Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

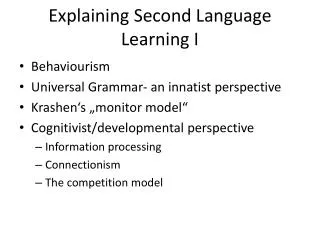

Explaining Second Language Learning

This is the slide presentation on explaining second language learning for master students in Teaching English as a Foreign Language Programme. Department of English Faculty of Letters National University of Laos

Related Papers

The Modern Language Journal

Claudia Gutierrez

Applied Linguistics

This book, a follow-up to the editors’ successful guide to second language (L2) teacher education (Burns and Richards 2009), is a clear and concise introduction to the research and scholarship across 36 topics related to learning English as an L2. Although the title indicates that the focus is on English, because many of the authors discuss L2 learning and second language acquisition (SLA) more generally, the book should find an audience with scholars who are interested in research on learning other languages as well.

Alexandria, VA: TESOL Press. ISBN 978-1-945351-04-4

Michael Lessard-Clouston

Second Language Acquisition Applied to English Language Teaching offers teachers of English language learners an overview of second language acquisition (SLA) theory while allowing readers to reflect on their own classroom practices. It defines SLA, outlines how it helps teachers understand their roles and those of learners in their classes, and introduces major concepts and issues. The book argues that input, output, and interaction are essential for English language learning and teaching, and touches on questions of age, anxiety, and error correction. Finally, SLA Applied to ELT encourages readers to use teaching materials that reflect SLA principles and explains what the field of SLA offers practicing English teachers, including encouragement. The book is written in a straightforward, easy-to read style, complete with reflection questions so that busy teachers can apply what they are reading to their own classroom teaching. As such, it’s a must have for any teacher who wants to understand student learning better so that they can teach their English language students effectively. [Note: The attached file includes the Table of Contents and a sample of Ch. 5.]

Lina Mukhopadhyay

Course Description The course will begin with a historical perspective on English Language Education (also commonly referred to as English Language Teaching) from ancient days of teaching the language like other classical languages as Greek and Latin up to the 21 st century trends. Basic principles and procedures of the most recognized and commonly used approaches and methods for teaching English as a second (or a foreign language) will be presented. These are the Grammar Translation Method, Direct Method, Audio-Lingual Method, Communicative Language Teaching, Content-Based Instruction and other alternative approaches. Each approach or method will be discussed in terms of their theoretical orientation, teaching practices and learning activities designed to reach the specified teaching goals and learning outcomes. Candidates will examine and analyze the teaching methods and compare whether the methods reflect similar or opposing views of language learning principles. Through course readings and sample video lessons, candidates will reflect on what constitutes language use, and the role of teacher and learners in each of the teaching methodologies. The analysis will help them to gain a fuller understanding of the principles and practices behind the choices teachers make regarding particular methods. In all, the course will enable learners to look for the rationale for the different techniques that have been used in the course of language teaching history and learn to critique the practices and materials designed to teach English and many unresolved issues in the domain. The course will not espouse any particular approach to second language teaching but rather present an overview of the many approaches to teaching second and foreign languages.

Syeda Bukhari

Lazaros Kikidis

Mark Feng Teng

Firda Bachmid

Language and Education

Nicole Ziegler

RELATED PAPERS

Psyche: A Journal of Entomology

Alfred F Newton

Clinical Immunology

Robert Colvin

Brazilian Journal of Health Review

Renata Ostrowski

Hugo Oliveira

Somtawin Jaritkhuan

Shabir Anant

Margherita Bertuccelli

Muhamad Alawi abdurohim

Merouane Rabhi

Conjectura filosofia e educação

Altair Alberto Fávero

Adi Prayitno

Knowing in Performing

Annegret Huber

TIN: Terapan Informatika Nusantara

chandra frenki sianturi

Juan Manuel Gutiérrez

Scientific Reports

Cheng Siang Tan

Widya Cahyadi

Luciana Abreu

Lissiana Nussifera

Comunicación, poder y pluralismo cultural. Discursos y desafíos en la esfera pública digital

Salvador Salazar

Turkish Studies-Educational Sciences

İdil Kefeli

Brain and Development

majed ahmadi

Frontiers in Energy Research

Ziad Bashir Ali

Alejandra Yommi

Journal of the American Planning Association

THOMAS DANIELS

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

These are the benefits of learning a second language

In the US, just 20% of students learn another language. Image: REUTERS/Christian Hartmann

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Sean Fleming

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Education is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

There are many advantages to learning a second language. Some are fairly obvious. If you find yourself lost in a foreign country, being able to express yourself clearly could help lead you to your destination. Similarly, if your job requires you to travel you may find it easier to vault language and cultural barriers.

But there are other benefits that are not so immediately apparent. For example, learning another language could improve your all-round cognitive ability. It could help hone your soft skills, and even increase your mastery of your mother tongue, too.

Some studies have apparently identified a link between being multilingual and fending off the onset of dementia . Others indicate that being able to speak more than one language can help you become better at multitasking in other aspects of your daily life, too.

Deciding on which additional language or languages to learn is often a matter of chance and personal preference. Maybe you have a parent or grandparent who is a native of another country, so you were brought up being able to speak their language. Perhaps your family regularly took vacations in a particular foreign country when you were a child and that sparked your interest. Or it could just be that you had a very engaging teacher who instilled in you a love for languages.

But deciding whether to learn one at all would appear to be determined more by your mother language than anything else. In short, native-born English speakers are far less likely to learn a second language than many other people.

In the US, just 20% of students learn a foreign language . Meanwhile, in parts of Europe that figure stands at 100%. Across the whole of Europe the median is 92%, and is at least 80% in 29 separate European countries investigated by Pew Research. In 15 of those 29, it’s 90% or more.

Down under, around 21% of people can use a second language , although only 73% of Australian households identified as English-speaking in the 2016 census. In Canada, only 6.2% of people speak something other than the country’s two official languages , English and French.

Have you read?

These are the world’s most spoken languages, our language needs to evolve alongside ai. here's how, here's why we like some words more than others.

In the UK, fewer school students are studying languages to exam levels at ages 16 or 18. Since 2013, the numbers of studying a language at GCSE level – the end of secondary schooling examination taken by most 16-year-olds in England, Wales and Northern Ireland - have fallen between 30% and 50%. Scotland has its own exam system but the drop off in language study is comparable.

The UK has a long-standing tradition of teaching French and German at secondary school level, although not always with tremendous success: Brits are not famed for their multilingual skills. However, the popularity of both those languages has plummeted in UK schools. Less than 20 years ago, just 2,500 students were taking a language other than French, German, Spanish or Welsh – which is a mandatory curriculum requirement in Wales. But by 2017, according to numbers acquired by the BBC, that had shot up to 9,400.

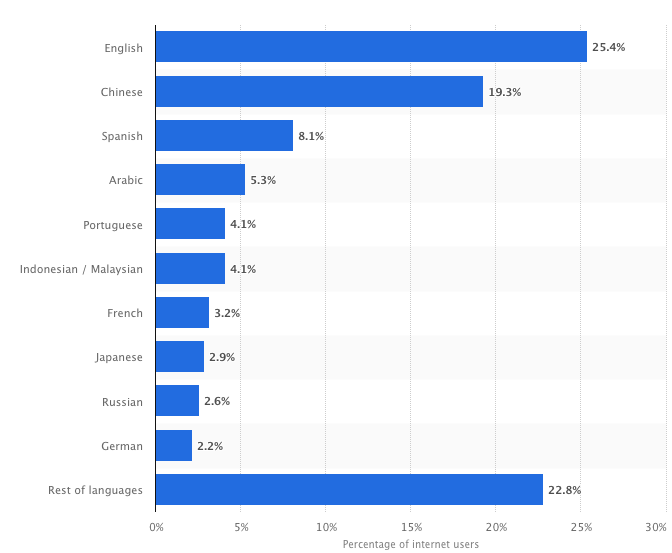

Two languages that are growing in popularity in the UK are Spanish and Chinese, the BBC found. Chinese, of course, is the most widely spoken language in the world. However, in the online sphere it’s a close second to English. Online, English is used by 25.4% of people. For Chinese, it’s 19.3%. Both are way ahead of third-placed Spanish which is used by 8.1% of internet users.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Education .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How universities can use blockchain to transform research

Scott Doughman

March 12, 2024

Empowering women in STEM: How we break barriers from classroom to C-suite

Genesis Elhussein and Julia Hakspiel

March 1, 2024

Why we need education built for peace – especially in times of war

February 28, 2024

These 5 key trends will shape the EdTech market upto 2030

Malvika Bhagwat

February 26, 2024

With Generative AI we can reimagine education — and the sky is the limit

Oguz A. Acar

February 19, 2024

How UNESCO is trying to plug the data gap in global education

February 12, 2024

How to learn a second language: A comprehensive guide

Learning a second language involves understanding how its sounds, words, and grammatical patterns are used to express meaning in different situations. Second language learning is a long journey that has many stages, but can be extremely rewarding: studies have shown that knowing two or more languages can slow cognitive decline . What’s more, knowing a foreign language also looks great on your resume! However, it can take a long time to go from a beginner to an expert language user. The time it takes to become fluent in another language partly depends on which language you choose to learn, as some will be easier than others. But even if you’re learning an easy language, you’ll probably run into problems at some point in the language-learning process. That’s why you should know what to focus on when learning, what factors affect the learning process, and what myths about language learning are floating around out there. At the end of the day, learning a second language is a great way to learn about a new culture, and a fun way to spend your free time. And since these days there are so many tools you can use to learn a second language (like the Mango app !), there’s no reason not to give it a try!

So where should you start? Well, with the Mango Languages Guide to Learning a Second Language, of course! The guide you’re about to read is designed to be a roadmap for your language-learning journey. We’ll talk about what goes into language learning, give you some tips and tricks for how to learn a language quickly, and answer common questions about the language learning process. We’ll also point you toward additional resources that will help you along the way.

You’ve got some work ahead of you, but we promise the view from the other side is worth the climb!

Table of Contents

What are the different parts of a language.

There are two main parts of a language: language structure and language use. The structure of a language includes its vocabulary (words), grammar (rules to put words together), and pronunciation (sounds and ways of putting sounds together). Language use, on the other hand, refers to how you use your knowledge of language structure to understand and express meaning in the real world. Knowing a bit more about these parts will help give you an idea of where to start with language learning!

Speaking is another big part of using a second language. And perfecting your pronunciation is just one part of speaking; you’ll also need to learn to have a conversation! This can be difficult since different cultures might have very different expectations about things like, “how to be polite” and “how to take turns when speaking”. They may also have different ways of using physical behaviors (e.g., gestures, eye contact) to communicate meaning. And of course, to really sound fluent in conversation, you need to learn to use filler words like “um” or “so” or “y’know”.

So as you can see, language is made up of a lot of different parts that need to be applied in the real world. And if this seems a little intimidating, don’t worry! In the next section, we’ll give you some tips to help you learn and practice everything we’ve just mentioned!

What should You Focus on When Learning a Second Language?

When learning a second language, you should focus on studying the structure of the language (vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation) and on figuring out how to use those structures in the real world. Let’s take a look at how you can best approach each of these.

Language Structure

Learning new words is one of the most important things to focus on when learning a second language. Why? Well, studies have consistently shown that learners who know more words are more fluent speakers . A great way to increase your vocabulary size is through reading or listening to something that you find interesting and can mostly understand. This could be a book you find at the library, a magazine you pick off the shelf, or a TV series on a streaming service that catches your eye. In fact, it doesn’t matter what you choose as long as you try to maximize your exposure to second language words! Producing language (speaking, writing, or signing) can also help you increase your vocabulary size because if you want to use words that you don’t know, you might be motivated to look them up. Chatting with native speakers and keeping a diary in your target language are great activities that can promote this behavior. You can also make and study flashcards using pre-made lists of important vocabulary.

Once you learn the basic meaning(s) of a word, you will also need to figure out how that word is used in the real world. This means that you’ll need to learn the different aspects of a word, like how it sounds or is written, what other words it relates to, and how it’s used in context. While you’re likely to pick up on some of this information just by using your second language, you can help yourself learn even faster if you use strategies and study habits that help you organize and remember information about new words. Check out our post, “14 Easy Ways to Improve Your Vocabulary Skills” if you’re interested in learning more!

You’ll also need to focus on grammar to learn a second language. The grammar of a language refers to the rules that speakers use to put words together. Grammar gives us information about how words are related to one another and about how individual words can be changed to express different meanings. Learning grammar is often emphasized in foreign language classrooms, and for good reason: Studies have shown that instruction can improve grammar skills , and that grammar is a key part of becoming a skilled reader, writer, listener, and speaker .

In general, there are 2 main ways to learn second language grammar: implicitly and explicitly. Implicit grammar learning happens when you pick up on a rule without realizing it, typically while you are using your target language (e.g., reading, having a conversation, etc.). Explicit grammar learning, on the other hand, happens when you are aware of the fact that you are learning. This may involve intentionally memorizing a rule and practicing it again and again until you have it down pat. Implicit and explicit learning are both important parts of improving your grammar skills, but for different reasons. If you learn a rule implicitly, you may eventually be able to access and use it automatically. However, this process can take a long time, and may still result in mistakes from time to time. Explicit grammar learning, on the other hand, is quick, effective, and can help you notice how rules work. This could in turn help you be more accurate when using the rule. However, if you exclusively focus on explicit grammar learning, you may have trouble becoming a fluent language user, simply because you may not have enough experience using the rule. Thus, to fully develop your second language grammar skills you’ll need to learn both explicitly and implicitly! You can read more about implicit and explicit learning in our post from our Science Behind Language Learning Series, “ Can I learn a language without trying? ”

Pronunciation

Pronunciation is another key part of language structure to focus on when learning a second language. Improving your pronunciation involves becoming familiar with the phonemes (i.e., individual speech sounds) and phonology (i.e., how sounds should be combined) of your target language. Learning how to pronounce phonemes could be a difficult task, depending on how similar your target language is to your first language . For some languages, you might have to learn entirely new ways of moving your mouth, lips, and tongue.

If you’ve ever tried learning Spanish, for example, you may have found it difficult to make the rolled “double r” sound (called a “trill”) in the words arroz ( " rice " ) and perro ( " dog " ) . For other languages, you might simply need to adapt movements you already have in your first language. For example, the “r” sound in Japanese (called a “flap”) is very similar to how American speakers pronounce the first “t” in the phrase “get out”.

You can learn the phonemes of your target language through explicit study (e.g., using information from the internet or a textbook), or better yet by actually practicing producing them. Some good activities for practicing phonemes include reading aloud and studying the mouths of native speakers .

In addition to learning phonemes, you’ll also need to learn about how they change depending on what sounds come before or after them, or where they are in a word. For example, did you know that there’s a different “t” sound in “top,” “cat,” and “kitten”? (Go ahead, try it!) You’ll also have to focus on other phonological rules like stress (which parts of a word or sentence to emphasize), rhythm (the time between syllables), and intonation (how to properly change the pitch of your speech). Some good activities for practicing the phonological aspects of your pronunciation include shadowing (i.e., listening to and imitating the way someone speaks), transcribing and analyzing speech, and even singing songs.

It may sound surprising, but listening activities are also a great way to improve your pronunciation. Some speech researchers have even suggested that you won’t be able to pronounce new sounds until you are able to perceive them ! We recommend the following listening-for-pronunciation activities:

Talk with native speakers so that you can hear how they pronounce different words and compare your own pronunciation. The Mango voice comparison feature is great for this. It lets you record samples of your own speech and see how they align with that of a native speaker!

Watch TV series or educational YouTube videos in your target language and see if you can pick up on pronunciation patterns.

One thing to keep in mind is that having an accent does not mean that you have bad pronunciation. In fact, in the United States alone, there are at least six different regions with millions of people who speak in different accents. Besides this, second language speech researchers have shown again and again that people can still understand you even if you have an accent! Above all, it’s important to set realistic goals for pronunciation learning. So try to focus first on being understood instead of sounding like a native speaker!

Language Use

Focusing on how language is used is a key aspect of learning a second language. This means learning how to read, write, listen, and speak in that language. Although each of these skills develops differently, you will need to master all four if you want to reach an advanced level of language proficiency. Read on more to find out how you can become a master of language use!

Learning to read in your target language is an important part of becoming a skilled language user. Reading is one of the best ways to increase your exposure to new words and grammar, and is a fun activity to boot. To learn how to read in your second language, you’ll first need to become familiar with the writing system of your target language. This may be easy or difficult, depending on whether this system is similar to the one in your native language. For example, if your native language is English, you would have an easier time learning to read Dutch , whose alphabet and spelling are very similar to English, than learning to read Arabic , which uses an entirely different set of letters and rules for combining them. Luckily, most textbooks offer some information about the writing system of your target language, and there are tons of online resources available.

Once you learn about how your target language is written, you can start working towards becoming a fluent reader. Fluent readers are able to quickly recognize words, connect them with each other, and relate the message they express to what they already know. The first of these three processes is particularly key to focus on. One way to become better at recognizing words is to make word learning a part of your study plan. For example, try using flashcards to memorize the written form of words and set up a regular time to quiz yourself. This can help make sure that you’ll be able to spot words when you see them in context. Another way to build your sight vocabulary is to simply read something in your target language every day. And if you’re just starting out, don’t worry—you can start small and work your way up. Try reading a short passage from a textbook, a news headline, or even just a few text messages. Eventually, you can move on to reading short stories or novels written for native speakers!

There are a number of other steps you can take to accelerate your development as a reader. For instance, you can try reading the same book in two different languages to compare how sentences are translated. Or, you can discuss what you’ve been reading with a friend who shares your language and reading interests. You can find more tips like this in our article on how to improve your reading skills in a second language . Why not have a look?

Learning how to write is another important aspect of mastering language use, even if you only want to have conversations. When you write in your target language, you’re actually practicing stringing words together (i.e., using grammar rules), which can actually help you form sentences in speech . Writing can also help you identify gaps in your ability to express yourself fluently, and lead to language growth. As with reading, you need to learn the writing system of your target language to learn how to write it. If you are learning an entirely new writing system, try practicing writing the letters of the alphabet (or characters) by hand or typing your language on a computer.

Once you’ve learned the writing system of your target language, you can start to write to practice your language skills. The simplest way to practice writing is to pick a topic you like and put your pen to the page (or your fingers to the keyboard!). You could also try keeping a journal, finding a pen pal (websites like InterPals , PenPal World , or Lang-8 are great places to find a pen pal), or starting a blog about your language learning process. Because writing is a slower-paced activity, you can take the time to find the words you want to use to express yourself. And if you can’t find those words, you can use an online dictionary like Reverso to fill in the gaps!

Learning how to edit what you have written is another important part of learning how to write in your target language. Try asking a native-speaking friend to make sure what you’ve written is accurate, or simply use an online spelling and grammar checker . Once you get feedback on your writing, it’s important to both apply it and understand it. Ask yourself, “Why was what I wrote corrected?” and “How can I make sure I remember to write it this way next time?” For more, check out our post on tips, tools, and resources on writing in a foreign language .

You’ll also need to develop your listening skills to use your target language in the real world. But becoming a skilled listener can be a challenge, especially if you are just starting out. You might have trouble picking out words, and feel that what you’re hearing is so fast that it goes in one ear and comes out the other. The best way to overcome these problems is to become familiar with the sounds of your target language so that you can recognize words and phrases. But that’s not all it takes to become a skilled listener. You’ll also need to quickly understand how the words you hear relate to each other and to what has already been said.

There are many activities you can do on your own to develop your listening ability. For instance, listening while reading is a great way to learn the pronunciation of words you can recognize by sight. You can also try listening to your favorite podcast while reading a transcript, or watching your favorite TV series with the subtitles on (in your first language at first, but eventually in your target language!). You may also find it helpful to concentrate on getting the bigger picture of what you’re listening to instead of focusing on understanding each individual word. This way, you can practice filling in what you haven’t understood by using what you have understood. If you are interested in learning more, check out some other techniques you can try to improve your foreign language listening skills .

Learning to speak in a clear and natural way is important to focus on, especially if you want to have conversations in your second language. Fluent speakers are able to apply their knowledge of language structure – so vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation – in their daily lives. This takes time and practice, so you should try to speak in your target language whenever you have the chance. The most straightforward way to access speaking opportunities is to immerse yourself in a country that speaks your target language. But there are plenty of ways to practice speaking in your home country as well. For example, you can grab a coffee with a friend who speaks your target language, or set up regular video chats. Don’t have any friends who speak your target language? No problem! Try setting up a language exchange using a website that helps find people in your area looking for conversation buddies. Having trouble finding anyone to talk with in your target language? You can still practice speaking by talking out loud alone or imitating what you hear while watching your favorite TV series. This can help you get a feel for what kinds of mouth movements you need to speak the language. Be sure to check out our tips on other unique ways to practice speaking in a foreign language .

One good way to accelerate your speaking progress is to practice using memorized phrases (e.g., “Can you please repeat that?”, “Where is the bathroom?) Just open any phrasebook, choose an expression, and say it to yourself over and over again. Then, when you’re out in the real world, try using what you’ve practiced and see how people react. Even if you get it wrong, the feedback you receive could help you know where and how to improve in the future. But since you can’t learn how to speak from a phrasebook alone, you should definitely keep an eye out for any phrases that you hear over and over again in conversation. Make sure you try to memorize these (writing them down helps!) and then experiment with them in your own speech.

If you want to become a really proficient speaker, however, you’ll need to understand when and where it’s appropriate to say certain things. Try observing conversations in different settings (e.g., informal vs. formal) and look out for differences in language use. Ask a native-speaking friend about how to express yourself differently in different settings. Be on the lookout for YouTube channels designed to help explain linguistic and cultural differences! Or better yet, head on over to our post on “ 11 Unique Ways to Practice Speaking a Foreign Language .”

What is the Best Way for Beginners to Learn a Language?

If your goal is to reach advanced proficiency in a second language, you’ll eventually need to master aspects of language structure and language use. But if you’re just getting ready to embark on this journey, where should you start? Well, a good first step is to learn the most common words and phrases in a language, since these are what you’re most likely to run into. To get you started, try downloading a freely available list of common survival vocabulary curated by language researchers, make some flashcards, and practice on a regular schedule. You can also find some children’s books in your target language and start reading as much as you can. Remember: Reading is a great way to learn new words! Apart from vocabulary, you should also start learning the basics of grammar. Find a textbook, take a language course, or better yet, check out the Mango app , which introduces you to the language you need to have authentic conversations in over 70 languages bit-by-bit. Speaking and writing are other great ways to practice grammar, even if you are still just getting your feet wet. Just remember to keep it simple to start with: Try memorizing some basic conversational routines (like greetings and farewells) or writing simple messages to your friends in your target language. And to practice listening, try watching your favorite TV series or movies in your target language with subtitles in your first language.

One last tip if you’re just starting out: Don’t worry too much about making mistakes. Instead, keep your head up and remember that there are opportunities for learning every time you use your target language, including when you make mistakes ! So get out and start studying!

Now that we’ve taken you through some of the best ways for beginners to learn a language, let’s talk about some burning questions learners often have about second languages. In this section, we’ll give you the short answer to each question, and direct you toward some resources that can help you plan your language-learning adventure.

What are the Stages of Learning a Second Language?

In broad terms, second language learning involves three different stages of proficiency: beginner, intermediate, and advanced. Language educators often use frameworks from CEFR and ACTFL to tell learners at different stages apart. These frameworks describe what language users can or cannot do in a language at each stage of achievement. Generally speaking, learners at the beginner stage can understand the basics of a language and communicate using simple words and memorized phrases, but may not be able to use language independently. Learners at the intermediate stage can generally understand and produce enough language for everyday language needs, but may not be able to handle complex topics and situations. Learners at the advanced stage should be able to understand nearly everything that they read or hear, and should be able to discuss complex topics with ease.

It’s important to keep in mind that these are just broad descriptions of the different stages of second language learning. Make sure you check out our article on this topic to read more about the standards used to determine language proficiency !

How Long Does It Take to Learn a Language?

How long it takes to learn a second language depends on a number of different factors, including what language you are learning, what methods you use to learn it, and how you measure language fluency. For the easiest languages (those similar to your native tongue), with intensive study, it takes 24 weeks to reach professional working proficiency . (With Mango languages, it can take as little as 8 hours to go up one ACTFL proficiency step!). Harder languages (e.g., Mandarin for native English speakers) may require between one and two years to reach the same level. Keep in mind that these estimates are based on high-achieving, highly motivated adults who are able to dedicate a lot of time to studying — in other circumstances, language learning can take several years, decades, or even a lifetime. Interested in learning more? Mango’s got you covered! Take a look at our article, “ How Long Does it Take to Learn a Language? ”.

What are the Factors that Affect Language Learning?

There are many factors that affect language learning, including:

Your native language

Your personality

How often you study the language

The environment you are learning in

The learning strategies you use

These factors can affect not only how quickly you can learn a second language, but also how proficient you can become in the long run. Other factors which have been shown to affect language learning include your level of motivation and how good your brain is at processing information. Are you interested in learning more about why these factors can matter for language learning? Wondering how you can get these factors on your side? Check out our article on the factors that influence language learning !

What are the Myths about Learning a Language?

As a language learner, you’ve probably encountered quite a few myths about language learning such as, “it’s always costly to learn a language” and “you need to have a great memory to learn a foreign language.” Once you understand the truth behind many prevalent myths about language learning, you’ll have a better sense of how language learning really works. This will allow you to focus your energy on learning your target language in the most productive way possible. Are you asking yourself what other myths might be out there? Head over to our page on the myths of learning a new language to find out!

What are the Best Sources and Tools to Learn a Language?

There’s no one tool or source of language knowledge that’s going to be perfect for everyone. But let’s talk about some of the most common sources and tools people use to learn a language. We’ll talk a little about the pros and cons of each method, so you can get a better idea of what might work best for you.

Can You Learn a Language from a Course?

You can definitely learn a language from a course. Are you a person who needs a little extra motivation to keep to regular practice schedules? Do you learn best in a social setting? Then a language course might be the right choice for you.

A language course can take different forms:

An in-person group course, of the sort they offer in high schools, libraries, or community centers.

Private, in-person tutoring, where you hire a person to sit with you and practice.

A synchronous online course, where you meet with a teacher or private tutor over video chat.

An asynchronous online course, where a teacher assigns and grades work that you complete on your own schedule.

There are many benefits to studying a language with a course. For example:

With most formal courses you’ll have the hands-on attention of a teacher who can help you organize your learning, model correct language use, and give you feedback.

Language courses are good for people who need something to give them a little external motivation to study. It’s easier to remember to spend an hour practicing your vocabulary when you’ve got an exam next week!

Courses are also a good way to connect with other people during the language learning process. Some people learn better when they’re doing something social!

Some drawbacks to language courses are:

They usually cost money. The cost can vary depending on the type of course you take. If you’re taking a group class at your local library, the price might be quite affordable or even free at the beginner level, but enrolling in university classes or hiring a private tutor might be more expensive.

Depending on the type of course you take, you might have just a few hours of contact with your target language per week. For example, most university language courses meet for about 3 hours per week! That means that unless you’re taking an intensive (high-speed) course, you’ll still have to put in some time practicing at home!

Here are some tips to keep in mind if you are thinking about signing up for a language learning course:

If you can afford it, skip the course and go with private tutoring or live private instruction. The individualized feedback you receive can really help your learning progress.

If you’re looking for cheaper options, many libraries and community centers can connect you with reduced-price language courses, especially if you’re learning one of the more commonly-studied languages in your area.

If you’re having trouble fitting a regular language class into your schedule, an asynchronous class can be a good way to get feedback on your progress and save you some planning effort. It might not get you as much speaking and listening practice, but it can give you some accountability and a chance to receive feedback, so you don’t keep practicing something incorrectly.

Can You Learn a Language Online?

Yes, you can learn a language online. There are lots of resources online that can help you learn a language on the internet. It is very possible to become an excellent speaker of a new language without ever needing to leave the house. We’ve already mentioned online language courses above. Some other helpful resources you can find online include:

Free written articles on grammar and vocabulary

Dictionaries

Video lessons (try searching YouTube!)

Other forms of media in your target language (movies, social media, radio, books, music, podcasts, newspapers…)

Some language learning apps and online programs are free or have free versions to get you started! Does your library provide access to Mango?

Here’s one quick tip for finding the best online language learning resources: Rather than searching for broad terms like “Learn French” try searching for specific resources like “French-English Dictionary,” “Practice French pronunciation,” or “Forming the past tense in French.”

Can You Learn a Language from an App?

An app can be a great way to learn a language. Like other learning methods, apps have advantages and disadvantages. Some advantages of learning a language through an app include:

Apps are one of the best ways to keep yourself practicing your language daily. They usually come with daily goals and study reminders, and can make learning a language feel like a fun game.

Apps are especially useful in teaching you vocabulary and helping you practice new phrases and sentence structures.

Apps can provide you with good exposure to the spoken form of words — but make sure you find an app that using authentic recordings from actual speakers of the language you are learning.

Apps can help you plan your language learning process. An app will introduce you gradually to new skills, vocabulary, and even cultural knowledge!

Apps are often free or inexpensive.

Apps let you learn on a schedule that works best for you. If you have lots of downtime while you work the night shift at a hotel desk, you can study then!

Some disadvantages of learning a language through an app include:

Most apps don’t provide authentic speaking and writing practice. Apps can help you with speaking and writing to a certain extent, but they mostly focus on teaching words and phrases. If you want to practice speaking off-the-cuff you’ll have to supplement your learning with real practice.

Apps aren’t particularly good at correcting your pronunciation. They can model pronunciation and sometimes detect whether you’ve said something entirely wrong, but they won’t be as good of a judge of your pronunciation as a native speaker.

Apps can’t give you rich, customized feedback like a teacher can.

Apps can sometimes fool you into thinking you’re more fluent than you are! You can get to a high level on an app and have very good theoretical knowledge of a language, only to realize that your ability to actually use the language is lagging behind.

Even though an app can be a great replacement for a language textbook, the best way to learn with an app is to complement it with real-life practice.

Can You Learn a Language on Your Own?

The short answer to this question is, yes, you can definitely learn a language on your own! The long answer is that some skills are easy to learn on your own, while others are more easily learned from a teacher or a native speaker. Apps and online learning tools are great for learning on your own because they can help organize your learning. You can also work through a textbook or a workbook on your own to work on your language skills. And of course, you can learn a language on your own by consuming written or spoken media in your target language.

The one thing that’s hard to do on your own is practicing speaking, or having conversations. For this, you’ll need to find someone to talk to, be it a classmate in a language course or a live tutor. Nevertheless, there are some things you can do on your own that will help you practice speaking naturally:

Record yourself giving a speech in your target language and play it back.

Put on a play with yourself playing both parts, and play it back.

Narrate what you’re doing as you’re cooking dinner as if you’re on a cooking show. Record yourself and play it back.

When you play back your recordings, pay attention to any sounds, words, or grammatical structures that interrupt the flow of your speech. These techniques will help you smooth out your speech for when you’re ready to use your language out in the real world!

What are the Best Practices of Learning a Language?

There are a number of best practices you can follow to optimize your language learning experience. Some of the best practices we recommend include:

Practice a little bit every day. Though you can learn a lot through binge-studying, the best way to keep it in your memory and to help keep that knowledge fresh over time is to spread out your studying and practice!

Practice all of the practical skills you want to have. Just because you have a good vocabulary doesn’t mean your grammar is keeping up. Just because you’re good at reading doesn’t mean you’ll be great at speaking. Just because you’re good at talking about what you did yesterday doesn’t mean you’ll be great at giving a formal presentation for work. You need to practice the skills you want to build! If you don’t sound perfect on your first try, you’re in good company! Keep practicing!

Expose yourself to real-world use of the language you’re learning through immersion. How people use a language “in the wild” in their own country is quite different from how it’s used in a classroom.

Get help from advanced or native speakers when you can! Highly proficient speakers will be able to immediately hear or see your mistakes and can provide you with feedback.

Learning a language is more than just reading a book about the language and memorizing some facts! It’s going to take some practice and you’ll probably have to push through some embarrassment in the early stages, but it’s worth it in the end. Interested in learning more about the best practices for learning new languages in general? Have a look at our articles on the most effective language learning strategies!

What are the Most Popular Languages to Learn?

English is the by far most popular language to learn in the world. More than 2 billion people speak English worldwide , and less than a third of those are native speakers. This means that over a billion people speak English as a second (or third, fourth, or fifth) language!

The next most common languages people learn (with the number of second language speakers, according to Ethnologue ) are:

Modern Standard Arabic (274 million)

Hindi (258 million)

Mandarin Chinese (199 million)

French (194 million)

Urdu (161 million)

If we’re just talking about what people from the United States tend to learn, though, the list of most-learned languages doesn’t quite look the same. In the United States, the languages people tend to learn (with the number of college enrollments in parentheses) are:

Spanish (712,000)

French (176,000)

American Sign Language (107,000)

German (80,000)

Italian (57,000)

That’s a pretty big difference! People in different parts of the world have different reasons for choosing to study different languages. Want to learn more about how to choose the language you want to study? Check out our article on the best foreign languages to learn .

What are the Hardest Languages to Learn?

The hardest languages to learn are those which are very different from your native language. A language can be harder to learn if it contains unfamiliar vocabulary, grammar rules, pronunciation, and/or writing systems. For example, native English speakers might have difficulty learning:

There are also languages that could be very hard because they belong to an entirely different language family. Some languages that are very hard for English speakers to learn include:

Although these languages can be a bit trickier to learn, they could also expand your language learning skills in ways that will help you learn other languages more quickly in the future! What’s more, because they are more difficult, they may also be in higher demand (think: jobs in the US government). Thus, studying these languages could be a benefit to your future career!

If you’re interested in learning more about what makes a language hard to learn or which languages are hardest for English speakers, check out our article, “ What are the Hardest Languages to Learn? ”

So there you have it! We hope that this guide has been helpful for your exciting journey towards language fluency. And we hope that you make Mango a part of your language learning experience. Be sure to check out the pages we’ve linked in this article if you are curious to learn more about a particular topic. Thanks and so long for now! Au revoir! Chào nhé! Aloha!

Adams R., Nuevo, A. M., & Egi, T. (2011). Explicit and implicit feedback, modified output, and SLA: Does explicit and implicit feedback promote learning and learner-learner interactions? The Modern Language Journal , 95, 42–63.

De Jong, N., Steinel, M., Florijn, A., Schoonen, R., & Hulstijn, J. (2012). FACETS OF SPEAKING PROFICIENCY. Studies in Second Language Acquisition , 34(1), 5-34.

Derwing, T., & Munro, M. (2009). Putting accent in its place: Rethinking obstacles to communication. Language Teaching , 42(4), 476-490.

Flege, J. (2003). Assessing constraints on second-language segmental production and perception. In N. Schiller & A. Meyer (Ed.), Phonetics and Phonology in Language Comprehension and Production: Differences and Similarities (pp. 319-358). De Gruyter Mouton.

Nation, P., & Yamamoto, A. (2012). Applying the four strands to language learning. International Journal of Innovation in English Language Teaching , 1(2), 167-181.

Norris, J. M., & Ortega, L. (2000). Effectiveness of L2 instruction: a research synthesis and quantitative meta-analysis. Language Learning , 50(3), 417–528.

Weissberg, R. (2006). Connecting speaking & writing in second language writing instruction. University of Michigan Press .

To embark on your next language adventure, join Mango on social!

Ready to take the next step.

The Mango Languages learning platform is designed to get you speaking like a local quickly and easily.

We value your privacy.

We use cookies to enhance your browsing experience and analyze our traffic. By clicking "Accept All", you consent to our use of cookies. Cookie Policy.

Why You Should Learn a Second Language and Gain New Skills

May 12, 2020

In The News

One of the most practical ways to make use of your spare time nowadays is to start learning a new skill.

People who always succeed are those who are keen to learn something new every day - be it learning about other cultures or learning a second language.

At Middlebury Language Schools, we are strong advocates for the importance of mastering a second language. Both personally and professionally, being bilingual can bring you several advantages.

In this article, we will break down some of the benefits of learning a second language and why this skill is one of the most overlooked skills in the world.

LEARN A NEW LANGUAGE !

Why is it important to know more than one language

We live in a multilingual world, where connections are now more important than ever. The world is becoming increasingly globalized and knowing a second language can always give you an unfair advantage.

There are tangible benefits to being bilingual:

- It can help you in your career;

- It can improve your memory and brain functions;

- It can help increase your understanding of the languages you already speak.

A second language can drastically change your career. Living in an interconnected world means that more and more jobs are advertising positions where knowing more than one language is essential.

As more companies trade internationally and create relationships with other countries, employees are often asked to travel for work, enhance these relationships, or be relocated abroad.

Besides having more chances of landing a good job or advancing in your career, learning a second language can also give you an insight into other cultures. You will be more prepared and confident to travel the world and explore other people’s ways of living.

Lack of integration is a real problem for most countries. More often than not, this is due to the language barrier. People outside of their home countries end up being isolated, hanging out only with people from similar communities where their language is spoken.

Learning a second language opens up the opportunity for being part of a community with a different culture, and learning more about the world around us.

Did you know that being bilingual can also help you master your own language? For example, learning a new language with similar roots can help you learn other languages as well. Take Spanish , Italian , and French from one summer to the next!

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR LANGUAGE PROGRAMS !

What are the benefits of learning a second language

As mentioned before, learning a new language is a wonderful benefit in a globalized world. Let’s have a look at some of the benefits of learning a second language.

1. It improves your memory

The more you use your brain to learn new skills, the more your brain’s functions work. Learning a new language pushes your brain to get familiar with new grammar and vocabulary rules. It allows you to train your memory to remember new words, make connections between them, and use them in contextual situations.

2. Enhances your ability to multitask

Time management and multitasking are two skills that will always help you. Multilingual people have the ability to switch between languages. Their ability to think in different languages and be able to communicate in more than one language helps with multitasking.

3. Improves your performance in other academic areas

Fully immersing yourself in a language learning environment means not only learning the basics of that language. It means learning how to communicate in another language with your peers or participating in extracurricular activities in that specific language.

What languages are the most useful to learn? Middlebury Language Schools recommends 3 of our 13 languages

Since 1915, Middlebury Language Schools has been one of the nation’s preeminent language learning programs.

Whether you’re a beginning language learner or working toward an advanced degree, our time-tested programs offer a range of options and opportunities.

Taking the Language Pledge at Middlebury Language Schools means committing to communicate only in the language of your choice for the duration of the program. You will live, play, and learn in a 24/7 environment.

We offer a wide range of languages you can choose from. Here are just a few of the languages we offer.

Due to many geopolitical reasons, the Russian language is not very closely related to English. It is a very challenging language to learn, with complex grammar and syntax rules. However, it is an extremely culturally and politically relevant language.

At the School of Russian , you can experience the most effective method for rapid language acquisition. An immersion environment is a promise that you will read, write, speak, and listen only in Russian throughout the duration of the program. Some of the benefits of learning Russian at Middlebury Language Schools include interpreting poetry, learning about the culture, and mastering the Russian etiquette.

LEARN RUSSIAN !

Arabic has been one of our most popular languages. It is a high demand language because it can get you ahead in a government career, but also give you endless opportunities in business and international relations.

Arabic is spoken by more than 300 million people and is one of the top 5 most spoken languages in the world. Learning Arabic as a second language can help you learn about the Arabic culture and religion. It not only gives you opportunities to expand your connections, but also offers great travel opportunities.

A summer at the Arabic School will help you experience the immersive environment on campus. At Middlebury Language Schools, the focus is on Modern Standard Arabic, with optional Arabic language classes in dialects such as Egyptian, Syrian and Moroccan.

Check out our Arabic graduate programs and Arabic 8-week immersion program for more information.

LEARN ARABIC !

A lot of people agree that Spanish is one of the easiest languages to learn, due to the fact that you read words as they are written. Spanish is the most spoken language in the world after English and is used by more than 400 million people.

Spanish skills can be a strong asset for communicating and creating relationships not only in Spain, but also in Latin America.

At the Middlebury School of Spanish , you can engage your mind with topics of interest, from Spanish history to arts and cooking.

Ready to learn Spanish? Check out Middlebury Language Schools’ 7-week immersion program or the graduate programs .

LEARN SPANISH !

Reminders on why you should learn a second language now

We have broken down the benefits of learning a second language and becoming bilingual in a highly globalized world.

The truth is, learning new skills every day enhances all aspects of your life. By learning new skills, you can increase your career opportunities, find out more about the world around you, and be a better person overall.

We highly encourage you to start learning a new language as early in your life as possible. However, you are never too old to learn! The world moves fast, and we must keep up with the changes - by developing new skills, learning more about ourselves, and also, learning a new language!

ENROLL NOW !

Learning Languages

Learning a language is a complex, time-intensive task that requires dedication, persistence, and hard work. If you’re reading this, then you probably already know that.

What you might not know is that there are strategies that can help you study more effectively, so that you make the most of your time and energy. This handout first explains some of the key principles that guide effective language learning, and then describes activities that can help you put these principles into practice. Use these tools to create a strategic study plan that helps your language skills grow.

Key principles of language learning

The Basics:

First, let’s talk about the basics. Research in this area (called “second language acquisition” in academia) suggests that there are three key elements to learning a new language.

- The first is comprehensible input , which is a fancy way of saying being exposed to (hearing or reading) something in the new language and learning to understand it.

- Comprehensible output is the second element, and unsurprisingly it means learning to produce (speak or write) something in the new language.

- The third element is review or feedback , which basically means identifying errors and making changes in response. [1]

Fancy terms aside, these are actually pretty straightforward ideas.

These three elements are the building blocks of your language practice, and an effective study plan will maximize all three. The more you listen and read (input), the more you speak and write (output), the more you go back over what you’ve done and learn from your errors (review & feedback), the more your language skills will grow.

DO : Create a study plan that maximizes the three dimensions of language learning: understanding (input), producing (output), and identifying and correcting errors (review/feedback).

Seek balance

Learning a new language involves listening, speaking, reading, writing, sometimes even a new alphabet and writing format. If you focus exclusively on just one activity, the others fall behind.

This is actually a common pitfall for language learners. For example, it’s easy to focus on reading comprehension when studying, in part because written language is often readily accessible—for one thing, you have a whole textbook full of it. This is also true of the three key elements: it’s comparatively easy to find input sources (like your textbook) and practice understanding them. But neglecting the other two key principles (output and feedback/review) can slow down language growth.

Instead, what you need is a balanced study plan: a mix of study activities that target both spoken and written language, and gives attention to all three key principles.

DO : Focus on balance: practice both spoken and written language, and make sure to include all of the three key principles—input, output, and feedback/review.

Errors are important

Sometimes, the biggest challenge to language learning is overcoming our own fears: fear of making a mistake, of saying the wrong thing, of embarrassing yourself, of not being able to find the right word, and so on. This is all perfectly rational: anyone learning a language is going to make mistakes, and sometimes those mistakes will be very public.

The thing is, you NEED to make those mistakes. One of the key principles of language learning is all about making errors and then learning from them: this is what review & feedback means. Plus, if you’re not willing to make errors, then the amount of language you produce (your output) goes way down. In other words, being afraid of making a mistake negatively affects two of the three key principles of language learning!

So what do you do? In part, you may need to push yourself to get comfortable with making errors . However, you should also look for ways to get low-stakes practice : create situations in which you feel more comfortable trying out your new language and making those inevitable mistakes.

For example, consider finding a study partner who is at your level of language skill. This is often more comfortable than practicing with an advanced student or a native speaker, and they’re usually easier to find—you’ve got a whole class full of potential partners!

DO : Learn to appreciate mistakes, and push yourself to become more comfortable with making errors.

DO : Create opportunities for ‘low-stakes’ practice, where you’ll feel comfortable practicing and making mistakes.

Spread it out

Studying a new language involves learning a LOT of material, so you’ll want to use your study time as effectively as possible. According to research in educational and cognitive psychology, one of the most effective learning strategies is distributed practice . This concept has two main components: spacing, which is breaking study time up into multiple small sessions, and separation, which means spreading those sessions out over time. [2]

For example, let’s imagine you have a list of vocabulary words to learn. Today is Sunday, and the vocab quiz is on Friday. If you can only spend a total of 30 minutes studying this vocab, which study plan will be the most effective?

(A) Study for 30 minutes on Thursday. (B) Study for 10 minutes at a time on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday. (C) Study for 10 minutes at a time on Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday. (D) Study for 30 minutes on Sunday.

If you look at the total time spent studying, all four options are exactly the same. But research suggests that option C is the most effective way to manage your time: instead of studying the vocabulary all at once, you’ve spread out the time into several shorter sessions, and you’ve also increased the amount of time between study sessions. (And yes, this is also why “cramming” isn’t a good study plan!)

DO : Break up your study time into shorter chunks and spread those sessions out over time.

Bump up your memory

Memory is a critical part of any kind of studying, and effective memorization is strongly correlated with success in foreign language classes. [3] But if you’re not “good at” memorizing things, don’t despair! Although people often think of memory as a fixed quality, it’s actually a skill that you can improve through deliberate practice.

There’s a considerable amount of research on how memory works, as well as a wide range of strategies for improving memory. For example, scientific experiments show that our short-term memory can only hold about 7 pieces of new information at once. So if you’re working on a long list of new vocabulary words, start by breaking it up into smaller chunks, and study one shorter section at a time. Additionally, research also suggests that recall-based study methods are most effective. This means that actively trying to recall information is more effective than simply reviewing information; essentially, self-testing will help you more than re-reading your notes will. [4]

The best way to start working on your memory is to build on the techniques that you already know work for you. For example, if associating a word with a picture is effective for you, then you should incorporate images into your vocabulary practice. However, if you’re not sure where to start, here’s a “beginner” formula for memorizing a new word: use the word at least five times the first day that you learn it, then multiple times over the week, at least once every day.

If you’re interested in more tips for improving your memory, check out our resource on memorization strategies .

In addition to figuring out which memorization techniques work best for you, it’s also important to actively protect your memory. For example, experiencing a strong emotion has been shown to sharply decrease the ability to memorize unrelated content. (So if you’ve just watched a horror movie, it’s probably not a great time for vocabulary review!)

To get the most out of your study time, here’s a list of common “memory killers” to avoid:

Stress and anxiety : Just like other strong emotions, stress and anxiety drastically reduce your ability to make new memories and recall information.

Information overload : Studying for hours at a time might seem like a great idea, but it’s actually a really ineffective use of time. In fact, taking a short break every 30 minutes helps improve focus, and after 2 hours you should consider switching topics.

Fatigue : The more tired you are, the less effective your memory is. Chronic sleep deprivation is particularly detrimental, so those late-night study sessions might actually do more harm than good!

Multitasking : As you may have noticed, all of these “memory killers” are also things that disrupt focus. Multi-tasking is probably the most common source of distraction. In fact, here’s a great rule of thumb for protecting your memory: if you’re not supposed to do it while driving, then you shouldn’t do it while studying. (Yes, that means drinking, texting, and watching Netflix “in the background” are all NOs.)

DO : Increase memorization by breaking information into small chunks and studying the chunks one at a time, and by using recall-based strategies like self-testing.

DO : Focus on protecting and improving your memorization skills, and build the memory techniques that work best for you into your study plan.

Vocab is king

Want to know a secret? Vocabulary is more important than grammar. DISCLAIMER: This does NOT mean that grammar is unimportant. Without grammar, you won’t know how to use your vocabulary, since grammar tells you how to combine words into sentences. And obviously, if you’re in a foreign language class, you’re going to need to study ALL the material to do well, and that will definitely include grammar. The more vocabulary you know, the more quickly you can grow your language skills. The reason is simple: understanding more words directly translates into more input, producing more words means more output, and more output means more opportunity for feedback. Additionally, when you’re interacting with native speakers, vocabulary is more beneficial to communication than grammar is. Being able to produce words will help get your meaning across, even if what you say is not perfectly grammatical. [5]

Of course, in order to become fully fluent in your new language, eventually you will need strong grammar skills. But once again, this is something that having a strong, well-developed vocabulary will help with. Since grammar dictates relationships between words and phrases, understanding those smaller components (aka vocabulary) will help improve your understanding of how those grammatical relationships work.

DO : Design a study plan that emphasizes vocabulary.

Now that we’ve talked about the general principles that you should incorporate in your language study, let’s focus on activities: practical suggestions to help you find new ways to grow your language skills!

Find real-life sources

Since one of the main 3 components of language learning is input, look for ways to expose yourself to as much of the language you’re learning as possible. But this doesn’t mean reading more textbooks (unless your textbook is a fascinating read that you’re excited about). Instead, look for “authentic” examples of the language, things you’ll actually enjoy and look forward to practicing with, even if you don’t understand every word!

Here are some examples to get you started:

Newspaper articles, magazines, & blogs : Many of these are freely available online, and once you’ve tried reading them a few times, it’s easy to translate the key parts to check your understanding. Look for a topic you’re already interested in and follow it with a news reader app!

Books : Children’s picture books and books you’ve read before in your native language are easy options for intermediate/advanced beginners. The library often has great options available for free!

TV shows and movies : Try watching them without subtitles the first time, starting in ~15 minute segments. Another great option is to watch first without any subtitles, then with subtitles in the language you’re learning, and then finally with subtitles in your native language if you need them. Soap operas are also great options (especially if you like lots of drama!), since the plot lines are often explained multiple times.

Songs : Music, especially popular songs, can be especially well suited to language practice, since you’re likely to memorize the ones you enjoy. Ask a teacher or native speaker for recommendations if you’re struggling to find good examples. Children’s songs can also be fun practice tools.

Podcasts and audio books : There are a lot of options for all sorts of languages, and as a bonus you’ll often get exposure to local news and cultural topics. To get you started, we recommend this site , which has a great list of podcasts for many different languages.

Also, consider tweaking some of your media settings to “bump up” your casual language exposure. For example, changing your Facebook and LinkedIn location and language preferences will force you to interact with the language you’re learning, even when you’re (mostly) wasting time.

Improve the effectiveness of this activity by using the following suggestions!

Slow it down : If you’re listening to a podcast or audio book, try slowing down the speed just a bit: 0.75x is a common option, and the slowed-down audio still doesn’t sound too strange. Also, make sure to take breaks frequently to help you process what you’ve just heard.

Combine your senses : In many cases, you can combine types of input to help create a more learning environment: reading and listening to a text at the same time can help you improve your comprehension. For example, for TV shows and movies, turn on subtitles in the same language. Other options include:

- Radio news stories often have both audio and transcripts available online, especially for pieces that are a few days old.

- Amazon’s Kindle offers an “ immersive reading ” option that syncs audio books with text.

- TED talks come in many different languages, and often include an interactive transcript .

- If you’re an ESL student, the ESL Bits website has some great resources that link reading and listening, and it also has adjustable audio speeds!

Get hooked : To make this strategy as effective as possible, find a source that you really enjoy, and commit to experiencing it only in the language you’re learning. Having a go-to program that you love will help keep you motivated. For example, if you love podcast/radio story programs like “Radiolab” and are learning Spanish, check out “ Radio Ambulante .”

Hold shadow conversations

A key part of learning a new language involves training your ear. Unlike written language, spoken language doesn’t have the same context clues that help you decipher and separate out words. Plus, in addition to using slang and idioms, native speakers tend to “smoosh” words together, which is even more confusing for language learners! [6] In part, this is why listening to real-life sources can be so helpful (see the previous activity).

However, even beginning language learners can benefit from something called conversational shadowing. Basically, this means repeating a conversation word-for-word, even when you don’t know what all of the words mean. This helps you get used to the rhythm and patterns of the language, as well as learn to identify individual words and phrases from longer chunks of spoken language. Another great strategy involves holding practice conversations, where you create imaginary conversations and rehearse them multiple times.

Both of these strategies are great ways to help you learn and retain new vocabulary, and they also increase your language output in a low-stakes practice setting!

Example : If you’ve got a homework exercise that involves reviewing an audio or video clip, take a few extra steps to get the most benefit:

- After you’ve listened to the clip once, shadow the conversation in short sections (think ~20-30 seconds). Focus on reproducing the words as accurately as possible, paying close attention to rhythm, intonation, and pacing.

- Once you can accurately shadow the entire clip, then focus on understanding the meaning of the material, and answer any homework questions related to the clip.

- Now, use the same vocabulary to create a new conversation: think of what you would want to say in a real-life situation like this one, and practice it until you can respond confidently to any side of the exchange.

Become a collector

Since expanding your vocabulary is so important, identifying new words is a big priority. This is especially true when you’re in an immersion environment (studying abroad, etc), but it’s also something that you can do on a regular basis even when you’re at home.

Basically, you need to collect words: any time you encounter a new word, you want to capture it by recording it in some way. The easiest way to do this is in a small pocket notebook, but you could also put a note in your phone, send a text or email to yourself, or even record yourself saying it. The key point is to capture the word as quickly and easily as possible. Also, don’t worry too much about spelling or definitions in the moment: you’ll deal with those later.

Whatever your recording system is (notebook, phone, voice memo, etc), it’s only the first part of the collection process. Next, you’ll need to review each of the words you’ve recorded. This is something you’ll do on a regular basis, so that you can actually use the words you’ve recorded. Depending on how many new words you’re collecting, it might be every day, every few days, or once a week. This is the time when you find the correct spelling, write down the definition, maybe find an example, and so on.

To make this process as effective as possible, you also want to have some sort of system that helps you record and organize your word collection. If you like paper-based methods, then flashcards can be easily organized in index card boxes, though you might want to include some alphabetical divider tabs to help yourself stay organized. However, digital tools are particularly helpful with this kind of information, and there are tons of apps that can help you organize a large vocabulary collection. But you don’t need a fancy app or program: a simple spreadsheet also works great for most cases.

Finally, you also want to make sure to use your word collection! Not only do you need to learn new words once you add them, you’ll also need regular review of old words to maintain your vocabulary. This is another place where digital tools shine, since it’s easy to access the entire collection at any time, making it easier to study and review on a regular basis. In any case, make sure that you incorporate review along with learning new words.

The 4 basic steps of word collection

- Capture new words. Listen for them in class, seek them out in conversations, find them in your “authentic sources,” etc. Record them in the moment, without worrying too much about spelling and definitions.

- Review your new words. Establish a routine so that you regularly “empty out” your recording tool and add the new words to your collection.

- Record and organize your collection. Create an organized system for your collection; common tools include digital flashcard apps, spreadsheets, and traditional index cards.

- Use your words! Make sure you’re learning new additions and also periodically reviewing older words.