Celebrating 150 years of Harvard Summer School. Learn about our history.

Why You Should Make a Good Night’s Sleep a Priority

Poor sleep habits and sleep deprivation are serious problems for most high school and college students. This guide offers important tips on how—and why—to improve your sleep hygiene.

The time you spend in high school and college can be both fun and rewarding. At the same time, these can be some of the busiest years of your life.

Balancing all the demands on your time—a full course load, extracurricular activities, and socializing with friends—can be challenging. And if you also work or have family commitments, it can feel like there just aren’t enough hours in the day.

With so many competing priorities, sacrificing sleep may feel like the only way to get everything done.

Despite the sleepiness you might feel the next day, one late night probably won’t have a major impact on your well-being. But regularly short-changing yourself on quality sleep can have serious implications for school, work, and your physical and mental health.

Alternatively, prioritizing a regular sleep schedule can make these years healthier, less stressful, and more successful long-term.

The sleep you need versus the sleep you get

According to the National Sleep Foundation , high school students (ages 14-17) need about eight to 10 hours of sleep each night. For young adults (ages 18 to 25), the range is need between seven and nine hours.

How do you know how much sleep you need within this range?

According to Dr. Edward Pace-Schott, Harvard Summer School and Harvard Medical School faculty member and sleep expert, you can answer that question simply by observing how much you sleep when you don’t need to get up.

“When you’ve been on vacation for two weeks, how are you sleeping during that second week? How long are you sleeping? If you’re sleeping eight or nine hours when you don’t have any reason to get up, then chances are you need that amount or close to that amount of sleep,” says Pace-Schott.

Most students, however, get far less sleep than the recommended amount.

Seventy to 96 percent of college students get less than eight hours of sleep each week night. And over half of college students sleep less than seven hours per night. The numbers are similar for high school students; 73 percent of high school students get between seven and seven and a half hours of sleep .

Of course, many students attempt to catch up on lost sleep by sleeping late on the weekends. Unfortunately, this pattern is neither healthy nor a true long-term solution to sleep deprivation.

And what about those students who say that they function perfectly well on just a couple hours of sleep?

“There are very few individuals who are so-called short sleepers, people who really don’t need more than six hours of sleep. But, there are a lot more people who claim to be short sleepers than there are real short sleepers,” says Pace-Schott.

Consequences of sleep deprivation

The consequences of sleep deprivation are fairly well established but may still be surprising.

For example, did you know that sleep deprivation can create the same level of cognitive impairment as drinking alcohol?

According to the CDC , staying awake for 18 hours can have the same effect as a blood alcohol content (BAC) of 0.05 percent. Staying awake for 24 hours can equate to a BAC of 0.10 percent (higher than the legal limit of 0.08 percent).

And according to research by AAA , drowsy driving causes an average of 328,000 motor vehicle accidents each year in the US. Drivers who sleep less than five hours per night are more than five times as likely to have a crash as drivers who sleep for seven hours or more.

Other signs of chronic sleep deprivation include:

- Daytime sleepiness and fatigue

- Irritability and short temper

- Mood changes

- Trouble coping with stress

- Difficulty focusing, concentrating, and remembering

Over the long term, chronic sleep deprivation can have a serious impact on your physical and mental health. Insufficient sleep has been linked, for example, to weight gain and obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes.

The impact on your mental health can be just as serious. Harvard Medical School has conducted numerous studies, including research by Pace-Schott, demonstrating a link between sleep deprivation and mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression.

Earn college credits with a summer course at Harvard Summer School.

Importance of sleep for high school and college students

As difficult as it is to prioritize sleep, the advantages of going to bed early and getting quality sleep every night are very real.

College students who prioritize sleep are likely to see an improvement in their academic performance.

If you are well rested, you will experience less daytime sleepiness and fatigue. You may need less caffeine to stay awake during those long lectures. And you will also find you are more productive, more attentive to detail, and able to concentrate better while studying.

But the connection between sleep and academic performance goes well beyond concentration and attentiveness.

“Sleep is very important for consolidating memories. In any sort of experimental setting, study results show better performance if you learn material and then sleep on it, instead of remaining awake. So there’s lots and lots of evidence now indicating that sleep promotes memory strengthening and memory consolidation,” says Pace-Schott.

There is also a strong connection between sleep quality and stress.

Students who prioritize sleep are better able to cope with the stress that comes with being an active student.

“It’s a vicious circle where the more stressed you get, the less you sleep, and the less you sleep, the more stressed you get. And in the long term, that can lead to serious psychiatric problems,” says Pace-Schott.

In the worst case scenario, the combination of lack of sleep and stress can lead to mental health disorders such as depression, general anxiety disorder, and potentially even post-traumatic stress disorder.

But prioritizing sleep can create a positive feedback loop as well.

Establishing a sleep schedule and adequate sleep duration can improve your ability to cope with stress. Being active and productive will help you get more done throughout the day, which also reduces feelings of stress.

And the less stressed you feel during the day, the better you will sleep at night.

Tips for getting more sleep as a student

The key to getting a good night’s sleep is establishing healthy sleep habits, also known as sleep hygiene.

The first step is deciding to make sleep a priority.

Staying ahead of coursework and avoiding distractions and procrastination while you study is key to avoiding the need for late night study sessions. And prioritizing sleep may mean leaving a party early or choosing your social engagements carefully.

Yet the reward—feeling awake and alert the next morning—will reinforce that positive choice.

The next step is establishing healthy bedtime and daytime patterns to promote good quality sleep.

Pace-Schott offers the following tips on steps you can take to create healthy sleep hygiene:

- Limit caffeine in close proximity to bed time. College students should also avoid alcohol intake, which disrupts quality sleep.

- Avoid electronic screens (phone, laptop, tablet, desktop) within an hour of bedtime.

- Engage in daily physical exercise, but avoid intense exercise within two hours of bedtime.

- Establish a sleep schedule. Be as consistent as possible in your bedtime and rise time, and get exposure to morning sunlight.

- Establish a “wind-down” routine prior to bedtime.

- Limit use of bed for daily activities other than sleep (e.g., TV, work, eating)

Of course, college students living in dorms or other communal settings may find their sleep disturbed by circumstances beyond their control: a poor-quality mattress, inability to control the temperature of your bedroom, or noisy roommates, for example.

But taking these active steps to promote healthy sleep will, barring these other uncontrollable circumstances, help you fall asleep faster, stay asleep, and get a more restorative sleep.

And for students who are still not convinced of the importance of sleep, Pace-Schott says that personal observation is the best way to see the impact of healthy sleep habits.

“Keep a sleep diary for a week. Pay attention to your sleep in a structured way. And be sure to record how you felt during the day. This can really help you make the link between how you slept the night before and how you feel during the day. It’s amazing how much you will learn about your sleep and its impact on your life.”

Interested in summer at Harvard? Learn more about our summer programs.

Request Information

What You Need to Know About Pre-College Program Activities

Rigorous, fast-paced—and a lot of fun.

Harvard Division of Continuing Education

The Division of Continuing Education (DCE) at Harvard University is dedicated to bringing rigorous academics and innovative teaching capabilities to those seeking to improve their lives through education. We make Harvard education accessible to lifelong learners from high school to retirement.

Contact | Patient Info | Foundation | AASM Engage JOIN Today Login with CSICloud

- AASM Scoring Manual

- Artificial Intelligence

- COVID-19 Resources

- EHR Integration

- Emerging Technology

- Patient Information

- Practice Promotion Resources

- Provider Fact Sheets

- #SleepTechnology

- Telemedicine

- Annual Meeting

- Career Center

- Case Study of the Month

- Change Agents Submission Winners

- Compensation Survey

- Conference Support

- Continuing Medical Education (CME)

- Maintenance of Certification (MOC)

- State Sleep Societies

- Talking Sleep Podcast

- Young Investigators Research Forum (YIRF)

- Leadership Election

- Board Nomination Process

- Membership Directory

- Volunteer Opportunities

- International Assembly

- Accreditation News

- Accreditation Verification

- Program Changes

AASM accreditation demonstrates a sleep medicine provider’s commitment to high quality, patient-centered care through adherence to these standards.

- AASM Social Media Ambassador

- Advertising

- Affiliated Sites

- Autoscoring Certification

- Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

- Event Code of Conduct Policy

- Guiding Principles for Industry Support

- CMSS Financial Disclosure

- IEP Sponsors

- Industry Programs

- Newsletters

- Patient Advocacy Roundtable

- President’s Report

- Social Media

- Strategic Plan

- Working at AASM

- Practice Standards

- Coding and Reimbursement

- Choose Sleep

- Advanced Practice Registered Nurses and Physician Assistants (APRN PA)

- Accredited Sleep Technologist Education Program (A-STEP)

- Inter-scorer Reliability (ISR)

- Coding Education Program (A-CEP)

- Individual Member – Benefits

- Individual Member – Categories

- Members-Only Resources

- Apply for AASM Fellow

- Individual Member – FAQs

- Facility Member – Benefits

- Facility Member – FAQs

- Sleep Team Assemblies

- Types of Accreditation

- Choose AASM Accreditation

- Special Application Types

- Apply or Renew

College students: getting enough sleep is vital to academic success

WESTCHESTER , Ill. — With the semester drawing to a close, millions of college students are preparing to take their final exams. Unfortunately, research is increasingly showing that more and more students are not getting enough sleep, which can have a negative impact on their grades. Among the reasons for these changes in sleeping patterns are increased part-time working hours, pulling all-nighters to finish a paper or cram for an exam, and watching television at bedtime. According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM), the best way to maximize performance on final exams is to both study and get a good night of sleep.

Lawrence Epstein, MD, medical director of Sleep Health Centers in Brighton, Mass., an instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, a past president of the AASM and a member of the AASM board of directors, says that sleep deprivation effects not only whether a student can stay awake in class but how they perform as well.

“Recent studies have shown that adequate sleep is essential to feeling awake and alert, maintaining good health and working at peak performance,” says Dr. Epstein. “After two weeks of sleeping six hours or less a night, students feel as bad and perform as poorly as someone who has gone without sleep for 48 hours. New research also highlights the importance of sleep in learning and memory. Students getting adequate amounts of sleep performed better on memory and motor tasks than did students deprived of sleep.”

Clete A. Kushida, MD, PhD, associate professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University Medical Center, an attending physician at the Stanford Sleep Disorders Clinic, director of the Stanford University Center for Human Sleep Research and a member of the AASM board of directors, notes that the degree of daytime alertness is arguably the most sensitive measure as to how much sleep is necessary for the specific individual.

“If the individual is routinely tired or sleepy during the daytime, odds are that he or she is not getting enough sleep,” says Dr. Kushida. “To take it one step further, there are two primary factors that affect the degree of daytime alertness: sleep quantity and sleep quality. For the student-age population, sleep quantity and quality issues are both important. However, key factors affecting sleep quality, such as the major sleep disorders (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea and restless legs syndrome), are less prevalent in this age group compared to middle-aged or older individuals.”

Dr. Kushida adds that the importance of obtaining adequate sleep in the student-age population cannot be overemphasized.

“There are data that sleep loss leads to learning and memory impairment, as well as decreased attention and vigilance,” says Dr. Kushida. “In the student-age population, studies have found that factors such as self-reported shortened sleep time, erratic sleep/wake schedules, late bed and rise times, and poor sleep quality have been found to be negatively associated with school performance for adolescents from middle school through college. Thus, there is ample evidence to indicate that the lack of adequate nighttime sleep can lead to disturbances in brain function, which in turn, can lead to poor academic performance.”

Other recent studies outline the adverse effects of poor sleep among students with regards to their success in school:

- Sleepiness and poor sleep quality are prevalent among university students, affecting their academic performance and daytime functioning.

- Students with symptoms of sleep disorders are more likely to receive poor grades in classes such as math, reading and writing than peers without symptoms of sleep disorders.

- College students with insomnia have significantly more mental health problems than college students without insomnia.

- College students with medical-related majors are more likely to have poorer quality of sleep in comparison to those with a humanities major.

- College students who pull “all-nighters” are more likely to have a lower GPA.

- Students who stay up late on school nights and make up for it by sleeping late on weekends are more likely to perform poorly in the classroom. This is because, on weekends, they are waking up at a time that is later than their internal body clock expects. The fact that their clock must get used to a new routine may affect their ability to be awake early for school at the beginning of the week when they revert back to their new routine.

The following tips are provided by the AASM to help students learn how to get enough sleep:

Go to bed early

Students should go to bed early enough to have the opportunity for a full night of sleep. Adults need about seven to eight hours of sleep each night.

Get out of bed

If you have trouble falling asleep, get out of bed and do something relaxing until you feel sleepy.

Stay out of bed

Don’t study, read, watch TV or talk on the phone in bed. Only use your bed for sleep.

If you take a nap, then keep it brief. Nap for less than an hour and before 3 p.m.

Wake up on the weekend

It is best to go to bed and wake up at the same times on the weekend as you do during the schoolweek. If you missed out on a lot of sleep during the week, then you can try to catch up on the weekend. But sleeping in later on Saturdays and Sundays will make it very hard for you to wake up for classes on Monday morning.

Avoid caffeine

Avoid caffeine in the afternoon and at night. It stays in your system for hours and can make it hard for you to fall asleep.

Adjust the lights

Dim the lights in the evening and at night so your body knows it will soon be time to sleep. Let in the sunlight in the morning to boost your alertness.

Take some time to “wind down” before going to bed. Get away from the computer, turn off the TV and the cell phone, and relax quietly for 15 to 30 minutes.

Eat a little

Never eat a large meal right before bedtime. Enjoy a healthy snack or light dessert so you don’t go to bed hungry.

Those who believe they have a sleep disorder should consult with their primary care physician or a sleep specialist.

Sleep Education , a patient education website created by the AASM, provides information about various sleep disorders, the forms of treatment available, recent news on the topic of sleep, sleep studies that have been conducted and a listing of sleep facilities.

AASM is a professional membership organization dedicated to the advancement of sleep medicine and sleep-related research.

To arrange an interview with an AASM spokesperson, please contact [email protected] .

Updated Nov. 6, 2017

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Related posts.

American Academy of Sleep Medicine announces 2024 award recipients

New paper examines potential power and pitfalls of harnessing artificial intelligence for sleep medicine

AASM announces 2024 High School Video Contest winners

Embracing the eclipse: Shedding light on the importance of light for our sleep and daily routines

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 01 October 2019

Sleep quality, duration, and consistency are associated with better academic performance in college students

- Kana Okano 1 ,

- Jakub R. Kaczmarzyk 1 ,

- Neha Dave 2 ,

- John D. E. Gabrieli 1 &

- Jeffrey C. Grossman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1281-2359 3

npj Science of Learning volume 4 , Article number: 16 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

437k Accesses

121 Citations

1715 Altmetric

Metrics details

Although numerous survey studies have reported connections between sleep and cognitive function, there remains a lack of quantitative data using objective measures to directly assess the association between sleep and academic performance. In this study, wearable activity trackers were distributed to 100 students in an introductory college chemistry class (88 of whom completed the study), allowing for multiple sleep measures to be correlated with in-class performance on quizzes and midterm examinations. Overall, better quality, longer duration, and greater consistency of sleep correlated with better grades. However, there was no relation between sleep measures on the single night before a test and test performance; instead, sleep duration and quality for the month and the week before a test correlated with better grades. Sleep measures accounted for nearly 25% of the variance in academic performance. These findings provide quantitative, objective evidence that better quality, longer duration, and greater consistency of sleep are strongly associated with better academic performance in college. Gender differences are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

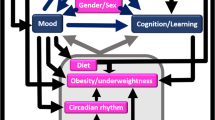

Effect of sleep and mood on academic performance—at interface of physiology, psychology, and education

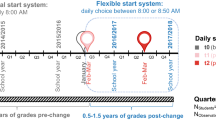

A 4-year longitudinal study investigating the relationship between flexible school starts and grades

Macro and micro sleep architecture and cognitive performance in older adults

Introduction.

The relationship between sleep and cognitive function has been a topic of interest for over a century. Well-controlled sleep studies conducted with healthy adults have shown that better sleep is associated with a myriad of superior cognitive functions, 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 including better learning and memory. 7 , 8 These effects have been found to extend beyond the laboratory setting such that self-reported sleep measures from students in the comfort of their own homes have also been found to be associated with academic performance. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13

Sleep is thought to play a crucial and specific role in memory consolidation. Although the exact mechanisms behind the relationship between sleep, memory, and neuro-plasticity are yet unknown, the general understanding is that specific synaptic connections that were active during awake-periods are strengthened during sleep, allowing for the consolidation of memory, and synaptic connections that were inactive are weakened. 5 , 14 , 15 Thus, sleep provides an essential function for memory consolidation (allowing us to remember what has been studied), which in turn is critical for successful academic performance.

Beyond the effects of sleep on memory consolidation, lack of sleep has been linked to poor attention and cognition. Well-controlled sleep deprivation studies have shown that lack of sleep not only increases fatigue and sleepiness but also worsens cognitive performance. 2 , 3 , 16 , 17 In fact, the cognitive performance of an individual who has been awake for 17 h is equivalent to that exhibited by one who has a blood alcohol concentration of 0.05%. 1 Outside of a laboratory setting, studies examining sleep in the comfort of peoples’ own homes via self-report surveys have found that persistently poor sleepers experience significantly more daytime difficulties in regards to fatigue, sleepiness, and poor cognition compared with persistently good sleepers. 18

Generally, sleep is associated with academic performance in school. Sleep deficit has been associated with lack of concentration and attention during class. 19 While a few studies report null effects, 20 , 21 most studies looking at the effects of sleep quality and duration on academic performance have linked longer and better-quality sleep with better academic performance such as school grades and study effort. 4 , 6 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 Similarly, sleep inconsistency plays a part in academic performance. Sleep inconsistency (sometimes called “social jet lag”) is defined by inconsistency in sleep schedule and/or duration from day to day. It is typically seen in the form of sleep debt during weekdays followed by oversleep on weekends. Sleep inconsistency tends to be greatest in adolescents and young adults who stay up late but are constrained by strict morning schedules. Adolescents who experience greater sleep inconsistency perform worse in school. 28 , 29 , 30 , 31

Although numerous studies have investigated the relationship between sleep and students’ academic performance, these studies utilized subjective measures of sleep duration and/or quality, typically in the form of self-report surveys; very few to date have used objective measures to quantify sleep duration and quality in students. One exception is a pair of linked studies that examined short-term benefits of sleep on academic performance in college. Students were incentivized with offers of extra credit if they averaged eight or more hours of sleep during final exams week in a psychology class 32 or five days leading up to the completion of a graphics studio final assignment. 33 Students who averaged eight or more hours of sleep, as measured by a wearable activity tracker, performed significantly better on their final psychology exams than students who chose not to participate or who slept less than eight hours. In contrast, for the graphics studio final assignments no difference was found in performance between students who averaged eight or more hours of sleep and those who did not get as much sleep, although sleep consistency in that case was found to be a factor.

Our aim in this study was to explore how sleep affects university students’ academic performance by objectively and ecologically tracking their sleep throughout an entire semester using Fitbit—a wearable activity tracker. Fitbit uses a combination of the wearer’s movement and heart-rate patterns to estimate the duration and quality of sleep. For instance, to determine sleep duration, the device measures the time in which the wearer has not moved, in combination with signature sleep movements such as rolling over. To determine sleep quality, the Fitbit device measures the wearer’s heart-rate variability which fluctuates during transitions between different stages of sleep. Although the specific algorithms that calculate these values are proprietary to Fitbit, they have been found to accurately estimate sleep duration and quality in normal adult sleepers without the use of research-grade sleep staging equipment. 34 By collecting quantitative sleep data over the course of the semester on nearly 100 students, we aimed to relate objective measures of sleep duration, quality, and consistency to academic performance from test to test and overall in the context of a real, large university college course.

A secondary aim was to understand gender differences in sleep and academic performance. Women outperform men in collegiate academic performance in most subjects 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 and even in online college courses. 39 Most of the research conducted to understand this female advantage in school grades has examined gender differences in self-discipline, 40 , 41 , 42 and none to date have considered gender differences in sleep as a mediating factor on school grades. There are inconsistencies in the literature on gender differences in sleep in young adults. While some studies report that females get more quantity 43 but worse quality sleep compared with males, 43 , 44 other studies report that females get better quality sleep. 45 , 46 In the current study, we aim to see whether we would observe a female advantage in grades and clarify how sleep contributes to gender differences.

Bedtime and wake-up times

On average, students went to bed at 1:54 a.m. (Median = 1:47 a.m., Standard Deviation (SD) of all bedtime samples = 2 h 11 min, SD of mean bedtime per participant = 1 h) and woke up at 9:17 a.m. (Median = 9:12 a.m., SD of all wake-up time samples = 2 h 2 min; SD of mean wake-up time per participant = 54 min). The data were confirmed to have Gaussian distribution using the Shapiro–Wilks normality test. We conducted an ANOVA with the overall score (sum of all grade-relevant quizzes and exams—see “Procedure”) as the dependent variable and bedtime (before or after median) and wake-up time (before or after median) as the independent variables. We found a main effect of bedtime ( F (1, 82) = 6.45, p = 0.01), such that participants who went to bed before median bedtime had significantly higher overall score ( X = 77.25%, SD = 13.71%) compared with participants who went to bed after median bedtime ( X = 70.68%, SD = 11.01%). We also found a main effect of wake-up time ( F (1, 82) = 6.43, p = 0.01), such that participants who woke up before median wake-up time had significantly higher overall score ( X = 78.28%, SD = 9.33%) compared with participants who woke up after median wake-up time ( X = 69.63%, SD = 14.38%), but found no interaction between bedtime and wake-up time ( F (1, 82) = 0.66, p = 0.42).

A Pearson’s product-moment correlation between average bedtime and overall score revealed a significant and negative correlation ( r (86) = −0.45, p < 0.0001), such that earlier average bedtime was associated with a higher overall score. There was a significant and negative correlation between average wake-up time and overall score ( r (86) = −0.35, p < 0.001), such that earlier average wake-up time was associated with a higher overall score. There was also a significant and positive correlation between average bedtime and average wake-up time (r (86) = 0.68, p < 0.0001), such that students who went to bed earlier tended to also wake up earlier.

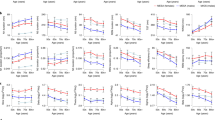

Sleep duration, quality, and consistency in relation to academic performance

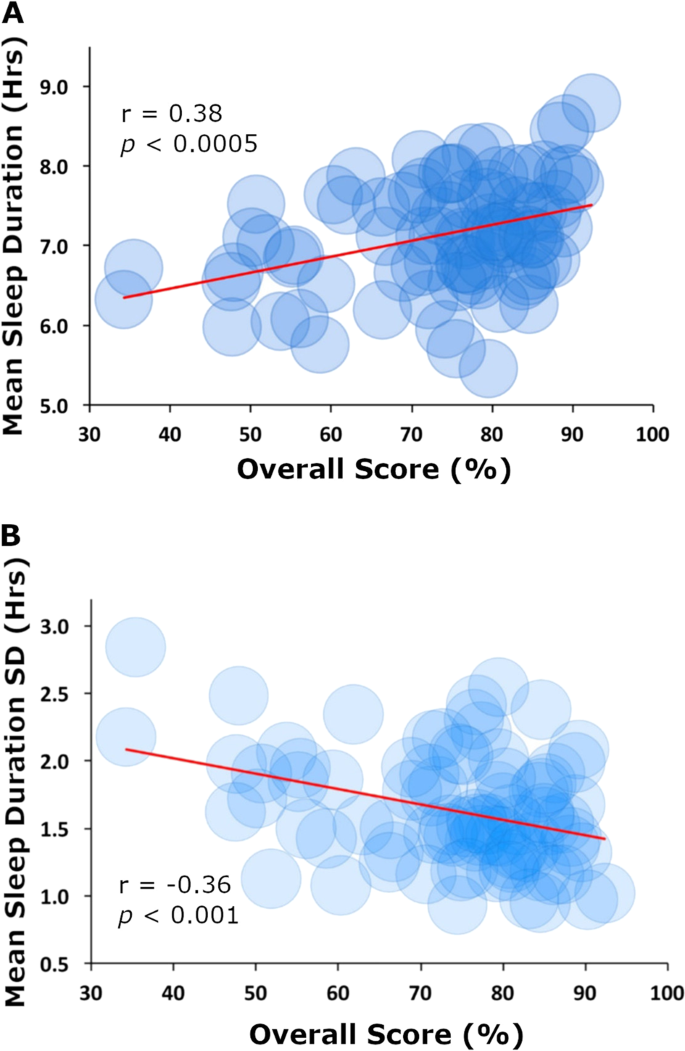

Overall, the mean duration of sleep for participants throughout the entire semester was 7 h 8 min (SD of all sleep samples = 1 h 48 min, SD of mean sleep duration per participant = 41 min). There was a significant positive correlation between mean sleep duration throughout the semester (sleep duration) and overall score ( r (86) = 0.38, p < 0.0005), indicating that a greater amount of sleep was associated with a higher overall score (Fig. 1a ). Similarly, there was a significant positive correlation between mean sleep quality throughout the semester (Sleep Quality) and Overall Score ( r (86) = 0.44, p < 0.00005). Sleep inconsistency was defined for each participant as the standard deviation of the participant’s daily sleep duration in minutes so that a larger standard deviation indicated greater sleep inconsistency. There was a significant negative correlation between sleep inconsistency and overall score ( r (86) = −0.36, p < 0.001), indicating that the greater inconsistency in sleep duration was associated with a lower overall score (Fig. 1b ).

Correlations between sleep measures and overall score. a Average daily hours slept (sleep duration) vs. overall score for the semester. b Standard deviation of average daily hours of sleep (sleep inconsistency) vs. overall score in class

Timing of sleep and its relation to academic performance

To understand sleep and its potential role in memory consolidation, we examined the timing of sleep as it related to specific assessments. All Pearson correlations with three or more comparisons were corrected for multiple comparisons using false discovery rate. 47

Night before assessments

We conducted a correlation between sleep quality the night before a midterm and respective midterm scores as well as sleep duration the night before a midterm and respective scores. There were no significant correlations with sleep duration or sleep quality for all three midterms (all r s < 0.20, all p s > 0.05). Similar analyses for sleep duration and sleep quality the night before respective quizzes revealed no correlations ( r s from 0.01 to 0.26, all p s > 0.05).

Week and month leading up to assessments

To understand the effect of sleep across the time period while course content was learned for an assessment, we examined average sleep measures during the 1 month leading up to the midterms. We found a significant positive correlation between average sleep duration over the month leading up to scores on each midterm ( r s from 0.25 to 0.34, all p s < 0.02). Similar analyses for average sleep duration over one week leading up to respective quizzes were largely consistent with those of midterms, with significant correlations on 3 of 8 quizzes (rs from 0.3 to 0.4, all p s < 0.05) and marginal correlations on an additional 3 quizzes (rs from 0.25 to 0.27, all p s < 0.08).

There was a significant and positive correlation between sleep quality scores averaged over the month leading up to each midterm for all three midterms ( r s from 0.21 to 0.38, all p s < 0.05). Similar analyses for average Sleep Quality over one week leading up to respective quizzes revealed a significant correlation on 1 of 8 quizzes ( r (86) = 0.42, p < 0.005) and marginal correlations on 3 quizzes ( r s from 0.25 to 0.27, all p s < 0.08).

Variance of assessment performance accounted for by sleep measures

In order to calculate how much of the variance on assessment performance was accounted for by the sleep measures, we conducted a stepwise regression on overall score using three regressors: sleep duration, sleep quality, and sleep inconsistency. The relative importance of each variable was calculated using the relaimpo package in R 48 to understand individual regressor’s contribution to the model, which is not always clear from the breakdown of model R 2 when regressors are correlated. We found a significant regression ( F (3,84) = 8.95, p = .00003), with an R 2 of 0.24. Students’ predicted overall score was equal to 77.48 + 0.21 (sleep duration) + 19.59 (Sleep Quality) – 0.45 (sleep inconsistency). While sleep inconsistency was the only significant individual predictor of overall score ( p = 0.03) in this analysis, we found that 24.44% of variance was explained by the three regressors. The relative importance of these metrics were 7.16% sleep duration, 9.68% sleep quality, and 7.6% sleep inconsistency.

Gender differences

Females had better Sleep Quality ( t (88) = 2.63, p = 0.01), and less sleep inconsistency ( t (88) = 2.18, p = 0.03) throughout the semester compared with males, but the two groups experienced no significant difference in sleep duration ( t (88) = 1.03, p = 0.3). Sleep duration and sleep quality were significantly correlated in both males ( r (41) = 0.85, p < 0.00001) and females ( r (43) = 0.64, p < 0.00001), but this correlation was stronger in males ( Z = −2.25, p = 0.02) suggesting that it may be more important for males to get a long-duration sleep in order to get good quality sleep. In addition, sleep inconsistency and sleep quality were significantly negatively correlated in males ( r (41) = −0.51, p = 0.0005) but not in females ( r (43) = 0.29, p > 0.05), suggesting that it may be more important for males to stick to a regular daily sleep schedule in order to get good quality sleep.

Females scored higher on overall score compared with males ( t (88) = −2.48, p = 0.01), but a one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) revealed that females and males did not perform significantly different on overall score when controlling for Sleep Quality, F (1, 85) = 2.22, p = 0.14. Sleep inconsistency and overall score were negatively correlated in males ( r (41) = −0.44, p = 0.003) but not in females ( r (43) = −0.13, p = 0.39), suggesting that it is important for males to stick to a regular sleep schedule in order to perform well in academic performance but less so for females. No other gender differences were detected between other sleep measures and overall score.

This study found that longer sleep duration, better sleep quality, and greater sleep consistency were associated with better academic performance. A multiple linear regression revealed that these three sleep measures accounted for 24.44% of the variance in overall grade performance. Thus, there was a substantial association between sleep and academic performance. The present results correlating overall sleep quality and duration with academic performance are well aligned with previous studies 6 , 11 , 12 , 24 , 25 on the role of sleep on cognitive performance. Similarly, this study compliments the two linked studies that found longer sleep duration during the week before final exams 47 and consistent sleep duration five days prior to a final assignment 48 enhanced students’ performance. The present study, however, significantly extends our understanding of the relation between sleep and academic performance by use of multiple objective measures of sleep throughout an entire semester and academic assessments completed along the way.

The present study also provides new insights about the timing of the relation between sleep and academic performance. Unlike a prior study, 23 we did not find that sleep duration the night before an exam was associated with better test performance. Instead we found that both longer sleep duration and better sleep quality over the full month before a midterm were more associated with better test performance. Rather than the night before a quiz or exam, it may be more important to sleep well for the duration of the time when the topics tested were taught. The implications of these findings are that, at least in the context of an academic assessment, the role of sleep is crucial during the time the content itself is learned, and simply getting good sleep the night before may not be as helpful. The outcome that better “content-relevant sleep” leads to improved performance is supported by previous controlled studies on the role of sleep in memory consolidation. 14 , 15

Consistent with some previous research 45 , 46 female students tended to experience better quality sleep and with more consistency than male students. In addition, we found that males required a longer and more regular daily sleep schedule in order to get good quality sleep. This female advantage in academic performance was eliminated once sleep patterns were statistically equated, suggesting that it may be especially important to encourage better sleep habits in male students (although such habits may be helpful for all students).

Several limitations of the present study may be noted. First, the sleep quality measures were made with proprietary algorithms. There is an evidence that the use of cardiac, respiratory, and movement information from Fitbit devices can accurately estimate sleep stages, 32 but there is no published evidence that Fitbit’s 1~10 sleep quality scores represent a valid assessment of sleep quality. Second, the relation between sleep and academic performance may be moderated by factors that can affect sleep, such as stress, anxiety, motivation, personality traits, and gender roles. Establishing a causal relation between sleep and academic performance will require experimental manipulations in randomized controlled trials, but these will be challenging to conduct in the context of real education in which students care about their grades. Third, these findings occurred for a particular student population at MIT enrolled in a particular course, and future studies will need to examine the generalizability of these findings to other types of student populations and other kinds of classes.

In sum, this study provides evidence for a strong relation between sleep and academic performance using a quantifiable and objective measures of sleep quality, duration, and consistency in the ecological context of a live classroom. Sleep quality, duration, and consistency together accounted for a substantial amount (about a quarter) of the overall variance in academic performance.

Participants

One hundred volunteers (47 females) were selected from a subset of students who volunteered among 370 students enrolled in Introduction to Solid State Chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to participate in the study. Participants were informed of the study and gave written consent obtained in accordance with the guidelines of and approved by the MIT Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects. Due to limitations in funding, we only had access to 100 Fitbit devices and could not enroll all students who volunteered; consequently, the first 100 participants to volunteer were selected. All participants were gifted a wearable activity tracker at the completion of the study in exchange for their participation. Seven participants were excluded from analysis because they failed to wear their activity tracker for more than 80% of the semester, three participants were excluded because they lost their wearable activity tracker, and another two participants were excluded because they completed less than 75% of the assessments in the class. Of the 88 participants who completed the study (45 females), 85 were freshmen, one was a junior and two were seniors (mean age = 18.19 years).

The Solid State Chemistry class is a single-semester class offered in the fall semester and geared toward freshmen students to satisfy MIT’s general chemistry requirement. The class consisted of weekly lectures by the professor and two weekly recitations led by 12 different teaching assistants (TAs). Each student was assigned to a specific recitation section that fit their schedule and was not allowed to attend other sections; therefore, each student had the same TA throughout the semester. Students took (1) weekly quizzes that tested knowledge on the content covered the week leading up to the quiz date, (2) three midterms that tested knowledge on the content covered in the 3–4 weeks leading up to the exam date, and (3) a final exam that tested content covered throughout the semester. Based on a one-way between subjects’ analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the effect of teaching assistants (TAs) on overall grade, we found no significant differences in overall grade across the TAs (F (10, 77) = 1.82, p = 0.07. (One TA was removed from the analysis because he only had one student who was participating in this study).

Participants were asked to wear an activity tracker for the entire duration of the semester without going below 80% usage each week. If 80% or more usage was not maintained, warning emails were sent at the end of that respective week. Participants were asked to return the device if they dipped below 80% usage more than three out of the 14 weeks of the semester. The average usage rate at the end of the semester for the 88 participants who completed the study was 89.4% (SD = 5.5%). The missing data appeared to be at random and were deleted prior to data analysis. As part of a separate research question, 22 of the 88 participants joined an intense cardiovascular exercise class for which they received separate physical education credit. These students performed similarly to the other 67 participants in terms of final class grade ( t (88) = 1.57, p = 0.12), exercise amount (total amount of moderately and very active minutes on the wearable device) (t (88) = 0.59, p = 0.56), sleep amount ( t (88) = 0.3, p = 0.77), and sleep quality ( t (88) = 0.14, p = 0.9), so they were included in all of the analyses.

Participants’ activities were tracked using a Fitbit Charge HR. Data from the device were recorded as follows: heart rate every 5 min; steps taken, distance traveled, floors climbed, calories burned and activity level measurements every 15 min; resting heart rate daily; and sleep duration and quality for every instance of sleep throughout the day. Sleep quality was determined using Fitbit’s proprietary algorithm that produces a value from 0 (poor quality) to 10 (good quality).

Assessments

Nine quizzes, three midterm examinations, and one final examination were administered throughout the 14-week class to assess the students’ academic achievement. The students’ cumulative class grade was made up of 25% for all nine quizzes (lowest quiz grade was dropped from the average), 15% for each midterm exam, and 30% for the final exam for a total of 100%.

At MIT, freshmen are graded on a Pass or No Record basis in all classes taken during their first semester. Therefore, all freshmen in this class needed a C- level or better (≥50%, no grading on a curve) to pass the class. A failing grade (a D or F grade) did not go on their academic record. All upperclassmen were given letter grades; A (≥85%), B (70–84%), C (50–69%), D (45–49%), F (≤44%). Because a large portion of the class had already effectively “passed” the class before taking Quiz 9 and the final exam, we excluded these two assessments from our analyses due to concerns about students’ motivation to perform their best. We calculated for each student an overall score defined as the sum of the eight quizzes and three midterms to summarize academic performance in the course.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

No custom codes were used in the analysis of this study

Dawson, D. & Reid, K. Fatigue, alcohol and performance impairment. Nature 388 , 540–545 (1997).

Article Google Scholar

Lim, J. & Dinges, D. F. A meta-analysis of the impact of short-term sleep deprivation on cognitive variables. Psychol. Bull. 136 , 375–389 (2010).

Harrison, Y. & Horne, J. A. The impact of sleep deprivation on decision making: a review. J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 6 , 236–249 (2000).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Wagner, U., Gais, S., Haider, H., Verleger, R. & Born, J. Sleep inspires insight. Nature 427 , 352–355 (2004).

Walker, M. P. & Stickgold, R. Sleep, memory, and plasticity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 57 , 139–166 (2006).

Wong, M. L. et al. The interplay between sleep and mood in predicting academic functioning, physical health and psychological health: a longitudinal study. J. Psychosom. Res. 74 , 271–277 (2013).

Diekelmann, S., Wilhelm, I. & Born, J. The whats and whens of sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Sleep. Med. Rev. 13 , 309–321 (2009).

Fogel, S. M., Smith, C. T. & Cote, K. A. Dissociable learning-dependent changes in REM and non-REM sleep in declarative and procedural memory systems. Behav. Brain Res. 180 , 48–61 (2007).

Eliasson, A. H. & Lettieri, C. J. Early to bed, early to rise! Sleep habits and academic performance in college students. Sleep. Breath. 14 , 71–75 (2010).

Gaultney, J. F. The prevalence of sleep disorders in college students: Impact on academic performance. J. Am. Coll. Health 59 , 91–97 (2010).

Gilbert, S. P. & Weaver, C. C. Sleep quality and academic performance in university students: A wake-up call for college psychologists. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 24 , 295–306 (2010).

Gomes, A. A., Tavares, J. & de Azevedo, M. H. P. Sleep and academic performance in undergraduates: A multi-measure, multi-predictor approach. Chronobiol. Int. 28 , 786–801 (2011).

Lemma, S., Berhane, Y., Worku, A., Gelaye, B. & Williams, M. A. Good quality sleep is associated with better academic performance among university students in Ethiopia. Sleep. Breath. 18 , 257–263 (2014).

Gilestro, G. F., Tononi, G. & Cirelli, C. Widespread changes in synaptic markers as a function of sleep and wakefulness in drosophila. Science 324 , 109–112 (2009).

Rasch, B. & Born, J. About sleep’s role in memory. Physiol. Rev. 93 , 681–766 (2013).

Alhola, P. & Polo-Kantola, P. Sleep deprivation: Impact on cognitive performance. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 3 , 553–567 (2007).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Durmer, J. S. & Dinges, D. F. Neurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivation. Semin. Neurol. 25 , 117–129 (2005).

Alapin, I. et al. How is good and poor sleep in older adults and college students related to daytime sleepiness, fatigue, and ability to concentrate? J. Psychosom. Res. 49 , 381–390 (2000).

Orzech, K. M., Salafsky, D. B. & Hamilton, L. A. The state of sleep among college students at a large public university. J. Am. Coll. Health 59 , 612–619 (2011).

Eliasson, A., Eliasson, A., King, J., Gould, B. & Eliasson, A. Association of sleep and academic performance. Sleep. Breath. 6 , 45–48 (2002).

Johns, M. W., Dudley, H. A. & Masterton, J. P. The sleep habits, personality and academic performance of medical students. Med. Educ. 10 , 158–162 (1976).

Merikanto, I., Lahti, T., Puusniekka, R. & Partonen, T. Late bedtimes weaken school performance and predispose adolescents to health hazards. Sleep. Med. 14 , 1105–1111 (2013).

Zeek, M. L. et al. Sleep duration and academic performance among student pharmacists. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 79 , 5–12 (2015).

Hartmann, M. E. & Prichard, J. R. Calculating the contribution of sleep problems to undergraduates’ academic success. Sleep. Health 4 , 463–471 (2018).

Mirghani, H. O., Mohammed, O. S., Almurtadha, Y. M. & Ahmed, M. S. Good sleep quality is associated with better academic performance among Sudanese medical students. BMC Res. Notes 8 , 706 (2015).

Onyper, S. V., Thacher, P. V., Gilbert, J. W. & Gradess, S. G. Class start times, Sleep, and academic performance in college: a path analysis. Chronobiol. Int. 29 , 318–335 (2012).

Ming, X. et al. Sleep insufficiency, sleep health problems and performance in high school students. Clin. Med. Insights Circ. Respir. Pulm. Med. 5 , 71–79 (2011).

Lee, Y. J., Park, J., Soohyun, K., Seong-jin, C. & Seog Ju, K. Academic performance among adolescents with behaviorally. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 11 , 61–68 (2015).

Díaz-Morales, J. F. & Escribano, C. Social jetlag, academic achievement and cognitive performance: Understanding gender/sex differences. Chronobiol. Int. 32 , 822–831 (2015).

Raley, H., Naber, J., Cross, S. & Perlow, M. The impact of duration of sleep on academic performance in University students. Madr. J. Nurs. 1 , 11–18 (2016).

Haraszti, R. Á., Ella, K., Gyöngyösi, N., Roenneberg, T. & Káldi, K. Social jetlag negatively correlates with academic performance in undergraduates. Chronobiol. Int. 31 , 603–612 (2014).

Scullin, M. K. The eight hour sleep challenge during final exams week. Teach. Psychol. 46 , 55–63 (2018).

King, E., Mobley, C. & Scullin, M. K. The 8‐hour challenge: incentivizing sleep during end‐of‐term assessments. J. Inter. Des. 44 , 85–99 (2018).

PubMed Google Scholar

Beattie, Z. et al. Estimation of sleep stages using cardiac and accelerometer data from a wrist-worn device. Sleep 40 , A26–A26 (2017).

Clark, M. J. & Grandy, J. Sex differences in the academic performance of scholastic aptitude test takers. ETS Res. Rep. Ser. 2 , 1-27 (1984).

Google Scholar

Kimball, M. M. A new perspective on women’s math achievement. Psychol. Bull. 105 , 198–214 (1989).

Mau, W.-C. & Lynn, R. Gender differences on the scholastic aptitude test, the American college test and college grades. Educ. Psychol. 21 , 133–136 (2001).

Willingham, W. W. & Cole, N. S. Gender and fair assessment . (Mahwah, NJ, US, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1997).

Volchok, E. Differences in the performance of male and female students in partially online courses at a community college. Community Coll . J . Res . Pract . 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2018.1556134 (2018).

Duckworth, A. L. et al. Will not want: self-control rather than motivation explains the female advantage in report card grades. Learn. Individ. Differ. 39 , 13–23 (2015).

Carvalho, R. G. G. Gender differences in academic achievement: The mediating role of personality. Pers. Individ. Differ. 94 , 54–58 (2016).

Duckworth, A. L. & Seligman, M. E. P. Self-discipline gives girls the edge: gender in self-discipline, grades, and achievement test scores. J. Educ. Psychol. 98 , 198–208 (2006).

Tsai, L. L. & Li, S. P. Sleep patterns in college students: Gender and grade differences. J. Psychosom. Res. 56 , 231–237 (2004).

Becker, S. P. et al. Sleep in a large, multi-university sample of college students: sleep problem prevalence, sex differences, and mental health correlates. Sleep Health 4 , 174–181 (2018).

Bixler, E. O. et al. Women sleep objectively better than men and the sleep of young women is more resilient to external stressors: effects of age and menopause. J. Sleep. Res. 18 , 221–228 (2009).

Mallampalli, M. P. & Carter, C. L. Exploring sex and gender differences in sleep health: a Society for Women’s Health Research Report. J. Women’s. Health 23 , 553–562 (2014).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 57 , 289–300 (1995).

Grömping, U. Relative importance for linear regression in R: The package relaimpo. J. Stat. Softw. 17 , 1–27 (2015).

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Horace A. Lubin Fund in the MIT Department of Materials Science and Engineering to J.C.G. and funding from MIT Integrated Learning Initiative to K.O. and J.R.K. The authors are grateful for many useful discussions with Carrie Moore and Matthew Breen at the Department of Athletics, Physical Education, and Recreation at MIT.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

MIT Integrated Learning Initiative, Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, and McGovern Institute for Brain Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, 02139, USA

Kana Okano, Jakub R. Kaczmarzyk & John D. E. Gabrieli

Harvard Business School, Boston, MA, 02163, USA

Department of Materials Science and Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, 02139, USA

Jeffrey C. Grossman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

K.O. and J.C.G. conceived, designed, supervised, and analyzed the project. J.K. and N.D. helped analyze the data. The manuscript was written by K.O., J.D.E.G., and J.C.G.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jeffrey C. Grossman .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Reporting summary, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Okano, K., Kaczmarzyk, J.R., Dave, N. et al. Sleep quality, duration, and consistency are associated with better academic performance in college students. npj Sci. Learn. 4 , 16 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-019-0055-z

Download citation

Received : 20 March 2019

Accepted : 17 July 2019

Published : 01 October 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-019-0055-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Social isolation consequences: lessons from covid-19 pandemic in a context of dynamic lock-down in chile.

- Alessandra Patrono

- Stefano Renzetti

- Roberto G. Lucchini

BMC Public Health (2024)

Time Management Disposition in Learning Motivation and Academic Performance of Lacquer Art Majors in Fujian, China

- Yuxuan Jiang

- Sri Azra Attan

SN Computer Science (2024)

From good sleep to health and to quality of life – a path analysis of determinants of sleep quality of working adults in Abu Dhabi

- Masood Badri

- Mugheer Alkhaili

- Asma Alrashdi

Sleep Science and Practice (2023)

The association between academic performance indicators and lifestyle behaviors among Kuwaiti college students

- Ahmad R. Al-Haifi

- Balqees A. Al-Awadhi

- Hazzaa M. Al-Hazzaa

Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition (2023)

Screen time and sleep among medical students in Germany

- Lukas Liebig

- Antje Bergmann

- Henna Riemenschneider

Scientific Reports (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

clock This article was published more than 1 year ago

The less college students sleep, the worse their grades, study finds

Every lost hour of average nightly sleep at the start of an academic term predicted a 0.07-point drop in a student’s GPA

There are countless reasons to stay up late in college. Here’s one good reason to go to bed.

The less a student sleeps every night, the lower their grade-point average will be, according to a two-year study of the sleep habits of more than 600 college freshmen that was published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Researchers found that every lost hour of average nightly sleep at the start of an academic term was associated with a 0.07-point drop in a student’s end-of-term GPA. When a student slept less than six hours a night, the effect of lost sleep on a student’s grades was even more pronounced, said David Creswell, the lead author of the study and a professor in psychology and neuroscience at Carnegie Mellon University.

“You’re accumulating this sleep debt ,” Creswell said. “And that has a pretty negative role in terms of people’s academics.”

Sleep, especially undisturbed sleep, helps the brain process and retain information it has learned. And when someone is sleep-deprived, attention span and memory also are impaired .

But students have a number of “competing pressures” to stay up late in college, especially in their freshman year, which is often the first time students are living away from home, Creswell said. The average student in the study fell asleep about 2:30 a.m. Barely any of the students went to bed before midnight. And, on average, they slept 6½ hours a night.

Just one hour of extra sleep each night can lead to better eating habits

Sleep recommendations vary

Sleep recommendations shift by age, and the amount of sleep an individual actually needs can vary person to person. In general, for teenagers, the recommendation is eight to 10 hours of sleep. For those 18 to 25 years old, it drops to seven to nine hours.

Creswell said he doesn’t want to “lecture” students about the findings but, according to the research, it appears that getting enough shut-eye does boost a student’s GPA.

“A lot of students say, ‘I should just stay up a lot later and study a lot longer,’ ” Creswell said. “Well, what we’re showing here is that sleep may be your friend, in terms of helping consolidate this information.”

Creswell and the team of researchers conducted five studies, recruiting college freshmen taking courses in a range of majors at Carnegie Mellon, the University of Notre Dame and the University of Washington. To monitor sleep, the students wore either a Fitbit Flex or a Fitbit HR for the entire academic term, a spring semester or a winter quarter, depending on the school, Creswell said.

Creswell said they avoided studying students’ sleep habits around final exams and term papers because they assumed that the average student’s sleep would just continue to drop off.

“We really wanted to look at this critical period in the semester where you’re starting to establish sleep patterns,” Creswell said. “Because once you start to hit midterm and finals period, you’re sort of too late in the game for actually doing effective intervention.”

After controlling for other factors — such as whether a student takes naps, their number of class credits and their GPA the previous term — the researchers found that average nightly sleep continued to predict a student’s end-of-term GPA. What time a student went to bed and whether their bedtime varied day to day did not seem to play a role, Creswell said.

A similar study of 100 engineering students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology published in 2019 found the same association between a student’s grades and the amount of sleep they were getting. That study also showed it was tough to make up for bad sleep habits. There was no improvement in scores among students who made sure to get a good night’s sleep right before a big test.

Insufficient sleep may create ‘sleep debt’

It’s not clear why less sleep would cause someone to have a lower GPA, Creswell said. Sleeping for longer, uninterrupted periods of time allows for REM sleep, a period of unconscious rapid eye movement that corresponds with high activity in the brain. Creswell said he suspects a regular pattern of insufficient sleep creates a “sleep debt” over time, leaving students unable to concentrate.

“These college students are going to class with a ton of sleep debt, and they’re having trouble staying focused and learning in college classrooms,” Creswell said. “Those things can really harm your ability to really engage with the material.”

Aric Prather, a psychologist at the University of California at San Francisco, and author of the book, “ The Sleep Prescription ,” said the findings could inform systemic changes at universities, campaigns or workshops to help students have a better night’s sleep.

“There are multiple pathways to get to a GPA, and sleep is like the glue that holds our lives together in lots of domains,” Prather said. “When that whittles away, or is less sticky, bad things happen.”

Grace Pilch, an 18-year-old freshman who lives in a dorm at Pennsylvania State University, said she needs to get at least eight hours of sleep to function in class and during workouts at the gym.

“I can always tell if I didn’t get enough sleep,” Pilch said.

Pilch, who’s majoring in graphic design, said she cares more about getting enough sleep in college than she did in high school because “the classes are expensive,” and she wants to do well. Pilch said she has around a 3.8 GPA so far. And she and her roommate are in bed by 11 p.m. during the week.

“But I do go out with my friends,” Pilch said. “Sleep is important, grades are important, but it’s also important to make connections.”

3 ways to stop waking up frequently during the night and improve sleep

Academic success early on in college has been shown to predict whether students stay in school or drop out years later, and campus programs to address sleep habits could help freshmen during a “critical period” in school, Creswell said.

“We could really teach them, in that first year of college, better sleep patterns that could help them with their academic achievement,” Creswell said.

At the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, 200 students and staff members have enrolled in a seven-week online course on building better sleep habits. Rebecca Huxta, the director of public health and wellness at the university, said that since starting the program, participants have reported an overall decrease in symptoms of insomnia.

Roxanne Prichard, a professor of psychology at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minn., said that she finds students “have been exhausted since puberty,” and they’ve “grown accustomed” to always feeling lethargic.

“Fundamentally, it comes down to: If we’re not sleeping well, all systems are not a go,” Prichard said. “Our body is not prepared for the day ahead of us and what we’re asking it to do if we don’t have that good, basic chunk of nighttime sleep.”

Sign up for the Well+Being newsletter, your source of expert advice and simple tips to help you live well every day

Read more from Well+Being

Well+Being shares news and advice for living well every day. Sign up for our newsletter to get tips directly in your inbox.

Diabetes, air pollution and alcohol consumption could be the biggest risk factors for dementia .

Dairy vs. plant milk : Which is better?

Why is my gas so smelly ? Gender, diet and plane rides can play a role.

Quitting can be a superpower that helps your mental health. Here’s how to quit smarter .

Our relationships with pets can be strong and uncomplicated.

Sleep Deprivation Impacts on College Students Essay

“How sleep deprivation affects psychological variables related to college students’ cognitive performance,” is a Journal of American College Health (J AM COLL HEALTH) written by Pilcher JJ and Walters AS. In this article, the authors attempt to bring out a case study regarding how deprivation of sleep can affect human nature’s cognitive performance by utilizing the psychological variables related to students.

As a matter of fact, it should be noted that the authors hypothesize that sleep deprivation is such a common occurrence amongst most of the college students whose sleeping patterns are comprised of partial deprivation of sleep on certain occasions during the week, as well as, compensation patterns in which the student strive to oversleep during the weekends.

There are three questions that this study attempted to address. The first is, “does sleep loss lead to changes in self-reported levels of psychological variables related to actual performance?” Because tendencies to deprive an individual of sleep often results into increased feelings of sleep and fatigue, the authors of the article expected individuals who are sleep-deprived to record low levels of concentration, estimated performance, effort, and high levels regarding off-task recognitions.

This would be based on the ability to accurately make assessments regarding the psychological variables. Secondly, the study aimed at determining whether sleep deprivation has the power to cause significant alteration in the mood states which may have relations to the performance of an individual. In this regard, this study expected that the participants in the study would record instances of fatigue, tension, confusion, as well as, decreased vigor.

The third question in the study was related to ways of determining how sleep deprivation tend to alter the ability of people to make accurate assessments regarding particular issues, estimated performance, and effort. Various research procedures were carried out in this instance. It was expected that the individual’s decision making processes would change based on the fact that they were deprived of sleep.

This article presents various variables in the case study as demonstrated by the authors. The first is cognitive performance. This refers to a type of operation which utilizes the mental ability of an individual. Second is psychological variables. This refers to the type of variables that are related to the psychological functionality of a person (students).

Self-reports are the third variable that has been utilized by the authors of this article in their study. This refers to the individual records, highlighting the procedural performances from the students, which were taken through the case study project. The last significant variable that has been adequately used by the authors of this article is sleep deprivation.

This refers to a systematic or deliberate, infliction of torture characterized by depriving an individual of enough sleep. The sample population used in this study included 44 college students. The individual participants were expected to complete “Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal.” This was to be done either after 8 hours of sleep or 24 hours of the instance of sleep deprivation.

Upon completion of the cognitive tasks required, the participants were expected to assist in completing two questionnaires. The first was meant to assess self-reported effort, estimated performance and effort. The second was meant to assess off-task cognitions.

The results of the research indicated a poor performance amongst the participants who were sleep-deprived as compared to the ones whose sleep patterns were unaffected in terms of cognitive task performances. However, it was observed that the participants who were sleep-deprived recorded higher rates in their efforts and concentrations compared to the participants who were non-deprived of sleep.

Additional observations also indicated that the estimated performance of sleep-deprived participants was higher compared to the non-deprived participants. As a result, the authors, basically concluded that the college administration of most educational institutions are immensely unaware about the extent of damage that sleep deprivation could have on students’ ability of completion of cognitive tasks.

In terms analysis of this work, the authors of the article have done exceptionally well in terms of collection of the relevant materials that were needed for the successful completion of the study. The layout of the research suggests that the authors thoroughly did their research. Precisely, the demonstration of proper literature and calculation of the figures in the research article suggest that this was well researched and presented.

The use of logical argumentation in terms of description of the methodology also increases the credibility of this research. It is necessary to note that the authors of this article have done extensively well to boost the confidence of the readers by the use of clear facts and figures which are verifiable. As a result, the readers have been given a chance to prove the accuracy of the study.

However, in as much as the approach, display and presentation of this research have been done well, the authors’ research is limited in terms of scope. This research covers only 44 participants from one region. Logically, this is a small population distribution to base conclusions upon. The accuracy of the deductions derived from this study would, therefore, be questioned.

In terms of applicability of the research, this study was helpful in terms of provision of useful information which has boosted the knowledge base in this field of study. This study was mainly targeting the administration of educational institutions.

The authors of the article had the intention of presenting documentary evidence of research that shows that the sleep patterns of the students are relevant and significant in terms of determining the effectiveness and overall performance of the students.

As a result, this research was intended to help in convincing the educational managers and administrators to revise the curriculum and provide a more dynamic one which would ensure that the student gets adequate time for sleep. Also, this research applies to students pursuing different courses in academic institutions in that it provides useful information that can help respective students of different institutions to plan their study schedules.

The information provided in the research would help the students to plan their activities well to ensure that their sense of effectiveness in the study and overall performance are highly maintained. Additional research in this field should involve the use of diverse categories of students to determine the effects that sleep deprivation would have on them.

This would comprise of high school, middle-level College, and university students. Diversity into this line of research would provide more reliable and accurate information.

Works Cited

Pilcher, JJ, and Walters AS. How sleep deprivation affects psychological variables related to college students’ cognitive performance. Journal of American College Health (J AM COLL HEALTH) , 1997 Nov; 46(3): 121-6

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, March 14). Sleep Deprivation Impacts on College Students. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sleep-deprivation-impacts-on-college-students/

"Sleep Deprivation Impacts on College Students." IvyPanda , 14 Mar. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/sleep-deprivation-impacts-on-college-students/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Sleep Deprivation Impacts on College Students'. 14 March.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Sleep Deprivation Impacts on College Students." March 14, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sleep-deprivation-impacts-on-college-students/.

1. IvyPanda . "Sleep Deprivation Impacts on College Students." March 14, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sleep-deprivation-impacts-on-college-students/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Sleep Deprivation Impacts on College Students." March 14, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/sleep-deprivation-impacts-on-college-students/.

- Sleep Deprivation: Biopsychology and Health Psychology

- Sleep Deprivation and Insomnia: Study Sources

- The Issue of Chronic Sleep Deprivation

- Face Recognition and Memory Retention

- Environmental Psychology and Orientation

- Introduction to Clinical Psychology

- Psychological Testing Issues

- Boundary Issue in Professional Psychology

Psychosocial Correlates of Insomnia Among College Students

ORIGINAL RESEARCH — Volume 19 — September 15, 2022

Yves Paul Vincent Mbous, MEng, BSc Hons, BSc 1 ; Mona Nili, PhD, PharmD, MS, MBA 1 ; Rowida Mohamed, MSc, BPharm 1 ; Nilanjana Dwibedi, PhD, MBA, BPharm 1 ( View author affiliations )

Suggested citation for this article: Mbous YPV, Nili M, Mohamed R, Dwibedi N. Psychosocial Correlates of Insomnia Among College Students. Prev Chronic Dis 2022;19:220060. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd19.220060 .

PEER REVIEWED

Introduction

Acknowledgments, author information.

What is already known on this topic?

Despite the well-known prevalence of insomnia among college students, its association with mental health remains a topic of considerable interest, particularly among this vulnerable population constantly adapting to the demands of the academic world.

What is added by this report?

We show that at least a quarter of college students experience insomnia, and we uncover its predominant association with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and depression.

What are the implications for public health practice?

The implications demand a serious consideration of mental health during attempts to improve students’ sleep quality.

Among college students, insomnia remains a topic of research focus, especially as it pertains to its correlates and the extent of its association with mental conditions. This study aimed to shed light on the chief predictors of insomnia among college students.

A cross-sectional survey on a convenience sample of college students (aged ≥18 years) at 2 large midwestern universities was conducted from March 18 through August 23, 2019. All participants were administered validated screening instruments used to screen for insomnia, depression, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Insomnia correlates were identified by using multivariate logistic regression.

Overall, 26.4% of students experienced insomnia; 41.2% and 15.8% had depression and had ADHD symptoms, respectively. Students with depression (adjusted odds ratio, 9.54; 95% CI, 4.50–20.26) and students with ADHD (adjusted odds ratio, 3.48; 95% CI, 1.48–8.19) had significantly higher odds of insomnia. The odds of insomnia were also significantly higher among employed students (odds ratio, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.05–4.18).

This study showed an association between insomnia and mental health conditions among college students. Policy efforts should be directed toward primary and secondary prevention programs that enforce sleep education interventions, particularly among employed college students and those with mental illnesses.

The National Sleep Foundation and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society guidelines recommend 7 to 9 hours of sleep for young adults (1). However, at least 60% of college students have poor quality sleep and garner, on average, 7 hours of sleep per night (2). Previous research showed that up to 75% of college students reported occasional sleep disturbances, while 15% reported overall poor sleep quality (3). In another work, among a sample of 191 undergraduate students, researchers found that 73% of students exhibited some form of sleep problem, with a higher frequency among women than men (4).

Direct consequences of poor sleep among college students include increased tension, irritability, depression, confusion, reduced life satisfaction, or poor academic performance (4). Evidence abounds of the positive correlation between academic failure, low grade point average, negative academic performance, and poor sleep quality patterns (5). As these complications arise early in the life of these students, they might develop into serious ailments as they grow older (high blood pressure, diabetes, stroke) and thereby create an even bigger public health problem. Because insomnia weakens physical and mental functions in addition to academic performances, reduced sleep quality could also lead to mental issues or vice versa (6).