What is an Essay?

10 May, 2020

11 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

Well, beyond a jumble of words usually around 2,000 words or so - what is an essay, exactly? Whether you’re taking English, sociology, history, biology, art, or a speech class, it’s likely you’ll have to write an essay or two. So how is an essay different than a research paper or a review? Let’s find out!

Defining the Term – What is an Essay?

The essay is a written piece that is designed to present an idea, propose an argument, express the emotion or initiate debate. It is a tool that is used to present writer’s ideas in a non-fictional way. Multiple applications of this type of writing go way beyond, providing political manifestos and art criticism as well as personal observations and reflections of the author.

An essay can be as short as 500 words, it can also be 5000 words or more. However, most essays fall somewhere around 1000 to 3000 words ; this word range provides the writer enough space to thoroughly develop an argument and work to convince the reader of the author’s perspective regarding a particular issue. The topics of essays are boundless: they can range from the best form of government to the benefits of eating peppermint leaves daily. As a professional provider of custom writing, our service has helped thousands of customers to turn in essays in various forms and disciplines.

Origins of the Essay

Over the course of more than six centuries essays were used to question assumptions, argue trivial opinions and to initiate global discussions. Let’s have a closer look into historical progress and various applications of this literary phenomenon to find out exactly what it is.

Today’s modern word “essay” can trace its roots back to the French “essayer” which translates closely to mean “to attempt” . This is an apt name for this writing form because the essay’s ultimate purpose is to attempt to convince the audience of something. An essay’s topic can range broadly and include everything from the best of Shakespeare’s plays to the joys of April.

The essay comes in many shapes and sizes; it can focus on a personal experience or a purely academic exploration of a topic. Essays are classified as a subjective writing form because while they include expository elements, they can rely on personal narratives to support the writer’s viewpoint. The essay genre includes a diverse array of academic writings ranging from literary criticism to meditations on the natural world. Most typically, the essay exists as a shorter writing form; essays are rarely the length of a novel. However, several historic examples, such as John Locke’s seminal work “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding” just shows that a well-organized essay can be as long as a novel.

The Essay in Literature

The essay enjoys a long and renowned history in literature. They first began gaining in popularity in the early 16 th century, and their popularity has continued today both with original writers and ghost writers. Many readers prefer this short form in which the writer seems to speak directly to the reader, presenting a particular claim and working to defend it through a variety of means. Not sure if you’ve ever read a great essay? You wouldn’t believe how many pieces of literature are actually nothing less than essays, or evolved into more complex structures from the essay. Check out this list of literary favorites:

- The Book of My Lives by Aleksandar Hemon

- Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

- Against Interpretation by Susan Sontag

- High-Tide in Tucson: Essays from Now and Never by Barbara Kingsolver

- Slouching Toward Bethlehem by Joan Didion

- Naked by David Sedaris

- Walden; or, Life in the Woods by Henry David Thoreau

Pretty much as long as writers have had something to say, they’ve created essays to communicate their viewpoint on pretty much any topic you can think of!

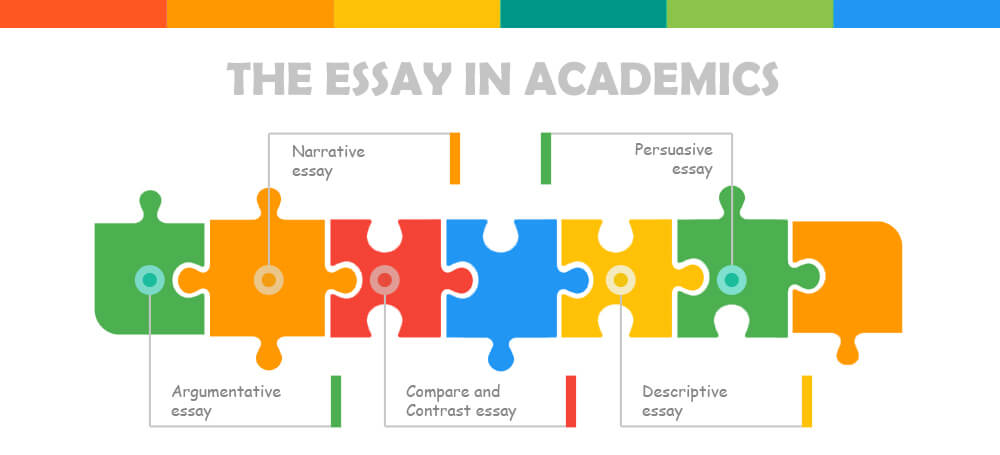

The Essay in Academics

Not only are students required to read a variety of essays during their academic education, but they will likely be required to write several different kinds of essays throughout their scholastic career. Don’t love to write? Then consider working with a ghost essay writer ! While all essays require an introduction, body paragraphs in support of the argumentative thesis statement, and a conclusion, academic essays can take several different formats in the way they approach a topic. Common essays required in high school, college, and post-graduate classes include:

Five paragraph essay

This is the most common type of a formal essay. The type of paper that students are usually exposed to when they first hear about the concept of the essay itself. It follows easy outline structure – an opening introduction paragraph; three body paragraphs to expand the thesis; and conclusion to sum it up.

Argumentative essay

These essays are commonly assigned to explore a controversial issue. The goal is to identify the major positions on either side and work to support the side the writer agrees with while refuting the opposing side’s potential arguments.

Compare and Contrast essay

This essay compares two items, such as two poems, and works to identify similarities and differences, discussing the strength and weaknesses of each. This essay can focus on more than just two items, however. The point of this essay is to reveal new connections the reader may not have considered previously.

Definition essay

This essay has a sole purpose – defining a term or a concept in as much detail as possible. Sounds pretty simple, right? Well, not quite. The most important part of the process is picking up the word. Before zooming it up under the microscope, make sure to choose something roomy so you can define it under multiple angles. The definition essay outline will reflect those angles and scopes.

Descriptive essay

Perhaps the most fun to write, this essay focuses on describing its subject using all five of the senses. The writer aims to fully describe the topic; for example, a descriptive essay could aim to describe the ocean to someone who’s never seen it or the job of a teacher. Descriptive essays rely heavily on detail and the paragraphs can be organized by sense.

Illustration essay

The purpose of this essay is to describe an idea, occasion or a concept with the help of clear and vocal examples. “Illustration” itself is handled in the body paragraphs section. Each of the statements, presented in the essay needs to be supported with several examples. Illustration essay helps the author to connect with his audience by breaking the barriers with real-life examples – clear and indisputable.

Informative Essay

Being one the basic essay types, the informative essay is as easy as it sounds from a technical standpoint. High school is where students usually encounter with informative essay first time. The purpose of this paper is to describe an idea, concept or any other abstract subject with the help of proper research and a generous amount of storytelling.

Narrative essay

This type of essay focuses on describing a certain event or experience, most often chronologically. It could be a historic event or an ordinary day or month in a regular person’s life. Narrative essay proclaims a free approach to writing it, therefore it does not always require conventional attributes, like the outline. The narrative itself typically unfolds through a personal lens, and is thus considered to be a subjective form of writing.

Persuasive essay

The purpose of the persuasive essay is to provide the audience with a 360-view on the concept idea or certain topic – to persuade the reader to adopt a certain viewpoint. The viewpoints can range widely from why visiting the dentist is important to why dogs make the best pets to why blue is the best color. Strong, persuasive language is a defining characteristic of this essay type.

The Essay in Art

Several other artistic mediums have adopted the essay as a means of communicating with their audience. In the visual arts, such as painting or sculpting, the rough sketches of the final product are sometimes deemed essays. Likewise, directors may opt to create a film essay which is similar to a documentary in that it offers a personal reflection on a relevant issue. Finally, photographers often create photographic essays in which they use a series of photographs to tell a story, similar to a narrative or a descriptive essay.

Drawing the line – question answered

“What is an Essay?” is quite a polarizing question. On one hand, it can easily be answered in a couple of words. On the other, it is surely the most profound and self-established type of content there ever was. Going back through the history of the last five-six centuries helps us understand where did it come from and how it is being applied ever since.

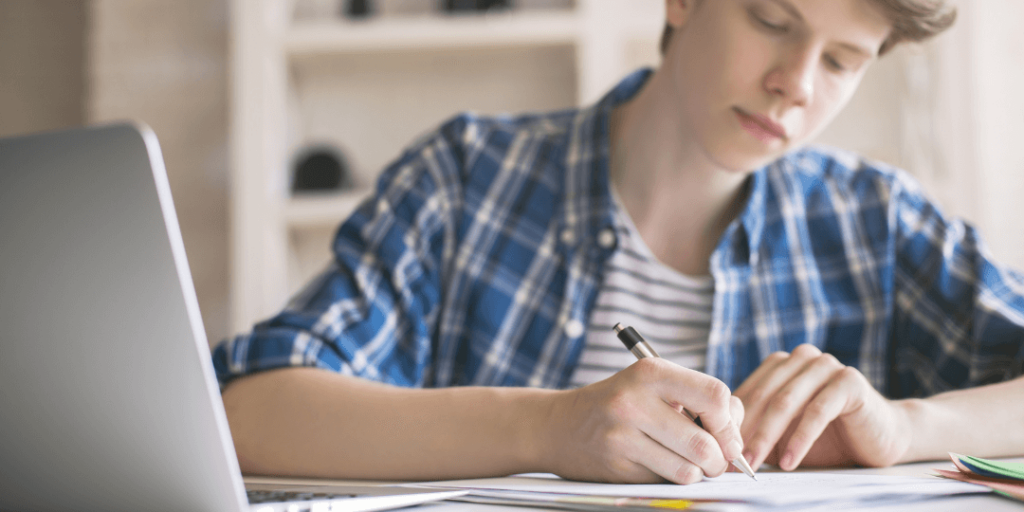

If you must write an essay, follow these five important steps to works towards earning the “A” you want:

- Understand and review the kind of essay you must write

- Brainstorm your argument

- Find research from reliable sources to support your perspective

- Cite all sources parenthetically within the paper and on the Works Cited page

- Follow all grammatical rules

Generally speaking, when you must write any type of essay, start sooner rather than later! Don’t procrastinate – give yourself time to develop your perspective and work on crafting a unique and original approach to the topic. Remember: it’s always a good idea to have another set of eyes (or three) look over your essay before handing in the final draft to your teacher or professor. Don’t trust your fellow classmates? Consider hiring an editor or a ghostwriter to help out!

If you are still unsure on whether you can cope with your task – you are in the right place to get help. HandMadeWriting is the perfect answer to the question “Who can write my essay?”

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

Thesis and Purpose Statements

Use the guidelines below to learn the differences between thesis and purpose statements.

In the first stages of writing, thesis or purpose statements are usually rough or ill-formed and are useful primarily as planning tools.

A thesis statement or purpose statement will emerge as you think and write about a topic. The statement can be restricted or clarified and eventually worked into an introduction.

As you revise your paper, try to phrase your thesis or purpose statement in a precise way so that it matches the content and organization of your paper.

Thesis statements

A thesis statement is a sentence that makes an assertion about a topic and predicts how the topic will be developed. It does not simply announce a topic: it says something about the topic.

Good: X has made a significant impact on the teenage population due to its . . . Bad: In this paper, I will discuss X.

A thesis statement makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of the paper. It summarizes the conclusions that the writer has reached about the topic.

A thesis statement is generally located near the end of the introduction. Sometimes in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or an entire paragraph.

A thesis statement is focused and specific enough to be proven within the boundaries of the paper. Key words (nouns and verbs) should be specific, accurate, and indicative of the range of research, thrust of the argument or analysis, and the organization of supporting information.

Purpose statements

A purpose statement announces the purpose, scope, and direction of the paper. It tells the reader what to expect in a paper and what the specific focus will be.

Common beginnings include:

“This paper examines . . .,” “The aim of this paper is to . . .,” and “The purpose of this essay is to . . .”

A purpose statement makes a promise to the reader about the development of the argument but does not preview the particular conclusions that the writer has drawn.

A purpose statement usually appears toward the end of the introduction. The purpose statement may be expressed in several sentences or even an entire paragraph.

A purpose statement is specific enough to satisfy the requirements of the assignment. Purpose statements are common in research papers in some academic disciplines, while in other disciplines they are considered too blunt or direct. If you are unsure about using a purpose statement, ask your instructor.

This paper will examine the ecological destruction of the Sahel preceding the drought and the causes of this disintegration of the land. The focus will be on the economic, political, and social relationships which brought about the environmental problems in the Sahel.

Sample purpose and thesis statements

The following example combines a purpose statement and a thesis statement (bold).

The goal of this paper is to examine the effects of Chile’s agrarian reform on the lives of rural peasants. The nature of the topic dictates the use of both a chronological and a comparative analysis of peasant lives at various points during the reform period. . . The Chilean reform example provides evidence that land distribution is an essential component of both the improvement of peasant conditions and the development of a democratic society. More extensive and enduring reforms would likely have allowed Chile the opportunity to further expand these horizons.

For more tips about writing thesis statements, take a look at our new handout on Developing a Thesis Statement.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Developing a Thesis Statement

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

Understanding Your Purpose

The first question for any writer should be, "Why am I writing?" "What is my goal or my purpose for writing?" For many writing contexts, your immediate purpose may be to complete an assignment or get a good grade. But the long-range purpose of writing is to communicate to a particular audience. In order to communicate successfully to your audience, understanding your purpose for writing will make you a better writer.

A Definition of Purpose

Purpose is the reason why you are writing . You may write a grocery list in order to remember what you need to buy. You may write a laboratory report in order to carefully describe a chemistry experiment. You may write an argumentative essay in order to persuade someone to change the parking rules on campus. You may write a letter to a friend to express your excitement about her new job.

Notice that selecting the form for your writing (list, report, essay, letter) is one of your choices that helps you achieve your purpose. You also have choices about style, organization, kinds of evidence that help you achieve your purpose

Focusing on your purpose as you begin writing helps you know what form to choose, how to focus and organize your writing, what kinds of evidence to cite, how formal or informal your style should be, and how much you should write.

Types of Purpose

Don Zimmerman, Journalism and Technical Communication Department I look at most scientific and technical writing as being either informational or instructional in purpose. A third category is documentation for legal purposes. Most writing can be organized in one of these three ways. For example, an informational purpose is frequently used to make decisions. Memos, in most circles, carry key information.

When we communicate with other people, we are usually guided by some purpose, goal, or aim. We may want to express our feelings. We may want simply to explore an idea or perhaps entertain or amuse our listeners or readers. We may wish to inform people or explain an idea. We may wish to argue for or against an idea in order to persuade others to believe or act in a certain way. We make special kinds of arguments when we are evaluating or problem solving . Finally, we may wish to mediate or negotiate a solution in a tense or difficult situation.

Remember, however, that often writers combine purposes in a single piece of writing. Thus, we may, in a business report, begin by informing readers of the economic facts before we try to persuade them to take a certain course of action.

In expressive writing, the writer's purpose or goal is to put thoughts and feelings on the page. Expressive writing is personal writing. We are often just writing for ourselves or for close friends. Usually, expressive writing is informal, not intended for outside readers. Journal writing, for example, is usually expressive writing.

However, we may write expressively for other readers when we write poetry (although not all poetry is expressive writing). We may write expressively in a letter, or we may include some expressive sentences in a formal essay intended for other readers.

Entertaining

As a purpose or goal of writing, entertaining is often used with some other purpose--to explain, argue, or inform in a humorous way. Sometimes, however, entertaining others with humor is our main goal. Entertaining may take the form of a brief joke, a newspaper column, a television script or an Internet home page tidbit, but its goal is to relax our reader and share some story of human foibles or surprising actions.

Writing to inform is one of the most common purposes for writing. Most journalistic writing fits this purpose. A journalist uncovers the facts about some incident and then reports those facts, as objectively as possible, to his or her readers. Of course, some bias or point-of-view is always present, but the purpose of informational or reportorial writing is to convey information as accurately and objectively as possible. Other examples of writing to inform include laboratory reports, economic reports, and business reports.

Writing to explain, or expository writing, is the most common of the writing purposes. The writer's purpose is to gather facts and information, combine them with his or her own knowledge and experience, and clarify for some audience who or what something is , how it happened or should happen, and/or why something happened .

Explaining the whos, whats, hows, whys, and wherefores requires that the writer analyze the subject (divide it into its important parts) and show the relationship of those parts. Thus, writing to explain relies heavily on definition, process analysis, cause/effect analysis, and synthesis.

Explaining versus Informing : So how does explaining differ from informing? Explaining goes one step beyond informing or reporting. A reporter merely reports what his or her sources say or the data indicate. An expository writer adds his or her particular understanding, interpretation, or thesis to that information. An expository writer says this is the best or most accurate definition of literacy, or the right way to make lasagne, or the most relevant causes of an accident.

An arguing essay attempts to convince its audience to believe or act in a certain way. Written arguments have several key features:

- A debatable claim or thesis . The issue must have some reasonable arguments on both (or several) sides.

- A focus on one or more of the four types of claims : Claim of fact , claim of cause and effect , claim of value , and/or claim of policy (problem solving).

- A fair representation of opposing arguments combined with arguments against the opposition and for the overall claim.

- An argument based on evidence presented in a reasonable tone . Although appeals to character and to emotion may be used, the primary appeal should be to the reader's logic and reason.

Although the terms argument and persuasion are often used interchangeably, the terms do have slightly different meanings. Argument is a special kind of persuasion that follows certain ground rules. Those rules are that opposing positions will be presented accurately and fairly, and that appeals to logic and reason will be the primary means of persuasion. Persuasive writing may, if it wishes, ignore those rules and try any strategy that might work. Advertisements are a good example of persuasive writing. They usually don't fairly represent the competing product, and they appeal to image, to emotion, to character, or to anything except logic and the facts--unless those facts are in the product's favor.

Writing to evaluate a person, product, thing, or policy is a frequent purpose for writing. An evaluation is really a specific kind of argument: it argues for the merits of the subject and presents evidence to support the claim. A claim of value --the thesis in an evaluation--must be supported by criteria (the appropriate standards of judgment) and supporting evidence (the facts, statistics, examples, or testimonials).

Writers often use a three-column log to set up criteria for their subject, collect relevant evidence, and reach judgments that support an overall claim of value. Writing a three-column log is an excellent way to organize an evaluative essay. First, think about your possible criteria. Remember: criteria are the standards of judgment (the ideal case) against which you will measure your particular subject. Choose criteria which your readers will find valid, fair, and appropriate . Then, collect evidence for each of your selected criteria. Consider the following example of a restaurant evaluation:

Overall claim of value : This Chinese restaurant provides a high quality dining experience.

Problem Solving

Problem solving is a special kind of arguing essay: the writer's purpose is to persuade his audience to adopt a solution to a particular problem. Often called "policy" essays because they recommend the readers adopt a policy to resolve a problem, problem-solving essays have two main components: a description of a serious problem and an argument for specific recommendations that will solve the problem .

The thesis of a problem-solving essay becomes a claim of policy : If the audience follows the suggested recommendations, the problem will be reduced or eliminated. The essay must support the policy claim by persuading readers that the recommendations are feasible, cost-effective, efficient, relevant to the situation, and better than other possible alternative solutions.

Traditional argument , like a debate, is confrontational. The argument often becomes a kind of "war" in which the writer attempts to "defeat" the arguments of the opposition.

Non-traditional kinds of argument use a variety of strategies to reduce the confrontation and threat in order to open up the debate.

- Mediated argument follows a plan used successfully in labor negotiations to bring opposing parties to agreement. The writer of a mediated argument provides a middle position that helps negotiate the differences of the opposing positions.

- Rogerian argumen t also wishes to reduce confrontation by encouraging mutual understanding and working toward common ground and a compromise solution.

- Feminist argument tries to avoid the patriarchal conventions in traditional argument by emphasizing personal communication, exploration, and true understanding.

Combining Purposes

Often, writers use multiple purposes in a single piece of writing. An essay about illiteracy in America may begin by expressing your feelings on the topic. Then it may report the current facts about illiteracy. Finally, it may argue for a solution that might correct some of the social conditions that cause illiteracy. The ultimate purpose of the paper is to argue for the solution, but the writer uses these other purposes along the way.

Similarly, a scientific paper about gene therapy may begin by reporting the current state of gene therapy research. It may then explain how a gene therapy works in a medical situation. Finally, it may argue that we need to increase funding for primary research into gene therapy.

Purposes and Strategies

A purpose is the aim or goal of the writer or the written product; a strategy is a means of achieving that purpose. For example, our purpose may be to explain something, but we may use definitions, examples, descriptions, and analysis in order to make our explanation clearer. A variety of strategies are available for writers to help them find ways to achieve their purpose(s).

Writers often use definition for key terms of ideas in their essays. A formal definition , the basis of most dictionary definitions, has three parts: the term to be defined, the class to which the term belongs, and the features that distinguish this term from other terms in the class.

Look at your own topic. Would definition help you analyze and explain your subject?

Illustration and Example

Examples and illustrations are a basic kind of evidence and support in expository and argumentative writing.

In her essay about anorexia nervosa, student writer Nancie Brosseau uses several examples to develop a paragraph:

Another problem, lying, occurred most often when my parents tried to force me to eat. Because I was at the gym until around eight o'clock every night, I told my mother not to save me dinner. I would come home and make a sandwich and feed it to my dog. I lied to my parents every day about eating lunch at school. For example, I would bring a sack lunch and sell it to someone and use the money to buy diet pills. I always told my parents that I ate my own lunch.

Look at your own topic. What examples and illustrations would help explain your subject?

Classification

Classification is a form of analyzing a subject into types. We might classify automobiles by types: Trucks, Sport Utilities, Sedans, Sport Cars. We can (and do) classify college classes by type: Science, Social Science, Humanities, Business, Agriculture, etc.

Look at your own topic. Would classification help you analyze and explain your subject?

Comparison and Contrast

Comparison and contrast can be used to organize an essay. Consider whether either of the following two outlines would help you organize your comparison essay.

Block Comparison of A and B

- Intro and Thesis

- Description of A

- Description of B (and how B is similar to/different from A)

Alternating Comparison of A and B

- Aspect One: Comparison/contrast of A and B

- Aspect Two: Comparison/contrast of A and B

- Aspect Three: Comparison/contrast of A and B

Look at your own topic. Would comparison/contrast help you organize and explain your subject?

Analysis is simply dividing some whole into its parts. A library has distinct parts: stacks, electronic catalog, reserve desk, government documents section, interlibrary loan desk, etc. If you are writing about a library, you may need to know all the parts that exist in that library.

Look at your own topic. Would analysis of the parts help you understand and explain your subject?

Description

Although we usually think of description as visual, we may also use other senses--hearing, touch, feeling, smell-- in our attempt to describe something for our readers.

Notice how student writer Stephen White uses multiple senses to describe Anasazi Indian ruins at Mesa Verde:

I awoke this morning with a sense of unexplainable anticipation gnawing away at the back of my mind, that this chilly, leaden day at Mesa Verde would bring something new . . . . They are a haunting sight, these broken houses, clustered together down in the gloom of the canyon. The silence is broken only by the rush of the wind in the trees and the trickling of a tiny stream of melting snow springing from ledge to ledge. This small, abandoned village of tiny houses seems almost as the Indians left it, reduced by the passage of nearly a thousand years to piles of rubble through which protrude broken red adobe walls surrounding ghostly jet black openings, undisturbed by modern man.

Look at your own topic. Would description help you explain your subject?

Process Analysis

Process analysis is analyzing the chronological steps in any operation. A recipe contains process analysis. First, sift the flour. Next, mix the eggs, milk, and oil. Then fold in the flour with the eggs, milk and oil. Then add baking soda, salt and spices. Finally, pour the pancake batter onto the griddle.

Look at your own topic. Would process analysis help you analyze and explain your subject?

Narration is possibly the most effective strategy essay writers can use. Readers are quickly caught up in reading any story, no matter how short it is. Writers of exposition and argument should consider where a short narrative might enliven their essay. Typically, this narrative can relate some of your own experiences with the subject of your essay. Look at your own topic. Where might a short narrative help you explain your subject?

Cause/Effect Analysis

In cause and effect analysis, you map out possible causes and effects. Two patterns for doing cause/effect analysis are as follows:

Several causes leading to single effect: Cause 1 + Cause 2 + Cause 3 . . . => Effect

One cause leading to multiple effects: Cause => Effect 1 + Effect 2 + Effect 3 ...

Look at your own topic. Would cause/effect analysis help you understand and explain your subject?

How Audience and Focus Affect Purpose

All readers have expectations. They assume what they read will meet their expectations. As a writer, your job is to make sure those expectations are met, while at the same time, fulfilling the purpose of your writing.

Once you have determined what type of purpose best conveys your motivations, you will then need to examine how this will affect your readers. Perhaps you are explaining your topic when you really should be convincing readers to see your point. Writers and readers may approach a topic with conflicting purposes. Your job, as a writer, is to make sure both are being met.

Purpose and Audience

Often your audience will help you determine your purpose. The beliefs they hold will tell you whether or not they agree with what you have to say. Suppose, for example, you are writing to persuade readers against Internet censorship. Your purpose will differ depending on the audience who will read your writing.

Audience One: Internet Users

If your audience is computer users who surf the net daily, you could appear foolish trying to persuade them to react against Internet censorship. It's likely they are already against such a movement. Instead, they might expect more information on the topic.

Audience Two: Parents

If your audience is parents who don't want their small children surfing the net, you'll need to convince them that censorship is not the solution to the problem. You should persuade this audience to consider other options.

Purpose and Focus

Your focus (otherwise known as thesis, claim, main idea, or problem statement) is a reflection of your purpose. If these two do not agree, you will not accomplish what you set out to do. Consider the following examples below:

Focus One: Informing

Suppose your purpose is to inform readers about relationships between Type A personalities and heart attacks. Your focus could then be: Type A personalities do not have an abnormally high risk of suffering heart attacks.

Focus Two: Persuading

Suppose your purpose is to persuade readers not to quarantine AIDS victims. Your focus could then be: Children afflicted with AIDS should not be prevented from attending school.

Writer and Reader Goals

Kate Kiefer, English Department Readers and writers both have goals when they engage in reading and writing. Writers typically define their goals in several categories-to inform, persuade, entertain, explore. When writers and readers have mutually fulfilling goals-to inform and to look for information-then writing and reading are most efficient. At times, these goals overlap one another. Many readers of science essays are looking for science information when they often get science philosophy. This mismatch of goals tends to leave readers frustrated, and if they communicate that frustration to the writer, then the writer feels misunderstood or unsuccessful.

Donna Lecourt, English Department Whatever reality you are writing within, whatever you chose to write about, implies a certain audience as well as your purpose for writing. You decide you have something to write about, or something you care about, then purpose determines audience.

Writer Versus Reader Purposes

Steve Reid, English Department A general definition of purpose relates to motivation. For instance, "I'm angry, and that's why I'm writing this." Purposes, in academic writing, are intentions the writer hopes to accomplish with a particular audience. Often, readers discover their own purpose within a text. While the writer may have intended one thing, the text actually does another, according to its readers.

Purpose and Writing Assignments

Instructors often state the purpose of a writing assignment on the assignment sheet. By carefully examining what it is you are asked to do, you can determine what your writing's purpose is.

Most assignment sheets ask you to perform a specific task. Key words listed on the assignment can help you determine why you are writing. If your instructor has not provided an assignment sheet, consider asking what the purpose of the assignment is.

Read over your assignment sheet. Make a note of words asking you to follow a specific task. For example, words such as:

These words require you to write about a topic in a specific way. Once you know the purpose of your writing, you can begin planning what information is necessary for that purpose.

Example Assignment

Imagine you are an administrator for the school district. In light of the Columbus controversy, you have been assigned to write a set of guidelines for teaching about Columbus in the district's elementary and junior high schools. These guidelines will explain official policy to parents and teachers in teaching children about Columbus and the significance of his voyages. They will also draw on arguments made on both sides of the controversy, as well as historical facts on which both sides agree.

The purpose of this assignment is to explain the official policy about teaching Columbus' voyages to parents and teachers.

Steve Reid, English Department Keywords in writing assignments give teachers and students direction about why we are writing. For instance, many assignments ask students to "describe" something. The word "describe" specifically indicated the writer is supposed to describe something visually. This is very general. Often, assignments are looking for something more specific. Maybe there is an argument the instructor intends be formulated. Maybe there is an implied thesis, but often teachers use general words such as "Write about" or "Describe" something, when they should use more specific words like, "Define" or "Explain" or "Argue" or "Persuade."

Purpose and Thesis

Writers choose from a variety of purposes for writing. They may write to express their thoughts in a personal letter, to explain concepts in a physics class, to explore ideas in a philosophy class, or to argue a point in a political science class.

Once they have their purpose in mind (and an audience for whom they are writing), writers may more clearly formulate their thesis. The thesis , claim , or main idea of an essay is related to the purpose. It is the sentence or sentences that fulfill the purpose and that state the exact point of the essay.

For example, if a writer wants to argue that high schools should strengthen foreign language training, her thesis sentence might be as follows:

"Because Americans are so culturally isolated, we need a national policy that supports increased foreign language instruction in elementary and secondary schools."

How Thesis is Related to Purpose

The following examples illustrate how subject, purpose and thesis are related. The subject is the most general statement of the topic. The purpose narrows the focus by indicating whether the writer wishes to express or explore ideas or actually explain or argue about the topic. The thesis sentence, claim, or main idea narrows the focus even farther. It is the sentence or sentences which focuses the topic for the writer and the reader.

Citation Information

Stephen Reid and Dawn Kowalski. (1994-2024). Understanding Your Purpose. The WAC Clearinghouse. Colorado State University. Available at https://wac.colostate.edu/repository/writing/guides/.

Copyright Information

Copyright © 1994-2024 Colorado State University and/or this site's authors, developers, and contributors . Some material displayed on this site is used with permission.

7 Essay Types and Their Purposes

Have you ever struggled with the purpose of an essay?

For some, it may be a question of “what’s the point of all this essay writing?”

For others, the word purpose is synonymous with type , and they simply need to determine what kind of essay to write in order to achieve their goal (or ace an assignment).

In either case, we hope to help you today.

What Is the Purpose of an Essay in Education?

Does it seem like every time you turn around, someone’s asking (okay, telling) you to write an essay?

That’s because there is a very good reason. Essay writing is an integral part of education that serves several purposes that may surprise you.

First, essay writing helps improve your spelling, grammar, and punctuation. However, those benefits are more on the superficial side. Necessary, yes, but writing an essay provides far more value than that.

Look at the many benefits you stand to gain:

- Writing in essay format teaches you how to communicate more effectively.

- You’ll learn to organize your thoughts and fine-tune your reasoning.

- Essay writing teaches you valuable research skills as you find and filter facts to support your viewpoint.

- As you learn to express yourself better, you’ll become more concise and precise in your language.

You are essentially practicing the ability to explain yourself clearly and articulate your thoughts. This will serve you well as you interact with future partners, bosses, and others.

ENTER THE GIVEAWAY!

The right topic is critical to the success of any essay. Enter to win a copy of our newest resource:

170 Good Argument Topics for High School Essays & Debate

Points to Consider as You Craft Your Purpose Statement

Now that we’ve discussed the purpose of essay writing, let’s transition into learning more about the purpose of each individual essay.

It’s important to know your essay’s purpose before ever putting pen to paper.

Once you’ve decided on an objective for each essay, you’ll want to let your reader know your intent right away.

To do that, you need to learn how to state the purpose of an essay effectively. This is called, appropriately enough, a “purpose statement.”

Unlike a thesis statement, which lays out your topic and arguments in your introduction, a purpose statement is more about how you intend to do that.

Are you defending a stance in hopes of convincing someone to take action? Tell your reader that’s what you plan to do.

Are you hoping to teach people how to implement an idea or produce something? State upfront that the purpose of this essay is instructional.

A purpose statement includes defining the scope of the paper, along with sharing the focus of the essay and the direction in which you plan to take it.

Let me pause here and say something that may sound odd:

Your purpose statement doesn’t necessarily have to be used in your essay. It may, especially if it doubles as your thesis statement, but defining your essay’s purpose is more for your own direction.

Clearly defining what you are doing and why will help you craft a coherent essay that achieves its goal.

7 Types of Essays: Their Purposes and Examples

After clarifying the purpose of your essay, you’ll want to choose an essay genre to achieve your intention effectively—if it hasn’t be chosen for you, that is.

(If you aren’t sure what to write about, get help with choosing a topic here .)

There are several essay types that help communicate different ideas, so it’s helpful to know which type lends itself to the best outcome.

To help you decide, we’ve laid out seven common essay types and their purposes:

One reason to write an essay is to teach your reader new or changing information on a topic.

The purpose of an informative essay could be to provide a deeper understanding of a well-known subject, but it can also introduce the reader to an unfamiliar topic.

This would be a type of educational essay —one meant to use facts and data to inform your audience. This is not an essay designed to persuade the reader or evoke emotion.

Another form of an educational essay is one designed to teach a process or simplify a difficult subject.

One function of an expository essay , as it’s also known, is to explain a topic, so it’s important for you to be familiarize yourself with the topic first before digging into the writing.

You can’t clarify what you don’t know.

Sometimes an essay is written in response to someone else’s ideas. Depending on the topic, this can be an academic essay or less formal analysis of some sort (like a personal reaction).

In either case, the purpose of a response essay is to share your own perspective with the reader.

The ideas you’re responding to can come from a body of work, a literary analysis, a news story, or a statement from a public figure. It can even be in response to a commonly held opinion or belief.

In a response essay, you’ll begin by providing an overview of the subject to which you’re replying. You would then continue this type of essay by providing your opinion backed by research and facts.

4. Persuade

The purpose of persuasive writing is to use logic to convince someone to react one way or another.

You may include a specific call to action, such as exhorting the reader to petition their local government for positive change.

Crafting a persuasive essay is similar to preparing for a debate but without the opposing party. It typically involves a strong opinion that is so well researched and backed by facts that it influences the reader to change their own opinion.

5. Entertain

While most people think of formal, academic papers when they hear the word “essay,” you can also write an essay solely to entertain your reader.

Essays designed to entertain, such as narratives, aim to elicit some sort of emotional response from the reader. The purpose of descriptive text in this type of essay is to bring forth a clear picture in the reader’s mind.

Careful choice of words is critical in this type of essay. You will use them to trigger some form of emotion in the heart of your reader.

6. Contrast

I’m sure you’ve seen or heard of an essay type called “Compare and Contrast.”

This is a common type of essay in which the writer discusses the differences or similarities between separate ideas or topics.

For example, you may be asked to compare two works of literature. On the other hand, the purpose of your essay may be to shed light on the pros and cons of two choices, such as attending college vs. heading straight into a career.

If it’s a contrast piece, you will want to note less obvious differences between your two topics. For example, everyone knows that college costs money while working pays money.

But what are the more subtle differences that the reader may not have considered? It’s your job to clearly identify those distinctions.

In a review essay, the writer summarizes and critically evaluates a body of work, usually a novel, poem, or film.

The review essay uses the writer’s own perspective of the work to talk at length about its strengths and weaknesses.

Once you solidify the purpose of an essay, your first two steps are clear:

First, you will craft either a purpose statement for your own clarification or a thesis statement to use in the introduction, which should present your essay’s topic in an intriguing way.

Then, you’ll choose an appropriate vehicle to convey that message effectively by choosing an essay type that serves your purpose well.

(Once you know what type of essay you’ll be writing, discover how to start an essay effectively .)

If you need help polishing your essay writing, don’t miss the incredible tales and tips found in Philosophy Adventure :

Teach Your Students to Write Skillfully

As they explore the history of ideas!

About The Author

Jordan Mitchell

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

We define an argumentative essay as a type of essay that presents arguments about both sides of an issue. The purpose is to convince the reader to accept a particular viewpoint or action. In an argumentative essay, the writer takes a stance on a controversial or debatable topic and supports their position with evidence, reasoning, and examples. The essay should also address counterarguments, demonstrating a thorough understanding of the topic.

Table of Contents

- What is an argumentative essay?

- Argumentative essay structure

- Argumentative essay outline

- Types of argument claims

How to write an argumentative essay?

- Argumentative essay writing tips

- Good argumentative essay example

How to write a good thesis

- How to Write an Argumentative Essay with Paperpal?

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an argumentative essay.

An argumentative essay is a type of writing that presents a coherent and logical analysis of a specific topic. 1 The goal is to convince the reader to accept the writer’s point of view or opinion on a particular issue. Here are the key elements of an argumentative essay:

- Thesis Statement : The central claim or argument that the essay aims to prove.

- Introduction : Provides background information and introduces the thesis statement.

- Body Paragraphs : Each paragraph addresses a specific aspect of the argument, presents evidence, and may include counter arguments.

Articulate your thesis statement better with Paperpal. Start writing now!

- Evidence : Supports the main argument with relevant facts, examples, statistics, or expert opinions.

- Counterarguments : Anticipates and addresses opposing viewpoints to strengthen the overall argument.

- Conclusion : Summarizes the main points, reinforces the thesis, and may suggest implications or actions.

Argumentative essay structure

Aristotelian, Rogerian, and Toulmin are three distinct approaches to argumentative essay structures, each with its principles and methods. 2 The choice depends on the purpose and nature of the topic. Here’s an overview of each type of argumentative essay format.

Have a looming deadline for your argumentative essay? Write 2x faster with Paperpal – Start now!

Argumentative essay outline

An argumentative essay presents a specific claim or argument and supports it with evidence and reasoning. Here’s an outline for an argumentative essay, along with examples for each section: 3

1. Introduction :

- Hook : Start with a compelling statement, question, or anecdote to grab the reader’s attention.

Example: “Did you know that plastic pollution is threatening marine life at an alarming rate?”

- Background information : Provide brief context about the issue.

Example: “Plastic pollution has become a global environmental concern, with millions of tons of plastic waste entering our oceans yearly.”

- Thesis statement : Clearly state your main argument or position.

Example: “We must take immediate action to reduce plastic usage and implement more sustainable alternatives to protect our marine ecosystem.”

2. Body Paragraphs :

- Topic sentence : Introduce the main idea of each paragraph.

Example: “The first step towards addressing the plastic pollution crisis is reducing single-use plastic consumption.”

- Evidence/Support : Provide evidence, facts, statistics, or examples that support your argument.

Example: “Research shows that plastic straws alone contribute to millions of tons of plastic waste annually, and many marine animals suffer from ingestion or entanglement.”

- Counterargument/Refutation : Acknowledge and refute opposing viewpoints.

Example: “Some argue that banning plastic straws is inconvenient for consumers, but the long-term environmental benefits far outweigh the temporary inconvenience.”

- Transition : Connect each paragraph to the next.

Example: “Having addressed the issue of single-use plastics, the focus must now shift to promoting sustainable alternatives.”

3. Counterargument Paragraph :

- Acknowledgement of opposing views : Recognize alternative perspectives on the issue.

Example: “While some may argue that individual actions cannot significantly impact global plastic pollution, the cumulative effect of collective efforts must be considered.”

- Counterargument and rebuttal : Present and refute the main counterargument.

Example: “However, individual actions, when multiplied across millions of people, can substantially reduce plastic waste. Small changes in behavior, such as using reusable bags and containers, can have a significant positive impact.”

4. Conclusion :

- Restatement of thesis : Summarize your main argument.

Example: “In conclusion, adopting sustainable practices and reducing single-use plastic is crucial for preserving our oceans and marine life.”

- Call to action : Encourage the reader to take specific steps or consider the argument’s implications.

Example: “It is our responsibility to make environmentally conscious choices and advocate for policies that prioritize the health of our planet. By collectively embracing sustainable alternatives, we can contribute to a cleaner and healthier future.”

Types of argument claims

A claim is a statement or proposition a writer puts forward with evidence to persuade the reader. 4 Here are some common types of argument claims, along with examples:

- Fact Claims : These claims assert that something is true or false and can often be verified through evidence. Example: “Water boils at 100°C at sea level.”

- Value Claims : Value claims express judgments about the worth or morality of something, often based on personal beliefs or societal values. Example: “Organic farming is more ethical than conventional farming.”

- Policy Claims : Policy claims propose a course of action or argue for a specific policy, law, or regulation change. Example: “Schools should adopt a year-round education system to improve student learning outcomes.”

- Cause and Effect Claims : These claims argue that one event or condition leads to another, establishing a cause-and-effect relationship. Example: “Excessive use of social media is a leading cause of increased feelings of loneliness among young adults.”

- Definition Claims : Definition claims assert the meaning or classification of a concept or term. Example: “Artificial intelligence can be defined as machines exhibiting human-like cognitive functions.”

- Comparative Claims : Comparative claims assert that one thing is better or worse than another in certain respects. Example: “Online education is more cost-effective than traditional classroom learning.”

- Evaluation Claims : Evaluation claims assess the quality, significance, or effectiveness of something based on specific criteria. Example: “The new healthcare policy is more effective in providing affordable healthcare to all citizens.”

Understanding these argument claims can help writers construct more persuasive and well-supported arguments tailored to the specific nature of the claim.

If you’re wondering how to start an argumentative essay, here’s a step-by-step guide to help you with the argumentative essay format and writing process.

- Choose a Topic: Select a topic that you are passionate about or interested in. Ensure that the topic is debatable and has two or more sides.

- Define Your Position: Clearly state your stance on the issue. Consider opposing viewpoints and be ready to counter them.

- Conduct Research: Gather relevant information from credible sources, such as books, articles, and academic journals. Take notes on key points and supporting evidence.

- Create a Thesis Statement: Develop a concise and clear thesis statement that outlines your main argument. Convey your position on the issue and provide a roadmap for the essay.

- Outline Your Argumentative Essay: Organize your ideas logically by creating an outline. Include an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Each body paragraph should focus on a single point that supports your thesis.

- Write the Introduction: Start with a hook to grab the reader’s attention (a quote, a question, a surprising fact). Provide background information on the topic. Present your thesis statement at the end of the introduction.

- Develop Body Paragraphs: Begin each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that relates to the thesis. Support your points with evidence and examples. Address counterarguments and refute them to strengthen your position. Ensure smooth transitions between paragraphs.

- Address Counterarguments: Acknowledge and respond to opposing viewpoints. Anticipate objections and provide evidence to counter them.

- Write the Conclusion: Summarize the main points of your argumentative essay. Reinforce the significance of your argument. End with a call to action, a prediction, or a thought-provoking statement.

- Revise, Edit, and Share: Review your essay for clarity, coherence, and consistency. Check for grammatical and spelling errors. Share your essay with peers, friends, or instructors for constructive feedback.

- Finalize Your Argumentative Essay: Make final edits based on feedback received. Ensure that your essay follows the required formatting and citation style.

Struggling to start your argumentative essay? Paperpal can help – try now!

Argumentative essay writing tips

Here are eight strategies to craft a compelling argumentative essay:

- Choose a Clear and Controversial Topic : Select a topic that sparks debate and has opposing viewpoints. A clear and controversial issue provides a solid foundation for a strong argument.

- Conduct Thorough Research : Gather relevant information from reputable sources to support your argument. Use a variety of sources, such as academic journals, books, reputable websites, and expert opinions, to strengthen your position.

- Create a Strong Thesis Statement : Clearly articulate your main argument in a concise thesis statement. Your thesis should convey your stance on the issue and provide a roadmap for the reader to follow your argument.

- Develop a Logical Structure : Organize your essay with a clear introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. Each paragraph should focus on a specific point of evidence that contributes to your overall argument. Ensure a logical flow from one point to the next.

- Provide Strong Evidence : Support your claims with solid evidence. Use facts, statistics, examples, and expert opinions to support your arguments. Be sure to cite your sources appropriately to maintain credibility.

- Address Counterarguments : Acknowledge opposing viewpoints and counterarguments. Addressing and refuting alternative perspectives strengthens your essay and demonstrates a thorough understanding of the issue. Be mindful of maintaining a respectful tone even when discussing opposing views.

- Use Persuasive Language : Employ persuasive language to make your points effectively. Avoid emotional appeals without supporting evidence and strive for a respectful and professional tone.

- Craft a Compelling Conclusion : Summarize your main points, restate your thesis, and leave a lasting impression in your conclusion. Encourage readers to consider the implications of your argument and potentially take action.

Good argumentative essay example

Let’s consider a sample of argumentative essay on how social media enhances connectivity:

In the digital age, social media has emerged as a powerful tool that transcends geographical boundaries, connecting individuals from diverse backgrounds and providing a platform for an array of voices to be heard. While critics argue that social media fosters division and amplifies negativity, it is essential to recognize the positive aspects of this digital revolution and how it enhances connectivity by providing a platform for diverse voices to flourish. One of the primary benefits of social media is its ability to facilitate instant communication and connection across the globe. Platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram break down geographical barriers, enabling people to establish and maintain relationships regardless of physical location and fostering a sense of global community. Furthermore, social media has transformed how people stay connected with friends and family. Whether separated by miles or time zones, social media ensures that relationships remain dynamic and relevant, contributing to a more interconnected world. Moreover, social media has played a pivotal role in giving voice to social justice movements and marginalized communities. Movements such as #BlackLivesMatter, #MeToo, and #ClimateStrike have gained momentum through social media, allowing individuals to share their stories and advocate for change on a global scale. This digital activism can shape public opinion and hold institutions accountable. Social media platforms provide a dynamic space for open dialogue and discourse. Users can engage in discussions, share information, and challenge each other’s perspectives, fostering a culture of critical thinking. This open exchange of ideas contributes to a more informed and enlightened society where individuals can broaden their horizons and develop a nuanced understanding of complex issues. While criticisms of social media abound, it is crucial to recognize its positive impact on connectivity and the amplification of diverse voices. Social media transcends physical and cultural barriers, connecting people across the globe and providing a platform for marginalized voices to be heard. By fostering open dialogue and facilitating the exchange of ideas, social media contributes to a more interconnected and empowered society. Embracing the positive aspects of social media allows us to harness its potential for positive change and collective growth.

- Clearly Define Your Thesis Statement: Your thesis statement is the core of your argumentative essay. Clearly articulate your main argument or position on the issue. Avoid vague or general statements.

- Provide Strong Supporting Evidence: Back up your thesis with solid evidence from reliable sources and examples. This can include facts, statistics, expert opinions, anecdotes, or real-life examples. Make sure your evidence is relevant to your argument, as it impacts the overall persuasiveness of your thesis.

- Anticipate Counterarguments and Address Them: Acknowledge and address opposing viewpoints to strengthen credibility. This also shows that you engage critically with the topic rather than presenting a one-sided argument.

How to Write an Argumentative Essay with Paperpal?

Writing a winning argumentative essay not only showcases your ability to critically analyze a topic but also demonstrates your skill in persuasively presenting your stance backed by evidence. Achieving this level of writing excellence can be time-consuming. This is where Paperpal, your AI academic writing assistant, steps in to revolutionize the way you approach argumentative essays. Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to use Paperpal to write your essay:

- Sign Up or Log In: Begin by creating an account or logging into paperpal.com .

- Navigate to Paperpal Copilot: Once logged in, proceed to the Templates section from the side navigation bar.

- Generate an essay outline: Under Templates, click on the ‘Outline’ tab and choose ‘Essay’ from the options and provide your topic to generate an outline.

- Develop your essay: Use this structured outline as a guide to flesh out your essay. If you encounter any roadblocks, click on Brainstorm and get subject-specific assistance, ensuring you stay on track.

- Refine your writing: To elevate the academic tone of your essay, select a paragraph and use the ‘Make Academic’ feature under the ‘Rewrite’ tab, ensuring your argumentative essay resonates with an academic audience.

- Final Touches: Make your argumentative essay submission ready with Paperpal’s language, grammar, consistency and plagiarism checks, and improve your chances of acceptance.

Paperpal not only simplifies the essay writing process but also ensures your argumentative essay is persuasive, well-structured, and academically rigorous. Sign up today and transform how you write argumentative essays.

The length of an argumentative essay can vary, but it typically falls within the range of 1,000 to 2,500 words. However, the specific requirements may depend on the guidelines provided.

You might write an argumentative essay when: 1. You want to convince others of the validity of your position. 2. There is a controversial or debatable issue that requires discussion. 3. You need to present evidence and logical reasoning to support your claims. 4. You want to explore and critically analyze different perspectives on a topic.

Argumentative Essay: Purpose : An argumentative essay aims to persuade the reader to accept or agree with a specific point of view or argument. Structure : It follows a clear structure with an introduction, thesis statement, body paragraphs presenting arguments and evidence, counterarguments and refutations, and a conclusion. Tone : The tone is formal and relies on logical reasoning, evidence, and critical analysis. Narrative/Descriptive Essay: Purpose : These aim to tell a story or describe an experience, while a descriptive essay focuses on creating a vivid picture of a person, place, or thing. Structure : They may have a more flexible structure. They often include an engaging introduction, a well-developed body that builds the story or description, and a conclusion. Tone : The tone is more personal and expressive to evoke emotions or provide sensory details.

- Gladd, J. (2020). Tips for Writing Academic Persuasive Essays. Write What Matters .

- Nimehchisalem, V. (2018). Pyramid of argumentation: Towards an integrated model for teaching and assessing ESL writing. Language & Communication , 5 (2), 185-200.

- Press, B. (2022). Argumentative Essays: A Step-by-Step Guide . Broadview Press.

- Rieke, R. D., Sillars, M. O., & Peterson, T. R. (2005). Argumentation and critical decision making . Pearson/Allyn & Bacon.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

- Life Sciences Papers: 9 Tips for Authors Writing in Biological Sciences

Make Your Research Paper Error-Free with Paperpal’s Online Spell Checker

The do’s & don’ts of using generative ai tools ethically in academia, you may also like, 4 ways paperpal encourages responsible writing with ai, what are scholarly sources and where can you..., how to write a hypothesis types and examples , what is academic writing: tips for students, what is hedging in academic writing , how to use ai to enhance your college..., how to use paperpal to generate emails &..., ai in education: it’s time to change the..., is it ethical to use ai-generated abstracts without..., do plagiarism checkers detect ai content.

Informative Essay — Purpose, Structure, and Examples

What is informative writing?

Informative writing educates the reader about a certain topic. An informative essay may explain new information, describe a process, or clarify a concept. The provided information is objective, meaning the writing focuses on presentation of fact and should not contain personal opinion or bias.

Informative writing includes description, process, cause and effect, comparison, and problems and possible solutions:

Describes a person, place, thing, or event using descriptive language that appeals to readers’ senses

Explains the process to do something or how something was created

Discusses the relationship between two things, determining how one ( cause ) leads to the other ( effect ); the effect needs to be based on fact and not an assumption

Identifies the similarities and differences between two things; does not indicate that one is better than the other

Details a problem and presents various possible solutions ; the writer does not suggest one solution is more effective than the others

Purpose of informative writing

The purpose of an informative essay depends upon the writer’s motivation, but may be to share new information, describe a process, clarify a concept, explain why or how, or detail a topic’s intricacies.

Informative essays may introduce readers to new information .

Summarizing a scientific/technological study

Outlining the various aspects of a religion

Providing information on a historical period

Describe a process or give step-by-step details of a procedure.

How to write an informational essay

How to construct an argument

How to apply for a job

Clarify a concept and offer details about complex ideas.

Explain why or how something works the way that it does.

Describe how the stock market impacts the economy

Illustrate why there are high and low tides

Detail how the heart functions

Offer information on the smaller aspects or intricacies of a larger topic.

Identify the importance of the individual bones in the body

Outlining the Dust Bowl in the context of the Great Depression

Explaining how bees impact the environment

How to write an informative essay

Regardless of the type of information, the informative essay structure typically consists of an introduction, body, and conclusion.

Introduction

Background information

Explanation of evidence

Restated thesis

Review of main ideas

Closing statement

Informative essay introduction

When composing the introductory paragraph(s) of an informative paper, include a hook, introduce the topic, provide background information, and develop a good thesis statement.

If the hook or introduction creates interest in the first paragraph, it will draw the readers’ attention and make them more receptive to the essay writer's ideas. Some of the most common techniques to accomplish this include the following:

Emphasize the topic’s importance by explaining the current interest in the topic or by indicating that the subject is influential.

Use pertinent statistics to give the paper an air of authority.

A surprising statement can be shocking; sometimes it is disgusting; sometimes it is joyful; sometimes it is surprising because of who said it.

An interesting incident or anecdote can act as a teaser to lure the reader into the remainder of the essay. Be sure that the device is appropriate for the informative essay topic and focus on what is to follow.

Directly introduce the topic of the essay.

Provide the reader with the background information necessary to understand the topic. Don’t repeat this information in the body of the essay; it should help the reader understand what follows.

Identify the overall purpose of the essay with the thesis (purpose statement). Writers can also include their support directly in the thesis, which outlines the structure of the essay for the reader.

Informative essay body paragraphs

Each body paragraph should contain a topic sentence, evidence, explanation of evidence, and a transition sentence.

A good topic sentence should identify what information the reader should expect in the paragraph and how it connects to the main purpose identified in the thesis.

Provide evidence that details the main point of the paragraph. This includes paraphrasing, summarizing, and directly quoting facts, statistics, and statements.

Explain how the evidence connects to the main purpose of the essay.

Place transitions at the end of each body paragraph, except the last. There is no need to transition from the last support to the conclusion. A transition should accomplish three goals:

Tell the reader where you were (current support)

Tell the reader where you are going (next support)

Relate the paper’s purpose

Informative essay conclusion

Incorporate a rephrased thesis, summary, and closing statement into the conclusion of an informative essay.

Rephrase the purpose of the essay. Do not just repeat the purpose statement from the thesis.

Summarize the main idea found in each body paragraph by rephrasing each topic sentence.

End with a clincher or closing statement that helps readers answer the question “so what?” What should the reader take away from the information provided in the essay? Why should they care about the topic?

Informative essay example

The following example illustrates a good informative essay format:

What is the Purpose of Education?

This essay about the purpose of education explores its multifaceted role in igniting curiosity, nurturing creativity, fostering empathy, and empowering individuals. It delves into education’s function as a compass guiding critical thinking and as a catalyst for personal and societal growth. Emphasizing its transformative power, the essay advocates for dismantling barriers to quality education to ensure everyone can fulfill their potential and contribute meaningfully to society.

How it works

Education, akin to a kaleidoscope, refracts the spectrum of human potential into a mesmerizing array of colors, patterns, and possibilities. Yet, amidst this dazzling display, the question persists: what is the true purpose of education? Let us embark on a journey of inquiry, traversing the landscapes of thought and imagination, to unravel the intricate tapestry of education’s multifaceted mission: to ignite the flames of curiosity, nurture the seeds of innovation, foster the gardens of empathy, and empower individuals to navigate the labyrinthine corridors of existence with purpose and resilience.

Education, in its essence, serves as the alchemist’s crucible, transmuting raw knowledge into the gold of wisdom. It is the compass that guides seekers through the labyrinth of information, teaching not only what to think but also how to question, analyze, and synthesize. In an age of information overload, where the cacophony of voices clamors for attention, education becomes the beacon of discernment, illuminating the path toward critical thinking and informed decision-making.

Moreover, education is the fertile soil in which the seeds of creativity take root and flourish. It is the canvas upon which the brushstrokes of imagination paint the tapestry of human ingenuity. From the symphonies of Mozart to the theories of Einstein, creativity permeates every facet of human endeavor, propelling civilization forward on the wings of innovation. Education, therefore, must embrace its role as the nurturer of creativity, fostering an environment where ideas are celebrated, risks are encouraged, and failures are seen as opportunities for growth.

Yet, education is not solely an intellectual pursuit; it is a journey of the heart, nurturing the seeds of empathy and compassion within the human soul. It is the crucible in which the fires of empathy are kindled, enabling individuals to see the world through the eyes of others and embrace the interconnectedness of all life. Through exposure to diverse perspectives and experiences, education cultivates the empathetic imagination, fostering a sense of solidarity and shared humanity.

Furthermore, education serves as the great equalizer, bestowing upon individuals the tools to carve their destinies and transcend the limitations of circumstance. It is the key that unlocks the doors of opportunity, empowering individuals to chart their own course and pursue their dreams. Yet, in a world marked by inequality and injustice, access to quality education remains elusive for millions. It is incumbent upon society, therefore, to dismantle the barriers that obstruct the path to education, ensuring that every individual has the opportunity to fulfill their potential and contribute meaningfully to society.

In conclusion, the purpose of education extends far beyond the transmission of knowledge; it is the catalyst for personal growth, societal progress, and global transformation. As we navigate the complexities of the 21st century, let us embrace the transformative power of education to shape a world where curiosity is celebrated, creativity flourishes, empathy abounds, and every individual has the opportunity to thrive. For in the mosaic of human potential, education emerges as the thread that binds us together in our quest for a brighter tomorrow.

Cite this page

What Is the Purpose of Education?. (2024, Apr 29). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/what-is-the-purpose-of-education/

"What Is the Purpose of Education?." PapersOwl.com , 29 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/what-is-the-purpose-of-education/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). What Is the Purpose of Education? . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/what-is-the-purpose-of-education/ [Accessed: 2 May. 2024]

"What Is the Purpose of Education?." PapersOwl.com, Apr 29, 2024. Accessed May 2, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/what-is-the-purpose-of-education/

"What Is the Purpose of Education?," PapersOwl.com , 29-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/what-is-the-purpose-of-education/. [Accessed: 2-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). What Is the Purpose of Education? . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/what-is-the-purpose-of-education/ [Accessed: 2-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Workplace Articles & More

How purpose changes across your lifetime, purpose is not a destination, suggests research, but a journey and a practice..

Purpose is the stuff of inspirational posters and motivational speeches. When we find our purpose, they say, we’ll know what we are meant to do in life. The path will be laid out before us, and our job will be to keep following that vision with unwavering commitment.

But is this really what purpose looks like?