An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Development of Mastery during Adolescence: The Role of Family Problem Solving *

A sense of mastery is an important component of psychological health and well-being across the life-span; however, relatively little is known about the development of mastery during childhood and adolescence. Utilizing prospective, longitudinal data from 444 adolescent sibling pairs and their parents, our conceptual model proposes that family SES in the form of parental education promotes effective family problem solving which, in turn, fosters adolescent mastery. Results show: (1) a significant increase in mastery for younger and older siblings, (2) parental education promoted effective problem solving between parents and adolescents and between siblings but not between the parents themselves, and (3) all forms of effective family problem solving predicted greater adolescent mastery. Parental education had a direct effect on adolescent mastery as well as the hypothesized indirect effect through problem solving effectiveness, suggesting both a social structural and social process influence on the development of mastery during adolescence.

Mastery, defined as a sense of having control over the forces that affect one’s life, is an important component of psychological health and well-being across the life-span (e.g., Mirowsky and Ross 1999 ; Pearlin et al. 1981 ; Shanahan and Bauer 2004 ; Thoits 1995 ). Research across multiple domains and ages documents a linkage between a sense of control and individual differences in mental and physical health (e.g., Lin and Ensel 1989 ; Pearlin and Schooler 1978 ; Thoits 1995 ). For example, Mirowsky and Ross (1998) find that personal control is associated with a healthier lifestyle. Rosenfield (1989) finds that personal control in the workplace is linked to better mental health. Keyes and Ryff (1998) include ‘environmental mastery’ (managing the demands of daily life) as one of six dimensions of psychological well-being in adulthood. In a review of control-related concepts, Skinner (1996) states “a sense of control is a robust predictor of physical and mental well-being” (549), and for some, perceived control is viewed as a “more powerful predictor of functioning than actual control” (551). Thus, whether labeled mastery, personal control, perceived control or environmental mastery, a sense of mastery is seen as central to how well individuals respond to challenges and situations encountered in everyday life 1 .

In particular, mastery is considered part of an individual’s array of personal resources that enables a person to weather negative life events and other stressful conditions, such as job loss, economic pressure, and relationship problems ( Conger and Conger 2002 ; Mirowsky and Ross 2003 ; Pearlin et al. 1981 ; Wheaton 1985 ). Indeed, “people with high self-esteem and a sense of personal control may have the skills to avoid or prevent negative events or chronic difficulties” ( Thoits 1995 : 62). Conger and Conger (2002) found that adults rated high on mastery actually demonstrated decreasing economic problems over time. Furthermore, mastery may promote good social functioning as demonstrated by a more rewarding job, a healthier lifestyle, and more satisfying relationships, (e.g., Pulkinnen, Nygren, and Kokko 2002 ; Rosenfield 1989 ). Thus, mastery appears to function as an important personal attribute that is both an indicator of positive adaptation and a resource that promotes individual well-being in adulthood.

Despite its central role in people’s lives, there is little understanding of how mastery develops. Such understanding is essential if this important characteristic is to be promoted in an effort to foster individual health and well-being. The limited knowledge regarding the development of mastery likely results from the fact that most studies linking control, stress, and mental health have focused primarily on the adult years (see Avison and Gotlib 1994 , Eckenrode and Gore 1990 ; Thoits 1995 , 2006 ). However, research is increasing on adolescent health and well-being and its implications for adult development (e.g., Colten and Gore 1991 ; Hauser and Bowlds 1990 ; Schulenberg, Maggs, and Hurrelmann 1997 ). For example, Lewis, Ross and Mirowsky (1999) propose that children from higher SES homes will develop a greater sense of control as they move into adulthood due in part to the higher level of problem solving and life skills they develop in such family environments. This view is consistent with a life course perspective which suggests that individual development unfolds in the context of family interactions and family socioeconomic circumstances ( Caspi 2002 ; Elder, 1998 ). The life course notion involving “linked lives” proposes that parents may help their children make good choices (i.e., become more effective agents of change in their own lives) through the acquisition of constructive problem solving strategies. The current study adds to this research by examining the developmental course of mastery during adolescence and the importance of family characteristics and interactions for such development.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF MASTERY

Development of mastery over self and social situations is a key element of the self-exploration and self-evaluation that takes place during the adolescent years (e.g., Demo and Savin-Williams 1983 ; Feldman and Elliott 1990 ; Harter 1999 ; Masten et al. 1995 ). Adolescents increasingly take on new social roles as peers, co-workers, and romantic partners, and must develop a sense of control during social interactions. In these roles they are expected to handle challenges and situations that arise in multiple domains such as school, work, and family where interpersonal interactions take place ( Caspi 2002 ; Colten and Gore 1991 ; Gecas and Seff 1990 ; Mortimer and Larson 2002 ). We expect that the quality and consequences of these interactions significantly influence adolescent mastery. Indeed, Lewis and colleagues ( 1999 :1575) propose that, “An individual learns through social interaction and personal experience that his or her choices and efforts are usually likely or unlikely to affect the outcome of a situation.” Consistent with this idea, when adolescents learn that their efforts will affect the course of events and may resolve difficulties in interpersonal relationships, their sense of mastery should increase.

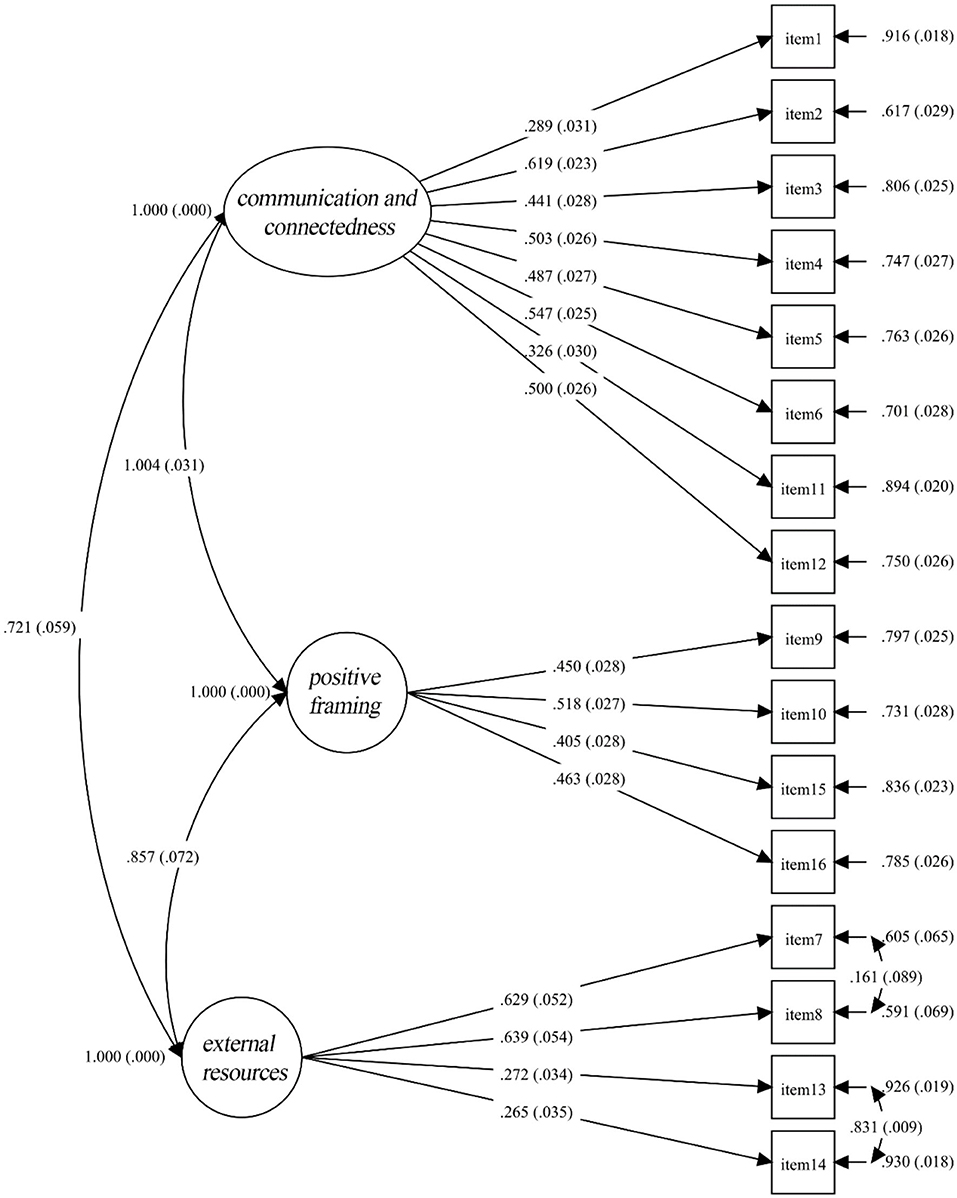

Based on this hypothesis that mastery is acquired in part through social interactions and their outcomes, we propose that social processes in the family significantly influence the development of mastery. We hypothesize that the interactions and negotiations that occur within the family help socialize adolescents’ mastery, and a key dimension of this socialization process involves the nature of family problem solving interactions. Also important and consistent with the life course perspective, however, is the fact that a parent’s approach to socialization practices and problem solving strategies will be influenced by their place in broader social structures. One important marker of socioeconomic status (SES) involves parents’ education, which serves as the single exogenous variable in the conceptual model that guides this study ( Figure 1 ).

THE CONCEPTUAL MODEL

Parents’ education serves as the starting point for the conceptual model because it is an important component of SES that helps identify a family’s social class or position, and social class has been linked to the socialization practices of parents and strategies for handling conflicts in social relationships ( Conger and Dogan 2007 ; Gecas 1979 ; Oakes and Rossi 2003 ). Research suggests that individuals from higher SES backgrounds may have more flexibility and more resources to deal with problems as they arise (e.g., Kohn and Schooler 1982 ; Pearlin et al. 1981 ). Mirowsky and Ross (2003) state that education is the key factor for understanding the link between SES and psychological well-being. For example, people with higher levels of education tend to have greater skills to solve complex problems, jobs with more autonomy and creativity, and more opportunities to make decisions. Parent education also plays an important role in promoting self control as children transition into adulthood ( Lewis et al. 1999 ).

Bradley and Corwyn (2002) suggest that parental education may be the most important marker of SES in terms of socialization practices and child adjustment. Education enables a person to acquire the knowledge and skills (i.e., human capital) that may influence parents’ strategies for childrearing. We would expect, therefore, that more years of education will predict more effective strategies for handling problems that arise between parents and adolescents ( Cox and Paley 1997 ). Based on this reasoning, Figure 1 proposes that (1) parents with more education will engage in more effective problem solving strategies in marital and parent-child interactions, and (2) parental education will positively impact problem solving interactions between siblings as a result of observing more highly skilled parents (see Bandura 1997 ). It is through these interaction processes that family SES indirectly promotes a sense of mastery for adolescents.

Next we build on research which suggests that experiences with parents may play an important role in children’s development of mastery and self-confidence (e.g., Gecas 1989 ; Whitbeck et al. 1997 ). Parents are viewed as the primary agents of socialization through daily interactions (e.g., Demo and Cox 2000 ; Hokoda and Fincham 1995 ). A particularly salient aspect of family interactions for the development of mastery may be conflict resolution or problem solving interactions. Our conceptual model proposes that problem solving interactions within family subsystems (marital, parent-child, sibling) serve as key contexts in which children observe, learn, and practice skills associated with managing problems (e.g., Rinaldi and Howe 2003 ; Rueter and Conger 1998 ; Shantz and Hobart 1989 ).

Research on marital conflict suggests hostility and anger between spouses may have a direct, negative effect on children’s adjustment (e.g., Cummings and O’Reilly 1997 ). When parents fail to amicably resolve conflicts, children will suffer reduced psychological well-being and, presumably, a poorer sense of mastery. Furthermore, poor relationships between parents may create problems between siblings (see Conger and Conger 1996 ) and between parents and children (e.g., Fauber and Long 1991 ; Reese-Weber 2000 ). That is, when marital problem solving skills are compromised, so too are parent-child and sibling problem solving skills; consistent with the paths shown in the conceptual model.

Regarding the parent-child subsystem, we expect that adolescents learn communication skills and strategies such as negotiation and compromise during problem solving interactions with their parents (e.g., Barber 2002 ; Noller et al. 2000 ). Adolescents who perceive their parents as supportive and fair should be more accepting of parental suggestions (e.g., Davies and Cummings 1994 ; Whitbeck et al. 1991 ). Furthermore, constructive, compared to destructive, interactions may impart a sense of confidence about handling problem situations, and promote feelings by parents and children that they can effectively deal with mutual concerns and problems ( Rueter and Conger 1998 ). These feelings of effectiveness are expected to lead to increased mastery for adolescents.

Interactions with siblings also may contribute to the development of mastery. Unlike interactions with parents, which are by definition hierarchical, interactions between adolescent siblings may be more egalitarian due to their more similar stages of verbal, cognitive, and social development ( Furman and Lanthier 1996 ; McGuire et al. 2000 ). Furthermore, adolescent siblings are expected to emulate their parents’ problem solving strategies, and when these strategies effectively resolve disagreements, adolescents will experience increased mastery in dealing with daily difficulties.

The model conceptualizes problem solving as an important skill that is acquired over time and affected by family experiences. Specifically, adolescents exposed to constructive problem solving experiences in multiple family relationships should learn to resolve problems as they arise, contributing to a sense of mastery. Such experiences stand in sharp contrast to letting problems develop into larger, unmanageable difficulties that intensify feelings of helplessness and impede positive mastery development (see Thoits 1994 ). In the following analyses, we empirically evaluate the causal paths proposed in the conceptual model, and consider related issues that may modify or extend the basic conceptual framework.

RELATED RESEARCH ISSUES

Over time adolescents increasingly become active agents in their widening social world, striving to develop an increasing sense of mastery as they assert their place in the family and autonomy from parents (e.g., Barber 2002 ; Steinberg 1990 ; Thoits 2006 ). Thus, chronological age is one factor that determines mastery (e.g., Chubb, Fertman and Ross 1997 ). Another factor is the participation of adolescents in decisions that affect their lives ( Liprie 1993 ). Most parents increasingly involve their adolescents in decisions that concern them, such as buying clothing, family activities, and weekend curfews ( Bulcroft, Carmody, and Bulcroft 1996 ; Conger, Conger, and Scaramella 1997 ). For most individuals then, we would expect to see mastery increasing over the course of adolescence due, in part, to age as well as to experiences in multiple social relationships and situations.

In addition to the effect of age and experience, gender may be associated with the developmental course of mastery. For example, parents typically place fewer restrictions on the behaviors and activities of adolescent boys compared to girls due to concerns about personal safety, sexual activity, and deviant peers ( Brown and Huang 1995 ). Lewis et al. (1999) found that girls, on average, reported a lower sense of control than boys; they suggest that boys perceive a higher sense of control compared to girls as males are typically considered to be an ‘advantaged group’ in American culture. In addition, girls tend to have a “somewhat more dependent relationship with parents during adolescence” ( Brown and Huang 1995 : 154), which may inhibit the sense of control for adolescent females. However, results from other studies of mastery and control, have reported either no effects or inconsistent results related to gender (see Chubb et al. 1997 ; Whitbeck et al. 1997 ). Based on these findings and the fact that gender might modify the impacts of the processes proposed in the conceptual model, we take gender into account in the following analyses.

Participants

The present investigation included a total of 444 adolescent sibling dyads and their parents participating in a study of family functioning and adolescent adjustment in rural Iowa. In 1989, each family included two parents, a seventh grade adolescent (the target), and a sibling within 4 years of age, either younger or older (69% of the pairs were within 2 years of age). For the present study, one of the two siblings in the dyad is treated as the younger sibling (mean age = 13.52 years, range = 10.4 to 15.58); and one as the older sibling (mean age = 15.39 years, range = 13.00 to 18.92). The younger sibling sample was 45% female and older sibling sample was 51% female.

Families were recruited from eight counties in North Central Iowa; 78% of those eligible agreed to participate. Given the ethnic composition of rural Iowa at that time, all families were of European origin. Parents completed 13.52 years of school on average; the range was 10 th grade to post-graduate work. Average per capita income was $8,475, comparable to that observed for two-parent, white families in the United States in 1988 ( U. S. Bureau of the Census, 1989 ).

Interviewers visited each family’s home annually from 1989 (Wave 0) to 1992 (Wave 3). Two 2-hour visits, about two weeks apart, were conducted each year. During the first visit, the four family members completed a set of questionnaires. During the second visit, family members participated in four videotaped interaction tasks which are not used in these analyses. See Conger and Elder (1994) for additional details regarding the study. All cases with at least one wave of data during those years were included in the analyses; 92% of the original sample participated in 1992. In order to preserve the time ordering of the data, we used mastery data for both siblings from 1990 to 1992 (Waves 1, 2, and 3) and used data for the family problem solving variables from 1989 to 1991 (Wave 0, 1, and 2), a one-year lag.

Parent education

The measure was calculated as the average years of school completed by mother and father as of 1989 (Wave 0), the first year of the study. The combined average education was 13.52 years.

We used the 7-item scale developed by Pearlin et al. (1981) ; mastery was defined as “the extent to which people see themselves as being in control of the forces that importantly affect their lives” (p. 340). Each sibling independently responded, 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree , to items such as “I have little control over the things that happen to me”; “What happens to me in the future mostly depends on me”; and “There is little I can do to change many of the important things in my life”. The average score was used; items were coded so a high score indicated high mastery. Internal consistency ranged from α = .67 in early to α = .80 in later adolescence.

Problem solving behavior in family dyads

Problem solving (PS) was measured in three family subsystems: marital, parent-child, and sibling, using a measure created for this study ( Conger, 1989 ). For sibling PS , the younger sibling reported on his or her older sibling’s behaviors and the older sibling reported on the younger sibling’s PS behaviors. The question prompted, “Now think about what usually happens when you and your sibling have a problem to solve. Think about what your sibling does.” Questions asked how often the sibling: “listened to your ideas”; “just seemed to get angry”; “had good ideas about how to solve the problem”; “criticized you or your ideas”; “showed real interest in helping to solve the problem”; “blamed others”; “insisted that you agree with him or her”; and “changed his or her point of view to help solve the problem”. Participants answered 14 questions, 1 = always to 7 = never , about behaviors their sibling demonstrated when attempting to solve a problem. Typical problems between siblings involved personal items, chores, sharing the bathroom or the computer, and interpersonal style. All items were coded such that a higher score indicated more positive PS behaviors.

Problem solving measures for parent-child and marital dyads were constructed in the same fashion; each person responded to the same set of 14 questions worded specifically for that dyad. For marital PS , wives reported on their husbands’ behaviors and husbands reported on wives’ behaviors and these reports were averaged together for a measure of overall marital PS. For parent-child PS , each child reported on the behavior of first mother and then father (comparable data on parent report on each child was not available); reports were averaged together for a younger sibling report on parents’ PS and an older sibling report of parents’ PS. Cronbach’s alpha for the 14 item PS scale was greater than α = .81 for each dyad type across the years of the study.

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics for the study variables. As expected, the mean level of mastery increased across time (i.e., by age) for older (3.84 to 3.96) and younger siblings (3.86 to 3.93 on a scale of 5). The time-varying covariates for parent-child and sibling -child PS interactions are shown as the mean level averaged across three measurement occasions (Wave 0, 1, and 2). Correlations (available from the first author) among the study variables were in the expected direction and were consistent with the hypothesized associations.

Means and Standard Deviations for Study Variables

Note. Sample = 444 sibling pairs (888 adolescents) in 1989 (Wave 0); 92% of the original sample participated in 1992 (Wave 3)

Analytic Approach to Model Testing

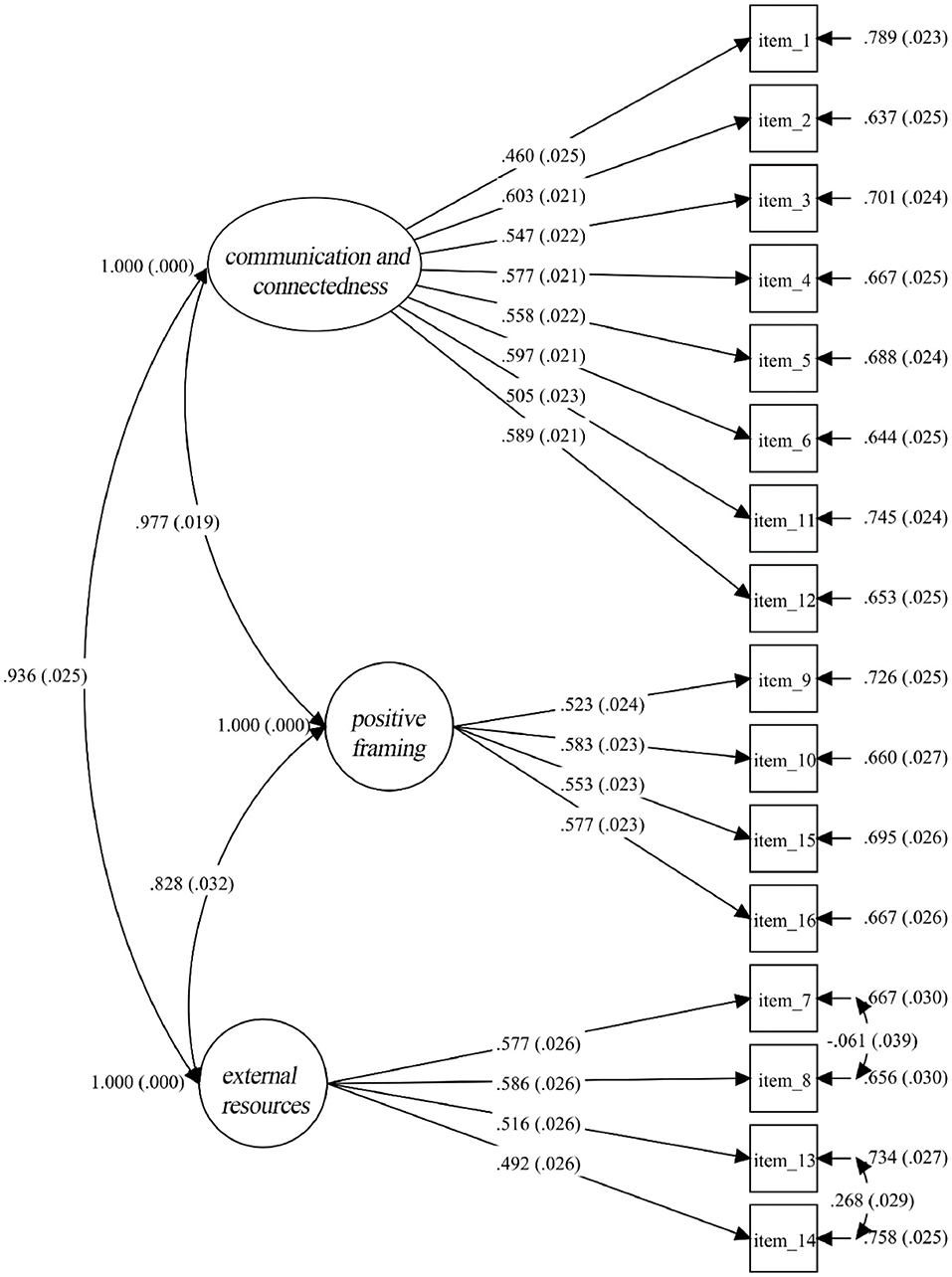

Hypothesis testing involved a model building process as illustrated in Figure 2 . First, a bivariate unconditional growth model of younger and older sibling mastery was examined. Results (not shown) indicated that both older and younger siblings demonstrated significant variability in their levels (intercepts) of mastery, and there was evidence of growth; therefore estimation of subsequent models with predictors was warranted. The intercept factor for the younger sibling growth model was centered at age 13, and for the older sibling growth model it was centered at age 15, the approximate mean ages in 1990 (Wave 1). While data collection occurred on an approximate yearly basis, mastery over time was modeled as a function of chronological age (in years), utilizing the exact age at each wave of data collection for each adolescent in the sample. For the three-year study period, ages of younger siblings ranged from 10 to 19 years and ages for older siblings ranged from 13 to 21 years. Thus, although the analytic model ( Figure 2 ) appears to suggest that all adolescents were measured at the same three measurement occasions, each adolescent was actually measured at a unique point in time, contributing a minimum of one and a maximum of three measurement points (92% had three points). Growth models are designed to handle this type of unbalanced data ( Bryk and Raudenbush 1992 ), an advantage that allows the current study to model trajectories of mastery on a time scale of chronological age rather than calendar time.

The analytical model showing the associations between parents– education, marital problem-solving, parent-child problem-solving, and sibling problem-solving and adolescent mastery over time (age) controlling for sibling gender

This approach maps on to a traditional hierarchical linear model or linear mixed model and we use the “Level I/II” notation for the equations that follow where Level I represents the within individual variability across time and Level II represents the between individual variability. However, Figure 2 reflects the fact that we specified our growth models in a larger latent variable framework using the Mplus software ( Muthén and Muthén, 2006 ) that allowed us to estimate the growth models for the older and younger siblings simultaneously along with the path analysis relating the various predictors both directly and indirectly to the growth processes.

In the unconditional growth model and all subsequent models, the intercept factors for younger and older siblings were allowed to covary freely, to compensate for the shared variance between the two siblings within each family ( Khoo and Muthén, 2000 ). Both a linear and quadratic growth factor were included in each growth curve model but no random effect was estimated for the quadratic term because no individual child had more than three occasions of measurement. However, since there was a significant quadratic fixed effect for age in the younger sibling growth model, the quadratic factor with zero variance was retained in both the older and younger sibling models for comparison. It was possible to estimate a random linear effect of age but because of the small amount of variability in that effect, all covariances with the two linear slope factors were fixed to zero. The variance structure of random effects (growth factors) for the older and younger sibling models of change in mastery as a function of age is displayed in the Level II equation given below.

Once the effect of age was taken into account (see Level I equations), the family PS variables were added to the model as lagged time-varying predictors. Time-varying predictors are allowed to take on different values at each measurement occasion, but the effects of these time-varying predictors were assumed to be constant over time ( Bryk and Raudenbush, 1992 ). The present model therefore captures year-to-year fluctuations in parent-child and sibling-child PS, while estimating time-invariant effects. Consistent with the conceptual model ( Figure 1 ), the effects of marital PS were modeled as both direct effects on observed mastery at each year, and as indirect effects on mastery through parent-child and sibling-child PS. We also modeled the hypothesized indirect effects of parents’ education on mastery through parent-child and sibling-child PS as well as through marital PS. Finally, for comparison purposes, we estimated the direct effects of parents’ education on mastery at each year.

Initially, the effects of PS (marital, parent-child, and sibling) and parents’ education on mastery were allowed to differ for younger siblings and older siblings. Then, a series of constraints were included to test whether the effects of the variables within each dyad on mastery could be considered equivalent for younger and older siblings. Finally, gender of each sibling was added as a predictor of the intercept and linear growth factors, as indicated in the Level II equations. Thus, the effects of PS and parental education were estimated while controlling for age and gender.

The analytic model for the conditional parallel growth processes is given by the Level I and II equations below. In the interest of space, only the linear equations for the older sibling outcomes at Level I and random effects at Level II are given. The equations for the younger sibling are the same at Level II and at Level I differ only in that the centering for age is at 13 instead of 15.

Level I ( t = 1, 2, and 3 and i = 1,…, n=444):

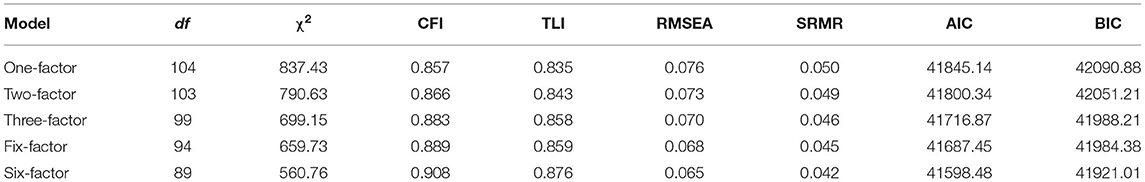

Results from Growth Modeling

Results for the final model are presented in Table 2 . All models were estimated using full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) under the missing-at-random (MAR) assumption with Mplus V4.0 ( Muthén and Muthén, 2006 ). The results are presented as unstandardized estimates of effects of predictors on growth in mastery. Initial results suggested the younger siblings have a somewhat faster rate of increase in mastery; however, when constrained to be equal, both younger and older siblings demonstrated comparable linear increases in their levels of mastery over time (b = .05). There was a small, significant, negative quadratic effect (b = −.02) in the trajectories of mastery for younger siblings, suggesting a slight deceleration or leveling off in growth of mastery. That is, growth in mastery could still be occurring but at a slower pace than earlier ages.

Conditional Growth Model with Unstandardized Path Analysis Results

LL = −7708.90, # of parameters = 101, n = 444 sibling pairs

Findings in Table 2 show that gender was marginally related to the intercept (b = −.09, p = .06) and was significantly related to the linear slope of mastery for younger, but not older, siblings. Specifically, younger girls demonstrated lower levels of mastery than boys at age 13 (b = −.09) but they increased in mastery at a faster rate over time (b=.05). Next we consider the associations among the hypothesized predictors and mastery. For the time-varying covariates involving family PS, we report a single coefficient for predictors because their effects are held to be equal over time. For example, the relationship between parent-child PS from wave 0 to mastery at wave 1 is constrained to be equal to the same association from wave 1 to wave 2.

Of the remaining covariates, only PS interactions with parents had a significantly different effect on mastery for younger compared to older siblings. For both younger and older siblings, positive PS interactions with parents predicted higher levels of mastery, with the expected change in mastery being larger for younger (b = .18) compared to (b = .11) older siblings. On the other hand, constraining the effects of sibling and marital PS and parents’ education on mastery to be equal for older and younger siblings did not significantly worsen model fit compared with allowing these effects to be freely estimated, based on a likelihood ratio test for nested models (χ 2 = 11.28, df = 7, p = .13) (see Singer and Willett, 2003). Thus, the results in Table 2 are presented with equality constraints for younger and older siblings for these predictors of mastery. Positive PS interactions with siblings equally predicted higher levels of mastery during each subsequent year for older and younger siblings (b = .04). Positive marital PS interactions had a significant positive direct effect (b = .06) on mastery as well as a positive indirect effect through parent-child (b = .03) and sibling interactions (b = .01). Similar results were found for parents’ education which has a significant direct effect on mastery (b = .02) with comparatively small indirect effects through parent-child, sibling-child, and marital PS.

Variations in the parent-child and sibling PS interactions were explained by PS interactions within the marital dyad and by parents’ education (e.g., b = .30 for marital PS predicting parent-child PS). We did not find a significant association between marital PS and parents’ education (b = −.01).

The present study evaluated a conceptual model which proposed that parental education would promote effective family problem solving interactions which, in turn, would foster mastery across the years of adolescence. In addition, we expected that mastery should increase with age and that gender might influence the development of mastery. We consider the findings from the study and their implications in turn.

The Role of Family SES

Consistent with the conceptual model ( Figure 1 ), parent education had an indirect effect on adolescent mastery through its positive association with effective PS interactions between parents and adolescents and between siblings. These results suggest that family social status in the form of parents’ education has a pervasive effect on family interactions that facilitate the development of mastery. Lewis and colleagues (1999) suggest that “better educated parents may … help their children develop skills and habits that make the children more effective” (1578). This tendency of better educated parents to engage in more effective socialization practices is consistent with research on childrearing strategies (e.g., Conger and Dogan 2007 ). Parental education also had a direct relationship with sibling problem solving; this may reflect a process whereby siblings adopt patterns of thought and action similar to those used by their parents.

In addition to the results predicted by the conceptual model, two findings deserve special mention. First, we found a significant direct effect of parents’ education on mastery; this suggests that family PS behaviors do not entirely account for the impact of family SES on the development of mastery. It is possible that if a wider variety of parenting behaviors had been included, the influence of parents’ education might have been largely attenuated. For example, a broader array of socialization practices involving control strategies, direct tutoring and affective processes not considered in this report may be influenced by parental education and also affect the development of mastery (e.g., Conger and Dogan 2007 ). Furthermore, the influence of parental education may be genetically mediated to some degree which could be addressed with a genetically informed research design ( Conger and Donnellan 2007 ). Finally, parental education likely affects the broader social environment to which the adolescent is exposed, and which may affect the development of mastery. These possibilities merit attention in future research.

Second, we did not find a direct effect of parents’ education on marital problem solving. On first reflection this result seems contradictory to the general arguments in the conceptual model. If better educated parents are more skillful and adaptive in handling family problems in a constructive and effective manner, why aren’t these skills reflected in their interactions with one another? The literature demonstrates a robust relationship between parental education and the socialization of children ( Conger and& Dogan 2007 ). In marriage, however, the findings appear to be more complex (see Faust and McKibben 1999 ). It may be that our measure of problem solving may not adequately capture the complexity of PS style between these long married couples (on average 17 years). They may have well developed styles for handling and avoiding problems. It could also be that parents at this stage of the life course are more child-focused and their interactions revolve around helping their offspring face the challenges of adolescence. Finally, the emotional tone expressed by the couples during PS interactions may be important to consider. Further study will be needed to see if these factors help explain the absence of a significant association between parental education and marital problem solving in the present report.

Family Problem Solving and the Development of Mastery

Consistent with expectations, effective marital PS predicted more effective PS interactions between parents and children and between siblings. Marital PS also had a significant indirect effect on adolescent mastery through its effect on PS in both the parent-adolescent and sibling family subsystems. These results are consistent with earlier studies that find an indirect effect of marital conflict on child adjustment through parent-child relations (e.g., Fauber and Long 1991 ; Reese-Weber 2000 ). Our findings extend this research, suggesting not only an indirect effect of marital interactions on adolescent outcomes through the parent-child dyad but also through the sibling dyad. The robust influence of marital PS is also reflected by its direct relationship with adolescent mastery; consistent with studies which find a direct effect of marital dynamics on child adjustment (e.g., Harold et al. 1997 ). These findings suggest that exposure to effective PS between parents indicates to adolescents that difficulties and disagreements can be resolved in relationships in general, thus giving them greater confidence that they can control events in their lives.

Also as predicted, effective PS interactions with parents were related to individual differences in mastery over time for both older and younger siblings. These results suggest that adolescents’ mastery increased when they felt listened to and had an active role in solving problems and making decisions. These findings also are consistent with earlier research documenting that children learn to resolve problems and negotiate solutions most effectively under conditions of warm and supportive family relations ( Davies and Cummings 1994 ; Little and Conger 2007 ; Rueter and Conger 1995b , 1998 ).

Problem solving with parents had a larger effect on younger compared to older siblings’ mastery, perhaps reflecting the fact that parents may provide less guidance to older siblings who are in their late teens and approaching the transition to adulthood. Support for this interpretation comes from previous research which finds that, as adolescents increasingly participate in decisions that affect their lives, their sense of control increases ( Conger et al. 1997 ; Liprie 1993 ; Bulcroft et al. 1996 ).

We also found that PS experiences with siblings explained unique variance in adolescent mastery, which provides new insight on the possible consequences of sibling conflict resolution. Previous studies with younger children have found that most sibling conflicts ended with parental intervention ( McGuire et al. 2000 ) or that siblings’ resolution strategies were inferior to those proposed by parents ( Tucker, McHale, and Crouter 2003 ). The results reported here, however, are supportive of the notion that adolescents’ positive PS interactions with their siblings contribute independently to their sense of mastery. Moreover, results from this study suggest that both older and younger siblings contribute to one another’s development of mastery across the years of adolescence. Future studies should examine reciprocal influences between siblings at different stages of development to further our understanding of this process.

Effects of Age and Gender

As expected, we found that mastery increased throughout adolescence for both older and younger siblings, consistent with prior research which finds that mastery increases with age ( Mirowsky and Ross 1998 , 1999 ). Younger siblings also demonstrated a slowing rate of change in mastery over time. It may be that these younger siblings experience an increase in mastery during early adolescence, when parents begin to grant them more autonomy but that the growth in mastery levels off somewhat as parents retain control over certain areas. In contrast, the rate of change for older siblings does not slow, perhaps reflective of an increasing sense of independence, particularly for those who have left home to attend school or start work. This would be consistent with findings by Lewis et al. (1999) who suggest that the sense of control increases significantly during the transition to adulthood.

Gender was not related to the intercept or rate of change in mastery for older siblings. However, for younger siblings gender was marginally associated with the level and significantly associated with linear growth of mastery. Female younger siblings indicated a slightly lower initial level of mastery (age 13) which may be related to several factors. First, a lower sense of mastery may be related to the generally lower levels of self -esteem that manifest themselves about the time that girls are undergoing the pubertal transition in early adolescence (e.g., Brooks-Gunn and Warren 1985 ; Harter 1990 ). Lower mastery in early adolescence also may be related to stressors encountered during other normative life course transitions such as changing schools, dating, and having conflicts with parents ( Call and Mortimer 2001 ; Colten and Gore 1991 ). However, we did not find this same gender difference for older siblings, thus mastery may increase as girls accommodate to the challenges of early adolescence. This interpretation is based in part on the significant interaction effect of age and gender that suggests that although younger sisters start lower, they demonstrate a higher average linear growth rate compared to that for younger brothers. That is, they tend to catch up with boys over time. This issue deserves further examination in future research.

Contributions, Limitations and Future Directions

This study advances earlier research by examining family influences on the development of mastery at an earlier age than has typically been done in previous research (e.g., Lewis et al. 1999 ). It also specifically investigated family influences that have been presumed to be important in earlier studies but were not directly examined (e.g., Lewis et al. 1999 ). In addition, it is one of the rare studies of mastery during the years of adolescence and the only study of which we are aware that considers sibling as well as parental influence on mastery. Taken together, the findings illustrate one set of processes through which family SES (education) promotes family interactions that advance the development of mastery during the adolescent years. Presumably these early advantages will lay the groundwork for a healthier individual more capable of successfully negotiating the stresses and strains that characterize the life course.

The present study makes promising contributions to our understanding of the links between family experiences and adolescent mastery; however, there are a few limitations that must be noted. Due to data analytic requirements, measures of both mastery and problem solving behaviors for parent-adolescent and sibling dyads employed adolescent self-report which may contribute to some shared method bias (see Lorenz et al. 1991 ). However, the use of independent reports from parents for their education and marital problem solving strengthened our confidence in the results presented here. That is, the associations among these variables cannot be attributed to reliance on a single informant. We were also somewhat limited by having only three time points for assessing adolescent mastery and problem solving interactions. However, the ability to analyze these data by the age of each respondent at each measurement occasion increased our ability to examine the nature of mastery over the second decade of life (i.e., 10 to 21 years of age as opposed to three calendar years, 1990–1992). Finally, we must be cautious in generalizing these results due to the homogeneous sample; however, we note that other findings from this panel study have been replicated in more diverse ethnic and cultural groups (e.g., R. Conger et al. 2002 ; Parke et al. 2004 ; Solantus, Leinonen, and Punamaki 2004 ), which increases our confidence in the potential generalizability of these results as well.

Although these results examined the effects of family problem solving on the development of mastery, it is also likely that a developing sense of mastery may impact a person’s approach to problem solving. That is, the process may be reciprocal, such as the reciprocal relationship between negative life events and young adult mastery found by Shanahan and Bauer (2004) . One can imagine a scenario in which adolescents with higher mastery are more willing to engage in problem solving interactions, which in turn contribute to an increase in their mastery and self confidence (see Pulkinnen et al. 2002 ; Thoits 2006 ). This is consistent with the idea that mastery develops through personal experiences and social interactions ( Skinner 1996 ). Furthermore, adolescents who have more successful problem solving experiences may become better at selecting themselves out of situations where conflicts and negative events may occur (see Thoits 2006 ). Future research would benefit from an examination of the reciprocal effects of mastery and problem solving over multiple time points and in multiple settings across the life course.

The present findings could also have important implications for adolescents’ relationships with peers and romantic partners. In families with high levels of recurring or unresolved conflict, adolescents’ mastery may suffer from repeated failures in conflict resolution ( Forgatch 1989 ; Rueter and Conger 1995a ). These adolescents may feel less confident about resolving problems in close relationships when difficulties arise ( Rosenfield 1989 ; Rueter and Conger 1995b ). An important extension of the present study will be to examine how problem solving experiences in the family of origin and adolescent mastery combine to affect the ability to make a successful transition to adulthood by fostering better relationships with peers, co-workers, romantic partners and one’s own children. Although a small number of studies have begun to examine these issues (e.g. Lewis et al. 1999 ; Rosenfield 1989 ), a great deal of research remains to develop a richer understanding of how family processes and individual mastery affect a successful transition to adulthood.

As noted at the beginning of this article, a long history of empirical research has established the role of mastery in the maintenance of health and well-being during the adult years. The importance of mastery as an individual attribute of great significance is beyond question. With a few exceptions (e.g. Lewis et al. 1999 ), what has been lacking has been research that provides a clear understanding of how family social position and social dynamics foster the development of a strong sense of mastery. With such understanding, social services and policies can be advanced that will promote growth in mastery in subsequent generations of young people. If the results of this study are replicated and extended to more diverse populations, they suggest that social policies which increase educational quality and availability to all members of our society should promote individual mastery and social processes that foster the development of this attribute. The results also suggest specific, mastery-enhancing skills that might be taught to families with regard to the way they handle difficulties and disagreements. Simply put, while the present findings shed theoretical light on the issues investigated, they may also have applied significance of real social importance.

Biographies

Katherine Jewsbury Conger is an Associate Professor in Human Development and Family Studies at the University of California, Davis. Her research focuses on the impact of economic stress on family functioning with a special emphasis on sibling relationships and adolescent health and well being.

Shannon Tierney Williams is a research associate with the University of California, Davis and Zetetic Associates. Her research focuses on the importance of children's interpersonal relationships within the context of families, child care settings, and schools from infancy through adolescence.

Wendy M. Little is a doctoral candidate in Human Development at the University of California, Davis. Her research focuses on family processes, sibling relationships and individual adjustment during adolescence and emerging adulthood.

Katherine Masyn is an Assistant Professor at the University of California, Davis. Her research focuses on the development, refinement, and application of latent variable models for understanding population heterogeneity in longitudinal processes such as growth trajectory, event history, and latent transition analyses.

Barbara Shebloski is a postdoctoral scholar with the Family Research Group and lecturer in Human and Community Development at the University of California, Davis. Her research focuses on parenting and sibling relationship quality, and factors related to continuity and change in intergenerational educational achievement.

* Current support comes from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute of Mental Health ( {"type":"entrez-nucleotide","attrs":{"text":"HD047573","term_id":"300616611"}} HD047573 , {"type":"entrez-nucleotide","attrs":{"text":"HD051746","term_id":"300619503"}} HD051746 , and {"type":"entrez-nucleotide","attrs":{"text":"MH051361","term_id":"1394622422"}} MH051361 ). Support for earlier years of the study came from multiple sources, including NIMH (MH00567, MH19734, MH43270, MH59355, MH62989, and MH48165), NIDA (DA05347), NICHD (HD027724), the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health (MCJ-109572), and the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Adolescent Development Among Youth in High-Risk Settings. We thank Peggy Thoits, Eliza Pavalko and anonymous reviewers for constructive feedback on earlier versions of this paper.

1 Our study focuses specifically on mastery (personal control), and not self-efficacy. Although self efficacy, the belief that you can perform a specific behavior successfully or achieve a certain outcome falls under the larger umbrella of self-concept, as does mastery, it is a distinct concept and we do not address it in this study. We refer interested readers to the literatures on self-efficacy and self-concept (see Bandura 1997 and Harter 1999 respectively).

- Avison William R, Gotlib Ian H., editors. Stress and mental health: Contemporary issues and prospects for the future. New York, NY, US: Plenum Press; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bandura Albert. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman and Company; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barber Brian. Intrusive parenting: How psychological control affects children and adolescents. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002; 53 :371–399. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brooks-Gunn Jeanne, Warren Michelle P. The effects of delayed menarche in different contexts: Dance and nondance students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1985; 14 :285–300. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown Bradford B, Huang Bih-Hui. Examining parenting practices in different peer contexts: Implications for adolescent trajectories. In: Crockett LJ, Crouter AC, editors. Pathways through adolescence: Individual development in relation to social contexts. New Jersey: Erlbaum; 1995. pp. 151–174. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bryk Anthony S, Raudenbush Stephen W. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1992. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bulcroft Richard A, Carmody Dianne C, Bulcroft Kris A. Patterns of parental independence giving to adolescents: Variations by race, age, and gender of child. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996; 58 :866–883. [ Google Scholar ]

- Call Kathleen Thiede, Mortimer Jeylan T., editors. Arenas of Comfort in Adolescence: A Study of Adjustment in Context. New Jersey: Erlbaum; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- Caspi Avshalom. Social selection, social causation, and developmental pathways: Empirical strategies for better understanding how individuals and environments are linked across the life-course. In: Pulkinnen Lea, Avshalom Caspi., editors. Paths to successful development: Personality in the life course. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 281–301. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chubb Nancy H, Fertman Carl I, Ross Jennifer L. Adolescent self-esteem and locus of control: A longitudinal study of gender and age differences. Adolescence. 1997; 32 :113–129. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Colten Mary Ellen, Gore Susan., editors. Adolescent Stress: Causes and Consequences. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1991. [ Google Scholar ]

- Conger Katherine J, Conger Rand D, Scaramella Laura V. Parents, siblings, psychological control, and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1997; 12 :113–138. [ Google Scholar ]

- Conger Rand D. Problem solving scale. Ames: Iowa State University; 1989. Measure developed for the Iowa Youth and Families Project. [ Google Scholar ]

- Conger Rand D, Conger Katherine J. Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002; 64 :361–373. [ Google Scholar ]

- Conger Rand D, Conger Katherine J. Sibling relationships. In: Simons RL, editor. Understanding differences between divorced and intact families: Stress, interaction, and child outcomes. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1996. pp. 104–121. [ Google Scholar ]

- Conger Rand D, Dogan Shannon J. Social class and socialization in families. In: Grusec Joan, Hastings Paul., editors. Handbook of Socialization. New York: Guildford Press; 2007. pp. 433–460. [ Google Scholar ]

- Conger Rand D, Donnellan M Brent. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007; 58 :175–199. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Conger Rand D, Elder Glen HJ, Lorenz Frederick O, Simons Ronald L, Whitbeck Leslie B., editors. Families in troubled times: Adapting to change in rural America. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- Conger Rand D, Wallace Lora E, Sun Yumei, Simons Ronald L, McLoyd Vonnie C, Brody Gene H. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002; 38 :179–193. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Conger Rand D, Cui Ming, Bryant Chalandra M, Elder Glen HJ. Competence in early adult romantic relationships: A developmental perspective on family influences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000; 79 :224–237. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cox Martha J, Paley Blair. Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology. 1997; 48 :243–267. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cummings EM, O'Reilly Anne Watson. Fathers in family context: Effects of marital quality on child adjustment. In: Lamb ME, editor. The role of the father in child development. 3rd ed. John Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1997. pp. 49–65. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davies Patrick T, Cummings E Mark. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994; 116 :387–411. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Demo David H, Cox Martha J. Families with young children: A review of research in the 1990s. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 2000; 62 :876–895. [ Google Scholar ]

- Demo David H, Savin-Williams Ritch C. Early adolescent self-esteem as a function of social class: Rosenberg and Pearlin revisited. American Journal of Sociology. 1983; 88 :763–774. [ Google Scholar ]

- Eckenrode John, Gore Susan., editors. Stress between work and family. New York, NY, US: Plenum Press; 1990. [ Google Scholar ]

- Elder Glen H., Jr The life course as developmental theory. Child Development. 1998; 69 :1–12. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fauber Robert L, Long Nicholas. Children in context: The role of the family in child psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991; 59 :813–820. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Faust Kimberly A, McKibben Jerome N. Marital dissolution: Divorce, separation, annulment, and widowhood. In: Sussman M, Steinmetz SK, Peterson GW, editors. Handbook of Marriage and the Family. 2nd edition. New York: Plenum Press; 1999. pp. 475–499. [ Google Scholar ]

- Feldman S Shirley, Elliott Glen R., editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. [ Google Scholar ]

- Forgatch Marion S. Patterns and outcomes in family problem solving: The disrupting effect of negative emotion. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1989; 51 :115–124. [ Google Scholar ]

- Furman Wyndol, Lanthier Richard P. Personality and sibling relationships. In: Brody GH, editor. Sibling relationships: Their causes and consequences. Westport, CT: Ablex Publishing; 1996. pp. 127–146. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gecas Viktor. The influence of social class on socialization. In: Burr WR, Hill R, Nye FI, Reiss IL, editors. Contemporary theories about the family. Vol. 1. New York: Free Press; 1979. pp. 364–404. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gecas Viktor, Seff Monica A. Social class and self-esteem: Psychological centrality, compensation, and the relative effects of work and home. Social Psychology Quarterly. Special Issue: Social Structure and the Individual. 1990; 53 :165–173. [ Google Scholar ]

- Harold Gordon T, Fincham Frank D, Osborne Lori N, Conger Rand D. Mom and dad are at it again: Adolescent perceptions of marital conflict and adolescent psychological distress. Developmental Psychology. 1997; 33 :333–350. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harter Susan. The construction of the self: A developmental perspective. New York: The Guilford Press; 1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- Harter Susan. Self and identity development. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 352–387. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hauser Stuart T, Bowlds Mary K. Stress, coping, and adaptation. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 388–413. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hokoda Audrey, Fincham Frank D. Origins of children's helpless and mastery achievement patterns in the family. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1995; 87 :375–385. [ Google Scholar ]

- Keyes Corey LM, Ryff Carol D. Generativity in adult lives: Social structural contours and quality of life consequences. In: McAdams DP, de St. Aubin E, editors. Generativity and adult development: How and why we care for the next generation. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1998. pp. 227–263. [ Google Scholar ]

- Khoo Siek-Toon, Muthén Bengt. Longitudinal data on families: Growth modeling alternatives. In: Rose JS, Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, editors. Multivariate applications in substance use research: New methods for new questions. Mahwah, New Jersey: Erlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 43–78. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kohn Melvin L, Schooler Carmi. Job conditions and personality: A longitudinal assessment of their reciprocal effects. American Journal of Sociology. 1982; 87 :1257–1286. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lewis Susan K, Ross Catherine E, Mirowsky John. Establishing a sense of personal control in the transition to adulthood. Social Forces. 1999; 77 :1573–1599. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lin Nan, Ensel Walter M. Life stress and health: Stressors and resources. American Sociological Review. 1989; 54 :382–399. [ Google Scholar ]

- Liprie Mary-Lou. Adolescents’ contributions to family decision making. Marriage and Family Review. 1993; 18 :241–253. [ Google Scholar ]

- Little Wendy, Conger Katherine J. Decision-Making Processes in Single-Parent Families and Adolescent Mastery. Boston, MA: Poster presented at biennial Meeting of Society for Research in Child Development; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lorenz Frederick O, Conger Rand D, Simon Ronald L, Whitbeck Leslie B, Elder Glen HJ. Economic pressure and marital quality: An illustration of the method variance problem in the causal modeling of family processes. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991; 53 :375–388. [ Google Scholar ]

- Masten Ann S, Coatsworth JD, Neemann Jennifer, Gest Scott D, Tellegen Auke, Garmezy Norman. The structure and coherence of competence from childhood through adolescence. Child Development. 1995; 66 :1635–1659. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McGuire Shirley, Manke Beth, Eftekhari Afsoon, Dunn Judy. Children's perceptions of sibling conflict during middle childhood: Issues and sibling (dis)similarity. Social Development. 2000; 9 :173–190. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mirowsky John, Ross Catherine E. Education, personal control, lifestyle and health: A human capital hypothesis. Research on Aging. 1998; 20 :415–449. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mirowsky John, Ross Catherine E. Well-being across the life course. In: Horwitz AV, Scheid TL, editors. A Handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 328–347. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mirowsky John, Ross Catherine E. Social Causes of Psychological Distress. 2nd ed. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mortimer Jeylan T, Larson Reed W., editors. The changing adolescent experience: Societal trends and the transition to adulthood. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

- Muthén Linda, Muthén Bengt. Mplus User’s Guide. 4th Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2006. [ Google Scholar ]

- Noller Patricia, Feeney Judith A, Sheehan Grania, Peterson Candida. Marital conflict patterns: Links with family conflict and family members' perceptions of one another. Personal Relationships. 2000; 7 :79–94. [ Google Scholar ]

- Oakes John M, Rossi Paul H. The measurement of SES in health research: Current practice and steps toward a new approach. Social Science and Medicine. 2003; 56 :769–784. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Parke Ross D, Coltrane Scott, Duffy Sharon, Buriel Raymond, Dennis Jessica, Powers Justina, French Sabine, Widaman Keith F. Economic Stress, Parenting, and Child Adjustment in Mexican American and European American Families. Child Development. 2004; 75 :1632–1656. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pearlin Leonard I, Menaghan Elizabeth G, Lieberman Morton A, Mullan Joseph T. The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981; 22 :337–356. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pearlin Leonard I, Schooler Carmi. The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1978; 19 :2–21. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pulkinnen Lea, Nygren Hille, Kokko Katja. Successful development: Childhood antecedents of adaptive psychosocial functioning in adulthood. Journal of Adult Development. 2002; 9 :251–265. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reese-Weber Marla. Middle and late adolescents' conflict resolution skills and siblings: Associations with interparental and parent-adolescent conflict resolution. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000; 29 :697–711. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rinaldi Christina M, Howe Nina. Perceptions of Constructive and Destructive Conflict Within and Across Family Subsystems. Infant and Child Development. 2003; 12 :441–459. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rosenfield Sarah. The effects of women's employment: Personal control and sex differences in mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989; 30 :77–91. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rueter Martha A, Conger Rand D. Antecedents of parent-adolescent disagreements. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995a; 57 :435–448. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rueter Martha A, Conger Rand D. Interaction style, problem-solving behavior, and family problem-solving effectiveness. Child Development. 1995b; 66 :98–115. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rueter Martha A, Conger Rand D. Reciprocal influences between parenting and adolescent problem-solving behavior. Developmental Psychology. 1998; 34 :1470–1482. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schulenberg John, Maggs Jennifer L, Hurrelmann Klaus., editors. Health risks and developmental transitions during adolescence. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shanahan Michael J, Bauer Daniel J. Developmental properties of transactional models: The case of life events and mastery from adolescence to young adulthood. Development and Psychopathology. 2004; 16 :1095–1117. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shantz Carolyn U, Hobart Cathy J. Social conflict and development: Peers and siblings. In: Berndt TJ, Ladd GW, editors. Peer Relationships in Child Development. Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. pp. 71–94. [ Google Scholar ]

- Singer Judith D, Willett John B. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- Skinner Ellen A. A guide to constructs of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996; 71 :549–570. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Solantaus Tytti, Leinonen Jenni, Punamäki Raija-Leena. Children's Mental Health in Times of Economic Recession: Replication and Extension of the Family Economic Stress Model in Finland. Developmental Psychology. 2004; 40 :412–429. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Steinberg Lawrence. Autonomy, conflict, and harmony in the family relationship. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. pp. 255–276. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thoits Peggy A. Stressors and problem-solving: The individual as psychological activist. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1994; 35 :143–160. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thoits Peggy A. Stress, Coping, and Social Support Processes: Where Are We? What Next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995:53–79. (Extra Issue) [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thoits Peggy A. Personal Agency in the Stress Process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006; 47 :309–323. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tucker Corinna J, McHale Susan M, Crouter Ann C. Conflict resolution: Links with adolescents' family relationships and individual well-being. Journal of Family Issues. 2003; 24 :715–736. [ Google Scholar ]

- U. S. Bureau of the Census. Money income and poverty status in the United States: 1988. Washington, DC: Department US of Commerce; 1989. Current Population Reports, Consumer Income (Series P-60, No. 166). [ Google Scholar ]

- Wheaton Blair. Models for the Stress-Buffering Functions of Coping Resources. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1985; 26 :352–364. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Whitbeck Les B, Simons Ronald L, Conger Rand D, Lorenz Frederick O. Family economic hardship, parental support, and adolescent self-esteem. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1991; 54 :353–363. [ Google Scholar ]

- Whitbeck Leslie B, Simons Ronald L, Conger Rand D, Wickrama KAS, Ackley Kevin A, Elder Glen H., Jr The effects of parents’ working conditions and family economic hardship on parenting behaviors and children’s self-efficacy. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1997; 60 :291–303. [ Google Scholar ]

Jump to navigation

- About Child Trauma

- Trauma Types

- Populations at Risk

- Trauma Treatments

- Screening and Assessment

- Psychological First Aid and SPR

- Core Curriculum on Childhood Trauma

- Trauma-Informed Systems

- Culture and Trauma

- Families and Trauma

- Family-Youth-Provider-Partnerships

- Secondary Traumatic Stress

- Trauma-Informed Organizational Assessment

- All NCTSN Resources

- Información en Español

- Public Awareness

- Structure and Governance

- Network Members

- Strategic Partnerships

- Policy Issues

- Position Statements

- About This Website

GET HELP NOW

Family Assessment Device

You are here, fad - family assessment device.

Based on the McMaster Model of Family Functioning (MMFF), the FAD measures structural, organizational, and transactional characteristics of families. It consists of 6 scales that assess the 6 dimensions of the MMFF - affective involvement, affective responsiveness, behavioral control, communication, problem solving, and roles - as well as a 7th scale measuring general family functioning. The measure is comprised of 60 statements about a family; respondents (typically, all family members ages 12+) are asked to rate how well each statement describes their own family. The FAD is scored by adding the responses (1-4) for each scale and dividing by the number of items in each scale (6-12). Higher scores indicate worse levels of family functioning.

The FAD has been widely used in both research and clinical practice. Uses include: (1) screening to identify families experiencing problems, (2) identifying specific domains in which families are experiencing problems, and (3) assessing change following treatment.

Epstein, N. B., Baldwin, L. M., Bishop, D. S. (1983). The McMaster family assessment device. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 9, (2), 171-180.

Available from the authors at the Family Research Program, Butler Hospital, 345 Blackstone Boulevard, Providence, RI 92906.

Administration

The FAD utilizes a 4 point Likert scale, with answer choices “strongly agree,” “agree,” “disagree,” and “strongly disagree.” Answers are coded 1 - 4 with higher numbers indicating more problematic functioning.

Parallel or Alternate Forms

The General Functioning Scale can be used as a brief stand-alone measure of family functioning (FAD-12). This scale/measure has solid psychometric properties.

Psychometrics

General family functioning: 2.00 Communication, affective responsiveness, problem solving: 2.20 Roles: 2.3 Behavior control: 1.9 Affective involvement: 2.10 (Epstein, Baldwin, & Bishop, 1983)

NOTES: In a study comparing mother vs. father scores, scores on 5 out of the 7 FAD scales were significantly correlated (Akister & Stevenson-Hinde, 1991). In a study exploring the use of the FAD with school age children, inter-rater reliability was calculated for 2 groups of mother-child dyads: those with a child aged 7 - 11 and those with a child aged 12 - 17. Young children’s FAD scores showed good agreement with maternal scores; scores on 6 out of the 7 FAD scales were significantly correlated. In contrast, older children’s scores on only 2 of the 7 scales significantly correlated with maternal scores. This suggests that, while some rater pairs demonstrate good inter-rater reliability, other raters have unique perspectives on family functioning. The authors suggest that this reflects the adolescent developmental stage as well as decreased physical proximity to the family as the child grows up (Bihun et al., 2002). Akister, J. & Stevenson-Hinde, J. (1991). Identifying families at risk: Exploring the potential of the McMaster Family Assessment Device. Journal of Family Therapy, 13, 411-421. Bihun, J.T., Wamboldt, M.Z., Gavin, L.A., & Wamboldt, F.S. (2002). Can the Family Assessment Device (FAD) be used with school aged children? Family Process, 41, 723-731. Epstein, N., Baldwin, L., & Bishop, D. (1983). The McMaster family assessment device. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 9, 19-31. Miller, I.W., Epstein, N.B., Bishop, D.S., & Keitner, G.I. (1985). The McMaster Family Assessment Device: Reliability and validity. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy, 11(4), 345-356.

Akister, J. & Stevenson-Hinde, J. (1991). identifying families at risk: Exploring the potential of the McMaster Family Assessment Device. Journal of Family Therapy, 13, 411-421. Clark, M.S., Rubenach, S., & Winsor, A. (2003). A randomized controlled trial of an education counseling intervention for families after stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation, 17, 703-712. Evans, R.L., Matlock, A.L., Bishop, D.S., Stranahan, S., & Pederson, C. (1988). Family intervention after stroke: Does counseling or education help? Fristad, M.A. (1989). A comparison of the McMaster and Circumplex family assessment instruments. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy, 15(3), 259-269. Kabacoff, R.I., Miller, I.W., Bishop, D.S., Epstein, N.B., & Keitner, G.I. (1990). A psychometric study of the McMaster Family Assessment Device in psychiatric, medical, and nonclinical samples. Journal of Family Psychology, 3(4), 431-439. Joffe, R., Offord, D., & Boyle, M. (1988). Ontario Child Health Study: Suicidal behavior in youth age 12-16 years. American Journal of Psychiatry, 145, 1420-1423. Maziade, M., Cote, R., Boutin, P., Bernier, H., & Thivierge, J. (1987). Temperament and intellectual development: A longitudinal study from infancy to four years. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 144-150. Miller, I.W., Epstein, N.B., Bishop, D.S., & Keitner, G.I. (1985). The McMaster Family Assessment Device: Reliability & validity. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy, 11(4), 345-356. Miller, I.W., Kabacoff, R.I., Epstein, N.B., Bishop, D.S., Keitner, G.I., Baldwin, L.M., et al. (1994). The development of a clinical rating scale for the McMaster Model of Family Functioning. Family Process, 33, 53-69. Tonge, B., Brereton, A., Kiomall, M., MacKinnon, A., King, N., & Rinehart, N. (2006). Effects on parental mental health of an education and skills training program for parents of young children with autism: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(5), 561-569.

Predictive Validity: clinical samples, nonclinical samples (Arpin, Fitch, Browne, & Corey, 1990; Bishop et al., 1987; Browne, Arpin, Corey, Fitch, & Cafni, 1990; Joffe et al., 1988; Maziade et al., 1985, 1987) Concurrent Validity: clinical samples, nonclinical samples (Miller, Epstein, Bishop, & Keitner, 1985; Miller et al., 1994) Sensitivity: Sensitivity and specificity were calculated based on clinician interview ratings matched with FAD assessments. FAD cutoffs have sensitivity rates of 57%-87%. The authors assert that these rates are similar to other assessments including some lab tests. (Miller, Epstein, Bishop, & Keitner, 1985) Specificity: Sensitivity and specificity were calculated based on clinician interview ratings matched with FAD assessments. FAD cutoffs have specificity rates of 64%-79%. The authors assert that these rates are similar to other assessments including some lab tests. (Miller, Epstein, Bishop, & Keitner, 1985) Arpin, K., Fitch, M., Browne, G., & Corey, C. (1990). Prevalence and correlates of family dysfunction and poor adjustment to chronic illness in speciality clinics. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 43, 373-383. Bishop, D., Evans, R., Minden, S., McGowan, M., Marlowe, S., Andreoli, N., Trotter, J., & Williams, C. (1987). Family functioning across different chronic illness/disability groups. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 68, 79-87. Brown, G., Arpin, K., Corey, P., Fitch, M., & Cafni, A. (1990). Individual correlates of health service utilization and the cost of poor adjustment to chronic illness. Medical Care, 28, 43-58. Joffe, R., Offord, D., & Boyle, M. (1988). Ontario Child Health Study: Suicidal behavior in youth age 12-16 years. American Journal of Psychiatry, 145, 1420-1423. Maziade, M., Caperaa, P., Laplante, B., Boudreault, M., Thivierge, J., Cote, R., et al. (1985). Value of difficult temperament among 7-year-olds in the general population for predicting psychiatric diagnosis at age 12. American Journal of Psychiatry, 142, 943-946. Maziade, M., Cote, R., Boutin, P., Bernier, H., & Thivierge, J. (1987). Temperament and intellectual development: A longitudinal study from infancy to four years. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 144-150. Miller, I.W., Epstein, N.B., Bishop, D.S., & Keitner, G.I. (1985). The McMaster Family Assessment Device: Reliability and validity. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy, 11(4), 345-356. Miller, I.W., Kabacoff, R.I., Epstein, N.B., Bishop, D.S., Keitner, G.I., Baldwin, L.M., et al. (1994). The development of a clinical rating scale for the McMaster Model of Family Functioning. Family Process, 33(1), 53-69.

(1) Some studies have called the FAD’s 7 factor structure into question. One study suggests that a 2 factor model (comprised of connection and commitment factors), rather than the 7 factor McMaster Model, provides a better fit for the data used to develop the FAD (Ridenour, Daley, & Reich, 1999). Cross-cultural research has also challenged the 7 factor structure of the FAD. However, rather than reflecting poorly on the original FAD, it is possible that these cross-cultural differences in factor structure reflect different cultural norms and expectations for family functioning. (2) The McMaster Model proposes that the 7 dimensions of family functioning are subsumed by an underlying health-pathology dimension; it follows that the 7 dimensions will be intercorrelated. This has led to criticism that the scales are not adequately independent and should not be considered discrete dimensions. (3) Acceptable psychometric properties have been demonstrated using primarily white, middle class samples; however, additional psychometric studies with racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse samples are warranted. (4) Additional psychometric research is essential to establish the reliability and validity of several of the FAD translations. (5) The FAD’s utility is limited by the lack of adequate standardization and norms.

Translations

Population information.

The FAD was developed using a sample of 503 individuals drawn from both the general U.S. population as well as various clinical populations. The sample included 209 undergraduate students, 9 advanced psychology students and their families, 6 families of patients in a stroke rehabilitation unit, 4 families with children in a psychiatric day hospital, and 93 families with an adult in a psychiatric hospital. The adult inpatient members represented a variety of diagnoses, including adjustment disorders, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, personality disorders, substance use disorders, schizophrenic disorders, somatoform disorders, and mental retardation. Demographic characteristics (i.e., race/ethnicity, gender, SES) of the development sample are not reported (Epstein, Baldwin, & Bishop, 1983).

Pros & Cons/References

(1) The FAD is based on the McMaster Model of Family Functioning, a multi-dimensional clinical model with constructs derived from clinical experience. (2) The FAD’s 6 domains (problem solving, communication, roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, and behavior control) and overall functioning domain provide a comprehensive picture of family functioning in multiple areas. (3) The FAD is a multi-informant assessment designed to be completed by all family members over age 12. This provides insight into multiple perspectives on family functioning. (4) The FAD has considerable clinical utility. The FAD and FAD-12 can be used to screen for families with problematic functioning; the FAD can also be used to identify specific areas of problematic family functioning and to assess changes post intervention.

(1) The FAD’s clinical utility is limited by the lack of a manual, adequate standardization, and instructions for interpreting multiple family member perspectives. (2) Historically, the FAD has been used primarily with white, middle-class families. Additional research with diverse racial/ethnic and socio-economic groups is needed to establish utility with these populations. (3) While the FAD has been translated into 14 languages, these translations have varying levels of reliability and validity and warrant further study. (4) The FAD scales are correlated with – rather than independent of – one another. Thus, families with problematic functioning in one area are likely to experience problems in other areas as well.