Robert Hooke

(1635-1703)

Who Was Robert Hooke?

Scientist Robert Hooke was educated at Oxford and spent his career at the Royal Society and Gresham College. His research and experiments ranged from astronomy to biology to physics; he is particularly recognized for the observations he made while using a microscope and for "Hooke's Law" of elasticity. Hooke died in London in 1703.

Early Life and Education

Robert Hooke was born in the town of Freshwater, on England’s Isle of Wight, on July 18, 1635. His parents were John Hooke, who served as curate for the local church parish, and Cecily (née Gyles) Hooke.

Initially a sickly child, Hooke grew to be a quick learner who was interested in painting and adept at making mechanical toys and models. After his father’s death in 1648, the 13-year-old Hooke was sent to London to apprentice with painter Peter Lely. This connection turned out to be a short one, and he went instead to study at London’s Westminster School.

In 1653, Hooke enrolled at Oxford's Christ Church College, where he supplemented his meager funds by working as an assistant to the scientist Robert Boyle. While studying subjects ranging from astronomy to chemistry, Hooke also made influential friends, such as future architect Christopher Wren.

Teaching, Research and Other Occupations

Hooke was appointed curator of experiments for the newly formed Royal Society of London in 1662, a position he obtained with Boyle's support. Hooke became a fellow of the society in 1663.

Unlike many of the gentleman scientists he interacted with, Hooke required an income. In 1665, he accepted a position as professor of geometry at Gresham College in London. After the "Great Fire" destroyed much of London in 1666, Hooke became a city surveyor. Working with Wren, he assessed the damage and redesigned many of London’s streets and public buildings.

Major Discoveries and Achievements

A true polymath, the topics Hooke covered during his career include comets, the motion of light, the rotation of Jupiter, gravity, human memory and the properties of air. In all of his studies and demonstrations, he adhered to the scientific method of experimentation and observation. Hooke also utilized the most up-to-date instruments in his many projects.

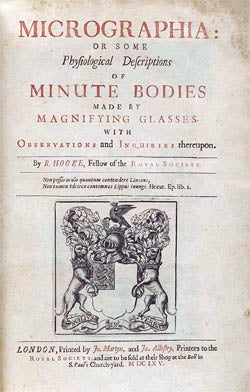

Hooke’s most important publication was Micrographia , a 1665 volume documenting experiments he had made with a microscope. In this groundbreaking study, he coined the term "cell" while discussing the structure of cork. He also described flies, feathers and snowflakes, and correctly identified fossils as remnants of once-living things.

The 1678 publication of Hooke's Lectures of Spring shared his theory of elasticity; in what came to be known as "Hooke’s Law," he stated that the force required to extend or compress a spring is proportional to the distance of that extension or compression. In an ongoing, related project, Hooke worked for many years on the invention of a spring-regulated watch.

Personal Life and Death

Hooke never married. His niece, Grace Hooke, his longtime live-in companion and housekeeper, as well as his eventual lover, died in 1687; Hooke was inconsolable at the loss.

In his last year of life, Hooke suffered from symptoms that may have been caused by diabetes. He died at the age of 67 in London on March 3, 1703.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Robert Hooke

- Birth Year: 1635

- Birth date: July 18, 1635

- Birth City: Freshwater, Isle of Wight

- Birth Country: England

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Robert Hooke is known as a "Renaissance Man" of 17th century England for his work in the sciences, which covered areas such as astronomy, physics and biology.

- Education and Academia

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Architecture

- Business and Industry

- Science and Medicine

- Technology and Engineering

- Astrological Sign: Cancer

- Wadham College

- Death Year: 1703

- Death date: March 3, 1703

- Death City: London

- Death Country: England

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Robert Hooke Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/scientists/robert-hooke

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: June 22, 2020

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

Famous British People

Mick Jagger

Agatha Christie

Alexander McQueen

The Real Royal Scheme Depicted in ‘Mary & George’

William Shakespeare

Anya Taylor-Joy

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Prince William

Where in the World Is Kate Middleton?

Biography of Robert Hooke, the Man Who Discovered Cells

Robert Hooke/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

- Cell Biology

- Weather & Climate

Robert Hooke (July 18, 1635–March 3, 1703) was a 17th-century "natural philosopher"—an early scientist—noted for a variety of observations of the natural world. But perhaps his most notable discovery came in 1665 when he looked at a sliver of cork through a microscope lens and discovered cells.

Fast Facts: Robert Hooke

- Known For: Experiments with a microscope, including the discovery of cells, and coining of the term

- Born: July 18, 1635 in Freshwater, the Isle of Wight, England

- Parents: John Hooke, vicar of Freshwater and his second wife Cecily Gyles

- Died: March 3, 1703 in London

- Education: Westminster in London, and Christ Church at Oxford, as a laboratory assistant of Robert Boyle

- Published Works: Micrographia: or some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries Thereupon

Robert Hooke was born July 18, 1635, in Freshwater on the Isle of Wight off the southern coast of England, the son of the vicar of Freshwater John Hooke and his second wife Cecily Gates. His health was delicate as a child, so Robert was kept at home until after his father died. In 1648, when Hooke was 13, he went to London and was first apprenticed to painter Peter Lely and proved fairly good at the art, but he left because the fumes affected him. He enrolled at Westminster School in London, where he received a solid academic education including Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, and also gained training as an instrument maker.

He later went on to Oxford and, as a product of Westminster, entered Christ Church college, where he became the friend and laboratory assistant of Robert Boyle, best known for his natural law of gases known as Boyle's Law. Hooke invented a wide range of things at Christ Church, including a balance spring for watches, but he published few of them. He did publish a tract on capillary attraction in 1661, and it was that treatise the brought him to the attention of the Royal Society for Promoting Natural History, founded just a year earlier.

The Royal Society

The Royal Society for Promoting Natural History (or Royal Society) was founded in November 1660 as a group of like-minded scholars. It was not associated with a particular university but rather funded under the patronage of the British king Charles II. Members during Hooke's day included Boyle, the architect Christopher Wren , and the natural philosophers John Wilkins and Isaac Newton; today, it boasts 1,600 fellows from around the world.

In 1662, the Royal Society offered Hooke the initially unpaid curator position, to furnish the society with three or four experiments each week—they promised to pay him as soon as the society had the money. Hooke did eventually get paid for the curatorship, and when he was named a professor of geometry, he gained housing at Gresham college. Hooke remained in those positions for the rest of his life; they offered him the opportunity to research whatever interested him.

Observations and Discoveries

Hooke was, like many of the members of the Royal Society, wide-reaching in his interests. Fascinated by seafaring and navigation, Hooke invented a depth sounder and water sampler. In September 1663, he began keeping daily weather records, hoping that would lead to reasonable weather predictions. He invented or improved all five basic meteorological instruments (the barometer, thermometer, hydroscope, rain gauge, and wind gauge), and developed and printed a form to record weather data.

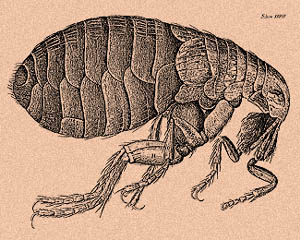

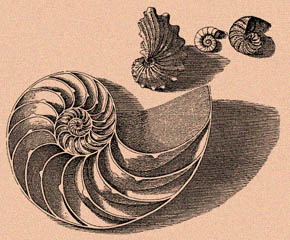

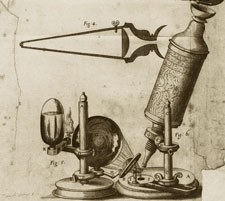

Some 40 years before Hooke joined the Royal Society, Galileo had invented the microscope (called an occhiolino at the time, or "wink" in Italian); as curator, Hooke bought a commercial version and began an extremely wide and varying amount of research with it, looking at plants, molds, sand, and fleas. Among his discoveries were fossil shells in sand (now recognized as foraminifera), spores in mold, and the bloodsucking practices of mosquitoes and lice.

Discovery of the Cell

Hooke is best known today for his identification of the cellular structure of plants. When he looked at a sliver of cork through his microscope, he noticed some "pores" or "cells" in it. Hooke believed the cells had served as containers for the "noble juices" or "fibrous threads" of the once-living cork tree. He thought these cells existed only in plants, since he and his scientific contemporaries had observed the structures only in plant material.

Nine months of experiments and observations are recorded in his 1665 book "Micrographia: or some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries Thereupon," the first book describing observations made through a microscope. It featured many drawings, some of which have been attributed to Christopher Wren, such as that of a detailed flea observed through the microscope. Hooke was the first person to use the word "cell" to identify microscopic structures when he was describing cork.

His other observations and discoveries include:

- Hooke's Law: A law of elasticity for solid bodies, which described how tension increases and decreases in a spring coil

- Various observations on the nature of gravity, as well as heavenly bodies such as comets and planets

- The nature of fossilization, and its implications for biological history

Death and Legacy

Hooke was a brilliant scientist, a pious Christian, and a difficult and impatient man. What kept him from true success was a lack of interest in mathematics. Many of his ideas inspired and were completed by others in and outside of the Royal Society, such as the Dutch pioneer microbiologist Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723), navigator and geographer William Dampier (1652–1715), geologist Niels Stenson (better known as Steno, 1638–1686), and Hooke's personal nemesis, Isaac Newton (1642–1727). When the Royal Society published Newton's "Principia" in 1686, Hooke accused him of plagiarism, a situation so profoundly affecting Newton that he put off publishing "Optics" until after Hooke was dead.

Hooke kept a diary in which he discussed his infirmities, which were many, but although it doesn't have literary merit like Samuel Pepys', it also describes many details of daily life in London after the Great Fire. He died, suffering from scurvy and other unnamed and unknown illnesses, on March 3, 1703. He neither married nor had children.

- Egerton, Frank N. " A History of the Ecological Sciences, Part 16: Robert Hooke and the Royal Society of London ." Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 86.2 (2005): 93–101. Print.

- Jardine, Lisa. " Monuments and Microscopes: Scientific Thinking on a Grand Scale in the Early Royal Society ." Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 55.2 (2001): 289–308. Print.

- Nakajima, Hideto. " Robert Hooke's Family and His Youth: Some New Evidence from the Will of the Rev. John Hooke ." Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 48.1 (1994): 11–16. Print.

- Whitrow, G. J. " Robert Hooke ." Philosophy of Science 5.4 (1938): 493–502. Print.

" Fellows ." The Royal Society.

- Robert Hooke Biography (1635 - 1703)

- Biography of Robert Hooke

- Sir Christopher Wren, the Man Who Rebuilt London After the Fire

- History of Microscopes

- Biography of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, Father of Microbiology

- History of the Microscope

- Meet William Herschel: Astronomer and Musician

- The History of the Hygrometer

- Biography of Isaac Newton, Mathematician and Scientist

- 17th Century Timeline, 1600 Through 1699

- Cosmos Episode 3 Viewing Worksheet

- What Is Cell Biology?

- Biography of Charles Wheatstone, British Inventor and Entrepreneur

- Jan Ingenhousz: Scientist Who Discovered Photosynthesis

- Biography of Jagadish Chandra Bose, Modern-Day Polymath

- Famous July Inventions and Birthdays

MacTutor

Robert hooke.

Hooke was fortunate in gaining the respect of Dr Busby and being left to follow his own pursuits of knowledge just as he had before attending Westminster School.

... Hooke never took a bachelor's degree [ but ] Oxford had given him more than a thousand degrees could match.

... use of springs instead of gravity for making a body vibrate in any posture.

Before I went to bed I sat up till two o'clock in my chamber reading Mr Hooke's Microscopical Observations, the most ingenious book that ever I read in my life.

Micrographia remains one of the masterpieces of seventeenth century science. ... [ it ] presented not a systematic investigation of any one question, but a bouquet of observations with courses from the mineral, animal and vegetable kingdoms. Above all, the book suggested what the microscope could do for biological science.

Wren and Hooke dominated and guided the work, and cemented a friendship that lasted throughout their lives. To Hooke the position of surveyor was a financial boon, more than compensating for the uncertainty of his other income.

... of compounding the celestiall motions of the planetts of a direct motion by the tangent ( inertial motion ) and an attractive motion towards the centrall body ... my supposition is that the Attraction always is in a duplicate proportion to the Distance from the Center Reciprocall ...

He was a brisk walker, and enjoyed walking in the fields north of the City. ... he generally rose early, perhaps to save candles, and to work in daylight and prevent strain to his eyes. ... Sometimes Hooke would work all through the night, and then have a nap after dinner. As well as drinking a variety of waters ... he drank brandy, port, claret, sack, and birch juice wine which he found to be delicious. He also had a barrel of Flanstead's ale and Tillotson's ale. There are a few instances when he recorded that he had been drunk ... He was a gregarious person, who liked to meet people, particularly those who had travelled abroad ...

.. often troubled with headaches, giddiness, and fainting, and with a general decay all over, which hindered his philosophical studies, yet he still read some lectures whenever he was able.

[ Huygens ' Preface ] is concerning those properties of gravity which I myself first discovered and showed to this Society and years since, which of late Mr Newton has done me the favour to print and publish as his own inventions. And particularly that of the oval figure of the Earth which was read by me to this Society about 27 years since upon the occasion of the carrying the pendulum clocks to sea and at two other times since, though I have had the ill fortune not to be heard, and I conceive there are some present that may very well remember and do know that Mr Newton did not send up that addition to his book till some weeks after I had read and showed the experiments and demonstration thereof in this place and had answered the reproachful letter of Dr Wallis from Oxford. However I am well pleased to find that the truth will at length prevail when men have laid aside their prepossessions and prejudices. And as that hath found approvers in the world and those thinking men too, so I doubt not but that divers other discoveries which I have here first made ( when they come to be well considered and examined ) be found not so unreasonable or extravagant as some would willingly make them.

... lean, bent and ugly man ...

References ( show )

- R S Westfall, Biography in Dictionary of Scientific Biography ( New York 1970 - 1990) . See THIS LINK .

- Biography in Encyclopaedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/biography/Robert-Hooke

- V I Arnol'd, Huygens and Barrow, Newton and Hooke. Pioneers in mathematical analysis and catastrophe theory from evolvents to quasicrystals ( Basel, 1990) .

- A N Bogolyubov, Robert Hooke 1635 - 1703 , Scientific-Biographic Literature 'Nauka' ( Moscow, 1984) .

- F F Centore, Robert Hooke's contributions to mechanics : a study in seventeenth century natural philosophy ( The Hague, 1970) .

- J G Crowther, Founders of British science : John Wilkins, Robert Boyle, John Ray, Christopher Wren, Robert Hooke, Isaac Newton ( London, 1960) .

- W Derham ( ed. ) , The Philosophical Works of Dr Robert Hooke ( London, 1726) .

- M Espinasse, Robert Hooke ( London, 1956) .

- M Hunter and S Schaffer ( eds. ) , Robert Hooke : new studies ( Eoodbridge, 1989) .

- R Nichols, The Diaries of Robert Hooke, The Leonardo of London, 1635 - 1703 ( Lewes, 1994) .

- R Waller ( ed. ) , The Postumous Works of Dr Robert Hooke ( London, 1705) .

- E N da C Andrade, Robert Hooke, Proc. Roy. Soc. London 201 A (1950) , 439 - 473 .

- J A Bennett, Robert Hooke as Mechanic and Natural Philosopher, Notes and Records of the Royal Society 35 (1980 - 1981) , 33 - 48 .

- J A Bennett, Hooke and Wren and the system of the world : some points towards an historical account, British J. Hist. Sci. 8 (1975) , 32 - 61 .

- A N Bogolyubov, Robert Hooke as a teacher of mathematics ( Russian ) , Istor.-Mat. Issled. 32 - 33 (1990) , 373 - 383 .

- C Dilworth, Boyle, Hooke and Newton : some aspects of scientific collaboration, Rend. Accad. Naz. Sci. XL Mem. Sci. Fis. Natur. (5) 9 (1985) , 329 - 331 .

- W N Edwards, Robert Hooke as a geologist and evolutionist, Nature 137 (1936) , 96 - 97 .

- M E Ehrlich, Mechanism and Activity in the Scientific Revolution : The Case of Robert Hooke, Annals of Science 52 (1995) , 127 - 152 .

- H Erlichson, Newton and Hooke on centripetal force motion, Centaurus 35 (1) (1992) , 46 - 63 .

- S R Filonovich, Astronomy in the work of Robert Hooke ( on the occasion of the 350 th anniversary of his birth ) ( Russian ) , Istor.-Astronom. Issled. 18 (1986) , 259 - 290 .

- O Gal, Producing knowledge in the workshop : Hooke's 'inflection' from optics to planetary motion, Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. 27 (2) (1996) , 181 - 205 .

- D C Goodman, Robert Hooke, 1635 - 1703 , in Late seventeenth century scientists ( Oxford, 1969) , 132 - 157 .

- P Gouk, The Role of Acoustics and Music Theory in the Scientific Work of Robert Hooke, Annals of Science 37 (1980) , 573 - 605 .

- A R Hall, Robert Hooke and horology, Notes and Records Roy. Soc. London 8 (1) (1950 - 51) , 167 - 177 .

- A R Hall, Beyond the fringe : diffraction as seen by Grimaldi, Fabri, Hooke and Newton, Notes and Records Roy. Soc. London 44 (1) (1990) , 13 - 23 .

- A R Hall, Two unpublished lectures of Robert Hooke, Isis 42 (1951) , 219 - 230 .

- A R Hall, Horology and criticism : Robert Hooke, in Studia Copernicana 16 - Science and history ( Ossolinskich, 1978) , 261 - 281 .

- M Hesse, Hooke's philosophical algebra, Isis 57 (1966) , 67 - 83 .

- M Hesse, Hooke's vibration theory and the isochrony of springs, Isis 57 (1966) , 433 - 441 .

- P E B Jourdain, Robert Hooke as a precursor of Newton, Monist 23 (1913) , 353 - 385 .

- J C Kassler and D R Oldroyd, Robert Hooke's Trinity College 'Musick Scripts', his music theory and the role of music in his cosmology, Ann. of Sci. 40 (6) (1983) , 559 - 595 .

- V S Kirsanov, The correspondence between Isaac Newton and Robert Hooke : 1679 - 80 ( Russian ) , Voprosy Istor. Estestvoznan. i Tekhn. (4) (1996) , 3 - 39 , 173 .

- A Koyré, A note on Robert Hooke, Isis 41 (1950) , 195 - 196 .

- A Koyré, An unpublished letter of Robert Hooke to Isaac Newton, Isis 43 (1952) , 312 - 337 .

- R Lehti, Newton's road to classical dynamics. II. Robert Hooke's influence on Newton's dynamics ( Finnish ) , Arkhimedes 39 (1) (1987) , 18 - 51 .

- J Lohne, Hooke versus Newton : An analysis of the documents in the case on free fall and planetary motion, Centaurus 7 (1960) , 6 - 52 .

- W S Middleton, The Medical Aspect of Robert Hooke, Annals of Medical History 9 (1927) , 227 - 43 .

- H Nakajima, Two kinds of modification theory of light : some new observations on the Newton-Hooke controversy of 1672 concerning the nature of light, Ann. of Sci. 41 (3) (1984) 261 - 278 .

- M Nauenberg, Hooke, orbital dynamics and Newton's Principia, American Journal of Physics 62 (1994) , 331 - 350 .

- L D Patterson, Hooke's gravitation theory and its influence on Newton I, Isis 40 (1949) , 327 - 341 .

- L D Patterson, Hooke's gravitation theory and its influence on Newton II, Isis 41 (1950) , 23 - 45 .

- A P Rossiter, The first English geologist, Durham University Journal 27 (1935) , 172 - 181 .

- E G R Taylor, Robert Hooke and the Cartographical Projects of the Late Seventeenth Century, Geographical Journal 9 (1937) , 529 - 540 .

- R S Westfall, Hooke and the law of universal gravitation, British J. Hist. Sci. 3 (1967) , 245 - 261 .

- R S Westfall, The development of Newton's theory of colour, Isis 53 (1962) , 339 - 358 .

Additional Resources ( show )

Other pages about Robert Hooke:

- Aubrey's Brief Lives

- Multiple entries in The Mathematical Gazetteer of the British Isles ,

- Astronomy: The Dynamics of the Solar System

Other websites about Robert Hooke:

- Dictionary of Scientific Biography

- Dictionary of National Biography

- Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Robert Hooke home page

- The Galileo Project,

- Sci Hi blog

- Robert Hooke's London

- Mathematical Genealogy Project

- zbMATH entry

Honours ( show )

Honours awarded to Robert Hooke

- Fellow of the Royal Society 1663

- Lunar features Crater Hooke

- Biography in Aubrey's Brief Lives

- Lunar features Crater Hooke on Mars

- Popular biographies list Number 42

Cross-references ( show )

- History Topics: A history of the calculus

- History Topics: A history of time: Classical time

- History Topics: English attack on the Longitude Problem

- History Topics: Light through the ages: Ancient Greece to Maxwell

- History Topics: London Coffee houses and mathematics

- History Topics: Mathematics and Architecture

- History Topics: Orbits and gravitation

- History Topics: Science in the 17 th century: From Europe to St Andrews

- History Topics: The development of the 'black hole' concept

- Societies: London Royal Society

- Other: 10th April

- Other: 15th February

- Other: 19th February

- Other: 2009 Most popular biographies

- Other: 21st January

- Other: 25th August

- Other: 3rd June

- Other: Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics (E)

- Other: Jeff Miller's postage stamps

- Other: London Learned Societies

- Other: London Miscellaneous

- Other: London Museums

- Other: London Schools

- Other: London Scientific Institutions

- Other: London individuals H-M

- Other: London individuals S-Z

- Other: Most popular biographies – 2024

- Other: Other London Institutions outside the centre

- Other: Oxford Institutions and Colleges

- Other: Oxford individuals

- Other: Popular biographies 2018

- Other: The Dynamics of the Solar System

Robert Hooke: The ‘English Leonardo’ who was a 17th-century scientific superstar

Chancellor's Professor of Medicine, Liberal Arts, and Philanthropy, Indiana University

Disclosure statement

Richard Gunderman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Indiana University provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Considering his accomplishments, it’s a surprise that Robert Hooke isn’t more renowned. As a physician, I especially esteem him as the person who identified biology’s most essential unit, the cell.

Like Leonardo da Vinci , Hooke excelled in an incredible array of fields. The remarkable range of his achievements throughout the 1600s encompassed pneumatics, microscopy, mechanics, astronomy and even civil engineering and architecture. Yet this “ English Leonardo ” – well-known in his time – slipped into relative obscurity for several centuries.

His life and times

Hooke’s life is a rags-to-riches tale. Born in 1635, he was educated at home by his clergyman father. Orphaned at 13 with a meager inheritance, Hooke’s artistic talents landed him scholarships to Westminster School and later Oxford University. There he formed relationships with a variety of important people, most notably Robert Boyle . Hooke became the laboratory assistant of this great chemist – the formulator of Boyle’s law, which describes the inverse relation between the pressure and volume of gases.

Unlike his associates, Hooke was not a man of independent means, and he soon took a paying position as “curator of experiments” at the newly formed Royal Society , making him England’s first salaried scientific researcher. Hooke soon became a fellow of the Royal Society and was appointed to a professorship at Gresham College.

Never marrying, he dwelt the rest of his life in rooms near the Royal Society’s meeting place. This placed him at the epicenter of one of the most important epochs in the history of science, epitomized by the publication of Isaac Newton’s “ Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy .”

Experiments and innovations

For millennia before Hooke, people had regarded air, along with fire, water and earth, as one of the four elemental substances that filled the world, leaving no empty spaces. Working with Boyle, Hooke developed a vacuum pump that could empty space. In a vessel so evacuated, a candle couldn’t burn, and a clapping bell was silent, proving that air is necessary for combustion and conducting sound.

Moreover, Hooke showed that air could be expanded and compressed. He also performed foundational experiments on the relationship between air and the process of respiration in living organisms. And he laid the groundwork for thermodynamics, by suggesting that particles in matter move faster as they heat up.

Hooke’s most famous work is his beautifully illustrated “ Micrographia ,” published in 1665. The microscope had been invented 30 years before his birth. Hooke vaulted the technology forward, using an oil lamp as a light source and a water lens to focus its beams in order to enhance visualization.

He showed that the realm of the very small is as rich and complex and the one that meets the naked eye. Inspecting the structure of cork through his instrument, he named the units he saw cells, after the rooms of monks. Biologists now know that a human body contains approximately 40 trillion of them. From his microscope work, Hooke also developed a wave theory of light.

Hooke pondered some of the biggest biological questions as well. He hypothesized that the presence of fossilized fish in mountainous areas meant they had once been under water. His study of fossils led him to conclude that the Earth has been inhabited by many extinct species.

Hooke’s experiments with mechanical springs led to the formulation of Hooke’s Law , which states that the tension or compression of a spring is proportional to the force applied to it. Physicists now know that this law applies not only to springs but also to a variety of solid elastic bodies, such as manometers, which are used to measure pressure.

These same investigations also enabled him to invent the spring-powered balance watch , which would become a favorite means of keeping time for centuries. Hooke foresaw that with a precise timepiece, oceangoing sailors could find their longitude.

As an astronomer , Hooke suggested that the planet Jupiter rotates, described the center of gravity of the Earth and Moon, illustrated lunar craters and speculated on their origin, discovered a double star and illustrated the Pleiades star cluster.

At a more theoretical level, Hooke also described gravity as the force that pulls celestial bodies together, relating in a 1679 letter to Newton a version of the inverse-square law of gravitational force. When seven years later Newton published his great work “Mathematical Principles,” Hooke concluded incorrectly that Newton – who had already been at work on it at the time of their correspondence – had slighted him.

Contributions to his city

The great fire of London in 1666 presented another opportunity for Hooke to shine. Unlike many contemporaries, he refused to profit dishonestly in the aftermath of the disaster by taking bribes as people worked to rebuild. As surveyor of the city , he collaborated with the renowned architect Christopher Wren to create a monument to the fire .

He also designed a number of great buildings , including Bethlem Hospital (known as Bedlam), the Royal Greenwich Observatory and the Royal College of Physicians. It was in large part through his architectural work that Hooke made his fortune, though he never veered from the frugal habits he developed early in life. Hooke even proposed recreating London’s streets on a grid pattern. Though unsuccessful, his idea was subsequently incorporated in cities such as Liverpool and Washington, D.C.

Surveying the range and depth of Hooke’s contributions, it’s difficult to believe that one person could have accomplished so much in 67 years. Unfortunately, his sometimes rancorous disputes with the likes of Newton over scientific priority contributed to his comparative neglect by science historians , and today we lack any contemporary likeness of him. His birthday is a good time to give him his due as one of the world’s all-time great instrument makers, experimentalists and polymaths.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter . ]

- History of science

- Royal Society

- Robert Hooke

Head, School of Psychology

Senior Lecturer (ED) Ballarat

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

. . . I could exceedingly plainly perceive it to be all perforated and porous, much like a Honey-comb, but that the pores of it were not regular. . . . these pores, or cells, . . . were indeed the first microscopical pores I ever saw, and perhaps, that were ever seen, for I had not met with any Writer or Person, that had made any mention of them before this. . .

this petrify'd Wood having lain in some place where it was well soak'd with petrifying water (that is, such water as is well impregnated with stony and earthy particles) did by degrees separate abundance of stony particles from the permeating water, which stony particles, being by means of the fluid vehicle convey'd, not onely into the Microscopical pores. . . but also into the pores or Interstitia. . . of that part of the Wood, which through the Microscope, appears most solid. . .

December 1, 1954

Robert Hooke

This 17th-century Englishman was a prodigious scientist and inventor. To mention a few of his achievements, he made basic contributions to physics, chemistry, meteorology, geology, biology and astronomy

By E. N. da C. Andrade

- News/Events

- Arts and Sciences

- Design and the Arts

- Engineering

- Global Futures

- Health Solutions

- Nursing and Health Innovation

- Public Service and Community Solutions

- University College

- Thunderbird School of Global Management

- Polytechnic

- Downtown Phoenix

- Online and Extended

- Lake Havasu

- Research Park

- Washington D.C.

- Biology Bits

- Bird Finder

- Coloring Pages

- Experiments and Activities

- Games and Simulations

- Quizzes in Other Languages

- Virtual Reality (VR)

- World of Biology

- Meet Our Biologists

- Listen and Watch

- PLOSable Biology

- All About Autism

- Xs and Ys: How Our Sex Is Decided

- When Blood Types Shouldn’t Mix: Rh and Pregnancy

- What Is the Menstrual Cycle?

- Understanding Intersex

- The Mysterious Case of the Missing Periods

- Summarizing Sex Traits

- Shedding Light on Endometriosis

- Periods: What Should You Expect?

- Menstruation Matters

- Investigating In Vitro Fertilization

- Introducing the IUD

- How Fast Do Embryos Grow?

- Helpful Sex Hormones

- Getting to Know the Germ Layers

- Gender versus Biological Sex: What’s the Difference?

- Gender Identities and Expression

- Focusing on Female Infertility

- Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and Pregnancy

- Ectopic Pregnancy: An Unexpected Path

- Creating Chimeras

- Confronting Human Chimerism

- Cells, Frozen in Time

- EvMed Edits

- Stories in Other Languages

- Virtual Reality

- Zoom Gallery

- Ugly Bug Galleries

- Ask a Question

- Top Questions

- Question Guidelines

- Permissions

- Information Collected

- Author and Artist Notes

- Share Ask A Biologist

- Articles & News

- Our Volunteers

- Teacher Toolbox

show/hide words to know

Bubonic plague: bacterial disease carried by fleas of infected Old English rats. At its worst, it killed two million people a year. Those that caught the disease had a 90% chance of dying from it.

Great Plague of London: there have been several large outbreaks of the bubonic plague in Europe beginning in 1347. In 1665 London fell victim to the plague that has since been called the Great Plague of London... more

Microscope: an instrument used to see objects or parts of objects, which are too small to be seen with only our eyes... more

Robert Hooke (28 July 1635 – 3 March 1703)

The cover of Robert Hooke's Micrographia , published in 1665. In addition to illustrations of insects, snowflakes, and his famous slice of cork, he also described how to make a microscope like the one he used.

The year was 1665. A book of illustrations called Micrographia has just been published by the English natural philosopher, Robert Hooke. The camera had not yet been invented so illustrations were common for books and other publications. What was uncommon about Micrographia was that it was one of the first time drawings of the microscopic world had been published.

Within the publication more than 30 detailed illustrations appeared including the famous one from cork that provided the first documentation of a single cell. Hooke also examined hair under a microscope and made a note that some of the hairs were split at the ends. This is possibly the first notation of split ends.

Examples of Hooke's detailed drawings can be seen in the illustration of a cork and a flea below. It was in his description of cork that he first used the term "cell" even though he did not know how important his discovery would become. The cell wasn't really understood until 1839 when scientists began to discover its importance.

Why Call it a Cell?

Hooke's drawings show the detailed shape and structure of a thinly sliced piece of cork. When it came time to name these chambers he used the word 'cell' to describe them, because they reminded him of the bare wall rooms where monks lived. These rooms were called cells.

Gallery of Images from Micrographia

There were no cameras when Robert Hooke first explored the tiny world with his microscope. To bring these images to life and share them with the world, he had to draw what he saw using his new instrument. Here are a few of the amazing drawings he made and published in 1665.

Additional places to explore:

Read Micrographia and view all the images at eBooks@Adelaide .

References:

Historical Anatomies on the Web (NIH).

Scanning Electron Image of the flea from the Center for Disease Control (CDC)

Image of the scanning electron microscope snowflake from Beltsville Electron Microscopy Unit, part of the USDA .

Additional images from Wikimedia Commons.

Read more about: Building Blocks of Life

View citation, bibliographic details:.

- Article: Robert Hooke

- Author(s): Shyamala Iyer

- Publisher: Arizona State University School of Life Sciences Ask A Biologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask A Biologist

- Date published: September 24, 2009

- Date accessed: May 21, 2024

- Link: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/robert-hooke

Shyamala Iyer. (2009, September 24). Robert Hooke. ASU - Ask A Biologist. Retrieved May 21, 2024 from https://askabiologist.asu.edu/robert-hooke

Chicago Manual of Style

Shyamala Iyer. "Robert Hooke". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 24 September, 2009. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/robert-hooke

MLA 2017 Style

Shyamala Iyer. "Robert Hooke". ASU - Ask A Biologist. 24 Sep 2009. ASU - Ask A Biologist, Web. 21 May 2024. https://askabiologist.asu.edu/robert-hooke

Building Blocks of Life

Coloring Pages and Worksheets

Animal Cell

Bacterial Cell

Fungal Cell

Be Part of Ask A Biologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a Volunteers page to get the process started.

Share to Google Classroom

- Previous Article

- Next Article

The Forgotten Genius: The Biography of Robert Hooke 1635–1703

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Reprints and Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Peter Dear; The Forgotten Genius: The Biography of Robert Hooke 1635–1703 . Physics Today 1 February 2005; 58 (2): 66–68. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2405556

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

The Forgotten Genius: The Biography of Robert Hooke 1635–1703 , Stephen Inwood MacAdam/Cage , San Francisco , 2003 . $28.50 ( 482 pp.). ISBN 1-931561-56-7 Google Scholar

Robert Hooke has never really been forgotten. But he is usually remembered only as a peripheral figure of the scientific revolution, famous for his controversies with the great Isaac Newton or, especially in Great Britain, for being a minor colleague of Christopher Wren, the architect of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London who also rebuilt the city after the great fire of 1666. The Curious Life of Robert Hooke: The Man Who Measured London by Lisa Jardine and The Forgotten Genius: The Biography of Robert Hooke 1635–1703 by Stephen Inwood are both biographies by British authors, and Jardine’s book in particular reminds us of Hooke’s major, albeit overshadowed, role in that astonishing rebuilding effort. He would have been much better remembered had he received the kind of hagiographical treatment after his death that so benefited Wren.

Hooke was a founding member of the Royal Society when it received its final royal authorization in 1663. He was its lifeblood for many years, the one who made it much more than just a talking shop. He was appointed the society’s first “curator of experiments,” charged with producing experimental demonstrations for the group’s discussions at each weekly meeting. Hooke received the post after being Robert Boyle’s experimental technician in Oxford for several years; he built Boyle’s air pumps and probably was responsible for the initial formulation of Boyle’s law. (Hooke’s law, of course, is itself well known to engineers and physicists.)

Hooke published on many topics and left a large collection of manuscripts on many others, including geology, astronomy, watchmaking, gravity, chemistry, mechanics, and microscopy. His interest in microscopy in particular produced his greatest lasting legacy: Micrographia, or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies made by Magnifying Glasses of 1665. That book is perhaps best known for its huge fold-out engraving of a magnified flea, an image that is frequently reproduced without attribution. The magnificent illustrations, some perhaps due to Hooke’s friend and colleague Wren, ensured the book’s success. It was the book’s textual contents, however, that laid the foundation for Hooke’s contemporary reputation. His discussion of the nature of light and color caught the attention of the young Newton—Hooke first described “Newton’s rings” in Micrographia —and set the stage for the controversy between him and Newton in the 1670s after Newton published his own ideas on the same subject.

Readers interested in learning more about Hooke and this controversy with Newton, and about Micrographia , may be disappointed by Jardine’s book. Jardine evidently intended that her book join the ranks of the countless “The Man Who …” books whose many subjects “changed the world,” following the example of the 1995 biography Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time (Walker, 1995) by Dava Sobel. Although Jardine begins with a theme-setting account of Hooke’s battle for credit when Newton’s Principia was published, her narrative provides no discussion of the optical controversy between the two men and, more surprisingly, no real discussion of Micrographia and its contents. Inwood’s The Forgotten Genius , on the other hand, dedicates several pages to each of the famous controversies and an entire chapter (although of modest length) to the Micrographia. His book discusses many of Hooke’s scientific and technical innovations, including all of the major ones, whereas Jardine often mentions them only in passing.

The focus of Jardine’s book is on Hooke as a social being who moves around London consorting with people of many different sorts and social classes, from lords to laborers. Even before his intensive work on the surveying and rebuilding of London after the fire, Hooke appears in a variety of settings, from bookshops to the court of Charles II. He is most typically seen in coffeehouses, a new feature of London life in the 1660s that Hooke took to like a duck to water, where he could meet with Royal Society colleagues, mathematical instrument makers, and sailors. His technical and intellectual capacities, combined with his social skills, recommended him to the City of London as a practical surveyor. The appointment, together with his work for Wren’s architectural firm, made him the single most significant figure in the grand project for rebuilding London, an enterprise whose swiftness amazed foreign visitors. It is in Jardine’s accounts of this period of Hooke’s life, rather than in her accounts of his scientific labors, that Hooke really comes alive.

A feature that recommends Hooke to biographers is the existence of his famous diaries, which both Jardine and Inwood use well. The diaries sketch out the business of Hooke’s everyday life, the breadth of his social acquaintance, and the details of his domestic existence. Jardine and Inwood both discuss his constant concerns with his health and with medical remedies, few of which seemed to have done much good. The diaries are also the source for what historians know about his sex life, without which no biography is nowadays complete.

Jardine’s book is lavishly illustrated and is more appealing to the eye. Inwood’s, by contrast, is comfortable and old-fashioned and takes its biographical task seriously, proceeding largely chronologically and trying not to leave out important events in the course of Hooke’s life. Jardine attempts more vigorously to develop themes, such as the long-lasting importance of Hooke’s childhood in the Isle of Wight. His early years on the island seem to have shaped his later geological ideas and provided social connections (including sources of servants) that continued to be important to him until the end.

Anyone seriously interested in Hooke has, in addition to Jardine’s and Inwood’s books, plenty of specialized scholarly work available. The layperson who wants to learn something about Hooke’s tremendously inventive scientific career would do well to start with Inwood, whereas the reader who is interested in the social and cultural life of later 17th-century London will profit much from Jardine’s colorful and insightful book.

Citing articles via

- Online ISSN 1945-0699

- Print ISSN 0031-9228

- For Researchers

- For Librarians

- For Advertisers

- Our Publishing Partners

- Physics Today

- Conference Proceedings

- Special Topics

pubs.aip.org

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Connect with AIP Publishing

This feature is available to subscribers only.

Sign In or Create an Account

History of the Cell: Discovering the Cell

Initially discovered by Robert Hooke in 1665, the cell has a rich and interesting history that has ultimately given way to many of today’s scientific advancements.

Biology, Genetics

Loading ...

Although they are externally very different, internally, an elephant, a sunflower, and an amoeba are all made of the same building blocks. From the single cells that make up the most basic organisms to the trillions of cells that constitute the complex structure of the human body, each and every living being on Earth is comprised of cells . This idea, part of the cell theory, is one of the central tenants of biology . Cell theory also states that cells are the basic functional unit of living organisms and that all cells come from other cells . Although this knowledge is foundational today, scientists did not always know about cells .

The discovery of the cell would not have been possible if not for advancements to the microscope . Interested in learning more about the microscopic world, scientist Robert Hooke improved the design of the existing compound microscope in 1665. His microscope used three lenses and a stage light, which illuminated and enlarged the specimens. These advancements allowed Hooke to see something wondrous when he placed a piece of cork under the microscope . Hooke detailed his observations of this tiny and previously unseen world in his book, Micrographia . To him, the cork looked as if it was made of tiny pores, which he came to call “cells” because they reminded him of the cells in a monastery.

In observing the cork’s cells, Hooke noted in Micrographia that, “I could exceedingly plainly perceive it to be all perforated and porous, much like a Honey-comb, but that the pores of it were not regular… these pores, or cells,…were indeed the first microscopical pores I ever saw, and perhaps, that were ever seen, for I had not met with any Writer or Person, that had made any mention of them before this…”

Not long after Hooke’s discovery, Dutch scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek detected other hidden, minuscule organisms— bacteria and protozoa . It was unsurprising that van Leeuwenhoek would make such a discovery. He was a master microscope maker and perfected the design of the simple microscope (which only had a single lens), enabling it to magnify an object by around two hundred to three hundred times its original size. What van Leeuwenhoek saw with these microscopes was bacteria and protozoa , but he called these tiny creatures “animalcules.”

Van Leeuwenhoek became fascinated. He went on to be the first to observe and describe spermatozoa in 1677. He even took a look at the plaque between his teeth under the microscope. In a letter to the Royal Society, he wrote, "I then most always saw, with great wonder, that in the said matter there were many very little living animalcules, very prettily a-moving.”

In the nineteenth century, biologists began taking a closer look at both animal and plant tissues, perfecting cell theory. Scientists could readily tell that plants were completely made up of cells due to their cell wall. However, this was not so obvious for animal cells, which lack a cell wall. Many scientists believed that animals were made of “globules.”

German scientists Theodore Schwann and Mattias Schleiden studied cells of animals and plants respectively. These scientists identified key differences between the two cell types and put forth the idea that cells were the fundamental units of both plants and animals.

However, Schwann and Schleiden misunderstood how cells grow. Schleiden believed that cells were “seeded” by the nucleus and grew from there. Similarly, Schwann claimed that animal cells “crystalized” from the material between other cells. Eventually, other scientists began to uncover the truth. Another piece of the cell theory puzzle was identified by Rudolf Virchow in 1855, who stated that all cells are generated by existing cells.

At the turn of the century, attention began to shift toward cytogenetics, which aimed to link the study of cells to the study of genetics. In the 1880s, Walter Sutton and Theodor Boveri were responsible for identifying the chromosome as the hub for heredity —forever linking genetics and cytology. Later discoveries further confirmed and solidified the role of the cell in heredity , such as James Watson and Francis Crick’s studies on the structure of DNA .

The discovery of the cell continued to impact science one hundred years later, with the discovery of stem cells , the undifferentiated cells that have yet to develop into more specialized cells . Scientists began deriving embryonic stem cells from mice in the 1980s, and in 1998, James Thomson isolated human embryonic stem cells and developed cell lines. His work was then published in an article in the journal Science . It was later discovered that adult tissues, usually skin, could be reprogrammed into stem cells and then form other cell types. These cells are known as induced pluripotent stem cells . Stem cells are now used to treat many conditions such as Alzheimer’s and heart disease.

The discovery of the cell has had a far greater impact on science than Hooke could have ever dreamed in 1665. In addition to giving us a fundamental understanding of the building blocks of all living organisms, the discovery of the cell has led to advances in medical technology and treatment. Today, scientists are working on personalized medicine, which would allow us to grow stem cells from our very own cells and then use them to understand disease processes. All of this and more grew from a single observation of the cell in a cork.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Hooke, Robert

- Reference work entry

- Cite this reference work entry

- Ellen Tan Drake

Born Freshwater, Isle of Wight, England, 18 July 1635

Died London, England, 3 March 1703

Robert Hooke was one of the foremost experimenters of the 17th century and a remarkable inventor of astronomical instruments. He was among the first to suggest the inverse‐square law of gravitation and the periodicity of comets.

Hooke was the son of John Hooke, curate of All Saints Church in Freshwater, and his second wife Cicely Giles. A sickly child, he was not expected to survive childhood.

At a young age Hooke showed artistic and mechanical talent; he could draw and paint and build wooden models of machines that worked. When he was 13, his father died, and Hooke was sent to London to be apprenticed to the portrait painter Sir Peter Lely, but the odor of the oil paint made him sick. He was then sent to Westminster School. The headmaster, Dr. Busby, immediately recognized the boy's genius when Hooke learned the first six books of Euclid in a week, taught himself to play the organ, and learned...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Selected References

Bennett, J. A. et al. (2003). London's Leonardo: The Life and Work of Robert Hooke . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Espinasse, Margaret (1962). Robert Hooke . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jardine, Lisa (2004). The Curious Life of Robert Hooke: The Man Who Measured London . New York: HarperCollins.

Tan Drake, Ellen (1996). Restless Genius: Robert Hooke and His Earthly Thoughts . New York: Oxford University Press.

Westfall, Richard S. (1967). “Hooke and the Law of Universal Gravitation: A Reappraisal of a Reappraisal.” British Journal for the History of Science 3: 245–261.

Article MATH Google Scholar

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Earth Science, University of Northern Iowa, Office: Latham 112, 50614, Cedar Falls, IA, USA

Thomas Hockey ( Professor of Astronomy ) ( Professor of Astronomy )

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2007 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Drake, E. (2007). Hooke, Robert. In: Hockey, T., et al. The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-30400-7_646

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-30400-7_646

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-0-387-31022-0

Online ISBN : 978-0-387-30400-7

eBook Packages : Physics and Astronomy Reference Module Physical and Materials Science Reference Module Chemistry, Materials and Physics

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory