3 books you should read before you start your PhD

by Gertrude Nonterah PhD | Oct 18, 2021

Here are three books you should read before your start your PhD.

Congratulations! You’re about to start grad school!

These books will help to prepare your mind for PhD work and inspire you to continue when things get tough.

Grit by Angela Duckworth

Angela Duckworth is a psychology professor at the University of Pennsylvania. She has done a lot of work around grit, or determination, through difficult situations in your life. Starting your PhD is a difficult situation. Angela gives you a lot of research-backed data and stories that demonstrate how it is not necessarily people who have the most “natural talent” that are successful, but those with the most grit.

Atomic Habits by James Clear

James Clear has been writing about habits and the science of habits for a really long time. This book talks about building habits that will be lifelong habits. A habit is something that you do involuntarily. For instance, brushing your teeth. No one tells you to do it or how to do it. These are habits tend to be automatic. James Clear gives you researched based methods for building habits and turning something you want to do into a habit.

I particularly enjoyed the chapter about writing habits. I am a writer, therefore, found this especially intriguing. In the book, he talks about having daily devoted writing time and leaving everything that would distract him outside of the room. As a writer, he would also go to a place everyday to set the intention and set himself up for success instead of lounging on the couch or in his bed.

All through grad school you will be building habits that will help you get to the end goal of graduating and landing a job you enjoy. Reading this book will set you up for success as you build those new habits.

How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie

A really REALLY important part of your PhD education, which is not emphasized as much as I would like it to be, is networking.

As PhDs, we tend to think that because we’ve gone from college into grad school that the next automatic step is getting a job. The reality is that once you finish your PhD, you’ll have to go through a rigorous process of applying for jobs, interviewing, and negotiating employment. This work is made less rigorous when you have built a network within the academic or industry sphere that you would like to work in. Building relationships with people is the best way to get in the door at many places.

I wondered how valuable relationships were to the hiring process, so I spoke with an HR representative at UC San Diego where I used to work. One of the things that she told me was that new hires were not only based on resumes or applications. There was almost always a referral or word-of-mouth referral. I didn’t only hear this about academia, but also from a biotech company. They mostly hire based on referrals. So, if you don’t have these industry relationships built, there will be no referrals, and finding a job becomes more difficult.

Reading these three books will put you ahead of the curve when it comes to your mindset in graduate school.

Related posts:

- Nobody warned me of this BEFORE I finished my PhD

- 5 Tips to Survive The First Year of Your PhD

Recent Posts

- How to Speak Confidently at Work (Without Sounding Arrogant)

- How to Be The CEO of Your Career This Year

- 7 ways to get the most out of LinkedIn in 2024.

- How to deal with a career gap on your resume

- How to make a non-academic career change when you have ZERO experience.

Recommended Reading

Note: As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. In other words, I may earn a small commission if you click on a link on this page to purchase a book from Amazon.

This list is aimed at graduate students, postdocs, and other PhDs who are actively looking for paid employment or exploring career options. It includes both practical resources, books that combine advice with inspiration, ones that hope to advocate for better systems while also breaking things down for job seekers, as well as memoirs and novels. The focus here is on books written for graduate students and PhDs, but I’ve also included what I think as key or otherwise useful texts with a much broader intended audience.

What’s not on this list? Books that focus almost exclusively on graduate school itself are generally omitted (exception: Berdahl and Malloy, for its framing of the whole thing as part of your career). There are great ones in this category, including Jessica McCrory Calarco’s A Field Guide to Grad School , Malika Grayson’s Hooded: A Black Girl’s Guide to the Ph.D. , Robert L. Peters’s Getting What You Came For and Adam Ruben’s Surviving Your Stupid, Stupid Decision to go to Grad School . See also Gavin Brown’s How to Get Your PhD: A Handbook for the Journey , which features an essay by me! Similarly, books that focus on academic careers (once you’ve got one) aren’t included (example: Timothy M. Sibbald and Victoria Handford, eds., The Academic Gateway ), nor are books that focus on navigating a career beyond the ivory tower. There are lots of books about academic writing and publishing, conducting and producing research, doing a dissertation, and related stuff. These aren’t included either.

Something missing? I occasionally update this list, so let me know what you think I should add or change.

Books for PhDs

This list is in alphabetical order by author’s last name. Some of these books are inexpensive; others are not. Most should be available via your university or local library, or even from your institution’s career services centre.

Fawzi Abou-Chahine, A Jobseeker’s Diary: Unlocking Employment Secrets (2021).

The short guide is directly aimed at PhDs, especially folks from STEM disciplines. Folks in the UK seeking roles in the private sector will certainly benefit from this book.

Susan Basalla and Maggie Debelius, “ So What Are You Going to Do with That?” Finding Careers Outside Academia (3rd ed., 2014)

The best guide to figuring out your life post-PhD written by two humanities doctorates who’ve been there, done that. Includes many profiles of fellow (former) academics who’ve transitioned to careers beyond the tenure-track.

Loleen Berdahl and Jonathan Mallow, Work Your Career: Get What You Want from Your Social Sciences or Humanities PhD (2018).

I loved the authors’ emphasis on getting clear about what you want, and the advice to reflect at each stage of the graduate school process whether continuing on is the right one. It is refreshing to read a book on graduate school that neither presumes academia is the desired career outcome nor implies it ought to be. Instead, the authors encourage readers to keep their options open and rightly point out the benefits of varied work experience, training, and professionalism to careers within and beyond the Ivory Tower.

Natalia Bielczyk, What Is Out There for Me? The Landscape of Post-PhD Career Tracks (2nd ed., 2020).

A Europe-based computational scientist turned entrepreneur, Dr. Bielczyk offers an important perspective on PhD careers, one explicitly aimed at STEM folks. The book benefits from Bileczyk’s personal experiences, extensive research — including interviews with dozens of PhDs — and includes lots of specific advice and suggestions. You can subscribe to her YouTube channel and interact with her on social media.

Jenny Blake, Pivot: The Only Move That Matters Is Your Next One (2017)

From the description: “ What’s next? is a question we all have to ask and answer more frequently in an economy where the average job tenure is only four years, roles change constantly even within that time, and smart, motivated people find themselves hitting professional plateaus. But how do you evaluate options and move forward without getting stuck?”

Richard N. Bolles with Katharine Brooks, What Color is Your Parachute? 2021 : Your Guide to a Lifetime of Meaningful Work and Career Success (50th anniv. ed, 2020)

If you read only one book on how to get a job and change careers, make it this one. Bolles has an idiosyncratic writing style but his advice is spot-on. Read my review of the 2019 version here .

The 2021 edition was thoroughly updated by Katharine Brooks, EdD, who is the author of You Majored in What? (below). Great choice! An excellent way to bring a classic up to date, and at a time when good advice and guidance is particularly needed.

William Bridges, Transitions: Making Sense of Life’s Changes (40th anniv. ed., 2019)

Think you’re taking too long figuring out what’s next? You aren’t! In the pre-modern world, the transition—a psychological process as opposed to simply a change—was understood as a crucial part of life; not so nowadays. But to successfully navigate a transition, an individual has to experience an end, go through a period of nothingness or neutrality, and finally make a new beginning. No part of the process can be skipped or sped through. There are no shortcuts. (Bridges can relate to being post-PhD or on the alt-ac track: He’s got an ivy league PhD and was an English professor until going through an important transition of his own.)

Katharine Brooks, You Majored in What? Designing Your Path from College to Career (updated, 2017)

Dr. Brooks is a long-time career educator who (as of 2020) directs the career center at Vanderbilt University. This book is aimed at a broader audience of students, but don’t let that dissuade you from checking it out. Starting from the assumption that there are plenty of useful clues in what you’ve done and who you are, and filled with great exercises to help you parse them out, the book will take you through the career exploration process and set you up for a successful job search that is based on a sound understanding of what you want to do and how to make a strong case to employers.

Bill Burnett and Dave Evans, Designing Your Life: How to Build a Well-lived, Joyful Life (2016)

From the description: “In this book, Bill Burnett and Dave Evans show us how design thinking can help us create a life that is both meaningful and fulfilling, regardless of who or where we are, what we do or have done for a living, or how young or old we are. The same design thinking responsible for amazing technology, products, and spaces can be used to design and build your career and your life, a life of fulfillment and joy, constantly creative and productive, one that always holds the possibility of surprise.”

Christopher L. Caterine, Leaving Academia: A Practical Guide (2020)

Just published. Dr. Caterine is a classics PhD who transitioned into a career in strategic corporate communications. One thing that’s cool about this book is just that: He’s working in the private sector. Humanities PhDs are much less commonly found in the business world compared to academics with other backgrounds, and I think that’s a shame. Chris shows us it’s possible and how you can do it too. (But it’s fine if you’re looking elsewhere.)

Christopher Cornthwaite, Doctoring: Building a Life With a PhD (2020)

Dr. Cornthwaite is the Canadian religious studies PhD behind the blog and online community called Roostervane . He shares his story in hopes of inspiring those struggling to move forward with hope and strategies to build a career. Check out the online community too, useful for folks searching for non-academic positions as well as individuals launching side hustles or businesses as consultants of various kinds.

Leon F. Garcia Corona and Kathleen Wiens, eds., Voices of the Field: Pathways in Public Ethnomusicology (2021)

A friend of mine contributed a chapter to this. From the description: “These essays capture years of experience of fourteen scholars who have simultaneously navigated the worlds within and outside of academia, sharing valuable lessons often missing in ethnomusicological training. Power and organizational structures, marketing, content management and production are among the themes explored as an extension and re-evaluation of what constitutes the field of/in ethnomusicology. Many of the authors in this volume share how to successfully acquire funding for a project, while others illustrate how to navigate non-academic workplaces, and yet others share perspectives on reconciling business-like mindsets with humanistic goals.”

M.P. Fedunkiw, A Degree in Futility (2014)

I started to read this novel one day and just couldn’t stop until I finished. So many feelings! The main character defends her dissertation (history of science, U of T) at the beginning of the book, and the story ends a few years later. Fedunkiw has drawn on her own post-PhD experiences to write this wonderful book about a group of three friends navigating life, love, and work in and out of academia. Do read it.

Joseph Fruscione and Kelly J. Baker, eds., Succeeding Outside the Academy: Career Paths beyond the Humanities, Social Sciences, and STEM (2018)

Edited volume of contributions, primarily from women in humanities and social science fields. From the description: “Their accounts afford readers a firsthand view of what it takes to transition from professor to professional. They also give plenty of practical advice, along with hard-won insights into what making a move beyond the academy might entail—emotionally, intellectually, and, not least, financially. Imparting what they wish they’d known during their PhDs, these writers aim to spare those who follow in their uncertain footsteps. Together their essays point the way out of the ‘tenure track or bust’ mindset and toward a world of different but no less rewarding possibilities.”

Patrick Gallagher and Ashleigh Gallagher, The Portable PhD: Taking Your Psychology Career Beyond Academia (2020)

From the description: “Each chapter in this book offers tips and key terms for navigating various kinds of employment, as well as simple action steps for communicating your talents to hiring managers. Your ability to conduct research, to understand statistics and perform data analysis, and to perform technical or scientific writing are all highly valuable skills, as are the insights into human nature you’ve gained from your psychology studies, and your ability to think innovatively and work cooperatively in a variety of contexts.”

David M. Giltner, Turning Science into Things People Need (2017)

From the description: “In this book, ten respected scientists who have built successful careers in industry reveal new insights into how they made the transition from research scientist to industrial scientist or successful entrepreneur, serving as a guide to other scientists seeking to pursue a similar path. From the student preparing to transition into work in industry, to the scientist who is already working for a company, this book will show you how to sell your strengths and lead confidently.”

Alyssa Harad, Coming to My Senses: A Story of Perfume, Pleasure, and an Unlikely Bride (2012).

An English PhDs lovely memoir of discovering the wonders of perfume and embracing who she really is. A story of how one intellectual got back in touch with her feelings, a crucial step on the road to post-PhD happiness and fulfillment. Read an excerpt over at the Chronicle .

Leanne M. Horinko, Jordan M. Reed, James M. Van Wyck, The Reimagined PhD: Navigating 21st Century Humanities Education (2021).

This text appeals to both individual PhDs and graduate students figuring out their own pathway forward and faculty members and other university staff working to improve programs and professional development offerings at their campuses. I’m glad to see it out! (I was at the 2016 conference that inspired this book.)

Hillary Hutchinson and Mary Beth Averill, Scaling the Ivory Tower: Your Academic Job Search Workbook (2019)

Two long-time academic coaches wrote this fantastic guide and workbook for the academic job market. They take you step-by-step through the process of understanding how hiring works — and how it works differently for specific types of positions and kinds of institutions, getting sorted for your search, where to find job ads and other crucial information, staying organized, creating all your materials, prepping for interviews, and other considerations. The book also takes a clear-eyed view of academia and it’s challenges for job seekers, both in the US and around the world. This book is an essential companion to your academic job search. Buying the e-book version? Download and print the worksheets here .

Natalie Jackson, ed., Non-Academic Careers for Quantitative Social Scientists: A Practical Guide to Maximizing Your Skills and Opportunitie s (2023).

If you’re at an institution, check to see if you have free access to this ebook via Springer.

Kaaren Janssen and Richard Sever, eds., Career Options for Biomedical Scientists (2014).

From the description: “This book plugs the gap by providing information about a wide variety of different careers that individuals with a PhD in the life sciences can pursue. Covering everything from science writing and grant administration to patent law and management consultancy, the book includes firsthand accounts of what the jobs are like, the skills required, and advice on how to get a foot in the door. It will be a valuable resource for all life scientists considering their career options and laboratory heads who want to give career advice to their students and postdocs.”

Karen Kelsky, The Professor Is In: The Essential Guide to Turning Your Ph.D. Into A Job (2015)

Dr. Kelsky is dedicated to telling the truth about the academic job market. This book expands on and collects in one place her huge archive of advice and information for PhDs — particularly those aiming for tenure-track positions at US universities. There is advice and resources for “leaving the cult” (part X), a section heading that gives you a sense of where she’s coming from! Academic is its own beast, and its idiosyncracies and unwritten, untold norms and rules belie claims of meritocracy. If you’re going to aim for a tenure-track position, make sure you know what you’re going into and how to increase your chances of success where positions are scarce.

Peggy Klaus, Brag: The Art of Tooting Your Own Horn without Blowing It (2004)

In my experience, PhDs are excellent at not tooting their own horns, for lots of reasons, good and less-good. Here’s how you can talk about yourself appropriately in hopes of moving forward in your career. Great book.

Kathryn E. Linder, Kevin Kelly, and Thomas J. Tobin, Going Alt-Ac: A Guide to Alternative Academic Careers (2020).

If you’re doing or have a doctorate and want to be meaningfully employed in or around higher education, you must read this book – and do what it says. It’s full of clear, practical advice and example jobs where PhDs excel. I was impressed with the depth of knowledge and wide-ranging, thoughtful advice presented, useful for career explorers and seasoned professionals both (and everyone in between). It it’s been a while since you’ve taken a long, hard look at your professional situation, this book will help you revisit your goals and provide smart strategies to move your career forward in just the right way for you.

Kathleen Miller et al. (eds), Moving On: Essays on the Aftermath of Leaving Academia (2014)

Featuring an essay by your truly and many other contributions. By the women behind the now-defunct site How to Leave Academia.

Rachel Neff, Chasing Chickens: When Life after Higher Education Doesn’t Go the Way You Planned (2019)

From the description: “So, you have your PhD, the academic world’s your oyster, but teaching jobs, it turns out, are as rare as pearls. Take it from someone who’s been there: your disappointment, approached from a different angle, becomes opportunity. Marshaling hard-earned wisdom tempered with a gentle wit, Rachel Neff brings her own experiences to bear on the problems facing so many frustrated exiles from the groves of academe: how to turn ‘This wasn’t the plan!’ into ‘Why not?’”

M. R. Nelson, Navigating the Path to Industry: A Hiring Manager’s Advice for Academics Looking for a Job in Industry (2014)

Melanie Nelson’s useful guide is aimed at STEM PhDs who already know where they’re headed. She earned a PhD in the biosciences and has worked as a hiring manager in industry for over a decade.

Rebecca Peabody, The Unruly PhD: Doubts, Detours, Departures, and Other Success Stories (2014)

A collection of first-hand accounts and interviews with people who’ve travelled in, through, and beyond graduate school. Read my review here .

Katie Rose Guest Pryal, The Freelance Academic: Transform Your Creative Life and Career (2019).

Read this book! Katie Pryal provides helpful advice for getting started with the practical stuff, as well as grounding yourself in the reality of the gig economy. It’s particularly good for arts and humanities PhDs and similar academically-focused folks who think business isn’t for them. Take it from Dr. Pryal (and me): You can do this.

Tom Rath, StrengthsFinder 2.0: Discover Your CliftonStrengths (2017)

Take this one out of your local library to read the descriptions and learn about the concept of (work) strengths. If you want to take the assessment, you can purchase the book outright or do that on Gallup’s website . If you’re newer to the world of work beyond the academy, this book and the description of strengths will give you all kinds of useful words and phrases to use to understand what you enjoy, what you bring to a workplace, and effectively communicate all that to potential employers and professional colleagues. Embracing strengths will give you a positive, forward-looking way of approaching career building, and it can change your life for the better.

Katine L. Rogers, Putting the Humanities PhD to Work: Thriving in and beyond the Classroom (2020)

From the introduction: “This book invites readers to consider ways that humanities graduate training can open unexpected doors that lead to meaningful careers with significant public impact, while also suggesting that an expanded understanding of scholarly success can foster more equitable and inclusive systems in and around the academy.” Good. Do read this one if you’re currently a student or if your work has anything to do with advising students or creating and maintaining the graduate training ecosystem within and beyond institutions.

Martin E. P. Seligman, Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being (2011)

An update to his bestselling book Authentic Happiness (also worth reading), this introduced me to the concept of PERMA: that to flourish in life and work, you need to consider and evaluate how frequently you experience have positive emotions (P), feel engaged (E), have positive relationships (R), feel what you’re doing is meaningful (M), and have a sense of accomplishment (A). This isn’t about careers specifically, but it might help you reframe what counts as success in your work life, and that’s particularly crucial for career changers.

Melanie V. Sinche, Next Gen PhD: A Guide to Career Paths in Science (2016)

From the description: “Next Gen PhD provides a frank and up-to-date assessment of the current career landscape facing science PhDs. Nonfaculty careers once considered Plan B are now preferred by the majority of degree holders, says Melanie Sinche. An upper-level science degree is a prized asset in the eyes of many employers, and a majority of science PhDs build rewarding careers both inside and outside the university. A certified career counselor with extensive experience working with graduate students and postdocs, Sinche offers step-by-step guidance through the career development process: identifying personal strengths and interests, building work experience and effective networks, assembling job applications, and learning tactics for interviewing and negotiating—all the essentials for making a successful career transition.”

Don. J. Snyder, The Cliff Walk: A Memoir of a Job Lost and a Life Found (1998)

A marvelous memoir written by a former tenure-track professor at Colgate University who was suddenly let go. This is the story of his journey through unemployment. You will relate. What’s neat is to look up what he does now — but do read the book before you do! I quote from the book in this post .

Matteo Tardelli, Beyond Academia: Stories and Strategies for PhDs Making the Leap to Industry (2023)

This book takes readers through a 4-step process to reflect on what they want, explore job options, apply for roles, and conduct job interviews and negotiate offers. This is Dr. Tardelli’s second book for PhDs moving to non-academic careers; his first one is partly a memoir about his own journey: The Salmon Leap for PhDs (2020).

Anna Marie Trester, Bringing Linguistics to Work: A Story Listening, Story Finding, and Story Telling Approach to Your Career (2017)

My friend and colleagues Dr. Anna Marie Trester is the expert on careers for linguists, and more broadly is a great resource for thinking creatively and expansively about the value of your social sciences and humanities education to the wider world of work and career development. Check out her website for more offerings, CareerLinguist.com .

Jennifer Brown Urban and Miriam R. Linver, eds., Building a Career Outside Academia: A Guide for Doctoral Students in the Behavioral and Social Sciences (2019)

From the description: “This career guide examines the rewarding opportunities that await social and behavioral science doctorates in nonacademic sectors, including government, consulting, think tanks, for-profit corporations, and nonprofit associations. Chapters offers tips for leveraging support from mentors, conducting job searches, marketing your degree and skill set, networking, and preparing for interviews. This expert guidance will help you decide what career is the best fit for you.”

Julia Miller Vick, Jennifer S. Furlong, and Rosanne Lurie, The Academic Job Search Handbook (5th ed., 2016)

Pick this one up for trustworthy job market advice and info — the first edition was published in 1992! — and the dozens of sample cover letters, CVs, and statements of various kinds. It covers an array of fields, from professionally-oriented doctorates to STEM and humanities. This book is a beast, and might be overwhelming. Tackle it bit by bit and keep it as a reference as you gear up for the job market, prepare and submit applications, and move along the hiring process toward negotiation and acceptance.

Susan Britton Whitcomb, Resume Magic: Trade Secrets of a Professional Resume Writer (4th ed., 2010)

This was the book I found most useful when I was researching how to write a good resume (as opposed to an academic CV).

Tom Bennett Lab

The 7 Books Every PhD Student Should Read

By alex wakeman.

Let’s be honest. If you’re nerdy enough to be doing a PhD, you probably love a good book. Whether you’re looking for entertainment or advice, distraction or comfort, the seven listed here can each, in their own way, help you through your frustrating but uniquely rewarding life of a PhD student.

- Isaac Asimov – I, Robot

“1) A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2) A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3) A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.”

The Three Laws of Robotics. Simple. Elegant. Watertight. What could go wrong? These three, now legendary rules are printed on the first page of ‘I, Robot’ then are immediately followed by a series of masterful short stories in which Asimov dismantles his seemingly perfect creation before your very eyes. With ‘I, Robot’ (and many of his other works) Asimov displays dozens of ways rules can be bent and circumvented. As it turns out, a lot can go wrong.

In some ways, this collection of short stories about misbehaving robots acts as a training manual for one of the most essential skills any PhD student must develop: discerning truth. Has that experiment proved what you think it proves? To what extent does it prove that? Are you sure? You might be convinced, but will everyone else at the conference see it that way? At first glance, Asimov’s Three Laws seem like a pretty good crack at a clear and concise system to prevent anything from quirky, metallic shenanigans to an anti-organic apocalypse. Are you sure about that? Look at them again, have a think, test them as vigorously as you would any real-world proof. Then go and read ‘I, Robot’ and find out how wrong you were.

- Sayaka Murata – Convenience Store Woman

You could probably be doing something better with your life, you know. Most people doing a PhD are a pretty effective combination of intelligent and driven. You almost certainly got a 1 st or a 2:1 in a bachelor’s degree, probably a masters. Someone with this profile could certainly find a career with a starting salary above the RCUK minimum stipend level of £15,285 a year, likely one with a much more concrete future ahead of them as well. For most people it doesn’t make a lot of sense to do a PhD; it’s a huge investment of time and energy directed towards a very specialised end. But there are plenty of good reasons to do one as well and if you’re currently working on a PhD you are probably (I sincerely hope) aware of one of the main ones: it’s fun. It really can be fun, at least for a very peculiar type of person. But, of course, it’s not a particularly normal idea of fun. Most people have had their fill of learning by the end of school, or at most university, and it can sometimes be tough convincing a partner or family member that this genuinely is what you enjoy, despite the dark rings they’ve noticed forming under your eyes.

Keiko would probably understand. She feels a very similar way. Not about PhDs or learning, making novel discoveries, or changing the world for the better; but she does feel a very similar way about her work in a convenience store. She enjoys everything about the convenience store, from the artificial 24/7 light to the starchy slightly ill-fitting uniforms, it provides her with enough money for rent and food and she wants for little else. Murata presents us with a tender and often hilarious portrait of a woman attempting to claim agency over her own, unique way of living, and convince others of the simple joy it brings her. If the average PhD student is twice as strange as your typical person, then as a PhD student you have twice as much reason to follow this proudly comforting story of an atypical person and her atypical interest.

- Viktor Frankl – Man’s Search for Meaning

Suffering is relative. It is certain that I will struggle with my PhD. I am still in the early days of my studies, but I am aware that studying for a PhD is likely going to be the hardest thing I have done with my life so far. In all the interviews I had for various funding schemes and DTPs, not one failed to ask a question that amounted to: “How will you cope?”. But at its worst my PhD still won’t cause me to suffer nearly as much as Viktor Frankl did. Don’t think I’m recommending this book to remind you to ‘count yourself lucky’, or any similar nonsense; Frankl isn’t concerned with pity, or one upping your struggles, he just wants you to feel fulfilled, even in the worst moments when nothing’s going right and you’re starting to doubt if you’re even capable of completing a PhD.

The first half of ‘Man’s Search for Meaning’ is a stark, sometimes unpleasant autobiographical account of Frankl’s time imprisoned in various Nazi concentration camps. But the difficulty of the subject matter is worth it for the fascinatingly unique perspective of the author: Viktor Frankl was one of the 20 th Century’s foremost neurologists. The first-hand experience of one of Europe’s blackest events – viewed through the lens of a Jewish psychiatrist – could quite easily paint a rather bleak and hopeless image of humanity. This, however, is not the case. Instead, Frankl uses the second half of the book to explain in layman’s terms the psychological basis behind his biggest contribution to his field: Logotherapy. Frankl emerges from the immense suffering of the holocaust to clearly and kindly encourage us to find meaning and joy in all parts of life. Far from being a depressing read ‘Man’s Search for Meaning’ is instead likely to leave you feeling inspired, cared for, and capable of getting through whatever nonsensical data, failed experiments, and frustrating failures your PhD might throw at you.

- John Ratey – Spark!

We’ve all had times in our lives when we felt that we couldn’t afford to exercise, when life is just so overwhelmingly occupied, there’s too many important things going on. At some points in your PhD, when you feel too busy to take a break, see friends, or cook a proper dinner, having a go at the ‘Couch to 5k’ certainly doesn’t look like it’ll be getting any of your valuable hours any time soon. But after several decades of researching the human brain, Professor John Ratey is here to argue that you can’t afford not to exercise.

I’m sure it isn’t a great revelation to you that exercise is vital for your physical health, but ‘Spark!’ instead implores us to think of exercise as an essential activity for our brain. With an abundance of examples from modern publications in psychiatry and neuroscience, Ratey explains the effects of regular exercise on the human brain. Better memory, improved problem solving, better pattern recognition, longer periods of focus, reduced procrastination and improved mood; I struggle to believe there’s a single human being who would not benefit from every one of these and the countless other benefits discussed throughout the book. But for PhD students, whose work is especially dependent on the functioning of their brain, the effects are potentially even more transformative. You wouldn’t dream of mistreating the expensive lab microscope. You’d never work with equipment that had been left dysfunctional due to lack of care: why treat your own brain any differently?

- Hermann Hesse – The Glass Bead Game

PhD students are students. Sometimes this is painfully clear, sometimes it is easy to forget. But nevertheless, learning is at the centre of a PhD and learning is a two way-street. There is no learning without teaching, even if the learner and the teacher are the same person. ‘The Glass Bead Game’ is a novel about learning and teaching, it is a realistic portrait of two sides of the same coin, simultaneously superimposed upon one another.

The story takes place in an imaginary European province in which experts, scientists, scholars, and philosophers are allotted unlimited resources and are permitted to follow any interest or whim to their heart’s content. In many ways this place may sound utopian compared to the current state of academia, so ruthless in its limitation of funding, and so stringent in its selection processes. Yet this is not a utopian novel. But neither is it a dystopian one. Hesse somehow manages to create a world that feels genuine and authentic, despite its fantastical premise. Though he uses the extreme concept of a country entirely focused on pedagogy to explore the nature of learning, this extremity never becomes fanciful with regards to the positives and negatives of such a way of living. Rather than leaving the reader with a melancholic longing for a fantasy world where the streets are paved with postdoc positions, the realism of ‘The Glass Bead Game’ is more likely to help you find a balanced appreciation for life in academia, better able to accept it’s many blemishes, and in doing so more able to appreciate it’s many joys.

- Plato – The Last Days of Socrates

A PhD is a doctor of philosophy. As PhD students we are all therefore philosophers-in-training. We are learning how to ask precise questions, and how to answer them in a convincing, conclusive manner. We are learning to fully understand the nature of evidence and proof, to recognise when something is proved and when it is not. The word itself comes from the Greek ‘philos’ (loving) and ‘sophia’ (wisdom), an apt description of anyone willing to spend several years of their life researching one extremely niche topic that few others know or care about.

Although the Classical philosophers arrived long before any concept of scientific method, and they often came to some conclusions that now seem laughable, a small understanding of their world can do a lot for any 21st century philosopher. This book in itself won’t come to any ground breaking conclusions that haven’t been long since disproved, or better communicated, but it’s place in this list is earned as an essential introduction to the history of asking questions. At a time in which more and more people are recoiling from the influence of experts, this story of a man being put on trial for asking too many questions remains as relevant as it was 2,000 years ago. And ultimately, this book would still earn its spot on this list solely as the source of the famous scene in which Socrates insists that the only reason the Oracle named him the wisest of the Greeks, was because he alone amongst the Greeks knows that he knows nothing – a statement that may haunt and comfort any PhD student, depending on the day.

- Walt Whitman – Leaves of Grass

Perhaps you’re wondering how a book of 19 th Century poetry is going to help you be a better PhD student. Unlike the other entries on this list, I will make no claim to its ability to help you think better, nor will it help you ask better questions, nor make you feel more justified in your choice of career path. ‘Leaves of Grass’ will not help you be a better PhD student in any way, because you are not a PhD student, you are a human being, and that’s enough. Not only is that enough, that’s everything. To Walt Whitman there’s nothing more you can be. It is quite easy for your view of the world (and therefore your place in it) to become narrowed. You spend all day working on your PhD. All, or most of your colleagues are doing the same, perhaps many of your friends as well. But your PhD is not your life. The success or failure of your research is not you. The accumulation of three Latin characters at the end of your name is not an indication of value. If you are to read any of the books that I have recommended here make it this one and there will be no problem over the coming years that you will not be prepared for, not because it will guarantee your success, but because it will assure you that whilst there are trees and birds and stars and sunlight there doesn’t need to be anything more – anything else that comes out of each day is a welcome (but unnecessary) add-on. Whatever happens during your PhD, whether your thesis changes the world, or all your plans come to nothing, or you drop out halfway through, or you take ten years to finish. Just be you, be alive, be human, and know that that’s more than enough.

Share this:

Published by Alex Wakeman

View all posts by Alex Wakeman

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Ecologist and environmental social scientist

- Funders and Collaborators

Five tips for starting (and continuing) a PhD

On 4th September 2020

In Advice for other students

Lots of the specific stuff you learn as a PhD student, as well as general approaches to your work, begins with informal advice rather than formal training. I’ve received lots of advice from others during my PhD, since the very early stages of my project. This has helped me both build a PhD project that I’m happy with, and actually enjoy my life while I do my PhD (the two, of course, being closely but not entirely linked!). As it’s the start of the academic year I want to share a few of my own tips along those lines, to help get your PhD off to a good start, and keep it on a trajectory you’re happy with:

1. Keep notes on everything you read

My PhD, like many, kicked off with lots of reading of textbooks and academic papers. My reading has ebbed and flowed, but not really stopped, since then. Reading is a big thing during your PhD. It’s useful to keep track of what you’ve been reading because you won’t remember all of it, but you will want to come back to a lot of it.

My system for keeping notes on my reading is highly unsophisticated, but it works: I have (currently) three Word Documents, called Reading_[insert year here] stored on Dropbox so I can access them anywhere. I’ve got a separate one for each year of my PhD because 1) each document is a bit more manageable than one scary enormous one, and 2) I find it surprisingly easy to remember when-ish I was reading different stuff because my reading has gone through some quite distinct phases (e.g. more stuff relevant to study design early on, more stuff about analysis later) so it seemed like a reasonable and simple way to organise my notes.

The notes I make on what I read vary a lot: at my laziest, I just copy and paste the paper title, first author and abstract into the doc, and I’m done. If I’m feeling enthusiastic, I make more extensive notes on the paper and my thoughts on it, or copy specific sections that are especially interesting or relevant to my work. I make sure that each paper title or reference is formatted as a heading so that I can scan through the document easily, and create a contents page for each document. Now, if I want to find a specific paper or read publications on a particular theme, I can Ctrl+F to find key words in my Reading documents.

2. Read a couple of theses

I’m going to disagree with tip #2 in Five Tips for Starting Your PhD Out Right and say you don’t need to read them cover to cover – I don’t think this is necessary in the early stages in your project, unless you really want to do so, or if you feel that every chapter is highly relevant to your own PhD. But I do think it’s helpful to flick through and see different thesis structures (trends in how to structure a thesis evolve over time, and also vary by subject area, so look at recent graduates in your field for ideas of what’s likely to be appropriate for you).

Theses might also contain some specific content that you didn’t realise you’ll need to add to your own thesis (such as more detailed methodology than you usually see in a published paper) or useful references if the PhD is closely related to your own work. I think it works well to look through the theses of recent graduates in your research group, your supervisor, or others working on similar stuff to you. But you can also search for theses online, for example by using EThOS .

3. Start a Word document called “Thesis”

You can use other people’s theses (see previous tip) as a guide to add appropriate headings and subheadings to this document which will act as your own thesis structure / outline. Okay, I did this in third year, not first year, but I reckon it would have been helpful to start this earlier. Since I started this document, I’ve made good progress on actually organising my thoughts and even writing a few things down. And if you’ve got this document ready from early on in your project, you can populate it with notes and ideas whenever they occur to you at any point during your PhD.

Recently, I’ve been going through my Reading documents (remember tip #1) page by page and copying across notes from papers that I have read (and often forgotten about) into the appropriate sections of my Thesis document. It’s surprising how quickly my rough structure has been populated with ideas and material for literature review and synthesis, and how this has helped me link different ideas together i.e. stuff I read in first year and forgot about, with stuff I’ve been reading recently, with stuff that’s coming out of my own analysis. Actually, now that it’s getting quite full, I’ve split my Thesis doc up so that I’m just working with one document per empirical chapter. In first year, a simple thesis structure in a single document is a good place to start.

4. Think about how to make the flexibility of your PhD (and your control over it) work best for you

This one’s quite big-picture, and I’m kind of cheating the list-of-five by squeezing several tips into one. But I think that the general principle of this tip is important, and can be interpreted in different ways to suit different people: PhDs are often inherently flexible, in how you set your daily, weekly and monthly schedule, and I think that you should make the most of that.

The nature of your PhD flexibility and your control over it depend on the details of your project, how you’re going to be working with your supervisors and institution. But there are usually opportunities for flexibility, even if you have to be in the lab most days. PhD-life-flexibility can be exploited for your professional or personal development, to maximise your productivity, to create opportunities that are fun or useful now, or allow you to flex creative muscles you haven’t had the opportunity to flex before.

Below I list the kinds of things you can think about to best use the flexibility of your PhD. These are all things that can work alongside the core research / write / defend thesis requirements of your PhD, and while you definitely don’t have to make any firm plans on day one, I think that it’s really valuable to think about ideas like this (and any more you have) early in your project. It’s all about what you want to get out of your time whilst doing your PhD , including but not limited to the PhD itself, and how you want to structure that time:

- How do you want to set your daily schedule, where do you want to work? What’s going to be most pleasant and productive for you, and fit in with your home life?

- What things do you want to do outside of your PhD (sports, reading non-PhD-related books, joining local clubs and groups, always protecting weekends off) to actively maintain a healthy work-life balance (which is better for both your wellbeing, and the state of your thesis)?

- Are there times when you’re going to be working extra hard (like fieldwork)? How do you want to balance that with rest and recuperation afterwards (an extended post-fieldwork holiday…?)?

- Do you want to take an interruption from your PhD for an internship or job?

- Do you want to practise writing by starting a blog or try a bit of science journalism ?

- Do you want to get involved with science outreach?

- Do you want to build a professional profile and network by making a website or getting on social media?

- Do you want to teach undergraduates or Masters students?

- What training courses would you like to do (and where do you find out about them)?

- Do you want to try turning one or more of your chapters into academic papers?

5. Talk to people, lots, in both general and specific ways

Starting a PhD can be overwhelming, and knowing where to start, or where to go next, can be really tough. Having conversations with other PhD students about what they are working on, how they are finding their PhD, what kind of training they have received, might point you to interesting new research topics, training opportunities, or just give you a bit of a general feel for what it’s going to be like doing a PhD in your new department. These general conversations are important because they can provide you with nuggets of wisdom you didn’t know you needed and, crucially, help you feel connected to and supported by your colleagues and peers.

Asking your supervisor or others specific questions like are there any academics whose work you recommend I look into? / do you recommend any textbooks on [planning a research project], [planning fieldwork], [fundamentals of landscape ecology], [fundamentals of development research] [insert another topic you’re not sure about yet but want to learn about]? / are there any conferences I should look out for? can give you some useful starting points for directing your own learning in the early stages of your project. So, think specifically about what you need at the start of your PhD, and ask for help with it.

…And one bonus tip: read advice from other (ex-) PhD students

There are similar posts to this one with advice on starting your PhD here , and I particularly like the twenty top tips from Lucy Taylor here . There are actual full guides to PhD life like The A-Z of the PhD Trajectory and The Unwritten Rules of Ph.D. Research which can be very helpful to read through at any stage of your PhD (though I guess you maximise your use of them if you read them early!) and to use as reference books as and when you need them. There are lots of people blogging about their past and present PhD experiences, which can offer great advice and comfort at every stage in your PhD. Personally, I love the Thesis Whisperer and like to check in with it semi-regularly. Reading TW feels a bit like my tip #5: it’s about seeking out help and advice, sometimes when you didn’t even know you needed it.

Practical tips on how to be an interdisciplinary individual

It all depends.

Add Comment →

- Doing an internship during your PhD – Ellie Wood

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

HTML Text Five tips for starting (and continuing) a PhD / Ellie Wood by blogadmin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0

Plain text Five tips for starting (and continuing) a PhD by blogadmin @ is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0

Powered by WordPress & Theme by Anders Norén

Report this page

To report inappropriate content on this page, please use the form below. Upon receiving your report, we will be in touch as per the Take Down Policy of the service.

Please note that personal data collected through this form is used and stored for the purposes of processing this report and communication with you.

If you are unable to report a concern about content via this form please contact the Service Owner .

5 books to help you with your PhD

There’s so many, many books on the market that claim to help you with your PhD – which ones are worth buying? I have been thinking about it this topic for some time, but it’s still hard to decide. So here’s a provisional top 5, based on books I use again and again in my PhD workshops:

I wish I owned the copyright to this one because I am sure they sell a shed load every year. Although it seems to be written for undergraduates, PhD students like it for its straight forward, unfussy style. Just about every aspect of research is covered: from considering your audience to planning and writing a paper (or thesis). The section on asking research questions is an excellent walk through of epistemology: an area many people find conceptually difficult. I find it speaks to both science and non science people, but, like all books I have encountered in the ‘self help’ PhD genre, The Craft of Research does have a bias towards ‘traditional’ forms of research practice. You creative researcher types might like to buy it anyway, if only to help you know what you are departing from.

2. How to write a better thesis by Paul Gruba and David Evans

This was the first book I ever bought on the subject, which probably accounts for my fondness for it. I have recommended it to countless students over the 6 or so years I have been Thesis Whispering, many of whom write to thank me. The appealing thing about this book is that it doesn’t try to do too much. It sticks to the mechanics of writing a basic introduction> literature review> methods> results> conclusion style thesis, but I used it to write a project based creative research thesis when I did my masters and found the advice was still valid. Oh – and the price point is not bad either. If you can only afford one book on the list I would get this one.

3. Helping Doctoral Students to write by Barbara Kamler and Pat Thomson

I won an award for my thesis and this book is why. In Helping doctoral students to write Kamler and Thomson explain the concept of ‘scholarly grammar’, providing plenty of before and after examples which even the grammar disabled like myself can understand. I constantly recommend this book to students, but I find that one has to be at a certain stage in the PhD process to really hear what it has to say. I’m not sure why this is, but if you have been getting frustratingly vague feedback from your supervisors – who are unhappy but can’t quite tell you why – you probably need to read this book. It is written for social science students, so scientists might be put off by the style – but please don’t let that stop you from giving it a go. Physicists and engineers have told me they loved the book too. If you want a bit more of the conceptual basis behind the book, read this earlier post on why a thesis is a bit like an avatar.

4. The unwritten rules of PhD research by Marian Petre and Gordon Rugg

I love this book because it recognises the social complexities of doing a PhD, without ever becoming maudlin. Indeed it’s genuinely funny in parts, which makes it a pleasure to read. The authors are at their best when explaining how academia works, such as the concept of ‘sharks in the water’ (the feeding frenzy sometimes witnessed in presentations when students make a mistake and are jumped on by senior academics) and the typology of supervisors. It’s also one of the better references I have found on writing conference papers.

5. 265 trouble shooting strategies for writing non fiction Barbara Fine Clouse

This book is great because it doesn’t try to teach you how to write – you already know how to do that. What you need more is something to help you tweak your writing and improve it. This book is basically a big list of strategies you might like to try when you are stuck, or bored with the way you are writing. This book is so useful I have literally loved it to death – the spine is hopelessly broken and pages are held in by sticky tape. There are many wonderful tips in here from ‘free writing’ and ‘write it backwards’ ideas, to diagramming methods and analytical tools. Opening it at almost any page will give you an idea of something new to try.

What books would be on your top 5 list and why?

Share this:

The Thesis Whisperer is written by Professor Inger Mewburn, director of researcher development at The Australian National University . New posts on the first Wednesday of the month. Subscribe by email below. Visit the About page to find out more about me, my podcasts and books. I'm on most social media platforms as @thesiswhisperer. The best places to talk to me are LinkedIn , Mastodon and Threads.

- Post (607)

- Page (16)

- Product (6)

- Getting things done (258)

- On Writing (138)

- Miscellany (137)

- Your Career (113)

- You and your supervisor (67)

- Writing (48)

- productivity (23)

- consulting (13)

- TWC (13)

- supervision (12)

- 2024 (5)

- 2023 (12)

- 2022 (11)

- 2021 (15)

- 2020 (22)

Whisper to me....

Enter your email address to get posts by email.

Email Address

Sign me up!

- On the reg: a podcast with @jasondowns

- Thesis Whisperer on Facebook

- Thesis Whisperer on Instagram

- Thesis Whisperer on Soundcloud

- Thesis Whisperer on Youtube

- Thesiswhisperer on Mastodon

- Thesiswhisperer page on LinkedIn

- Thesiswhisperer Podcast

- 12,100,654 hits

Discover more from The Thesis Whisperer

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Shopping Cart

Advanced Search

- Browse Our Shelves

- Best Sellers

- Digital Audiobooks

- Featured Titles

- New This Week

- Staff Recommended

- Suggestions for Kids

- Fiction Suggestions

- Nonfiction Suggestions

- Reading Lists

- Upcoming Events

- Ticketed Events

- Science Book Talks

- Past Events

- Video Archive

- Online Gift Codes

- University Clothing

- Goods & Gifts from Harvard Book Store

- Hours & Directions

- Newsletter Archive

- Frequent Buyer Program

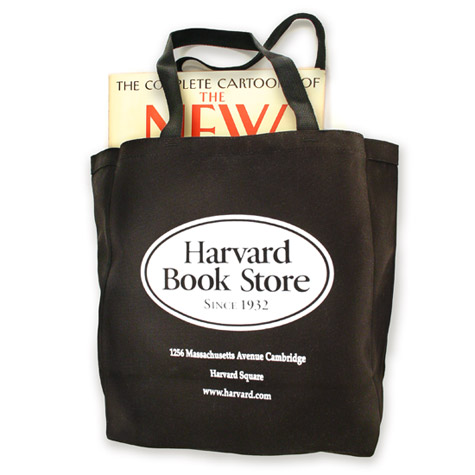

- Signed First Edition Club

- Signed New Voices in Fiction Club

- Off-Site Book Sales

- Corporate & Special Sales

- Print on Demand

- All Our Shelves

- Academic New Arrivals

- New Hardcover - Biography

- New Hardcover - Fiction

- New Hardcover - Nonfiction

- New Titles - Paperback

- African American Studies

- Anthologies

- Anthropology / Archaeology

- Architecture

- Asia & The Pacific

- Astronomy / Geology

- Boston / Cambridge / New England

- Business & Management

- Career Guides

- Child Care / Childbirth / Adoption

- Children's Board Books

- Children's Picture Books

- Children's Activity Books

- Children's Beginning Readers

- Children's Middle Grade

- Children's Gift Books

- Children's Nonfiction

- Children's/Teen Graphic Novels

- Teen Nonfiction

- Young Adult

- Classical Studies

- Cognitive Science / Linguistics

- College Guides

- Cultural & Critical Theory

- Education - Higher Ed

- Environment / Sustainablity

- European History

- Exam Preps / Outlines

- Games & Hobbies

- Gender Studies / Gay & Lesbian

- Gift / Seasonal Books

- Globalization

- Graphic Novels

- Hardcover Classics

- Health / Fitness / Med Ref

- Islamic Studies

- Large Print

- Latin America / Caribbean

- Law & Legal Issues

- Literary Crit & Biography

- Local Economy

- Mathematics

- Media Studies

- Middle East

- Myths / Tales / Legends

- Native American

- Paperback Favorites

- Performing Arts / Acting

- Personal Finance

- Personal Growth

- Photography

- Physics / Chemistry

- Poetry Criticism

- Ref / English Lang Dict & Thes

- Ref / Foreign Lang Dict / Phrase

- Reference - General

- Religion - Christianity

- Religion - Comparative

- Religion - Eastern

- Romance & Erotica

- Science Fiction

- Short Introductions

- Signed Books

- Technology, Culture & Media

- Theology / Religious Studies

- Transition Magazine

- Travel Atlases & Maps

- Travel Lit / Adventure

- Urban Studies

- Wines And Spirits

- Women's Studies

- World History

- Writing Style And Publishing

The Ultimate Guide to Doing a PhD

Have you ever considered doing a PhD, but have no idea where to start? Or are you doing a PhD and feel like you're losing the plot?Deciding to do a PhD is going to be one of the most impactful choices you'll ever make. It's a multi-year commitment that can really shape your career and your life. Yet as important as the PhD is, there's not much collated information about the process as a whole: this is where this book comes in!It explores every aspect of doing a PhD from application to graduation, and the whole mess in between. There are chapters on the motivation to do a PhD, the application process itself, questions around workload, time management, mental health, (peer) pressure, supervisor (mis)communications, teaching, networking, conference attendance, all the way up to publishing your thesis, and preparing for the next steps. And no, the next steps don't necessarily mean continuing to work in academia. This book addresses both career pathways, whether leaving or staying in academia, equally.This book aims to take a PhD student or prospective student by the hand and outline the entire PhD process, answering every question you might possibly have along the way.

There are no customer reviews for this item yet.

Classic Totes

Tote bags and pouches in a variety of styles, sizes, and designs , plus mugs, bookmarks, and more!

Shipping & Pickup

We ship anywhere in the U.S. and orders of $75+ ship free via media mail!

Noteworthy Signed Books: Join the Club!

Join our Signed First Edition Club (or give a gift subscription) for a signed book of great literary merit, delivered to you monthly.

Harvard Square's Independent Bookstore

© 2024 Harvard Book Store All rights reserved

Contact Harvard Book Store 1256 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138

Tel (617) 661-1515 Toll Free (800) 542-READ Email [email protected]

View our current hours »

Join our bookselling team »

We plan to remain closed to the public for two weeks, through Saturday, March 28 While our doors are closed, we plan to staff our phones, email, and harvard.com web order services from 10am to 6pm daily.

Store Hours Monday - Saturday: 9am - 11pm Sunday: 10am - 10pm

Holiday Hours 12/24: 9am - 7pm 12/25: closed 12/31: 9am - 9pm 1/1: 12pm - 11pm All other hours as usual.

Map Find Harvard Book Store »

Online Customer Service Shipping » Online Returns » Privacy Policy »

Harvard University harvard.edu »

- Clubs & Services

- Our Culture

- Open and FAIR Data

- Research projects

- Publications

- Cellular Genomics

- Decoding Biodiversity

- Delivering Sustainable Wheat

- Earlham Biofoundry

- Transformative Genomics

- Scientific Groups Our groups work at the forefront of life science, technology development, and innovation.

- High-Performance Sequencing Dedicated and efficient high-throughput genomics led by experts in sequencing and bioinformatics.

- Single-cell and Spatial Analysis Platforms to support single- or multi-cell analysis, from cell isolation, to library preparation, sequencing and analysis.

- Earlham Biofoundry Providing expertise in synthetic biology approaches and access to laboratory automation

- Tools and resources Explore our software and datasets which enable the bioscience community to do better science.

- Cloud Computing Infrastructure for Data-intensive Bioscience

- Web Hosting for Sites, Tools and Web Services

- Earlham Enterprises Ltd

- Events Calendar Browse through our upcoming and past events.

- About our training High-quality, specialist training and development for the research community.

- Year in industry Supporting undergraduate students to develop skills and experience for future career development.

- Internships and opportunities Opportunities for the next generation of scientists to develop their skills and knowledge in the life sciences.

- Immersive visitors A bespoke, structured training programme, engaging with the faculty, expertise and facilities at the Earlham Institute.

- News Catch up on our latest news and browse the press archive.

- Articles Explore our science and impact around the world through engaging stories.

- Impact Stories Find out how we are contributing to the major challenges of our time.

- Impact Through Policy Advocacy Engaging across the political spectrum to exchange knowledge and inform public policy.

- Public engagement and outreach Communicating our research to inspire and engage learning.

- Communications at EI We work across digital, multimedia, creative design and public relations to communicate our research.

- Our Vision and Mission

- Inclusivity, diversity, equality and accessibility

- Scientific Advisory Board

- Our Management Team

- Operations Division

- Careers overview

- Postgraduate Studies

- Group leaders

- Fellowships

- Life at Earlham Institute

- Living in Norfolk

10 things you need to know before starting a PhD degree

So you want to do a PhD degree, huh? Here we've got everything you need to know about getting started.

So you want to do a PhD degree, huh? Are you sure about that? It’s not going to be an easy decision, so I’ve put together a list of 10 things you need to know before starting a PhD degree. Oh, and don’t panic!

I have recently graduated from the University of Manchester with a PhD in Plant Sciences after four difficult, but enjoyable, years. During those four years, I often felt slightly lost – and there was more than one occasion on which I didn’t even want to imagine writing up my thesis in fear of delving into fits of panic.

On reflection, I realise that – to quote a colleague – commencing my PhD was like “jumping in the deep end with your eyes closed.” If only I’d known to take a deep breath.

1. Are you sure you want to do a PhD degree?

Let’s be under no false impressions, completing a PhD isn’t easy. There will be times when you feel like Wile E Coyote chasing after the Roadrunner – a little bit out of your depth a lot of the time. It’s four years of your life, so make sure it is what you really want to do.

If you want to pursue a career in science, a PhD isn’t always necessary.

It is possible to make great inroads into industry without a doctoral degree. That said, a PhD can also be a very useful qualification with many transferable skills to add to your CV.

By the time you’ll have finished, you can include essentials such as time management, organisational skills, prioritising workloads, attention to detail, writing skills, presenting to an audience – and most importantly – resilience, to name but a few.

2. Choose your project, and supervisor, wisely.

This is very important.

Time after time, our experienced scientists at EI, including Erik Van-Den-Bergh (and I agree) say, “ make sure you’re extremely passionate about exactly that subject. ” When I saw the PhD opening that I eventually was offered, I remember being demonstrably ecstatic about the project before I’d even started it.

I was always interested in calcium signalling and organised a meeting with my potential supervisor immediately, which (to quote Billy Connolly) I leapt into in a mood of gay abandon.

Not only does this help you to keep engaged with your project even through the painstakingly slow times, it also greatly enhances your ability to sell yourself in an interview. If you can show passion and enthusiasm about the project and the science then you’ll be that one step ahead of other candidates – which is all the more important now that many studentships are competitive.

You have to be the best out of many, often exceptional candidates.

However, as important as it is to be passionate about your project, make sure that the person who will be supervising you is worthy.

Does your potential supervisor have a prolific track record of publishing work? What is the community of scientists like in the lab you may be working in? Are there experienced post-doctoral scientists working in the lab? Who will your advisor be? Is your supervisor an expert in the field you are interested in? Is the work you will be doing ground-breaking and novel, or is it quite niche?

There is nothing more frustrating – and I know many PhD degree students with this problem – than having a supervisor who is rarely there to talk to, shows little interest in your work, and cannot help when you are struggling in the third year of your project and some guidance would be much appreciated.

Personally, and I was very lucky to have this, I think it’s incredibly useful to have two supervisors. My PhD degree was split between the University of Manchester and the Marine Biological Association in Plymouth. Between my supervisors, I had two people with expertise in different fields, who could give me some fantastic advice from different perspectives. This also meant that I had two people to check through my thesis chapters and provide useful comments on my drafts.

Make sure you are passionate about your subject before taking it to PhD level. And by passionate I mean really passionate.

For a start, you will most likely have to write a literature review in your first three months, which if done well will form the main bulk of your thesis introduction and will save you a lot of stress and strain when it comes to writing up.

At the end of your first year, you will have to write a continuation report, which is your proof that you deserve to carry on to the end of your three or four years. This doesn’t leave much time for lab work, which means time management is incredibly important. If you think you’ll be able to swan in at 11 and leave at 3, think again.

Fundamentally, never, ever rest on your laurels! As tempting as it may be to slack-off slightly in the second year of your four year PhD, don’t.

4. Be organised.

This is a no-brainer but still, it’s worth a mention. Take an hour on a Monday morning to come up with a list of short-term and long-term goals. You’ll probably have to present your work at regular lab meetings, so it’s always worth knowing what has to be done (lest you look a pillock in front of the lab when there’s nothing to show for your last two weeks.)

It’s always good to have a timeline of what will be done when. If you have a PCR, maybe you can squeeze in another experiment, read a few papers, start writing the introduction to your thesis, or even start collecting the data you already have into figures.

The more good use you make of your time, the easier it’ll be to finish your PhD in the long run. Plus, it’s lovely to sit back and look at actual graphs, rather than worry about having enough to put into a paper. Once you’ve typed up your data, you’ll realise you’ve done far more than you had anticipated and the next step forward will be entirely more apparent.

5. Embrace change – don’t get bogged down in the details.

Felix Shaw – one of our bioinformatics researchers at EI – put it best when he said, “ it felt like I was running into brick walls all the way through [my PhD]… you’d run into a brick wall, surmount it, only to run straight into another. ”

You’ll find that, often, experiments don’t work. What might seem like a great idea could turn out to be as bad as choosing to bat first on a fresh wicket on the first day of the third Ashes test at Edgbaston. (Yeah, we don't know what that means either - Ed).

Resilience is key while completing your PhD. Be open to change and embrace the chance to experiment in different ways. You might even end up with a thesis chapter including all of your failures, which at the very least is something interesting to discuss during your viva voce .

6. Learn how to build, and use, your network.

As a PhD student, you are a complete novice in the world of science and most things in the lab will be – if not new to you – not exquisitely familiar. This matters not, if you take advantage of the people around you.

Firstly, there are lab technicians and research assistants, who have probably been using the technique you are learning for years and years. They are incredibly experienced at a number of techniques and are often very happy to help show you how things are done.

There are postdocs and other PhD students, too. Not only can they help you with day-to-day experiments, they can offer a unique perspective on how something is done and will probably have a handy back-catalogue of fancy new techniques to try.

There are also a bunch of PIs, not limited to your own, who are great to talk to. These people run labs of their own, have different ideas, and might even give you a job once you’ve completed your PhD.

Don’t limit yourself to the labs directly around you, however. There are a massive number of science conferences going on all around the world. Some of them, such as the Society of Biology Conference, take place every year at a similar time in different locations, attracting many of the leaders in their respective fields.

If you are terrified by the prospect of speaking at a full-blown science conference and having your work questioned by genuine skeptics, there are also many student-led conferences which will help you dangle your fresh toes in the murky waters of presenting your work.

One such conference, the Second Student Bioinformatics Symposium, which took place at Earlham Institute in October 2016, was a great place for candidates to share their projects with peers, who are often much more friendly than veteran researchers with 30 year careers to their name when it comes to the questions at the end of your talk.

Another great reason to attend conferences, of course, is the social-side too – make the most of this. You never know who you might meet and connect with over a few drinks once the talks are over and the party commences.

7. Keep your options open.

You should be aware that for every 200 PhD students, only 7 will get a permanent academic post , so it’s incredibly unlikely that you’ll become a Professor – and even if you make PI, it probably won’t be until your mid-forties.

You may also, despite having commenced along the academic path, decide that actually, working in a lab environment isn’t for you. Most PhD graduates, eventually, will not pursue an academic career, but move on to a wide range of other vocations.

It might be that Science Communication is more up your street. This was certainly the case for me – and I made sure that I took part in as many public engagement events as possible while completing my PhD. Most Universities have an active public engagement profile, while organisations such as STEM can provide you with ample opportunities to interact with schools and the general public.

You might also consider entrepreneurship as a route away from academia, which might still allow you to use your expert scientific knowledge. There are a variety of competitions and workshops available to those with a business mind, a strong example being Biotechnology YES.

I, for example, took part in the Thought for Food Challenge, through which I have been able to attend events around the world and meet a vast array of like-minded individuals. Many of the participants from the challenge have gone on to set up successful businesses and have even found jobs as a result of the competition.

8. Balance.

Remember that you still have a life outside of your PhD degree – and that this can be one of the greatest opportunities to make amazing friends from around the world.

A science institute is usually home to the brightest students from a variety of countries and can provide a chance to experience a delightful range of different people and cultures. Don’t just stick to the people in your lab, go to events for postgraduate students and meet people from all over campus.

There are usually academic happy hours happening on Fridays after work where you can buy cheap beer, or some lucky institutions even have their own bar. At Norwich Research Park, we not only have the Rec Centre, along with bar, swimming pool, calcetto, samba classes, archery, and a range of other activities, but there are also biweekly “Postdoc pub clubs” which are very fun to join on a Tuesday evening.

Maintain your hobbies and keep up with friends outside of your PhD and you’ll probably find it’s not that gruelling a process after all.

Plus, the people you meet and become friends with might be able to help you out – or at least be able to offer a sympathetic shoulder.

9. Practical advice.

If, after reading all of this, you’re still going to march forth and claim your doctorhood, then this section should be rather useful.

Firstly, make sure your data is backed up. It’s amazing how many people don’t do this and you’d be bonkers not to. Keep your work saved on a shared drive, so that if your computer decides to spontaneously combust upon pressing the return key, you won’t have lost all of your precious work – or have to go through every one of your lab books and type it all up again.

Secondly, don’t leave your bag in the pub with your half-written thesis in it. I did this, the bag was fine, I was in a state of terror for at least half an hour before the kind person at Weatherspoons located said bag.

Thirdly, read. Read broadly, read anything and everything that’s closely related to your project – or completely unrelated. It’s sometimes amazing where you might find a stroke of inspiration, a new technique you hadn’t thought of … or even in idea of where you might like to go next.

Finally, ask questions – all of the time. No matter how stupid it might sound in your head, everyone’s probably been asked it before, and if you don’t ask, you don’t get.

You’ll probably look far less stupid if you just ask the person standing next to you how the gradient PCR function works on your thermal cycler rather than standing there randomly prodding buttons and looking flustered, anyway.

10. Savour the positives.

At the end of all of this, it has to be said that doing a PhD is absolutely brilliant. There’s no other time in your life that you’ll be this free to pursue your very own project and work almost completely independently. By the time you come to the end of your PhD, you will be the leading expert in the world on something. A real expert! Until the next PhD student comes along …

Related reading.

A PhD, is it worth it? Just ask our students

The realities of doing a PhD

My advice for PhD students? See what bites

COVID and my PhD: to lockdown and back

How does a PhD work and how to find the right one

Building the confidence to take on a PhD

PhD life, 10 things we learned in our first six months

What’s the third year of a PhD like? Tips for navigating your PhD

PhD by experience

- Scientific Groups

- High-Performance Sequencing

- Single-cell and Spatial Analysis

- Tools and resources

- Events Calendar

- About our training

- Year in industry

- Internships and opportunities

- Immersive visitors

- Impact Stories

- Impact Through Policy Advocacy

- Public engagement and outreach

- Communications at EI

PhD in Clothes

Clothes. Career. Thrifting. Productivity.