Research Aims, Objectives & Questions

The “Golden Thread” Explained Simply (+ Examples)

By: David Phair (PhD) and Alexandra Shaeffer (PhD) | June 2022

The research aims , objectives and research questions (collectively called the “golden thread”) are arguably the most important thing you need to get right when you’re crafting a research proposal , dissertation or thesis . We receive questions almost every day about this “holy trinity” of research and there’s certainly a lot of confusion out there, so we’ve crafted this post to help you navigate your way through the fog.

Overview: The Golden Thread

- What is the golden thread

- What are research aims ( examples )

- What are research objectives ( examples )

- What are research questions ( examples )

- The importance of alignment in the golden thread

What is the “golden thread”?

The golden thread simply refers to the collective research aims , research objectives , and research questions for any given project (i.e., a dissertation, thesis, or research paper ). These three elements are bundled together because it’s extremely important that they align with each other, and that the entire research project aligns with them.

Importantly, the golden thread needs to weave its way through the entirety of any research project , from start to end. In other words, it needs to be very clearly defined right at the beginning of the project (the topic ideation and proposal stage) and it needs to inform almost every decision throughout the rest of the project. For example, your research design and methodology will be heavily influenced by the golden thread (we’ll explain this in more detail later), as well as your literature review.

The research aims, objectives and research questions (the golden thread) define the focus and scope ( the delimitations ) of your research project. In other words, they help ringfence your dissertation or thesis to a relatively narrow domain, so that you can “go deep” and really dig into a specific problem or opportunity. They also help keep you on track , as they act as a litmus test for relevance. In other words, if you’re ever unsure whether to include something in your document, simply ask yourself the question, “does this contribute toward my research aims, objectives or questions?”. If it doesn’t, chances are you can drop it.

Alright, enough of the fluffy, conceptual stuff. Let’s get down to business and look at what exactly the research aims, objectives and questions are and outline a few examples to bring these concepts to life.

Research Aims: What are they?

Simply put, the research aim(s) is a statement that reflects the broad overarching goal (s) of the research project. Research aims are fairly high-level (low resolution) as they outline the general direction of the research and what it’s trying to achieve .

Research Aims: Examples

True to the name, research aims usually start with the wording “this research aims to…”, “this research seeks to…”, and so on. For example:

“This research aims to explore employee experiences of digital transformation in retail HR.” “This study sets out to assess the interaction between student support and self-care on well-being in engineering graduate students”

As you can see, these research aims provide a high-level description of what the study is about and what it seeks to achieve. They’re not hyper-specific or action-oriented, but they’re clear about what the study’s focus is and what is being investigated.

Need a helping hand?

Research Objectives: What are they?

The research objectives take the research aims and make them more practical and actionable . In other words, the research objectives showcase the steps that the researcher will take to achieve the research aims.

The research objectives need to be far more specific (higher resolution) and actionable than the research aims. In fact, it’s always a good idea to craft your research objectives using the “SMART” criteria. In other words, they should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound”.

Research Objectives: Examples

Let’s look at two examples of research objectives. We’ll stick with the topic and research aims we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic:

To observe the retail HR employees throughout the digital transformation. To assess employee perceptions of digital transformation in retail HR. To identify the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR.

And for the student wellness topic:

To determine whether student self-care predicts the well-being score of engineering graduate students. To determine whether student support predicts the well-being score of engineering students. To assess the interaction between student self-care and student support when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students.

As you can see, these research objectives clearly align with the previously mentioned research aims and effectively translate the low-resolution aims into (comparatively) higher-resolution objectives and action points . They give the research project a clear focus and present something that resembles a research-based “to-do” list.

Research Questions: What are they?

Finally, we arrive at the all-important research questions. The research questions are, as the name suggests, the key questions that your study will seek to answer . Simply put, they are the core purpose of your dissertation, thesis, or research project. You’ll present them at the beginning of your document (either in the introduction chapter or literature review chapter) and you’ll answer them at the end of your document (typically in the discussion and conclusion chapters).

The research questions will be the driving force throughout the research process. For example, in the literature review chapter, you’ll assess the relevance of any given resource based on whether it helps you move towards answering your research questions. Similarly, your methodology and research design will be heavily influenced by the nature of your research questions. For instance, research questions that are exploratory in nature will usually make use of a qualitative approach, whereas questions that relate to measurement or relationship testing will make use of a quantitative approach.

Let’s look at some examples of research questions to make this more tangible.

Research Questions: Examples

Again, we’ll stick with the research aims and research objectives we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic (which would be qualitative in nature):

How do employees perceive digital transformation in retail HR? What are the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR?

And for the student wellness topic (which would be quantitative in nature):

Does student self-care predict the well-being scores of engineering graduate students? Does student support predict the well-being scores of engineering students? Do student self-care and student support interact when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students?

You’ll probably notice that there’s quite a formulaic approach to this. In other words, the research questions are basically the research objectives “converted” into question format. While that is true most of the time, it’s not always the case. For example, the first research objective for the digital transformation topic was more or less a step on the path toward the other objectives, and as such, it didn’t warrant its own research question.

So, don’t rush your research questions and sloppily reword your objectives as questions. Carefully think about what exactly you’re trying to achieve (i.e. your research aim) and the objectives you’ve set out, then craft a set of well-aligned research questions . Also, keep in mind that this can be a somewhat iterative process , where you go back and tweak research objectives and aims to ensure tight alignment throughout the golden thread.

The importance of strong alignment

Alignment is the keyword here and we have to stress its importance . Simply put, you need to make sure that there is a very tight alignment between all three pieces of the golden thread. If your research aims and research questions don’t align, for example, your project will be pulling in different directions and will lack focus . This is a common problem students face and can cause many headaches (and tears), so be warned.

Take the time to carefully craft your research aims, objectives and research questions before you run off down the research path. Ideally, get your research supervisor/advisor to review and comment on your golden thread before you invest significant time into your project, and certainly before you start collecting data .

Recap: The golden thread

In this post, we unpacked the golden thread of research, consisting of the research aims , research objectives and research questions . You can jump back to any section using the links below.

As always, feel free to leave a comment below – we always love to hear from you. Also, if you’re interested in 1-on-1 support, take a look at our private coaching service here.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

39 Comments

Thank you very much for your great effort put. As an Undergraduate taking Demographic Research & Methodology, I’ve been trying so hard to understand clearly what is a Research Question, Research Aim and the Objectives in a research and the relationship between them etc. But as for now I’m thankful that you’ve solved my problem.

Well appreciated. This has helped me greatly in doing my dissertation.

An so delighted with this wonderful information thank you a lot.

so impressive i have benefited a lot looking forward to learn more on research.

I am very happy to have carefully gone through this well researched article.

Infact,I used to be phobia about anything research, because of my poor understanding of the concepts.

Now,I get to know that my research question is the same as my research objective(s) rephrased in question format.

I please I would need a follow up on the subject,as I intends to join the team of researchers. Thanks once again.

Thanks so much. This was really helpful.

I know you pepole have tried to break things into more understandable and easy format. And God bless you. Keep it up

i found this document so useful towards my study in research methods. thanks so much.

This is my 2nd read topic in your course and I should commend the simplified explanations of each part. I’m beginning to understand and absorb the use of each part of a dissertation/thesis. I’ll keep on reading your free course and might be able to avail the training course! Kudos!

Thank you! Better put that my lecture and helped to easily understand the basics which I feel often get brushed over when beginning dissertation work.

This is quite helpful. I like how the Golden thread has been explained and the needed alignment.

This is quite helpful. I really appreciate!

The article made it simple for researcher students to differentiate between three concepts.

Very innovative and educational in approach to conducting research.

I am very impressed with all these terminology, as I am a fresh student for post graduate, I am highly guided and I promised to continue making consultation when the need arise. Thanks a lot.

A very helpful piece. thanks, I really appreciate it .

Very well explained, and it might be helpful to many people like me.

Wish i had found this (and other) resource(s) at the beginning of my PhD journey… not in my writing up year… 😩 Anyways… just a quick question as i’m having some issues ordering my “golden thread”…. does it matter in what order you mention them? i.e., is it always first aims, then objectives, and finally the questions? or can you first mention the research questions and then the aims and objectives?

Thank you for a very simple explanation that builds upon the concepts in a very logical manner. Just prior to this, I read the research hypothesis article, which was equally very good. This met my primary objective.

My secondary objective was to understand the difference between research questions and research hypothesis, and in which context to use which one. However, I am still not clear on this. Can you kindly please guide?

In research, a research question is a clear and specific inquiry that the researcher wants to answer, while a research hypothesis is a tentative statement or prediction about the relationship between variables or the expected outcome of the study. Research questions are broader and guide the overall study, while hypotheses are specific and testable statements used in quantitative research. Research questions identify the problem, while hypotheses provide a focus for testing in the study.

Exactly what I need in this research journey, I look forward to more of your coaching videos.

This helped a lot. Thanks so much for the effort put into explaining it.

What data source in writing dissertation/Thesis requires?

What is data source covers when writing dessertation/thesis

This is quite useful thanks

I’m excited and thankful. I got so much value which will help me progress in my thesis.

where are the locations of the reserch statement, research objective and research question in a reserach paper? Can you write an ouline that defines their places in the researh paper?

Very helpful and important tips on Aims, Objectives and Questions.

Thank you so much for making research aim, research objectives and research question so clear. This will be helpful to me as i continue with my thesis.

Thanks much for this content. I learned a lot. And I am inspired to learn more. I am still struggling with my preparation for dissertation outline/proposal. But I consistently follow contents and tutorials and the new FB of GRAD Coach. Hope to really become confident in writing my dissertation and successfully defend it.

As a researcher and lecturer, I find splitting research goals into research aims, objectives, and questions is unnecessarily bureaucratic and confusing for students. For most biomedical research projects, including ‘real research’, 1-3 research questions will suffice (numbers may differ by discipline).

Awesome! Very important resources and presented in an informative way to easily understand the golden thread. Indeed, thank you so much.

Well explained

The blog article on research aims, objectives, and questions by Grad Coach is a clear and insightful guide that aligns with my experiences in academic research. The article effectively breaks down the often complex concepts of research aims and objectives, providing a straightforward and accessible explanation. Drawing from my own research endeavors, I appreciate the practical tips offered, such as the need for specificity and clarity when formulating research questions. The article serves as a valuable resource for students and researchers, offering a concise roadmap for crafting well-defined research goals and objectives. Whether you’re a novice or an experienced researcher, this article provides practical insights that contribute to the foundational aspects of a successful research endeavor.

A great thanks for you. it is really amazing explanation. I grasp a lot and one step up to research knowledge.

I really found these tips helpful. Thank you very much Grad Coach.

I found this article helpful. Thanks for sharing this.

thank you so much, the explanation and examples are really helpful

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Good Research Question (w/ Examples)

What is a Research Question?

A research question is the main question that your study sought or is seeking to answer. A clear research question guides your research paper or thesis and states exactly what you want to find out, giving your work a focus and objective. Learning how to write a hypothesis or research question is the start to composing any thesis, dissertation, or research paper. It is also one of the most important sections of a research proposal .

A good research question not only clarifies the writing in your study; it provides your readers with a clear focus and facilitates their understanding of your research topic, as well as outlining your study’s objectives. Before drafting the paper and receiving research paper editing (and usually before performing your study), you should write a concise statement of what this study intends to accomplish or reveal.

Research Question Writing Tips

Listed below are the important characteristics of a good research question:

A good research question should:

- Be clear and provide specific information so readers can easily understand the purpose.

- Be focused in its scope and narrow enough to be addressed in the space allowed by your paper

- Be relevant and concise and express your main ideas in as few words as possible, like a hypothesis.

- Be precise and complex enough that it does not simply answer a closed “yes or no” question, but requires an analysis of arguments and literature prior to its being considered acceptable.

- Be arguable or testable so that answers to the research question are open to scrutiny and specific questions and counterarguments.

Some of these characteristics might be difficult to understand in the form of a list. Let’s go into more detail about what a research question must do and look at some examples of research questions.

The research question should be specific and focused

Research questions that are too broad are not suitable to be addressed in a single study. One reason for this can be if there are many factors or variables to consider. In addition, a sample data set that is too large or an experimental timeline that is too long may suggest that the research question is not focused enough.

A specific research question means that the collective data and observations come together to either confirm or deny the chosen hypothesis in a clear manner. If a research question is too vague, then the data might end up creating an alternate research problem or hypothesis that you haven’t addressed in your Introduction section .

The research question should be based on the literature

An effective research question should be answerable and verifiable based on prior research because an effective scientific study must be placed in the context of a wider academic consensus. This means that conspiracy or fringe theories are not good research paper topics.

Instead, a good research question must extend, examine, and verify the context of your research field. It should fit naturally within the literature and be searchable by other research authors.

References to the literature can be in different citation styles and must be properly formatted according to the guidelines set forth by the publishing journal, university, or academic institution. This includes in-text citations as well as the Reference section .

The research question should be realistic in time, scope, and budget

There are two main constraints to the research process: timeframe and budget.

A proper research question will include study or experimental procedures that can be executed within a feasible time frame, typically by a graduate doctoral or master’s student or lab technician. Research that requires future technology, expensive resources, or follow-up procedures is problematic.

A researcher’s budget is also a major constraint to performing timely research. Research at many large universities or institutions is publicly funded and is thus accountable to funding restrictions.

The research question should be in-depth

Research papers, dissertations and theses , and academic journal articles are usually dozens if not hundreds of pages in length.

A good research question or thesis statement must be sufficiently complex to warrant such a length, as it must stand up to the scrutiny of peer review and be reproducible by other scientists and researchers.

Research Question Types

Qualitative and quantitative research are the two major types of research, and it is essential to develop research questions for each type of study.

Quantitative Research Questions

Quantitative research questions are specific. A typical research question involves the population to be studied, dependent and independent variables, and the research design.

In addition, quantitative research questions connect the research question and the research design. In addition, it is not possible to answer these questions definitively with a “yes” or “no” response. For example, scientific fields such as biology, physics, and chemistry often deal with “states,” in which different quantities, amounts, or velocities drastically alter the relevance of the research.

As a consequence, quantitative research questions do not contain qualitative, categorical, or ordinal qualifiers such as “is,” “are,” “does,” or “does not.”

Categories of quantitative research questions

Qualitative research questions.

In quantitative research, research questions have the potential to relate to broad research areas as well as more specific areas of study. Qualitative research questions are less directional, more flexible, and adaptable compared with their quantitative counterparts. Thus, studies based on these questions tend to focus on “discovering,” “explaining,” “elucidating,” and “exploring.”

Categories of qualitative research questions

Quantitative and qualitative research question examples.

Good and Bad Research Question Examples

Below are some good (and not-so-good) examples of research questions that researchers can use to guide them in crafting their own research questions.

Research Question Example 1

The first research question is too vague in both its independent and dependent variables. There is no specific information on what “exposure” means. Does this refer to comments, likes, engagement, or just how much time is spent on the social media platform?

Second, there is no useful information on what exactly “affected” means. Does the subject’s behavior change in some measurable way? Or does this term refer to another factor such as the user’s emotions?

Research Question Example 2

In this research question, the first example is too simple and not sufficiently complex, making it difficult to assess whether the study answered the question. The author could really only answer this question with a simple “yes” or “no.” Further, the presence of data would not help answer this question more deeply, which is a sure sign of a poorly constructed research topic.

The second research question is specific, complex, and empirically verifiable. One can measure program effectiveness based on metrics such as attendance or grades. Further, “bullying” is made into an empirical, quantitative measurement in the form of recorded disciplinary actions.

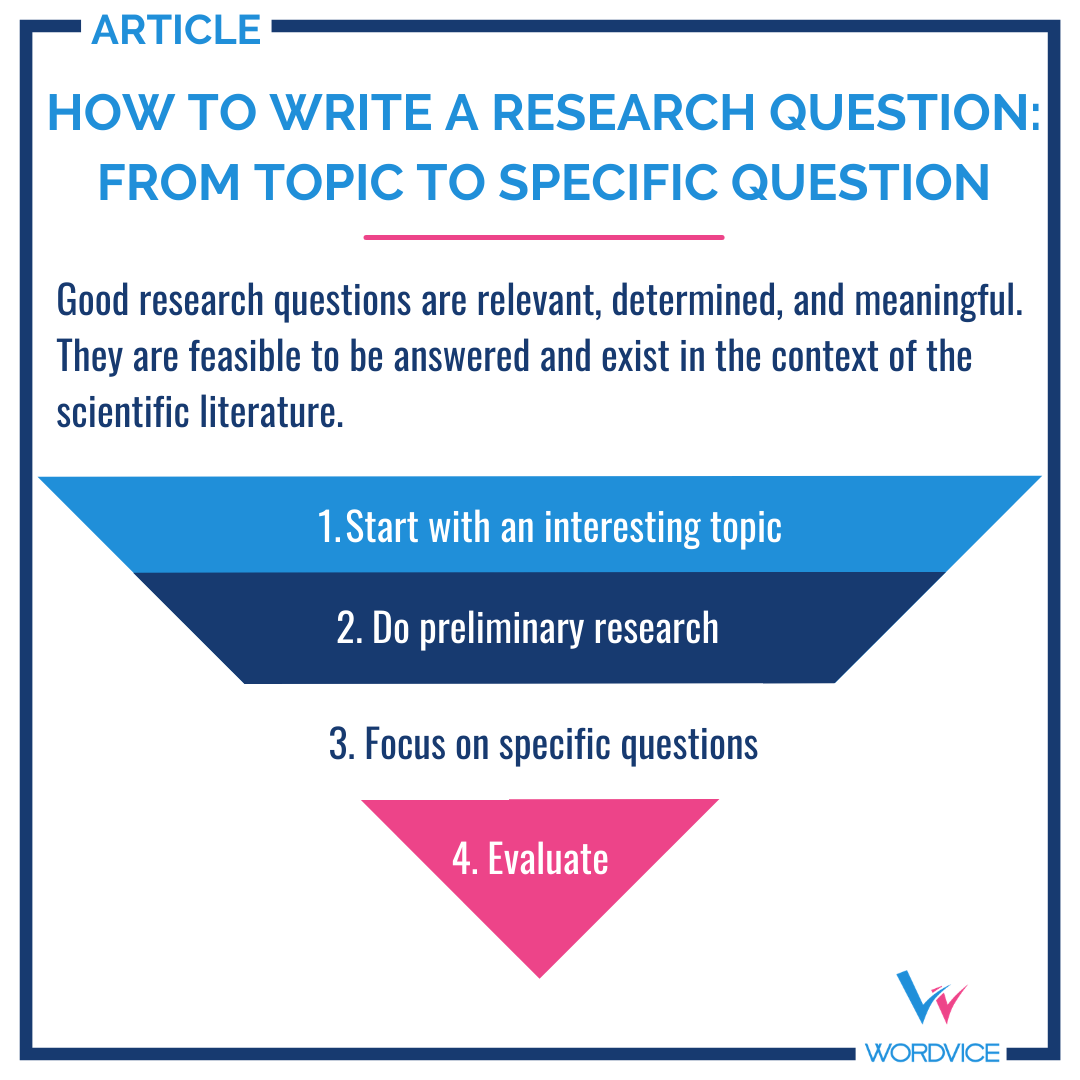

Steps for Writing a Research Question

Good research questions are relevant, focused, and meaningful. It can be difficult to come up with a good research question, but there are a few steps you can follow to make it a bit easier.

1. Start with an interesting and relevant topic

Choose a research topic that is interesting but also relevant and aligned with your own country’s culture or your university’s capabilities. Popular academic topics include healthcare and medical-related research. However, if you are attending an engineering school or humanities program, you should obviously choose a research question that pertains to your specific study and major.

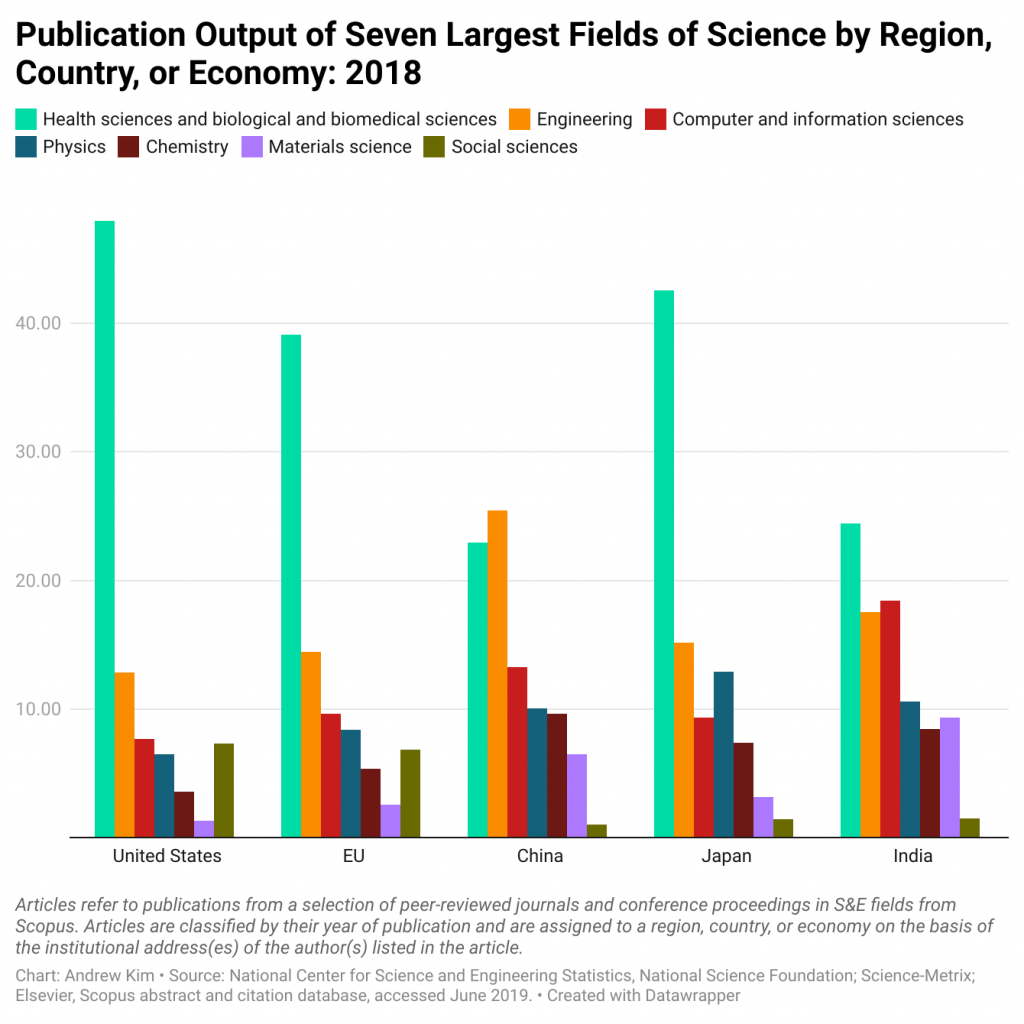

Below is an embedded graph of the most popular research fields of study based on publication output according to region. As you can see, healthcare and the basic sciences receive the most funding and earn the highest number of publications.

2. Do preliminary research

You can begin doing preliminary research once you have chosen a research topic. Two objectives should be accomplished during this first phase of research. First, you should undertake a preliminary review of related literature to discover issues that scholars and peers are currently discussing. With this method, you show that you are informed about the latest developments in the field.

Secondly, identify knowledge gaps or limitations in your topic by conducting a preliminary literature review . It is possible to later use these gaps to focus your research question after a certain amount of fine-tuning.

3. Narrow your research to determine specific research questions

You can focus on a more specific area of study once you have a good handle on the topic you want to explore. Focusing on recent literature or knowledge gaps is one good option.

By identifying study limitations in the literature and overlooked areas of study, an author can carve out a good research question. The same is true for choosing research questions that extend or complement existing literature.

4. Evaluate your research question

Make sure you evaluate the research question by asking the following questions:

Is my research question clear?

The resulting data and observations that your study produces should be clear. For quantitative studies, data must be empirical and measurable. For qualitative, the observations should be clearly delineable across categories.

Is my research question focused and specific?

A strong research question should be specific enough that your methodology or testing procedure produces an objective result, not one left to subjective interpretation. Open-ended research questions or those relating to general topics can create ambiguous connections between the results and the aims of the study.

Is my research question sufficiently complex?

The result of your research should be consequential and substantial (and fall sufficiently within the context of your field) to warrant an academic study. Simply reinforcing or supporting a scientific consensus is superfluous and will likely not be well received by most journal editors.

Editing Your Research Question

Your research question should be fully formulated well before you begin drafting your research paper. However, you can receive English paper editing and proofreading services at any point in the drafting process. Language editors with expertise in your academic field can assist you with the content and language in your Introduction section or other manuscript sections. And if you need further assistance or information regarding paper compositions, in the meantime, check out our academic resources , which provide dozens of articles and videos on a variety of academic writing and publication topics.

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Research Questions & Hypotheses

Generally, in quantitative studies, reviewers expect hypotheses rather than research questions. However, both research questions and hypotheses serve different purposes and can be beneficial when used together.

Research Questions

Clarify the research’s aim (farrugia et al., 2010).

- Research often begins with an interest in a topic, but a deep understanding of the subject is crucial to formulate an appropriate research question.

- Descriptive: “What factors most influence the academic achievement of senior high school students?”

- Comparative: “What is the performance difference between teaching methods A and B?”

- Relationship-based: “What is the relationship between self-efficacy and academic achievement?”

- Increasing knowledge about a subject can be achieved through systematic literature reviews, in-depth interviews with patients (and proxies), focus groups, and consultations with field experts.

- Some funding bodies, like the Canadian Institute for Health Research, recommend conducting a systematic review or a pilot study before seeking grants for full trials.

- The presence of multiple research questions in a study can complicate the design, statistical analysis, and feasibility.

- It’s advisable to focus on a single primary research question for the study.

- The primary question, clearly stated at the end of a grant proposal’s introduction, usually specifies the study population, intervention, and other relevant factors.

- The FINER criteria underscore aspects that can enhance the chances of a successful research project, including specifying the population of interest, aligning with scientific and public interest, clinical relevance, and contribution to the field, while complying with ethical and national research standards.

- The P ICOT approach is crucial in developing the study’s framework and protocol, influencing inclusion and exclusion criteria and identifying patient groups for inclusion.

- Defining the specific population, intervention, comparator, and outcome helps in selecting the right outcome measurement tool.

- The more precise the population definition and stricter the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the more significant the impact on the interpretation, applicability, and generalizability of the research findings.

- A restricted study population enhances internal validity but may limit the study’s external validity and generalizability to clinical practice.

- A broadly defined study population may better reflect clinical practice but could increase bias and reduce internal validity.

- An inadequately formulated research question can negatively impact study design, potentially leading to ineffective outcomes and affecting publication prospects.

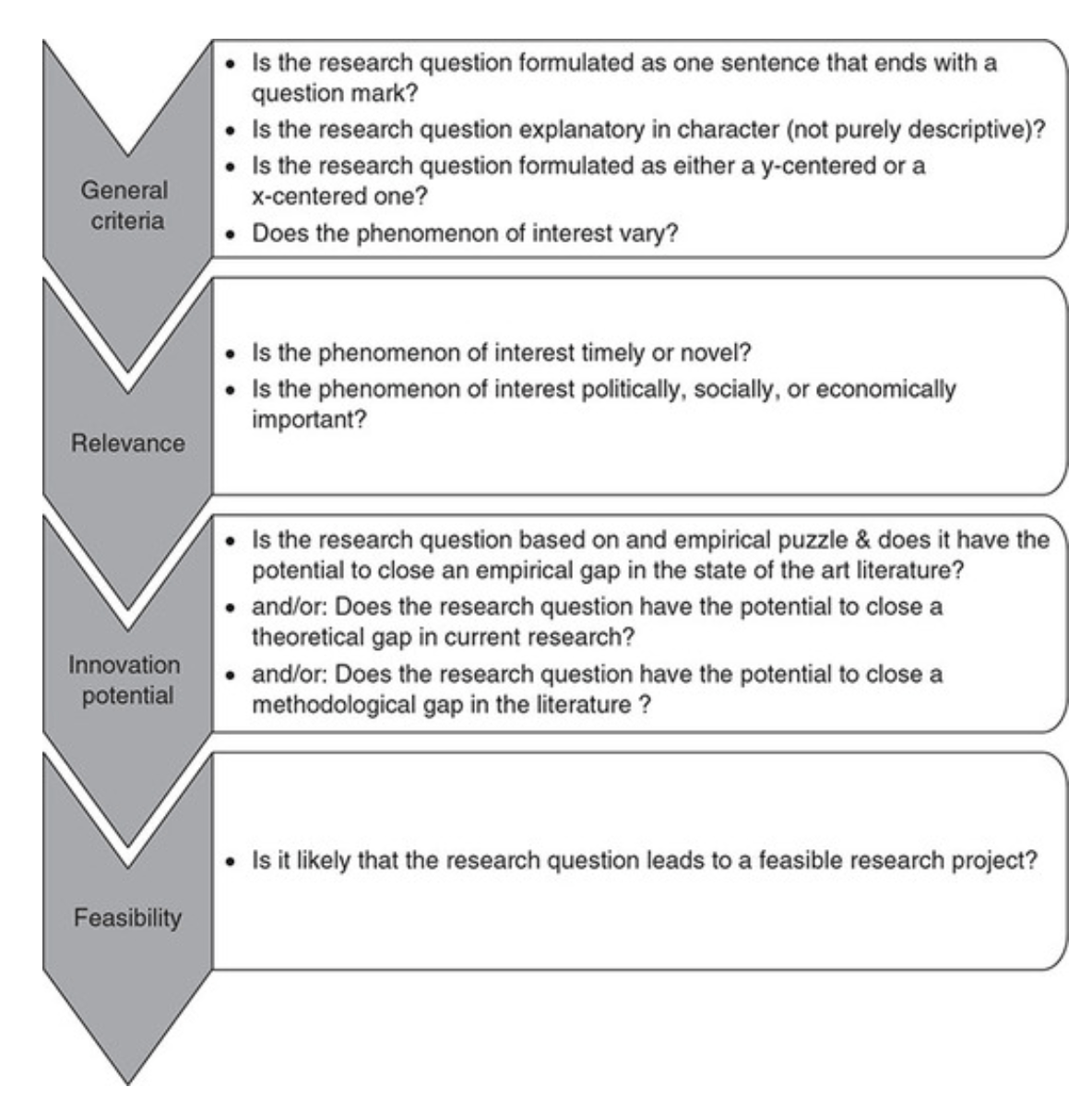

Checklist: Good research questions for social science projects (Panke, 2018)

Research Hypotheses

Present the researcher’s predictions based on specific statements.

- These statements define the research problem or issue and indicate the direction of the researcher’s predictions.

- Formulating the research question and hypothesis from existing data (e.g., a database) can lead to multiple statistical comparisons and potentially spurious findings due to chance.

- The research or clinical hypothesis, derived from the research question, shapes the study’s key elements: sampling strategy, intervention, comparison, and outcome variables.

- Hypotheses can express a single outcome or multiple outcomes.

- After statistical testing, the null hypothesis is either rejected or not rejected based on whether the study’s findings are statistically significant.

- Hypothesis testing helps determine if observed findings are due to true differences and not chance.

- Hypotheses can be 1-sided (specific direction of difference) or 2-sided (presence of a difference without specifying direction).

- 2-sided hypotheses are generally preferred unless there’s a strong justification for a 1-sided hypothesis.

- A solid research hypothesis, informed by a good research question, influences the research design and paves the way for defining clear research objectives.

Types of Research Hypothesis

- In a Y-centered research design, the focus is on the dependent variable (DV) which is specified in the research question. Theories are then used to identify independent variables (IV) and explain their causal relationship with the DV.

- Example: “An increase in teacher-led instructional time (IV) is likely to improve student reading comprehension scores (DV), because extensive guided practice under expert supervision enhances learning retention and skill mastery.”

- Hypothesis Explanation: The dependent variable (student reading comprehension scores) is the focus, and the hypothesis explores how changes in the independent variable (teacher-led instructional time) affect it.

- In X-centered research designs, the independent variable is specified in the research question. Theories are used to determine potential dependent variables and the causal mechanisms at play.

- Example: “Implementing technology-based learning tools (IV) is likely to enhance student engagement in the classroom (DV), because interactive and multimedia content increases student interest and participation.”

- Hypothesis Explanation: The independent variable (technology-based learning tools) is the focus, with the hypothesis exploring its impact on a potential dependent variable (student engagement).

- Probabilistic hypotheses suggest that changes in the independent variable are likely to lead to changes in the dependent variable in a predictable manner, but not with absolute certainty.

- Example: “The more teachers engage in professional development programs (IV), the more their teaching effectiveness (DV) is likely to improve, because continuous training updates pedagogical skills and knowledge.”

- Hypothesis Explanation: This hypothesis implies a probable relationship between the extent of professional development (IV) and teaching effectiveness (DV).

- Deterministic hypotheses state that a specific change in the independent variable will lead to a specific change in the dependent variable, implying a more direct and certain relationship.

- Example: “If the school curriculum changes from traditional lecture-based methods to project-based learning (IV), then student collaboration skills (DV) are expected to improve because project-based learning inherently requires teamwork and peer interaction.”

- Hypothesis Explanation: This hypothesis presumes a direct and definite outcome (improvement in collaboration skills) resulting from a specific change in the teaching method.

- Example : “Students who identify as visual learners will score higher on tests that are presented in a visually rich format compared to tests presented in a text-only format.”

- Explanation : This hypothesis aims to describe the potential difference in test scores between visual learners taking visually rich tests and text-only tests, without implying a direct cause-and-effect relationship.

- Example : “Teaching method A will improve student performance more than method B.”

- Explanation : This hypothesis compares the effectiveness of two different teaching methods, suggesting that one will lead to better student performance than the other. It implies a direct comparison but does not necessarily establish a causal mechanism.

- Example : “Students with higher self-efficacy will show higher levels of academic achievement.”

- Explanation : This hypothesis predicts a relationship between the variable of self-efficacy and academic achievement. Unlike a causal hypothesis, it does not necessarily suggest that one variable causes changes in the other, but rather that they are related in some way.

Tips for developing research questions and hypotheses for research studies

- Perform a systematic literature review (if one has not been done) to increase knowledge and familiarity with the topic and to assist with research development.

- Learn about current trends and technological advances on the topic.

- Seek careful input from experts, mentors, colleagues, and collaborators to refine your research question as this will aid in developing the research question and guide the research study.

- Use the FINER criteria in the development of the research question.

- Ensure that the research question follows PICOT format.

- Develop a research hypothesis from the research question.

- Ensure that the research question and objectives are answerable, feasible, and clinically relevant.

If your research hypotheses are derived from your research questions, particularly when multiple hypotheses address a single question, it’s recommended to use both research questions and hypotheses. However, if this isn’t the case, using hypotheses over research questions is advised. It’s important to note these are general guidelines, not strict rules. If you opt not to use hypotheses, consult with your supervisor for the best approach.

Farrugia, P., Petrisor, B. A., Farrokhyar, F., & Bhandari, M. (2010). Practical tips for surgical research: Research questions, hypotheses and objectives. Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie , 53 (4), 278–281.

Hulley, S. B., Cummings, S. R., Browner, W. S., Grady, D., & Newman, T. B. (2007). Designing clinical research. Philadelphia.

Panke, D. (2018). Research design & method selection: Making good choices in the social sciences. Research Design & Method Selection , 1-368.

- Advanced search

Advanced Search

Research questions, hypotheses and objectives

- Find this author on Google Scholar

- Find this author on PubMed

- Search for this author on this site

- For correspondence: [email protected]

- Figures & Tables

There is an increasing familiarity with the principles of evidence-based medicine in the surgical community. As surgeons become more aware of the hierarchy of evidence, grades of recommendations and the principles of critical appraisal, they develop an increasing familiarity with research design. Surgeons and clinicians are looking more and more to the literature and clinical trials to guide their practice; as such, it is becoming a responsibility of the clinical research community to attempt to answer questions that are not only well thought out but also clinically relevant. The development of the research question, including a supportive hypothesis and objectives, is a necessary key step in producing clinically relevant results to be used in evidence-based practice. A well-defined and specific research question is more likely to help guide us in making decisions about study design and population and subsequently what data will be collected and analyzed. 1

Objectives of this article

In this article, we discuss important considerations in the development of a research question and hypothesis and in defining objectives for research. By the end of this article, the reader will be able to appreciate the significance of constructing a good research question and developing hypotheses and research objectives for the successful design of a research study. The following article is divided into 3 sections: research question, research hypothesis and research objectives.

Research question

Interest in a particular topic usually begins the research process, but it is the familiarity with the subject that helps define an appropriate research question for a study. 1 Questions then arise out of a perceived knowledge deficit within a subject area or field of study. 2 Indeed, Haynes suggests that it is important to know “where the boundary between current knowledge and ignorance lies.” 1 The challenge in developing an appropriate research question is in determining which clinical uncertainties could or should be studied and also rationalizing the need for their investigation.

Increasing one’s knowledge about the subject of interest can be accomplished in many ways. Appropriate methods include systematically searching the literature, in-depth interviews and focus groups with patients (and proxies) and interviews with experts in the field. In addition, awareness of current trends and technological advances can assist with the development of research questions. 2 It is imperative to understand what has been studied about a topic to date in order to further the knowledge that has been previously gathered on a topic. Indeed, some granting institutions (e.g., Canadian Institute for Health Research) encourage applicants to conduct a systematic review of the available evidence if a recent review does not already exist and preferably a pilot or feasibility study before applying for a grant for a full trial.

In-depth knowledge about a subject may generate a number of questions. It then becomes necessary to ask whether these questions can be answered through one study or if more than one study needed. 1 Additional research questions can be developed, but several basic principles should be taken into consideration. 1 All questions, primary and secondary, should be developed at the beginning and planning stages of a study. Any additional questions should never compromise the primary question because it is the primary research question that forms the basis of the hypothesis and study objectives. It must be kept in mind that within the scope of one study, the presence of a number of research questions will affect and potentially increase the complexity of both the study design and subsequent statistical analyses, not to mention the actual feasibility of answering every question. 1 A sensible strategy is to establish a single primary research question around which to focus the study plan. 3 In a study, the primary research question should be clearly stated at the end of the introduction of the grant proposal, and it usually specifies the population to be studied, the intervention to be implemented and other circumstantial factors. 4

Hulley and colleagues 2 have suggested the use of the FINER criteria in the development of a good research question ( Box 1 ). The FINER criteria highlight useful points that may increase the chances of developing a successful research project. A good research question should specify the population of interest, be of interest to the scientific community and potentially to the public, have clinical relevance and further current knowledge in the field (and of course be compliant with the standards of ethical boards and national research standards).

FINER criteria for a good research question

Adapted with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health. 2

Whereas the FINER criteria outline the important aspects of the question in general, a useful format to use in the development of a specific research question is the PICO format — consider the population (P) of interest, the intervention (I) being studied, the comparison (C) group (or to what is the intervention being compared) and the outcome of interest (O). 3 , 5 , 6 Often timing (T) is added to PICO ( Box 2 ) — that is, “Over what time frame will the study take place?” 1 The PICOT approach helps generate a question that aids in constructing the framework of the study and subsequently in protocol development by alluding to the inclusion and exclusion criteria and identifying the groups of patients to be included. Knowing the specific population of interest, intervention (and comparator) and outcome of interest may also help the researcher identify an appropriate outcome measurement tool. 7 The more defined the population of interest, and thus the more stringent the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the greater the effect on the interpretation and subsequent applicability and generalizability of the research findings. 1 , 2 A restricted study population (and exclusion criteria) may limit bias and increase the internal validity of the study; however, this approach will limit external validity of the study and, thus, the generalizability of the findings to the practical clinical setting. Conversely, a broadly defined study population and inclusion criteria may be representative of practical clinical practice but may increase bias and reduce the internal validity of the study.

PICOT criteria 1

A poorly devised research question may affect the choice of study design, potentially lead to futile situations and, thus, hamper the chance of determining anything of clinical significance, which will then affect the potential for publication. Without devoting appropriate resources to developing the research question, the quality of the study and subsequent results may be compromised. During the initial stages of any research study, it is therefore imperative to formulate a research question that is both clinically relevant and answerable.

Research hypothesis

The primary research question should be driven by the hypothesis rather than the data. 1 , 2 That is, the research question and hypothesis should be developed before the start of the study. This sounds intuitive; however, if we take, for example, a database of information, it is potentially possible to perform multiple statistical comparisons of groups within the database to find a statistically significant association. This could then lead one to work backward from the data and develop the “question.” This is counterintuitive to the process because the question is asked specifically to then find the answer, thus collecting data along the way (i.e., in a prospective manner). Multiple statistical testing of associations from data previously collected could potentially lead to spuriously positive findings of association through chance alone. 2 Therefore, a good hypothesis must be based on a good research question at the start of a trial and, indeed, drive data collection for the study.

The research or clinical hypothesis is developed from the research question and then the main elements of the study — sampling strategy, intervention (if applicable), comparison and outcome variables — are summarized in a form that establishes the basis for testing, statistical and ultimately clinical significance. 3 For example, in a research study comparing computer-assisted acetabular component insertion versus freehand acetabular component placement in patients in need of total hip arthroplasty, the experimental group would be computer-assisted insertion and the control/conventional group would be free-hand placement. The investigative team would first state a research hypothesis. This could be expressed as a single outcome (e.g., computer-assisted acetabular component placement leads to improved functional outcome) or potentially as a complex/composite outcome; that is, more than one outcome (e.g., computer-assisted acetabular component placement leads to both improved radiographic cup placement and improved functional outcome).

However, when formally testing statistical significance, the hypothesis should be stated as a “null” hypothesis. 2 The purpose of hypothesis testing is to make an inference about the population of interest on the basis of a random sample taken from that population. The null hypothesis for the preceding research hypothesis then would be that there is no difference in mean functional outcome between the computer-assisted insertion and free-hand placement techniques. After forming the null hypothesis, the researchers would form an alternate hypothesis stating the nature of the difference, if it should appear. The alternate hypothesis would be that there is a difference in mean functional outcome between these techniques. At the end of the study, the null hypothesis is then tested statistically. If the findings of the study are not statistically significant (i.e., there is no difference in functional outcome between the groups in a statistical sense), we cannot reject the null hypothesis, whereas if the findings were significant, we can reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternate hypothesis (i.e., there is a difference in mean functional outcome between the study groups), errors in testing notwithstanding. In other words, hypothesis testing confirms or refutes the statement that the observed findings did not occur by chance alone but rather occurred because there was a true difference in outcomes between these surgical procedures. The concept of statistical hypothesis testing is complex, and the details are beyond the scope of this article.

Another important concept inherent in hypothesis testing is whether the hypotheses will be 1-sided or 2-sided. A 2-sided hypothesis states that there is a difference between the experimental group and the control group, but it does not specify in advance the expected direction of the difference. For example, we asked whether there is there an improvement in outcomes with computer-assisted surgery or whether the outcomes worse with computer-assisted surgery. We presented a 2-sided test in the above example because we did not specify the direction of the difference. A 1-sided hypothesis states a specific direction (e.g., there is an improvement in outcomes with computer-assisted surgery). A 2-sided hypothesis should be used unless there is a good justification for using a 1-sided hypothesis. As Bland and Atlman 8 stated, “One-sided hypothesis testing should never be used as a device to make a conventionally nonsignificant difference significant.”

The research hypothesis should be stated at the beginning of the study to guide the objectives for research. Whereas the investigators may state the hypothesis as being 1-sided (there is an improvement with treatment), the study and investigators must adhere to the concept of clinical equipoise. According to this principle, a clinical (or surgical) trial is ethical only if the expert community is uncertain about the relative therapeutic merits of the experimental and control groups being evaluated. 9 It means there must exist an honest and professional disagreement among expert clinicians about the preferred treatment. 9

Designing a research hypothesis is supported by a good research question and will influence the type of research design for the study. Acting on the principles of appropriate hypothesis development, the study can then confidently proceed to the development of the research objective.

Research objective

The primary objective should be coupled with the hypothesis of the study. Study objectives define the specific aims of the study and should be clearly stated in the introduction of the research protocol. 7 From our previous example and using the investigative hypothesis that there is a difference in functional outcomes between computer-assisted acetabular component placement and free-hand placement, the primary objective can be stated as follows: this study will compare the functional outcomes of computer-assisted acetabular component insertion versus free-hand placement in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. Note that the study objective is an active statement about how the study is going to answer the specific research question. Objectives can (and often do) state exactly which outcome measures are going to be used within their statements. They are important because they not only help guide the development of the protocol and design of study but also play a role in sample size calculations and determining the power of the study. 7 These concepts will be discussed in other articles in this series.

From the surgeon’s point of view, it is important for the study objectives to be focused on outcomes that are important to patients and clinically relevant. For example, the most methodologically sound randomized controlled trial comparing 2 techniques of distal radial fixation would have little or no clinical impact if the primary objective was to determine the effect of treatment A as compared to treatment B on intraoperative fluoroscopy time. However, if the objective was to determine the effect of treatment A as compared to treatment B on patient functional outcome at 1 year, this would have a much more significant impact on clinical decision-making. Second, more meaningful surgeon–patient discussions could ensue, incorporating patient values and preferences with the results from this study. 6 , 7 It is the precise objective and what the investigator is trying to measure that is of clinical relevance in the practical setting.

The following is an example from the literature about the relation between the research question, hypothesis and study objectives:

Study: Warden SJ, Metcalf BR, Kiss ZS, et al. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound for chronic patellar tendinopathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Rheumatology 2008;47:467–71.

Research question: How does low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) compare with a placebo device in managing the symptoms of skeletally mature patients with patellar tendinopathy?

Research hypothesis: Pain levels are reduced in patients who receive daily active-LIPUS (treatment) for 12 weeks compared with individuals who receive inactive-LIPUS (placebo).

Objective: To investigate the clinical efficacy of LIPUS in the management of patellar tendinopathy symptoms.

The development of the research question is the most important aspect of a research project. A research project can fail if the objectives and hypothesis are poorly focused and underdeveloped. Useful tips for surgical researchers are provided in Box 3 . Designing and developing an appropriate and relevant research question, hypothesis and objectives can be a difficult task. The critical appraisal of the research question used in a study is vital to the application of the findings to clinical practice. Focusing resources, time and dedication to these 3 very important tasks will help to guide a successful research project, influence interpretation of the results and affect future publication efforts.

Tips for developing research questions, hypotheses and objectives for research studies

Perform a systematic literature review (if one has not been done) to increase knowledge and familiarity with the topic and to assist with research development.

Learn about current trends and technological advances on the topic.

Seek careful input from experts, mentors, colleagues and collaborators to refine your research question as this will aid in developing the research question and guide the research study.

Use the FINER criteria in the development of the research question.

Ensure that the research question follows PICOT format.

Develop a research hypothesis from the research question.

Develop clear and well-defined primary and secondary (if needed) objectives.

Ensure that the research question and objectives are answerable, feasible and clinically relevant.

FINER = feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, relevant; PICOT = population (patients), intervention (for intervention studies only), comparison group, outcome of interest, time.

Competing interests: No funding was received in preparation of this paper. Dr. Bhandari was funded, in part, by a Canada Research Chair, McMaster University.

- Accepted January 27, 2009.

- Brian Haynes R

- Cummings S ,

- Browner W ,

- Sackett D ,

- Strauss S ,

- Richardson W ,

- Fisher CG ,

- Haynes RB ,

- Sackett DL ,

- Guyatt GH ,

In this issue

- Table of Contents

- Index by author

Article tools

Thank you for your interest in spreading the word on CJS.

NOTE: We only request your email address so that the person you are recommending the page to knows that you wanted them to see it, and that it is not junk mail. We do not capture any email address.

Citation Manager Formats

- EndNote (tagged)

- EndNote 8 (xml)

- RefWorks Tagged

- Ref Manager

- Tweet Widget

- Facebook Like

Related Articles

- No related articles found.

- Google Scholar

Cited By...

- How to Conduct a Randomized Controlled Trial

- Formulating the Research Question and Framing the Hypothesis

Similar Articles

Setting a research question, aim and objective

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Limerick, Limerick, Republic of Ireland.

- 2 Department of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Limerick, Republic of Ireland.

- PMID: 26997231

- DOI: 10.7748/nr.23.4.19.s5

Aim: To describe the development of a research question, aim and objective.

Background: The first steps of any study are developing the research question, aim and objective. Subsequent steps develop from these and they govern the researchers' choice of population, setting, data to be collected and time period for the study. Clear, succinctly posed research questions, aims and objectives are essential if studies are to be successful.

Discussion: Researchers developing their research questions, aims and objectives generally experience difficulties. They are often overwhelmed trying to convert what they see as a relevant issue from practice into research. This necessitates engaging with the relevant published literature and knowledgeable people.

Conclusion: This paper identifies the issues to be considered when developing a research question, aim and objective. Understanding these considerations will enable researchers to effectively present their research question, aim and objective.

Implications for practice: To conduct successful studies, researchers should develop clear research questions, aims and objectives.

Keywords: novice researchers; nursing research; research aim; research objective; research question; study development.

- Nursing Research / methods

- Nursing Research / organization & administration*

- Organizational Objectives

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.14(9); 2022 Sep

Research Question, Objectives, and Endpoints in Clinical and Oncological Research: A Comprehensive Review

Addanki purna singh.

1 Physiology, Saint James School of Medicine, The Quarter, AIA

Praveen R Shahapur

2 Microbiology, Bijapur Lingayat District Educational Association (BLDE, Deemed to be University) Shri B.M. Patil Medical College, Vijayapur, IND

Sabitha Vadakedath

3 Biochemistry, Prathima Institute of Medical Sciences, Karimnagar, IND

Vallab Ganesh Bharadwaj

4 Microbiology, Trichy Sri Ramasamy Memorial (SRM) Medical College Hospital & Research Centre, Tiruchirapalli, IND

Dr Pranay Kumar

5 Anatomy, Prathima Institute of Medical Sciences, Karimnagar , IND

Venkata BharatKumar Pinnelli

6 Biochemistry, Vydehi Institute of Medical Science & Research Center, Bangalore, IND

Vikram Godishala

7 Biotechnology, Ganapathy Degree College, Parkal, IND

Venkataramana Kandi

8 Clinical Microbiology, Prathima Institute of Medical Sciences, Karimnagar, IND

Clinical research is a systematic process of conducting research work to find solutions for human health-related problems. It is applied to understand the disease process and assist in the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Currently, we are experiencing global unrest caused by the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. The novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has been responsible for the deaths of more than 50 million people worldwide. Also, it has resulted in severe morbidity among the affected population. The cause of such a huge amount of influence on human health by the pandemic was the unavailability of drugs and therapeutic interventions to treat and manage the disease. Cancer is a disease condition wherein the normal cell function is deranged, and the cells multiply in an uncontrolled manner. Based on recent reports by the World Health Organization (WHO), cancer is the second leading cause of death globally. Moreover, the rates of cancers have shown an increasing trend in the past decade. Therefore, it is essential to improve the understanding concerning clinical research to address the health concerns of humans. In this review, we comprehensively discuss critical aspects of clinical research that include the research question, research objectives, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), intention-to-treat and per-protocol analysis, and endpoints in clinical and oncological research.

Introduction and background

Successful clinical research can be conducted by well-trained researchers. Other essential factors of clinical research include framing a research question and relevant objectives, documenting, and recording research outcomes, and outcome measures, sample size, and research methodology including the type of randomization, among others [ 1 , 2 ].

Clinicians/physicians and surgeons are increasingly dependent on the clinical research results for improved management of patients. Therefore, researchers need to work upon a relevant research question/hypothesis and specific objectives that may potentially deliver results that can be translated into practice in the form of evidence-based medicine [ 3 ].

Essential elements that facilitate a researcher to frame a research question are in-depth knowledge of the subject and identifying possible gaps. Moreover, the feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, relevant (FINER) approach and the population of interest/target group, intervention, comparison group, outcome of interest, and time of study (PICOT) approach were previously suggested for researchers to be able to frame appropriate research questions [ 4 ].

Moreover, the research objectives should be framed by the researcher before the initiation of the study: a specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-defined (SMART) approach is utilized to devise the objectives based on the research question. It is preferable to have a single primary objective whereas the secondary objectives can be multiple and may be dependent on the amount of data collected. The objectives must be simple and specific and must reflect the research question [ 5 , 6 ].

Given the evolution and the increasing requirement for emergency care, clinical researchers are advised to adopt a population, exposure, comparator, outcome (PECO)/ population, exposure, comparator, outcome (PICO) approach to construct the study objectives and carry out quantitative research. In contrast, qualitative research which is carried out to understand, explore, and examine requires the researcher to understand what and why the research is undertaken along with the roles of the researcher, research process/steps, and participants [ 7 , 8 ].

Since clinical research is envisaged in finding a solution to a health problem, choosing the appropriate endpoint requires special focus. The endpoints are the specific measures of the outcomes of an intervention and therefore they must be chosen judiciously [ 9 ]. The endpoints in a clinical trial can be single or multiple in numbers. The primary endpoints assess the major research question, and the secondary endpoints may assess alternative research questions. Moreover, there are other endpoints like surrogate endpoints, intermediate clinical endpoints, clinical outcomes, clinical outcome assessments, clinician-reported outcomes, observer-reported outcomes, patient-reported outcomes, and performance outcomes [ 10 ] (Figure (Figure1 1 ).

This figure has been created by the authors

The clinical trial endpoints are essentially the indicators of the power of the interventions either to cure or control the disease progression. Due to the cost and the tedious nature of the clinical trials, it is suggested that multiple-arm trials that include more than one primary endpoint be used [ 11 ]. Integration of the primary endpoints with the patient prioritized endpoints was recently suggested especially among cardiovascular disease patients [ 12 ]. Cancer research is an increasingly evolving area because of the unavailability of therapeutic interventions for some malignancies like breast and lung cancer, among others [ 13 , 14 ]. Moreover, the drugs available for treating cancers are plagued by adverse reactions. However, since most cancer clinical trials apply overall survival as the preferred and gold standard clinical endpoint, it is difficult for the trial operators to sustain the costs associated with the long lengths of the study that follow-up patients for years to assess the clinical outcomes after interventions. In this study, we comprehensively review the essential elements of clinical research that include the research question, hypothesis, and clinical and oncological endpoints.

Research question

A research question can alternatively be called the aim of the researcher. It describes the problem that the researcher intends to solve vis-à-vis finding an answer to a question. A research question is the first step toward any kind of research process that includes both qualitative as well as quantitative research. Since the research question predicts the core of any project, it must be carefully framed. The essential elements to consider while determining a research question are feasibility, preciseness, and relevance to the real world.

A person interested in a broad subject area must first complete extensive reading of the available literature. This enables the researcher to find out the strengths, loopholes, deficiencies, and missing links that can form the basis for framing a research question. The problem to which a solution needs to be found and the potential causes/reasons for the problems help a researcher frame the research question.

The research questions should be framed in such a way that the researcher will find several possibilities as solutions to the research question rather than a simple yes or no. Among the various factors that determine the power of a research question, the most essential ones include the ability of research questions to find complex answers, focussed, and the specific nature of the question. The research questions must be answerable, debatable, and researchable [ 15 , 16 ]. Research questions differ from the type of research method selected by the researcher as shown in Figure Figure2 2 .

FINER: Feasible, interesting, novel, ethical, relevant; PICOT: Population of interest/target group, intervention, comparison group, outcome of interest, time of study; PECO: Population, exposure, comparator, outcome; PICO: Population, intervention, comparator, outcome; SMART: Specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time defined; COVID-19: Coronavirus disease-19

Hypothesis testing

A hypothesis is an assumption by the researcher that the answers drawn with reference to the research question are either true or false. The researcher performs hypothesis testing by using appropriate statistical methods on the data collected from the research.

The hypothesis is an assumption/observation of the researcher regarding the outcome of potential research that is being conducted. There are two types of hypotheses, the null hypothesis (H0), wherein, the researcher assumes that there is no relation/causality/effect. The alternate hypothesis (HA) is when the researcher believes/assumes that there is a relationship/effect [ 17 ]. Basically, there are two types of errors while testing a hypothesis. Type I error (α) (false positive) is when the researcher rejects the null hypothesis although it is true. Type II error (β) (false negative) is when the researcher accepts the null hypothesis although it is false.

The errors in hypothesis testing occur because of bias among many other reasons in the study. Many studies set the power of the studies to essentially rule out errors. Researchers consider 5% chance (α=0.05; range: 0.01-0.10) of error in case of a type I error and up to 20% chance (β =0.20; range: 0.05-0.20) in case of type II errors [ 18 ]. The characteristics of a good hypothesis are simple and specific. Moreover, it must be decided by the researcher prior to initiating the study and while writing the study proposal/protocol [ 18 ].

Hypothesis testing means sample testing, wherein the information gathered after sample testing is inferred after applying statistical methods. A hypothesis may be generated in several ways that include observations, anatomical features, and other physiological facts observed by physicians [ 19 ]. Hypothesis testing also can be performed by using appropriate statistical methods. The testing of the hypothesis is done to prove the null hypothesis or otherwise use the sample data.

As a researcher, one must assume a null hypothesis, or believe that the alternate hypothesis holds good in the sample selected. After the collection of data, analysis, and interpretation, the researcher either accepts or rejects the hypothesis. Therefore, it must be noted that while a study is initiated, there is only a 50% chance of either the null hypothesis or the alternative hypothesis coming true [ 20 ].

The step-by-step process of hypothesis testing starts with an assumption, criteria for interpretation of results, analysis, and conclusion. The level of significance (95% free of type I error and 80% free of type II error) also is decided initially to ensure that the study results are replicated by the other researchers [ 21 ].

Objectives in clinical research

The most significant objective in clinical research is to find out whether the intervention attempted was successful in curing the disease/medical condition. It is important to understand the fact that research planning greatly influences the research results, and no statistical method can improve the results but a well-designed and conducted clinical research [ 22 ].

The primary objective of clinical research studies includes improvement in patient management. Most clinical research studies are aimed at discovering a new/novel drug to treat a medical condition that presently has no specific treatment, or the available drugs are not particularly effective in curing the disease.

The objectives are formed to address the five 'W's, namely who (children, women, etc.); what (the medical condition/disease/infection); why (causes of the medical condition/disease/infection); when (conditions responsible for the medical condition/disease/infection); and where (geographical aspects of the medical condition/disease/infection) as shown in Figure Figure3 3 .

Clinical research can be of several types including primary research and secondary research. Also, the research can be observational (no intervention) and experimental/interventional. Clearly demarcated/framed research objectives are essential to improve the clarity, specificity, and focus of the clinical trial [ 23 ].

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs)

While conducting clinical research the investigators collect trial data through clinical observations, laboratory monitoring, and caregiver feedback. There are some aspects of the data like the patient-reported outcomes (PROs) that can be reported by the subject/patient him/herself either in the form of a questionnaire or through interviews. Such data collected from the patients in their words is termed PROMs. The PROMs include a global impression of the trial, the functional status and well-being, symptoms, health-related quality of life (HRQL), treatment compliance, and satisfaction.

The questionnaire used to collect the PROs is called a PRO instrument. The data collected through this instrument is used to establish the benefit-to-risk ratio of the clinical trial drug. The PRO instruments can be designed as generic (contains a wide variety of health-related aspects and therefore can be used among different patient types), disease-specific (rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, etc.), dimension-specific (physical activity, cognitive levels, etc.), region/site-specific, individualized, utility measures, and summary items [ 24 ]. The patient-reported experience measure (PREMs), and the patient and public involvement programs are used to collect the patient’s feedback that invariably helps in improving the quality of healthcare facilities [ 25 ].

It is important to develop PROM tools/instruments for various diseases, especially among children as noted by a recent research report. This study suggested that a suitable PROM instrument is required to measure the status of disease (wheezing/asthma/respiratory diseases) and its control among preschool children [ 26 ].

Intention to treat and per-protocol analysis

The intention to treat (ITT) analysis is used when all the study subject’s data is analyzed including all those participants who were enrolled in the study, and those who have deviated (not signed the informed consent, discontinued from the study, not taken the trial drug as suggested). The ITT studies minimize the bias and ensure both the study and the control groups are compared.

The per-protocol (PP) analysis usually includes the data from only those subjects who have remained till the study period ended, have taken the drugs as suggested by the protocol, and was available for regular follow-up. The disadvantages of PP are potential disturbances in the balance between the study groups (randomized/placebo/control), a lower number of study participants due to the exclusion of dropouts, and non-compliant subjects. Therefore, the results from the PPA studies could be biased [ 27 ].

The randomized clinical trial (RCT) studies of superiority type use ITT analyses as against the non-inferiority and equivalence studies wherein an ITT approach may favor the study hypothesis.

According to the Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products (CPMP), and the Consolidated Standards for reporting trials (CONSORT), both the ITT and PP analyses must be assessed to effectively interpret the results of the clinical trial including the safety and efficacy [ 28 ].

Endpoints in clinical research

The endpoints in clinical research determine whether the clinical trial has been successful in finding out if an intervention/drug has proven beneficial in improving the survival and quality of life of the patient. The endpoints determine the validity of the clinical trial results. There are different types of endpoints like primary endpoints, secondary endpoints, tertiary endpoints, surrogate endpoints (laboratory measurements, physical signs), and others [ 9 ].

The clinical trial endpoints could be subjective and objective in nature. The objective endpoints are survival, disease progression/remission, and the development of disease/condition. The subjective endpoints include symptoms, quality of life, and other patient-reported outcomes [ 29 , 30 ]. The significance of endpoints in clinical trials and the importance of choosing appropriate endpoints were previously reported. This study suggested that the primary endpoints help in deriving the sample size and confirm the generalizability of the results. The secondary and surrogate endpoints could be used while conducting the clinical research without ignoring the aspects of the quality of life of the subjects [ 31 ].

Endpoints in oncology clinical trials

Cancer clinical trials assume increased significance because the drugs developed against the cancer are intended to increase the survival of the patients. Also, anti-cancer agents are associated with several side effects. Therefore, oncology trials include several endpoints, the primary being the overall survival, and the secondary endpoints include the assessment of other outcomes that indicate the quality of life (QoL), tumor-related endpoints, and others. The disadvantages of oncology clinical trials are the cost associated with the recruitment of a greater number of subjects and long-time follow-up of the patients [ 32 ].

Although primary endpoints are considered as most significant in oncological trials, a recent report stressed the importance of surrogate markers in assessing the efficacy of anti-cancer drugs [ 33 ].

The endpoints in oncology clinical trials, their applications, functions, and drawbacks are summarized in Table Table1 1 .

Survival endpoints in oncology clinical trials

The survival endpoint considers the time from randomization to death. This type of follow-up (daily), although difficult to do, will remove bias associated with the investigator’s interpretation. The survival studies require large sample sizes and cross-over therapies act as confounding factors for survival. The survival studies consider patient benefit over drug toxicity.

Apart from the overall survival, oncology clinical trials use alternative ways to assess the efficacy of the drugs by using other endpoints like progression-free survival [ 34 ]. Other endpoints suggested are biomarkers, disease-free survival, objective response rate, time to progression, complete response, partial response, minor response, time to treatment failure, time to next treatment, duration of clinical benefit, objective response rate, complete response, pathological complete response, disease control rate, clinical benefit rate, milestone survival, event-free survival, and QoL [ 35 ].

Endpoints in immunological diseases and infections

Autoimmune diseases are usually chronic conditions that arise due to the immunologic responses against the self. They are usually associated with hyper-reactivity of immune cells towards the host's own cells/tissue and can cause significant morbidity and mortality among affected people.