Online Courses and Casebooks

Online courses.

These online courses are for lawyers looking to do a deep dive into a particular area, and for anyone looking to learn about how law works in practice. Offered by Harvard Law School in collaboration with Harvard’s Vice Provost for Advances in Learning and edX, these courses are part of our ongoing commitment to lifelong learning.

Contract Law: From Trust to Promise to Contract

Learn about contracts in this online course from Harvard Law Professor Charles Fried, one of the world's leading authorities on contract law.

Financial Analysis and Valuation for Lawyers

Taught by Harvard Law School faculty, this Harvard Online course is designed to help you navigate your organization's or client’s financial goals while increasing profitability and minimizing risks.

Bioethics: The Law, Medicine, and Ethics of Reproductive Technologies and Genetics

An overview of the legal, medical, and ethical questions around reproduction and human genetics and how to apply legal reasoning to these questions.

Justice Today: Money, Markets, and Morals

Led by award-winning Harvard Professor Michael J. Sandel, this course will take a deep dive into various “needs” and whether they abuse market mechanisms.

Introduction to American Civics

Presented by Zero-L, this is HLS's short introduction to American Law and Civics.

The course explores the current law of copyright; the impact of that law on art, entertainment, and industry; and the ongoing debates concerning how the law should be reformed.

A networked course on patent law hosted jointly by Harvard Law School, the Berkman Klein Center on Internet and Society, and the HarvardX Distance-Learning Initiative.

HLS Executive Education Online Programs

Computer science for lawyers.

Computer Science for Lawyers will equip you with a richer appreciation of the legal ramifications of clients’ technological decisions and policies.

International Finance: Policy, Regulation, and Transactions

International Finance will give participants a framework for thinking about the policy issues that will shape the financial system of the 21st century.

Additional Online Resources

Constitutional rights in black and white.

A video casebook about the legal decisions that define and govern our constitutional rights. Each video tells the story of an important Supreme Court case, and then shows you how to read the case yourself.

Open Casebook

The case studies.

This program publishes and distributes experimental materials developed by HLS faculty for HLS courses.

Looking for more options?

Additional course offerings are available through our Executive Education and Program on Negotiation.

Executive Education Programs

Program on negotiation.

- Find a Lawyer

- Ask a Lawyer

- Research the Law

- Law Schools

- Laws & Regs

- Newsletters

- Justia Connect

- Pro Membership

- Basic Membership

- Justia Lawyer Directory

- Platinum Placements

- Gold Placements

- Justia Elevate

- Justia Amplify

- PPC Management

- Google Business Profile

- Social Media

- Justia Onward Blog

US Case Law

The United States Supreme Court is the highest court in the United States. Lower courts on the federal level include the US Courts of Appeals, US District Courts, the US Court of Claims, and the US Court of International Trade and US Bankruptcy Courts. Federal courts hear cases involving matters related to the United States Constitution, other federal laws and regulations, and certain matters that involve parties from different states or countries and large sums of money in dispute.

Each state has its own judicial system that includes trial and appellate courts. The highest court in each state is often referred to as the “supreme” court, although there are some exceptions to this rule, for example, the New York Court of Appeals or the Maryland Court of Appeals. State courts generally hear cases involving state constitutional matters, state law and regulations, although state courts may also generally hear cases involving federal laws. States also usually have courts that handle only a specific subset of legal matters, such as family law and probate.

Case law, also known as precedent or common law, is the body of prior judicial decisions that guide judges deciding issues before them. Depending on the relationship between the deciding court and the precedent, case law may be binding or merely persuasive. For example, a decision by the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit is binding on all federal district courts within the Fifth Circuit, but a court sitting in California (whether a federal or state court) is not strictly bound to follow the Fifth Circuit’s prior decision. Similarly, a decision by one district court in New York is not binding on another district court, but the original court’s reasoning might help guide the second court in reaching its decision.

Decisions by the US Supreme Court are binding on all federal and state courts.

US Federal Courts

Reported opinions from the us federal courts of appeals.

- Federal Reporter, 2nd Series (F.2d) (1924-1993)

- Federal Reporter, 3rd Series (F.3d) (1993-present)

Opinions From the US Federal Courts of Appeals

- US Court of Appeals for the First Circuit

- US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

- US Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

- US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

- US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

- US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

- US Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit

- US Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit

- US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

- US Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

- US Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

- US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit

- US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

- US Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces

- US Court of International Trade

- US Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review

- Bankruptcy Reporter (B.R.) (1980-present)

- Federal Reporter, 2nd Series (F.2d) (1924-1932)

- Federal Supplement (F. Supp.) (1933-1998)

- Federal Supplement, 2nd Series (F. Supp. 2d) (1998-present)

- Connecticut

- District of Columbia

- Massachusetts

- Mississippi

- New Hampshire

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- West Virginia

- US District Court for the District of Guam

- US District Court for the District of Puerto Rico

- US District Court for the District of the Northern Mariana Islands

- US District Court for the District of the US Virgin Islands

- Emergency Court of Appeals (1942-1974)

- US Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims

- US Court of Claims (1855-1982)

- US Court of Customs and Patent Appeals (1909-1982)

- US Court of Federal Claims

- US Tax Court

State Courts

Foreign and international courts.

- Australia Courts

- Canada Courts

- Israel Courts

- United Kingdom Courts

- International Courts

- Bankruptcy Lawyers

- Business Lawyers

- Criminal Lawyers

- Employment Lawyers

- Estate Planning Lawyers

- Family Lawyers

- Personal Injury Lawyers

- Estate Planning

- Personal Injury

- Business Formation

- Business Operations

- Intellectual Property

- International Trade

- Real Estate

- Financial Aid

- Course Outlines

- Law Journals

- US Constitution

- Regulations

- Supreme Court

- Circuit Courts

- District Courts

- Dockets & Filings

- State Constitutions

- State Codes

- State Case Law

- Legal Blogs

- Business Forms

- Product Recalls

- Justia Connect Membership

- Justia Premium Placements

- Justia Elevate (SEO, Websites)

- Justia Amplify (PPC, GBP)

- Testimonials

Library electronic resources outage May 29th and 30th

Between 9:00 PM EST on Saturday, May 29th and 9:00 PM EST on Sunday, May 30th users will not be able to access resources through the Law Library’s Catalog, the Law Library’s Database List, the Law Library’s Frequently Used Databases List, or the Law Library’s Research Guides. Users can still access databases that require an individual user account (ex. Westlaw, LexisNexis, and Bloomberg Law), or databases listed on the Main Library’s A-Z Database List.

- Georgetown Law Library

- Research Process

Case Law Research Guide

Introduction.

- Print Case Reporters

- Online Resources for Cases

- Finding Cases: Digests, Headnotes, and Key Numbers

- Finding Cases: Terms & Connectors Searching

Key to Icons

- Georgetown only

- On Bloomberg

- More Info (hover)

- Preeminent Treatise

Every law student and practicing attorney must be able to find, read, analyze, and interpret case law. Under the common law principles of stare decisis, a court must follow the decisions in previous cases on the same legal topic. Therefore, finding cases is essential to finding out what the law is on a particular issue.

This guide will show you how to read a case citation and will set out the sources, both print and online, for finding cases. This guide also covers how to use digests, headnotes, and key numbers to find case law, as well as how to find cases through terms and connectors searching.

To find cases using secondary sources, such as legal encyclopedias or legal treatises, see our Secondary Sources Research Guide . For additional strategies to find cases, like using statutory annotations or citators, see our Case Law Research Tutorial . Our tutorial also covers how to update cases using citators (Lexis’ Shepard’s tool and Westlaw’s KeyCite).

Basic Case Citation

A case citation is a reference to where a case (also called a decision or an opinion ) is printed in a book. The citation can also be used to retrieve cases from Westlaw and Lexis . A case citation consists of a volume number, an abbreviation of the title of the book or other item, and a page number.

The precise format of a case citation depends on a number of factors, including the jurisdiction, court, and type of case. You should review the rest of this section on citing cases (and the relevant rules in The Bluebook ) before trying to format a case citation for the first time. See our Bluebook Guide for more information.

The basic format of a case citation is as follows:

Parallel Citations

When the same case is printed in different books, citations to more than one book may be given. These additional citations are known as parallel citations .

Example: 265 U.S. 274, 68 L. Ed. 1016, 44 S. Ct. 565.

This means that the case you would find at page 565 of volume 44 of the Supreme Court Reporter (published by West) will be the same case you find on page 1016 of volume 68 of Lawyers' Edition (published by Lexis), and both will be the same as the opinion you find in the official government version, United States Reports . Although the text of the opinion will be identical, the added editorial material will differ with each publisher.

Williams Library Reference

Reference Desk : Atrium, 2nd (Main) Floor (202) 662-9140 Request a Research Consultation

Case law research tutorial.

Update History

Revised 4/22 (CMC) Updated 10/22 (MK) Links 07/2023 (VL)

- Next: Print Case Reporters >>

- © Georgetown University Law Library. These guides may be used for educational purposes, as long as proper credit is given. These guides may not be sold. Any comments, suggestions, or requests to republish or adapt a guide should be submitted using the Research Guides Comments form . Proper credit includes the statement: Written by, or adapted from, Georgetown Law Library (current as of .....).

- Last Updated: Feb 29, 2024 1:03 PM

- URL: https://guides.ll.georgetown.edu/cases

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

- 26 Mar 2024

- Cold Call Podcast

How Do Great Leaders Overcome Adversity?

In the spring of 2021, Raymond Jefferson (MBA 2000) applied for a job in President Joseph Biden’s administration. Ten years earlier, false allegations were used to force him to resign from his prior US government position as assistant secretary of labor for veterans’ employment and training in the Department of Labor. Two employees had accused him of ethical violations in hiring and procurement decisions, including pressuring subordinates into extending contracts to his alleged personal associates. The Deputy Secretary of Labor gave Jefferson four hours to resign or be terminated. Jefferson filed a federal lawsuit against the US government to clear his name, which he pursued for eight years at the expense of his entire life savings. Why, after such a traumatic and debilitating experience, would Jefferson want to pursue a career in government again? Harvard Business School Senior Lecturer Anthony Mayo explores Jefferson’s personal and professional journey from upstate New York to West Point to the Obama administration, how he faced adversity at several junctures in his life, and how resilience and vulnerability shaped his leadership style in the case, "Raymond Jefferson: Trial by Fire."

- 27 Feb 2024

- Research & Ideas

Why Companies Should Share Their DEI Data (Even When It’s Unflattering)

Companies that make their workforce demographics public earn consumer goodwill, even if the numbers show limited progress on diversity, says research by Ryan Buell, Maya Balakrishnan, and Jimin Nam. How can brands make transparency a differentiator?

- 22 Feb 2024

How to Make AI 'Forget' All the Private Data It Shouldn't Have

When companies use machine learning models, they may run the risk of inadvertently sharing sensitive and private data. Seth Neel explains why it’s important to understand how to wipe AI’s spongelike memory clean.

.jpg)

- 10 Oct 2023

In Empowering Black Voters, Did a Landmark Law Stir White Angst?

The Voting Rights Act dramatically increased Black participation in US elections—until worried white Americans mobilized in response. Research by Marco Tabellini illustrates the power of a political backlash.

- 26 Sep 2023

The PGA Tour and LIV Golf Merger: Competition vs. Cooperation

On June 9, 2022, the first LIV Golf event teed off outside of London. The new tour offered players larger prizes, more flexibility, and ambitions to attract new fans to the sport. Immediately following the official start of that tournament, the PGA Tour announced that all 17 PGA Tour players participating in the LIV Golf event were suspended and ineligible to compete in PGA Tour events. Tensions between the two golf entities continued to rise, as more players “defected” to LIV. Eventually LIV Golf filed an antitrust lawsuit accusing the PGA Tour of anticompetitive practices, and the Department of Justice launched an investigation. Then, in a dramatic turn of events, LIV Golf and the PGA Tour announced that they were merging. Harvard Business School assistant professor Alexander MacKay discusses the competitive, antitrust, and regulatory issues at stake and whether or not the PGA Tour took the right actions in response to LIV Golf’s entry in his case, “LIV Golf.”

- 06 Jun 2023

The Opioid Crisis, CEO Pay, and Shareholder Activism

In 2020, AmerisourceBergen Corporation, a Fortune 50 company in the drug distribution industry, agreed to settle thousands of lawsuits filed nationwide against the company for its opioid distribution practices, which critics alleged had contributed to the opioid crisis in the US. The $6.6 billion global settlement caused a net loss larger than the cumulative net income earned during the tenure of the company’s CEO, which began in 2011. In addition, AmerisourceBergen’s legal and financial troubles were accompanied by shareholder demands aimed at driving corporate governance changes in companies in the opioid supply chain. Determined to hold the company’s leadership accountable, the shareholders launched a campaign in early 2021 to reject the pay packages of executives. Should the board reduce the executives’ pay, as of means of improving accountability? Or does punishing the AmerisourceBergen executives for paying the settlement ignore the larger issue of a business’s responsibility to society? Harvard Business School professor Suraj Srinivasan discusses executive compensation and shareholder activism in the context of the US opioid crisis in his case, “The Opioid Settlement and Controversy Over CEO Pay at AmerisourceBergen.”

- 17 Jan 2023

Good Companies Commit Crimes, But Great Leaders Can Prevent Them

It's time for leaders to go beyond "check the box" compliance programs. Through corporate cases involving Walmart, Wells Fargo, and others, Eugene Soltes explores the thorny legal issues executives today must navigate in his book Corporate Criminal Investigations and Prosecutions.

- 29 Nov 2022

How Will Gamers and Investors Respond to Microsoft’s Acquisition of Activision Blizzard?

In January 2022, Microsoft announced its acquisition of the video game company Activision Blizzard for $68.7 billion. The deal would make Microsoft the world’s third largest video game company, but it also exposes the company to several risks. First, the all-cash deal would require Microsoft to use a large portion of its cash reserves. Second, the acquisition was announced as Activision Blizzard faced gender pay disparity and sexual harassment allegations. That opened Microsoft up to potential reputational damage, employee turnover, and lost sales. Do the potential benefits of the acquisition outweigh the risks for Microsoft and its shareholders? Harvard Business School associate professor Joseph Pacelli discusses the ongoing controversies around the merger and how gamers and investors have responded in the case, “Call of Fiduciary Duty: Microsoft Acquires Activision Blizzard.”

- 28 Apr 2022

Can You Buy Creativity in the Gig Economy?

It's possible, but creators need more of a stake. A study by Feng Zhu of 10,000 novels in the Chinese e-book market reveals how tying pay to performance can lead to new ideas.

- 04 Jan 2022

- What Do You Think?

Firing McDonald’s Easterbrook: What Could the Board Have Done Differently?

Letting a senior leader go is one of the biggest—and most fraught—decisions for a corporate board. Consider the recent CEO scandal and legal wrangling at McDonald's, says James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 20 Sep 2021

How Much Is Freedom Worth? For Gig Workers, a Lot.

In the booming gig economy, does the ability to set your schedule outweigh having sick leave and overtime? Felix Oberholzer-Gee and Laura Katsnelson turn to DoorDash drivers to find out. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 17 Sep 2021

The Trial of Elizabeth Holmes: Visionary, Criminal, or Both?

Eugene Soltes explains why the fraud case against the Theranos cofounder isn't as simple as it seems, and why a conviction probably wouldn't deter unethical behavior from others. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 23 Aug 2021

Why White-Collar Crime Spiked in America After 9/11

The FBI shifted agents and other budget resources toward fighting terrorism in certain parts of the country, and financial fraud and insider trading ran rampant, according to research by Trung Nguyen. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 23 Feb 2021

Examining Race and Mass Incarceration in the United States

The late 20th century saw dramatic growth in incarceration rates in the United States. Of the more than 2.3 million people in US prisons, jails, and detention centers in 2020, 60 percent were Black or Latinx. Harvard Business School assistant professor Reshmaan Hussam probes the assumptions underlying the current prison system, with its huge racial disparities, and considers what could be done to address the crisis of the American criminal justice system in her case, “Race and Mass Incarceration in the United States.” Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 19 Oct 2020

- Working Paper Summaries

Bankruptcy and the COVID-19 Crisis

Analyzing the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on bankruptcy filing rates in the United States, this study finds that large businesses, small businesses, and consumers experience very different effects of the crisis.

- 12 Aug 2020

Why Investors Often Lose When They Sue Their Financial Adviser

Forty percent of American investors rely on financial advisers, but the COVID-19 market rollercoaster may have highlighted a weakness when disputes arise. The system favors the financial industry, says Mark Egan. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 26 Jun 2020

Weak Credit Covenants

Prior to the 2020 pandemic, the leveraged loan market experienced an unprecedented boom, which came hand in hand with significant changes in contracting terms. This study presents large-sample evidence of what constitutes contractual weakness from the creditors’ perspective.

- 23 Mar 2020

Product Disasters Can Be Fertile Ground for Innovation

Rather than chilling innovation, product accidents may provide companies an unexpected opportunity to develop new technologies desired by consumers, according to Hong Luo and Alberto Galasso. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 01 Nov 2019

Should Non-Compete Clauses Be Abolished?

SUMMING UP: Non-compete clauses need to be rewritten, especially when they are applied to lower-income workers, respond James Heskett's readers. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 28 May 2019

Investor Lawsuits Against Auditors Are Falling, and That's Bad News for Capital Markets

It's becoming more difficult for investors to sue corporate auditors. The result? A weakening of trust in US capital markets, says Suraj Srinivasan. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- Discussion Forum

Why and How: Using the Case Study Method in the Law Classroom

Post by: Jackie Kim and Lisa Brem

Why should legal educators use case studies and other experiential teaching methods, such as role plays and simulations, in their classes? Hasn’t the Langdell method served legal education well these last 140 years? Certainly creating and using experiential materials requires a different set of skills from faculty, elicits a different response and level of engagement from students, and poses barriers to implementation. The ABA’s LEAPS Project [i] has a comprehensive list of objections to practical problem solving in the classroom: materials are time consuming and expensive to create and deploy; addition of a case study or simulation to a syllabus inherently displaces other material; and there are few incentives from law school leaders to introduce this type of teaching.

Yet, the argument promoting experiential materials and techniques is strong. The 2007 Carnegie Report [ii] recommended integrating lawyering skills practice into the curriculum alongside doctrinal courses, and the ABA added simulation courses to the list of practical experiences that can and should be offered by law schools in its 2015 Guidance Memo [iii] .

In a 2007 Vanderbilt Law Review article [iv] , HLS Dean Martha Minow and Professor Todd D. Rakoff argued that Langdell’s approach to teaching students using appellate cases does not do enough to prepare law students for real-world problems: “The fact is, Langdell’s case method is good for some things, but not good for others. We are not talking about fancy goals here; we are talking about teaching students ‘how to think like a lawyer.’”

But does the case study method result in a higher degree of student learning? While we have not yet seen a study on the efficacy of the case study method vs. the Langdell method in law schools, research [v] from political science professor Matthew Krain suggests that case studies and problem-based activities do enhance certain types of learning over other types of pedagogy. In his investigation, Krain compared the results of pre-and post-course surveys of students who participated in active learning with those who received a traditional lecture course. The case studies and problems that Krain used in his non-traditional classes included: case studies in the form of popular press articles, formal case studies, films, or problem-based case exercises that required students to produce a work product.

Krain found that:

Student-centered reflection, in which students have the opportunity to discuss their understanding of the case, allows both students and instructors to connect active learning experiences back to a larger theoretical context. Case learning is particularly useful for dramatizing abstract theoretical concepts, making seemingly distant events or issues seem more “authentic” or “real,” demonstrating the connection between theory and practice, and building critical-thinking and problem-solving skills (Inoue & Krain, 2014; Krain, 2010; Kuzma & Haney, 2001; Lamy, 2007; Swimelar, 2013).

This study suggests that case-based approaches have great utility in the classroom, and they should be used more often in instances where students’ understanding of conceptual complexity or knowledge of case details is critical. Moreover, case-based exercises can be derived from a variety of different types of materials and still have great utility. If deployed selectively in the context of a more traditional classroom setting as ways to achieve particular educational objectives, case-based approaches can be useful tools in our pedagogical toolbox.

For those who might be ready to try a case study, role play, or simulation, there are resources that can help. Harvard Law School produces case studies for use throughout the legal curriculum. The HLS Case Studies program publishes these teaching materials, and makes them available to educators, academic staff, students, and trainers. Outside of Harvard Law School, links to resources for educators implementing the case study method can be found on the Case Studies Program Resources page. Listed are case study affiliates at Harvard, legal teaching and learning tools, tips for case teaching, and free case materials. Examples include the Legal Education, ADR, and Practical Problem Solving (LEAPS) Project [vi] from the American Bar Association , which provides resources for various topics on legal education, and the Teaching Post , an educators’ forum offered by the Harvard Business School where professors can seek or provide advice on case study teaching.

“… [O]ur society is full of new problems demanding new solutions, and less so than in the past are lawyers inventing those solutions. We think we can, and ought to, do better.” – Dean Martha Minow & Professor Todd Rakoff. [vii]

[i] “Overcoming Barriers to Teaching ‘Practical Problem-Solving’.” Legal Education, ADR & Practical Problem-Solving (LEAPS) Project, American Bar Association, Section of Dispute Resolution. Accessed March 16, 2017, http://leaps.uoregon.edu/content/overcoming-barriers-teaching-%E2%80%9Cpractical-problem-solving%E2%80%9D. [ii] William M. Sullivan, Anne Colby, Judith Welch Wegner, Lloyd Bond, and Lee S. Shulman, “Educating Lawyers,” The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (2007). [iii] American Bar Association, “Managing Director’s Guidance Memo,” Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar (2015). [iv] Martha Minow and Todd D. Rakoff, “A Case for Another Case Method,” Vanderbilt Law Review 60(2) (2007): 597-607. [v] Matthew Krain, “Putting the learning in case learning? The effects of case-based approaches on student knowledge, attitudes, and engagement,” Journal on Excellence in College Teaching 27(2) (2016): 131-153. [vi] “Overcoming Barriers to Teaching ‘Practical Problem-Solving’.” [vii] Minow and Rakoff.

Share this:

About Lisa Brem

- Search for:

Subscribe to Blog via Email

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive weekly notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address

Follow HLS Case Studies

Subscribe to our newsletter

Subscribe to our RSS feed

- Et Seq., The Harvard Law School Library Blog

- Harvard Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program

- HLS Berkman Center for Internet and Society

- HLS Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation

- HLS Program on the Legal Profession

- Program on Negotiation

Recent Posts

- Worker Centers & OUR Walmart: Case studies on the changing face of labor in the United States

- Robbing the Piggy Bank? Moving from mutual to stock form at Friendly Savings Bank

- The Argument for Active Learning

- Spotlight on: International and Comparative Law

- Fair Use Week: 5 Questions with Kyle Courtney

Top Posts & Pages

- Law Professors: Still Stuck in the Same Old Classroom?

- Summer Reading: Legal Education’s 9 Big Ideas, Part 3

- For-Profit Law Schools: Impacting the Future of Legal Education

- HBS Shares: How to Make Class Discussions Fair

- Law, Ethics, and Policy in Humanitarian Crises: A Student Perspective on New Simulations

- Case Development Initiative Blog Posts

- Case Study Program Blog Posts

- Experiential Learning and the Case Study Method

- Harvard Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program Blog Posts

- Legal News and Debate

- Problem Solving Workshop Blog Posts

- Program on International Law and Armed Conflict Blog Posts

- Uncategorized

Any opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Harvard University.

Product names, logos, brands, and other trademarks featured or referred to within this manuscript are the property of their respective trademark holders. These trademark holders are not affiliated with the author or any of the author's representatives. They do not sponsor or endorse the contents and materials discussed in this blog.

Outside images are used under a Creative Commons license, and do not suggest the licensor's endorsement or affiliation.

Comments are encouraged. Blog administrators will use their discretion to remove any inappropriate, uncivil, slanderous, or spam comments.

Email the site administrator at [email protected]

Legal Research

- Statutory Law

- Regulations

- Secondary sources

- Citing Legal Resources

Case Law Resources

- Caselaw Access Project The Caselaw Access Project (CAP), maintained by the Harvard Law School Library Innovation Lab, includes "all official, book-published United States case law — every volume designated as an official report of decisions by a court within the United States...[including] all state courts, federal courts, and territorial courts for American Samoa, Dakota Territory, Guam, Native American Courts, Navajo Nation, and the Northern Mariana Islands." As of the publication of this guide, CAP "currently included all volumes published through 2020 with new data releases on a rolling basis at the beginning of each year."

- CourtListener Court Listener is a free and publicly accessible online platform that provides a collection of legal resources and court documents, including court opinions and case law from various jurisdictions in the United States. It includes PACER data (the RECAP Archive), opinions, or oral argument recordings.

- FindLaw Caselaw Summaries Archive FindLaw provides a database of case law from the U.S. Supreme Court and U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeal, as well as several state supreme courts. It includes U.S. Supreme Court Opinions, U.S. Federal Appellate Court Opinions and U.S. State Supreme, Appellate and Trial Court Opinions. Search for case summaries or by jurisdiction.

- FindLaw Jurisdiction Search FindLaw provides a database of case law from the U.S. Supreme Court and U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeal, as well as several state supreme courts. It includes U.S. Supreme Court Opinions, U.S. Federal Appellate Court Opinions and U.S. State Supreme, Appellate and Trial Court Opinions. Search for case summaries or by jurisdiction.

- Google Scholar for Case Law Google Scholar offers an extensive database of state and federal cases, including U.S. Supreme Court Opinions, U.S. Federal District, Appellate, Tax, and Bankruptcy Court Opinions, U.S. State Appellate and Supreme Court Opinions, Scholarly articles, papers, and reports. To get started, select the “case law” radio button, and choose your search terms.

- Justia Justia offers cases from the U.S. Supreme Court, U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeal, and U.S. District Courts. Additionally, you may find links to many state supreme court and intermediate courts of appeal cases. Content includes U.S. Supreme Court Opinions, U.S. Federal Appellate & District Court Opinions, Selected U.S. Federal Appellate & District Court dockets and orders and U.S. State Supreme & Appellate Court Opinions.

An interdisciplinary, international, full-text database of over 18,000 sources including newspapers, journals, wire services, newsletters, company reports and SEC filings, case law, government documents, transcripts of broadcasts, and selected reference works.

- PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records) PACER is a nationwide database for accessing federal court documents, including case dockets. It covers U.S. District Courts, Bankruptcy Courts, and the U.S. Court of Appeals. Users can search for and access federal case dockets and documents for a fee.

- Ravel Law Public Case Access "This new Public Case Access site was created as a result of a collaboration between the Harvard Law School Library and Ravel Law. The company supported the library in its work to digitize 40,000 printed volumes of cases, comprised of over forty million pages of court decisions, including original materials from cases that predate the U.S. Constitution."

- The RECAP Archive Part of CourtListener, RECAP provides access to millions of PACER documents and dockets.

State Courts

- State Court Websites This page provides a list of various state court system websites by state.

- Pennsylvania Judiciary Web Portal The Pennsylvania Judiciary Web Portal provides the public with access to various aspects of court information, including appellate courts, common pleas courts and magisterial district court docket sheets; common pleas courts and magisterial district court calendars; and PAePay.

- Supreme Court of Pennsylvania Opinions

US Supreme Court

- US Reports he opinions of the Supreme Court of the United States are published officially in the United States Reports.

- US Reports through HeinOnline

- << Previous: Start

- Next: Statutory Law >>

- Last Updated: Apr 5, 2024 3:44 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cmu.edu/legal_research

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The essential cases every law student should know

Cases capture human stories, shape public debate and establish new expectations of the state. Their wider effect can reflect society's consciousness but often lead to new laws. Cases and judges' decisions are a law student's bread and butter. Here are a few you will come across:

Care for thy neighbour:

In 1932 Mrs Donoghue launched the modern law of negligence, after finding her ginger beer less than appealing. Known to generations of law students as the "snail in the bottle" case, it is best known for Lord Atkin's famous neighbour principle. In declaring we should take reasonable care to avoid harm to those we foresee can be affected, he established when we owe duties to each other. Accidents and injuries were forever to be reshaped into claims and compensation.

Foreign detainees

Known as the Belmarsh decision , there is no modern case that better sets the boundary between national security and civil liberties. Decided by a panel of nine law lords, the 2004 decision became an important milestone in judges protecting both the rule of law and human rights. In a challenge to the Labour policy of indefinitely detaining foreign terrorist suspects without charge, the majority declared the British state acted illegally and in a discriminatory way. In his powerful rejection, Lord Hoffman stated "The real threat to the life of the nation… comes not from terrorism but from laws such as these."

Spanish fisherman

Providing the legal backdrop to a decade of EU-scepticism is the 1991 case of Factortame , this case on the rights of Spanish fisherman to fish in British waters is a mainstay on any public law course. It confirmed the priority of European laws over UK acts of parliament and thus struck a blow against parliament's legal supremacy. In so doing it provoked much constitutional debate about the extent of EU legal powers - and Britain's relationship with Europe as a whole.

Officially the longest case in English legal history, this ten year David v Goliath libel battle exposed the price of justice when corporations take on individuals. The fast food giant sued green campaigners David Morris and Helen Steel for libel over a stinging pamphlet criticising the their ethical credentials. McDonalds walked away with both a win and a PR disaster. The European court of human rights later declared in 2005 that the pair, who were unfunded and were representing themselves, had been denied their right to a fair trial.

Jodie and Mary

In the year 2000 the plight of conjoined twins made front page news . The question was whether it was justified to separate and knowingly "kill" the weaker Mary in order to save her stronger sister Jodie, given both were destined for a premature death. In spite of parents favouring non-separation, doctors wanted a declaration that such an operation would be lawful. In a maze of ethical and legal conflicts, Lord Justice Ward rather hollowly declared that "this is a court of law, not a court of morals."

After admitting to sleepless nights, the judges allowed the doctors to separate. Lord Justice Brooke declared the situation as one of necessity, allowing the option of a lesser evil. The stronger twin survived and made a full recovery. The thankfully rare case, otherwise found in philosophy debates, demonstrates the relationship between law and morality, perhaps one of the first questions on a legal theory course.

Domestic abuse

A year after marital rape was declared rape in 1991, came the case of Kiranjit Ahluwalia , who had been abused for over a decade by a violent husband. She was convicted of murder after setting her husband alight as he slept. In recognising long-term domestic abuse and the possibility of a slow-burn anger that led to her snapping, the case was a cause célèbre for feminist and domestic abuse groups. Though finally the decision in the end was based on diminished responsibility, it was seen as a benchmark for tackling the gender bias in the criminal law and raising public awareness of domestic abuse. Ahluwalia's conviction was reduced to manslaughter, and she was freed.

International human rights law received a global TV audience in 1998 after former Chilean dictator General Pinochet was arrested in London. Under the rules of universal jurisdiction, he was detained following a Spanish extradition request facing charges of crimes against humanity. The law lords declared that there could be a limit to the immunity enjoyed by heads of states. Though Pinochet was never extradited, the case sent out a strong message about accountability for leaders who commit human rights abuses,before the international criminal court was established.

The case is also well known among lawyers when after the first hearing it was disclosed that that one of the ruling law lords, Lord Hoffmann, was a director of Amnesty International, a party to the cases. The entire hearing had to be repeated to show that "justice must not only be done but be seen to be done."

The internet age

Injunctions, twitter, privacy and the extra marital activities of footballers were all the rage in early 2011. Nothing struck up more attention than the application for an injunction by Ryan Giggs against the Sun. His name was widely tweeted and the situation became more farcical when MP John Hemming revealed his name in the House of Commons. The debate forced the law to react to an age of the internet and social media. The case followed a long line of celebrity court battles in the 2000's, and became another marker in the debate between balancing freedom of expression and the right to a private life.

From across the Atlantic arguably no case better demonstrates the political and social impact of judicial decisions. The landmark decision in 1973 upheld a woman's right to an abortion. Synonymous with abortion in the USA. Hundreds of thousands march on the US supreme court on the anniversary of the decision each year.

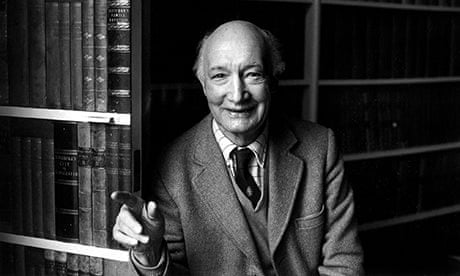

Any of Denning's cases

In our common law system, many judges leave their mark on a particular area of law. However clichéd, no judge will live longer in the memory of law students than the controversial Lord Denning. He demonstrates the power of personality in a subject that is often seen technical, dry and rule-based. In the words of Lord Irvine, "the word Denning became a byword for the law itself." Denning reminds us that all cases are eventually decided by individuals who are made up of values and personal perspectives that make them who they are. Students , you are encouraged to think, debate and learn the law in the same spirit. Good luck.

Are there any need-to-know cases missing from this list? Add them in the comments below.

- Studying law

- UK criminal justice

- International criminal justice

- Universal jurisdiction

- Injunctions

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Artificial Intelligence and the Law

Legal scholars on the potential for innovation and upheaval.

- December 5, 2023

- Tomas Weber

- Illustrations by Joan Wong | Photography by Timothy Archibald

- Fall 2023 – Issue 109

- Cover Story

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share by Email

Earlier this year, in Belgium, a young father of two ended his life after a conversation with an AI-powered chatbot. He had, apparently, been talking to the large language model regularly and had become emotionally dependent on it. When the system encouraged him to commit suicide, he did. “Without these conversations with the chatbot,” his widow told a Brussels newspaper, “my husband would still be here.”

A devastating tragedy, but one that experts predict could become a lot more common.

As the use of generative AI expands, so does the capacity of large language models to cause serious harm. Mark Lemley (BA ’88), the William H. Neukom Professor of Law, worries about a future in which AI provides advice on committing acts of terrorism, recipes for poisons or explosives, or disinformation that can ruin reputations or incite violence.

The question is who, if anybody, will be held accountable for these harms?

“We don’t have case law yet,” Lemley says. “The company that runs the AI is not doing anything deliberate. They don’t necessarily know what the AI is going to say in response to any given prompt.” So, who’s liable? “The correct answer, right now, might be nobody. And that’s something we will probably want to change.”

Generative AI is developing at a stunning speed, creating new and thorny problems in well-established legal areas, disrupting long-standing regimes of civil liability—and outpacing the necessary frameworks, both legal and regulatory, that can ensure the risks are anticipated and accounted for.

To keep up with the flood of new, large language models like ChatGPT, judges and lawmakers will need to grapple, for the first time, with a host of complex questions. For starters, how should the law govern harmful speech that is not created by human beings with rights under the First Amendment? How must criminal statutes and prosecutions change to address the role of bots in the commission of crimes? As growing numbers of people seek legal advice from chatbots, what does that mean for the regulation of legal services? With large language models capable of authoring novels and AI video generators churning out movies, how can existing copyright law be made current?

Hanging over this urgent list of questions is yet another: Are politicians, administrators, judges, and lawyers ready for the upheaval AI has triggered?

ARTIFICIAL AGENTS, CRIMINAL INTENT

Did ChatGPT defame Professor Lemley?

In 2023, when Lemley asked the chatbot GPT-4 to provide information about himself, it said he had been accused of a crime: namely, the misappropriation of trade secrets. Director of the Stanford Program in Law, Science and Technology , Lemley had done no such thing. His area of research, it seems, had caused the chatbot to hallucinate criminal offenses.

More recently, while researching a paper on AI and liability, Lemley and his team asked Google for information on how to prevent seizures. The search engine responded with a link titled “Had a seizure, now what?” and Lemley clicked. Among the answers: “put something in someone’s mouth” and “hold the person down.” Something was very wrong. Google’s algorithm, it turned out, had sourced content from a webpage explaining precisely what not to do. The error could have caused serious injury. (This advice is no longer included in search results.)

Lemley says it is not clear AI companies will be held liable for errors like these. The law, he says, needs to evolve to plug the gaps. But Lemley is also concerned about an even broader problem: how to deal with AI models that cause harm but that have impenetrable technical details locked inside a black box.

Take defamation. Establishing liability, Lemley explains, requires a plaintiff to prove mens rea: an intent to deceive. When the author of an allegedly defamatory statement is a chatbot, though, the question of intent becomes murky and will likely turn on the model’s technical details: how exactly it was trained and optimized.

To guard against possible exposure, Lemley fears, developers will make their models less transparent. Turning an AI into a black box, after all, makes it harder for plaintiffs to argue that it had the requisite “intent.” At the same time, it makes models more difficult to regulate.

How, then, should we change the law? What’s needed, says Lemley, is a legal framework that incentivizes developers to focus less on avoiding liability and more on encouraging companies to create systems that reflect our preferences. We’d like systems to be open and comprehensible, he says. We’d prefer AIs that do not lie and do not cause harm. But that doesn’t mean they should only say nice things about people simply to avoid liability. We expect them to be genuinely informative.

In light of these competing interests, judges and policymakers should take a fine-grained approach to AI cases, asking what, exactly, we should be seeking to incentivize. As a starting point, suggests Lemley, we should dump the mens rea requirement in AI defamation cases now that we’ve entered an era when dangerous content can so easily be generated by machines that lack intent.

Lemley’s point extends to AI speech that contributes to criminal conduct. Imagine, he says, a chatbot generating a list of instructions for becoming a hit man or making a deadly toxin. There is precedent for finding human beings liable for these things. But when it comes to AI, once again accountability is made difficult by the machine’s lack of intent.

“We want AI to avoid persuading people to hurt themselves, facilitating crimes, and telling falsehoods about people,” Lemley writes in “Where’s the Liability in Harmful AI Speech?” So instead of liability resting on intent, which AIs lack, Lemley suggests an AI company should be held liable for harms in cases where it was designed without taking standard actions to mitigate risk.

“It is deploying AI to help prosecutors make decisions that are not conditioned on race. Because that’s what the law requires.”

Julian Nyarko, associate professor of law, on the algorithm he developed

At the same time, Lemley worries that holding AI companies liable when ordinary humans wouldn’t be, may inappropriately discourage development of the technology. He and his co-authors argue that we need a set of best practices for safe AI. Companies that follow the best practices would be immune from suit for harms that result from their technology while companies that ignore best practices would be held responsible when their AIs are found to have contributed to a resulting harm.

HELPING TO CLOSE THE ACCESS TO JUSTICE GAP

As AI threatens to disrupt criminal law, lawyers themselves are facing major disruptions. The technology has empowered individuals who cannot find or pay an attorney to turn to AI-powered legal help. In a civil justice system awash in unmet legal need, that could be a game changer.

“It’s hard to believe,” says David Freeman Engstrom , JD ’02, Stanford’s LSVF Professor in Law and co-director of the Deborah L. Rhode Center on the Legal Profession , “but the majority of civil cases in the American legal system—that’s millions of cases each year—are debt collections, evictions, or family law matters.” Most pit a represented institutional plaintiff (a bank, landlord, or government agency) against an unrepresented individual. AI-powered legal help could profoundly shift the legal services marketplace while opening courthouse doors wider for all.

“Up until now,” says Engstrom, “my view was that AI wasn’t powerful enough to move the dial on access to justice.” That view was front and center in a book Engstrom published earlier this year, Legal Tech and the Future of Civil Justice . Then ChatGPT roared onto the scene—a “lightning-bolt moment,” as he puts it. The technology has advanced so fast that Engstrom now sees rich potential for large language models to translate back and forth between plain language and legalese, parsing an individual’s description of a problem and responding with clear legal options and actions.

“We need to make more room for new tools to serve people who currently don’t have lawyers,” says Engstrom, whose Rhode Center has worked with multiple state supreme courts on how to responsibly relax their unauthorized practice of law and related rules. As part of that work, a groundbreaking Rhode Center study offered the first rigorous evidence on legal innovation in Utah and Arizona, the first two states to implement significant reforms.

But there are signs of trouble on the horizon. This summer, a New York judge sanctioned an attorney for filing a motion that cited phantom precedents. The lawyer, it turns out, relied on ChatGPT for legal research, never imagining the chatbot might hallucinate fake law.

How worried should we be about AI-powered legal tech leading lay people—or even attorneys—astray? Margaret Hagan , JD ’13, lecturer in law, is trying to walk a fine line between techno-optimism and pessimism.

“I can see the point of view of both camps,” says Hagan, who is also the executive director of the Legal Design Lab , which is researching how AI can increase access to justice, as well as designing and evaluating new tools. “The lab tries to steer between those two viewpoints and not be guided by either optimistic anecdotes or scary stories.”

To that end, Hagan is studying how individuals are using AI tools to solve legal problems. Beginning in June, she gave volunteers fictional legal scenarios, such as receiving an eviction notice, and watched as they consulted Google Bard. “People were asking, ‘Do I have any rights if my landlord sends me a notice?’ and ‘Can I really be evicted if I pay my rent on time?’” says Hagan.

Bard “provided them with very clear and seemingly authoritative information,” she says, including correct statutes and ordinances. It also offered up imaginary case law and phone numbers of nonexistent legal aid groups.

In her policy lab class, AI for Legal Help , which began last autumn, Hagan’s students are continuing that work by interviewing members of the public about how they might use AI to help them with legal problems. As a future lawyer, Jessica Shin, JD ’25, a participant in Hagan’s class, is concerned about vulnerable people placing too much faith in these tools.

“I’m worried that if a chatbot isn’t dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s, key things can and will be missed—like statute of limitation deadlines or other procedural steps that will make or break their cases,” she says.

“Government cannot govern AI, if government doesn’t understand AI.”

Daniel Ho, William Benjamin Scott and Luna M. Scott Professor of Law

Given all this promise and peril, courts need guidance, and SLS is providing it. Engstrom was just tapped by the American Law Institute to lead a multiyear project to advise courts on “high-volume” dockets, including debt, eviction, and family cases. Technology will be a pivotal part, as will examining how courts can leverage AI. Two years ago, Engstrom and Hagan teamed up with Mark Chandler, JD ’81, former Cisco chief legal officer now at the Rhode Center, to launch the Filing Fairness Project . They’ve partnered with courts in seven states, from Alaska to Texas, to make it easier for tech providers to serve litigants using AI-based tools. Their latest collaboration will work with the Los Angeles Superior Court, the nation’s largest, to design new digital pathways that better serve court users.

CAN MACHINES PROMOTE COMPLIANCE WITH THE LAW?

The hope that AI can be harnessed to help foster fairness and efficiency extends to the work of government too. Take criminal justice. It’s supposed to be blind, but the system all too often can be discriminatory—especially when it comes to race. When deciding whether to charge or dismiss a case, a prosecutor is prohibited by the Constitution from taking a suspect’s race into account. There is real concern, though, that these decisions might be shaped by racial bias—whether implicit or explicit.

Enter AI. Julian Nyarko , associate professor of law, has developed an algorithm to mask race-related information from felony reports. He then implemented the algorithm in a district attorney’s office, erasing racially identifying details before the reports reached the prosecutor’s desk. Nyarko believes his algorithm will help ensure lawful prosecutorial decisions.

“The work uses AI tools to increase compliance with the law,” he says. “It is deploying AI to help prosecutors make decisions that are not conditioned on race. Because that’s what the law requires.”

GOVERNING AI

While the legal profession evaluates how it might integrate this new technology, the government has been catching up on how to grapple with the AI revolution. According to Daniel Ho , the William Benjamin Scott and Luna M. Scott Professor of Law and a senior fellow at Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered AI, one of the core challenges for the public sector is a dearth of expertise.

Very few specialists in AI choose to work in the public sector. According to a recent survey, less than 1 percent of recent AI PhD graduates took positions in government—compared with some 60 percent who chose industry jobs. A lack of the right people, and an ailing government digital infrastructure, means the public sector is missing the expertise to craft law and policy and effectively use these tools to improve governance. “Government cannot govern AI,” says Ho, “if government doesn’t understand AI.”

Ho, who also advises the White House as an appointed member of the National AI Advisory Committee (NAIAC), is concerned policymakers and administrators lack sufficient knowledge to separate speculative from concrete risks posed by the technology.

Evelyn Douek , a Stanford Law assistant professor, agrees. There is a lack of available information about how commonly used AI tools work—information the government could use to guide its regulatory approach, she says. The outcome? An epidemic of what Douek calls “magical thinking” on the part of the public sector about what is possible.

The information gap between the public and private sectors motivated a large research team from Stanford Law School’s Regulation, Evaluation, and Governance Lab (RegLab) to assess the feasibility of recent proposals for AI regulation. The team, which included Tino Cuéllar (MA ’96, PhD ’00), former SLS professor and president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; Colleen Honigsberg , professor of law; and Ho, concluded that one important step is for the government to collect and investigate events in which AI systems seriously malfunction or cause harm, such as with bioweapons risk.

“If you look at other complex products, like cars and pharmaceuticals, the government has a database of information that details the factors that led to accidents and harms,” says Neel Guha, JD/PhD ’24 (BA ’18), a PhD student in computer science and co-author of a forthcoming paper that explores this topic. The NAIAC formally adopted this recommendation for such a reporting system in November.

“Our full understanding of how these systems are being used and where they might fail is still in flux,” says Guha. “An adverse-event-reporting system is a necessary prerequisite for more effective governance.”

MODERNIZING GOVERNMENT

While the latest AI models demand new regulatory tools and frameworks, they also require that we rethink existing ones—a challenge when the various stakeholders often operate in separate silos.

“Policymakers might propose something that is technically impossible. Engineers might propose a technical solution that is flatly illegal.” Ho says. “What you need are people with an understanding of both dimensions.”

Last year, Ho, Christie Lawrence, JD ’24, and Isaac Cui, JD ’25, documented extensive challenges the federal government faced in implementing AI legal requirements in an article. This led Ho to testify before the U.S. Senate on a range of reforms. And this work is driving change. The landmark White House executive order on AI adopted these recommendations, and the proposed AI Leadership to Enable Accountable Deployment (AI LEAD) Act would further codify recommendations, such as the creation of a chief AI officer, agency AI governance boards, and agency strategic planning. These requirements would help ensure the government is able to properly use and govern the technology.

“If generative AI technologies continue on their present trajectory, it seems likely that they will upend many of our assumptions about a copyright system.”

Paul Goldstein, Stella W. and Ira S. Lillick Professor of Law

Ho, as faculty director of RegLab, is also building bridges with local and federal agencies to develop high-impact demonstration projects of machine learning and data science in the public sector.

The RegLab is working with the Internal Revenue Service to modernize the tax-collection system with AI. It is collaborating with the Environmental Protection Agency to develop machine-learning technology to improve environmental compliance. And during the pandemic, it partnered with Santa Clara County to improve the public health department’s wide range of pandemic response programs.

“AI has real potential to transform parts of the public sector,” says Ho. “Our demonstration projects with government agencies help to envision an affirmative view of responsible technology to serve Americans.”

In a sign of an encouraging shift, Ho has observed an increasing number of computer scientists gravitating toward public policy, eager to participate in shaping laws and policy to respond to rapidly advancing AI, as well as law students with deep interests in technology. Alumni of the RegLab have been snapped up to serve in the IRS and the U.S. Digital Service, the technical arm of the executive branch. Ho himself serves as senior advisor on responsible AI to the U.S. Department of Labor. And the law school and the RegLab are front and center in training a new generation of lawyers and technologists to shape this future.

AI GOES TO HOLLYWOOD

Swaths of books and movies have been made about humans threatened by artificial intelligence, but what happens when the technology becomes a menace to the entertainment industry itself? It’s still early days for generative AI-created novels, films, and other content, but it’s beginning to look like Hollywood has been cast in its own science fiction tale—and the law has a role to play.

“If generative AI technologies continue on their present trajectory,” says the Stella W. and Ira S. Lillick Professor of Law Paul Goldstein , “it seems likely that they will upend many of our assumptions about a copyright system.”

There are two main assumptions behind intellectual property law that AI is on track to disrupt. From feature films and video games with multimillion-dollar budgets to a book whose author took five years to complete, the presumption has been that copyright law is necessary to incentivize costly investments. Now AI has upended that logic.

“When a video game that today requires a $100 million investment can be produced by generative AI at a cost that is one or two orders of magnitude lower,” says Goldstein, “the argument for copyright as an incentive to investment will weaken significantly across popular culture.”

The second assumption, resting on the consumer side of the equation, is no more stable. Copyright, a system designed in part to protect the creators of original works, has also long been justified as maximizing consumer choice. However, in an era of AI-powered recommendation engines, individual choice becomes less and less important, and the argument will only weaken as streaming services “get a lot better at figuring out what suits your tastes and making decisions for you,” says Goldstein.

If these bedrock assumptions behind copyright are both going to be rendered “increasingly irrelevant” by AI, what then is the necessary response? Goldstein says we need to find legal frameworks that will better safeguard human authors.

“I believe that authorship and autonomy are independent values that deserve to be protected,” he says. Goldstein foresees a framework in which AI-produced works are clearly labeled as such to guarantee consumers have accurate information.

The labeling approach may have the advantage of simplicity, but on its own it is not enough. At a moment of unprecedented disruption, Goldstein argues, lawmakers should be looking for additional ways to support human creators who will find themselves competing with AIs that can generate works faster and for a fraction of the cost. The solution, he suggests, might involve looking to practices in countries that have traditionally given greater thought to supporting artists, such as those in Europe.

“There will always be an appetite for authenticity, a taste for the real thing,” Goldstein says. “How else do you explain why someone will pay $2,000 to watch Taylor Swift from a distant balcony, when they could stream the same songs in their living room for pennies?” In the case of intellectual property law, catching up with the technology may mean heeding our human impulse—and taking the necessary steps to facilitate the deeply rooted urge to make and share authentic works of art. SL

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- EJIL: Talk!

- The Podcast!

- EJIL: Live!

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish?

- About European Journal of International Law

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1 introduction, 2 research methods, 3 literature review: textbooks and discipline making, 4 reading the lines: the basic architecture of international law textbooks, 5 reading between the lines: the international legal projects of textbooks, 6 reading against the lines: what do textbooks write out of international law, 7 conclusions.

- < Previous

Textbooks as Markers and Makers of International Law: A Brazilian Case Study

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Luíza Leão Soares Pereira, Fabio Costa Morosini, Textbooks as Markers and Makers of International Law: A Brazilian Case Study, European Journal of International Law , Volume 35, Issue 1, February 2024, Pages 25–62, https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chae007

- Permissions Icon Permissions

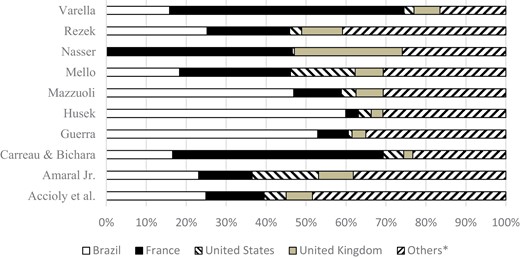

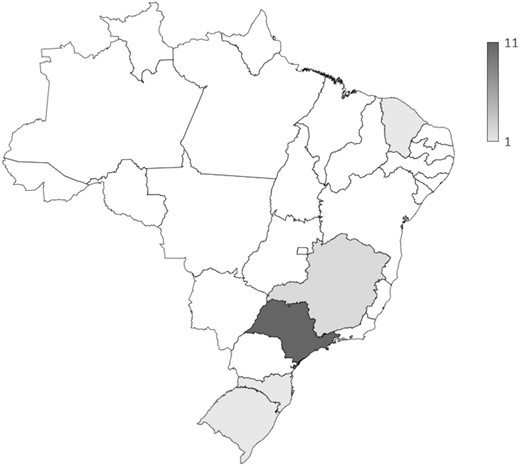

This article challenges conventional views of international law textbooks as mere instructional tools and explores them as powerful sites for shaping knowledge and the discipline. Drawing on empirical methods and critical theory, we analyse the 10 main international law textbooks used in Brazil and conduct interviews with their authors to illuminate the textbooks’ complexities and their potential for shaping the discipline and the profession. The article delves into the tension between the structure of international law as depicted in the textbooks and the agency of their authors, investigating the authors’ identities and backgrounds. Brazil serves as a compelling case study due to its numerous international law textbooks and their widespread use. Our results indicate a predominant universalist approach in Brazilian textbooks and their connection to the French international law tradition. Moreover, the study sheds light on the Brazilian ‘invisible college’ of international lawyers, revealing gender and racial disparities and institutional centralities. It also uncovers crucial omissions in the textbooks, such as the relationship of international law to colonialism, slavery, race, gender and economic inequality. Overall, this study offers a comprehensive understanding of international law as a field in Brazil and provides a valuable methodological framework for future research on textbooks’ role in shaping the discipline.

Textbooks are sites for power and discipline making, ‘engines of sociomental control that delimit the realm of the “relevant” in international law’. 1 Yet they receive limited attention as scholarship. Cast as training tools that, by virtue of their genre, do not encapsulate original insights, we tend to miss how their comprehensiveness in fact paints a broad and nuanced picture of international law and its place in world making for the book’s readership. This article aims at reading textbooks as ambitious agenda setters in their own right.

We employ empirical methods, harvesting data from the textbooks themselves and conducting semi-structured interviews with their authors, but infuse our analysis with a critical sensibility, grounded on literature on the sociology of law, 2 on knowledge production in international law, 3 on international law textbooks, 4 on semi-peripheral international lawyers, 5 on the teaching of Third World Approaches to International Law, 6 on critical and decolonial approaches to teaching international law, 7 on comparative international law 8 and on the decolonization of higher education. 9 Each of these bodies of literature comes together to help us revisit textbooks and their function beyond training materials, unveiling their analytical, political and social possibilities. Guided by this critical literature, we evaluate textbooks not only as repositories of data on how international law is taught but also as maps of the sensibilities produced and reproduced by authors and practitioners of international law.

Based on this theoretical framework, we seek to explore the tension between the structure of international law that these textbooks describe and the agency of their authors and recipients. 10 Thus, we reject the idea that authors can produce a ‘neutral’ manual or discover international law outside of the tension between structure and agency. 11 Part of uncovering this goes towards asking who is behind these texts and their respective ideologies and identities, which is part of what we do here, analysing the curricula of textbook authors and conducting interviews with them to clarify their views of international law to better understand the ways in which these imprint on the texts they produce. We seek to tackle structural questions about international law (such as whether there are substantive themes of ‘national’ interest that are repeated in the textbooks, whether there are privileged sources among their citations and what are the patterns of nationality and gender among the authors of secondary works cited) and questions about the agency of the authors of these textbooks (how do the textbooks reflect the authors’ professional histories, geographic location, academic background and positionality?).

We use Brazil as our field of analysis because, first, this is where we practise and teach international law. In addition, Brazil has an unusually large number of textbooks in the discipline that supply a rich source for analysis. This is a product of a combination of factors that include a disproportionate number of law schools per capita, 12 a long-standing tradition of teaching law using primarily textbooks 13 and an incentive to produce one’s own textbook to demonstrate prestige in the local academy. Brazilian students also often do not speak English or French as a second language, and, thus, primary materials are de facto inaccessible to them in their original form. International law textbooks, in this sense, act as literal translations of these materials, interspersed with the ideas of the authors. Finally, we propose that there is no reason why the Brazilian experience should be seen as more niche than, for instance, an analysis of textbooks from the five permanent members of the United Nations (UN) Security Council: our methodology and substantive insights are useful and easily transplantable across jurisdictions.

We propose that our focus on Brazil should not distract readers from our project’s application beyond any particular jurisdiction. Our insights, while shedding light on some aspects particular to the Brazilian experience, are a case study on the power of textbooks as markers and makers of international law. The template we sketch out here is an invitation for further research into textbooks in other locations. The following sections provide different modes of reading textbooks. The fourth section reads the lines of textbooks, examining their basic architecture and summarizing the results of our findings, 14 while the fifth section reads between the lines of textbooks by exploring the legal projects that underpin them. We conclude with the sixth section by reading against the lines and studying what is absent from Brazilian textbooks.

Overall, the focus on Brazil shows that Brazilian textbooks adopt a universalist approach and a connection to a French international law tradition. We also observe that, while some textbooks present distinctively authorial characteristics (project textbooks), others are more descriptive and technical (instrument textbooks), which we connect not only to the global trend of managerialism 15 but also to developments in the Brazilian legal landscape. In addition, we use textbooks to sketch out some characteristics of the Brazilian ‘invisible college’, 16 such as its lack of gender and racial diversity, similarities between authors’ career paths, the centrality of certain Brazilian and international institutions in Brazilian international lawyers’ legal imaginaries and the importance of key individuals in the Brazilian international legal profession. Finally, we read against the lines of these textbooks to reveal neglected areas that are particularly important in the Brazilian context – international law’s relationship to colonialism and slavery, its connection to racial and gender discrimination and economic inequality and developments in transitional justice. The results provide not only a unique window into the content of Brazilian textbooks themselves but also a complex, historically and socially situated picture of international law as a field in Brazil and a methodological framework for others seeking to use textbooks to understand the discipline anywhere.

We analyse the 10 main Brazilian textbooks currently in use: Curso de Direito Internacional Público by Alberto do Amaral Júnior; 17 Curso de Direito Internacional Público by Carlos Roberto Husek; 18 Direito Internacional by Dominique Carreau and Jahyr-Philippe Bichara; 19 Direito Internacional Público by Francisco Rezek; 20 Manual de Direito Internacional Público by Hildebrando Accioly, Geraldo Eulálio do Nascimento e Silva and Paulo Borba Casella; 21 Direito Internacional Público by Marcelo Dias Varella; 22 Direito Internacional Público by Salem Nasser; 23 Curso de Direito Internacional Público by Sidney Guerra; 24 and Curso de Direito Internacional Público by Valerio de Oliveira Mazzuoli. 25 We also chose to analyse the Curso de Direito Internacional , by Celso Duvivier de Albuquerque Mello, 26 despite the absence of new editions since 2005 due to his passing, as it is still used widely in Brazilian classrooms. There are other textbooks in circulation in Brazil, but we selected these as the best representatives of the field, based on our lived experiences as students and teachers of international law in Brazil and their widespread adoption in the Brazilian law school curriculum. 27

All textbooks analysed were written from the 2000s onwards, with two exceptions. The first, mentioned above, is the still central Celso de Mello’s Curso de Direito Internacional . The second is Accioly and colleague’s textbook, based on his 1935 three-volume treatise, 28 a celebrated and extensive work translated into both French and Spanish. 29 The abridged textbook version was first published in 1948. Since Accioly’s passing in 1962, similarly to what we see in the tradition of English language classics such as those by Lassa Oppenheim, the textbook has lived ‘other lives’ under new editorship and authorship – Ambassador Geraldo Eulálio do Nascimento e Silva became its editor from 1970 and its author since 1996 and Professor Paulo Borba Casella has been listed as an author from 2008. 30 The textbook is currently in its impressive 26th edition. 31 We recognize the merit of looking at these works through a historical lens 32 and will indeed attribute some of their idiosyncrasies to their temporal dislocation. However, we chose to engage with them in the same context as the other eight textbooks in analysis – they are still relevant to paint a picture of international law in Brazil today. We identified two women-authored textbooks: Gilda Russomano’s Direito Internacional Público 33 and Deisy Ventura’s Direito Internacional Público (co-authored with Ricardo Seitenfus). 34 We decided not to include these works in our analysis because neither book has been updated and reissued, 35 and, unlike Celso de Mello’s textbook, they do not continue to be used widely in law schools.

We undertook this research, under the auspices of a research group, as a collective effort with multiple research assistants, coordinated by us as co-authors. We divided the work into two phases. In the first phase, researchers analysed the textbooks themselves as well as the authors’ biographies. 36 We asked researchers to compile data under the following categories: (i) biographies of authors, documenting institutions where they obtained their degrees, where they teach law (for those who were/are law professors) and their practice outside academia; (ii) international law topics addressed in each textbook; and (iii) references used in each textbook – for example, treaties, cases and bibliography. In parallel, we conducted weekly literature review sessions on relevant subjects. We compiled this data in one general report. The preliminary results were published in a series of blog posts. 37

By the end of this first stage of the research, there were several questions that could not be answered by analysing the raw data that we had obtained. They included questions about the importance of editors and publishers in dictating the content of the books in question, who the authors envisaged as their main audience, reflections about whose works they chose to cite and why and more open questions about professional networks and mentorships that would help us better understand the characteristics of a Brazilian ‘invisible college’. We decided to interview all of the living authors to help us answer these questions. We developed a semi-structured questionnaire around four major themes: biography; sources of international law and bibliography used to produce the textbook; sex, gender and racial self-identification; and the authors’ relationship with their publishers. 38 All authors were extremely generous with their time and accepted our invitation to be interviewed. They received the questionnaire in advance and gave us lengthy and illuminating, as well as entertaining, interviews. All interviews were then transcribed by members of the research group and then coded using ATLAS.TI, a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software.