Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED)

The Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED) has engaged over 50 colleges and schools of education [4] in a critical examination of the doctorate in education through dialog, experimentation, critical feedback and evaluation. The intent of the project is to collaboratively redesign the Ed.D. and to make it a stronger and more relevant degree for the advanced preparation of school practitioners and clinical faculty, academic leaders and professional staff for the nation’s schools and colleges and the learning organizations that support them. More about CPED »

Senior Staff

- Lee S. Shulman, President

- David Imig, Co-Director

- Jill A. Perry, Co-Director

Online Resources

- CPED website

Question: What is the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED)? Does the CPED accredit EdD programs?

Answer: Established in 2007, the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED) is a collection of colleges and schools of education whose faculty meet consistently to discuss, reassess, and improve the structure of the Doctor of Education (EdD) degree. Their membership currently includes over 135 institutions in the United States and Canada, all working together to redesign the EdD to better serve advanced practitioners in the field. The primary goal of CPED is to promote its three-part framework for EdD redesign, which includes “a new definition of the EdD, a set of guiding principles for program development, and a set of design-concepts that serve as program building blocks.” While member schools are expected to adhere to this framework and restructure their EdD programs accordingly, the CPED does not grant any type of accreditation to these institutions or their degree offerings.

The Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate ( CPED ) is comprised of a wide range of postsecondary institutions who are looking to develop and implement changes to their current EdD programs. Working together, these member schools have performed a critical examination of the Doctor of Education degree and created a set of guiding principles intended to refocus the degree on rigorous practitioner preparation. Colleges that join the consortium agree to adopt and institute this framework, making changes to improve their EdD curriculum with support from the CPED community and membership resources, such as collaborative meetings (also known as Convenings ) and access to the peer-reviewed, open source journal, “Impacting Education: Journal for Transforming Professional Practice.”

In our exclusive interview with Dr. Jill Perry , Executive Director of CPED, we discussed the mission and evolution of the CPED. “CPED started in 2007 as a research project among 25 institutions. Really, what that meant was about 50 faculty came together to think it through. We weren’t a formal organization, we didn’t have a coalesced mission early on,” Dr. Perry explained, “As we’ve grown over time, what I’ve observed is that CPED is kind of two things at once–we are a group of institutions, each of which is tackling their Ed.D. program, but as we’ve grown, CPED has become a professional development organization where people collaborate to advance the Ed.D. degree forward.”

Through this combination of discussing innovative ways to improve the EdD, advocating for education practitioners, and designing professional development and networking opportunities for EdD program faculty, CPED takes a multifaceted approach to ensuring the Doctor of Education continues to evolve, expand, and optimally serve the needs of educators and educational leaders.

The CPED Framework for EdD Redesign

In an effort to help improve EdD program content and outcomes, members of CPED developed a framework for EdD redesign that consists of three components. The first is a unified description of the degree that clearly outlines its goal of producing advanced practitioners in the field. According to CPED, “The professional doctorate in education prepares educators for the application of appropriate and specific practices, the generation of new knowledge, and for the stewardship of the profession.” This new definition serves as somewhat of a mission statement for the consortium, summarizing the general consensus of members’ stance on the EdD and serving as the overall objective for program development.

From there, CPED outlined six guiding principles for schools to follow as they reassess and redesign their EdD programs. These guidelines (found on the CPED website) stipulate that the professional doctorate in education:

- Is framed around questions of equity, ethics, and social justice to bring about solutions to complex problems of practice.

- Prepares leaders who can construct and apply knowledge to make a positive difference in the lives of individuals, families, organizations, and communities.

- Provides opportunities for candidates to develop and demonstrate collaboration and communication skills to work with diverse communities and to build partnerships.

- Provides field-based opportunities to analyze programs of practice and use multiple frames to develop meaningful solutions.

- Is grounded in and develops a professional knowledge base that integrates both practical and research knowledge, that links theory with systemic and systematic inquiry.

- Emphasizes the generation, transformation, and use of professional knowledge and practice.

Finally, CPED members developed a set of seven design concepts based around these principles, each representing an integral factor in the preparation of educational leaders. These are fundamental ideas or elements to be used as building blocks when designing or reconstructing a program, as opposed to a rigid or prescriptive model that schools must adhere to, allowing each institution to apply them in a manner that best aligns with their individual program goals. With that in mind, the consortium believes an effective EdD program should be built upon or include the following concepts (which have been paraphrased from the CPED website ):

- Scholarly Practitioners – Professionals who employ practical skills and knowledge to address problems of practice, using practical research and applied theories as tools for change.

- Signature Pedagogy – A pervasive set of practices used to prepare scholarly practitioners to think, perform, and act with integrity, which challenges assumptions, engages in action, and requires ongoing assessment and accountability.

- Inquiry as Practice – The process of posing significant questions that focus on complex problems of practice and the ability to gather and analyze situations, literature, and data with a critical lens.

- Laboratories of Practice – Settings where theory and practice inform and enrich each other, that address complex problems of practice where ideas can be implemented, measured, and analyzed for the impact made.

- Mentoring and Advising – Instructional coaching guided by equity and justice, mutual respect, dynamic learning, cohort and individualized attention, rigorous practices, and integration.

- Problem of Practice – Specific issues embedded in the work of a professional practitioner, the address of which has the potential to result in improved understanding, experience, and outcomes.

- Dissertation in Practice – A scholarly endeavor that impacts a complex problem of practice.

CPED’s Six Values That Reflect the CPED Framework

As CPED has grown, Dr. Perry and her leadership team began to define the organization’s core values and their role in guiding EdD program faculty in their efforts to optimally prepare the next generation of scholarly practitioners. “These values are really reflective of our CPED Framework, which includes our definition of the Ed.D., our six principles that guide program design, and our design concepts that frame the pieces of an Ed.D. program. The values are meant to be shared across both the program and the organization itself,” she noted in her interview. The six values (and how they apply to EdD programs as well as education practitioners in the field) are as follows:

- Diversity : Embracing the value of every learner’s perspectives, and prioritizing the voices and input of diverse communities in improving both CPED and its member schools and partners.

- Learning : Investing in continual improvement and growth, as well as the practical application of new scholarly knowledge about education leadership and addressing barriers to academic equity and success.

- Partnership : Seeking to strengthen partnerships with schools offering EdD programs, as well as with education leaders at public school districts, community colleges, and other organizations that focus on advancing education for diverse learners at all levels.

- People : Prioritizing the lived experiences, needs, concerns, and insights of educational professionals.

- Social Justice : Maintaining ethical, inclusive, and just practices throughout all CPED initiatives, and having an accessibility-focused perspective underpinning all programs, educational media, and collaborative events.

- Students First : Upholding the principle that all education leaders should put their students first, from CPED’s mentorship of EdD faculty, to EdD faculty’s prioritization of their students’ goals and professional development needs, to education practitioners’ support of their students across diverse public and private school settings.

The Impact of CPED on EdD Programs

CPED only accepts non-profit institutions with current accreditation from a U.S. regional accrediting body, who can demonstrate commitment to ongoing enhancement of EdD education and a willingness to implement the CPED Framework in their EdD program. To illustrate the ongoing impact that the CPED has had on EdD programs nationwide, OnlineEdDPrograms.com interviewed the program directors for several EdD programs that are CPED members (you can view CPED-related interviews with program faculty in our Educational and Organizational Leadership Interviews section).

For example, Northeastern University’s Doctor of Education program won the 2022 CPED Program of the Year Award. In an exclusive interview with OnlineEdDPrograms.com, Northeastern’s Assistant Dean of Faculty and Academic Affairs Dr. Sara Ewell explained how, “Having CPED behind us as a standard of excellence within the field really helped establish our work. […] The CPED convenings and subsequent relationships have been really helpful in terms of creating thought partners. I feel like every relationship or conversation that I had at the convening or follow-up was another little nugget of the big picture: […] ‘Wow that’s a really great idea to use that kind of a template to help students organize the literature review’ or ‘That’s really interesting, what you’re doing to ensure that social justice is infused throughout the program.’”

Similarly, in an exclusive interview with Dr. Nancy Hastings , Assistant Dean of the College of Education at the University of West Florida (UWF) and Chair of the Department of Instructional Design and Technology, she explained how her program’s membership with CPED helped them clarify their curricular content and research mentorship and guidance for students. “We are a member of the Carnegie Project for the Education Doctorate, and the resources our membership provides to our faculty and students also make us stand out. The Carnegie Project is all about recognizing that an Ed.D. and a Ph.D. are two very different things, meant for different audiences,” she noted, “An Ed.D. is for the practitioner—the person who is looking to be the leader in their organization. The chief learning officer or performance consultant, those are people who are going to stay in practice.”

Choosing an EdD Program

As mentioned above, CPED does not directly accredit EdD programs, and member schools may be in different phases of implementing the framework and its guidelines. In general, students should choose an EdD that provides the curriculum and structure needed to help them best achieve their academic and career goals, independent of whether the program comes from a CPED member school. With that said, membership is definitely another factor one might consider when researching options for their doctorate.

If students are unclear about how a particular institution has implemented the framework or where they are in the process, it is best to reach out to a school representative for more information. This is a great opportunity to learn how a prospective EdD program has evolved over time and where the school sees that program going in the future. Pursuing an EdD is a significant time and financial commitment; therefore, students should be certain that the program they choose is the ideal match for their personal and professional needs both now and in years to come.

Online EdD Programs offered by Schools that are members of the CPED

The following schools are members of the CPED and offer online EdD programs. The CPED classifies members into three categories based on their phase of program development. These three phases include: Designing and Developing, Implementing, and Experienced. The following schools/programs are currently in one of these three phases.

General Doctorate of Education FAQs

- What is an EdD degree? Is an EdD a terminal degree?

- What is an EdD Dissertation in Practice?

- What is an EdD in organizational leadership?

- What is the difference between an EdD and a PhD in Education?

- What is the difference between an EdD and an EdS degree?

- What is the Difference between an EdD in Nursing Education and a DNP in Nursing Education?

- What is the difference between campus, online, and hybrid EdD programs?

- Search MERLOT Discipline

- MERLOT Discipline Navigation

- Main Navigation

- Join MERLOT/

- Login to MERLOT

- Home

- Research Resources

- Research Databases

- Research Centers

- Dissertation Projects

- Campus Programs

- Carnegie Project

- Course Syllabi

- Community Members

Carnegie Project on the Educational Doctorate (CPED)

Overview and california state university (csu) cped.

The Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED) is a three-year effort sponsored by the Carnegie Foundation and the Council of Academic Deans in Research Education Institutions to strengthen the education doctorate. The participating colleges and universities have committed themselves to working together to undertake a critical examination of the doctorate in education with a particular focus on the highest degree that leads to careers in professional practice. The intent of the project is to redesign and transform doctoral education for the advanced preparation of school practitioners and clinical faculty, academic leaders and professional staff for the nation's schools and colleges and the organizations that support them.

The goal of CPED is to reclaim the education doctorate and to transform it into the degree of choice for the next generation of school and college leaders. The California State University (CSU) has been invited to establish a CSU CPED with the intent of applying the national CPED framework in analyzing its new education doctorate programs.

- The scholarship of teaching and learning

- The identification of "signature pedagogies" well-suited to their programs

- The elements of candidate and program assessment that are central within the education doctorate

- The creation of "laboratories of practice" in which future practitioners experiment and undertake "best evidence analyses"

- New "capstone" experiences in which future practitioners produce outstanding demonstrations of their proficiency

Forthcoming CSU CPED Convening on June 11-12, 2009

Previous CSU CPED Convening on October 20-21, 2008

Previous CSU CPED Convening on January 29-30, 2008

Exploring the CPED Issues

© 2007 California State University Concept and design by CSU Academic Technology Services and the Center for Distributed Learning MERLOT Multimedia Educational Resource for Learning and Online Teaching

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, the carnegie project on the education doctorate: a partnership of universities and schools working to improve the education doctorate and k-20 schools.

University Partnerships for Academic Programs and Professional Development

ISBN : 978-1-78635-300-9 , eISBN : 978-1-78635-299-6

Publication date: 16 August 2016

Since its inception at Harvard in 1921, the Doctorate in Education (EdD) has been a degree fraught with confusion as to its purpose and distinction from the PhD. In response to this, the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED), a collaborative project consisting of 80+ schools of education located in the United States, Canada, and New Zealand were established to undertake a critical examination of the EdD and develop it into the degree of choice for educators who want to generate knowledge and scholarship about practice or related policies and steward the education profession. However, programmatic changes in higher education can bring both benefits and challenges (Levine, 2005). This chapter explains: the origins of the education doctorate; how CPED as a network of partners has changed the EdD; the use of bi-annual Convenings as spaces for this work; CPED’s three phases of membership that have built the network; CPED’s path forward.

- Partnerships

- Collaboration

Perry, J.A. and Zambo, D. (2016), "The Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate: A Partnership of Universities and Schools Working to Improve the Education Doctorate and K-20 Schools", University Partnerships for Academic Programs and Professional Development ( Innovations in Higher Education Teaching and Learning, Vol. 7 ), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Leeds, pp. 267-284. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2055-364120160000007024

Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2016 Emerald Group Publishing Limited

We’re listening — tell us what you think

Something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (2018-present)

CEAC is providing a formative evaluation to understand the current needs and challenges of member institutions. The Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED) operates as a member-driven organization of colleges and schools of education working together through communication and evaluation to the examine the doctorate of education (EdD). The work of CPED is realized in schools and colleges of education across the country and beyond through the application of a “framework for EdD design/redesign” to produce advanced scholarly practitioners across the field of education.

- Our Projects

Connect with Pitt Education

News and Events

The Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED) Joins the School of Education

Left: October 2015 convening at Lynn University as local superintendent tells members about the role of research in practice. Right: CPED's AERA collaborative session.

In fall 2015, the University of Pittsburgh School of Education signed an agreement with the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED) Board of Directors that brought the organization and its executive director to the School of Education. The goal of this partnership is to strengthen the CPED organization with School of Education supports and to advance the Pitt doctorate in education (EdD) as a model for other CPED member schools of education.

The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching established CPED in 2007 in an effort to redesign and transform the education doctorate for the advanced preparation of school practitioners, academic leaders, clinical faculty, and professional staff for the nation’s schools, colleges, and the organizations that support them. Starting with 25 original member institutions, it is now a network of more than 80 colleges and schools of education in the U.S., Canada, and New Zealand, each having committed faculty and resources to work collaboratively to undertake a critical examination of the purpose and design of the doctorate in education.

Every three years or so, CPED invites applications for new schools of education to join. Potential members complete an application process that demonstrates their commitment to improving the EdD both at their institution and through the broader network. The goal of this grassroots, faculty-led effort is to improve the preparation of all educational leaders to ensure they become well-equipped scholarly practitioners who can meet the educational challenges of the 21st century.

To do this, early CPED members worked together at bi-annual convenings to redefine and reshape what professional preparation should look like. Rather than set forth a one-size-fits-all model, members wanted a flexible design that would honor the local context of schools of education. After three years, members developed a framework that includes a set of guiding principles for program design, a set of curricular design concepts, and a new definition of the EdD that strengthens its purpose as a professional degree (further details are available at http://cpedinitiative.org/about ).

Left and middle: CPED learning communities share ways to operationalize the CPED framework. Right: CPED fellow engages members in assessing the impact of EdD graduates.

As new members have entered the project, they utilize this framework to redesign existing EdD degrees or to create new ones. Members are supported by the CPED Web site, which offers resources like curriculum, program design, and dissertation in practice samples. They are also supported at the bi-annual convenings, which are designed as professional development and a critical friends experience for faculty and serve to both advance individual program designs as well as strengthen, improve, support, and promote the CPED framework through continued cooperation and empirical investigation.

The School of Education joined CPED in 2011 and its new EdD was redesigned utilizing the CPED framework. The School of Education EdD serves as a model within CPED of how to collaborate and engage many departments in creating one EdD program with a systems approach to thinking about education. This EdD design and Pitt’s ability to support the continued growth of CPED as a research organization were primary reasons for moving the CPED headquarters to the School of Education. Professor and Renée and Richard Goldman Dean Alan Lesgold enthusiastically welcomed the opportunity to host CPED for the next five years. Because CPED is a 501c3 organization, its activities and administration are self-supportive; however, being headquartered at an academic institution like the University of Pittsburgh provides the kinds of supports and resources that allow CPED to deepen its work on improving the EdD through research and publication.

For example, the School of Education will house the first-ever CPED journal. This new journal, titled Impacting Education: Journal on Transforming Professional Practice , will make its first call for submissions in April 2016. The publication will offer CPED faculty and graduate members and non-members opportunities to share their learning about redesigning EdD programs and the impact of graduates in educational practice. School of Education faculty and students are encouraged to take advantage of this opportunity.

Additionally, on June 12-14, 2017, the University of Pittsburgh will welcome the CPED convening at the University Club, which will include a new wave of CPED members to be recruited in late 2016. Pitt faculty and students will have the opportunity to share the EdD program with current and new CPED members. More information will be available at www.cpedinitiative.org/convenings-events .

In turn, CPED has many resources and opportunities for the University of Pittsburgh School of Education and its education faculty. The CPED leadership team is excited about its new home and looks forward to working together over the coming years.

Programmatic Resources: Faculty members are welcome to utilize the resources on the CPED Web site (email [email protected] to receive a log-in) to support EdD program and curriculum design.

Convenings and Events: CPED hosts bi-annual convenings and member meetings at the American Educational Research Association (AERA), the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE), and the University Council for Educational Administration (UCEA). Pitt education faculty are encouraged to participate in all of these opportunities, as they are a form of professional development that offer a network for learning and sharing ideas about EdD program designs. Upcoming events include:

Meetings on April 8 at the 2016 AERA conference: 9 a.m. member meeting and 2 p.m. co-sponsored panel with Special Interest Groups (SIG) 168 on the future of doctoral preparation in education.

- June 6-8, 2016, in Portland, Ore., and hosted by Portland State University and Washington State University

- October 24-26, 2016, at East Carolina University

- June 12-14, 2017, at University of Pittsburgh

Research and Publishing: In addition to the forthcoming journal, CPED frequently engages member faculty in research and publication opportunities. To learn more, email [email protected] . CPED will also fund a Pitt student as a graduate assistant.

Promotional Resources: As the headquarters for CPED, Pitt has access to CPED promotional materials and labels when recruiting students. In addition, CPED lists Pitt on all of its materials shared internationally.

JILL PERRY is a research associate professor and executive director of the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate.

Doctorate in Education Policy & Leadership (EdD)

You are here: american university school of education admissions doctorate in educational policy and leadership.

- Request Info

Explore More

202-885-8201

Spring Valley , Room 471 on a map

Back to top

Prepare to advance your career and join a network of American University faculty, students, and alumni who are transforming education in the United States.

American University’s School of Education believes education shouldn’t just focus on what students learn—it should provide students with an opportunity to reach their full potential and be a force for positive social change. Education should give students hope. Antiquated policies and structures have made hope hard to find in modern education, and the United States needs a new approach to education leadership and policy to bring hope and action to its schools.

The Online Doctorate in Education Policy and Leadership (EdD) is a response to this need, empowering leaders in education who have the practical experience and theoretical knowledge to effect widespread, progressive change in education. Whether they pursue opportunities in educational instruction, organizational leadership, or policymaking, EdD graduates will be better prepared to change education, for every student.

The Cohort Experience

Peer learning and a sustained learning network are essential hallmarks of the Online EdD program. As a result, students will progress through the program as part of a cohort, taking the same courses, and accomplishing program milestones together. We intentionally build a diverse cohort of students to contribute to the dynamic learning environment in the program. Learning will occur through robust dialogue, shared learning experiences, and presenting current professional work and doctoral research.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take to complete.

Typically the program can be completed in less than three years.

Who is the online EdD in Education Policy and Leadership program intended for?

This program is designed for working PK-12 leaders who want to connect policy to practice and gain the practical knowledge and skills to transform their organizations and education systems.

What are the pillars of this program?

Graduates of the Online EdD program will be equipped with the skills every education leader needs to be effective, including strategic budgeting, collaborative inquiry, talent management, partnership building, learning science, and program evaluation. We strive to hone students’ knowledge and develop their skills and beliefs in the following four domains:

Systems Change

Personal leadership, social justice and antiracism, policy and research.

These domains serve as the backbone of our program and live out in each course, module, and residency experience that our students engage in. After completing their coursework and their Problem of Practice dissertation, students will have the policy, leadership, and research skills necessary to serve in senior positions in school district central offices, independent schools, nonprofit organizations, government agencies, advocacy organizations, and more.

May I continue to work full-time while completing the program?

Full-time work while taking the program is normal. Students will participate in a residency enabling them to interface with peers and faculty, so they need to visit Washington, DC for three (3) required residencies in terms 1, 4, and 6 from Thursdays through Sundays, encapsulated in the EDU-798 course.

When are applications due?

Applications are due each December for placement in the cohort the following fall.

Is this program part of CPED?

The Online EdD program at American University is proudly part of The Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED). The vision of the CPED is to inspire all schools of education to apply the CPED framework to the preparation of educational leaders to become well-equipped scholarly practitioners who provide stewardship of the profession and meet the educational challenges of the 21st century.

Have questions? Send us an email: [email protected] 202-885-3720

Please send me information about Master of Arts in Special Education: Learning Disabilities

It looks like you already used that name and address to request information for one or more AU graduate program(s).

If you have not previously requested AU graduate program information, create a new request

EdD Related News

First Doctoral Cohort of Antiracist Changemakers

Believed to be one of the first of its kind to focus on antiracism, the “practice-oriented” doctoral program ...

2022 EdD Grad Wins Dissertation Award

Dr. Cheyenne E. Batista ’22 was recognized by the Carnegie Project on Education Doctorate (CPED) as the winner of ...

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Examining EdD Dissertations in Practice: The Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate

Related Papers

Kristina A Hesbol , Valerie A Storey

This article examines the evolution of the dissertation in practice: the capstone effort from the doctoral program of the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate consortium. The project represents professional practice programs that endeavor to design and implement al ternative dissertation-in-practice models to the traditional five-chapter re search study. The article assists in the identification of the conditions that facilitate or obstruct the transition toward alternative dissertation models and the impact of the consortium on the researcher-practitioner gap.

Kristina Hesbol , T. Lange

This article examines the evolution of the dissertation in practice: the capstone effort from the doctoral program of the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate consortium. The project represents professional practice programs that endeavor to design and implement alternative dissertation-in-practice models to the traditional five-chapter research study. The article assists in the identification of the conditions that facilitate or obstruct the transition toward alternative dissertation models and the impact of the consortium on the researcher–practitioner gap. In this article, we examine the conditions that can serve to facilitate or obstruct the transition toward alternative dissertation models. They argue that the United States’ current knowledge economy cannot reliably depend on a research model that fails to connect with the practitioner in the field, and they argue for a rigorous model that bridges the CPED consortium’s researcher–practitioner gap and develops meaningful knowledge to inform change.

Impacting Education: Journal on Transforming Professional Practice

Gwynne Rife

The purpose of this study was to learn how education doctorate students create the problems of practice researched in their dissertations, and the potential impact of their research on their local contexts to enhance the generation of knowledge. Three research questions guided this study: 1) How do education doctorate students derive their problems of practice?, 2) What is the nature of the problems of practice that the students have studied?, and 3) What are the reported impacts the study of problems of practice has on doctoral students’ local contexts? To answer these questions, the researchers conducted a document analysis of 19 dissertations. Student dissertations included a diverse set of problems of practice largely determined by their professional roles. The findings indicate a need for further refinement of the concept of a problem of practice and how the education doctorate program and their candidates employ the concept of a problem of practice in their dissertations a...

Valerie A Storey

Two diverse universitiesone large public metropolitan and one small independent participate in the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED) the purpose of which is to clearly distinguish between the Ph. D. and the Ed. D. and their unique intended outcomes. These universities (re)designed and implemented the professional doctorate (Ed. D.) in educational leadership aligned with the CPED concepts. Development processes, experiences in (re)design and implementation, as well as the resulting degree requirements are compared. Signicant changes in student learning experiences, student outcomes, and the capstone experience are commonalities of each university's newly (re)designed Ed. D.

School Leadership Review

Joseph Murphy

Judith Aiken

Change Magazine, 2015. An overview of the project 8 years after its birth.

Kristina Hesbol , Valerie A Storey

This article examines the evolution of the dissertation in practice: the capstone effort from the doctoral program of the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate consortium. The project represents professional practice programs that endeavor to design and implement alternative dissertation-in-practice models to the traditional five-chapter research study. The article assists in the identification of the conditions that facilitate or obstruct the transition toward alternative dissertation models and the impact of the consortium on the researcher–practitioner gap.

RELATED PAPERS

International Sociological Association E-Symposium

Ankur Datta

Calcified Tissue International

Colin Robinson

Physical Review D

Naba Kumar Mondal

PLoS Clinical Trials

Sophie Coeur

ligabaw worku

Acta Scientiae et Technicae

Ronaldo Figueiró

Ida Bagus Irawan Purnama

Journal of Vascular Surgery

Khanh Nguyen

Handbuch Bildungsreform und Reformpädagogik

André Frank Zimpel

Journal of Urology

Laureano Rangel

Journal of Marketing for Higher Education

Marcelo Royo Vela

Frontiers in Physiology

aylin ozge pekel

Frontiers in Sustainable Cities

Manish Jangid

Sociedade e Estado

Manuela Boatcă

The New England Journal of Medicine

Hilary Hatch

ABU HASAN [EL]

Physical Review Materials

Karol Nogajewski

Bilal Hassan

Giuseppe Mele

Weixuan Wang

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Approaching EdD Program Redesign as a Problem of Practice

- Lesley F Leach Tarleton State University

- Juanita M Reyes Tarleton State University

- Credence Baker Tarleton State University

- Ryan Glaman Tarleton State University

- Jordan M Barkley Tarleton State University

- Don M Beach Tarleton State University

- J Russell Higham Tarleton State University

- Kimberly Rynearson Tarleton State University

- Mark Weber Tarleton State University

- Tod Allen Farmer Tarleton State University

- Randall Bowden Tarleton State University

- Jesse Brock Tarleton State University

- Phillis Bunch Tarleton State University

As members of the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED), universities across the United States are restructuring EdD programs to better prepare professional practitioners with the practical skills and theoretical knowledge needed to improve the educational environments that they serve. The hallmark of these programs is often the dissertation in practice, a scholarly investigation within which students define a problem of practice and then systematically test solutions to that problem. In this study, we investigate the experiences of university faculty participating in the redesign of an Educational Leadership EdD program who approach the redesign as a problem of practice. Root causes of identified program issues are presented in addition to the changes implemented in the redesigned program to improve upon the problem of practice.

Archbald, D. (2008). Research versus problem solving for the education leadership doctoral thesis: Implications for form and function. Educational Administration Quarterly, 5(44), 704-739.

Archbald, D. (2014). The GAPPSI Method: Problem-solving, planning, and communicating – concepts and strategies for leadership in education. Ypsilanti, MI: NCPEA Publications.

Barnett, B. G., & Muse, I. D. (1993). Cohort groups in education administration: Promises and challenges. Journal of School Leadership, 3, 400-415.

Browne-Ferrigno, T., & Muth, R. (2003). Effects of cohorts on learners. Journal of School Leadership, 13(6), 621-643.

Burnett, P. C. (1999). The supervision of doctoral dissertations using a collaborative cohort model. Counselor Education and Supervision, 39, 46-52.

Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (n.d.). About Us. Retrieved from http://www.cpedinitiative.org/page/AboutUs

Dorn, S. M., Papalewis, R., & Brown, R. (1995). Educators earning their doctorates: Doctoral student perceptions regarding cohesiveness and persistence. Education, 116, 305-314.

Everson, S. T. (2006). The role of partnerships in the professional doctorate in education: A program application in educational leadership. Educational Considerations, 33(2), 1-15.

Golde, C. M. (2006). Preparing stewards of the discipline. In C. M. Golde, & G. E. Walker (Eds.), Envisioning the future of doctoral education (pp. 3-23). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Harry, M., & Schroeder, R. (2000). Six Sigma: The breakthrough management strategy revolution the world’s top corporations. New York, NY: Currency.

Hoffman, R. L., & Perry, J. A. (2016). In J. A. Perry (Ed.), The EdD and the scholarly practitioner: The CPED path (pp. 13 - 25). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (6th ed.). (2017). Root cause analysis in health care: Tools and techniques. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Author.

LeMahieu, P. G., Nordstrum, L. E., Cudney, E. A. (2017). Six Sigma in education. Quality Assurance in Education, 25(1), 91-108.

Perry, J. A. (2016a). The scholarly practitioner as steward of the practice. In Storey, V. A., and Hesbol, K. A. (Eds.), Contemporary approaches to dissertation development and research methods (1st ed., pp. 300-313). New York, NY: Information Science Reference.

Perry, J. A. (2016b). The new education doctorate: Preparing the transformational leader. In J. A. Perry (Ed.), The EdD and the scholarly practitioner: The CPED path (pp. 1 - 10). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Preuss, P. G. (2003). School leaders’ guide to root cause analysis: Using data to dissolve problems. Larchmont, NY: Eye on Education.

Recker, J., Rosemann, M., Indulska, M., & Green, P. (2009). Business process modeling – A comparative analysis. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 10(4), 333-363.

Rohanna, K. (2017). Breaking the “adopt, attack, abandon” cycle: A case for improvement science in K-12 education. In C. A. Christie, M. Inkelas & S. Lemire (Eds.), Improvement Science in Evaluation: Methods and Uses. New Directions for Evaluation, (153), 65-77.

Shulman, L. S., Golde, C. M., Bueschel, A. C., & Garabedian, K. J. (2006). Reclaiming education’s doctorates: A critique and a proposal. Educational Researcher, 35, 25–32.

Storey, V. A., Caskey, M. M., Hesbol, K. A., Marshall, J. E., Maughan, B., & Dolan, A. W. (2015). Examining EdD dissertations in practice: The Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate. International HETL Review, 5(2). Retrieved from https://www.hetl.org/examining-edd-dissertations-in-practice-the-carnegie-project-on-the-education-doctorate/

(University Name) (n.d.). Mission/Vision/Core Values. Retrieved from https://www.(University Name).edu/strategicplan/2016-2020/mission-vision.html

Williams, P.M. (2001). Techniques for root cause analysis. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, 14(2), 154-157.

Willis, J., Inman, D., & Valenti, R. (2010). Completing a professional practice dissertation: A guide for doctoral students and faculty. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Additional Files

How to cite.

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms:

- The Author retains copyright in the Work, where the term “Work” shall include all digital objects that may result in subsequent electronic publication or distribution.

- Upon acceptance of the Work, the author shall grant to the Publisher the right of first publication of the Work.

- Attribution—other users must attribute the Work in the manner specified by the author as indicated on the journal Web site;

- The Author is able to enter into separate, additional contractual arrangements for the nonexclusive distribution of the journal's published version of the Work (e.g., post it to an institutional repository or publish it in a book), as long as there is provided in the document an acknowledgement of its initial publication in this journal.

- Authors are permitted and encouraged to post online a prepublication manuscript (but not the Publisher’s final formatted PDF version of the Work) in institutional repositories or on their Websites prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work. Any such posting made before acceptance and publication of the Work shall be updated upon publication to include a reference to the Publisher-assigned DOI (Digital Object Identifier) and a link to the online abstract for the final published Work in the Journal.

- Upon Publisher’s request, the Author agrees to furnish promptly to Publisher, at the Author’s own expense, written evidence of the permissions, licenses, and consents for use of third-party material included within the Work, except as determined by Publisher to be covered by the principles of Fair Use.

- the Work is the Author’s original work;

- the Author has not transferred, and will not transfer, exclusive rights in the Work to any third party;

- the Work is not pending review or under consideration by another publisher;

- the Work has not previously been published;

- the Work contains no misrepresentation or infringement of the Work or property of other authors or third parties; and

- the Work contains no libel, invasion of privacy, or other unlawful matter.

- The Author agrees to indemnify and hold Publisher harmless from Author’s breach of the representations and warranties contained in Paragraph 6 above, as well as any claim or proceeding relating to Publisher’s use and publication of any content contained in the Work, including third-party content.

Revised 7/16/2018. Revision Description: Removed outdated link.

Most read articles by the same author(s)

- Lesley F. Leach, Credence Baker, Catherine G. Leamons, Phillis Bunch, Jesse Brock, Using Evidence to Frame Problems of Practice , Impacting Education: Journal on Transforming Professional Practice: Vol. 6 No. 4 (2021)

- William C. Torres, Lesley F. Leach, Ryan Glaman, J. Russell Higham, Learning Beyond the Content , Impacting Education: Journal on Transforming Professional Practice: Vol. 8 No. 3 (2023): Regular Issue

Make a Submission

ISSN 2472-5889 (online)

Examining EdD Dissertations in Practice: The Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate

IHR Note: We are proud to present this second article in the fifth annual volume of the International HETL Review (IHR) with the academic article contributed to the February issue of IHR by Drs. Valerie Storey, Mickey Caskey, Kristina Hesbol, James Marshall, Bryan Maughan and Amy Dolan . In this action research study, the authors, members of the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED) Dissertation in Practice Awards Committee have examined the format and design of dissertations submitted as a part of the reform of the educational doctorate. Twenty-five dissertations submitted as part of this project were examined through surveys, interviews and analysis to determine if the dissertations had changed as a result of the project and re-design with the participating programs. Their results raise questions about distinctiveness of Educational and professional doctorates, as compared to PhDs and the criteria to “demonstrate new knowledge” in the dissertation process.

Valerie A. Storey University of Central Florida, U.S.A.

Micki M. Caskey Portland State University, U.S.A.

Kristina A. Hesbol University of Denver, U.S.A.

James E. Marshall California State University, Fresno, U.S.A.

Bryan Maughan University of Idaho, U.S.A.

Amy Wells Dolan University of Mississippi, U.S.A.

In 2007, 25 colleges and schools of education (Phase I) came together under the aegis of the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED) to transform doctoral education for education practitioners. A challenging aspect of the reform of the educational doctorate is the role and design of the dissertation or Dissertation in Practice. In response to consortium concerns, members of the CPED Dissertation in Practice Awards Committee conducted this action research study to examine the format and design of Dissertations in Practice submitted by (re) designed programs. Data were gathered with an online survey, interviews, analyses of 25 Dissertations in Practice submitted in 2013 to the Committee. Results indicated few changes occurred in the final product, despite evidence of change in the Dissertation in Practice process. Findings contribute to debates about the distinctive nature of EdDs (and of professional doctorates generally) as distinct from PhDs, and how about the key criteria for demonstrating “new knowledge to solve significant problems of practice” are demonstrated through the dissertation submission.

Keywords : Dissertation in Practice, Professional Doctorate, Doctoral Thesis, Education Doctorate

Introduction

During the past decade, epistemological and philosophical debates have surrounded the EdD (Caboni & Proper, 2009; Guthrie, 2009; Shulman 2005, 2007; Zambo, 2011). These debates focus on the source, depth, and type of knowledge doctoral students need to become reflective practitioners and effective school leaders (Andrews & Grogan 2005; Evans 2007; Shulman 2005, 2007; Shulman, Golde, Bueschel, & Garabedian, 2006), and the different roles of the EdD (Doctor of Education) and PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) programs failing in delivering these outcomes (Caboni & Proper, 2009; Guthrie, 2009). Some postulated that the programs were indistinguishable in some higher education institutions (Guthrie, 2009; Shulman 2005, 2007; Shulman et al., 2006). Levine (2005) observed that the EdD lacked its own identity, failing to prepare school leaders who understand real school problems with the ability to take action and make effective, lasting change. Additionally EdD graduates often fail to impact students and teachers in their schools (Murphy & Vriesenga, 2005), declining to turn theory into practice, change practice, or challenge the status quo (Evans, 2007).

In 2007, institutional members of the Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED) came together to re-imagine and redesign the EdD (Perry & Imig, 2008), clearly differentiating the Professional Practice Doctorate (EdD) from the PhD. A major outcome was the culminating EdD experience, validating the scholarly practitioner’s ability to solve Problems of Practice, and demonstrating the doctoral candidate’s ability “to think, to perform, and to act with integrity” (Shulman, 2005, p. 52).

In this article, we first set the study context, illustrating the epistemological and philosophical debates relating to the EdD, focusing on Dissertations in Practice (DiPs). Next, we discuss the developing design of DiPs, reflecting new models of educational research that emerge from Problems of Practice (PoPs). Finally, we report an action research study in which we investigated exemplar DiPs, nominated by 54 Phase I and II institutions, for the annual Dissertation in Practice Award. The purpose of the study was to generate valuable insights about the nature of professional practice doctorate dissertations.

The Association of American Colleges and Universities define the EdD as a terminal degree, presented as an opportunity to prepare for academic, administrative, or specialized positions in education. The degree favorably places graduates for leadership responsibilities or executive-level professional positions across the education industry (National Science Foundation, 2011). At most academic institutions where education doctorates are offered, the college or university chooses to offer an EdD, a PhD, or both (Osguthorpe & Wong, 1993). However, Shulman et al. (2006) contended that EdD and PhD programs are not aligned with their distinct theoretical purposes, and that poorly structured programs, marked by confusion of purpose, caused the EdD to be viewed as “PhD Light,” rather than a separate degree for a separate profession (p. 26).

Expanding Role of Influence

CPED encourages Schools of Education to reclaim the education doctorate (Shulman et al., 2006; Perry & Imig, 2008; Walker, Golde, Jones, Bueschel, & Hutchings, 2008) by developing EdD programs with scholarly practitioner graduates. The program design includes a set of courses, socialization experiences, and emphases that are distinct from those conventionally offered in PhD programs (Caboni & Proper, 2009; Guthrie, 2009). Bi-annual, three-day CPED convenings include graduate students, college deans, clinical faculty, teachers, college professors, and school administrators from member institutions. The first convening in Palo Alto, CA (June 2007), attended by 25 invited institutions, set the tone for future convenings by orchestrating an exchange of information with colleagues, grounded in a spirit of scholarly generosity, ethical responsibility, and integrity.

CPED Institutions, Phase 1, 2007-2010

A second group of institutions responded to a call for CPED membership in 2010. The call, open members of the Council for Academic Deans of Research Education Institutions (CADREI), included institutional commitments outlined in a Memorandum of Understanding. Identified as Phase II institutions, 26 new universities joined the consortium, beginning their work of EdD re-design at the fall convening held at Burlington, Vermont in 2011.

CPED Institutions, Phase II, 2011-2013

An ongoing discussion has centered on the nature of the final capstone of CPED influenced programs which Hamilton et al., (2010) suggest helps invigorate the use of a traditionalacademic tool. Many Phase 1 institutional members are farther into their programmatic implementation, with cohorts who have graduated and completed a DiP. Still, iterative questions abound among CPED institutions regarding the nature, scope, impact, and format of the DiP (Sands et al., 2013), as institutions learn from graduating cohorts (Harris, 2011).

CPED Institutions, Phase III, 2014

In April 2014, the consortium’s membership increased to 84, including two universities from Canada and one from New Zealand.CPED’s commitment to support institutional flexibility in the DiP design presents difficulty sorting out issues of rigor, and advancing common understandings about the nature of problems of practice (Sands et al., 2013). An informal survey of current CPED institutions (CPED, 2013) identified culminating projects including white papers, articles for publication, monographs, electronic portfolios, and the traditional five chapter dissertation document.

Not surprisingly, the consortium has struggled to reach consensus on a DiP definition. Several drafts have been distributed on the consortium’s web site inviting feedback and comment. The current version is, “The Dissertation in Practice is a scholarly endeavor that impacts a complex problem of practice” (CPED, 2014). What is agreed upon by the consortium is that the DiP is focused on practice, and that local context matters. Faculty in EdD programs must have a clear sense of the nature of problems in practice among their constituent base, appropriate types of inquiry used to address those issues, and the manner in which results can be conveyed in authentic, productive ways (Sands et al., 2013).

Key Principles and Components of an Innovative DiP

The nature and format of the DiP diverge (Archbald, 2008; CPED, 2012; Sands et al., 2013). The first major discussion about the attributes of the CPED DiP occurred at the second convening (Fall, 2007), at Vanderbilt University (Storey & Hartwick, 2010). Peabody College faculty and recent program graduates described their DiP’s client-based process. Faculty expressed that the DiP’s primary objective is to provide a program candidate with an opportunity to show they are informed and have the critical skills and knowledge to address complex educational problems (Smrekar & McGraner, 2009). They indicated that the EdD candidate could exemplify a skill set including deep knowledge and understanding of inquiry, organizational theory, resource deployment, leadership studies, and the broad social context associated with problems of educational policy and practice (Caboni & Proper, 2009). Faculty asserted that while DiPs may vary by focus area, geographical location, institutions (school, district, agency, association), and scope (case study, systematic review, program assessment, program proposal), all share common characteristics related to rigorous analysis in a realistic operational context (Smrekar & McGraner, 2009). In the convening’s keynote speech, Guthrie (2009) argued that if capstone requirements for research and practice are the same in EdD and PhD programs, then program purposes, research preparation, and practitioner professional training have been woefully compromised.

During the Fall 2012 convening, consortium members tackled the development of a set of standards and criteria to assess the DiP. Questions regarding the requirements of DiP remained, however. In response to a proposed standard that the DiP “is expected to have generative impact on the future work and agendas of the scholar practitioner” (CPED, 2012), members asked, “What is meant by generative impact? Is this doable in a dissertation capstone?” Members wondered if APA was the appropriate stylistic guide for the formatting of final products, and whether blogs, websites, graphic novel, or YouTube videos were appropriate products (Sands et al., 2013).

Participants at the 2009 convening developed six Working Principles to guide the consortium’s work (Perry & Imig, 2010):

The professional doctorate in education:

- Is framed around questions of equity, ethics, and social justice to bring about solutions to complex problems of practice.

- Prepares leaders who can construct and apply knowledge to make a positive difference in the lives of individuals, families, organizations, and communities.

- Provides opportunities for candidates to develop and demonstrate collaboration and communication skills to work with diverse communities and to build partnerships.

- Provides field-based opportunities to analyze problems of practice and use multiple frames to develop meaningful solutions.

- Is grounded in and develops a professional knowledge base that integrates both practical and research knowledge, that links theory with systemic and systematic inquiry.

- Emphasizes the generation, transformation, and use of professional knowledge and practice.

These principles guide institutions as they develop the DiP’s conceptual foundation. Scholarly practitioners blend practical wisdom with professional skills and knowledge to name, frame, and solve problems of practice. They disseminate work in multiple ways, with an obligation to resolve problems of practice by collaborating with key stakeholders, including the partners from schools, community, and the university. The second CPED principle, inquiry as practice, poses significant questions focused on complex problems of practice. By using various research, theories, and professional wisdom, scholarly practitioners design innovative solutions to improve problems of practice. Inquiry of Practice requires the ability to gather, organize, judge, aggregate, and analyze situations, literature, and data with a critical lens (Sands et al., 2013). The final CPED principle relates directly to the DiP as the culminating experience that demonstrates the scholarly practitioner’s ability to solve problems of practice and exhibit the doctoral candidate’s ability “to think, to perform, and to act with integrity” (Shulman, 2005, p. 5).

In 2012, CPED formed a DiP Award Committee to develop assessment criteria for DiPs nominated for the CPED DiP of the Year Award, and to review submitted DiPs for the award. To develop the assessment criteria, the committee drew on Archbald’s (2008) work, which specified four qualities that a reimagined EdD doctoral thesis should address: (a) developmental efficacy, (b) community benefit, (c) stewardship of doctoral values, and (d) distinctiveness of design. In arguing for a problem solving study, Archbald advised that unlike a research dissertation, findings are not the goal. Rather, the problem-based thesis’ goals are decisions, changed practices, and better organizational performances.

At the June 2012 convening, hosted by California State University (Fresno), the DiP committee guided members in a Critical Friends activity, “Defining Criteria for a Dissertation in Practice”. Subsequently, the 2012 DiP Committee developed and circulated the draft criteria, inviting feedback from CPED members.

At the October 2012 convening, hosted by at The College of William and Mary, the DiP Award Committee proposed their assessment criteria and requested additional feedback from CPED colleagues (CPED, 2013). The assessment rubric was revised, responsive to the feedback, and was circulated to a wider consortium membership for public comment on CPED’s website. Review of this feedback led to item criteria refinement along with performance indicators:

- Demonstrates an understanding of, and possible solution to, the problem of practice. (Indicators: Demonstrates an ability to address and/or resolve a problem of practice and/or generate new practices.)

- Demonstrates the scholarly practitioner’s ability to act ethically and with integrity. (Indicators: Findings, conclusions and recommendations align with the data.)

- Demonstrates the scholarly practitioner’s ability to communicate effectively in writing to an appropriate audience in a way that addresses scholarly practice. (Indicators: Style is appropriate for the intended audience.)

- Integrates both theory and practice to advance practical knowledge. (Indicators: Integrates practical and research-based knowledge to contribute to practical knowledge base; Frames the study in existing research on both theory and practice.)

- Provides evidence of the potential for impact on practice, policy, and/or future research in the field. (Indicators: Dissertation indicates how its findings are expected to impact professional field or problem.)

- Uses methods of inquiry that are appropriate to the problem of practice. (Indicators: Identifies rationale for method of inquiry that is appropriate to the dissertation in practice; effectively uses method of inquiry to address problem of practice.)

The DiP Award Committee conducted two rounds of review for the DiP Annual Award, applying the above assessment criteria.

What Makes a Professional Practice DiP?

In this section, we turn to the international community for guidance in answering two major issues concerning the CPED Award Committee as they wrestled with the assessment criteria. First, what should a DiP look like? Second, how should DiP potential impact be measured?

Numerous national and international bodies govern qualifications and specifications for what doctoral level work should look like, e.g., European University Association (2005), Council of Deans and Directors of Graduate Studies, Australia (2007), Council of Graduate Schools (2008), Quality Assurance Agency (2012). Common to all is the emphasis on critical assessment of the originality of findings presented in the dissertation in the context of the literature and the research. Fulton, Kuit, Sanders and Smith (2013) drew on their experience teaching in a Professional Practice Doctoral program at the University of Sunderland in England, concluding that the “ability to design research objectively and logically, and then to critically review and evaluate findings, is what makes it doctoral level, not the actual findings themselves” (p.152). In their view, the difference between a PhD and a Professional Practice Doctorate is the demonstration of knowledge production that makes a significant contribution to the profession. O’Mullane (2005) noted that while the structure of a DiP may be similar to that of a PhD dissertation, it should contain additional reflective elements relating to personal reflections on the learning journey. But the question remains, what should a DiP look like? O’Mullane (2005) identified six outputs currently used by universities to demonstrate a significant contribution to the profession:

- Thesis or dissertation alone;

- Portfolio and/or professional practice and analysis;

- A reflection and analysis of a significant contribution to knowledge over time or from one major work;

- Published scholarly works recognized as a significant and original contribution to knowledge;

- Portfolio and presentation (performance in music, visual arts, drama); and

- Professional practice and internship with mentors.

These six DiP designs can be found within CPED; a group DiP design is also being explored. Universities are offering several DiP design choices: (a) Baylor University’s DiP can be thematic, assessment, action research, or three articles; (b) California State University San Marcos’ DiP can be a policy brief, executive summary, or series of articles; (c) Rutgers University’s DiP can be thematic, assessment, three article, action research, portfolio, or 3 “products” tied together with an introduction and conclusion; and (d) the University of Arkansas’ DiP can be an executive summary and article submission for publication in a peer reviewed scholarly journal (CPED data, 2013). O’Mullane (2005) also identified the essentials of a DiP:

- Create new knowledge.

- Make a significant contribution to your profession.

- Explicit conceptual framework.

- Literature review should provide the context to the research question, and should demonstrate that the question is worth asking.

- Demonstrable evidence of how ideas have been synthesized in the light of experience and in the context of academic literature, and how this has created new knowledge.

- Demonstration that findings have been reflected on, logically planned, and progressed through the research.

- Independently construct arguments for and against the findings and use evidence to support your interpretation.

- A distinctive voice should be clearly heard although what is said should be supported by evidence.

- Use the university’s designated reference style consistently. (pp.149-150)

Fulton et al. (2013) suggested that “the creation of new knowledge and significant contribution” are critical, and likely to give any DiP assessor the most difficulty. Not only does “the creation of new knowledge and significant contribution” vary between professions, but the opportunity to influence a profession also tends to be based on position and length of service. To bring clarity to the problem of “significant contribution,” O’Mullane (2005) suggested two classifications, active or inactive, in terms of contribution to the profession. An active contribution generates new significant knowledge, which results in significant improvement in practice. An inactive contribution generates significant knowledge that has not yet been disseminated.

Current Rhetoric and Reality of DiPs: An Action Research Study Methods of the Study

For this action research study (Lewin, 1944; Stringer, 2007), we gathered data from an online survey from the eight member DiP Award Committee. Members came from a variety of institutions; four had previous Dissertation Award Committee experience with American Education Research Association special interest groups. The authors of this paper were among those who provided data.

Quantitative and qualitative data were gathered using a Qualtrics administered survey with Likert responses and assessors’ comments. Each survey item was scored 1 to 4, with 1 indicating “unacceptable,” 2 “developing,” 3 “target,” and 4 “exceptional”.

Each member of the committee responded to an email invitation to complete a blind review of four DiP synopses submitted by the nominated candidate. Two committee members assessed each synopsis against the assessment item criteria, with a third assessment by the committee chair, as needed. Based on the quantitative scores and qualitative comments of the synopses, the pool was narrowed from 25 to 6 DiPs. A second blind review of the full text of the six DiPs was conducted with each committee member reading the full DiP and submitting criteria assessment data in Qualtrics.

Limitations

The authors of this paper are DiP Award Committee members, which could cause bias in interpretation. The committee members’ initial judgments were based on the submitted synopses; some may not have adequately represented the overall DiPs quality. The sample was neither random nor sufficiently large to draw generalizable conclusions. 14 DiPs came from three Phase 1 institutions. While not surprising that most submissions came from Phase 1 institutions, multiple submissions from any institution was unexpected.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each DiP synopsis assessed on the six CPED assessment items (Table 1). Item means ranged from 2.78 to 2.94 with an overall mean of 2.86. The median was 3 (“Target”) for each of the six items and the mode was 3 (“Target”) for all items except item #5, where the mode was 2.

Table 1. Item Statistics for the DiP Award Assessment Survey

Across the range of 300 individual responses (2 reviewers x 25 dissertations x 6 survey items), a 1 (Unacceptable) was selected only four times, while 4 (Exceptional) was selected 50 times. The remaining 246 responses were either a 2 (Developing) or 3 (Target), indicating considerable restriction of range at both ends of the scale. As for measures of central tendency, the median of 3 (Target), and a grand mean of 2.86, indicate that overall, reviewers found the DiP to be near “Target” based on the review criteria.

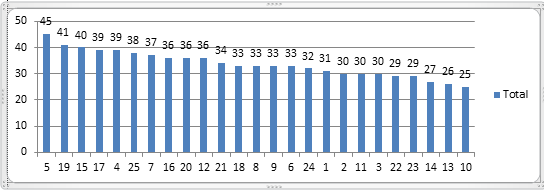

Figure 1 shows a frequency distribution of total scores for the 25 DiPs submitted for review. The numbers on the X-axis represent a unique identifier for the 25 reviewed DiPs. The scale ranged from 0-48 possible points (6 items of the survey x 4 maximum points allowed x 2 reviewers). The observed scores ranged from 25 to 45 with no obvious natural breaks in the distribution.

Figure 1 . Frequency distribution of scores across 25 DiPs synopses. Prior to scoring, the DiP Award Committee predicted that an analysis of the score distribution might reveal a natural break that could be useful to narrow the pool for further review. Because there were no obvious natural breaks, the committee, after careful review of both the quantitative and the qualitative data, agreed that the top six scoring DiPs would move forward for a full text review.

The format of 24 DiPs was the traditional (five chapter) dissertation, with one non-traditional chapter. All had single authors. Two submissions implemented results of their study and showed immediate impact. The average page length of the 25 DiPs was 212, with a range of 85-377 pages. Four studies used quantitative methods, 17 used qualitative methods, and four used mixed methods. The methodology used in 10 studies was action research, case studies, grounded theory, and phenomenology.

In additional to numerical rating, the DiP Committee members commented on quality and overall alignment with the DiP assessment criteria. For DiPs that received similar, or identical marks, committee members reviewed the reflective comments, re-read the synopses, and continued meetings via Skype, Adobe Connect, or by phone. The inclusion of quality data provided a point of reference to triangulate perspectives regarding the eventual five finalists.

Critical reflections and subsequent comments can often appear somewhat tenuous. Elements of ambiguity may exist in such reviews, and reviewers may be guilty of overgeneralizing. As the process continued, a clear inter-rater agreement (Creswell, 2013) was evident among committee members.

The qualitative data confirmed the quantitative findings. Regarding those dissertations where the mean was closer to the “exceptional” category, some reviewers stated:

- A timely paper and excellent report

- Good example of an important problem of practice

- High potential for impact

- Meaningful and insightful

- Well-developed

- Important examples of a problem of practice

- Good interdisciplinary foundation

A characteristic of all submitted DiPs was addressing immediate needs in practice. Some were assessments of existing programs; others delved into theoretical constructs and inquired about their applicability to educational issues within the local, regional, or national context. Among these studies, a few took their inquiry directly into the classroom. While the DiPs that rose to the top during the review process were regarded by their submitting institutions as exemplary, not all addressed all of the assessment criteria in their synopsis.

Critical assessment of the DiPs indicated that most CPED member institutions remain unclear about what constitutes an exemplary DiP. While the conclusions drawn from the 2009 Peabody convening asserted that all share a set of common characteristics related to rigorous analysis in a realistic operational setting (Smrekar & McGraner, 2009), the DiP Award Committee’s analysis of 25 submissions revealed a continuum of alignment to the Working Principles for Professional Practice Programs.

Discrepancy in alignment to the Working Principles may be indicative of an analogous disconnect between the central principles that were developed by the consortium to guide all programs in 2009 and what is, in reality, being practiced currently among Phase I and II CPED institutions. The assumption that these principles would be tested during Phase II seems to be flawed, borne out by the analysis of the 2013 data. Alternately, the discrepancy in alignment to the Working Principles may also reflect the need for additional refinement and discussion around the rubric used for review by the DiP Award Committee. Again, because the rubric evolved from a community-based process, further refinements may require similar processes of discussion and recommendation from the broader constituency.

Many of the DiP submissions lacked clear evidence of impact on practice, a characteristic that is foundational to the Working Principles. While submissions demonstrate the author’s ability to generate solutions, whether a complex problem of practice had been identified in the studies was unclear in a majority of the submissions. Additionally, it was unclear in most submissions whether the author included implications for generative solutions at the local and/or broad context. Drawing on the work of Bryk, Gomez, and Grunow (2010), the six Core Principles of Improvement Science suggest the following:

- Make the work problem-specific and user-centered.

- Variation in performance is the core problem to address.

- See the system that produces the current outcomes.

- We cannot improve at scale what we cannot measure.

- Anchor practice improvement in disciplined inquiry.

- Accelerate improvements through networked communities.

Concluding Remarks

The analysis of DiPs and the narrative presented is indicative of both the challenges institutions face and their pervasiveness, as faculty wrestle with the design of a professional practice doctorate program. While challenging, the identification of common issues provides an opportunity for institutions to engage in conversation with others that appear to have found solutions to some of the challenges. Such conversation is a start to ensuring program rigor and consistency at both a national and international level. Learning in situ develops praxis in education. At the core, the creation of generative knowledge forms a substantive epistemology that guides the construction of meaning and builds confidence in decision makers.

To re-imagine and redesign the EdD will require innovation, a commitment that has now been made by the growing membership of CPED, now collaborating on a global stage to rethink the fundamental purpose of doctoral education with specific focus on the professional practice doctorate, the EdD.

Andrews, R., & Grogan, M. (2005). Form should follow function: Removing the EdD. dissertation from Ph.D. straightjacket. UCEA Review , 46(2), 10–13.

Archbald, D. (2008). Research versus problem solving for the Education Leadership doctoral thesis: Implications for form and function. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44 (5), 704–739.

Bryk A. S., Gomez L. M. & Grunow A. (2010). Getting ideas into action: Building networked improvement communities in education. Stanford, CA: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Caboni, T., & Proper, E. (2009). Re-envisioning the professional doctorate for educational leadership and higher educational leadership: Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College EdD. program. Peabody Journal of Education, 84 (1), 61–68.

Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate. (2012). Consortium members . Retrieved from http://cpedinitiative.org/consortium-members

Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate. (2013). Dissertation in Practice of the Year Award . Retrieved from http://cpedinitiative.org/dissertation-practice-year-award

Council of Australian Deans and Directors of Graduate Studies. (2007). Guidelines on professional doctorates. Adelaide, Australia: Council of Australian Deans and Directors of Graduate Studies. Retrieved from https://www.gs.unsw.edu.au/policy/findapolicy/abapproved/policydocuments/05_07_professional_doctorates_guidelines.pdf

Council of Graduate Schools. (2008). Task force report of the professional doctora te. Washington, DC: Author.

European University Association. (2005). Salzburg Principles, as set out in the European Universities’ Association’s (EUA) Bologna Seminar report. Retrieved from http://www.eua.be/eua/jsp/en/upload/Salzburg_Conclusions.1108990538850.pdf

European University Association. (2005). Salzburg principles, as set out in the European Universities’ Association’s (EUA) Bologna seminar report. Retrieved from http://www.eua.be/eua/jsp/en/upload/Salzburg_Conclusions.1108990538850.pdf

Evans, R. (2007). Comments on Shulman, Golde, Bueschel, and Garabedian: Existing practice is not the template. Educational Researcher, 36 (6), 553–559. Doi: 10.3102/0013189X07313149 in S.I.

Fulton, J., Kuit, J., Sanders, G., & Smith, P. (2013). The professional doctorate: A practical guide. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Guthrie, J. (2009). The case for a modern Doctor of Education Degree (EdD.): Multipurpose education doctorates no longer appropriate. Peabody Journal of Education, 84 (1), 2–7.

Hamilton, P., Johnson, R., & Poudrier, C. (2010). Measuring educational quality by appraising theses and dissertations: Pitfalls and remedies. Teaching in Higher Education, 15 (5), 567–577.