Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Make a Successful Research Presentation

Turning a research paper into a visual presentation is difficult; there are pitfalls, and navigating the path to a brief, informative presentation takes time and practice. As a TA for GEO/WRI 201: Methods in Data Analysis & Scientific Writing this past fall, I saw how this process works from an instructor’s standpoint. I’ve presented my own research before, but helping others present theirs taught me a bit more about the process. Here are some tips I learned that may help you with your next research presentation:

More is more

In general, your presentation will always benefit from more practice, more feedback, and more revision. By practicing in front of friends, you can get comfortable with presenting your work while receiving feedback. It is hard to know how to revise your presentation if you never practice. If you are presenting to a general audience, getting feedback from someone outside of your discipline is crucial. Terms and ideas that seem intuitive to you may be completely foreign to someone else, and your well-crafted presentation could fall flat.

Less is more

Limit the scope of your presentation, the number of slides, and the text on each slide. In my experience, text works well for organizing slides, orienting the audience to key terms, and annotating important figures–not for explaining complex ideas. Having fewer slides is usually better as well. In general, about one slide per minute of presentation is an appropriate budget. Too many slides is usually a sign that your topic is too broad.

Limit the scope of your presentation

Don’t present your paper. Presentations are usually around 10 min long. You will not have time to explain all of the research you did in a semester (or a year!) in such a short span of time. Instead, focus on the highlight(s). Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

You will not have time to explain all of the research you did. Instead, focus on the highlights. Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

Craft a compelling research narrative

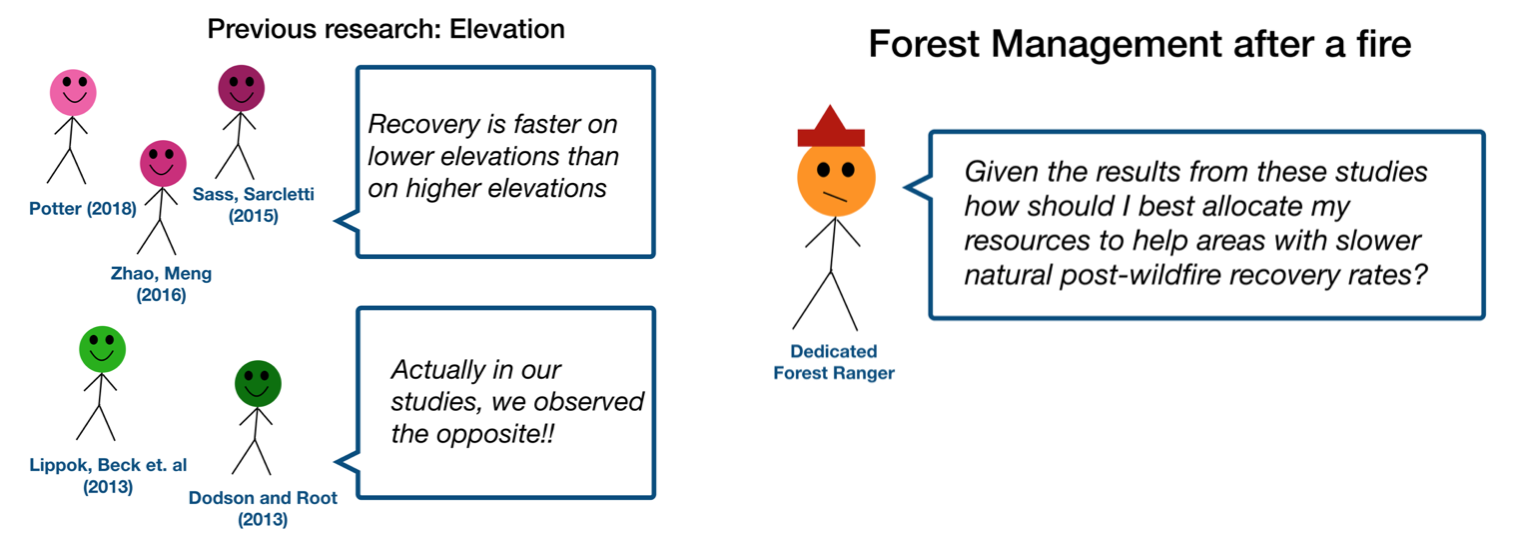

After identifying the focused research question, walk your audience through your research as if it were a story. Presentations with strong narrative arcs are clear, captivating, and compelling.

- Introduction (exposition — rising action)

Orient the audience and draw them in by demonstrating the relevance and importance of your research story with strong global motive. Provide them with the necessary vocabulary and background knowledge to understand the plot of your story. Introduce the key studies (characters) relevant in your story and build tension and conflict with scholarly and data motive. By the end of your introduction, your audience should clearly understand your research question and be dying to know how you resolve the tension built through motive.

- Methods (rising action)

The methods section should transition smoothly and logically from the introduction. Beware of presenting your methods in a boring, arc-killing, ‘this is what I did.’ Focus on the details that set your story apart from the stories other people have already told. Keep the audience interested by clearly motivating your decisions based on your original research question or the tension built in your introduction.

- Results (climax)

Less is usually more here. Only present results which are clearly related to the focused research question you are presenting. Make sure you explain the results clearly so that your audience understands what your research found. This is the peak of tension in your narrative arc, so don’t undercut it by quickly clicking through to your discussion.

- Discussion (falling action)

By now your audience should be dying for a satisfying resolution. Here is where you contextualize your results and begin resolving the tension between past research. Be thorough. If you have too many conflicts left unresolved, or you don’t have enough time to present all of the resolutions, you probably need to further narrow the scope of your presentation.

- Conclusion (denouement)

Return back to your initial research question and motive, resolving any final conflicts and tying up loose ends. Leave the audience with a clear resolution of your focus research question, and use unresolved tension to set up potential sequels (i.e. further research).

Use your medium to enhance the narrative

Visual presentations should be dominated by clear, intentional graphics. Subtle animation in key moments (usually during the results or discussion) can add drama to the narrative arc and make conflict resolutions more satisfying. You are narrating a story written in images, videos, cartoons, and graphs. While your paper is mostly text, with graphics to highlight crucial points, your slides should be the opposite. Adapting to the new medium may require you to create or acquire far more graphics than you included in your paper, but it is necessary to create an engaging presentation.

The most important thing you can do for your presentation is to practice and revise. Bother your friends, your roommates, TAs–anybody who will sit down and listen to your work. Beyond that, think about presentations you have found compelling and try to incorporate some of those elements into your own. Remember you want your work to be comprehensible; you aren’t creating experts in 10 minutes. Above all, try to stay passionate about what you did and why. You put the time in, so show your audience that it’s worth it.

For more insight into research presentations, check out these past PCUR posts written by Emma and Ellie .

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Narrative Analysis 101

Everything you need to know to get started

By: Ethar Al-Saraf (PhD)| Expert Reviewed By: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | March 2023

If you’re new to research, the host of qualitative analysis methods available to you can be a little overwhelming. In this post, we’ll unpack the sometimes slippery topic of narrative analysis . We’ll explain what it is, consider its strengths and weaknesses , and look at when and when not to use this analysis method.

Overview: Narrative Analysis

- What is narrative analysis (simple definition)

- The two overarching approaches

- The strengths & weaknesses of narrative analysis

- When (and when not) to use it

- Key takeaways

What Is Narrative Analysis?

Simply put, narrative analysis is a qualitative analysis method focused on interpreting human experiences and motivations by looking closely at the stories (the narratives) people tell in a particular context.

In other words, a narrative analysis interprets long-form participant responses or written stories as data, to uncover themes and meanings . That data could be taken from interviews, monologues, written stories, or even recordings. In other words, narrative analysis can be used on both primary and secondary data to provide evidence from the experiences described.

That’s all quite conceptual, so let’s look at an example of how narrative analysis could be used.

Let’s say you’re interested in researching the beliefs of a particular author on popular culture. In that case, you might identify the characters , plotlines , symbols and motifs used in their stories. You could then use narrative analysis to analyse these in combination and against the backdrop of the relevant context.

This would allow you to interpret the underlying meanings and implications in their writing, and what they reveal about the beliefs of the author. In other words, you’d look to understand the views of the author by analysing the narratives that run through their work.

The Two Overarching Approaches

Generally speaking, there are two approaches that one can take to narrative analysis. Specifically, an inductive approach or a deductive approach. Each one will have a meaningful impact on how you interpret your data and the conclusions you can draw, so it’s important that you understand the difference.

First up is the inductive approach to narrative analysis.

The inductive approach takes a bottom-up view , allowing the data to speak for itself, without the influence of any preconceived notions . With this approach, you begin by looking at the data and deriving patterns and themes that can be used to explain the story, as opposed to viewing the data through the lens of pre-existing hypotheses, theories or frameworks. In other words, the analysis is led by the data.

For example, with an inductive approach, you might notice patterns or themes in the way an author presents their characters or develops their plot. You’d then observe these patterns, develop an interpretation of what they might reveal in the context of the story, and draw conclusions relative to the aims of your research.

Contrasted to this is the deductive approach.

With the deductive approach to narrative analysis, you begin by using existing theories that a narrative can be tested against . Here, the analysis adopts particular theoretical assumptions and/or provides hypotheses, and then looks for evidence in a story that will either verify or disprove them.

For example, your analysis might begin with a theory that wealthy authors only tell stories to get the sympathy of their readers. A deductive analysis might then look at the narratives of wealthy authors for evidence that will substantiate (or refute) the theory and then draw conclusions about its accuracy, and suggest explanations for why that might or might not be the case.

Which approach you should take depends on your research aims, objectives and research questions . If these are more exploratory in nature, you’ll likely take an inductive approach. Conversely, if they are more confirmatory in nature, you’ll likely opt for the deductive approach.

Need a helping hand?

Strengths & Weaknesses

Now that we have a clearer view of what narrative analysis is and the two approaches to it, it’s important to understand its strengths and weaknesses , so that you can make the right choices in your research project.

A primary strength of narrative analysis is the rich insight it can generate by uncovering the underlying meanings and interpretations of human experience. The focus on an individual narrative highlights the nuances and complexities of their experience, revealing details that might be missed or considered insignificant by other methods.

Another strength of narrative analysis is the range of topics it can be used for. The focus on human experience means that a narrative analysis can democratise your data analysis, by revealing the value of individuals’ own interpretation of their experience in contrast to broader social, cultural, and political factors.

All that said, just like all analysis methods, narrative analysis has its weaknesses. It’s important to understand these so that you can choose the most appropriate method for your particular research project.

The first drawback of narrative analysis is the problem of subjectivity and interpretation . In other words, a drawback of the focus on stories and their details is that they’re open to being understood differently depending on who’s reading them. This means that a strong understanding of the author’s cultural context is crucial to developing your interpretation of the data. At the same time, it’s important that you remain open-minded in how you interpret your chosen narrative and avoid making any assumptions .

A second weakness of narrative analysis is the issue of reliability and generalisation . Since narrative analysis depends almost entirely on a subjective narrative and your interpretation, the findings and conclusions can’t usually be generalised or empirically verified. Although some conclusions can be drawn about the cultural context, they’re still based on what will almost always be anecdotal data and not suitable for the basis of a theory, for example.

Last but not least, the focus on long-form data expressed as stories means that narrative analysis can be very time-consuming . In addition to the source data itself, you will have to be well informed on the author’s cultural context as well as other interpretations of the narrative, where possible, to ensure you have a holistic view. So, if you’re going to undertake narrative analysis, make sure that you allocate a generous amount of time to work through the data.

When To Use Narrative Analysis

As a qualitative method focused on analysing and interpreting narratives describing human experiences, narrative analysis is usually most appropriate for research topics focused on social, personal, cultural , or even ideological events or phenomena and how they’re understood at an individual level.

For example, if you were interested in understanding the experiences and beliefs of individuals suffering social marginalisation, you could use narrative analysis to look at the narratives and stories told by people in marginalised groups to identify patterns , symbols , or motifs that shed light on how they rationalise their experiences.

In this example, narrative analysis presents a good natural fit as it’s focused on analysing people’s stories to understand their views and beliefs at an individual level. Conversely, if your research was geared towards understanding broader themes and patterns regarding an event or phenomena, analysis methods such as content analysis or thematic analysis may be better suited, depending on your research aim .

Let’s recap

In this post, we’ve explored the basics of narrative analysis in qualitative research. The key takeaways are:

- Narrative analysis is a qualitative analysis method focused on interpreting human experience in the form of stories or narratives .

- There are two overarching approaches to narrative analysis: the inductive (exploratory) approach and the deductive (confirmatory) approach.

- Like all analysis methods, narrative analysis has a particular set of strengths and weaknesses .

- Narrative analysis is generally most appropriate for research focused on interpreting individual, human experiences as expressed in detailed , long-form accounts.

If you’d like to learn more about narrative analysis and qualitative analysis methods in general, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach blog here . Alternatively, if you’re looking for hands-on help with your project, take a look at our 1-on-1 private coaching service .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

Thanks. I need examples of narrative analysis

Here are some examples of research topics that could utilise narrative analysis:

Personal Narratives of Trauma: Analysing personal stories of individuals who have experienced trauma to understand the impact, coping mechanisms, and healing processes.

Identity Formation in Immigrant Communities: Examining the narratives of immigrants to explore how they construct and negotiate their identities in a new cultural context.

Media Representations of Gender: Analysing narratives in media texts (such as films, television shows, or advertisements) to investigate the portrayal of gender roles, stereotypes, and power dynamics.

Where can I find an example of a narrative analysis table ?

Please i need help with my project,

how can I cite this article in APA 7th style?

please mention the sources as well.

My research is mixed approach. I use interview,key_inforamt interview,FGD and document.so,which qualitative analysis is appropriate to analyze these data.Thanks

Which qualitative analysis methode is appropriate to analyze data obtain from intetview,key informant intetview,Focus group discussion and document.

I’ve finished my PhD. Now I need a “platform” that will help me objectively ascertain the tacit assumptions that are buried within a narrative. Can you help?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 2: Handling Qualitative Data

- Handling qualitative data

- Transcripts

- Field notes

- Survey data and responses

- Visual and audio data

- Data organization

- Data coding

- Coding frame

- Auto and smart coding

- Organizing codes

- Qualitative data analysis

- Content analysis

Thematic analysis

- Thematic analysis vs. content analysis

- Introduction

Types of narrative research

Research methods for a narrative analysis, narrative analysis, considerations for narrative analysis.

- Phenomenological research

- Discourse analysis

- Grounded theory

- Deductive reasoning

- Inductive reasoning

- Inductive vs. deductive reasoning

- Qualitative data interpretation

- Qualitative analysis software

Narrative analysis in research

Narrative analysis is an approach to qualitative research that involves the documentation of narratives both for the purpose of understanding events and phenomena and understanding how people communicate stories.

Let's look at the basics of narrative research, then examine the process of conducting a narrative inquiry and how ATLAS.ti can help you conduct a narrative analysis.

Qualitative researchers can employ various forms of narrative research, but all of these distinct approaches utilize perspectival data as the means for contributing to theory.

A biography is the most straightforward form of narrative research. Data collection for a biography generally involves summarizing the main points of an individual's life or at least the part of their history involved with events that a researcher wants to examine. Generally speaking, a biography aims to provide a more complete record of an individual person's life in a manner that might dispel any inaccuracies that exist in popular thought or provide a new perspective on that person’s history. Narrative researchers may also construct a new biography of someone who doesn’t have a public or online presence to delve deeper into that person’s history relating to the research topic.

The purpose of biographies as a function of narrative inquiry is to shed light on the lived experience of a particular person that a more casual examination of someone's life might overlook. Newspaper articles and online posts might give someone an overview of information about any individual. At the same time, a more involved survey or interview can provide sufficiently comprehensive knowledge about a person useful for narrative analysis and theoretical development.

Life history

This is probably the most involved form of narrative research as it requires capturing as much of the total human experience of an individual person as possible. While it involves elements of biographical research, constructing a life history also means collecting first-person knowledge from the subject through narrative interviews and observations while drawing on other forms of data , such as field notes and in-depth interviews with others.

Even a newspaper article or blog post about the person can contribute to the contextual meaning informing the life history. The objective of conducting a life history is to construct a complete picture of the person from past to present in a manner that gives your research audience the means to immerse themselves in the human experience of the person you are studying.

Oral history

While all forms of narrative research rely on narrative interviews with research participants, oral histories begin with and branch out from the individual's point of view as the driving force of data collection .

Major events like wars and natural disasters are often observed and described at scale, but a bird's eye view of such events may not provide a complete story. Oral history can assist researchers in providing a unique and perhaps unexplored perspective from in-depth interviews with a narrator's own words of what happened, how they experienced it, and what reasons they give for their actions. Researchers who collect this sort of information can then help fill in the gaps common knowledge may not have grasped.

The objective of an oral history is to provide a perspective built on personal experience. The unique viewpoint that personal narratives can provide has the potential to raise analytical insights that research methods at scale may overlook. Narrative analysis of oral histories can hence illuminate potential inquiries that can be addressed in future studies.

Whatever your research, get it done with ATLAS.ti.

From case study research to interviews, turn to ATLAS.ti for your qualitative research. Click here for a free trial.

To conduct narrative analysis, researchers need a narrative and research question . A narrative alone might make for an interesting story that instills information, but analyzing a narrative to generate knowledge requires ordering that information to identify patterns, intentions, and effects.

Narrative analysis presents a distinctive research approach among various methodologies , and it can pose significant challenges due to its inherent interpretative nature. Essentially, this method revolves around capturing and examining the verbal or written accounts and visual depictions shared by individuals. Narrative inquiry strives to unravel the essence of what is conveyed by closely observing the content and manner of expression.

Furthermore, narrative research assumes a dual role, serving both as a research technique and a subject of investigation. Regarded as "real-world measures," narrative methods provide valuable tools for exploring actual societal issues. The narrative approach encompasses an individual's life story and the profound significance embedded within their lived experiences. Typically, a composite of narratives is synthesized, intermingling and mutually influencing each other.

Designing a research inquiry

Sometimes, narrative research is less about the storyteller or the story they are telling than it is about generating knowledge that contributes to a greater understanding of social behavior and cultural practices. While it might be interesting or useful to hear a comedian tell a story that makes their audience laugh, a narrative analysis of that story can identify how the comedian constructs their narrative or what causes the audience to laugh.

As with all research, a narrative inquiry starts with a research question that is tied to existing relevant theory regarding the object of analysis (i.e., the person or event for which the narrative is constructed). If your research question involves studying racial inequalities in university contexts, for example, then the narrative analysis you are seeking might revolve around the lived experiences of students of color. If you are analyzing narratives from children's stories, then your research question might relate to identifying aspects of children's stories that grab the attention of young readers. The point is that researchers conducting a narrative inquiry do not do so merely to collect more information about their object of inquiry. Ultimately, narrative research is tied to developing a more contextualized or broader understanding of the social world.

Data collection

Having crafted the research questions and chosen the appropriate form of narrative research for your study, you can start to collect your data for the eventual narrative analysis.

Needless to say, the key point in narrative research is the narrative. The story is either the unit of analysis or the focal point from which researchers pursue other methods of research. Interviews and observations are great ways to collect narratives. Particularly with biographies and life histories, one of the best ways to study your object of inquiry is to interview them. If you are conducting narrative research for discourse analysis, then observing or recording narratives (e.g., storytelling, audiobooks, podcasts) is ideal for later narrative analysis.

Triangulating data

If you are collecting a life history or an oral history, then you will need to rely on collecting evidence from different sources to support the analysis of the narrative. In research, triangulation is the concept of drawing on multiple methods or sources of data to get a more comprehensive picture of your object of inquiry.

While a narrative inquiry is constructed around the story or its storyteller, assertions that can be made from an analysis of the story can benefit from supporting evidence (or lack thereof) collected by other means.

Even a lack of supporting evidence might be telling. For example, suppose your object of inquiry tells a story about working minimum wage jobs all throughout college to pay for their tuition. Looking for triangulation, in this case, means searching through records and other forms of information to support the claims being put forth. If it turns out that the storyteller's claims bear further warranting - maybe you discover that family or scholarships supported them during college - your analysis might uncover new inquiries as to why the story was presented the way it was. Perhaps they are trying to impress their audience or construct a narrative identity about themselves that reinforces their thinking about who they are. The important point here is that triangulation is a necessary component of narrative research to learn more about the object of inquiry from different angles.

Conduct data analysis for your narrative research with ATLAS.ti.

Dedicated research software like ATLAS.ti helps the researcher catalog, penetrate, and analyze the data generated in any qualitative research project. Start with a free trial today.

This brings us to the analysis part of narrative research. As explained above, a narrative can be viewed as a straightforward story to understand and internalize. As researchers, however, we have many different approaches available to us for analyzing narrative data depending on our research inquiry.

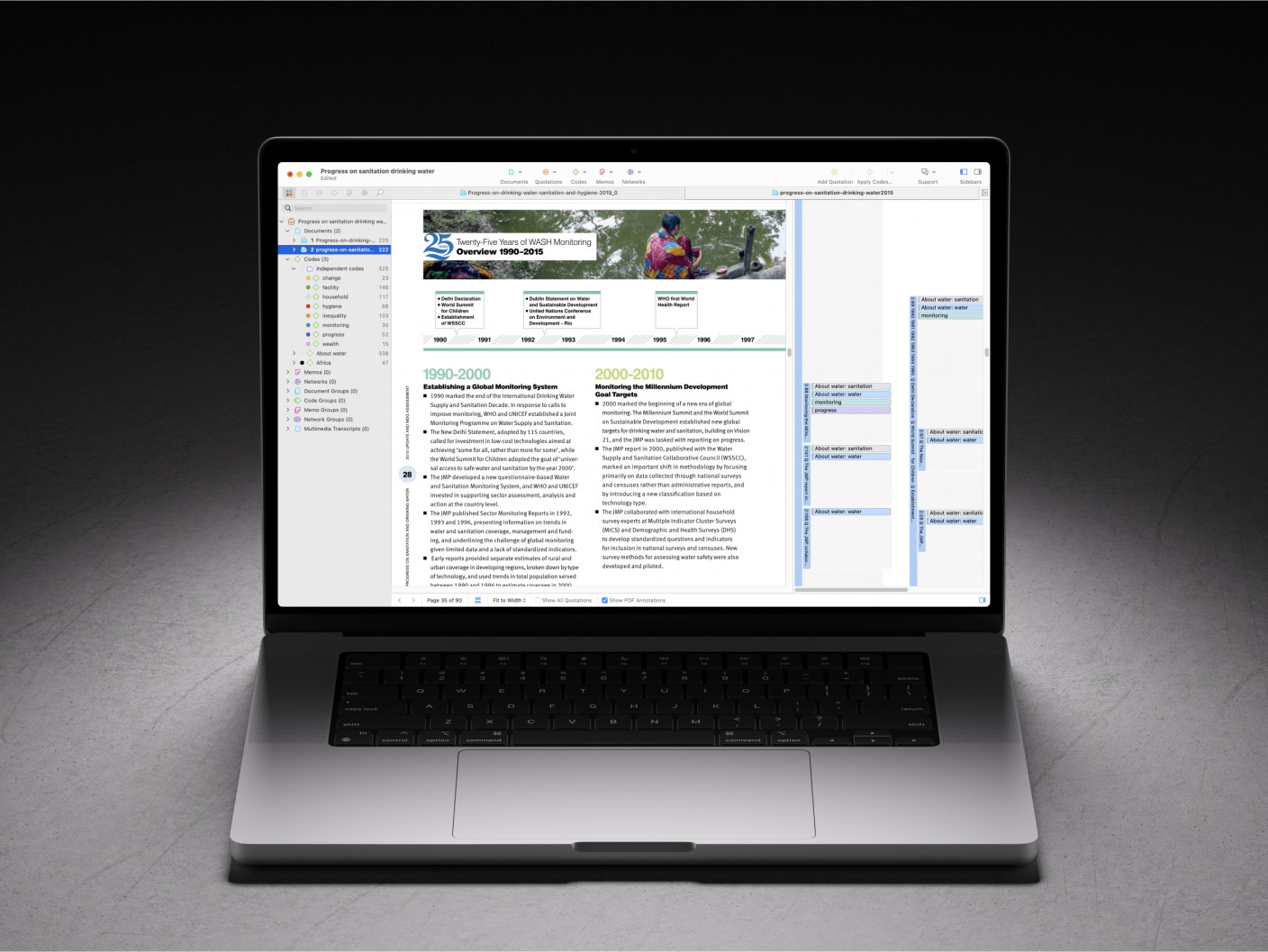

In this section, we will examine some of the most common forms of analysis while looking at how you can employ tools in ATLAS.ti to analyze your qualitative data .

Qualitative research often employs thematic analysis , which refers to a search for commonly occurring themes that appear in the data. The important point of thematic analysis in narrative research is that the themes arise from the data produced by the research participants. In other words, the themes in a narrative study are strongly based on how the research participants see them rather than focusing on how researchers or existing theory see them.

ATLAS.ti can be used for thematic analysis in any research field or discipline. Data in narrative research is summarized through the coding process , where the researcher codes large segments of data with short, descriptive labels that can succinctly describe the data thematically. The emerging patterns among occurring codes in the perspectival data thus inform the identification of themes that arise from the collected narratives.

Structural analysis

The search for structure in a narrative is less about what is conveyed in the narrative and more about how the narrative is told. The differences in narrative forms ultimately tell us something useful about the meaning-making epistemologies and values of the people telling them and the cultures they inhabit.

Just like in thematic analysis, codes in ATLAS.ti can be used to summarize data, except that in this case, codes could be created to specifically examine structure by identifying the particular parts or moves in a narrative (e.g., introduction, conflict, resolution). Code-Document Analysis in ATLAS.ti can then tell you which of your narratives (represented by discrete documents) contain which parts of a common narrative.

It may also be useful to conduct a content analysis of narratives to analyze them structurally. English has many signal words and phrases (e.g., "for example," "as a result," and "suddenly") to alert listeners and readers that they are coming to a new step in the narrative.

In this case, both the Text Search and Word Frequencies tools in ATLAS.ti can help you identify the various aspects of the narrative structure (including automatically identifying discrete parts of speech) and the frequency in which they occur across different narratives.

Functional analysis

Whereas a straightforward structural analysis identifies the particular parts of a narrative, a functional analysis looks at what the narrator is trying to accomplish through the content and structure of their narrative. For example, if a research participant telling their narrative asks the interviewer rhetorical questions, they might be doing so to make the interviewer think or adopt the participant's perspective.

A functional analysis often requires the researcher to take notes and reflect on their experiences while collecting data from research participants. ATLAS.ti offers a dedicated space for memos , which can serve to jot down useful contextual information that the researcher can refer to while coding and analyzing data.

Dialogic analysis

There is a nuanced difference between what a narrator tries to accomplish when telling a narrative and how the listener is affected by the narrative. There may be an overlap between the two, but the extent to which a narrative might resonate with people can give us useful insights about a culture or society.

The topic of humor is one such area that can benefit from dialogic analysis, considering that there are vast differences in how cultures perceive humor in terms of how a joke is constructed or what cultural references are required to understand a joke.

Imagine that you are analyzing a reading of a children's book in front of an audience of children at a library. If it is supposed to be funny, how do you determine what parts of the book are funny and why?

The coding process in ATLAS.ti can help with dialogic analysis of a transcript from that reading. In such an analysis, you can have two sets of codes, one for thematically summarizing the elements of the book reading and one for marking when the children laugh.

The Code Co-Occurrence Analysis tool can then tell you which codes occur during the times that there is laughter, giving you a sense of what parts of a children's narrative might be funny to its audience.

Narrative analysis and research hold immense significance within the realm of social science research, contributing a distinct and valuable approach. Whether employed as a component of a comprehensive presentation or pursued as an independent scholarly endeavor, narrative research merits recognition as a distinctive form of research and interpretation in its own right.

Subjectivity in narratives

It is crucial to acknowledge that every narrative is intricately intertwined with its cultural milieu and the subjective experiences of the storyteller. While the outcomes of research are undoubtedly influenced by the individual narratives involved, a conscientious adherence to narrative methodology and a critical reflection on one's research can foster transparent and rigorous investigations, minimizing the potential for misunderstandings.

Rather than striving to perceive narratives through an objective lens, it is imperative to contextualize them within their sociocultural fabric. By doing so, an analysis can embrace the diverse array of narratives and enable multiple perspectives to illuminate a phenomenon or story. Embracing such complexity, narrative methodologies find considerable application in social science research.

Connecting narratives to broader phenomena

In employing narrative analysis, researchers delve into the intricate tapestry of personal narratives, carefully considering the multifaceted interplay between individual experiences and broader societal dynamics.

This meticulous approach fosters a deeper understanding of the intricate web of meanings that shape the narratives under examination. Consequently, researchers can uncover rich insights and discern patterns that may have remained hidden otherwise. These can provide valuable contributions to both theory and practice.

In summary, narrative analysis occupies a vital position within social science research. By appreciating the cultural embeddedness of narratives, employing a thoughtful methodology, and critically reflecting on one's research, scholars can conduct robust investigations that shed light on the complexities of human experiences while avoiding potential pitfalls and fostering a nuanced understanding of the narratives explored.

Turn to ATLAS.ti for your narrative analysis.

Researchers can rely on ATLAS.ti for conducting qualitative research. See why with a free trial.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER GUIDE

- 01 December 2021

How to tell a compelling story in scientific presentations

- Bruce Kirchoff 0

Bruce Kirchoff is a botanist and storyteller at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro in North Carolina, USA. His new book is Presenting Science Concisely .

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Structuring your presentations with care can help you to clearly communicate to your audience. Credit: Getty

Scientific presentations are too often boring and ineffective. Their focus on techniques and data do not make it easy for the audience to understand the main point of the research.

If you want to reach beyond the narrow group of scientists who work in your specific area, you need to tell your audience members why they should be interested. Three things can help you to be engaging and convey the importance of your research to a wide audience. I had been teaching scientific communication for several years when I was approached to write a book about improving scientific presentations 1 . These are my three most important tips.

State your main finding in your title

The best titles get straight to the point. They tell the audience what you found, and they let them know what your talk will be about. Throughout this article, I will use titles from Nature papers published in the past two years as examples that will stand in for presentation titles. This is because Nature articles have a similar goal of attempting to make discipline-specific research available to a broader audience of scientists. Take, for example: ‘Supply chain diversity buffers cities against food shocks’ 2 .

A great title tells the reader exactly what’s new and precisely conveys the main result, as this one demonstrates. A more conventional title would have been ‘Effect of supply chain diversity on food shocks’, which omits the direction of the effect — so mainly scientists who are interested in your research area will be attracted to the talk. Others will wonder whether the talk will be a waste of time: maybe there was no effect at all.

Collection: Careers toolkit

Another example of a good title is: ‘Organic management promotes natural pest control through altered plant resistance to insects’ 3 .

This title ensures that the audience members know that the talk will be about the beneficial effects of organic crop management before they hear it. They also know that organic management increases plant resistance to insects. This title is much better than one such as: ‘Effects of organic pest management on plant insect resistance’. This title tells the audience the general area of the talk but does not give them the main result.

Finally, look at: ‘A highly magnetized and rapidly rotating white dwarf as small as the Moon’ 4 .

Good titles can just as easily be written for descriptive work as for experimental results. All you need to do is tell your audience what you found. Be as specific as possible. Compare this title with a more conventional one for the same work: ‘Use of the Zwicky Transient Facility to search for short period objects below the main white dwarf cooling sequence’. This title might be of interest to astronomers interested in using this facility, but is unlikely to attract anyone beyond them.

‘But’ is good — use it for dramatic effect

The contradiction implied by the word ‘but’ is one of the most powerful tools a scientist can use 5 . Contradictions introduce problems and provide dramatic effect, tension and a reason to keep listening.

Without such contradictions, the talk will consist of a bunch of results strung together in a seemingly endless and mind-numbing list. We can think of this list as a series of ‘and’ statements: “We did this and this and ran this experiment and found this result and . . . and . . . and.”

Contrast this with a structure that begins with a few important facts, tethered by ands, and then introduces the problem to be solved. Finally, ‘therefore’ can introduce results or subsequent actions. That structure would look like this: ‘X is the current state of knowledge, and we know Y. But Z problem remains. Therefore, we carried out ABC research.’ The introduction of even one contradiction wakes up people in the audience and helps them to focus on the results.

Collection: Conferences

A paper published earlier this year on SARS-CoV-2 and host protein synthesis provides an excellent example of the narrative form using ‘and’, ‘but’ and ‘therefore’ 6 . In the example below, I have shortened the abstract and simplified the transitions, but maintained the authors’ original structure 6 . Although they did not use ‘but’ or ‘therefore’ in their abstract, the existence of these terms is clearly implied. I have made them explicit in the following rendition.

“Coronaviruses have developed a variety of mechanisms to repress host messenger RNA translation and to allow the translation of viral mRNA and block the cellular immune response. But a comprehensive picture of the effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on cellular gene expression is lacking. Therefore, we combine RNA sequencing, ribosome profiling and metabolic labelling of newly synthesized RNA to comprehensively define the mechanisms that are used by SARS-CoV-2 to shut off cellular protein synthesis.”

In this example, background information is given in the first sentence, linked by a series of conjunctions. Then the problem is introduced — this is the contradiction that comes with ‘but’. The solution to this problem is given in the next sentence (and introduced by using ‘therefore’). This structure makes the text interesting. It will do the same for your presentations.

Use repeated problems and solutions to create a story

Use the power of contradiction to maintain audience engagement throughout your talk. You can string together a series of problems and solutions (buts and therefores) to create a story that leads to your main result. The result highlighted in your title will help you to focus your talk so that the solutions you present lead to this overarching result.

Here is the general pattern:

1. Present the first part of your results.

2. Introduce a problem that remains.

3. Provide a solution to this problem by presenting more results.

4. Introduce the next problem.

5. Present the results that address this problem.

6. Continue this ‘problem and solution’ process through your presentation.

7. End by restating your main finding and summarize how it arises from your intermediate results.

The SARS-CoV-2 abstract 6 uses this pattern of repeated problems (buts) and solutions (therefores). I have modified the wording to clarify these sections.

1. Result 1: SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to a global reduction in translation, but we found that viral transcripts are not preferentially translated.

2. Problem 1: How then does viral mRNA comes to dominate the mRNA pool?

3. Solution 1: Accelerated degradation of cytosolic cellular mRNAs facilitates viral takeover of the mRNA pool in infected cells.

4. Problem 2: How is the translation of induced transcripts affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection?

5. Solution 2: The translation of induced transcripts (including innate immune genes) is impaired.

6. Problem 3: How is translation impaired? What is the mechanism?

7. Solution 3: Impairment is probably mediated by inhibiting the export of nuclear mRNA from the nucleus, which prevents newly transcribed cellular mRNA from accessing ribosomes.

8. Final summary: Our results demonstrate a multipronged strategy used by SARS-CoV-2 to take over the translation machinery and suppress host defences.

Using these three basic tips, you can create engaging presentations that will hold the attention of your audience and help them to remember you. For young scientists, especially, that is the most important thing the audience can take away from your talk.

Nature 600 , S88-S89 (2021)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-03603-2

This article is part of Nature Events Guide , an editorially independent supplement. Advertisers have no influence over the content.

This is an article from the Nature Careers Community, a place for Nature readers to share their professional experiences and advice. Guest posts are encouraged .

Kirchoff, B. Presenting Science Concisely (CABI, 2021).

Google Scholar

Gomez, M., Mejia, A., Ruddell, B. L. & Rushforth, R. R. Nature 595 , 250–254 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

Blundell, R. et al. Nature Plants 6 , 483–491 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Caiazzo, I. et al. Nature 595 , 39–42 (2021).

Olson, R. The Narrative Gym (Prairie Starfish Press, 2020).

Finkel, Y. et al. Nature 594 , 240–245 (2021).

Download references

Competing Interests

B.K. receives royalties for his book, which this article is based on.

Related Articles

Partner content: Scientific Conferences to fuel new ideas and the next generation of scientists

Partner content: Wellcome Connecting Science: A global provider of genomics learning and training

- Conferences and meetings

How I run a virtual lab group that’s collaborative, inclusive and productive

Career Column 31 MAY 24

Defying the stereotype of Black resilience

Career Q&A 30 MAY 24

How I overcame my stage fright in the lab

Career Column 30 MAY 24

Researcher parents are paying a high price for conference travel — here’s how to fix it

Career Column 27 MAY 24

China promises more money for science in 2024

News 08 MAR 24

One-third of Indian STEM conferences have no women

News 15 NOV 23

Associate Editor, High-energy physics

As an Associate Editor, you will independently handle all phases of the peer review process and help decide what will be published.

Homeworking

American Physical Society

Postdoctoral Fellowships: Immuno-Oncology

We currently have multiple postdoctoral fellowship positions available within our multidisciplinary research teams based In Hong Kong.

Hong Kong (HK)

Centre for Oncology and Immunology

Chief Editor

Job Title: Chief Editor Organisation: Nature Ecology & Evolution Location: New York, Berlin or Heidelberg - Hybrid working Closing date: June 23rd...

New York City, New York (US)

Springer Nature Ltd

Global Talent Recruitment (Scientist Positions)

Global Talent Gathering for Innovation, Changping Laboratory Recruiting Overseas High-Level Talents.

Beijing, China

Changping Laboratory

Postdoctoral Associate - Amyloid Strain Differences in Alzheimer's Disease

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to make a scientific presentation

Scientific presentation outlines

Questions to ask yourself before you write your talk, 1. how much time do you have, 2. who will you speak to, 3. what do you want the audience to learn from your talk, step 1: outline your presentation, step 2: plan your presentation slides, step 3: make the presentation slides, slide design, text elements, animations and transitions, step 4: practice your presentation, final thoughts, frequently asked questions about preparing scientific presentations, related articles.

A good scientific presentation achieves three things: you communicate the science clearly, your research leaves a lasting impression on your audience, and you enhance your reputation as a scientist.

But, what is the best way to prepare for a scientific presentation? How do you start writing a talk? What details do you include, and what do you leave out?

It’s tempting to launch into making lots of slides. But, starting with the slides can mean you neglect the narrative of your presentation, resulting in an overly detailed, boring talk.

The key to making an engaging scientific presentation is to prepare the narrative of your talk before beginning to construct your presentation slides. Planning your talk will ensure that you tell a clear, compelling scientific story that will engage the audience.

In this guide, you’ll find everything you need to know to make a good oral scientific presentation, including:

- The different types of oral scientific presentations and how they are delivered;

- How to outline a scientific presentation;

- How to make slides for a scientific presentation.

Our advice results from delving into the literature on writing scientific talks and from our own experiences as scientists in giving and listening to presentations. We provide tips and best practices for giving scientific talks in a separate post.

There are two main types of scientific talks:

- Your talk focuses on a single study . Typically, you tell the story of a single scientific paper. This format is common for short talks at contributed sessions in conferences.

- Your talk describes multiple studies. You tell the story of multiple scientific papers. It is crucial to have a theme that unites the studies, for example, an overarching question or problem statement, with each study representing specific but different variations of the same theme. Typically, PhD defenses, invited seminars, lectures, or talks for a prospective employer (i.e., “job talks”) fall into this category.

➡️ Learn how to prepare an excellent thesis defense

The length of time you are allotted for your talk will determine whether you will discuss a single study or multiple studies, and which details to include in your story.

The background and interests of your audience will determine the narrative direction of your talk, and what devices you will use to get their attention. Will you be speaking to people specializing in your field, or will the audience also contain people from disciplines other than your own? To reach non-specialists, you will need to discuss the broader implications of your study outside your field.

The needs of the audience will also determine what technical details you will include, and the language you will use. For example, an undergraduate audience will have different needs than an audience of seasoned academics. Students will require a more comprehensive overview of background information and explanations of jargon but will need less technical methodological details.

Your goal is to speak to the majority. But, make your talk accessible to the least knowledgeable person in the room.

This is called the thesis statement, or simply the “take-home message”. Having listened to your talk, what message do you want the audience to take away from your presentation? Describe the main idea in one or two sentences. You want this theme to be present throughout your presentation. Again, the thesis statement will depend on the audience and the type of talk you are giving.

Your thesis statement will drive the narrative for your talk. By deciding the take-home message you want to convince the audience of as a result of listening to your talk, you decide how the story of your talk will flow and how you will navigate its twists and turns. The thesis statement tells you the results you need to show, which subsequently tells you the methods or studies you need to describe, which decides the angle you take in your introduction.

➡️ Learn how to write a thesis statement

The goal of your talk is that the audience leaves afterward with a clear understanding of the key take-away message of your research. To achieve that goal, you need to tell a coherent, logical story that conveys your thesis statement throughout the presentation. You can tell your story through careful preparation of your talk.

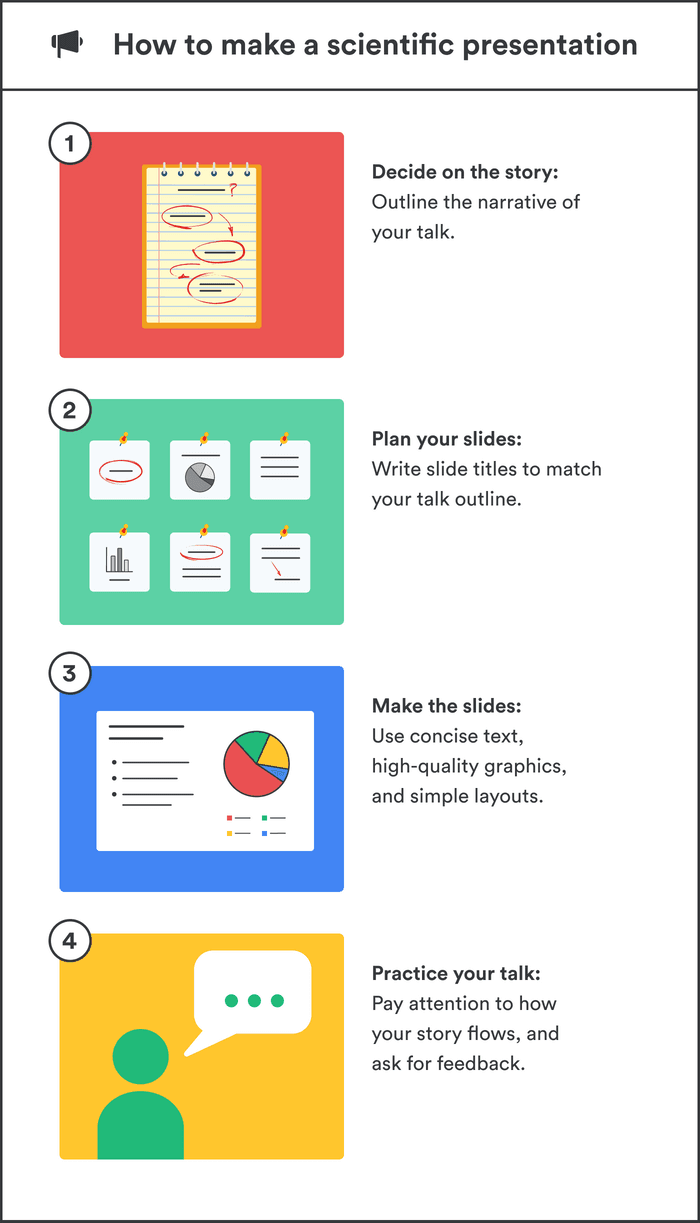

Preparation of a scientific presentation involves three separate stages: outlining the scientific narrative, preparing slides, and practicing your delivery. Making the slides of your talk without first planning what you are going to say is inefficient.

Here, we provide a 4 step guide to writing your scientific presentation:

- Outline your presentation

- Plan your presentation slides

- Make the presentation slides

- Practice your presentation

Writing an outline helps you consider the key pieces of your talk and how they fit together from the beginning, preventing you from forgetting any important details. It also means you avoid changing the order of your slides multiple times, saving you time.

Plan your talk as discrete sections. In the table below, we describe the sections for a single study talk vs. a talk discussing multiple studies:

The following tips apply when writing the outline of a single study talk. You can easily adapt this framework if you are writing a talk discussing multiple studies.

Introduction: Writing the introduction can be the hardest part of writing a talk. And when giving it, it’s the point where you might be at your most nervous. But preparing a good, concise introduction will settle your nerves.

The introduction tells the audience the story of why you studied your topic. A good introduction succinctly achieves four things, in the following order.

- It gives a broad perspective on the problem or topic for people in the audience who may be outside your discipline (i.e., it explains the big-picture problem motivating your study).

- It describes why you did the study, and why the audience should care.

- It gives a brief indication of how your study addressed the problem and provides the necessary background information that the audience needs to understand your work.

- It indicates what the audience will learn from the talk, and prepares them for what will come next.

A good introduction not only gives the big picture and motivations behind your study but also concisely sets the stage for what the audience will learn from the talk (e.g., the questions your work answers, and/or the hypotheses that your work tests). The end of the introduction will lead to a natural transition to the methods.

Give a broad perspective on the problem. The easiest way to start with the big picture is to think of a hook for the first slide of your presentation. A hook is an opening that gets the audience’s attention and gets them interested in your story. In science, this might take the form of a why, or a how question, or it could be a statement about a major problem or open question in your field. Other examples of hooks include quotes, short anecdotes, or interesting statistics.

Why should the audience care? Next, decide on the angle you are going to take on your hook that links to the thesis of your talk. In other words, you need to set the context, i.e., explain why the audience should care. For example, you may introduce an observation from nature, a pattern in experimental data, or a theory that you want to test. The audience must understand your motivations for the study.

Supplementary details. Once you have established the hook and angle, you need to include supplementary details to support them. For example, you might state your hypothesis. Then go into previous work and the current state of knowledge. Include citations of these studies. If you need to introduce some technical methodological details, theory, or jargon, do it here.

Conclude your introduction. The motivation for the work and background information should set the stage for the conclusion of the introduction, where you describe the goals of your study, and any hypotheses or predictions. Let the audience know what they are going to learn.

Methods: The audience will use your description of the methods to assess the approach you took in your study and to decide whether your findings are credible. Tell the story of your methods in chronological order. Use visuals to describe your methods as much as possible. If you have equations, make sure to take the time to explain them. Decide what methods to include and how you will show them. You need enough detail so that your audience will understand what you did and therefore can evaluate your approach, but avoid including superfluous details that do not support your main idea. You want to avoid the common mistake of including too much data, as the audience can read the paper(s) later.

Results: This is the evidence you present for your thesis. The audience will use the results to evaluate the support for your main idea. Choose the most important and interesting results—those that support your thesis. You don’t need to present all the results from your study (indeed, you most likely won’t have time to present them all). Break down complex results into digestible pieces, e.g., comparisons over multiple slides (more tips in the next section).

Summary: Summarize your main findings. Displaying your main findings through visuals can be effective. Emphasize the new contributions to scientific knowledge that your work makes.

Conclusion: Complete the circle by relating your conclusions to the big picture topic in your introduction—and your hook, if possible. It’s important to describe any alternative explanations for your findings. You might also speculate on future directions arising from your research. The slides that comprise your conclusion do not need to state “conclusion”. Rather, the concluding slide title should be a declarative sentence linking back to the big picture problem and your main idea.

It’s important to end well by planning a strong closure to your talk, after which you will thank the audience. Your closing statement should relate to your thesis, perhaps by stating it differently or memorably. Avoid ending awkwardly by memorizing your closing sentence.

By now, you have an outline of the story of your talk, which you can use to plan your slides. Your slides should complement and enhance what you will say. Use the following steps to prepare your slides.

- Write the slide titles to match your talk outline. These should be clear and informative declarative sentences that succinctly give the main idea of the slide (e.g., don’t use “Methods” as a slide title). Have one major idea per slide. In a YouTube talk on designing effective slides , researcher Michael Alley shows examples of instructive slide titles.

- Decide how you will convey the main idea of the slide (e.g., what figures, photographs, equations, statistics, references, or other elements you will need). The body of the slide should support the slide’s main idea.

- Under each slide title, outline what you want to say, in bullet points.

In sum, for each slide, prepare a title that summarizes its major idea, a list of visual elements, and a summary of the points you will make. Ensure each slide connects to your thesis. If it doesn’t, then you don’t need the slide.

Slides for scientific presentations have three major components: text (including labels and legends), graphics, and equations. Here, we give tips on how to present each of these components.

- Have an informative title slide. Include the names of all coauthors and their affiliations. Include an attractive image relating to your study.

- Make the foreground content of your slides “pop” by using an appropriate background. Slides that have white backgrounds with black text work well for small rooms, whereas slides with black backgrounds and white text are suitable for large rooms.

- The layout of your slides should be simple. Pay attention to how and where you lay the visual and text elements on each slide. It’s tempting to cram information, but you need lots of empty space. Retain space at the sides and bottom of your slides.

- Use sans serif fonts with a font size of at least 20 for text, and up to 40 for slide titles. Citations can be in 14 font and should be included at the bottom of the slide.

- Use bold or italics to emphasize words, not underlines or caps. Keep these effects to a minimum.

- Use concise text . You don’t need full sentences. Convey the essence of your message in as few words as possible. Write down what you’d like to say, and then shorten it for the slide. Remove unnecessary filler words.

- Text blocks should be limited to two lines. This will prevent you from crowding too much information on the slide.

- Include names of technical terms in your talk slides, especially if they are not familiar to everyone in the audience.

- Proofread your slides. Typos and grammatical errors are distracting for your audience.

- Include citations for the hypotheses or observations of other scientists.

- Good figures and graphics are essential to sustain audience interest. Use graphics and photographs to show the experiment or study system in action and to explain abstract concepts.

- Don’t use figures straight from your paper as they may be too detailed for your talk, and details like axes may be too small. Make new versions if necessary. Make them large enough to be visible from the back of the room.

- Use graphs to show your results, not tables. Tables are difficult for your audience to digest! If you must present a table, keep it simple.

- Label the axes of graphs and indicate the units. Label important components of graphics and photographs and include captions. Include sources for graphics that are not your own.

- Explain all the elements of a graph. This includes the axes, what the colors and markers mean, and patterns in the data.

- Use colors in figures and text in a meaningful, not random, way. For example, contrasting colors can be effective for pointing out comparisons and/or differences. Don’t use neon colors or pastels.

- Use thick lines in figures, and use color to create contrasts in the figures you present. Don’t use red/green or red/blue combinations, as color-blind audience members can’t distinguish between them.

- Arrows or circles can be effective for drawing attention to key details in graphs and equations. Add some text annotations along with them.

- Write your summary and conclusion slides using graphics, rather than showing a slide with a list of bullet points. Showing some of your results again can be helpful to remind the audience of your message.

- If your talk has equations, take time to explain them. Include text boxes to explain variables and mathematical terms, and put them under each term in the equation.

- Combine equations with a graphic that shows the scientific principle, or include a diagram of the mathematical model.

- Use animations judiciously. They are helpful to reveal complex ideas gradually, for example, if you need to make a comparison or contrast or to build a complicated argument or figure. For lists, reveal one bullet point at a time. New ideas appearing sequentially will help your audience follow your logic.

- Slide transitions should be simple. Silly ones distract from your message.

- Decide how you will make the transition as you move from one section of your talk to the next. For example, if you spend time talking through details, provide a summary afterward, especially in a long talk. Another common tactic is to have a “home slide” that you return to multiple times during the talk that reinforces your main idea or message. In her YouTube talk on designing effective scientific presentations , Stanford biologist Susan McConnell suggests using the approach of home slides to build a cohesive narrative.

To deliver a polished presentation, it is essential to practice it. Here are some tips.

- For your first run-through, practice alone. Pay attention to your narrative. Does your story flow naturally? Do you know how you will start and end? Are there any awkward transitions? Do animations help you tell your story? Do your slides help to convey what you are saying or are they missing components?

- Next, practice in front of your advisor, and/or your peers (e.g., your lab group). Ask someone to time your talk. Take note of their feedback and the questions that they ask you (you might be asked similar questions during your real talk).

- Edit your talk, taking into account the feedback you’ve received. Eliminate superfluous slides that don’t contribute to your takeaway message.

- Practice as many times as needed to memorize the order of your slides and the key transition points of your talk. However, don’t try to learn your talk word for word. Instead, memorize opening and closing statements, and sentences at key junctures in the presentation. Your presentation should resemble a serious but spontaneous conversation with the audience.

- Practicing multiple times also helps you hone the delivery of your talk. While rehearsing, pay attention to your vocal intonations and speed. Make sure to take pauses while you speak, and make eye contact with your imaginary audience.

- Make sure your talk finishes within the allotted time, and remember to leave time for questions. Conferences are particularly strict on run time.

- Anticipate questions and challenges from the audience, and clarify ambiguities within your slides and/or speech in response.

- If you anticipate that you could be asked questions about details but you don’t have time to include them, or they detract from the main message of your talk, you can prepare slides that address these questions and place them after the final slide of your talk.

➡️ More tips for giving scientific presentations

An organized presentation with a clear narrative will help you communicate your ideas effectively, which is essential for engaging your audience and conveying the importance of your work. Taking time to plan and outline your scientific presentation before writing the slides will help you manage your nerves and feel more confident during the presentation, which will improve your overall performance.

A good scientific presentation has an engaging scientific narrative with a memorable take-home message. It has clear, informative slides that enhance what the speaker says. You need to practice your talk many times to ensure you deliver a polished presentation.

First, consider who will attend your presentation, and what you want the audience to learn about your research. Tailor your content to their level of knowledge and interests. Second, create an outline for your presentation, including the key points you want to make and the evidence you will use to support those points. Finally, practice your presentation several times to ensure that it flows smoothly and that you are comfortable with the material.

Prepare an opening that immediately gets the audience’s attention. A common device is a why or a how question, or a statement of a major open problem in your field, but you could also start with a quote, interesting statistic, or case study from your field.

Scientific presentations typically either focus on a single study (e.g., a 15-minute conference presentation) or tell the story of multiple studies (e.g., a PhD defense or 50-minute conference keynote talk). For a single study talk, the structure follows the scientific paper format: Introduction, Methods, Results, Summary, and Conclusion, whereas the format of a talk discussing multiple studies is more complex, but a theme unifies the studies.

Ensure you have one major idea per slide, and convey that idea clearly (through images, equations, statistics, citations, video, etc.). The slide should include a title that summarizes the major point of the slide, should not contain too much text or too many graphics, and color should be used meaningfully.

Home Blog Presentation Ideas How to Create and Deliver a Research Presentation

How to Create and Deliver a Research Presentation

Every research endeavor ends up with the communication of its findings. Graduate-level research culminates in a thesis defense , while many academic and scientific disciplines are published in peer-reviewed journals. In a business context, PowerPoint research presentation is the default format for reporting the findings to stakeholders.

Condensing months of work into a few slides can prove to be challenging. It requires particular skills to create and deliver a research presentation that promotes informed decisions and drives long-term projects forward.

Table of Contents

What is a Research Presentation

Key slides for creating a research presentation, tips when delivering a research presentation, how to present sources in a research presentation, recommended templates to create a research presentation.

A research presentation is the communication of research findings, typically delivered to an audience of peers, colleagues, students, or professionals. In the academe, it is meant to showcase the importance of the research paper , state the findings and the analysis of those findings, and seek feedback that could further the research.

The presentation of research becomes even more critical in the business world as the insights derived from it are the basis of strategic decisions of organizations. Information from this type of report can aid companies in maximizing the sales and profit of their business. Major projects such as research and development (R&D) in a new field, the launch of a new product or service, or even corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives will require the presentation of research findings to prove their feasibility.

Market research and technical research are examples of business-type research presentations you will commonly encounter.

In this article, we’ve compiled all the essential tips, including some examples and templates, to get you started with creating and delivering a stellar research presentation tailored specifically for the business context.

Various research suggests that the average attention span of adults during presentations is around 20 minutes, with a notable drop in an engagement at the 10-minute mark . Beyond that, you might see your audience doing other things.

How can you avoid such a mistake? The answer lies in the adage “keep it simple, stupid” or KISS. We don’t mean dumbing down your content but rather presenting it in a way that is easily digestible and accessible to your audience. One way you can do this is by organizing your research presentation using a clear structure.

Here are the slides you should prioritize when creating your research presentation PowerPoint.

1. Title Page

The title page is the first thing your audience will see during your presentation, so put extra effort into it to make an impression. Of course, writing presentation titles and title pages will vary depending on the type of presentation you are to deliver. In the case of a research presentation, you want a formal and academic-sounding one. It should include:

- The full title of the report

- The date of the report

- The name of the researchers or department in charge of the report

- The name of the organization for which the presentation is intended

When writing the title of your research presentation, it should reflect the topic and objective of the report. Focus only on the subject and avoid adding redundant phrases like “A research on” or “A study on.” However, you may use phrases like “Market Analysis” or “Feasibility Study” because they help identify the purpose of the presentation. Doing so also serves a long-term purpose for the filing and later retrieving of the document.

Here’s a sample title page for a hypothetical market research presentation from Gillette .

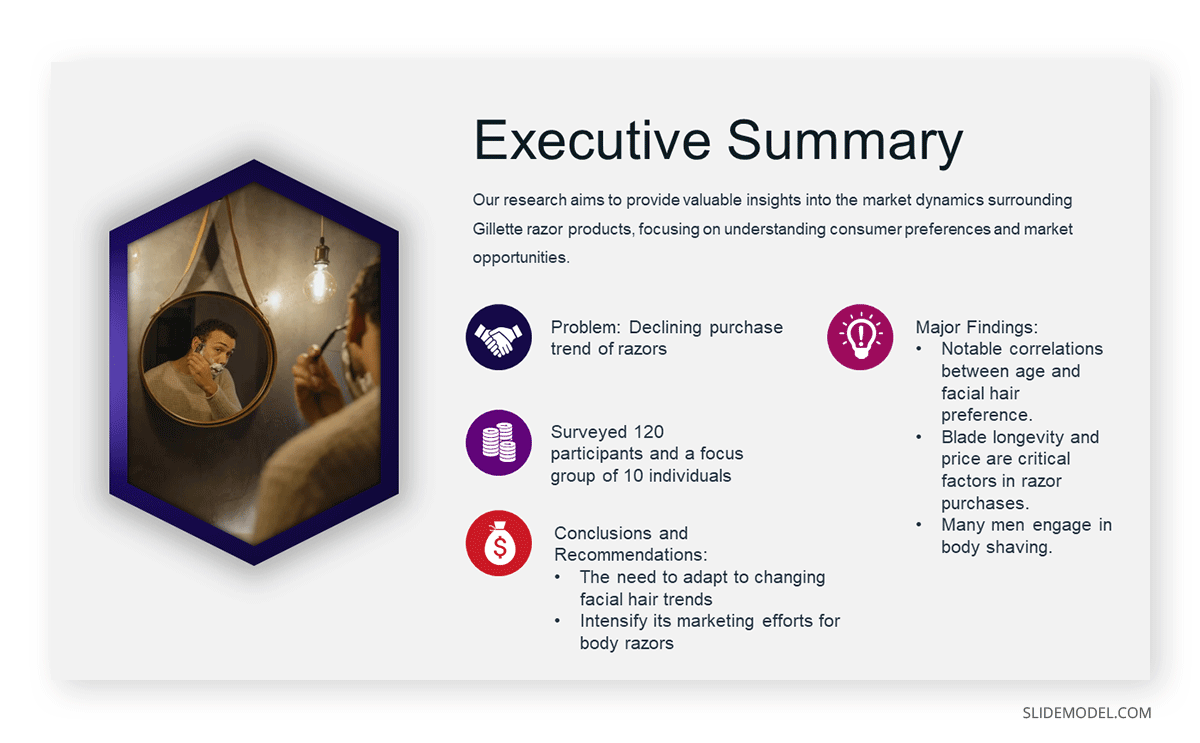

2. Executive Summary Slide

The executive summary marks the beginning of the body of the presentation, briefly summarizing the key discussion points of the research. Specifically, the summary may state the following:

- The purpose of the investigation and its significance within the organization’s goals

- The methods used for the investigation

- The major findings of the investigation

- The conclusions and recommendations after the investigation

Although the executive summary encompasses the entry of the research presentation, it should not dive into all the details of the work on which the findings, conclusions, and recommendations were based. Creating the executive summary requires a focus on clarity and brevity, especially when translating it to a PowerPoint document where space is limited.

Each point should be presented in a clear and visually engaging manner to capture the audience’s attention and set the stage for the rest of the presentation. Use visuals, bullet points, and minimal text to convey information efficiently.

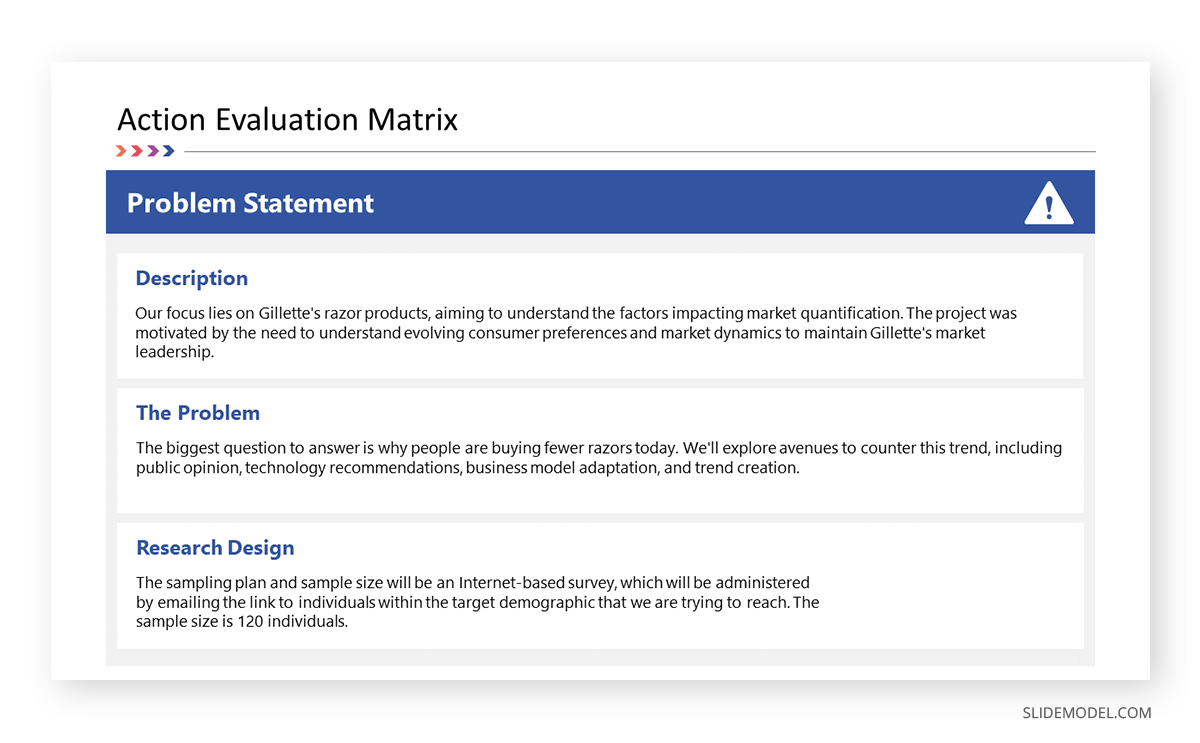

3. Introduction/ Project Description Slides

In this section, your goal is to provide your audience with the information that will help them understand the details of the presentation. Provide a detailed description of the project, including its goals, objectives, scope, and methods for gathering and analyzing data.

You want to answer these fundamental questions:

- What specific questions are you trying to answer, problems you aim to solve, or opportunities you seek to explore?

- Why is this project important, and what prompted it?

- What are the boundaries of your research or initiative?

- How were the data gathered?

Important: The introduction should exclude specific findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

4. Data Presentation and Analyses Slides

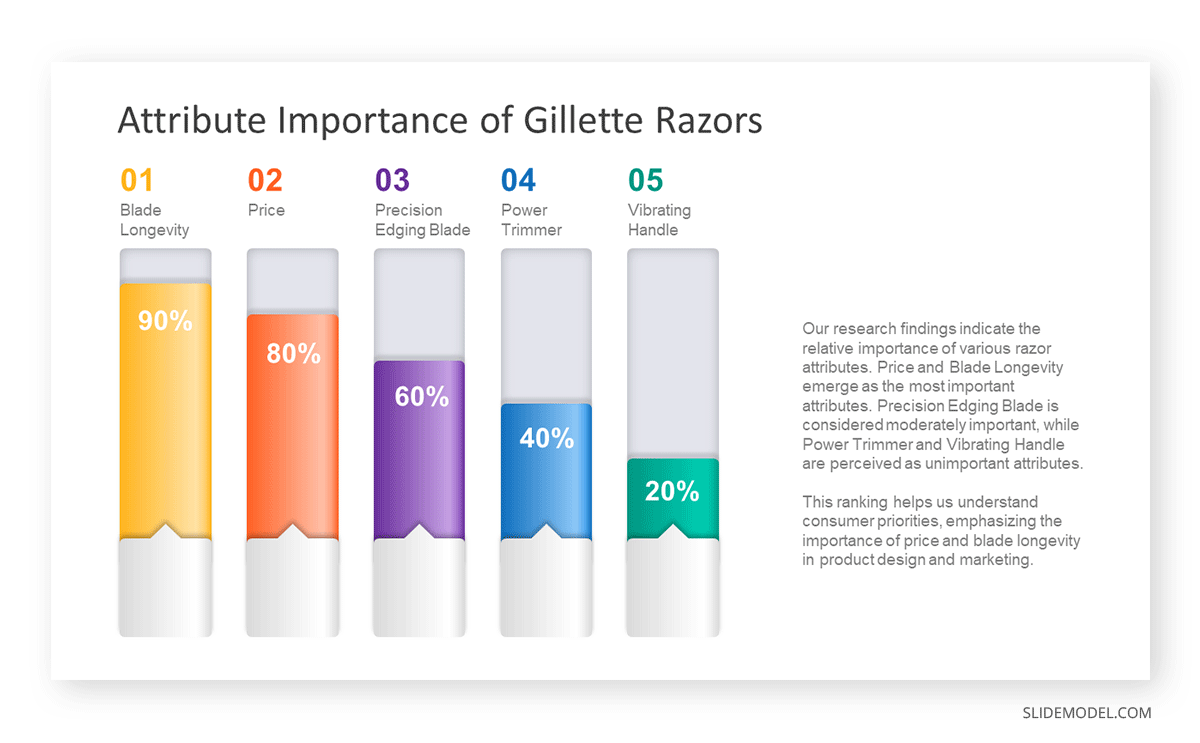

This is the longest section of a research presentation, as you’ll present the data you’ve gathered and provide a thorough analysis of that data to draw meaningful conclusions. The format and components of this section can vary widely, tailored to the specific nature of your research.

For example, if you are doing market research, you may include the market potential estimate, competitor analysis, and pricing analysis. These elements will help your organization determine the actual viability of a market opportunity.

Visual aids like charts, graphs, tables, and diagrams are potent tools to convey your key findings effectively. These materials may be numbered and sequenced (Figure 1, Figure 2, and so forth), accompanied by text to make sense of the insights.

5. Conclusions

The conclusion of a research presentation is where you pull together the ideas derived from your data presentation and analyses in light of the purpose of the research. For example, if the objective is to assess the market of a new product, the conclusion should determine the requirements of the market in question and tell whether there is a product-market fit.

Designing your conclusion slide should be straightforward and focused on conveying the key takeaways from your research. Keep the text concise and to the point. Present it in bullet points or numbered lists to make the content easily scannable.

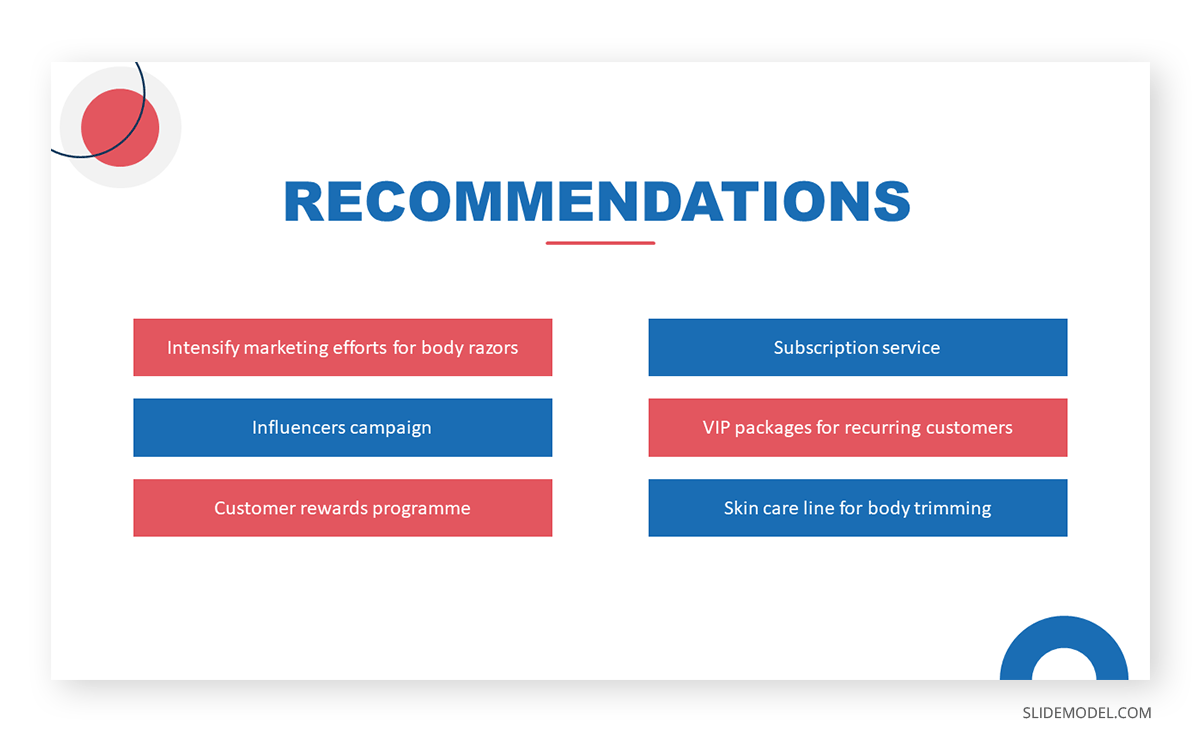

6. Recommendations

The findings of your research might reveal elements that may not align with your initial vision or expectations. These deviations are addressed in the recommendations section of your presentation, which outlines the best course of action based on the result of the research.

What emerging markets should we target next? Do we need to rethink our pricing strategies? Which professionals should we hire for this special project? — these are some of the questions that may arise when coming up with this part of the research.

Recommendations may be combined with the conclusion, but presenting them separately to reinforce their urgency. In the end, the decision-makers in the organization or your clients will make the final call on whether to accept or decline the recommendations.

7. Questions Slide

Members of your audience are not involved in carrying out your research activity, which means there’s a lot they don’t know about its details. By offering an opportunity for questions, you can invite them to bridge that gap, seek clarification, and engage in a dialogue that enhances their understanding.

If your research is more business-oriented, facilitating a question and answer after your presentation becomes imperative as it’s your final appeal to encourage buy-in for your recommendations.

A simple “Ask us anything” slide can indicate that you are ready to accept questions.

1. Focus on the Most Important Findings

The truth about presenting research findings is that your audience doesn’t need to know everything. Instead, they should receive a distilled, clear, and meaningful overview that focuses on the most critical aspects.

You will likely have to squeeze in the oral presentation of your research into a 10 to 20-minute presentation, so you have to make the most out of the time given to you. In the presentation, don’t soak in the less important elements like historical backgrounds. Decision-makers might even ask you to skip these portions and focus on sharing the findings.

2. Do Not Read Word-per-word

Reading word-for-word from your presentation slides intensifies the danger of losing your audience’s interest. Its effect can be detrimental, especially if the purpose of your research presentation is to gain approval from the audience. So, how can you avoid this mistake?

- Make a conscious design decision to keep the text on your slides minimal. Your slides should serve as visual cues to guide your presentation.

- Structure your presentation as a narrative or story. Stories are more engaging and memorable than dry, factual information.

- Prepare speaker notes with the key points of your research. Glance at it when needed.

- Engage with the audience by maintaining eye contact and asking rhetorical questions.

3. Don’t Go Without Handouts

Handouts are paper copies of your presentation slides that you distribute to your audience. They typically contain the summary of your key points, but they may also provide supplementary information supporting data presented through tables and graphs.

The purpose of distributing presentation handouts is to easily retain the key points you presented as they become good references in the future. Distributing handouts in advance allows your audience to review the material and come prepared with questions or points for discussion during the presentation.

4. Actively Listen

An equally important skill that a presenter must possess aside from speaking is the ability to listen. We are not just talking about listening to what the audience is saying but also considering their reactions and nonverbal cues. If you sense disinterest or confusion, you can adapt your approach on the fly to re-engage them.

For example, if some members of your audience are exchanging glances, they may be skeptical of the research findings you are presenting. This is the best time to reassure them of the validity of your data and provide a concise overview of how it came to be. You may also encourage them to seek clarification.

5. Be Confident

Anxiety can strike before a presentation – it’s a common reaction whenever someone has to speak in front of others. If you can’t eliminate your stress, try to manage it.

People hate public speaking not because they simply hate it. Most of the time, it arises from one’s belief in themselves. You don’t have to take our word for it. Take Maslow’s theory that says a threat to one’s self-esteem is a source of distress among an individual.

Now, how can you master this feeling? You’ve spent a lot of time on your research, so there is no question about your topic knowledge. Perhaps you just need to rehearse your research presentation. If you know what you will say and how to say it, you will gain confidence in presenting your work.

All sources you use in creating your research presentation should be given proper credit. The APA Style is the most widely used citation style in formal research.

In-text citation

Add references within the text of your presentation slide by giving the author’s last name, year of publication, and page number (if applicable) in parentheses after direct quotations or paraphrased materials. As in:

The alarming rate at which global temperatures rise directly impacts biodiversity (Smith, 2020, p. 27).

If the author’s name and year of publication are mentioned in the text, add only the page number in parentheses after the quotations or paraphrased materials. As in:

According to Smith (2020), the alarming rate at which global temperatures rise directly impacts biodiversity (p. 27).

Image citation

All images from the web, including photos, graphs, and tables, used in your slides should be credited using the format below.