Covering a story? Visit our page for journalists or call (773) 702-8360.

New Certificate Program

Top Stories

- Three College students chosen to address UChicago's Class of 2024

- UChicago men’s tennis team storms back to win NCAA championship

- Atop a Chilean mountain, undergraduate students make cutting-edge astronomical observations

The origin of life on Earth, explained

The origin of life on Earth stands as one of the great mysteries of science. Various answers have been proposed, all of which remain unverified. To find out if we are alone in the galaxy, we will need to better understand what geochemical conditions nurtured the first life forms. What water, chemistry and temperature cycles fostered the chemical reactions that allowed life to emerge on our planet? Because life arose in the largely unknown surface conditions of Earth’s early history, answering these and other questions remains a challenge.

Several seminal experiments in this topic have been conducted at the University of Chicago, including the Miller-Urey experiment that suggested how the building blocks of life could form in a primordial soup.

Jump to a section:

- When did life on Earth begin?

Where did life on Earth begin?

What are the ingredients of life on earth, what are the major scientific theories for how life emerged, what is chirality and why is it biologically important, what research are uchicago scientists currently conducting on the origins of life, when did life on earth begin .

Earth is about 4.5 billion years old. Scientists think that by 4.3 billion years ago, Earth may have developed conditions suitable to support life. The oldest known fossils, however, are only 3.7 billion years old. During that 600 million-year window, life may have emerged repeatedly, only to be snuffed out by catastrophic collisions with asteroids and comets.

The details of those early events are not well preserved in Earth’s oldest rocks. Some hints come from the oldest zircons, highly durable minerals that formed in magma. Scientists have found traces of a form of carbon—an important element in living organisms— in one such 4.1 billion-year-old zircon . However, it does not provide enough evidence to prove life’s existence at that early date.

Two possibilities are in volcanically active hydrothermal environments on land and at sea.

Some microorganisms thrive in the scalding, highly acidic hot springs environments like those found today in Iceland, Norway and Yellowstone National Park. The same goes for deep-sea hydrothermal vents. These chimney-like vents form where seawater comes into contact with magma on the ocean floor, resulting in streams of superheated plumes. The microorganisms that live near such plumes have led some scientists to suggest them as the birthplaces of Earth’s first life forms.

Organic molecules may also have formed in certain types of clay minerals that could have offered favorable conditions for protection and preservation. This could have happened on Earth during its early history, or on comets and asteroids that later brought them to Earth in collisions. This would suggest that the same process could have seeded life on planets elsewhere in the universe.

The recipe consists of a steady energy source, organic compounds and water.

Sunlight provides the energy source at the surface, which drives photosynthesis. On the ocean floor, geothermal energy supplies the chemical nutrients that organisms need to live.

Also crucial are the elements important to life . For us, these are carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and phosphorus. But there are several scientific mysteries about how these elements wound up together on Earth. For example, scientists would not expect a planet that formed so close to the sun to naturally incorporate carbon and nitrogen. These elements become solid only under very cold temperatures, such as exist in the outer solar system, not nearer to the sun where Earth is. Also, carbon, like gold, is rare at the Earth’s surface. That’s because carbon chemically bonds more often with iron than rock. Gold also bonds more often with metal, so most of it ends up in the Earth’s core. So, how did the small amounts found at the surface get there? Could a similar process also have unfolded on other planets?

The last ingredient is water. Water now covers about 70% of Earth’s surface, but how much sat on the surface 4 billion years ago? Like carbon and nitrogen, water is much more likely to become a part of solid objects that formed at a greater distance from the sun. To explain its presence on Earth, one theory proposes that a class of meteorites called carbonaceous chondrites formed far enough from the sun to have served as a water-delivery system.

There are several theories for how life came to be on Earth. These include:

Life emerged from a primordial soup

As a University of Chicago graduate student in 1952, Stanley Miller performed a famous experiment with Harold Urey, a Nobel laureate in chemistry. Their results explored the idea that life formed in a primordial soup.

Miller and Urey injected ammonia, methane and water vapor into an enclosed glass container to simulate what were then believed to be the conditions of Earth’s early atmosphere. Then they passed electrical sparks through the container to simulate lightning. Amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, soon formed. Miller and Urey realized that this process could have paved the way for the molecules needed to produce life.

Scientists now believe that Earth’s early atmosphere had a different chemical makeup from Miller and Urey’s recipe. Even so, the experiment gave rise to a new scientific field called prebiotic or abiotic chemistry, the chemistry that preceded the origin of life. This is the opposite of biogenesis, the idea that only a living organism can beget another living organism.

Seeded by comets or meteors

Some scientists think that some of the molecules important to life may be produced outside the Earth. Instead, they suggest that these ingredients came from meteorites or comets.

“A colleague once told me, ‘It’s a lot easier to build a house out of Legos when they’re falling from the sky,’” said Fred Ciesla, a geophysical sciences professor at UChicago. Ciesla and that colleague, Scott Sandford of the NASA Ames Research Center, published research showing that complex organic compounds were readily produced under conditions that likely prevailed in the early solar system when many meteorites formed.

Meteorites then might have served as the cosmic Mayflowers that transported molecular seeds to Earth. In 1969, the Murchison meteorite that fell in Australia contained dozens of different amino acids—the building blocks of life.

Comets may also have offered a ride to Earth-bound hitchhiking molecules, according to experimental results published in 2001 by a team of researchers from Argonne National Laboratory, the University of California Berkeley, and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. By showing that amino acids could survive a fiery comet collision with Earth, the team bolstered the idea that life’s raw materials came from space.

In 2019, a team of researchers in France and Italy reported finding extraterrestrial organic material preserved in the 3.3 billion-year-old sediments of Barberton, South Africa. The team suggested micrometeorites as the material’s likely source. Further such evidence came in 2022 from samples of asteroid Ryugu returned to Earth by Japan’s Hayabusa2 mission. The count of amino acids found in the Ryugu samples now exceeds 20 different types .

In 1953, UChicago researchers published a landmark paper in the Journal of Biological Chemistry that marked the discovery of the pro-chirality concept , which pervades modern chemistry and biology. The paper described an experiment showing that the chirality of molecules—or “handedness,” much the way the right and left hands differ from one another—drives all life processes. Without chirality, large biological molecules such as proteins would be unable to form structures that could be reproduced.

Today, research on the origin of life at UChicago is expanding. As scientists have been able to find more and more exoplanets—that is, planets around stars elsewhere in the galaxy—the question of what the essential ingredients for life are and how to look for signs of them has heated up.

Nobel laureate Jack Szostak joined the UChicago faculty as University Professor in Chemistry in 2022 and will lead the University’s new interdisciplinary Origins of Life Initiative to coordinate research efforts into the origin of life on Earth. Scientists from several departments of the Physical Sciences Division are joining the initiative, including specialists in chemistry, astronomy, geology and geophysics.

“Right now we are getting truly unprecedented amounts of data coming in: Missions like Hayabusa and OSIRIS-REx are bringing us pieces of asteroids, which helps us understand the conditions that form planets, and NASA’s new JWST telescope is taking astounding data on the solar system and the planets around us ,” said Prof. Ciesla. “I think we’re going to make huge progress on this question.”

Last updated Sept. 19, 2022.

Faculty Experts

Clara Blättler

Fred Ciesla

Jack Szostak

Recommended Stories

Earth could have supported crust, life earlier than thought

Earth’s building blocks formed during the solar system’s first…

Additional Resources

The Origins of Life Speaker Series

Recommended Podcasts

Big Brains podcast: Unraveling the mystery of life’s origins on Earth

Discovering the Missing Link with Neil Shubin (Ep. 1)

More Explainers

Improv, Explained

Cosmic rays, explained

Related Topics

Latest news, faces of convocation: meet the people who play vital roles in uchicago’s celebration.

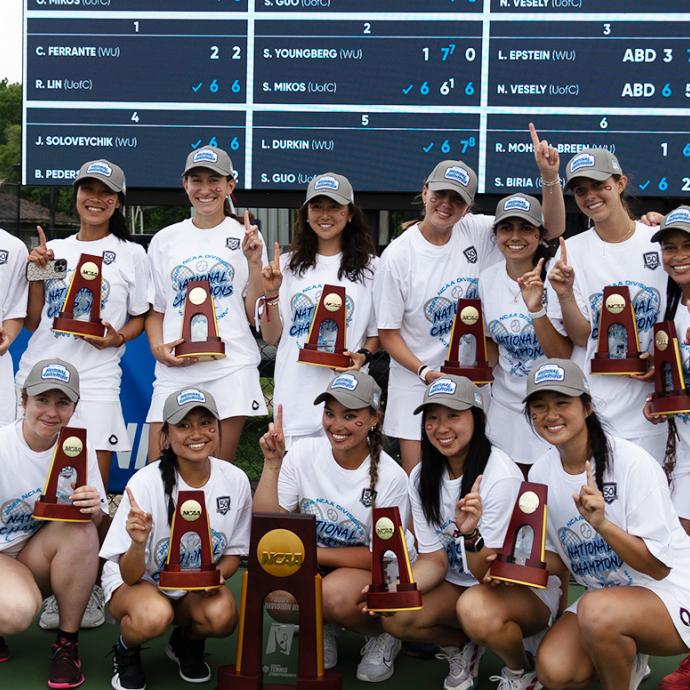

UChicago women’s tennis team wins first NCAA title

Inside the Lab

He Lab: Using the science of RNA to feed the world

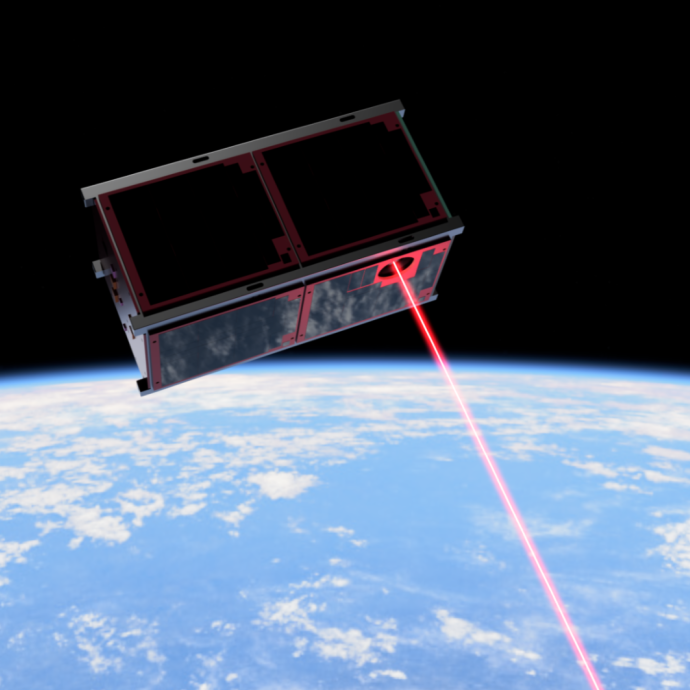

NASA selects UChicago undergraduates’ proposal to build a ‘nano-satellite’

Go 'Inside the Lab' at UChicago

Explore labs through videos and Q and As with UChicago faculty, staff and students

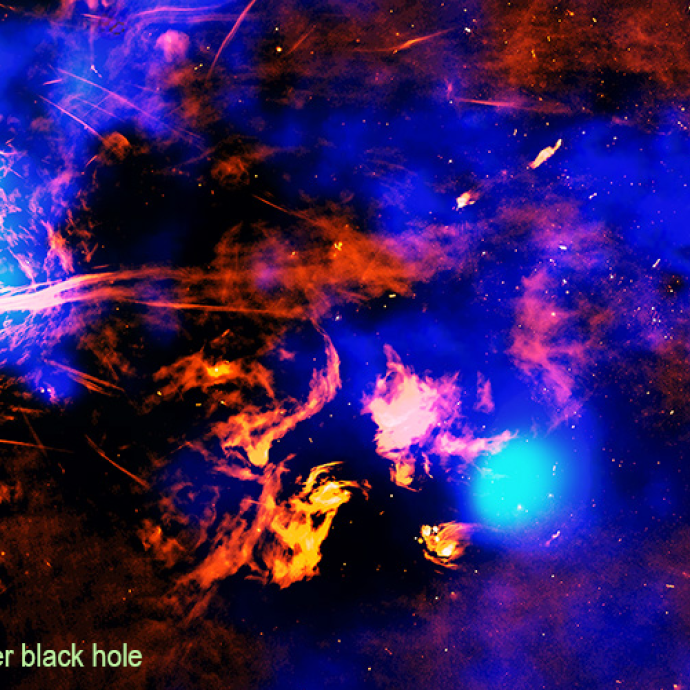

Scientists may have found the spot where our supermassive black hole “vents”

Harris School of Public Policy

How do parents’ decisions impact a child’s development?

Around uchicago, uchicago to offer new postbaccalaureate premedical certificate program.

Carnegie Fellow

UChicago political scientist Molly Offer-Westort named Carnegie Fellow

National Academy of Sciences

Five UChicago faculty elected to National Academy of Sciences in 2024

Laing Award

UChicago Press awards top honor to Margareta Ingrid Christian for ‘Objects in A…

Pulitzer Prize

Trina Reynolds-Tyler, MPP'20, wins Pulitzer Prize in Local Reporting

UChicago announces 2024 winners of Quantrell and PhD Teaching Awards

Biological Sciences Division

“You have to be open minded, planning to reinvent yourself every five to seven years.”

Prof. Stuart Rowan elected to the Royal Society

Advertisement

How we will discover the mysterious origins of life once and for all

Seventy years ago, three discoveries propelled our understanding of how life on Earth began. But has the biggest clue to life's origins been staring biologists in the face all along?

By Michael Marshall

30 October 2023

The constant changing landscape of Earth may be a vital part of the story of the origins of the first ecosystems.

MARK GARLICK/Spl/Alamy;

HOW did life on Earth begin? Until 70 years ago, generations of scientists had failed to throw much light on biology’s murky beginnings. But then came three crucial findings in quick succession.

In April 1953, the race to uncover the structure of DNA reached its climax. Geneticists soon realised that its double helix form could help explain how life replicates itself – a fundamental property thought to have appeared at or around the origin of life. Just three weeks later, news broke of the astonishing Miller-Urey experiment, which showed how a simple cocktail of chemicals could spontaneously generate amino acids, vital for building the molecules of life. Finally, in September 1953, we gained our first accurate estimate for the age of Earth, giving us a clearer idea of exactly how old life might be.

At that point, we seemed poised to finally understand life’s origins. Today, conclusive answers remain elusive. But the past few years have brought real signs of progress.

For instance, we have found that life’s ability to replicate is not wholly reliant on DNA. We also have a far better idea of the conditions on early Earth when life first appeared – and we are beginning to conduct experiments into how it emerged that are much more sophisticated than Miller-Urey.

A radical new theory rewrites the story of how life on Earth began

It has long been thought that the ingredients for life came together slowly, bit by bit. Now there is evidence it all happened at once in a chemical big bang

So, 70 years on from that incredible year of breakthroughs, how has our picture of life’s origins changed? And what remains to be figured out before we can satisfactorily answer biology’s ultimate question?

Definitions of life

“I think in the 50s we knew very little about life,” says …

Article amended on 3 November 2023

Sign up to our weekly newsletter.

Receive a weekly dose of discovery in your inbox! We'll also keep you up to date with New Scientist events and special offers.

To continue reading, subscribe today with our introductory offers

No commitment, cancel anytime*

Offer ends 2nd of July 2024.

*Cancel anytime within 14 days of payment to receive a refund on unserved issues.

Inclusive of applicable taxes (VAT)

Existing subscribers

More from New Scientist

Explore the latest news, articles and features

Quantum biology: New clues on how life might make use of weird physics

Subscriber-only

Environment

To rescue biodiversity, we need a better way to measure it, powerful shot of elephants eating garbage up for earth photo contest, why criticisms of the proposed anthropocene epoch miss the point, popular articles.

Trending New Scientist articles

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.3(3); 2013 Mar

The origin of life: what we know, what we can know and what we will never know

1 Department of Chemistry, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Be'er Sheva, 84105, Israel

Robert Pascal

2 Institut des Biomolécules Max Mousseron (UMR 5247, CNRS, Universités Montpellier 1 and Montpellier 2), Université Montpellier 2, Place E. Bataillon 34095, Montpellier Cedex 05, France

The origin of life (OOL) problem remains one of the more challenging scientific questions of all time. In this essay, we propose that following recent experimental and theoretical advances in systems chemistry, the underlying principle governing the emergence of life on the Earth can in its broadest sense be specified, and may be stated as follows: all stable (persistent) replicating systems will tend to evolve over time towards systems of greater stability. The stability kind referred to, however, is dynamic kinetic stability, and quite distinct from the traditional thermodynamic stability which conventionally dominates physical and chemical thinking. Significantly, that stability kind is generally found to be enhanced by increasing complexification, since added features in the replicating system that improve replication efficiency will be reproduced, thereby offering an explanation for the emergence of life's extraordinary complexity. On the basis of that simple principle, a fundamental reassessment of the underlying chemistry–biology relationship is possible, one with broad ramifications. In the context of the OOL question, this novel perspective can assist in clarifying central ahistoric aspects of abiogenesis, as opposed to the many historic aspects that have probably been forever lost in the mists of time.

2. Introduction

The origin of life (OOL) problem continues to be one of the most intriguing and challenging questions in science (for recent reviews on the OOL, see [ 1 – 6 ]). Its resolution would not only satisfy man's curiosity regarding this central existential issue, but would also shed light on a directly related topic—the precise nature of the physico-chemical relationship linking animate and inanimate matter. As one of us (A.P.) has noted previously [ 1 , 7 , 8 ], until the principles governing the process by which life on the Earth emerged can be uncovered, an understanding of life's essence, the basis for its striking characteristics, and outlining a feasible strategy for the synthesis of what could be classified as a simple life form will probably remain out of reach. In this essay, we will argue that recent developments in systems chemistry [ 9 – 11 ] have dramatically changed our ability to deal with the OOL problem by enabling the chemistry–biology connection to be clarified, at least in broad outline. The realization that abiogenesis—the chemical process by which simplest life emerged from inanimate beginnings—and biological evolution may actually be one single continuous physico-chemical process with an identifiable driving force opens up new avenues towards resolution of the OOL problem [ 1 , 7 , 12 , 13 ]. In fact that unification actually enables the basic elements of abiogenesis to be outlined, in much the same way that Darwin's biological theory outlined the basic mechanism for biological evolution. The goal of this commentary therefore is to discuss what aspects of the OOL problem can now be considered as resolved, what aspects require further study and what aspects may, in all probability, never be known.

3. Is the origin of life problem soluble in principle?

In addressing the OOL question, it first needs to be emphasized that the question has two distinct facets—historic and ahistoric, and the ability to uncover each of these two facets is quite different. Uncovering the historic facet is the more problematic one. Uncovering that facet would require specifying the original chemical system from which the process of abiogenesis began, together with the chemical pathway from that initiating system right through the extensive array of intermediate structures leading to simplest life. Regretfully, however, much of that historic information will probably never be known. Evolutionary processes are contingent, suggesting that any number of feasible pathways could have led from inanimate matter to earliest life, provided, of course, that those pathways were consistent with the underlying laws of physics and chemistry. The difficulty arises because historic events, once they have taken place, can only be revealed if their occurrence was recorded in some manner. Indeed, it is this historic facet of abiogenesis that makes the OOL problem so much more intractable than the parallel question of biological evolution. Biological evolution also has its historic and ahistoric facets. But whereas for biological evolution the historic record is to a degree accessible through palaeobiologic and phylogenetic studies, for the process of abiogenesis those methodologies have proved uninformative; there is no known geological record pertaining to prebiotic systems, and phylogenetic studies become less informative the further back one goes in attempting to trace out ancestral lineages. Phylogenetic studies presume the existence of organismal individuality and the genealogical (vertical) transfer of genetic information. However, the possibility that earliest life may have been communal [ 14 ] and dominated by horizontal gene transfer [ 15 – 17 ] suggests that information regarding the evolutionary stages that preceded the last universal common ancestor [ 18 ] would have to be considered highly speculative. Accordingly, the significance of such studies to the characterization of early life, let alone prebiotic systems, becomes highly uncertain.

The conclusion seems clear: speculation regarding the precise historic path from animate to inanimate—the identity of specific materials that were available at particular physical locations on the prebiotic Earth, together with the chemical structures of possible intermediate stages along the long road to life—may lead to propositions that are, though thought-provoking and of undeniable interest, effectively unfalsifiable, and therefore of limited scientific value.

Given that awkward reality, the focus of OOL research needs to remain on the ahistoric aspects—the principles that would explain the remarkable transformation of inanimate matter to simple life. There is good reason to think that the emergence of life on the Earth did not just involve a long string of random chemical events that fortuitously led to a simple living system. If life had emerged in such an arbitrary way, then the mechanistic question of abiogenesis would be fundamentally without explanation—a stupendously improbable chemical outcome whose likelihood of repetition would be virtually zero. However, the general view, now strongly supported by recent studies in systems chemistry, is that the process of abiogenesis was governed by underlying physico-chemical principles, and the central goal of OOL studies should therefore be to delineate those principles. Significantly, even if the underlying principles governing the transformation of inanimate to animate were to be revealed, that would still not mean that the precise historic path could be specified. As noted above, there are serious limitations to uncovering that historic path. The point however is that if the principles underlying life's emergence on the Earth could be more clearly delineated, then the mystery of abiogenesis would be dramatically transformed. No longer would the problem of abiogenesis be one of essence , but rather one of detail . The major mystery at the heart of the OOL debate would be broadly resolved and the central issue would effectively be replaced by a variety of chemical questions that deal with the particular mechanisms by which those underlying principles could have been expressed. Issues such as identifying historic transitions, the definition of life, would become to some extent arbitrary and ruled by scientific conventions, rather than by matters of principle.

4. The role of autocatalysis during abiogenesis

In the context of the OOL debate, there is one single and central historic fact on which there is broad agreement—that life's emergence was initiated by some autocatalytic chemical system. The two competing narratives within the OOL's long-standing debate—‘replication first’ or ‘metabolism first’—though differing in key elements, both build on that autocatalytic character (see [ 1 ] and references therein). The ‘replication first’ school of thought stresses the role of oligomeric compounds, which express that autocatalytic capability through their ability to self-replicate, an idea that can be traced back almost a century to the work of Troland [ 19 ], while the ‘metabolism first’ school of thought emphasizes the emergence of cyclic networks, as articulated by Kauffman [ 20 ] in the 1980s and reminiscent of the metabolic cycles found in all extant life. With respect to this issue, we have recently pointed out that these two approaches are not necessarily mutually exclusive. It could well be that both oligomeric entities and cyclic networks were crucial elements during life's emergence, thereby offering a novel perspective on this long-standing question [ 1 , 7 ]. However, once it is accepted that autocatalysis is a central element in the process of abiogenesis, it follows that the study of autocatalytic systems in general may help uncover the principles that govern their chemical behaviour, regardless of their chemical detail. Indeed, as we will now describe, the generally accepted supposition that life's origins emerged from some prebiotic autocatalytic process can be shown to lead to broad insights into the chemistry–biology connection and to the surprising revelation that the processes of abiogenesis and biological evolution are directly related to one another. Once established, that connection will enable the underlying principles that governed the emergence of life on the Earth to be uncovered without undue reliance on speculative historic suppositions regarding the precise nature of those prebiotic systems.

5. A previously unrecognized stability kind: dynamic kinetic stability

The realization that the autocatalytic character of the replication reaction can lead to exponential growth and is unsustainable has been long appreciated, going back at least to Thomas Malthus's classic treatise ‘An essay on the principle of population’, published in 1798 [ 21 ]. But the chemical consequences of that long-recognized powerful kinetic character, although described by Lotka already a century ago [ 22 ], do not seem to have been adequately appreciated. Recently, one of us (A.P.) has described a new stability kind in nature, seemingly overlooked in modern scientific thought, which we have termed dynamic kinetic stability ( DKS ) [ 1 , 7 , 23 , 24 ] . That stability kind, applicable solely to persistent replicating systems, whether chemical or biological, derives directly from the powerful kinetic character and the inherent unsustainability of the replication process. However, for the replication reaction to be kinetically unsustainable, the reverse reaction, in which the replicating system reverts back to its component building blocks, must be very slow when compared with the forward reaction; the replication reaction must be effectively irreversible. That condition, in turn, means the system must be maintained in a far-from-equilibrium state [ 25 ], and that continuing requirement is satisfied through the replicating system being open and continually fed activated component building blocks. Note that the above description is consistent with Prigogine's non-equilibrium thermodynamic approach, which stipulates that self-organized behaviour is associated with irreversible processes within the nonlinear regime [ 26 ]. From the above, it follows that the DKS term would not be applicable to an equilibrium mixture of some oligomeric replicating entity together with its interconverting component building blocks.

Given the above discussion, it is apparent that the DKS concept is quite distinct from the conventional stability kind in nature, thermodynamic stability. A key feature of DKS is that it characterizes populations of replicators , rather than the individual replicators which make up those populations. Individual replicating entities are inherently unstable , as reflected in their continual turnover, whereas a population of replicators can be remarkably stable, as expressed by the persistence of some replicating populations. Certain life forms (e.g. cyanobacteria) express this stability kind in dramatic fashion, having been able to maintain a conserved function and a readily recognized morphology over billions of years. Indeed, within the world of replicators, there is theoretical and empirical evidence for a selection rule that in some respects parallels the second law of thermodynamics in that less stable replicating systems tend to become transformed into more stable ones [ 1 , 8 ]. This stability kind, which is applicable to all persistent replicating systems, whether chemical or biological, is then able to place biological systems within a more general physico-chemical framework, thereby enabling a physico-chemical merging of replicating chemical systems with biological ones. Studies in systems chemistry in recent years have provided empirical support for such a view by demonstrating that chemical and biological replicators show remarkably similar reactivity patterns, thereby reaffirming the existence of a common underlying framework linking chemistry to biology [ 1 , 7 ].

6. Extending Darwinian theory to inanimate chemical systems

The recognition that a distinctly different stability kind, DKS, is applicable to both chemical and biological replicators, together with the fact that both replicator kinds express similar reaction characteristics, leads to the profound conclusion that the so-called chemical phase leading to simplest life and the biological phase appear to be one continuous physico-chemical process, as illustrated in scheme 1 .

Unification of abiogenesis and biological evolution into a single continuous process governed by the drive toward greater DKS.

That revelation is valuable as it offers insights into abiogenesis from studies in biological evolution and, vice versa, it can provide new insights into the process of biological evolution from systems chemistry studies of simple replicating systems. A single continuous process necessarily means one set of governing principles, which in turn means that the two seemingly distinct processes of abiogenesis and evolution can be combined and addressed in concert. Significantly, that merging of chemistry and biology suggests that a general theory of evolution, expressed in physico-chemical terms rather than biological ones and applicable to both chemical and biological systems, may be formulated. Its essence may be expressed as follows: All stable ( persistent ) replicating systems will tend to evolve over time towards systems of greater DKS. As we have described in some detail in previous publications, there are both empirical and theoretical grounds for believing that oligomeric replicating systems which are less stable (less persistent) will tend to be transformed into more stable (more persistent) forms [ 1 , 7 , 8 , 24 ]. In fact that selection rule is just a particular application of the more general law of nature, almost axiomatic in character, that systems of all kinds tend from less stable to more stable. That law is inherent in the very definition of the term ‘stability’. So within the global selection rule in nature, normally articulated by the second law of thermodynamics, we can articulate a formulation specific to replicative systems, both chemical and biological— from DKS less stable to DKS more stable . A moment's thought then suggests that the Darwinian concept of ‘fitness maximization’ (i.e. less fit to more fit) is just a more specific expression of that general replicative rule as applied specifically to biological replicators. Whereas, in Darwinian terms, we say that living systems evolve to maximize fitness, the general theory is expressed in physico-chemical terms and stipulates that stable replicating systems, whether chemical or biological, tend to evolve so as to increase their stability, their DKS. Of course such a formulation implies that DKS is quantifiable. As we have previously discussed, quantification is possible, but only for related replicators competing for common resources, for example, a set of structurally related replicating molecules, or a set of genetically related bacterial life forms [ 1 , 7 ]. More generally, when assessing the DKS of replicating systems in a wider sense, one frequently must make do with qualitative or, at best, semi-quantitative measures.

Note that the general theory should not be considered as just one of changing terminology—‘DKS’ replacing ‘fitness’, ‘kinetic selection’ replacing ‘natural selection’. The physico-chemical description offers new insights as it allows the characterization of both the driving force and the mechanisms of evolution in more fundamental terms. The driving force is the drive of replicating systems towards greater stability, but the stability kind that is applicable in the replicative world. In fact that driving force can be thought of as a kind of second law analogue, though, as noted, the open character of replicating systems makes its quantification more difficult. And the mechanisms by which that drive is expressed can now be specified. These are complexification and selection , the former being largely overlooked in the traditional Darwinian view, while the latter is, of course, central to that view. A striking insight from this approach to abiogenesis follows directly: just as Darwinian theory broadly explained biological evolution, so an extended theory of evolution encompassing both chemical and biological replicators can be considered as broadly explaining abiogenesis. Thus, life on the Earth appears to have emerged through the spontaneous emergence of a simple (unidentified) replicating system, initially fragile, which complexified and evolved towards complex replicating systems exhibiting greater DKS. In fact, we would claim that in the very broadest of terms, the physico-chemical basis of abiogenesis can be considered explained.

But does that simplistic explanation for abiogenesis imply that the OOL problem can be considered resolved? Far from it. Let us now consider why.

7. What is still to be learned?

While Darwin's revolutionary theory changed our understanding of how biological systems relate to one another through the simple concept of natural selection, the Darwinian view has undergone considerable refinement and elaboration since its proposal over 150 years ago. First the genomic revolution, which provided Darwin's ideas with a molecular basis through the first decades of the twentieth century, transformed the subject and led to the neo-Darwinian synthesis, an amalgamation of classic Darwinism with population genetics and then with molecular genetics. But in more recent years, there is a growing realization that a molecular approach to understanding evolutionary dynamics is insufficient, that evolutionary biology's more fundamental challenge is to address the unresolved problem of complexity. How did biological complexity come about, and how can that complexity and its dynamic nature be understood? Our point is that Darwin's monumental thesis, with natural selection at its core, was just the beginning of a long process of refinement and elaboration, which has continued unabated to the present day.

Precisely the same process will need to operate with respect to the OOL problem. The DKS concept, simple in essence, does outline in the broadest terms the physico-chemical basis for abiogenesis. But that broad outline needs to be elaborated on through experimental investigation, so that the detailed mechanisms by which the DKS of simple chemical replicating systems could increase would be clarified. Already at this early stage, central elements of those mechanisms are becoming evident. Thus, there are preliminary indications that the process of abiogenesis was one of DKS enhancement through complexification [ 1 , 7 ]. More complex replicating systems, presenting a diversity of features and functions, appear to be able to replicate more effectively than simpler ones, and so are likely to be more stable in DKS terms (though this should not be interpreted to mean that any form of complexification will necessarily lead to enhanced DKS). The pertinent question is then: how does that process of complexification manifest itself? And this is where systems chemistry enters the scene [ 9 – 11 ]. By studying the dynamics of simple replicating molecular systems and the networks they establish, studies in system chemistry are beginning to offer insights into that process of replicative complexification. Following on from earlier work by Sievers & von Kiedrowski [ 27 ] and Lee et al . [ 28 ], more recent studies on RNA replicating systems by Lincoln & Joyce [ 29 ] and most recently by Vaidya et al . [ 30 ] suggest that network formation is crucial. Thus, Lincoln & Joyce [ 28 ] observed that a molecular network based on two cross-catalysing RNAs replicated rapidly and could be sustained indefinitely. By contrast, the most effective single molecule RNA replicator replicated slowly and was not sustainable. But in a more recent landmark experiment, Vaidya et al . [ 30 ] demonstrated that a cooperative cycle made up of three self-replicating RNAs could out-compete those same RNAs acting as individual replicators. The conclusion seems clear: molecular networks are more effective in establishing self-sustainable autocatalytic systems than single molecule replicators, just as was postulated by Eigen & Schuster [ 25 ] some 40 years ago.

Many key questions remain unanswered, however. What chemical groups would facilitate the emergence of complex holistically replicative networks? Are nucleic acids essential for the establishment of such networks, or could other chemical groups also express this capability? Is template binding the main mechanism by which molecular autocatalysis can take place, or can holistically autocatalytic sets be established through cycle closure without a reliance on template binding? How would the emergence of individual self-replicating entities within a larger holistically replicative network contribute to the stability of the network as a whole? How do kinetic and thermodynamic factors inter-relate in facilitating the maintenance of dynamically stable, but thermodynamically unstable, replicating systems [ 12 , 13 ]? As these questions suggest, our understanding of central issues remains rudimentary, and the road to discovery will probably be long and arduous. However, the key point of this essay has been to note that just as Darwin's simple concept of natural selection was able to provide a basis for an ongoing research programme in evolution, one that has been central to biological research for over 150 years, so the DKS concept may be able to offer a basis for ongoing studies in systems chemistry, one that may offer new insights into the rules governing evolutionary dynamics in simple replicating systems and, subsequently, for replicating systems of all kinds. Such a research programme, we believe, promises to further clarify the underlying relationship linking chemical and biological replicators.

In conclusion, it seems probably that we will never know the precise historic path by which life on the Earth emerged, but, very much in the Darwinian tradition, it seems we can now specify the essence of the ahistoric principles by which that process came about. Just as Darwin, in the very simplest of terms, pointed out how natural selection enabled simple life to evolve into complex life, so the recently proposed general theory of evolution [ 1 , 7 ] points out in simplest terms how simple, but fragile, replicating systems could have complexified into the intricate chemical systems of life. But, as discussed earlier, a detailed understanding of that process will have to wait until ongoing studies in systems chemistry reveal both the classes of chemical materials and the kinds of chemical pathways that simple replicating systems are able to follow in their drive towards greater complexity and replicative stability.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The Meaning of Life

Many major historical figures in philosophy have provided an answer to the question of what, if anything, makes life meaningful, although they typically have not put it in these terms (with such talk having arisen only in the past 250 years or so, on which see Landau 1997). Consider, for instance, Aristotle on the human function, Aquinas on the beatific vision, and Kant on the highest good. Relatedly, think about Koheleth, the presumed author of the Biblical book Ecclesiastes, describing life as “futility” and akin to “the pursuit of wind,” Nietzsche on nihilism, as well as Schopenhauer when he remarks that whenever we reach a goal we have longed for we discover “how vain and empty it is.” While these concepts have some bearing on happiness and virtue (and their opposites), they are straightforwardly construed (roughly) as accounts of which highly ranked purposes a person ought to realize that would make her life significant (if any would).

Despite the venerable pedigree, it is only since the 1980s or so that a distinct field of the meaning of life has been established in Anglo-American-Australasian philosophy, on which this survey focuses, and it is only in the past 20 years that debate with real depth and intricacy has appeared. Two decades ago analytic reflection on life’s meaning was described as a “backwater” compared to that on well-being or good character, and it was possible to cite nearly all the literature in a given critical discussion of the field (Metz 2002). Neither is true any longer. Anglo-American-Australasian philosophy of life’s meaning has become vibrant, such that there is now way too much literature to be able to cite comprehensively in this survey. To obtain focus, it tends to discuss books, influential essays, and more recent works, and it leaves aside contributions from other philosophical traditions (such as the Continental or African) and from non-philosophical fields (e.g., psychology or literature). This survey’s central aim is to acquaint the reader with current analytic approaches to life’s meaning, sketching major debates and pointing out neglected topics that merit further consideration.

When the topic of the meaning of life comes up, people tend to pose one of three questions: “What are you talking about?”, “What is the meaning of life?”, and “Is life in fact meaningful?”. The literature on life's meaning composed by those working in the analytic tradition (on which this entry focuses) can be usefully organized according to which question it seeks to answer. This survey starts off with recent work that addresses the first, abstract (or “meta”) question regarding the sense of talk of “life’s meaning,” i.e., that aims to clarify what we have in mind when inquiring into the meaning of life (section 1). Afterward, it considers texts that provide answers to the more substantive question about the nature of meaningfulness (sections 2–3). There is in the making a sub-field of applied meaning that parallels applied ethics, in which meaningfulness is considered in the context of particular cases or specific themes. Examples include downshifting (Levy 2005), implementing genetic enhancements (Agar 2013), making achievements (Bradford 2015), getting an education (Schinkel et al. 2015), interacting with research participants (Olson 2016), automating labor (Danaher 2017), and creating children (Ferracioli 2018). In contrast, this survey focuses nearly exclusively on contemporary normative-theoretical approaches to life’s meanining, that is, attempts to capture in a single, general principle all the variegated conditions that could confer meaning on life. Finally, this survey examines fresh arguments for the nihilist view that the conditions necessary for a meaningful life do not obtain for any of us, i.e., that all our lives are meaningless (section 4).

1. The Meaning of “Meaning”

2.1. god-centered views, 2.2. soul-centered views, 3.1. subjectivism, 3.2. objectivism, 3.3. rejecting god and a soul, 4. nihilism, works cited, classic works, collections, books for the general reader, other internet resources, related entries.

One of the field's aims consists of the systematic attempt to identify what people (essentially or characteristically) have in mind when they think about the topic of life’s meaning. For many in the field, terms such as “importance” and “significance” are synonyms of “meaningfulness” and so are insufficiently revealing, but there are those who draw a distinction between meaningfulness and significance (Singer 1996, 112–18; Belliotti 2019, 145–50, 186). There is also debate about how the concept of a meaningless life relates to the ideas of a life that is absurd (Nagel 1970, 1986, 214–23; Feinberg 1980; Belliotti 2019), futile (Trisel 2002), and not worth living (Landau 2017, 12–15; Matheson 2017).

A useful way to begin to get clear about what thinking about life’s meaning involves is to specify the bearer. Which life does the inquirer have in mind? A standard distinction to draw is between the meaning “in” life, where a human person is what can exhibit meaning, and the meaning “of” life in a narrow sense, where the human species as a whole is what can be meaningful or not. There has also been a bit of recent consideration of whether animals or human infants can have meaning in their lives, with most rejecting that possibility (e.g., Wong 2008, 131, 147; Fischer 2019, 1–24), but a handful of others beginning to make a case for it (Purves and Delon 2018; Thomas 2018). Also under-explored is the issue of whether groups, such as a people or an organization, can be bearers of meaning, and, if so, under what conditions.

Most analytic philosophers have been interested in meaning in life, that is, in the meaningfulness that a person’s life could exhibit, with comparatively few these days addressing the meaning of life in the narrow sense. Even those who believe that God is or would be central to life’s meaning have lately addressed how an individual’s life might be meaningful in virtue of God more often than how the human race might be. Although some have argued that the meaningfulness of human life as such merits inquiry to no less a degree (if not more) than the meaning in a life (Seachris 2013; Tartaglia 2015; cf. Trisel 2016), a large majority of the field has instead been interested in whether their lives as individual persons (and the lives of those they care about) are meaningful and how they could become more so.

Focusing on meaning in life, it is quite common to maintain that it is conceptually something good for its own sake or, relatedly, something that provides a basic reason for action (on which see Visak 2017). There are a few who have recently suggested otherwise, maintaining that there can be neutral or even undesirable kinds of meaning in a person’s life (e.g., Mawson 2016, 90, 193; Thomas 2018, 291, 294). However, these are outliers, with most analytic philosophers, and presumably laypeople, instead wanting to know when an individual’s life exhibits a certain kind of final value (or non-instrumental reason for action).

Another claim about which there is substantial consensus is that meaningfulness is not all or nothing and instead comes in degrees, such that some periods of life are more meaningful than others and that some lives as a whole are more meaningful than others. Note that one can coherently hold the view that some people’s lives are less meaningful (or even in a certain sense less “important”) than others, or are even meaningless (unimportant), and still maintain that people have an equal standing from a moral point of view. Consider a consequentialist moral principle according to which each individual counts for one in virtue of having a capacity for a meaningful life, or a Kantian approach according to which all people have a dignity in virtue of their capacity for autonomous decision-making, where meaning is a function of the exercise of this capacity. For both moral outlooks, we could be required to help people with relatively meaningless lives.

Yet another relatively uncontroversial element of the concept of meaningfulness in respect of individual persons is that it is logically distinct from happiness or rightness (emphasized in Wolf 2010, 2016). First, to ask whether someone’s life is meaningful is not one and the same as asking whether her life is pleasant or she is subjectively well off. A life in an experience machine or virtual reality device would surely be a happy one, but very few take it to be a prima facie candidate for meaningfulness (Nozick 1974: 42–45). Indeed, a number would say that one’s life logically could become meaningful precisely by sacrificing one’s well-being, e.g., by helping others at the expense of one’s self-interest. Second, asking whether a person’s existence over time is meaningful is not identical to considering whether she has been morally upright; there are intuitively ways to enhance meaning that have nothing to do with right action or moral virtue, such as making a scientific discovery or becoming an excellent dancer. Now, one might argue that a life would be meaningless if, or even because, it were unhappy or immoral, but that would be to posit a synthetic, substantive relationship between the concepts, far from indicating that speaking of “meaningfulness” is analytically a matter of connoting ideas regarding happiness or rightness. The question of what (if anything) makes a person’s life meaningful is conceptually distinct from the questions of what makes a life happy or moral, although it could turn out that the best answer to the former question appeals to an answer to one of the latter questions.

Supposing, then, that talk of “meaning in life” connotes something good for its own sake that can come in degrees and that is not analytically equivalent to happiness or rightness, what else does it involve? What more can we say about this final value, by definition? Most contemporary analytic philosophers would say that the relevant value is absent from spending time in an experience machine (but see Goetz 2012 for a different view) or living akin to Sisyphus, the mythic figure doomed by the Greek gods to roll a stone up a hill for eternity (famously discussed by Albert Camus and Taylor 1970). In addition, many would say that the relevant value is typified by the classic triad of “the good, the true, and the beautiful” (or would be under certain conditions). These terms are not to be taken literally, but instead are rough catchwords for beneficent relationships (love, collegiality, morality), intellectual reflection (wisdom, education, discoveries), and creativity (particularly the arts, but also potentially things like humor or gardening).

Pressing further, is there something that the values of the good, the true, the beautiful, and any other logically possible sources of meaning involve? There is as yet no consensus in the field. One salient view is that the concept of meaning in life is a cluster or amalgam of overlapping ideas, such as fulfilling higher-order purposes, meriting substantial esteem or admiration, having a noteworthy impact, transcending one’s animal nature, making sense, or exhibiting a compelling life-story (Markus 2003; Thomson 2003; Metz 2013, 24–35; Seachris 2013, 3–4; Mawson 2016). However, there are philosophers who maintain that something much more monistic is true of the concept, so that (nearly) all thought about meaningfulness in a person’s life is essentially about a single property. Suggestions include being devoted to or in awe of qualitatively superior goods (Taylor 1989, 3–24), transcending one’s limits (Levy 2005), or making a contribution (Martela 2016).

Recently there has been something of an “interpretive turn” in the field, one instance of which is the strong view that meaning-talk is logically about whether and how a life is intelligible within a wider frame of reference (Goldman 2018, 116–29; Seachris 2019; Thomas 2019; cf. Repp 2018). According to this approach, inquiring into life’s meaning is nothing other than seeking out sense-making information, perhaps a narrative about life or an explanation of its source and destiny. This analysis has the advantage of promising to unify a wide array of uses of the term “meaning.” However, it has the disadvantages of being unable to capture the intuitions that meaning in life is essentially good for its own sake (Landau 2017, 12–15), that it is not logically contradictory to maintain that an ineffable condition is what confers meaning on life (as per Cooper 2003, 126–42; Bennett-Hunter 2014; Waghorn 2014), and that often human actions themselves (as distinct from an interpretation of them), such as rescuing a child from a burning building, are what bear meaning.

Some thinkers have suggested that a complete analysis of the concept of life’s meaning should include what has been called “anti-matter” (Metz 2002, 805–07, 2013, 63–65, 71–73) or “anti-meaning” (Campbell and Nyholm 2015; Egerstrom 2015), conditions that reduce the meaningfulness of a life. The thought is that meaning is well represented by a bipolar scale, where there is a dimension of not merely positive conditions, but also negative ones. Gratuitous cruelty or destructiveness are prima facie candidates for actions that not merely fail to add meaning, but also subtract from any meaning one’s life might have had.

Despite the ongoing debates about how to analyze the concept of life’s meaning (or articulate the definition of the phrase “meaning in life”), the field remains in a good position to make progress on the other key questions posed above, viz., of what would make a life meaningful and whether any lives are in fact meaningful. A certain amount of common ground is provided by the point that meaningfulness at least involves a gradient final value in a person’s life that is conceptually distinct from happiness and rightness, with exemplars of it potentially being the good, the true, and the beautiful. The rest of this discussion addresses philosophical attempts to capture the nature of this value theoretically and to ascertain whether it exists in at least some of our lives.

2. Supernaturalism

Most analytic philosophers writing on meaning in life have been trying to develop and evaluate theories, i.e., fundamental and general principles, that are meant to capture all the particular ways that a life could obtain meaning. As in moral philosophy, there are recognizable “anti-theorists,” i.e., those who maintain that there is too much pluralism among meaning conditions to be able to unify them in the form of a principle (e.g., Kekes 2000; Hosseini 2015). Arguably, though, the systematic search for unity is too nascent to be able to draw a firm conclusion about whether it is available.

The theories are standardly divided on a metaphysical basis, that is, in terms of which kinds of properties are held to constitute the meaning. Supernaturalist theories are views according to which a spiritual realm is central to meaning in life. Most Western philosophers have conceived of the spiritual in terms of God or a soul as commonly understood in the Abrahamic faiths (but see Mulgan 2015 for discussion of meaning in the context of a God uninterested in us). In contrast, naturalist theories are views that the physical world as known particularly well by the scientific method is central to life’s meaning.

There is logical space for a non-naturalist theory, according to which central to meaning is an abstract property that is neither spiritual nor physical. However, only scant attention has been paid to this possibility in the recent Anglo-American-Australasian literature (Audi 2005).

It is important to note that supernaturalism, a claim that God (or a soul) would confer meaning on a life, is logically distinct from theism, the claim that God (or a soul) exists. Although most who hold supernaturalism also hold theism, one could accept the former without the latter (as Camus more or less did), committing one to the view that life is meaningless or at least lacks substantial meaning. Similarly, while most naturalists are atheists, it is not contradictory to maintain that God exists but has nothing to do with meaning in life or perhaps even detracts from it. Although these combinations of positions are logically possible, some of them might be substantively implausible. The field could benefit from discussion of the comparative attractiveness of various combinations of evaluative claims about what would make life meaningful and metaphysical claims about whether spiritual conditions exist.

Over the past 15 years or so, two different types of supernaturalism have become distinguished on a regular basis (Metz 2019). That is true not only in the literature on life’s meaning, but also in that on the related pro-theism/anti-theism debate, about whether it would be desirable for God or a soul to exist (e.g., Kahane 2011; Kraay 2018; Lougheed 2020). On the one hand, there is extreme supernaturalism, according to which spiritual conditions are necessary for any meaning in life. If neither God nor a soul exists, then, by this view, everyone’s life is meaningless. On the other hand, there is moderate supernaturalism, according to which spiritual conditions are necessary for a great or ultimate meaning in life, although not meaning in life as such. If neither God nor a soul exists, then, by this view, everyone’s life could have some meaning, or even be meaningful, but no one’s life could exhibit the most desirable meaning. For a moderate supernaturalist, God or a soul would substantially enhance meaningfulness or be a major contributory condition for it.

There are a variety of ways that great or ultimate meaning has been described, sometimes quantitatively as “infinite” (Mawson 2016), qualitatively as “deeper” (Swinburne 2016), relationally as “unlimited” (Nozick 1981, 618–19; cf. Waghorn 2014), temporally as “eternal” (Cottingham 2016), and perspectivally as “from the point of view of the universe” (Benatar 2017). There has been no reflection as yet on the crucial question of how these distinctions might bear on each another, for instance, on whether some are more basic than others or some are more valuable than others.

Cross-cutting the extreme/moderate distinction is one between God-centered theories and soul-centered ones. According to the former, some kind of connection with God (understood to be a spiritual person who is all-knowing, all-good, and all-powerful and who is the ground of the physical universe) constitutes meaning in life, even if one lacks a soul (construed as an immortal, spiritual substance that contains one’s identity). In contrast, by the latter, having a soul and putting it into a certain state is what makes life meaningful, even if God does not exist. Many supernaturalists of course believe that God and a soul are jointly necessary for a (greatly) meaningful existence. However, the simpler view, that only one of them is necessary, is common, and sometimes arguments proffered for the complex view fail to support it any more than the simpler one.

The most influential God-based account of meaning in life has been the extreme view that one’s existence is significant if and only if one fulfills a purpose God has assigned. The familiar idea is that God has a plan for the universe and that one’s life is meaningful just to the degree that one helps God realize this plan, perhaps in a particular way that God wants one to do so. If a person failed to do what God intends her to do with her life (or if God does not even exist), then, on the current view, her life would be meaningless.

Thinkers differ over what it is about God’s purpose that might make it uniquely able to confer meaning on human lives, but the most influential argument has been that only God’s purpose could be the source of invariant moral rules (Davis 1987, 296, 304–05; Moreland 1987, 124–29; Craig 1994/2013, 161–67) or of objective values more generally (Cottingham 2005, 37–57), where a lack of such would render our lives nonsensical. According to this argument, lower goods such as animal pleasure or desire satisfaction could exist without God, but higher ones pertaining to meaning in life, particularly moral virtue, could not. However, critics point to many non-moral sources of meaning in life (e.g., Kekes 2000; Wolf 2010), with one arguing that a universal moral code is not necessary for meaning in life, even if, say, beneficent actions are (Ellin 1995, 327). In addition, there are a variety of naturalist and non-naturalist accounts of objective morality––and of value more generally––on offer these days, so that it is not clear that it must have a supernatural source in God’s will.

One recurrent objection to the idea that God’s purpose could make life meaningful is that if God had created us with a purpose in mind, then God would have degraded us and thereby undercut the possibility of us obtaining meaning from fulfilling the purpose. The objection harks back to Jean-Paul Sartre, but in the analytic literature it appears that Kurt Baier was the first to articulate it (1957/2000, 118–20; see also Murphy 1982, 14–15; Singer 1996, 29; Kahane 2011; Lougheed 2020, 121–41). Sometimes the concern is the threat of punishment God would make so that we do God’s bidding, while other times it is that the source of meaning would be constrictive and not up to us, and still other times it is that our dignity would be maligned simply by having been created with a certain end in mind (for some replies to such concerns, see Hanfling 1987, 45–46; Cottingham 2005, 37–57; Lougheed 2020, 111–21).

There is a different argument for an extreme God-based view that focuses less on God as purposive and more on God as infinite, unlimited, or ineffable, which Robert Nozick first articulated with care (Nozick 1981, 594–618; see also Bennett-Hunter 2014; Waghorn 2014). The core idea is that for a finite condition to be meaningful, it must obtain its meaning from another condition that has meaning. So, if one’s life is meaningful, it might be so in virtue of being married to a person, who is important. Being finite, the spouse must obtain his or her importance from elsewhere, perhaps from the sort of work he or she does. This work also must obtain its meaning by being related to something else that is meaningful, and so on. A regress on meaningful conditions is present, and the suggestion is that the regress can terminate only in something so all-encompassing that it need not (indeed, cannot) go beyond itself to obtain meaning from anything else. And that is God. The standard objection to this relational rationale is that a finite condition could be meaningful without obtaining its meaning from another meaningful condition. Perhaps it could be meaningful in itself, without being connected to something beyond it, or maybe it could obtain its meaning by being related to something else that is beautiful or otherwise valuable for its own sake but not meaningful (Nozick 1989, 167–68; Thomson 2003, 25–26, 48).

A serious concern for any extreme God-based view is the existence of apparent counterexamples. If we think of the stereotypical lives of Albert Einstein, Mother Teresa, and Pablo Picasso, they seem meaningful even if we suppose there is no all-knowing, all-powerful, and all-good spiritual person who is the ground of the physical world (e.g., Wielenberg 2005, 31–37, 49–50; Landau 2017). Even religiously inclined philosophers have found this hard to deny these days (Quinn 2000, 58; Audi 2005; Mawson 2016, 5; Williams 2020, 132–34).

Largely for that reason, contemporary supernaturalists have tended to opt for moderation, that is, to maintain that God would greatly enhance the meaning in our lives, even if some meaning would be possible in a world without God. One approach is to invoke the relational argument to show that God is necessary, not for any meaning whatsoever, but rather for an ultimate meaning. “Limited transcendence, the transcending of our limits so as to connect with a wider context of value which itself is limited, does give our lives meaning––but a limited one. We may thirst for more” (Nozick 1981, 618). Another angle is to appeal to playing a role in God’s plan, again to claim, not that it is essential for meaning as such, but rather for “a cosmic significance....intead of a significance very limited in time and space” (Swinburne 2016, 154; see also Quinn 2000; Cottingham 2016, 131). Another rationale is that by fulfilling God’s purpose, we would meaningfully please God, a perfect person, as well as be remembered favorably by God forever (Cottingham 2016, 135; Williams 2020, 21–22, 29, 101, 108). Still another argument is that only with God could the deepest desires of human nature be satisfied (e.g., Goetz 2012; Seachris 2013, 20; Cottingham 2016, 127, 136), even if more surface desires could be satisfied without God.

In reply to such rationales for a moderate supernaturalism, there has been the suggestion that it is precisely by virtue of being alone in the universe that our lives would be particularly significant; otherwise, God’s greatness would overshadow us (Kahane 2014). There has also been the response that, with the opportunity for greater meaning from God would also come that for greater anti-meaning, so that it is not clear that a world with God would offer a net gain in respect of meaning (Metz 2019, 34–35). For example, if pleasing God would greatly enhance meaning in our lives, then presumably displeasing God would greatly reduce it and to a comparable degree. In addition, there are arguments for extreme naturalism (or its “anti-theist” cousin) mentioned below (sub-section 3.3).

Notice that none of the above arguments for supernaturalism appeals to the prospect of eternal life (at least not explicitly). Arguments that do make such an appeal are soul-centered, holding that meaning in life mainly comes from having an immortal, spiritual substance that is contiguous with one’s body when it is alive and that will forever outlive its death. Some think of the afterlife in terms of one’s soul entering a transcendent, spiritual realm (Heaven), while others conceive of one’s soul getting reincarnated into another body on Earth. According to the extreme version, if one has a soul but fails to put it in the right state (or if one lacks a soul altogether), then one’s life is meaningless.

There are three prominent arguments for an extreme soul-based perspective. One argument, made famous by Leo Tolstoy, is the suggestion that for life to be meaningful something must be worth doing, that something is worth doing only if it will make a permanent difference to the world, and that making a permanent difference requires being immortal (see also Hanfling 1987, 22–24; Morris 1992, 26; Craig 1994). Critics most often appeal to counterexamples, suggesting for instance that it is surely worth your time and effort to help prevent people from suffering, even if you and they are mortal. Indeed, some have gone on the offensive and argued that helping people is worth the sacrifice only if and because they are mortal, for otherwise they could invariably be compensated in an afterlife (e.g., Wielenberg 2005, 91–94). Another recent and interesting criticism is that the major motivations for the claim that nothing matters now if one day it will end are incoherent (Greene 2021).

A second argument for the view that life would be meaningless without a soul is that it is necessary for justice to be done, which, in turn, is necessary for a meaningful life. Life seems nonsensical when the wicked flourish and the righteous suffer, at least supposing there is no other world in which these injustices will be rectified, whether by God or a Karmic force. Something like this argument can be found in Ecclesiastes, and it continues to be defended (e.g., Davis 1987; Craig 1994). However, even granting that an afterlife is required for perfectly just outcomes, it is far from obvious that an eternal afterlife is necessary for them, and, then, there is the suggestion that some lives, such as Mandela’s, have been meaningful precisely in virtue of encountering injustice and fighting it.

A third argument for thinking that having a soul is essential for any meaning is that it is required to have the sort of free will without which our lives would be meaningless. Immanuel Kant is known for having maintained that if we were merely physical beings, subjected to the laws of nature like everything else in the material world, then we could not act for moral reasons and hence would be unimportant. More recently, one theologian has eloquently put the point in religious terms: “The moral spirit finds the meaning of life in choice. It finds it in that which proceeds from man and remains with him as his inner essence rather than in the accidents of circumstances turns of external fortune....(W)henever a human being rubs the lamp of his moral conscience, a Spirit does appear. This Spirit is God....It is in the ‘Thou must’ of God and man’s ‘I can’ that the divine image of God in human life is contained” (Swenson 1949/2000, 27–28). Notice that, even if moral norms did not spring from God’s commands, the logic of the argument entails that one’s life could be meaningful, so long as one had the inherent ability to make the morally correct choice in any situation. That, in turn, arguably requires something non-physical about one’s self, so as to be able to overcome whichever physical laws and forces one might confront. The standard objection to this reasoning is to advance a compatibilism about having a determined physical nature and being able to act for moral reasons (e.g., Arpaly 2006; Fischer 2009, 145–77). It is also worth wondering whether, if one had to have a spiritual essence in order to make free choices, it would have to be one that never perished.

Like God-centered theorists, many soul-centered theorists these days advance a moderate view, accepting that some meaning in life would be possible without immortality, but arguing that a much greater meaning would be possible with it. Granting that Einstein, Mandela, and Picasso had somewhat meaningful lives despite not having survived the deaths of their bodies (as per, e.g., Trisel 2004; Wolf 2015, 89–140; Landau 2017), there remains a powerful thought: more is better. If a finite life with the good, the true, and the beautiful has meaning in it to some degree, then surely it would have all the more meaning if it exhibited such higher values––including a relationship with God––for an eternity (Cottingham 2016, 132–35; Mawson 2016, 2019, 52–53; Williams 2020, 112–34; cf. Benatar 2017, 35–63). One objection to this reasoning is that the infinity of meaning that would be possible with a soul would be “too big,” rendering it difficult for the moderate supernaturalist to make sense of the intution that a finite life such as Einstein’s can indeed count as meaningful by comparison (Metz 2019, 30–31; cf. Mawson 2019, 53–54). More common, though, is the objection that an eternal life would include anti-meaning of various kinds, such as boredom and repetition, discussed below in the context of extreme naturalism (sub-section 3.3).

3. Naturalism

Recall that naturalism is the view that a physical life is central to life’s meaning, that even if there is no spiritual realm, a substantially meaningful life is possible. Like supernaturalism, contemporary naturalism admits of two distinguishable variants, moderate and extreme (Metz 2019). The moderate version is that, while a genuinely meaningful life could be had in a purely physical universe as known well by science, a somewhat more meaningful life would be possible if a spiritual realm also existed. God or a soul could enhance meaning in life, although they would not be major contributors. The extreme version of naturalism is the view that it would be better in respect of life’s meaning if there were no spiritual realm. From this perspective, God or a soul would be anti-matter, i.e., would detract from the meaning available to us, making a purely physical world (even if not this particular one) preferable.

Cross-cutting the moderate/extreme distinction is that between subjectivism and objectivism, which are theoretical accounts of the nature of meaningfulness insofar as it is physical. They differ in terms of the extent to which the human mind constitutes meaning and whether there are conditions of meaning that are invariant among human beings. Subjectivists believe that there are no invariant standards of meaning because meaning is relative to the subject, i.e., depends on an individual’s pro-attitudes such as her particular desires or ends, which are not shared by everyone. Roughly, something is meaningful for a person if she strongly wants it or intends to seek it out and she gets it. Objectivists maintain, in contrast, that there are some invariant standards for meaning because meaning is at least partly mind-independent, i.e., obtains not merely in virtue of being the object of anyone’s mental states. Here, something is meaningful (partially) because of its intrinsic nature, in the sense of being independent of whether it is wanted or intended; meaning is instead (to some extent) the sort of thing that merits these reactions.

There is logical space for an orthogonal view, according to which there are invariant standards of meaningfulness constituted by what all human beings would converge on from a certain standpoint. However, it has not been much of a player in the field (Darwall 1983, 164–66).

According to this version of naturalism, meaning in life varies from person to person, depending on each one’s variable pro-attitudes. Common instances are views that one’s life is more meaningful, the more one gets what one happens to want strongly, achieves one’s highly ranked goals, or does what one believes to be really important (Trisel 2002; Hooker 2008). One influential subjectivist has recently maintained that the relevant mental state is caring or loving, so that life is meaningful just to the extent that one cares about or loves something (Frankfurt 1988, 80–94, 2004). Another recent proposal is that meaningfulness consists of “an active engagement and affirmation that vivifies the person who has freely created or accepted and now promotes and nurtures the projects of her highest concern” (Belliotti 2019, 183).

Subjectivism was dominant in the middle of the twentieth century, when positivism, noncognitivism, existentialism, and Humeanism were influential (Ayer 1947; Hare 1957; Barnes 1967; Taylor 1970; Williams 1976). However, in the last quarter of the twentieth century, inference to the best explanation and reflective equilibrium became accepted forms of normative argumentation and were frequently used to defend claims about the existence and nature of objective value (or of “external reasons,” ones obtaining independently of one’s extant attitudes). As a result, subjectivism about meaning lost its dominance. Those who continue to hold subjectivism often remain suspicious of attempts to justify beliefs about objective value (e.g., Trisel 2002, 73, 79, 2004, 378–79; Frankfurt 2004, 47–48, 55–57; Wong 2008, 138–39; Evers 2017, 32, 36; Svensson 2017, 54). Theorists are moved to accept subjectivism typically because the alternatives are unpalatable; they are reasonably sure that meaning in life obtains for some people, but do not see how it could be grounded on something independent of the mind, whether it be the natural or the supernatural (or the non-natural). In contrast to these possibilities, it appears straightforward to account for what is meaningful in terms of what people find meaningful or what people want out of their lives. Wide-ranging meta-ethical debates in epistemology, metaphysics, and the philosophy of language are necessary to address this rationale for subjectivism.

There is a cluster of other, more circumscribed arguments for subjectivism, according to which this theory best explains certain intuitive features of meaning in life. For one, subjectivism seems plausible since it is reasonable to think that a meaningful life is an authentic one (Frankfurt 1988, 80–94). If a person’s life is significant insofar as she is true to herself or her deepest nature, then we have some reason to believe that meaning simply is a function of those matters for which the person cares. For another, it is uncontroversial that often meaning comes from losing oneself, i.e., in becoming absorbed in an activity or experience, as opposed to being bored by it or finding it frustrating (Frankfurt 1988, 80–94; Belliotti 2019, 162–70). Work that concentrates the mind and relationships that are engrossing seem central to meaning and to be so because of the subjective elements involved. For a third, meaning is often taken to be something that makes life worth continuing for a specific person, i.e., that gives her a reason to get out of bed in the morning, which subjectivism is thought to account for best (Williams 1976; Svensson 2017; Calhoun 2018).

Critics maintain that these arguments are vulnerable to a common objection: they neglect the role of objective value (or an external reason) in realizing oneself, losing oneself, and having a reason to live (Taylor 1989, 1992; Wolf 2010, 2015, 89–140). One is not really being true to oneself, losing oneself in a meaningful way, or having a genuine reason to live insofar as one, say, successfully maintains 3,732 hairs on one’s head (Taylor 1992, 36), cultivates one’s prowess at long-distance spitting (Wolf 2010, 104), collects a big ball of string (Wolf 2010, 104), or, well, eats one’s own excrement (Wielenberg 2005, 22). The counterexamples suggest that subjective conditions are insufficient to ground meaning in life; there seem to be certain actions, relationships, and states that are objectively valuable (but see Evers 2017, 30–32) and toward which one’s pro-attitudes ought to be oriented, if meaning is to accrue.