An official website of the United States government.

Here’s how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- 中文(简体) (Chinese-Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese-Traditional)

- Kreyòl ayisyen (Haitian Creole)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- Español (Spanish)

- Filipino/Tagalog

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Safety Management

Recommended Practices for Safety and Health Programs

Case studies.

To help start or improve your organization's safety and health program, see the case studies listed below for lessons learned and best practices.

- The Electric Power Industry relies on Safety and Health Programs to keep workers safe on the job ( PDF )

- Hazards that OSHA's voluntary On-Site Consultation Program helped companies identify.

- Methods companies implemented to correct the hazards.

- Business practices that changed to prevent injuries and illnesses.

- Challenges, successes, and overall impact on businesses.

- More than 60 success stories from 2008 through 2016 are presented from a wide range of industries throughout the country.

- You can read stories highlighting successes and best practices from companies participating in VPP – 21 recent stories arranged by industry - as well as 26 archived stories from 1994 to 2010 .

- Read about "CEOs Who Get It":

- 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009

- Noble Corporation

- Johnson and Johnson

- DM Petroleum Operations

- Fluor Hanford

- Schneider Electric

- Dow Chemical

Download

Recommended Practices for Safety and Health Programs (en Español) Download

Recommended Practices for Safety and Health Programs in Construction Download

EHS Daily Advisor

Practical EHS Tips, News & Advice. Updated Daily.

Injuries and Illness

Case studies in safety: a great training tool.

Updated: Nov 6, 2011

Case studies are a great safety training tool. It’s like CSI. Employees can really get involved examining the evidence and seeing why an accident occurred.

Safety case studies are fun, challenging, interactive, and a highly effective training method.

Armed with the knowledge they gain from examining the facts of real workplace accidents, workers can learn how to avoid similar incidents and injuries.

Here’s an example of such a case from BLR’s OSHA Accident Case Studies . This case is about a confined space incident.

The Incident

Two employees arrived at concrete pit at demolition site where they’d been working to salvage the bottom part of a cardboard baler imbedded in the pit. When the employees uncovered the pit, they both felt a burning sensation in their eyes.

Employee #1 climbed down into the pit to determine what might be causing their eyes to burn. He immediately climbed back out of the pit because it was hot. He decided to put a water hose into the pit to help cool it down.

The employees climbed down into the pit with the water hose. Both employees experienced chest tightness, difficulty breathing, and burning eyes. They decided to exit the pit because of the intolerable conditions.

Employee #2 climbed out first. As Employee #1 was climbing the ladder to get out, he was overcome by the fumes and fell back into the pit. He landed on his back, unconscious.

Employee #2 climbed down into the pit in an attempt to rescue employee #1, but was unable to lift him. Employee #2 exited the pit in order to get help. Unfortunately, by the time help arrived, Employee #1 had died of asphyxiation.

The accident investigation determined that employee #1 had attempted to extinguish a small cutting torch fire the day before by covering it with sand and dirt. Apparently the fire was not extinguished and smoldered overnight, which resulted in a build up of carbon monoxide inside the pit.

Try OSHA Accident Case Studies and give a boost to your safety training program with real-life case studies of actual industrial accidents from OSHA files. We have a great one on lifting. Get the details.

Discussion Questions

Once the case has been presented, some discussion questions can help kick off the analysis of the incident. For example:

- What are the potential hazards of confined spaces?

- What was the specific hazard in this case that cause a fatality?

- Were these workers properly trained and equipped to enter a confined space?

- What type of air monitoring should be done before entering a confined space?

- Was this a permit-required confined space? If so, were the workers familiar with the safety requirements of the permit?

- Was confined space rescue equipment readily accessible?

- Training? There is no indication on the accident report that the employees were trained as authorized entrants of confined spaces. If they did receive any confined space entry training, they clearly didn’t apply what they learned. Authorized entrants are trained on the hazards of confined spaces, atmosphere testing procedures, symptoms of lack of oxygen or exposure to toxic chemicals, personal protective equipment (PPE), communication equipment, rescue retrieval equipment, etc.

- Hazard warning? These employees entered the space despite experiencing "red flags," such burning eyes and unusual heat. An important part of training for confined space workers includes learning about hazards such as the symptoms of a lack of oxygen or exposure to toxic chemicals. Workers should never enter a space, and should immediately leave a space, in which they experience signs of hazardous conditions.

Even your most skeptical workers will see what can go wrong and become safety-minded employees with OSHA Accident Case Studies . They’ll learn valuable safety training lessons from real mistakes—but in classroom training meetings instead of on your shop floor. Get more info.

- Permit-required? Most confined spaces require a permit before workers can enter the space. Permit-required confined spaces have the potential for hazards such as hazardous atmospheres, engulfment, entrapment, falls, heat, combustibility, etc. By reviewing a permit, entrants know they have obtained all the necessary equipment and the atmosphere has been monitored so they know the space is safe to enter.

- Testing? This worker died of asphyxiation, or lack of oxygen. If the atmosphere in the pit had been tested prior to entry, this accident would not have occurred. Common monitoring practices require a check of the oxygen concentration, a check for flammable gases or vapors (especially important if welding is going to be done in the space), and finally, a check for any other toxic chemicals known to potentially be in the space. Monitoring is conducted before entering the space and periodically while workers are in the space.

- Rescue procedures and equipment? The worker who collapsed back into the pit while climbing out could not be rescued because he was not wearing required rescue equipment. He should have been wearing a full-body harness attached to a retrieval line that was connected to a winch-type system that could have been used to pull the unconscious worker out of the pit. Of course, the other employee would have had to have been trained in confined space rescue procedures.

Tomorrow, we’ll introduce you to another case from OSHA Accident Case Studies, this one about a materials handling accident that resulted in a serious back injury.

More Articles on Injuries and Illness

1 thought on “case studies in safety: a great training tool”.

PingBack from http://savant7.com/workaccidentreport/workplace-safety/case-studies-train-employees-to-look-for-accident-causes-and-prevention/

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- +91-7665231743

- +91-9413882016

- [email protected]

BBSM Case Studies: Real-Life Examples of Successful Safety Improvements

Understanding the Risks and Precautions of Handling Hydrogen in Industrial Environments

Achieving cpd certification through bbsm training: what it means for safety professionals.

- Uncategorized

- fire safety audit

- Safety consultant in India

Behavior-Based Safety

Behavior-Based Safety Management (BBSM) has emerged as a powerful approach to enhancing workplace safety by focusing on individual behaviors and their impact on safety outcomes. Through the analysis of real-life case studies, we will explore how organizations have successfully implemented BBSM to achieve significant safety improvements. In this context, we will also delve into the commendable efforts of the Safety Master in providing the best Behavior-Based Safety Training, encompassing essential aspects such as Fire Audit, Behavior-Based Safety Training, and BBS Implementation.

Case Study 1: Behavior-Based Safety Implementation in Indian Organizations

The study conducted in five major Indian organizations provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of BBSM in improving safety behaviors and reducing unsafe practices. The research revealed that prior to BBS implementation, safe behaviors were observed at 70%, while unsafe behaviors accounted for 30%, resulting in a 67% correction rate. However, after corrective measures were introduced, safe behaviors surged to an impressive 90%.

Key takeaways:

– BBSM can have a significant positive impact on safety performance by identifying and correcting unsafe behaviors.

– The study emphasizes the crucial role of organizational culture in shaping employee behaviors related to safety.

– Effective BBSM can lead to the development of a total safety culture by addressing various organizational behavior domains.

Case Study 2: Fire Audit and Behavior-Based Safety Training

In this case study, a company underwent a comprehensive Fire Audit to identify potential fire hazards and safety gaps. The findings from the audit were utilized to design a targeted Behavior-Based Safety Training program. The training focused on educating employees about fire safety protocols, proper handling of equipment, and emergency response procedures.

Key outcomes:

– Through the Behavior-Based Safety Training program, employees became more aware of fire safety measures and demonstrated improved adherence to safety protocols.

– The training created a safety-conscious environment where employees actively participated in identifying potential fire hazards and taking preventive actions.

– The combination of Fire Audit and Behavior-Based Safety Training led to a significant reduction in fire-related incidents and injuries.

Case Study 3: Successful BBS Implementation in Manufacturing Industry

A manufacturing company successfully implemented BBSM as part of its safety improvement initiative. The Safety Master played a pivotal role in guiding the organization through the entire process. The implementation included the establishment of a Behavior-Based Safety Steering Committee, conducting safety observations, providing feedback, and recognizing positive safety behaviors.

Key achievements:

– The Behavior-Based Safety Steering Committee ensured that BBSM activities were integrated into the company’s safety culture.

– Regular safety observations and feedback sessions facilitated the continuous improvement of safety behaviors among employees.

– Positive reinforcement and recognition of safe behaviors enhanced employee motivation and engagement in safety practices.

Conclusion:

The provided case studies demonstrate the tangible benefits of implementing Behavior-Based Safety Management in various industries. By addressing organizational culture, providing targeted training, and utilizing safety audits, organizations can achieve remarkable safety improvements. The expertise of the Safety Master in delivering effective BBS training plays a crucial role in guiding organizations toward a total safety culture, where employees prioritize safety in every aspect of their work.

As organizations continue to prioritize safety and invest in Behavior-Based Safety Management, they pave the way for a safer and more productive work environment.

Sanjeev Kumar Paruthi

Director & CEO

TSM TheSafetyMaster® Private Limited

Unit No 221-451-452, SPL1/J, 2 nd & 4 th Floor, Sunsquare Plaza Complex, RIICO Chowk, Bhiwadi 301019, Rajasthan, India

Phone: +91 1493 22 0093

Mobile: +91 7665231743/9413882016

Email: [email protected]

www.thesafetymaster.com

TheSafetyMaster

Related posts.

ISO45001 or ISO14001 System Implementation – The Safety Master

Forklift training: advanced techniques for enhanced efficiency and productivity in the workplace.

Electrical Safety Audit – The Safety Master: Identifying & Addressing Common Electrical Hazards

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

- 14 Jul 2022

- Research & Ideas

When the Rubber Meets the Road, Most Commuters Text and Email While Driving

Laws and grim warnings have done little to deter distracted driving. Commuters routinely use their time behind the wheel to catch up on emails, says research by Raffaella Sadun, Thomaz Teodorovicz, and colleagues. What will it take to make roads safer?

- 15 Mar 2022

This Workplace Certification Made Already Safe Companies Even Safer

New research by Michael Toffel and colleagues confirms what workplace safety advocates have long claimed: Adopting OHSAS 18001 reduces worker injuries and improves a brand's image. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 17 Aug 2021

Can Autonomous Vehicles Drive with Common Sense?

Driverless vehicles could improve global health as much as the introduction of penicillin. But consumers won't trust the cars until they behave more like humans, argues Julian De Freitas. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 17 Sep 2019

- Cold Call Podcast

How a New Leader Broke Through a Culture of Accuse, Blame, and Criticize

Children’s Hospital & Clinics COO Julie Morath sets out to change the culture by instituting a policy of blameless reporting, which encourages employees to report anything that goes wrong or seems substandard, without fear of reprisal. Professor Amy Edmondson discusses getting an organization into the “High Performance Zone.” Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 11 Jun 2019

- Working Paper Summaries

Throwing the Baby Out with the Drinking Water: Unintended Consequences of Arsenic Mitigation Efforts in Bangladesh

In this study, households that were encouraged to switch water sources to avoid arsenic exposure experienced a significant rise in infant and child mortality, likely due to diarrheal disease from exposure to unsafe alternatives. Public health interventions should carefully consider access to alternatives when engaging in mass behavior change efforts.

- 31 Jan 2019

How Wegmans Became a Leader in Improving Food Safety

Ray Goldberg discusses how the CEO of the Wegmans grocery chain faced a food safety issue and then helped the industry become more proactive. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 09 May 2018

A Simple Way for Restaurant Inspectors to Improve Food Safety

Basic tweaks to the schedules of food safety inspectors could prevent millions of foodborne illnesses, according to new behavioral science research by Maria Ibáñez and Michael Toffel. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 12 Sep 2016

What Brands Can Do to Monitor Factory Conditions of Suppliers

For better or for worse, it’s fallen to multinational corporations to police the overseas factories of suppliers in their supply chains—and perhaps make them better. Michael W. Toffel examines how. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 17 Jun 2016

Companies Need to Start Marketing Security to Customers

The recent tragedies in Orlando underscore that businesses and their customers seem increasingly vulnerable to harm, so why don't companies do and say more about security? The ugly truth is safety doesn't sell, says John Quelch. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 05 Jan 2016

The Integrity of Private Third-party Compliance Monitoring

Michael Toffel and Jodi Short examine how conflict of interest and other risks lead to inaccurate monitoring of health, labor, and environmental standards.

- 21 May 2012

OSHA Inspections: Protecting Employees or Killing Jobs?

As the federal agency responsible for enforcing workplace safety, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration is often at the center of controversy. Associate Professor Michael W. Toffel and colleague David I. Levine report surprising findings about randomized government inspections. Key concepts include: In a natural field experiment, researchers found that companies subject to random OSHA inspections showed a 9.4 percent decrease in injury rates compared with uninspected firms. The researchers found no evidence of any cost to inspected companies complying with regulations. Rather, the decrease in injuries led to a 26 percent reduction in costs from medical expenses and lost wages—translating to an average of $350,000 per company. The findings strongly indicate that OSHA regulations actually save businesses money. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 24 Jan 2011

Terror at the Taj

Under terrorist attack, employees of the Taj Mahal Palace and Tower bravely stayed at their posts to help guests. A look at the hotel's customer-centered culture and value system. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

A case study exploring field-level risk assessments as a leading safety indicator

Lead research behavioral scientist and research behavioral scientist, respectively, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

B.P. Connor

J. vendetti.

Manager, mining operations, Solvay Soda Ash & Derivatives North America, Green River, WY, USA

CSP, Mine production superintendent, Solvay Chemicals Inc., Green River, WY, USA

Health and safety indicators help mine sites predict the likelihood of an event, advance initiatives to control risks, and track progress. Although useful to encourage individuals within the mining companies to work together to identify such indicators, executing risk assessments comes with challenges. Specifically, varying or inaccurate perceptions of risk, in addition to trust and buy-in of a risk management system, contribute to inconsistent levels of participation in risk programs. This paper focuses on one trona mine’s experience in the development and implementation of a field-level risk assessment program to help its organization understand and manage risk to an acceptable level. Through a transformational process of ongoing leadership development, support and communication, Solvay Green River fostered a culture grounded in risk assessment, safety interactions and hazard correction. The application of consistent risk assessment tools was critical to create a participatory workforce that not only talks about safety but actively identifies factors that contribute to hazards and potential incidents. In this paper, reflecting on the mine’s previous process of risk-assessment implementation provides examples of likely barriers that sites may encounter when trying to document and manage risks, as well as a variety of mini case examples that showcase how the organization worked through these barriers to facilitate the identification of leading indicators to ultimately reduce incidents.

Introduction

Work-related health and safety incidents often account for lost days on the job, contributing to organizational/financial and personal/social burdens ( Blumenstein et al., 2011 ; Pinto, Nunes and Ribeiro, 2011 ). Accompanying research demonstrates that risk and ambiguity around risk contribute to almost every decision that individuals make throughout the day ( Golub, 1997 ; Suijs, 1999 ). In response, understanding individual attitudes toward risk has been linked to predicting health and safety behavior ( Dohmen et al., 2011 ). Although an obvious need exists to identify more comprehensive methods to assess and mitigate potential hazards, some argue that risk management is not given adequate attention in occupational health and safety ( Haslam et al., 2016 ). Additionally, research suggests that a current lack of knowledge, skills and motivation are primary barriers to worker participation in mitigating workplace risks ( Dohmen et al., 2011 ; Golub, 1997 ; Haslam et al., 2016 ; Suijs, 1999 ). Therefore, enhancing knowledge and awareness around risk-based decisions, including individuals’ abilities to understand, measure and assign levels of risk to determine an appropriate response, is increasingly important in hazardous environments to predict and prevent incidents.

This paper focuses on one field-level risk assessment (FLRA) program, including a matrix that anyone can use to assess site-wide risks and common barriers to participating in such activities. We use a trona mine in Green River, WY, to illustrate that a variety of methods may be needed to successfully implement a proactive risk management program. By discussing the mine’s tailored FLRA program, this paper contributes to the literature by providing (1) common barriers that may prevent proactive risk assessment programs in the workplace and (2) case examples in the areas of teamwork, front-line leadership development, and tangible and intangible communication efforts to foster a higher level of trust and empowerment among the workforce.

Risk assessment practices to reveal leading indicators

Risk assessment is a process used to gather knowledge and information around a specific health threat or safety hazard ( Smith and Harrison, 2005 ). Based on the probability of a negative incident, risk assessment also includes determining whether or not the level of risk is acceptable ( Lindhe et al., 2010 ; International Electrotechnical Commission, 1995 ; Pinto, Nunes and Ribeiro, 2011 ). Risk assessments can occur quantitatively or qualitatively. Research values both types in high-risk occupations to ensure that all possible hazards and outcomes have been identified, considered and reduced, if needed ( Boyle, 2012 ; Haas and Yorio, 2016 ; Hallenbeck, 1993 ; International Council on Mining & Metals (ICMM), 2012 ; World Health Organization (WHO), 2008 ). Quantitative methods are commonly found where the site is trying to reduce a specific health or environmental exposure, such as respirable dust or another toxic substance ( Van Ryzin, 1980 ). These methods focus on a specific part of an operation or task within a system, rather than the system as a whole ( Lindhe et al., 2010 ). Conversely, a qualitative approach is useful for potential or recently identified risks to decide where more detailed assessments may be needed and prioritize actions ( Boyle, 2012 ; ICMM, 2012 ; WHO, 2008 ).

Although mine management can use risk assessments to inform procedural decisions and policy changes, they are more often used by workers to identify, assess and respond to worksite risks. A common risk assessment practice is to formulate a matrix that prompts workers to identify and consider the likelihood of a hazardous event and the severity of the outcome to yield a risk ranking ( Pinto, Nunes and Ribeiro, 2011 ). After completing such a matrix and referring to the discretized scales, any organizational member should be able to determine and anticipate the risk of a hazard, action or situation, from low to high ( Bartram, 2009 ; Hokstad et al., 2010 ; Rosén et al., 2006 ). The combination of these two “scores” is used to determine whether the risk is acceptable, and subsequently, to identify an appropriate response. For example, a list of hazards may be developed and evaluated for future interventions, depending upon the severity and probability of the hazards. Additionally, risk assessments often reveal a prioritization of identified risks that inform where risk-reduction actions are more critical ( Lindhe et al., 2010 ), which may result in changes to a policy or protocol ( Boyle, 2012 ).

If initiated and completed consistently, risk assessments allow root causes of accidents and patterns of risky behavior to emerge — in other words, leading indicators ( Markowski, Mannan and Bigoszewska, 2009 ). Leading indicators demonstrate pre-incident trends rather than direct measures of performance, unlike lagging indicators such as incident rates, and as a result, are useful for worker knowledge and motivation ( Juglaret et al., 2011 ). Recently, high-risk industries have allocated more resources to preventative activities — not only to prevent injuries but also to avoid the financial costs associated with incidents — which has produced encouraging results ( Maniati, 2014 ; Robson et al., 2007 ). However, research has pointed to workers’ general confusion about the interpretation of hazards and assignment of probabilities as a hindrance to appropriate risk identification and response ( Apeland, Aven and Nilsen, 2002 ; Reason, 2013 ). In response, better foresight into the barriers of risk management is needed to (1) engage workers in risk identification and assessment, and (2) develop pragmatic solutions to prevent incidents.

Methods and materials

In December 2015, Haas and Connor, two U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) researchers, traveled to Solvay Green River’s mine in southwest Wyoming. This trona mine produces close to 3 Mt/a of soda ash using a combination of longwall and solution mining and borer miners ( Fiscor, 2015 ). A health, safety and risk management framework had been introduced in phases during 2009 and 2010 to the mine’s workforce of more than 450 to help reduce risks to an acceptable level, and NIOSH wanted to understand all aspects of this FLRA program and how it became integrated into everyday work processes. We collected an extensive amount of qualitative data, analyzed the material and triangulated the results to inform a case study in health and safety system implementation ( Denzin and Lincoln, 2000 ; Pattson, 2002 ; Yin, 2014 ). The combination of expert interviews, existing documentary materials, and observation of onsite activities provided a holistic view of both post-hoc and current data points, allowing for various contexts to be compared and contrasted to determine consistency and saturation of the data ( Wrede, 2013 ).

Participants

We collected several qualitative data points, including all-day expert interviews and discussions with mine-site senior-level management such as the mine manager, health and safety manager, and mine foremen/supervisors, some of whom were hourly workers at the time of the risk assessment program implementation ( Flick, 2009 ). Additionally, we heard presentations from the mine managers and site supervisors, received archived risk assessment documents and were able to engage in observations on the surface and in the underground mine operation during the visit, where several mineworkers engaged in conversations about the FLRA, hazard interactions, and general safety culture on site.

Retrospective data analysis of risk assessment in action

Typically, qualitative analysis and triangulation of case study data use constant comparison techniques, sometimes within a grounded theory framework ( Corbin and Strauss, 2008 ; Glaser and Strauss, 1967 ). We employed the constant comparison method within a series of iterative coding steps. First, we typed the field notes and interview notes, and scanned the various risk assessment example documents received during the visit. Each piece of data was coded for keywords and themes through an initial, focused and then constant comparison approach ( Boyatzis, 1998 ; Fram, 2013 ).

Throughout the paper, quotes and examples from employees who participated in the visit are shared to better demonstrate their process to establish the FLRA program. To address the reliability and validity of our interpretation of the data, the two primary, expert information providers during the field visit, Vendetti and Heiser, became coauthors and served as member checkers of the data to ensure all information was described in a way that is accurate and appropriate for research translation to other mine sites ( Kitchener, 2002 ).

It is important to know that in 2009 Solvay experienced a sharp increase in incidents in its more-than-450-employee operation. Although no fatalities occurred, there were three major amputations and injury frequencies that were increasing steadily. The root causes of these incidents — torn ligaments/tendons/muscles requiring surgical repair or restricted duty; lacerations requiring sutures; and fractures ( Mine Safety and Health Administration, 2017 ) — showed that inconsistent perceptions of risk and mitigation efforts were occurring on site among all types of work positions, from bolters to maintenance workers. These incidents caused frustration and disappointment among the workforce.

Intervention implementation, pre- and post-FLRA program

Faced with inconsistencies in worker knowledge of risks and varying levels of risk tolerance, management could have taken a punitive, “set an example” response, based on an accountability framework. Instead, they began a process in 2009 to bring new tools, methods and mindset to safety performance at the site. Specifically, based on previous research and experience, such as from 1998, they saw the advantages of creating a common, site-wide set of tools and metrics to guide workers in a consistent approach to risk assessment in the field. This involvement trickled down to hourly workers in the form of a typical risk assessment matrix ( Table 1 ) described earlier to identify, assess and evaluate risks. Management indicated that if everyone had tools, then “It doesn’t matter what you knew or what you didn’t, you had tools to assess and manage a situation.” They hypothesized that matrices populated by workers would reveal leading indicators to proactively identify and prevent incidents that had been occurring on site. Workers were expected to utilize this matrix daily to help identify and evaluate risks.

Risk assessment matrix used by Solvay ( Heiser and Vendetti, 2015 ).

To complete the matrix, workers rate consequences of a risk using the scales/key depicted in Table 2 . As shown in the color-coded matrix, multiplying the scores for these two areas yields a risk ranking of low, moderate, high or critical, thereby providing guidance on what energies or hazards to mitigate immediately. Although the matrix approach, specifically, may not be new to the industry, the implementation and evaluation of such efforts offer value in the form of heightened engagement, leadership and eventually behavior change.

Evaluation matrix key ( Heiser and Vendetti, 2015 ).

Observing incidents post-implementation of the FLRA intervention during 2009 and front-line leadership efforts during 2010, much can be learned to understand where and how impact occurred on site. Figure 1 shows Green River’s 2009 spike in non-fatal days lost (NFDL) incidents with a consistent drop thereafter, providing cursory support of the program.

Solvay non-fatal days lost operator injuries, 2006–2016 ( MSHA, 2017 ).

Seeing a drop in incidents provides initial support for the FLRA program that Solvay introduced. Knowing that many covariates may account for a drop in incidents, however, additional data were garnered from MSHA’s website to account for hours worked. Still, the incident rate declined consistently, as shown in Fig. 2 .

Non-fatal days lost operator injury incidence rate (injuries by hours worked), 2006–2016 ( MSHA, 2017 ).

From a quantitative tracking effort of these lagging indicators, it can be gleaned that the implemented program was successful. However, it is important to understand what, how and why incidents decreased over time to maintain consistency in implementation and evaluation efforts. In response, this paper focuses on the qualitative data that NIOSH collected in hopes of sharing how common barriers to risk assessment can be addressed to identify leading indicators on site.

During the iterative analysis of the data, researchers sorted the initial and ongoing barriers to continuous risk assessment. The results provide insight into promising ways to measure and document as well as support and manage a risk-based program over several years. After common barriers to risk assessment implementation are discussed, mini case examples to illustrate how the organization improved and used their FLRA process to identify leading indicators follow. Ultimately, these barriers and organizational responses show that an FLRA program can help (1) measure direct/indirect precursors to harm and provide opportunities for preventative action, (2) allow the discovery of proactive leadership risk reduction strategies, and (3) provide warning before an undesired event occurs and develop a database of response strategies ( Blumenstein et al., 2011 ; ICMM, 2012 ).

Barrier to risk assessment intervention: Varying levels of risk tolerance and documentation

An initial challenge, not uncommon in occupational health and safety, was the varying levels of risk tolerance possessed by the workforce. Research shows that individuals have varying levels of knowledge, awareness and tolerance in their abilities to recognize and perceive risks as unacceptable ( Brun, 1992 ; Reason, 2013 ; Ruan, Liu and Carchon, 2003 ). Managers and workers reflected that assessments of a risk were quite broad, having an impact on the organization’s ability to consistently identify and categorize hazards. One employee who was an hourly worker at the time of the FLRA implementation said, “It took time to establish a sensitivity to potential hazards.” This is not particularly surprising; as individuals gain experience, they can become complacent with health and safety risks and, eventually, have a lower sense of perceived susceptibility and severity of a negative outcome ( Zohar and Erev, 2006 ). As a result, abilities to consistently notice and believe that a hazard poses threat to their personal health and safety decreases. The health and safety manager said, “It took a long time to get through to people that this isn’t the same as what they do every day. To really assess a risk you have to mentally stop what you’re doing and consider something.”

Eventually, management developed an understanding that risk tolerance differed individually and generationally onsite, acknowledging that sources of risk are always changing in some regard and tend to be more complicated for some employees to see than others. In response, discussions about the importance of encouraging conscious efforts of risk management became ongoing to support a new level of awareness on site. Additionally, the value of documenting risk assessment efforts on an individual and group level became more apparent. One area emphasized was encouraging team communication around risk assessment if it was warranted. An example of this process and outcome is detailed below to help elucidate how Solvay overcame disparate perceptions of risk through teamwork.

Case example: FLRA discussion and documentation in action

An example of the FLRA in action as a leading indicator was provided by the maintenance supervisor during the visit. This example included an installation of a horizontal support beam. Workers collectively completed an FLRA to determine if they could simply remove the gantry system without compromising the integrity of the headframe. As part of their FLRA process, workers were expected to identify energies/hazards that could exist during this job task. Hazards that they recorded for this process for consideration within the matrix as possible indicators included:

- Working from heights/falling.

- Striking against/being struck by objects.

- Pinch points.

- Traction and balance.

- Hand placement.

- Caught in/on/between objects.

An initial risk rank was provided for each of the identified hazards, based on the matrix ( Tables 1 and and2). 2 ). Based on the initial risk rank, workers decided which controls to implement to minimize the risk to an acceptable level. Examples of controls implemented included:

- Review the critical lift plan.

- Conduct a pre-job safety and risk assessment meeting.

- Inspect all personal protective equipment (PPE) fitting and harnesses.

- Understand structural removal sequence.

- Communicate between crane operator and riggers.

- Assure 100 percent of tie-off protocol is followed.

- Watch out for coworkers.

- Participate in housekeeping activities.

Upon determining and implementing controls, a final risk rank was rendered to make a decision for the job task: whether or not the headframe could be removed in one section. Ultimately, workers decided it could safely be done. However, management emphasized the importance of staying true to their FLRA. They said that 50 percent of their hoisting capabilities are based on wind and that if the wind is too high, they shut down the task, which happened one day during this process. So, although an FLRA was completed and provided a documented measurement and direction about what decisions to carry out, the idea of staying true to a minute-by-minute risk assessment was important and adhered to for this task.

In this sense, the FLRAs served as a communication platform to share a common language and ultimately, common proactive behavior. In general, vagueness of data on health and safety risks can prevent hazard recognition, impair decision-making, and disrupt risk-based decisions among workers ( Ruan, Liu and Carchon, 2003 ). This example showed that the more workers understood what constitutes an acceptable level of risk, the greater sense of shared responsibility they had to prevent hazards and make protective decisions on the job ( Reason, 1998 ) such as shutting down a procedure due to potential problems. Now, workers have the ability to implement their own check-and-balance system to determine if a response is needed and their decision is supported. Treating the FLRA as a check-and-balance system allowed workers to improve their own risk assessment knowledge, skills and motivation, a common barrier to hazard identification ( Haslam et al., 2016 ). In theory, as FLRAs are increasingly used to predetermine possible incidents and response strategies are developed and referenced, the occurrence of lagging indicators should decrease, as has been the case at Solvay in recent years.

Barrier to risk assessment intervention: Resisting formal risk assessment methods

Worksites often face challenges of determining the best ways to measure and develop suitable tools to facilitate consistent risk measurement ( Boyle, 2012 ; Haas and Yorio, 2016 ; Haas, Willmer and Cecala, 2016 ). For example, research shows that assessing site risks using a series of checklists or general observations during site walkthroughs is more common ( Navon and Kolten, 2006 ). Although practical, checklists and observations require little cognitive investment and have more often been insufficient in revealing potential safety problems ( Jou et al., 2009 ). Due to familiarity with “the way things were,” implementing the system of risk assessments at Solvay came with challenges. Workers experienced initial resistance to moving toward something more formal.

For example, at the outset, hourly workers said they felt, “I do this in my head all the time. I just don’t write it down.” Particularly, individuals who were hourly workers at the time of the FLRA program implementation felt that they already did some form of risk identification and that they did not need to go into more detail to assess the risk. Just as some workers did not see a difference with what they did implicitly, and so discounted the value of conducting an FLRA, others did not think they needed to take action based on their matrix risk ranking. As one worker reflected on the previous mindset, he said, “It would be okay to be in the red, so long as you knew you were in the red.” Because of the varying levels of initial acceptance, there were inconsistencies in the quality of the completed risk assessment matrices. Management noted, “Initially, people were doing them, but not to the quality they could have been.” In response, Solvay management focused on strengthening their frontline leadership skills to help facilitate hourly buy-in, as described in the following case example.

Case example: Starting with frontline leadership to facilitate buy-in, “The Club”

To facilitate wider commitment and buy-in, senior-level management took additional steps with their frontline supervisors. To train frontline leaders on how to understand rather than punish worker actions, Solvay management started a working group in 2010 called “The Club.” This group consisted of supervisory personnel within various levels of the organization. The purpose of The Club was to develop leaders and a different sort of accountability with respect to safety. One of its first actions was to, as a group, agree on qualities of a safety leader. From there, they eventually executed a quality leadership program that embraced the use of the risk assessment tools and their outcomes ( Fiscor, 2015 ; Heiser and Vendetti, 2015 ).

After receiving this leadership training and engaging in discussions about FLRA, the execution of model leadership from The Club started. Specifically, the frontline foremen that the researchers talked with indicated that they were better able to communicate about and manage safety across the site. Prior to The Club and adapting to the FLRA, one of these supervisors reflected, “No one wanted to make a safety decision.” Senior management acknowledged with their frontline leadership that the FLRA identifies steps that anyone might miss because they are interlocked components of a system. Because of the complex risks present on site, they discussed the importance of sitting down and reviewing with hourly workers if something happened or went wrong. They shared the importance of supportive language: “We say ‘let’s not do this again,’ but they don’t get in trouble.”

To further illustrate the leadership style and communicative focus, one manager shared a conversation conducted with a worker after an incident. Rather than reprimanding the worker’s error in judgement, the manager asked: “What was going through your mind before, during this task? I just want to understand you, your choices, your thought process, so we can prevent someone else from doing the same thing, making those same choices.” After the worker acknowledged he did not have the right tools but tried to improvise, the manager asked him what other risky choices he had made that turned out okay. This process engaged the worker, and he “really opened up” about his perceptions and behaviors on site. This incident is an example of site leaders establishing accountability for action but ensuring that adequate resources and site support were available to facilitate safer practice in the future ( Yorio and Willmer, 2015 ; Zohar and Luria, 2005 ). In other words, management used these conversations not only to educate the workers about hazards involved in complex systems, but also to enact their positive safety culture.

Importantly, this communication and documentation among The Club allowed insight into how employees think, serving as a leading indicator for health and safety management. The stack of FLRAs that were pulled out — completed between 2009 and 2015 — were filled out with greater detail as the years progressed. It was apparent that the hourly workforce continually adapted, resulting in an improved sense of organizational motivation, culture and trust. Management indicated to NIOSH that workers now have an increased sense of empowerment to identify and mitigate risks. Contrary to how workers used to document their risk assessments, a management member said: “You pull one out today, and even if it isn’t perfect, the fundamentals are all there, even if it isn’t exactly how we would do it. And more likely than not, you’d pull out one and find it to be terrific.”

Barrier to risk assessment intervention: Communicate and show tangible support for risk assessment methods

A lack of management commitment, poor communication and poor worker involvement have all been identified as features of a safety climate that inhibit workers’ willingness to proactively identify risks ( Rundmo, 2000 ; Zohar and Luria, 2005 ). Therefore, promoting these organizational factors was needed to encourage workers to identify hazards and prevent incidents ( Pinto et al., 2011 ). When first rolling out their FLRA process, Solvay management knew that if they were going to transform safety practices at the mine, there had to be open communication between hourly and salary workers about site conditions and practices ( Fiscor, 2015 ; Heiser and Vendetti, 2015 ; Neal and Griffin, 2006 ; Reason, 1998 ; Rundmo, 2000 ; Wold and Laumann, 2015 ; Zohar and Luria, 2005 ). They discussed preparing themselves to be “exposed” to such information and commit as a group to react in a way that would maintain buy-in, use and behavior.

Creating a process of open sharing meant that, especially at the outset, management was likely to hear things that they didn’t necessarily want to hear. Despite perhaps not wanting to hear feedback against a policy in place or attitude of risk acceptance, all levels of management wanted to communicate their understanding for changing risks and hazards, and the need to sometimes adapt policies in place based on changing energies in the environment, as revealed by the FLRAs that the workers were taking time to complete. The following case example showcases the value of ongoing communication to maintain a risk assessment program and buy-in from workers.

Case example: Illustrating flexibility with site procedures

During the visit, managers and workers both discussed the conscious efforts made during group meetings and one-on-one interactions to improve their organizational leadership and communication, noting the difficulty of incorporating the FLRA as a complement to existing rules and regulations on site: “We needed to continually stress the importance of utilizing the risk assessment tool, and if something were to occur, to evaluate the level of controls implemented during a reassessment of the task.” To encourage worker accountability, the managers wanted to show their commitment to the FLRA process and that they could be flexible in changing a rule or policy if the risk assessment showed a need. As an example, they showed NIOSH a “general isolation” procedure about lock-out/tag-out that was distributed at their preshift safety meeting that morning. They handed out a piece of paper saying that, “While a visual disconnect secured with individual locks is always the preferred method of isolation, there are specific isolation procedures for tasks unique to underground operations.” The handout went on to state: “In rare circumstances, when a visual disconnect with lock is not used and circumstances other than those specifically identified are encountered, a formal documented risk assessment will be performed. All potential energies will be identified and understood, every practical barrier at the appropriate level will be identified and implemented, and the foreman in charge of the task will approve with his/her signature prior to performing the work. All personnel involved in the job or task must review and understand the energies and barriers implemented prior to any work being performed…”

This example shows the site’s commitment to risk assessment while also showing that, if leading indicators are identified, a policy can be changed to avoid a potential incident. Noting that they would change a procedure if workers identified something, the document illustrated management’s confidence and value in the FLRA process. Workers indicated that these behaviors are a support mechanism for them and their hazard identification efforts. Along the same lines, the managers we talked with noted the importance of not just training to procedure but also to emphasize: “High-level policies complement but don’t drive safety.” This example showcases their leadership and communicative commitment.

The lock-out/tag-out example is just one safety share that occurred at a preshift meeting. These shares “might be no more than five minutes, they might go a half-hour, but they’re allowed to take as long as they need,” one manager said. This continued commitment to foster the use of leading indicators to support a health and safety management program has shown that the metrics used to assess risks are only as good as the response to those metrics to support and encourage health and safety as well as afforded workers an opportunity to engage in improving the policies and rules on site. This continued consistency in communication helped to create a sense of ownership among workers, which led them to recognize the need for a minute-to-minute thought process that helped them foresee consequences, probabilities, and deliberate different response options. As one manager said, “You can have a defined plan but an actual risk assessment shows the dynamics of a situation and allows different plans to emerge.”

Limitations and conclusions

The purpose of this paper was to illustrate an example in which everyone could participate to identify leading safety indicators. In everyone’s judgment, it took about four to five years until Solvay actually saw the change in action, meaning that the process was sustained by workers and they were using the risk assessment terminology in their everyday discussions. In addition to providing how leading indicators can be developed or look “in action,” this paper advanced the discussion to provide insight into common barriers to risk assessment, and potential responses to these barriers. As Figs. 1 and and2 2 show, incidents had been down at Solvay since the implementation of the FLRA program and enhanced leadership training of frontline supervisors, showing the impact of the FLRAs as a strong leading indicator for health and safety. Additionally, hourly workers discussed how much better the culture is on site now than it was several years ago, noting their appreciation for having a common language on site to communicate about risks. It is rare that both sides — hourly and salary — see benefits in a written tool from an operational and behavioral standpoint. The cooperation on site speaks to the positive attributes discussed within this case study and mini examples provided that cannot be shown in a graph.

Although the results of this study are only part of a small case study and cannot be generalized across the industry, data support the argument that poor leadership and an overall lack of trust on site can inhibit workers’ willingness to participate in risk measurement, documentation and decision-making. Obviously, the researchers could not talk with every worker and manager present on site, so not all opinions are reflected in this paper. However, the consistency in messages from both levels of the organization showed saturation of insights that reflect the impact of the FLRAs. It is acknowledged that some of this information may already be known and utilized by mine site leadership. However, because the focus of the study was not only on the development and use of specific risk measurement tools, but the organizational practices that are needed to foster such proactive behavior, the results provide several potential areas of improvement for the industry in terms of formal risk assessment over a period of time.

In lieu of these limitations, mine operators should consider this information when interpreting the results in terms of (1) how to establish formal risk assessment on site, especially when trying to identify and mitigate hazards, (2) what the current mindset of frontline leadership may be and how they could support (or hinder) such an risk assessment program and (3) methods to consistently support a participatory risk assessment program. Gaining an in-depth view of Solvay’s own health and safety journey provides expectations and a possible roadmap for encouraging worker participation in risk management at other mine sites to proactively prevent health and safety incidents.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Solvay Green River operation for its participation and cooperation in this case study and for openly sharing their experiences.

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of NIOSH. Reference to specific brand names does not imply endorsement by NIOSH.

Contributor Information

E.J. Haas, Lead research behavioral scientist and research behavioral scientist, respectively, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

B.P. Connor, Lead research behavioral scientist and research behavioral scientist, respectively, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

J. Vendetti, Manager, mining operations, Solvay Soda Ash & Derivatives North America, Green River, WY, USA.

R. Heiser, CSP, Mine production superintendent, Solvay Chemicals Inc., Green River, WY, USA.

- Apeland S, Aven T, Nilsen T. Quantifying uncertainty under a predictive epistemic approach to risk analysis. Reliability Engineering and System Safety. 2002; 75 :93–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0951-8320(01)00122-3 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Bartram J. Water safety plan manual: step-by-step risk management for drinking-water suppliers. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blumenstein D, Ferriter R, Powers J, Reiher M. Accidents – The Total Cost: A Guide for Estimating The Total Cost of Accidents. Western Mining Safety and Health Training and Translation Center, Colorado School of Mines, Mine Safety and Health Program technical staff. 2011 http://inside.mines.edu/UserFiles/File/MSHP/GuideforEstimatingtheTotalCostofAccidentspercent20FINAL(8-10-11).pdf .

- Boyatzis RE. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Boyle T. Health And Safety: Risk Management. Routledge; New York, NY: 2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brun W. Cognitive components in risk perception: Natural versus manmade risks. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 1992; 5 :117–132. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.3960050204 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research. 3. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. pp. 1–28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dohmen T, Falk A, Huffman D, Sunde U, Schupp J, Wagner GG. Individual risk attitudes: measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association. 2011; 9 (3):522–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01015.x . [ Google Scholar ]

- Fiscor S. Solvay implements field level risk assessment program. Engineering and Mining Journal. 2015; 216 (9):38–42. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flick U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fram SM. The constant comparative method outside of grounded theory. The Qualitative Report. 2013; 18 (1):1–25. [ Google Scholar ]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Adeline; Chicago, IL: 1967. [ Google Scholar ]

- Golub A. Decision Analysis: An Integrated Approach. Wiley; New York, NY: 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- Haas EJ, Yorio P. Exploring the state of health and safety management system performance measurement in mining organizations. Safety Science. 2016; 83 :48–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2015.11.009 . [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haas EJ, Willmer DR, Cecala AB. Formative research to reduce mine worker respirable silica dust exposure: a feasibility study to integrate technology into behavioral interventions. Pilot and Feasibility Studies. 2016; 2 (6) https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-016-0047-1 . [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hallenbeck WH. Quantitative Risk Assessment for Environmental and Occupational Health. 2. Lewis Publishers; Boca Raton, NY: 1993. [ Google Scholar ]

- Haslam C, O’Hara J, Kazi A, Twumasi R, Haslam R. Proactive occupational safety and health management: Promoting good health and good business. Safety Science. 2016; 81 :99–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2015.06.010 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Heiser R, Vendetti JA. Field Level Risk Assessment - A Safety Culture. Longwall USA Exhibition and Convention; June 16, 2016; Pittsburgh, PA. 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hokstad P, Røstum J, Sklet S, Rosén L, Lindhe A, Pettersson T, Sturm S, Beuken R, Kirchner D, Niewersch C. Deliverable No. D 4.2.4. Techneau; 2010. Methods for Analysing Risks of Drinking Water Systems from Source to Tap. [ Google Scholar ]

- International Council on Mining & Metals. Overview of Leading Indicators For Occupational Health And Safety In Mining. 2012 Nov; https://www.icmm.com/en-gb/publications/health-and-safety/overview-of-leading-indicators-for-occupational-health-and-safety-in-mining .

- International Electrotechnical Commission. IEC 300-3-9. Geneva: 1995. Dependability Management – Risk Analysis of Technological Systems. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jou Y, Lin C, Yenn T, Yang C, Yang L, Tsai R. The implementation of a human factors engineering checklist for human–system interfaces upgrade in nuclear power plants. Safety Science. 2009; 47 :1016–1025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2008.11.004 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Juglaret F, Rallo JM, Textoris R, Guarnieri F, Garbolino E. New balanced scorecard leading indicators to monitor performance variability in OHS management systems. In: Hollnagel E, Rigaud E, Besnard D, editors. Proceedings of the fourth Resilience Engineering Symposium; June 8–10, 2011; Sophia-Antipolis, France, Presses des Mines, Paris. 2011. pp. 121–127. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pressesmines.1015 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Kitchener M. Mobilizing the logic of managerialism in professional fields: The case of academic health centre mergers. Organization Studies. 2002; 23 (3):391–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840602233004 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Lindhe A, Sturm S, Røstum J, Kožíšek F, Gari DW, Beuken R, Swartz C. Deliverable No. D4.1.5g. Techneau; 2010. Risk Assessment Case Studies: Summary Report. https://www.techneau.org/fileadmin/files/Publications/Publications/Deliverables/D4.1.5g.pdf . [ Google Scholar ]

- Markowski A, Mannan S, Bigoszewska A. Fuzzy logic for process safety analysis. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries. 2009; 22 :695–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlp.2008.11.011 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Maniati M. The Business Benefits of Health and Safety: A Literature Review. British Safety Council; 2014. https://www.britsafe.org/media/1569/the-business-benefits-health-and-safety-literature-review.pdf . [ Google Scholar ]

- Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) Data & Reports. U.S. Department of Labor; 2017. https://www.msha.gov/data-reports . [ Google Scholar ]

- Navon R, Kolton O. Model for automated monitoring of fall hazards in building construction. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management. 2006; 132 (7):733–740. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)0733-9364(2006)132:7(733) [ Google Scholar ]

- Neal A, Griffin MA. A study of the lagged relationships among safety climate, safety motivation, safety behavior, and accidents at the individual and group levels. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006; 91 (4):946–953. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.946 . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pattson MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pinto A, Nunes IL, Ribeiro RA. Occupational risk assessment in construction industry – Overview and reflection. Safety Science. 2011; 49 :616–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2011.01.003 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Reason J. Achieving a safe culture: Theory and practice. Work & Stress. 1998; 12 (3):293–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678379808256868 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Reason J. A Life in Error: From Little Slips to Big Disasters. Ashgate Publishing; Burlington, VT: 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Robson LS, Clarke JA, Cullen K, Bielecky A, Severin C, Bigelow PL, Mahood Q. The effectiveness of occupational health and safety management system interventions: a systematic review. Safety Science. 2007; 45 (3):329–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2006.07.003 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Rosén L, Hokstad P, Lindhe A, Sklet S, Røstum J. Generic Framework and Methods for Integrated. Water Science and Technology. 2006; 43 :31–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ruan D, Liu J, Carchon R. Linguistic assessment approach for managing nuclear safeguards indicators information. Logistics Information Management. 2003; 16 (6):401–419. https://doi.org/10.1108/09576050310503385 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Rundmo T. Safety climate, attitudes and risk perception in Norsk Hydro. Safety Science. 2000; 34 (1):47–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0925-7535(00)00006-0 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith SP, Harrison MD. Measuring reuse in hazard analysis. Reliability Engineering & System Safety. 2005; 89 (1):93–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2004.08.010 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Suijs J. Cooperative Decision-Making Under Risk. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Springer Science+Business Media New York; NY: 1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Ryzin J. Quantitative risk assessment. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 1980; 22 (5):321–326. https://doi.org/10.1097/00043764-198005000-00004 . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wold T, Laumann K. Safety management systems as communication in an oil and gas producing company. Safety Science. 2015; 72 :23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2014.08.004 . [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization. Recommendations. 3. Vol. 1. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2008. Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality [Electronic Resource]: Incorporating First and Second Addenda. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wrede S. How country matters: Studying health policy in a comparative perspective. In: Bourgeault I, Dingwall R, de Vries R, editors. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Methods in Health Research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 5. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yorio PaL, Willmer DR. Explorations in Pursuit of Risk-Based Health and Safety Management Systems. SME Annual Conference & Expo; Feb. 15–18, 2015; Denver, CO: Society for Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zohar D, Erev I. On the difficulty of promoting workers’ safety behaviour: Overcoming the underweighting of routine risks. International Journal of Risk Assessment and Management. 2006; 7 (2):122–136. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijram.2007.011726 . [ Google Scholar ]

- Zohar D, Luria G. A multilevel model of safety climate: cross-level relationships between organization and group-level climates. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2005; 90 (4):616–628. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.4.616 . [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

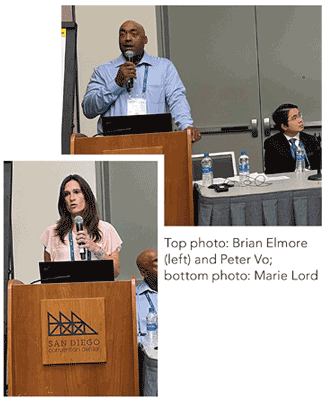

OSHA's most interesting cases

What happened – and lessons learned.

Every OSHA investigation offers an opportunity for using what comes to light to help prevent similar incidents.

At the 2022 NSC Safety Congress & Expo in September, OSHA staffers highlighted three investigations – and the lessons learned – during the agency’s “Most Interesting Cases” Technical Session.

- Brian Elmore , an OSHA inspector based in Omaha, NE

- Marie Lord , assistant area director of the OSHA office in Marlton, NJ

- Peter Vo , safety engineer in OSHA’s Houston South area office

Here are the cases they presented.

- Shelving collapse in a cold storage warehouse

- Lockout/tagout-related amputation

- Crane collapse

Post a comment to this article

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)

Report Abusive Comment

Assessing workplace hazard and safety: Case study on falling from height at building construction site

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Reprints and Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

N. A. Shuaib , N. R. Nik Yusoff , W. A. R. Assyahid , P. T. Ventakasubbarow , M. R. Walker , Y. Ravindaran , T. Arumugam , V. Nagasvaran; Assessing workplace hazard and safety: Case study on falling from height at building construction site. AIP Conf. Proc. 3 May 2021; 2339 (1): 020219. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0044256

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Construction of building exposes the workers to the hazards of working at height. Although safety measures have been enforced and taken by the workers, the case about accidents from such workplace are still being reported. In the last 20 years, there have been significant reductions in the number and rate of injury. Nevertheless, construction continues to be one of the high-risk sectors in the world. This research attempted to assess the real case of falling from heights that had happened in Malaysia. The purpose of this case study is to make an evaluation of workplace hazard and safety through a HIRARC analysis. Case 1 was about a worker who fall from formworks structure and pronounced dead at the scene. Case 2 involved another worker who fall through roof opening dead on the same day as sent to hospital. The data was evaluated in form of Hazard Identification, Risk Assessment and Risk Control, Cause and Effect analysis, and Pareto analysis. Failure to manage and apply consistent safe work practise shall result to accidents which could give impact the country's economic development. Experience does not seem to diminish accident occurrence; hazards are often misjudged by workers.

Sign in via your Institution

Citing articles via, publish with us - request a quote.

Sign up for alerts

- Online ISSN 1551-7616

- Print ISSN 0094-243X

- For Researchers

- For Librarians

- For Advertisers

- Our Publishing Partners

- Physics Today

- Conference Proceedings

- Special Topics

pubs.aip.org

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Connect with AIP Publishing

This feature is available to subscribers only.

Sign In or Create an Account

Top 40 Most Popular Case Studies of 2021

Two cases about Hertz claimed top spots in 2021's Top 40 Most Popular Case Studies

Two cases on the uses of debt and equity at Hertz claimed top spots in the CRDT’s (Case Research and Development Team) 2021 top 40 review of cases.

Hertz (A) took the top spot. The case details the financial structure of the rental car company through the end of 2019. Hertz (B), which ranked third in CRDT’s list, describes the company’s struggles during the early part of the COVID pandemic and its eventual need to enter Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

The success of the Hertz cases was unprecedented for the top 40 list. Usually, cases take a number of years to gain popularity, but the Hertz cases claimed top spots in their first year of release. Hertz (A) also became the first ‘cooked’ case to top the annual review, as all of the other winners had been web-based ‘raw’ cases.

Besides introducing students to the complicated financing required to maintain an enormous fleet of cars, the Hertz cases also expanded the diversity of case protagonists. Kathyrn Marinello was the CEO of Hertz during this period and the CFO, Jamere Jackson is black.

Sandwiched between the two Hertz cases, Coffee 2016, a perennial best seller, finished second. “Glory, Glory, Man United!” a case about an English football team’s IPO made a surprise move to number four. Cases on search fund boards, the future of malls, Norway’s Sovereign Wealth fund, Prodigy Finance, the Mayo Clinic, and Cadbury rounded out the top ten.

Other year-end data for 2021 showed:

- Online “raw” case usage remained steady as compared to 2020 with over 35K users from 170 countries and all 50 U.S. states interacting with 196 cases.

- Fifty four percent of raw case users came from outside the U.S..

- The Yale School of Management (SOM) case study directory pages received over 160K page views from 177 countries with approximately a third originating in India followed by the U.S. and the Philippines.

- Twenty-six of the cases in the list are raw cases.

- A third of the cases feature a woman protagonist.

- Orders for Yale SOM case studies increased by almost 50% compared to 2020.

- The top 40 cases were supervised by 19 different Yale SOM faculty members, several supervising multiple cases.

CRDT compiled the Top 40 list by combining data from its case store, Google Analytics, and other measures of interest and adoption.

All of this year’s Top 40 cases are available for purchase from the Yale Management Media store .

And the Top 40 cases studies of 2021 are:

1. Hertz Global Holdings (A): Uses of Debt and Equity

2. Coffee 2016

3. Hertz Global Holdings (B): Uses of Debt and Equity 2020

4. Glory, Glory Man United!

5. Search Fund Company Boards: How CEOs Can Build Boards to Help Them Thrive

6. The Future of Malls: Was Decline Inevitable?

7. Strategy for Norway's Pension Fund Global

8. Prodigy Finance

9. Design at Mayo

10. Cadbury

11. City Hospital Emergency Room

13. Volkswagen

14. Marina Bay Sands

15. Shake Shack IPO

16. Mastercard

17. Netflix

18. Ant Financial

19. AXA: Creating the New CR Metrics

20. IBM Corporate Service Corps

21. Business Leadership in South Africa's 1994 Reforms

22. Alternative Meat Industry

23. Children's Premier

24. Khalil Tawil and Umi (A)

25. Palm Oil 2016

26. Teach For All: Designing a Global Network

27. What's Next? Search Fund Entrepreneurs Reflect on Life After Exit

28. Searching for a Search Fund Structure: A Student Takes a Tour of Various Options

30. Project Sammaan

31. Commonfund ESG

32. Polaroid

33. Connecticut Green Bank 2018: After the Raid

34. FieldFresh Foods

35. The Alibaba Group

36. 360 State Street: Real Options

37. Herman Miller

38. AgBiome

39. Nathan Cummings Foundation

40. Toyota 2010

ASHRM President O’Sullivan’s March Message

We thrive together at ashrm.

Emerging Roles of Risk Managers in Senior Living and Skilled Nursing

Handling Disagreements Between Telehealth Critical Care and Bedside Providers

Strategies for Communication and Apology are Critical for Front-line Staff

Risk Professionals Ideal to Lead Health Care ESG Journey

- Uncategorized

Case Studies in Patient Safety

- Google Plus

Storytelling has been key to learning since the beginning of humankind. Case studies are a form of storytelling that often includes learning objectives, reflection and analysis. This book by Julie K. Johnson, Helen W. Haskell and Paul R. Barach uses storytelling to explore medical cases from the viewpoints of surviving family members. The amount of effort to collect such stories must have been astounding, but the reader benefits in incalculable ways.

The book’s stories illuminate how the industry might move from a clinician-centered system of care to a patient and family-centered system of care. The authors refer to Paul Batalden’s quote, “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.” For example, the results of the current medical educations system are knowledgeable diagnosticians who are focused on the individual physician-patient dyad. The authors examined 153 competencies across disciplines internationally that seem to correlate with good outcomes. The book’s stories are organized by these competencies:

- Medical knowledge, patient care

- Professionalism

- Interpersonal/communication skills

- Practice-based learning and improvement

- System-based practice

- Interprofessional collaboration

- Personal and professional development

One sees where professionalism and interpersonal/communication skills are greater important deficits for the families than knowledge or patient care aspects. This sets up the challenge for the reader, as the authors promote, to think differently about how to emotionally and intellectually engage patients and providers in healthcare transformation.

Discussed are 24 cases resulting from in- and out-patient settings in locations throughout the English-speaking world. One poignant case concerned a routine endoscopic procedure, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Post discharge, the patient began regurgitating, perspiring and was in pain. A telephone call to the office nurse resulted in a Tylenol suggestion. Then the physician called and suggested soup. A family member demanded a direct admission. The patient arrived at the emergency room with no forwarding message from the physician so she waited 12 hours for pain meds, but a full workup was achieved. The physician was not returning any emergency room calls as it was after 5 p.m. and the covering colleague said “not my patient.” As the patient deteriorated, a catheter was inserted. Then she was moved to the ICU and then to CCU. Diagnosis: sepsis. No record was ever found for the catheter order nor the ICU or CCU admissions. By now hospital specialists were attending to the patient with no sign of the original surgeon. The first code blue was noted.

With pneumonia and sepsis prevailing, staff placed a ventilator. Physicians mentioned pancreatitis after ERCP. They said it was not uncommon and the patient should recover. Eleven days later the patient had a cardiac arrest and coded. There were conflicting stories whether this occurred during a bath or during some suctioning. The code was unsuccessful. The family was not called by nursing per the protocol.

The CEO called the family back about a month after the death. New management had taken over the hospital. The CEO was trying to set a meeting with the family and physician, but the physician refused. After a year from the death, the physician accepted a meeting. Evidently, he felt comfortable because the family had not requested an autopsy so there was no way to prove whether the surgeon should have done the procedure in the first place or if he had done it wrong. The family regrets the omission of the autopsy because they saw there was no redress possible without it. After a complaint, the state medical board saw no wrong doing on the part of the surgeon. The state’s health services department did cite the emergency room for the lack of care of the patient.

The family felt abandoned by the surgeon, wrote a book about the event and discovered that adverse events were not nearly as common as they were led to believe. The book reviews further insight and notes ERCP is now widely overused.

In conclusion, this book presents poignant case studies that prompt one to think about various sides of stories and how systems, cultures and technical skills intertwine to affect life and death. One sees how the lack of communication can trump all of the aforementioned items to create a disaster. However, the reader is not left depressed, but instead inspired by the people sharing their stories and by the subsequent critical thinking that can occur after reading them.

Johnson, J., Haskell, H., & Barach, P. (2016) Case Studies in Patient Safety. Subury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning

You may also like

Building a High-Reliability Organization: A Toolkit for Success

ASHRM Whitepaper – Telemedicine: Risk Management Considerations

Stronger: Develop the Resilience You Need to Succeed

Sign up for ashrm forum updates.

Provide your information below to subscribe to ASHRM email communications

ASHRM Forum

- Submit an Article

Recent Articles

- ASHRM President O’Sullivan’s March Message March 20, 2024

- We thrive together at ASHRM January 10, 2024

- Emerging Roles of Risk Managers in Senior Living and Skilled Nursing October 16, 2023

- Handling Disagreements Between Telehealth Critical Care and Bedside Providers September 12, 2023

- Strategies for Communication and Apology are Critical for Front-line Staff September 7, 2023

- January 2024

- October 2023

- September 2023

- November 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- November 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018