Addressing the Root Cause: Rising Health Care Costs and Social Determinants of Health

Affiliation.

- 1 deputy director, Clinical and Operations, Division of Medical Assistance, North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Raleigh, North Carolina [email protected].

- PMID: 29439099

- DOI: 10.18043/ncm.79.1.26

The United States is the only high-income country that does not have publicly-financed universal health care, yet it has one of the world's highest public health care expenditures. This financial outlay is not bringing the desired result in health outcomes because the root cause is not being addressed: solving the systematic disparities and social determinants that lead to poor health and health inequities. Targeting resources for the most vulnerable populations and linking health care plans with community-based organizations to address social determinants of health at the outset is a cost-effective means of preventing expensive chronic illnesses and health inequities.

©2018 by the North Carolina Institute of Medicine and The Duke Endowment. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Health Care Costs / statistics & numerical data*

- Health Promotion / organization & administration

- Health Services Accessibility / statistics & numerical data

- Healthcare Disparities / statistics & numerical data*

- Income / statistics & numerical data

- Social Determinants of Health / statistics & numerical data*

- United States

- Universal Health Insurance / organization & administration

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 23 June 2020

The high cost of prescription drugs: causes and solutions

- S. Vincent Rajkumar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5862-1833 1

Blood Cancer Journal volume 10 , Article number: 71 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

97k Accesses

65 Citations

273 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cancer therapy

- Public health

Global spending on prescription drugs in 2020 is expected to be ~$1.3 trillion; the United States alone will spend ~$350 billion 1 . These high spending rates are expected to increase at a rate of 3–6% annually worldwide. The magnitude of increase is even more alarming for cancer treatments that account for a large proportion of prescription drug costs. In 2018, global spending on cancer treatments was approximately 150 billion, and has increased by >10% in each of the past 5 years 2 .

The high cost of prescription drugs threatens healthcare budgets, and limits funding available for other areas in which public investment is needed. In countries without universal healthcare, the high cost of prescription drugs poses an additional threat: unaffordable out-of-pocket costs for individual patients. Approximately 25% of Americans find it difficult to afford prescription drugs due to high out-of-pocket costs 3 . Drug companies cite high drug prices as being important for sustaining innovation. But the ability to charge high prices for every new drug possibly slows the pace of innovation. It is less risky to develop drugs that represent minor modifications of existing drugs (“me-too” drugs) and show incremental improvement in efficacy or safety, rather than investing in truly innovative drugs where there is a greater chance of failure.

Causes for the high cost of prescription drugs

The most important reason for the high cost of prescription drugs is the existence of monopoly 4 , 5 . For many new drugs, there are no other alternatives. In the case of cancer, even when there are multiple drugs to treat a specific malignancy, there is still no real competition based on price because most cancers are incurable, and each drug must be used in sequence for a given patient. Patients will need each effective drug at some point during the course of their disease. There is seldom a question of whether a new drug will be needed, but only when it will be needed. Even some old drugs can remain as virtual monopolies. For example, in the United States, three companies, NovoNordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, and Eli Lilly control most of the market for insulin, contributing to high prices and lack of competition 6 .

Ideally, monopolies will be temporary because eventually generic competition should emerge as patents expire. Unfortunately, in cancers and chronic life-threatening diseases, this often does not happen. By the time a drug runs out of patent life, it is already considered obsolete (planned obsolescence) and is no longer the standard of care 4 . A “new and improved version” with a fresh patent life and monopoly protection has already taken the stage. In the case of biologic drugs, cumbersome manufacturing and biosimilar approval processes are additional barriers that greatly limit the number of competitors that can enter the market.

Clearly, all monopolies need to be regulated in order to protect citizens, and therefore most of the developed world uses some form of regulations to cap the launch prices of new prescription drugs. Unregulated monopolies pose major problems. Unregulated monopoly over an essential product can lead to unaffordable prices that threaten the life of citizens. This is the case in the United States, where there are no regulations to control prescription drug prices and no enforceable mechanisms for value-based pricing.

Seriousness of the disease

High prescription drug prices are sustained by the fact that treatments for serious disease are not luxury items, but are needed by vulnerable patients who seek to improve the quality of life or to prolong life. A high price is not a barrier. For serious diseases, patients and their families are willing to pay any price in order to save or prolong life.

High cost of development

Drug development is a long and expensive endeavor: it takes about 12 years for a drug to move from preclinical testing to final approval. It is estimated that it costs approximately $3 billion to develop a new drug, taking into account the high failure rate, wherein only 10–20% of drugs tested are successful and reach the market 7 . Although the high cost of drug development is a major issue that needs to be addressed, some experts consider these estimates to be vastly inflated 8 , 9 . Further, the costs of development are inversely proportional to the incremental benefit provided by the new drug, since it takes trials with a larger sample size, and a greater number of trials to secure regulatory approval. More importantly, we cannot ignore the fact that a considerable amount of public funding goes into the science behind most new drugs, and the public therefore does have a legitimate right in making sure that life-saving drugs are priced fairly.

Lobbying power of pharmaceutical companies

Individual pharmaceutical companies and their trade organization spent approximately $220 million in lobbying in the United States in 2018 10 . Although nations recognize the major problems posed by high prescription drug prices, little has been accomplished in terms of regulatory or legislative reform because of the lobbying power of the pharmaceutical and healthcare industry.

Solutions: global policy changes

There are no easy solutions to the problem of high drug prices. The underlying reasons are complex; some are unique to the United States compared with the rest of the world (Table 1 ).

Patent reform

One of the main ways to limit the problem posed by monopoly is to limit the duration of patent protection. Current patent protections are too long, and companies apply for multiple new patents on the same drug in order to prolong monopoly. We need to reform the patent system to prevent overpatenting and patent abuse 11 . Stiff penalties are needed to prevent “pay-for-delay” schemes where generic competitors are paid money to delay market entry 12 . Patent life should be fixed, and not exceed 7–10 years from the date of first entry into the market (one-and-done approach) 13 . These measures will greatly stimulate generic and biosimilar competition.

Faster approval of generics and biosimilars

The approval process for generics and biosimilars must be simplified. A reciprocal regulatory approval process among Western European countries, the United States, Canada, and possibly other developed countries, can greatly reduce the redundancies 14 . In such a system, prescription drugs approved in one member country can automatically be granted regulatory approval in the others, greatly simplifying the regulatory process. This requires the type of trust, shared standards, and cooperation that we currently have with visa-free travel and trusted traveler programs 6 .

For complex biologic products, such as insulin, it is impossible to make the identical product 15 . The term “biosimilars” is used (instead of “generics”) for products that are almost identical in composition, pharmacologic properties, and clinical effects. Biosimilar approval process is more cumbersome, and unlike generics requires clinical trials prior to approval. Further impediments to the adoption of biosimilars include reluctance on the part of providers to trust a biosimilar, incentives offered by the manufacturer of the original biologic, and lawsuits to prevent market entry. It is important to educate providers on the safety of biosimilars. A comprehensive strategy to facilitate the timely entry of cost-effective biosimilars can also help lower cost. In the United States, the FDA has approved 23 biosimilars. Success is mixed due to payer arrangements, but when optimized, these can be very successful. For example, in the case of filgrastim, there is over 60% adoption of the biosimilar, with a cost discount of approximately 30–40% 16 .

Nonprofit generic companies

One way of lowering the cost of prescription drugs and to reduce drug shortages is nonprofit generic manufacturing. This can be set up and run by governments, or by nonprofit or philanthropic foundations. A recent example of such an endeavor is Civica Rx, a nonprofit generic company that has been set up in the United States.

Compulsory licensing

Developed countries should be more willing to use compulsory licensing to lower the cost of specific prescription drugs when negotiations with drug manufacturers on reasonable pricing fail or encounter unacceptable delays. This process permitted under the Doha declaration of 2001, allows countries to override patent protection and issue a license to manufacture and distribute a given prescription drug at low cost in the interest of public health.

Solutions: additional policy changes needed in the United States

The cost of prescription drugs in the United States is much higher than in other developed countries. The reasons for these are unique to the United States, and require specific policy changes.

Value-based pricing

Unlike other developed countries, the United States does not negotiate over the price of a new drug based on the value it provides. This is a fundamental problem that allows drugs to be priced at high levels, regardless of the value that they provide. Thus, almost every new cancer drug introduced in the last 3 years has been priced at more than $100,000 per year, with a median price of approximately $150,000 in 2018. The lack of value-based pricing in the United States also has a direct adverse effect on the ability of other countries to negotiate prices with manufacturers . It greatly reduces leverage that individual countries have. Manufacturers can walk away from such negotiations, knowing fully well that they can price the drugs in the United States to compensate. A governmental or a nongovernmental agency, such as the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER), must be authorized in the United States by law, to set ceiling prices for new drugs based on incremental value, and monitor and approve future price increases. Until this is possible, the alternative solution is to cap prices of lifesaving drugs to an international reference price.

Medicare negotiation

In addition to not having a system for value-based pricing, the United States has specific legislation that actually prohibits the biggest purchaser of oral prescription drugs (Medicare) from directly negotiating with manufacturers. One study found that if Medicare were to negotiate prices to those secured by the Veterans Administration (VA) hospital system, there would be savings of $14.4 billion on just the top 50 dispensed oral drugs 17 .

Cap on price increases

The United States also has a peculiar problem that is not seen in other countries: marked price increases on existing drugs. For example, between 2012 and 2017, the United States spent $6.8 billion solely due to price increases on the existing brand name cancer drugs; in the same period, the rest of the world spent $1.7 billion less due to decreases in the prices of similar drugs 18 . But nothing illustrates this problem better than the price of insulin 19 . One vial of Humalog (insulin lispro), that costs $21 in 1999, is now priced at over $300. On January 1, 2020, drugmakers increased prices on over 250 drugs by approximately 5% 20 . The United States clearly needs state and/or federal legislation to prevent such unjustified price increases 21 .

Remove incentive for more expensive therapy

Doctors in the United States receive a proportionally higher reimbursement for parenteral drugs, including intravenous chemotherapy, for more expensive drugs. This creates a financial incentive to choosing a more expensive drug when there is a choice for a cheaper alternative. We need to reform physician reimbursement to a model where the amount paid for drug administration is fixed, and not proportional to the cost of the drug.

Other reforms

We need transparency on arrangements between middlemen, such as pharmacy-benefit managers (PBMs) and drug manufacturers, and ensure that rebates on drug prices secured by PBMS do not serve as profits, but are rather passed on to patients. Drug approvals should encourage true innovation, and approval of marginally effective drugs with statistically “significant” but clinically unimportant benefits should be discouraged. Importation of prescription drugs for personal use should be legalized. Finally, we need to end direct-to-patient advertising.

Solutions that can be implemented by physicians and physician organizations

Most of the changes discussed above require changes to existing laws and regulations, and physicians and physician organizations should be advocating for these changes. It is disappointing that there is limited advocacy in this regard for changes that can truly have an impact. The close financial relationships of physician and patient organizations with pharmaceutical companies may be preventing us from effective advocacy. We also need to generate specific treatment guidelines that take cost into account. Current guidelines often present a list of acceptable treatment options for a given condition, without clear recommendation that guides patients and physicians to choose the most cost=effective option. Prices of common prescription drugs can vary markedly in the United States, and physicians can help patients by directing them to the pharmacy with the lowest prices using resources such as goodrx.com 22 . Physicians must become more educated on drug prices, and discuss affordability with patients 23 .

IQVIA. The global use of medicine in 2019 and outlook to 2023. https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/the-global-use-of-medicine-in-2019-and-outlook-to-2023 (Accessed December 27, 2019).

IQVIA. Global oncology trends 2019. https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/global-oncology-trends-2019 (Accessed December 27, 2019).

Kamal, R., Cox, C. & McDermott, D. What are the recent and forecasted trends in prescription drug spending? https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/recent-forecasted-trends-prescription-drug-spending/#item-percent-of-total-rx-spending-by-oop-private-insurance-and-medicare_nhe-projections-2018-27 (Accessed December 31, 2019).

Siddiqui, M. & Rajkumar, S. V. The high cost of cancer drugs and what we can do about it. Mayo Clinic Proc. 87 , 935–943 (2012).

Article Google Scholar

Kantarjian, H. & Rajkumar, S. V. Why are cancer drugs so expensive in the United States, and what are the solutions? Mayo Clinic Proc. 90 , 500–504 (2015).

Rajkumar, S. V. The high cost of insulin in the united states: an urgent call to action. Mayo Clin. Proc. ; this issue (2020).

DiMasi, J. A., Grabowski, H. G. & Hansen, R. W. Innovation in the pharmaceutical industry: new estimates of R&D costs. J. Health Econ. 47 , 20–33 (2016).

Almashat, S. Pharmaceutical research costs: the myth of the $2.6 billion pill. https://www.citizen.org/news/pharmaceutical-research-costs-the-myth-of-the-2-6-billion-pill/ (Accessed December 31, 2019) (2017).

Prasad, V. & Mailankody, S. Research and development spending to bring a single cancer drug to market and revenues after approval. JAMA Intern. Med. 177 , 1569–1575 (2017).

Scutti, S. Big Pharma spends record millions on lobbying amid pressure to lower drug prices. https://www.cnn.com/2019/01/23/health/phrma-lobbying-costs-bn/index.html (Accessed December 31, 2019).

Amin, T. Patent abuse is driving up drug prices. https://www.statnews.com/2018/12/07/patent-abuse-rising-drug-prices-lantus/ (Accessed November 16, 2019).

Hancock, J. & Lupkin, S. Secretive ‘rebate trap’ keeps generic drugs for diabetes and other ills out of reach. https://khn.org/news/secretive-rebate-trap-keeps-generic-drugs-for-diabetes-and-other-ills-out-of-reach/ (Accessed November 16, 2019).

Feldman, R. ‘One-and-done’ for new drugs could cut patent thickets and boost generic competition. https://www.statnews.com/2019/02/11/drug-patent-protection-one-done/ (Accessed December 31, 2019).

Cohen, M. et al. Policy options for increasing generic drug competition through importation. Health Affairs Blog https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190103.333047/full/ (Accessed November 16, 2019).

Bennett, C. L. et al. Regulatory and clinical considerations for biosimilar oncology drugs. Lancet Oncol 15 , e594–e605 (2014).

Fein, A. J. We shouldn’t give up on biosimilars—and here are the data to prove it. https://www.drugchannels.net/2019/09/we-shouldnt-give-up-on-biosimilarsand.html (Accessed December 31, 2019).

Venker, B., Stephenson, K. B. & Gellad, W. F. Assessment of spending in medicare part D if medication prices from the department of veterans affairs were used. JAMA Intern. Med. 179 , 431–433 (2019).

IQVIA. Global oncology trends 2018. https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/global-oncology-trends-2018 (Accessed January 2, 2018).

Prasad, R. The human cost of insulin in America. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-47491964 (Accessed November 16, 2019).

Erman, M. More drugmakers hike U.S. prices as new year begins. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-healthcare-drugpricing/more-drugmakers-hike-u-s-prices-as-new-year-begins-idUSKBN1Z01X9 (Accessed January 3, 2020).

Anderson, G. F. It’s time to limit drug price increases. Health Affairs Blog. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190715.557473/full/ (Accessed November 16, 2019).

Gill, L. Shop around for lower drug prices. Consumer Reports 2018. https://www.consumerreports.org/drug-prices/shop-around-for-better-drug-prices/ (Accessed November 16, 2019).

Warsame, R. et al. Conversations about financial issues in routine oncology practices: a multicenter study. J. Oncol. Pract. 15 , e690–e703 (2019).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The Division of Hematology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

S. Vincent Rajkumar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to S. Vincent Rajkumar .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supported in part by grants CA 107476, CA 168762, and CA186781 from the National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD, USA.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Vincent Rajkumar, S. The high cost of prescription drugs: causes and solutions. Blood Cancer J. 10 , 71 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-020-0338-x

Download citation

Received : 23 April 2020

Revised : 08 June 2020

Accepted : 10 June 2020

Published : 23 June 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-020-0338-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Oral contraceptive pills shortage in lebanon amidst the economic collapse: a nationwide exploratory study.

- Rania Itani

- Hani MJ Khojah

- Abdalla El-Lakany

BMC Health Services Research (2023)

K-means clustering of outpatient prescription claims for health insureds in Iran

- Shekoofeh Sadat Momahhed

- Sara Emamgholipour Sefiddashti

- Zahra Shahali

BMC Public Health (2023)

An Industry Survey on Unmet Needs in South Korea’s New Drug Listing System

- Ji Yeon Lee

- Jong Hyuk Lee

Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science (2023)

Voice of a caregiver: call for action for multidisciplinary teams in the care for children with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome

- Linda Burke

- Sidharth Kumar Sethi

- Rupesh Raina

Pediatric Nephrology (2023)

Analysis of new treatments proposed for malignant pleural mesothelioma raises concerns about the conduction of clinical trials in oncology

- Tomer Meirson

- Valerio Nardone

- Luciano Mutti

Journal of Translational Medicine (2022)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Projected costs of single-payer healthcare financing in the United States: A systematic review of economic analyses

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation UCSF School of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California, United States of America

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, United States of America

Affiliation David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California, United States of America

Affiliation School of Public Health, University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, California, United States of America

Roles Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing

- Christopher Cai,

- Jackson Runte,

- Isabel Ostrer,

- Kacey Berry,

- Ninez Ponce,

- Michael Rodriguez,

- Stefano Bertozzi,

- Justin S. White,

- James G. Kahn

- Published: January 15, 2020

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003013

- Reader Comments

The United States is the only high-income nation without universal, government-funded or -mandated health insurance employing a unified payment system. The US multi-payer system leaves residents uninsured or underinsured, despite overall healthcare costs far above other nations. Single-payer (often referred to as Medicare for All), a proposed policy solution since 1990, is receiving renewed press attention and popular support. Our review seeks to assess the projected cost impact of a single-payer approach.

Methods and findings

We conducted our literature search between June 1 and December 31, 2018, without start date restriction for included studies. We surveyed an expert panel and searched PubMed, Google, Google Scholar, and preexisting lists for formal economic studies of the projected costs of single-payer plans for the US or for individual states. Reviewer pairs extracted data on methods and findings using a template. We quantified changes in total costs standardized to percentage of contemporaneous healthcare spending. Additionally, we quantified cost changes by subtype, such as costs due to increased healthcare utilization and savings due to simplified payment administration, lower drug costs, and other factors. We further examined how modeling assumptions affected results. Our search yielded economic analyses of the cost of 22 single-payer plans over the past 30 years. Exclusions were due to inadequate technical data or assuming a substantial ongoing role for private insurers. We found that 19 (86%) of the analyses predicted net savings (median net result was a savings of 3.46% of total costs) in the first year of program operation and 20 (91%) predicted savings over several years; anticipated growth rates would result in long-term net savings for all plans. The largest source of savings was simplified payment administration (median 8.8%), and the best predictors of net savings were the magnitude of utilization increase, and savings on administration and drug costs ( R 2 of 0.035, 0.43, and 0.62, respectively). Only drug cost savings remained significant in multivariate analysis. Included studies were heterogeneous in methods, which precluded us from conducting a formal meta-analysis.

Conclusions

In this systematic review, we found a high degree of analytic consensus for the fiscal feasibility of a single-payer approach in the US. Actual costs will depend on plan features and implementation. Future research should refine estimates of the effects of coverage expansion on utilization, evaluate provider administrative costs in varied existing single-payer systems, analyze implementation options, and evaluate US-based single-payer programs, as available.

Author summary

Why was this study done.

- As the US healthcare debate continues, there is growing interest in “single-payer” also known as “Medicare for All.” Single-payer uses a simplified public funding approach to provide everyone with high-quality health insurance.

- Public support for provision of universal health coverage through a plan like Medicare for All is as high as 70%, but falls when costs are emphasized.

- Economic models help assess the financial viability of single-payer. Yet, models vary widely in their assumptions and methods, and can be hard to compare.

What did the researchers do and find?

- We found and compared cost analyses of 22 single-payer plans for the US or individual states.

- Nineteen (86%) of the analyses estimated that health expenditures would fall in the first year, and all suggested the potential for long-term cost savings.

- The largest savings were predicted to come from simplified billing and lower drug costs.

- Studies funded by organizations across the political spectrum estimated savings for single-payer.

What do these findings mean?

- There is near-consensus in these analyses that single-payer would reduce health expenditures while providing high-quality insurance to all US residents.

- To achieve net savings, single-payer plans rely on simplified billing and negotiated drug price reductions, as well as global budgets to control spending growth over time.

- Replacing private insurers with a public system is expected to achieve lower net healthcare costs.

Citation: Cai C, Runte J, Ostrer I, Berry K, Ponce N, Rodriguez M, et al. (2020) Projected costs of single-payer healthcare financing in the United States: A systematic review of economic analyses. PLoS Med 17(1): e1003013. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003013

Academic Editor: Zirui Song, Massachusetts General Hospital, UNITED STATES

Received: May 6, 2019; Accepted: December 17, 2019; Published: January 15, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Cai et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All included articles are publicly available and can be found using our search methodology.

Funding: CC, JR, IO and KB each received a student summer research grant of $750 each from Physicians for a National Health Program ( http://pnhp.org/about/ ) to support this study. No other support. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish or manuscript preparation.

Competing interests: I have read the journal’s policy and the authors of this manuscript have the following competing interests: CC is an executive board member of Students for a National Health Program (SNaHP). SNaHP had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish or manuscript preparation.

Abbreviations: ACO, accountable care organization; OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; VA, US Veterans Administration

Introduction

Nine years after passage of the Affordable Care Act, 10.4% (27.9 million) of the nonelderly US population remains uninsured [ 1 ]. Lack of insurance is associated with worse health outcomes, including death [ 2 ], due to decreased access to healthcare and preventive services [ 3 – 5 ]. Underinsurance, defined as cost sharing that represents significant financial barriers to care or risk of catastrophic medical expenditures, is rising and is associated with a 25% or greater likelihood of omitted or delayed care [ 6 , 7 ]. Low-income adults with public insurance have improved access and quality of care compared to uninsured adults [ 8 ].

Meanwhile, healthcare costs continue to rise, approaching one-fifth of the economy. In 2018, national health expenditures reached $3.6 trillion, equivalent to 17.7% of GDP [ 9 ]. Government funding, including public programs, private insurance for government employees, and tax subsidies for private insurance, represented 64% of national health expenditures in 2013, or 11% of GDP, more than total health expenditures in almost any other nation [ 10 ]. Higher costs in the US are due primarily to higher prices and administrative inefficiency, not higher utilization [ 11 – 13 ].

An oft-proposed alternative to the contemporary multi-payer system is single-payer, also referred to as Medicare for All. Key elements of single-payer include unified government or quasi-government financing, universal coverage with a single comprehensive benefit package, elimination of private insurers, and universal negotiation of provider reimbursement and drug prices. Single-payer as it has been proposed in the US has no or minimal cost sharing. Polled support for single-payer is near an all-time high, as high as two-thirds of Americans [ 14 ] and 55% of physicians [ 15 ]. Two-thirds of Americans support providing universal health coverage through a national plan like Medicare for All as an extremely high priority for the incoming Congress [ 16 ]. However, support varies substantially according to how single-payer is described [ 17 ]. As of November 2019, there are 2 “Medicare for All Act of 2019” legislative proposals in the US Congress: Senate Bill 1129 and House of Representatives Bill 1384.

Economic analyses are crucial for formally estimating the net cost of single-payer proposals. These models estimate how potential added costs of single-payer, due to increased utilization of services, compare with the savings induced by simplified payment administration, lower drug prices, and other factors. Such economic projections can shape plan design, contribute to policy discourse, and affect the viability of legislation. As single-payer proposals gain legislative traction, the importance of economic models rises.

However, these analyses are complex and heterogeneous, making generalizations difficult. Findings vary across studies, from large “net savings” to “net costs,” as do modeling assumptions, such as the extent of administrative savings and presence or absence of drug price negotiations. The diversity of findings contributes to political spin and fuels popular uncertainty over the anticipated costs of a single-payer healthcare system. For example, a 2018 study by Pollin et al. (Political Economy Research Institute) estimated that a national Medicare for All system would save $313 million in the first year of implementation, while a 2018 study by Blahous (Mercatus Center) found that the same system would save $93 million in the first year, and a 2016 report from Holahan et al. (Urban Institute) suggested that a modified form of this proposal, e.g., relying on private insurers, would increase costs [ 18 – 20 ]. Variation in single-payer proposals and analytic approaches likely explains many of the differences in outcomes across studies, but no comparative review has been undertaken, to our knowledge.

The goal of this study is to systematically review economic analyses of the cost of single-payer proposals in the US (both national and state level), summarize results in a logical but accessible manner, examine the association of findings with plan features and with analytic methods, and, finally, examine the empirical evidence regarding key study assumptions.

We specified in advance that we would extract and quantitatively compare increased costs due to utilization rises and savings due to administrative simplification, drug savings, and other factors. We searched for studies by examining existing lists, querying experts, and searching online. Ethics approval was not deemed to be necessary since all data were publicly available. All data are available in the original studies, which are listed in S1 Appendix . We included studies that examined insurance plans with essential single-payer features and that provided adequate technical detail on inputs and results. For these studies, we extracted information about plan features, analytic assumptions, and findings (costs due to higher utilization, savings of all types, and net costs; see Table A in S1 Appendix for definitions of terms). We expressed all estimates as a percentage of contemporaneous healthcare spending, to facilitate comparison across settings and time periods. We summarized study methods and findings graphically and analyzed associations between studies and spending estimates.

We adopted a broad search strategy, reflecting our initial assessment (subsequently confirmed) that economic models of the cost of single-payer plans are not published in academic journals. We conducted all components of our search from June 1 to December 31 of 2018.

We searched in PubMed, Google Scholar, and Google, using combinations of (“Single-payer” OR “single-payer”) AND (“cost” OR “model” OR “economic” OR “cost-benefit”). We limited our Google search to 10 pages of results. We consulted existing lists maintained by Physicians for a National Health Program and Healthcare-NOW [ 21 , 22 ]. We asked a convenience sample of 10 single-payer experts. We also searched the websites of leading advocacy and industry-sponsored groups in favor of single-payer reform (Physicians for a National Health Plan and Healthcare-NOW) and in opposition to single-payer reform (Partnership for America’s Health Care Future). Additional search details are provided in Table B in S1 Appendix . A PRISMA flow diagram is provided in Fig 1 . A PRISMA checklist can be found in Table G in S1 Appendix .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003013.g001

Inclusion and exclusion

“Single-payer” has a wide range of definitions, both in the US and internationally. We chose inclusion and exclusion criteria that were most consistent with single-payer plans that have been proposed in the US. For example, while some single-payer plans internationally have included private intermediaries within a unified payment system, US proposals have omitted a role for private insurers. Thus, we use private intermediaries as an exclusion criterion. Notably, recent healthcare proposals such as “Medicare Extra for All” would not meet our inclusion criteria [ 23 ].

Study inclusion required appropriateness of both the plan and the analysis. Specific inclusion criteria for the plan were that (1) all legal residents are permanently covered for a standard comprehensive set of medically appropriate outpatient and inpatient medical services under one payer and (2) the payer is a not-for-profit government or quasi-government agency. Other central single-payer features, such as providers being entirely in or out, uniform payments with no balance billing, and use of a drug formulary, are often unspecified and thus were assumed present (and thus not a basis for exclusion) unless explicitly omitted. Some plans include undocumented immigrants, and some exclude them. Exclusion criteria were (1) use of large cost-sharing measures such as deductibles (some US single-payer plans include small copays, e.g., $5–$10 for an outpatient visit, which was not considered grounds for exclusion) and (2) an explicit role for non-uniform payment levels (i.e., payments differing by patient), balance billing, multiple payment systems, multiple drug formularies, or private insurers or intermediaries. Importantly, we applied these criteria to the modeled plan, so models incorporating any of these features when analyzing an otherwise qualifying single-payer plan would be excluded. These excluded studies are listed in Table C in S1 Appendix . Finally, we excluded 12 plans from 11 studies that met inclusion criteria but were redundant to newer studies of similar single-payer plans by the same analysis teams already included (Table D in S1 Appendix ). Net savings from these excluded studies were similar to those from the included studies (Table E in S1 Appendix ).

For the analysis, all studies were required (1) to specify input assumptions and values based on transparent review of empirical evidence and (2) to report (a) increases in utilization and costs due to improved insurance/access, (b) savings due to simplified payment administration (a single payment process using one set of coverage and reimbursement rules), lower drug prices, and other specified reasons, and (c) total system costs and net costs of the single-payer plan.

For this report, we did not require or consider financing (revenue) plans, which turn on an entirely different set of technical issues. We also did not seek analyses of broader economic effects, such as de-investing in the private insurance market or facilitation of labor mobility and start-ups through delinking of insurance and employment. Our analysis also omits long-term effects on medical innovation.

Studies were reviewed by at least 2 team members before finalizing inclusion or exclusion. Uncertain decisions (e.g., regarding adequacy of technical information or severity of deviation from the study definition of single-payer) were discussed with the entire team.

We extracted the following information from each study: annual healthcare costs without single-payer (specified for the year and setting, at the national or state level), initial-year annual cost under single-payer, cost increase due to utilization growth, and savings (from all sources and 4 specific categories: simplified payment administration, lowered costs for medications [and for durable medical equipment, if bundled together], reduced clinical inefficiency [i.e., unneeded procedures] and fraud, and a switch to Medicare payment rates, which are lower than private insurance rates). We did not report transition costs such as purchases of for-profit businesses and training (which were, in any case, rarely assessed), and no study quantified the costs of potential first-year implementation challenges. If available, we extracted longer term costs and savings, defined as costs or savings accumulated subsequent to the first year of implementation. We also extracted or calculated the utilization increase assumed for newly insured individuals.

Each study was reviewed by 2 team members, and all study extractions were reviewed by the senior investigator (JGK), who requested refinements and further documentation for unclear or unexpected values. When we had questions due to omissions or ambiguity in the report, we attempted to contact study authors. We also sent them, when successfully located, a report draft for review.

We standardized all cost numbers to percentage of contemporaneous total health system costs, to allow for direct comparison across times and locations. This approach obviated the need for inflation adjustments. We standardized costs due to increased utilization as the increase in annual cost for the newly insured divided by the mean cost for the already insured. We examined results visually, ordered by year and by net cost (highest net cost to highest net savings).

To assess the association of net cost with plan and analysis features (e.g., whether drug price reductions were considered), we used a visual method (color-coding analysis features). We also conducted univariate and multivariate linear regressions with net savings or cost as the outcome and with the following predictors: utilization increase, specific savings categories, type of funder organization, and type of analyst organization. In the multivariate analysis, we assigned dummy variables for missingness of the utilization predictor.

Studies identified

We reviewed 90 studies and included primary analyses of 22 single-payer plans from 18 studies, published between 1991 and 2018, including 8 national and 14 state-level plans (Massachusetts, California, Maryland, Vermont, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, New York, and Oregon). Included studies are listed in Table F in S1 Appendix . Analysis teams included US government agencies, business consultants and research organizations, and academics. Nine single-payer plans (from 6 studies) were excluded for the following reasons: age limits on single-payer, varied benefits across individuals, balance billing, inclusion of private insurers or intermediaries in the plan or analysis, and lack of specification of assumptions regarding utilization and savings. Twelve studies were not reviewed because of duplication (same author, different state, earlier, n = 11) and age (1971, n = 1).

Projected costs and savings

Net cost or savings in the first year of single-payer operation varies from an increase of 7.2% of system costs to a reduction of 15.5% ( Fig 2 ). The median finding was a net savings of 3.5% of system costs, and analyses of 19 of 22 plans found net savings. Net costs reflect the balance of added costs due to higher utilization (by eliminating uninsurance and in some studies also capturing the increase due to ending underinsurance) and savings (via payment simplification, lower drug prices, and other factors). Higher utilization increases costs by 2.0% to 19.3% (median 9.3%). Total savings range from 3.3% to 26.5% (median 12.1%).

The median finding was savings (−3.46% of total health system costs), and analyses of 19 of 22 plans found net savings.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003013.g002

The cost increase due to expansion of insurance coverage varies due to the number of newly covered individuals and generosity of coverage benefits, but also reflects policy components and expert assessment. For example, study estimates of increased utilization by newly covered individuals range from 25% to 80% of the costs for those already insured, reflecting varied assessments of uninsured individuals’ healthcare access and health status. Additionally, cost-control choices such as copays vary across plans.

The mix of projected savings from single-payer shows both consistent and variable elements across studies ( Fig 3 ). All studies estimate lower costs due to simplified payment administration, but vary in the size of these savings and in the inclusion and magnitude of other savings. Administrative savings vary from 1.2% to 16.4% (median 8.8%) of healthcare spending. Savings from lowered prices for medications and durable medical equipment are included in 12 models and range from 0.2% to 7.9%. Savings from reduced fraud and waste are included in 10 models and range from 0.4% to 5.0%. Savings due to a shift to Medicare payment rates are included in 8 models and range from 1.4% to 10.0%. Over time, utilization increases are stable and projected savings grow, leading to larger estimates for potential savings.

Plans listed in order by year. Simplified payment administration was the greatest source of savings, for a median of 8.8%.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003013.g003

In the long term, projected net savings increase, due to a more tightly controlled rate of growth. For the 10 studies with projections for up to 11 years, each year resulted in a mean 1.4% shift toward net savings (Text A and Figs A and B in S1 Appendix ). At this rate, the 3 studies that find net costs in the first year would achieve net savings by 10 years.

Influence of plan and analysis features on findings

Fig 4 presents net costs or savings alongside a color-coded summary of key plan features and model assumptions. The 3 of 22 models that found net costs in the first year shared specific policy choices including low or no cost sharing (copays), rich benefit packages, and a lack of savings predicted from reduced medication/medical equipment costs. Two of these models (Hsiao 2011 Low Cost Sharing and CBO 1993 SP2) are estimated for additional scenarios that yield net savings.

The 3 models that found net costs in the first year (Hsiao 2011 Low Cost Sharing, CBO 1993 SP2, and White 2017) shared specific policy choices including low or no cost sharing (copays), rich benefit packages, and a lack of savings captured from reduced medication/medical equipment costs.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003013.g004

We next assessed whether the inclusion of different analysis features (yes or no) was associated with net costs, based on univariate regressions ( Fig 5 ). Cost sharing did not have a significant association with net costs across all studies (2.0 points, 95% CI −3.1 to 7.1, p = 0.43); 11 of 19 analyses showing net savings in the first year included no or low cost sharing in their plans. Similarly, the association between inclusion of undocumented individuals and net costs was not statistically significant (−2.7 points, 95% CI −7.8 to 2.4, p = 0.28). Inclusion of medication and equipment savings in the model was associated with lower net costs by 7.0 points (95% CI −11.1 to –3.0, p = 0.002), and inclusion of efficiency gains and fraud reduction was associated with lower net costs by 4.3 points but not significant (95% CI −9.1 to 0.6, p = 0.08). Inclusion of a shift to Medicare payment rates was not a strong predictor of net costs. We cannot assess the association between net costs and presence or absence of administrative savings in these dichotomous analyses because all studies include these savings. The number of different analysis features included in the model was also associated with lower net costs. For each additional analysis feature included, net costs were reduced by 2.3 points (95% CI –4.3 to –0.3, p = 0.02).

Each estimate comes from a separate linear regression of net costs and a binary predictor. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003013.g005

In univariate regressions of net savings against the magnitude of inputs, several relationships emerge ( Fig 6 ). A 1-point increase in utilization rate was associated with higher net costs of 9.9 points; however, this relationship did not reach statistical significance (95% CI −6.3 to 26.0, p = 0.22). In contrast, the magnitude of net savings was associated with higher savings in administrative costs (net cost −0.85 points, 95% CI −1.3 to −0.4, p = 0.01) and in medication and equipment costs (−1.79 points, 95% CI −2.43 to −1.16, p < 0.0001). Net savings were not strongly related to Medicare payment rates or efficiency gains/fraud reduction.

(A) Utilization rate; (B) administrative savings; (C) medicine and equipment savings; (D) efficiency gains and fraud reduction; (E) Medicare payment rate. Each dot represents 1 model. The red lines represent linear regressions, with displayed results indicating the regression equation (including intercept and slope) and R 2 (proportion of variation explained). The regression line for Medicare payment rate (E) was omitted due to the preponderance of 0 values (73%, or all but 6, of the 22 models). Higher utilization was associated with greater costs, whereas the magnitude of administrative and medication/equipment savings was associated with reduced net costs.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003013.g006

In a multivariate regression (limited by small sample size), we found that net costs were associated with medication and equipment cost savings (−1.5 points, 95% CI −2.6 to −0.4, p = 0.01); other analysis features did not strongly predict net costs. Lower net costs were associated with funder type (left-leaning versus right-leaning: −6.7 points, 95% CI −11.5 to −1.8, p = 0.009) and analyst type (academic versus other: 7.6 points, 95% CI 0.4 to 14.9, p = 0.04) in bivariate regressions, but not in multivariate regressions, perhaps due to reduced precision due to the sample size. Tables H and I in S1 Appendix report the multivariate regression details.

We identified 22 credible economic models of the cost of single-payer financing in the US, from a variety of government, business consultant, and academic organizations. We found that 19 (86%) predict net savings in the first year of operations, with a range from 7% higher net cost to 15% lower net cost. Increases in cost due to improved insurance coverage and thus higher utilization were 2% to 19%. Savings from simplified payment administration at insurers and providers, drug cost reductions, and other mechanisms ranged from 3% to 27%. The largest net savings were for plans with reductions in drug costs. Net savings accumulate over time at an estimated 1.4% per year. Of note, we excluded 2 widely publicized studies [ 20 , 24 ], both of which found net costs, on the grounds that these studies made assumptions that included private insurance intermediaries (i.e., not a single-payer) or lacked technical detail for evaluation.

These analyses suggest that single-payer can save money, even in year 1, incorporating a wide range of assumptions about potential savings. More aggressive measures to realize cost reductions are projected to yield greater net savings. This implies that concerns about health system cost growth with single-payer may be misplaced, though costs to government are likely to grow as tax-based financing replaces private insurance premiums and out-of-pocket spending.

Empirical evidence for model assumptions

The results of these economic models depend on input assumptions regarding the effect of single-payer provisions. In particular, the magnitude of net savings reflects the quantitative effects of utilization rises due to increased insurance and savings strategies. Reasonable analysts may differ on these assumptions based on plan features, setting, and evidence available at the time of modeling. There is growing empirical evidence for each provision, which we review below.

Utilization increases due to new and improved insurance drive the cost growth effects of single-payer. There is strong evidence over decades that the newly insured roughly double their healthcare utilization [ 25 – 27 ]. Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act appears to demonstrate a mix of utilization effects [ 28 , 29 ]. Moreover, in a single-payer system, the newly insured may be younger and healthier than the already insured, meaning that utilization may not increase to the levels of the already insured. Evidence on utilization increases for the underinsured are mixed [ 30 – 32 ]. Importantly, there is evidence that when uninsured individuals gain insurance, increases in utilization for the newly insured are balanced by slightly lower utilization for the already insured, due to supply-side constraints [ 33 – 35 ]. However, with a decrease in billing-related administrative burden for clinicians, a 10% or greater rise in physician clinical capacity may occur, which would accommodate additional care utilization. Finally, increases in utilization for the uninsured and underinsured are likely to result in increased use of preventive services, which should lead to some future cost saving [ 25 , 36 ].

Simplified payment administration represents the largest type of savings from single-payer. There is very strong evidence that billing and insurance-related administrative burden is higher in the US than in Canada (which has single-payer) by 12%–15% of total healthcare costs [ 13 ]. The excess administrative costs are split roughly 50% at insurers and 50% at providers. Studies of hospitals find consistent large differences in administrative costs between the US and single-payer systems in Europe [ 37 ]. There is no direct evidence of ability to capture all of this excess, but solid empirical data from Canada and other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries support the intuition that administrative costs would sharply decrease with elimination or streamlining of existing onerous payment processes.

Lower drug spending is typically the second largest source of savings with single-payer, and predicts large net savings. The US Veterans Administration (VA) gets a 30% discount on prescription medications compared to private Medicare Advantage Plans [ 38 , 39 ]. US per-capita drug spending exceeds that of any other country [ 38 , 39 ]. Drug prices are the primary driver of higher cost, with the US spending $1,011 annually per capita on prescription drugs compared to the OECD average of $422 [ 11 ].

Research estimates savings of 30% for diabetes drugs through use of drug formularies, due to medication choice and prices [ 40 ]. Drug companies argue that reducing prices will reduce research and innovation. However, many more expensive drugs offer limited medical benefits [ 38 , 41 , 42 ]. Further, drug firms often raise prices after recovering development costs. Research and development costs for 10 companies that launched new cancer agents were $9 billion, while revenue exceeded $67 billion [ 43 ]. Perhaps most tellingly, Fortune 500 drug companies had a mean profit reported in 2019 of 24% compared to 9% for all corporations [ 38 , 44 , 45 ]. Drug companies claim that if the entire health system gets the same discount as the VA, the discount levels will substantially decrease. However, if Medicare adopted the VA’s tighter drug formulary, the savings would be roughly $505 per capita annually [ 46 ]. Overall, there is strong evidence of the potential for a substantial reduction in drug costs, with magnitude likely a function of political choices and dynamics. A portion of these savings could also be realized if the government negotiated for lower drug prices in the existing Medicare program.

Reports estimate that up to 20%–40% of US healthcare spending is fraudulent or wasteful [ 47 , 48 ]. However, there is little evidence on how to avoid this spending. The Affordable Care Act set up accountable care organizations (ACOs), groups of healthcare providers responsible for a defined set of patients and contracting with a payer (usually Medicare) for a payment structure tied to performance metrics, in an effort to reduce costs. Recent ACO demonstration projects found minimal savings, potentially less than the cost of administering programs, leading to overall net 0 savings [ 49 ]. ACOs that are “two-sided” (using both penalties and shared savings) reduce service costs by a mean of 0.7% yet require on average about 2% costs to administer [ 50 , 51 ]. Overall, between 2013 and 2017, ACOs increased total costs to Medicare by 70 billion when bonuses were taken into account [ 52 ]. Recent analysis suggests modestly growing savings, in physician if not hospital groups, potentially more than administration costs [ 53 , 54 ]. Single-payer may facilitate efforts to reduce fraud and waste by providing comprehensive and consistent clinical encounter data within the single billing system (including diagnoses and services, as well as clinical outcomes). Thus, single-payer might bolster the marginally effective efforts in this area. Still, the evidence to support large reductions in waste and fraud is tenuous. Furthermore, a reliance on ACO incentive approaches (which require large patient panels and specific payment structures) could undermine desired features of a single-payer program, such as free choice of provider, substantial use of fee-for-service billing in some plans, and hospital global budgeting. In light of these uncertainties, most economic models do not anticipate reductions in fraud or waste, and those that do generally assume only a modest reduction.

Limitations

Our analysis has several important limitations. First, the included economic studies varied in methodological rigor and quality of reporting, funding sources, political motivations, and amount of evidence cited to support claims. Although we tried to classify studies by major single-payer and analysis characteristics, uncaptured variations may have added noise in the comparison. Relatedly, the diversity of plans under study did not allow for a formal meta-analysis, which is designed to integrate empirical evaluations of standardized interventions, especially using measures of association such as odds ratios.

Second, we did not apply quality rating scores for the included economic studies. We found no quality rating scores for health system modeling, as existing scores are intended for evaluation studies, empirical measurements of costs and effects, or decision analyses [ 55 – 57 ]. A quality rating system could be useful. Included studies all lacked sensitivity analyses, and the selection of the most appropriate data source for input values could be subjective. For example, studies varied in what percentage of savings could be achieved through simplification of payment administration. We are unaware of studies analyzing the effects of other key inputs, such as reductions in reimbursement rate. Future research is needed to assess the quality of single-payer studies, analyze key model inputs, and analyze proposed ranges for sensitivity analyses. In terms of the potential for financial conflict of interest bias, we were reassured that a prominent health business consultant (Lewin Group, with several included analyses), presumably with clients that stand to lose money with single-payer, nonetheless found net savings.

Third, no single-payer system has been implemented in the US, due to lack of government approval even for demonstration projects. Thus, there is no domestic, large-scale empirical example to properly test the economic models. Much of the research on single-payer is based on evidence from single-payer nations such as Canada, Australia, and Taiwan. As reviewed above, US health systems that approximate single-payer, such as the VA, and other empirical studies provide support for model assumptions. Ultimately, our goal was not to compare cost models with (nonexistent) empirical benchmarks, but to assess the consistency of inputs across models and with empirical evidence, and to characterize patterns in model findings. Assuming that US single-payer demonstrations are coming, economic models can be tested and refined. Until then, the relative consistency of existing models is the best evidence available.

Fourth, our study was limited to proposals of single-payer as defined in the US, with a single (government) payer, and meeting specified criteria. Our results are not generalizable to multi-payer “universal coverage” reforms, which would likely show substantially smaller savings and thus increases in net cost [ 58 ]. The Maryland all-payer model, for example, showed 2.7% savings after 3 years, a figure that is significantly lower than the average savings from single-payer systems we found in our review [ 59 ]. Multi-payer systems have higher costs in part due to increased cost shifting. Our analysis is not able to quantify precisely the effects of reduced cost sharing. A unified provider payment system, as opposed to a single-payer system, may accomplish substantial cost savings, but our analysis only considered the latter. Indeed, many OECD countries have a unified payment system with a standard benefits package, a single payment process, a single formulary, and not-for-profit insurers, which shares many features with “single-payer.” Finally, despite the drawbacks of our narrow inclusion criteria, a benefit is that our results provide a clearer and more relevant assessment of the economic impact of a single-payer system in the US.

Fifth, in addition to saving costs, unified payment models such as single-payer have the potential to foster quality and efficient care through payment signals, as well as to monitor trends in care patterns via rapid access to highly standardized claims data. For example, in Japan’s unified payment system, price incentives are used to promote public health goals, such as increasing preventive care [ 60 ]. The use of price incentives to drive performance is common in high-income countries [ 61 ]. However, studies did not include this in their analysis, so we deemed it outside the scope of our study.

Sixth, as with any review, our search period is time-limited, ending in December 2018. We are aware of 1 study in 2019 [ 62 ], but did not systematically search for other studies. We limited our Google searches to 10 pages. However, we never found a relevant study after page 2 of search results, increasing our confidence that a 10-page review was adequate. We will update this analysis in coming years.

Finally, we examined only economic studies of system operating costs, in the first year and over time. We ignored one-time transition costs (in particular, purchase of for-profit entities, unemployment and pension benefits, and retraining of displaced workers). Informal review of existing evidence suggests that these costs are small in comparison to health system spending, which is 18% of the economy. We also did not examine financing, e.g., taxation strategies. These are important next steps.

Policy implications

This review highlights a high degree of analytic consensus that single-payer financing would result in a favorable outcome for system financial burden: efficiency savings exceed added costs. A net cost reduction of 3%–4% is likely initially, growing over time. Net savings would be expected to occur, if not immediately, certainly within a few years. However, maximizing performance and savings will require optimized implementation. Payment procedures must be as simple as in other countries, drug prices a substantial reduction from contemporary levels, and comprehensive clinical data used in sophisticated ways to identify and reduce inappropriate care. The logical next step is real-world experimentation, including evaluation and refinement to minimize transition costs and achieve modeled performance in reality.

Supporting information

S1 appendix. additional detail on methods and findings..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003013.s001

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lauren Carroll for assistance in searching.

- 1. Tolbert J, Orgera K, Singer N, Damico A. Key facts about the uninsured population. San Francisco Kaiser Family Foundation; 2019 Dec 13 [cited 2019 Dec 18]. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/fact-sheet/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/ .

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 6. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2018 Employer health benefits survey. Oakland (CA): Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 24]. https://www.kff.org/report-section/2018-employer-health-benefits-survey-section-5-market-shares-of-health-plans/ .

- 7. Collins SR, Rasmussen PW, Beutel S, Doty MM. The problem of underinsurance and how rising deductibles will make it worse: findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2014. New York: Commonwealth Fund; 2015.

- 9. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National health expenditure data: historical. Baltimore: Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 18]. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html .

- 14. Stein L, Cornwell S, Tanfani J. Inside the progressive movement roiling the Democratic Party. Reuters. 2018 Aug 23 [cited 2019 Dec 18]. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-election-progressives/ .

- 15. Serafini M. Why clinicians support single-payer—and who will win and lose. NEJM Catalyst. 2018 Jan 17.

- 16. POLITICO, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Americans’ health and education priorities for the new congress in 2019. Boston: Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; 2019 Jan [cited 2019 Dec 18]. https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/94/2019/01/Politico-Harvard-Poll-Jan-2019-Health-and-Education-Priorities-for-New-Congress-in-2019.pdf .

- 17. Kaiser Family Foundation. Public opinion on single-payer, national health plans, and expanding access to Medicare coverage. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2019 Nov 26 [cited 2019 Dec 18]. https://www.kff.org/slideshow/public-opinion-on-single-payer-national-health-plans-and-expanding-access-to-medicare-coverage/ .

- 18. Pollin R, Heintz J, Arno P, Wicks-Lim J, Ash M. Economic analysis of Medicare for All. Amherst (MA): Political Economy Research Institute, University of Massachusetts Amherst; 2018 Nov 30 [cited 2019 Dec 18]. https://www.peri.umass.edu/publication/item/1127-economic-analysis-of-medicare-for-all .

- 19. Blahous C. The costs of a national single-payer healthcare system. Arlington (VA): Mercatus Center, George Mason University; 2018 Jul [cited 2019 Dec 18]. https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/blahous-costs-medicare-mercatus-working-paper-v1_1.pdf .

- 20. Holahan J, Buettgens M, Clemans-Cope L, Favreault MM, Blumberg LJ, Ndwandwe S. The Sanders single-payer health care plan: the effect on national health expenditures and federal and private spending. Washington (DC): Urban Institute; 2016 May 9 [cited 2019 Dec 18]. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/sanders-single-payer-health-care-plan-effect-national-health-expenditures-and-federal-and-private-spending/view/full_report .

- 21. Hellander I. How much would single payer cost? A summary of studies compiled by Ida Hellander, M.D. Chicago: Physicians for a National Health Program; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 18]. http://pnhp.org/how-much-would-single-payer-cost/ .

- 22. Healthcare-NOW. Listing of single payer studies. Boston: Healthcare-NOW; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 18]. https://www.healthcare-now.org/single-payer-studies/listing-of-single-payer-studies/ .

- 23. Center for American Progress. Medicare Extra for All: a plan to guarantee universal health coverage in the United States. Washington (DC): Center for American Progress; 2018 Feb 22 [cited 2019 Dec 18]. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/healthcare/reports/2018/02/22/447095/medicare-extra-for-all/ .

- 24. Thorpe KE. An analysis of Senator Sanders single payer plan. Boston: Healthcare-NOW; 2016 [cited 2019 Dec 29]. https://www.healthcare-now.org/296831690-Kenneth-Thorpe-s-analysis-of-Bernie-Sanders-s-single-payer-proposal.pdf .

- 32. Kaiser Family Foundation. When high deductibles hurt: even insured patients postpone care. San Francisco: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2017 Jul 28 [cited 2019 Dec 18]. https://khn.org/news/when-high-deductibles-hurt-even-insured-patients-postpone-care/ .

- 33. Fauke C, Himmelstein D. Doubling down on errors: Urban Institute defends its ridiculously high single payer cost estimates. HuffPost. 2017 Dec 6 [cited 2019 Dec 18]. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/steffie-woolhandler/urban-institute-errors-single-payer-costs_b_10100836.html .

- 40. Hogervorst M. A qualitative and quantitative assessment on drug pricing methods in a single-payer system in the U.S. [master’s thesis]. Utrecht: Utrecht University; 2019.

- 41. Patented Medicine Prices Review Board. Annual report 2016. Ottawa: Patented Medicine Prices Review Board; 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 19]. http://www.pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca/view.asp?ccid=1334 .

- 44. Drug Channels. Profits in the 2019 Fortune 500: manufacturers vs. managed care vs. pharmacies, PBMs, and wholesalers. Philadelphia: Drug Channels; 2019 Aug 27 [cited 2019 Dec 29]. https://www.drugchannels.net/2019/08/profits-in-2019-fortune-500.html .

- 45. Fox J. Corporate profits are down, but wages are up. New York: Bloomberg; 2019 Sep 1 [cited 2019 Dec 29]. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-09-01/corporate-profits-are-down-but-wages-are-up .

- 47. Young PL, Saunders RS, Olsen L. The healthcare imperative: lowering costs and improving outcomes: workshop series summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2010.

- 48. Chisholm D, Evans DB. Improving health system efficiency as a means of moving towards universal coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010 [cited 2019 Dec 19]. https://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/healthreport/28UCefficiency.pdf .

- 49. Sullivan K. Seema Verma hyperventilates about tiny differences between ACOs exposed to one-and two-sided risk. The Health Care Blog. 2018 Aug 21 [cited 2019 Dec 19]. https://thehealthcareblog.com/blog/2018/08/21/seema-verma-hyperventilates-about-tiny-differences-between-acos-exposed-to-one-and-two-sided-risk/ .

- 50. Verma S. Pathways to success: a new start for Medicare’s accountable care organizations. Health Affairs Blog. 2018 Aug 9 [cited 2019 Dec 19]. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180809.12285/full/ .

- 51. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to Congress: Medicare and the healthcare delivery system. Washington (DC): Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2018 Jun 15 [cited 2019 Dec 19]. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun18_medpacreporttocongress_sec.pdf .

- 52. Office of Inspector General. Medicare shared savings program accountable care organizations have shown potential for reducing spending and increasing quality. Washington (DC): Department of Health and Human Services; 2017 Aug [cited 2019 Dec 19]. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-15-00450.pdf .

- 53. Bleser WK, Muhlestein D, Saunders RS, McClellan MB. Half a decade in, Medicare accountable care organizations are generating net savings: Part 1. Health Affairs Blog. 2018 Sep 20 [cited 2019 Dec 19]. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180918.957502/full/ .

- 55. Joanna Briggs Institute. The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews: checklist for economic evaluations. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017 [cited 2019 Dec 19]. https://joannabriggs.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Economic_Evaluations2017_0.pdf .

- 58. Lewin Group. Cost and coverage analysis of nine proposals to expand health insurance coverage in California. Falls Church (VA): Lewin Group; 2002 Apr 12 [cited 2019 Dec 19]. https://health-access.org/images/documents_other/health_care_options_project/hcop_lewin_report.pdf .

- 59. Haber S, Beil H, Amico P, Morrison M, Akhmerova V, Beadles C, et al. Evaluation of the Maryland all-payer model: third annual report. Waltham (MA): RTI International; 2018 [cited 2019 Dec 19]. https://downloads.cms.gov/files/cmmi/md-all-payer-thirdannrpt.pdf .

- 60. Ikegami N, editor. Universal health coverage for inclusive and sustainable development: lessons from Japan. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2014 [cited 2019 Dec 19]. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/263851468062350384/pdf/Universal-health-coverage-for-inclusive-and-sustainable-development-lessons-from-Japan.pdf .

- 61. Figueras J, Robinson R, Jakubowski E, editors. Purchasing to improve health systems performance. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Series. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005 [cited 2019 Dec 19]. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/98428/E86300.pdf .

- 62. Liu J, Eibner C. National health spending estimates under Medicare for All. Santa Monica (CA): RAND; 2019 [cited 2019 Dec 19]. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3106.html .

Understanding why health care costs in the U.S. are so high

The high cost of medical care in the U.S. is one of the greatest challenges the country faces and it affects everything from the economy to individual behavior, according to an essay in the May-June 2020 issue of Harvard Magazine written by David Cutler , professor in the Department of Global Health and Population at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Cutler explored three driving forces behind high health care costs—administrative expenses, corporate greed and price gouging, and higher utilization of costly medical technology—and possible solutions to them.

Read the Harvard Magazine article: The World’s Costliest Health Care

- Issue Brief

Health Care Costs: What’s the Problem?

The cost of health care in the United States far exceeds that in other wealthy nations across the globe. In 2020, U.S. health care costs grew 9.7%, to $4.1 trillion, reaching about $12,530 per person. 1 At the same time, the United States lags far behind other high-income countries when it comes to both access to care and some health care outcomes. 2 As a result, policymakers and health care systems are facing increasing demands for more care at lower costs for more people. And, of course, everyone wants to know why their health care costs are so high.

The answer depends, in part, on who’s asking this question: Why does U.S. health care cost so much? Public policy often highlights and targets the total cost of the health care system or spending as a percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP), while most patients (the public) are more concerned with their own out-of-pocket costs and whether they have access to affordable, meaningful insurance. Providers feel public pressure to contain costs while trying to provide the highest-quality care to patients.

This brief is the first in a series of papers intended to better define some of the key questions policymakers should be asking about health care spending: What costs are too high? And can they be controlled through policy while improving access to care and the health of the population?

What (or Who) Is to Blame for the High Costs of Care?

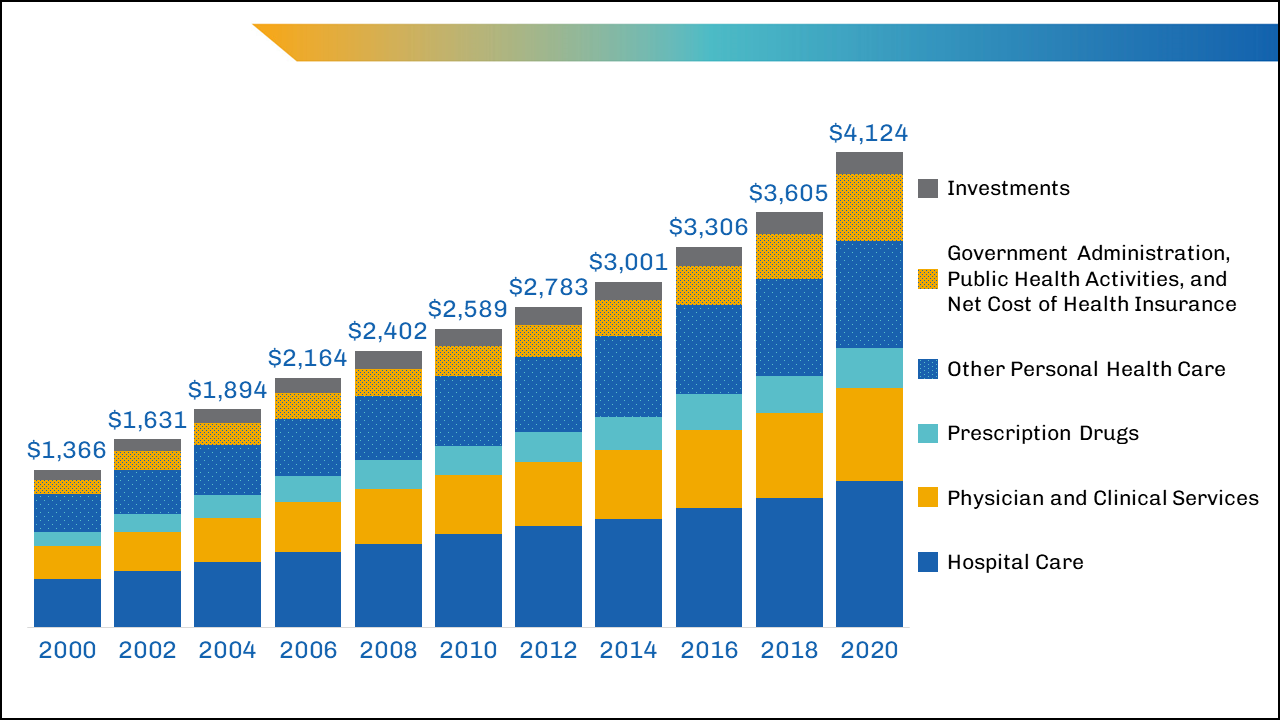

Total U.S. health care spending has increased steadily for decades, as have costs and spending in other segments of the U.S. economy. In 2020, health care spending was $1.5 trillion more than in 2010 and $2.8 trillion more than in 2000. While total spending on clinical care has increased in the past two decades, health care spending as a percentage of GDP has remained steady and has hovered around 20% of GDP in recent years (with the largest single increase being in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic). 1 Health care spending in 2020 (particularly public outlays) increased more than in previous years because of increased federal government support of critical COVID-19-related services and expanded access to care during the pandemic. Yet, no single sector’s health care cost — doctors, hospitals, equipment, or any other sector — has increased disproportionately enough over time to be the single cause of high costs.

One of the areas in health care with the highest levels of spending in the United States is hospital care, which has accounted for about 30% of national health care spending 3 for the past 60 years (and has remained very close to 31% for the past 20 years) (Figure 1). Although hospital spending is the focus of many cost-control policies and public attention, the increases are consistent with the increases seen across other areas of health care, such as for physicians and other professional services. Total spending for some smaller parts of nonhospital care has more than doubled over the past few decades and makes up an increasing proportion of total spending. For instance, home health care as a percentage of total spending tripled between 1980 and 2020, from 0.9% to 3.0%, and drug spending nearly doubled as a proportion of health care spending between 1980 and 2006, from 4.8% to 10.5%, and currently represent 8.4% of health care spending. 1

image description

The largest areas of spending that might yield the greatest potential for savings — such as inpatient care and physician-provided care — are unlikely to be reduced by lowering the total number of insured patients or visits per person, given the growing, aging U.S. population and the desire to cover more, not fewer, individuals with adequate health insurance.