Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

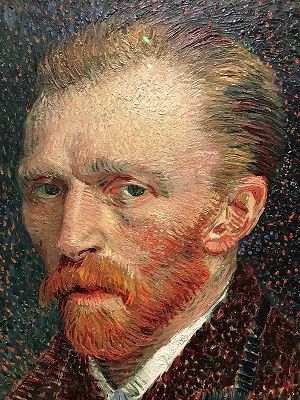

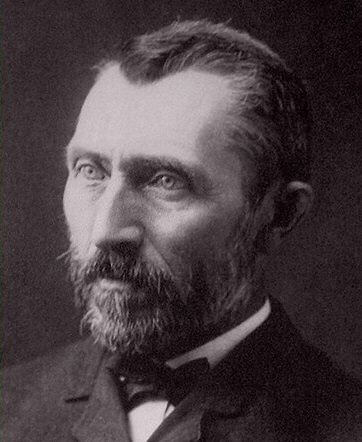

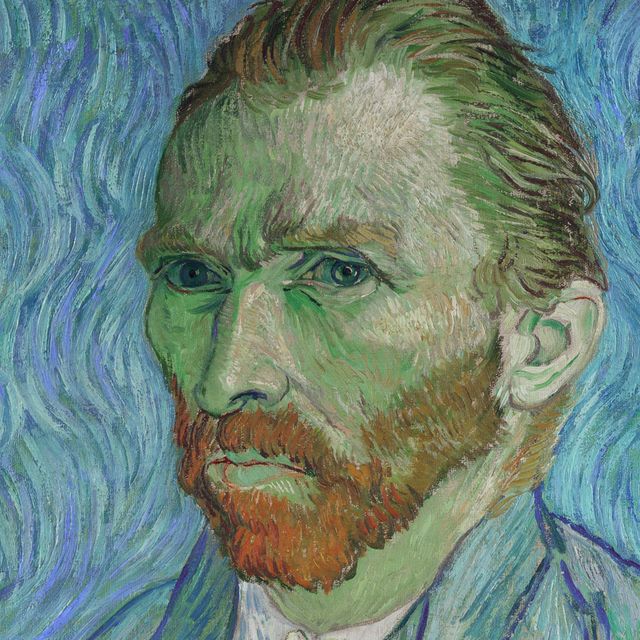

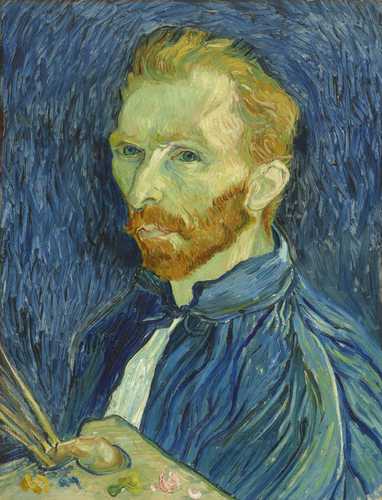

Vincent van gogh (1853–1890).

Road in Etten

Vincent van Gogh

Nursery on Schenkweg

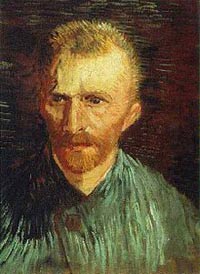

Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat (obverse: The Potato Peeler)

The Potato Peeler (reverse: Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat)

Street in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer

The Flowering Orchard

Peasant Woman Cooking by a Fireplace

Wheat Field with Cypresses

Corridor in the Asylum

L'Arlésienne: Madame Joseph-Michel Ginoux (Marie Julien, 1848–1911)

La Berceuse (Woman Rocking a Cradle; Augustine-Alix Pellicot Roulin, 1851–1930)

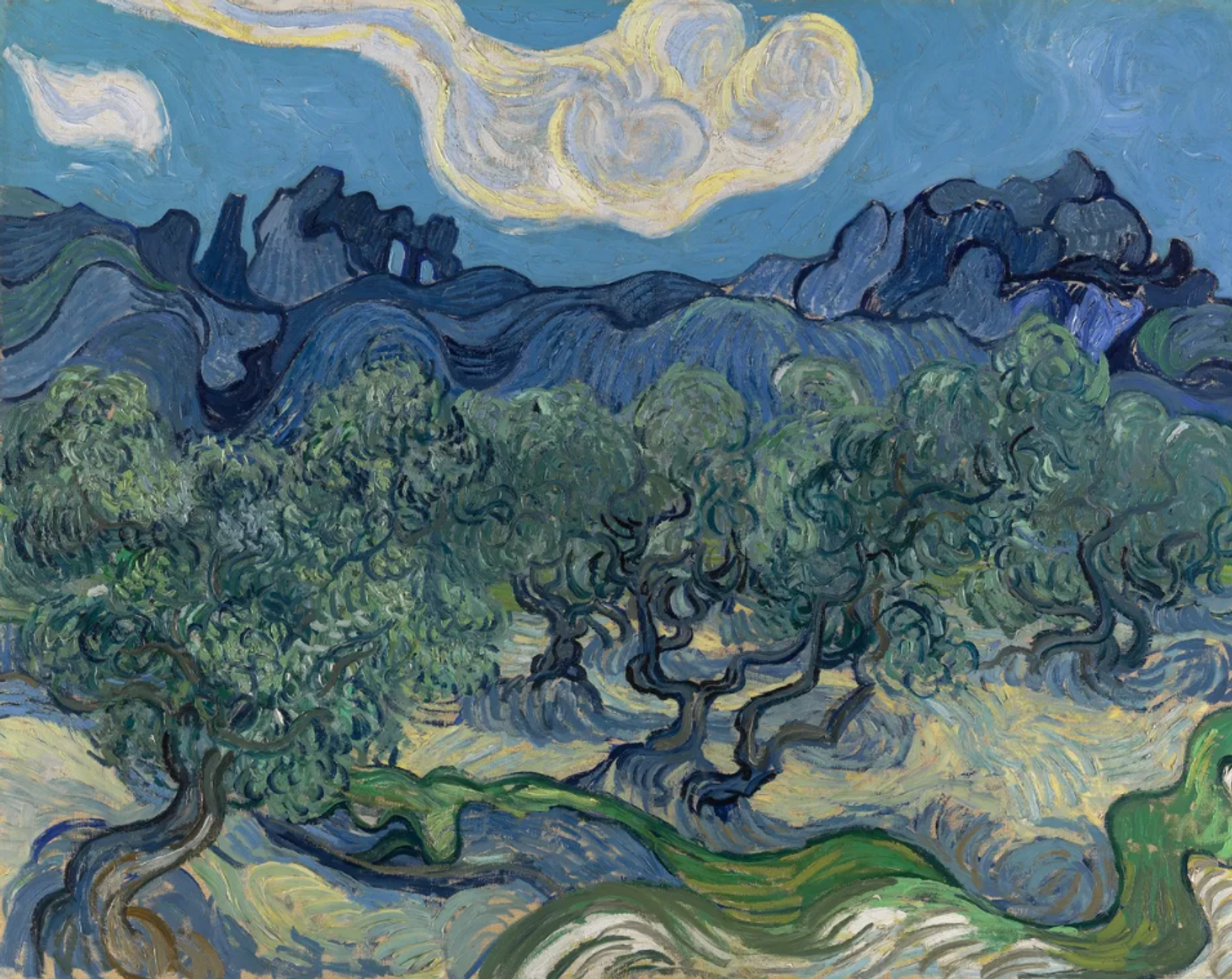

Olive Trees

First Steps, after Millet

Department of European Paintings , The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2004 (originally published) March 2010 (last revised)

Vincent van Gogh, the eldest son of a Dutch Reformed minister and a bookseller’s daughter, pursued various vocations, including that of an art dealer and clergyman, before deciding to become an artist at the age of twenty-seven. Over the course of his decade-long career (1880–90), he produced nearly 900 paintings and more than 1,100 works on paper. Ironically, in 1890, he modestly assessed his artistic legacy as of “very secondary” importance.

Largely self-taught, Van Gogh gained his footing as an artist by zealously copying prints and studying nineteenth-century drawing manuals and lesson books, such as Charles Bargue’s Exercises au fusain and cours de dessin . He felt that it was necessary to master black and white before working with color, and first concentrated on learning the rudiments of figure drawing and rendering landscapes in correct perspective. In 1882, he moved from his parents’ home in Etten to the Hague, where he received some formal instruction from his cousin, Anton Mauve, a leading Hague School artist. That same year, he executed his first independent works in watercolor and ventured into oil painting; he also enjoyed his first earnings as an artist: his uncle, the art dealer Cornelis Marinus van Gogh, commissioned two sets of drawings of Hague townscapes for which Van Gogh chose to depict such everyday sites as views of the railway station, gasworks, and nursery gardens ( 1972.118.281 ).

Van Gogh’s admiration for the Barbizon artists, in particular Jean-François Millet, influenced his decision to paint rural life. In the winter of 1884–85, while living with his parents in Nuenen, he painted more than forty studies of peasant heads, which culminated in his first multifigured, large-scale composition ( The Potato Eaters , Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam); in this gritty portrayal of a peasant family at mealtime, Van Gogh wrote that he sought to express that they “have tilled the earth themselves with the same hands they are putting in the dish.” Its dark palette and coarse application of paint typify works from the artist’s Nuenen period ( 67.187.70b ; 1984.393 ).

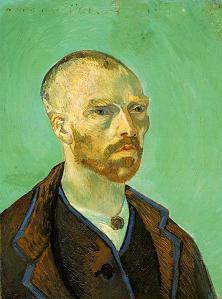

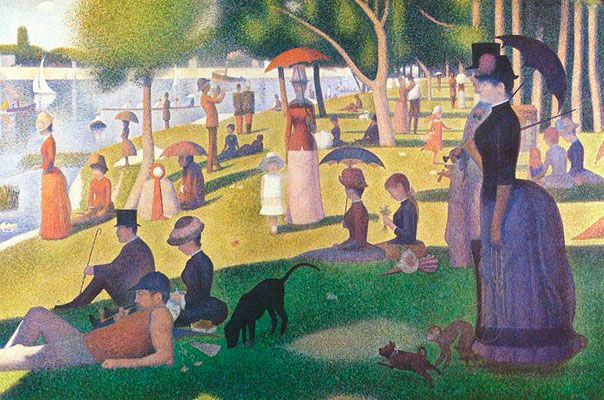

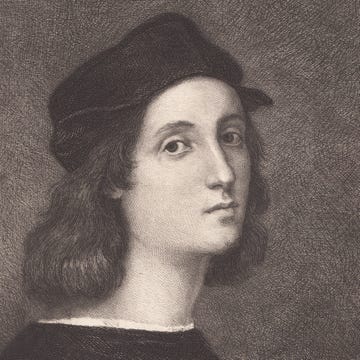

Interested in honing his skills as a figure painter, Van Gogh left the Netherlands in late 1885 to study at the Antwerp Academy in Belgium. Three months later, he departed for Paris, where he lived with his brother Theo, an art dealer with the firm of Boussod, Valadon et Cie, and for a time attended classes at Fernand Cormon’s studio. Van Gogh’s style underwent a major transformation during his two-year stay in Paris (February 1886–February 1888). There he saw the work of the Impressionists first-hand and also witnessed the latest innovations by the Neo-Impressionists Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. In response, Van Gogh lightened his palette and experimented with the broken brushstrokes of the Impressionists as well as the pointillist touch of the Neo-Impressionists, as evidenced in the handling of his Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat ( 67.187.70a ), which was painted in the summer of 1887 on the reverse of an earlier peasant study ( 67.187.70b ). In Paris, he executed more than twenty self-portraits that reflect his ongoing exploration of complementary color contrasts and a bolder style.

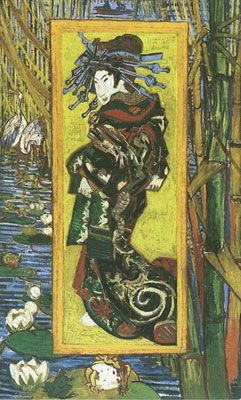

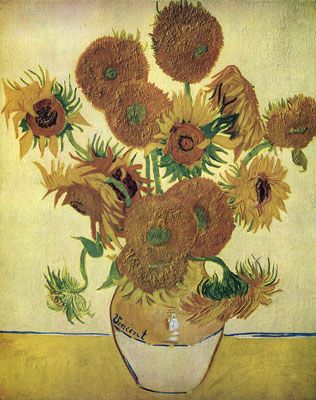

In February 1888, Van Gogh departed Paris for the south of France, hoping to establish a community of artists in Arles. Captivated by the clarity of light and the vibrant colors of the Provençal spring, Van Gogh produced fourteen paintings of orchards in less than a month, painting outdoors and varying his style and technique. The composition and calligraphic handling of The Flowering Orchard ( 56.13 ) suggest the influence of Japanese prints , which Van Gogh collected. The artist’s debt to ukiyo-e prints is also apparent in the reed pen drawings he made in Arles, distinguished by their great verve and linear invention ( 48.190.1 ). In August, he painted the still lifes Oleanders ( 62.24 ) and Shoes ( 1992.374 ); each work resonates with the artist’s personal symbolism. For Van Gogh, oleanders were joyous and life-affirming (much like the sunflower); he reinforced their significance with the compositional prominence accorded to Émile Zola’s 1884 novel La joie de vivre . The still life of unlaced shoes, which Van Gogh had apparently hung in Paul Gauguin ‘s “yellow room” at Arles, suggested, to Gauguin, the artist himself—he saw them as emblematic of Van Gogh’s itinerant existence.

Gauguin joined Van Gogh in Arles in October and abruptly departed in late December 1888, a move precipitated by Van Gogh’s breakdown, during which he cut off part of his left ear with a razor. Upon his return from the hospital in January, he resumed working on a portrait of the wife of the postmaster Joseph Roulin; although he painted all the members of the Roulin family, Van Gogh produced five versions of Madame Roulin as La Berceuse , shown holding the rope that rocks her newborn daughter’s cradle ( 1996.435 ). He envisioned her portrait as the central panel of a triptych, flanked by paintings of sunflowers. For Van Gogh, her image transcended portraiture, symbolically resonating as a modern Madonna; of its palette, which ranges from ocher to vermilion and malachite, Van Gogh expressed his desire that it “sing a lullaby with color,” underscoring the expressive role of color in his art.

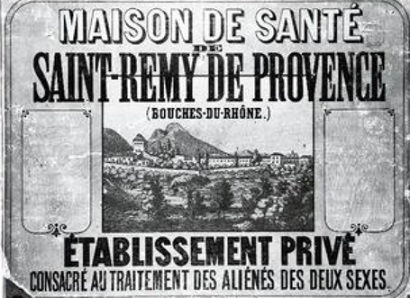

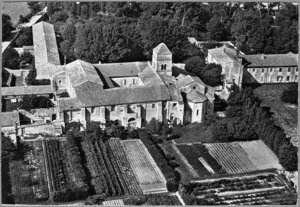

Fearing another breakdown, Van Gogh voluntarily entered the asylum at nearby Saint-Rémy in May 1889, where, over the course of the next year, he painted some 150 canvases. His initial confinement to the grounds of the hospital is reflected in his imagery, from his depictions of its corridors ( 48.190.2 ) to the irises and lilacs of its walled garden, visible from the window of the spare room he was allotted to use as a studio. Venturing beyond the grounds of the hospital, he painted the surrounding countryside, devoting series to its olive groves ( 1998.325.1 ) and cypresses, which he saw as characteristic of Provence. In June, he produced two paintings of cypresses, rendered in thick, impastoed layers of paint ( 49.30 ; Cypresses , Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo), likening the form of a cypress to an Egyptian obelisk in a letter to his brother Theo. These evocative trees figure prominently in a landscape, produced the same month ( 1993.132 ). Van Gogh regarded this work, with its sun-drenched wheat field undulating in the wind, as one of his “best” summer canvases. At Saint-Rémy, he also painted copies of works by such artists as Delacroix, Rembrandt , and Millet, using black-and-white photographs and prints. In fall and winter 1889–90, he executed twenty-one copies after Millet ( 64.165.2 ); he described his copies as “interpretations” or “translations,” comparing his role as an artist to that of a musician playing music written by another composer. During his last week at the asylum, he extended his repertoire of still life by painting four bouquets of Irises ( 58.187 ) and Roses ( 1993.400.5 ) as a final series comparable to the sunflower decoration he made earlier in Arles.

After a year at Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh left, in May 1890, to settle in Auvers-sur-Oise, where he was near his brother Theo in Paris and under the care of Dr. Paul Gachet, a homeopathic physician and amateur painter. In just over two months, Van Gogh averaged a painting a day; however, on July 27, 1890, he shot himself in the chest in a wheat field; he died two days later. His artistic legacy is preserved in the paintings and drawings he left behind, as well as in his voluminous correspondence, primarily with Theo, which lays bare his working methods and artistic intentions and serves as a reminder of his brother’s pivotal role as a mainstay of support throughout his career.

By the time of his death in 1890, Van Gogh’s work had begun to attract critical attention. His paintings were featured at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris between 1888 and 1890 and with Les XX in Brussels in 1890. As Gauguin wrote to him, his recent works, on view at the Indépendants in Paris, were regarded by many artists as “the most remarkable” in the show; and one of his paintings sold from the 1890 exhibition in Brussels. In January 1890, the critic Albert Aurier published the first full-length article on Van Gogh, aligning his art with the nascent Symbolist movement and highlighting the originality and intensity of his artistic vision. By the outbreak of World War I, with the discovery of his genius by the Fauves and German Expressionists, Vincent van Gogh had already come to be regarded as a vanguard figure in the history of modern art.

Department of European Paintings. “Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/gogh/hd_gogh.htm (originally published October 2004, last revised March 2010)

Further Reading

Brooks, David. Vincent van Gogh: The Complete Works . CD-ROM. Sharon, Mass.: Barewalls Publications, 2002.

Dorn, Roland, et al. Van Gogh Face to Face: The Portraits . New York: Thames & Hudson, 2000.

Druick, Douglas W., et al. Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Studio of the South . Exhibition catalogue. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2001.

Ives, Colta, et al. Vincent van Gogh: The Drawings . Exhibition catalogue. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005. See on MetPublications

Kendall, Richard. Van Gogh's Van Gogh's: Masterpieces from the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam . Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1998.

The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh . 3 vols. Boston: Bullfinch Press, 2000.

Pickvance, Ronald. Van Gogh in Arles . New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984. See on MetPublications

Pickvance, Ronald. Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers . New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986. See on MetPublications

Selected and edited by Ronald de Leeuw. The Letters of Vincent van Gogh . London: Penguin, 2006.

Stein, Susan Alyson, ed. Van Gogh: A Retrospective . New York: New Line Books, 2006.

Stolwijk, Chris, and Richard Thomson. Theo van Gogh . Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 1999.

Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Online resource.

Additional Essays by Department of European Paintings

- Department of European Paintings. “ The Rediscovery of Classical Antiquity .” (October 2002)

- Department of European Paintings. “ Architecture in Renaissance Italy .” (October 2002)

- Department of European Paintings. “ Titian (ca. 1485/90?–1576) .” (October 2003)

- Department of European Paintings. “ The Papacy and the Vatican Palace .” (October 2002)

Related Essays

- Paul Gauguin (1848–1903)

- Post-Impressionism

- The Transformation of Landscape Painting in France

- Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890): The Drawings

- Art of the Pleasure Quarters and the Ukiyo-e Style

- Childe Hassam (1859–1935)

- Claude Monet (1840–1926)

- Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

- Frans Hals (1582/83–1666)

- Georges Seurat (1859–1891) and Neo-Impressionism

- Henri Matisse (1869–1954)

- Impressionism: Art and Modernity

- James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

- Landscape Painting in the Netherlands

- The Lure of Montmartre, 1880–1900

- Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1844–1926)

- The Nabis and Decorative Painting

- Paul Cézanne (1839–1906)

- Rembrandt (1606–1669): Paintings

- Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669): Prints

- Woodblock Prints in the Ukiyo-e Style

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of Europe

- Central Europe and Low Countries, 1800–1900 A.D.

- France, 1800–1900 A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- 20th Century A.D.

- Agriculture

- Barbizon School

- Christianity

- Floral Motif

- French Literature / Poetry

- Impressionism

- Literature / Poetry

- Low Countries

- Modern and Contemporary Art

- Neo-Impressionism

- The Netherlands

- Oil on Canvas

- Plant Motif

- Pointillism

- Printmaking

- Religious Art

- Self-Portrait

Artist or Maker

- Delacroix, Eugène

- Gauguin, Paul

- Millet, Jean-François

- Seurat, Georges

- Signac, Paul

- Van Gogh, Vincent

- Van Rijn, Rembrandt

Online Features

- The Artist Project: “Sopheap Pich on Vincent van Gogh’s drawings”

- Connections: “Clouds” by Keith Christiansen

- Connections: “Dutch” by Merantine Hens

Vincent van Gogh

Dutch Draftsman and Painter

Summary of Vincent van Gogh

The iconic tortured artist, Vincent Van Gogh strove to convey his emotional and spiritual state in each of his artworks. Although he sold only one painting during his lifetime, Van Gogh is now one of the most popular artists of all time. His canvases with densely laden, visible brushstrokes rendered in a bright, opulent palette emphasize Van Gogh's personal expression brought to life in paint. Each painting provides a direct sense of how the artist viewed each scene, interpreted through his eyes, mind, and heart. This radically idiosyncratic, emotionally evocative style has continued to affect artists and movements throughout the 20 th century and up to the present day, guaranteeing Van Gogh's importance far into the future.

Accomplishments

- Van Gogh's dedication to articulating the inner spirituality of man and nature led to a fusion of style and content that resulted in dramatic, imaginative, rhythmic, and emotional canvases that convey far more than the mere appearance of the subject.

- Although the source of much upset during his life, Van Gogh's mental instability provided the frenzied source for the emotional renderings of his surroundings and imbued each image with a deeper psychological reflection and resonance.

- Van Gogh's unstable personal temperament became synonymous with the romantic image of the tortured artist. His self-destructive talent was echoed in the lives of many artists in the 20 th century.

- Van Gogh used an impulsive, gestural application of paint and symbolic colors to express subjective emotions. These methods and practice came to define many subsequent modern movements from Fauvism to Abstract Expressionism .

The Life of Vincent van Gogh

Vincent expressed his life via his works. As he famously said, "real painters do not paint things as they are... they paint them as they themselves feel them to be."

Important Art by Vincent van Gogh

The Potato Eaters

This early canvas is considered Van Gogh's first masterpiece. Painted while living among the peasants and laborers in Nuenen in the Netherlands, Van Gogh strove to depict the people and their lives truthfully. Rendering the scene in a dull palette, he echoed the drab living conditions of the peasants and used ugly models to further iterate the effects manual labor had upon these workers. This effect is heightened by his use of loose brushstrokes to describe the faces and hands of the peasants as they huddle around the singular, small lantern, eating their meager meal of potatoes. Despite the evocative nature of the scene, the painting was not considered successful until after Van Gogh's death. At the time this work was painted, the Impressionists had dominated the Parisian avant-garde for over a decade with their light palettes. It is not surprising that Van Gogh's brother, Theo, found it impossible to sell paintings from this period in his brother's career. However, this work not only demonstrates Van Gogh's commitment to rendering emotionally and spiritually laden scenes in his art, but also established ideas that Van Gogh followed throughout his career.

Oil on canvas - The Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

The Courtesan (after Eisen)

While in Paris, Van Gogh was exposed to a myriad of artistic styles, including the Japanese Ukiyo-e woodblock prints. These prints were only made available in the West in the mid-19 th century. Van Gogh collected works by Japanese ukiyo-e masters like Hiroshige and Hokusai and claimed these works were as important as works by European artists, like Rubens and Rembrandt. Van Gogh was inspired to create this particular painting by a reproduction of a print by Keisai Eisen that appeared on the May 1886 cover of the magazine Paris Illustré . Van Gogh enlarges Eisen's image of the courtesan, placing her in a contrasting, golden background bordered by a lush water garden based on the landscapes of other prints he owned. This particular garden is populated by frogs and cranes, both of which were allusions to prostitutes in French slang. While the stylistic features exhibited in this painting, in particular the strong, dark outlines and bright swaths of color, came to define Van Gogh's mature style, he also made the work his own. By working in paint rather than a woodblock print, Van Gogh was able to soften the work, relying on visible brushstrokes to lend dimension to the figure and her surroundings as well as creating a dynamic tension across the surface not present in the original prints.

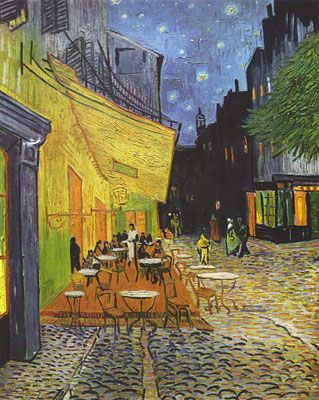

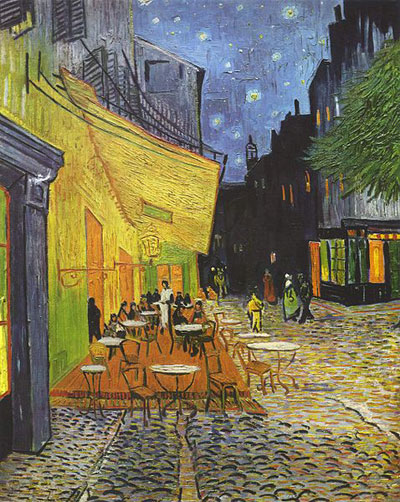

Café Terrace At Night

This was one of the scenes Van Gogh painted during his stay in Arles and a painting where he used his powerful nocturnal background. Using contrasting colors and tones, Van Gogh achieved a luminous surface that pulses with an interior light, almost in defiance of the darkening sky. The lines of composition all point to the center of the work drawing the eye along the pavement as if the viewer is strolling the cobblestone streets. The café still exists today and is a "mecca" for van Gogh fans visiting the south of France. Describing this painting in a letter to his sister he wrote, "Here you have a night painting without black, with nothing but beautiful blue and violet and green and in this surrounding the illuminated area colors itself sulfur pale yellow and citron green. It amuses me enormously to paint the night right on the spot..." Painted on the street at night, Van Gogh recreated the setting directly from his observations, a practice inherited from the Impressionists. However, unlike the Impressionists, he did not record the scene merely as his eye observed it, but imbued the image with a spiritual and psychological tone that echoed his individual and personal reaction. The brushstrokes vibrate with the sense of excitement and pleasure Van Gogh experienced while painting this work.

Oil on canvas - Kröller-Muller Museum, Otterlo

Van Gogh's Sunflower series was intended to decorate the room that was set aside for Gauguin at the "Yellow House," his studio and apartment in Arles. The lush brushstrokes built up the texture of the sunflowers and Van Gogh employed a wide spectrum of yellows to describe the blossoms, due in part to recently invented pigments that made new colors and tonal nuances possible. Van Gogh used the sunny hues to express the entire lifespan of the flowers, from the full bloom in bright yellow to the wilting and dying blossoms rendered in melancholy ochre. The traditional painting of a vase of flowers is given new life through Van Gogh's experimentation with line and texture, infusing each sunflower with the fleeting nature of life, the brightness of the Provencal summer sun, as well as the artist's mindset.

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery, London

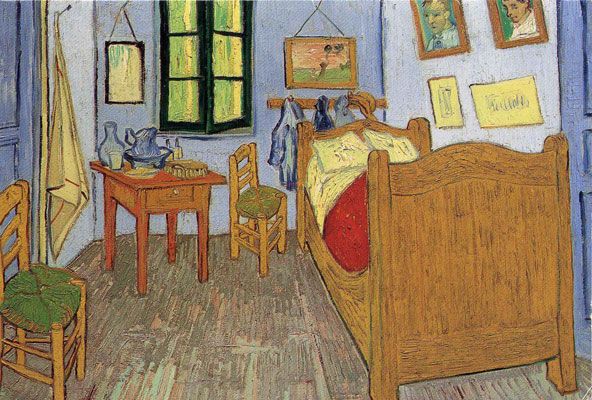

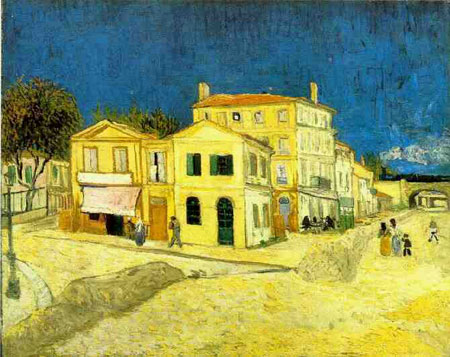

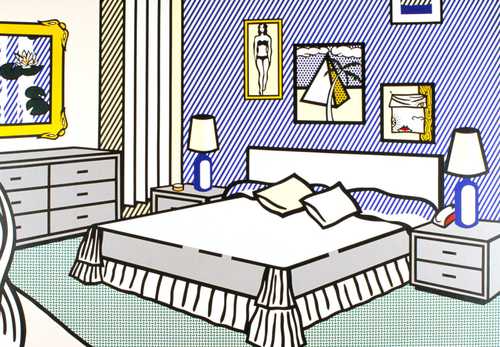

The Bedroom

Van Gogh's Bedroom depicts his living quarters at 2 Place Lamartine, Arles, known as the "Yellow House". It is one of his most well known images. His use of bold and vibrant colors to depict the off-kilter perspective of his room demonstrated his liberation from the muted palette and realistic renderings of the Dutch artistic tradition, as well as the pastels commonly used by the Impressionists. He labored over the subject matter, colors, and arrangements of this composition, writing many letters to Theo about it, "This time it's just simply my bedroom, only here color is to do everything, and giving by its simplification a grander style to things, is to be suggestive here of rest or of sleep in general. In a word, looking at the picture ought to rest the brain, or rather the imagination." While the bright yellows and blues might at first seem to echo a sense of disquiet, the bright hues call to mind a sunny summer day, evoking as sense of warmth and calm, as Van Gogh intended. This personal interpretation of a scene in which particular emotions and memories drive the composition and palette is a major contribution to modernist painting.

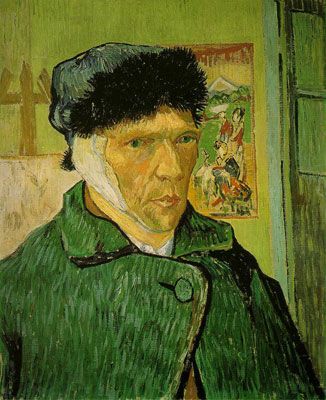

Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear

After cutting off a portion of his left earlobe during a manic episode while in Arles, Van Gogh painted Self Portrait with a Bandaged Ear while recuperating and reflecting on his illness. He believed that the act of painting would help restore balance to his life, demonstrating the important role that artistic creation held for him. The painting bears witness to the artist's renewed strength and control in his art, as the composition is rendered with uncharacteristic realism, where all his facial features are clearly modeled and careful attention is given to contrasting textures of skin, cloth, and wood. The artist depicts himself in front of an easel with a canvas that is largely blank and a Japanese print hung on the wall. The loose and expressive brushstrokes typical of Van Gogh are clearly visible; the marks are both choppy and sinuous, at times becoming soft and diffuse, creating a tension between boundaries that are otherwise clearly marked. The strong outlines of his coat and hat mimic the linear quality of the Japanese print behind the artist. At the same time, Van Gogh deployed the technique of impasto, or the continual layering of wet paint, to develop a richly textured surface, which furthers the depth and emotive force of the canvas. This self-portrait, one of many Van Gogh created during his career, has an intensity unparalleled in its time, which is elucidated in the frank manner in which the artist portrays his self-inflicted wound as well as the evocative way he renders the scene. By combining influences as diverse as the loose brushwork of the Impressionists and the strong outlines from Japanese woodblock printing, Van Gogh arrived at a truly unique mode of expression in his paintings.

Oil on canvas - The Courtauld Gallery, London

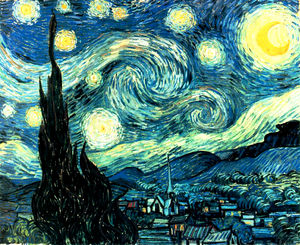

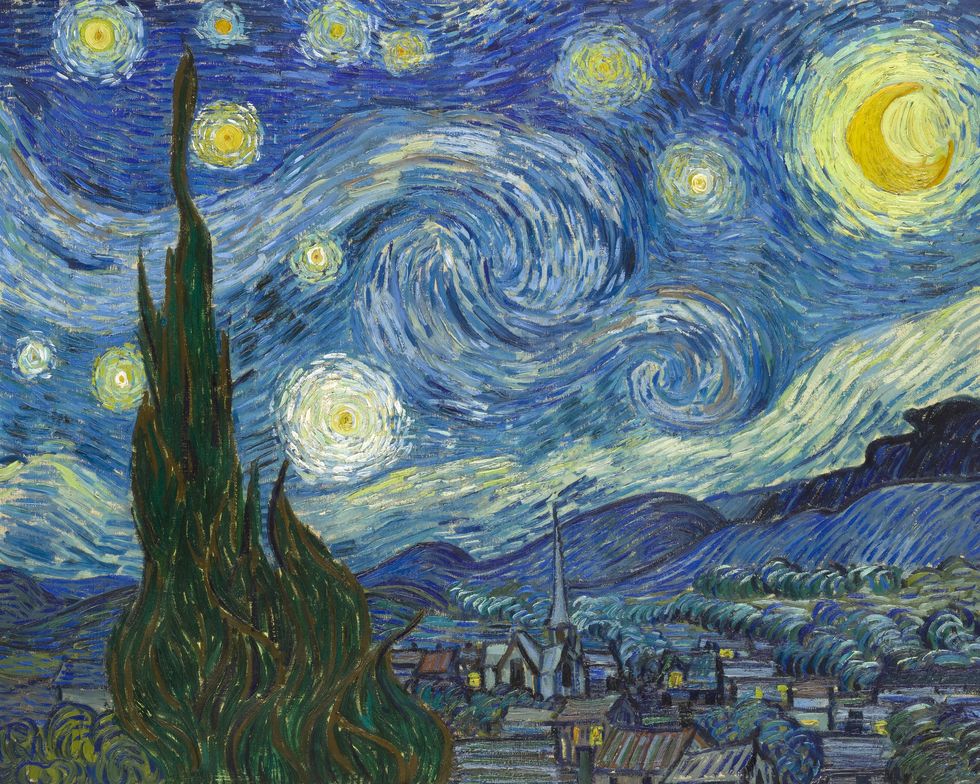

Starry Night

Starry Night is often considered to be Van Gogh's pinnacle achievement. Unlike most of his works, Starry Night was painted from memory, and not out in the landscape. The emphasis on interior, emotional life is clear in his swirling, tumultuous depiction of the sky - a radical departure from his previous, more naturalistic landscapes. Here, Van Gogh followed a strict principal of structure and composition in which the forms are distributed across the surface of the canvas in an exact order to create balance and tension amidst the swirling torsion of the cypress trees and the night sky. The result is a landscape rendered through curves and lines, its seeming chaos subverted by a rigorous formal arrangement. Evocative of the spirituality Van Gogh found in nature, Starry Night is famous for advancing the act of painting beyond the representation of the physical world.

Oil on canvas - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

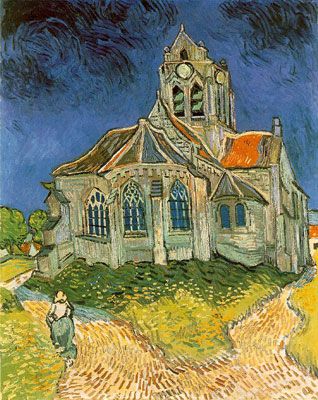

Church at Auvers

After Van Gogh left the asylum at Saint-Remy in May 1890 he travelled north to Auvers, outside of Paris. Church at Auvers is one of the most well-known images from the last few months of Van Gogh's life. Imbuing the landscape with movement and emotion, he rendered the scene with a palette of vividly contrasting colors and brushstrokes that lead the viewer through painting. Van Gogh distorted and flattened out the architecture of the church and depicted it caught within its own shadow - which reflects his own complex relationship to spirituality and religion. Van Gogh conveys a sense that true spirituality is found in nature, not in the buildings of man. The continued influence of Japanese woodblock printing is clear in the thick dark outlines and the flat swaths of color of the roofs and landscape, while the visible brushstrokes of the Impressionists are elongated and emphasized. The use of the acidic tones and the darkness of the church alludes to the impending mental disquiet that would eventually erupt within Van Gogh and lead to his suicide. This sense of instability plagued Van Gogh throughout his life, infusing his works with a unique blend of charm and tension.

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

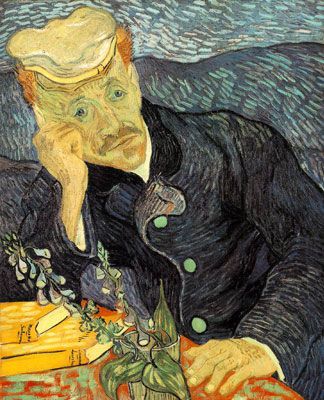

Paul-Ferdinand Gachet

Dr. Gachet was the homeopathic physician that treated Van Gogh after he was released from Saint-Remy. In the doctor, the artist found a personal connection, writing to his sister, "I have found a true friend in Dr. Gachet, something like another brother, so much do we resemble each other physically and also mentally." Van Gogh depicts Gachet seated at a red table, with two yellow books and foxglove in a vase near his elbow. The doctor gazes past the viewer, his eyes communicating a sense of inner sadness that reflects not only the doctor's state of mind, but Van Gogh's as well. Van Gogh focused the viewer's attention on the depiction of the doctor's expression by surrounding his face with the subtly varied blues of his jacket and the hills of the background. Van Gogh wrote to Gauguin that he desired to create a truly modern portrait, one that captured the "the heartbroken expression of our time." Rendering Gachet's expression through a blend of melancholy and gentility, Van Gogh created a portrait that has resonated with viewers since its creation. A recent owner, Ryoei Saito, even claimed he planned to have the painting cremated with him after his death, as he was so moved by the image. The intensity of emotion that Van Gogh poured into each brushstroke is what has made his work so compelling to viewers over the decades, inspiring countless artists and individuals.

Oil on canvas - Private Collection

Biography of Vincent van Gogh

Vincent Van Gogh was born the second of six children into a religious Dutch Reformed Church family in the south of the Netherlands. His father, Theodorus Van Gogh, was a clergyman and his mother, Anna Cornelia Carbentus, was the daughter of a bookseller. Van Gogh exhibited unstable moods during his childhood, and showed no early inclination toward art-making, though he excelled at languages while attending two boarding schools. In 1868, he abandoned his studies and never successfully returned to formal schooling.

Early Training

In 1869, Van Gogh apprenticed at the headquarters of the international art dealers Goupil & Cie in Paris and eventually worked at the Hague branch of the firm. He was relatively successful as an art dealer and stayed with the firm for almost a decade. In 1872, Van Gogh began exchanging letters with his younger brother Theo. This correspondence continued through the end of Vincent's life. The following year, Theo himself became an art dealer, and Vincent was transferred to the London office of Goupil & Cie. Around this time, Vincent became depressed and turned to God.

After several transfers between London and Paris, Van Gogh was let go from his position at Goupil's and decided to pursue a life in the clergy. While living in southern Belgium as a poor preacher, he gave away his possessions to the local coal-miners until the church dismissed him because of his overly enthusiastic commitment to his faith. In 1880, Van Gogh decided he could be an artist and still remain in God's service, writing, "To try to understand the real significance of what the great artists, the serious masters, tell us in their masterpieces, that leads to God; one man wrote or told it in a book; another, in a picture." Van Gogh was still a pauper, but Theo sent him some money for survival. Theo financially supported his elder brother his entire career, as Vincent made virtually no money from making art.

A year later, in 1881, dire poverty motivated Van Gogh to move back home with his parents, where he taught himself to draw. He became infatuated with his cousin, Kee Vos-Stricker. His continued pursuit of her affection, despite utter rejection, eventually split the family. With the support of Theo, Van Gogh moved to the Hague, rented a studio, and studied under Anton Mauve - a leading member of the Hague School. Mauve introduced Van Gogh to the work of the French painter Jean-François Millet , who was renowned for depicting common laborers and peasants.

In January 1882, while wandering the streets of The Hague, Van Gogh encountered a young prostitute (who also worked as a seamstress and housecleaner) by the name of Clasina Maria Hoornik. He soon came to refer to her as Christien, which he then shortened to, simply, Sien. She was destitute, addicted to alcohol, pregnant, and had her five year-old daughter Maria Wilhelmina, in tow. Van Gogh took pity on her, and took her into his care for the next year and a half. This dismayed his friends and family, and some of his patrons and benefactors, including his cousin-in-law Anton Mauve, and art dealer Hermanus Tersteeg, abruptly withdrew their support for him.

While Sien's account of their relationship portrays it as one merely of convenience and benevolence, it seems that Van Gogh felt more of a connection, and even had plans to marry her. In return for his support, Sien (as well as her children and mother) modeled for over fifty of Van Gogh's works, such as his 1882 drawing Sorrow , in which Sien appears pregnant, and which the artist once called "the best figure I've drawn". It seems, however, that what Van Gogh valued about her was the challenging life she had faced (she had during her life, become pregnant four different times by four different men, all of whom had abandoned her, and two of the children had died during infancy). He once referred to her as "pockmarked" and "no longer beautiful”, and often depicted her frowning, and in difficult or unflattering situations. Sien and her family also appeared in Van Gogh’s 1883 series The Public Soup Kitchen .

Mature Period

In 1884, after moving to Nuenen, Netherlands, Van Gogh began drawing the weathered hands, heads, and other anatomical features of workers and the poor, determined to become a painter of peasant life like Millet. Although he found a professional calling, his personal life was in shambles. Van Gogh accused Theo of not trying hard enough to sell his paintings, to which Theo replied that Vincent's dark palette was out of vogue compared to the bold and bright style of the Impressionist artists that was popular. Suddenly, on March 26, 1885, their father died from a stroke, putting pressure on Van Gogh to have a successful career. Shortly afterward, he completed the Potato Eaters (1885), his first large-scale composition and great work.

Leaving the Netherlands for the last time, in 1885 Van Gogh enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. There he discovered the art of Baroque painter Peter Paul Rubens , whose swirling forms and loose brushwork had a clear impact on the young artist's style. However, the rigidity of academicism of the school did not appeal to Van Gogh and he left for Paris the following year. He moved in with Theo in Montmartre - the artist's district in northern Paris - and studied with painter Fernand Cormon, who introduced the young artist to the Impressionists. The influence of artists such as Claude Monet , Camille Pissarro , Edgar Degas , and Georges Seurat , as well as pressure from Theo to sell paintings, motivated Van Gogh to adopt a lighter palette.

From 1886 to 1888, Van Gogh became acutely interested in Japanese prints and began to avidly study and collect them, even curating an exhibition of them at a Parisian restaurant. In late 1887, Van Gogh organized an exhibition that included his work and that of his colleagues Emile Bernard and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec , and in early 1888, he exhibited with the Neo-impressionists Georges Seurat and Paul Signac at the Salle de Repetition of the Theatre Libre d'Antoine.

Late Years and Death

The majority of Van Gogh's best-known works were produced during the final two years of his life. During the fall and winter of 1888, Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin lived and worked together in Arles in the south of France, where Van Gogh eventually rented four rooms at 2 Place Lamartine, which was dubbed the "Yellow House" for its citron hue. The move to Provence began as a plan for a new artist's community in Arles as alternative to Paris and came at a critical point in each of the artists' careers. While at the "Yellow House" Gauguin and Van Gogh worked closely together and developed a concept of color symbolic of inner emotion and not dependent upon nature. Despite enormous productivity, Van Gogh suffered from various bouts of mental instability, likely including epilepsy, psychotic episodes, delusions, and bipolar disorder. Gauguin left for Tahiti, partially as a means of escaping Van Gogh's increasingly erratic behavior. The artist slipped away after a particularly violent fight in which Van Gogh threatened Gauguin with a razor and then cut off part of his own left ear.

On May 8, 1889, reeling from his deteriorating mental condition, Van Gogh voluntarily committed himself into a psychiatric institution in Saint-Remy, near Arles. As the weeks passed, his mental well-being remained stable and he was allowed to resume painting. This period became one of his most productive. In the year spent at Saint-Remy, Van Gogh created over 100 works, including Starry Night (1889). The clinic and its garden became his main subjects, rendered in the dynamic brushstrokes and lush palettes typical of his mature period. On supervised walks, Van Gogh immersed himself in the experience of the natural surroundings, later recreating from memory the olive and cypress trees, irises, and other flora that populated the clinic's campus.

Shortly after leaving the clinic, Van Gogh moved north to Auvers-sur-Oise outside of Paris, to the care of a homeopathic doctor and amateur artist, Dr. Gachet. The doctor encouraged Van Gogh to paint as part of his recovery, and he happily obliged. He avidly documented his surroundings in Auvers, averaging roughly a painting a day over the last months of his life. However, after Theo disclosed his plan to go into business for himself and explained funds would be short for a while, Van Gogh's depression deepened sharply. On July 27, 1890, he wandered into a nearby wheat field and shot himself in the chest with a revolver. Although Van Gogh managed to struggle back to his room, his wounds were not treated properly and he died in bed two days later. Theo rushed to be at his brother's side during his last hours and reported that his final words were: "The sadness will last forever."

The Legacy of Vincent van Gogh

Clear examples of Van Gogh's wide influence can be seen throughout art history. The Fauves and the German Expressionists worked immediately after Van Gogh and adopted his subjective and spiritually inspired use of color. The Abstract Expressionists of the mid-20 th century made use of Van Gogh's technique of sweeping, expressive brushstrokes to indicate the artist's psychological and emotional state. Even the Neo-Expressionists of the 1980s, like Julian Schnabel and Eric Fischl , owe a debt to Van Gogh's expressive palette and brushwork. In popular culture, his life has inspired music and numerous films, including Vincente Minelli's Lust for Life (1956), which explores Van Gogh and Gauguin's volatile relationship. In his lifetime, Van Gogh created 900 paintings and made 1,100 drawings and sketches, but only sold one painting during his career. With no children of his own, most of Van Gogh's works were left to brother Theo.

Influences and Connections

Useful Resources on Vincent van Gogh

- Vincent Van Gogh: A Biography By Julius Meier-Graefe

- Stranger On The Earth: A Psychological Biography Of Vincent Van Gogh By Albert J. Lubin

- Vincent Van Gogh: Portrait of an Artist By Jan Greenberg, Sandra Jordan

- Dear Theo: The Autobiography of Vincent Van Gogh By Irving Stone, Jean Stone

- Letters of Vincent Van Gogh Our Pick By Vincent Van Gogh, Mark Roskill

- Van Gogh: The Complete Paintings Our Pick By Ingo F. Walther, Rainer Metzger

- Van Gogh in Provence and Auvers By Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov

- Vincent's Colors By Vincent Van Gogh, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Vincent Van Gogh: The Drawings By Colta Ives, Susan Alyson Stein, Sjraar Van Heugten, Marije Vellekoop

- The Vincent Van Gogh Museum

- The Vincent Van Gogh Gallery Comprehensive image gallery of the artist's works

- Vincent Van Gogh: The Letters Our Pick Archives of Van Gogh's complete letters

- Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night Interactive website for the 2008 MoMA Exhibition

- Van Gogh's Ear and Modern Painting Our Pick By Adam Gopnik / The New Yorker / January 4, 2010

- Van Gogh's Night Visions By Paul Trachtman / Smithsonian Magazine / January 2009

- Nocturnal Van Gogh, Illuminating the Darkness Our Pick By Roberta Smith / The New York Times / September 18, 2008

- The Evolution of a Master Who Dreamed on Paper By Michael Kimmelman / The New York Times / October 14, 2005

- Where Van Gogh's Art Reached its Zenith By Grace Glueck / The New York Times / October 7, 1984

- Lust for Life Our Pick Book by Irving Stone

- Vincent & Theo Robert Altman's film about the brothers Van Gogh

- Don McLean's song 'Vincent (Starry Starry Night)'

Similar Art

Boulevard des Capucines (1873)

Hoar Frost, the Old Road to Ennery, Pointoise (1873)

Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte (1884-86)

Related artists.

Related Movements & Topics

Content compiled and written by The Art Story Contributors

Edited and published by The Art Story Contributors

Biography of Vincent van Gogh

Van Gogh received a fragmentary education: one year at the village school in Zundert, two years at a boarding school in Zevenbergen, and eighteen months at a high school in Tilburg. At sixteen he began working at the Hague gallery of the French art dealers Goupil et Cie., in which his uncle Vincent was a partner. His brother Theo, who was born 1 May 1857, later worked for the same firm. In 1873 Goupil's transferred Vincent to London, and two years later they moved him to Paris, where he lost all ambition to become an art dealer. Instead, he immersed himself in religion, threw out his modern, worldly book, and became "daffy with piety", in the words of his sister Elisabeth. He took little interest in his work, and was dismissed from his job at the beginning of 1876.

Van Gogh then took a post as an assistant teacher in England, but, disappointed by the lack of prospects, returned to Holland at the end of the year. He now decided to follow in his father's footsteps and become a clergyman. Although disturbed by his fanaticism and odd behavior, his parents agreed to pay for the private lessons he would need to gain admission to the university. This proved to be another false start. Van Gogh abandoned the lessons, and after brief training as an evangelist went to the Borinage coal-mining region in the south of Belgium. His ministry among the miners led him to identify deeply with the workers and their families. In 1897, however, his appointment was not renewed, and his parents despaired, regarding him as a social misfit. In an unguarded moment, his father even spoke of committing him to a mental asylum.

Vincent, too, was at his wits' end, and after a long period of solitary soul-searching in the Borinage he decided to follow Theo's advice and become an artist. His earlier desire to help his fellowman was an evangelist gradually developed into an urge, as he later wrote, to leave mankind "some memento in the form of drawings of paintings - not made to please any particular movement, but to express a sincere human feeling."

His parents could not go along with this latest change of course, and financial responsibility for Vincent passed to his brother Theo, who was now working in the Paris gallery of Boussod, Valadon et Cie., the successor to Goupil's. It was because of Theo's loyal support that Van Gogh later came to regard his oeuvre as the fruits of his brother's efforts on his behalf. A lengthy correspondence between the two brothers (which began in August 1872) would continue until the last days of Vincent's life.

When Van Gogh decided to become an artist, no one, not even himself, suspected that he had extraordinary gifts. His evolution from an inept but impassioned novice into a truly original master was remarkably rapid. He eventually proved to have an exceptional feel for bold, harmonious color effects, and an infallible instinct for choosing simple but memorable compositions.

In order to prepare for his new career, Van Gogh went to Brussels to study at the academy, but left after only nine months. There he got to know Anthon van Rappard, who was to be his most important artist friend during his Dutch period.

In April 1881, Van Gogh went to live with his parents in Etten in North Brabant, where he set himself the task of learning how to draw. He experimented endlessly with all sorts of drawing materials, and concentrated on mastering technical aspects of his craft like perspective, anatomy, and physiognomy. Most of his subjects were taken from peasant life.

At the end of 1881 he moved to The Hague, and there, too, he concentrated mainly on drawing. At first he took lessons from Anton Mauve, his cousin by marriage, but the two soon fell out, partly because Mauve was scandalized by Vincent's relationship with Sien Hoornik, a pregnant prostitute who already had an illegitimate child. Van Gogh made a few paintings while in The Hague , but drawing was his main passion. In order to achieve his ambition of becoming a figure painter, he drew from the live model whenever he could.

In September 1883 he decided to break off the relationship with Sien and follow in the footsteps of artists like Van Rappard and Mauve by trying his luck in the picturesque eastern province of Drenthe, which was fairly inaccessible in those days. After three months, however, a lack of both drawing materials and models forced him to leave. He decided once again to move in with his parents, who were now living in the North Brabant village of Nuenen, near Eindhoven.

In Nuenen, Van Gogh first began painting regularly, modeling himself chiefly on the French painter Jean-Francois Millet (1814 - 1875), who was famous throughout Europe for his scenes of the harsh life of peasants. Van Gogh set to work with an iron will, depicting the life of the villagers and humble workers. he made numerous scenes of weavers. In May 1884, he moved into rooms he had rented from the sacristan of local Catholic church, one of which he used as his studio.

At the end of 1884 he began painting and drawing a major series of heads and work-roughened peasant hands in preparation for a large and complex figure piece that he was planning. In April 1885 this period of study came to fruition in the masterpiece of his Dutch period, The Potato Eaters

In the summer of that year, he made a large number of drawings of the peasants working in the fields. The supply of models dried up, however, when the local priest forbade his parishioners to pose for the vicar's son. He turned to painting landscape instead, inspired in part by a visit to recently opened Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

I feel - a failure. That's it as far as I'm concerned - I feel that this is the destiny that I accept, that will never change. ”

He nevertheless continued working hard during his two months in Auvers, producing dozens of paintings and drawings. On 27 July 1890, Vincent van Gogh was shot in the stomach, and passed away in the early morning of 29 July 1890 in his room at the Auberge Ravoux in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise. Although official history maintains that Van Gogh committed suicide, the latest research reveals that Van Gogh's death might be caused by an accident.

Theo, who had stored the bulk of Vincent's work in Paris, died six months later. His widow, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger (1862 - 1925), returned to Holland with the collection, and dedicated herself to getting her brother-in-law the recognition he deserved. In 1914, with his fame assured, she published Vincent van Gogh's letters between the two brothers.

The Starry Night

Café terrace at night, vincent van gogh's letters, van gogh self portrait, the starry night over the rhone, wheatfield with crows, the night cafe, the potato eaters, the yellow house, almond blossom, the church at auvers, at eternity's gate by vincent van gogh, portrait of dr. gachet, portrait of the postman joseph roulin by vincent van gogh, self portrait with bandaged ear.

Biography Online

Vincent Van Gogh Biography

Vincent Van Gogh (1853–1890)

Vincent Van Gogh was an artist of exceptional talent. Influenced by impressionist painters of the period, he developed his own instinctive, spontaneous style. Van Gogh became one of the most celebrated artists of the twentieth century and played a key role in the development of modern art.

“What am I in the eyes of most people — a nonentity, an eccentric, or an unpleasant person — somebody who has no position in society and will never have; in short, the lowest of the low. All right, then — even if that were absolutely true, then I should one day like to show by my work what such an eccentric, such a nobody, has in his heart. That is my ambition, based less on resentment than on love in spite of everything, based more on a feeling of serenity than on passion.”

– Vincent Van Gogh (Letter to Theo, July 1882)

Short Biography Vincent Van Gogh

He was born in Groot-Zundert, a small town in Holland in March 1853. His father was a Protestant pastor and he had three uncles who were art dealers.

Despite disliking formal training, he studied art in both Brussels and Paris. His first attempts at art were not indicative of his later talent. In the beginning, he was a clumsy drawer and, when studying at one art academy, he was put back a year because of his perceived lack of ability to draw. His early pictures appear rather basic and do not show any sign of his later art. However, he worked hard and sought to improve his technique. Yet these early difficulties always stayed with Van Gogh and throughout his life, he was bothered with a sense of inadequacy. In a letter to his brother, he described his early efforts as mere ‘scribbles.’

He became absorbed in art and would prioritise it over more mundane matters. Van Gogh struggled to hold down a regular job. For example, he lost his position as an art dealer after quarrelling with a customer. He also had short-lived jobs as a supply teacher and priest. Not holding a regular job, he relied on financial help from his close brother Theo. Theo was generous to his brother throughout his life – often sending money and painting materials.

With his brothers financial backing, in 1888 Van Gogh travelled to Arles in the south of France, where he continued his painting – often outside – another feature of the impressionist movement. This was a prolific period for Van Gogh; he could paint up to five paintings per week and he enjoyed walking in the countryside and getting inspiration from nature – such as the corn harvest. He drew everything from nature, portraits of friends, everyday objects and the vast night sky.

Straw Harvest

Living in Paris (1886-88) he had been influenced by the new impressionist painters, such as Monet and Renoir, and their interest in light. However, he soon developed his own unique style of powerful, brush strokes – often using warm reds, oranges and yellows. Simple brush strokes which created strong and arresting images.

Van Gogh was driven by an inner urge to express the art he felt within. He wrote that he felt an artistic power within, which moved him to work very hard.

“Believe me, I work, I drudge, I grind all day long and I do so with pleasure, but I should get very much discouraged if I could not go on working as hard or even harder.. .I feel, Theo, that there is a power within me, and I do what I can to bring it out and free it.”

– Van Gogh, (Letter to Theo 1982)

Van Gogh lived from moment to moment and was never financially secure. He put his whole life into art and neglected other aspects of his life – such as his health, appearance and financial security. During his lifetime, he sold only one painting – ironic since now Van Gogh’s paintings are some of the most expensive in the world.

“What is true is that I have at times earned my own crust of bread, and at other times a friend has given it to me out of the goodness of his heart. I have lived whatever way I could, for better or for worse, taking things just as they came.”

– Van Gogh, Letter to Theo ( July 1880 )

Cafe Terrace at Night 1888 ( Kröller-Müller Museum)

“When I have a terrible need of — shall I say the word — religion. Then I go out and paint the stars.”

– Vincent Van Gogh

In Arles, he had a brief, if unsuccessful, period of time with the artist Gauguin. Van Gogh’s intensity and mental imbalance made him difficult to live with. At the end of the two weeks, Van Gogh approached Gauguin with a razor blade. Gauguin fled back to Paris, and Van Gogh later cut off the lower part of his ear with the blade.

This action was symptomatic of his increasing mental imbalance. He was later committed to a lunatic asylum where he would spend time on and off until his death in 1890. At the best of times, Van Gogh had an emotional intensity that flipped between madness and genius. He himself wrote:

“Sometimes moods of indescribable anguish, sometimes moments when the veil of time and fatality of circumstances seemed to be torn apart for an instant.”

Vase with 12 Sunflowers, 1888

It was during these last two years of his life that Van Gogh was at his most productive as a painter. He developed a style of painting that was quick and rapid – leaving no time for contemplation and thought. He painted with quick movements of the brush and drew increasingly avant-garde style shapes – foreshadowing modern art and its abstract style. He felt an overwhelming need and desire to paint.

“The work is an absolute necessity for me . I can’t put it off, I don’t care for anything but the work; that is to say, the pleasure in something else ceases at once and I become melancholy when I can’t go on with my work. Then I feel like a weaver who sees that his threads are tangled, and the pattern he had on the loom is gone to hell, and all his thought and exertion is lost.”

In 1890, a series of bad news affected his mental equilibrium and one day in July, whilst painting, he shot himself in the chest. He died two days later from his wound.

Yellow House

The religion of Vincent Van Gogh

Van Gogh was critical of formalised religion and was often scathing of clerics in the Christian church, but he denied he was an atheist, believing in God and love.

“That God of the clergymen, He is for me as dead as a doornail. But am I an atheist for all that? The clergymen consider me as such — be it so; but I love, and how could I feel love if I did not live, and if others did not live, and then, if we live, there is something mysterious in that.”

– Van Gogh

Van Gogh saw his painting as a spiritual pursuit. He wrote of great paintings, that the artist had hidden an aspect of God in the painting.

“Try to grasp the essence of what the great artists, the serious masters, say in their masterpieces, and you will again find God in them. One man has written or said it in a book, another in a painting.”

“I think that everything that is really good and beautiful, the inner, moral, spiritual and sublime beauty in men and their works, comes from God, and everything that is bad and evil in the works of men and in men is not from God, and God does not approve of it. But I cannot help thinking that the best way of knowing God is to love many things.”

– Vincent Van Gogh

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “Biography of Vincent Van Gogh”, Oxford, www.biographyonline.net. Published 23 May 2014. Last Updated 3 February 2020.

Van Gogh – His Life and Works

Van Gogh: His Life & Works in 500 Images at Amazon

Vincent Van Gogh – The Life

Vincent Van Gogh – The Life at Amazon

Related pages

Vincent van Gogh

- Style and Technique

- Critical Reception

- Bedroom in Arles

- Café Terrace at Night

- Portrait d'Eugene Boch

- Self-portrait with Straw Hat

Starry Night

- Starry Night Over the Rhone

- The Flowering Orchard

The Potato Eaters

Vincent Van Gogh Biography

- Vincent Willem van Gogh

- Short Name:

- Date of Birth:

- 30 Mar 1853

- Date of Death:

- 29 Jul 1890

- Figure, Landscapes, Cityscapes, Scenery

- Art Movement:

- Post-Impressionism

- Zundert, Netherlands

- Vincent Van Gogh Biography Page's Content

Introduction

- Early Years

- Middle Years

- Advanced Years

A key figure in the world of Post-impressionism Vincent Van Gogh also helped lay the foundations of modern art. A troubled man, he experienced many uncertainties and rejections in his early life, particularly where female love interests were concerned. Religion played a huge role in van Gogh´s life and many of his paintings carry religious undertones. Van Gogh did not experience great success during his lifetime, selling just one painting but after his death his work was revealed to the world and he is now regarded as one of the greatest artists that ever lived.

Vincent van Gogh Early Years

Becoming increasingly frustrated, Vincent ended his relationship with Hoomik and feeling uninspired, he moved back in with his parents to continue practicing his art. It was then that he was introduced to the paintings of Jean-Franqois Millet and he imitated Millets style a lot in his early works. Van Gogh had the desire to paint figures and in 1885 he completed The Potato Eaters which proved a success at the time. Believing he needed focused training in art techniques, van Gogh enrolled at The Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp and was impressed by the works of Rubens and various Japanese artists, and such influences would impact greatly on van Gogh's individual style. In 1886 Vincent van Gogh relocated to Paris and immersed himself in the world of Impressionism and Post-impressionism. He adopted brighter, more vibrant colors and began experimenting with his technique. He also spent time researching the styles found in the Japanese artwork he had discovered a year earlier. Paris exposed van Gogh to artists such as Gauguin, Pissarro, Monet, and Bernard. He befriended Paul Gauguin and moved to Arles in 1888 and Gauguin joined him later. Van Gogh started to paint sunflowers to decorate Gauguin's bedroom and this work of art would later become one of his most accomplished pieces, Sunflowers.

Vincent van Gogh Advanced Years

It was towards the end of 1888 that van Gogh's mental illness began to worsen and in one outburst he pursued Gauguin with a knife and threatened him. Later that day at home, Vincent cut off part of his own ear then offered it to a prostitute as a gift, and he was temporarily hospitalized. Upon returning home he found Gauguin leaving Arles, and thus his dream of setting up an art school was crushed. Van Gogh committed himself to an asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence at the end of 1888 and his paintings from his time there were brimming with activity. It was in the asylum that he painted Starry Night which became his most popular work and is one of the most influential pieces in history. Van Gogh left Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in 1890 and continued painting, producing a number of works - nearly one painting per day. Despite his creative achievements, the artist thought of his life as terribly wasted, and a personal failure. On July 27, 1890 he attempted suicide by shooting himself in the chest and died two days later from the wound, aged 37. Van Goghs dear brother Theo was devastated by his loss and died six months later. Theos widow took Vincent van Goghs works to Holland and published them, and he was an instant success. His work went on to influence Modernist art and today, Vincent van Gogh is regarded as one of history's greatest painters.

Vincent's Life, 1853-1890

Vincent van Gogh decided to become an artist at the age of 27. That decision would change his life and art history forever. Read Vincent's biography.

Biography, 1853 -1873

Young Vincent

Biography, 1873 -1881

Looking for a Direction

Biography, 1881-1883

First Steps as an Artist

Biography, 1883 - 1885

Peasant Painter

Biography, 1886 - 1888

From Dark to Light

Biography, 1888 - 1889

South of France

Biography, 1889 - 1890

Hospitalization

Biography, 1890

Vincent's Final Months

Biography, 1890 - 1973

After Vincent's Death

Find out more about the man behind the artworks in these stories

Scroll for more

- Share full article

The Great Read Feature

The Woman Who Made van Gogh

Neglected by art history for decades, Jo van Gogh-Bonger, the painter’s sister-in-law, is finally being recognized as the force who opened the world’s eyes to his genius.

Jo Bonger, at about 21. Credit... F. W. Deutmann, Zwolle. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Supported by

By Russell Shorto

- Published April 14, 2021 Updated June 15, 2023

Listen to This Article

In 1885, a 22-year-old Dutch woman named Johanna Bonger met Theo van Gogh, the younger brother of the artist, who was then making a name for himself as an art dealer in Paris. History knows Theo as the steadier of the van Gogh brothers, the archetypal emotional anchor, who selflessly managed Vincent’s erratic path through life, but he had his share of impetuosity. He asked her to marry him after only two meetings.

Jo, as she called herself, was raised in a sober, middle-class family. Her father, the editor of a shipping newspaper that reported on things like the trade in coffee and spices from the Far East, imposed a code of propriety and emotional aloofness on his children. There is a Dutch maxim, “The tallest nail gets hammered down,” that the Bonger family seems to have taken as gospel. Jo had set herself up in a safely unexciting career as an English teacher in Amsterdam. She wasn’t inclined to impulsiveness. Besides, she was already dating somebody. She said no.

But Theo persisted. He was attractive in a soulful kind of way — a thinner, paler version of his brother. Beyond that, she had a taste for culture, a desire to be in the company of artists and intellectuals, which he could certainly provide. Eventually he won her over. In 1888, a year and a half after his proposal, she agreed to marry him. After that, a new life opened up for her. It was Paris in the belle epoque: art, theater, intellectuals, the streets of their Pigalle neighborhood raucous with cafes and brothels. Theo was not just any art dealer. He was at the forefront, specializing in the breed of young artists who were defying the stony realism imposed by the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Most dealers wouldn’t touch the Impressionists, but they were Theo van Gogh’s clients and heroes. And here they came, Gauguin and Pissarro and Toulouse-Lautrec, the young men of the avant-garde, marching through her life with the exotic ferocity of zoo creatures.

Jo realized that she was in the midst of a movement, that she was witnessing a change in the direction of things. At home, too, she was feeling fully alive. On their marriage night, which she described as “blissful,” her husband thrilled her by whispering into her ear, “Wouldn’t you like to have a baby, my baby?” She was powerfully in love: with Theo, with Paris, with life.

Theo talked incessantly — of their future, and also of things like pigment and color and light, encouraging her to develop a new way of seeing. But one subject dominated. From their first meeting, he regaled Jo with accounts of his brother’s tortured genius. Their apartment was crammed with Vincent’s paintings, and new crates arrived all the time. Vincent, who spent much of his brief career in motion, in France, Belgium, England, the Netherlands, was churning out canvases at a fanatical pace, sometimes one a day — olive trees, wheat fields, peasants under a Provençal sun, yellow skies, peach blossoms, gnarled trunks, clods of soil like the tops of waves, poplar trees like tongues of flame — and shipping them to Theo in hopes he would find a market for them. Theo had little success attracting buyers, but Vincent’s works, three-dimensionally thick with their violent daubs of oil paint, became the source material for Jo’s education in modern art.

When, a little more than nine months after their wedding night, Jo gave birth to a son, she agreed to the name Theo proffered. They would call the boy Vincent.

As much as he looked up to his brother, Theo also fretted constantly about him. Vincent’s mental state had already deteriorated by the time Jo came on the scene. He had slept outside in winter to mortify his flesh, gorged on alcohol, coffee and tobacco to heighten or numb his senses, become riddled with gonorrhea, stopped bathing, let his teeth rot. He had distanced himself from artists and others who might have helped his career. Just before Christmas in 1888, while Theo and Jo were announcing their engagement, Vincent was in Arles cutting off his ear following a series of rows with his housemate Paul Gauguin.

One day a canvas arrived that showed a shift in style. Vincent had been fascinated by the night sky in Arles. He tried to put it into words for Theo: “In the blue depth the stars were sparkling, greenish, yellow, white, pink, more brilliant, more emeralds, lapis lazuli, rubies, sapphires.” He became fixated on the idea of painting such a sky. He read Walt Whitman, whose work was especially popular in France, and interpreted the poet as equating “the great starry firmament” with “God and eternity.”

Vincent sent the finished painting to Theo and Jo with a note explaining that it was an “exaggeration.” “The Starry Night” continued his progression away from realism; the brush strokes were like troughs made by someone who was digging for something deeper. Theo found it disturbing — he could sense his brother drifting away, and he knew buyers weren’t likely to understand it. He wrote back: “I consider that you’re strongest when you’re doing real things.” But he enclosed another 150 francs for expenses.

Then, in the spring of 1890, news: Vincent was coming to Paris. Jo expected an enfeebled mental patient. Instead, she was confronted by the physical embodiment of the spirit that animated the canvases that covered their walls. “Before me was a sturdy, broad-shouldered man with a healthy color, a cheerful look in his eyes and something very resolute in his appearance,” she wrote in her journal. “ ‘He looks much stronger than Theo,’ was my first thought.” He charged out into the arrondissement to buy olives he loved and came back insisting that they taste them. He stood before the canvases he had sent and studied each with great intensity. Theo led him to the room where the baby lay sleeping, and Jo watched as the brothers gazed into the crib. “They both had tears in their eyes,” she wrote.

What happened next was like two blows of a hammer. Theo had arranged for Vincent to stay in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise to the north of Paris, in the care of Dr. Paul Gachet, whose homeopathic approach he hoped would help his brother’s condition. Weeks later came news that Vincent had shot himself (some biographers dispute the notion that his wound was self-inflicted). Theo arrived in the village in time to watch his brother die. Theo was devastated. He had supported his brother financially and emotionally through his brief, 10-year career, an effort to produce, as Vincent once wrote him, “something serious, something fresh — something with soul in it,” art that would reveal nothing less than “what there is in the heart of ... a nobody.” Less than three months after Vincent’s death, Theo suffered a complete physical collapse, the latter stages of syphilis he had contracted from earlier visits to brothels. He began hallucinating. His agony was tremendous and ghoulish. He died in January 1891.

Twenty-one months after her marriage, Jo was alone, stunned at the fecund dose of life she had just experienced, and at what was left to her from that life: approximately 400 paintings and several hundred drawings by her brother-in-law.

The brothers’ dying so young, Vincent at 37 and Theo at 33, and without the artist having achieved renown — Theo had managed to sell only a few of his paintings — would seem to have ensured that Vincent van Gogh’s work would subsist eternally in a netherworld of obscurity. Instead, his name, art and story merged to form the basis of an industry that stormed the globe, arguably surpassing the fame of any other artist in history. That happened in large part thanks to Jo van Gogh-Bonger. She was small in stature and riddled with self-doubt, had no background in art or business and faced an art world that was a thoroughly male preserve. Her full story has only recently been uncovered. It is only now that we know how van Gogh became van Gogh.

Long before Covid-19, Hans Luijten was in the habit of likening Vincent van Gogh to a virus. “If that virus comes into your life, it never goes away,” he said in his bright, modern Amsterdam apartment when we first spoke in April 2020, and added with a note of warning in his voice: “There’s no vaccine for it.” Luijten is 60, slim, with wire-rimmed glasses, floating tufts of gray hair and a strong penchant for American roots music: gospel, Dolly Parton, Justin Townes Earle. He was born in the southern part of the Netherlands, near the Belgian border. Both his parents made shoes for a living — his father in a factory, his mother with a sewing machine in their home — which gave him a respect for hard work and an eye for footwear: “I can’t meet a person without looking down at the feet.”

Despite the fact that there wasn’t a single book in the family house, his parents encouraged Luijten and his brother to follow their highbrow dreams, which turned out to parallel each other. Ger Luijten, five years Hans’s senior, studied art history and is now director of Fondation Custodia, an art museum in Paris. Hans majored in Dutch literature and minored in art history. After getting his doctorate, he heard that the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam wanted to develop a new critical edition of the 902 letters in the Vincent van Gogh correspondence, including those that he and Theo exchanged. In 1994 he was hired as a researcher and spent the next 15 years on that work.

In the process, Luijten developed a particular affinity for the artist. He can speak fluently about the paintings, but it’s in Vincent’s letters that he found another layer of insight. “He worked them very carefully. If you read the published letters, he might say, ‘The deep gray sky. ... ’ But if you look at the handwritten letter, you see he added ‘gray’ and then ‘deep.’ Like he was adding brush strokes. You can see in both his art and writing that he looked at the world as if everything was alive and aware. He treated a tree the same as a human being.”

Luijten is a dogged researcher, the kind who will hunt down slips of paper moldering in archives from Paris to New York, who derives meaning not just from what words in a document say but also from how they are written: “You can see emotion in Van Gogh’s handwriting: doubt, anger. I could tell when he had been drinking, because he started with huge letters, and they would become smaller and smaller as he got to the bottom of the page.”

The end result of this exhaustive research project, which went on far longer than Vincent’s career did, is “Vincent van Gogh: The Letters.” It runs to six volumes and more than 2,000 pages and was published in 2009. An online edition features the original Dutch or French together with an English translation, annotations, facsimiles of the original letters and images of artworks discussed. Leo Jansen, who toiled alongside Luijten for all of those 15 years and who now works at the Huygens Institute for the History of the Netherlands, told me that as they neared the end of the van Gogh project, he sensed that Luijten was beginning to formulate a new idea. “I think Hans realized that, while we were at last delivering Vincent’s letters, that project was only just a start, because Vincent wasn’t even known at the end of his life.”

Which raised a question that had never been completely answered: How exactly did the tortured genius, who alienated dealers and otherwise thwarted his own ambition time and again during his career, become a star? And not just a star, but one of the most beloved figures in the history of art?

Jo van Gogh-Bonger was previously known to have played a role in building the painter’s reputation, but that role was thought to have been modest — a presumption seemingly based on a combination of sexism and common sense, since she had no background in the art business. There were intriguing indications for those interested enough to look. In 2003, the Dutch writer Bas Heijne found himself in the Van Gogh Museum’s library and stumbled across some letters, which prompted him to write a play about Jo. “I just thought, This woman’s life is a great story,” he says. Luijten likewise told me that the letters between the brothers, and those exchanged with other artists and dealers, were littered with clues. He searched the museum’s library and archives and found photographs and account books that contained more hints. He corresponded with archives in France, Denmark and the United States. He began to formulate a thesis: “I started to see that she was the spider in the web. She had a strategy.”

There was another source, a potential holy grail, which he believed might advance his thesis but to which researchers had been denied access. Luijten knew Jo had kept a diary. His interest was piqued in part by the very fact that he hadn’t been able to read it — the van Gogh family had kept it under lock and key since her death in 1925. “I don’t think they were unwilling to acknowledge her role,” Luijten told me. “I think it was out of modesty.” Jo’s son, Vincent, didn’t want the world to know of his mother’s later relationship with another Dutch painter, didn’t want her privacy to be violated. The diary remained under embargo until, in 2009, Luijten asked Jo’s grandson, Johan van Gogh, if he could see it, and Johan granted his wish. ( Jo’s diaries and other materials are now available via the Van Gogh Museum’s website and library.)

The very first entry in the diary — which turned out to be a collection of simple lined notebooks of the kind used by schoolchildren — intrigued Luijten. Jo started it when she was 17, five years before she met Theo. A young woman of that era could look forward to only very narrow options in life, yet here she wrote, “I would think it dreadful to have to say at the end of my life, ‘I’ve actually lived for nothing, I have achieved nothing great or noble.’” “That, to me, was actually very exciting,” Luijten says. It was a clue: She was not content to follow her family’s maxim after all.

In 2009 Luijten began writing a biography of Jo, working in an office in a former schoolhouse opposite the greensward of Amsterdam’s Museum Square. It took him 10 years. In all, he has devoted 25 years, his entire career, to the lives of these three people. The book, “Alles voor Vincent” (“All for Vincent”), was published in 2019. Because it’s still available only in Dutch, it is just beginning to percolate into the world of art scholarship. “It’s massively important,” says Steven Naifeh, co-author of the best-selling 2011 biography “Van Gogh: The Life” and author of the forthcoming “Van Gogh and the Artists He Loved.” “It shows that without Jo there would have been no van Gogh.”

Art historians say Luijten’s biography is a major step in what will be an ongoing reappraisal — not only of the source of van Gogh’s fame but also of the modern notion of what an artist is. For that, too, is something Jo helped to invent.

Jo was at a loss over what to do with herself after Theo died. When a friend from the genteel Dutch village of Bussum suggested she come there and open a boardinghouse, it seemed soothing. She would be back in her home country yet at a comfortable distance from her family, which suited her, because she valued her independence. Bussum, for all its leafy sedateness, had a lively cultural scene. And having income from guests would be important — she would be able to provide for herself and her child.

Before leaving Paris, she corresponded with the artist Émile Bernard, one of the few painters with whom Vincent had had a relationship that was both close and free of discord, to see if he might be able to arrange an exhibition in Paris of her late brother-in-law’s paintings. Bernard urged her to leave Vincent’s canvases in Paris, reasoning that the French capital was a better base from which to sell them. There was sense in this. While Vincent had not generated enough of a following to warrant a one-man show, he had had paintings exhibited in a few group shows just before his death. Perhaps, over time, Bernard would be able to sell his work.

Had that happened, Vincent might have developed some renown. He might have become, say, an Émile Bernard. But Jo’s instincts told her to keep the paintings with her. She declined his offer. This was remarkable in itself, because time and again her diary entries show her to be riddled with insecurities and uncertainty about how to proceed in life: “I’m very bad — ugly as I am, I’m still often vain”; “My outlook on life is utterly and completely wrong at present”; “Life is so difficult and so full of sadness around me and I have so little courage!”

Over the next weeks, dressed in mourning, she settled into her new home. She unpacked linens and silverware, met her neighbors and prepared the house for guests, all the while caring for little Vincent. She seems to have spent the greatest amount of her settling-in time — months, in fact — deciding precisely where to hang her brother-in-law’s paintings. Eventually, virtually every inch of wall space was covered with them. “The Potato Eaters,” the large, mostly brown study of peasants at a humble meal that scholars consider Vincent’s first masterpiece, was hung above the fireplace. She festooned her bedroom with three canvases depicting orchards in vibrant bloom. One of her guests later remarked that “the whole house was filled with Vincents.”

Once all was more or less the way she wanted it, she picked up one of the lined notebooks and returned to the diary she began in her teens. She set it aside the moment she started her life with Theo; her last entry, from almost exactly three years before, began, “On Thursday morning I go to Paris!” During the whole mad period that followed, she was too busy to keep a journal, too swept up in another life. Now she was back. “It’s all nothing but a dream!” she wrote from her guesthouse. “What lies behind me — my short, blissful marital happiness — that, too, has been a dream! For a year and a half I was the happiest woman on Earth.”

Then, matter-of-factly, she identified the two responsibilities that Theo had given her. “As well as the child,” she wrote, “he has left me another task — Vincent’s work — getting it seen and appreciated as much as possible.”

Having no training in how to achieve this, she began with what was at hand. In addition to Vincent’s paintings, she had inherited the enormous trove of letters that the brothers had exchanged. In Bussum, in the evenings, with her guests taken care of and the baby asleep, she pored over them. Nearly all, it turned out, were from Vincent — her husband had carefully kept Vincent’s letters, but Vincent hadn’t been so fastidious with the ones his brother had sent him. Details of the artist’s daily life and tribulations — his insomnia, his poverty, his self-doubt — were mixed with accounts of paintings he was working on, techniques he experimented with, what he was reading, descriptions of paintings by other artists he drew inspiration from. He often felt the need to put into words what he was trying to achieve with color: “Town violet, star yellow, sky blue-green; the wheat fields have all the tones: old gold, copper, green gold, red gold, yellow gold, green, red and yellow bronze.” Repeatedly he sought to explain his objective in capturing what he was looking at: “I tried to reconstruct the thing as it may have been by simplifying and accentuating the proud, unchanging nature of the pines and the cedar bushes against the blue.” He described his harrowing mental breakdowns and his fear of future collapses — that “a more violent crisis may destroy my ability to paint forever,” and his notion that, should he experience another episode, he could “go into an asylum or even to the town prison, where there’s usually an isolation cell.”

She did a lot of other reading as well, undertaking what amounted to a self-guided course in art criticism. She read the Belgian journal L’Art Moderne, which advocated the idea that art should serve progressive political causes, and took notes. She read a book of criticism by the Irish novelist George Moore, jotting down a quote from it that seemed pertinent: “The lot of critics is to be remembered by what they failed to understand.” As if to steel herself for her task ahead, she also read a biography of one of her heroes, Mary Ann Evans, the English protofeminist and social critic who wrote novels under the pen name George Eliot. She described Evans in her diary as “that great, courageous, intelligent woman whom I’ve loved and revered almost since childhood” and noted that “remembering her is always an incentive to be better.”