Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Developing Strong Thesis Statements

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The thesis statement or main claim must be debatable

An argumentative or persuasive piece of writing must begin with a debatable thesis or claim. In other words, the thesis must be something that people could reasonably have differing opinions on. If your thesis is something that is generally agreed upon or accepted as fact then there is no reason to try to persuade people.

Example of a non-debatable thesis statement:

This thesis statement is not debatable. First, the word pollution implies that something is bad or negative in some way. Furthermore, all studies agree that pollution is a problem; they simply disagree on the impact it will have or the scope of the problem. No one could reasonably argue that pollution is unambiguously good.

Example of a debatable thesis statement:

This is an example of a debatable thesis because reasonable people could disagree with it. Some people might think that this is how we should spend the nation's money. Others might feel that we should be spending more money on education. Still others could argue that corporations, not the government, should be paying to limit pollution.

Another example of a debatable thesis statement:

In this example there is also room for disagreement between rational individuals. Some citizens might think focusing on recycling programs rather than private automobiles is the most effective strategy.

The thesis needs to be narrow

Although the scope of your paper might seem overwhelming at the start, generally the narrower the thesis the more effective your argument will be. Your thesis or claim must be supported by evidence. The broader your claim is, the more evidence you will need to convince readers that your position is right.

Example of a thesis that is too broad:

There are several reasons this statement is too broad to argue. First, what is included in the category "drugs"? Is the author talking about illegal drug use, recreational drug use (which might include alcohol and cigarettes), or all uses of medication in general? Second, in what ways are drugs detrimental? Is drug use causing deaths (and is the author equating deaths from overdoses and deaths from drug related violence)? Is drug use changing the moral climate or causing the economy to decline? Finally, what does the author mean by "society"? Is the author referring only to America or to the global population? Does the author make any distinction between the effects on children and adults? There are just too many questions that the claim leaves open. The author could not cover all of the topics listed above, yet the generality of the claim leaves all of these possibilities open to debate.

Example of a narrow or focused thesis:

In this example the topic of drugs has been narrowed down to illegal drugs and the detriment has been narrowed down to gang violence. This is a much more manageable topic.

We could narrow each debatable thesis from the previous examples in the following way:

Narrowed debatable thesis 1:

This thesis narrows the scope of the argument by specifying not just the amount of money used but also how the money could actually help to control pollution.

Narrowed debatable thesis 2:

This thesis narrows the scope of the argument by specifying not just what the focus of a national anti-pollution campaign should be but also why this is the appropriate focus.

Qualifiers such as " typically ," " generally ," " usually ," or " on average " also help to limit the scope of your claim by allowing for the almost inevitable exception to the rule.

Types of claims

Claims typically fall into one of four categories. Thinking about how you want to approach your topic, or, in other words, what type of claim you want to make, is one way to focus your thesis on one particular aspect of your broader topic.

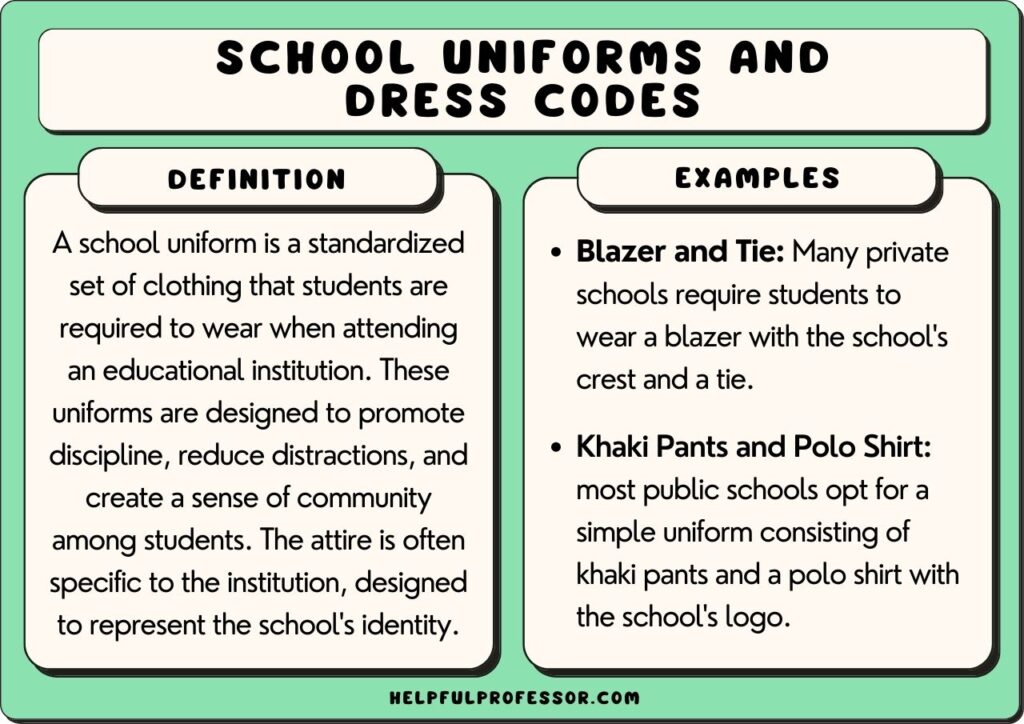

Claims of fact or definition: These claims argue about what the definition of something is or whether something is a settled fact. Example:

Claims of cause and effect: These claims argue that one person, thing, or event caused another thing or event to occur. Example:

Claims about value: These are claims made of what something is worth, whether we value it or not, how we would rate or categorize something. Example:

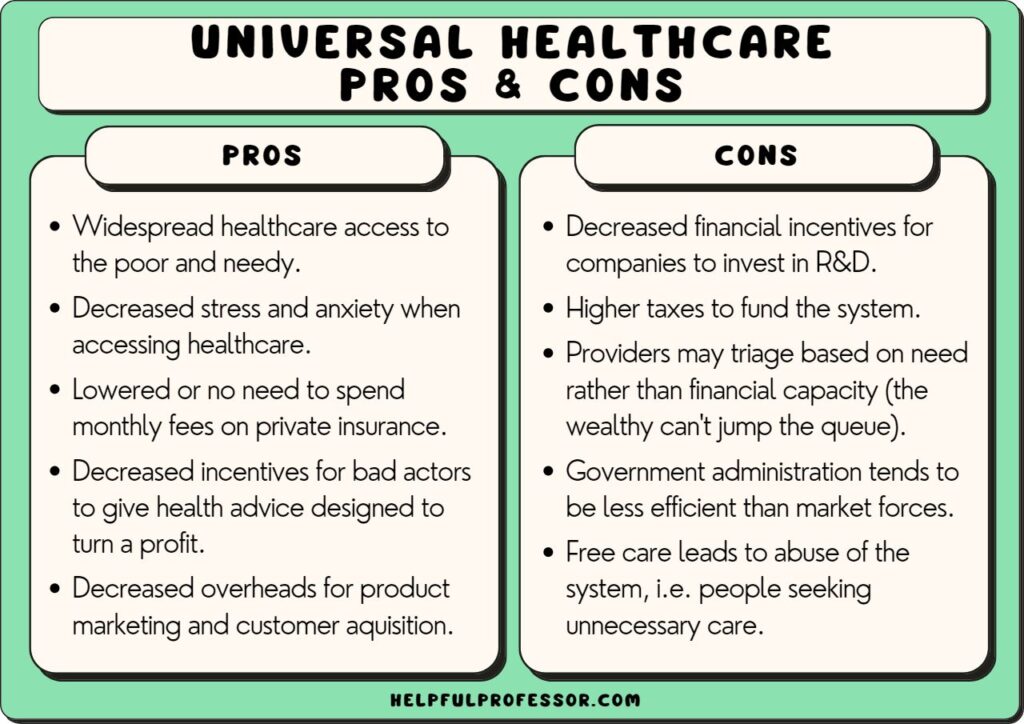

Claims about solutions or policies: These are claims that argue for or against a certain solution or policy approach to a problem. Example:

Which type of claim is right for your argument? Which type of thesis or claim you use for your argument will depend on your position and knowledge of the topic, your audience, and the context of your paper. You might want to think about where you imagine your audience to be on this topic and pinpoint where you think the biggest difference in viewpoints might be. Even if you start with one type of claim you probably will be using several within the paper. Regardless of the type of claim you choose to utilize it is key to identify the controversy or debate you are addressing and to define your position early on in the paper.

Think of yourself as a member of a jury, listening to a lawyer who is presenting an opening argument. You'll want to know very soon whether the lawyer believes the accused to be guilty or not guilty, and how the lawyer plans to convince you. Readers of academic essays are like jury members: before they have read too far, they want to know what the essay argues as well as how the writer plans to make the argument. After reading your thesis statement, the reader should think, "This essay is going to try to convince me of something. I'm not convinced yet, but I'm interested to see how I might be."

An effective thesis cannot be answered with a simple "yes" or "no." A thesis is not a topic; nor is it a fact; nor is it an opinion. "Reasons for the fall of communism" is a topic. "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" is a fact known by educated people. "The fall of communism is the best thing that ever happened in Europe" is an opinion. (Superlatives like "the best" almost always lead to trouble. It's impossible to weigh every "thing" that ever happened in Europe. And what about the fall of Hitler? Couldn't that be "the best thing"?)

A good thesis has two parts. It should tell what you plan to argue, and it should "telegraph" how you plan to argue—that is, what particular support for your claim is going where in your essay.

Steps in Constructing a Thesis

First, analyze your primary sources. Look for tension, interest, ambiguity, controversy, and/or complication. Does the author contradict himself or herself? Is a point made and later reversed? What are the deeper implications of the author's argument? Figuring out the why to one or more of these questions, or to related questions, will put you on the path to developing a working thesis. (Without the why, you probably have only come up with an observation—that there are, for instance, many different metaphors in such-and-such a poem—which is not a thesis.)

Once you have a working thesis, write it down. There is nothing as frustrating as hitting on a great idea for a thesis, then forgetting it when you lose concentration. And by writing down your thesis you will be forced to think of it clearly, logically, and concisely. You probably will not be able to write out a final-draft version of your thesis the first time you try, but you'll get yourself on the right track by writing down what you have.

Keep your thesis prominent in your introduction. A good, standard place for your thesis statement is at the end of an introductory paragraph, especially in shorter (5-15 page) essays. Readers are used to finding theses there, so they automatically pay more attention when they read the last sentence of your introduction. Although this is not required in all academic essays, it is a good rule of thumb.

Anticipate the counterarguments. Once you have a working thesis, you should think about what might be said against it. This will help you to refine your thesis, and it will also make you think of the arguments that you'll need to refute later on in your essay. (Every argument has a counterargument. If yours doesn't, then it's not an argument—it may be a fact, or an opinion, but it is not an argument.)

This statement is on its way to being a thesis. However, it is too easy to imagine possible counterarguments. For example, a political observer might believe that Dukakis lost because he suffered from a "soft-on-crime" image. If you complicate your thesis by anticipating the counterargument, you'll strengthen your argument, as shown in the sentence below.

Some Caveats and Some Examples

A thesis is never a question. Readers of academic essays expect to have questions discussed, explored, or even answered. A question ("Why did communism collapse in Eastern Europe?") is not an argument, and without an argument, a thesis is dead in the water.

A thesis is never a list. "For political, economic, social and cultural reasons, communism collapsed in Eastern Europe" does a good job of "telegraphing" the reader what to expect in the essay—a section about political reasons, a section about economic reasons, a section about social reasons, and a section about cultural reasons. However, political, economic, social and cultural reasons are pretty much the only possible reasons why communism could collapse. This sentence lacks tension and doesn't advance an argument. Everyone knows that politics, economics, and culture are important.

A thesis should never be vague, combative or confrontational. An ineffective thesis would be, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because communism is evil." This is hard to argue (evil from whose perspective? what does evil mean?) and it is likely to mark you as moralistic and judgmental rather than rational and thorough. It also may spark a defensive reaction from readers sympathetic to communism. If readers strongly disagree with you right off the bat, they may stop reading.

An effective thesis has a definable, arguable claim. "While cultural forces contributed to the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, the disintegration of economies played the key role in driving its decline" is an effective thesis sentence that "telegraphs," so that the reader expects the essay to have a section about cultural forces and another about the disintegration of economies. This thesis makes a definite, arguable claim: that the disintegration of economies played a more important role than cultural forces in defeating communism in Eastern Europe. The reader would react to this statement by thinking, "Perhaps what the author says is true, but I am not convinced. I want to read further to see how the author argues this claim."

A thesis should be as clear and specific as possible. Avoid overused, general terms and abstractions. For example, "Communism collapsed in Eastern Europe because of the ruling elite's inability to address the economic concerns of the people" is more powerful than "Communism collapsed due to societal discontent."

Copyright 1999, Maxine Rodburg and The Tutors of the Writing Center at Harvard University

How To Write 3 Types Of Thesis Statements

A thesis statement is “a short summary of the main idea, purpose, or argument of an essay that usually appears in the first paragraph.” It’s generally only one or two sentences in length.

A strong thesis statement is the backbone of a well-organized paper, and helps you decide what information is most important to include and how it should be presented.

What is a good thesis statement?

This thesis statement, for example, could open a paper on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s importance as a civil rights leader: “Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was one of the most influential figures of the American civil rights movement. His moving speeches and nonviolent protests helped unite a nation divided by race.”

This example lays out the writer’s basic argument (King was an important leader of the American civil rights movement), offers two areas of evidence (his speeches and nonviolent protests), and explains why the argument matters (united a divided nation).

A good thesis statement delivers a clear message about the scope of the topic and the writer’s approach to the subject. In contrast, poor thesis statements fail to take a position, are based solely on personal opinion, or state an obvious truth. For example, “Democracy is a form of government,” is a weak thesis statement because it’s too general, doesn’t adopt a stance, and states a well-known fact that doesn’t need further explanation.

What are the different types of thesis statements?

Thesis statements can be explanatory , argumentative , or analytical . The type of paper determines the form of the thesis statement.

1. Explanatory thesis statement

An explanatory thesis statement is based solely on factual information. It doesn’t contain personal opinions or make claims that are unsupported by evidence. Instead, it tells the reader precisely what the topic will be and touches on the major points that will be explored in the essay. An explanatory thesis statement is sometimes also called an expository thesis statement .

For example: The core components of a healthy lifestyle include a nutritious diet, regular exercise, and adequate sleep.

2. Argumentative thesis statement

In an argumentative essay, the writer takes a stance on a debatable topic. This stance, and the claims to back it up, is the argument . Unlike an explanatory thesis statement, an argumentative thesis statement allows the writer to take a position about a subject (e.g., the deeper meaning of a literary text, the best policy towards a social problem) and to convince readers of their stance. The body of the argumentative essay uses examples and other evidence to support the writer’s opinion.

For example: Shakespeares’s Taming of the Shrew uses humor, disguise, and social roles to criticize the lack of power women had in Elizabethan England.

3. Analytical thesis statement

An analytical thesis statement analyzes, or breaks down, an issue or idea into its different parts. Then, it evaluates the topic and clearly presents the order of the analysis to the reader.

For example: The school’s policy to start its school day an hour later revealed three related benefits: students were more alert and attentive in class, had a more positive about school, and performed better in their coursework.

How to write a thesis statement

Writing a thesis statement requires time and careful thought. The thesis statement should flow naturally from research and set out the writer’s discoveries. When composing a thesis statement, make sure it focuses on one main idea that can be reasonably covered within your desired page length. Try not to write about the entire history of America, for example, in a three-page paper.

Although deciding upon a thesis statement can be challenging and time-consuming, a strong thesis statement can make the paper both easier to write and more enjoyable to read. Don’t worry: we’re not going to leave you hanging! We’ve got a whole article to help you write an effective thesis statement here .

Ways To Say

Synonym of the day

ENGL001: English Composition I

Research writing and argument.

When we write at the college level, we consider more than just the method of writing. The method includes our grammar, punctuation, and vocabulary. Writing in college is rhetorical, which means we consider how the reader will interpret your text. Who will read what you write? Why will he or she read it? What do you hope they gain from reading it? How do you present it to them? All of these elements work together to make up what we call "the rhetorical situation".

Specifically, the rhetorical situation asks you to consider your context. To do this, think about who you are writing for (your audience) and why you are writing to them (your purpose).

All Writing is Argumentative

This chapter is about rhetoric – the art of persuasion. Every time we write, we engage in argument. Through writing, we try to persuade and influence our readers, either directly or indirectly. We work to get them to change their minds, to do something, or to begin thinking in new ways. Therefore, every writer needs to know and be able to use principles of rhetoric. The first step towards such knowledge is learning to see the argumentative nature of all writing.

I have two goals in this chapter: to explain the term rhetoric and to give you some historical perspective on its origins and development; and to demonstrate the importance of seeing research writing as a rhetorical, persuasive activity. As consumers of written texts, we are often tempted to divide writing into two categories: argumentative and non-argumentative. According to this view, in order to be argumentative, writing must have the following qualities. It has to defend a position in a debate between two or more opposing sides; it must be on a controversial topic; and the goal of such writing must be to prove the correctness of one point of view over another.

On the other hand, this view goes, non-argumentative texts include narratives, descriptions, technical reports, news stories, and so on. When deciding to which category a given piece of writing belongs, we sometimes look for familiar traits of argument, such as the presence of a thesis statement, of "factual" evidence, and so on.

Research writing is often categorized as non-argumentative. This happens because of the way in which we learn about research writing. Most of us do that through the traditional research report, the kind which focuses too much on information-gathering and note cards and not enough on constructing engaging and interesting points of view for real audiences. It is the gathering and compiling of information, and not doing something productive and interesting with this information, that become the primary goals of this writing exercise. Generic research papers are also often evaluated on the quantity and accuracy of external information that they gather, rather on the persuasive impact they make and the interest they generate among readers.

Having written countless research reports, we begin to suspect that all research-based writing is non-argumentative. Even when explicitly asked to construct a thesis statement and support it through researched evidence, beginning writers are likely to pay more attention to such mechanics of research as finding the assigned number and kind of sources and documenting them correctly, than to constructing an argument capable of making an impact on the reader.

Arguments Are Not Verbal Fights

We often have narrow concept of the word argument. In everyday life, argument often implies a confrontation, a clash of opinions and personalities, or just a plain verbal fight. It implies a winner and a loser, a right side and a wrong one. Because of this understanding of the word argument, the only kind of writing seen as argumentative is the debate-like position paper, in which the author defends his or her point of view against other, usually opposing points of view.

Such an understanding of argument is narrow because arguments come in all shapes and sizes. I invite you to look at the term argument in a new way. What if we think of argument as an opportunity for conversation, for sharing with others our point of view on something, for showing others our perspective of the world? What if we see it as the opportunity to tell our stories, including our life stories? What if we think of "argument" as an opportunity to connect with the points of view of others rather than defeating those points of view?

Some years ago, I heard a conference speaker define argument as the opposite of "beating your audience into rhetorical submission". I still like that definition because it implies gradual and even gentle explanation and persuasion instead of coercion. It implies effective use of details, and stories, including emotional ones. It implies the understanding of argument as an explanation of one's world view.

Arguments then, can be explicit and implicit, or implied. Explicit arguments contain noticeable and definable thesis statements and lots of specific proofs. Implicit arguments, on the other hand, work by weaving together facts and narratives, logic and emotion, personal experiences and statistics. Unlike explicit arguments, implicit ones do not have a one-sentence thesis statement. Instead, authors of implicit arguments use evidence of many different kinds in effective and creative ways to build and convey their point of view to their audience. Research is essential for creative effective arguments of both kinds.

Definitions of Rhetoric and the Rhetorical Situation

The art of creating effective arguments is explained and systematized by a discipline called rhetoric. Writing is about making choices, and knowing the principles of rhetoric allows a writer to make informed choices about various aspects of the writing process. Every act of writing takes places in a specific rhetorical situation. The three most basic and important components of a rhetorical situations are:

- Purpose of writing

- Intended audience,

- Occasion, or context in which the text will be written and read

These factors help writers select their topics, arrange their material, and make other important decisions about their work.

Before looking closely at different definitions and components of rhetoric, let us try to understand what rhetoric is not. In recent years, the word "rhetoric" has developed a bad reputation in American popular culture. In the popular mind, the term "rhetoric" has come to mean something negative and deceptive. Open a newspaper or turn on the television, and you are likely to hear politicians accusing each other of "too much rhetoric and not enough substance". According to this distorted view, rhetoric is verbal fluff, used to disguise empty or even deceitful arguments.

Examples of this misuse abound. Here are some examples.

A 2013 Washington Post article, "GOP Tries Pushing Back against 'War on Women' Rhetoric", by Nia-Malika Henderson describes a comment made by former Republican presidential candidate and Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee during the Republican National Committee annual winter meeting. Huckabee suggested that some women "believe that they are helpless without Uncle Sugar coming in and providing for them a prescription each month for birth control because they cannot control their libido or their reproductive system without the help of the government". Some Democrats pointed to Huckabee's statement as proof that the Republican party was waging a "war on women". However, in the article, Chelsi Henry, a Republican woman stated, "What war on women? That is just political rhetoric". The word "rhetoric" in this context implies a strategy to deceive or distract.

Another example is the title of the now-defunct political website, Spinsanity: Countering Rhetoric with Reason. The website's authors state that "engaged citizenry, active press and strong network of fact-checking websites and blogs can help turn the tide of deception that we now see". What this statement implies, of course, is that rhetoric is "spin" and that it is the opposite of truth. Here, perhaps, is the most interesting example. The author of the video below, posted on Youtube, is clearly dissatisfied with the abundance of "rhetoric" in Barack Obama's 2008 campaign for the White House.

What is interesting about this clip is that its author does not seem to realize that she is engaging in rhetoric as she is criticizing the term. She has a purpose, which is to question Obama's credentials; she is addressing an audience which consists of people who are perhaps considering voting for Obama; finally, she is creating her video in a very real context of the heated battle between Senators Obama and Clinton for the Presidential nomination of the Democratic Party.

Rhetoric is not a dirty trick used by politicians to conceal and obscure, but an art, which, for many centuries, has had many definitions. Perhaps the most popular and overreaching definition comes to us from the Ancient Greek thinker Aristotle. Aristotle defined rhetoric as "the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion" (Ch.2). Aristotle saw primarily as a practical tool, indispensable for civic discourse.

Elements of the Rhetorical Situation

When composing, every writer must take into account the conditions under which the writing is produced and will be read. It is customary to represent the three key elements of the rhetorical situation as a triangle of writer, reader, and text, or, as they are represented on this image, as communicator , audience , and message .

Figure 1.1. Source: St. Edward's University

The three elements of the rhetorical situation are in a constant and dynamic interrelation. All three are also necessary for communication through writing to take place. For example, if the writer is taken out of this equation, the text will not be created. Similarly, eliminating the text itself will leave us with the reader and writer, but without any means of conveying ideas between them, and so on.

Moreover, changing on or more characteristics of any of the elements depicted in the figure above will change the other elements as well. For example, with the change in the beliefs and values of the audience, the message will also likely change to accommodate those new beliefs, and so on.

In his discussion of rhetoric, Aristotle states that writing's primary purpose is persuasion. Other ancient rhetoricians' theories expand the scope of rhetoric by adding new definitions, purposes, and methods. For example, another Greek philosopher and rhetorician Plato saw rhetoric as a means of discovering the truth, including personal truth, through dialog and discussion. According to Plato, rhetoric can be directed outward (at readers or listeners), or inward (at the writer him or herself). In the latter case, the purpose of rhetoric is to help the author discover something important about his or her own experience and life. The third major rhetorical school of Ancient Greece whose views have profoundly influenced our understanding of rhetoric were the Sophists. The Sophists were teachers of rhetoric for hire. The primary goal of their activities was to teach skills and strategies for effective speaking and writing. Many Sophists claimed that they could make anyone into an effective rhetorician. In their most extreme variety, Sophistic rhetoric claims that virtually anything could be proven if the rhetorician has the right skills. The legacy of Sophistic rhetoric is controversial. Some scholars, including Plato himself, have accused the Sophists of bending ethical standards in order to achieve their goals, while others have praised them for promoting democracy and civic participation through argumentative discourse. What do these various definitions of rhetoric have to do with research writing? Everything!

If you have ever had trouble with a writing assignment, chances are it was because you could not figure out the assignment's purpose. Or, perhaps you did not understand very well whom your writing was supposed to appeal to. It is hard to commit to purposeless writing done for no one in particular.

Research is not a very useful activity if it is done for its own sake. If you think of a situation in your own life where you had to do any kind of research, you probably had a purpose that the research helped you to accomplish. You could, for example, have been considering buying a car and wanted to know which make and model would suite you best. Or, you could have been looking for an apartment to rent and wanted to get the best deal for your money. Or, perhaps your family was planning a vacation and researched the best deals on hotels, airfares, and rental cars. Even in these simple examples of research that are far simpler than research most writers conduct, you as a researcher were guided by some overriding purpose. You researched because you had a purpose to accomplish.

How to Approach Writing Tasks Rhetorically

The three main elements of rhetorical theory are purpose, audience, and occasion. We will look at these elements primarily through the lens of Classical Rhetoric, the rhetoric of Ancient Greece and Rome. Principles of classical rhetoric (albeit some of them modified) are widely accepted across the modern Western civilization. Classical rhetoric provides a solid framework for analysis and production of effective texts in a variety of situations.

Good writing always serves a purpose. Texts are created to persuade, entertain, inform, instruct, and so on. In a real writing situation, these discrete purposes are often combined

The second key element of the rhetorical approach to writing is audience-awareness. As you saw from the rhetorical triangle earlier in this chapter, readers are an indispensable part of the rhetorical equation, and it is essential for every writer to understand their audience and tailor his or her message to the audience's needs. The key principles that every writer needs to follow in order to reach and affect his or her audience are as follows:

- Have a clear idea about who your readers will be.

- Understand your readers' previous experiences, knowledge, biases, and expectations and how these factors can influence their reception of your argument.

- When writing, keep in mind not only those readers who are physically present or whom you know (your classmates and instructor), but all readers who would benefit from or be influenced by your argument.

- Choose a style, tone, and medium of presentation appropriate for your intended audience.

Occasion is an important part of the rhetorical situation. It is a part of the writing context that was mentioned earlier in the chapter. Writers do not work in a vacuum. Instead, the content, form and reception of their work by readers are heavily influenced by the conditions in society as well as by personal situations of their readers. These conditions in which texts are created and read affect every aspect of writing and every stage of the writing process, from topic selection, to decisions about what kinds of arguments used and their arrangement, to the writing style, voice, and persona which the writer wishes to project in his or her writing.

All elements of the rhetorical situation work together in a dynamic relationship. Therefore, awareness of rhetorical occasion and other elements of the context of your writing will also help you refine your purpose and understand your audience better. Similarly having a clear purpose in mind when writing and knowing your audience will help you understand the context in which you are writing and in which your work will be read better.

One aspect of writing where you can immediately benefit from understanding occasion and using it to your rhetorical advantage is the selection of topics for your compositions. Any topic can be good or bad, and a key factor in deciding on whether it fits the occasion. In order to understand whether a particular topic is suitable for a composition, it is useful to analyze whether the composition would address an issue, or a rhetorical exigency when created. The writing activity below can help you select topics and issues for written arguments.

To understand how writers can study and use occasion in order to make effective arguments, let us examine another ancient rhetorical concept. Kairos is one of the most fascinating terms from Classical rhetoric. It signifies the right, or opportune moment for an argument to be made. It is such a moment or time when the subject of the argument is particularly urgent or important and when audiences are more likely to be persuaded by it. Ancient rhetoricians believed that if the moment for the argument is right, for instance if there are conditions in society which would make the audience more receptive to the argument, the rhetorician would have more success persuading such an audience.

Figure 1.2. Kairos. Source: Ancient Greek Cities

For example, as I write this text, a heated debate about the war on terrorism and about the goals and methods of this war is going on in the US. It is also the year of the Presidential Election, and political candidates try to use the war on terrorism to their advantage when they debate each other. These are topics of high public interest, with print media, television, radio, and the Internet constantly discussing them. Because there is an enormous public interest in the topic of terrorism, well-written articles and reports on the subject will not fall on deaf ears. Simply put, the moment, or occasion, for the debate is right, and it will continue until public interest in the subject weakens or disappears.

Rhetorical Appeals

In order to persuade their readers, writers must use three types of proofs or rhetorical appeals. They are logos , or logical appeal; pathos , or emotional appeal; and ethos , or ethical appeal, or appeal based on the character and credibility of the author. It is easy to notice that modern words logical , pathetic , and ethical are derived from those Greek words. In his work Rhetoric, Aristotle writes that the three appeals must be used together in every piece of persuasive discourse. An argument based on the appeal to logic, or emotions alone will not be an effective one. Understanding how logos , pathos , and ethos should work together is important for writers who use research. Often, research writing assignments are written in a way that seems to emphasize logical proofs over emotional or ethical ones. Such logical proofs in research papers typically consist of factual information, statistics, examples, and other similar evidence. According to this view, writers of academic papers need to be unbiased and objective, and using logical proofs will help them to be that way. Because of this emphasis on logical proofs, you may be less familiar with the kinds of pathetic and ethical proofs available to you. Pathetic appeals, or appeals to emotions of the audience were considered by ancient rhetoricians as important as logical proofs. Yet, writers are sometimes not easily convinced to use pathetic appeals in their writing. As modern rhetoricians and authors of the influential book Classical Rhetoric for the Modern Student (1998), Edward P.J. Corbett and Robert Connors said, "People are rather sheepish about acknowledging that their opinions can be affected by their emotions" (86).

According to Corbett, many of us think that there may be something wrong about using emotions in argument. But, I agree with Corbett and Connors, pathetic proofs are not only admissible in argument, but necessary (86-89). The most basic way of evoking appropriate emotional responses in your audience, according to Corbett, is the use of vivid descriptions (94). Using ethical appeals, or appeals based on the character of the writer, involves establishing and maintaining your credibility in the eyes of your readers. In other words, when writing, think about how you are presenting yourself to your audience. Do you give your readers enough reasons to trust you and your argument, or do you give them reasons to doubt your authority and your credibility? Consider all the times when your decision about the merits of a given argument was affected by the person or people making the argument. For example, when watching television news, are you predisposed against certain cable networks and more inclined towards others because you trust them more? So, how can a writer establish a credible persona for his or her audience? One way to do that is through external research. Conducting research and using it well in your writing help with you with the factual proofs ( logos ), but it also shows your readers that you, as the author, have done your homework and know what you are talking about. This knowledge, the sense of your authority that this creates among your readers, will help you be a more effective writer. The logical, pathetic, and ethical appeals work in a dynamic combination with one another. It is sometimes hard to separate one kind of proof from another and the methods by which the writer achieved the desired rhetorical effect. If your research contains data which is likely to cause your readers to be emotional, it data can enhance the pathetic aspect of your argument. The key to using the three appeals, is to use them in combination with each other, and in moderation. It is impossible to construct a successful argument by relying too much on one or two appeals while neglecting the others. Consider two recent examples of fairly ineffective use of the three appeals. In the beginning of April 2008, two candidates for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination, Senators Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama began airing campaign television ads in Pennsylvania ahead of their party's primary presidential election in that state. You can see both ads below.

Clinton's ad is called "Scranton" and it is heavy on pathos , or emotional appeal. It invokes very warm childhood memories which, the ad's creators hoped, would show Senator Clinton's "softer side" thus persuading more people to vote for her. The purpose of the ad is to stir emotion, and it does it rather well. The problem with this approach is, however, that it does not tell voters much about the concrete steps and activities Senator Clinton would undertake if elected. The ad is rather thin on the logical appeal, and this, in turn, affects Clinton's ethos or credibility.

Barack Obama's ad is called "One Voice", and is calling on his supporters to "change the world".

While this is certainly a worthy cause, it is not clear from this ad how exactly Obama – still a senator at the time – intended to change the world once elected. The reason for this lack of clarity is the heavy emphasis on the pathetic appeal at the expense of logos . If you followed the presidential campaign of 2008, you would know that the call for change which is so clear in this ad was Obama's main slogan, a statement that became a large part of his ethos , or persona as a politician and as a rhetorician. This ad succeeds in highlighting that part of Obama's political persona once again while, probably intentionally, under-emphasizing logos .

Research Writing as Conversation

Writing is a social process. Texts are created to be read by others, and in creating those texts, writers should be aware of not only their personal assumptions, biases, and tastes, but also those of their readers. Writing, therefore, is an interactive process. It is a conversation, a meeting of minds, during which ideas are exchanged, debates and discussions take place and, sometimes, but not always, consensus is reached. You may be familiar with the famous quote by the 20th century rhetorician Kenneth Burke who compared writing to a conversation at a social event. In his 1974 book "The Philosophy of Literary Form", Burke writes,

Imagine that you enter a parlor. You come late. When you arrive, others have long preceded you, and they are engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to pause and tell you exactly what it is about. In fact, the discussion had already begun long before any of them got there, so that no one present is qualified to retrace for you all the steps that had gone before. You listen for a while, until you decide that you have caught the tenor of the argument; then you put in your oar. Someone answers; you answer him, another comes to your defense; another aligns himself against you, to either the embarrassment of gratification of your opponent, depending upon the quality of your ally's assistance. However, the discussion is interminable. The hour grows late, you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in progress (110-111).

This passage by Burke is extremely popular among writers because it captures the interactive nature of writing so precisely. Reading Burke's words carefully, we will notice that the interaction between readers and writers is continuous. A writer always enters a conversation in progress. In order to participate in the discussion, just like in real life, you need to know what your interlocutors have been talking about. So you listen (read). Once you feel you have got the drift of the conversation, you say (write) something. Your text is read by others who respond to your ideas, stories, and arguments with their own. This interaction never ends! To write well, it is important to listen carefully and understand the conversations that are going on around you. Writers who are able to listen to these conversations and pick up important topics, themes, and arguments are generally more effective at reaching and impressing their audiences. It is also important to treat research, writing, and every occasion for these activities as opportunities to participate in the on-going conversation of people interested in the same topics and questions which interest you. Our knowledge about our world is shaped by the best and most up-to-date theories available to them. Sometimes these theories can be experimentally tested and proven, and sometimes, when obtaining such proof is impossible, they are based on consensus reached as a result of conversation and debate. Even the theories and knowledge that can be experimentally tested (for example in sciences) do not become accepted knowledge until most members of the scientific community accept them. Other members of this community will help them test their theories and hypotheses, give them feedback on their writing, and keep them searching for the best answers to their questions. As Burke says in his famous passage, the interaction between the members of intellectual communities never ends. No piece of writing, no argument, no theory or discover is ever final. Instead, they all are subject to discussion, questioning, and improvement. A simple but useful example of this process is the evolution of humankind's understanding of their planet Earth and its place in the Universe. As you know, in Medieval Europe, the prevailing theory was that the Earth was the center of the Universe and that all other planets and the Sun rotated around it. This theory was the result of the church's teachings, and thinkers who disagreed with it were pronounced heretics and often burned. In 1543, astronomer Nikolaus Copernicus argued that the Sun was at the center of the solar system and that all planets of the system rotate around the Sun. Later, Galileo experimentally proved Copernicus' theory with the help of a telescope. Of course, the Earth did not begin to rotate around the Sun with this discovery. Yet, Copernicus' and Galileo's theories of the Universe went against the Catholic Church's teachings which dominated the social discourse of Medieval Europe. The Inquisition did not engage in debate with the two scientists. Instead, Copernicus was executed for his views and Galileo was sentenced to house arrest for his views. Although in the modern world, dissenting thinkers are unlikely to suffer such harsh punishment, the examples of Copernicus and Galileo teach us two valuable lessons about the social nature of knowledge. Firstly, Both Copernicus and Galileo tried to improve on an existing theory of the Universe that placed our planet at the center. They did not work from nothing but used beliefs that already existed in their society and tried to modify and disprove those beliefs. Time and later scientific research proved that they were right. Secondly, even after Galileo was able to prove the structure of the Solar system experimentally, his theory did not become widely accepted until the majority of people in society assimilated it. Therefore, new findings do not become accepted knowledge until they penetrate the fabric of social discourse and until enough people accept them as true.

Conclusions

In this chapter, we have learned the definition of rhetoric and the basic differences between several important rhetorical schools. We have also discussed how to key elements of the rhetorical situation: purpose, audience, and context. As you work on the research writing projects presented throughout this book, be sure to revisit this chapter often.

Everything that you have read about here and every activity you have completed as you worked through this chapter is applicable to all research writing projects in this book and beyond. Most school writing assignments give you direct instructions about your purpose, intended audience, and rhetorical occasion. Truly proficient and independent writers, however, learn to define their purpose, audiences, and contexts of their writing, on their own. The material in this chapter is designed to enable to become better at those tasks. When you receive a writing assignment, it is tempting to see it as just another hoop to jump through and not as a genuine rhetorical situation, an opportunity to influence others with your writing. It is certainly tempting to see yourself writing only for the teacher, without a real purpose and oblivious of the context of your writing. The material of this chapter as well as the writing projects presented throughout this book are designed to help you think of writing as a persuasive, rhetorical activity. Conducting research and incorporating its results into your paper is a part of this rhetorical process.

Works Cited

Aristotle. "Rhetoric". Aristotle's Rhetoric. June 21, 2004. April 21, 2008. Burke, Kenneth. The Philosophy of Literary Form. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1941. Clinton, Hillary. "Scranton". Youtube. April 7, 2008. April 21, 2008. Corbett, Edward, P.J and Connors, Robert. Classical Rhetoric for the Modern Student. Oxford University Press, USA; Fourth edition, 1998. Fritz, Ben et al. "About Spinsanity". Spinsanity. 2001-2005. April 21, 2008.

Henderson, Nia-Malika. "GOP tries pushing back against 'war on women' rhetoric". Washington Post . Washington Post, 24 Jan 2014. Web. 27 Jan. 2014.

Obama, Barack. "One Voice". Youtube. April 8, 2008. April 21, 2008. Papakyriakou/Anagnostou, Ellen. Kairos. Ancient Greek Cities. 1998. April 21, 2008. MBROWDE. "The Rhetorical Triangle". Image. Rhetoric in the 21st Century: The Changing Language of Digital Spaces . St. Edward's University, 11 Feb 2013. Web. 27 Jan 2014. wafer157. "Obama Rhetoric". Youtube. February 27, 2008. April 21, 2008.

Home / Guides / Writing Guides / Parts of a Paper / How to Write a Strong Thesis Statement

How to Write a Strong Thesis Statement

A thesis can be found in many places—a debate speech, a lawyer’s closing argument, even an advertisement. But the most common place for a thesis statement (and probably why you’re reading this article) is in an essay.

Whether you’re writing an argumentative paper, an informative essay, or a compare/contrast statement, you need a thesis. Without a thesis, your argument falls flat and your information is unfocused. Since a thesis is so important, it’s probably a good idea to look at some tips on how to put together a strong one.

Guide Overview

What is a “thesis statement” anyway.

- 2 categories of thesis statements: informative and persuasive

- 2 styles of thesis statements

- Formula for a strong argumentative thesis

- The qualities of a solid thesis statement (video)

You may have heard of something called a “thesis.” It’s what seniors commonly refer to as their final paper before graduation. That’s not what we’re talking about here. That type of thesis is a long, well-written paper that takes years to piece together.

Instead, we’re talking about a single sentence that ties together the main idea of any argument . In the context of student essays, it’s a statement that summarizes your topic and declares your position on it. This sentence can tell a reader whether your essay is something they want to read.

2 Categories of Thesis Statements: Informative and Persuasive

Just as there are different types of essays, there are different types of thesis statements. The thesis should match the essay.

For example, with an informative essay, you should compose an informative thesis (rather than argumentative). You want to declare your intentions in this essay and guide the reader to the conclusion that you reach.

To make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, you must procure the ingredients, find a knife, and spread the condiments.

This thesis showed the reader the topic (a type of sandwich) and the direction the essay will take (describing how the sandwich is made).

Most other types of essays, whether compare/contrast, argumentative, or narrative, have thesis statements that take a position and argue it. In other words, unless your purpose is simply to inform, your thesis is considered persuasive. A persuasive thesis usually contains an opinion and the reason why your opinion is true.

Peanut butter and jelly sandwiches are the best type of sandwich because they are versatile, easy to make, and taste good.

In this persuasive thesis statement, you see that I state my opinion (the best type of sandwich), which means I have chosen a stance. Next, I explain that my opinion is correct with several key reasons. This persuasive type of thesis can be used in any essay that contains the writer’s opinion, including, as I mentioned above, compare/contrast essays, narrative essays, and so on.

2 Styles of Thesis Statements

Just as there are two different types of thesis statements (informative and persuasive), there are two basic styles you can use.

The first style uses a list of two or more points . This style of thesis is perfect for a brief essay that contains only two or three body paragraphs. This basic five-paragraph essay is typical of middle and high school assignments.

C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia series is one of the richest works of the 20th century because it offers an escape from reality, teaches readers to have faith even when they don’t understand, and contains a host of vibrant characters.

In the above persuasive thesis, you can see my opinion about Narnia followed by three clear reasons. This thesis is perfect for setting up a tidy five-paragraph essay.

In college, five paragraph essays become few and far between as essay length gets longer. Can you imagine having only five paragraphs in a six-page paper? For a longer essay, you need a thesis statement that is more versatile. Instead of listing two or three distinct points, a thesis can list one overarching point that all body paragraphs tie into.

Good vs. evil is the main theme of Lewis’s Narnia series, as is made clear through the struggles the main characters face in each book.

In this thesis, I have made a claim about the theme in Narnia followed by my reasoning. The broader scope of this thesis allows me to write about each of the series’ seven novels. I am no longer limited in how many body paragraphs I can logically use.

Formula for a Strong Argumentative Thesis

One thing I find that is helpful for students is having a clear template. While students rarely end up with a thesis that follows this exact wording, the following template creates a good starting point:

___________ is true because of ___________, ___________, and ___________.

Conversely, the formula for a thesis with only one point might follow this template:

___________________ is true because of _____________________.

Students usually end up using different terminology than simply “because,” but having a template is always helpful to get the creative juices flowing.

The Qualities of a Solid Thesis Statement

When composing a thesis, you must consider not only the format, but other qualities like length, position in the essay, and how strong the argument is.

Length: A thesis statement can be short or long, depending on how many points it mentions. Typically, however, it is only one concise sentence. It does contain at least two clauses, usually an independent clause (the opinion) and a dependent clause (the reasons). You probably should aim for a single sentence that is at least two lines, or about 30 to 40 words long.

Position: A thesis statement always belongs at the beginning of an essay. This is because it is a sentence that tells the reader what the writer is going to discuss. Teachers will have different preferences for the precise location of the thesis, but a good rule of thumb is in the introduction paragraph, within the last two or three sentences.

Strength: Finally, for a persuasive thesis to be strong, it needs to be arguable. This means that the statement is not obvious, and it is not something that everyone agrees is true.

Example of weak thesis:

Peanut butter and jelly sandwiches are easy to make because it just takes three ingredients.

Most people would agree that PB&J is one of the easiest sandwiches in the American lunch repertoire.

Example of a stronger thesis:

Peanut butter and jelly sandwiches are fun to eat because they always slide around.

This is more arguable because there are plenty of folks who might think a PB&J is messy or slimy rather than fun.

Composing a thesis statement does take a bit more thought than many other parts of an essay. However, because a thesis statement can contain an entire argument in just a few words, it is worth taking the extra time to compose this sentence. It can direct your research and your argument so that your essay is tight, focused, and makes readers think.

EasyBib Writing Resources

Writing a paper.

- Academic Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- College Admissions Essay

- Expository Essay

- Persuasive Essay

- Research Paper

- Thesis Statement

- Writing a Conclusion

- Writing an Introduction

- Writing an Outline

- Writing a Summary

EasyBib Plus Features

- Citation Generator

- Essay Checker

- Expert Check Proofreader

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tools

Plagiarism Checker

- Spell Checker

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Grammar and Plagiarism Checkers

Grammar Basics

Plagiarism Basics

Writing Basics

Upload a paper to check for plagiarism against billions of sources and get advanced writing suggestions for clarity and style.

Get Started

Thesis Statements: Crafting a Claim Backed by Reasoning

Overview of thesis statements.

A clear and well-developed thesis statement is, in many cases, the backbone of most essays and research papers. The thesis statement presents your argument to your reader, making your stance or your position clear. A solid thesis statement can also provide structure for your writing. Even in non-argumentative writing, such as narrative essays, you can still use your thesis statement to express your purpose for writing.

In your thesis statement, you can provide the overarching claims you plan to make, as well as your reasoning for those claims. You can think of the thesis statement as being made up of two parts: the position and the reasoning. The position is the overall point you are making, and the reasoning is the explanation or logic behind that position. When you include both the position and the reasoning, your thesis statement shows your readers how you intend to structure your writing. For more on organization in your writing, see the Stone Writing Center (SWC) handout on this topic.

Argumentative Thesis Statements

When it comes to argumentative thesis statements, these statements are not argumentative for the sake of conflict; rather, you are writing to inform and persuade your readers, advancing their understanding of your topic. It might be helpful to even think of argumentative thesis statements like a road map that guides your writing as a whole. For more on argumentative writing, see the SWC handouts on this topic.

An argumentative thesis statement makes a clear assertion, taking a stance and providing details to support that stance. An effective argumentative thesis statement helps to persuade the reader by providing an outline of the main claims and reasoning for those claims.

Examples of Thesis Statements

Each of these sample thesis statements takes a stance on a subject and states a claim, then provides supporting details to convey the reasoning for the claim/s. The position or claim is in bold , and the reasoning is in italics .

Adults should eat apples more regularly because the fruit has many health benefits including lowering risk for heart disease, improving digestion, and promoting weight loss.

The Stone Writing Center is a convenient learning resource for Del Mar College as it provides a place where students can get help with their writing and offers multiple services for all writers.

Because of the convenience, low prices, and diverse options , people should get rid of cable and join streaming services instead.

Del Mar College is a great option to further one’s education because it offers many different academic programs, has a lower cost than surrounding universities, and provides dual-enrollment courses for high school students.

Because public libraries give citizens access to free books, technological resources, and other helpful learning programs, these institutions deserve more city funding.

To demonstrate the theme that family can be made through friends, The Avengers* movie uses characterization, conflict, and allusion. *Note: Movie titles, such as The Avengers , are usually italicized.

By providing readers with the main claim or position, as well as the reasoning or explanations for said claim, thesis statements allow you to effectively communicate the overall argument you intend to make in your writing.

Page last updated July 12, 2023.

Edit Site Title and Tagline from Dashboard > Appearance > Customize > Site Identity

Expository Thesis Statements vs. Argumentative Thesis Statements

Fleming, Grace. “How to Write a Solid Thesis Statement.” ThoughtCo, Feb. 11, 2020, thoughtco.com/thesis-statement-examples-and-instruction-1857566.

A thesis statement provides the foundation for your entire research paper or essay. This statement is the central assertion that you want to express in your essay. A successful thesis statement is one that is made up of one or two sentences clearly laying out your central idea and expressing an informed, reasoned answer to your research question.

Usually, the thesis statement will appear at the end of the first paragraph of your paper. There are a few different types, and the content of your thesis statement will depend upon the type of paper you’re writing.

Key Takeaways: Writing a Thesis Statement

- A thesis statement gives your reader a preview of your paper’s content by laying out your central idea and expressing an informed, reasoned answer to your research question.

- Thesis statements will vary depending on the type of paper you are writing, such as an expository essay, argument paper, or analytical essay.

- Before creating a thesis statement, determine whether you are defending a stance, giving an overview of an event, object, or process, or analyzing your subject

Expository Essay Thesis Statement Examples

An expository essay “exposes” the reader to a new topic; it informs the reader with details, descriptions, or explanations of a subject. If you are writing an expository essay , your thesis statement should explain to the reader what she will learn in your essay. For example:

- The United States spends more money on its military budget than all the industrialized nations combined.

- Gun-related homicides and suicides are increasing after years of decline.

- Hate crimes have increased three years in a row, according to the FBI.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) increases the risk of stroke and arterial fibrillation (irregular heartbeat).

These statements provide a statement of fact about the topic (not just opinion) but leave the door open for you to elaborate with plenty of details. In an expository essay, you don’t need to develop an argument or prove anything; you only need to understand your topic and present it in a logical manner. A good thesis statement in an expository essay always leaves the reader wanting more details.

Types of Thesis Statements

Before creating a thesis statement, it’s important to ask a few basic questions, which will help you determine the kind of essay or paper you plan to create:

- Are you defending a stance in a controversial essay ?

- Are you simply giving an overview or describing an event, object, or process?

- Are you conducting an analysis of an event, object, or process?

In every thesis statement , you will give the reader a preview of your paper’s content, but the message will differ a little depending on the essay type .

Argument Thesis Statement Examples

If you have been instructed to take a stance on one side of a controversial issue, you will need to write an argument essay . Your thesis statement should express the stance you are taking and may give the reader a preview or a hint of your evidence. The thesis of an argument essay could look something like the following:

- Self-driving cars are too dangerous and should be banned from the roadways.

- The exploration of outer space is a waste of money; instead, funds should go toward solving issues on Earth, such as poverty, hunger, global warming, and traffic congestion.

- The U.S. must crack down on illegal immigration.

- Street cameras and street-view maps have led to a total loss of privacy in the United States and elsewhere.

These thesis statements are effective because they offer opinions that can be supported by evidence. If you are writing an argument essay, you can craft your own thesis around the structure of the statements above.

Analytical Essay Thesis Statement Examples

In an analytical essay assignment, you will be expected to break down a topic, process, or object in order to observe and analyze your subject piece by piece. Examples of a thesis statement for an analytical essay include:

- The criminal justice reform bill passed by the U.S. Senate in late 2018 (“ The First Step Act “) aims to reduce prison sentences that disproportionately fall on nonwhite criminal defendants.

- The rise in populism and nationalism in the U.S. and European democracies has coincided with the decline of moderate and centrist parties that have dominated since WWII.

- Later-start school days increase student success for a variety of reasons.

Because the role of the thesis statement is to state the central message of your entire paper, it is important to revisit (and maybe rewrite) your thesis statement after the paper is written. In fact, it is quite normal for your message to change as you construct your paper.

*********************************************************************

This video covers: • Review of Expository Essays and Elements • What a Thesis is • Important parts of a Thesis • Tips for writing a quality thesis

Need help with the Commons?

Email us at [email protected] so we can respond to your questions and requests. Please email from your CUNY email address if possible. Or visit our help site for more information:

- Terms of Service

- Accessibility

- Creative Commons (CC) license unless otherwise noted

Module 9: Academic Argument

Argumentative thesis statements, learning objective.

- Recognize an argumentative thesis

A strong, argumentative thesis statement should take a stance about an issue. It should explain the basics of your argument and help your reader to know what to expect in your essay.

This video reviews the necessary components of a thesis statement and walks through some examples.

You can view the transcript for “Purdue OWL: Thesis Statements” here (opens in new window) .

Key Features of Argumentative Thesis Statements

Below are some of the key features of an argumentative thesis statement. An argumentative thesis is debatable, assertive, reasonable, evidence-based, and focused.

An argumentative thesis must make a claim about which reasonable people can disagree. Statements of fact or areas of general agreement cannot be argumentative theses because few people disagree about them. Let’s take a look at an example:

- Junk food is bad for your health.

This is not a debatable thesis. Most people would agree that junk food is bad for your health. Also what kind of junk food? Is there a way to make this thesis a bit more specific? A debatable thesis might be:

- Because junk food is bad for your health, the size of sodas offered at fast-food restaurants should be regulated by the federal government.

Reasonable people could agree or disagree with the statement. With this thesis statement, there is a more specific type of junk food (sodas), and there is call-to-action (federal regulation).

An argumentative thesis takes a position, asserting the writer’s stance. Questions, vague statements, or quotations from others are not argumentative theses because they do not assert the writer’s viewpoint. Let’s take a look at an example:

- Federal immigration law is a tough issue for American citizens.

This is not an arguable thesis because it does not assert a position. Start by asking questions about how to make this statement more specific. Which laws? What is the “tough issue” and why is it difficult? Take a look at this revision.

- Federal immigration enforcement law needs to be overhauled because it puts undue financial constraints on state and local government agencies.

This is an argumentative thesis because it asserts a position that immigration enforcement law needs to be changed. The “undue financial restraints” gives the writer a position to explore more.

An argumentative thesis must make a claim that is logical and possible. Claims that are outrageous or impossible are not argumentative theses. Let’s take a look at an example:

- City council members are dishonest and should be thrown in jail.

This is not an argumentative thesis. City council members’ ineffectiveness is not a reason to send them to jail unless they have broken the law. A more useful question is to ask why are they dishonest? What can they do to improve?

- City council members should not be allowed to receive cash incentives from local business leaders.

This is an arguable thesis because it is possible and reasonable to set ethical practices for business leaders.

Evidence-Based

An argumentative thesis must be able to be supported by evidence. Claims that presuppose value systems, morals, or religious beliefs cannot be supported with evidence and therefore are not argumentative theses. Let’s take a look at an example:

- Individuals convicted of murder have committed a sin and they do not deserve additional correctional facility funding.

This is not an argumentative thesis because its support rests on religious beliefs or values rather than evidence. Let’s dig a bit deeper to think about what specifically you can address as a writer and why it is important to your argument. Let’s take a look at this revision:

- Rehabilitation programs for individuals serving life sentences should be funded because these programs reduce violence within prisons.

This is an argumentative thesis because evidence such as case studies and statistics can be used to support it. The subject is a bit more specific (individuals serving life sentences) and the claim can be supported with research (programs that reduce violence within prisons).

An argumentative thesis must be focused and narrow. A focused, narrow claim is clearer, more able to be supported with evidence, and more persuasive than a broad, general claim. Let’s take a look at an example:

- The federal government should overhaul the U.S. tax code.

This is not an effective argumentative thesis because it is too general (Which part of the government? Which tax codes? What sections of those tax codes?). This is more of a book-length project and it would require an overwhelming amount of evidence to be fully supported. Let’s take a look at a revision:

- The U.S. House of Representatives should vote to repeal the federal estate tax because the revenue generated by that tax is negligible.

This is an effective argumentative thesis because it identifies a specific actor and action and can be fully supported with evidence about the amount of revenue the estate tax generates. By starting with a too broad focus, you can ask questions to create a more specific thesis statement.

In the practice exercises below, see if you can recognize and evaluate argumentative thesis statements. Keep in mind that a sound argumentative thesis should be debatable, assertive, reasonable, evidence-based, and focused. If you choose the incorrect response, read why it is not an argumentative thesis.

- Argumentative Thesis Statements. Provided by : University of Mississippi. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Argumentative Thesis Activity. Provided by : Excelsior College. Located at : http://owl.excelsior.edu/argument-and-critical-thinking/argumentative-thesis/argumentative-thesis-activity/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Purdue OWL: Thesis Statements. Provided by : OWLPurdue. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LKXkemYldmw . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.12.9: Argumentative Thesis Statements

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 219053

Learning Objective

- Recognize an arguable thesis

Below are some of the key features of an argumentative thesis statement.

An argumentative thesis is . . .

An argumentative thesis must make a claim about which reasonable people can disagree. Statements of fact or areas of general agreement cannot be argumentative theses because few people disagree about them.

Junk food is bad for your health is not a debatable thesis. Most people would agree that junk food is bad for your health.

Because junk food is bad for your health, the size of sodas offered at fast-food restaurants should be regulated by the federal government is a debatable thesis. Reasonable people could agree or disagree with the statement.

An argumentative thesis takes a position, asserting the writer’s stance. Questions, vague statements, or quotations from others are not argumentative theses because they do not assert the writer’s viewpoint.

Federal immigration law is a tough issue about which many people disagree is not an arguable thesis because it does not assert a position.

Federal immigration enforcement law needs to be overhauled because it puts undue constraints on state and local police is an argumentative thesis because it asserts a position that immigration enforcement law needs to be changed.

An argumentative thesis must make a claim that is logical and possible. Claims that are outrageous or impossible are not argumentative theses.

City council members stink and should be thrown in jail is not an argumentative thesis. City council members’ ineffectiveness is not a reason to send them to jail.

City council members should be term limited to prevent one group or party from maintaining control indefinitely is an arguable thesis because term limits are possible, and shared political control is a reasonable goal.

Evidence Based

An argumentative thesis must be able to be supported by evidence. Claims that presuppose value systems, morals, or religious beliefs cannot be supported with evidence and therefore are not argumentative theses.

Individuals convicted of murder will go to hell when they die is not an argumentative thesis because its support rests on religious beliefs or values rather than evidence.

Rehabilitation programs for individuals serving life sentences should be funded because these programs reduce violence within prisons is an argumentative thesis because evidence such as case studies and statistics can be used to support it.

An argumentative thesis must be focused and narrow. A focused, narrow claim is clearer, more able to be supported with evidence, and more persuasive than a broad, general claim.

The federal government should overhaul the U.S. tax code is not an effective argumentative thesis because it is too general (What part of the government? Which tax codes? What sections of those tax codes?) and would require an overwhelming amount of evidence to be fully supported.

The U.S. House of Representative should vote to repeal the federal estate tax because the revenue generated by that tax is negligible is an effective argumentative thesis because it identifies a specific actor and action and can be fully supported with evidence about the amount of revenue the estate tax generates.

- Argumentative Thesis Statements. Provided by : University of Mississippi. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Master Your Homework

- Do My Homework

Thesis or No Thesis: Research Papers Explained

Writing research papers is a common task for university students, but the requirements and expectations of such tasks can vary greatly depending on whether or not the student is expected to produce a thesis. This article will provide an overview of these two types of assignments, their key differences, and advice for successfully writing either type. We will cover topics including what constitutes each assignment’s primary purpose; content requirements; time commitments; and ultimately which type might be best suited for your individual needs in terms of academic success.

I. Introduction to Thesis or No Thesis: Research Papers Explained

Ii. advantages and disadvantages of writing a thesis for a research paper, iii. what is required when choosing the option of not writing a thesis, iv. benefits of not writing a thesis in an academic setting, v. factors that may influence the decision on whether to write a thesis or not, vi. key considerations regarding crafting a non-thetical project, vii. conclusion – weighing out pros and cons before making your choice.

Research papers can either require a thesis or not. It all depends on the type of paper and what subject it is focusing on. When considering whether a research paper requires a thesis, there are several key points to consider.

- The scope of the topic: If you’re writing about an overview of something broad such as cultural differences between two countries, then your research paper may be better suited without one specific argument laid out in a thesis statement.

- The complexity level: Complex topics usually do need some form of guiding thread which will often take shape with the help of well-crafted arguments from within your thesis statement.

- Your audience: Your readers will determine how formal or informal your final product needs to be. An academic project might need more rigor than if you were presenting at an industry conference for example.

In conclusion, it’s important to note that no matter what direction you take when deciding does research paper need a thesis—it should ultimately remain focused enough so that any conclusions drawn through researching this particular topic stay firmly grounded.

The choice to write a thesis for a research paper can be both advantageous and disadvantageous, depending on the context. It is important to consider each option carefully before making a final decision.

One of the primary advantages of writing a thesis is that it demonstrates an in-depth knowledge about the topic being studied. Writing an effective thesis requires extensive research into related topics and trends in order to arrive at informed conclusions. Additionally, developing one’s own hypotheses allows for more creative expression when compared with simply summarizing existing data or literature reviews. Finally, having written out these ideas provides readers with tangible evidence regarding your understanding of the subject matter, potentially leading to greater recognition within academia as well as among peers working within similar fields.

- Disadvantages

Writing a thesis also has certain drawbacks; namely, it may require substantial additional time commitments which could delay other obligations such as work responsibilities or family commitments. Furthermore, does every research paper need its own unique thesis? In some cases no – providing thorough analysis without an explicit statement would suffice – while others may require originality from start-to-finish due to supervisor requirements or academic protocols applicable within specific disciplines/universities etc.. Lastly – another challenge associated with composing powerful statements are potential language barriers encountered by non native speakers who might not be able understand subtle nuances required during proofreading processes prior submission deadlines .

What You Need to Know When the option of not writing a thesis is chosen, certain requirements must still be met. It’s important to understand what those are in order to get an adequate grade and obtain your degree:

- Courses taken during the program should reflect expertise in one specific field.