Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

Published on October 18, 2021 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from people.

The goals of human research often include understanding real-life phenomena, studying effective treatments, investigating behaviors, and improving lives in other ways. What you decide to research and how you conduct that research involve key ethical considerations.

These considerations work to

- protect the rights of research participants

- enhance research validity

- maintain scientific or academic integrity

Table of contents

Why do research ethics matter, getting ethical approval for your study, types of ethical issues, voluntary participation, informed consent, confidentiality, potential for harm, results communication, examples of ethical failures, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research ethics.

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe for research subjects.

You’ll balance pursuing important research objectives with using ethical research methods and procedures. It’s always necessary to prevent permanent or excessive harm to participants, whether inadvertent or not.

Defying research ethics will also lower the credibility of your research because it’s hard for others to trust your data if your methods are morally questionable.

Even if a research idea is valuable to society, it doesn’t justify violating the human rights or dignity of your study participants.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Before you start any study involving data collection with people, you’ll submit your research proposal to an institutional review board (IRB) .

An IRB is a committee that checks whether your research aims and research design are ethically acceptable and follow your institution’s code of conduct. They check that your research materials and procedures are up to code.

If successful, you’ll receive IRB approval, and you can begin collecting data according to the approved procedures. If you want to make any changes to your procedures or materials, you’ll need to submit a modification application to the IRB for approval.

If unsuccessful, you may be asked to re-submit with modifications or your research proposal may receive a rejection. To get IRB approval, it’s important to explicitly note how you’ll tackle each of the ethical issues that may arise in your study.

There are several ethical issues you should always pay attention to in your research design, and these issues can overlap with each other.

You’ll usually outline ways you’ll deal with each issue in your research proposal if you plan to collect data from participants.

Voluntary participation means that all research subjects are free to choose to participate without any pressure or coercion.

All participants are able to withdraw from, or leave, the study at any point without feeling an obligation to continue. Your participants don’t need to provide a reason for leaving the study.

It’s important to make it clear to participants that there are no negative consequences or repercussions to their refusal to participate. After all, they’re taking the time to help you in the research process , so you should respect their decisions without trying to change their minds.

Voluntary participation is an ethical principle protected by international law and many scientific codes of conduct.

Take special care to ensure there’s no pressure on participants when you’re working with vulnerable groups of people who may find it hard to stop the study even when they want to.

Informed consent refers to a situation in which all potential participants receive and understand all the information they need to decide whether they want to participate. This includes information about the study’s benefits, risks, funding, and institutional approval.

You make sure to provide all potential participants with all the relevant information about

- what the study is about

- the risks and benefits of taking part

- how long the study will take

- your supervisor’s contact information and the institution’s approval number

Usually, you’ll provide participants with a text for them to read and ask them if they have any questions. If they agree to participate, they can sign or initial the consent form. Note that this may not be sufficient for informed consent when you work with particularly vulnerable groups of people.

If you’re collecting data from people with low literacy, make sure to verbally explain the consent form to them before they agree to participate.

For participants with very limited English proficiency, you should always translate the study materials or work with an interpreter so they have all the information in their first language.

In research with children, you’ll often need informed permission for their participation from their parents or guardians. Although children cannot give informed consent, it’s best to also ask for their assent (agreement) to participate, depending on their age and maturity level.

Anonymity means that you don’t know who the participants are and you can’t link any individual participant to their data.

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information—for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, and videos.

In many cases, it may be impossible to truly anonymize data collection . For example, data collected in person or by phone cannot be considered fully anonymous because some personal identifiers (demographic information or phone numbers) are impossible to hide.

You’ll also need to collect some identifying information if you give your participants the option to withdraw their data at a later stage.

Data pseudonymization is an alternative method where you replace identifying information about participants with pseudonymous, or fake, identifiers. The data can still be linked to participants but it’s harder to do so because you separate personal information from the study data.

Confidentiality means that you know who the participants are, but you remove all identifying information from your report.

All participants have a right to privacy, so you should protect their personal data for as long as you store or use it. Even when you can’t collect data anonymously, you should secure confidentiality whenever you can.

Some research designs aren’t conducive to confidentiality, but it’s important to make all attempts and inform participants of the risks involved.

As a researcher, you have to consider all possible sources of harm to participants. Harm can come in many different forms.

- Psychological harm: Sensitive questions or tasks may trigger negative emotions such as shame or anxiety.

- Social harm: Participation can involve social risks, public embarrassment, or stigma.

- Physical harm: Pain or injury can result from the study procedures.

- Legal harm: Reporting sensitive data could lead to legal risks or a breach of privacy.

It’s best to consider every possible source of harm in your study as well as concrete ways to mitigate them. Involve your supervisor to discuss steps for harm reduction.

Make sure to disclose all possible risks of harm to participants before the study to get informed consent. If there is a risk of harm, prepare to provide participants with resources or counseling or medical services if needed.

Some of these questions may bring up negative emotions, so you inform participants about the sensitive nature of the survey and assure them that their responses will be confidential.

The way you communicate your research results can sometimes involve ethical issues. Good science communication is honest, reliable, and credible. It’s best to make your results as transparent as possible.

Take steps to actively avoid plagiarism and research misconduct wherever possible.

Plagiarism means submitting others’ works as your own. Although it can be unintentional, copying someone else’s work without proper credit amounts to stealing. It’s an ethical problem in research communication because you may benefit by harming other researchers.

Self-plagiarism is when you republish or re-submit parts of your own papers or reports without properly citing your original work.

This is problematic because you may benefit from presenting your ideas as new and original even though they’ve already been published elsewhere in the past. You may also be infringing on your previous publisher’s copyright, violating an ethical code, or wasting time and resources by doing so.

In extreme cases of self-plagiarism, entire datasets or papers are sometimes duplicated. These are major ethical violations because they can skew research findings if taken as original data.

You notice that two published studies have similar characteristics even though they are from different years. Their sample sizes, locations, treatments, and results are highly similar, and the studies share one author in common.

Research misconduct

Research misconduct means making up or falsifying data, manipulating data analyses, or misrepresenting results in research reports. It’s a form of academic fraud.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement about data analyses.

Research misconduct is a serious ethical issue because it can undermine academic integrity and institutional credibility. It leads to a waste of funding and resources that could have been used for alternative research.

Later investigations revealed that they fabricated and manipulated their data to show a nonexistent link between vaccines and autism. Wakefield also neglected to disclose important conflicts of interest, and his medical license was taken away.

This fraudulent work sparked vaccine hesitancy among parents and caregivers. The rate of MMR vaccinations in children fell sharply, and measles outbreaks became more common due to a lack of herd immunity.

Research scandals with ethical failures are littered throughout history, but some took place not that long ago.

Some scientists in positions of power have historically mistreated or even abused research participants to investigate research problems at any cost. These participants were prisoners, under their care, or otherwise trusted them to treat them with dignity.

To demonstrate the importance of research ethics, we’ll briefly review two research studies that violated human rights in modern history.

These experiments were inhumane and resulted in trauma, permanent disabilities, or death in many cases.

After some Nazi doctors were put on trial for their crimes, the Nuremberg Code of research ethics for human experimentation was developed in 1947 to establish a new standard for human experimentation in medical research.

In reality, the actual goal was to study the effects of the disease when left untreated, and the researchers never informed participants about their diagnoses or the research aims.

Although participants experienced severe health problems, including blindness and other complications, the researchers only pretended to provide medical care.

When treatment became possible in 1943, 11 years after the study began, none of the participants were offered it, despite their health conditions and high risk of death.

Ethical failures like these resulted in severe harm to participants, wasted resources, and lower trust in science and scientists. This is why all research institutions have strict ethical guidelines for performing research.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Cohort study

- Peer review

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Ethical considerations in research are a set of principles that guide your research designs and practices. These principles include voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, potential for harm, and results communication.

Scientists and researchers must always adhere to a certain code of conduct when collecting data from others .

These considerations protect the rights of research participants, enhance research validity , and maintain scientific integrity.

Research ethics matter for scientific integrity, human rights and dignity, and collaboration between science and society. These principles make sure that participation in studies is voluntary, informed, and safe.

Anonymity means you don’t know who the participants are, while confidentiality means you know who they are but remove identifying information from your research report. Both are important ethical considerations .

You can only guarantee anonymity by not collecting any personally identifying information—for example, names, phone numbers, email addresses, IP addresses, physical characteristics, photos, or videos.

You can keep data confidential by using aggregate information in your research report, so that you only refer to groups of participants rather than individuals.

These actions are committed intentionally and can have serious consequences; research misconduct is not a simple mistake or a point of disagreement but a serious ethical failure.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 24, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/research-ethics/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, data collection | definition, methods & examples, what is self-plagiarism | definition & how to avoid it, how to avoid plagiarism | tips on citing sources, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Board Members

- Management Team

- Become a Contributor

- Volunteer Opportunities

- Code of Ethical Practices

KNOWLEDGE NETWORK

- Search Engines List

- Suggested Reading Library

- Web Directories

- Research Papers

- Industry News

- Become a Member

- Associate Membership

- Certified Membership

- Membership Application

- Corporate Application

- CIRS Certification Program

- CIRS Certification Objectives

- CIRS Certification Benefits

- CIRS Certification Exam

- Maintain Your Certification

- Upcoming Events

- Live Classes

- Classes Schedule

- Webinars Schedules

- Latest Articles

- Internet Research

- Search Techniques

- Research Methods

- Business Research

- Search Engines

- Research & Tools

- Investigative Research

- Internet Search

- Work from Home

- Internet Ethics

- Internet Privacy

Research Ethics and Plagiarism: What We Need to Know

Research ethics are like a moral compass that guide researchers in their pursuit of knowledge. They ensure that research is conducted in a responsible and ethical manner, and that the knowledge gained from research is used for the betterment of society.

The principles of research ethics

One of the core principles of research ethics is respect for individuals. This means that researchers must always treat their study participants with dignity and respect, and that they must obtain informed consent from all participants before the research begins. For example, a study on the effects of a new drug might involve obtaining informed consent from patients who are willing to participate in the study.

In addition to these core principles, ethics also involve ensuring that researchers are honest and transparent in their reporting of their findings. This means that researchers must avoid plagiarism, accurately report their methods and results, and always acknowledge the contributions of others..

Avoiding plagiarism

Learn about the ways to avoid plagiarism in your work:

Use quotation marks or block quotes for direct quotes. If you're using someone else's exact words, make sure to put them in quotation marks or use a block quote to clearly indicate that they're not your own words.

Paraphrase and summarize in your own words. Instead of copying someone else's work word-for-word, try to summarize or paraphrase the information in your own words. Just make sure to still give credit to the original author.

Use proper citation and referencing. Make sure to cite your sources and give credit to the authors whose work you're referencing. Use the appropriate citation style for your field, such as APA or MLA.

Use plagiarism detection tools. Many online tools can help you check your work for plagiarism before submitting it. You can use a plagiarism checker no word limit and check if you’ve used phrases similar to someone’s. By checking your work before submission, you can identify any problematic areas and make the necessary revisions to ensure that your writing is original and properly cited.

Stay organized. Keeping track of your sources and notes can help you avoid confusion and ensure that you properly cite all of your sources.

Following research ethics

For instance, let's say you're working on a research project about the effects of climate change on local wildlife. Following research ethics would involve treating your study participants with respect and dignity, obtaining informed consent, and taking measures to avoid causing physical or emotional harm. By doing so, you can ensure that your findings are valid and that your study contributes to society in a meaningful way.

What you must know as a student

Here's a list of things every student must know about research ethics and plagiarism:

- The principles of research ethics, including:

- respect for individuals

- avoiding harm

- being honest and transparent in reporting findings.

- The importance of obtaining informed consent and protecting the privacy and confidentiality of study participants .

- The consequences of plagiarism. These include academic penalties and damage to personal and professional reputation.

- The importance of citing sources and giving credit to the work of others, as well as avoiding self-plagiarism.

- The different types of plagiarism, such as:

- direct copying

- paraphrasing without citation

- purchasing or sharing papers.

- The resources available to help students avoid plagiarism, including plagiarism checkers and citation management tools.

- The role of academic integrity in building a successful career and contributing to society in an ethical and responsible way.

Final thoughts

Author’s bio, live classes schedule.

World's leading professional association of Internet Research Specialists - We deliver Knowledge, Education, Training, and Certification in the field of Professional Online Research. The AOFIRS is considered a major contributor in improving Web Search Skills and recognizes Online Research work as a full-time occupation for those that use the Internet as their primary source of information.

Get Exclusive Research Tips in Your Inbox

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Advertising Opportunities

- Knowledge Network

Understanding Research Ethics: How to Prevent Plagiarism

Session Agenda

Responsible conduct of research is quintessential in maintaining scientific integrity. Researchers either intentionally or negligently may adopt questionable research practices leading to detrimental consequences. To minimize the risks and hazards associated with unethical behavior, researchers must be aware of the various types of research misconduct and the ways to avoid these malpractices. Enago in collaboration with Hindawi conducted a joint webinar to uphold scientific integrity by helping research scholars understand the significance of good ethical conduct. We focussed on explaining the most common type of research misconduct—plagiarism and its different forms and have shared effective strategies to prevent it.

Through this session, researchers will have an improved understanding of the following:

- An overview of research and publication ethics

- Importance of research ethics

- Major ethical issues and how to avoid them

- How to draft plagiarism-free manuscripts?

- Legal consequences of IPR violation

About Hindawi ( www.hindawi.com )

Hindawi Limited is one of the world's largest open-access publishers with an expansive portfolio of academic research journals across all areas of science and medicine. Each peer-reviewed journal has been developed in partnership with academic researchers, acting as editors, to fit the targeted communities they serve. Driven by a mission to advance openness in research and placing the researcher at the heart of everything we do, we work with publishers, institutions, and organizations to move towards a more open scholarly ecosystem by investing in the development of open-source publishing infrastructure.

Who should attend this session?

- Graduate students

- Early-stage researchers

- Doctoral students

- Postdoctoral students

- Established researchers

About the Speaker

About the speakers.

Michael Gotesman, Scientist & Educator

Ben Dickinson, Research Integrity Manager, Hindawi

Related Events

생명윤리: 의학과 과학의 사회적 & 윤리적 문제 해결

- 생명윤리와 생명윤리 원칙

- 정책의 결정 및 유지

- 생명과학 연구의 윤리적 문제

- 생명윤리 정보 리소스

Launching ‘Review Assistant’: An AI-powered Tool for Peer Reviewers

- Boosting the reviewing process

- Search strategies for locating articles

- Introducing ‘Review Assistant’

- Reporting high-quality reviews

How to Boost Citations – Tips for Researchers

- Acknowledging the sources

- Significance of research promotion

- Strategies to boost citations

- Impact of promotional strategies

Register Now for FREE!

Register now.

- Personal Details

- Card Details

Want to conduct custom webinars and workshops ?

Be our next speaker.

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

Plagiarism in research

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Learning, Informatics, Management and Ethics, Stockholm Centre for Healthcare Ethics, Karolinska Institutet, 171 77, Stockholm, Sweden, [email protected].

- PMID: 24993050

- DOI: 10.1007/s11019-014-9583-8

Plagiarism is a major problem for research. There are, however, divergent views on how to define plagiarism and on what makes plagiarism reprehensible. In this paper we explicate the concept of "plagiarism" and discuss plagiarism normatively in relation to research. We suggest that plagiarism should be understood as "someone using someone else's intellectual product (such as texts, ideas, or results), thereby implying that it is their own" and argue that this is an adequate and fruitful definition. We discuss a number of circumstances that make plagiarism more or less grave and the plagiariser more or less blameworthy. As a result of our normative analysis, we suggest that what makes plagiarism reprehensible as such is that it distorts scientific credit. In addition, intentional plagiarism involves dishonesty. There are, furthermore, a number of potentially negative consequences of plagiarism.

- Ethical Analysis

- Ethics, Research*

- Plagiarism*

Research Ethics and Plagiarism

"Research Ethics and Plagiarism" are among the key areas under discussion and consideration at various levels. Many students of PG programmes. Research scholars and faculty members of higher education Institutions face problem to resolve the issues related to plagiarism. In 2018, UGC has also notified its norms for plagiarism checking and promoting ethical practices in research and publications. In these norms, Universities/institutions are asked to organize programmes and make these issues as part of their research curriculum. Keeping in mind the vast scope of the area and opportunities for young researchers to learn about research ethics, plagiarism, citation, etc. this online course entitled "Research Ethics and Plagiarism" i s being offered.

Page Visits

Course layout, instructor bio.

Dr. Gaurav Singh

Dr.Gaurav Singh is working as a Professor at School of Education, Central University of Haryana. Previously, he has contributed at IGNOU as the coordinator the Bachelor of Education (B.Ed.) Programme. He was the Channel Coordinator of SWAYAMPRABHA Channel:32 Teacher Education (A Ministry of Education, Govt. of India Project) July 2016-June 2020, and of Channel 20: SOUs and Teacher Education under SWAYAMPRABHA till September 05, 2022. Dr.Gaurav Singh has done M.Sc. in Chemistry, M.Ed. (Gold Medallist), UGC-NET (Education) and Ph. D. in Teacher Education and also completed PGDDE (Gold Medal). He started his career as teacher educator in 2003 in a conventional teacher education Institute and worked with School of Education, IGNOU from November 2011 to September 04, 2022. His 31 (Thirty-One) research papers/ articles have been published so far in various National and International Journals/books. He has also contributed more than 40 chapters/units to ODL Study Material. He has recorded/developed 125 modules/lectures for MOOCs till date and coordinated the development of nearly 1200 lectures for SWAYAM and SWAYAMPRABHA. He has authored one book on Teacher Education and guided one Ph.D. on E-learning. Dr. Singh has participated in various International and National Seminars in India as well as abroad. He has also completed one NIOS funded Research Project as Co-Researcher on Educational Status of Purvi Uttar Pradesh. He is offering four MOOCs on SWAYAM and on other platforms. Nearly 45000 learners have benefited from these courses so far. His SWAYAM course on Research Ethics and Plagiarism has been adopted by nearly forty universities in their Ph.D. Course work curriculum, and under top ten SWAYAM courses of all time, as per the learners rating on class central. Dr.Gaurav Singh is the recipient of Commonwealth of Learning-AAOU Fellowship-2018 by COL, Vancouver, Canada. He has been conferred silver medal of Best Practices by Asian Association of Open Universities (AAOU), 2018 at Hanoi, Vietnam and is recipient of Distinguished Distance Educator Award by National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS), Noida. He has also got travel assistance to attend Pan Commonwealth Forum (PCF-10) from COL at Athabaska University Calgary, Canada in 2022. His SWAYAM course on Learning and Teaching has been awarded as the Best SWAYAM course in 2021. Dr. Gaurav Singh is continuously engaged in delivering lectures/talks and organizing training workshops as MOOC trainer at various universities, TLCs, HRDCs and teacher education Institutions. He has been part of various academic bodies, curriculum committees of several Institutions and Universities. His areas of interests are Research Methodology, ICTs in Education/ODL and Teacher Education.

Course certificate

DOWNLOAD APP

SWAYAM SUPPORT

Please choose the SWAYAM National Coordinator for support. * :

The Homo Economicus as a Prototype of a Psychopath? A Conceptual Analysis and Implications for Business Research and Teaching

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 22 March 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Florian Fuchs ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1163-0107 1 &

- Volker Lingnau 1

Since the beginning of business research and teaching, the basic assumptions of the discipline have been intensely debated. One of these basic assumptions concerns the behavioral aspects of human beings, which are traditionally represented in the construct of homo economicus. These assumptions have been increasingly challenged in light of findings from social, ethnological, psychological, and ethical research. Some publications from an integrative perspective have suggested that homo economicus embodies to a high degree dark character traits, particularly related to the construct of psychopathy, representing individuals who are extremely self-centered and ruthless, without feelings of remorse or compassion. While a growing body of research notes such a similarity on a more or less anecdotal basis, this article aims to explore this connection from a more rigorous perspective, bridging insights from psychological, economic, and business research to better understand the potentially dark traits of homo economicus. The analysis shows that homo economicus is not simply some kind of psychopath, but specifically a so-called subclinical or Factor 1 psychopath, who is also referred to as a “corporate psychopath” in business research. With such an analysis, the paper adds an additional perspective and a deeper psychological level of understanding as to why homo economicus is often controversially debated. Based on these insights, several implications for academic research and teaching are discussed and reflected upon in light of an ethics of virtue and care.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

From the perspective of the philosophy of science, each scientific discipline is characterized by some basic assumptions. In disciplines such as philosophy, anthropology, sociology, but also in business research and economics, the assumed concept of a human being (“ Menschenbild ,” see, e.g., Zichy, 2020 ) is one of these fundamental assumptions. While in philosophy since the Enlightenment a human being is conceived of as a rational actor in a very broad sense, also from a moral capabilities perspective (e.g., in Kant’s moral philosophy), in traditional theoretical models of economics and business this rationality has been strongly narrowed to a ruthless, selfish pursuit of material benefits. This sole, opportunistic pursuit of material advancement is well reflected in the concept of homo economicus, the standard concept of an actor in neoclassical economics.

Interestingly, the core dispositions and motivations of homo economicus have been debated since the creation of the concept in the nineteenth century. In particular, it often has been noted that the homo economicus’ motivational dispositions, which have been made the foundation of orthodox economics, i.e., ruthless selfishness and greed, would be theologically considered as cardinal or mortal sins (Martinás, 2010 ; Verburg, 2018 ; Zamagni, 2011 ). Beyond such a moral analysis, in the last decade, some publications have stated that homo economicus seems to incorporate dark character traits, and especially signs of psychopathy (e.g., Bailey, 2017 ; Davies, 2016 ; Hoffman, 2011 ; Stout, 2014 ). Yet, there has been very little systematic and deeper psychological investigation into the core traits of homo economicus. Such an analysis appears to be relevant for a number of reasons. First of all, the concept of homo economicus is still critically discussed in contemporary business ethics research as a questionable model for human behavior (e.g., Friedland & Cole, 2019 ; Haarjärvi & Laari-Salmela, 2022 ; Racko, 2019 ). A psychological analysis could provide an additional, highly interesting perspective to this ongoing discussion. Furthermore, homo economicus, even if not always made explicit, is still prevalent in fundamental economic, managerial, and organizational theories (Melé & Cantón, 2014 ). Although business research applies a variety of methods and theoretical backgrounds, the homo economicus concept is, for instance, the basis of microeconomic firm profit or individual utility maximization (e.g., Parkin, 2014 ; Pindyck & Rubinfeld, 2018 ). Likewise, key behavioral dispositions of homo economicus are reflected in principal-agent theory (Gintis & Khurana, 2016 ). With regard to capital markets, traditional instruments like the Capital Asset Pricing Model are built on assumptions of economic rationality (Baker & Ricciardi, 2014 ). Moreover, the concept is generally the basis for rational choice theory (e.g., Gilboa, 2012 ) and therefore part of all approaches based on this concept, which especially holds for a great number of analytical research that relies on formal modeling. Finally, besides economics and business, the concept has also been adopted in other disciplines like sociology, politics, or law (e.g., Guzman, 2008 ; Hechter & Kanazawa, 1997 ; Parsons, 2005 ; Zafirovski, 2014 ).

As this paper argues, the fundamental selection of models is not just a theoretical issue, these choices also matter in practice. Specifically, the arguments that homo economicus “is just a model” or “it’s simply an ‘as if’ assumption” with some predictive value (e.g., Friedman, 1976 ), fall short for several reasons (also see Dosi et al., 2021 ). Besides the counterargument that such an “as if” approach would not do sufficient justice to supporting the study of a real decision-maker, there is an even potentially stronger argument with regard to the real-world implications of model choices on business and policy-making processes, on which this paper will elaborate. In such vein, the paper is not only solely theoretically insightful but also creates several links to practice. Although homo economicus is evidently not a real person, it is not solely an abstract, imaginative concept detached from any impact on reality. Rather, it represents a distinct artifact of thinking about basic rules in business and human interaction in general, which also reflects back on and influences the reasoning and acting in these contexts (Linstead & Grafton-Small, 1990 ). This has several implications. First of all, as will be discussed, homo economicus still reverberates in corporate practice, for instance in competitive, individualistic environments and monetary incentive schemes. Equally, when academic theory is applied in practice, like in cases of economic deregulation, the implied concept of a human being matters (e.g., Fridman, 2010 ). In addition, the findings of this paper are also insightful with regard to academic teaching. As several studies have shown, teaching conveys certain basic values—at least implicitly, simply by the fact of model choice and the implied concept of humanity that was chosen (e.g., Frank et al., 1993 ; Ifcher & Zarghamee, 2018 ; Kowaleski et al., 2020 ; Racko, 2019 ). In such vein, for instance, the last financial crisis has been linked to at least implicitly taught values associated with homo economicus (Giacalone & Wargo, 2009 ; Melé, 2009 ; Melé et al., 2011 ). Also from a wider perspective, several corporate scandals with far-reaching organizational and societal consequences are discussed as being, at least partly, caused by internalizing economic rationality, and homo economicus as a representation of such rationality (Ong et al., 2022 ). Based on these considerations, several authors have called for a critical examination of the academic curricula for teaching business (Dierksmeier, 2011 ; Fougère & Solitander, 2023 ; Giacalone & Wargo, 2009 ; Gintis & Khurana, 2016 ; Waddock, 2020 ). Given the continuing criticism of homo economicus and the lack of systematic deeper analyses with regard to the potentially dark traits of this model, this paper conducts an analysis from a more rigorous psychological perspective.

As such, the paper is structured as follows. In the beginning, the paper will conduct a short review of the two major notions, i.e., first, the concept of homo economicus and second that of psychopathy is discussed. After presenting the two major concepts, both lines of thought are combined and homo economicus is systematically analyzed through a psychological lens. As a major finding, this paper shows that the core traits of homo economicus as an emotionally shallow, selfish, opportunistic, and manipulative agent can be psychologically described as psychopathic. Specifically, homo economicus shows strong traits of so-called subclinical psychopathy, which relates to the notion of corporate psychopathy widely applied in business research. After discussing this finding, several implications for business research and teaching are reflected upon through the lens of an ethics of virtue and care.

The Concept of Homo Economicus

Although an early discussion of traits resembling the concept later coined “homo economicus” can be traced back to the antiquities (Dixon & Wilson, 2012 ), the notion is particularly linked to the advent of the classic economic theory in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. According to the seminal review by Persky ( 1995 ), it was shaped by John Stuart Mill, postulating that economic analysis should restrict itself to the concept of an agent primarily motivated by “the desire of wealth, [.] aversion to labour, and desire of the present enjoyment […]” (Mill, 1844 , p. 138). Yet, the exact terminology was only later introduced by authors like John Kells Ingram and John Neville Keynes in their critical discussion of Mill’s economic groundwork. Subsequently, it has been frequently assumed that the concept was strongly influenced by the work of Adam Smith given that in his Wealth of the Nations (Smith, 1804 ), he argues that economic exchange shall be seen primarily in light of mutual self-interest instead of social motives such as altruism. This view is, however, for its simplicity challenged by the newer Adam Smith research (e.g., Hühn & Dierksmeier, 2016 ), particularly with regard to his second groundbreaking and potentially complementary work on The Theory of Moral Sentiments (Smith, 1761 ). A great leap in the development of the modern understanding of homo economicus is provided by the development of neoclassical economics with a stronger emphasis on mathematical formalization, which in turn was heavily influenced by physics, and in specific, deterministic mechanics and thermodynamic equilibrium theory (Smith & Foley, 2008 ). With regard to the “forces” leading to economic equilibria, self-interest coupled with a possession of complete information became the standard doctrine of economic models in neoclassical approaches. These assumptions are embedded in the concept of homo economicus as an agent solely concerned with maximizing utility while possessing a temporally stable preference structure. This structure is independent of others—or to say more precisely: covers the needs of others only to such an extent as these others are deemed beneficial to the homo economicus’ own ends (Kirchgässner, 2008 ). The rationality of homo economicus is therefore strictly based on the own benefit and represents a thinking in purpose-means relationships (Anderson, 2000 ; Elster, 1989 ). Although it is sometimes argued that the model of homo economicus could be conceived of as being concerned with the satisfaction of arbitrary, e.g., also altruistic, needs (England, 2003 ), like in the works of Becker ( 1981 , 1993 ), such an extension to the satisfaction of all conceivable preferences falls short in at least two respects. First, defining all actions as utility maximizing makes the model a tautology where every conduct is ex-post explained by utility, thus lacking any analytical sharpness, being factually non-testable and logically circular (Ostapiuk, 2021 ; Stout, 2014 ). Second, from a conceptual point of view, the homo economicus model is de facto often understood as narrowed to the traditional, already elaborated motives (England, 2003 ): a maximization of material benefits, as for instance measured in discounted cash flows or net present value as a traditional measure of rational decision-making (Magni, 2009 ). As such, homo economicus is a “single-minded income-maximizing economic actor” (Pearlstein, 2016 ) or as Fleming ( 2017 , p. 98) puts it, a “dollar-hunting animal” represented in “the monetised principle of pure utility.”

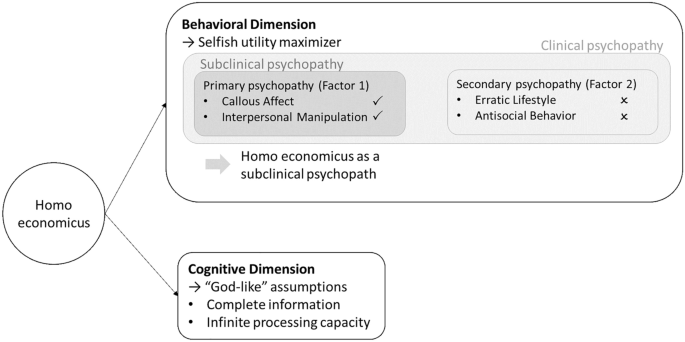

Moreover, the academic examination is frequently limited insofar as the controversies often mix two distinct features of homo economicus, which, if not clearly disentangled, blurs the debate on the concept and which this paper therefore shall delineate more precisely: namely a cognitive and a behavioral assumption of the model. In the cognitive dimension, the information status and computational capabilities of the actor are covered. In such vein, it is assumed that homo economicus possesses complete information, has no restrictions in computation, and can adapt at infinite speed to a change in information. Unsurprisingly, these evidently stark assumptions have been heavily criticized, particularly in the domain of bounded rationality research initiated by Herbert Simon, who harshly criticized the God-like, “Olympian model” (Simon, 1983 , p. 34) of homo economicus, which he assigned to “Plato’s heaven of ideas” (p. 13). In contrast, Simon’s groundbreaking work emphasizes that human individuals are not fully knowledgeable and deviate from the standard economic maximization paradigm by “satisficing” (i.e., being satisfied with an achievement of a previously defined “good” result level) instead of “optimizing,” which has in consequence inspired several streams of research until present day (also see Simon, 1983 ). These are, for instance, the “biases and illusions” research by Kahneman and Tversky, which investigates the deviation from standard economic rationality as cognitive biases, mostly in experimental contexts (e.g., Kahneman, 2012 ; Kahneman & Tversky, 1979 ; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974 ), and the field of “ecological rationality” in the tradition of Gigerenzer, emphasizing in opposition to the “biases and illusions” research that heuristic approaches often deliver good solutions in real problem solving situations, i.e., under consideration of the real problem environment (e.g., Gigerenzer, 2004 ; Gigerenzer & Brighton, 2009 ; Gigerenzer & Gaissmaier, 2011 ; Gigerenzer & Goldstein, 2016 ).

Besides these cognitive assumptions, even more interesting for the present paper are the behavioral assumptions of the homo economicus model. From this view, homo economicus can be linked back to the original considerations debated in the context of Mill’s economic theory, i.e., an individual’s conduct that is structured by a strict pursuit of self-interest, as said, mostly reduced to material benefits to avoid a motivationally arbitrary and tautological model. Given the total absence of any genuine social concerns, the model is based on an opportunistic exploitation of any options available to increase personal wealth. The individual advantage is therefore pursued without empathy, feelings of remorse or guilt, any feelings for others at all, and only based on the prospect of a possible enrichment. These characteristics are widely reflected in information economics (e.g., Birchler & Bütler, 2007 ; Macho-Stadler & Pérez-Castrillo, 2001 ), for instance in the context of adverse selection or hidden action, and considerations on the importance of designing incentive and control systems (see e.g., Merchant & Van der Stede, 2017 ) to limit discretionary behavior (Picot et al., 2008 ). These assumptions also have been strongly contested from an empirical perspective. In particular, behavioral research has emphasized the importance of not neglecting stable social traits such as altruism, fairness, or reciprocity (Bolton & Ockenfels, 2000 ; Bolton et al., 2005 ; Fehr & Fischbacher, 2002 ; Fehr & Schmidt, 2006 ; Fischbacher et al., 2001 ; Gächter & Falk, 2002 ). The restriction to a ruthless, selfish, and opportunistic conduct, seeing others merely as a means to maximize the own advantage, has led to a widespread criticism of orthodox economics as a “dismal science” (Aldred, 2009 ; Brue & Grant, 2013 ; Levy, 2002 ; Marglin, 2008 ). However, still, a more systematic analysis of these assumptions from the perspective of dark character traits, and psychopathy in particular, needs to be conducted.

The Concept of Psychopathy

As a first general definition, the notion of psychopathy refers to a “distinct psychiatric illness marked by serious behavioral deviancy in the context of intact rational function” (Patrick, 2018 , p. 4). According to Hare ( 1999 , p. 34) psychopathy must be considered a syndrome, i.e., “a cluster of related symptoms,” as shown in a morally deviant, ruthless, and selfish conduct. It is important to note that in comparison to insanity or madness, psychopaths commit their moral transgressions and crimes in full clarity of conduct—they simply do not care for others and the harm inflicted on them (Glenn et al., 2009 ). Interestingly, from the first concepts specifying psychopathy in the nineteenth century and until recent times, a wide range of psychological research has focused on the so-called clinical psychopath , an individual who not only lacks any affection and empathy for others but likewise shows a serious lack of long-term-oriented conduct and behavioral control, leading to an unsteady life and frequent unrestrained outbursts of physical violence. As a result, these individuals tend to come into conflict with the law at an early age and often face imprisonment (Hare & Neuman, 2008 ). However, not all psychopaths are impaired in this way. Rather, there are individuals who possess some of the core traits of clinical psychopathy and yet are able to lead seemingly normal lives, be at first glance likable and charming, and even succeed in their individual careers. These individuals are referred to as subclinical psychopaths . This fact is summarized in the famous quote by Hare stating: “Not all psychopaths are in prison. Some are in the Boardroom” (as cited in Babiak et al., 2010 , p. 174).

From a research perspective, the existence of such subclinical psychopaths has stirred increasing academic interest in recent decades, particularly in light of some spectacular collapses of once prestigious companies due to massive levels of executive misconduct and fraud (Lingnau et al., 2017 ). Interestingly, the prevalence of subclinical psychopaths has also been suggested as a reason for the last financial crisis (Boddy, 2011 ; Gregory, 2014 ; Marshall et al., 2013 ). To better understand the underlying phenomenon, it is helpful to deeper investigate the characteristics of psychopathy as a construct of two major, overarching factors (Babiak, 2016 ). Such a differentiation began with the seminal work by Cleckley ( 1941 ), who not only developed the modern concept of psychopathy by elaborating several core aspects of the syndrome but already noted that there are some individuals with psychopathic traits that could be highly successful in their careers. This research inspired Hare ( 1980 ) to develop the Psychopathy Checklist (PCL), which extended Cleckley’s notion with some additional, especially antisocial, tendencies often found in institutionalized psychopaths (Hare & Neumann, 2005 , 2008 ). This scale was later revised to the PCL-R (Hare, 2003 ). In addition to its widespread use in the detection of psychopathy (e.g., Acheson, 2005 ; Falkenbach, 2007 ; Fritzon et al., 2020 ; Lynam, 2011 ), the PCL-R is also noteworthy because its empirical application has helped to shape a deeper conceptual understanding of the construct of psychopathy itself. Specifically, the empirical application revealed that the construct is composed of several subfactors that are insightful for classification, as the following discussion will show. As such, the PCL-R shows two major dimensions, or overarching factors of psychopathy, which can be further differentiated into two subfactors (Hare & Neumann, 2005 , 2008 ) (see Table 1 and Fig. 1 ).

Cognitive and behavioral dimension of homo economicus

The first major factor of psychopathy refers to an interpersonal and affective dimension. In the affective dimension ( callous affect ) these individuals are extremely ruthless and coldhearted, showing a deficiency in emotional responses, particularly when others are harmed. They are further lacking any conscience, feelings of guilt or remorse, and do not take responsibility for their actions. The second subfactor of the first dimension is interpersonal manipulation . I.e., such individuals do not refrain from using and misusing others to reach their goals, which also includes deceitful behavior like cheating and lying on a habitual basis. This is especially easy for psychopaths because they feel less cognitive dissonance in doing so (Murray et al., 2012 ). Although individuals with such trait may appear likable and charming at first glance, they are entirely self-focused and do not care about others, merely using them for personal advantage. Therefore and in summary, individuals with an elevated Factor 1 are characterized by superficial charm, an extreme lack of empathy or compassion, leading to a ruthless, manipulative conduct without feelings of shame, remorse, or guilt (Hare & Neumann, 2005 , 2008 ). Besides Factor 1 as a core element of the notion of psychopathy (Harpur et al., 1989 ; Herpertz & Sass, 2000 ), Factor 2 characterizes issues with an individual’s long-term planning and behavioral control, leading to an unsteady lifestyle, impulsive thoughtlessness, generally openly displayed irresponsible and antisocial conduct, and therefore most often early delinquency. This second factor can be differentiated in an erratic lifestyle , particularly focusing on a lack of long-term-oriented conduct and an unsteady life, and antisocial behavior , as for instance represented in violent outbursts and law-breaking, leading to early criminal behavior (Hare & Neumann, 2005 , 2008 ).

It is worth noting that there has been some discussion on the latter subfactor. As such, Cooke and Michie ( 2001 ) have argued for a three-factor model that drops the subfactor of antisocial behavior because this factor includes blue-collar crime tendencies, which they argue to be consequences of traits and not the traits themselves. However, as Hare and Neumann ( 2005 , 2008 ) argue in return, dropping out antisocial behavior would also exclude relevant aspects such as poor behavioral control typical of clinical psychopaths. In this paper, we cannot attempt to remedy such internal psychological discussion. However, as we shall discuss, there are some good reasons to apply the 2 by 2 model in the following analysis. First, it may be highly interesting to evaluate homo economicus also in terms of the behavioral control aspect, which would be excluded if the antisocial behavior subfactor were not examined. Such an aspect seems worth discussing with homo economicus and provides a deeper analysis. Moreover, this model is useful for distinguishing between clinical and subclinical psychopathy (Babiak, 2016 ), which, as the following analysis shows, is very insightful. With regard to such model, the traditional concept of psychopathy, i.e., clinical psychopathy , refers to individuals with a substantially elevated Factor 1 and Factor 2 . Consequently, these are ruthless and coldhearted individuals with considerable behavioral problems and an unsteady lifestyle. In contrast, subclinical psychopaths , who are particularly interesting from a business research perspective, show an equally profoundly elevated Factor 1 but, at most, only a mildly elevated Factor 2 (Babiak, 2016 ). These individuals are therefore extremely coldhearted, opportunistic, and without remorse or guilt. Yet, they can plan very strategically and possess a relatively normal behavioral control, enabling them to appear even as charming and likable at first glance as they are masters of concealing their dark traits. As a result, such individuals are frequently able to climb the corporate ladder, which is especially propelled in Western cultures (Boddy et al., 2010a ; Stout, 2005 ). This is facilitated by an increasing expectation of frequent job changes in leadership positions (Boddy et al., 2021 ) and internally as well as externally often turbulent, competitive business environments. The ascent of such individuals is also confirmed in several empirical investigations. For example, Babiak et al. ( 2010 ) found that up to 6% of top managers showed psychopathic traits while Fritzon et al. ( 2017 ) found even 21% of managers to display substantially elevated psychopathic traits in the supply chain context. In comparison, the prevalence in the general population is merely about 1%. These subclinical psychopaths are referred to by a variety of terms. Besides the simple term as a “ Factor 1 psychopath,” they are also referred to as “organizational psychopath” (e.g., Boddy, 2006 ), “executive psychopath” (e.g., Morse, 2004 ), “corporate psychopath” (Babiak & Hare, 2019 ; Boddy, 2005 ; Brooks et al., 2020 ; Lingnau et al., 2017 ), or “successful psychopath” (e.g., Benning et al., 2018 ; Board & Fritzon, 2005 ; Hare & Neumann, 2008 ; Hervé, 2007 ; Weber et al., 2008 ). In the following, we will refer to these individuals primarily as “corporate psychopaths.”

Analysis of Homo Economicus on Psychopathy

In order to systematically analyze the concept of homo economicus with regard to psychopathic traits, the PCL-R will be applied. As such, in the dimension of primary psychopathy, the first subfactor to be analyzed is callous affect , which refers to a deficiency in emotional responses, i.e., showing a shallow affect, no empathy with others, a lack of remorse or guilt, and not taking responsibility. Looking at the discussion of homo economicus in the literature, already Boulding ( 1969 , p. 10) identified the concept of homo economicus as someone who “counted every cost and asked for every reward, was never afflicted with mad generosity or uncalculating love, and who never acted out of a sense of inner identity and indeed had no inner identity even if he was occasionally affected by carefully calculated considerations of benevolence or malevolence.” Similarly, also Homans ( 1961 , p. 79) concluded that the homo economicus essentially was “antisocial and materialistic, interested only in money and material goods and ready to sacrifice even his old mother to get them.” Finally, Sen ( 1977 , p. 336) famously labeled the homo economicus a “rational fool” and a “social moron.” Also in newer publications, the callousness of homo economicus has been noted by emphasizing an extreme level of selfishness, i.e., homo economicus cares only about the personal utility and is therefore indifferent toward the needs of others, as long as these others are not necessary to advance the own benefits (Boddy, 2023 ; Kirchgässner, 2008 ). In such a reckless pursuit of self-interest, there is also no place for conscience, guilt, feelings of duty, and remorse, which represents a high degree of emotional detachment from others (Baron, 2014 ; Lingnau et al., 2017 ; Ogaki & Tanaka, 2019 ; Stout, 2012 ). As a result, “homo economicus is a clinical calculator of his own advantage, a ruthless pursuer of his own interest […]” (Mell & Walker, 2014 , p. 17). Homo economicus “has no moral compunction, does not engage in actions just because some abstract social norms require doing so” and has no “feelings of guilt” (Ben-Ner & Putterman, 1998 , p. 18). Lastly, concerning the aspect of taking responsibility, it is clear that homo economicus is ruthless and has “no responsibility for anyone” (Nelson, 1993 , p. 292), except for potentially optimizing the own benefit. Thus, there is no genuine “responsibility for other people and future generations” (Siebenhüner, 2000 , p. 18). Summarizing these statements, one can subsume that homo economicus shows a high degree of callous affect.

The second subfactor to be discussed is interpersonal manipulation , which comprises aspects of glib, superficial charm, a sense of grandiosity, pathological lying, and the tendency to manipulate others in order to achieve personal goals. Looking at the literature, homo economicus does not maintain genuine and deep personal relationships. As Davies ( 2016 , p. 61) subsumes: “ Homo economicus doesn’t have friends.” Rather, the instrumental rationality of homo economicus leads to a superficial interaction with others, which Dobuzinskis ( 2019 , p. 105) describes as “all too glib.” The core traits of manipulative and untrustworthy conduct of this subfactor are well reflected in principal-agent theory stating that a principal has to assume untruthful reports and a general lack of commitment by an agent (Picot et al., 2008 ). In such vein, it can be stated with Williamson ( 1985 , p. 51) that homo economicus will regularly apply “the full set of ex ante and ex post efforts to lie, cheat, steal, mislead, disguise, obfuscate, feign, distort, and confuse,” as long as such promises the realization of personal gain. Similarly, Hunt and Vitell ( 2015 , p. 34) pointedly state that “ homo economicus not only maximizes self-interest but does so with opportunistic ‘guile’.” Thus, homo economicus is “designed to cheat, lie, and exploit” (Dash, 2019 , p. 26). Lastly, although homo economicus is evidently not designed as a Narcissist with a need for social affirmation (e.g., Miller et al., 2021 ), some sense of grandiosity implied in the model could be seen in the quote by Sen ( 1977 , p. 336) stating that homo economicus is not only a “rational fool” but also “decked in the glory of his one all-purpose preference ordering.” In summary, the second subfactor is also well represented within the homo economicus model. It can be subsumed that homo economicus is extremely selfish, and merely considers others as a means to personal enrichment, also habitually applying methods of lying and cheating, using and misusing others to achieve personal benefit. Thus, in conclusion, both subfactors, i.e., callous affect and interpersonal manipulation are well echoed in the concept of homo economicus. Consequently, homo economicus represents to a large degree traits of the Factor 1 of psychopathy.

With respect to the Factor 2 of psychopathy, the first subfactor is erratic lifestyle comprising stimulation seeking, impulsive, short-term-oriented behavior, careless, irresponsible conduct, a lack of realistic goals, and a tendency toward a parasitic lifestyle. As a first aspect, stimulation seeking refers to the propensity to be easily bored and thus to seek out tense situations, such as regular participation in risky activities like skydiving. Generally, stimulation seeking is not implied in the concept of homo economicus as a cool-minded calculator (Mell & Walker, 2014 ). With regard to implied risk taking, an interesting aspect can be discussed. First of all, homo economicus is generally not inclined to make personally overly and unnecessarily risky decisions. However, homo economicus could very well accept substantial risks if they are ultimately borne by others, as was evident in the example of the massive risk taking that led to the financial crisis (Boddy, 2011 ). Such risk taking is however more rooted in the callous affect of Factor 1 , i.e., based on a lack of emotions and not accepting responsibility if others are harmed. Concerning the items that refer to a lack of realistic long-term planning, i.e., living into the day and letting oneself carelessly and in a potentially self-harming, irresponsible way drift from one impulse to another, is clearly not embodied in the homo economicus model. Rather, as discussed, homo economicus is characterized by a mentally cool, emotionally detached, reflective, and goal-oriented conduct. However, a parasitic lifestyle could resonate with homo economicus to some degree insofar as the model very well implies a potentially opportunistic exploitation of others’ value creation. Yet, besides such minor indications, homo economicus does evidently not qualify for truly attesting an erratic lifestyle .

Lastly the subfactor of antisocial behavior shall be discussed, which comprises a substantial impairment in behavioral control (e.g., frequent violent outbursts), often already at an early age, juvenile delinquency, revocation of conditional releases, and criminal versatility. With regard to homo economicus, the concept reflects a ruthless, emotionally detached conduct, which, however, is combined with a very controlled, clear-minded, target-oriented decision-making and execution of plans and no tendency toward uncontrolled violence or physical misconduct. Consequently, homo economicus does not represent problems with behavioral control as for instance struggling with outbursts of violence and openly breaking the law. Yet, homo economicus could of course engage in a variety of criminal activities if such would appear to be personally profitable, however, in a reflective and controlled manner (e.g., Becker, 1968 ). Summarizing the discussion on the latter two subfactors, it became clear that no substantially elevated Factor 2 can be attributed to homo economicus. In comparison, as the previous discussion shows, homo economicus strongly represents psychopathic traits of Factor 1 of psychopathy. Thus, as a final result, the psychological analysis reveals that homo economicus is evidently a subclinical, i.e., corporate psychopath (see Table 1 and Fig. 1 ).

The finding that homo economicus is a corporate psychopath is of particular interest for business ethics research as it provides a link to the increasing amount of publications indicating the extremely destructive potential of such subclinical psychopaths in business, as also several publications in this journal show (e.g., Boddy, 2011 , 2017 ; Boddy et al., 2010b ). Corporate psychopaths are generally associated with an organizational decline with regard to long-term revenue, employee commitment, and innovativeness (Boddy, 2017 ). They are responsible for a deteriorating work climate by bullying and demoralizing colleagues (Boddy & Taplin, 2016 ; Mathieu & Babiak, 2016 ; Sheehy et al., 2021 ; Valentine et al., 2018 ) and creating an atmosphere of fear (Boulter & Boddy, 2021 ). This, in turn, often leads to increasing sickness rates and sometimes even long-lasting and severe traumatization (Boddy & Taplin, 2016 ). Although corporate psychopaths present themselves in an eloquent manner, behind their shiny façade they are often less qualified than they appear, which they compensate by their eloquent communicative skills and self-confident demeanor (Babiak et al., 2010 ; Perri, 2013 ). There are also several incidents known of forgery of false diplomas and other credentials (Boddy & Taplin, 2016 ). Corporate psychopaths are also known to exert a negative impact on corporate sustainability decisions (Boddy et al., 2010b ; Myung, et al., 2017 ). In addition, such individuals are generally considered unethical decision-makers (Stevens et al., 2012 ; Van Scotter & De Déa Roglio, 2020 ) and are prone to accept even crimes to achieve their goals (Lingnau et al., 2017 ; Ray & Jones, 2011 ). Being impaired in their feelings of fear or remorse, they also have been associated with taking unreasonable organizational risks (Babiak & Hare, 2019 ; Boddy et al., 2010b ) and are more likely to accept direct harm on others (Koenigs et al., 2012 ). Therefore, in the long run, such psychopaths are considered a substantial organizational risk factor and are associated with a diminished business performance and even several corporate breakdowns (Boddy, 2011 , 2017 ; Sheehy et al., 2021 ). Given these implications, the topic of corporate psychopathy is increasingly interesting from the perspective of prevention (Lingnau et al., 2017 ), which involves a variety of interdisciplinary research, including neuroscience, psychology, and law (Sheehy et al., 2021 ).

The finding that homo economicus is not just morally questionable but resembles a specific form of psychopathy to be found in business is therefore not only conceptually insightful, but it also provides several links to business practice. As shall be argued, the concept of homo economicus is not only a matter of textbook theorems but, if closely considered, the discussed personality aspects reverberate (often unspoken) in institutional settings of businesses, being able to at least partially explain why specific individuals are particularly successful and promoted in these settings. In such vein, to advance in their careers, it is often expected that leaders are tough and decisive, being able to make difficult decisions. Such traits are also particularly reflected in traditional chains of command with their individualized, hierarchical working contexts, which put less emphasis on traits of compassion and emotional closeness. This corresponds with the traditional assumption of an economically rational leadership as discussed by Nicholson and Kurucz ( 2019 ). In addition, many working places are undergoing constant changes, facing turbulent environments. Thus, it may be expected of leaders to stay calm and focused. As such, it has been noted that some of the core characteristics of corporate psychopaths, especially those of the affective dimension like cool-mindedness and extreme confidence are often misinterpreted as desirable leadership qualities (Babiak & Hare, 2019 ; Dutton, 2013 ; Hill & Scott, 2019 ). Thus, subclinical psychopaths are often very successful in the hiring process, given their seemingly decisive and strong appearance (Boddy et al., 2021 ). Furthermore, frequent job changes are common in leadership positions and also to some degree expected. This also provides an excellent setting for corporate psychopaths to employ their manipulative traits as these are often very difficult to detect in the short run (Boddy et al., 2021 ).

In addition, it could be argued that the modern capitalistic corporation itself is resembling homo economicus. As such, Bakan ( 2004 ) argues that the corporation has psychopathic attributes (also see Ketola, 2006 ). Through the lens of institutional-organizational fit theories that focus on a self-selection of specific individuals into an organization (e.g., Lazear & Rosen, 1981 ; Ouchi, 1979 ), it could be explained why corporate psychopaths are especially attracted to business environments. More specifically, many businesses apply material incentives and bonus schemes. Traditionally, these are based on the assumptions of unbounded opportunism (Williamson, 1985 ), and in specific, the behavioral assumption of the average individual as a potential work averse shirker (Mankiw, 2018 ), i.e., a manifestation of homo economicus or a corporate psychopath. In such vein, it could be stated with Milgrom and Roberts ( 1992 , p. 42) that these systems are “designed as if people were entirely motivated by narrow, selfish concerns and […] will be fundamentally amoral, ignoring rules, breaking agreements, and employing guile, manipulation, and deception if they see personal gain in doing so.” Even in light of other motives on the side of companies to establish such bonus schemes, individualized material incentives resonate strongly with the selfish and opportunistic traits of corporate psychopaths, given the emphasis on a realization of personal benefit. Thus, they attract corporate psychopaths or the “real homo economicus” (Hoffman, 2011 , p. 491). As these considerations show, even if not always made explicit, the model of homo economicus is often reflected in the institutional settings or the “rules of the game” in business.

Implications for Research and Teaching

From these considerations, several implications for research and teaching can be deduced. As a first motivation, given the vast destruction and organizational hazard corporate psychopaths unfold (e.g., Boddy, 2011 , 2017 ), a better understanding of the aforementioned impact of homo economicus would be relevant for the long-term success and organizational resilience of an organization. Besides such, the following considerations can also be motivated from an ethical perspective that is focused on fostering more humane and responsible business practices. To this end, the following discussion will draw on virtue ethics and an ethics of care as two major streams of business ethics (Dawson, 2015 ; Nicholson & Kurucz, 2019 ). For virtue ethics, the paper refers to the ethics framework by Slote ( 1992 ), who classifies virtuous conduct as comprised of essentially three related major conditions (Dawson, 2015 ). First, there is the requirement that virtues are not selfish, i.e., they do not exclude others. Second, there is the requirement of an agent/other-balance, i.e., individuals must consider what is good for themselves and good for the other(s), which has to be balanced off. Third, virtuous conduct strives for satisfaction and not maximization. As a corporate psychopath, homo economicus evidently fails on all three criteria. First, homo economicus only cares about the personal benefit and the model’s preferences are thus selfish. There are no genuine trade-offs with regard to the legitimate needs of others and thus these others are, if at all, only considered instrumentally. Last, as already Simon ( 1983 ) criticized, homo economicus does not satisfice but maximize. As such, homo economicus is the opposite of a virtuous being. From a second perspective, the model of homo economicus can also be reflected through the lens of an ethics of care, which is provided by Nicholson and Kurucz ( 2019 ). In such vein, an ethics of care can be reflected by four facets: a primacy of relationships, complexity in context, a mutual well-being focus, and engaging as a whole person, which includes affective, intuitive, and imaginative aspects. Equally, homo economicus applies an uncaring logic, referred to as the traditional economic rationality paradigm by Nicholson and Kurucz ( 2019 ). As such, homo economicus is not interested in maintaining emotionally based relationships. Second, complexity is not addressed by encouragement and moral development but rather by enforcing control as reflected in principal-agent theory (e.g., Picot et al., 2008 ). Third, genuine mutual well-being is outside the domain of homo economicus. Finally, an empathic, affective engagement with others is irrelevant to homo economicus as there is only economically rational reasoning instead of a comprehensive, caring approach. In conclusion, the psychopathic model implies the opposite of a caring actor. As such, it can be argued that the resemblance of homo economicus in several institutional aspects of many todays’ businesses factually also hampers the realization of more virtuous and caring ethical conduct.

With such in mind, several suggestions shall be made for future research. First of all, hiring practices such as assessment centers should be questioned, as they are barely able to detect corporate psychopaths (Boddy et al., 2021 ). With regard to virtues, it could be stated that a certain degree of charm, self-confidence, persuasion, visionary thinking, and the ability to sometimes make tough decisions can be desirable from a functional perspective to perform well as a business leader (Dutton, 2013 ). As such, great leaders show some mild degrees of these traits. However, psychopaths are extreme individuals (Boddy et al., 2015 ), and no virtuous, balanced individuals that genuinely care for others. Current research is only beginning to deeper investigate into these issues, and specifically with regard to psychopathy, is still largely focused on groundwork conceptual considerations (e.g., Dutton, 2013 ). Thus, more empirical research is required to find out where such optimum might be situated, or conversely, when the aforementioned traits become dysfunctional.

In addition, it would be generally highly valuable to try to systematically disentangle specific properties of business environments that attract psychopaths, for which this paper could be a starting point. As such, it is important to note that the insight that homo economicus is a corporate psychopath and thus critically to be evaluated from an ethical and psychological perspective, does not render the model worthless. On the contrary, as homo economicus is a corporate psychopath, the model may be of use to identify structures in business that resemble homo economicus and thus currently attract and promote individuals who possess these traits. Based on these considerations, organizational properties could be explored that prevent the ascent of corporate psychopaths. In such way, it might be very interesting to design incentive structures that motivate talented individuals but are less likely to attract psychopathic individuals, for instance, by placing more emphasis on rewarding true social skills (Lingnau et al., 2017 ; Marshall et al., 2015 ; Schütte et al., 2018 ) such as compassionate morality (Woodmass & O’Connor, 2018 ). These insights could then be linked to system approaches, i.e., the integration and coordination of several approaches that combine and reinforce these effects (Bedford et al., 2016 ; Grabner & Moers, 2013 ; Speklé et al., 2022 ).

Moreover, in general, it seems even more important to think critically about the deeper implications of the values associated with theoretical models used in business that are built on the assumption of economic rationality and thus the maximization of personal benefit. As discussed, even if not explicitly named, the behavioral assumptions of homo economicus are represented in many economic models with regard to “rational” maximization or optimization. Such a critical reflection is especially relevant when these models are applied in real-world contexts such as policy making. For example, neoliberal deregulation and the promotion of shareholder value maximization are based on theoretical assumptions that not only do not hold up in the real world, but often conflict with a societally responsible conduct. Yet, still, political programs and business targets are based on such concepts because it is often not sufficiently considered that the underlying models are only applicable in an abstract, idealized context. This in turn leads to the obviously questionable long-term results in terms of wealth inequality and the erosion of social cohesion, undermining the very foundations of a democratic, free society (e.g., Horváth & Barton, 2016 ).

In addition to research, academia also has an influence on real-world decision-making via teaching, especially when former students become advisors, decision-makers in firms or policy-makers. Given that the research community has an exemplary function due to prestige and scientific expertise, this leads to think more about the role and responsibility of academic teaching. As stated above, already the choice of model contains some normative basic statements, which are (at least implicitly) conveyed when presented in the classroom. As the classic paper by Frank et al. ( 1993 ) as well as some newer research (e.g., Ifcher & Zarghamee, 2018 ; Kowaleski et al., 2020 ; Racko, 2019 ) demonstrates, teaching can influence students’ attitudes, also and in particular with regard to normative aspects. If one considers academic teaching not solely as a means of conveying abstract insights but also as an opportunity to enable future decision-makers to develop their full potentials and capabilities, teaching evidently also has some responsibility. This responsibility toward those being educated would therefore be linked to fostering the development of virtuous and caring personalities such that future decision-makers are able and endeavor to be responsible leaders (Ulrich, 2008 ). In this light, it can be concluded that a more critical reflection on normative assumptions is also of fundamental importance for teaching. This could include not only a reflection on the psychopathic traits of homo economicus as discussed in this paper, but even more the drawing of a complementary picture with references to other concepts such as homo faber, homo ludens, homo politicus, or homo moralis. These conceptual insights could be enriched with findings from empirical research on human decision-making to broaden the understanding of the real behavioral dispositions of the vast majority of nonpsychopathic individuals or—in Sen’s ( 1977 ) notion—to account for homo sapiens as a complex individual that does and should not solely act out of ruthless opportunism but possesses genuine social traits that deserve to be fostered.

As this paper systematically discussed, the concept of homo economicus can be considered a prototype of a psychopath. In contrast to many anecdotal references, this paper took an in-depth analysis delivering a finer picture with regard to the psychological notion of psychopathy. In particular, it could be shown that homo economicus is not simply some kind of psychopath but specifically a subclinical or Factor 1 psychopath, often referred to in business research as a “corporate psychopath.” These are individuals who are extremely callous, selfish, and manipulative, but may appear normal at first glance because they have no significant impairment in their long-term planning and behavioral control, which makes them particularly dangerous in business environments (e.g., Boddy, 2011 , 2017 ).