Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

This topic will provide an overview of major issues related to breech presentation, including choosing the best route for delivery. Techniques for breech delivery, with a focus on the technique for vaginal breech delivery, are discussed separately. (See "Delivery of the singleton fetus in breech presentation" .)

TYPES OF BREECH PRESENTATION

● Frank breech – Both hips are flexed and both knees are extended so that the feet are adjacent to the head ( figure 1 ); accounts for 50 to 70 percent of breech fetuses at term.

● Complete breech – Both hips and both knees are flexed ( figure 2 ); accounts for 5 to 10 percent of breech fetuses at term.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Original Article

- Published: 25 February 2016

Sonographic screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in preterm breech infants: do current guidelines address the specific needs of premature infants?

- R M Spinazzola 1 ,

- M Perrin 1 &

- R L Milanaik 1

Journal of Perinatology volume 36 , pages 552–556 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

2800 Accesses

9 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Disease prevention

- Laboratory techniques and procedures

- Outcomes research

To assess the association between gestational age versus corrected age at the time of hip ultrasound with findings for developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) in preterm breech infants.

Study Design:

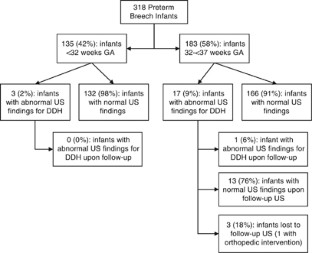

A retrospective medical chart review was conducted to examine hip ultrasounds of 318 premature breech infants for findings associated with DDH.

Positive findings for DDH occurred in 3/135 (2%) of infants <32 weeks gestational age and 17/183 (9%) of infants 32 to <37 weeks gestational age (odds ratio: 0.22, 95% CI: 0.04 to 0.79, P <0.015). No infants born <32 weeks gestational age had abnormal findings for DDH upon follow-up ultrasound. Infants <40 weeks corrected age at the time of hip ultrasound were more likely to have DDH findings compared with infants ⩾ 44 weeks corrected age (odds ratio: 7.83, 95% CI: 2.20 to 29.65, P <0.001).

Conclusion:

Current hip ultrasonography policies that include screening of premature breech infants may need to be revised.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

251,40 € per year

only 20,95 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Risk factors of developmental dysplasia of the hip in a single clinical center

Prenatal diagnosis of fetal growth restriction with polyhydramnios, etiology and impact on postnatal outcome

Comparing head ultrasounds and susceptibility-weighted imaging for the detection of low-grade hemorrhages in preterm infants

Storer SK, Skaggs DL . Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Am Fam Physician 2006; 74 : 1310–1316.

PubMed Google Scholar

Chan A, McCaul KA, Cundy PJ, Haan EA, Byron-Scott R . Perinatal risk factors for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Arch Dis Child 1997; 76 : F94–F100.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Goldberg MJ . Early detection of developmental hip dysplasia: synopsis of the AAP Clinical Practice Guideline. Pediatr Rev 2001; 22 : 131–134.

Atweh LA, Kan JH . Multimodality imaging of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Pediatr Radiol 2013; 43 : 166–171.

Article Google Scholar

Rosendahl K, Markestad T, Lie RT . Developmental dysplasia of the hip. A population-based comparison of ultrasound and clinical findings. Acta Paediatr 1996; 85 : 64–69.

Chan A, Foster BK, Cundy PJ . Problems in the diagnosis of neonatal hip instability. Acta Paediatr 2001; 90 : 836–839.

American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. AIUM practice guideline for the performance of an ultrasound examination for detection and assessment of developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Ultrasound Med 2013; 32 : 1307–1317.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: early detection of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. Pediatrics 2000; 105 : 896–905.

Hickok DE, Gordon DC, Milberg JA, Williams MA, Daling JR . The frequency of breech presentation by gestational age at birth: a large population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992; 166 : 851–852.

Weggemann T, Brown JK, Fulford GE, Minns RA . A study of normal baby movements. Child Care Health Dev 1987; 13 : 41–58.

Kosar P, Ergun E, Gokharman FD, Turgut AT, Kosar U . Follow-up sonographic results for graf type 2a hips. J Ultrasound Med 2011; 30 : 677–683.

Roovers EA, Boere-Boonekamp MM, Castelein RM, Zielhuis GA, Kerkhoff TH . Effectiveness of ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2005; 90 : F25–F30.

Quan T, Kent AL, Carlisle H . Breech preterm infants are at risk of developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Paediatr Child Health 2013; 49 : 658–663.

Rosendahl K, Dezateux C, Fosse KR, Aase H, Aukland SM, Reigstad H et al . Immediate treatment versus sonographic surveillance for mild hip dysplasia in newborns. Pediatrics 2010; 125 : e9–e16.

Karmazyn BK, Gunderman RB, Coley BD, Blatt ER, Bulas D, Fordham L et al . American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria on developmental dysplasia of the hip—child. J Am Coll Radiol 2009; 6 : 551–557.

Sewell MD, Eastwood DM . Screening and treatment in developmental dysplasia of the hip—where do we go from here? Int Orthop 2011; 35 : 1359–1367.

Shipman SA, Helfand M, Moyer VA, Yawn BP . Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: a systematic literature review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics 2006; 117 : e557–e576.

Bialik V, Bialik GM, Blazer S, Sujov P, Wiener F, Berant M . Developmental dysplasia of the hip: a new approach to incidence. Pediatrics 1999; 103 : 93–99.

Woolacott NF, Puhan MA, Steurer J, Kleijnen J . Ultrasonography in screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns: systemic review. BMJ 2005; 330 : 1413.

Mahan ST, Katz JN, Kim YJ . To screen or not to screen? A decision analysis of the utility of screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91 : 1705–1719.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: recommendation statement. Pediatrics 2006; 117 : 898–902.

Barr LV, Rehm A . Should all twins and multiple births undergo ultrasound examination for developmental dysplasia of the hip? A retrospective study of 990 multiple births. Bone Joint J 2013; 95 : 132–134.

Dezateux C, Rosendahl K . Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Lancet 2007; 369 : 1541–1552.

Omeroglu H . Use of ultrasonography in developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Child Orthop 2014; 8 : 105–113.

Jones DA . Neonatal detection of developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg 1998; 80-B : 943–945.

Chiara A, De Pellegrin M . Developmental dysplasia of the hip: to screen or not to screen with ultrasound. Early Hum Dev 2013; 89 : S102–S103.

Keller MS, Nijs ELF . The role of radiographs and US in developmental dysplasia of the hip: how good are they? Pediatr Radiol 2009; 39 : S211–S215.

Nemeth BA, Narotam V . Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Pediatr Rev 2012; 33 : 533–561.

Elbourne D, Dezateux C, Arthur R, Clarke NMP, Gray A, King A et al . Ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of developmental hip dysplasia (UK Hip Trial): clinical and economic results of a multicenter randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 360 : 2009–2017.

Gray A, Elbourne D, Dezateux C, King A, Quinn A, Gardner F . Economic evaluation of ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of developmental hip dysplasia in the United Kingdom and Ireland. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87 : 2472–2479.

Roposch A, Liu LQ, Protopapa E . Variations in the use of diagnostic criteria for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471 : 1946–1954.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dureya Syed and Tabinda Syed for their assistance with this research. The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Cohen Children's Medical Center of New York, Lake Success, NY, USA

J Lee, R M Spinazzola, M Perrin & R L Milanaik

The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, Manhasset, NY, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to R L Milanaik .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lee, J., Spinazzola, R., Kohn, N. et al. Sonographic screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in preterm breech infants: do current guidelines address the specific needs of premature infants?. J Perinatol 36 , 552–556 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.7

Download citation

Received : 17 July 2015

Revised : 08 January 2016

Accepted : 12 January 2016

Published : 25 February 2016

Issue Date : July 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Preterm birth does not increase the risk of developmental dysplasia of the hip: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

- Amirhossein Ghaseminejad-Raeini

- Parmida Shahbazi

- Soroush Baghdadi

BMC Pediatrics (2023)

Traditional Mongolian swaddling and developmental dysplasia of the hip: a randomized controlled trial

- Munkhtulga Ulziibat

- Bayalag Munkhuu

- Stefan Essig

BMC Pediatrics (2021)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

SHARON SCOTT MOREY

Am Fam Physician. 2001;63(3):565-568

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has developed a clinical practice guideline on the early detection of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), which includes frank dislocation, partial dislocation, instability and inadequate formation of the acetabulum. Written by the AAP Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip, the guideline points out that the term “developmental” is preferred over the term “congenital.” Developmental more accurately reflects the disorder because these abnormalities may not be present at birth. According to the guideline, newborn screening surveys suggest that dislocation of the hip may occur at a rate of 1.0 to 1.5 cases per 1,000 newborns.

The guideline, titled “Clinical Practice Guideline: Early Detection of Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip,” appears in the April 2000 issue of Pediatrics . It includes a discussion of the features of the disorder, including risk factors and methods of detection, and of the way in which the recommendations in the guideline were developed.

Risk Factors

The AAP guideline states that the hip is at risk of dislocation in the 12th gestational week, in the 18th gestational week, in the final four weeks of gestation, when mechanical forces play a role, and in the postnatal period. Oligohydramnios and breech presentation are associated with an increased risk of DDH. Studies suggest that as many as 23 percent of infants with breech presentation are affected. Postnatally, positioning of the infant may play a role.

The incidence of DDH is higher in girls, perhaps because females are more susceptible than males to the maternal hormone relaxin, which may contribute to ligamentous laxity. The left hip is affected three times more often than the right hip, which may be related to the left occiput anterior position of most nonbreech infants.

Clinical Features

The AAP guideline states that there are no pathognomonic signs for a dislocated hip. Asymmetry of the thigh or gluteal folds, limb length discrepancy and restricted motion (especially abduction) can be signs of a dislocated hip. The Ortolani and Barlow tests are useful for assessing hip stability in the newborn. A palpable “clunk” during either maneuver is considered a strongly positive sign for dislocation of the hip. A dislocatable hip is described as having a distinctive clunk, whereas a subluxable hip is characterized by a feeling of looseness, a sliding movement without the true clunks felt on the Ortolani and Barlow maneuvers. By eight to 12 weeks of age, the Ortolani and Barlow tests are no longer useful, regardless of the status of the femoral head. At this age, capsule laxity decreases and muscle tightness increases. According to the AAP guideline, the most reliable sign in the three-month-old infant is limitation of abduction. Other features of DDH at this age include asymmetry of the thigh folds, relative shortness of the femur with the hips and knees flexed (called the Allis or Galeazzi sign) and a discrepancy of leg lengths.

The AAP guideline notes that real-time ultrasonography is the most accurate method for imaging the hip in the first few months after birth. Ultrasonography provides visualization of the cartilage, hip stability and features of the acetabulum. Ultrasonography is identified as the technique of choice for clarifying a physical finding suggestive of DDH, for assessing a high-risk infant and for monitoring DDH. Radiographs are of limited value during the first few months of life but are more reliable in infants four to six months of age, when the ossification center develops in the femoral head. According to the guideline, ultrasonography and radiography are equally effective imaging studies for detecting DDH in infants four to six months of age.

Recommendations

The accompanying algorithm gives an overview of the recommendations for DDH screening in infants. The following summarizes the AAP recommendations:

All newborns should be screened by physical examination. Ultrasonography of all newborns is not recommended.

Referral to an orthopedist is recommended if a positive Ortolani or Barlow test is found on the newborn examination. Ultrasonography is not recommended in infants with positive findings, nor is radiographic examination of the pelvis and hips. Figure Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Algorithm for screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip.

Reprinted with permission from American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Quality Improvement. Clinical practice guideline: early detection of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Pediatrics 2000;105:896–905 .

The use of triple diapers in infants with physical signs suggestive of DDH during the newborn period is not recommended. The guideline notes that triple-diaper use is a common practice despite the lack of data on effectiveness.

If the physical examination at birth reveals “equivocally” positive findings (i.e., a soft click, mild asymmetry, but no Ortolani or Barlow sign), a follow-up hip examination should be performed when the infant is two weeks of age.

If the Ortolani or Barlow test is positive at the two-week examination, the infant should be referred to an orthopedist. Referral is deemed urgent but not an emergency.

If the Ortolani or Barlow test is negative at the two-week examination but other physical findings raise the suspicion of DDH, consideration should be given to referring the infant to an orthopedist or obtaining ultrasonography at age three to four weeks.

If the physical examination is negative at two weeks of age, follow-up is recommended at the scheduled well-baby periodic examinations.

If the results of the newborn examination are negative, consideration may be given to risk factors for DDH. These risk factors include the following: female infants, a family history of DDH and breech presentation.

Female Infants

The newborn risk of DDH is 19 per 1,000 in girls. If the newborn examination is negative or equivocally positive, the hips should be reexamined when the infant is two weeks of age.

Infants with a Positive Family History of DDH

When the family history is positive, the newborn risk is 9.4 per 1,000 for boys and 44.0 per 1,000 for girls. When the newborn examination is negative or equivocally positive in boys with a family history, reevaluation of the hips at two weeks of age is recommended. In girls with a family history of DDH, ultrasonographic examination at six weeks of age or radiographic examination of the pelvis and hips at four months of age is recommended.

Breech Presentation

The newborn risk of breech presentation is 120 per 1,000 for girls and 26 per 1,000 for boys. When the newborn examination is negative or equivocally positive in boys with breech presentation, reevaluation of the hips should be conducted at regular intervals. In girls, because of their absolute risk of 120 per 1,000, ultrasonographic examination at six weeks of age or radiographic evaluation of the pelvis and hips at four months of age is recommended. The guideline also notes that there is a high incidence of hip abnormalities in children born breech. For this reason, ultrasonographic examination remains an option in all children born breech.

The hips must be examined at every well-baby visit (two to four days for newborns discharged in less than 48 hours after delivery and by one month, two months, four months, six months, nine months and 12 months of age).

Coverage of guidelines from other organizations does not imply endorsement by AFP or the AAFP.

This series is coordinated by Michael J. Arnold, MD, Assistant Medical Editor.

A collection of Practice Guidelines published in AFP is available at https://www.aafp.org/afp/practguide .

Continue Reading

More in afp.

Copyright © 2001 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

Developmental dysplasia of the hip in preterm breech infants

Affiliations.

- 1 Neonatal Clinical Care Unit, King Edward Memorial Hospital for Women, Subiaco, Western Australia, Australia.

- 2 Department of Radiology, Perth Children's Hospital, Nedlands, Western Australia, Australia.

- 3 Medical Statistics, Women and Infants Research Foundation, Subiaco, Western Australia, Australia.

- 4 Neonatal Clinical Care Unit, King Edward Memorial Hospital for Women, Subiaco, Western Australia, Australia [email protected].

- PMID: 31900256

- DOI: 10.1136/archdischild-2019-317658

Background: Whether preterm infants born with breech presentation are at similar risk of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) as the term breech infants is not known. The information will be vital for DDH screening guidelines.

Methods: A retrospective audit of infants born in the breech position was performed to compare the incidence of DDH in the following gestational age groups: 23-27, 28-31, 32-36 and ≥37 weeks.

Results: A total of 1144 neonates were included in the study. The incidence of DDH did not differ between the groups (11.6%, 9.4%, 13.6% and 11.5%, in 23-27, 28-31, 32-36 and ≥37 weeks, respectively, p=0.40). Sixty infants required intervention for DDH. Multiple logistic regression after correcting for potential confounders showed that gestational age group did not influence the risk of DDH, and requirement of therapy.

Conclusion: Preterm infants born with breech presentation appear to have a similar incidence of DDH to term breech infants. .

Keywords: DDH; breech; developmental dysplasia of the hip; preterm.

© Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2020. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by BMJ.

- Breech Presentation / epidemiology*

- Gestational Age

- Hip Dislocation, Congenital / epidemiology*

- Infant, Newborn

- Infant, Premature

- Logistic Models

- Retrospective Studies

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

- Management of breech presentation

Evidence review M

NICE Guideline, No. 201

National Guideline Alliance (UK) .

- Copyright and Permissions

Review question

What is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy?

Introduction

Breech presentation of the fetus in late pregnancy may result in prolonged or obstructed labour with resulting risks to both woman and fetus. Interventions to correct breech presentation (to cephalic) before labour and birth are important for the woman’s and the baby’s health. The aim of this review is to determine the most effective way of managing a breech presentation in late pregnancy.

Summary of the protocol

Please see Table 1 for a summary of the Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICO) characteristics of this review.

Summary of the protocol (PICO table).

For further details see the review protocol in appendix A .

Methods and process

This evidence review was developed using the methods and process described in Developing NICE guidelines: the manual 2014 . Methods specific to this review question are described in the review protocol in appendix A .

Declarations of interest were recorded according to NICE’s conflicts of interest policy .

Clinical evidence

Included studies.

Thirty-six randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were identified for this review.

The included studies are summarised in Table 2 .

Three studies reported on external cephalic version (ECV) versus no intervention ( Dafallah 2004 , Hofmeyr 1983 , Rita 2011 ). One study reported on a 4-arm trial comparing acupuncture, sweeping of fetal membranes, acupuncture plus sweeping, and no intervention ( Andersen 2013 ). Two studies reported on postural management versus no intervention ( Chenia 1987 , Smith 1999 ).

Seven studies reported on ECV plus anaesthesia ( Chalifoux 2017 , Dugoff 1999 , Khaw 2015 , Mancuso 2000 , Schorr 1997 , Sullivan 2009 , Weiniger 2010 ). Of these studies, 1 study compared ECV plus anaesthesia to ECV plus other dosages of the same anaesthetic ( Chalifoux 2017 ); 4 studies compared ECV plus anaesthesia to ECV only ( Dugoff 1999 , Mancuso 2000 , Schorr 1997 , Weiniger 2010 ); and 2 studies compared ECV plus anaesthesia to ECV plus a different anaesthetic ( Khaw 2015 , Sullivan 2009 ).

Ten studies reported ECV plus a β2 receptor agonist ( Brocks 1984 , Fernandez 1997 , Hindawi 2005 , Impey 2005 , Mahomed 1991 , Marquette 1996 , Nor Azlin 2005 , Robertson 1987 , Van Dorsten 1981 , Vani 2009 ). Of these studies, 5 studies compared ECV plus a β2 receptor agonist to ECV plus placebo ( Fernandez 1997 , Impey 2005 , Marquette 1996 , Nor Azlin 2005 , Vani 2009 ); 1 study compared ECV plus a β2 receptor agonist to ECV alone ( Robertson 1987 ); and 4 studies compared ECV plus a β2 receptor agonist to no intervention ( Brocks 1984 , Hindawi 2005 , Mahomed 1991 , Van Dorsten 1981 ).

One study reported on ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker versus ECV plus placebo ( Kok 2008 ). Two studies reported on ECV plus β2 receptor agonist versus ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker ( Collaris 2009 , Mohamed Ismail 2008 ). Four studies reported on ECV plus a µ-receptor agonist ( Burgos 2016 , Liu 2016 , Munoz 2014 , Wang 2017 ), of which 3 compared against ECV plus placebo ( Liu 2016 , Munoz 2014 , Wang 2017 ) and 1 compared to ECV plus nitrous oxide ( Burgos 2016 ).

Four studies reported on ECV plus nitroglycerin ( Bujold 2003a , Bujold 2003b , El-Sayed 2004 , Hilton 2009 ), of which 2 compared it to ECV plus β2 receptor agonist ( Bujold 2003b , El-Sayed 2004 ) and compared it to ECV plus placebo ( Bujold 2003a , Hilton 2009 ). One study compared ECV plus amnioinfusion versus ECV alone ( Diguisto 2018 ) and 1 study compared ECV plus talcum powder to ECV plus gel ( Vallikkannu 2014 ).

One study was conducted in Australia ( Smith 1999 ); 4 studies in Canada ( Bujold 2003a , Bujold 2003b , Hilton 2009 , Marquette 1996 ); 2 studies in China ( Liu 2016 , Wang 2017 ); 2 studies in Denmark ( Andersen 2013 , Brocks 1984 ); 1 study in France ( Diguisto 2018 ); 1 study in Hong Kong ( Khaw 2015 ); 1 study in India ( Rita 2011 ); 1 study in Israel ( Weiniger 2010 ); 1 study in Jordan ( Hindawi 2005 ); 5 studies in Malaysia ( Collaris 2009 , Mohamed Ismail 2008 , Nor Azlin 2005 , Vallikkannu 2014 , Vani 2009 ); 1 study in South Africa ( Hofmeyr 1983 ); 2 studies in Spain ( Burgos 2016 , Munoz 2014 ); 1 study in Sudan ( Dafallah 2004 ); 1 study in The Netherlands ( Kok 2008 ); 2 studies in the UK ( Impey 2005 , Chenia 1987 ); 9 studies in US ( Chalifoux 2017 , Dugoff 1999 , El-Sayed 2004 , Fernandez 1997 , Mancuso 2000 , Robertson 1987 , Schorr 1997 , Sullivan 2009 , Van Dorsten 1981 ); and 1 study in Zimbabwe ( Mahomed 1991 ).

The majority of studies were 2-arm trials, but there was one 3-arm trial ( Khaw 2015 ) and two 4-arm trials ( Andersen 2013 , Chalifoux 2017 ). All studies were conducted in a hospital or an outpatient ward connected to a hospital.

See the literature search strategy in appendix B and study selection flow chart in appendix C .

Excluded studies

Studies not included in this review with reasons for their exclusions are provided in appendix K .

Summary of clinical studies included in the evidence review

Summaries of the studies that were included in this review are presented in Table 2 .

Summary of included studies.

See the full evidence tables in appendix D and the forest plots in appendix E .

Quality assessment of clinical outcomes included in the evidence review

See the evidence profiles in appendix F .

Economic evidence

A systematic review of the economic literature was conducted but no economic studies were identified which were applicable to this review question.

A single economic search was undertaken for all topics included in the scope of this guideline. See supplementary material 2 for details.

Economic studies not included in this review are listed, and reasons for their exclusion are provided in appendix K .

Summary of studies included in the economic evidence review

No economic studies were identified which were applicable to this review question.

Economic model

No economic modelling was undertaken for this review because the committee agreed that other topics were higher priorities for economic evaluation.

Evidence statements

Clinical evidence statements, comparison 1. complementary therapy versus control (no intervention), critical outcomes, cephalic presentation in labour.

No evidence was identified to inform this outcome.

Method of birth

Caesarean section.

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and control (no intervention) on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.74 (95% CI 0.38 to 1.43).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=200) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and control (no intervention) on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.29 (95% CI 0.73 to 2.29).

Admission to SCBU/NICU

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and control (no intervention) on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.19 (95% CI 0.02 to 1.62).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=200) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and control (no intervention) on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.40 (0.08 to 2.01).

Fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation

Infant death up to 4 weeks chronological age, important outcomes, apgar score <7 at 5 minutes.

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and control (no intervention) on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.32 (95% CI 0.01 to 7.78).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=200) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and control (no intervention) on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.33 (0.01 to 8.09).

Birth before 39 +0 weeks of gestation

Comparison 2. complementary therapy versus other treatment.

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=207) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and membrane sweeping on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.64 (95% CI 0.34 to 1.22).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and acupuncture plus membrane sweeping on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.57 (95% CI 0.30 to 1.07).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=203) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and membrane sweeping on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.13 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.94).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=207) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and membrane sweeping on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.33 (95% CI 0.03 to 3.12).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and acupuncture plus membrane sweeping on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.48 (95% CI 0.04 to 5.22).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=203) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and membrane sweeping on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.69 (95% CI 0.12 to 4.02).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=207) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and membrane sweeping on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.02 to 0.02).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and acupuncture plus membrane sweeping on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.02 to 0.02).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=203) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and membrane sweeping on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.02 to 0.02).

Comparison 3. ECV versus no ECV

- Moderate quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=680) showed that there is clinically important difference favouring ECV over no ECV on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.83 (95% CI 1.53 to 2.18).

Cephalic vaginal birth

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=740) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV over no ECV on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.67 (95% CI 1.20 to 2.31).

Breech vaginal birth

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=680) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV and no ECV on breech vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.29 (95% CI 0.03 to 2.84).

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=740) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV and no ECV on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.52 (95% CI 0.23 to 1.20).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=60) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV and no ECV on admission to SCBU//NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.50 (95% CI 0.14 to 1.82).

- Very low evidence from 3 RCTs (N=740) showed that there is no statistically significant difference between ECV and no ECV on fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.29 (95% CI 0.05 to 1.73) p=0.18.

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV and no ECV on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.28 (95% CI 0.04 to 1.70).

Comparison 4. ECV + Amnioinfusion versus ECV only

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=109) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus amnioinfusion and ECV alone on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.74 (95% CI 0.74 to 4.12).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=109) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus amnioinfusion and ECV alone on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.95 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.19).

Comparison 5. ECV + Anaesthesia versus ECV only

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=210) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus anaesthesia and ECV alone on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.16 (95% CI 0.56 to 2.41).

- Very low quality evidence from 5 RCTs (N=435) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus anaesthesia and ECV alone on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.16 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.74).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=108) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus anaesthesia and ECV alone on breech vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.33 (95% CI 0.04 to 3.10).

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=263) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus anaesthesia and ECV alone on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.76 (95% CI 0.42 to 1.38).

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=69) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus anaesthesia over ECV alone on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: MD −1.80 (95% CI −2.53 to −1.07).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=126) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus anaesthesia and ECV alone on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.03).

Comparison 6. ECV + Anaesthesia versus ECV + Anaesthesia

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.13 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.74).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.81 (95% CI 0.53 to 1.23).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.96 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.50).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=95) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 0.05mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.69 (95% CI 0.37 to 1.28).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.81 (95% CI 0.53 to 1.23).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.96 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.50).

- Very low evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.19 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.79).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.92 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.24).

- Very low evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.08 (95% CI 0.78 to 1.50).

- Very low evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.94 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.28).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.17 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.61).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.03 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.37).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.88 (95% CI 0.64 to 1.20).

Comparison 7. ECV + β2 agonist versus Control (no intervention)

- Moderate quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=256) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus β2 agonist over control (no intervention) on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 4.83 (95% CI 3.27 to 7.11).

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=265) showed that there no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and control (no intervention) on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 2.03 (95% CI 0.22 to 19.01).

- Very low quality evidence from 4 RCTs (N=513) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus β2 agonist over control (no intervention) on breech vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.38 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.69).

- Low quality evidence from 4 RCTs (N=513) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus β2 agonist over control (no intervention) on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.53 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.67).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=48) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and control (no intervention) on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.08 to 0.08).

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=208) showed that there is no statistically significant difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and control (no intervention) on fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD −0.01 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.01) p=0.66.

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=208) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and control (no intervention) on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.80 (95% CI 0.31 to 2.10).

Comparison 8. ECV + β2 agonist versus ECV only

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=172) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV only on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.32 (95% CI 0.67 to 2.62).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=58) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV only on breech vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.75 (95% CI 0.22 to 2.50).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=172) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV only on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.79 (95% CI 0.27 to 2.28).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=114) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV only on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.21 to 4.75).

Comparison 9. ECV + β2 agonist versus ECV + Placebo

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=146) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.54 (95% CI 0.24 to 9.76).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=125) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.27 (95% CI 0.41 to 3.89).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=227) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on breech vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.33 to 2.97).

- Low quality evidence from 4 RCTs (N=532) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.81 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.92)

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=146) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.78 (95% CI 0.17 to 3.63).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=124) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.03).

Comparison 10. ECV + Ca 2+ channel blocker versus ECV + Placebo

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.13 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.48).

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.90 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.12).

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.11 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.40).

- High quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: MD −0.20 (95% CI −0.70 to 0.30).

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no statistically significant difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.01 to 0.01) p=1.00.

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.52 (95% 0.05 to 5.02).

Comparison 11. ECV + Ca2+ channel blocker versus ECV + β2 agonist

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=90) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus β2 agonist over ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.62 (95% CI 0.39 to 0.98).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=126) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus β2 agonist on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.26 (95% CI 0.55 to 2.89).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=132) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus β2 agonist over ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.42 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.91).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=176) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus β2 agonist on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.53 (95% CI 0.05 to 5.22).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=176) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus β2 agonist on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.03).

Comparison 12. ECV + µ-receptor agonist versus ECV only

- High quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=80) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV alone on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.80 to 1.24).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=80) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV alone on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.42 to 2.40).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=126) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV alone on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.03).

Comparison 13. ECV + µ-receptor agonist versus ECV + Placebo

Cephalic vaginal birth after successful ecv.

- High quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=98) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus placebo on cephalic vaginal birth after successful ECV in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.17).

Caesarean section after successful ECV

- Low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=98) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus placebo on caesarean section after successful ECV in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.97 (95% CI 0.33 to 2.84).

Breech vaginal birth after unsuccessful ECV

- High quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=186) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus µ-receptor agonist over ECV plus placebo on breech vaginal birth after unsuccessful ECV in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.10 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.53).

Caesarean section after unsuccessful ECV

- Moderate quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=186) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus placebo on caesarean section after unsuccessful ECV in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.19 (95% CI 1.09 to 1.31).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=137) showed that there is no statistically significant difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus placebo on fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.03) p=1.00.

Comparison 14. ECV + µ-receptor agonist versus ECV + Anaesthesia

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=92) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus anaesthesia on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.04 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.29).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=212) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus anaesthesia on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.90 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.34).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=129) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus anaesthesia on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 2.30 (95% CI 0.21 to 24.74).

- Low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=255) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus anaesthesia on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.02 to 0.02).

Comparison 15. ECV + Nitric oxide donor versus ECV + Placebo

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=224) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus nitric oxide donor and ECV plus placebo on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.13 (95% CI 0.59 to 2.16).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=99) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus nitric oxide donor and ECV plus placebo on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.78 (95% CI 0.49 to 1.22).

- Low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=125) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus nitric oxide donor and ECV plus placebo on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.83 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.01).

Comparison 16. ECV + Nitric oxide donor versus ECV + β2 agonist

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=74) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus nitric oxide donor on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.56 (95% CI 0.29 to 1.09).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=97) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus nitric oxide donor and ECV plus β2 agonist on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.98 (95% CI 0.47 to 2.05).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=59) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus nitric oxide donor and ECV plus β2 agonist on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.07 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.57).

Comparison 17. ECV + Talcum powder versus ECV + Gel

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=95) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus talcum powder and ECV plus gel on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.02 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.53).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=95) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus talcum powder and ECV plus gel on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.08 (95% CI 0.67 to 1.74).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=95) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus talcum powder and ECV plus gel on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.94 (95% CI 0.67 to 1.33).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=95) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus talcum powder and ECV plus gel on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.96 (95% CI 0.38 to 10.19).

Comparison 18. Postural management versus No postural management

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=76) showed that there is no clinically important difference between postural management and no postural management on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.26 (95% CI 0.70 to 2.30).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=76) showed that there is no clinically important difference between postural management and no postural management on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.11 (95% CI 0.59 to 2.07).

Breech vaginal delivery

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=76) showed that there is no clinically important difference between postural management and no postural management on breech vaginal delivery in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.15 (95% CI 0.67 to 1.99).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=76) showed that there is no clinically important difference between postural management and no postural management on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.69 (95% CI 0.31 to 1.52).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=76) showed that there is no clinically important difference between postural management and no postural management on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.24 (95% CI 0.03 to 2.03).

Comparison 19. Postural management + ECV versus ECV only

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=100) showed that there is no clinically important difference between postural management plus ECV and ECV only on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.05 (95% CI 0.80 to 1.38).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=100) showed that there is no clinically important difference between postural management plus ECV and ECV only on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.13 (95% CI 0.00 to 6.55).

Economic evidence statements

No economic evidence was identified which was applicable to this review question.

The committee’s discussion of the evidence

Interpreting the evidence, the outcomes that matter most.

Provision of antenatal care is important for the health and wellbeing of both mother and baby with the aim of avoiding adverse pregnancy outcomes and enhancing maternal satisfaction and wellbeing. Breech presentation in labour may be associated with adverse outcomes for the fetus, which has contributed to an increased likelihood of caesarean birth. The committee therefore agreed that cephalic presentation in labour and method of birth were critical outcomes for the woman, and admission to SCBU/NICU, fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation, and infant death up to 4 weeks chronological age were critical outcomes for the baby. Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes and birth before 39 +0 weeks of gestation were important outcomes for the baby.

The quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence for interventions for managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (that is breech presentation) in late pregnancy ranged from very low to high, with most of the evidence being of a very low or low quality.

This was predominately due to serious overall risk of bias in some outcomes; imprecision around the effect estimate in some outcomes; indirect population in some outcomes; and the presence of serious heterogeneity in some outcomes, which was unresolved by subgroup analysis. The majority of included studies had a small sample size, which contributed to imprecision around the effect estimate.

No evidence was identified to inform the outcomes of infant death up to 4 weeks chronological age and birth before 39 +0 weeks of gestation.

There was no publication bias identified in the evidence. However, the committee noted the influence pharmacological developers may have in these trials as funders, and took this into account in their decision making.

Benefits and harms

The committee discussed that in the case of breech presentation, a discussion with the woman about the different options and their potential benefits, harms and implications is needed to ensure an informed decision. The committee discussed that some women may prefer a breech vaginal birth or choose an elective caesarean birth, and that her preferences should be supported, in line with shared decision making.

The committee discussed that external cephalic version is standard practice for managing breech presentation in uncomplicated singleton pregnancies at or after 36+0 weeks. The committee discussed that there could be variation in the success rates of ECV based on the experience of the healthcare professional providing the ECV. There was some evidence supporting the use of ECV for managing a breech presentation in late pregnancy. The evidence showed ECV had a clinically important benefit in terms of cephalic presentations in labour and cephalic vaginal deliveries, when compared to no intervention. The committee noted that the evidence suggested that ECV was not harmful to the baby, although the effect estimate was imprecise relating to the relative rarity of the fetal death as an outcome.

Cephalic (head-down) vaginal birth is preferred by many women and the evidence suggests that external cephalic version is an effective way to achieve this. The evidence suggested ECV increased the chance for a cephalic vaginal birth and the committee agreed that it was important to explain this to the woman during her consultation.

The committee discussed the optimum timing for ECV. Timing of ECV must take into account the likelihood of the baby turning naturally before a woman commences labour and the possibility of the baby turning back to a breech presentation after ECV if it is done too early. The committee noted that in their experience, current practice was to perform ECV at 37 gestational weeks. The majority of the evidence demonstrating a benefit of ECV in this review involved ECV performed around 37 gestational weeks, although the review did not look for studies directly comparing different timings of ECV and their relative success rates.

The evidence in this review excluded women with previous complicated pregnancies, such as those with previous caesarean section or uterine surgery. The committee discussed that a previous caesarean section indicates a complicated pregnancy and that this population of women are not the focus of this guideline, which concentrates on women with uncomplicated pregnancies.

The committee’s recommendations align with other NICE guidance and cross references to the NICE guideline on caesarean birth and the section on breech presenting in labour in the NICE guideline on intrapartum care for women with existing medical conditions or obstetric complications and their babies were made.

ECV combined with pharmacological agents

There were some small studies comparing a variety of pharmacological agents (including β2 agonists, Ca 2+ channel blockers, µ-receptor agonists and nitric oxide donors) given alongside ECV. Overall the evidence typically showed no clinically important benefit of adding any pharmacological agent to ECV except in comparisons with a control arm with no ECV where it was not possible to isolate the effect of the ECV versus the pharmacological agent. The evidence tended toward benefit most for β2 agonists and µ-receptor agonists however there was no consistent or high quality evidence of benefit even for these agents. The committee agreed that although these pharmacological agents are used in practice, there was insufficient evidence to make a recommendation supporting or refuting their use or on which pharmacological agent should be used.

The committee discussed that the evidence suggesting µ-receptor agonist, remifentanil, had a clinically important benefit in terms reducing breech vaginal births after unsuccessful ECV was biologically implausible. The committee noted that this pharmacological agent has strong sedative effects, depending on the dosage, and therefore studies comparing it to a placebo had possible design flaws as it would be obvious to all parties whether placebo or active drug had been received. The committee discussed that the risks associated with using remifentanil such as respiratory depression, likely outweigh any potential added benefit it may have on managing breech presentation.

There was some evidence comparing different anaesthetics together with ECV. Although there was little consistent evidence of benefit overall, one small study of low quality showed a combination of 2% lidocaine and epinephrine via epidural catheter (anaesthesia) with ECV showed a clinically important benefit in terms of cephalic presentations in labour and the method of birth. The committee discussed the evidence and agreed the use of anaesthesia via epidural catheter during ECV was uncommon practice in the UK and could be expensive, overall they agreed the strength of the evidence available was insufficient to support a change in practice.

Postural management

There was limited evidence on postural management as an intervention for managing breech presentation in late pregnancy, which showed no difference in effectiveness. Postural management was defined as ‘knee-chest position for 15 minutes, 3 times a day’. The committee agreed that in their experience women valued trying interventions at home first which might make postural management an attractive option for some women, however, there was no evidence that postural management was beneficial. The committee also noted that in their experience postural management can cause notable discomfort so it is not an intervention without disadvantages.

Cost effectiveness and resource use

A systematic review of the economic literature was conducted but no relevant studies were identified which were applicable to this review question.

The committee’s recommendations to offer external cephalic version reinforces current practice. The committee noted that, compared to no intervention, external cephalic version results in clinically important benefits and that there would also be overall downstream cost savings from lower adverse events. It was therefore the committee’s view that offering external cephalic version is cost effective and would not entail any resource impact.

Andersen 2013

Brocks 1984

Bujold 2003

Burgos 2016

Chalifoux 2017

Chenia 1987

Collaris 2009

Dafallah 2004

Diguisto 2018

Dugoff 1999

El-Sayed 2004

Fernandez 1997

Hindawi 2005

Hilton 2009

Hofmeyr 1983

Mahomed 1991

Mancuso 2000

Marquette 1996

Mohamed Ismail 2008

NorAzlin 2005

Robertson 1987

Schorr 1997

Sullivan 2009

VanDorsten 1981

Vallikkannu 2014

Weiniger 2010

Appendix A. Review protocols

Review protocol for review question: What is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy? (PDF, 260K)

Appendix B. Literature search strategies

Literature search strategies for review question: What is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy? (PDF, 281K)

Appendix C. Clinical evidence study selection

Clinical study selection for: What is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy? (PDF, 113K)

Appendix D. Clinical evidence tables

Clinical evidence tables for review question: What is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy? (PDF, 1.2M)

Appendix E. Forest plots

Forest plots for review question: What is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy? (PDF, 678K)

Appendix F. GRADE tables

GRADE tables for review question: What is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy? (PDF, 1.0M)

Appendix G. Economic evidence study selection

Economic evidence study selection for review question: what is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy, appendix h. economic evidence tables, economic evidence tables for review question: what is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy, appendix i. economic evidence profiles, economic evidence profiles for review question: what is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy, appendix j. economic analysis, economic evidence analysis for review question: what is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy.

No economic analysis was conducted for this review question.

Appendix K. Excluded studies

Excluded clinical and economic studies for review question: what is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy, clinical studies, table 24 excluded studies.

View in own window

Economic studies

No economic evidence was identified for this review.

Appendix L. Research recommendations

Research recommendations for review question: what is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy.

No research recommendations were made for this review question.

Evidence reviews underpinning recommendation 1.2.38

These evidence reviews were developed by the National Guideline Alliance, which is a part of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Disclaimer : The recommendations in this guideline represent the view of NICE, arrived at after careful consideration of the evidence available. When exercising their judgement, professionals are expected to take this guideline fully into account, alongside the individual needs, preferences and values of their patients or service users. The recommendations in this guideline are not mandatory and the guideline does not override the responsibility of healthcare professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient and/or their carer or guardian.

Local commissioners and/or providers have a responsibility to enable the guideline to be applied when individual health professionals and their patients or service users wish to use it. They should do so in the context of local and national priorities for funding and developing services, and in light of their duties to have due regard to the need to eliminate unlawful discrimination, to advance equality of opportunity and to reduce health inequalities. Nothing in this guideline should be interpreted in a way that would be inconsistent with compliance with those duties.

NICE guidelines cover health and care in England. Decisions on how they apply in other UK countries are made by ministers in the Welsh Government , Scottish Government , and Northern Ireland Executive . All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn.

- Cite this Page National Guideline Alliance (UK). Management of breech presentation: Antenatal care: Evidence review M. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2021 Aug. (NICE Guideline, No. 201.)

- PDF version of this title (2.2M)

In this Page

Other titles in this collection.

- NICE Evidence Reviews Collection

Related NICE guidance and evidence

- NICE Guideline 201: Antenatal care

Supplemental NICE documents

- Supplement 1: Methods (PDF)

- Supplement 2: Health economics (PDF)

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Review Identification of breech presentation: Antenatal care: Evidence review L [ 2021] Review Identification of breech presentation: Antenatal care: Evidence review L National Guideline Alliance (UK). 2021 Aug

- Vaginal delivery of breech presentation. [J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009] Vaginal delivery of breech presentation. Kotaska A, Menticoglou S, Gagnon R, MATERNAL FETAL MEDICINE COMMITTEE. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009 Jun; 31(6):557-566.

- Review Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. [Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005] Review Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. Coyle ME, Smith CA, Peat B. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Apr 18; (2):CD003928. Epub 2005 Apr 18.

- [Fetal expulsion: Which interventions for perineal prevention? CNGOF Perineal Prevention and Protection in Obstetrics Guidelines]. [Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol. 2...] [Fetal expulsion: Which interventions for perineal prevention? CNGOF Perineal Prevention and Protection in Obstetrics Guidelines]. Riethmuller D, Ramanah R, Mottet N. Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol. 2018 Dec; 46(12):937-947. Epub 2018 Oct 28.

- Foetal weight, presentaion and the progress of labour. II. Breech and occipito-posterior presentation related to the baby's weight and the length of the first stage of labour. [J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1961] Foetal weight, presentaion and the progress of labour. II. Breech and occipito-posterior presentation related to the baby's weight and the length of the first stage of labour. BAINBRIDGE MN, NIXON WC, SMYTH CN. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1961 Oct; 68:748-54.

Recent Activity

- Management of breech presentation Management of breech presentation

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 105, Issue 5

- Developmental dysplasia of the hip in preterm breech infants

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Deeparaj Hegde 1 ,

- Neil Powers 2 ,

- Elizabeth A Nathan 3 ,

- Abhijeet Anant Rakshasbhuvankar 1

- 1 Neonatal Clinical Care Unit , King Edward Memorial Hospital for Women , Subiaco , Western Australia , Australia

- 2 Department of Radiology , Perth Children's Hospital , Nedlands , Western Australia , Australia

- 3 Medical Statistics , Women and Infants Research Foundation , Subiaco , Western Australia , Australia

- Correspondence to Dr Abhijeet Anant Rakshasbhuvankar, King Edward Memorial Hospital for Women, Perth, Subiaco, WA 6008, Australia; abhijeet.rakshasbhuvankar{at}health.wa.gov.au

Background Whether preterm infants born with breech presentation are at similar risk of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) as the term breech infants is not known. The information will be vital for DDH screening guidelines.

Methods A retrospective audit of infants born in the breech position was performed to compare the incidence of DDH in the following gestational age groups: 23–27, 28–31, 32–36 and ≥37 weeks.

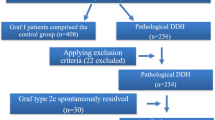

Results A total of 1144 neonates were included in the study. The incidence of DDH did not differ between the groups (11.6%, 9.4%, 13.6% and 11.5%, in 23–27, 28–31, 32–36 and ≥37 weeks, respectively, p=0.40). Sixty infants required intervention for DDH. Multiple logistic regression after correcting for potential confounders showed that gestational age group did not influence the risk of DDH, and requirement of therapy.

Conclusion Preterm infants born with breech presentation appear to have a similar incidence of DDH to term breech infants.

- developmental dysplasia of the hip

https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2019-317658

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Breech presentation is considered to be ‘high risk’ for developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) as it causes prolonged knee extension in utero, resulting in sustained hamstring forces on the hip. 1 As preterm infants are exposed to less intrauterine forces and for a shorter duration, whether breech presentation continues to be a risk factor for DDH in preterm infants is not known. 2 Therefore, we performed a study to compare the incidence of DDH in term and preterm breech infants. Our objective was to compare incidence of DDH detected by ultrasonography (at 6 weeks of corrected age or later) or X-ray (after 4 months of corrected age) of hip joint in extremely (23–27 weeks), very (28–31 weeks) and moderate to late (32–36 weeks) preterm breech infants with that of term (≥37 weeks) breech infants. 3

The American Academy of Paediatrics (AAP) recommends DDH surveillance with periodic physical examinations, with additional hip ultrasound or after 4 months of age radiographs in infants with identified risk factors, irrespective of the gestational age at birth. 4 The data from our study will be vital to inform current DDH screening guidelines if breech presentation in preterm infants is a risk factor as in term infants.

We performed a retrospective observational study of all infants born with breech presentation between 2005 and 2016 at King Edward Memorial Hospital and admitted in the neonatal unit, Western Australia.

Infants born with breech presentation irrespective of their gestational age at birth had DDH surveillance as per our hospital guideline ( https://healthpoint.hdwa.health.wa.gov.au/policies/Policies/NMAHS/WNHS/WNHS.NEO.DevelopmentalDysplasiaoftheHips(DDH).pdf ). The guideline was consistent with AAP guideline and involved (1) clinical examination with Barlow and Ortolani tests in the neonatal period, (2) ultrasonography screening at 6 weeks’ corrected age, (3) follow-up by paediatric orthopaedic registrar/consultant with clinical examination and (4) additional hip ultrasounds and X-ray as deemed necessary by the orthopaedic registrar/consultant. The orthopaedic registrars were trainee doctors pursuing their orthopaedic training for the Fellowship of Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS) and Fellowship of Australian Orthopaedic Association (AOA). The registrars had at least 3 years of postgraduate experience. The consultants were Fellows of RACS and AOA with postgraduate experience of at least 10 years.