Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Procrastinator's Guide to a PhD: How to overcome procrastination and complete your dissertation

Procrastinating is an occupational hazard of doing a PhD. But what if you already have procrastination issues? It’s one thing to start as a well-organised, diligent student and then lapse when faced with the lack of deadlines and accountability. It’s another to have been flying by the seat of your pants for the last several years, pulling all-nighters to finish assignments and cramming for exams. What to do? As a recovering procrastinator myself, with several decades of bad habits to overcome, I want to reassure you that change is possible! You can use your well-honed skill in mind games for good instead of evil. The happy news is that if you’ve made it this far, you’ve got all the brains you need to succeed—you just have to know what to do with them. At the end of the day, it’s perseverance, not brilliance, that will get you to your goal. Whether you have long dabbled in the dark art of procrastination or you’re a relative newcomer, you’ll find something here to help you achieve your PhD. Note: The focus of this book is on the thesis or dissertation, not on the coursework and qualifying exams which are part of doctoral studies in the USA.

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

How to Stop Procrastinating

- Alice Boyes

Seven strategies backed by science

Do you keep postponing work you need to do? The problem probably stems from one of three things: your habits and systems (or lack thereof), your desire to avoid negative emotions (like anxiety and boredom), or your own flawed thinking patterns (which can make a task seem harder than it is). Luckily, there are simple strategies for managing each.

To develop good habits, for instance, do your important work in a consistent pattern daily: After I do this, I do my deep work. Devise a system for starting new tasks (drawing on one you’ve handled well); that will make it easier to get the ball rolling. When a task makes you anxious, do the easiest part first and progress from there; motivate yourself to do a boring task with a reward for completing it. And if you’re cognitively blocked, consider what would make a task impossible—and then identify its opposite.

Novel work often is filled with friction. You must recognize that tension doesn’t mean you’re not making progress. And if a project still feels overwhelming, tackle it in small chunks of time, not big ones.

Most of us procrastinate . We feel guilty about it and criticize ourselves for it. And yet we still do it. Why? Because of at least three factors: the absence of good habits and systems (poor discipline), intolerance for particular emotions (like anxiety or boredom), and our own flawed thinking patterns.

- Alice Boyes , PhD is a former clinical psychologist turned writer and the author of The Healthy Mind Toolkit , The Anxiety Toolkit , and Stress-Free Productivity .

Partner Center

How to Stop Procrastinating: A Guide for PhD Students and Academics

To keep up to date, or follow our social media, the author of this post:.

Jayron Habibe

A finishing PhD students in Medical Biochemistry. He has a love for writing about practical tools that make life as a PhD student just a little bit easier. Learn more about Jayron

Posts recommended by Jayron:

The Best Project Management Methods for Researchers and Academics

What Is Project Management And Why Do You Need It Project management methods are the

The Art of Efficient Note Taking: Strategies to Excel in Your Academic Journey

Why is Note Taking Important for Academics? Note taking is a skill that lies at

6 powerful lessons from running a marathon during your PhD

What is a Marathon? Doing a PhD is often compared to running a marathon. But

Join our Team!

Support us.

🧠Introduction

As a PhD student or academic, you are well aware of the unique challenges that come with managing research projects and meeting deadlines. However, one common hurdle that can hinder your progress is the tendency to start procrastinating.

You may find yourself putting off important tasks, succumbing to distractions, and struggling to make the most of your time. But fear not! This comprehensive guide is specifically designed to help PhD students and academics like you overcome procrastination and maximize productivity.

In the world of academia, productivity is not just a buzzword; it is essential for achieving research goals, making significant contributions to your field, and maintaining a healthy work-life balance . By adopting effective strategies and implementing practical techniques, you can break free from the cycle of procrastination and optimize your productivity, ultimately leading to greater success and personal fulfillment.

Throughout this guide, we will explore a range of proven strategies tailored to the unique needs of PhD students and academics. You will discover how to create a daily to-do list that encompasses research tasks, deadlines, and academic responsibilities. We’ll delve into the power of time blocking and how it can help you allocate dedicated time for research, writing, teaching, and personal development. You’ll also learn how to find your optimal working style, incorporating techniques such as deep work sessions, or collaborative sessions that resonate with your workflow.

Rewarding yourself for research and academic milestones is vital for maintaining motivation, so we’ll explore how to celebrate your achievements along the way. We’ll discuss the importance of minimizing context switching, avoiding distractions, and maintaining focus during crucial work sessions.

By implementing the strategies outlined in this guide, you will not only overcome procrastination but also unlock your full potential as a PhD student or academic. The path to success is paved with intentional, focused, and productive work. Are you ready to stop procrastinating and embark on a journey of enhanced productivity? Let’s dive in and transform your research and academic experience.

🗒️Daily To-Do List for Researchers and Academics

A well-structured and thoughtfully crafted daily to-do list is a powerful tool for PhD students and academics. It provides a roadmap for your day, helping you stay organized, focused, and on track with your research and academic commitments.

It is important to create a to-do list that reflects your priorities and aligns with your long-term goals. Start by capturing all the tasks and responsibilities you need to address, including research activities, writing assignments, teaching duties, meetings, and administrative tasks. Be thorough in this process to ensure nothing falls through the cracks.

Another valuable tip is to break down larger tasks into smaller, actionable steps . This approach helps prevent overwhelm and allows you to make progress incrementally. For instance, if you have a research paper to write, break it down into phases like conducting literature reviews, collecting data, outlining, drafting, and revising. By tackling one step at a time, you’ll feel a sense of accomplishment and stay motivated throughout the process.

Furthermore, assigning realistic time estimates to each task helps you allocate your time effectively and avoid over-committing. This practice ensures that you have a clear understanding of the time required for each task, preventing unnecessary stress and frustration.

Once you have your list of tasks, it’s crucial to prioritize them effectively. Here, you can use the concept of “ABC prioritization,” which involves categorizing tasks into three levels of importance: A, B, and C. A-tasks are high-priority and have a significant impact, B-tasks are important but less urgent, and C-tasks are those that can be deferred or delegated if possible.

To take your prioritization a step further, you can use the Eisenhower Matrix, a productivity framework that classifies tasks into four quadrants: important and urgent, important but not urgent, urgent but not important, and not important or urgent. This matrix helps you identify critical tasks that require immediate attention and separate them from tasks that can be scheduled or eliminated.

Lastly, review and update your to-do list regularly . Priorities may shift, deadlines may change, and new tasks may arise. By taking a few minutes at the beginning or end of each day to review and adjust your to-do list, you ensure that it remains relevant, up-to-date, and aligned with your overall goals.

If you’d like to use an app that makes creating to-do lists super easy I would recommend checking out Todoist . It has tons of awesome features while being extremely easy and simple to just get started with. It also happens to be my to-do list app of choice so if you’re interested just check it out.

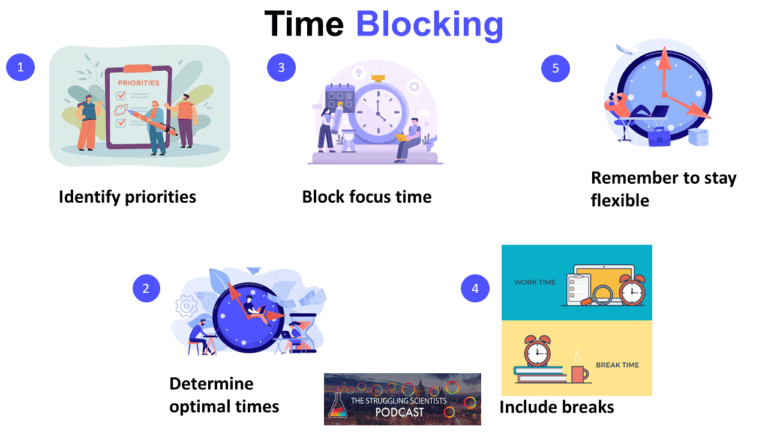

⏳Time Blocking for Researchers and Academics

Time blocking is a powerful technique that allows PhD students and academics to optimize their productivity by allocating dedicated blocks of time for specific tasks or activities. By implementing this strategy, you can effectively manage your workload, reduce distractions, and make significant progress in your research and academic endeavors.

Time blocking involves dividing your day into distinct time slots, each dedicated to a specific task or type of activity. This structured approach helps create a sense of focus and clarity, enabling you to prioritize and complete tasks more efficiently. To make the most of time blocking, consider the following techniques:

Identify Your Key Priorities:

Before you begin time blocking, identify your most important priorities. These may include research activities, writing, data analysis, teaching responsibilities, meetings, or personal development. By having a clear understanding of your priorities, you can allocate sufficient time to each area.

Determine Optimal Time Slots

Consider your energy levels, cognitive peaks, and natural rhythms when determining your time slots. Some individuals are more productive in the morning, while others thrive in the afternoon or evening. Find the time slots that work best for you and align them with tasks that require deep focus and concentration.

Block Focus Time

Designate uninterrupted periods for deep work and focused tasks. During these time blocks, eliminate distractions, such as turning off notifications, closing unnecessary tabs, and creating a conducive work environment.

Include Breaks

Recognize the importance of breaks and transition time between tasks. Schedule short breaks to recharge and refresh your mind. Additionally, allocate buffer time between tasks to allow for a smooth transition and avoid feeling rushed or overwhelmed.

Flexibility

While time blocking provides structure, it’s essential to remain flexible. Unexpected events or new tasks may arise, requiring adjustments to your schedule. Embrace the flexibility to rearrange your time blocks when necessary, ensuring that you stay responsive to changing priorities.

Remember, the goal of time blocking is not to fill every minute of your day with tasks. It’s about creating a balance between focused work, breaks, and other essential activities. By allocating specific time slots for each task or responsibility, you gain clarity on your commitments and avoid the pitfalls of multitasking.

Additionally, time blocking can help manage the tendency to overcommit. By allocating realistic time slots for tasks, you gain a better understanding of how much you can accomplish within a given timeframe. This practice prevents the stress and frustration that can arise from unrealistic expectations and allows you to set achievable goals.

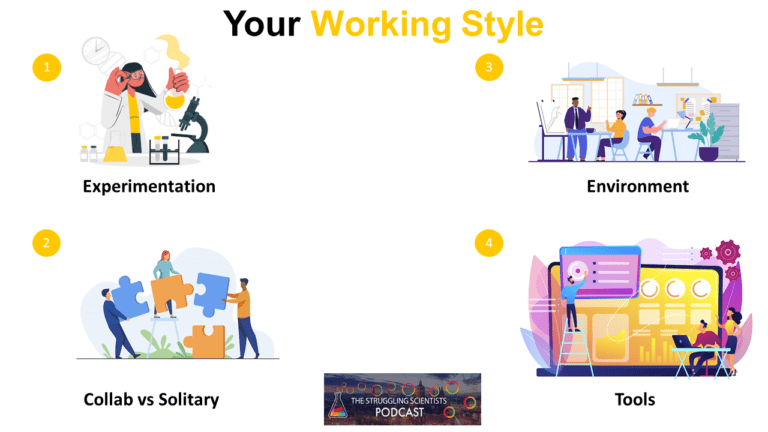

🛠️Discovering Your Optimal Working Style

Finding your optimal working style is crucial for enhancing productivity as a PhD student or academic. Each individual has unique preferences, strengths, and rhythms when it comes to work. By understanding and embracing your working style, you can tailor your approach to research and academic tasks, ultimately boosting your efficiency and output. Here are some key considerations to help you discover your optimal working style:

Experimentation

Don’t be afraid to experiment with different working styles and techniques. Try out various approaches such as the Pomodoro Technique, which involves working in focused sprints followed by short breaks, or deep work sessions where you dedicate uninterrupted time to intensive tasks. Evaluate the outcomes and determine what resonates with you the most.

Collaborative vs. Solitary Work

Consider whether you thrive in collaborative settings or if you perform better working independently. PhD students and academics often engage in team projects or research collaborations, but some tasks may require concentrated solitary work. Finding the right balance that suits your working style is essential for maintaining productivity.

Environmental Factors

Your physical work environment can have a significant impact on your productivity. Some individuals thrive in a quiet and organized space, while others prefer a bustling and interactive setting. Experiment with different environments, and create a workspace that promotes focus and minimizes distractions.

Workflow Tools

Explore productivity tools and technology that align with your working style. Digital tools like project management software, note-taking apps, or reference management systems can streamline your research process. Find tools that enhance your workflow and integrate seamlessly with your working preferences.

Remember, discovering your optimal working style is a continuous journey. As you progress through your academic career, your needs and preferences may evolve. Stay open to adapting and refining your approach to ensure it remains aligned with your goals and aspirations.

🍬 Rewarding Yourself While Working

Rewarding yourself while working can be a powerful motivator to overcome procrastination and maintain focus as a PhD student or academic. By incorporating intentional rewards into your work routine, you can create a positive reinforcement system that boosts your productivity and enhances your overall satisfaction. Here are some strategies to consider:

Milestone Celebrations

Break down your work into smaller milestones and celebrate each achievement along the way. For example, completing a section of a research paper, reaching a specific word count, or finishing a challenging experiment can all be acknowledged as milestones. Treat yourself to a small reward, such as a coffee break, a short walk, or a few minutes of enjoyable leisure activities.

Time-Based Rewards

Set specific time intervals during your work session, and reward yourself with short breaks or mini-rewards when you reach those intervals. This technique can be particularly effective when using the Pomodoro Technique, where you work for a set period, like 25 minutes, and then take a 5-minute break. Use these breaks to do something you enjoy, like reading a book, listening to music, or engaging in a brief mindfulness exercise.

Meaningful Incentives

Identify rewards that are personally meaningful and aligned with your interests or hobbies. This could be engaging in a favorite recreational activity, treating yourself to a delicious snack, or indulging in a leisurely activity you enjoy. The key is to choose rewards that bring you joy and provide a sense of rejuvenation and fulfillment.

Gamify Your Tasks

Turn your work into a game by setting up challenges or creating a points system. Assign point values to different tasks, and challenge yourself to accumulate a certain number of points within a specific timeframe. When you reach your goal, reward yourself with a prize or treat. This gamification approach adds an element of fun and excitement to your work, making it more engaging and enjoyable.

Social Accountability

Share your goals and progress with a trusted friend, colleague, or mentor. Establish a system of social accountability where you can celebrate your accomplishments together. This external validation and support can be a rewarding experience and provide an additional incentive to stay focused and productive.

Remember, the rewards you choose should be small, enjoyable, and in moderation. The purpose is to create positive associations with your work and maintain a healthy work-life balance. By incorporating rewards into your work routine, you can cultivate a positive mindset, boost your motivation, and reduce the likelihood of procrastination.

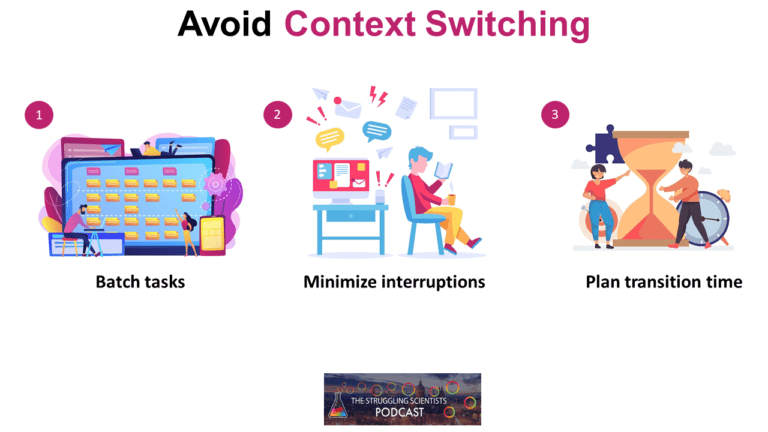

🕹️Avoiding Context Switching

Avoiding context-switching and cultivating mindfulness are essential practices for maximizing productivity and maintaining focus as a PhD student or academic. These strategies help minimize distractions, enhance concentration, and promote a sense of clarity and presence in your work. Here are some tips to minimize context switching:

Batch Similar Tasks

Group similar tasks together and allocate dedicated time blocks for them. For example, schedule a specific block of time for reading and responding to emails, another block for data analysis, and another for writing. By focusing on one type of task at a time, you reduce the need to constantly switch gears and maintain a higher level of efficiency.

Minimize Interruptions

Identify and eliminate sources of interruptions and distractions in your work environment. Silence or disable unnecessary notifications on your devices, inform colleagues or family members about your focused work time, and create boundaries to protect your uninterrupted work blocks.

Plan Transition Time

When switching between tasks or projects, allocate buffer time to mentally transition and prepare for the upcoming task. This allows you to wrap up one task effectively and transition smoothly to the next, minimizing the disruption to your focus and productivity.

🤯Conclusion

In the fast-paced world of academia, mastering productivity techniques is essential for PhD students and academics to thrive and achieve their goals. By implementing strategies such as creating a well-structured daily to-do list, practicing time blocking, finding what works for you, rewarding yourself while working, and avoiding context switching you can overcome procrastination, maintain focus, and maximize your productivity.

Remember, productivity is not a one-size-fits-all approach. It requires experimentation, self-reflection, and continuous refinement to find the strategies that work best for you as a PhD student or academic. Stay open to exploring new techniques and adapting your workflow as needed. The journey toward productivity is a personal one, and what works for others may not work the same for you.

As you apply these productivity principles, keep in mind the unique challenges and demands of being a PhD student or academic. Embrace your strengths, leverage your resources, and seek support from your peers, mentors, or productivity communities. Together, you can navigate the complexities of academic life and achieve remarkable results.

Ultimately, productivity is not just about getting more things done—it’s about creating a fulfilling and balanced academic experience. By optimizing your workflow, you can allocate time for your research, teaching, personal growth, and self-care. Remember to celebrate your accomplishments, maintain a healthy work-life balance, and prioritize your well-being along the way.

Now, armed with these productivity strategies and a commitment to action, it’s time to embark on your journey towards enhanced productivity as a PhD student or academic. Embrace the opportunities that lie ahead, stay focused on your goals, and make the most of your academic pursuits

Start by implementing one or two strategies from this blog, and gradually incorporate additional techniques into your routine. Remember, small steps can lead to significant improvements over time. Embrace the power of productivity and unleash your full potential as a successful PhD student or academic.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Other Posts you might like:

How to prepare PhD students for their career

Traditionally, PhDs are trained within academia with the perspective of landing an academic job. But

A Hitchhikers Guide to a PhD: Don’t panic!

For effective learning make sure you get enough sleep

We spend approximately one-third of our lives asleep. Despite the vast amount of time we

Breaking the Cycle of Procrastination: Strategies for PhD Students to Stay Motivated and On Track

Introduction

Have you ever found yourself staring at the computer screen, knowing you should be working on your dissertation, yet somehow, you end up spiraling down a YouTube rabbit hole or cleaning your apartment for the fifth time this week? You're not alone. Procrastination is a common foe for many PhD students, acting as a significant barrier to academic success and personal well-being. But what if I told you that breaking free from this cycle is not only possible but can be the turning point in your academic journey? This blog post is your roadmap out of the procrastination trap, offering practical strategies and insights tailored for PhD students. Whether you're struggling with starting your literature review, data analysis, or writing your findings, read on to transform your approach and take control of your PhD journey.

Understanding Procrastination

The psychology behind procrastination.

Procrastination isn't merely a symptom of poor time management but a complex psychological behavior often rooted in anxiety, fear of failure, or a quest for perfection. For many, it serves as a defense mechanism to avoid negative emotions associated with daunting tasks. This understanding is pivotal for PhD students who face high-stakes projects that can trigger deep-seated fears. Recognizing that procrastination is more about managing emotions than managing time can be a liberating insight, paving the way for more effective coping strategies that address the root causes rather than just the symptoms.

Common Procrastination Triggers for PhD Students

PhD students are uniquely prone to procrastination due to the nature of their work, which involves long-term projects with high levels of uncertainty and frequent isolation. Identifying personal triggers—whether it's the fear of starting a complex analysis, the pressure to publish, or the overwhelming scope of writing a dissertation—can illuminate the path to tailored strategies that directly address these challenges. By understanding these triggers, students can begin to dismantle the barriers to their productivity, one step at a time.

Strategic Planning and Goal Setting

Breaking down your phd journey into manageable tasks.

The enormity of the PhD journey can paralyze even the most dedicated students. Breaking down this journey into smaller, manageable tasks can demystify the process and make each step feel more achievable. This strategy not only simplifies the workload but also provides clear, immediate goals that can boost motivation and satisfaction through regular accomplishments. Each small task completed is a step forward, reducing the overall anxiety and making the larger goal seem more attainable.

The Importance of Setting Realistic Deadlines

Realistic deadlines are crucial for maintaining momentum and focus. They create a sense of urgency, which can help combat the paralysis often caused by open-ended projects. By setting achievable deadlines, students can foster a routine of success and progress, building confidence and reducing the temptation to procrastinate. Moreover, these deadlines encourage regular reflection and adjustment, allowing students to stay aligned with their goals and adapt their strategies as needed.

Creating a Conducive Work Environment

Minimizing distractions and setting boundaries.

A conducive work environment is essential for sustained productivity. This means not only arranging a physical space that supports focused work but also setting clear boundaries with others to protect this space and time. Minimizing distractions—be it through noise-canceling headphones, a clutter-free desk, or digital tools that block access to social media—can significantly enhance one's ability to concentrate. Establishing and communicating these boundaries with peers and family members can further safeguard your productivity, ensuring that your dedicated work hours remain uninterrupted. For more insights on creating an effective work environment, explore the strategies outlined in " Overcoming Procrastination in Your Doctoral/PhD Dissertation Writing: Strategies for Success."

The Role of Technology in Combating Procrastination

Technology, often seen as a source of distraction, can also be a powerful ally in the fight against procrastination. Tools and apps designed to enhance focus, track time, and block distractions can transform your work habits. From project management software that keeps you organized and on track, to apps that limit your time on distracting websites, technology offers a range of solutions tailored to different needs and preferences. Leveraging these tools can help you create a more disciplined work routine, making it easier to stay on course. Discover how technology can aid in overcoming procrastination by listening to the "Overcoming Procrastination in Academic Writing" podcast.

Motivation and Self-Care

Building a support network.

A robust support network can be a lifeline during the PhD journey. Connecting with peers, mentors, and family members who understand and support your goals can provide both motivation and accountability. Whether it's through regular study groups, mentorship meetings, or simply sharing updates with loved ones, these connections can offer encouragement, advice, and a sense of community that combats the isolation and self-doubt that often accompany procrastination.

The Importance of Self-Care

Self-care is a critical, yet often overlooked, component of academic success. Regular breaks, physical exercise, and engaging in hobbies can significantly improve mental health and overall well-being. These activities provide necessary respite from the demands of academic work, helping to replenish energy levels and enhance focus. Recognizing self-care as a legitimate and essential part of your routine can prevent burnout and keep you more consistently productive in the long run.

Leveraging External Help

When to seek professional help.

There comes a point where external assistance may be the most effective strategy for overcoming procrastination. This could mean reaching out to academic advisors for guidance, utilizing writing centers for feedback on your work, or seeking professional services designed to support PhD students. Recognizing when you need help and taking the step to seek it out can be a game-changer, providing you with the resources and support needed to move past obstacles and maintain progress toward your goals.

How WritersER Can Assist in Your Academic Journey

WritersER is dedicated to helping PhD and doctoral candidates achieve their academic milestones within a six-month timeframe. Whether you're struggling with literature reviews, data analysis, or the writing process itself, WritersER offers tailored support to guide you through. Scheduling an admission interview with WritersER is not just about getting help with a specific project; it's about taking a decisive step towards academic success and reclaiming control over your academic journey.

Enhanced Time Management Techniques

The pomodoro technique: boosting productivity in short bursts.

The Pomodoro Technique, a time management method developed by Francesco Cirillo, is a proven strategy to enhance productivity and manage procrastination. It involves working in focused intervals, typically 25 minutes long, followed by a short break. This technique not only helps in maintaining high levels of concentration but also ensures regular rest periods, preventing burnout. For PhD students, this method can be particularly effective for tasks that require deep concentration, such as writing or data analysis. By breaking work into manageable intervals, the Pomodoro Technique can make daunting tasks seem more approachable and less intimidating.

Utilizing Time Blocking for PhD Tasks

Time blocking is a method where specific blocks of time are dedicated to individual tasks or types of work. This technique allows for a more organized and structured approach to managing the diverse responsibilities of a PhD student, from research and writing to teaching and personal development. By allocating specific times for each task, you can create a balanced schedule that accommodates both your academic and personal life, reducing the likelihood of procrastination due to overwhelm. Time blocking also encourages a disciplined approach to work, where each task receives focused attention, making it easier to progress steadily towards your goals.

Psychological Strategies to Overcome Procrastination

Reframing your mindset.

Changing how you perceive tasks can significantly impact your propensity to procrastinate. Viewing tasks as opportunities for learning and growth, rather than as burdens, can reduce anxiety and increase motivation. This shift in mindset can be particularly effective for PhD students, who often face complex and challenging projects. By reframing tasks as steps towards personal and professional development, the journey becomes more about growth and less about the pressure to perform perfectly. This perspective encourages a more positive approach to work, making it easier to start and sustain effort over time.

Overcoming the Perfectionism Trap

Perfectionism, while seemingly a positive trait, can be a significant barrier to productivity, leading to procrastination. The fear of not meeting high standards can prevent you from starting tasks, resulting in paralysis and stress. Overcoming this trap involves accepting that perfection is unattainable and that mistakes are part of the learning process. Setting realistic standards and focusing on progress rather than perfection can help alleviate the pressure that leads to procrastination. This approach not only reduces anxiety but also fosters a healthier, more productive work ethic.

Leveraging Technology and Tools

Project management apps for phd students.

Project management apps can be invaluable tools for PhD students, helping to organize tasks, deadlines, and priorities. Apps like Trello, Asana, and Microsoft Planner allow you to visualize your project in stages, set deadlines, and track progress. These tools can help demystify the PhD process, breaking it down into manageable parts and providing a clear sense of direction. By externalizing tasks and timelines, you can free up mental space for focused work, reducing the cognitive load and the tendency to procrastinate.

Distraction Blocking Software

Distraction blocking software can be a critical tool in minimizing procrastination. Apps like Freedom, Cold Turkey, and StayFocusd help limit your access to distracting websites and apps, allowing you to concentrate on your work. By creating a digital environment conducive to productivity, you can significantly reduce the temptation to stray from your tasks. For PhD students, who often rely on digital resources for research, these tools can be particularly effective in maintaining focus during work sessions.

Staying Motivated Through Community and Collaboration

Joining study groups and writing retreats.

Study groups and writing retreats offer structured environments for productivity and accountability. Joining a study group with fellow PhD students can provide mutual support and motivation, making it easier to tackle challenging tasks together. Writing retreats, whether organized informally with peers or through your institution, offer dedicated time and space for focused work, away from the usual distractions. These communal settings not only facilitate progress but also provide a sense of solidarity, helping to mitigate the isolation that can lead to procrastination.

Mentorship and Academic Coaching

Mentorship and academic coaching are invaluable resources for navigating the PhD journey. A mentor can offer guidance, support, and accountability, helping you to stay on track and focused on your goals. Academic coaches specialize in strategies for effective research, writing, and time management, offering personalized advice to overcome obstacles. These relationships can be a source of encouragement, providing external motivation and a clearer path forward, especially during challenging periods of the PhD process.

Physical and Mental Health Considerations

The importance of regular physical activity.

Regular physical activity is essential for maintaining mental and physical health, particularly during the stress-prone years of a PhD program. Exercise can reduce stress, improve mood, and increase mental clarity, making it easier to focus on your work. Incorporating activities like walking, running, or yoga into your daily routine can offer necessary breaks from the intensity of academic work, refreshing your mind and body. By prioritizing physical health, you can enhance overall productivity and reduce the likelihood of procrastination due to stress or fatigue.

Mindfulness and Stress Reduction Techniques

Mindfulness and stress reduction techniques can play a crucial role in managing the psychological triggers of procrastination. Practices such as meditation, deep breathing exercises, and mindfulness can help reduce anxiety, improve focus, and foster a more balanced emotional state. For PhD students, developing a mindfulness practice can offer a powerful tool for navigating the ups and downs of academic life, helping to maintain a sense of calm and purpose in the face of challenges.

Adapting to Changes and Setbacks

Flexible planning and adaptability.

The PhD journey is often unpredictable, with changes and setbacks being a normal part of the process. Developing flexibility in your planning and an adaptability mindset can help you navigate these challenges without losing momentum. This means being open to revising your goals and strategies as needed, learning from feedback, and finding alternative paths forward. By embracing adaptability, you can maintain resilience in the face of setbacks, turning potential obstacles into opportunities for growth.

Learning from Failure

Failure is an inevitable part of the learning process, especially in the context of a PhD. Rather than viewing setbacks as definitive losses, they can be seen as valuable learning experiences that contribute to your personal and academic development. Adopting a growth mindset, where failure is viewed as an opportunity to learn and improve, can help reduce the fear of making mistakes that often leads to procrastination. By reframing failure as a stepping stone rather than a stumbling block, you can maintain motivation and progress despite challenges. Additionally, here's a related YouTube video on How To Avoid Procrastination During Your Dissertation Writing Process. It could provide you a multi-faceted understanding of the topic.

Navigating the PhD journey requires overcoming the common hurdle of procrastination, a challenge that extends beyond mere time management to encompass psychological, environmental, and habitual dimensions. By adopting strategies such as enhanced time management techniques like the Pomodoro Technique and time blocking, addressing psychological factors through mindset reframing and combatting perfectionism, leveraging technology for organization and focus, and building a supportive community for motivation and accountability, students can significantly improve their productivity. Prioritizing physical and mental health through regular exercise and mindfulness practices, embracing flexibility, and viewing setbacks as learning opportunities are also crucial for maintaining momentum. Remember, the path to overcoming procrastination involves a multifaceted approach tailored to individual needs and challenges.

With the right mindset and tools, including seeking external support when necessary, such as services offered by WritersER, PhD students can break the cycle of procrastination, stay motivated, and progress confidently towards their academic milestones, turning every small step into a victory on their academic journey. Schedule a call with us at WritersER today and let's craft a roadmap to success tailored just for you. Click here to get started!

Procrastination and Science

Getting a phd in procrastination.

Faculty research has appeared in leading journals, including:

Our funding is competitive. We provide $25,000 annually for four years, support to attend up to three conferences per year, and other scholarship opportunities.

Why Calgary?

Calgary is Canada’s fourth largest city and was recently named the fifth most livable city in the world by The Economist. With thriving business and finance sectors — including international oil and gas companies — and thanks to the school’s close ties with the business community, Haskayne faculty and students have research access to many top businesses.

Entrance Requirements

GMAT/GRE requirement is competitive (typically 650 or higher); GPA: 3.5/4.0; TOEFL iBT: 100 or IELTS: 7.0

Share this:

4 thoughts on “ getting a phd in procrastination ”.

Any chance for those of us who didn’t read and apply concepts from your book in time to earn the prerequisite GPA being allowed into the program?

P.S. I’ve had The Procrastination Equation checked out of my local library for 6 weeks past the 2 automatic renewal periods, but opened and started reading it today. I may need to turn it in and check it out again to avoid the fines costing more than the book itself!

Usually they allow one PhD student for my entire department per year and we have to compete to see who gets it.

I’ll get back to you. Soon. I promise.

Interesting Read

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Procrastination

Is procrastination a coping mechanism or symptom, critically thinking about procrastination..

Posted April 30, 2024 | Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

- What Is Procrastination?

- Find a therapist near me

I’ve noticed of late a trend in online conversations revolving around the concept of procrastination . Of course, this could just be ‘the algorithm’ feeding me such discourse given my relationship with psychology; but, regardless of ‘reach’, such discussion hasn’t been entirely accurate and may be potentially damaging to people who are genuinely working through things. The picture painted in such discourse is that procrastination isn’t laziness, rather a coping mechanism .

To begin, procrastination refers to the putting off of some task (i.e. usually something important and/or something that the individual doesn’t want to do) and, typically, replacing said task with other less urgent tasks that are easier or more enjoyable to the person conducting them. Consider, the adage: ‘what you want to do tomorrow, do today and what you want to do later, do now’. Being proactive is celebrated, procrastination is not: the population usually looks upon procrastination as less than socially desirable – a character flaw, in ways. In addition to laziness, it’s often coupled with stereotypes associated with lack of motivation , lack of self-regulation and perhaps even a lack of capability. In many cases, procrastination is a result of one of these (if not multiple). However, it is also important to recognise that procrastination can be a coping mechanism.

Sure, procrastination and laziness are two different things. However, it is very easy to be lazy and then rationalise this by telling people that you’re a procrastinator. Procrastination has become an excuse and a scapegoat in this context. As a result, when people say that they are a procrastinator, I often imagine that they’re either lazy (and trying to mask it as procrastination) or that they’re genuinely using it to cope with some form and level of anxiety (whether they are aware of it or not). Indeed, I’m familiar with symptoms of anxiety and its manifestation in different forms. I know some anxious people who immediately engage in a task so as to avoid another thing looming over their heads. They want to get it off their desks as quick as possible – the antithesis of procrastination. I also know people who are the exact opposite – a post-grad student with anxiety once showed me their email account after going AWOL for a few weeks and there were over 3,000 unopened emails. That’s real procrastination.

With that, most people I know would refer to themselves as procrastinators, to some extent. Of course, I work with a lot of students, so this should come as no surprise. Students typically have a penchant for leaving things they don’t want to do until the last minute (e.g. assignments and studying), because they’re often either off having fun or are genuinely stressed out by the college workload (i.e. perhaps not being used to as much work from their younger school days). That’s youth for you – particularly in the sense that their ability to self-regulate isn’t yet fully developed. As we addressed with respect to ‘laziness’ above, procrastination is also a common excuse/rationale for low self-regulation.

However, though it is the case that procrastination can be a coping mechanism (perhaps the term symptom might be warranted in some cases), that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s good. You might say, well, it’s part of the process, or some derivation of this. If it’s an acute form of procrastination (i.e. short-term), then that’s reasonable (e.g. in light of a recent bereavement ). But, if the individual has a long history of procrastination, I’d wonder what they’re actually doing about it to better themselves (e.g. if they’re receiving treatment for their anxiety or whatever is the foundation for this coping mechanism). Blaming a coping mechanism for why you’re unable to take care of your business in a timely manner or do what you said you would isn’t a valid excuse if you’re not actively working on it – it just tells me you need a new coping mechanism.

Importantly, not all coping mechanisms are good – or adaptive. Many are maladaptive. For example, the development of a drinking problem is a classic example of a maladaptive coping mechanism. I would similarly categorise procrastination in this way – as a maladaptive coping mechanism. For example, if my boss landed me with a report on Monday that’s due Friday, I’m going to drop everything else that isn’t a priority and focus my attention on that report. Leaving it until Thursday night is a bad idea. Sure, you might get it done in time, but I’d question how much you were able to review, edit and amend said report upon its completion. If quality of the content is lacking or the report is late – and this is a regular occurrence – your boss is going to start looking for a replacement, regardless of your reason why. Sure, some people claim to work better under pressure (another rationalisation), but is that really tr ue ? Again, I’d question the sufficiency of time and effort to review, edit and amend, especially with the added pressure, stress and fatigue associated with leaving it until the last minute.

Playing devil’s advocate, it’s not entirely healthy to be so proactive that everything must be done immediately either (i.e. the aforementioned approach of getting it off your desk ASAP, so it doesn’t loom over your head). Depending on the context, such an approach is just as stressful as procrastination. There’s a happy medium between the two responses – aim to find the most appropriate time to complete the task in question, be it today, tomorrow, next week or in two months and organise it into your schedule . Making the plan to do it and sticking to said plan is both proactive and a sign of good organisation (an important disposition towards critical thinking ).

The point is that procrastination can indeed be a coping mechanism, but that doesn’t mean we should embrace it. Regardless of what you call it, procrastination remains largely maladaptive and can result in many adverse outcomes. Instead of resigning oneself to being a procrastinator – for whatever the rationale might be – it is important to make genuine efforts to cognitively reframe one’s approaches to undesirable tasks and be proactive. It will benefit the person and their mental well-being in the long run.

Christopher Dwyer, Ph.D., is a lecturer at the Technological University of the Shannon in Athlone, Ireland.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

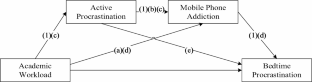

Examining bedtime procrastination through the lens of academic stressors among undergraduate students: academic stressors including mediators of mobile phone addiction and active procrastination

- Published: 26 April 2024

Cite this article

- Ran Zhuo ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0006-5947-160X 1

35 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The present study investigated the indirect effects of active procrastination and mobile phone addiction on the relationship between academic workload and bedtime procrastination. A total of 474 Chinese undergraduates were recruited to complete assessments on academic workload, active procrastination, mobile phone addiction, and bedtime procrastination. The results revealed that academic workload not only directly impacts bedtime procrastination but also has an indirect influence through the mediating factors of active procrastination and mobile phone addiction. The sheer volume of work crowds out students’ time, destroying the procrastinator’s time structure centered around leisure and diminishing the enjoyment of tasks. Additionally, the stress of work also makes it easier for students to become addicted to mobile phones, leading them to use their sleep time to compensate for the time lost due to their workload. These findings shed light on the interaction between mobile phone addiction and the daily lives of college undergraduates, as well as how they mutually influence each other. The study underscores the importance of schools in alleviating the academic burden placed on students.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Bedtime Procrastination and Fatigue in Chinese College Students: the Mediating Role of Mobile Phone Addiction

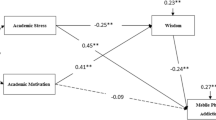

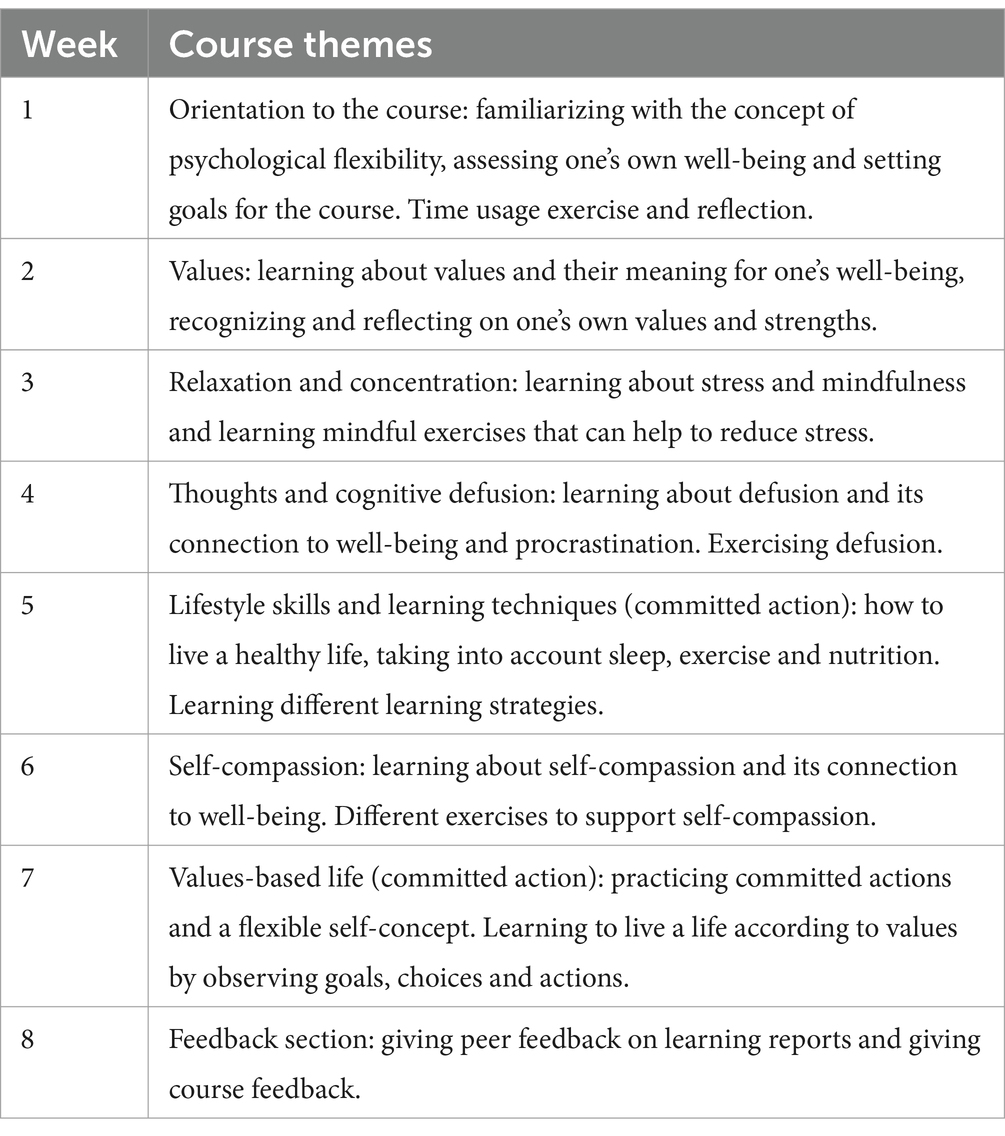

Associations Between Academic Motivation, Academic Stress, and Mobile Phone Addiction: Mediating Roles of Wisdom

Factors influencing bedtime procrastination in junior college nursing students: a cross-sectional study

Data availability.

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

Agnew, R. (1992). Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency*. Criminology , 30 (1), 47–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1992.tb01093.x

Article Google Scholar

An, H., Chung, S., & Suh, A. (2019). Validation of the Korean bedtime procrastination scale in young adults. Journal of Sleep Medicine , 16 , 41–47. https://doi.org/10.13078/jsm.19030

Bai, H., Li, X., Wang, X., Tong, W., Li, Y., & Hu, W. (2023). Active procrastination incubates more creative thinking: The sequential mediating effect of personal mastery and creative self-concept. Creativity Research Journal , 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2023.2171721

Bernecker, K., & Job, V. (2019). Too exhausted to go to bed: Implicit theories about willpower and stress predict bedtime procrastination. British Journal of Psychology , 111 (1), 126–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12382

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Cain, N., & Gradisar, M. (2010). Electronic media use and sleep in school-aged children and adolescents: A review. Sleep Medicine , 11 (8), 735–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2010.02.006

Campbell, R. L., & Bridges, A. J. (2023). Bedtime procrastination mediates the relation between anxiety and sleep problems. Journal of Clinical Psychology , 79 (3), 803–817. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23440

Chauhan, R. S., MacDougall, A. E., Buckley, M. R., Howe, D. C., Crisostomo, M. E., & Zeni, T. (2020). Better late than early? Reviewing procrastination in organizations. Management Research Review , 43 (10), 1289–1308. https://doi.org/10.1108/mrr-09-2019-0413

Choi, J. N., & Moran, S. V. (2009). Why not procrastinate? Development and validation of a new active procrastination scale. Journal of Social Psychology , 149 (2), 195–211. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.149.2.195-212

Chu, A. H., & Choi, J. N. (2005). Rethinking procrastination: Positive effects of “active” procrastination behavior on attitudes and performance. Journal of Social Psychology , 145 (3), 245–264. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.145.3.245-264

Corkin, D. M., Yu, S. L., & Lindt, S. F. (2011). Comparing active delay and procrastination from a self-regulated learning perspective. Learning and Individual Differences , 21 (5), 602–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.07.005

Coyne, S. M., Stockdale, L., & Summers, K. (2019). Problematic cell phone use, depression, anxiety, and self-regulation: Evidence from a three year longitudinal study from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Computers in Human Behavior , 96 , 78–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.02.014

Dalal, D. K., & Carter, N. T. (2015). Negatively worded items negatively impact survey research. In More statistical and methodological myths and urban legends (pp. 112–132). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428110391814

DeArmond, S., Matthews, R. A., & Bunk, J. (2014). Workload and procrastination: The roles of psychological detachment and fatigue. International Journal of Stress Management , 21 (2), 137–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034893

Deng, Y., Ye, B., & Yang, Q. (2022). COVID-19 related emotional stress and bedtime procrastination among college students in China: A moderated mediation model. Nature and Science of Sleep , 14 , 1437–1447. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S371292

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Eid, M. (2000). A multitrait-multimethod model with minimal assumptions. Psychometrika , 65 (2), 241–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294377

Eid, M., Lischetzke, T., Nussbeck, F. W., & Trierweiler, L. I. (2003). Separating trait effects from trait-specific method effects in multitrait-multimethod models: A multiple-indicator CT-C(M-1) model. Psychological Methods , 8 (1), 38–60.

Elhai, J. D., Dvorak, R. D., Levine, J. C., & Hall, B. J. (2017). Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. Journal of Affective Disorders , 207 , 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.030

Evans, D. R., Boggero, I. A., & Segerstrom, S. C. (2015). The nature of self-regulatory fatigue and “ego depletion”: Lessons from physical fatigue. Personality and Social Psychology Review , 20 (4), 291–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868315597841

Fan, X. W., Yang, Y., Wang, S., Zhang, Y. J., Wang, A. X., Liao, X. L.,… & Wang, Y. J. (2022). Impact of persistent poor sleep quality on post-stroke anxiety and depression: A national prospective clinical registry study. Nature and Science of Sleep , 14 , 1125–1135. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S357536

Guo, J., Meng, D., Ma, X., Zhu, L., Yang, L., & Mu, L. (2020). The impact of bedtime procrastination on depression symptoms in Chinese medical students. Sleep and Breathing , 24 (3), 1247–1255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-020-02079-0

Herzog-Krzywoszanska, R., & Krzywoszanski, L. (2019). Bedtime procrastination, sleep-related behaviors, and demographic factors in an online survey on a Polish sample. Frontiers in Neuroscience , 13 , 963. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00963

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal , 6 (1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jun, S., & Choi, E. (2015). Academic stress and Internet addiction from general strain theory framework. Computers in Human Behavior , 49 , 282–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.001

Khang, H., Kim, J. K., & Kim, Y. (2013). Self-traits and motivations as antecedents of digital media flow and addiction: The Internet, mobile phones, and video games. Computers in Human Behavior , 29 (6), 2416–2424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.05.027

Kim, K. R., & Seo, E. H. (2015). The relationship between procrastination and academic performance: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences , 82 , 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.02.038

Kim, S., Fernandez, S., & Terrier, L. (2017). Procrastination, personality traits, and academic performance: When active and passive procrastination tell a different story. Personality and Individual Differences , 108 , 154–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.12.021

Kroese, F. M., De Ridder, D. T., Evers, C., & Adriaanse, M. A. (2014). Bedtime procrastination: Introducing a new area of procrastination. Frontiers in Psychology , 5 , 611. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00611

Kuang-Tsan, C., & Fu-Yuan, H. (2017). Study on relationship among university students’ life stress, smart mobile phone addiction, and life satisfaction. Journal of Adult Development , 24 (2), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-016-9250-9

Leung, L. (2008). Linking psychological attributes to addiction and improper use of the mobile phone among adolescents in Hong Kong. Journal of Children and Media , 2 (2), 93–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482790802078565

Lian, L., You, X., Huang, J., & Yang, R. (2016). Who overuses Smartphones? Roles of virtues and parenting style in Smartphone addiction among Chinese college students. Computers in Human Behavior , 65 , 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.08.027

Liu, Q.-Q., Zhou, Z.-K., Yang, X.-J., Kong, F.-C., Niu, G.-F., & Fan, C.-Y. (2017a). Mobile phone addiction and sleep quality among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Computers in Human Behavior , 72 , 108–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.042

Liu, W., Pan, Y., Luo, X., Wang, L., & Pang, W. (2017b). Active procrastination and creative ideation: The mediating role of creative self-efficacy. Personality and Individual Differences , 119 , 227–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.033

Liu, Q.-Q., Zhang, D.-J., Yang, X.-J., Zhang, C.-Y., Fan, C.-Y., & Zhou, Z.-K. (2018). Perceived stress and mobile phone addiction in Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Computers in Human Behavior , 87 , 247–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.06.006

Ma, X., Meng, D., Zhu, L., Xu, H., Guo, J., Yang, L.,… & Mu, L. (2022). Bedtime procrastination predicts the prevalence and severity of poor sleep quality of Chinese undergraduate students. Journal of American College Health , 70 (4), 1104–1111. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1785474

Ma, X., Zhu, L., Guo, J., Zhao, Y., Fu, Y., & Mu, L. (2021). Reliability and validity of the Bedtime Procrastination Scale in Chinese college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology , 29 (4), 717–720.

Google Scholar

Magalhaes, P., Pereira, B., Oliveira, A., Santos, D., Nunez, J. C., & Rosario, P. (2021). The mediator role of routines on the relationship between general procrastination, academic procrastination and perceived importance of sleep and bedtime procrastination. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 18 (15), 7796. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18157796

Mah, C. D., Kezirian, E. J., Marcello, B. M., & Dement, W. C. (2018). Poor sleep quality and insufficient sleep of a collegiate student-athlete population. Sleep Health , 4 (3), 251–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2018.02.005

Maheshwari, G., & Shaukat, F. (2019). Impact of poor sleep quality on the academic performance of medical students. Cureus , 11 (4), e4357. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.4357

Majeur, D., Leclaire, S., Raymond, C., Leger, P. M., Juster, R. P., & Lupien, S. J. (2020). Mobile phone use in young adults who self-identify as being “Very stressed out” or “Zen”: An exploratory study. Stress and Health , 36 (5), 606–614. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2947

Mansano-Schlosser, T. C., Ceolim, M. F., & Valerio, T. D. (2017). Poor sleep quality, depression and hope before breast cancer surgery. Applied Nursing Research , 34 , 7–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2016.11.010

Mao, B., Chen, S., Wei, M., Luo, Y., & Liu, Y. (2022). Future time perspective and bedtime procrastination: The mediating role of dual-mode self-control and problematic smartphone use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 19 (16), 10334. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610334

Mei, S., Hu, Y., Wu, X., Cao, R., Kong, Y., Zhang, L.,… & Li, L. (2022). Health risks of mobile phone addiction among college students in China. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction , 21 (4), 2650–2665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00744-3

Ni, S., Li, H., Xu, J., & Choi, J. (2011). Revision of a new active procrastination scale for Chinese undergraduates. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology , 19 (4), 462–465.

Okun, M. L., Mancuso, R. A., Hobel, C. J., Schetter, C. D., & Coussons-Read, M. (2018). Poor sleep quality increases symptoms of depression and anxiety in postpartum women. Journal of Behavioral Medicine , 41 (5), 703–710. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-018-9950-7

Orhero, A. E., Okereka, O. P., & Okolie, U. C. (2023). Role Stressor and Work Adjustment of University Lecturers in Delta State. Ianna Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies , 5 (1), 124–135. https://iannajournalofinterdisciplinarystudies.com/index.php/1/article/view/114 .

Peng, Y., Zhou, H., Zhang, B., Mao, H., Hu, R., & Jiang, H. (2022). Perceived stress and mobile phone addiction among college students during the 2019 coronavirus disease: The mediating roles of rumination and the moderating role of self-control. Personality and Individual Differences , 185 , 111222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111222

Pinxten, M., De Laet, T., Van Soom, C., Peeters, C., & Langie, G. (2019). Purposeful delay and academic achievement. A critical review of the Active Procrastination Scale. Learning and Individual Differences , 73 , 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2019.04.010

Rahe, C., Czira, M. E., Teismann, H., & Berger, K. (2015). Associations between poor sleep quality and different measures of obesity. Sleep Medicine , 16 (10), 1225–1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2015.05.023

Reise, S. P., Morizot, J., & Hays, R. D. (2007). The role of the bifactor model in resolving dimensionality issues in health outcomes measures. Quality of Life Research , 16 (Suppl 1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9183-7

Sagherian, K., McNeely, C., Cho, H., & Steege, L. M. (2023). Nurses’ rest breaks and fatigue: The roles of psychological detachment and workload. Western Journal of Nursing Research , 45 (10), 885–893. https://doi.org/10.1177/01939459231189787

Schmidt, L. I., Baetzner, A. S., Dreisbusch, M. I., Mertens, A., & Sieverding, M. (2023). Postponing sleep after a stressful day: Patterns of stress, bedtime procrastination, and sleep outcomes in a daily diary approach. Stress and Health . https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3330

Schulz, A. D., Schöllgen, I., & Fay, D. (2019). The role of resources in the stressor–detachment model. International Journal of Stress Management , 26 (3), 306–314. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000100

Shaked, L., & Altarac, H. (2022). The possible contribution of procrastination and perception of self-efficacy to academic achievement. Journal of Further and Higher Education , 47 (2), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877x.2022.2102414

Shang, Z., Cao, Y., Cui, Z., & Zuo, C. (2023). Positive delay? The influence of perceived stress on active procrastination. South African Journal of Business Management , 54 (1), 3988. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajbm.v54i1.3988

Smit, B. W., & Barber, L. K. (2016). Psychologically detaching despite high workloads: The role of attentional processes. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 21 (4), 432–442. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000019

Song, T. J., Cho, S. J., Kim, W. J., Yang, K. I., Yun, C. H., & Chu, M. K. (2018). Poor sleep quality in migraine and probable migraine: A population study. The Journal of Headache and Pain , 19 (1), 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0887-6

Sonnentag, S. (2011). Recovery from fatigue: The role of psychological detachment. In Cognitive fatigue: Multidisciplinary perspectives on current research and future applications (pp. 253–272). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12343-012

Sonnentag, S., Kuttler, I., & Fritz, C. (2010). Job stressors, emotional exhaustion, and need for recovery: A multi-source study on the benefits of psychological detachment. Journal of Vocational Behavior , 76 (3), 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.06.005

Spector, P. E., & Jex, S. M. (1998). Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal Conflict at Work Scale, Organizational Constraints Scale, Quantitative Workload Inventory, and Physical Symptoms Inventory. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology , 3 (4), 356–367. https://doi.org/10.1037//1076-8998.3.4.356

Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin , 133 (1), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65

Sun, W., Yuan, J., Yu, Y., Wang, Z., Shankar, N., Ali, G.,… & Shan, G. (2016). Poor sleep quality associated with obesity in men. Sleep and Breathing , 20 (2), 873–880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-015-1193-z

Teoh, A. N., Ooi, E. Y. E., & Chan, A. Y. (2021). Boredom affects sleep quality: The serial mediation effect of inattention and bedtime procrastination. Personality and Individual Differences , 171 , 110460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110460

Tommasi, F., Ceschi, A., Du Plooy, H., Michailidis, E., & Sartori, R. (2023). The influence of workday experience on smartphones uses in commuting from work to home. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour , 97 , 268–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2023.07.016

Yang, X. J., Liu, Q. Q., Lian, S. L., & Zhou, Z. K. (2020). Are bored minds more likely to be addicted? The relationship between boredom proneness and problematic mobile phone use. Addictive Behaviors , 108 , 106426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106426

Zhang, Y., Li, S., & Yu, G. (2021). The longitudinal relationship between boredom proneness and mobile phone addiction: Evidence from a cross-lagged model. Current Psychology , 41 (12), 8821–8828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01333-8

Zhang, A., Xiong, S., Peng, Y., Zeng, Y., Zeng, C., Yang, Y., & Zhang, B. (2022a). Perceived stress and mobile phone addiction among college students: The roles of self-control and security. Front Psychiatry , 13 , 1005062. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1005062

Zhang, B., Liang, H., Luo, Y., Peng, Y., Qiu, Z., Mao, H.,… & Xiong, S. (2022b). Loneliness and mobile phone addiction in Chinese college students: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Psychology in Africa , 32 (6), 605–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2022.2121474

Zhang, X., Gao, F., Kang, Z., Zhou, H., Zhang, J., Li, J.,… & Liu, B. (2022c). Perceived academic stress and depression: The mediation role of mobile phone addiction and sleep quality. Frontiers in Public Health , 10 , 760387. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.760387

Zhu, Y., Huang, J., & Yang, M. (2022). Association between chronotype and sleep quality among Chinese college students: The role of bedtime procrastination and sleep hygiene awareness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 20 (1), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010197

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Present Address: School of Psychology, Fujian Normal University, 350007, Fuzhou, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ran Zhuo .

Ethics declarations

Participation in this study was completely voluntary. All the personally identifiable information was de-identified upon being collected. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

We declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work, there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service and/or company that could be construed as influencing the position presented in, or the review of, the manuscript entitled.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Zhuo, R. Examining bedtime procrastination through the lens of academic stressors among undergraduate students: academic stressors including mediators of mobile phone addiction and active procrastination. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06038-w

Download citation

Accepted : 19 April 2024

Published : 26 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06038-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mobile phone addiction

- Bedtime procrastination

- Undergraduate college students

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 23 April 2024

Relationship between academic procrastination, self-esteem, and moral intelligence among medical sciences students: a cross-sectional study

- Saeed Ghasempour ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9875-9127 1 ,

- Aliasghar Babaei ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0004-7860-7280 1 ,

- Soheil Nouri ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0001-2899-5420 1 ,

- Mohammad Hasan Basirinezhad ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3672-556X 2 &

- Ali Abbasi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0482-6208 3

BMC Psychology volume 12 , Article number: 225 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

330 Accesses

Metrics details

Academic procrastination is a widespread phenomenon among students. Therefore, evaluating the related factors has always been among the major concerns of educational system researchers. The present study aimed to determine the relationship of academic procrastination with self-esteem and moral intelligence in Shahroud University of Medical Sciences students.

This cross-sectional descriptive-analytical study was conducted on 205 medical sciences students. Participants were selected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria using the convenience sampling technique. The data collection tools included a demographic information form, Solomon and Rothblum’s Procrastination Assessment Scale-Students, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, and Lennick and Kiel’s Moral Intelligence Questionnaire, all of which were completed online. The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and inferential tests (multivariate linear regression with backward method) in SPSS software.

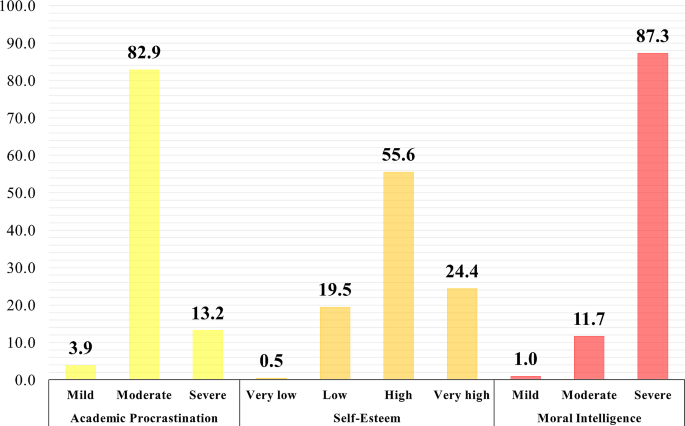

96.1% of participating students experienced moderate to severe levels of academic procrastination. Based on the results of the backward multivariate linear regression model, the variables in the model explained 27.7% of the variance of academic procrastination. Additionally, self-esteem ( P < 0.001, β= -0.942), grade point average ( P < 0.001, β= -2.383), and interest in the study field ( P = 0.006, β= -1.139) were reported as factors related to students’ academic procrastination.

According to the findings of this study, the majority of students suffer from high levels of academic procrastination. Furthermore, this problem was associated with low levels of self-esteem, grade point average, and interest in their field of study.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Investigating factors associated with students’ academic performance has always been the focus of researchers in the education system [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. One of these factors is academic procrastination, which is a common phenomenon among students [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. This particular type of postponement refers to learners’ dominant and constant tendency to postpone academic tasks such that it affects their anticipated performance [ 6 ]. In general, two types of procrastination are observed in students’ homework. One type is purposeful, planned, and thoughtful postponement. For example, when students have to complete many assignments simultaneously, they prioritize some important assignments. Another type is irrational, self-defeating, and harmful postponement, which is known as academic procrastination [ 7 ]. Rothblum et al. (1986) propose two criteria in the definition and diagnoses of this problem: (a) tendency to always or almost always discard academic assignments and (b) always or almost always experiencing anxiety caused by such behavior. They emphasize that academic procrastination should include frequent postponement and considerable anxiety [ 8 ]. Research has shown that at least 70% of students are somehow involved in academic procrastination, and 50% always procrastinate in doing homework and learning course materials [ 9 , 10 ]. These figures redouble the need to evaluate academic procrastination and its related factors in this group.

Academic procrastination is a complex concept that depends on some factors. These factors are both affected by academic procrastination and can also decelerate its process. Therefore, it is essential to identify the underlying factors affecting students’ academic procrastination [ 11 ]. In addition, academic procrastination and related factors have not yet been well investigated and require more studies, especially among medical students [ 12 ].

Moreover, academic procrastination is associated with high levels of anxiety, depression, and feeling guilty in students and affects their self-esteem [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. Self-esteem is considered among the factors affecting students’ academic procrastination in various studies [ 16 , 17 , 18 ]. Self-esteem refers to our perception of ourselves, how we evaluate ourselves, and our self-evaluation of ourselves as individuals [ 19 , 20 , 21 ]. Coopersmith (1990) considers self-esteem as people’s evaluation of their worth and usually maintains, indicating an attitude of approval or disapproval. In other words, self-esteem is a personal judgment of one’s worth, which refers to a person’s feelings about their worth in various areas of life [ 22 ]. As one of the major factors that moderate psychosocial pressure, this concept forms based on family relationships, academic success, body image, social interaction, and sense of self-worth. In this respect, the importance of these contexts changes depending on individual differences and one’s growth [ 23 ].

Moral intelligence is another factor affecting students’ academic procrastination [ 24 ]. Moral intelligence is the capacity and ability to understand good issues from bad issues [ 25 ]. Indeed, this intelligence enhances appropriate behavior and can provide stability in social life over time through qualities (e.g., honesty, responsibility, forgiveness, and sympathy) and reduce misbehaviors. Moral intelligence reflects the fact that a person is not born moral or immoral but must learn good performance, conscientiousness, and responsibility [ 26 ]. According to Lennick and Kiel (2007), moral intelligence includes four principles: honesty, responsibility, forgiveness, and sympathy. The honesty principle refers to harmonization between people’s beliefs and actions. The responsibility principle is the acceptance of actions and their consequences, as well as mistakes and failures. The forgiveness principle includes awareness of faults and mistakes and forgiving oneself and others. Finally, the sympathy principle means paying attention to others [ 27 ].

As previously mentioned, academic procrastination is a prevalent phenomenon among students. Determining the factors associated with it has captured the attention of many researchers in the education system. However, there are limited studies on the relationship between psychological variables, such as self-esteem and moral intelligence, with academic procrastination. It seems that understanding the relationship between them will lead to providing appropriate solutions and approaches to reduce this problem and improve students’ academic performance. Therefore, since no study has been conducted to determine the relationship between these variables, this study aimed to investigate the relationship between academic procrastination, self-esteem, and moral intelligence among medical sciences students.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants.

This descriptive-analytical study was conducted on 205 Shahroud University of Medical Sciences students from April to September 2023. Participants were included in the study based on inclusion and exclusion criteria through the convenience sampling technique. This technique was chosen for its ease of implementation, high response rate to questionnaires, and frequent use in similar studies [ 28 ].

The inclusion criteria were studying at bachelor and professional doctorate levels (no history of studying in other universities) and having theoretical and practical courses. Besides, exclusion criteria were the history of suffering from serious mental illnesses (SMI) (such as Major Depression Disorder (MDD), Schizophrenia, Bipolar Disorder (BD), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Post-Traumatic Stress (PTSD), and other related disorders), using neuropsychological drugs (e.g., antidepressants, antipsychotics, anti-anxiety, and mood stabilizers), and the recent occurrence of unfortunate events or stressful events in the past six months, which was self-reported by the student.

The sample size was estimated to be 205 students based on the study by Uma et al. (2020) [ 29 ]. This estimation took into account a power of 90% at a confidence level of 95%, as well as a 15% attrition rate.

α = 0.05 β = 0.10 r = 0.24

Measurements

The data collection tool in this study consisted of four sections designed using the DigiSurvey system, a web-based questionnaire tool ( https://www.digisurvey.net/ ). The study objectives, along with the created link, were shared with students in their respective groups and channels on Telegram and WhatsApp social networks for them to complete in their free time.

Section 1. Demographic information form

Information related to gender, age, marital status, field of study, academic semester, previous semester grade point average (GPA), interest levels in the field of study, study hours, parent’s education, and student’s place of residence were asked in this form.

Section 2. Solomon and Rothblum’s Procrastination Assessment Scale-Students (PASS)