It is measurable using easily obtained electoral data and well-established statistical techniques. 76 And it is useful in that it conveys in a single figure the direction and extent of a plan’s partisan skew.

However, we do not mean to claim that partisan symmetry is a flawless concept. It does not take into account odd district shape or partisan motivation, both aspects of gerrymandering as the practice is commonly understood. Its calculation requires fairly strong assumptions about uncontested races and shifts in the statewide vote. 77 Two different symmetry metrics exist, which usually but not always point in the same direction. 78 And to form a workable test for gerrymandering, symmetry must be combined with other prongs, thus somewhat diminishing its utility. Somewhat , though, is the key word here. Symmetry is not a perfect concept; no concept is. But symmetry can be defined, measured, and applied coherently, which is the most the law can ask of a concept.

Our second example of an effective concept, racial polarization in voting , has had a doctrinal history similar to that of partisan symmetry. Between the early 1970s and the mid-1980s, the Court struggled to identify the exact problem with racial vote dilution (the reduction of minorities’ electoral influence through means other than burdening the franchise). 79 Unable to crystallize the issue, the Court instead laid out a dozen factors that were meant to be analyzed in unison to determine liability. 80 This unwieldy doctrinal structure finally collapsed in 1986, when the Court held that plaintiffs had to prove racial polarization in order to prevail. 81 The Court also carefully defined polarization as “the situation where different races . . . vote in blocs for different candidates.” 82

Like partisan symmetry, racial polarization in voting complies reasonably well with all of the social scientific criteria for conceptualization. It is resonant and fecund because it reflects the reality that racial vote dilution is possible only under polarized electoral conditions. If polarization does not exist, then neither can a minority group prefer a distinct candidate, nor can the majority thwart a minority-preferred candidate’s election. 83 It is limited to the field of vote dilution, not even extending to the adjacent area of vote denial. 84 It is understood in the same way by both judges and scholars. 85 It is different from other important vote dilution concepts like a minority group’s geographic compactness and elected officials’ responsiveness to the group’s concerns. 86 It is measurable by applying ecological regression techniques to election results and demographic data. 87 And it is useful because it is both the mechanism that drives vote dilution and a metric reducible to a single number.

But also like partisan symmetry, racial polarization in voting has its warts too. Not all commentators agree that it is troublesome when it is caused by forces other than racial prejudice, such as differences in partisanship or socioeconomic status. 88 Nor is there consensus that polarization in voting is the quantity of interest, as some scholars emphasize polarization in policy preferences instead. 89 Furthermore, courts have never resolved how extreme polarization must be to establish liability. And almost from the day polarization became a requirement, it has been clear that its measurement is complicated by residential integration, the presence of more than two racial groups, and the inevitable endogeneity of election results (above all, to the particular candidates competing). 90 All of these shortcomings, though, strike us as fixable rather than fatal. This also has been the judgment of the judiciary, which has productively analyzed polarization in hundreds of cases since 1986. 91

As before, we are wary of generalizing based on only a pair of cases. But considered together, partisan symmetry and racial polarization in voting suggest that the Court does better when it turns for concepts to empirical political science than to high democratic theory. Before they ever appeared in the Court’s case law, symmetry and polarization had been precisely defined and then measured using large volumes of data as well as methods that steadily improved over time. 92 These properties meant that when the ideas came to the Court’s attention, they were ready for prime time. They were not lofty abstractions that had yet to be made concrete, but rather practical concepts whose scope and calculation were already established. Our view is that this approach—adopting concepts previously formulated and refined by empirical social scientists—is generally advisable. It lets the Court benefit from the efforts of other disciplines, while avoiding reliance on concepts articulated at too high a level of generality to be legally useful.

C. Poor Relationships

We turn next to examples of poor and effective conceptual relationships in constitutional law. We also reiterate our earlier caveats: that the cases we highlight are not necessarily representative, that our discussion of each case is relatively brief, and that we mean for our descriptive analysis to have normative implications for the structure of constitutional doctrine.

That said, the narrow tailoring requirement of strict scrutiny is our first example of an unhelpful constitutional relationship. As a formal matter, this requirement states that, to survive review, a challenged policy must be “necessary” 93 or “the least restrictive means” 94 for furthering a compelling governmental interest. In practice, the requirement is implemented sometimes in this way and sometimes by balancing the harm inflicted by a policy against the degree to which it advances a compelling interest—with a heavy thumb on the harm’s side of the scale. 95 Narrow tailoring is ubiquitous in constitutional law, applying to (among other areas) explicit racial classifications, 96 policies that burden rights recognized as fundamental under the Due Process Clause, 97 and measures that regulate speech on the basis of its content. 98

The fundamental problem with narrow tailoring is that there is no reliable way to tell whether a policy is actually necessary or the least restrictive means for promoting a given interest. Social scientific techniques are very good at determining whether a means is related (that is, correlated) to an end. They are also reasonably adept at assessing causation, though this is a more difficult issue. Other variables that might be linked to the end can be controlled for, and all kinds of quasi-experimental approaches can be employed. 99 But social scientific techniques are largely incapable of demonstrating necessity. A mere correlation does not even establish causation, let alone that a policy is the least restrictive means for furthering an interest. Even when causation is shown, it always remains possible that a different policy would advance the interest at least as well. Not every conceivable control can be included in a model, and the universe of policy alternatives is near infinite as well. In short, the gold standard of social science is proving that X causes Y —but this proof cannot guarantee that some other variable does not drive Y to an even greater extent. 100

A somewhat different critique applies to the balancing that courts sometimes carry out instead of means-end analysis. Here, the trouble is that the quantities being compared—the harm inflicted by a policy, either by burdening certain rights or by classifying groups in certain ways, and the policy’s promotion of a compelling governmental interest—are incommensurable, in the sense we outlined earlier. Social science has little difficulty with the comparison of quantities that are measured using the same scale. Familiar techniques such as factor analysis also enable quantities measured using different scales to be collapsed into a single composite variable. 101 But there is little that social science can do when the relevant quantities are measured differently, cannot be collapsed, and yet must be weighed against each other. This kind of inquiry, as Justice Antonin Scalia once wrote, is akin to “judging whether a particular line is longer than a particular rock is heavy.” 102 Instinct and intuition may assist in answering the question, but more rigorous methods are unavailing.

These faults of narrow tailoring seem irremediable to us. It is simply infeasible to have to determine a policy’s necessity or whether its harms are offset by its incommensurable benefits. Fortunately, an obvious alternative exists: the means-end analysis that courts conduct when they engage in intermediate scrutiny. In these cases, courts ask whether a policy is “substantially related” to the achievement of an important governmental objective. 103 A substantial relationship means either a substantial correlation or, perhaps, a causal connection. 104 Either way, the issue is squarely in the wheelhouse of social science, whose forte is assessing correlation and causation. We therefore recommend exporting this aspect of intermediate scrutiny to the strict scrutiny context—perhaps with an additional twist or two to keep the latter more rigorous than the former. For instance, a strong rather than merely substantial relationship could be required, or a large impact on the relevant governmental goal.

Our second example of a poor constitutional relationship is the undue burden test that applies to regulations of abortion, voting, and (when enacted by states) interstate commerce. 105 In all of these areas, a law is invalid if it imposes an undue burden on the value at issue: the right to an abortion, 106 the right to vote, 107 or the free flow of interstate commerce. 108 An initial problem with this test is the ambiguity of its formulation. It is unclear whether “undue” contemplates a link between a challenged policy and a governmental interest and, if so, what sort of link it requires. Precisely because of this ambiguity, no consistent definition exists of an undue burden. Instead, courts use different versions of the test, even within the same domain, of varying manageability.

For example, an undue burden is sometimes treated as synonymous with a significant burden. “A finding of an undue burden is a shorthand for the conclusion that a state regulation . . . plac[es] a substantial obstacle in the path of a woman seeking an abortion,” declared the joint opinion in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v Casey . 109 If an undue burden is understood in this way, we have no quarrel with it. The magnitude of a burden is measurable, at least in principle, and does not involve a policy’s connection with a governmental interest. It is a concept rather than a conceptual relationship.

On the other hand, an undue burden is sometimes construed as one that is unnecessary to achieve a legitimate governmental objective. The Casey joint opinion articulated the test in these terms as well: “Unnecessary health regulations that . . . present[ ] a substantial obstacle to a woman seeking an abortion impose an undue burden on the right.” 110 So conceived, an undue burden falls victim to our earlier criticism of narrow tailoring. That is, there is no good way to tell whether a policy is the least restrictive means for accomplishing a given goal, meaning that there is also no good way to tell whether the burden imposed by the policy is undue.

On still other occasions, the undue burden test devolves into judicial balancing, with the severity of a policy’s burden weighed against the degree to which the policy promotes governmental interests. The burden is then deemed undue if it fails this cost-benefit analysis. As the Court has stated in the Dormant Commerce Clause context, where it “has candidly undertaken a balancing approach in resolving these issues,” a policy “will be upheld unless the burden imposed on such commerce is [ ] excessive in relation to the putative local benefits.” 111 Plainly, this formulation is also vulnerable to our challenge to narrow tailoring. Burdens on abortion, voting, or interstate commerce are no more commensurable with gains in governmental interests than are other types of rights burdens or the harms of racial classifications. Balancing under narrow tailoring is indistinguishable from balancing under an undue burden test.

Because several notions of an undue burden percolate in the case law, doctrinal progress is possible here without wholesale rejection of the status quo. 112 Instead, courts need discard only the versions that entail least-restrictive-means or balancing analyses, leaving them with the approach that equates an undue with a significant burden. Judicial scrutiny could then vary based on a burden’s magnitude, with a severe burden leading to more stringent review and a lighter imposition prompting a more relaxed appraisal. This is already the method that courts most commonly use in the voting context, 113 and it could be extended to the abortion and Dormant Commerce Clause domains—preferably with our amendment to strict scrutiny stripping it of its narrow tailoring prong.

D. Effective Relationships

In still other areas, no doctrinal revisions seem necessary because the existing conceptual relationships work well enough already. As a first example of effective relationships, take the traceability and redressability elements of standing. After appearing intermittently in the case law for years, these elements were constitutionalized in Lujan v Defenders of Wildlife . 114 A plaintiff’s injury must be “fairly traceable to the challenged action of the defendant,” meaning that “there must be a causal connection between the injury and the conduct complained of.” 115 Additionally, “it must be likely, as opposed to merely speculative, that the injury will be redressed by a favorable decision.” 116

Traceability and redressability are often analyzed together; in fact, “[m]ost cases view redressability as an essentially automatic corollary of [traceability].” 117 Both relationships are also highly tractable because they explicitly require causation, which is precisely the kind of link that social science is able to demonstrate. The essential traceability issue is whether the defendant’s challenged action caused the plaintiff’s harm. Similarly, the crux of redressability is whether the plaintiff’s desired remedy will cause her harm to be cured. These are pure matters of causation, undiluted by any hint of means-end necessity or incommensurable balancing.

Given that standing doctrine is often deemed “[e]xtremely fuzzy and highly manipulable,” 118 some readers may be surprised by our favorable account. We do not mean to suggest that the causal questions posed by the doctrine—what impact certain measures have had or will have on a plaintiff—are easy to answer. The data needed to address these issues is often unavailable (or uncited), forcing courts to rely on their qualitative judgment. Even when rigorous evidence exists, there is no guarantee that courts will take it into account. Our claim, then, is only that the traceability and redressability elements are appealing in principle because of their emphasis on causation. In practice, the necessary causal inquiries may be difficult to conduct, or overlooked even when they are feasible.

Fewer of these caveats are required for our second example of a successful constitutional relationship: the Necessary and Proper Clause , which authorizes Congress to enact any laws that are “necessary and proper for carrying into Execution” its enumerated powers. 119 At first glance, the Clause appears to exemplify a poor relationship because it stipulates that a law must be “necessary” to be permissible. But the Court has held that “‘necessary’ does not mean necessary” in this context. 120 Instead, it means “convenient, or useful or conducive to the authority’s beneficial exercise.” 121 Under this standard, a law will be upheld if it “constitutes a means that is rationally related to the implementation of a constitutionally enumerated power.” 122

So construed, the Necessary and Proper Clause essentially demands that a statute be correlated with the promotion of a textually specified goal. That is, the statute must make the goal’s achievement at least somewhat more likely, or must lead to at least a somewhat higher level of the goal. Needless to say, it is relatively straightforward to identify a correlational link between a means and an end. Doing so, in fact, is one of the simpler tasks that can be asked of social science. This is why we approve of the sort of relationship that must be demonstrated under the Clause; it is the sort whose existence can be proven or rebutted with little room for debate.

However, we note that the Court has recently begun to revive the “Proper” in “Necessary and Proper”—and to infuse into it requirements other than a means-end correlation. In National Federation of Independent Business v Sebelius , 123 in particular, the Court held that the Clause authorizes neither the exercise of “great” (as opposed to “incidental”) powers, nor the passage of “laws that undermine the structure of government established by the Constitution.” 124 We regard these developments as unfortunate. Both the significance of a power and a law’s consistency with our constitutional structure are normative matters that are poorly suited to empirical examination. The insertion of these issues into the doctrine has blurred what was previously an admirably clear relational picture.

Our inquiry into the social scientific disciplines of conceptualization and measurement suggests that they may have rich payoffs for lawyers. (To use a recurring term from our discussion, they are fecund.) Examining legal doctrines through the lens of conceptualization, we argue, allows us to evaluate what are good and bad concepts and relationships in law. We draw on one set of social science criteria for good concepts, which includes that they are resonant, have a stipulated domain, can be applied consistently, are fecund, are distinct from neighboring concepts, are useful, and can in principle be measured. Similarly, good relationships are those that involve causation or correlation, but not necessity or the weighing of incommensurable values.

We emphasize the criterion of potential measurability, which is another way of saying that courts should recognize concepts and relationships that are in principle verifiable. While in many cases this would be difficult to achieve in practice, the discipline of thinking in terms of whether X and Y can be reliably assessed, and whether X is linked to Y , would, we suspect, lead courts to greater consistency and thus predictability. In particular, our analysis suggests that courts should shy away from complex multipart tests that involve the ad hoc balancing of incommensurables. 125 Just as social scientists require dependable measures across cases, legal doctrines that are measurable can be subjected to productive scrutiny, potentially leading to more coherent application of the law. In short, important rule-of-law values can be advanced through an approach to law that draws on what some might see as an unlikely source—social scientific thinking.

- 10 See Goertz, Social Science Concepts at 28–30 (cited in note 5); Gerring, Social Science Methodology at 112–13 (cited in note 5).

- 11 The debate goes back to Aristotle. See Gerring, Social Science Methodology at 114–15 (cited in note 5). See also Eric Margolis and Stephen Laurence, Concepts (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, May 17, 2011), online at http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/ win2012/entries/concepts (visited Dec 28, 2016) (Perma archive unavailable).

- 12 See Margolis and Laurence, Concepts (cited in note 11).

- 13 Goertz, Social Science Concepts at 5 (cited in note 5).

- 14 See Ecuador Const Art 71, translation archived at http://perma.cc/DKJ5-E3K8 (“Nature, or Pacha Mama, where life is reproduced and occurs, has the right to integral respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its life cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes.”).

- 15 See Gerring, Social Science Methodology at 136–37 (cited in note 5), citing Max Weber, The Methodology of the Social Sciences 90 (Free Press 1949) (Edward A. Shils and Henry A. Finch, eds and trans).

- 16 Goertz, Social Science Concepts at 36 (cited in note 5).

- 17 Margolis and Laurence, Concepts (cited in note 11).

- 18 Cottrill v Sparrow, Johnson & Ursillo, Inc , 100 F3d 220, 225 (1st Cir 1996).

- 19 See Gerring, Social Science Methodology at 117–19 (cited in note 5). See also John Gerring, What Makes a Concept Good? A Criterial Framework for Understanding Concept Formation in the Social Sciences , 31 Polity 357, 367 (1999) (offering a slightly different set of criteria).

- 20 See Gerring, Social Science Methodology at 117 (cited in note 5) (listing Gerring’s criteria of conceptualization).

- 21 See id at 117–19.

- 22 See id at 119–21.

- 23 See id at 121–24.

- 24 Gerring, Social Science Methodology at 124 (cited in note 5).

- 25 See id at 124–26.

- 26 See Barbara Geddes, Paradigms and Sand Castles: Theory Building and Research Design in Comparative Politics 50–53 (Michigan 2003).

- 27 See José Antonio Cheibub, Presidentialism, Parliamentarism, and Democracy 26–48 (Cambridge 2007).

- 28 See Gerring, Social Science Methodology at 127–30 (cited in note 5).

- 29 See id at 127.

- 30 See Catharine A. MacKinnon, Sexual Harassment of Working Women: A Case of Sex Discrimination 57–59 (Yale 1979) (discussing whether sexual harassment fits neatly into the sex discrimination category).

- 31 See Gerring, Social Science Methodology at 130–31 (cited in note 5).

- 32 See Goertz, Social Science Concepts at 4 (cited in note 5) (noting that the key features are relevance “for hypotheses, explanations, and causal mechanisms”).

- 33 See Gerring, Social Science Methodology at 156–57 (cited in note 5).

- 34 See Cottrill , 100 F3d at 225.

- 35 See Goertz, Social Science Concepts at 6 (cited in note 5).

- 36 See Wesley Newcomb Hohfeld, Fundamental Legal Conceptions as Applied in Judicial Reasoning , 26 Yale L J 710, 710 (1917).

- 37 See id at 710, 716–17.

- 38 See Alon Harel, Why Law Matters 46 (Oxford 2014).

- 39 See Ellery Eells, Probabilistic Causality 34–35 (Cambridge 1991).

- 40 But see Antony Honoré, Causation in the Law (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Nov 17, 2010), online at http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/causation-law (visited Jan 23, 2017) (Perma archive unavailable) (noting the complexity of the relationship between causing harm and legal responsibility).

- 41 See Lucas v South Carolina Coastal Council , 505 US 1003, 1027 (1992) (discussing under what circumstances a state “may resist compensation” for “regulation that deprives land of all economically beneficial use”).

- 42 Pub L No 90-284, 82 Stat 81 (1968), codified as amended at 42 USC § 3601 et seq.

- 43 Pub L No 88-352, 78 Stat 252, codified as amended at 42 USC § 2000d et seq.

- 44 See Metropolitan Housing Development Corp v Village of Arlington Heights , 558 F2d 1283, 1290–91 (7th Cir 1977).

- 45 Matthew Adler, Law and Incommensurability: Introduction , 146 U Pa L Rev 1169, 1170 (1998).

- 46 See McCutcheon v Federal Election Commission , 134 S Ct 1434, 1450 (2014) (Roberts) (plurality).

- 47 See, for example, Thomas F. Burke, The Concept of Corruption in Campaign Finance Law , 14 Const Commen 127, 128–35 (1997) (discussing three academic and three judicial definitions of corruption); Yasmin Dawood, Classifying Corruption , 9 Duke J Const L & Pub Pol 103, 106–32 (2014) (going through ten separate notions of corruption).

- 48 See, for example, McCutcheon , 134 S Ct at 1450 (Roberts) (plurality) (“Congress may target only a specific type of corruption[,] . . . large contributions that are given to secure a political quid pro quo from current and potential office holders.”) (quotation marks and brackets omitted).

- 49 See, for example, McConnell v Federal Election Commission , 540 US 93, 150 (2003) (“Congress’ legitimate interest extends beyond preventing simple cash-for-votes corruption to curbing undue influence on an officeholder’s judgment, and the appearance of such influence.”) (quotation marks omitted).

- 50 See, for example, Austin v Michigan State Chamber of Commerce , 494 US 652, 660 (1990) (recognizing “a different type of corruption in the political arena: the corrosive and distorting effects of immense aggregations of wealth that are accumulated with the help of the corporate form”).

- 51 Compare Citizens United v Federal Election Commission , 558 US 310, 361 (2010), with McConnell , 540 US at 203, and Austin , 494 US at 660.

- 52 As should be clear from this discussion, our critique is not that the Court has used inconsistent words to describe the same underlying concept . Rather, each of the Court’s definitions of corruption corresponds to an entirely different notion of what it means for elected officials to be corrupt.

- 53 See, for example, Burke, 14 Const Commen at 128 (cited in note 47) (“When corruption is proclaimed in political life it presumes some ideal state.”); Deborah Hellman, Defining Corruption and Constitutionalizing Democracy , 111 Mich L Rev 1385, 1389 (2013) (“[C]orruption is a derivative concept, meaning it depends on a theory of the institution or official involved.”).

- 54 See, for example, Nathaniel Persily and Kelli Lammie, Perceptions of Corruption and Campaign Finance: When Public Opinion Determines Constitutional Law , 153 U Pa L Rev 119, 145–48 (2004). See also Corruption Perceptions Index 2015 (Transparency International, Feb 1, 2016), archived at http://perma.cc/C4XQ-6CE3.

- 55 See, for example, Adriana Cordis and Jeff Milyo, Do State Campaign Finance Reforms Reduce Public Corruption? *11–16 (unpublished manuscript, Jan 2013), archived at http://perma.cc/9KRP-FC9C.

- 56 See id at *21–28; Persily and Lammie, 153 U Pa L Rev at 148–49 (cited in note 54).

- 57 As to the last of these values, see generally Nicholas O. Stephanopoulos, Aligning Campaign Finance Law , 101 Va L Rev 1425 (2015).

- 58 Political powerlessness was first recognized as a factor in San Antonio Independent School District v Rodriguez , 411 US 1, 28 (1973).

- 59 See Nicholas O. Stephanopoulos, Political Powerlessness , 90 NYU L Rev 1527, 1537–42 (2015) (discussing the various judicial versions of powerlessness).

- 60 See id at 1540 (“The crucial point about these definitions is that they are entirely inconsistent with one another.”). Accordingly, these are not just different ways of expressing the same underlying idea; rather, they are divergent accounts of what it means to be powerless in the first place. See note 52.

- 61 See, for example, Varnum v Brien , 763 NW2d 862, 888 (Iowa 2009) (pointing out “the flexible manner in which the Supreme Court has applied the four factors [relevant to suspect class status]”).

- 62 304 US 144 (1938).

- 63 Id at 152 n 4.

- 64 See Bruce A. Ackerman, Beyond Carolene Products, 98 Harv L Rev 713, 719 (1985) (“[G]enerations of American political scientists have filled in the picture of pluralist democracy presupposed by Carolene ’s distinctive argument for minority rights.”).

- 65 See Stephanopoulos, 90 NYU L Rev at 1549–54 (cited in note 59) (making this argument at length).

- 66 See, for example, Martin Gilens, Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America 57–66 (Princeton 2012).

- 67 See, for example, id at 77–87.

- 68 See Stephanopoulos, 90 NYU L Rev at 1583–84, 1590–92 (cited in note 59).

- 69 See, for example, Gilens, Affluence and Influence at 80–81 (cited in note 66); Patrick Flavin, Income Inequality and Policy Representation in the American States , 40 Am Polit Rsrch 29, 40–44 (2012).

- 70 See League of United Latin American Citizens v Perry , 548 US 399, 420 (2006) (Kennedy) (plurality) (“LULAC”); id at 466 (Stevens concurring in part and dissenting in part); id at 483 (Souter concurring in part and dissenting in part); id at 492 (Breyer concurring in part and dissenting in part).

- 71 Id at 466 (Stevens concurring in part and dissenting in part).

- 72 See Vieth v Jubelirer , 541 US 267, 285–86 (2004) (Scalia) (plurality).

- 73 See id at 271 n 1 (Scalia) (plurality) (noting that gerrymandering has been defined as “giv[ing] one political party an unfair advantage by diluting the opposition’s voting strength”).

- 74 Compare LULAC , 548 US at 466 (Stevens concurring in part and dissenting in part), with Bernard Grofman and Gary King, The Future of Partisan Symmetry as a Judicial Test for Partisan Gerrymandering after LULAC v. Perry, 6 Election L J 2, 6 (2007).

- 75 See Grofman and King, 6 Election L J at 8 (cited in note 74) (“Measuring symmetry . . . does not require ‘proportional representation’ (where each party receives the same proportion of seats as it receives in votes).”).

- 76 See id at 10 (noting that symmetry is measured using “highly mature statistical methods [that] rely on well-tested and well-accepted statistical procedures”).

- 77 See LULAC , 548 US at 420 (Kennedy) (plurality) (criticizing partisan bias because it “may in large part depend on conjecture about where possible vote-switchers will reside”); Nicholas O. Stephanopoulos and Eric M. McGhee, Partisan Gerrymandering and the Efficiency Gap , 82 U Chi L Rev 831, 865–67 (2015) (discussing the imputation of results for uncontested races).

- 78 These are partisan bias, which is the divergence in the share of seats that each party would win given the same share of the statewide vote, see Grofman and King, 6 Election L J at 6 (cited in note 74), and the efficiency gap, which is “the difference between the parties’ respective wasted votes, divided by the total number of votes cast,” Stephanopoulos and McGhee, 82 U Chi L Rev at 851 (cited in note 77) (emphasis omitted).

- 79 See Samuel Issacharoff, Polarized Voting and the Political Process: The Transformation of Voting Rights Jurisprudence , 90 Mich L Rev 1833, 1844 (1992) (noting the “absence of an overriding conception of the precise constitutional harm the courts were seeking to remedy” in this period).

- 80 See White v Regester , 412 US 755, 765–70 (1973); Zimmer v McKeithen , 485 F2d 1297, 1305–07 (5th Cir 1973).

- 81 See Thornburg v Gingles , 478 US 30, 51 (1986). Importantly, while the pre- Gingles vote dilution cases were brought under the Fourteenth Amendment, dilution cases from Gingles onward have generally been launched under § 2 of the Voting Rights Act, codified at 52 USC § 10301.

- 82 Gingles , 478 US at 62 (Brennan) (plurality).

- 83 See, for example, Growe v Emison , 507 US 25, 40 (1993).

- 84 Minority voters can be disproportionately burdened by an electoral regulation (say, a photo identification requirement) whether or not they are polarized from the white majority.

- 85 The Gingles Court noted that “courts and commentators agree that racial bloc voting is a key element of a vote dilution claim,” Gingles , 478 US at 55, and endorsed the district court’s use of “methods standard in the literature for the analysis of racially polarized voting,” id at 53 n 20.

- 86 Geographic compactness is also a prerequisite for liability for vote dilution, while responsiveness is a factor to be considered at the later totality-of-circumstances stage. See id at 45, 50.

- 87 See id at 52–53 (referring to “two complementary methods of analysis—extreme case analysis and bivariate ecological regression analysis”).

- 88 See, for example, League of United Latin American Citizens, Council No 4434 v Clements , 999 F2d 831, 854 (5th Cir 1993) (en banc).

- 89 See, for example, Christopher S. Elmendorf and Douglas M. Spencer, Administering Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act after Shelby County, 115 Colum L Rev 2143, 2195–2215 (2015).