Module 11: Conflict and Negotiation

Stages of negotiation, learning outcomes.

- Describe the stages in the process of negotiation

Negotiation, in simplified terms, is a five-step process. Those steps are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The five steps of negotiation

Let’s take deeper look into each step.

Preparation and Planning

In the preparation and planning stage, you (as a party in the negotiation) need to determine and clarify your own goals in the negotiation. This is a time when you take a moment to define and truly understand the terms and conditions of the exchange and the nature of the conflict. What do you want to walk away with?

You should also take this moment to anticipate the same for the other party. What are their goals in this negotiation? What will they ask for? Do they have any hidden agendas that may come as a surprise to you? What might they settle for, and how does that differ from the outcome you’re hoping for?

This is a time to develop a strategy for the negotiation. We’ll talk more about strategies in the next section.

Definition of Ground Rules

After the planning and strategy development stage is complete, it’s time to work with the other party to define the ground rules and procedures for the negotiation. This is the time when you and the other party will come to agreement on questions like

- Who will do the negotiating—will we do it personally or invite a third party?

- Where will the negotiation take place?

- Will there be time constraints placed on this negotiation process?

- Will there be any limits to the negotiation?

- If an agreement can’t be reached, will there be any specific process to handle that?

Usually it’s during this phase that the parties exchange their initial positions.

Clarification and Justification

Once initial positions have been exchanged, the clarification and justification stage can begin. Both you and the other party will explain, clarify, bolster and justify your original position or demands. For you, this is an opportunity to educate the other side on your position, and gain further understanding about the other party and how they feel about their side. You might each take the opportunity to explain how you arrived at your current position, and include any supporting documentation. Each party might take this opportunity to review the strategy they planned for the negotiation to determine if it’s still an appropriate approach.

This doesn’t need to be—and should not be—confrontational, though in some negotiations that’s hard to avoid. But if tempers are high moving into this portion of the negotiation process, then those emotions will start to come to a head here. It’s important for you to manage those emotions so serious bargaining can begin.

Bargaining and Problem Solving

This is the essence of the negotiation process, where the give and take begins.

You and the other party will use various negotiation strategies to achieve the goals established during the preparation and planning process. You will use all the information you gathered during the preparation and planning process to present your argument and strengthen your position, or even change your position if the other party’s argument is sound and makes sense.

The communication skills of active listening and feedback serve the parties of a negotiation well. It’s also important to stick to the issues and allow for an objective discussion to occur. Emotions should be kept under control. Eventually, both parties should come to an agreement.

Closure and Implementation

Once an agreement has been met, this is the stage in which procedures need to be developed to implement and monitor the terms of the agreement. They put all of the information into a format that’s acceptable to both parties, and they formalize it.

Formalizing the agreement can mean everything from a handshake to a written contract.

Practice question

Let’s take a look at this process in action. A team from a retail organization, Salesco, is looking to purchase widgets for resale directly to the consumer. You lead a team from WholesaleCo and are interested in negotiating an offer to sell these widgets to them at a wholesale cost.

- Preparation and Planning. You know that WholesaleCo will be going up against OtherCompany, who is likely to outbid you on price. You research, as best you can, the price and quantity OtherCompany is willing to come to the table with. You also know, from your earlier research, that Salesco is a company that values quality and if they’re going to say no to OtherCompany, it’ll be because they have a reputation for skimping on quality. Your company produces the better, but more expensive, widget. Armed with this information, you put together your proposal.

- Definition of Ground Rules. Salesco, as your customer, has let you know that they expect widgets to be manufactured and delivered in the first quarter of the following year. They’d like to sign with a 25% deposit. Your company usually requires 50% down, but you counter with 30%, provided you have a signed contract before the end of the year, which is approaching quickly. You offer Salesco your proposal. Salesco does not share OtherCompany’s offer.

- Clarification and Justification. Salesco wants to understand more about your deposit requirements, and you’d like to know if your offer is otherwise in the ballpark for them. You reiterate that you provided them the best price you could for the quality product you produce. Salesco assures you your offer is good but they’ll review it further with their legal team.

- Bargaining and Problem Solving. Salesco understands that WholesaleCo is not providing them the best price but that the quality they look to provide their customers will only come from WholesaleCo, and never OtherCompany. They’d still like to go with a 25% deposit because that’s all they have budgeted for the remainder of the fiscal year. As a representative of Wholesale, you offer to go with a 25% deposit if a second payment can be made at the beginning of the next quarter, which would allow them to pay it out of next year’s budget. Agreements are made.

- Closure and Implementation. WholesaleCo makes changes to the contract for the widgets and a representative from Salesco signs. The new contract outlines the changes in the deposit structure, and a full delivery schedule of widgets to Salesco’ distribution centers by an agreed-upon date.

The negotiation process is complete.

Books have been written, and classes have been taught on the art of negotiation. The ability to master negotiation strategy is a coveted skill in the business world. Now that we understand the basics of the negotiation process, let’s take a look at some of the negotiation “experts” that are out there and how they finesse the process to get the best results.

Contribute!

Improve this page Learn More

- Stages of Negotiation. Authored by : Freedom Learning Group. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image: Five Steps of Negotiation. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

11.2: Stages of Negotiation

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 48729

Learning Objectives

- Describe the stages in the process of negotiation

Negotiation, in simplified terms, is a five-step process. Those steps are shown in Figure 1.

Let’s take deeper look into each step.

Preparation and Planning

In the preparation and planning stage, you (as a party in the negotiation) need to determine and clarify your own goals in the negotiation. This is a time when you take a moment to define and truly understand the terms and conditions of the exchange and the nature of the conflict. What do you want to walk away with?

You should also take this moment to anticipate the same for the other party. What are their goals in this negotiation? What will they ask for? Do they have any hidden agendas that may come as a surprise to you? What might they settle for, and how does that differ from the outcome you’re hoping for?

This is a time to develop a strategy for the negotiation. We’ll talk more about strategies in the next section.

Definition of Ground Rules

After the planning and strategy development stage is complete, it’s time to work with the other party to define the ground rules and procedures for the negotiation. This is the time when you and the other party will come to agreement on questions like

- Who will do the negotiating—will we do it personally or invite a third party?

- Where will the negotiation take place?

- Will there be time constraints placed on this negotiation process?

- Will there be any limits to the negotiation?

- If an agreement can’t be reached, will there be any specific process to handle that?

Usually it’s during this phase that the parties exchange their initial positions.

Clarification and Justification

Once initial positions have been exchanged, the clarification and justification stage can begin. Both you and the other party will explain, clarify, bolster and justify your original position or demands. For you, this is an opportunity to educate the other side on your position, and gain further understanding about the other party and how they feel about their side. You might each take the opportunity to explain how you arrived at your current position, and include any supporting documentation. Each party might take this opportunity to review the strategy they planned for the negotiation to determine if it’s still an appropriate approach.

This doesn’t need to be—and should not be—confrontational, though in some negotiations that’s hard to avoid. But if tempers are high moving into this portion of the negotiation process, then those emotions will start to come to a head here. It’s important for you to manage those emotions so serious bargaining can begin.

Bargaining and Problem Solving

This is the essence of the negotiation process, where the give and take begins.

You and the other party will use various negotiation strategies to achieve the goals established during the preparation and planning process. You will use all the information you gathered during the preparation and planning process to present your argument and strengthen your position, or even change your position if the other party’s argument is sound and makes sense.

The communication skills of active listening and feedback serve the parties of a negotiation well. It’s also important to stick to the issues and allow for an objective discussion to occur. Emotions should be kept under control. Eventually, both parties should come to an agreement.

Closure and Implementation

Once an agreement has been met, this is the stage in which procedures need to be developed to implement and monitor the terms of the agreement. They put all of the information into a format that’s acceptable to both parties, and they formalize it.

Formalizing the agreement can mean everything from a handshake to a written contract.

Practice question

https://assessments.lumenlearning.co...essments/13706

Let’s take a look at this process in action. A team from a retail organization, Salesco, is looking to purchase widgets for resale directly to the consumer. You lead a team from WholesaleCo and are interested in negotiating an offer to sell these widgets to them at a wholesale cost.

- Preparation and Planning. You know that WholesaleCo will be going up against OtherCompany, who is likely to outbid you on price. You research, as best you can, the price and quantity OtherCompany is willing to come to the table with. You also know, from your earlier research, that Salesco is a company that values quality and if they’re going to say no to OtherCompany, it’ll be because they have a reputation for skimping on quality. Your company produces the better, but more expensive, widget. Armed with this information, you put together your proposal.

- Definition of Ground Rules. Salesco, as your customer, has let you know that they expect widgets to be manufactured and delivered in the first quarter of the following year. They’d like to sign with a 25% deposit. Your company usually requires 50% down, but you counter with 30%, provided you have a signed contract before the end of the year, which is approaching quickly. You offer Salesco your proposal. Salesco does not share OtherCompany’s offer.

- Clarification and Justification. Salesco wants to understand more about your deposit requirements, and you’d like to know if your offer is otherwise in the ballpark for them. You reiterate that you provided them the best price you could for the quality product you produce. Salesco assures you your offer is good but they’ll review it further with their legal team.

- Bargaining and Problem Solving. Salesco understands that WholesaleCo is not providing them the best price but that the quality they look to provide their customers will only come from WholesaleCo, and never OtherCompany. They’d still like to go with a 25% deposit because that’s all they have budgeted for the remainder of the fiscal year. As a representative of Wholesale, you offer to go with a 25% deposit if a second payment can be made at the beginning of the next quarter, which would allow them to pay it out of next year’s budget. Agreements are made.

- Closure and Implementation. WholesaleCo makes changes to the contract for the widgets and a representative from Salesco signs. The new contract outlines the changes in the deposit structure, and a full delivery schedule of widgets to Salesco’ distribution centers by an agreed-upon date.

The negotiation process is complete.

Books have been written, and classes have been taught on the art of negotiation. The ability to master negotiation strategy is a coveted skill in the business world. Now that we understand the basics of the negotiation process, let’s take a look at some of the negotiation “experts” that are out there and how they finesse the process to get the best results.

Contributors and Attributions

- Stages of Negotiation. Authored by : Freedom Learning Group. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image: Five Steps of Negotiation. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

The Stages of the Negotiation Process

We negotiate all the time, without even realizing it. In fact, human beings begin negotiating when we are small children, negotiating with our parents when we want something we know we shouldn’t have, or with a friend or sibling that has a toy we covet. As we grow, of course, these negotiations become more complicated. Negotiations occur with friends, family, schoolmates, and, later in life, our coworkers and superiors. While these situations vary greatly across the scope of a lifetime, the skills needed for successful negotiation remain the same.

At its most basic, negotiation is a process undertaken by at least two separate individuals or groups who desire different outcomes regarding a specific event or situation. Though they want something different, negotiation occurs when all involved are willing to discuss the situation to come to a mutually agreeable solution. Thus, understanding how to negotiate is a critical skill to build, benefitting both your personal and business life.

However, like any new skill, learning how to negotiate well can take time. To begin the process, it is beneficial to understand the five main stages of the negotiation process.

The Five Stages of Negotiation

When starting any new project, including negotiation efforts, it is important to lay the foundation first. The preparation stage is composed of a variety of steps that are all geared toward helping you set the groundwork for your negotiation. In this stage, of course, preparation is key. Conflict can arise at any time, which means there is no allotted timeframe for you to prepare your negotiation techniques. Therefore, it is critical to start this first stage as soon as possible.

The prepare, probe and propose stage involves researching pertinent information as well as analyzing all the data you collect to determine its utility. It is important to understand the issue at hand as well as all the potential angles involved. A skilled negotiator understands that the ultimate goal of negotiation isn’t necessarily to prove you are right; rather, it is about being informed and accurate. Research during the initial stage is important to understand what will occur when negotiating the conflict at hand.

Who is involved? Where did the conflict start? Why is this an issue for either party? These questions, along with several others, are important to consider during this stage. By probing the issue, you are digging deep to understand the roots of the issue. Once you understand the issue fully, you can start to propose solutions to resolve the conflict at hand. If all goes well, you’ll be able to propose a solution that both parties can find beneficial.

In stage one, you haven’t even officially met with the other side yet. You’ve done your research to build your case and have learned all you can about your opposition. In stage two, you will begin to communicate with your opposition, but there is still work to be done before any official negotiating can begin. In stage 2, your primary focus is to establish the terms of the negotiation as well as exchange information to improve the chances of a successful negotiation.

At this stage, you’ll also focus on exploring the other side. This provides you an opportunity to test the assumptions you developed during your initial research. This is also the best opportunity to try and build a positive relationship heading into the negotiation. Even if you are coming to the negotiating table with vastly different views, a sense of common ground and understanding is beneficial. With effort, you can develop a better understanding of what the other side wants to accomplish and what potential solutions may mesh well with your own goals.

Building rapport and trust while discussing the ground rules of the negotiation can lead to a new level of comfortability. When you and your opposition are comfortable, you are generally more willing to communicate openly and express yourself freely. Thus, the goals of this stage are to gain some level of trust, build a common ground of honesty and credibility, and find some way to establish and build upon the relationship.

It is important not to rush this stage if possible. There is no set time frame for completing each of the steps of negotiation. The more time you can invest in building a relationship and finding common ground, the better chance you have at making your position heard and understood during negotiation.

Before diving into the true negotiations, it is important to be sure that both parties are on the same page regarding the negotiation process. In stage two, you took the time to understand the other side. You listened to their issue as well as what they hope to gain from the negotiating process. You also explained your stance, and what you hope to gain. Together, you should have established some ground rules to ensure that all relevant viewpoints and time are respected.

In stage three, you’re essentially finalizing this process. Take the time to reflect on what you’ve learned and note any gaps or confusions that may be present. Stage three allows you the opportunity to seek any necessary clarifications from your opposition involving the issue itself, other parties with stake in the negotiations, the evidence provided, or even what may constitute a mutually agreeable outcome.

Stage four is where true negotiation begins. You’ve taken the time to do your research and fully understand the issue at hand. You’ve met with the other side to understand their concerns and hopeful outcomes. You’ve also taken the time to seek any necessary clarifications. Now, it is time to advocate for your proposed solution and listen to the opposition’s counterproposal.

In the bargaining stage, it is important to be aware of not only the verbal cues of your negotiation partner, but the non-verbal cues as well, including body language. This process can be delicate, and in difficult negotiations, you must sometimes move back a step to problem solve until all parties are comfortable. During the bargaining stage, each side will lay out their concerns as well as their perceived solutions. This process is all about the give and take, so it is beneficial to remember that the ultimate goal is to seek a mutual agreement.

Bargaining can take time, but eventually the negotiations must come to an end. A solution must be reached, and it will ideally benefit both parties in some way. At this stage, it is important to make sure that all essential elements to officially establish the agreement are in place. Thus, clarity is key to ensuring that everyone is on the same page before implementation begins. This stage can involve signing contracts or legally enforcing any other terms laid out during the negotiation process. Follow-up is crucial, ensuring that implementation brings with it the desired effects for both parties.

Common Questions

Several questions can arise for those learning about the negotiation process. We’ve taken the time to answer some of the most common:

- How long does the negotiation process take?

As with any conflict, it is difficult to put a definitive timeline on the negotiation process. For example, when it comes to the research stage, the length of time required can vary depending on the situation. If you are just trying to convince your partner to take a vacation, for instance, you already know them and can anticipate their counterarguments. Conversely, if you are negotiating with someone whom you don’t have a strong relationship with, the research should be much more intensive.

The length of the negotiation process can depend on the qualities of the people involved as well as the scenario. If you have two parties that are willing to compromise, the process can elapse rather quickly. On the other hand, if you are dealing with strong opposition from a staunch rival, it may take a considerable time investment before you achieve results.

Preparation may not guarantee negotiation success, but it certainly doesn’t hurt your chances. Odds are, you haven’t come out victorious in every conflict in life, and it is important to remember that there are no guarantees. No matter how prepared you are, there is always a chance that a mutually beneficial solution is not possible. What is important is seeing these moments as an opportunity to grow and build a future relationship with the opposition instead of simply seeing them as a loss.

To keep it simple, yes—it is important to follow these steps to ensure you are fully prepared for an upcoming negotiation. If you try to jump right into formal negotiations without fully understanding the situation, the opposing viewpoint, and the opposition’s goals, failure is much more likely. Worse, the other side may notice your inability to prepare, which can only have negative consequences. If you don’t take the time to gain trust and build a relationship, you may face greater opposition and will be less likely to reach a mutually beneficial solution.

The wonderful thing about negotiation skills is that they can be used for any situation causing conflict, whether in your personal life or at work. The main takeaway you should get from these steps is the importance of developing the ability to successfully communicate your side of an issue while remaining open enough to genuinely listen to the other side. From there, you and your negotiation partner can talk through your thoughts, feelings, and expectations with the hopes of finding a common ground. As you move through the process, the ultimate goal is finding agreeable terms that both parties can appreciate. This outlook can be beneficial for small disagreements and larger conflicts alike.

Trust the Negotiation Process

Negotiation is an art form. Thus, it can certainly take time to master, even though most of us have been taking part in negotiation for most of our lives. However, once you understand the fundamentals, negotiation becomes more and more natural each time.

In fact, learning about the negotiation process is beneficial for everyone. We all face conflict on some level and knowing how to handle that conflict can make a world of difference when it comes to achieving a beneficial resolution. The five stages of negotiation are meant to help new negotiators and master negotiators alike hone their craft to ensure the best chances at success. Each step is important, and although there is no established timeframe in which you must master these tools, you will not improve without time and practice.

The best way to practice these skills is through professional training. To help, Shapiro Negotiations Institute offersnegotiation training to business professionals, executives, and anyone who has a willingness to learn. Contact SNI today to learn more.

3600 Clipper Mill Rd, Suite 228 Baltimore, MD 21211 410-662-4764 [email protected]

Stay Connected

Negotiation Process [5 Steps/Stages of Negotiation]

![Negotiation Process [5 Steps/Stages Of Negotiation] Negotiation Process [5 Steps/Stages Of Negotiation]](https://i0.wp.com/www.iedunote.com/img/1512/negotiation.jpg?fit=1080%2C607&quality=100&ssl=1)

The negotiation process permeates the interactions of almost everyone in groups and organizations. In today’s loosely structured organizations, in which members work with colleagues over whom they have no direct authority and with whom they may not even share a common boss, negotiation skills become critical.

The negotiation process consists of certain phases. The following figure depicts a model describing the basic features of the negotiation process. They are—the preparation phase (information gathering); developing and selecting a strategy (setting the ground rules), opening moves (exploring and proposing the matter), bargaining and problem-solving, and closure and implementation of the negotiation process.

The essence of the five steps of the negotiation process is the actual give and take in trying to hash out an agreement, a proper bargain suitable for all parties.

In this post, we will look at the negotiation process, which is made up of five steps. These steps are described below;

5 Steps of the Negotiation Process

Preparation and planning.

Before the start of negotiations, one must be aware of the conflict, the history leading to the negotiation of the people involved and their perception of the conflict , expectations from the negotiations, etc.

Before starting the negotiation, it needs to do homework .

- What’s the nature of the conflict?

- What’s the history leading up to this negotiation?

- Who’s involved, and what are their perceptions of the conflict?

Moreover, before any negotiation takes place, a decision needs to be taken as to when and where a meeting will take place to discuss the problem and who will attend.

Setting a limited time scale can also be helpful to prevent disagreement from continuing. This stage involves ensuring all the pertinent facts of the situation are known in order to clarify one’s own position.

It also needs to prepare an assessment of what the other parties’ negotiation goals are. What are they likely to ask for?

Skilled negotiators invest more time and effort in planning the process they intend to use. It serves as a guideline for them. In this phase, a detailed analysis is required on certain issues.

It can be the nature of conflict, history of conflict, parties involved in it, own assessment as well as others’ goals, and so on.

The important questions to resolve are:

- How entrenched are they likely to be in their position?

- What intangible or hidden interests are important to them?

- What are they likely to ask for?

Developing One’s BATNA

Negotiators need to know their Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA). It is made up of a variety of elements.

These can include deadlines; alternatives such as other suppliers or customers; your own resources; their resources; information you gain before and during the negotiation; the level of experience you or other parties have; your as well as the other party’s interests; and knowledge about the matters under consideration.

Each party has a BATNA. It guides in responding to the situation.

Determining one’s Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA) is important because it tells us whether a particular negotiation is worth undertaking or continuing in the light of the alternative way that might serve your interests.

Fisher and Ury outline a simple process for determining one’s BATNA.

- Develop a list of actions that one might conceivably take if no agreement is reached.

- Improve some of the more promising ideas and convert them into practical options.

- Select tentatively the one option that seems the best.

The goal of negotiating is to arrive at a good agreement. It is a measure of the balance of power among the negotiating parties based on the resources they control or can influence to respond to their interests that will be addressed in a given negotiation.

BATNAs are critical to negotiation because one cannot make a wise decision about whether to accept a negotiated agreement unless one knows what the alternatives are.

The better you understand your BATNA and the BATNA of other parties, the better you are able to judge whether to continue the negotiation or to walk away before an unappealing agreement is reached. Assessment of the other parties’ BATNAs helps to influence them and make them change it.

Choice of style—win-win or win-lose

There are two fundamental choices—a cooperative style (A win-win style ensures that both parties gain some benefit) and a competitive style (It is designed to maximize only one side’s advantage at a specific cost to the other.

This is an aggressive stance and, therefore, a win-lose approach to negotiation). It is important to decide whether it is more appropriate to aim for a win-lose competitive outcome or a cooperative win-win approach. It is decided depending on the nature of the conflict.

Team selection

Who do you need to include in your team , and what will their respective roles be?

Team selection should be based on certain criteria like;

- personal qualities; functional skills that are required (for example, product or services),

- specialist areas (like technical issues such as performance, quality assurance, warranties maintenance, commercial issues like price, delivery payment terms, legal issues, etc.);

- Team playing skills (like compatibility with team members, balance of functional and personal skills—need to be complementary across the team, credibility, personal regard by the other sides);

- Negotiating roles (like leading, note-taking, listening , reviewing, surveillance).

Developing an interesting map

The best way is to test your assumptions about the stakeholders’ interests. Then, connect the interests of one stakeholder with the other.

A part of the job of developing an interest map is to figure out how the interests of each stakeholder relate to one another.

An interest map offers you a mechanism for determining what information you need, what questions to ask, what assumptions to question, and what elements will be most helpful to you and other parties in reaching mutually satisfactory results through a good negotiation process.

By underscoring your focus on interests, your interest map will help you avoid getting stuck on emotional hot buttons or cultural obstacles to developing a workable negotiation process and an agreement that works for the parties.

Skilled negotiators often use a planning form to facilitate negotiation planning. This planning process offers some significant advantages shown below:

- Putting down your thoughts on paper helps to sort them out and avoid contradictions.

- During team negotiations, it is useful to have a document for all members to contribute, criticize, etc. This helps prevent members from going off-track during the negotiation.

- In the post-negotiation review and in between negotiations, it is helpful to review the tasks already done and those that are yet to be done.

Developing and Choosing a Strategy [Definition of Ground Rules]

Once the planning and strategy are developed, one has to begin defining the ground rules and procedures with the other party over the negotiation itself that will do the negotiation.

- Where will it take place?

- What time constraints, if any, will apply?

- To what issues will negotiations be limited?

- Will there be a specific procedure to follow if an impasse is reached?

During this phase, the parties will also exchange their initial proposals or demands.

Sound planning and careful preparation of ground rules are vital for a successful negotiation. We need to ask certain questions to set ground rules. Such questions should include the following aspects.

Why, Who, What, When, and How of Negotiation

- Who will we be negotiating with?

- What are our objectives?

- Why are we interested in negotiations?

- How are they to be valued, and in what order of importance are they to be ranked?

- To what issues will negotiation be limited?

- When will it suit us best to hold the negotiations?

- And when would it not?

- How should we pitch our initial demands?

- To what degree should we be prepared to modify these demands each time we are faced with counter-offers?

- How should we negotiate?

- How much time will we need to reserve?

- What assumptions should we make in our planning?

- How can we check their validity?

- Where do we want to meet—on our ground, on theirs, or on neutral territory?

- Where do we want the negotiations to take place?

Concessions

You have to decide what variables in your position you are prepared to exchange in return for any counter-offers.

What order should you set for offering your concessions, and what else might you be prepared to include?

Concessions are important because they;

- enable the parties to move towards the area of potential agreement,

- symbolize each party’s motivation to bargain in good faith, and

- tell the other party the relative importance of the negotiating issues.

It is the difference between two parties’ bids and usually indicates where the settlement will finish. The higher one pitches one’s first bid, the more favorably positioned the midpoint will be for his side. The positioning of each subsequent bid can move the midpoint.

Each time it is your turn to bid, it will be you who will determine the new midpoint. One can move the midpoint in one’s favor by moving in smaller steps than the other side or even by not moving at all.

Technique of how to open the negotiation should also be planned. It requires a rehearsal of what you are going to say in your opening statements and how you are going to say it, as well as the analysis of the probable and possible opening comments that might be expected from the other side.

Another useful area that needs to be thought about is the seating arrangement.

Seating people full square opposite each other is generally considered to enhance the risk of confrontation. In one-to-one negotiations, it is better to opt for a cooperative arrangement, that is, to sit side by side.

The most flexible seating plan is to sit around the corner’ from the other party. This is friendly, relaxed, and non-invasive. It is, therefore, good for encouraging a cooperative atmosphere. If the climate turns aggressive, you can distance yourself without prejudicing your position.

Establishing the Issues and Constructing the Agenda

It gives a good idea of substantive elements a negotiation should cover to respond to our interests and what you assume to be the interests of other negotiating parties and outside stakeholders. Before a negotiation begins, all the aspects need to be answered.

Clarification and Justification

When initial positions have been exchanged, both parties will explain, amplify, clarify, bolster, and justify their original demands. This need not be confrontational.

Rather it is an opportunity for educating and informing each other on the issues, why they are important, and how each arrived at their initial demands.

This is the point where one party might want to provide the other party with any documentation that helps support its position.

It is the time of advancing demands and uncovering interests. After establishing the agenda, the opening moves in negotiation usually consist of each side putting forth its positions and demands. They need to explain, amplify, clarify, bolster, and justify their own original demands.

Building Confidence

Among negotiating parties, this is often an important first step or a series of steps that need to be undertaken. Confidence-building measures can be more elaborate.

When negotiating parties do not know each other well or if they have an unfriendly history, they can use a variety of tools to increase their comfort level with one another. Asking good questions and listening carefully are confidence-building elements in any negotiation.

Few other strategies can be used to negotiate in phases (trading agreements and performance on a piece-by-piece basis). Each small agreement that is made by both parties needs to be fulfilled.

In that case, the parties can work on larger, more complex, or more divisive issues. Early demonstrations that parties made, when become fulfilled, can increase all parties’ confidence that the overall process will be worthwhile. In each step, one should check one’s own BATNA.

The more you can explore the other side’s position, the stronger you will be. What do you need to explore? It is the who, what, and why of negotiation, their BATNA, style, goal, etc.

The use of one’s interest map can give an outline of questions rather than the skeleton of the perfect solution. The more information you get from them, the more accurate the assessment of how your BATNA is affected will be. It helps in responding to the problem creatively and effectively.

The important categories and sub-categories of oral behavior include seeking as well as giving information.

In seeking information, the behavior usually takes the interrogative form and asks questions such as “What is your annual production and sales of watches?”

Giving information takes two forms. In the external form, the negotiator gives the information as a matter of fact as in “Last quarter, we produced 4 million watch pieces.” The internal form involves opinions or qualifications of presented facts.

It also includes the expression of feelings such as “Your insistence on a just-in-time delivery system makes us feel comfortable.”

Extensive exchange of data may reduce chances of making mistakes. An open behavior acknowledges such a mistake and corrects it, “I’m sorry. The 10 million units I’d mentioned were the figure two years ago.”

Bargaining and Problem Solving

The essence of the negotiation process is the actual give and take in trying to hash out an agreement, a proper bargain . It is here where concessions will undoubtedly need to be made by both parties.

This is the phase of bargaining and discovering new options. This is where lateral thinking skills are invaluable in finding concessions that the other side will consider worthwhile but will cost you little.

This is known as searching for variables and is vital not only in offering concessions but also in evaluating those you receive.

Some of the other behaviors that are observed are agreeing (some proposals of the other party can be readily acceptable while the rest cannot) and disagreeing. In contrast, blocking involves disagreeing without assigning any reason.

An example may be, “Absolutely, under no circumstances will we consider that action.” Disagreeing sometimes escalates from disagreement with the content of a proposal to direct disagreement with the personal tactics or motives of the other party.

An example of such disagreement is a statement like, “You are deliberately trying to mislead us.”

Negotiators refer to this kind of behavior as attacking. Attacking usually brings out defending behavior from the other party

“We are not trying to mislead you, but you are not being clear in what you want.” Thus, defending behavior often turns the attack around.

At this stage, promises, threats, bluffing, and personal attacks are likely to emerge. Effort must be made not to personalize at this stage; participants must be objective and should focus on facts and not on assumptions.

The actual give-and-take process takes place during this stage. Parties reach a settlement and try to improve the outcome.

During the bargaining, the first bid should be as high as possible but still realistic.

There is always a possibility that in negotiation, the price or the demand will always be reduced. If the initial bid is not pitched high, then it will be more difficult to bring it up at a later stage. Low expectations generally produce low results.

The actual process of negotiation is the give-and-take process.

So, concessions have to be made. The initial concessions that you make should be small and tentative. If your initial offer is too large, problems would arise. If there is a deadlock, then certain tactics should be used to overcome them.

Small concessions should be tied to a condition that will give you something in exchange. Always try to couple the concession you offer with another concession of similar magnitude in return so that your case is not weakened.

While receiving and giving concessions, it should not only be given reluctantly, it should also be received reluctantly. Accept concessions slowly with apparent pain.

Alternatively, you might choose to give no reaction at all to an offer. Next is to link all the issues into one package. A net loss on the concession trading regarding one item can then be set off against a benefit somewhere else. If you are offered a package deal, split it up.

If you are offered a range of items, search for a global package. Summarize regularly and feel free to suggest a recess when you need time to plot your course further.

In the course of negotiations, especially lengthy ones, it is easy to lose the focus of the negotiation. A brief, concise summary of what has been discussed to date in the negotiation and what the other party has agreed to in whole or in part needs to be documented.

Closure and Implementation

The final step in the negotiation process is a formalization of the agreement that has been worked out and developing and procedures that are necessary for implementation and monitoring .

For major negotiations – this will require hammering out the specifics in a formal contract.

Negotiation Process has five stages. In all steps of a negotiation process, the involved parties bargain in a systematic way to decide how to allocate scarce resources and maintain each other’s interests.

This step focuses on working out an agreement and developing a procedure for its implementation and monitoring.

Settling the Deal

When an agreement has been reached after a complex negotiation, it is vital to confirm that both parties have actually agreed to the same deal. Misunderstandings can arise at this stage. It needs the help of a lawyer to clarify your doubts, if any.

For a contract to be signed, all contractual considerations should be taken into account. Then, standard terms and conditions need to be written clearly.

Provision should be made where damages are to be applied. If you want, a provision of ‘guarantee’ should be made and not a warranty. Please note that a ‘warranty’ is not legally a condition of a contract.

Improving the Outcome

The best result comes in a negotiation where there is a combination of three important attributes: skill, aspiration, and power. Power influences the other party. It can also be abused. But it should not be used to threaten the weaker party.

High aspirations win higher rewards by making initial demands high. The optimum position, in order to negotiate the best deal, is to have high levels of power, aspiration, and skill.

In the case of resistance to finalizing an agreement because of uncertainty as to how it will work out in practice, apply the re-opener provision.

This provision is an agreement stating that after a given period of time, the decision arrived at by the parties will be subject to re-examination and possible modification. The closure of the negotiation process is nothing more formal than a handshake.

Following our deep dive into 5 steps of the negotiation process; use our total guide on fundamentals of management and organizational behavior .

- 4 Levels of Conflict

- Components of Conflict

- Models of Conflict

- 6 Causes of Conflict

- 27 Types of Conflict

- Intrapersonal Conflict: Types, Sources, Strategies, Examples

- Interpersonal Conflict: Types, Principles, Stages, Model

- Tricks In Negotiation: 20 Tricks Used in Negotiation Process

- Intragroup Conflict: Meaning, Managing, Strategies

- Intergroup Conflict: Meaning, Managing, Causes, Solutions

- Fishbowl Conversation Techniques

- Industrial Conflict: Meaning, Forms, Causes

- Collective Bargaining: Meaning, Objective, Characteristics, Types

- Mediation Process [Complete Learning Guide]

- Skills of Mediator in Conflict Management

- Strategic Planning: Meaning, Steps, Objectives

- Taylorism: Scientific Management Approach of Frederick W. Taylor

- Management is Universal Process and Phenomenon (Explained)

- Budget: Definition, Classification, and Types of Budgets

- Bureaucratic Management Theory by Max Weber

- 6 Qualities of a Great Plan for Achieving Success

- How to Ensure Effectiveness and Efficiency in Productivity

- Business Strategy: Definition, Elements, Types, Process

- 4 Functions of Attitude

- What is Conflict Management?

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- *New* Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

How to Prepare for a Negotiation

- 27 Jun 2023

Preparing for expected and unexpected outcomes is essential to negotiating effectively. Negotiations can be unpredictable and challenging—it's difficult to know how the other party will react to your proposition. Planning can make the difference between success and failure.

If you need to prepare for a difficult negotiation, here are seven steps to achieving the best outcome.

Access your free e-book today.

7 Steps to Preparing for a Negotiation

1. build a relationship.

Building a relationship with your counterpart is vital. If possible, get to know them and establish a rapport before the negotiation begins.

You can build trust during the negotiation, too. Be open to their thoughts and opinions, and engage in active listening. Doing so can facilitate open communication and productive problem-solving. It can also provide insight into their motivations and priorities, enabling you to personalize your approach.

2. Set Clear Goals

Setting clear goals is one of the most important negotiation tactics . Ensure you know what you're aiming for, and set a stretch goal—one that's unlikely but possible.

Understanding your values, boundaries, and non-negotiables is just as crucial as having specific, tangible goals when entering the negotiation.

“You should define your values clearly before you negotiate," says Harvard Business School Professor Michael Wheeler in the online course Negotiation Mastery . "These are important decisions. Making them on the fly could cause you later regret.”

Be aware that your counterpart may hold different values. Recognize and anticipate that scenario while upholding your principles.

3. Know Your BATNA

Before approaching the bargaining table, you need to know the negotiation’s conditions. While you'll ideally find common ground with your counterpart, you possibly won’t, preventing you from achieving your desired outcome.

“It may seem odd, but the first thing to consider in preparation is what you’ll do if you're not able to reach an agreement,” Wheeler says in Negotiation Mastery .

The unfortunate truth is that your counterpart may not agree to your terms. If you can't resolve your differences, consider your best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA) , the course you'll take if the negotiation doesn't go how you want.

4. Strategize

Developing an effective negotiation strategy is critical to your preparation. Consider various factors, including your desired outcome, priorities and interests, assessment of the other party's goals and objectives, and any leverage or alternatives you have.

Determine the following:

- Your motivation for pursuing the negotiation

- The other party’s motivation for engaging with you

- How to create value for your counterpart

A well-developed negotiation strategy can help you stay focused and confident and make tactical decisions at the bargaining table. By thinking through potential scenarios and anticipating the other party's reactions and counterproposals, you'll be more prepared to respond in a manner that advances your interests.

“Put yourself in your counterpart's shoes," Wheeler says in Negotiation Mastery . "Think about what conditions might exist that would make them especially eager to deal with you.”

Related: 4 Examples of Business Negotiation Strategies

5. Be Ready to Improvise

The reality of negotiation is that it's unpredictable. Being prepared is key, but you must also be flexible and adaptable.

Anticipate various situations so you’re ready to think on your feet . Consider negotiating with friends or colleagues to practice improvising on the spot.

Remember: The more thoroughly you prepare, the better you'll be to handle the other party’s responses. Think through the best and worst outcomes and how you'll respond to each. Know what you’ll do if your counterpart is unwilling to listen to your thoughts, misunderstands your intentions, or even stereotypes you .

6. Develop Your Negotiation Skills

Have a variety of negotiation skills in your toolkit and take steps to develop them.

“Enhancing your negotiation skills has an enormous payoff,” Wheeler says in Negotiation Mastery . “It allows you to reach agreements that might otherwise slip through your fingers.”

Focus on improving skills like emotional intelligence , which can help you effectively empathize with others, communicate, and manage conflict in negotiations and business endeavors.

Check out the video below to learn more about essential negotiation skills you should develop, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more explainer content!

7. Know What Not to Do

There are several mistakes to avoid during the negotiation process that can hurt your reputation with your counterpart or even cause them to outright reject your proposal.

Refrain from the following:

- Forgetting to shake hands: It's crucial to start the conversation on the right note. Something as simple as forgetting to shake your counterpart's hand can decrease your chances of success.

- Allowing stress and anxiety to impact your demeanor: Feeling anxious is a natural part of negotiating. Instead of letting your anxiety negatively impact the conversation, channel it into excitement and use your emotions to your advantage .

- Not having an open mind: Listen to what the other party has to say. You might reach a mutually beneficial arrangement you hadn't previously considered.

- Negotiating against yourself: Don't start with the lowest offer you're willing to accept hoping it'll increase your chances of success. Be confident and assertive, and negotiate for what you want.

- Being aggressive or accusatory: While confidence is important, rudeness can result in a failed negotiation. Be polite, and don't be afraid to take a break or pause before speaking if you get frustrated.

- Immediately giving in to ultimatums: Misunderstandings can lead to hard stances. If you're faced with an ultimatum, don't immediately walk away from the negotiation. Continuing the conversation could help your counterpart gain clarity.

More importantly, don't sacrifice your integrity.

“Make sure that there's a clear understanding about how far you're willing to go when you're negotiating on behalf of other people or your organization," Wheeler says in Negotiation Mastery . "The people you're negotiating for deserve to know what lines you won't cross.”

Avoiding these mistakes is vital to becoming a good negotiator and achieving your desired outcomes.

Maximize Your Negotiation Success with an Online Course

If you want to improve your negotiation skills, remember that negotiations occur in both your personal and professional life.

Keep track of everyday negotiations—like resolving family conflicts or asking for favors—and reflect on them to learn what did and didn’t work. You can apply those lessons to business negotiations and better understand your strengths and weaknesses.

Another effective way to prepare for the bargaining table is through online negotiation training . For instance, Negotiation Mastery can equip you with the knowledge and skills to succeed in a range of situations, such as securing a business deal, advancing your career , or increasing your salary . It also provides simulations that enable you to gain practical experience with peers.

The time and effort you invest into preparing for a negotiation can pay dividends. If you're hoping for the best possible outcome, don't forget to plan ahead—you'll be glad you did over the long term.

Are you ready to take the next steps in developing your negotiation skills and furthering your career? Explore our online course Negotiation Mastery —one of our online leadership and management courses —and download our free e-book on how to become a more effective leader.

About the Author

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 9 min read

Negotiation Overview

A quick guide to negotiating.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Negotiation is a skill that everyone develops from an extremely young age, and everyone is a skilled negotiator by the time they can talk. On a business level, negotiation is often a highly complex and sophisticated process. Unfortunately, many people get stuck in a particular way of thinking about how to negotiate, limiting their efficiency and capabilities. Negotiation is a key business skill that needs to be developed through training and practice.

What Is Negotiation?

Negotiation is, at its simplest, a discussion intended to produce an agreement. It is the process of bargaining between two or more interests. [1]

The primary goal of negotiation should be to achieve a mutually acceptable deal, which accomplishes the objectives of the negotiation, without making the other party walk away or damaging a valuable relationship. This often requires substantial preparation, informed negotiation, compromise, and flexibility, depending on the situation. Some of the business situations which might require negotiation skills include:

- determining the details of a new commercial contract

- agreeing pay between management and a trades union

- bringing in new working practices

- changing employees' contractual arrangements

- arranging funding from a governing body

- agreeing next year's budgets

- working out the details of a major new project with colleagues

- agreeing objectives with team members

Stages of Negotiation

Most negotiations can be broken down into six main stages:

1. Preparation

Achieving objectives in the negotiation will be much easier if negotiators are fully prepared. A successful negotiator will ensure that they:

- are fully briefed on the subject matter of the negotiation

- are clear about their objectives and what they are trying to achieve

- have worked out their tactics and how best to put their case

2. Initial Exchanges

At the beginning of the negotiation, both parties will be sizing each other up. Both will be trying to find out and understand the other's position and requirements. The atmosphere in which the negotiation will be conducted should begin to form, and issues that need to be resolved later will emerge. At this stage it is probably wise to encourage the other side to say as much as possible, to listen a lot and not reveal too much too soon.

In this phase the negotiation begins to get serious, as both parties start to put forward their own offers of what they want to get out of the negotiation. During this stage, a number of different things will be happening:

- both sides will be searching for common ground, which could form the basis of an agreement

- both sides will be exploring possible areas of compromise, where ground could be conceded if necessary

- sticking points or objections, which will need to be resolved later, will begin to emerge

4. Bargaining

This is often the crunch-point of the negotiation, as the parties start to trade and exchange in the search for an agreement. Both parties will be aware of the limits they have set themselves on each of the negotiable issues, and therefore which issues they can concede and which they need to hold out for. This is the point at which the difficult issues will need to be resolved and is consequently a vulnerable point at which the negotiation could break down. There are many tools and techniques (such as BATNA and game theory ) that have been developed to determine bargaining positions when negotiating.

5. Securing Agreement

As the two parties arrive at their final positions, the negotiation could still break down. There are two common reasons for such a failure:

- potential loss of face in coming to a sensible compromise solution

- the last-minute introduction of a completely new set of conditions

In either of these situations, a final, small, unrelated concession, as a gesture of goodwill, may be necessary to secure the agreement. In order to reach a mutually satisfactory conclusion to the negotiation, care needs to be taken to ensure that:

- the best time to bring the negotiation to a conclusion is chosen

- a 'final' proposal is put forward only if it is really meant and if the reasons why no further movement is available are justified

- the final agreement is comprehensive, unambiguous and clearly understood by each party

6. Implementation

A deal is only successful if it is workable. A successful negotiator is one who has a sound track record of successfully implementing the agreement that has been reached. The implementation plan will need to incorporate the following:

- a comprehensive list of necessary activities

- timescales or deadlines for each of the activities

- a clear understanding of who will be responsible for carrying out each action

- the resources and information that will be necessary to carry out the activities

- who else needs to be involved or informed

- arrangements for coordination and monitoring

- how to review the implementation and evaluate the effectiveness of the negotiated solution

- who should be informed of this outcome

Negotiation Styles

While successful negotiators tend to do many of the same things, they often go about it in different ways. This is because there are a number of different negotiation styles. The style a negotiator adopts will depend upon many things, including:

- their knowledge of the subject matter which is under negotiation

- their personality

- what they know of the other party, and how much they trust them

- whether it is a one-to-one or a team negotiation

- the national or regional culture of the individual(s) involved

- the type of negotiation and its level of importance

- how much time is available for the process to take place

- whether the negotiation is a 'one-off' or one in a regular series of events

A simple, but effective, classification of negotiators is whether they are task-oriented or people-oriented . The former will pursue their objectives relentlessly, will be tough, aware of tactical ploys and have little concern about the effect they have on others. The latter, on the other hand, are highly concerned about the wellbeing of others, which can mean they are more likely to understand the emotional aspects of the negotiation and build rapport. However, negotiators who favor the people-oriented approach can put insufficient emphasis on business goals, making them a 'soft touch' for negotiators who favor the task-oriented approach. In reality though, it is not quite so simple: there are a number of intermediate points in between the two extremes. Bill Scott has identified three main styles of negotiator: [2]

- The fighter: highly task oriented and likely to go flat out to achieve objectives

- The collaborator: attempts to get everything into the open, is prepared to confront issues and be innovative in order to make a deal.

- The compromiser: tends to make significant use of compromise in order to settle deals.

The significance of negotiation styles is threefold:

- To be successful we must recognize the negotiating style of the other party and work out what impact this is likely to have on us.

- We must work out what our own natural negotiating style is and whether the combination of the two styles can lead to problems.

- We should decide how we could adjust our own negotiating style, if necessary, in order to cope with, and succeed in, the situation with which we will be faced.

Negotiation Tools and Techniques

Many tools and techniques have been developed to determine bargaining positions when negotiating. One of these advises negotiators to work out three negotiating positions in advance:

- Ideal: the best possible outcome

- Realistic: what they expect to achieve

- Fallback: minimum what they will accept.

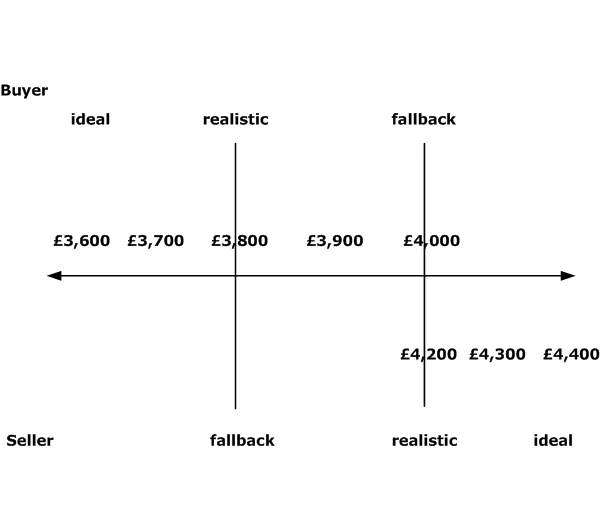

This strategy, also known as BATNA (Best Alternative to Negotiated Agreement) was developed by Fisher and Ury as part of the Harvard Negotiation Project at Harvard Law School. [3] Negotiators should also estimate what they think the negotiating positions of the other party will be. If there are overlapping areas, bargaining and agreement may be possible. For example, a car buyer would ideally like to pay £3,600 for a new car but, realistically, expects to have to pay £3,800, and as a fallback will pay no more than £4,000. The car salesperson will also have equivalent ideal, realistic and fallback positions:

As the diagram shows, there is a small degree of negotiating space between the two parties in this situation. The price where the two parties will find their compromise, if one is to be reached, is between £3,900 and £4,000. One of the major developments for 20th century negotiation was that of game theory. Game theory is strategic interaction between two or more players, who make decisions and negotiate while trying to anticipate the others' actions and reactions. [4] Techniques such as game theory, or the use of asymmetric information , give a trained negotiator an edge over someone relying on general life experience. [5] Game theory has become a useful negotiation tool for mapping out potential scenarios and assessing the options that both the parties face.

Qualities of a Successful Negotiator

Successful negotiations require an atmosphere of calm, reasonable discussion. This can often be difficult, as negotiations which have taken a significant amount of time and energy to prepare for, can easily become emotionally charged events. Key to thriving in these situations is the ability to distinguish between the issues involved in the negotiation, and the relationship with the other party. Discussing issues as a matter of mutual, legitimate concern can diffuse emotional aspects of a negotiation, and produce a stronger long-term relationship between the two parties. Negotiating to solve problems helps participants move away from an adversarial approach, aiding the search for a solution through co-operative work.

That is not to say that there is no place for playing the negotiation with specific techniques to gain an advantage (the other party is most likely doing the same), but these must be carefully considered, and the circumstances judged perfectly in order to avoid permanently damaging a relationship.

Pragmatism is an essential quality for a negotiator, with good, objective judgment required at all times. The negotiator needs to be able to judge precisely when to make concessions, when to play hardball, or when to back away from a deal. Negotiating formally is a skill that needs to be developed through training and practice. Individuals may well have been informally negotiating for their whole lives, but there are aspects of a formal negotiation, mentioned above, which need time, preparation and thought to master.

[1] http://www.thefreedictionary.com/negotiation (February 2009).

[2] Bill Scott, The Skills of Negotiating (Jaico Publishing House, 2005).

[3] Roger Fisher and William Ury, Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In , 2nd Ed (Penguin Putnam, 2008).

[4] In the 1950s, work on game theory really began to gather steam, specifically the work by John Nash , proving the existence of an equilibrium (the Nash Equilibrium), for non-co-operative games, and mathematician Albert Tucker , who developed the example of the Prisoner’s Dilemma . This model was an example of a non-zero-sum game i.e. a game that allows for collaboration, as opposed to a zero-sum game, a win-lose situation, in which a gain for one party means an equal loss for the other.

[5] Asymmetric information exchange occurs when one of the parties involved in a negotiation has more information concerning the process than the other party.

Join Mind Tools and get access to exclusive content.

This resource is only available to Mind Tools members.

Already a member? Please Login here

Get 20% off your first year of Mind Tools

Our on-demand e-learning resources let you learn at your own pace, fitting seamlessly into your busy workday. Join today and save with our limited time offer!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Most Popular

Newest Releases

How Do I Manage a Hybrid Team?

"That's not my job!" The 5 Phrases That Kill Collaboration

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

How well do i support performance management.

Reflect on how well you support performance management in your team.

Emotional Intelligence

Developing Strong "People Skills"

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

How to promote wellbeing at work.

This Methodology Guides You Through the Main Elements of Promoting Employee Wellbeing

How to Guides

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

- Model UN Guide

- Sample Documents

Research Resources

- Publications

- Secretary-General’s Message

- Competitive Bargaining vs. Cooperative problem solving

- Overview of this Guide

- How Decisions are Made at the UN

- How a State Becomes a UN Member

- UN Emblem and Flag

- UN Structure

- The 4 pillars of the United Nations

- UN Family of Organizations

- History of the United Nations

- Agenda, Workplan, Documents and Rules of Procedure

- Leadership Positions in the GA

- Leadership Positions in the Secretariat

- Leadership Positions in the Security Council

- Selecting Candidates for Leadership Positions

- Oversight of the Conference - Things to Consider

- Roles and Responsibilities of Elected Officials

- Delegate Preparation

- Pre-Conference

- During the Conference

- Action Phase: Making Decisions

- Adoption of Agenda and Work Programme

- Discussion Phase -- General Debate

- Opening and Closing of Plenary

- Plenary vs. Committee Meetings

- Differences Between GA Rules and some Model UN Rules of Procedure

- Significance of Groups

- The Purpose of Consultations

- General Considerations and Denationalization

- Procedural Roles of the Chairman: A Step-by-Step

- Substantive Role of the Chair

- The Chair's Activities in Guiding the Work of a Committee

- Drafting Resolutions

- Characteristics of Winning Proposals

- Fundamentals of Negotiation

- Making Consultations Happen

- The Process of Negotiation

- Groups of Member States

- Changing Audience and Cultural Sensitivity

- Engaging the Audience

- Forms of Address

- Preparation, Purpose and Structure

- General Information about the United Nations

- United Nations General Assembly

- United Nations Security Council

- United Nations Documents

- Other Online Resources

Competitive Bargaining vs. Cooperative Problem-Solving

One of the biggest challenges of negotiation is that there are two different approaches that call for opposite strategies: competitive bargaining and cooperative problem-solving. This section gives an overview of both approaches and provides a rationale for why only one of them is appropriate for international conferences.

Competitive Bargaining

Historically, the word negotiation means “business,” and negotiation has a major role in business transactions.

The crudest form of negotiation in an international conference resembles crude commercial negotiations, for example, when you are trying to buy or sell a second-hand car and the only point at issue is the price. In that case, the buyer wants to pay as little as possible, while the seller wants to receive as much as possible. A gain by one party means an equal loss by the other. This type of negotiation is sometimes referred to as “competitive bargaining.” It has been extensively studied over the centuries by traders everywhere and, more recently, in business schools.

You probably already understand this form of negotiation. The essential feature is that each party receives something that they accept as the outcome of the negotiation. At the simplest, they would receive equal shares; but the issues before international conferences are generally far too complex for that and the needs and capabilities of the nations concerned are too varied for any simple equilibrium. Instead, at the international level, the balance to be found is between trade-offs, in which not only the quantity but also the nature of what different parties receive is different.

Each party is concerned primarily to maximize its own gains and minimize the cost to themselves.

Then some important tactical principles come to the fore:

- Always ask for more than you expect to get. Think of some of the things asked for as “negotiating coin” that you can trade away in order to achieve your aim. You can also assume that the other party does not expect to get everything they ask for and that some of their requests are only negotiating coin.

- You might even start by demanding things you do not really hope to achieve, but which you know other parties strongly oppose. By doing so, you may hope that the other parties will make concessions to you just to refrain from pressing such demands.

- Always hide your “bottom line.” Because the other party’s aim is to concede to you as little as possible, you may get more if they are not aware of how little is acceptable to you.

- Take early and give late. Negotiators often undervalue whatever is decided in the early part of the negotiation and place excessive weight on whatever is agreed towards the end of the negotiation.

- As the negotiation progresses, carefully manage the “concession rate.” If you “concede” things to the other party too slowly, they many lose hope of achieving a satisfactory agreement; but if you “concede” too fast, they could end up with more than you needed to give them.

- The points at issue are seen as having the same worth for both sides—although they rarely do.

Precepts of this kind can readily generate a competitive or even combative spirit and encourage negotiators to consider a loss by their counterparts as a gain for themselves. It should be evident that such sentiments at the international level are harmful to relations and thus to the prospects of cooperation and mutual tolerance.

Cooperative Problem-Solving

An entirely different style of negotiation is more common in international conferences than “competitive bargaining,” both because it is generally more productive and is widely seen as more appropriate in dealings between representatives of sovereign States. This style of negotiation starts from the premise that you both have an interest in reaching agreement and therefore an interest in making proposals that the other is likely to agree to. In other words, each has an interest in the other(s) also being satisfied.

Achieving your objective requires that you also work to achieve the objectives of the other party (or parties)—to the extent that such effort is compatible with your objectives. The same applies to your counterpart(s): it is in their interest to satisfy you to the maximum extent possible. This makes negotiation a cooperative effort to find an outcome that is attractive to all parties.

To succeed in this type of negotiation, principles apply which are quite contrary to those that apply in “competitive bargaining,” namely:

- It is important not to request concessions from the other side that you know are impossible for them. If you do so, they will find it difficult to believe that you are genuinely working for an agreement.

- It is in your interest that the other party should understand your position. Indeed, perhaps they should even know your “bottom line.” If they understand how close they are to that “bottom line” on one point, they will also understand the necessity to include other elements that you value to give you an incentive to agree.

- Sometimes it is in your interest to “give” a lot to the other side early in the negotiation process to give them a strong incentive to conclude the negotiation and therefore “give” you what you need to be able to reach agreement.

- The “concession rate” may not be important.

- There is a premium on understanding that the same points have different values for different negotiators and on finding additional points on which to satisfy them.

- The Chair's Activities in Guiding the Work of a Committee

- ‹ Negotiation