Evolutionary Psychology Research Paper Topics

View the list of evolutionary psychology research paper topics. Read about the history of evolutionary psychology. Check other research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Foundations of Evolutionary Psychology

- The Theoretical Foundations of Evolutionary Psychology

- Life History Theory and Evolutionary Psychology

- Methods of Evolutionary Sciences

- Evolutionary Psychology and Its Critics

- Intuitive Ontologies and Domain Specificity

Evolutionary Psychology of Survival

- The Evolutionary Psychology of Food Intake and Choice

- The Behavioral Immune System

- Spatial Navigation and Landscape Preferences

- Adaptations to Predators and Prey

- Adaptations to Dangers from Humans

Evolutionary Psychology of Mating

- Adaptationism and Human Mating Psychology

- Fundamentals of Human Mating Strategies

- Physical Attractiveness

- Contest Competition in Men

- Women’s Sexual Interests Across the Ovulatory Cycle

- Human Sperm Competition

- Human Sexuality and Inbreeding Avoidance

- Sexual Coercion

- Love and Commitment in Romantic Relationships

Evolutionary Psychology of Parenting and Kinship

- Kin Selection

- Evolution of Paternal Investment

- Parental Investment and Parent-Offspring Conflict

- The Evolutionary Ecology of the Family

- Hunter-Gatherer Families and Parenting

- The Role of Hormones in the Evolution of Human Sociality

Evolutionary Psychology of Group Living: Cooperation and Conflict

- Adaptations for Reasoning About Social Exchange

- Interpersonal Conflict and Violence

- Women’s Competition and Aggression

- Prejudices: Managing Perceived Threats to Group Life

- Leadership in War: Evolution, Cognition, and the Military Intelligence Hypothesis

Evolutionary Psychology of Culture and Coordination

- Cultural Evolution

- The Evolutionary Foundations of Status Hierarchy

- The Evolution and Ontogeny of Ritual

- The Origins of Religion

- The False Allure of Group Selection

Evolutionary Psychology Interfaces with Traditional Psychology Disciplines

- Evolutionary Cognitive Psychology

- Evolutionary Developmental Psychology

- Evolutionary Social Psychology

- The General Factor of Personality: A Hierarchical Life History Model

- The Evolution of Cognitive Bias

- Biological Function and Dysfunction: Conceptual Foundations of Evolutionary Psychopathology

- Evolutionary Psychology and Mental Health

Evolutionary Psychology Interfaces Across Traditional Academic Disciplines

- Evolutionary Psychology and Evolutionary Anthropology

- Evolutionary Genetics

- Evolutionary Psychology and Endocrinology

- Evolutionary Political Psychology

- Evolutionary Literary Study

Practical Applications of Evolutionary Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology and Public Policy

- Evolution and Consumer Psychology

- Evolution and Organizational Leadership

- Evolutionary Psychology and the Law

History of Evolutionary Psychology

Evolutionary psychology is the application of the principles and knowledge of evolutionary biology to psychological theory and research. Its central assumption is that the human brain is comprised of a large number of specialized mechanisms that were shaped by natural selection over vast periods of time to solve the recurrent information-processing problems faced by our ancestors (Symons, 1995).These problems include such things as choosing which foods to eat, negotiating social hierarchies, dividing investment among offspring, and selecting mates. The field of evolutionary psychology focuses on identifying these information-processing problems, developing models of the brain-mind mechanisms that may have evolved to solve them, and testing these models in research (Buss, 1995; Tooby & Cosmides, 1992).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

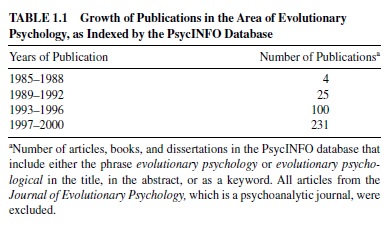

The field of evolutionary psychology has emerged dramatically over the last 15 years, as indicated by exponential growth in the number of empirical and theoretical articles in the area (Table 1.1). These articles extend into all branches of psychology—from cognitive psychology (e.g., Cosmides, 1989; Shepard, 1992) to developmental psychology (e.g., Ellis, McFadyen-Ketchum, Dodge, Pettit, & Bates, 1999; Weisfeld, 1999), abnormal psychology (e.g., Mealey, 1995; Price, Sloman, Gardner, Gilbert, & Rhode, 1994), social psychology (e.g., Daly & Wilson, 1988; Simpson & Kenrick, 1997), personality psychology (e.g., Buss, 1991; Sulloway, 1996), motivation-emotion (e.g., Nesse & Berridge, 1997; Johnston, 1999), and industrial-organizational psychology (e.g., Colarelli, 1998; Studd, 1996). The first undergraduate textbook on evolutionary psychology was published in 1999 (Buss, 1999), and since then at least three other undergraduate textbooks have been published in the area (Barrett, Dunbar, & Lycett, 2002; Cartwright, 2000; Gaulin & McBurney, 2000).

In this research paper we provide an introduction to the field of evolutionary psychology. We describe the methodology that evolutionary psychologists use to explain human cognition and behavior. This description begins at the broadest level with a review of the basic, guiding assumptions that are employed by evolutionary psychologists. We then show how evolutionary psychologists apply these assumptions to develop more specific theoretical models that are tested in research. We use examples of sex and mating to demonstrate how evolutionary psychological theories are developed and tested.

Levels of Explanation in Evolutionary Psychology

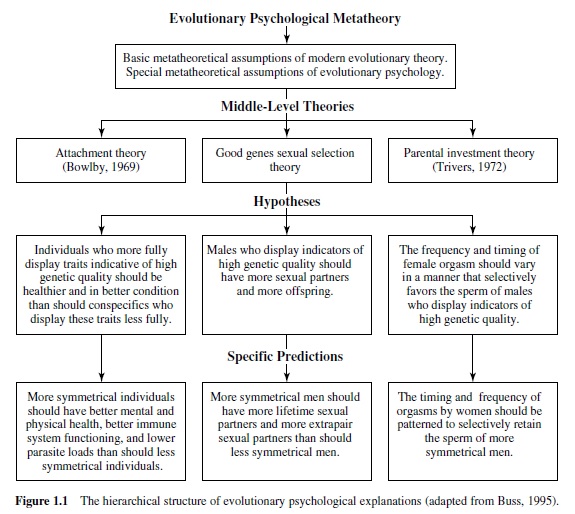

Why do siblings fight with each other for parental attention? Why are men more likely than women to kill sexual rivals? Why are women most likely to have extramarital sex when they are ovulating? To address such questions, evolutionary psychologists employ multiple levels of explanation ranging from broad metatheoretical assumptions, to more specific middle-level theories, to actual hypotheses and predictions that are tested in research (Buss, 1995; Ketelaar & Ellis, 2000). These levels of explanation are ordered in a hierarchy (see Figure 1.1) and constitute the methodology that evolutionary psychologists use to address questions about human nature.

At the top of the hierarchy are the basic metatheoretical assumptions of modern evolutionary theory. This set of guiding assumptions, which together are referred to as evolutionary metatheory, provide the foundation that evolutionary scientists use to build more specific theoretical models. We begin by describing (a) the primary set of metatheoretical assumptions that are consensually held by evolutionary scientists and (b) the special set of metatheoretical assumptions that distinguish evolutionary psychology. We use the term evolutionary psychological metatheory to refer inclusively to this primary and special set of assumptions together.

As shown in Figure 1.1, at the next level down in the hierarchy, just below evolutionary psychological metatheory, are middle-level evolutionary theories. These theories elaborate the basic metatheoretical assumptions into a particular psychological domain such as mating or cooperation. In this research paper we consider two related middle-level evolutionary theories—parental investment theory and good genes sexual selection theory—each of which applies the assumptions of evolutionary psychological metatheory to the question of reproductive strategies. In different ways these middle-level theories attempt to explain differences between the sexes as well as variation within each sex in physical and psychological adaptations for mating and parenting.

At the next level down are the actual hypotheses and predictions that are drawn from middle-level evolutionary theories (Figure 1.1). A hypothesis is a general statement about the state of the world that one would expect to observe if the theory from which it was generated were in fact true. Predictions are explicit, testable instantiations of hypotheses. We conclude this research paper with an evaluation of hypotheses and specific predictions about sexual behavior that have been derived from good genes sexual selection theory. Special attention is paid to comparison of human and nonhuman animal literatures.

The Metatheory Level of Analysis

Scientists typically rely on basic (although usually implicit) metatheoretical assumptions when they construct and evaluate theories. Evolutionary psychologists have often called on behavioral scientists to make explicit their basic assumptions about the origins and structure of the mind (see Gigerenzer, 1998). Metatheoretical assumptions shape how scientists generate, develop, and test middle-level theories and their derivative hypotheses and predictions (Ketelaar & Ellis, 2000). These basic assumptions are often not directly tested after they have been empirically established. Instead they are used as a starting point for further theory and research. Newton’s laws of motion form the metatheory for classical mechanics, the principles of gradualism and plate tectonics provide a metatheory for geology, and the principles of adaptation through natural selection provide a metatheory for biology. Several scholars (e.g., Bjorklund, 1997; Richters, 1997) have argued that the greatest impediment to psychology’s development as a science is the absence of a coherent, agreed-upon metatheory.

A metatheory operates like a map of a challenging conceptual terrain. It specifies both the landmarks and the boundaries of that terrain, suggesting which features are consistent and which are inconsistent with the core logic of the metatheory. In this way a metatheory provides a set of powerful methodological heuristics: “Some tell us what paths to avoid (negative heuristic), and others what paths to pursue (positive heuristic)” (Lakatos, 1970, p. 47). In the hands of a skilled researcher, a metatheory “provides a guide and prevents certain kinds of errors, raises suspicions of certain explanations or observations, suggests lines of research to be followed, and provides a sound criterion for recognizing significant observations on natural phenomena” (Lloyd, 1979, p. 18). The ultimate contribution of a metatheory is that it synthesizes middle-level theories, allowing the empirical results of a variety of different theory-driven research programs to be explicated within a broader metatheoretical framework. This facilitates systematic cumulation of knowledge and progression toward a coherent big picture, so to speak, of the subject matter (Ketelaar & Ellis, 2000).

Metatheoreticalassumptions That Are Consensually Held By Evolutionary Scientists

When asked what his study of the natural world had revealed about the nature of God, biologist J. B. S. Haldane is reported to have made this reply: “That he has an inordinate fondness for beetles.” Haldane’s retort refers to the extraordinary diversity of beetle species found throughout the world—some 290,000 species have so far been discovered (E. O. Wilson, 1992). Beetles, moreover, come in a bewildering variety of shapes and sizes, from tiny glittering scarab beetles barely visible to the naked eye to ponderous stag beetles with massive mandibles half the size of their bodies. Some beetles make a living foraging on lichen and fungi; others subsist on a diet of beetles themselves.

The richness and diversity of beetle species are mirrored throughout the biological world. Biologists estimate that anywhere from 10 to 100 million different species currently inhabit the Earth (E. O. Wilson, 1992), each one in some respect different from all others. How are we to explain this extraordinary richness of life? Why are there so many species and why do they have the particular characteristics that they do? The general principles of genetical evolution drawn from modern evolutionary theory, as outlined by W. D. Hamilton (1964) and instantiated in more contemporary so-called selfish gene theories of genetic evolution via natural and sexual selection, provide a set of core metatheoretical assumptions for answering these questions. Inclusive fitness theory conceptualizes genes or individuals as the units of selection (see Dawkins, 1976; Hamilton, 1964; Williams, 1966). In contrast, “multilevel selection theory” is based on the premise that natural selection is a hierarchical process that can operate at many levels, including genes, individuals, groups within species, or even multi-species ecosystems. Thus, multilevel selection theory is conceptualized as an elaboration of inclusive fitness theory (adding the concept of group-level adaptation) rather than an alternative to it (D. S. Wilson & Sober, 1994). Whereas inclusive fitness theory is consensually accepted among evolutionary scientists, multilevel selection theory is not. Thus, this review of basic metatheoretical assumptions only focuses on inclusive fitness theory.

Natural Selection

During his journey around the coastline of South America aboard the HMS Beagle, Charles Darwin was intrigued by the sheerdiversityofanimalandplantspeciesfoundinthetropics, by the way that similar species were grouped together geographically, and by their apparent fit to local ecological conditions. Although the idea of biological evolution had been around for some time, what had been missing was an explanation of how evolution occurred—that is, what had been missing was an account of the mechanisms responsible for evolutionary change. Darwin’s mechanism, which he labeled natural selection, served to explain many of the puzzling facts about the biological world: Why were there so many species? Why are current species so apparently similar in many respects both to each other and to extinct species? Why do organisms have the specific characteristics that they do?

The idea of natural selection is both elegant and simple, and can be neatly encapsulated as the result of the operation of three general principles: (a) phenotypic variation, (b) differential fitness, and (c) heritability.

As is readily apparent when we look around the biological world, organisms of the same species vary in the characteristics that they possess; that is, they have slightly different phenotypes. A whole branch of psychology—personality and individual differences—is devoted to documenting and understanding the nature of these kinds of differences in our own species. Some of these differences found among members of a given species will result in differences in fitness — that is, some members of the species will be more likely to survive and reproduce than will others as a result of the specific characteristics that they possess. For evolution to occur, however, these individual differences must be heritable — that is, they must be reliably passed on (via shared genes) from parents to their offspring. Over time, the characteristics of a population of organisms will change as heritable traits that enhance fitness will become more prevalent at the expense of less favorable variations.

For example, consider the evolution of bipedalism in humans. Paleoanthropological evidence suggests that upright walking (at least some of the time) was a feature of early hominids from about 3.5 million years ago (Lovejoy, 1988). Presume that there was considerable variation in the propensity to walk upright in the ancestors of this early hominid species as the result of differences in skeletal structures, relevant neural programs, and behavioral proclivities. Some hominids did and some did not.Also presume that walking on two feet much of the time conferred some advantage in terms of survival and reproductive success. Perhaps, by freeing the hands, bipedalism allowed objects such as meat to be carried long distances (e.g., Lovejoy, 1981). Perhaps it also served to cool the body by reducing the amount of surface area exposed to the harsh tropical sun, enabling foraging throughout the hottest parts of the day (e.g., Wheeler, 1991). Finally, presume that these differences in the propensity for upright walking were heritable in nature—they were the result of specific genes that were reliably passed on from parents to offspring.The individuals who tended to walk upright would be, on average, more likely to survive (and hence, to reproduce) than would those who did not. Over time the genes responsible for bipedalism would become more prevalent in the population as the individuals who possessed them were more reproductively successful than were those who did not, and bipedalism itself would become pervasive in the population.

Several points are important to note here. First, natural selection shapes not only the physical characteristics of organisms, but also their behavioral and cognitive traits. The shift to bipedalism was not simply a matter of changes in the anatomy of early hominids; it was also the result of changes in behavioral proclivities and in the complex neural programs dedicated to the balance and coordination required for upright walking. Second, although the idea of natural selection is sometimes encapsulated in the slogan the survival of the fittest, ultimately it is reproductive fitness that counts. It doesn’t matter how well an organism is able to survive. If it fails to pass on its genes, then it is an evolutionary dead end, and the traits responsible for its enhanced survival abilities will not be represented in subsequent generations. This point is somewhat gruesomely illustrated by many spider species in which the male serves as both meal and mate to the female—often at the same time. Ultimately, although one must survive to reproduce, reproductive goals take precedence.

Natural selection is the primary process which is responsible for evolutionary change over times as more favorable variants are retained and less favorable ones are rejected (Darwin, 1859). Through this filtering process, natural selection produces small incremental modifications in existing phenotypes, leading to an accumulation of characteristics that are organized to enhance survival and reproductive success. These characteristics that are produced by natural selection are termed adaptations. Adaptations are inherited and reliably developing characteristics of species that have been selected for because of their causal role in enhancing the survival and reproductive success of the individuals that possess them (see Buss, Haselton, Shackelford, Bleske, & Wakefield, 1998; Dawkins, 1986; Sterelny & Griffiths, 1999; Williams, 1966, 1992, for definitions of adaptation).

Adaptations have biological functions. The immune system functions to protect organisms from microbial invasion, the heart functions as a blood pump, and the cryptic coloring of many insects has the function of preventing their detection by predators. The core idea of evolutionary psychology is that many psychological characteristics are adaptations—just as many physical characteristics are—and that the principles of evolutionary biology that are used to explain our bodies are equally applicable to our minds. Thus, various evolutionary psychological research programs have investigated psychological mechanisms—for mate selection, fear of snakes, face recognition, natural language, sexual jealousy, and so on—as biological adaptations that were selected for because of the role they played in promoting reproductive success in ancestral environments.

It is worth noting, however, that natural selection is not the only causal process responsible for evolutionary change (e.g., Gould & Lewontin, 1979). Traits may also become fixated in a population by the process of genetic drift, whereby neutral or even deleterious characteristics become more prevalent due to chance factors. This may occur in small populations because the fittest individuals may turn out—due to random events—not to be the ones with the greatest reproductive success. It does not matter how fit you are if you drown in a flood before you get a chance to reproduce. Moreover, some traits may become fixated in a population not because they enhance reproductive success, but because they are genetically or developmentally yoked to adaptations that do. For example, the modified wrist bone of the panda (its “thumb”) seems to be an adaptation for manipulating bamboo, but the genes responsible for this adaptation also direct the enlarged growth of the corresponding bone in the panda’s foot, a feature that serves no function at all (Gould, 1980).

There is much debate among evolutionary biologists and philosophers of biology regarding the relative importance of different evolutionary processes (see Sterelny & Griffiths, 1999, for a good introduction to these and other issues in the philosophy of biology). The details of these disputes, however, need not concern us here. What is important to note is that not all of the products of evolution will be biological adaptations with evolved functions. The evolutionary process also results in by-products of adaptations, as well as a residue of noise (Buss et al., 1998; Tooby & Cosmides, 1992). Examples of by-products are legion. The sound that hearts make when they beat, the white color of bones, and the human chin are all nonfunctional by-products of natural selection. In addition, random variation in traits—as long as this variation is selectively neutral (neither enhancing nor reducing biological fitness)—can also be maintained as residual noise in organisms.

Demarcating the different products of evolution is an especially important task for evolutionary psychologists. It has often been suggested that many of the important phenomena that psychologists study—for example, reading, writing, religion—are by-products of adaptations rather than adaptations themselves (e.g., Gould, 1991a). Of course, even byproducts can be furnished with evolutionary explanations in terms of the adaptations to which they are connected (Tooby & Cosmides, 1992). Thus, for example, the whiteness of bones is a by-product of the color of calcium salts, which give bones their hardness and rigidity; the chin is a byproduct of two growth fields; and reading and writing are by-products (in part) of the evolved mechanisms underlying human language (Pinker, 1994).

The important question is how to distinguish adaptations from nonadaptations in the biological world. Because we cannot reverse time and observe natural selection shaping adaptations, we must make inferences about evolutionary history based on the nature of the traits we see today. A variety of methods can (and should) be employed to identify adaptations (see M. R. Rose & Lauder, 1996). Evolutionary psychologists, drawing on the work of George Williams (1966), typically emphasize the importance of special design features such as economy, efficiency, complexity, precision, specialization, reliability, and functionality for identifying adaptations (e.g., Buss et al., 1998; Pinker, 1997; Tooby & Cosmides, 1990). One hallmark that a trait is the product of natural selection is that it demonstrates adaptive complexity —that is, the trait is composed of a number of interrelated parts or systems that operate in concert to generate effects that serve specific functions (Dawkins, 1986; Pinker, 1997).

Echolocation in bats is a good example of such a trait. A collection of interrelated mechanisms allows foraging bats to maneuver around obstacles in complete darkness and to pick out small rapidly moving prey on the wing. Echolocating bats have a number of specialized mechanisms that precisely, reliably, and efficiently enable them to achieve the function of nocturnal locomotion and foraging. Bats have mechanisms that allow them to produce rapid, high-frequency, shortwavelength cries that are reflected by small objects. Moreover, the frequency and rapidity of these cries are modified depending on the distance of the object being detected (lowfrequency waves penetrate further but can only be used to detect large objects). Bats also have specialized mechanisms that protect their ears while they are emitting loud sounds, and their faces are shaped to enhance the detection of their returning echoes. It is extraordinary unlikely that such a complex array of intertwining processes could have arisen by chance or as a by-product of evolutionary processes. Thus, one has clear warrant in this case to assert that echolocation in bats is a biological adaptation.

Many traits, however, may not be so clearly identifiable as adaptations. Furthermore, there are often disputes about just what function some trait has evolved to serve, even if one can be reasonably sure that it is the product of natural selection. In adjudicating between alternative evolutionary hypotheses, one can follow the same sort of strategies that are employed when comparing alternative explanations in any domain in science—that is, one should favor the theory or hypothesis that best explains the evidence at hand (Haig & Durrant, 2000; Holcomb, 1998) and that generates novel hypotheses that lead to new knowledge (Ketelaar & Ellis, 2000).

Consider, for example, the alternative explanations that have been offered for the origin of orgasm in human females.

- Female orgasm serves no evolved function and is a byproduct of selection on male orgasm, which is necessary for fertilization to occur (Gould, 1991b, pp. 124–129; Symons, 1979).

- Orgasm is an adaptation that promotes pair-bonding in the human species (Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 1989).

- Female orgasm is an adaptation that motivates females to seek multiple sexual partners, confusing males about paternity and thus reducing the probability of subsequent male infanticide (Hrdy, 1981).

- Female orgasm is an adaptation that serves to enhance sperm retention, therefore allowing females to exert some control over the paternity of their offspring via differential patterns of orgasm with specific male partners, especially those of high genetic quality (Baker & Bellis, 1993; Smith, 1984).

Although all of these models have some plausibility, it is the last suggestion that is beginning to be accepted as the best current explanation. Baker and Bellis (1993) have demonstrated that females retain more sperm if they experience copulatory orgasms up to 45 min after—or at the same timeas—their male partners. Thus, depending on their timing, orgasms appear to enhance the retention of sperm via the “upsuck” from the vagina into the cervix. The selective sperm retention model predicts that women will experience more orgasms—and specifically, more high-sperm-retention orgasms—with men who have specific indicators of genetic quality.This prediction has been supported in research on dating and married couples (Thornhill, Gangestad, & Comer, 1995). Moreover, the occurrence of high sperm retention orgasms are a significant predictor of a desire for pregnancy in women, suggesting that female orgasms are one mechanism for increasing the likelihood of conception (Singh, Meyer, Zambarano, & Hurlbert, 1998).

Although there are a number of theories of extrapair mating in human females (mating that occurs outside of a current, ongoing relationship), one prominent suggestion is that extrapair mating has evolved to enhance reproductive success by increasing selective mating with males who demonstrate high genetic quality (e.g., Gangestad, 1993; Greiling & Buss, 2000). In support of this idea, men who possess indicators of high genetic quality (as assessed by degree of symmetry of bilateral physical traits) are more likely to be chosen by women specifically as extrapair sex partners but not as partners in long-term relationships (Gangestad & Simpson, 2000). Further, Bellis and Baker (1990) found that women were most likely to copulate with extrapair partners but not with in-pair partners during the fertile phase of their menstrual cycles. Finally, as a result of the type and frequency of orgasms experienced by women, it appears that levels of sperm retention are significantly higher during extrapair copulations than during copulations with in-pair partners (Baker & Bellis, 1995).

In summary, although more research needs to be done, our best current explanation for the human female orgasm is that it is an adaptation specifically, precisely, and efficiently designed to manipulate the paternity of offspring by favoring the sperm of males of high genetic quality.This model (a) concurs with what is known about female orgasm; (b) generated specific, testable predictions about patterns of variation in female orgasm that were as yet unobserved and were not forecast by competing models; (c) generated interesting new lines of research on female orgasm that provided support for the predictions; and (d) led to acquisition of new knowledge about the timing and probability of female orgasm with different partners.

Sexual Selection

Not all adaptations can be conceptualized as adaptations for survival per se.Although the bat’s complex system of echolocation enables it to navigate and forage in darkness, the human female orgasm has no such obvious utilitarian function.As Darwin (1871) clearly recognized, many of the interesting features that plants and animals possess, such as the gaudy plumage and elaborate songs of many male birds, serve no obvious survival functions. In fact, if anything, such traits are likely to reduce survival prospects by attracting predators, impeding movement, and so on. Darwin’s explanation for such characteristics was that they were the product of a process that he labeled sexual selection. This kind of selection arises not from a struggle to survive, but rather from the competition that arises over mates and mating (Andersson, 1994; Andersson & Iwasa, 1996). If—for whatever reason—having elongated tail feathers or neon blue breast plumage enables one to attract more mates, then such traits will increase reproductive success. Moreover, to the extent that such traits are also heritable, they will be likely to spread in the population, even if they might diminish survival prospects.

Although there is some debate about how best to conceptualize the relationship between natural and sexual selection, sexual selection is most commonly considered a component or special case of natural selection associated with mate choice and mating. This reflects the fact that differential fitness concerns differences in both survival and reproduction. Miller (1999) notes that “both natural selection and sexual selection boil down to one principle: Some genes replicate themselves better than others. Some do it by helping their bodies survive better, and some by helping themselves reproduce better” (p. 334). Whereas the general processes underlying natural and sexual selection are the same (variation, fitness, heritability), the products of natural and sexual selection can look quite different. The later parts of this research paper review sexual selection theory and some of the exciting research it has generated on human mating behavior.

To summarize, we have introduced the ideas of natural and sexual selection and shown how these processes generate adaptations, by-products, and noise. We have also discussed ways in which adaptations can be distinguished from nonadaptations and have offered some examples drawn from recent research in evolutionary psychology. It is now time to consider an important theoretical advance in evolutionary theorizing that occurred in the 1960s—inclusive fitness theory— that changed the way biologists (and psychologists) think about the nature of evolution and natural selection. Inclusive fitness theory is the modern instantiation of Darwin’s theory of adaptation through natural and sexual selection.

Inclusive Fitness Theory

Who are adaptations good for? Although the answer may seem obvious—that they are good for the organisms possessing the adaptations—this answer is only partially correct; it fails to account for the perplexing problem of altruism. As Darwin puzzled, how could behaviors evolve that conferred advantage to other organisms at the expense of the principle organism that performed the behaviors? Surely such acts of generosity would be eliminated by natural selection because they decreased rather than increased the individual’s chances of survival and reproduction.

The solution to this thorny evolutionary problem was hinted at by J. B. S. Haldane, who, when he was asked if he would lay down his life for his brother, replied, “No, but I would for two brothers or eight cousins” (cited in Pinker, 1997, p. 400). Haldane’s quip reflects the fact that we each share (on average) 50% of our genes with our full siblings and 12.5% of our genes with our first cousins. Thus, from the gene’s-eye point of view, it is just as advantageous to help two of our siblings to survive and reproduce as it is to help ourselves. This insight was formalized by W. D. Hamilton (1964) and has come to be known variously as Hamilton’s rule, selfish-gene theory (popularized by Dawkins, 1976), kin-selection theory, or inclusive fitness theory.

The core idea of inclusive fitness theory is that evolution works by increasing copies of genes, not copies of the individuals carrying the genes. Thus, the genetic code for a trait that reduces personal reproductive success can be selected for if the trait, on average, leads to more copies of the genetic code in the population. A genetic code for altruism, therefore, can spread through kin selection if (a) it causes an organism to help close relatives to reproduce and (b) the cost to the organism’s own reproduction is offset by the reproductive benefit to those relatives (discounted by the probability that the relatives who receive the benefit have inherited the same genetic code from a common ancestor). For example, a squirrel who acts as a sentinel and emits loud alarm calls in the presence of a predator may reduce its own survival chances by directing the predator’s attention to itself; however, the genes that are implicated in the development of alarm-calling behavior can spread if they are present in the group of close relatives who are benefited by the alarm calling.

Special Metatheoretical Assumptions of Evolutionary Psychology

In addition to employing inclusive fitness theory, evolutionary psychologists endorse a number of special metatheoretical assumptions concerning how to apply inclusive fitness theory to human psychological processes. In particular, evolutionary psychologists argue that we should primarily be concerned with how natural and sexual selection have shaped psychological mechanisms in our species; that a multiplicity of such mechanisms will exist in the human mind; and that they will have evolved to solve specific adaptive problems encountered in ancestral environments. Although these general points also apply to other species, they are perhaps especially pertinent in a human context and they have received much attention from evolutionary psychologists. We consider these special metatheoretical assumptions, in turn, in the following discussion.

Psychological Mechanisms as the Main Unit of Analysis

Psychological adaptations, which govern mental and behavioral processes, are referred to by evolutionary psychologists as psychological mechanisms. Evolutionary psychologists emphasize that genes do not cause behavior and cognition directly. Rather, genes provide blueprints for the construction of psychological mechanisms, which then interact with environmental factors to produce a range of behavioral and cognitive outputs. Most research in evolutionary psychology focuses on identifying evolved psychological mechanisms because it is at this level where invariances occur. Indeed, evolutionary psychologists assert that there is a core set of universal psychological mechanisms that comprise our shared human nature (Tooby & Cosmides, 1992).

To demonstrate the universal nature of our psychological mechanisms, a common rhetorical device used by evolutionary psychologists (e.g., Brown, 1991; Ellis, 1992; Symons, 1987) is to imagine that a heretofore unknown tribal people is suddenly discovered. Evolutionary psychologists are willing to make a array of specific predictions—in advance—about the behavior and cognition of this newly discovered people.These predictions concern criteria that determine sexual attractiveness, circumstances that lead to sexual arousal, taste preferences for sugar and fat, use of cheater detection procedures in social exchange, nepotistic bias in parental investment and child abuse, stages and timing of language development, sex differences in violence, different behavioral strategies for people high and low in dominance hierarchies, perceptual adaptations for entraining, tracking, and predicting animate motion, and so on. The only way that the behavior and cognition of an unknown people can be known in advance is if we share with those people a universal set of specific psychological mechanisms.

Buss (1999, pp. 47–49) defines an evolved psychological mechanism as a set of structures inside our heads that (a) exist in the form they do because they recurrently solved specific problems of survival and reproduction over evolutionary history; (b) are designed to take only certain kinds of information from the world as input; (c) process that information according to a specific set of rules and procedures; (d) generate output in terms of information to other psychological mechanisms and physiological activity or manifest behavior that is directed at solving specific adaptive problems (as specified by the input that brought the psychological mechanism on-line).

Consider, for example, the psychological mechanisms underlying disgust and food aversions in humans. These psychological mechanisms, which are designed to find certain smells and tastes more aversive than others, can be said to have several features:

- They exist in the form they do because they recurrently solved specific problems of survival over evolutionary history. As an omnivorous species, humans consume a wide variety of plant and animal substances. Not all such substances, however, are safe to eat. Many plants contain natural toxins, and many animal products are loaded with parasites that can cause sickness and death. The psychological mechanisms underlying disgust and food aversions function to reduce the probability of ingesting and digesting dangerous plant and animal substances.

- These mechanisms are designed to take a specific and limited class of stimuli as input: the sight, touch, and especially taste and smell of plant and animal substances that were regularly harmful to our ancestors. Feces and animal products are especially likely to harbor lethal microorganisms and, cross-culturally, are most likely to elicit disgust (Rozin & Fallon, 1987).

- Inputs to the psychological mechanisms underlying disgust and food aversions are then processed according to a set of decision rules and procedures, such as (a) avoid plant substances that taste or smell bitter or especially pungent (indicating high concentrations of plant toxins; Profet, 1992); (b) avoid animal substances that emit smells suggestive of spoilage (indicating high levels of toxinproducing bacteria; Profet, 1992); (c) avoid foods that one has become sick after consuming in the past (Seligman & Hager, 1972); (d) and avoid foods that were not part of one’s diet in the first few years of life (especially if it is an animal product; Cashdan, 1994).

- When relevant decision rules are met, behavioral output is then generated, manifested by specific facial expressions, physical withdrawal from the offending stimuli, nausea, gagging, spitting, and vomiting.

- This output is specifically directed at solving the adaptive problem of avoiding consumption of harmful substances and of expelling these substances from the body as rapidly as possible if they have been consumed.

Evolutionary psychologists assume that humans possess a large number of specific psychological mechanisms (e.g., the ones underlying food aversions and disgust) that are directed at solving specific adaptive problems. This assumption is commonly referred to as the domain specificity or modularity of mind.

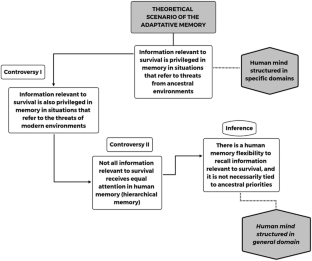

Domain Specificity of Psychological Mechanisms

Evolutionary psychologists posit that the mind comprises a large number of content-saturated ( domain-specific ) psychological mechanisms (e.g., Buss, 1995; Cosmides & Tooby, 1994; Pinker, 1997). Although evolutionary psychologists assert that the mind is not comprised primarily of content-free ( domain-general ) psychological mechanisms, it is likely that different mechanisms differ in their levels of specificity and that there are some higher-level executive mechanisms that function to integrate information across more specific lowerlevel mechanisms.

The rationale behind the domain-specificity argument is fairly straightforward: What counts as adaptive behavior differs markedly from domain to domain. The sort of adaptive problems posed by food choice, mate choice, incest avoidance, and social exchange require different kinds of solutions. As Don Symons (1992) has pointed out, there is no such thing as a general solution because there is no such thing as a general problem. The psychological mechanisms underlying disgust and food aversions, for example, are useful in solving problems of food choice but not those of mate choice. If we used the same decision rules in both domains, we would end up with some very strange mates and very strange meals indeed. Given the large array of adaptive problems faced by our ancestors, we should expect a commensurate number of domain-specific solutions to these problems.

A clear analogy can be drawn with the functional division of labor in human physiology. Different organs have evolved to serve different functions and possess properties that allow them to fulfill those functions efficiently, reliably, and economically: The heart pumps blood, the liver detoxifies poisons, the kidneysexcreteurine,andsoon.Asuper,all-purpose,domaingeneral internal organ—heart, liver, kidney, spleen, and pancreas rolled into one—faces the impossible task of serving multiple, incompatible functions. Analogously, a super, allpurpose, domain-general brain-mind mechanism faces the impossible task of efficiently and reliably solving the plethora of behavioral problems encountered by humans in ancestral environments. Thus, neither an all-purpose physiological organ nor an all-purpose brain-mind mechanism is likely to evolve. Evolutionary psychologists argue that the human brain-mind instead contains domain-specific information processing rules and biases.

These evolved domain-specific mechanisms are often referred to as psychological modules. The best way to conceptualize such modules, however, is a matter of some contention. Jerry Fodor (1983), in his classic book The Modularity of Mind, suggests that modules have the properties of being domain-specific, innately specified, localized in the brain, and able to operate relatively independently from other such systems. Potentially good examples of such psychological modules in humans include language (Pinker, 1994), face recognition (Bruce, 1988), and theory of mind (Baron-Cohen, 1995). For example, the systems underlying language ability are specially designed to deal with linguistic information, emerge in development with no formal tuition, and appear to be located in specific brain regions independent from other systems, as indicated by specific language disorders (aphasias), which can arise from localized brain damage.

Not all of the evolved psychological mechanisms proposed by evolutionary psychologists, however, can be so readily characterized. Many mechanisms—such as landscape preferences, sexual jealousy, and reasoning processes—may be domain-specific in the sense of addressing specific adaptive problems, but they are neither clearly localized (neurally speaking) nor especially autonomous from other systems. It seems most plausible to suggest that there is a considerable degree of integration and interaction between different psychological mechanisms (Karmiloff-Smith, 1992). It is this feature of human cognitive organization that allows for the tremendous flexibility and creativity of human thought processes (Browne, 1996). It is also not clear whether domain specificity is best characterized by way of specific computational mechanisms or in terms of domain-specific bodies of mental representations (Samuels, 2000).

We should also expect—in addition to whatever taxonomy of specialized mechanisms that is proposed for the human mind—that there are some domain-general processes as well. The mechanisms involved in classical and operant conditioning may be good candidates for such domain-general processes. However, even these domain-general processes appear to operate in different ways, depending on the context in question. As illustrated in a series of classic studies by Garcia and colleagues (e.g., Garcia & Koelling, 1966), rats are more likely to develop some (adaptively relevant) associations than they are others, such as that between food and nausea but not between buzzers and nausea. Similar prepared learning biases have been demonstrated in monkeys (Mineka, 1992) and also in humans (Seligman & Hagar, 1972). For example, humans are overwhelmingly more likely to associate anxiety and fear with evolutionarily relevant threats such as snakes, spiders, social exclusion, and heights than with more dangerous but evolutionarily novel threats such as cars, guns, and power lines (Marks & Nesse, 1994).

In sum, although some doubt remains over the nature and number of domain-specific psychological mechanisms that humans (and other animals) possess, the core idea of specialized adaptive processes instantiated in psychological mechanisms remains central to evolutionary psychology. An approach to the human mind that highlights the importance of evolved domain-specific mechanisms can advance our understanding of human cognition by offering a theoretically guided taxonomy of mental processes—one that promises to better carve the mind at its natural joints.

The Environment of Evolutionary Adaptedness

The concept of biological adaptation is necessarily an historical one. When we claim that the thick insulating coat of the polar bear is as an adaptation, we are claiming that possession of that trait advanced reproductive success in ancestral environments. All claims about adaptation are claims about the past because natural selection is a gradual, cumulative process. The polar bear’s thick coat arose through natural selection because it served to ward off the bitter-cold arctic weather during the polar bear’s evolutionary history. However, traits that served adaptive functions and thus were selected for in past environments may not still be adaptive in present or future environments. In a globally warmed near-future, for example, the polar bear’s lustrous pelt may become a handicap that reduces the fitness of its owner due to stress from overheating. In sum, when environments change, the conditions that proved advantageous to the evolution of a given trait may no longer exist; yet the trait often remains in place for some time because evolutionary change occurs slowly. Such vestigial traits are eventually weeded out by natural selection (if they consistently detract from fitness).

The environment in which a given trait evolved is termed its environment of evolutionary adaptedness (EEA). The EEAfor our species is sometimes loosely characterized as the Pleistocene—the 2-million-year period that our ancestors spent as hunter-gatherers in the African savanna, prior to the emergence of agriculture some 10,000 years ago. The emphasis on the Pleistocene is perhaps reasonable given that many of the evolved human characteristics of interest to psychologists, such as language, theory of mind, sophisticated tool use, and culture, probably arose during this period. However, a number of qualifications are in order. First, the Pleistocene itself captures a large span of time, in which many changes in habitat, climate and species composition took place. Second, there were a number of different hominid species in existence during this time period, each inhabiting its own specific ecological niche. Third, many of the adaptations that humans possess have their origins in time periods that substantially predate the Pleistocene era. For example, the mechanisms underlying human attachment and sociality have a long evolutionary history as part of our more general primate and mammalian heritage (Foley, 1996). Finally, some evolution (although of a relatively minor character) has also probably occurred in the last 10,000 years, as is reflected in population differences in disease susceptibility, skin color, and so forth (Irons, 1998).

Most important is that different adaptations will have different EEAs. Some, like language, are firmly anchored in approximately the last 2 million years; others, such as infant attachment, reflect a much lengthier evolutionary history (Hrdy, 1999). It is important, therefore, that we distinguish between the EEA of a species and the EEA of an adaptation. Although these two may overlap, they need not necessarily do so (Crawford, 1998). Tooby and Cosmides (1990) summarize these points clearly when they state that “the ‘environment of evolutionary adaptedness’(EEA) is not a place or a habitat, or even a time period. Rather, it is a statistical composite of the adaptation-relevant properties of the ancestral environments encountered by members of ancestral populations, weighted by their frequency and fitness-consequences” (pp. 386–387). Delineating the specific features of the EEA for any given adaptation, then, requires an understanding of the evolutionary history of that trait (e.g., is it shared by other species, or is it unique?) and a detailed reconstruction of the relevant environmental features that were instrumental in its construction (Foley, 1996).

It is not uncommon to hear the idea that changes wrought by “civilization” over the last 10,000 years have radically changed our adaptive landscape as a species. After all, back on the Pleistocene savanna there were no fast food outlets, plastic surgery, antibiotics, dating advertisements, jet airliners, and the like. Given such manifest changes in our environment and ways of living, one would expect much of human behavior to prove odd and maladaptive as psychological mechanisms that evolved in ancestral conditions struggle with the many new contingencies of the modern world. An assumption of evolutionary psychology, therefore, is that mismatches between modern environments and the EEA often result in dysfunctional behavior (such as overconsumption of chocolate ice cream, television soap operas, video games, and pornography). Real-life examples of this phenomenon are easy to find. Our color constancy mechanisms, for instance, evolved under conditions of natural sunlight. These mechanisms fail, however, under some artificial lighting conditions (Shepard, 1992). Similarly, the dopaminemediated reward mechanisms found in the mesolimbic system in the brain evolved to provide a pleasurable reward in the presence of adaptively relevant stimuli like food or sex. In contemporary environments, however, these same mechanisms are subverted by the use of psychoactive drugs such as cocaine and amphetamines, which deliver huge dollops of pleasurable reward in the absence of the adaptively relevant stimuli—often to the users’ detriment (Nesse & Berridge, 1997).

Although we can detail many ways in which contemporary and ancestral environments differ, much probably also remains the same. Humans everywhere, for example, still find and attract mates, have sex, raise families, make friends, have extramarital affairs, compete for status, consume certain kinds of food, spend time with kin, gossip, and so forth (Crawford, 1998). Indeed, Crawford (1998) argues that we should accept as our null hypothesis that current and ancestral environments do not differ in important and relevant respects for any given adaptation. Most important is that current and ancestral environments do not have to be identical in every respect for them to be the same in terms of the relevant details required for the normal development and expression of evolved psychological mechanisms. For example, the languages that people speak today are undoubtedly different from the ones our ancestors uttered some 100,000 years ago. However, what is necessary for the development of language is not the input of some specific language, but rather any kind of structured linguistic input. Adaptations have reaction norms, which are the range of environmental parameters in which they develop and function normally. For most adaptations, these norms may well encompass both current and ancestral environments (Crawford, 1998).

To summarize, in this section we have outlined three special metatheoretical assumptions that evolutionary psychologists use in applying inclusive fitness theory to human cognition and behavior. First, the appropriate unit of analysis is typically considered to be at the level of evolved psychological mechanisms, which underlie behavioral output. Second, evolutionary psychologists posit that these mechanisms are both large in number and constitute specialized information processing rules that were designed by natural selection to solve specific adaptive problems encountered during human evolutionary history. Finally, these mechanisms have evolved in ancestral conditions and are characterized by specific EEAs, which may or may not differ in important respects from contemporary environments.

The Middle-Level Theory Level of Analysis

The metatheoretical assumptions employed by evolutionary psychologists are surrounded by a protective belt, so to speak, of auxiliary theories, hypotheses, and predictions (see Buss, 1995; Ketelaar & Ellis, 2000). A primary function of the protective belt is to provide an empirically verifiable means of linking metatheoretical assumptions to observable data. In essence, the protective belt serves as the problemsolving machinery of the metatheoretical research program because it is used to provide indirect evidence in support of the metatheory’s basic assumptions (Lakatos, 1970). The protective belt does more, however, than just protect the meta-theoretical assumptions: It uses these assumptions to extend our knowledge of particular domains. For example, a group of physicists who adopt a Newtonian metatheory may construct several competing middle-level theories concerning a particular physical system, but none of these theories would violate Newton’s laws of mechanics. Each physicist designs his or her middle-level theory to be consistent with the basic assumptions of the metatheory, even if the middlelevel theories are inconsistent with each other. Competing middle-level theories attempt to achieve the best operationalization of the core logic of the metatheory as it applies to a particular domain. The competing wave and particle theories of light (generated from quantum physics metatheory) are excellent contemporary exemplars of this process.

After a core set of metatheoretical assumptions become established among a community of scientists, the day-to-day workings of these scientists are generally characterized by the use of— not the testing of— these assumptions. Metatheoretical assumptions are used to construct plausible alternative middle-level theories. After empirical evidence has been gathered, one of the alternatives may emerge as the best available explanation of phenomena in that domain. It is this process of constructing and evaluating middle-level theories that characterizes the typical activities of scientists attempting to use a metatheory to integrate, unify, and connect their varying lines of research (Ketelaar & Ellis, 2000).

Middle-level evolutionary theories are specific theoretical models that provide a link between the broad metatheoretical assumptions used by evolutionary psychologists and the specific hypotheses and predictions that are tested in research. Middle-level evolutionary theories are consistent with and guided by evolutionary metatheory but in most cases cannot be directly deduced from it (Buss, 1995). Middle-level theories elaborate the basic assumptions of the metatheory into a particular psychological domain. For example, parental investment theory (Trivers, 1972) applies evolutionary metatheory to the question of why, when, for what traits, and to what degree selection favors differences between the sexes in reproductive strategies. Conversely, attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969; Simpson, 1999), life history theory (e.g., Chisholm, 1999), and good genes sexual selection theory (e.g., Gangestad & Simpson, 2000) each in different ways applies evolutionary metatheory to the question of why, when, for what traits, and to what degree selection favors differences within each sex in reproductive strategies. In this section we review parental investment theory and good genes sexual selection theory as exemplars of middle-level evolutionary theories.

Parental Investment Theory

Imagine that a man and a woman each had sexual intercourse with 100 different partners over the course of a year. The man could potentially sire 100 children, whereas the woman could potentially give birth to one or two. This huge discrepancy in the number of offspring that men and women can potentially produce reflects fundamental differences between the sexes in the costs of reproduction. Sperm, the sex cells that men produce, are small, cheap, and plentiful. Millions of sperm are produced in each ejaculate, and one act of sexual intercourse (in principle) is the minimum reproductive effort needed by a man to sire a child. By contrast, eggs, the sex cells that women produce, are large, expensive, and limited in number. Most critical is that one act of sexual intercourse plus 9 months gestation, potentially dangerous childbirth, and (in traditional societies) years of nursing and carrying a child are the minimum amount of reproductive effort required by a woman to successfully reproduce. These differences in what Trivers (1972) has termed parental investment have wide-ranging ramifications for the evolution of sex differences in body, mind, and behavior. Moreover, these differences hold true not only for humans but also for all mammalian species.

Trivers (1972) defined parental investment as “any investment by the parent in an individual offspring’s chance of surviving (and hence reproductive success) at the cost of the parent’s ability to invest in other offspring” (p. 139). Usually, but not always, the sex with the greater parental investment is the female. These differences in investment are manifest in various ways, from basic asymmetries in the size of male and female sex cells (a phenomenon known as anisogamy ) through to differences in the propensity to rear offspring. For most viviparous species (who bear live offspring), females also shoulder the burden of gestation—and in mammals, lactation and suckling. In terms of parental investment, the sex that invests the most becomes a limiting resource for the other, less investing sex (Trivers, 1972). Members of the sex that invests less, therefore, should compete among themselves for breeding access to the other, more investing sex. Because males of many species contribute little more than sperm to subsequent offspring, their reproductive success is primarily constrained by the number of fertile females that they can inseminate. Females, by contrast, are constrained by the number of eggs that they can produce and (in species with parental care) the number of viable offspring that can be raised. Selection favors males in these species who compete successfully with other males or who have qualities preferred by females that increase their mating opportunities. Conversely, selection favors females who choose mates who have good genes and (in paternally investing species) are likely to provide external resources such as food or protection to the female and her offspring (Trivers, 1972).

Parental investment theory, in combination with the metatheoretical assumptions of natural and sexual selection, generates an array of hypotheses and specific predictions about sex differences in mating and parental behavior. According to parental investment theory, the sex that invests more in offspring should be more careful and discriminating in mate selection, should be less willing to engage in opportune mating, and should be less inclined to seek multiple sexual partners. By contrast, the sex investing less in offspring should be less choosy about whom they mate with, compete more strongly among themselves for mating opportunities (i.e., take more risks and be more aggressive in pursuing sexual contacts), and be more inclined to seek multiple mating opportunities. The magnitude of these sex differences should depend on the magnitude of differences between males and females in parental investment during a species’ evolutionary history. In species in which males only contribute their sperm to offspring, males should be much more aggressive than should females in pursuing sexual contacts with multiple partners, and females should be much choosier than should males in accepting or rejecting mating opportunities. In contrast, in species such as humans in which both males and females typically make high levels of investment in offspring, sex differences in mating competition and behavior should be more muted. Nonetheless, the sex differences predicted by parental investment theory are well documented in humans as well as in many other animals. In humans, for example, men are more likely than are women to pursue casual mating opportunities and multiple sex partners, men tend to have less rigid standards than women do for selecting mates, and men tend to engage in more extreme intrasexual competition than women do (Buss, 1994; Daly & Wilson, 1988; Ellis & Symons, 1990; Symons, 1979).

Among mammalian species, human males are unusual insofar as they contribute nonnegligible amounts of investment to offspring. Geary (2000), in a review of the evolution and proximate expression of human paternal investment, has proposed that (a) over human evolutionary history fathers’ investment in families tended to improve but was not essential to the survival and reproductive success of children and (b) selection consequently favored a mixed paternal strategy, with different men varying in the extent to which they allocated resources to care and provisioning of children. Under these conditions, selection should favor psychological mechanisms in females that are especially attuned to variation in potential for paternal investment. This hypothesis has been supported by much experimental and cross-cultural data showing that when they select mates, women tend to place relatively strong emphasis on indicators of a man’s willingness and ability to provide parental investment (e.g., Buss, 1989; Ellis, 1992; Symons, 1979). These studies have typically investigated such indicators as high status, resourceaccruing potential, and dispositions toward commitment and cooperation.

The other side of the coin is that men who invest substantially in offspring at the expense of future mating opportunities should also be choosy about selecting mates. Men who provide high-quality parental investment (i.e., who provide valuable economic and nutritional resources; who offer physical protection; who engage in direct parenting activities such as teaching, nurturing, and providing social support and opportunities) are themselves a scarce resource for which women compete. Consequently, high-investing men should be as careful and discriminating as women are about entering long-term reproductive relationships. Along these lines, Kenrick, Sadalla, Groth, and Trost (1990) investigated men’s and women’s minimum standards for selecting both shortterm and long-term mates. Consistent with many other studies (e.g., Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Symons & Ellis, 1989), men were found to have minimum standards lower than those of women for short-term sexual relationships (e.g., one-night stands); however, men elevated their standards to levels comparable to those of women when choosing long-term mates (Kenrick et al., 1990).

Mate Retention Strategies

In species with internal fertilization (all mammals, birds, reptiles, and many fish and insects), males cannot identify their offspring with certainty. In such species, males who invest paternally run the risk of devoting time and energy to offspring who are not their own. Thus, male parental investment should only evolve as a reproductive strategy when fathers have reasonably high confidence of paternity—that is, males should be selected to be high-investing fathers only to offspring who share their genes. When male parental investment does evolve, selection should concomitantly favor the evolution of male strategies designed to reduce the chance of diverting parental effort toward unrelated young (Daly, Wilson, & Weghorst, 1982; Symons, 1979). Mate retention strategies (including anatomical and behavioral adaptations) are favored by sexual selection in paternally investing species because they increase the probability that subsequent investment made by fathers in offspring contributes to their own fitness and not to that of other males.

A fascinating array of mate retention strategies has been documented in many animal species. Male damselflies, for example, possess a dual-function penis that has special barbs that enables them to remove any sperm from prior matings before inseminating the female themselves. Furthermore, male damselflies remain physically attached to the female after mating until she has laid her eggs, thus ensuring that other males cannot fertilize them. In many species of birds with biparental care, males adjust their subsequent paternal investment (e.g., feeding of nestlings) depending on their degree of paternity certainty as determined by such factors as time spent with the mate and degree of extrapair matings in which she has engaged. The greater the likelihood that the offspring he is raising is not his own, the less investment is offered (e.g., Moller, 1994; Moller & Thornhill, 1998; but see Kempenaers, Lanctot, & Robertson, 1998). Sexual jealousy in humans has also been proposed as an evolved motivational system that underlies mate retention behaviors and functions to reduce the probability of relationship defection and to increase certainty of paternity in males (Buss, 2000; Daly et al., 1982). Daly et al. (1982) suggest that in men, pervasive mate retention strategies include “the emotion of sexual jealousy, the dogged inclination of men to possess and control women, and the use or threat of violence to achieve sexual exclusivity and control” (p. 11).

Females, of course, are not passive spectators to these male manipulations, but have evolved a host of strategies themselves to advance their own inclusive fitness. In many species females may try to extract investment from males through various means such as withholding sex until resources are provided, obscuring the time that they are fertile to encourage prolonged male attention, and preventing males from investing resources in multiple females. Furthermore, in some circumstances it may benefit females to extract material resources from one male while pursuing extrapair matings with other males who may be of superior genetic quality (see early discussion of the function of female orgasm; see also Buss, 1994; Greiling & Buss, 2000; for birds, see Moller & Thornhill, 1998; Petrie & Kempenaers, 1998).

Although the general pattern of greater female parental investment and less male parental investment is most common, a variety of species exhibit the opposite arrangement. For example, in a bird species called the red-necked phalarope, it is the male who takes on the burden of parental investment, both incubating and feeding subsequent offspring. As predicted by parental investment theory, it is the female in this species who is physically larger, who competes with other females for reproductive opportunities, and who more readily pursues and engages in multiple matings. In addition, levels of parental investment may vary within a species over time, with corresponding changes in mating behavior. For example, in katydids or bush crickets, males contribute to offspring by offering mating females highly nutritious sperm packages called spermatophores. When food resources are abundant, males can readily produce these spermatophores. Under these conditions, males compete with each other for mating access to females and readily pursue multiple mating opportunities. When food resources are scarce, however, spermatophores are costly to produce. Under these conditions, it is the females who compete with each other for mating access to males with the valued spermatophores, and it is females who more readily engage in multiple matings (see Andersson, 1994, pp. 100–103). These examples of so-called sex-role reversed species illustrate that sex differences do not arise from biological sex per se; rather, they arise from differences between the sexes in parental investment.

Parental investment theory is one of the most important middle-level theories that guides research into many aspects of human and animal behavior. Both the nature and the magnitude of sex differences in mating and parental behaviors can be explained by considering differences between the sexes in parental investment over a species’evolutionary history. A host of general hypotheses and specific predictions have been derived from considering the dynamics of parental investment and sexual selection, and much empirical evidence in both humans and other animals has been garnered in support of these hypotheses and predictions. Parental investment theory is one of the real triumphs of evolutionary biology and psychology and gives support to a host of important metatheoretical assumptions.

Good Genes Sexual Selection Theory

In order to adequately characterize the evolution of reproductive strategies, one must consider parental investment theory in conjunction with other middle-level theories of sexual selection. In this section we provide a detailed overview of good genes sexual selection theory, as well as briefly summarize the three other main theories of sexual selection (via direct phenotypic benefits, runaway processes, and sensory bias).

The male long-tailed widowbird, as its name suggests, has an extraordinarily elongated tail. Although the body of this EastAfrican bird is comparable in size to that of a sparrow, the male’s tail feathers stretch to a length of up to 1.5 meters during the mating season. These lengthy tail feathers do little to enhance the male widowbird’s survival prospects: They do not aid in flight, foraging, or defense from predators. Indeed, having to haul around such a tail is likely to reduce survival prospects through increased metabolic expenditure, attraction of predators, and the like. The question that has to be asked of the male widowbird’s tail is how it could possibly have evolved. The short answer is that female widow birds prefer males with such exaggerated traits—that is, the male widowbird’s extraordinary tail has evolved by the process of sexual selection. That such a female preference for long tails exists was confirmed in an ingenious manipulation experiment carried out by Malte Andersson (1982). In this study, some males had their tail feathers experimentally reduced while others had their tails enhanced.The number of nests in the territories of the males with the supernormal tails significantly exceeded the number of nests in the territories of those males whose tails had been shortened. Clearly female widowbirds preferred to mate with males who possess the superlong tails.

To explain why the female widowbird’s preference for long tails has evolved, we need to consider the various mechanisms and theories of sexual selection. The two main mechanisms of sexual selection that have been identified are mate choice (usually, but not always, by females) and contests (usually, but not always, between males). The male widowbird’s elongated tail is an example of a trait that has apparently evolved via female choice. The 2.5-m tusk of the male narwhal, by contrast, is a trait that appears to have evolved in the context of male-male competition. Other, less studied mechanisms of sexual selection include scrambles for mates, sexual coercion, endurance rivalry, and sperm competition (Andersson, 1994; Andersson & Iwasa, 1996). In his exhaustive review of sexual selection in over 180 species, Andersson (1994) documents evidence of female choice in 167 studies, male choice in 30 studies, male competition in 58 studies, and other mechanisms in 15 studies. Sexual selection, as illustrated in a recent book by Geoffrey Miller (2000), has also been proposed as an important mechanism for fashioning many traits in our own species, including such characteristics as music, art, language, and humor.

Four main theories about how sexual selection operates have been advanced: via good genes, direct phenotypic benefits, runaway processes, and sensory bias. These different theories, however, are not necessarily mutually exclusive and may be used together to explain the evolution of sexually selected traits. The core idea of good genes sexual selection is that the outcome of mate choice and intrasexual competition will be determined by traits that indicate high genetic viability (Andersson, 1994; Williams, 1966). Males (and, to a lesser extent, females) of many bird species, for example, possess a bewildering variety of ornaments in the form of wattles, plumes, tufts, combs, inflatable pouches, elongated tail feathers, and the like. Moreover, many male birds are often splendidly attired in a dazzling array of colors: iridescent blues, greens, reds, and yellows. Keeping such elaborate visual ornamentation in good condition is no easy task. It requires time, effort, and—critically—good health to maintain. Females who consistently choose the brightest, most ornamented males are likely to be choosing mates who are in the best condition, which reflects the males’ underlying genetic quality. Even if females receive nothing more than sperm from their mates, they are likely to have healthier, more viable, and more attractive offspring if they mate with the best quality males. According to Hamilton and Zuk (1982), bright plumage and elaborate secondary sexual characteristics, such as the male peacock’s resplendent tail, are accurate indicators of the relative parasite loads of different males. A heavy parasite load signals a less viable immune system and is reflected in the condition of such traits as long tail feathers and bright plumage.

Many secondary sexual characteristics therefore act as indicators of genetic quality. Moreover, according to the handicap principle developed by Amotz Zahavi (1975; Zahavi & Zahavi, 1997), such traits must be costly to produce if they are to act as reliable indicators of genetic worth. If a trait is not expensive to produce, then it cannot serve as the basis for good genes sexual selection because it will not accurately reflect the condition of its owner. However, if the trait relies on substantial investment of metabolic resources to develop—as does the male widowbird’s tail—then only those individuals in the best condition will be able to produce the largest or brightest ornament. In this case, expression of the trait will accurately reflect underlying condition.

In a slightly different take on the handicap principle, Folstad and Karter (1992) have suggested that in males, high levels of testosterone, which are necessary for the expression of secondary sexual characteristics (those sex-linked traits that are the product of sexual selection), also have harmful effects on the immune system. According to this immunocompetence handicap model, only the fittest males will be able to develop robust secondary sexual characteristics, which accurately indicate both high levels of testosterone and a competent immune system—and therefore high genetic quality. These general hypotheses were supported in a recent metaanalysis of studies on parasite-mediated sexual selection. This meta-analysis demonstrated a strong negative relationship between parasite load and the expression of male secondary sexual characteristics. In total, the most extravagantly ornamented individuals are also the healthiest ones—and thus the most preferred as mates (Moller, Christie, & Lux, 1999). Of course in species in which there is substantial paternal investment (including humans), males will also be choosy about whom they mate with and will also select mates with indicators of high genetic fitness. In many bird species, for example, both males and females are brightly colored or engage in complex courtship dances. Thus, relative levels of parental investment by males and females substantially influence the dynamics of good genes sexual selection.

Genes, of course, are not the only resources that are transferred from one mate to another in sexually reproducing species.Although the male long-tailed widowbird contributes nothing but his sperm to future offspring, in many species parental investment by both sexes can be substantial. It benefits each sex, therefore, to attend to the various resources that mates contribute to subsequent offspring; thus, one of the driving forces behind sexual selection is the direct phenotypic benefits that can be obtained from mates and mating. These benefits encompass many levels and types of investment— from the small nuptial gifts offered by many male insect species to the long-term care and provisioning of offspring.