- Search the site GO Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Mental Health

- Social and Public Health

What Is Gender Affirmation Surgery?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/KP-Headshot-IMG_1661-0d48c6ea46f14ab19a91e7b121b49f59.jpg)

A gender affirmation surgery allows individuals, such as those who identify as transgender or nonbinary, to change one or more of their sex characteristics. This type of procedure offers a person the opportunity to have features that align with their gender identity.

For example, this type of surgery may be a transgender surgery like a male-to-female or female-to-male surgery. Read on to learn more about what masculinizing, feminizing, and gender-nullification surgeries may involve, including potential risks and complications.

Why Is Gender Affirmation Surgery Performed?

A person may have gender affirmation surgery for different reasons. They may choose to have the surgery so their physical features and functional ability align more closely with their gender identity.

For example, one study found that 48,019 people underwent gender affirmation surgeries between 2016 and 2020. Most procedures were breast- and chest-related, while the remaining procedures concerned genital reconstruction or facial and cosmetic procedures.

In some cases, surgery may be medically necessary to treat dysphoria. Dysphoria refers to the distress that transgender people may experience when their gender identity doesn't match their sex assigned at birth. One study found that people with gender dysphoria who had gender affirmation surgeries experienced:

- Decreased antidepressant use

- Decreased anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation

- Decreased alcohol and drug abuse

However, these surgeries are only performed if appropriate for a person's case. The appropriateness comes about as a result of consultations with mental health professionals and healthcare providers.

Transgender vs Nonbinary

Transgender and nonbinary people can get gender affirmation surgeries. However, there are some key ways that these gender identities differ.

Transgender is a term that refers to people who have gender identities that aren't the same as their assigned sex at birth. Identifying as nonbinary means that a person doesn't identify only as a man or a woman. A nonbinary individual may consider themselves to be:

- Both a man and a woman

- Neither a man nor a woman

- An identity between or beyond a man or a woman

Hormone Therapy

Gender-affirming hormone therapy uses sex hormones and hormone blockers to help align the person's physical appearance with their gender identity. For example, some people may take masculinizing hormones.

"They start growing hair, their voice deepens, they get more muscle mass," Heidi Wittenberg, MD , medical director of the Gender Institute at Saint Francis Memorial Hospital in San Francisco and director of MoZaic Care Inc., which specializes in gender-related genital, urinary, and pelvic surgeries, told Health .

Types of hormone therapy include:

- Masculinizing hormone therapy uses testosterone. This helps to suppress the menstrual cycle, grow facial and body hair, increase muscle mass, and promote other male secondary sex characteristics.

- Feminizing hormone therapy includes estrogens and testosterone blockers. These medications promote breast growth, slow the growth of body and facial hair, increase body fat, shrink the testicles, and decrease erectile function.

- Non-binary hormone therapy is typically tailored to the individual and may include female or male sex hormones and/or hormone blockers.

It can include oral or topical medications, injections, a patch you wear on your skin, or a drug implant. The therapy is also typically recommended before gender affirmation surgery unless hormone therapy is medically contraindicated or not desired by the individual.

Masculinizing Surgeries

Masculinizing surgeries can include top surgery, bottom surgery, or both. Common trans male surgeries include:

- Chest masculinization (breast tissue removal and areola and nipple repositioning/reshaping)

- Hysterectomy (uterus removal)

- Metoidioplasty (lengthening the clitoris and possibly extending the urethra)

- Oophorectomy (ovary removal)

- Phalloplasty (surgery to create a penis)

- Scrotoplasty (surgery to create a scrotum)

Top Surgery

Chest masculinization surgery, or top surgery, often involves removing breast tissue and reshaping the areola and nipple. There are two main types of chest masculinization surgeries:

- Double-incision approach : Used to remove moderate to large amounts of breast tissue, this surgery involves two horizontal incisions below the breast to remove breast tissue and accentuate the contours of pectoral muscles. The nipples and areolas are removed and, in many cases, resized, reshaped, and replaced.

- Short scar top surgery : For people with smaller breasts and firm skin, the procedure involves a small incision along the lower half of the areola to remove breast tissue. The nipple and areola may be resized before closing the incision.

Metoidioplasty

Some trans men elect to do metoidioplasty, also called a meta, which involves lengthening the clitoris to create a small penis. Both a penis and a clitoris are made of the same type of tissue and experience similar sensations.

Before metoidioplasty, testosterone therapy may be used to enlarge the clitoris. The procedure can be completed in one surgery, which may also include:

- Constructing a glans (head) to look more like a penis

- Extending the urethra (the tube urine passes through), which allows the person to urinate while standing

- Creating a scrotum (scrotoplasty) from labia majora tissue

Phalloplasty

Other trans men opt for phalloplasty to give them a phallic structure (penis) with sensation. Phalloplasty typically requires several procedures but results in a larger penis than metoidioplasty.

The first and most challenging step is to harvest tissue from another part of the body, often the forearm or back, along with an artery and vein or two, to create the phallus, Nicholas Kim, MD, assistant professor in the division of plastic and reconstructive surgery in the department of surgery at the University of Minnesota Medical School in Minneapolis, told Health .

Those structures are reconnected under an operative microscope using very fine sutures—"thinner than our hair," said Dr. Kim. That surgery alone can take six to eight hours, he added.

In a separate operation, called urethral reconstruction, the surgeons connect the urinary system to the new structure so that urine can pass through it, said Dr. Kim. Urethral reconstruction, however, has a high rate of complications, which include fistulas or strictures.

According to Dr. Kim, some trans men prefer to skip that step, especially if standing to urinate is not a priority. People who want to have penetrative sex will also need prosthesis implant surgery.

Hysterectomy and Oophorectomy

Masculinizing surgery often includes the removal of the uterus (hysterectomy) and ovaries (oophorectomy). People may want a hysterectomy to address their dysphoria, said Dr. Wittenberg, and it may be necessary if their gender-affirming surgery involves removing the vagina.

Many also opt for an oophorectomy to remove the ovaries, almond-shaped organs on either side of the uterus that contain eggs and produce female sex hormones. In this case, oocytes (eggs) can be extracted and stored for a future surrogate pregnancy, if desired. However, this is a highly personal decision, and some trans men choose to keep their uterus to preserve fertility.

Feminizing Surgeries

Surgeries are often used to feminize facial features, enhance breast size and shape, reduce the size of an Adam’s apple , and reconstruct genitals. Feminizing surgeries can include:

- Breast augmentation

- Facial feminization surgery

- Penis removal (penectomy)

- Scrotum removal (scrotectomy)

- Testicle removal (orchiectomy)

- Tracheal shave (chondrolaryngoplasty) to reduce an Adam's apple

- Vaginoplasty

- Voice feminization

Breast Augmentation

Top surgery, also known as breast augmentation or breast mammoplasty, is often used to increase breast size for a more feminine appearance. The procedure can involve placing breast implants, tissue expanders, or fat from other parts of the body under the chest tissue.

Breast augmentation can significantly improve gender dysphoria. Studies show most people who undergo top surgery are happier, more satisfied with their chest, and would undergo the surgery again.

Most surgeons recommend 12 months of feminizing hormone therapy before breast augmentation. Since hormone therapy itself can lead to breast tissue development, transgender women may or may not decide to have surgical breast augmentation.

Facial Feminization and Adam's Apple Removal

Facial feminization surgery (FFS) is a series of plastic surgery procedures that reshape the forehead, hairline, eyebrows, nose, cheeks, and jawline. Nonsurgical treatments like cosmetic fillers, botox, fat grafting, and liposuction may also be used to create a more feminine appearance.

Some trans women opt for chondrolaryngoplasty, also known as a tracheal shave. The procedure reduces the size of the Adam's apple, an area of cartilage around the larynx (voice box) that tends to be larger in people assigned male at birth.

Vulvoplasty and Vaginoplasty

As for bottom surgery, there are various feminizing procedures from which to choose. Vulvoplasty (to create external genitalia without a vagina) or vaginoplasty (to create a vulva and vaginal canal) are two of the most common procedures.

Dr. Wittenberg noted that people might undergo six to 12 months of electrolysis or laser hair removal before surgery to remove pubic hair from the skin that will be used for the vaginal lining.

Surgeons have different techniques for creating a vaginal canal. A common one is a penile inversion, where the masculine structures are emptied and inverted into a created cavity, explained Dr. Kim. Vaginoplasty may be done in one or two stages, said Dr. Wittenberg, and the initial recovery is three months—but it will be a full year until people see results.

Surgical removal of the penis or penectomy is sometimes used in feminization treatment. This can be performed along with an orchiectomy and scrotectomy.

However, a total penectomy is not commonly used in feminizing surgeries . Instead, many people opt for penile-inversion surgery, a technique that hollows out the penis and repurposes the tissue to create a vagina during vaginoplasty.

Orchiectomy and Scrotectomy

An orchiectomy is a surgery to remove the testicles —male reproductive organs that produce sperm. Scrotectomy is surgery to remove the scrotum, that sac just below the penis that holds the testicles.

However, some people opt to retain the scrotum. Scrotum skin can be used in vulvoplasty or vaginoplasty, surgeries to construct a vulva or vagina.

Other Surgical Options

Some gender non-conforming people opt for other types of surgeries. This can include:

- Gender nullification procedures

- Penile preservation vaginoplasty

- Vaginal preservation phalloplasty

Gender Nullification

People who are agender or asexual may opt for gender nullification, sometimes called nullo. This involves the removal of all sex organs. The external genitalia is removed, leaving an opening for urine to pass and creating a smooth transition from the abdomen to the groin.

Depending on the person's sex assigned at birth, nullification surgeries can include:

- Breast tissue removal

- Nipple and areola augmentation or removal

Penile Preservation Vaginoplasty

Some gender non-conforming people assigned male at birth want a vagina but also want to preserve their penis, said Dr. Wittenberg. Often, that involves taking skin from the lining of the abdomen to create a vagina with full depth.

Vaginal Preservation Phalloplasty

Alternatively, a patient assigned female at birth can undergo phalloplasty (surgery to create a penis) and retain the vaginal opening. Known as vaginal preservation phalloplasty, it is often used as a way to resolve gender dysphoria while retaining fertility.

The recovery time for a gender affirmation surgery will depend on the type of surgery performed. For example, healing for facial surgeries may last for weeks, while transmasculine bottom surgery healing may take months.

Your recovery process may also include additional treatments or therapies. Mental health support and pelvic floor physiotherapy are a few options that may be needed or desired during recovery.

Risks and Complications

The risk and complications of gender affirmation surgeries will vary depending on which surgeries you have. Common risks across procedures could include:

- Anesthesia risks

- Hematoma, which is bad bruising

- Poor incision healing

Complications from these procedures may be:

- Acute kidney injury

- Blood transfusion

- Deep vein thrombosis, which is blood clot formation

- Pulmonary embolism, blood vessel blockage for vessels going to the lung

- Rectovaginal fistula, which is a connection between two body parts—in this case, the rectum and vagina

- Surgical site infection

- Urethral stricture or stenosis, which is when the urethra narrows

- Urinary tract infection (UTI)

- Wound disruption

What To Consider

It's important to note that an individual does not need surgery to transition. If the person has surgery, it is usually only one part of the transition process.

There's also psychotherapy . People may find it helpful to work through the negative mental health effects of dysphoria. Typically, people seeking gender affirmation surgery must be evaluated by a qualified mental health professional to obtain a referral.

Some people may find that living in their preferred gender is all that's needed to ease their dysphoria. Doing so for one full year prior is a prerequisite for many surgeries.

All in all, the entire transition process—living as your identified gender, obtaining mental health referrals, getting insurance approvals, taking hormones, going through hair removal, and having various surgeries—can take years, healthcare providers explained.

A Quick Review

Whether you're in the process of transitioning or supporting someone who is, it's important to be informed about gender affirmation surgeries. Gender affirmation procedures often involve multiple surgeries, which can be masculinizing, feminizing, or gender-nullifying in nature.

It is a highly personalized process that looks different for each person and can often take several months or years. The procedures also vary regarding risks and complications, so consultations with healthcare providers and mental health professionals are essential before having these procedures.

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Gender affirmation surgeries .

Wright JD, Chen L, Suzuki Y, Matsuo K, Hershman DL. National estimates of gender-affirming surgery in the US . JAMA Netw Open . 2023;6(8):e2330348-e2330348. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.30348

Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8 . Int J Transgend Health . 2022;23(S1):S1-S260. doi:10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

Chou J, Kilmer LH, Campbell CA, DeGeorge BR, Stranix JY. Gender-affirming surgery improves mental health outcomes and decreases anti-depressant use in patients with gender dysphoria . Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open . 2023;11(6 Suppl):1. doi:10.1097/01.GOX.0000944280.62632.8c

Human Rights Campaign. Get the facts on gender-affirming care .

Human Rights Campaign. Transgender and non-binary people FAQ .

Unger CA. Hormone therapy for transgender patients . Transl Androl Urol . 2016;5(6):877–84. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.09.04

Richards JE, Hawley RS. Chapter 8: Sex Determination: How Genes Determine a Developmental Choice . In: Richards JE, Hawley RS, eds. The Human Genome . 3rd ed. Academic Press; 2011: 273-298.

Randolph JF Jr. Gender-affirming hormone therapy for transgender females . Clin Obstet Gynecol . 2018;61(4):705-721. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000396

Cocchetti C, Ristori J, Romani A, Maggi M, Fisher AD. Hormonal treatment strategies tailored to non-binary transgender individuals . J Clin Med . 2020;9(6):1609. doi:10.3390/jcm9061609

Van Boerum MS, Salibian AA, Bluebond-Langner R, Agarwal C. Chest and facial surgery for the transgender patient . Transl Androl Urol . 2019;8(3):219-227. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.06.18

Djordjevic ML, Stojanovic B, Bizic M. Metoidioplasty: techniques and outcomes . Transl Androl Urol . 2019;8(3):248–53. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.06.12

Bordas N, Stojanovic B, Bizic M, Szanto A, Djordjevic ML. Metoidioplasty: surgical options and outcomes in 813 cases . Front Endocrinol . 2021;12:760284. doi:10.3389/fendo.2021.760284

Al-Tamimi M, Pigot GL, van der Sluis WB, et al. The surgical techniques and outcomes of secondary phalloplasty after metoidioplasty in transgender men: an international, multi-center case series . The Journal of Sexual Medicine . 2019;16(11):1849-1859. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.07.027

Waterschoot M, Hoebeke P, Verla W, et al. Urethral complications after metoidioplasty for genital gender affirming surgery . J Sex Med . 2021;18(7):1271–9. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.06.023

Nikolavsky D, Hughes M, Zhao LC. Urologic complications after phalloplasty or metoidioplasty . Clin Plast Surg . 2018;45(3):425–35. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2018.03.013

Nota NM, den Heijer M, Gooren LJ. Evaluation and treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender incongruent adults . In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., eds. Endotext . MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

Carbonnel M, Karpel L, Cordier B, Pirtea P, Ayoubi JM. The uterus in transgender men . Fertil Steril . 2021;116(4):931–5. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.07.005

Miller TJ, Wilson SC, Massie JP, Morrison SD, Satterwhite T. Breast augmentation in male-to-female transgender patients: Technical considerations and outcomes . JPRAS Open . 2019;21:63-74. doi:10.1016/j.jpra.2019.03.003

Claes KEY, D'Arpa S, Monstrey SJ. Chest surgery for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals . Clin Plast Surg . 2018;45(3):369–80. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2018.03.010

De Boulle K, Furuyama N, Heydenrych I, et al. Considerations for the use of minimally invasive aesthetic procedures for facial remodeling in transgender individuals . Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol . 2021;14:513-525. doi:10.2147/CCID.S304032

Asokan A, Sudheendran MK. Gender affirming body contouring and physical transformation in transgender individuals . Indian J Plast Surg . 2022;55(2):179-187. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1749099

Sturm A, Chaiet SR. Chondrolaryngoplasty-thyroid cartilage reduction . Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am . 2019;27(2):267–72. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2019.01.005

Chen ML, Reyblat P, Poh MM, Chi AC. Overview of surgical techniques in gender-affirming genital surgery . Transl Androl Urol . 2019;8(3):191-208. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.06.19

Wangjiraniran B, Selvaggi G, Chokrungvaranont P, Jindarak S, Khobunsongserm S, Tiewtranon P. Male-to-female vaginoplasty: Preecha's surgical technique . J Plast Surg Hand Surg . 2015;49(3):153-9. doi:10.3109/2000656X.2014.967253

Okoye E, Saikali SW. Orchiectomy . In: StatPearls [Internet] . Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

Salgado CJ, Yu K, Lalama MJ. Vaginal and reproductive organ preservation in trans men undergoing gender-affirming phalloplasty: technical considerations . J Surg Case Rep . 2021;2021(12):rjab553. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjab553

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What should I expect during my recovery after facial feminization surgery?

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What should I expect during my recovery after transmasculine bottom surgery?

de Brouwer IJ, Elaut E, Becker-Hebly I, et al. Aftercare needs following gender-affirming surgeries: findings from the ENIGI multicenter European follow-up study . The Journal of Sexual Medicine . 2021;18(11):1921-1932. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.08.005

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What are the risks of transfeminine bottom surgery?

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What are the risks of transmasculine top surgery?

Khusid E, Sturgis MR, Dorafshar AH, et al. Association between mental health conditions and postoperative complications after gender-affirming surgery . JAMA Surg . 2022;157(12):1159-1162. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2022.3917

Related Articles

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/72848552/shutterstock_304415033.0.0.0.0.jpg)

What I wish I’d known before I had gender-affirming surgery

The media makes out procedures like the one I had to be cure-alls. They're not.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: What I wish I’d known before I had gender-affirming surgery

I have nightmares about growing a beard and having a penis. They've occurred more and more frequently the further I've progressed into my transition from male to female.

Last July, New York magazine published a video explaining what nightmares are : our brains' way of taking whatever is bothering or frightening us in life and morphing it into tales that we can process as memories. Thanks to hormone therapy, laser treatments, and vaginoplasty surgery, I no longer grow facial hair or have a penis, but the thought of being a boy still terrifies me and always will. These nightmares are my brain's way of helping me distance myself from that fear.

Much of what you can find about gender-affirming surgeries like vaginoplasty makes you think that after you've had one, all your problems fade away and your life becomes instantaneously better. Take a look at these recent videos by the New York Times and NPR , and this article by NBC : All three leave you with the impression that the surgery is a type of transition denouement. In the video by the Times, for example, Katherine, supported by pleasant and hopeful music, says this about her surgery: "It's, like, the new me. I finally feel like myself, so it kind of, in a sense, is a rebirth day … a renaissance."

NPR similarly ends its video with Jetta'Mae Carlisle, who, having undergone the surgery, says, "I have that white picket fence dream, and that's where my future is." The NBC article quotes Denee Mallon saying, "I feel complete."

These reports obscure the truth: While gender-affirming surgeries can make people more comfortable in their bodies, they're not a fix-it for everything wrong in your life. I know this from my own experience with surgery, and from studying the research on it.

I wish I had better resources to help prepare me for my surgery

People who want to have a vaginoplasty must get referrals from two different therapists. Dr. Molly Parks, a gender therapist in Durham, North Carolina, told me the goal of preoperative therapy is to make sure patients have really thought through their decision, and to determine whether they have any mental health issues that could hamper their decision-making.

"I ultimately think that the client is the only one who can determine whether a procedure is the right decision for them," said Parks.

My pre-op therapy largely went the way Parks described. With my first therapist, I explored how long I'd had gender dysphoria, a medical condition characterized by an extreme discomfort with the primary and secondary sex characteristics of one's body. We talked about how I thought of myself as a girl, therapy history, my relationships with friends and family, what support structures I had in place, and what goals I was pursuing in life. My second therapist and I made sure I was mentally capable of grasping the decision I was making.

Thinking back, though, my pre-op therapy didn't help me realize how extraordinarily hard it would be to recover from the surgery I had: the stress from being unable to eat solid food for a week and a half, and the feeling of helplessness from being so bedridden and unable to walk normally for weeks, to name only two difficulties. I'm also, apparently, not the only one who's had this gap in his or her therapy experience.

"I would think, and hope, that most gender therapists … would talk through the potential difficult side effects of surgery," said Parks. "The therapists I work with do tend to do this, although I have had clients who have come to me from therapists where this was not the case."

Parks said that currently there are "no specific guidelines in place as to what therapy has to look like presurgery." That could change, though — she is a member of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, and she said she thinks the organization should adopt guidelines for preoperative therapy.

Researching on your own the gender-affirming surgery you need, especially one so enigmatic as vaginoplasty, and without guidance from an informed therapist on the subject, can be excruciating. There was no formal education I could find about vaginoplasty. Even with information provided by my surgeon, I still found myself reading online Q&As, visiting forums, and reading news articles. Trying to form a clear picture of the surgical experience seems impossible when the information you find is so disjointed and often so hateful and frightening.

I've seen several horrible euphemisms used to describe a postoperative vagina: "frankenpussy," "mutilated dickhole," "an open wound," "penis bits." Sometimes the sentiment behind these phrases manifests in very violent ways: Vice published a moving article last year about the 23 trans women killed in 2015.

It's also really easy to come across articles that describe the surgery as mutilation . In her article for Public Discourse , Margaret A. Hagen, a professor at Boston University, described a woman like me as a "mutilated male pumped full of estrogen."

One of the most tiring factors of transitioning is having to be on constant emotional guard everywhere you go. Despite your best efforts, though, you have to wonder how much negativity has been internalized. My vagina is not a mutilation, but I must admit I might not like it as much as I should after reading so much horrible language directed toward it.

What happens when expectations meet reality

Being inadequately prepared for surgery has real consequences.

In an essay published last summer, Don Terry explored the horrible struggles black trans women face. One woman told Terry she knew several people who'd killed themselves after having surgery. "They really thought life was going to be completely different," she said. "Nothing changed. That's a whole lot of money to invest to still have the same life."

If you're in a shit situation before surgery, you'll be in a shit situation after. If your co-workers aren't supportive of your transition, they're not going to change their minds once you have a vagina. The friends you've lost aren't going to come back now that you have female genitalia. If you've made it far enough to get surgery without support from your family, they won't come around in the aftermath of the operation; what they say to you might change, but their true feelings certainly won't.

And you'll still come across news articles that say your vagina is mutilation. You're still going to have people calling you a man. You're still going to see people freak out about you using a certain bathroom. Surgery will not change any of this.

And indeed, people who have gender-affirming surgeries still experience higher suicide and attempted suicide rates than the rest of the population, according to a 2011 study from Sweden. Some cite this research in the hopes of convincing others that the surgeries are ineffective and ultimately harmful , but they do so in error. The researchers go out of their way to explain that the surgeries are not the cause of the high suicide rates: "The results should not be interpreted such as [the surgery] per se increases morbidity and mortality." They say "things might have been even worse" without the surgery.

The latest research shows that it's discrimination and stigma, not surgery itself, that causes the high suicide and attempted suicide rates. A study published in Ontario in 2015 revealed that those who have a supportive social environment (the most important social support being parents) were far less likely to seriously consider suicide. Other factors, like having one official document properly identifying your sex, also correlated with lower suicide attempts and rates.

My major problem, like many others, is employment. According to the National Center for Transgender Equality's 2011 survey , 44 percent of the respondents were experiencing underemployment, the unemployment rate was twice that of the national average, and 90 percent said they had experienced workplace harassment or had to hide who they are to avoid such harassment.

It's been almost two years since I graduated, and I still don't have a full-time job. Though I've been recently accepted to graduate school — a very encouraging development! — I need to find a part-time job soon, because my mom isn't doing so well financially at the moment. I'm terrified, however, of encountering harassment on the job, so I'm forced to be very selective in my search.

Transitioning is a long, challenging road

Transitioning is one of the hardest, most overwhelming experiences someone can go through. It's the kind of gamble you make when your back is against the wall and everything seems at stake. Some people take years to finish if they're lucky enough to finish or start at all; others think they never finish simply because learning what a woman or man is takes a lifetime.

Transitioning is also not a cure. I needed gender-affirming surgery to alleviate gender dysphoria and feel as comfortable in my body as possible, but there is no cure for gender dysphoria — you can only treat the symptoms, and our ability to treat the symptoms is limited. I still experience dysphoria even though my physical results have turned out well. When I'm stressed out, my dysphoria worsens, making it harder to deal with whatever was stressing me out in the first place.

In February 2013, a month into my transition, I admitted myself to a psychiatric ward because I was afraid I was going to hurt myself. Though I've thankfully never had so serious a situation since then, I've had suicidal thoughts every year since I started transitioning. Maybe, hopefully, finally 2016 will be the first where I don't have any at all.

The morning of my surgery, the day of my last big step, I realized that right now in our society, transitioning isn't just some process you go through; it's also something you survive.

I've had vaginoplasty. I've finished transitioning. But I've yet to survive it.

J.L. is a freelance writer.

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Tucker Carlson went after Israel — and his fellow conservatives are furious

Why the case at the center of netflix’s what jennifer did isn’t over yet, alec baldwin’s rust, the on-set shooting, and the ongoing legal cases, explained, sign up for the newsletter today, explained, thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Tests & Procedures

- Feminizing hormone therapy

Feminizing hormone therapy typically is used by transgender women and nonbinary people to produce physical changes in the body that are caused by female hormones during puberty. Those changes are called secondary sex characteristics. This hormone therapy helps better align the body with a person's gender identity. Feminizing hormone therapy also is called gender-affirming hormone therapy.

Feminizing hormone therapy involves taking medicine to block the action of the hormone testosterone. It also includes taking the hormone estrogen. Estrogen lowers the amount of testosterone the body makes. It also triggers the development of feminine secondary sex characteristics. Feminizing hormone therapy can be done alone or along with feminizing surgery.

Not everybody chooses to have feminizing hormone therapy. It can affect fertility and sexual function, and it might lead to health problems. Talk with your health care provider about the risks and benefits for you.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Available Sexual Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Why it's done

Feminizing hormone therapy is used to change the body's hormone levels. Those hormone changes trigger physical changes that help better align the body with a person's gender identity.

In some cases, people seeking feminizing hormone therapy experience discomfort or distress because their gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth or from their sex-related physical characteristics. This condition is called gender dysphoria.

Feminizing hormone therapy can:

- Improve psychological and social well-being.

- Ease psychological and emotional distress related to gender.

- Improve satisfaction with sex.

- Improve quality of life.

Your health care provider might advise against feminizing hormone therapy if you:

- Have a hormone-sensitive cancer, such as prostate cancer.

- Have problems with blood clots, such as when a blood clot forms in a deep vein, a condition called deep vein thrombosis, or a there's a blockage in one of the pulmonary arteries of the lungs, called a pulmonary embolism.

- Have significant medical conditions that haven't been addressed.

- Have behavioral health conditions that haven't been addressed.

- Have a condition that limits your ability to give your informed consent.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

Stay Informed with LGBTQ+ health content.

Receive trusted health information and answers to your questions about sexual orientation, gender identity, transition, self-expression, and LGBTQ+ health topics. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing to our LGBTQ+ newsletter.

You will receive the first newsletter in your inbox shortly. This will include exclusive health content about the LGBTQ+ community from Mayo Clinic.

If you don't receive our email within 5 minutes, check your SPAM folder, then contact us at [email protected] .

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Research has found that feminizing hormone therapy can be safe and effective when delivered by a health care provider with expertise in transgender care. Talk to your health care provider about questions or concerns you have regarding the changes that will happen in your body as a result of feminizing hormone therapy.

Complications can include:

- Blood clots in a deep vein or in the lungs

- Heart problems

- High levels of triglycerides, a type of fat, in the blood

- High levels of potassium in the blood

- High levels of the hormone prolactin in the blood

- Nipple discharge

- Weight gain

- Infertility

- High blood pressure

- Type 2 diabetes

Evidence suggests that people who take feminizing hormone therapy may have an increased risk of breast cancer when compared to cisgender men — men whose gender identity aligns with societal norms related to their sex assigned at birth. But the risk is not greater than that of cisgender women.

To minimize risk, the goal for people taking feminizing hormone therapy is to keep hormone levels in the range that's typical for cisgender women.

Feminizing hormone therapy might limit your fertility. If possible, it's best to make decisions about fertility before starting treatment. The risk of permanent infertility increases with long-term use of hormones. That is particularly true for those who start hormone therapy before puberty begins. Even after stopping hormone therapy, your testicles might not recover enough to ensure conception without infertility treatment.

If you want to have biological children, talk to your health care provider about freezing your sperm before you start feminizing hormone therapy. That procedure is called sperm cryopreservation.

How you prepare

Before you start feminizing hormone therapy, your health care provider assesses your health. This helps address any medical conditions that might affect your treatment. The evaluation may include:

- A review of your personal and family medical history.

- A physical exam.

- A review of your vaccinations.

- Screening tests for some conditions and diseases.

- Identification and management, if needed, of tobacco use, drug use, alcohol use disorder, HIV or other sexually transmitted infections.

- Discussion about sperm freezing and fertility.

You also might have a behavioral health evaluation by a provider with expertise in transgender health. The evaluation may assess:

- Gender identity.

- Gender dysphoria.

- Mental health concerns.

- Sexual health concerns.

- The impact of gender identity at work, at school, at home and in social settings.

- Risky behaviors, such as substance use or use of unapproved silicone injections, hormone therapy or supplements.

- Support from family, friends and caregivers.

- Your goals and expectations of treatment.

- Care planning and follow-up care.

People younger than age 18, along with a parent or guardian, should see a medical care provider and a behavioral health provider with expertise in pediatric transgender health to discuss the risks and benefits of hormone therapy and gender transitioning in that age group.

What you can expect

You should start feminizing hormone therapy only after you've had a discussion of the risks and benefits as well as treatment alternatives with a health care provider who has expertise in transgender care. Make sure you understand what will happen and get answers to any questions you may have before you begin hormone therapy.

Feminizing hormone therapy typically begins by taking the medicine spironolactone (Aldactone). It blocks male sex hormone receptors — also called androgen receptors. This lowers the amount of testosterone the body makes.

About 4 to 8 weeks after you start taking spironolactone, you begin taking estrogen. This also lowers the amount of testosterone the body makes. And it triggers physical changes in the body that are caused by female hormones during puberty.

Estrogen can be taken several ways. They include a pill and a shot. There also are several forms of estrogen that are applied to the skin, including a cream, gel, spray and patch.

It is best not to take estrogen as a pill if you have a personal or family history of blood clots in a deep vein or in the lungs, a condition called venous thrombosis.

Another choice for feminizing hormone therapy is to take gonadotropin-releasing hormone (Gn-RH) analogs. They lower the amount of testosterone your body makes and might allow you to take lower doses of estrogen without the use of spironolactone. The disadvantage is that Gn-RH analogs usually are more expensive.

After you begin feminizing hormone therapy, you'll notice the following changes in your body over time:

- Fewer erections and a decrease in ejaculation. This will begin 1 to 3 months after treatment starts. The full effect will happen within 3 to 6 months.

- Less interest in sex. This also is called decreased libido. It will begin 1 to 3 months after you start treatment. You'll see the full effect within 1 to 2 years.

- Slower scalp hair loss. This will begin 1 to 3 months after treatment begins. The full effect will happen within 1 to 2 years.

- Breast development. This begins 3 to 6 months after treatment starts. The full effect happens within 2 to 3 years.

- Softer, less oily skin. This will begin 3 to 6 months after treatment starts. That's also when the full effect will happen.

- Smaller testicles. This also is called testicular atrophy. It begins 3 to 6 months after the start of treatment. You'll see the full effect within 2 to 3 years.

- Less muscle mass. This will begin 3 to 6 months after treatment starts. You'll see the full effect within 1 to 2 years.

- More body fat. This will begin 3 to 6 months after treatment starts. The full effect will happen within 2 to 5 years.

- Less facial and body hair growth. This will begin 6 to 12 months after treatment starts. The full effect happens within three years.

Some of the physical changes caused by feminizing hormone therapy can be reversed if you stop taking it. Others, such as breast development, cannot be reversed.

While on feminizing hormone therapy, you meet regularly with your health care provider to:

- Keep track of your physical changes.

- Monitor your hormone levels. Over time, your hormone dose may need to change to ensure you are taking the lowest dose necessary to get the physical effects that you want.

- Have blood tests to check for changes in your cholesterol, blood sugar, blood count, liver enzymes and electrolytes that could be caused by hormone therapy.

- Monitor your behavioral health.

You also need routine preventive care. Depending on your situation, this may include:

- Breast cancer screening. This should be done according to breast cancer screening recommendations for cisgender women your age.

- Prostate cancer screening. This should be done according to prostate cancer screening recommendations for cisgender men your age.

- Monitoring bone health. You should have bone density assessment according to the recommendations for cisgender women your age. You may need to take calcium and vitamin D supplements for bone health.

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies of tests and procedures to help prevent, detect, treat or manage conditions.

Feminizing hormone therapy care at Mayo Clinic

- Tangpricha V, et al. Transgender women: Evaluation and management. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Oct. 10, 2022.

- Erickson-Schroth L, ed. Medical transition. In: Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource by and for Transgender Communities. 2nd ed. Kindle edition. Oxford University Press; 2022. Accessed Oct. 10, 2022.

- Coleman E, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health. 2022; doi:10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644.

- AskMayoExpert. Gender-affirming hormone therapy (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2022.

- Nippoldt TB (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. Sept. 29, 2022.

- Gender dysphoria

- Doctors & Departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, male-to-female gender-affirming surgery: 20-year review of technique and surgical results.

- 1 Serviço de Urologia, Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, Brazil

- 2 Serviço de Psiquiatria, Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, Brazil

- 3 Serviço de Psiquiatria, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil

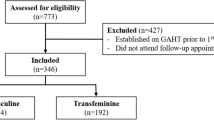

Purpose: Gender dysphoria (GD) is an incompatibility between biological sex and personal gender identity; individuals harbor an unalterable conviction that they were born in the wrong body, which causes personal suffering. In this context, surgery is imperative to achieve a successful gender transition and plays a key role in alleviating the associated psychological discomfort. In the current study, a retrospective cohort, we report the 20-years outcomes of the gender-affirming surgery performed at a single Brazilian university center, examining demographic data, intra and postoperative complications. During this period, 214 patients underwent penile inversion vaginoplasty.

Results: Results demonstrate that the average age at the time of surgery was 32.2 years (range, 18–61 years); the average of operative time was 3.3 h (range 2–5 h); the average duration of hormone therapy before surgery was 12 years (range 1–39). The most commons minor postoperative complications were granulation tissue (20.5 percent) and introital stricture of the neovagina (15.4 percent) and the major complications included urethral meatus stenosis (20.5 percent) and hematoma/excessive bleeding (8.9 percent). A total of 36 patients (16.8 percent) underwent some form of reoperation. One hundred eighty-one (85 percent) patients in our series were able to have regular sexual intercourse, and no individual regretted having undergone GAS.

Conclusions: Findings confirm that it is a safety procedure, with a low incidence of serious complications. Otherwise, in our series, there were a high level of functionality of the neovagina, as well as subjective personal satisfaction.

Introduction

Transsexualism (ICD-10) or Gender Dysphoria (GD) (DSM-5) is characterized by intense and persistent cross-gender identification which influences several aspects of behavior ( 1 ). The terms describe a situation where an individual's gender identity differs from external sexual anatomy at birth ( 1 ). Gender identity-affirming care, for those who desire, can include hormone therapy and affirming surgeries, as well as other procedures such as hair removal or speech therapy ( 1 ).

Since 1998, the Gender Identity Program (PROTIG) of the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA), Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil has provided public assistance to transsexual people, is the first one in Brazil and one of the pioneers in South America. Our program offers psychosocial support, health care, and guidance to families, and refers individuals for gender-affirming surgery (GAS) when indicated. To be eligible for this surgery, transsexual individuals must have been adherent to multidisciplinary follow-up for at least 2 years, have a minimum age of 21 years (required for surgical procedures of this nature), have a positive psychiatric or psychological report, and have a diagnosis of GD.

Gender-affirming surgery (GAS) is increasingly recognized as a therapeutic intervention and a medical necessity, with growing societal acceptance ( 2 ). At our institution, we perform the classic penile inversion vaginoplasty (PIV), with an inverted penis skin flap used as the lining for the neovagina. Studies have demonstrated that GAS for the management of GD can promote improvements in mental health and social relationships for these patients ( 2 – 5 ). It is therefore imperative to understand and establish best practice techniques for this patient population ( 2 ). Although there are several studies reporting the safety and efficacy of gender-affirming surgery by penile inversion vaginoplasty, we present the largest South-American cohort to date, examining demographic data, intra and postoperative complications.

Patients and Methods

Subjects and study setup.

This is a retrospective cohort study of Brazilian transgender women who underwent penile inversion vaginoplasty between January of 2000 and March of 2020 at the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, Brazil. The study was approved by our institutional medical and research ethics committee.

At our institution, gender-affirming surgery is indicated for transgender women who are under assistance by our program for transsexual individuals. All transsexual women included in this study had at least 2 years of experience as a woman and met WPATH standards for GAS ( 1 ). Patients were submitted to biweekly group meetings and monthly individual therapy.

Between January of 2000 and March of 2020, a total of 214 patients underwent penile inversion vaginoplasty. The surgical procedures were performed by two separate staff members, mostly assisted by residents. A retrospective chart review was conducted recording patient demographics, intraoperative and postoperative complications, reoperations, and secondary surgical procedures. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Hormonal Therapy

The goal of feminizing hormone therapy is the development of female secondary sex characteristics, and suppression/minimization of male secondary sex characteristics.

Our general therapy approach is to combine an estrogen with an androgen blocker. The usual estrogen is the oral preparation of estradiol (17-beta estradiol), starting at a dose of 2 mg/day until the maximum dosage of 8 mg/day. The preferred androgen blocker is spironolactone at a dose of 200 mg twice a day.

Operative Technique

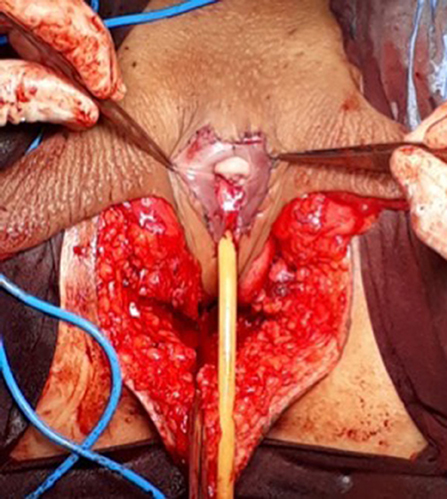

At our institution, we perform the classic penile inversion vaginoplasty, with an inverted penis skin flap used as the lining for the neovagina. For more details, we have previously published our technique with a step-by-step procedure video ( 6 ). All individuals underwent intestinal cleansing the evening before the surgery. A first-generation cephalosporin was used as preoperative prophylaxis. The procedure was performed with the patient in a dorsal lithotomy position. A Foley catheter was placed for bladder catheterization. A inverted-V incision was made 4 cm above the anus and a flap was created. A neovaginal cavity was created between the prostate and the rectum with blunt dissection, in the Denonvilliers space, until the peritoneal fold, usually measuring 12 cm in extension and 6 cm in width. The incision was then extended vertically to expose the testicles and the spermatic cords, which were removed at the level of the external inguinal rings. A circumferential subcoronal incision was made ( Figure 1 ), the penis was de-gloved and a skin flap was created, with the de-gloved penis being passed through the scrotal opening ( Figure 2 ). The dorsal part of the glans and its neurovascular bundle were bluntly dissected away from the penile shaft ( Figure 3 ) as well as the urethra, which included a portion of the bulbospongious muscle ( Figure 4 ). The corpora cavernosa was excised up to their attachments at the symphysis pubis and ligated. The neoclitoris was shaped and positioned in the midline at the level of the symphysis pubis and sutured using interrupted 5-0 absorbable suture. The corpus spongiosum was reduced and the urethra was shortened, spatulated, and placed 1 cm below the neoclitoris in the midline and sutured using interrupted 4-0 absorbable suture. The penile skin flap was inverted and pulled into the neovaginal cavity to become its walls ( Figure 5 ). The excess of skin was then removed, and the subcutaneous tissue and the skin were closed using continuous 3-0 non-absorbable suture ( Figure 6 ). A neo mons pubis was created using a 0 absorbable suture between the skin and the pubic bone. The skin flap was fixed to the pubic bone using a 0 absorbable suture. A gauze impregnated with Vaseline and antibiotic ointment was left inside the neovagina, and a customized compressive bandage was applied ( Figure 7 —shows the final appearance after the completion of the procedures).

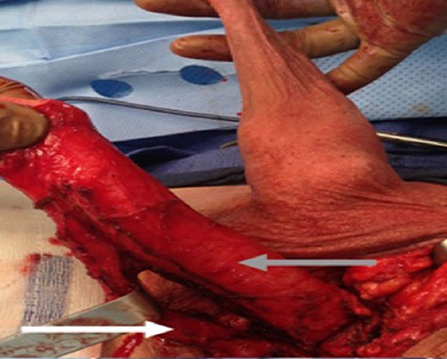

Figure 1 . The initial circumferential subcoronal incision.

Figure 2 . The de-gloved penis being passed through the scrotal opening.

Figure 3 . The dorsal part of the glans and its neurovascular bundle dissected away from the penile shaft.

Figure 4 . The urethra dissected including a portion of the bulbospongious muscle. The grey arrow shows the penile shaft and the white arrow shows the dissected urethra.

Figure 5 . The inverted penile skin flap.

Figure 6 . The neoclitoris and the urethra sutured in the midline and the neovaginal cavity.

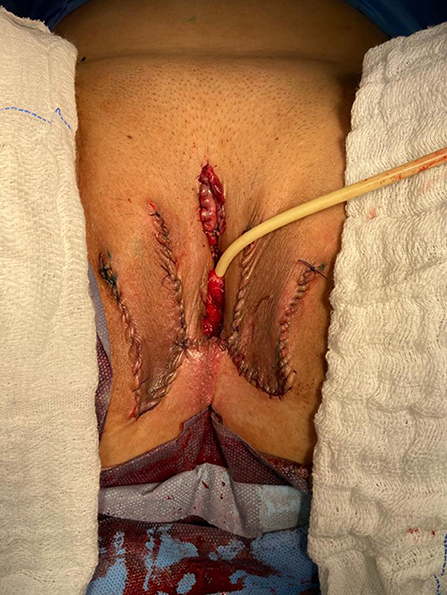

Figure 7 . The final appearance after the completion of the procedures.

Postoperative Care and Follow-Up

The patients were usually discharged within 2 days after surgery with the Foley catheter and vaginal gauze packing in place, which were removed after 7 days in an ambulatorial attendance.

Our vaginal dilation protocol starts seven days after surgery: a kit of 6 silicone dilators with progressive diameter (1.1–4 cm) and length (6.5–14.5 cm) is used; dilation is done progressively from the smallest dilator; each size should be kept in place for 5 min until the largest possible size, which is kept for 3 h during the day and during the night (sleep), if possible. The process is performed daily for the first 3 months and continued until the patient has regular sexual intercourse.

The follow-up visits were performed 7 days, 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery ( Figure 8 ), and included physical examination and a quality-of-life questionnaire.

Figure 8 . Appearance after 1 month of the procedure.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using Statistical Product and Service Solutions Version 18.0 (SPSS). Outcome measures were intra-operative and postoperative complications, re-operations. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the study outcomes. Mean values and standard deviations or median values and ranges are presented as continuous variables. Frequencies and percentages are reported for dichotomous and ordinal variables.

Patient Demographics

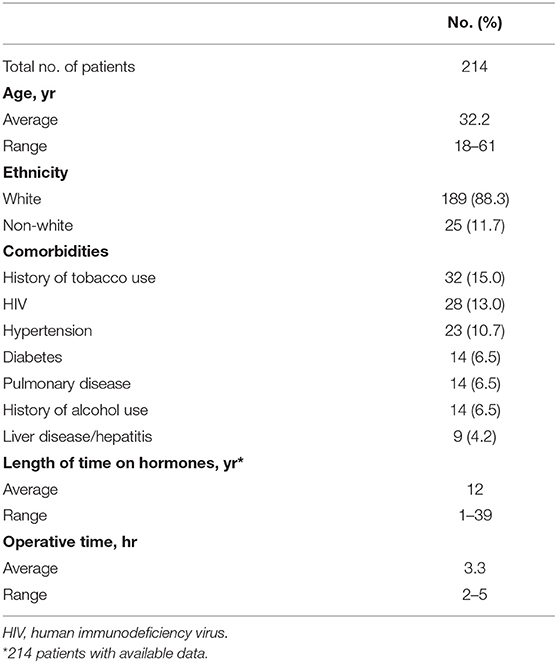

During the period of the study, 214 patients underwent penile inversion vaginoplasty, performed by two staff surgeons, mostly assisted by residents ( Table 1 ). The average age at the time of surgery was 32.2 years (range 18–61 years). There was no significant increase or decrease in the ages of patients who underwent SRS over the study period (Fisher's exact test: P = 0.065; chi-square test: X 2 = 5.15; GL = 6; P = 0.525). The average of operative time was 3.3 h (range 2–5 h). The average duration of hormone therapy before surgery was 12 years (range 1–39). The majority of patients were white (88.3 percent). The most prevalent patient comorbidities were history of tobacco use (15 percent), human immunodeficiency virus infection (13 percent) and hypertension (10.7 percent). Other comorbidities are listed in Table 1 .

Table 1 . Patient demographics.

Multidisciplinary follow-up was comprised of 93.45% of patients following up with a urologist and 59.06% of patients continuing psychiatric follow-up, median follow-up time of 16 and 9.3 months after surgery, respectively.

Postoperative Results

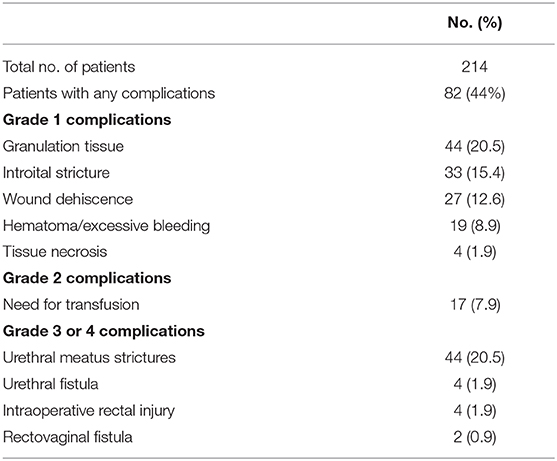

The complications were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo score ( Table 2 ). The most common minor postoperative complications (Grade I) were granulation tissue (20.5 percent), introital stricture of the neovagina (15.4 percent) and wound dehiscence (12.6 percent). The major complications (Grade III-IV) included urethral stenosis (20.5 percent), urethral fistula (1.9 percent), intraoperative rectal injury (1.9 percent), necrosis (primarily along the wound edges) (1.4 percent), and rectovaginal fistula (0.9 percent). A total of 17 patients required blood transfusion (7.9 percent).

Table 2 . Complications after penile inversion vaginoplasty.

A total of 36 patients (16.8 percent) underwent some form of reoperation.

One hundred eighty-one (85 percent) patients in our series were able to have regular sexual vaginal intercourse, and no individual regretted having undergone GAS.

Penile inversion vaginoplasty is the gold-standard in gender-affirming surgery. It has good functional outcomes, and studies have demonstrated adequate vaginal depths ( 3 ). It is recognized not only as a cosmetic procedure, but as a therapeutic intervention and a medical necessity ( 2 ). We present the largest South-American cohort to date, examining demographic data, intra and postoperative complications.

The mean age of transsexual women who underwent GAS in our study was 32.2 years (range 18–61 years), which is lower than the mean age of patients in studies found in the literature. Two studies indicated that the mean ages of patients at time of GAS were 36.7 years and 41 years, respectively ( 4 , 5 ). Another study reported a mean age at time of GAS of 36 years and found there was a significant decrease in age at the time of GAS from 41 years in 1994 to 35 years in 2015 ( 7 ). According to the authors, this decrease in age is associated with greater tolerance and societal approval regarding individuals with GD ( 7 ).

There was no grade IV or grade V complications. Excessive bleeding noticed postoperatively occurred in 19 patients (8.9 percent) and blood transfusion was required in 17 cases (7.9 percent); all patients who required blood transfusions were operated until July 2011, and the reason for this rate of blood transfusion was not identified.

The most common intraoperative complication was rectal injury, occurring in 4 patients (1.9 percent); in all patients the lesion was promptly identified and corrected in 2 layers absorbable sutures. In 2 of these patients, a rectovaginal fistula became evident, requiring fistulectomy and colonic transit deviation. This is consistent with current literature, in which rectal injury is reported in 0.4–4.5 percent of patients ( 4 , 5 , 8 – 13 ). Goddard et al. suggested carefully checking for enterotomy after prostate and bladder mobilization by digital rectal examination ( 4 ). Gaither et al. ( 14 ) commented that careful dissection that closely follows the urethra along its track from the central tendon of the perineum up through the lower pole of the prostate is critical and only blunt dissection is encouraged after Denonvilliers' fascia is reached. Alternatively, a robotic-assisted approach to penile inversion vaginoplasty may aid in minimizing these complications. The proposed advantages of a robotic-assisted vaginoplasty include safer dissection to minimize the risk of rectal injury and better proximal vaginal fixation. Dy et al. ( 15 ) has had no rectal injuries or fistulae to date in his series of 15 patients, with a mean follow-up of 12 months.

In our series, we observed 44 cases (20.5 percent) of urethral meatus strictures. We credit this complication to the technique used in the initial 5 years of our experience, in which the urethra was shortened and sutured in a circular fashion without spatulation. All cases were treated with meatal dilatation and 11 patients required surgical correction, being performed a Y-V plastic reconstruction of the urethral meatus. In the literature, meatal strictures are relatively rare in male-to-female (MtF) GAS due to the spatulation of the urethra and a simple anastomosis to the external genitalia. Recent systematic reviews show an incidence of five percent in this complication ( 16 , 17 ). Other studies report a wide incidence of meatal stenosis ranging from 1.1 to 39.8 percent ( 4 , 8 , 11 ).

Neovagina introital stricture was observed in 33 patients (15.4 percent) in our study and impedes the possibility of neovaginal penetration and/or adversely affects sexual life quality. In the literature, the reported incidence of introital stenosis range from 6.7 to 14.5 percent ( 4 , 5 , 8 , 9 , 11 – 13 ). According to Hadj-Moussa et al. ( 18 ) a regimen of postoperative prophylactic dilation is crucial to minimize the development of this outcome. At our institution, our protocol for vaginal dilation started seven days after surgery and was performed three to four times a day during the first 3 months and was continued until the individual had regular sexual intercourse. We treated stenosis initially with dilation. In case of no response, we propose a surgical revision with diamond-shaped introitoplasty with relaxing incisions. In recalcitrant cases, we proposed to the patient a secondary vaginoplasty using a full-thickness skin graft of the lower abdomen.

One hundred eighty-one (85 percent) patients were classified as having a “functional vagina,” characterized as the capacity to maintain satisfactory sexual vaginal intercourse, since the mean neovaginal depth was not measured. In a review article, the mean neovaginal depth ranged from 10 to 13.5 cm, with the shallowest neovagina depth at 2.5 cm and the deepest at 18 cm ( 17 ). According to Salim et al. ( 19 ), in terms of postoperative functional outcomes after penile inversion vaginoplasty, a mean percentage of 75 percent (range from 33 to 87 percent) patients were having vaginal intercourse. Hess et al. found that 91.4% of patients who responded to a questionnaire were very satisfied (34.4%), satisfied (37.6%), or mostly satisfied (19.4%) with their sexual function after penile inversion vaginoplasty ( 20 ).

Poor cosmetic appearance of the vulva is common. Amend et al. reported that the most common reason for reoperation was cosmetic correction in the form of mons pubis and mucosa reduction in 50% of patients ( 16 ). We had no patient regrets about performing GAS, although 36 patients (16.8 percent) were reoperated due to cosmetic issues. Gaither et al. propose in order to minimize scarring to use a one-stage surgical approach and the lateralization of surgical scars to the groin ( 14 ). Frequently, cosmetic issues outcomes are often patient driven and preoperative patient education is necessary ( 14 ).

Analyzing the quality of life, in 2016, our health care group (PROTIG) published a study assessing quality of life before and after gender-affirming surgery in 47 patients using the diagnostic tool 100-item WHO Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL-100) ( 21 ). The authors found that GAS promotes the improvement of psychological aspects and social relations. However, even 1 year after GAS, MtF persons continue to report problems in physical and difficulty in recovering their independence. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of QOL and psychosocial outcomes in transsexual people, researchers verified that sex reassignment with hormonal interventions more likely corrects gender dysphoria, psychological functioning and comorbidities, sexual function, and overall QOL compared with sex reassignment without hormonal interventions, although there is a low level of evidence for this ( 22 ). Recently, Castellano et al. assessed QOL in 60 Italian transsexuals (46 transwomen and 14 transmen) at least 2 years after SRS using the WHOQOL-100 (general QOL score and quality of sexual life and quality of body image scores) to focus on the effects of hormonal therapy. Overall satisfaction improved after SRS, and QOL was similar to the controls ( 23 ). Bartolucci et al. evaluated the perception of quality of sexual life using four questions evaluating the sexual facet in individuals with gender dysphoria before SRS and the possible factors associated with this perception. The study showed that approximately half the subjects with gender dysphoria perceived their sexual life as “poor/dissatisfied” or “very poor/very dissatisfied” before SRS ( 24 ).

Our study has some limitations. The total number of operated patients is restricted within the long follow-up period. This is due to a limitation in our health system, which allows only 1 sexual reassignment surgery to be performed per month at our institution. Neovagin depth measurement was not performed routinely in the follow-up of operated patients.

Conclusions

The definitive treatment for patients with gender dysphoria is gender-affirming surgery. Our series demonstrates that GAS is a feasible surgery with low rates of serious complications. We emphasize the high level of functionality of the vagina after the procedure, as well as subjective personal satisfaction. Complications, especially minor ones, are probably underestimated due to the nature of the study, and since this is a surgical population, the results may not be generalizable for all transgender MTF individuals.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

GM: conception and design, data acquisition, data analysis, interpretation, drafting the manuscript, review of the literature, critical revision of the manuscript and factual content, and statistical analysis. ML and TR: conception and design, data interpretation, drafting the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript and factual content, and statistical analysis. DS, KS, AF, AC, PT, AG, and RC: conception and design, data acquisition and data analysis, interpretation, drafting the manuscript, and review of the literature. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by the Fundo de Incentivo à Pesquisa e Eventos (FIPE - Fundo de Incentivo à Pesquisa e Eventos) of Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, Cohen-Kettenis P, DeCuypere G, Feldman J, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-non-conforming people, version 7. Int J Transgend. (2012) 13:165–232. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2011.700873

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Massie JP, Morrison SD, Maasdam JV, Satterwhite T. Predictors of patient satisfaction and postoperative complications in penile inversion vaginoplasty. Plast Reconstruct Surg. (2018) 141:911–921. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004427

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Pan S, Honig SC. Gender-affirming surgery: current concepts. Curr Urol Rep . (2018) 19:62. doi: 10.1007/s11934-018-0809-9

4. Goddard JC, Vickery RM, Qureshi A, Summerton DJ, Khoosal D, Terry TR. Feminizing genitoplasty in adult transsexuals: early and long-term surgical results. BJU Int . (2007) 100:607–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07017.x

5. Rossi NR, Hintz F, Krege S, Rübben H, Vom DF, Hess J. Gender reassignment surgery – a 13 year review of surgical outcomes. Eur Urol Suppl . (2013) 12:e559. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9056(13)61042-8

6. Silva RUM, Abreu FJS, Silva GMV, Santos JVQV, Batezini NSS, Silva Neto B, et al. Step by step male to female transsexual surgery. Int Braz J Urol. (2018) 44:407–8. doi: 10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2017.0044

7. Aydin D, Buk LJ, Partoft S, Bonde C, Thomsen MV, Tos T. Transgender surgery in Denmark from 1994 to 2015: 20-year follow-up study. J Sex Med. (2016) 13:720–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.012

8. Perovic SV, Stanojevic DS, Djordjevic MLJ. Vaginoplasty in male transsexuals using penile skin and a urethral flap. BJU Int. (2001) 86:843–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00934.x

9. Krege S, Bex A, Lümmen G, Rübben H. Male-to-female transsexualism: a technique, results and long-term follow-up in 66 patients. BJU Int. (2001) 88:396–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.2001.02323.x

10. Wagner S, Greco F, Hoda MR, Inferrera A, Lupo A, Hamza A, et al. Male-to-female transsexualism: technique, results and 3-year follow-up in 50 patients. Urol International. (2010) 84:330–3. doi: 10.1159/000288238

11. Reed H. Aesthetic and functional male to female genital and perineal surgery: feminizing vaginoplasty. Semin PlasticSurg. (2011) 25:163–74. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1281486

12. Raigosa M, Avvedimento S, Yoon TS, Cruz-Gimeno J, Rodriguez G, Fontdevila J. Male-to-female genital reassignment surgery: a retrospective review of surgical technique and complications in 60 patients. J Sex Med. (2015) 12:1837–45. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12936

13. Sigurjonsson H, Rinder J, Möllermark C, Farnebo F, Lundgren TK. Male to female gender reassignment surgery: surgical outcomes of consecutive patients during 14 years. JPRAS Open. (2015) 6:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jpra.2015.09.003

14. Gaither TW, Awad MA, Osterberg EC, Murphy GP, Romero A, Bowers ML, et al. Postoperative complications following primary penile inversion vaginoplasty among 330 male-to-female transgender patients. J Urol. (2018) 199:760–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.10.013

15. Dy GW, Sun J, Granieri MA, Zhao LC. Reconstructive management pearls for the transgender patient. Curr. Urol. Rep. (2018) 19:36. doi: 10.1007/s11934-018-0795-y

16. Amend B, Seibold J, Toomey P, Stenzl A, Sievert KD. Surgical reconstruction for male-to-female sex reassignment. Eur Urol. (2013) 64:141–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.12.030

17. Horbach SER, Bouman MB, Smit JM, Özer M, Buncamper ME, Mullender MG. Outcome of vaginoplasty in male-to-female transgenders: a systematic review of surgical techniques. J Sex Med . (2015) 12:1499–512. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12868

18. Hadj-Moussa M, Ohl DA, Kuzon WM. Feminizing genital gender-confirmation surgery. Sex Med Rev. (2018) 6:457–68.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.11.005

19. Salim A, Poh M. Gender-affirming penile inversion vaginoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. (2018) 45:343–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2018.04.001

20. Hess J, Rossi NR, Panic L, Rubben H, Senf W. Satisfaction with male-to-female gender reassignment surgery. DtschArztebl Int. (2014) 111:795–801. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0795

21. Silva DC, Schwarz K, Fontanari AMV, Costa AB, Massuda R, Henriques AA, et al. WHOQOL-100 before and after sex reassignment surgery in brazilian male-to-female transsexual individuals. J Sex Med. (2016) 13:988–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.03.370

22. Murad MH, Elamin MB, Garcia MZ, Mullan RJ, Murad A, Erwin PJ, et al. Hormonal therapy and sex reassignment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life and psychosocial outcomes. Clin Endocrinol . (2010) 72:214–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03625.x

23. Castellano E, Crespi C, Dell'Aquila C, Rosato R, Catalano C, Mineccia V, et al. Quality of life and hormones after sex reassignment surgery. J Endocrinol Invest . (2015) 38:1373–81. doi: 10.1007/s40618-015-0398-0

24. Bartolucci C, Gómez-Gil E, Salamero M, Esteva I, Guillamón A, Zubiaurre L, et al. Sexual quality of life in gender-dysphoric adults before genital sex reassignment surgery. J Sex Med . (2015) 12:180–8. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12758

Keywords: transsexualism, gender dysphoria, gender-affirming genital surgery, penile inversion vaginoplasty, surgical outcome

Citation: Moisés da Silva GV, Lobato MIR, Silva DC, Schwarz K, Fontanari AMV, Costa AB, Tavares PM, Gorgen ARH, Cabral RD and Rosito TE (2021) Male-to-Female Gender-Affirming Surgery: 20-Year Review of Technique and Surgical Results. Front. Surg. 8:639430. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2021.639430

Received: 17 December 2020; Accepted: 22 March 2021; Published: 05 May 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Moisés da Silva, Lobato, Silva, Schwarz, Fontanari, Costa, Tavares, Gorgen, Cabral and Rosito. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gabriel Veber Moisés da Silva, veber.gabriel@gmail.com

This article is part of the Research Topic

Gender Dysphoria: Diagnostic Issues, Clinical Aspects and Health Promotion

Long-term Outcomes After Gender-Affirming Surgery: 40-Year Follow-up Study

Affiliations.

- 1 From the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.

- 2 School of Medicine.

- 3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

- 4 Department of Urology.

- 5 Department of Psychiatry and Neurobehavioral Sciences, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

- PMID: 36149983

- DOI: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000003233

Background: Gender dysphoria is a condition that often leads to significant patient morbidity and mortality. Although gender-affirming surgery (GAS) has been offered for more than half a century with clear significant short-term improvement in patient well-being, few studies have evaluated the long-term durability of these outcomes.

Methods: Chart review identified 97 patients who were seen for gender dysphoria at a tertiary care center from 1970 to 1990 with comprehensive preoperative evaluations. These evaluations were used to generate a matched follow-up survey regarding their GAS, appearance, and mental/social health for standardized outcome measures. Of 97 patients, 15 agreed to participate in the phone interview and survey. Preoperative and postoperative body congruency score, mental health status, surgical outcomes, and patient satisfaction were compared.

Results: Both transmasculine and transfeminine groups were more satisfied with their body postoperatively with significantly less dysphoria. Body congruency score for chest, body hair, and voice improved significantly in 40 years' postoperative settings, with average scores ranging from 84.2 to 96.2. Body congruency scores for genitals ranged from 67.5 to 79 with free flap phalloplasty showing highest scores. Long-term overall body congruency score was 89.6. Improved mental health outcomes persisted following surgery with significantly reduced suicidal ideation and reported resolution of any mental health comorbidity secondary to gender dysphoria.

Conclusion: Gender-affirming surgery is a durable treatment that improves overall patient well-being. High patient satisfaction, improved dysphoria, and reduced mental health comorbidities persist decades after GAS without any reported patient regret.

Copyright © 2022 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

- Follow-Up Studies

- Gender Dysphoria* / surgery

- Sex Reassignment Surgery*

- Transgender Persons* / psychology

- Transsexualism* / psychology

- FIND A PROVIDER

I'm a Candidate

I'm a Provider

Log In / Sign Up

I'm a candidate

Provider login

I'm a provider

List your practice

FTM Gender Confirmation: Genital Construction

The specifics, the takeaway.

Download the app

As part of a transgender individual’s transition, genital reassignment surgery alters female genitalia into male genitalia.

Written By: Erin Storm, PA-C

Published: October 07, 2021

Last updated: February 18, 2022

- Procedure Overview

- Ideal Candidate

- Side Effects

- Average Cost

thumbs-up Pros

- Can Help Complete A Gender Affirmation Journey

thumbs-down Cons

- Potentially Cost Prohibitive

Invasiveness Score

Invasiveness is graded based on factors such as anesthesia practices, incisions, and recovery notes common to this procedure.

Average Recovery

Application.

Surgical Procedure

$ 50000 - $ 100000

What is a female to male (FTM) gender reassignment surgery?

Female to male (FTM) gender reassignment surgery is also known as sex reassignment surgery (SRS), genital construction, and generally as gender confirmation surgery. These plastic surgery procedures are used by transgender patients to remove and alter female genitalia into traditional male genitalia.

Plastic surgeons will usually perform a hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy to remove the uterus and ovaries. A vaginoplasty or vaginectomy will close the vagina, the erectile tissue of the clitoris is released and with the mons portion of the pubic area a neo-phallus is created (phalloplasty or metoidioplasty). The labia majora then become the scrotum (scrotoplasty), bilateral testicular implants are placed, and finally the urethra is lengthened through the newly created penile tissue.

Typically gender reassignment surgery is performed as a last step in a transgender individuals transition journey. Guidelines on standards of care from The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) state candidates must have letters of recommendation from their mental health professional and healthcare provider, have been living full time as a man for one year, and have completed one year of hormonal therapy to be eligible.