- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

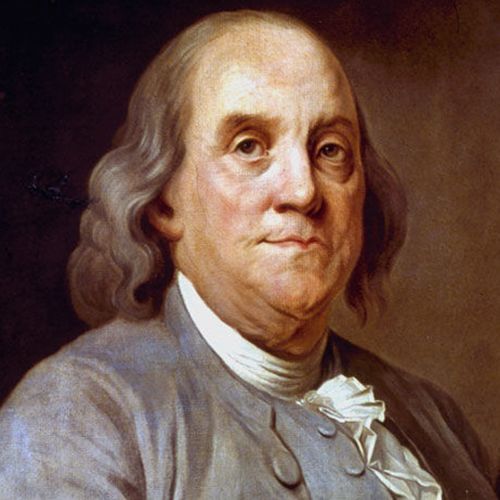

Benjamin Franklin

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 28, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

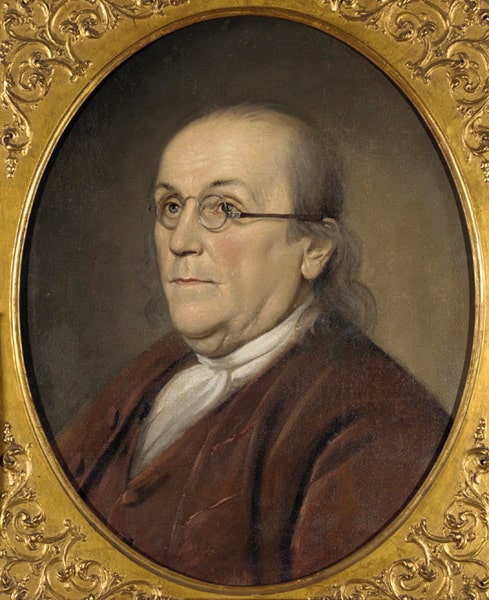

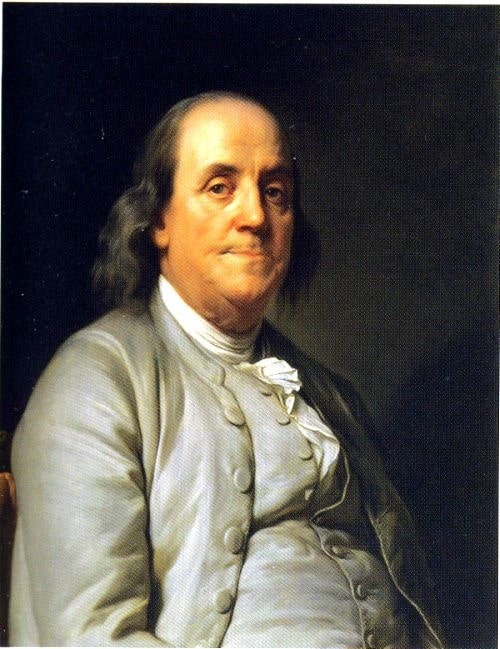

One of the leading figures of early American history, Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) was a statesman, author, publisher, scientist, inventor and diplomat. Born into a Boston family of modest means, Franklin had little formal education. He went on to start a successful printing business in Philadelphia and grew wealthy. Franklin was deeply active in public affairs in his adopted city, where he helped launch a lending library, hospital and college and garnered acclaim for his experiments with electricity, among other projects. During the American Revolution , he served in the Second Continental Congress and helped draft the Declaration of Independence in 1776. He also negotiated the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War (1775-83). In 1787, in his final significant act of public service, he was a delegate to the convention that produced the U.S. Constitution .

Benjamin Franklin’s Early Years

Benjamin Franklin was born on January 17, 1706, in colonial Boston. His father, Josiah Franklin (1657-1745), a native of England, was a candle and soap maker who married twice and had 17 children. Franklin’s mother was Abiah Folger (1667-1752) of Nantucket, Massachusetts , Josiah’s second wife. Franklin was the eighth of Abiah and Josiah’s 10 offspring.

Did you know? Benjamin Franklin is the only Founding Father to have signed all four of the key documents establishing the U.S.: the Declaration of Independence (1776), the Treaty of Alliance with France (1778), the Treaty of Paris establishing peace with Great Britain (1783) and the U.S. Constitution (1787).

Franklin’s formal education was limited and ended when he was 10; however, he was an avid reader and taught himself to become a skilled writer. In 1718, at age 12, he was apprenticed to his older brother James, a Boston printer. By age 16, Franklin was contributing essays (under the pseudonym Silence Dogood) to a newspaper published by his brother. At age 17, Franklin ran away from his apprenticeship to Philadelphia, where he found work as a printer. In late 1724, he traveled to London, England, and again found employment in the printing business.

Benjamin Franklin: Printer and Publisher

Benjamin Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1726, and two years later opened a printing shop. The business became highly successful producing a range of materials, including government pamphlets, books and currency. In 1729, Franklin became the owner and publisher of a colonial newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette , which proved popular—and to which he contributed much of the content, often using pseudonyms. Franklin achieved fame and further financial success with “Poor Richard’s Almanack,” which he published every year from 1733 to 1758. The almanac became known for its witty sayings, which often had to do with the importance of diligence and frugality, such as “Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise.”

In 1730, Franklin began living with Deborah Read (c. 1705-74), the daughter of his former Philadelphia landlady, as his common-law wife. Read’s first husband had abandoned her; however, due to bigamy laws, she and Franklin could not have an official wedding ceremony. Franklin and Read had a son, Francis Folger Franklin (1732-36), who died of smallpox at age 4, and a daughter, Sarah Franklin Bache (1743-1808). Franklin had another son, William Franklin (c. 1730-1813), who was born out of wedlock. William Franklin served as the last colonial governor of New Jersey , from 1763 to 1776, and remained loyal to the British during the American Revolution . He died in exile in England.

Benjamin Franklin and Philadelphia

As Franklin’s printing business prospered, he became increasingly involved in civic affairs. Starting in the 1730s, he helped establish a number of community organizations in Philadelphia, including a lending library (it was founded in 1731, a time when books weren’t widely available in the colonies, and remained the largest U.S. public library until the 1850s), the city’s first fire company , a police patrol and the American Philosophical Society , a group devoted to the sciences and other scholarly pursuits.

Franklin also organized the Pennsylvania militia, raised funds to build a city hospital and spearheaded a program to pave and light city streets. Additionally, Franklin was instrumental in the creation of the Academy of Philadelphia, a college which opened in 1751 and became known as the University of Pennsylvania in 1791.

Franklin also was a key figure in the colonial postal system. In 1737, the British appointed him postmaster of Philadelphia, and he went on to become, in 1753, joint postmaster general for all the American colonies. In this role he instituted various measures to improve mail service; however, the British dismissed him from the job in 1774 because he was deemed too sympathetic to colonial interests. In July 1775, the Continental Congress appointed Franklin the first postmaster general of the United States, giving him authority over all post offices from Massachusetts to Georgia . He held this position until November 1776, when he was succeeded by his son-in-law. (The first U.S. postage stamps, issued on July 1, 1847, featured images of Benjamin Franklin and George Washington .)

Benjamin Franklin's Inventions

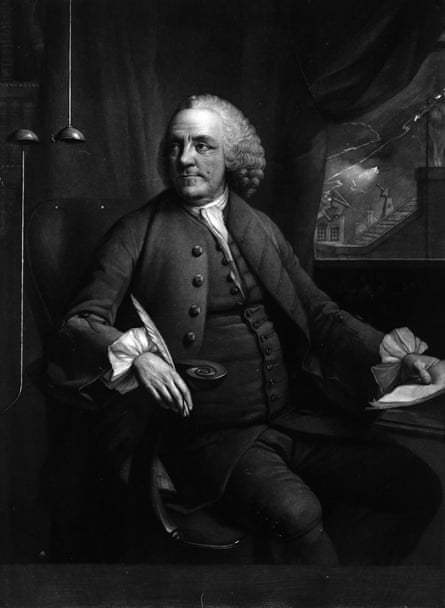

In 1748, Franklin, then 42 years old, had expanded his printing business throughout the colonies and become successful enough to stop working. Retirement allowed him to concentrate on public service and also pursue more fully his longtime interest in science. In the 1740s, he conducted experiments that contributed to the understanding of electricity, and invented the lightning rod, which protected buildings from fires caused by lightning. In 1752, he conducted his famous kite experiment and demonstrated that lightning is electricity. Franklin also coined a number of electricity-related terms, including battery, charge and conductor.

In addition to electricity, Franklin studied a number of other topics, including ocean currents, meteorology, causes of the common cold and refrigeration. He developed the Franklin stove, which provided more heat while using less fuel than other stoves, and bifocal eyeglasses, which allow for distance and reading use. In the early 1760s, Franklin invented a musical instrument called the glass armonica. Composers such as Ludwig Beethoven (1770-1827) and Wolfgang Mozart (1756-91) wrote music for Franklin’s armonica; however, by the early part of the 19th century, the once-popular instrument had largely fallen out of use.

READ MORE: 11 Surprising Facts About Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin and the American Revolution

In 1754, at a meeting of colonial representatives in Albany, New York , Franklin proposed a plan for uniting the colonies under a national congress. Although his Albany Plan was rejected, it helped lay the groundwork for the Articles of Confederation , which became the first constitution of the United States when ratified in 1781.

In 1757, Franklin traveled to London as a representative of the Pennsylvania Assembly, to which he was elected in 1751. Over several years, he worked to settle a tax dispute and other issues involving descendants of William Penn (1644-1718), the owners of the colony of Pennsylvania. After a brief period back in the U.S., Franklin lived primarily in London until 1775. While he was abroad, the British government began, in the mid-1760s, to impose a series of regulatory measures to assert greater control over its American colonies. In 1766, Franklin testified in the British Parliament against the Stamp Act of 1765, which required that all legal documents, newspapers, books, playing cards and other printed materials in the American colonies carry a tax stamp. Although the Stamp Act was repealed in 1766, additional regulatory measures followed, leading to ever-increasing anti-British sentiment and eventual armed uprising in the American colonies .

Franklin returned to Philadelphia in May 1775, shortly after the Revolutionary War (1775-83) had begun, and was selected to serve as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress, America’s governing body at the time. In 1776, he was part of the five-member committee that helped draft the Declaration of Independence , in which the 13 American colonies declared their freedom from British rule. That same year, Congress sent Franklin to France to enlist that nation’s help with the Revolutionary War. In February 1778, the French signed a military alliance with America and went on to provide soldiers, supplies and money that proved critical to America’s victory in the war.

As minister to France starting in 1778, Franklin helped negotiate and draft the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War.

Benjamin Franklin’s Later Years

In 1785, Franklin left France and returned once again to Philadelphia. In 1787, he was a Pennsylvania delegate to the Constitutional Convention. (The 81-year-old Franklin was the convention’s oldest delegate.) At the end of the convention, in September 1787, he urged his fellow delegates to support the heavily debated new document. The U.S. Constitution was ratified by the required nine states in June 1788, and George Washington (1732-99) was inaugurated as America’s first president in April 1789.

Franklin died a year later, at age 84, on April 17, 1790, in Philadelphia. Following a funeral that was attended by an estimated 20,000 people, he was buried in Philadelphia’s Christ Church cemetery. In his will, he left money to Boston and Philadelphia, which was later used to establish a trade school and a science museum and fund scholarships and other community projects.

More than 200 years after his death, Franklin remains one of the most celebrated figures in U.S. history. His image appears on the $100 bill, and towns, schools and businesses across America are named for him.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin is best known as one of the Founding Fathers who never served as president but was a respected inventor, publisher, scientist and diplomat.

Quick Facts

Silence dogood, living in london, wife and children, life in philadelphia, poor richard's almanack, scientist and inventor, electricity, election to the government, stamp act and declaration of independence, life in paris, drafting the u.s. constitution, accomplishments, who was benjamin franklin.

Benjamin Franklin was a Founding Father and a polymath, inventor, scientist, printer, politician, freemason and diplomat. Franklin helped to draft the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution , and he negotiated the 1783 Treaty of Paris ending the Revolutionary War .

His scientific pursuits included investigations into electricity, mathematics and mapmaking. A writer known for his wit and wisdom, Franklin also published Poor Richard’s Almanack , invented bifocal glasses and organized the first successful American lending library.

FULL NAME: Benjamin Franklin BORN: January 17, 1706 DIED: April 17, 1790 BIRTHPLACE: Boston, Massachusetts SPOUSE: Deborah Read (1730-1774) CHILDREN: William, Francis, Sarah ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Capricorn

Franklin was born on January 17, 1706, in Boston, in what was then known as the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Franklin’s father, English-born soap and candlemaker Josiah Franklin, had seven children with first wife, Anne Child, and 10 more with second wife, Abiah Folger. Franklin was his 15th child and youngest son.

Franklin learned to read at an early age, and despite his success at the Boston Latin School, he stopped his formal schooling at 10 to work full-time in his cash-strapped father’s candle and soap shop. Dipping wax and cutting wicks didn’t fire the young boy’s imagination, however.

Perhaps to dissuade him from going to sea as one of his other sons had done, Josiah apprenticed 12-year-old Franklin at the print shop run by his older brother James.

Although James mistreated and frequently beat his younger brother, Franklin learned a great deal about newspaper publishing and adopted a similar brand of subversive politics under the printer’s tutelage.

When James refused to publish any of his brother’s writing, 16-year-old Franklin adopted the pseudonym Mrs. Silence Dogood, and “her” 14 imaginative and witty letters delighted readers of his brother’s newspaper, The New England Courant . James grew angry, however, when he learned that his apprentice had penned the letters.

Tired of his brother’s “harsh and tyrannical” behavior, Franklin fled Boston in 1723 although he had three years remaining on a legally binding contract with his master.

He escaped to New York before settling in Philadelphia and began working with another printer. Philadelphia became his home base for the rest of his life.

Encouraged by Pennsylvania Governor William Keith to set up his own print shop, Franklin left for London in 1724 to purchase supplies from stationers, booksellers and printers. When the teenager arrived in England, however, he felt duped when Keith’s letters of introduction never arrived as promised.

Although forced to find work at London’s print shops, Franklin took full advantage of the city’s pleasures—attending theater performances, mingling with the locals in coffee houses and continuing his lifelong passion for reading.

A self-taught swimmer who crafted his own wooden flippers, Franklin performed long-distance swims on the Thames River. (In 1968, he was inducted as an honorary member of the International Swimming Hall of Fame .)

In 1725 Franklin published his first pamphlet, "A Dissertation upon Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain," which argued that humans lack free will and, thus, are not morally responsible for their actions. (Franklin later repudiated this thought and burned all but one copy of the pamphlet still in his possession.)

In 1723, after Franklin moved from Boston to Philadelphia, he lodged at the home of John Read, where he met and courted his landlord’s daughter Deborah.

After Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1726, he discovered that Deborah had married in the interim, only to be abandoned by her husband just months after the wedding.

The future Founding Father rekindled his romance with Deborah Read and he took her as his common-law wife in 1730. Around that time, Franklin fathered a son, William, out of wedlock who was taken in by the couple. The pair’s first son, Francis, was born in 1732, but he died four years later of smallpox. The couple’s only daughter, Sarah, was born in 1743.

The two times Franklin moved to London, in 1757 and again in 1764, it was without Deborah, who refused to leave Philadelphia. His second stay was the last time the couple saw each other. Franklin would not return home before Deborah passed away in 1774 from a stroke at the age of 66.

In 1762, Franklin’s son William took office as New Jersey’s royal governor, a position his father arranged through his political connections in the British government. Franklin’s later support for the patriot cause put him at odds with his loyalist son. When the New Jersey militia stripped William Franklin of his post as royal governor and imprisoned him in 1776, his father chose not to intercede on his behalf.

After his return to Philadelphia in 1726, Franklin held varied jobs including bookkeeper, shopkeeper and currency cutter. In 1728 he returned to a familiar trade - printing paper currency - in New Jersey before partnering with a friend to open his own print shop in Philadelphia that published government pamphlets and books.

In 1730 Franklin was named the official printer of Pennsylvania. By that time, he had formed the “Junto,” a social and self-improvement study group for young men that met every Friday to debate morality, philosophy and politics.

When Junto members sought to expand their reading choices, Franklin helped to incorporate America’s first subscription library, the Library Company of Philadelphia, in 1731.

In 1729 Franklin published another pamphlet, "A Modest Enquiry into The Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency," which advocated for an increase in the money supply to stimulate the economy.

With the cash Franklin earned from his money-related treatise, he was able to purchase The Pennsylvania Gazette newspaper from a former boss. Under his ownership, the struggling newspaper was transformed into the most widely-read paper in the colonies and became one of the first to turn a profit.

He had less luck in 1732 when he launched the first German-language newspaper in the colonies, the short-lived Philadelphische Zeitung . Nonetheless, Franklin’s prominence and success grew during the 1730s.

Franklin amassed real estate and businesses and organized the volunteer Union Fire Company to counteract dangerous fire hazards in Philadelphia. He joined the Freemasons in 1731 and was eventually elected grand master of the Masons of Pennsylvania.

At the end of 1732, Franklin published the first edition of Poor Richard’s Almanack .

In addition to weather forecasts, astronomical information and poetry, the almanac—which Franklin published for 25 consecutive years—included proverbs and Franklin’s witty maxims such as “Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise” and “He that lies down with dogs, shall rise up with fleas.”

In the 1740s, Franklin expanded into science and entrepreneurship. His 1743 pamphlet "A Proposal for Promoting Useful Knowledge" underscored his interests and served as the founding document of the American Philosophical Society , the first scientific society in the colonies.

By 1748, the 42-year-old Franklin had become one of the richest men in Pennsylvania, and he became a soldier in the Pennsylvania militia. He turned his printing business over to a partner to give himself more time to conduct scientific experiments. He moved into a new house in 1748.

Franklin was a prolific inventor and scientist who was responsible for the following inventions:

- Franklin stove : Franklin’s first invention, created around 1740, provided more heat with less fuel.

- Bifocals : Anyone tired of switching between two pairs of glasses understands why Franklin developed bifocals that could be used for both distance and reading.

- Armonica : Franklin’s inventions took on a musical bent when, in 1761, he commenced development on the armonica, a musical instrument composed of spinning glass bowls on a shaft. Both Ludwig van Beethoven and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed music for the strange instrument.

- Rocking chair

- Flexible catheter

- American penny

Franklin also discovered the Gulf Stream after his return trip across the Atlantic Ocean from London in 1775. He began to speculate about why the westbound trip always took longer, and his measurements of ocean temperatures led to his discovery of the existence of the Gulf Stream. This knowledge served to cut two weeks off the previous sailing time from Europe to North America.

Franklin even devised a new “scheme” for the alphabet that proposed to eliminate the letters C, J, Q, W, X and Y as redundant.

Franklin’s self-education earned him honorary degrees from Harvard , Yale , England’s University of Oxford and the University of St. Andrews in Scotland.

In 1749, Franklin wrote a pamphlet concerning the education of youth in Pennsylvania that resulted in the establishment of the Academy of Philadelphia, now the University of Pennsylvania .

In 1752, Franklin conducted the famous kite-and-key experiment to demonstrate that lightning was electricity and soon after invented the lightning rod.

His investigations into electrical phenomena were compiled into “Experiments and Observations on Electricity,” published in England in 1751. He coined new electricity-related terms that are still part of the lexicon, such as battery, charge, conductor and electrify.

In 1748, Franklin acquired the first of several enslaved people to work in his new home and in the print shop. Franklin’s views on slavery evolved over the following decades to the point that he considered the institution inherently evil, and thus, he freed his enslaved people in the 1760s.

Later in life, he became more vociferous in his opposition to slavery. Franklin served as president of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and wrote many tracts urging the abolition of slavery . In 1790 he petitioned the U.S. Congress to end slavery and the trade.

Franklin became a member of Philadelphia’s city council in 1748 and a justice of the peace the following year. In 1751, he was elected a Philadelphia alderman and a representative to the Pennsylvania Assembly, a position to which he was re-elected annually until 1764. Two years later, he accepted a royal appointment as deputy postmaster general of North America.

When the French and Indian War began in 1754, Franklin called on the colonies to band together for their common defense, which he dramatized in The Pennsylvania Gazette with a cartoon of a snake cut into sections with the caption “Join or Die.”

He represented Pennsylvania at the Albany Congress, which adopted his proposal to create a unified government for the 13 colonies. Franklin’s “Plan of Union,” however, failed to be ratified by the colonies.

In 1757 Franklin was appointed by the Pennsylvania Assembly to serve as the colony’s agent in England. Franklin sailed to London to negotiate a long-standing dispute with the proprietors of the colony, the Penn family, taking William and his two enslaved people but leaving behind Deborah and Sarah.

He spent much of the next two decades in London, where he was drawn to the high society and intellectual salons of the cosmopolitan city.

After Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1762, he toured the colonies to inspect its post offices.

After Franklin lost his seat in the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1764, he returned to London as the colony’s agent. Franklin returned at a tense time in Great Britain’s relations with the American colonies.

The British Parliament ’s passage of the Stamp Act in March 1765 imposed a highly unpopular tax on all printed materials for commercial and legal use in the American colonies. Since Franklin purchased stamps for his printing business and nominated a friend as the Pennsylvania stamp distributor, some colonists thought Franklin implicitly supported the new tax, and rioters in Philadelphia even threatened his house.

Franklin’s passionate denunciation of the tax in testimony before Parliament, however, contributed to the Stamp Act’s repeal in 1766.

Two years later he penned a pamphlet, “Causes of the American Discontents before 1768,” and he soon became an agent for Massachusetts, Georgia and New Jersey as well. Franklin fanned the flames of revolution by sending the private letters of Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson to America.

The letters called for the restriction of the rights of colonists, which caused a firestorm after their publication by Boston newspapers. In the wake of the scandal, Franklin was removed as deputy postmaster general, and he returned to North America in 1775 as a devotee of the patriot cause.

In 1775, Franklin was elected to the Second Continental Congress and appointed the first postmaster general for the colonies. In 1776, he was appointed commissioner to Canada and was one of five men to draft the Declaration of Independence.

After voting for independence in 1776, Franklin was elected commissioner to France, making him essentially the first U.S. ambassador to France. He set sail to negotiate a treaty for the country’s military and financial support.

Much has been made of Franklin’s years in Paris, chiefly his rich romantic life in his nine years abroad after Deborah’s death. At the age of 74, he even proposed marriage to a widow named Madame Helvetius, but she rejected him.

Franklin was embraced in France as much, if not more, for his wit and intellectual standing in the scientific community as for his status as a political appointee from a fledgling country.

His reputation facilitated respect and entrees into closed communities, including the court of King Louis XVI . And it was his adept diplomacy that led to the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which ended the Revolutionary War. After almost a decade in France, Franklin returned to the United States in 1785.

Franklin was elected in 1787 to represent Pennsylvania at the Constitutional Convention , which drafted and ratified the new U.S. Constitution.

The oldest delegate at the age of 81, Franklin initially supported proportional representation in Congress, but he fashioned the Great Compromise that resulted in proportional representation in the House of Representatives and equal representation by state in the Senate . In 1787, he helped found the Society for Political Inquiries, dedicated to improving knowledge of government.

Franklin was never elected president of the United States. However, he played an important role as one of eight Founding Fathers, helping draft the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution.

He also served several roles in the government: He was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly and appointed as the first postmaster general for the colonies as well as diplomat to France. He was a true polymath and entrepreneur, which is no doubt why he is often called the "First American."

Franklin died on April 17, 1790, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, at the home of his daughter, Sarah Bache. He was 84, suffered from gout and had complained of ailments for some time, completing the final codicil to his will a little more than a year and a half prior to his death.

He bequeathed most of his estate to Sarah and very little to his son William, whose opposition to the patriot cause still stung him. He also donated money that funded scholarships, schools and museums in Boston and Philadelphia.

Franklin had actually written his epitaph when he was 22: “The body of B. Franklin, Printer (Like the Cover of an Old Book Its Contents torn Out And Stript of its Lettering and Gilding) Lies Here, Food for Worms. But the Work shall not be Lost; For it will (as he Believ'd) Appear once More In a New and More Elegant Edition Revised and Corrected By the Author.”

In the end, however, the stone on the grave he shared with his wife in the cemetery of Philadelphia’s Christ Church reads simply, “Benjamin and Deborah Franklin 1790.”

The image of Franklin that has come down through history, along with his likeness on the $100 bill, is something of a caricature—a bald man in a frock coat holding a kite string with a key attached. But the scope of things he applied himself to was so broad it seems a shame.

Founding universities and libraries, the post office, shaping the foreign policy of the fledgling United States, helping to draft the Declaration of Independence, publishing newspapers, warming us with the Franklin stove, pioneering advances in science, letting us see with bifocals and lighting our way with electricity—all from a man who never finished school but shaped his life through abundant reading and experience, a strong moral compass and an unflagging commitment to civic duty. Franklin illuminated corners of American life that still have the lingering glow of his attention.

- A house is not a home unless it contains food and fire for the mind as well as the body.

- Do not fear mistakes. You will know failure. Continue to reach out.

- From a child I was fond of reading, and all the little money that came into my hands was ever laid out in books.

- So convenient a thing it is to be a reasonable creature, since it enables one to find or make a reason for everything one has a mind to do.

- In reality, there is, perhaps, no one of our natural passions so hard to subdue as pride. Disguise it, struggle with it, beat it down, stifle it, mortify it as much as one pleases, it is still alive, and will every now and then peep out and show itself; you will see it, perhaps, often in this history; for, even if I could conceive that I had compleatly overcome it, I should probably be proud of my humility.

- Human felicity is produced not so much by great pieces of good fortune that seldom happen, as by little advantages that occur every day.

- There never was a good war or a bad peace.

- In this world nothing is certain but death and taxes.

- Freedom of speech is a principal pillar of a free government; when this support is taken away, the constitution of a free society is dissolved, and tyranny is erected on its ruins.

- He does not possess wealth, it possesses him.

- Experience keeps a dear school, yet fools will learn in no other.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

American Revolutionaries

Cesare Beccaria

Samuel Adams

Andrew Jackson

George Rogers Clark

Roger Sherman

James Monroe

Martha Washington

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $38.71 $ 38 . 71 FREE delivery Monday, May 6 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Hard Working Ants

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Save with Used - Good .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $8.99 $ 8 . 99 FREE delivery Monday, May 6 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Happy-Go-Lucky Thrift

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin Hardcover – September 19, 2000

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Print length 759 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Doubleday

- Publication date September 19, 2000

- Dimensions 6.25 x 1.75 x 9.25 inches

- ISBN-10 0385493282

- ISBN-13 978-0385493284

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may deliver to you quickly

Editorial Reviews

Amazon.com review.

Franklin is best remembered for other things, of course. His still-famous Poor Richard's Almanac helped him secure enough financial freedom as a printer to retire and devote himself to the study of electricity (which began, amusingly, with experiments on chickens). His mind never rested: He invented bifocals, the armonica (a musical instrument made primarily of glass), and, in old age, a mechanical arm that allowed him to reach books stored on high shelves. He served American interests as a diplomat in Europe; without him, France might not have intervened in the American Revolution. He helped draft the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. He possessed a sense of humor, too. In 1776, when John Hancock urged the colonies to "hang together," Franklin is said to have commented, "We must indeed all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately." Franklin's accomplishments were so numerous and varied that they threaten to read like a laundry list. Yet Brands pours them into an engrossing narrative, and they leap to life on these pages as the grand story of an exceptional man. The First American is an altogether excellent biography. --John J. Miller

From Publishers Weekly

From library journal, from the inside flap, from the back cover, about the author, excerpt. © reprinted by permission. all rights reserved., product details.

- Publisher : Doubleday; First Edition (September 19, 2000)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 759 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0385493282

- ISBN-13 : 978-0385493284

- Item Weight : 2.45 pounds

- Dimensions : 6.25 x 1.75 x 9.25 inches

- #125 in U.S. Colonial Period History

- #674 in Political Leader Biographies

- #1,033 in United States Biographies

About the author

H. w. brands.

H.W. Brands taught at Texas A&M University for sixteen years before joining the faculty at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is the Dickson Allen Anderson Centennial Professor of History. His books include Traitor to His Class, Andrew Jackson, The Age of Gold, The First American, and TR. Traitor to His Class and The First American were finalists for the Pulitzer Prize.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Biography of Benjamin Franklin, Printer, Inventor, Statesman

The Image Bank / Getty Images

- Famous Inventors

- Famous Inventions

- Patents & Trademarks

- Invention Timelines

- Computers & The Internet

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

Benjamin Franklin (January 17, 1706–April 17, 1790) was a scientist, publisher, and statesman in colonial North America, where he lacked the cultural and commercial institutions to nourish original ideas. He dedicated himself to creating those institutions and improving everyday life for the widest number of people, making an indelible mark on the emerging nation.

Fast Facts: Benjamin Franklin

- Born : January 17, 1706 in Boston, Massachusetts

- Parents : Josiah Franklin and Abiah Folger

- Died : April 17, 1790 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Education : Two years of formal education

- Published Works : The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard's Almanack

- Spouse : Deborah Read (common law, 1730–1790)

- Children : William (unknown mother, born about 1730–1731), Francis Folger (1732–1734), Sarah Franklin Bache (1743–1808)

Benjamin Franklin was born on January 17, 1706, in Boston, Massachusetts, to Josiah Franklin, a soap and candlemaker, and his second wife Abiah Folger. Josiah Franklin and his first wife Anne Child (m. 1677–1689) immigrated to Boston from Northamptonshire, England in 1682. Anne died in 1689 and, left with seven children, Josiah soon married a prominent colonist named Abiah Folger.

Benjamin was Josiah's and Abiah's eighth child and Josiah's 10th son and 15th child—Josiah would eventually have 17 children. In such a crowded household, there were no luxuries. Benjamin's period of formal schooling was less than two years, after which he was put to work in his father's shop at the age of 10.

Colonial Newspapers

Franklin's fondness for books finally determined his career. His older brother James Franklin (1697–1735) was the editor and printer of the New England Courant , the fourth newspaper published in the colonies. James needed an apprentice, so in 1718 the 13-year-old Benjamin Franklin was bound by law to serve his brother. Soon after, Benjamin began writing articles for this newspaper. When James was put in jail in February 1723 after printing content considered libelous, the newspaper was published under Benjamin Franklin's name.

Escape to Philadelphia

After a month, James Franklin took back the de facto editorship and Benjamin Franklin went back to being a poorly treated apprentice. In September 1723, Benjamin sailed for New York and then Philadelphia, arriving in October 1723.

In Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin found employment with Samuel Keimer, an eccentric printer just beginning a business. He found lodging at the home of John Read, who would become his father-in-law. The young printer soon attracted the notice of Pennsylvania Governor Sir William Keith, who promised to set him up in his own business. For that to happen, however, Benjamin had to go to London to buy a printing press .

London and 'Pleasure and Pain'

Franklin set sail for London in November 1724, engaged to John Read's daughter Deborah (1708–1774). Governor Keith promised to send a letter of credit to London, but when Franklin arrived he discovered that Keith had not sent the letter; Keith, Franklin learned, was known to have been a man who dealt primarily in "expectations." Benjamin Franklin remained in London for nearly two years as he worked for his fare home.

Franklin found employment at the famous printer's shop owned by Samuel Palmer and helped him produce "The Religion of Nature Delineated" by William Wollaston, which argued that the best way to study religion was through science. Inspired, Franklin printed the first of his many pamphlets in 1725, an attack on conservative religion called "A Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain." After a year at Palmer's, Franklin found a better paying job at John Watt's printing house; but in July 1726, he set sail for home with Thomas Denham, a sensible mentor and father figure he had met during his stay in London.

During the 11-week voyage, Franklin wrote "Plan for Future Conduct," the first of his many personal credos describing what lessons he had learned and what he intended to do in the future to avoid pitfalls.

Philadelphia and the Junto Society

After returning to Philadelphia in late 1726, Franklin opened a general store with Thomas Denham and when Denham died in 1727, and Franklin went back to work with the printer Samuel Keimer.

In 1727 he founded the Junto Society, commonly known as the "Leather Apron Club," a small group of middle-class young men who were engaged in business and who met in a local tavern and debated morality, politics, and philosophy. Historian Walter Isaacson described the Junto as a public version of Franklin himself, a "practical, industrious, inquiring, convivial, and middle-brow philosophical [group that] celebrated civic virtue, mutual benefits, the improvement of self and society, and the proposition that hardworking citizens could do well by doing good."

Becoming a Newspaper Man

By 1728, Franklin and another apprentice, Hugh Meredith, set up their own shop with funding from Meredith's father. The son soon sold his share, and Benjamin Franklin was left with his own business at the age of 24. He anonymously printed a pamphlet called "The Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency," which called attention to the need for paper money in Pennsylvania. The effort was a success, and he won the contract to print the money.

In part driven by his competitive streak, Franklin began writing a series of anonymous letters known collectively as the "Busy-Body" essays, signed under several pseudonyms and criticizing the existing newspapers and printers in Philadelphia—including one operated by his old employer Samuel Keimer, called The Universal Instructor in All Arts and Sciences and Pennsylvania Gazette . Keimer went bankrupt in 1729 and sold his 90-subscriber paper to Franklin, who renamed it The Pennsylvania Gazette . The newspaper was later renamed The Saturday Evening Post .

The Gazette printed local news, extracts from the London newspaper Spectator , jokes, verses, humorous attacks on rival Andrew Bradford's American Weekly Mercury , moral essays, elaborate hoaxes, and political satire. Franklin often wrote and printed letters to himself, either to emphasize some truth or to ridicule some mythical but typical reader.

A Common Law Marriage

By 1730, Franklin began looking for a wife. Deborah Read had married during his long stay in London, so Franklin courted a number of girls and even fathered an illegitimate child named William, who was born between April 1730 and April 1731. When Deborah's marriage failed, she and Franklin began living together as a married couple with William in September 1730, an arrangement that protected them from bigamy charges that never materialized.

A Library and 'Poor Richard'

In 1731, Franklin established a subscription library called the Library Company of Philadelphia , in which users would pay dues to borrow books. The first 45 titles purchased included science, history, politics, and reference works. Today, the library has 500,000 books and 160,000 manuscripts and is the oldest cultural institution in the United States.

In 1732, Benjamin Franklin published "Poor Richard's Almanack." Three editions were produced and sold out within a few months. During its 25-year run, the sayings of the publisher Richard Saunders and his wife Bridget—both aliases of Benjamin Franklin—were printed in the almanac. It became a humor classic, one of the earliest in the colonies, and years later the most striking of its sayings were collected and published in a book.

Deborah gave birth to Francis Folger Franklin in 1732. Francis, known as "Franky," died of smallpox at the age of 4 before he could be vaccinated. Franklin, a fierce advocate of smallpox vaccination, had planned to vaccinate the boy but the illness intervened.

Public Service

In 1736, Franklin organized and incorporated the Union Fire Company, based on a similar service established in Boston some years earlier. He became enthralled by the Great Awakening religious revival movement , rushing to the defense of Samuel Hemphill, attending George Whitefield's nightly outdoor revival meetings, and publishing Whitefield's journals between 1739 and 1741 before cooling to the enterprise.

During this period in his life, Franklin also kept a shop in which he sold a variety of goods. Deborah Read was the shopkeeper. He ran a frugal shop, and with all his other activities, Benjamin Franklin's wealth rapidly increased.

American Philosophical Society

About 1743, Franklin moved that the Junto society become intercontinental, and the result was named the American Philosophical Society . Based in Philadelphia, the society had among its members many leading men of scientific attainments or tastes from all over the world. In 1769, Franklin was elected president and served until his death. The first important undertaking was the successful observation of the transit of Venus in 1769; since then, the group has made several important scientific discoveries.

In 1743, Deborah gave birth to their second child Sarah, known as Sally.

An Early 'Retirement'

All of the societies Franklin had created up to this point were noncontroversial, in so far as they kept with the colonial governmental policies. In 1747, however, Franklin proposed the institution of a volunteer Pennsylvania Militia to protect the colony from French and Spanish privateers raiding on the Delaware River. Soon, 10,000 men signed up and formed themselves into more than 100 companies. It was disbanded in 1748, but not before word of what Pennsylvania colony's leader Thomas Penn called "a part little less than treason" was communicated to the British governor.

In 1748 at the age of 42, with a comparatively small family and the frugality of his nature, Franklin was able to retire from active business and devote himself to philosophical and scientific studies.

Franklin the Scientist

Although Franklin had neither formal training nor grounding in math, he now undertook a vast amount of what he called " scientific amusements. " Among his many inventions was the "Pennsylvania fireplace" in 1749, a wood-burning stove that could be built into fireplaces to maximize heat while minimizing smoke and drafts. The Franklin stove was remarkably popular, and Franklin was offered a lucrative patent that he turned down. In his autobiography, Franklin wrote, "As we enjoy great advantages from the inventions of others, we should be glad of an opportunity to serve others by any invention of ours, and this we should do freely and generously." He never patented any of his inventions.

Benjamin Franklin studied many different branches of science. He studied smoky chimneys; he invented bifocal glasses ; he studied the effect of oil upon ruffled water; he identified the "dry bellyache" as lead poisoning; he advocated ventilation in the days when windows were closed tight at night, and with patients at all times; and he investigated fertilizers in agriculture. His scientific observations show that he foresaw some of the great developments of the 19th century.

Electricity

His greatest fame as a scientist was the result of his discoveries in electricity . During a visit to Boston in 1746, he saw some electrical experiments and at once became deeply interested. His friend Peter Collinson of London sent him some of the crude electrical apparatuses of the day, which Franklin used, as well as some equipment he had purchased in Boston. He wrote in a letter to Collinson: "For my own part, I never was before engaged in any study that so engrossed my attention and my time as this has lately done."

Experiments conducted with a small group of friends and described in this correspondence showed the effect of pointed bodies in drawing off electricity. Franklin decided that electricity was not the result of friction, but that the mysterious force was diffused through most substances, and that nature always restored its equilibrium. He developed the theory of positive and negative electricity, or plus and minus electrification.

Franklin carried on experiments with the Leyden jar, made an electrical battery, killed a fowl and roasted it upon a spit turned by electricity, sent a current through water to ignite alcohol, ignited gunpowder, and charged glasses of wine so that the drinkers received shocks.

More importantly, he began to develop the theory of the identity of lightning and electricity and the possibility of protecting buildings with iron rods. He brought electricity into his house using an iron rod, and he concluded, after studying electricity's effect on bells, that clouds were generally negatively electrified. In June 1752, Franklin performed his famous kite experiment, drawing down electricity from the clouds and charging a Leyden jar from the key at the end of the string.

Peter Collinson gathered Benjamin Franklin's letters together and had them published in a pamphlet in England, which attracted wide attention. The Royal Society elected Franklin a member and awarded him the Copley medal with a complimentary address in 1753.

Education and the Making of a Rebel

In 1749, Franklin proposed an academy of education for the youth of Pennsylvania. It would be different from the existing institutions ( Harvard , Yale , Princeton , William & Mary) in that it would be neither religiously affiliated nor reserved for the elites. The focus, he wrote, was to be on practical instruction: writing, arithmetic, accounting, oratory, history, and business skills. It opened in 1751 as the first nonsectarian college in America, and by 1791 it became known as the University of Pennsylvania .

Franklin also raised money for a hospital and began arguing against British restraint of manufacturing in America. He wrestled with the idea of enslavement, personally enslaving and then selling an African American couple in 1751, and then keeping an enslaved person as a servant on occasion later in life. But in his writings, he attacked the practice on economic grounds and helped establish schools for Black children in Philadelphia in the late 1750s. Later, he became an ardent and active abolitionist.

Political Career Begins

In 1751, Franklin took a seat on the Pennsylvania Assembly, where he (literally) cleaned up the streets in Philadelphia by establishing street sweepers, installing street lamps, and paving.

In 1753, he was appointed one of three commissioners to the Carlisle Conference, a congregation of Native American leaders at Albany, New York, intended to secure the allegiance of the Delaware Indians to the British. More than 100 members of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora) attended; the Iroquois leader Scaroyady proposed a peace plan, which was dismissed almost entirely, and the upshot was that the Delaware Indians fought on the side of the French in the final struggles of the French and Indian War.

While in Albany, the colonies' delegates had a second agenda, at Franklin's instigation: to appoint a committee to "prepare and receive plans or schemes for the union of the colonies." They would create a national congress of representatives from each colony, who would be led by a "president general" appointed by the king. Despite some opposition, the measure known as the "Albany Plan" passed, but it was rejected by all of the colonial assemblies as usurping too much of their power and by London as giving too much power to voters and setting a path toward union.

When Franklin returned to Philadelphia, he discovered the British government had finally given him the job he had been lobbying for: deputy postmaster for the colonies.

Post Office

As deputy postmaster, Franklin visited nearly all the post offices in the colonies and introduced many improvements into the service. He established new postal routes and shortened others. Postal carriers now could deliver newspapers, and the mail service between New York and Philadelphia was increased to three deliveries a week in summer and one in winter.

Franklin set milestones at fixed distances along the main post road that ran from northern New England to Savannah, Georgia, to enable the postmasters to compute postage. Crossroads connected some of the larger communities away from the seacoast with the main road, but when Benjamin Franklin died, after also serving as postmaster general of the United States, there were still only 75 post offices in the entire country.

Defense Funding

Raising funds for the defense was always a grave problem in the colonies because the assemblies controlled the purse-strings and released them with a grudging hand. When the British sent General Edward Braddock to defend the colonies in the French and Indian war, Franklin personally guaranteed that the required funds from the Pennsylvania farmers would be repaid.

The assembly refused to raise a tax on the British peers who owned much of the land in Pennsylvania (the "Proprietary Faction") in order to pay those farmers for their contribution, and Franklin was outraged. In general, Franklin opposed Parliament levying taxes on the colonies—no taxation without representation—but he used all his influence to bring the Quaker Assembly to vote for money for the defense of the colony.

In January 1757, the Assembly sent Franklin to London to lobby the Proprietary faction to be more accommodating to the Assembly and, failing that, to bring the issue to the British government.

Franklin reached London in July 1757, and from that time on his life was to be closely linked with Europe. He returned to America six years later and made a trip of 1,600 miles to inspect postal affairs, but in 1764 he was again sent to England to renew the petition for a royal government for Pennsylvania, which had not yet been granted. In 1765, that petition was made obsolete by the Stamp Act, and Franklin became the representative of the American colonies against King George III and Parliament.

Benjamin Franklin did his best to avert the conflict that would become the American Revolution. He made many friends in England, wrote pamphlets and articles, told comical stories and fables where they might do some good, and constantly strove to enlighten the ruling class of England upon conditions and sentiment in the colonies. His appearance before the House of Commons in February 1766 hastened the repeal of the Stamp Act . Benjamin Franklin remained in England for nine more years, but his efforts to reconcile the conflicting claims of Parliament and the colonies were of no avail. He sailed for home in early 1775.

During Franklin's 18-month stay in America, he sat in the Continental Congress and was a member of the most important committees; submitted a plan for a union of the colonies; served as postmaster general and as chairman of the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety; visited George Washington at Cambridge; went to Montreal to do what he could for the cause of independence in Canada; presided over the convention that framed a constitution for Pennsylvania; and was a member of the committee appointed to draft the Declaration of Independence and of the committee sent on the futile mission to New York to discuss terms of peace with Lord Howe.

Treaty With France

In September 1776, the 70-year-old Benjamin Franklin was appointed envoy to France and sailed soon afterward. The French ministers were not at first willing to make a treaty of alliance, but under Franklin's influence they lent money to the struggling colonies. Congress sought to finance the war with paper currency and by borrowing rather than by taxation. The legislators sent bill after bill to Franklin, who continually appealed to the French government. He fitted out privateers and negotiated with the British concerning prisoners. At length, he won from France recognition of the United States and then the Treaty of Alliance .

The U.S. Constitution

Congress permitted Franklin to return home in 1785, and when he arrived he was pushed to keep working. He was elected president of the Council of Pennsylvania and was twice reelected despite his protests. He was sent to the 1787 Constitutional Convention, which resulted in the creation of the Constitution of the United States . He seldom spoke at the event but was always to the point when he did, and all of his suggestions for the Constitution were followed.

America's most famous citizen lived until near the end of the first year of President George Washington's administration. On April 17, 1790, Benjamin Franklin died at his home in Philadelphia at age 84.

- Clark, Ronald W. "Benjamin Franklin: A Biography." New York: Random House, 1983.

- Fleming, Thomas (ed.). "Benjamin Franklin: A Biography in His Own Words." New York: Harper and Row, 1972.

- Franklin, Benjamin. "The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin." Harvard Classics. New York: P.F. Collier & Son, 1909.

- Isaacson, Walter. "Benjamin Franklin: An American Life." New York, Simon and Schuster, 2003.

- Lepore, Jill. "Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin." Boston: Vintage Books, 2013.

- American History Timeline: 1726 to 1750

- History of the United States Postal Service

- The Pennsylvania Colony: A Quaker Experiment in America

- American History Timeline - 1701 - 1725

- Thomas Paine, Political Activist and Voice of the American Revolution

- Inventions and Scientific Achievements of Benjamin Franklin

- Continental Congress: History, Significance, and Purpose

- Brief History of the Declaration of Independence

- Committees of Correspondence: Definition and History

- The Albany Plan of Union

- Major Events That Led to the American Revolution

- Benjamin Franklin Printables

- Samuel Morse and the Invention of the Telegraph

- Biography of Benjamin Banneker, Author and Naturalist

- American Revolution: General Sir Henry Clinton

- American Revolution: Boston Tea Party

This site uses cookies to improve user experience. By continuing to browse, you accept the use of cookies and other technologies.

9 Books About Benjamin Franklin, “The First American”

Read up on the man who defined the American ethos.

- Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Diplomat. Scientist. Writer. Philosopher. Founding Father of the United States. The man who flew a kite and a key in a storm and discovered electricity. Benjamin Franklin’s fascinating and eventful life makes for enthralling reading, especially in our own politically turbulent, rapidly changing times. It’s understandable that readers would seek out material on a figure who served as a force of change in his own times. But where does one start?

Related: The History of Freemasonry, a Fraternal Organization Fraught with Conspiracy Theories

There is an abundance of biographies available on Franklin and the accomplishments and controversies that made up his 84 years. Below are nine remarkable and highly recommended biographies written by trustworthy historians. With unique styles and approaches to 18th-century American politics and scientific advancements, each author can sign their name to their work as proudly as Franklin signed his to the 1776 Declaration of Independence.

The Life of Benjamin Franklin, Volume 1

By J.A. Leo Lemay

The sheer size of the volumes from Lemay’s series may seem daunting at first, but if you're seeking out a richly detailed and thorough biography, this is the one for you. The three volumes divide Benjamin Franklin’s life into the following time categories: 1706-1730, 1730-1747, and 1748-1757. Each volume specifically focuses on a role Franklin played in his lifetime, with the first being his work as a journalist, the second being his life as a printer and publisher of monumental works, and the third being his triple-act as a solider, scientist, and politician (the job titles he is most famous for). It's up to you to decide which of Franklin’s illustrious careers you would like to commit your attention to.

Dust off exclusive book deals and tales from the past when you join The Archive 's newsletter.

Benjamin Franklin: An American Life

By Walter Isaacson

This lengthy biography was produced by a professor of history and seasoned biographer of other innovators, including Leonardo da Vinci , Albert Einstein , and Steve Jobs. Isaacson’s approach to Franklin’s life is that of a biographer who appreciates and admires geniuses.

This biography explores the broader spectrum of Franklin’s scientific and governmental achievements, from his discovery of electricity to his establishment of local lending libraries to his project of redesigning kitchen stoves so they wouldn’t smoke so much. Isaacson presents Franklin as a full enterprising spirit and human being, just as he does with his other subjects.

Related: You Know the Founding Fathers, Now Meet the Founding Mothers

Young Benjamin Franklin: The Birth of Ingenuity

By Nick Bunker

This biography is an ideal choice for readers and researchers who are looking for the psychological elements that shaped Franklin into a Founding Father. It was written by a Pulitzer Prize finalist who tackles his subject matter with intensity and insight.

This biography, as the title suggests, focuses primarily on young Franklin’s struggles to navigate through the brutal worlds of imperialist England and colonial-age America, which was not so much an idealistic promised land as raw material to be molded and reshaped by strong-willed individuals with big ideas. The book ends when Franklin is age 41 and is in the process of discovering electricity.

Benjamin Franklin in London

By George Goodwin

From 1724-1726 Franklin was a printer’s apprentice in London, and from 1757-1775 he called Britain’s capital his home yet again. It was in London during this second stretch where he would defend American interests and socialize with some of the era’s great minds, such as Enlightenment philosopher David Hume and physician and inventor Erasmus Darwin. This biography explores Franklin’s inner tug-of-war and how he teetered between his identity as an Anglophile and his role as an American representative. Goodwin’s work is an interesting journey through Franklin’s divided locations and principles.

Related: 14 Little-Known Facts About America's Founding Fathers

The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin

By H.W. Brands

This biography was a Pulitzer Prize finalist, written by a well-respected professor of history. Its wealth of source material includes Franklin’s letters and correspondence, some of which has never been published before. Like Lemay’s work, this book is profound and accurate, leading readers by the hand through Franklin’s journey from obscurity to notoriety. Unlike some of the others included on this list, the book doesn’t focus on one particular aspect of Franklin’s life, but on his status as a Renaissance man of his time, who thrived in science, publishing, travel, the military, and politics alike.

By Thomas Fleming

Thomas Fleming presents Franklin as a man of courage and innovation during a time when society was undergoing a dramatic transition into modernity and industrialization. This book particularly finds its grounding in Franklin’s political and scientific breakthroughs, such as his discovery of electricity and his part in America’s road to independence. As an ambassador he was also essential in the process of maintaining shaky relationships with the British Empire and the rest of Europe during these tempestuous times. This book is about a man brave enough to face the wrath of kings and diplomats as well as the wrath of the natural world.

Related: 9 Fascinating Books About the Founding Fathers of America

A Little Revenge: Benjamin Franklin and His Son

By Willard Sterne Randall

What is a historical figure’s life without a bit of family drama? In the spirit of American freedom and a break from age-old traditions, Franklin entered into a common-law marriage with a woman named Deborah Read and also conducted love affairs on the side. One of these affairs produced his illegitimate son William Franklin, whose animosity with his father is the center of this account.

Though Franklin had hoped, and almost expected, that William would follow in his footsteps and fight for American independence, William stayed rigidly loyal to the British crown, leading to imprisonment, exile, and a soured, never-resolved relationship between father and son. This book is a good choice for readers interested in the more scandalous side of Franklin’s personal life.

Benjamin Franklin: The Religious Life of a Founding Father

By Thomas S. Kidd

With Franklin’s public and historic image being that of a man of science, his religious faith, or lack thereof, is an aspect of his life that is often overlooked. This account tackles the subject head-on. Relying on Franklin’s letters, essays, and other personal writings, the book explores Franklin’s relationships with devout family members and acquaintances whose influence partially bound him to his strict Puritan upbringing, even as he was embracing Revolutionary ideas and upheavals.

Throughout his life, Franklin’s faith swayed, and he tended to lean towards skepticism and deism, meaning that he believed it was humans, not God, who influenced and manipulated events on Earth. It was this philosophy that likely allowed him the brashness to fly a kite in a storm.

Related: 6 Historical Political Cartoons That Capture the Hopes and Fears of the Past

The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

By Benjamin Franklin

And finally, here is a version of events “straight from the horse’s mouth,” as the English idiom goes. Written during the author-politician’s retirement years, between 1771 and 1790 (the year of his death), this is a first-person retelling of a most extraordinary life. Franklin leads his readers from his sheltered upbringing in Boston to his ardent participation in the American Revolution. Franklin uses his autobiography as a platform for penning his own wisdom and advice for leading a productive and virtuous life, as he abhorred idleness and complacency above anything else. Though the shortest book on the list, it nevertheless has had the longest and largest impact on American history.

Get historic book deals and news delivered to your inbox

Benjamin Franklin’s Inventions

Benjamin franklin was many things in his lifetime: a printer, a postmaster, an ambassador, an author, a scientist, and a founding father. above all, he was an inventor, creating solutions to common problems, innovating new technology, and even making life a little more musical..

Despite creating some of the most successful and popular inventions of the modern world, Franklin never patented a single one, believing that they should be shared freely:

"That as we enjoy great Advantages from the Inventions of others, we should be glad of an Opportunity to serve others by any Invention of ours; and this we should do freely and generously."

Here are some of Benjamin Franklin’s most significant inventions:

Lightning rod.

Franklin is known for his experiments with electricity - most notably the kite experiment - a fascination that began in earnest after he accidentally shocked himself in 1746. By 1749, he had turned his attention to the possibility of protecting buildings—and the people inside—from lightning strikes. Having noticed that a sharp iron needle conducted electricity away from a charged metal sphere, he theorized that such a design could be useful:

"May not the knowledge of this power of points be of use to mankind, in preserving houses, churches, ships, etc., from the stroke of lightning, by directing us to fix, on the highest parts of those edifices, upright rods of iron made sharp as a needle...Would not these pointed rods probably draw the electrical fire silently out of a cloud before it came nigh enough to strike, and thereby secure us from that most sudden and terrible mischief!"

Franklin’s pointed lightning rod design proved effective and soon topped buildings throughout the Colonies. Learn more about the lightning rod .

Like most of us, Franklin found that his eyesight was getting worse as he got older, and he grew both near-sighted and far-sighted. Tired of switching between two pairs of eyeglasses, he invented “double spectacles,” or what we now call bifocals. He had the lenses from his two pairs of glasses - one for reading and one for distance - sliced in half horizontally and then remade into a single pair, with the lens for distance at the top and the one for reading at the bottom.

An avid swimmer, Franklin was just 11 years old when he invented swimming fins—two oval pieces of wood that, when grasped in the hands, provided extra thrust through the water. He also tried out fins for his feet, but they weren’t as effective. He wrote about his childhood invention in an essay titled “On the Art of Swimming”:

“When I was a boy, I made two oval [palettes] each about 10 inches long and six broad, with a hole for the thumb in order to retain it fast in the palm of my hand. They much resembled a painter’s [palettes]. In swimming, I pushed the edges of these forward and I struck the water with their flat surfaces as I drew them back. I remember I swam faster by means of these [palettes], but they fatigued my wrists.”

Franklin Stove

The Franklin Stove.

In 1742, Franklin—perhaps fed up with the cold Pennsylvania winters—invented a better way to heat rooms. The Franklin stove, as it came to be called, was a metal-lined fireplace designed to stand a few inches away from the chimney. A hollow baffle at the rear let the heat from the fire mix with the air more quickly, and an inverted siphon helped to extract more heat. His invention also produced less smoke than a traditional fireplace, making it that much more desirable.

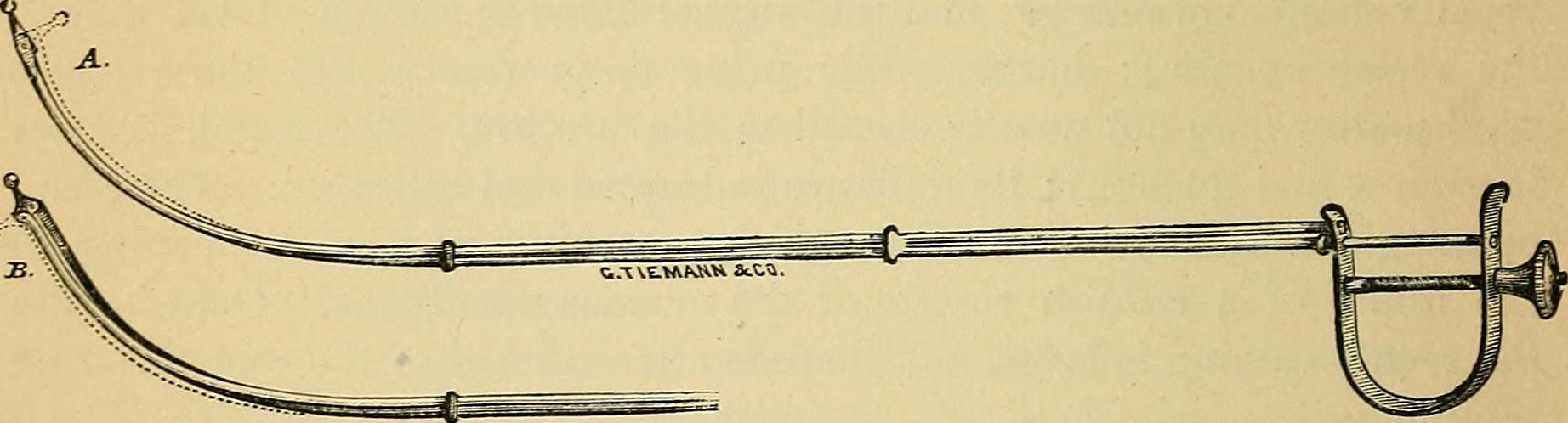

Urinary Catheter

Franklin was inspired to invent a better catheter in 1752 when he saw what his kidney (or bladder) stone-stricken brother had to go through. Catheters at the time were simply rigid metal tubes—none too pleasant. So Franklin devised a better solution: a flexible catheter made of hinged segments of tubes. He had a silversmith make his design and he promptly mailed it off to his brother with instructions and best wishes.

"Of all my inventions, the glass armonica has given me the greatest personal satisfaction."

So wrote Franklin about the musical instrument he designed in 1761. Inspired by English musicians who created sounds by passing their fingers around the brims of glasses filled with water, Franklin worked with a glassblower to re-create the music (“incomparably sweet beyond those of any other”) in a less cumbersome way.

The armonica (the name is derived from the Italian for “harmony”) was immediately popular, but by the 1820s it had been nearly forgotten. Get the full story here .

- Buy Tickets

- TFI Transformation

- Getting Here

- Accessibility

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Daily Schedule

- Where to Eat & Stay

- All Exhibits & Experiences

- The Art of the Brick

- Wondrous Space

- Science After Hours

- Events Calendar

- Staff Scientists

- Benjamin Franklin Resources

- Scientific Journals of The Franklin Institute

- Professional Development

- The Current: Blog

- About Awards

- Ceremony & Dinner

- Sponsorship

- The Class of 2024

- Call for Nominations

- Committee on Science & The Arts

- Next Generation Science Standards

- Title I Schools

- Neuroscience & Society Curriculum

- STEM Scholars

- GSK Science in the Summer™

- Missions2Mars Program

- Children's Vaccine Education Program

- Franklin @ Home

- The Curious Cosmos with Derrick Pitts Podcast

- So Curious! Podcast

- A Practical Guide to the Cosmos

- Archives & Oddities

- Ingenious: The Evolution of Innovation

- The Road to 2050

- Science Stories

- Spark of Science

- That's B.S. (Bad Science)

- Group Visits

- Plan an Event

Everything you've ever wanted to know about the American Revolution

Benjamin Franklin Biography & Facts

About the author.

Edward A. St. Germain created AmericanRevolution.org in 1996. He was an avid historian with a keen interest in the Revolutionary War and American culture and society in the 18th century. On this website, he created and collated a huge collection of articles, images, and other media pertaining to the American Revolution. Edward was also a Vietnam veteran, and his investigative skills led to a career as a private detective in later life.

Quick facts

- Born: 17 January 1706 in Boston, Massachusetts.

- Though associated with Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin was born and raised in Boston. He did not arrive in Philadelphia until he was 17 (6-Oct-1723).

- In addition, Franklin also spent some 28 years abroad, in England and France, at various times throughout his life.

- Deborah Read, his future wife, saw him on the first day he arrived in Philadelphia with a roll of bread “under each Arm, and the eating of the other [third one].” They did not marry until 7 years later (1-Sep-1730).

- Poor Richard’s Almanack, published each year from 1732 to 1757, made Franklin a very wealthy man. He himself estimated (in his Autobiography ) that it sold “annually near ten Thousand” copies.

- Besides his printing business, Franklin was also postmaster of Pennsylvania beginning in 1737. In 1753, he became one of two deputy postmasters of North America, a post he held for 20 years.

- By retiring from the printing business in 1748 (in a lucrative arrangement with his foreman), Franklin had the leisure time to study, experiment, and invent. His subsequent work and publications on electricity made him the most famous man in the North American colonies and a celebrity in Europe.

- Franklin was always a “civic organizer” — initiating street paving, lamp lighting, firefighting, book-lending, and more — and was involved in elective politics from 1751 onward. So his involvement in the American Revolution was natural, but not inevitable. But for events, he may have chosen to stay in England, which is where he was from 1764 to 1775.

- Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1775, was elected to the Second Continental Congress , made small corrections to The Declaration of Independence, signed it, and in December 1776 was sent to France as U.S. Commissioner to plead the American cause. He stayed there throughout the war, extracting much-needed money and supplies from the French, despite little American success on the battlefield.

- Franklin owned two slaves, George and King, who worked as his personal servants.

- Died: 17 April 1790 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- Buried at Christ Church Burial Ground, Philadelphia.

Introduction

Benjamin Franklin, American diplomat, statesman, and scientist, was born in a house on Milk Street — opposite the Old South Church — in Boston, Massachusetts in 1706. He was the tenth son of Josiah Franklin, and the eighth child and youngest son of ten children borne by Abiah Folger, his father’s second wife. Born at Ecton in Northamptonshire, England, the elder Franklin’s strongly Protestant family can be traced back nearly four centuries. He had married young and migrated from Banbury to Boston in 1685.

The autodidact

Benjamin Franklin could not remember when he did not know how to read. At eight years old he was sent to Boston Grammar School, destined by his father for the church as a “tithe” of his sons. But it was not to be. He spent a year there and then a year in a school for writing and arithmetic. When he was ten, he was removed from school to assist his father in his business of tallow chandler (candle maker) and soap boiler. In his 13th year he was apprenticed to his half-brother James, who was establishing himself in the printing business, and who, in 1721. started one of the earliest newspapers in America, the New England Courant.