- PERSONAL SKILLS

- Personal Skills for the Mind

Reflective Practice

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Personal Skills:

- A - Z List of Personal Skills

- Personal Development

- Career Management Skills

- Creative Thinking Skills

Check out our popular eBook now in its third edition.

The Skills You Need Guide to Life: Looking After Yourself

- Keeping Your Mind Healthy

- Improving Your Wellbeing

- Mindfulness

- Keeping a Diary or Journal

- Positive Thinking

- Self-Esteem

- Managing Your Internal Dialogue (Self-Dialogue)

- The Importance of Mindset

- Introducing Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP)

- Memory Skills

- What is Anxiety?

- 10 Steps to Overcome Social Anxiety

- What is Depression?

- Treatments for Depression

- Types of Depression

- Understanding Dyslexia

- Understanding Dyscalculia

- Understanding Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- Understanding Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Understanding Dyspraxia

- How To Adult: 9 Essential Skills to Learn as a Young Adult

- Teenagers and Mental Health

- Eating Disorders

- Gender Identity and Body Dysphoria

- Perimenopause and Health

- Managing Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD)

- Status Anxiety

- Social Media and Mental Health

- Problematic Smartphone Use

- 10 Benefits of Spending Time Alone

- Emotional Intelligence

- Stress and Stress Management

- Anger and Aggression

- Assertiveness

- Caring for Your Body

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

What is Reflective Practice?

Reflective practice is, in its simplest form, thinking about or reflecting on what you do. It is closely linked to the concept of learning from experience, in that you think about what you did, and what happened, and decide from that what you would do differently next time.

Thinking about what has happened is part of being human. However, the difference between casual ‘thinking’ and ‘reflective practice’ is that reflective practice requires a conscious effort to think about events, and develop insights into them. Once you get into the habit of using reflective practice, you will probably find it useful both at work and at home.

Reflective Practice as a Skill

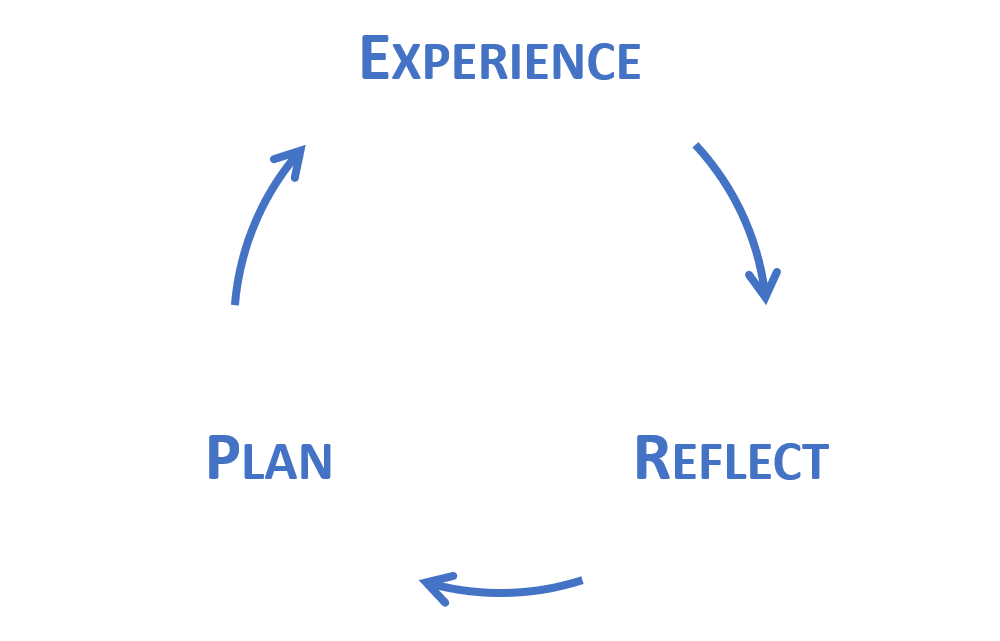

Various academics have touched on reflective practice and experiential learning to a greater or lesser extent over the years, including Chris Argyris (the person who coined the term ‘double-loop learning’ to explain the idea that reflection allows you to step outside the ‘single loop’ of ‘Experience, Reflect, Conceptualise, Apply’ into a second loop to recognise a new paradigm and re-frame your ideas in order to change what you do).

They all seem to agree that reflective practice is a skill which can be learned and honed, which is good news for most of us.

Reflective practice is an active, dynamic action-based and ethical set of skills, placed in real time and dealing with real, complex and difficult situations.

Moon, J. (1999), Reflection in Learning and Professional Development: Theory and Practice, Kogan Page, London.

Academics also tend to agree that reflective practice bridges the gap between the ‘high ground’ of theory and the ‘swampy lowlands’ of practice. In other words, it helps us to explore theories and to apply them to our experiences in a more structured way. These can either be formal theories from academic research, or your own personal ideas. It also encourages us to explore our own beliefs and assumptions and to find solutions to problems.

Developing and Using Reflective Practice

What can be done to help develop the critical, constructive and creative thinking that is necessary for reflective practice?

Neil Thompson, in his book People Skills , suggests that there are six steps:

Read - around the topics you are learning about or want to learn about and develop

Ask - others about the way they do things and why

Watch - what is going on around you

Feel - pay attention to your emotions, what prompts them, and how you deal with negative ones

Talk - share your views and experiences with others in your organisation

Think - learn to value time spent thinking about your work

In other words, it’s not just the thinking that’s important. You also have to develop an understanding of the theory and others’ practice too, and explore ideas with others.

Reflective practice can be a shared activity: it doesn’t have to be done alone. Indeed, some social psychologists have suggested that learning only occurs when thought is put into language, either written or spoken. This may explain why we are motivated to announce a particular insight out loud, even when by ourselves! However, it also has implications for reflective practice, and means that thoughts not clearly articulated may not endure.

It can be difficult to find opportunities for shared reflective practice in a busy workplace. Of course there are some obvious ones, such as appraisal interviews, or reviews of particular events, but they don’t happen every day. So you need to find other ways of putting insights into words.

Although it can feel a bit contrived, it can be helpful, especially at first, to keep a journal of learning experiences. This is not about documenting formal courses, but about taking everyday activities and events, and writing down what happened, then reflecting on them to consider what you have learned from them, and what you could or should have done differently. It’s not just about changing: a learning journal and reflective practice can also highlight when you’ve done something well.

Take a look at our page What is Learning? to find out more about the cycle of learning (PACT) and the role that reflection (or ‘Considering’) plays in it.

In your learning journal, it may be helpful to work through a simple process, as below. Once you get more experienced, you will probably find that you want to combine steps, or move them around, but this is likely to be a good starting point.

The Benefits of Reflective Practice

Reflective practice has huge benefits in increasing self-awareness, which is a key component of emotional intelligence , and in developing a better understanding of others. Reflective practice can also help you to develop creative thinking skills , and encourages active engagement in work processes.

In work situations, keeping a learning journal, and regularly using reflective practice, will support more meaningful discussions about career development, and your personal development, including at personal appraisal time. It will also help to provide you with examples to use in competency-based interview situations.

See our pages on Organising Skills and Strategic Thinking to find out more about how taking time to think and plan is essential for effective working and good time management, and for keeping your strategy on track. This is an example of the use of reflective practice, with the focus on what you’re going to do and why.

Reflective practice is one of the easiest things to drop when the pressure is on, yet it’s one of the things that you can least afford to drop, especially under those circumstances. Time spent on reflective practice will ensure that you are focusing on the things that really matter, both to you and to your employer or family.

To Conclude

Reflective practice is a tool for improving your learning both as a student and in relation to your work and life experiences. Although it will take time to adopt the technique of reflective practice, it will ultimately save you time and energy.

Further Reading from Skills You Need

The Skills You Need Guide to Personal Development

Learn how to set yourself effective personal goals and find the motivation you need to achieve them. This is the essence of personal development, a set of skills designed to help you reach your full potential, at work, in study and in your personal life.

The second edition of or bestselling eBook is ideal for anyone who wants to improve their skills and learning potential, and it is full of easy-to-follow, practical information.

Continue to: Keeping a Diary or Journal Journaling for Personal Development: Creating a Learning Journal

See also: Learning Approaches Living Ethically Personal Development

- Deakin University

- Learning and Teaching

Critical reflection for assessments and practice

- Reflective practice

Critical reflection for assessments and practice: Reflective practice

- Critical reflection

- How to reflect

- Critical reflection writing

- Recount and reflect

What is reflective practice?

"In general, reflective practice is understood as the process of learning through and from experience towards gaining new insights of self and/or practice. This often involves examining assumptions of everyday practice."

Linda Finlay - Reflecting on 'Reflective practice' (2008)

Reflection is critical to being a conscious, effective practitioner in any discipline. The important thing to keep in mind is that reflecting by itself is not reflective practice. Practice is tied into active, impactful change that emerges from deep reflective learning .

Thinking and doing

Reflective practice is the act of thinking about your experiences in order to learn from them to shape what you do in the future. It therefore includes all aspects of your practice (e.g. relationships, interactions, learning, assessments, behaviours, and environments). It also includes examining how your practice is influenced by your own world views and gaining insights and other perspectives to inform future decision making.

Why reflect?

Reflective practice benefits you on both professional and personal levels. Using critical reflection as a tool can give you insight and positively impact your study, your wellbeing and your worklife. Click the plus icons (+) to view some benefits of reflective practice.

When to critically reflect?

Critical reflection connects to past, current and future action. Click on each of the flip cards to learn the time-related actions you need to do as part of reflective practice.

Reflective practice and critical reflection

Reflective practice is part of your mindset and everyday doing for both uni and the workplace. The process also relies on using critical reflection as a tool to analyse your reflections and which allows you to evaluate, inform and continually change your practice.

Explore the infographic below for a visual depiction of the reflective practice and critical reflection relationship.

- Reflective practice infographic

Critical reflection and areas of your practice

Reflective practice relies on your ability to be open to change and to consider relevant evidence that can challenge or inform decision making. Critical reflection is what allows you to deeply understand your study or work practice and then to take actions to improve it.

You should critically reflect on all aspects of your practice including:

Reflective practice and you

How would you define reflective practice for yourself? There's no right or wrong answer to this question because it's so contextual. The way you enact reflective practice is tied to you and how you think, feel and do. We know that writing down or verbalising your thinking can help you better understand what something means to you. With that in mind...

Take a few moments to think about how you define reflective practice. You can then record yourself using the interactive audio activity below and download the soundbyte. Any recording you make is only available to you. Keep this definition in mind as you move through this critical reflection guide.

- << Previous: Homepage

- Next: Critical reflection >>

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2024 4:53 PM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/critical-reflection-guide

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Professional Practice - The Process of Reflective Practice

Reflective Practice

A presentation to assist in understanding Reflective Practice

Related Papers

Ulrich's Bimonthly, March-April 2008

Werner Ulrich

The aim of the series of "Reflections on Reflective Practice," which begins with the present introductory article, is to explore the potential of practical philosophy to become a new, third pillar of reflective professional practice, in addition to today's "reflective practice" mainstream (the focus of which is on psychological rather than philosophical and methodological issues of competent practice) and the conception of "applied science" (which tends to neglect the normative side of competent practice). The essay offers a critique of the soft (psychological) bent of the notion of reflective practice as it has developed in the professional education literature. It is found to neglect essential challenges that professional education faces today, and to have actually become the "reflective practice" literature's blind spot.

Fernando Batista

"Maybe reflective practices offer us a way of trying to make sense of the uncertainty in our workplaces and the courage to work competently and ethically at the edge of order and chaos…" (Ghaye, 2000, p.7) Reflective practice has burgeoned over the last few decades throughout various fields of professional practice and education. In some professions it has become one of the defining features of competence, even if on occasion it has been adopted-mistakenly and unreflectively-to rationalise existing practice. The allure of the 'reflection bandwagon' lies in the fact that it 'rings true' (Loughran, 2000). Within different disciplines and intellectual traditions, however, what is understood by 'reflective practice' varies considerably (Fook et al, 2006). Multiple and contradictory understandings of reflective practice can even be found within the same discipline. Despite this, some consensus has been achieved amid the profusion of definitions. In general, reflective practice is understood as the process of learning through and from experience towards gaining new insights of self and/or practice (Boud et al 1985; Boyd and Fales, 1983; Mezirow, 1981, Jarvis, 1992). This often involves examining assumptions of everyday practice. It also tends to involve the individual practitioner in being self-aware and critically evaluating their own responses to practice situations. The point is to recapture practice experiences and mull them over critically in order to gain new understandings and so improve future practice. This is understood as part of the process of lifelong learning. Beyond these broad areas of agreement, however, contention and difficulty reign. There is debate about the extent to which practitioners should focus on themselves as individuals rather than the larger social context. There are questions about how, when, where and why reflection should take place. For busy professionals short on time, reflective practice is all too easily applied in bland, mechanical, unthinking ways,

Reflective Practice and Professional Development

Development of professional practice through reflection, including an originally created model of reflection.

The Veterinary Nurse

Samantha Fontaine

Physiotherapy

Lynn Clouder

Elizabeth Anne Kinsella

Journal of In-service Education

Ruth Leitch

Cisca Domingo

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health

Colin Boreham

Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

Laynee Laube

Knowledge-Based Theory and Practice

MIRIAM DELGADO VERDE

Revista Brasileira de Engenharia de Biossistemas

Mohamad Rabai

Australian Economic Papers

Iman Gareeboo

Aires Camões

Revista Verde de …

Vinicius campos

Physics Letters B

Piotr Koczon

Maseeh uz Zaman

donasi bukubekas

Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal

Valentina Yu

Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies

Riane Eisler

IRJET Journal

- Mathematics

Jamilu Abubakar

Azafea: Revista de Filosofía

Fernando Gilabert

New Journal of Physics - NEW J PHYS

Serkan Karabacak

Current Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities

Akbikesh WM

Open Journal of Nursing

Naohiro Hohashi

Alternativas

Karol Revilla Escobar

Atasan Kebaya Motif Modern Rumah Jahit Azka

rumahjahitazka kebumen

Journal of Bone and Mineral Research

Reinhold Erben

"Sea-lions of the World: Conservation and Research in the 21st Century”. 22nd Wakefield Fisheries Symposium.

Dr. Carlos Yaipen-Llanos

Aminah Abdullah

办理Sheridandiploma feh

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Effectiviology

Reflective Practice: Thinking About the Way You Do Things

- Reflective practice involves actively analyzing your experiences and actions, in order to help yourself improve and develop.

For example, an athlete can engage in reflective practice by thinking about mistakes that they made during a training session, and figuring out ways to avoid making those mistakes in the future.

Reflective practice can be beneficial in various situations, so it’s worthwhile to understand this concept. As such, in the following article you will learn more about reflective practice, and see how you can engage in it yourself, as well as what you can do to encourage others to engage in it.

Examples of reflective practice

An example of reflective practice is an athlete who, after every practice, thinks about what they did well, what they did badly, why they did things the way they did, and what they can do in the future to improve their performance.

In addition, examples of reflective practice appear in a variety of other domains. For instance:

- A student can engage in reflective practice by thinking about how they studied for a recent test and how they ended up performing, in order to figure out how they can study more effectively next time.

- A medical professional can engage in reflective practice by thinking about a recent procedure that they performed, in order to identify mistakes that they’ve made and figure out how to avoid making those mistakes in the future.

- A human-resources representative can engage in reflective practice by thinking about recent interviews that they conducted with potential new hires, in order to determine whether all the steps in the interview are necessary, and whether any other steps are needed.

The benefits of reflective practice

There are many potential benefits to reflective practice. These include , most notably, the following:

- Acquisition of new knowledge.

- Refinement of existing knowledge, for example by correcting current misconceptions.

- An improved understanding of the connections between theory and practice.

- An improved understanding of the rationale behind your actions, in terms of factors such as why you do the things that you do, and why you do things a certain way.

- Improvement of your goals and of the rules that you use for decision-making (this is also associated with the concept of double-loop learning ).

- A better understanding of yourself, in terms of factors such as your strengths and weaknesses.

- Development of your metacognitive abilities, for example when it comes to your ability to analyze your thoughts more effectively.

- Increased feelings of autonomy, competence, and control.

- Increased motivation to act.

- Improved performance, for example due to learning how to take action in a more effective way, or due to having more motivation to take action.

These benefits can apply not only to the specific domain in which you engage in reflective practice, but also to other domains. For example, if a musician engages in reflective practice with regard to how they play their instrument, they might improve their understanding of their preferences as a learner, which could help them when it comes to their academic studies.

Finally, note that in some cases, reflective practice is viewed as not only beneficial, but outright crucial to people’s goals. As one scholar notes:

“It is not sufficient simply to have an experience in order to learn. Without reflecting upon this experience it may quickly be forgotten or its learning potential lost. It is from the feelings and thoughts emerging from this reflection that generalisations or concepts can be generated. And it is generalisations which enable new situations to be tackled effectively. Similarly, if it is intended that behaviour should be changed by learning, it is not sufficient simply to learn new concepts and develop new generalisations. This learning must be tested out in new situations. The learner must make the link between theory and action by planning for that action, carrying it out, and then reflecting upon it, relating what happens back to the theory.” — From “Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods” by Graham Gibbs (1988)

Overall, there are many potential benefits to reflective practice, including a better understanding of the rationale behind your actions, increased feelings of control, and improved performance, and these benefits can extend to additional domains beyond the one in which you engaged in reflective practice.

How to engage in reflective practice

Broadly, reflective practice involves thinking about how you do things, and trying to understand why you do what you do, and what you can do better. As such, there are many ways you can engage in it, and different approaches to reflective practice will work better for different people under different circumstances.

One notable way to engage in reflective practice is to ask guiding questions. For example, when it comes to reflective practice in the context of a recent event, you can ask yourself the following:

- How did I feel while the event was happening?

- What were my goals?

- What were the main things that I did?

- What went well?

- What went badly?

- What should I do the same way next time?

- What should I do differently next time?

Similarly, you can engage in reflective practice through reflective writing , which can also take various forms, such as answering guiding questions, creating a detailed narrative of a recent event, or sketching a diagram to analyze your thoughts. This can be beneficial when it comes to improving your ability to reflect, and it also has the added benefit of giving you the option to review your original reflections, especially if you collect your writings in a consistent location, such as a reflection journal.

When deciding how to engage in reflective practice, it’s crucial to find the specific approaches that work best for you in your particular situation. This means, for example, that if you try to engage in reflective writing but consistently find that thinking aloud works better for you, then it’s perfectly acceptable to do that instead. Similarly, while peer feedback can facilitate reflection in some cases, it can also hinder it in others, so you should use it only if you find that it helps you.

Finally, keep in mind that it’s generally more difficult and time-consuming in the short-term to engage in reflective practice than to act without reflection, especially when it comes to reflecting as events are unfolding , and this can make people prone to avoiding reflection. Furthermore, the difficulties of reflective practice sometimes make it impractical, meaning that people must avoid it in certain situations. However, in cases where it’s possible to engage in reflection in a reasonable manner, doing so often ends up being beneficial in the long-term, both when it comes to performance, as well as when it comes to related benefits, such as personal growth.

Overall, you can engage in reflective practice in various ways, such as by asking yourself guiding questions about your actions, or by writing about your experiences. Different approaches to reflective practice will work better for different people under different circumstances, so you should try various approaches until you find the ones that work best for you.

The reflective cycle

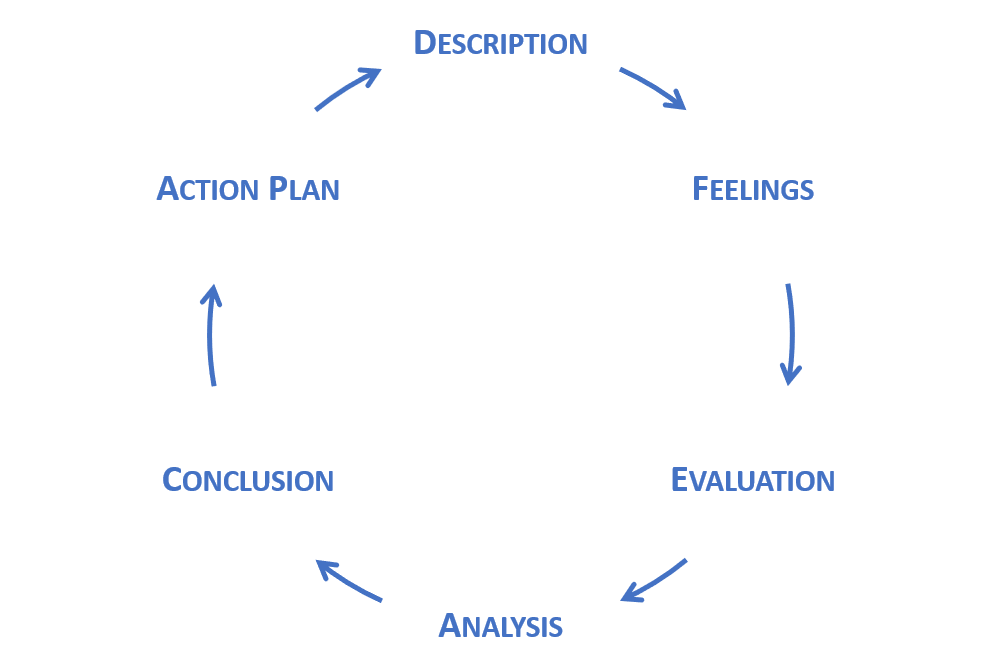

Gibbs’ reflective cycle is a process for guiding reflective practice. It involves the following steps, in order:

- Description. Describe what happened, without judgment or analysis. For example, you can ask yourself where you were, who else was present, and what happened.

- Feelings. Describe how you felt, what you were thinking, and how you feel now, again without judgment or analysis.

- Evaluation. Evaluate everything that happened, for example, by asking yourself what went well and what went badly.

- Analysis. Analyze the situation, to try and make sense of everything that happened. For example, you can ask yourself why the things that went well went well, why the things that went badly went badly, and why you acted the way that you did.

- Conclusion. Draw conclusions based on the information that you generated so far. Start with general conclusions, and then move on to specific ones that pertain to your particular situation. For example, you can start by forming general conclusions about how people act in certain situations, and then move on to form more specific conclusions about what that means for the type of situation that you’re in.

- Action plan. Figure out what you are going to do differently next time, based on everything that you’ve learned. For example, if you realize that things went badly because you’ve made a certain mistake as a result of carelessness, figure out how you’re going to act in the future to avoid making that mistake again.

Note : in addition to Gibbs’ reflective cycle, there are other models that can be used to guide reflective practice, such as Kolb’s experiential learning cycle . These models generally revolve around the concept of experiential learning , which is learning that is based on experience (i.e., “learning by doing”).

Types of reflection

A distinction can be drawn between three types of reflection, based on your temporal relation to the event that you’re reflecting about. Based on this distinction, there are three main types of reflection:

- Anticipatory reflection. Anticipatory reflection is reflection that’s performed before an event occurs. For example, this type of reflection can involve asking yourself what might happen, what challenges you’re likely to face, how should you respond, and what you can do to prepare.

- Reflection-in-action. Reflection-in-action is reflection that’s performed while an event is occurring. For example, this type of reflection can involve asking yourself what’s currently happening, whether things are going as expected, how you’re feeling, and whether there’s anything you should be doing differently.

- Reflection-on-action. Reflection-on-action is reflection that’s performed after an event has occurred. For example, this type of reflection can involve asking yourself what happened, what went well, and what you should have done differently.

These types of reflection are similar conceptually, though there are some minor differences between them. For example, when it comes to anticipatory reflection, you must rely on predictions of future experiences, rather than on those actual experiences or your recollections of them, though you can use your past experiences to inform those predictions. Similarly, when it comes to reflection-in-action, you might need to engage in reflection faster and while under heavier pressure, if you want to be able to use the reflect to inform your actions as the event in question unfolds.

Levels of reflection

You can engage in reflection in different ways and to different degrees . For example, when it comes to reflection, there’s a difference between simply asking yourself “did I do well?” and asking yourself “how well did I do, why did I do what I did, and what can I do better?”.

These different forms of reflection can be viewed as distinct from one another , and as different levels of reflection within a single hierarchy or continuum. A common example of how reflection might be categorized based on this is by differentiating between superficial reflection and deep reflection , where deep reflection involves reflection that is more in-depth in various ways.

From a practical perspective, what matters most is understanding that in different situations you might benefit from different levels of reflection. For example, in some cases, it might be preferable to engage in superficial reflection, and simply identify the fact that you’ve made a mistake, while in other cases, it might be preferable to engage in deep reflection, by figuring out why you’ve made a mistake and what you can do to avoid making it again.

Note : other terms are sometimes used to differentiate between superficial and deep reflection, such as shallow reflection or surface reflection (in place of superficial reflection ), and thorough reflection (in place of deep reflection ).

Using self-distancing to help reflection

In some cases, it can be beneficial to use self-distancing to aid the reflection process. This can help you get better insights into your actions, by reducing issues such as the egocentric bias , which can hinder reflection. To use self-distancing in this manner, you can do things such as the following:

- Ask yourself what advice would you give someone else if they were in the same situation as you.

- Avoid first-person language when considering your performance (e.g., instead of asking “what could I have done differently?”, ask “what could you have done differently?”).

- When considering events you were in, try to visualize them not only from your own perspective, but also from the perspective of other people involved, or from a general external perspective.

Reflective practice as a shared activity

It’s possible to engage in reflective practice as part of a shared activity. This type of reflection can take various forms, such as discussing your experiences with a group of other people, or having someone with expertise ask you guiding questions in order to help you reflect.

Shared reflective practice has both potential advantages and disadvantages. For example, shared reflection as part of a group might help people identify more issues with their actions than they would be able to identify by themself, as a result of being exposed to more perspectives. At the same time, however, this approach might also make the reflection process much more stressful for people who are shy.

Accordingly, it’s important to consider the potential advantages and disadvantages of the various approaches to reflective practice, when deciding whether to use shared practice in your particular circumstances, and if so then in what wait.

Note : a phenomenon that’s related to shared reflective practice is the protégé effect , which is a psychological phenomenon where teaching, pretending to teach, or preparing to teach information to others helps a person learn that information. Specifically, the protégé effect means that helping others engage in reflective practice can improve your own ability to do so, and can also help you when it comes to learning other things.

How to encourage reflective practice in others

To encourage others to engage in reflective practice, you can start by doing the following:

- Explain what reflective practice is.

- Explain why reflective practice is beneficial.

- Explain how to engage in reflective practice.

This can be guided by the material provided in the earlier sections of this article, on how to engage in reflective practice yourself.

Once you’ve done this, you can create an environment that is conducive to reflective practice, and help people engage in it, while keeping in mind that different people will benefit from different approaches to reflection. For example, some people might benefit from having someone go with them through each stage of the reflection cycle, while others will benefit more from simply being shown how reflection works and then being left to do reflect on their own.

Alternatively, you can also take a more externally driven approach to reflective practice, by guiding people through reflective practice, without fully explaining the concept to them.

Finally, note that you should generally avoid forcing the reflection process, or forcing people to “confess” what they’ve done wrong, since this can lead to ineffective reflection, as well as to various other issues. For example, when people know that they will be graded based on their responses during the reflection process, they might answer in a dishonest and strategic manner , by giving responses that they think the person evaluating them wants them to give. Similarly, this kind of forced reflection can also lead to issues such as increased stress, as well as increased hostility toward the reflection process and the people who guide it.

Accordingly, in cases where it’s possible and beneficial, you should allow people to make their reflections private. In addition, you should also avoid sticking to a strict reflection template in cases where doing so is counterproductive, and instead allow people to engage in reflection in the way that works best for them.

Related concepts

Two concepts that are often discussed in relation to reflective practice are reflexivity and critical reflection :

- R eflexivity describes people’s ability and tendency to display general self-awareness, and to consider themselves in relation to their environment.

- C ritical reflection describes an extensive and in-depth type of reflection, which involves being aware of how your assumptions affect you, as well as examining your actions and responsibilities from moral, ethical, and social perspectives.

In addition, another closely related concept is reflective learning , which involves actively monitoring your knowledge, abilities, and performance during the learning process, and assessing them in order to find ways to improve.

The terms reflective practice and reflective learning refer to similar concepts, and because their definitions vary and even overlap in certain sources , they are sometimes used interchangeably.

Nevertheless, one notable way to differentiate between them is to say that people engage in reflective learning with regard to events where learning is the main goal, and in reflective practice with regard to events where learning is not the main goal. For example, a nursing student might engage in reflective learning when learning how to perform a certain procedure, whereas an experienced nurse might engage in reflective practice while performing the same procedure as part of their everyday routine.

Alternatively, it’s possible to view reflective learning as a notable type of reflective practice, which revolves around improving one’s learning in particular.

Overall, there is no clear distinction between reflective practice and reflective learning, and these terms are sometimes used interchangeably. However, potential distinctions between these terms are generally not important from a practical perspective, since they are unlikely to influence how the underlying concepts are implemented in practice.

Summary and conclusions

- There are many potential benefits to reflective practice, including a better understanding of the rationale behind your actions, increased feelings of control, and improved performance, and these benefits can extend to additional domains beyond the one in which you engaged in reflective practice.

- You can vary the way you engage in reflective practice based on the circumstances, your preferences, and your goals; for example, in some cases, you might benefit from quick reflection as events are still unfolding, while in others you might benefit from more thorough reflection after an event has concluded.

- A notable process that you can use to engage in reflective practice is Gibbs’ reflective cycle , where you (1) describe what happened, (2) consider what you were feeling and thinking during your experience, (3) evaluate what was good or bad about it, (4) analyze what else you can make of the situation, (5) draw generalized and specialized conclusions, and (6) create an action plan for the future.

- To encourage others to engage in reflective practice, you can explain what it is, why it’s beneficial, and how they can engage in it, or help them engage in it directly, for example by asking them guiding questions.

Other articles you may find interesting:

- Reflective Learning: Thinking About the Way You Learn

- Knowledge-Telling and Knowledge-Building in Learning and Teaching

- Intentional Learning: Setting Learning as a Deliberate Goal

- Cambridge Libraries

Study Skills

Reflective practice toolkit.

- Introduction

- What is reflective practice?

- Everyday reflection

- Models of reflection

- Barriers to reflection

- Free writing

- Reflective writing exercise

- Bibliography

Who is this resource for?

Being able to reflect is a valuable skill to have both during your education and as you move on to the workplace. It helps you to think about your experiences, why things happened the way they did and how you can improve on these experiences in future. This resource will guide you through the basics of what reflective practice is, its benefits, how to integrate it into your everyday life and the basics of reflective writing.

This resource is designed to be flexible so you can use it in the best way for you. You can read the whole resource to guide you through from the basics to a selection of top tips for putting reflection into practice. If you are short on time you can follow one of the suggested pathways below:

Pathway 1: Beginners

- Why reflect?

- Models of reflection (focus on ERA and Driscoll models)

Pathway 2: Intermediate

- Reflective writing with exercise

Throughout the resource there are activities to get you thinking about reflective practice and how it might work for you.

- Next: What is reflective practice? >>

- Last Updated: Jun 21, 2023 3:24 PM

- URL: https://libguides.cam.ac.uk/reflectivepracticetoolkit

© Cambridge University Libraries | Accessibility | Privacy policy | Log into LibApps

The Ultimate Guide to Reflective Practice in Teaching

- Last updated: 12th May, 2024

Posted by: Rico Patzer

What is reflective practice in teaching?

The importance of reflection in teaching, the effect of reflective teaching in schools, 5 benefits of being a reflective teacher.

How to reflect on teaching: getting started

7 reflection activities for teachers

Using video for reflective practice: what the teachers say

Introduction

Good teachers reflect on what, why and how they do things in the classroom. Great teachers adapt as a result of this reflection, to continually improve their performance. In this guide we share everything you need to know about the benefits of reflective teaching, how to become more reflective and encourage others to do the same.

Naturally, most teachers will spend time thinking about what they did in the classroom, why they do certain things, and if it’s working.

Reflective practice is purposeful reflection at the heart of a structured cycle of self-observation and self-evaluation for continuous learning. It’s central to effective professional development (PD) and becoming a more highly skilled teacher.

“Reflective Practice”

Purposeful reflection at the heart of a structured cycle of self-observation and self-evaluation for continuous learning.

Teacher reflection helps you move from just experiencing a lesson, to understanding what happened and why.

Taking the time to reflect on and analyze your teaching practice helps you to identify more than just what worked and what didn’t. When reflecting with purpose, you can start to challenge the underlying principles and beliefs that define the way that you work.

This level of self-awareness is a powerful ally, especially when so much of what and how you teach can change in the moment.

If you don’t question what your experiences mean and think actively about them on an on-going basis, the evidence shows you are unlikely to improve.

Reflective practitioners can better ride the waves of change

Schools with a reflective teaching culture have an edge in times of rapid change. The shift to blended and online teaching as a result of Covid-19 in 2020 is a great example. Even the most experienced teachers found themselves in uncharted waters. Strategies needed to be reconsidered and delivery forms adapted to the new learning environment. Reflection, collaboration and iteration were critical skills and key for adapting quickly in challenging times.

Reflective cultures support excellence in teaching AND learning

A culture of reflective practice creates a strong foundation for continuously improving teaching and learning.

In an environment where teachers collectively question and adapt, draw on expertise and support one another – student learning benefits too. In fact, developing excellence in teaching has the greatest impact on student achievement.

Encouraging reflective practice in schools, not only benefits individual teachers but the school as a whole.

Developing a culture of reflective practice improves schools by creating a strong foundation for continuously improving teaching and learning. It sends the message that learning is important for both students and teachers, and that everyone is committed to supporting it.

Reflecting practice creates an environment of collaboration as teachers question and adapt both their own practice and that of their colleagues. Teachers can team-up, drawing on expertise and offer each other support. This helps to develop good practice across the school, resulting in a more productive working environment.

But reflective practice in teaching is not just important for teachers and schools.

Provide your teachers with opportunities for effective reflection:

The best teachers are reflective, and they’re also the first to say that their practice can always be improved. Here’s why it’s worth taking the time to reflect on your teaching regularly – and encouraging your colleagues to do the same:

1. Reflection is at the heart of effective professional development

If you don’t spend time giving purposeful thought to your professional practice you cannot improve. Once you take ownership of your CPD by actively reflecting, evaluating and iterating on your practice, your confidence will sky-rocket.

2. Remain relevant and innovative

Self reflection helps you to create and experiment with new ideas and approaches to ensure your teaching is relevant, fresh and impactful for your students.

3. Stay learner focused

Reflective practice will help you better understand your learners, their abilities and needs. By reflecting, you can better put yourself in your students’ shoes and see yourself through their eyes.

4. Developing reflective learners

Reflective teachers are more likely to develop reflective learners. If teachers practise reflection they can more effectively encourage learners to reflect on, analyse, evaluate and improve their own learning. These are key skills in developing them to become independent learners, highlighting the important role of teachers as reflective practitioners.

5. Humility

When you reflect you must be honest. At least honest with yourself about your choices, success, mistakes, and growth. Self-reflection acts as a constant reminder to stay humble and continue working hard to achieve results.

If you’d like to find out more about teacher reflection, download our FREE practical guide to ‘Enabling effective teacher reflection’.

How to reflect on teaching: getting started with reflective practice and tools to help

Do you want to get better at reflecting on your own teaching, or are you supporting colleagues to get started with reflective practice? Either way there’s some simple steps you can take.

Step 1: Gather insights

First, you need to gather information about what happens in the classroom, so it can be unpicked and analyzed. Here are some different ways you can do this

Keep a teacher diary/journal

After each lesson, write in a notebook or in the notes section of your phone about what happened. You could even send yourself a voice note. Note your reactions and feelings as well as those of the students. This relies on you remembering to do it, and your ability to recall the details, which means it’s not as thorough or reliable as other methods.

Invite a peer to observe

Invite colleagues to come into your class to collect information about your lesson and offer feedback. This may be with a simple observation task or through note-taking on a specific area you’ve said you’d like to reflect on. Of course, there are challenges with this approach. Timetabling is an obvious one, and another drawback is the potential for differing memories and perceptions about what went on in the lesson.

Record your lesson

A video recording of your lesson is valuable because it gives you an unaltered and unbiased view of how effective your lesson was from both a teacher and student perspective. A video also acts as an additional set of eyes to catch behaviors that you may not have spotted at the time. It also means you can come back to it at a convenient time, and watch a short clip, rather than having to remember to take notes or rely on your memory.

Have reflective discussions

Does videoing or analyzing your own practice feel like a big hurdle? A great starting point can be to simply get together in a small group (in-person or online) to watch a publicly available video of another teacher and then encourage discussions about the teaching and learning they’ve observed.

Get IRIS Connect for your school and provide your teachers with a powerful tool for video reflection:

Once you’ve gathered information on your lesson, the next step in reflecting on your teaching is to analyze it. But what should you be looking for? Here are some suggested reflection activities.

7 reflection activities for teachers:

The ratio of interaction

How much are children responding, versus how much are you talking to them? Is there a dialogue of learning in their classroom or is the talking one-sided?

G rowth vs. fixed mindset

The way you respond to your students can inspire either a fixed or growth mindset. Praising students for being ‘smart’ or ‘bright’ encourages fixed mindsets, whilst recognising when they have persistently worked hard promotes growth mindsets. Carol Dweck found that people with growth mindsets are generally more successful in life…so, which are you encouraging students to have? Read more about Carol Dweck’s theory of the growth mindset .

Consistent corrections

Are you correcting the students consistently? Teachers should avoid inconsistency; such as stopping a side conversation one day but ignoring it the next, as this causes confusion with students and the feeling that the teacher is being unfair.

Opportunities to respond

Are you giving your students enough opportunities to respond to what they are learning? Responses can include asking students to answer questions, promoting the use of resources such as whiteboards or asking students to discuss what they have learnt with their neighbor.

Type and level of questions

Do the questions being asked match the method of learning that you want to foster in their classroom? The type of questions you ask students can include open or closed, their opinion on certain topics, or right or wrong. Is the level of questions being asked appropriate for the students’ level of learning? To find out more about open questions read our blog: Questioning in the classroom.

Instructional vs. non-instructional time

The more students are engaged in learning activities, the more they will learn. Try to keep track of how much time they give to learning activities compared to how much is spent on other transitional things such as handing out resources or collecting work at the end of the lesson.

Teacher talk vs. student talk

Depending on the topic, decide how much students should be talking about what they’re learning compared with how much they should be talking to them.

David Rogers, a multi-award winning geography teacher and Deputy Headteacher at Focus Learning Trust, Hindhead says: “Video provided me with a powerful opportunity to reflect upon and develop my own practice based upon capturing what actually happened. Having led the adoption of lesson capture software in a number of settings, I know that these platforms are not for anyone to judge lessons. If you don’t believe me, video yourself and share the recording with colleagues.” Discover what else David learned from recording his practice here >

Assistant Headteacher Ryan Holmes says: “In the middle of the whirlwind of a teacher’s day, finding the opportunity to take a step back and reflect is not easy. I have found filming my lessons a valuable opportunity that provides me with the space I need to more objectively look back at my lessons, away from the hustle and bustle of the lesson itself. It is an opportunity to identify strengths and areas of improvement.” – Read more about Ryan Holmes experience here >

The IRIS Connect video technology enables teachers to easily capture their lessons and review an objective record of their teaching and learning. Using the IRIS Connect mobile app, teachers record their lessons which are automatically uploaded to a web platform. Once there they can privately view the videos and annotate their teaching practice using time-linked notes and analytical tools. If they choose too, they can also share their videos with trusted colleagues, inviting them to give their professional feedback and advice.

These videos become an invaluable resource for the individual teacher and wider school, allowing many teachers to benefit from the solutions of successful teachers.

Get blog notifications

Keep up to date with our latest professional learning blogs.

By clicking Subscribe you consent to us contacting you regarding our products and services, as well as other content that may be of interest to you. You also consent to us storing your personal data to provide you with the content you are requesting. You can unsubscribe at any time. To find out more about how we manage your data, please review our Privacy Policy.

Interested to find out more?

If you’d like to find out more about IRIS Connect and how our solution can help you to get the most out of your classroom observations and provide high qualitative PD for your teachers, get in touch!

- Video Technology

- Education Research

- Classroom Observations

- Technical Support

- Security & Safeguarding

- Support Hub

- Accessibility Statement

- Privacy Notice

- Cookie Policy - Website

© 2024 IRIS Connect US. All Rights Reserved.

Engaging in Reflective Practice: A Practical Guide

- First Online: 23 October 2020

Cite this chapter

- Andy Curtis 5

Part of the book series: Second Language Learning and Teaching ((SLLT))

841 Accesses

We begin this chapter by contemplating the question: What is Reflective Practice? and highlighting the important difference between just thinking about our teaching and systematically reflecting on our professional practices. In considering that opening question, we also recognize the multiplicity of meanings of Reflective Practice (RP), and the different ways of engaging in RP. In the same way that ‘one size does not fit all’ in teaching and learning, RP should reflect the individuality of the teacher and their different learners. Some notes on the history of RP are also given, followed by details of the practical aspects of doing RP, using different levels of self-questioning, combined with, for example, video-recording and co-teaching. In the last main part of the chapter, we consider some of the challenges of engaging in RP, and some ways of meeting those challenges.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bailey, K. M., Curtis, A., & Nunan, D. (1998). Undeniable insights: The collaborative use of three professional development practices. TESOL Quarterly, 32 (3), 546–556.

Google Scholar

Bailey, K. M., Curtis, A., & Nunan, D. (2001). Pursuing professional development: The self as source . Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Brunsting, N. C., Sreckovic, M. A., & Lane, K. L. (2014). Special education teacher burnout: A synthesis of research from 1979 to 2013. Education and Treatment of Children, 37 (4), 681–711.

Chang, M.-L. (2009). An appraisal perspective of teacher burnout: Examining the emotional work of teachers. Educational Psychology Review, 21 (3), 193–218.

Cheng, L. & Sun, Y. (2015). Teachers’ grading decision making: Multiple influencing factors and methods. Language Assessment Quarterly, 12 , 213–233.

Curtis, A. (1998). Teaching in the mirror: Self-reflection and self-development. Professional Perspectives, 3 (4), 1–2.

Curtis, A., & Cheng, L. (1998). Video as a source of data in classroom observation. ThaiTESOL Bulletin, 11 (2), 31–38.

Curtis, A. (2003). Paths to professional development: Part 3: Creating spaces and mapping relationships. The English Connection: Korea TESOL, 7 (2), 11.

Curtis, A., & Szestay, M. (2005). The impact of teacher knowledge seminars: Unpacking reflective practice. TESL-EJ, 9 (2), 1–16.

Curtis, A. (2012). Doing more with less: Using film in English language teaching and learning in China. Research on English Education, 英语教育研究, 1 (1), 1–10.

Curtis, A. (2017). Methods and methodologies for language teaching: The centrality of context . Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave MacMillan.

Famakinwa, J. O. (2012). Is the unexamined life worth living or not? Think, 11 (31), 97–103.

Article Google Scholar

Farrell, T. S. C. (2013). Reflective teaching . Alexandria, VA: TESOL Press.

Farrell, T. S. C. (2014). Reflective practice in ESL teacher development groups: From practices to principles . Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave MacMillan.

Farrell, T. S. C. (2015). Promoting teacher reflection in second language education: A framework for TESOL Professionals . New York, NY: Routledge.

Farrell, T. S. C. (2018). Research on reflective practice in TESOL . New York, NY: Routledge.

Freeman, D., & Johnson, K. (1998). Reconceptualizing the knowledge-base of language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 32 (3), 397–417.

Gaudin, C., & Chaliès, S. (2015). Video viewing in teacher education and professional development: A literature review. Educational Research Review, 16, 41–67.

Ghaye, T. (2000). Into the reflective mode: Bridging the stagnant moat. Reflective Practice, 1 (1), 5–9.

Greene, M. (1978). Landscapes of learning . New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Kim, H.-K. (2003). Critical thinking, learning and Confucius: A positive assessment. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 37 (1), 71–87.

Kong, F. (1979). The Analects . London, England: Penguin Classics.

Mann, S., & Walsh, S. (2017). Reflective practice in English language teaching: Research-based principles and practices . New York, NY: Routledge.

Marsh, B., & Mitchell, N. (2014). The role of video in teacher professional development. Teacher Development: An International Journal of Teachers’ Professional Development, 18 (3), 403–417.

McMillan, J. H. (2003). Understanding and improving teachers’ classroom assessment decision making: Implications for theory and practice. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practices, 22 (4), 34–43.

McMillan, D. J., McConnell, B., & O’Sullivan, H. (2016). Continuing professional development—Why bother? Perceptions and motivations of teachers in Ireland. Professional Development in Education, 42 (1), 150–167.

Newman, S. (1999). Constructing and critiquing reflective practice. Educational Action Research, 7 (1), 145–163.

Richards, J. C., & Lockhart, C. (1994). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Ripamonti, S., Galuppo, L., Gorli, M., Scaratti, G., & Cunliffe, A. L. (2015). Pushing action research toward reflexive practice. Journal of Management Inquiry, 25 (1), 55–68.

Rodgers, C. (1998). Reflection in second language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 32 (3), 610–613.

Sawyer, R. D. (2001). Teacher decision-making as a fulcrum for teacher development: Exploring structures of growth. Teacher Development: An International Journal of Teachers’ Professional Development, 5 (1), 39–58.

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2010). Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: A study of relations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26 (4), 1059–1069.

Stanley, C. (1998). A framework for teacher reflectivity. TESOL Quarterly, 32 (3), 584–591.

Trif, L. & Popescu, T. (2013). The reflective diary: An effective professional training instrument for future teachers. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences , 93 , 1070–1074.

Zimmerman, L. (2009). Reflective teaching practice: Engaging in praxis. Journal of Theory Construction & Testing, 13 (2), 46–50.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Anaheim University, California, USA

Andy Curtis

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Andy Curtis .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Dubai Men's College, Higher Colleges of Technology, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Christine Coombe

English Language Teaching and Learning, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Laie, HI, USA

Neil J Anderson

School of Education, The University of Notre Dame Australia, Sydney, Chippendale, NSW, Australia

Lauren Stephenson

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Curtis, A. (2020). Engaging in Reflective Practice: A Practical Guide. In: Coombe, C., Anderson, N.J., Stephenson, L. (eds) Professionalizing Your English Language Teaching. Second Language Learning and Teaching. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34762-8_20

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34762-8_20

Published : 23 October 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-34761-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-34762-8

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Getting started with Reflective Practice

Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning Team

What is reflective practice?

The process of reflection is a cycle which needs to be repeated. • Teach • Self-assess the effect your teaching has had on learning • Consider new ways of teaching which can improve the quality of learning • Try these ideas in practice • Repeat the process Reflective practice is ‘learning through and from experience towards gaining new insights of self and practice’ (Finlay, 2008). Reflection is a systematic reviewing process for all teachers which allows you to make links from one experience to the next, making sure your students make maximum progress. Reflection is a basic part of teaching and learning. It aims to make you more aware of your own professional knowledge and action by ‘challenging assumptions of everyday practice and critically evaluating practitioners’ own responses to practice situations’ (Finlay, 2008). The reflective process encourages you to work with others as you can share best practice and draw on others for support. Ultimately, reflection makes sure all students learn more effectively as learning can be tailored to them. In the rest of this unit, we will look at the basics of reflective practice in more detail. We will look at the research behind reflective practice, discuss the benefits and explore some practical examples. Throughout the unit, we will encourage you to think about how you can include reflective practice in your own classroom practice. Listen to these educators discussing what reflective practice means for them. How do their ideas about reflective practice compare with yours?

What are the benefits of reflective practice?

Reflective practice helps create confident teachers Reflective practice develops your ability to understand how your students learn and the best ways to teach them. By reflecting on your teaching, you identify any barriers to learning that your students have. You then create lessons which reteach any content which your students have not been able to access to allow them to overcome any obstacles and develop. Being reflective will also make sure you have a wider range of skills as you find new ways to teach. This will develop your confidence in the classroom as you find the best ways to deliver your knowledge of a subject. By reflecting, you will develop abilities to solve problems. Through questioning and changing the way you deliver your lessons, you will find new solutions and become more flexible with your teaching. It allows you to take time to assess and appreciate your own teaching. Reflective practice also helps create confident students. As a result of reflecting, students are challenged as you use new methods in the classroom. From reflection, you should encourage your students to take new challenges in learning, developing a secure and confident knowledge base. Reflective practice makes sure you are responsible for yourself and your students Reflecting on your teaching will help you to understand how your students best learn and will allow you to be accountable for their progress. By assessing the strengths and weaknesses in your own teaching, you will develop an awareness of the factors that control and prevent learning. The reflection process will also help you to understand yourself and the way you teach. By asking yourself questions and self-assessing, you will understand what your strengths are and any areas where development might be needed. Reflecting allows you to understand how you have helped others to achieve and what this looks like in a practical learning environment. By asking your students for their thoughts and feelings on the learning, they play an active part in the learning cycle. This allows them to take ownership of their learning and also work with you and give feedback, which creates self-aware and responsible students. Once the student starts to play an active part in the learning cycle, they become more aware of different learning styles and tasks. They become more aware of how they learn and they develop key skills and strategies to become lifelong learners. Reflective practice encourages innovation Reflective practice allows you to adapt lessons to suit your classes. You can create and experiment with new ideas and approaches to your teaching to gain maximum success. By varying learning and experimenting with new approaches, students have a richer learning experience. They will think more creatively, imaginatively and resourcefully, and be ready to adapt to new ways and methods of thinking. Reflective practice encourages engagement Being reflective helps you challenge your own practice as you will justify decisions and rationalise choices you have made. It encourages you to develop an understanding of different perspectives and viewpoints. These viewpoints might be those of students, focusing on their strengths, preferences and developments, or those of other colleagues, sharing best practice and different strategies. When you become more aware of your students’ preferences and strengths, learning becomes more tailored to their needs and so they are more curious and are equipped to explore more deeply. Reflective practice benefits all By reflecting, you create an environment which centres on the learner. This environment will support students and teachers all around you to become innovative, confident, engaged and responsible. Once you start the reflective process, your quality of teaching and learning will improve. You will take account of students’ various learning styles and individual needs, and plan new lessons based on these. Reflection helps focus on the learning process, so learning outcomes and results will improve as you reflect on how your learners are learning. By getting involved in the reflective process, you will create an environment of partnership-working as you question and adapt both your own practice and that of your students and other colleagues. The learning process then becomes an active one as you are more aware of what you want your students to achieve, delivering results which can be shared throughout the institution. By working with other colleagues and students, relationships become positive and demonstrate mutual respect. Students feel part of the learning cycle and are more self-aware. Colleagues can ‘team up’, drawing on expertise and support. This will develop the whole institution’s best practice. All of these things together result in a productive working environment. Listen to these educators giving their views on the benefits of reflective practice. Which of the benefits are most relevant to you and your colleagues?

Image captions

What is the research behind reflective practice?

Educational researchers have long promoted the importance of reflecting on practice to support student learning and staff development. There are many different models of reflective practice. However, they all share the same basic aim: to get the best results from the learning, for both the teacher and students. Each model of reflection aims to unpick learning to make links between the ‘doing’ and the ‘thinking’. Kolb's learning cycle David Kolb, educational researcher, developed a four-stage reflective model. Kolb’s Learning Cycle (1984) highlights reflective practice as a tool to gain conclusions and ideas from an experience. The aim is to take the learning into new experiences, completing the cycle. Kolb's cycle follows four stages. First, practitioners have a concrete experience. This means experiencing something new for the first time in the classroom. The experience should be an active one, used to test out new ideas and teaching methods. This is followed by… Observation of the concrete experience, then reflecting on the experience. Here practitioners should consider the strengths of the experience and areas of development. Practitioners need to form an understanding of what helped students’ learning and what hindered it. This should lead to… The formation of abstract concepts. The practitioner needs to make sense of what has happened. They should do this through making links between what they have done, what they already know and what they need to learn. The practitioner should draw on ideas from research and textbooks to help support development and understanding. They could also draw on support from other colleagues and their previous knowledge. Practitioners should modify their ideas or devise new approaches, based on what they have learnt from their observations and wider research. The final stage of this cycle is when… The practitioner considers how they are going to put what they have learnt into practice. The practitioner’s abstract concepts are made concrete as they use these to test ideas in future situations, resulting in new experiences. The ideas from the observations and conceptualisations are made into active experimentation as they are implemented into future teaching. The cycle is then repeated on this new method. Kolb’s model aims to draw on the importance of using both our own everyday experiences and educational research to help us improve. It is not simply enough for you to reflect. This reflection must drive a change which is rooted in educational research. Gibbs' reflective cycle The theoretical approach of reflection as a cyclical model was further developed by Gibbs (1998). This model is based on a six-stage approach, leading from a description of the experience through to conclusions and considerations for future events. While most of the core principles are similar to Kolb’s, Gibbs' model is broken down further to encourage the teacher to reflect on their own thoughts and feelings. Gibbs' model is an effective tool to help you reflect after the experience, and is a useful model if you are new to reflection as it is broken down into clearly defined sections. Description In this section, the practitioner should clearly outline the experience. This needs to be a factual account of what happened in the classroom. It should not be analytical at this stage. Feelings This section encourages the practitioner to explore any thoughts or feelings they had at the time of the event. Here the practitioner should explain feelings and give examples which directly reference the teaching experience. It is important the practitioner is honest with how they feel, even if these feelings might be negative. Only once the feelings have been identified can the practitioner implement strategies to overcome these barriers. Evaluation The evaluation section gives the opportunity for the practitioner to discuss what went well and analyse practice. It is also important to consider areas needed for development and things that did not work out as initially planned. This evaluation should consider both the practitioner’s learning and the students’ learning. Analysis This section is where the practitioner makes sense of the experience. They consider what might have helped the learning or hindered it. It is in this stage that the practitioner refers to any relevant literature or research to help make sense of the experience. For example, if you felt the instructions you gave were not clear, you could consult educational research on how to communicate effectively. Conclusion At this stage, the practitioner draws all the ideas together. They should now understand what they need to improve on and have some ideas on how to do this based on their wider research. Action plan During this final stage, the practitioner sums up all previous elements of this cycle. They create a step-by-step plan for the new learning experience. The practitioner identifies what they will keep, what they will develop and what they will do differently. The action plan might also outline the next steps needed to overcome any barriers, for example enrolling on a course or observing another colleague. In Gibbs' model the first three sections are concerned with what happened. The final three sections relate to making sense of the experience and how you, as the teacher, can improve on the situation. 'Reflection-in-action' and 'reflection-on-action' Another approach to reflection is the work by Schön. Schön (1991) distinguishes between reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. Reflection-in-action is reflection during the ‘doing’ stage (that is, reflecting on the incident while it can still benefit the learning). This is carried out during the lesson rather than reflecting on how you would do things differently in the future. This is an extremely efficient method of reflection as it allows you to react and change an event at the time it happens. For example, in the classroom you may be teaching a topic which you can see the students are not understanding. Your reflection-in-action allows you to understand why this has happened and how to respond to overcome this situation. Reflection-in-action allows you to deal with surprising incidents that may happen in a learning environment. It allows you to be responsible and resourceful, drawing on your own knowledge and allowing you to apply it to new experiences. It also allows for personalised learning as, rather than using preconceived ideas about what you should do in a particular situation, you decide what works best at that time for that unique experience and student. Reflection-on-action , on the other hand, involves reflecting on how practice can be developed after the lesson has been taught. Schön recognises the importance of reflecting back ‘in order to discover how our knowing-in-action may have contributed to an unexpected outcome’ (Schön, 1983). Reflection-on-action means you reflect after the event on how your knowledge of previous teaching may have directed you to the experience you had. Reflection-on-action should encourage ideas on what you need to change for the future. You carry out reflection-on-action outside the classroom, where you consider the situation again. This requires deeper thought, for example, as to why the students did not understand the topic. It encourages you to consider causes and options, which should be informed by a wider network of understanding from research. By following any of the above models of reflection, you will have a questioning approach to teaching. You will consider why things are as they are, and how they could be. You will consider the strengths and areas of development in your own practice, questioning why learning experiences might be this way and considering how to develop them. As a result, what you do in the classroom will be carefully planned, informed by research and previous experience, and focused, with logical reasons. All of these models stress the importance of repeating the cycle to make sure knowledge is secure and progression is continued.

Common misconceptions about reflective practice

‘It doesn’t directly impact my teaching if I think about things after I have done them’ Reflection is a cyclical process: do, analyse, adapt and repeat. The reflections you make will directly affect the next lesson or block of teaching as you plan to rework and reteach ideas. Ask yourself: What did not work? How can I adapt this idea for next time? This might mean redesigning a task, changing from group to paired work or reordering the lesson. ‘Reflection takes too long; I do not have the time’ Reflection can be done on the spot (Schön: reflection-in-action). You should be reflecting on things as they happen in the classroom. Ask yourself: What is working well? How? Why? What are the students struggling with? Why? Do the students fully understand my instructions? If not, why not? Do the students fully understand the task? If not, why not? Do your students ultimately understand what success looks like in the task or activity? Can they express this for themselves? ‘Reflection is only focused on me, it does not directly affect my students’ Reflecting and responding to your reflections will directly affect your students as you change and adapt your teaching. You will reteach and reassess the lessons you have taught, and this will allow students the chance to gain new skills and strengthen learning. Creating evaluation models will help you to know whether the actions you have taken have had the intended effect. ‘Reflection is a negative process’ Reflection is a cyclical process, meaning you grow and adapt. You should plan to draw on your own strengths and the best practice of colleagues, which you then apply to your own teaching. Try any of the reflection models listed in this unit to help you progress. By getting involved in a supportive network everyone will develop. 'Reflection is a solo process, so how will I know I’ve improved?’ Reflection is best carried out when part of a supportive network. You can draw on the support of colleagues by asking them to observe and give feedback. You can also draw on student feedback. Reflection should trigger discussion and co-operation.

Reflective practice in practice