Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8 Origins of Greek Philosophy

The pre-socratics.

Review Video — The Ionian Origins of Greek Philosophy by Daniel Riaño (11)

About 600 BCE, the Greek cities of Ionia were the intellectual and cultural leaders of Greece and the number one sea-traders of the Mediterranean. Miletus, the southernmost Ionian city, was the wealthiest of Greek cities and the main focus of the “Ionian awakening” — a name for the initial phase of classical Greek civilization, coincidental with the birth of Greek philosophy.

The first group of Greek philosophers is a triad of Milesian thinkers: Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes. Their main contribution was the development and application of theory purely based on empirical observation of natural phenomena. They seemed to all agree on the notion that all things come from a single “primal origin or substance.” Thales believed it was water; Anaximander said it was a substance different from all other known substances, “infinite, eternal and ageless;” and Anaximenes claimed it was air.

Observation was important among the Milesian school. Thales predicted an eclipse, which took place in 585 BCE, and it seems he had been able to calculate the distance of a ship at sea from observations taken at two points. Anaximander, based on the fact that human infants are helpless at birth, argued that if the first human had somehow appeared on earth as an infant, it would not have survived: therefore, humans have evolved from other animals whose offspring are fitter. The science among Milesians was stronger than their philosophy and somewhat rudimentary, but it encouraged observation in many subsequent thinkers and was also a good stimulus to approach in a rational fashion many of the traditional questions that had previously been answered through myth, thus ushering in the epistemological and metaphysical world of the later philosophers. (3)

Aristotle, Metaphysics

Reading from Aristotle, Metaphysics

Book One: Section 1.983b–1.990a.

Most of the earliest philosophers conceived only of material principles as underlying all things. That of which all things consist, from which they first come and into which on their destruction they are ultimately resolved, of which the essence persists although modified by its affections — this, they say, is an element and principle of existing things. Hence, they believe that nothing is either generated or destroyed, since this kind of primary entity always persists. Similarly, we do not say that Socrates comes into being absolutely when he becomes handsome or cultured, nor that he is destroyed when he loses these qualities; because the substrate, Socrates himself, persists. In the same way nothing else is generated or destroyed; for there is some one entity (or more than one) which always persists and from which all other things are generated. All are not agreed, however, as to the number and character of these principles. (12)

The Milesians, Thales and Anaximander

Thales, the founder of this school of philosophy, says the permanent entity is water (which is why he also propounded that the earth floats on water). Presumably, he derived this assumption from seeing that the nutriment of everything is moist, and that heat itself is generated from moisture and depends upon it for its existence (and that from which a thing is generated is always its first principle). He derived his assumption, then, from this; and also from the fact that the seeds of everything have a moist nature, whereas water is the first principle of the nature of moist things. (12)

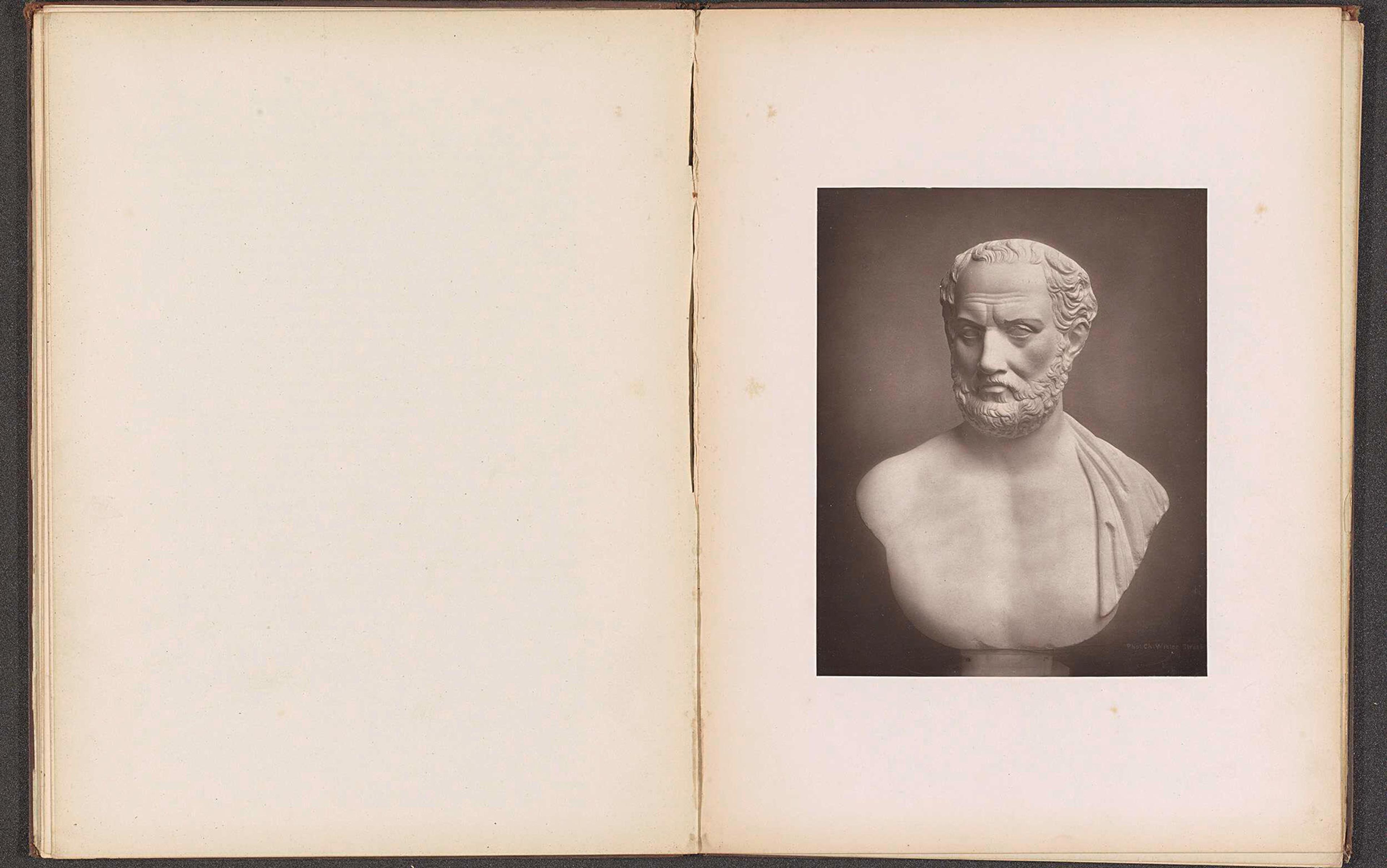

ANAXIMANDER (c 610–c 546 BCE) of Miletus was a student of Thales and recent scholarship argues that he, rather than Thales, should be considered the first western philosopher owing to the fact that we have a direct and undisputed quote from Anaximander while we have nothing written by Thales. Anaximander invented the idea of models, drew the first map of the world in Greece, and is said to have been the first to write a book of prose. He traveled extensively and was highly regarded by his contemporaries. Among his major contributions to philosophical thought was his claim that the ‘basic stuff’ of the universe was the apeiron, the infinite and boundless, a philosophical and theological claim which is still debated among scholars today and which, some argue, provided Plato with the basis for his cosmology.

Simplicius writes, Of those who say that it is one, moving, and infinite, Anaximander, son of Praxiades, a Milesian, the successor and pupil of Thales, said that the principle and element of existing things was the apeiron [indefinite or infinite] being the first to introduce this name of the material principle. He says that it is neither water nor any other of the so-called elements but some other apeiron nature, from which come into being all the heavens and the worlds in them. And the source of coming-to-be for existing things is that into which destruction, too, happens ‘according to necessity; for they pay penalty and retribution to each other for their injustice according to the assessment of time,’ as he describes it in these rather poetical terms. It is clear that he, seeing the changing of the four elements into each other, thought it right to make none of these the substratum, but something else besides these; and he produces coming-to-be not through the alteration of the element, but by the separation off of the opposites through the eternal motion. ( Physics , 24)

This statement by Anaximander regarding elements paying penalty to each other according to the assessment of time is considered the oldest known piece of written Western philosophy.

Thales claimed that the First Cause of all things was water but Anaximander, recognizing that water was another of the earthly elements, believed that the First Cause had to come from something beyond such an element. His answer to the question of `Where did everything come from?’ was the apeiron, the boundless, but what exactly he meant by `the boundless’ has given rise to the centuries-old debate. Does `the boundless’ refer to a spatial or temporal quality or does it refers to something inexhaustible and undefined?

While it is impossible to say with certainty what Anaximander meant, a better understanding can be gained through his `long since’ argument, which Aristotle phrases this way in his Physics .

Some make this First Cause (namely, that which is additional to the elements) the Boundless, but not air or water, lest the others should be destroyed by one of them, being boundless; for they are opposite to one another (the air, for instance, is cold, the water wet, and the fire hot). If any of them should be boundless, it would long since have destroyed the others; but now there is, they say, something other from which they are all generated. (204b25–29)

In other words, none of the observable elements could be the First Cause because all observable elements are changeable and, were one to be more powerful than the others, it would have long since eradicated them. As observed, however, the elements of the earth seem to be in balance with each other, none of them holding the upper hand and, therefore, some other source must be looked to for a First Cause. In making this claim, Anaximander becomes the first known philosopher to work in abstract, rather than natural, philosophy and the first metaphysician even before the term `metaphysics’ was coined.

He charted the heavens, traveled widely, was the first to claim the earth floated in space, and the first to posit an unobservable First Cause (which, whether it influenced Plato, certainly shares similarities with Aristotle’s Prime Mover). Diogenes Laertius writes, “Apollodorus, in his Chronicles , states that in the second year of the fifty-eighth Olympiad, [Anaximander] was sixty-four years old. And soon after he died, having flourished much about the same time as Polycrates, the tyrant, of Samos.” A statue was erected at Miletus in Anaximander’s honor. (13)

The Eleatics Parmenides and Zeno of Elea

Parmenides (c. 485 BCE) of Elea was a Greek philosopher from the colony of Elea in southern Italy. He is known as the founder of the Eleatic School of philosophy, which taught a strict Monistic view of reality. Philosophical Monism is the belief that all of the sensible world is of one, basic substance and being, un-created and indestructible.

Parmenides was a younger contemporary of Heraclitus who claimed that all things are constantly in motion and change (that the basic `stuff’ of life is change itself). Parmenides’ thought could not be further removed from that of Heraclitus in that Parmenides claimed nothing moved, change was impossibility, and that human sense perception could not be relied upon for an apprehension of Truth.

The Philosopher of Changeless Being

According to Parmenides, “There is a way which is and a way which is not” (a way of fact, or truth, and a way of opinion about things) and one must come to an understanding of the way “which is” to understand the nature of life. Known as the Philosopher of Changeless Being, Parmenides’ insistence on an eternal, single Truth and his repudiation of relativism and mutability would greatly influence the young philosopher Plato and, through him, Aristotle (though the latter would interpret Parmenides’ Truth quite differently than his master did). Plato devoted a dialogue to the man, the Parmenides, in which Parmenides and his student, Zeno, come to Athens and instruct a young Socrates in philosophical wisdom. This is quite an homage to the thought of Parmenides in that, in most dialogues, Plato presents Socrates as the wise questioner who needs no instruction from anyone. While Parmenides was an older contemporary of Socrates, it is doubtful the two men ever met.

Zeno of Elea

Zeno of Elea was Parmenides’ most famous student and wrote forty paradoxes in defense of Parmenides’ claim that change — and even motion — were illusions which one must disregard in order to know the nature of oneself and that of the universe. Zeno’s work was intended to clarify and defend Parmenides’ statements, such as… reality is One. Nothing is capable of inherently changing in any significant fashion because the very substance of reality is unchangeable and ‘nothingness’ cannot be comprehended.

Nothing Can Come from Nothing

Even so, it seems that Parmenides’ ideas themselves were hard to comprehend for his listeners, necessitating Zeno’s mathematical paradoxes. Parmenides’ main point, however, was simply that nothing could come from nothing and that `being’ must have always existed.

Being & Not Being

Simply put, his argument is that since ‘something’ cannot come from ‘nothing’ then ‘something’ must have always existed in order to produce the sensible world. This world we perceive, then, is of one substance – that same substance from which it came – and we who inhabit it share in this same unity of substance. Therefore, if it should appear that a person is born from `nowhere’ or that one dies and goes somewhere else, both of these perceptions must be wrong since that which is now can never have been ‘not’ nor can it ever ‘not be’. In this, Parmenides may be developing ideas from the earlier philosopher Pythagoras (c. 571–c.497 BCE) who claimed the soul is immortal and returns to the sensible world repeatedly through reincarnation. If so, however, Parmenides very radically departed from Pythagorean thought which allows that there is plurality present in our reality. To Parmenides, and his disciples of the Eleatic School, such a claim would be evidence of belief in the senses which, they insisted, could never be trusted to reveal the truth. The Eleatic principle that all is one, and unchanging, exerted considerable influence on later philosophers and schools of thought. Besides Plato (who, in addition to the dialogue, Parmenides also addressed Eleatic concepts in his dialogues of the Sophist and the Statesman) the famous Sophist Gorgias employed Eleatic reasoning and principles in his work as Aristotle would also do later, principally in his Metaphysics. (14)

Pluralists and Atomists

Empedocles , from the ancient Greek city of Akragas, (Agrigentum in Latin), modern Agrigento, in Sicily, appears to have been partly in agreement with the Eleatic School, partly in opposition to it. On the one hand, he maintained the unchangeable nature of substance; on the other, he supposes a plurality of such substances — i.e. four classical elements, earth, water, air, and fire. Of these the world is built up, by the agency of two ideal motive forces — love as the cause of union, strife as the cause of separation.

The first explicitly materialistic system was formed by Leucippus (5 th century BCE) and his pupil Democritus of Abdera (460–370 BCE) from Thrace. This was the doctrine of atoms — small primary bodies infinite in number, indivisible and imperishable, qualitatively similar, but distinguished by their shapes. Moving eternally through the infinite void, they collide and unite, thus generating objects which differ in accordance with the varieties, in number, size, shape, and arrangement, of the atoms which compose them. (15)

Another View: Creation in the Philosophy of Ancient India: Rig Veda

The philosophical question of cosmogenesis has been approached in many different ways in Greece as we have seen in the beginning of this Module; here is an example of the question’s response from another perspective. (1)

“Then was neither nonexistent nor existent: there was no realm of air, no sky beyond it. What covered in, and where? And what gave shelter? Was water there, unfathomed depth of water? The ONE breathed without air by self-impulse; through the heat of tapas (desire) was manifest (1) Who verily knows and who can here declare it, whence it was born and whence comes this creation? The Gods are later than this world’s production. Who knows then whence it first came into being? He, the first origin of this creation, whether he formed it all or did not form it, Whose eye controls this world in highest heaven, he verily knows it, or perhaps he knows not.” (Rig-Veda 10.129.1-7)

There is another account on how the universe started, which has no equivalent in any other tradition. The universe is actually the dream of a god who after 100 Brahma years, dissolves himself into a dreamless sleep, and the universe dissolves with him. After another 100 Brahma years, he recomposes himself and begins to dream again the great cosmic dream. Meanwhile, there are infinite other universes elsewhere, each of them being dreamt by its own god. (16)

What might each of these interpretations conclude should their arguments continue to develop? (The question is rhetorical. You need not consider it an assignment, but rather keep it in mind as we move to the next Module.) (1)

Philosophy in the Humanities Copyright © by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Essays in ancient Greek philosophy

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

245 Previews

12 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station46.cebu on March 12, 2021

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Essays in Ancient Greek Philosophy II

Alternative formats available from:.

- Google Play

View Table of Contents

Request Desk or Examination Copy Request a Media Review Copy

- Share this:

Table of contents

Introduction

Journal and Standard Reference Abbreviations

I. Pre-Socratics

John Ferguson

Xenophanes' Scepticism

James H. Lesher

Parmenides' Way of Truth and B16

Jackson P. Hershbell

"Nothing" as "Not-being": Some Literary Contexts that Bear on Plato

Alexander P. D. Mourelatos

Anaxagoras in Response to Parmenides

David J. Furley

Anaxagoras and Epicurus

Margaret E. Reesor

Form and Content in Gorgias' Helen and Palamedes : Phetoric, Philosophy, Inconsistency and Valid Argument in some Greek Thinkers

Arthur W. H. Adkins

Socrates and Prodicus in the Clouds

Z. Philip Ambrose

The Socratic Problem: Some Second Thoughts

Eric A. Havelock

Doctrine and Dramatic Dates of Plato's Dialogues

Robert S. Brumbaugh

The Tragic and Comic Poet of the Symposium

Diskin Clay

Charmides' First Definition: Sophrosyne as Quietness

L. A. Kosman

The Arguments in the Phaedo Concerning the Thesis That the Soul Is a Harmonia

C. C. W. Taylor

The Form of the Good in Plato's Republic

Gerasimos Santas

Logos in the Theaetetus and the Sophist

Edward M. Galligan

Episteme and Doxa : Some Reflections on Eleatic and Heraclitean Themes in Plato

Robert G. Turnbull

III. Aristotle

On the Antecedents of Aristotle's Bipartite Psychology

William W. Fortenbaugh

Heart and Soul in Aristotle

Theodore Tracy

Eidos as Norm in Aristotle's Biology

Anthony Preus

Intellectualism in Aristotle

Aristotle's Analysis of Change and Plato's Theory of Transcendent Ideas

Chung-Hwan Chen

The Fifth Element in Aristotle's De Philosophia : A Critical Reexamination

David E. Hahm

IV. Post-Aristotelian Philosophy

Problems in Epicurean Physics

David Konstan

Zeno and Stoic Consistency

John M. Rist

The Stoic Conception of Fate

Josiah B. Gould

Plotinus and Paranormal Phenomena

Richard T. Wallis

Metriopatheia and Apatheia : Some Reflections on a Controversy in Later Greek Ethics

John M. Dillon

Description

Essays in Ancient Greek Philosophy, Volume Two, reflects the refinements in scholarship and philosophical analysis that have impacted classical philosophy in recent years. It is a selection of the best papers presented at the annual meetings of the Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy during the last decade. The papers presented indicate a shift in accent from a predominant preference for the application of linguistic methods in the study of texts to a more intensified concern for contextual examinations of philosophical concepts. The works of both younger scholars and senior authors show a more liberal, yet controlled, use of historical and cultural elements in interpretation. The papers also reflect advances in scholarship in adjacent fields of Greek studies.

From pre-Socratic to post-Aristotelian philosophers, the papers in this volume are intended to stimulate interest in the major accomplishments of classical philosophers. This work augments its companion volume Essays in Ancient Greek Philosophy.

John P. Anton is Professor of Philosophy at the University of South Florida. Anthony Preus is Professor of Philosophy at the State University of New York at Binghamton.

"The essays are a genuine contribution to the field. They provide a number of fresh insights and uniformly have something intellectually important to say. " — Dr. Aldo Tassi, Loyola College in Maryland

1.1 What Is Philosophy?

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify sages (early philosophers) across historical traditions.

- Explain the connection between ancient philosophy and the origin of the sciences.

- Describe philosophy as a discipline that makes coherent sense of a whole.

- Summarize the broad and diverse origins of philosophy.

It is difficult to define philosophy. In fact, to do so is itself a philosophical activity, since philosophers are attempting to gain the broadest and most fundamental conception of the world as it exists. The world includes nature, consciousness, morality, beauty, and social organizations. So the content available for philosophy is both broad and deep. Because of its very nature, philosophy considers a range of subjects, and philosophers cannot automatically rule anything out. Whereas other disciplines allow for basic assumptions, philosophers cannot be bound by such assumptions. This open-endedness makes philosophy a somewhat awkward and confusing subject for students. There are no easy answers to the questions of what philosophy studies or how one does philosophy. Nevertheless, in this chapter, we can make some progress on these questions by (1) looking at past examples of philosophers, (2) considering one compelling definition of philosophy, and (3) looking at the way academic philosophers today actually practice philosophy.

Historical Origins of Philosophy

One way to begin to understand philosophy is to look at its history. The historical origins of philosophical thinking and exploration vary around the globe. The word philosophy derives from ancient Greek, in which the philosopher is a lover or pursuer ( philia ) of wisdom ( sophia ). But the earliest Greek philosophers were not known as philosophers; they were simply known as sages . The sage tradition provides an early glimpse of philosophical thought in action. Sages are sometimes associated with mathematical and scientific discoveries and at other times with their political impact. What unites these figures is that they demonstrate a willingness to be skeptical of traditions, a curiosity about the natural world and our place in it, and a commitment to applying reason to understand nature, human nature, and society better. The overview of the sage tradition that follows will give you a taste of philosophy’s broad ambitions as well as its focus on complex relations between different areas of human knowledge. There are some examples of women who made contributions to philosophy and the sage tradition in Greece, India, and China, but these were patriarchal societies that did not provide many opportunities for women to participate in philosophical and political discussions.

The Sages of India, China, Africa, and Greece

In classical Indian philosophy and religion, sages play a central role in both religious mythology and in the practice of passing down teaching and instruction through generations. The Seven Sages, or Saptarishi (seven rishis in the Sanskrit language), play an important role in sanatana dharma , the eternal duties that have come to be identified with Hinduism but that predate the establishment of the religion. The Seven Sages are partially considered wise men and are said to be the authors of the ancient Indian texts known as the Vedas . But they are partly mythic figures as well, who are said to have descended from the gods and whose reincarnation marks the passing of each age of Manu (age of man or epoch of humanity). The rishis tended to live monastic lives, and together they are thought of as the spiritual and practical forerunners of Indian gurus or teachers, even up to today. They derive their wisdom, in part, from spiritual forces, but also from tapas , or the meditative, ascetic, and spiritual practices they perform to gain control over their bodies and minds. The stories of the rishis are part of the teachings that constitute spiritual and philosophical practice in contemporary Hinduism.

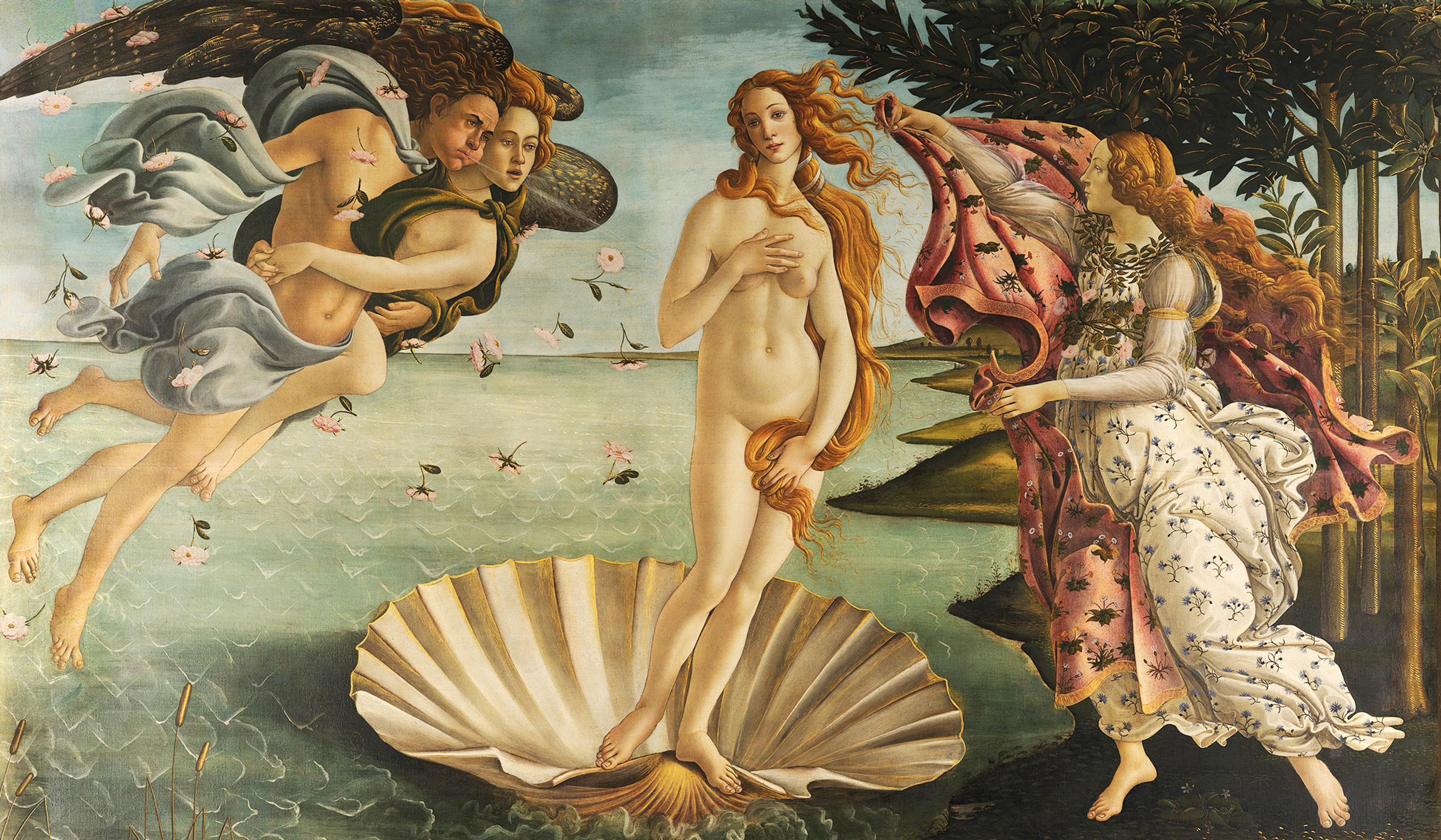

Figure 1.2 depicts a scene from the Matsya Purana, where Manu, the first man whose succession marks the prehistorical ages of Earth, sits with the Seven Sages in a boat to protect them from a mythic flood that is said to have submerged the world. The king of serpents guides the boat, which is said to have also contained seeds, plants, and animals saved by Manu from the flood.

Despite the fact that classical Indian culture is patriarchal, women figures play an important role in the earliest writings of the Vedic tradition (the classical Indian religious and philosophical tradition). These women figures are partly connected to the Indian conception of the fundamental forces of nature—energy, ability, strength, effort, and power—as feminine. This aspect of God was thought to be present at the creation of the world. The Rig Veda, the oldest Vedic writings, contains hymns that tell the story of Ghosha, a daughter of Rishi Kakshivan, who had a debilitating skin condition (probably leprosy) but devoted herself to spiritual practices to learn how to heal herself and eventually marry. Another woman, Maitreyi, is said to have married the Rishi Yajnavalkya (himself a god who was cast into mortality by a rival) for the purpose of continuing her spiritual training. She was a devoted ascetic and is said to have composed 10 of the hymns in the Rig Veda. Additionally, there is a famous dialogue between Maitreyi and Yajnavalkya in the Upanishads (another early, foundational collection of texts in the Vedic tradition) about attachment to material possessions, which cannot give a person happiness, and the achievement of ultimate bliss through knowledge of the Absolute (God).

Another woman sage named Gargi also participates in a celebrated dialogue with Yajnavalkya on natural philosophy and the fundamental elements and forces of the universe. Gargi is characterized as one of the most knowledgeable sages on the topic, though she ultimately concedes that Yajnavalkya has greater knowledge. In these brief episodes, these ancient Indian texts record instances of key women who attained a level of enlightenment and learning similar to their male counterparts. Unfortunately, this early equality between the sexes did not last. Over time Indian culture became more patriarchal, confining women to a dependent and subservient role. Perhaps the most dramatic and cruel example of the effects of Indian patriarchy was the ritual practice of sati , in which a widow would sometimes immolate herself, partly in recognition of the “fact” that following the death of her husband, her current life on Earth served no further purpose (Rout 2016). Neither a widow’s in-laws nor society recognized her value.

In similar fashion to the Indian tradition, the sage ( sheng ) tradition is important for Chinese philosophy . Confucius , one of the greatest Chinese writers, often refers to ancient sages, emphasizing their importance for their discovery of technical skills essential to human civilization, for their role as rulers and wise leaders, and for their wisdom. This emphasis is in alignment with the Confucian appeal to a well-ordered state under the guidance of a “ philosopher-king .” This point of view can be seen in early sage figures identified by one of the greatest classical authors in the Chinese tradition, as the “Nest Builder” and “Fire Maker” or, in another case, the “Flood Controller.” These names identify wise individuals with early technological discoveries. The Book of Changes , a classical Chinese text, identifies the Five (mythic) Emperors as sages, including Yao and Shun, who are said to have built canoes and oars, attached carts to oxen, built double gates for defense, and fashioned bows and arrows (Cheng 1983). Emperor Shun is also said to have ruled during the time of a great flood, when all of China was submerged. Yü is credited with having saved civilization by building canals and dams.

These figures are praised not only for their political wisdom and long rule, but also for their filial piety and devotion to work. For instance, Mencius, a Confucian philosopher, relates a story of Shun’s care for his blind father and wicked stepmother, while Yü is praised for his selfless devotion to work. In these ways, the Chinese philosophical traditions, such as Confucianism and Mohism, associate key values of their philosophical enterprises with the great sages of their history. Whether the sages were, in fact, actual people or, as many scholars have concluded, mythical forebearers, they possessed the essential human virtue of listening and responding to divine voices. This attribute can be inferred from the Chinese script for sheng , which bears the symbol of an ear as a prominent feature. So the sage is one who listens to insight from the heavens and then is capable of sharing that wisdom or acting upon it to the benefit of his society (Cheng 1983). This idea is similar to one found in the Indian tradition, where the most important texts, the Vedas, are known as shruti , or works that were heard through divine revelation and only later written down.

Although Confucianism is a venerable world philosophy, it is also highly patriarchal and resulted in the widespread subordination of women. The position of women in China began to change only after the Communist Revolution (1945–1952). While some accounts of Confucianism characterize men and women as emblematic of two opposing forces in the natural world, the Yin and Yang, this view of the sexes developed over time and was not consistently applied. Chinese women did see a measure of independence and freedom with the influence of Buddhism and Daoism, each of which had a more liberal view of the role of women (Adler 2006).

A detailed and important study of the sage tradition in Africa is provided by Henry Odera Oruka (1990), who makes the case that prominent folk sages in African tribal history developed complex philosophical ideas. Oruka interviewed tribal Africans identified by their communities as sages, and he recorded their sayings and ideas, confining himself to those sayings that demonstrated “a rational method of inquiry into the real nature of things” (Oruka 1990, 150). He recognized a tension in what made these sages philosophically interesting: they articulated the received wisdom of their tradition and culture while at the same time maintaining a critical distance from that culture, seeking a rational justification for the beliefs held by the culture.

Connections

The chapter on the early history of philosophy covers this topic in greater detail.

Among the ancient Greeks, it is common to identify seven sages. The best-known account is provided by Diogenes Laërtius, whose text Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers is a canonical resource on early Greek philosophy. The first and most important sage is Thales of Miletus . Thales traveled to Egypt to study with the Egyptian priests, where he became one of the first Greeks to learn astronomy. He is known for bringing back to Greece knowledge of the calendar, dividing the year into 365 days, tracking the progress of the sun from solstice to solstice, and—somewhat dramatically—predicting a solar eclipse in 585 BCE. The eclipse occurred on the day of a battle between the Medes and Lydians. It is possible that Thales used knowledge of Babylonian astronomical records to guess the year and location of the eclipse. This mathematical and astronomical feat is one of Thales’s several claims to sagacity. In addition, he is said to have calculated the height of the pyramids using the basic geometry of similar triangles and measuring shadows at a certain time of day. He is also reported to have predicted a particularly good year for olives: he bought up all the olive presses and then made a fortune selling those presses to farmers wanting to turn their olives into oil. Together, these scientific and technical achievements suggest that at least part of Thales’s wisdom can be attributed to a very practical, scientific, and mathematical knowledge of the natural world. If that were all Thales was known for, he might be called the first scientist or engineer. But he also made more basic claims about the nature and composition of the universe; for instance, he claimed that all matter was fundamentally made of up water. He also argued that everything that moved on its own possessed a soul and that the soul itself was immortal. These claims demonstrate a concern about the fundamental nature of reality.

Another of the seven sages was Solon , a famed political leader. He introduced the “Law of Release” to Athens, which cancelled all personal debts and freed indentured servants, or “debt-slaves” who had been consigned to service based on a personal debt they were unable to repay. In addition, he established a constitutional government in Athens with a representative body, a procedure for taxation, and a series of economic reforms. He was widely admired as a political leader but voluntarily stepped down so that he would not become a tyrant. He was finally forced to flee Athens when he was unable to persuade the members of the Assembly (the ruling body) to resist the rising tyranny of one of his relatives, Pisistratus. When he arrived in exile, he was reportedly asked whom he considered to be happy, to which he replied, “One ought to count no man happy until he is dead.” Aristotle interpreted this statement to mean that happiness was not a momentary experience, but a quality reflective of someone’s entire life.

Beginnings of Natural Philosophy

The sage tradition is a largely prehistoric tradition that provides a narrative about how intellect, wisdom, piety, and virtue led to the innovations central to flourishing of ancient civilizations. Particularly in Greece, the sage tradition blends into a period of natural philosophy, where ancient scientists or philosophers try to explain nature using rational methods. Several of the early Greek schools of philosophy were centered on their respective views of nature. Followers of Thales, known as the Milesians , were particularly interested in the underlying causes of natural change. Why does water turn to ice? What happens when winter passes into spring? Why does it seem like the stars and planets orbit Earth in predictable patterns? From Aristotle we know that Thales thought there was a difference between material elements that participate in change and elements that contain their own source of motion. This early use of the term element did not have the same meaning as the scientific meaning of the word today in a field like chemistry. But Thales thought material elements bear some fundamental connection to water in that they have the capacity to move and alter their state. By contrast, other elements had their own internal source of motion, of which he cites the magnet and amber (which exhibits forces of static electricity when rubbed against other materials). He said that these elements have “soul.” This notion of soul, as a principle of internal motion, was influential across ancient and medieval natural philosophy. In fact, the English language words animal and animation are derived from the Latin word for soul ( anima ).

Similarly, early thinkers like Xenophanes began to formulate explanations for natural phenomena. For instance, he explained rainbows, the sun, the moon, and St. Elmo’s fire (luminous, electrical discharges) as apparitions of the clouds. This form of explanation, describing some apparent phenomenon as the result of an underlying mechanism, is paradigmatic of scientific explanation even today. Parmenides, the founder of the Eleatic school of philosophy, used logic to conclude that whatever fundamentally exists must be unchanging because if it ever did change, then at least some aspect of it would cease to exist. But that would imply that what exists could not exist—which seems to defy logic. Parmenides is not saying that there is no change, but that the changes we observe are a kind of illusion. Indeed, this point of view was highly influential, not only for Plato and Aristotle, but also for the early atomists, like Democritus , who held that all perceived qualities are merely human conventions. Underlying all these appearances, Democritus reasoned, are only atomic, unchanging bits of matter flowing through a void. While this ancient Greek view of atoms is quite different from the modern model of atoms, the very idea that every observable phenomenon has a basis in underlying pieces of matter in various configurations clearly connects modern science to the earliest Greek philosophers.

Along these lines, the Pythagoreans provide a very interesting example of a community of philosophers engaged in understanding the natural world and how best to live in it. You may be familiar with Pythagoras from his Pythagorean theorem, a key principle in geometry establishing a relationship between the sides of a right-angled triangle. Specifically, the square formed by the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right angle) is equal to the sum of the two squares formed by the remaining two sides. In the figure below, the area of the square formed by c is equal to the sum of the areas of the squares formed by a and b. The figure represents how Pythagoras would have conceptualized the theorem.

The Pythagoreans were excellent mathematicians, but they were more interested in how mathematics explained the natural world. In particular, Pythagoras recognized relationships between line segments and shapes, such as the Pythagorean theorem describes, but also between numbers and sounds, by virtue of harmonics and the intervals between notes. Similar regularities can be found in astronomy. As a result, Pythagoras reasoned that all of nature is generated according to mathematical regularities. This view led the Pythagoreans to believe that there was a unified, rational structure to the universe, that the planets and stars exhibit harmonic properties and may even produce music, that musical tones and harmonies could have healing powers, that the soul is immortal and continuously reincarnated, and that animals possess souls that ought to be respected and valued. As a result, the Pythagorean community was defined by serious scholarship as well as strict rules about diet, clothing, and behavior.

Additionally, in the early Pythagorean communities, it was possible for women to participate and contribute to philosophical thought and discovery. Pythagoras himself was said to have been inspired to study philosophy by the Delphic priestess Themistoclea. His wife Theano is credited with contributing to important discoveries in the realms of numbers and optics. She is said to have written a treatise, On Piety , which further applies Pythagorean philosophy to various aspects of practical life (Waithe 1987). Myia, the daughter of this illustrious couple, was also an active and productive part of the community. At least one of her letters has survived in which she discusses the application of Pythagorean philosophy to motherhood. The Pythagorean school is an example of how early philosophical and scientific thinking combines with religious, cultural, and ethical beliefs and practices to embrace many different aspects of life.

How It All Hangs Together

Closer to the present day, in 1962, Wilfrid Sellars , a highly influential 20th-century American philosopher, wrote a chapter called “Philosophy and the Scientific Image of Man” in Frontiers of Science and Philosophy . He opens the essay with a dramatic and concise description of philosophy: “The aim of philosophy, abstractly formulated, is to understand how things in the broadest possible sense of the term hang together in the broadest possible sense of the term.” If we spend some time trying to understand what Sellars means by this definition, we will be in a better position to understand the academic discipline of philosophy. First, Sellars emphasizes that philosophy’s goal is to understand a very wide range of topics—in fact, the widest possible range. That is to say, philosophers are committed to understanding everything insofar as it can be understood. This is important because it means that, on principle, philosophers cannot rule out any topic of study. However, for a philosopher not every topic of study deserves equal attention. Some things, like conspiracy theories or paranoid delusions, are not worth studying because they are not real. It may be worth understanding why some people are prone to paranoid delusions or conspiratorial thinking, but the content of these ideas is not worth investigating. Other things may be factually true, such as the daily change in number of the grains of sand on a particular stretch of beach, but they are not worth studying because knowing that information will not teach us about how things hang together. So a philosopher chooses to study things that are informative and interesting—things that provide a better understanding of the world and our place in it.

To make judgments about which areas are interesting or worthy of study, philosophers need to cultivate a special skill. Sellars describes this philosophical skill as a kind of know-how (a practical, engaged type of knowledge, similar to riding a bike or learning to swim). Philosophical know-how, Sellars says, has to do with knowing your way around the world of concepts and being able to understand and think about how concepts connect, link up, support, and rely upon one another—in short, how things hang together. Knowing one’s way around the world of concepts also involves knowing where to look to find interesting discoveries and which places to avoid, much like a good fisherman knows where to cast his line. Sellars acknowledges that other academics and scientists know their way around the concepts in their field of study much like philosophers do. The difference is that these other inquirers confine themselves to a specific field of study or a particular subject matter, while philosophers want to understand the whole. Sellars thinks that this philosophical skill is most clearly demonstrated when we try to understand the connection between the natural world as we experience it directly (the “manifest image”) and the natural world as science explains it (the “scientific image”). He suggests that we gain an understanding of the nature of philosophy by trying to reconcile these two pictures of the world that most people understand independently.

Read Like a Philosopher

“philosophy and the scientific image of man”.

This essay, “ Philosophy and the Scientific Image of Man ” by Wilfrid Sellars, has been republished several times and can be found online. Read through the essay with particular focus on the first section. Consider the following study questions:

- What is the difference between knowing how and knowing that? Are these concepts always distinct? What does it mean for philosophical knowledge to be a kind of know-how?

- What do you think Sellars means when he says that philosophers “have turned other special subject-matters to non-philosophers over the past 2500 years”?

- Sellars describes philosophy as “bringing a picture into focus,” but he is also careful to recognize challenges with this metaphor as it relates to the body of human knowledge. What are those challenges? Why is it difficult to imagine all of human knowledge as a picture or image?

- What is the scientific image of man in the world? What is the manifest image of man in the world? How are they different? And why are these two images the primary images that need to be brought into focus so that philosophy may have an eye on the whole?

Unlike other subjects that have clearly defined subject matter boundaries and relatively clear methods of exploration and analysis, philosophy intentionally lacks clear boundaries or methods. For instance, your biology textbook will tell you that biology is the “science of life.” The boundaries of biology are fairly clear: it is an experimental science that studies living things and the associated material necessary for life. Similarly, biology has relatively well-defined methods. Biologists, like other experimental scientists, broadly follow something called the “scientific method.” This is a bit of a misnomer, unfortunately, because there is no single method that all the experimental sciences follow. Nevertheless, biologists have a range of methods and practices, including observation, experimentation, and theory comparison and analysis, that are fairly well established and well known among practitioners. Philosophy doesn’t have such easy prescriptions—and for good reason. Philosophers are interested in gaining the broadest possible understanding of things, whether that be nature, what is possible, morals, aesthetics, political organizations, or any other field or concept.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Nathan Smith

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Philosophy

- Publication date: Jun 15, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/1-1-what-is-philosophy

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

The Quest for the Good Life: Ancient Philosophers on Happiness

Øyvind Rabbås, Eyjólfur K. Emilsson, Hallvard Fossheim, and Miira Tuominen (eds.), The Quest for the Good Life: Ancient Philosophers on Happiness , Oxford University Press, 2015, 307pp., $74.00 (hbk), ISBN 9780198746980.

Reviewed by Riin Sirkel, University of Vermont

This volume, containing fourteen papers, focuses on happiness in ancient Greek philosophy. There has been growing interest in happiness and its history within various disciplines like psychology, social sciences, literary studies, as well as in popular culture. Indeed, this shift of interest has been characterized as a "eudaimonic turn", where "eudaimonic" comes from the Greek eudaimonia , standardly translated as "happiness". [1] Thus, the focus of this volume is very much in line with our contemporary interests, but above all it contributes to the scholarship on ancient Greek ethics.

There is an abundance of volumes on ancient ethics, but this one stands out in two ways. Firstly, it is not mainly about Aristotle, who is the canonical figure in ancient ethics, but also includes papers on Plato, Hellenistic schools, the Greek commentators, and Augustine. The inclusion of philosophers of late antiquity deserves special mention, for even though their philosophy represents a crucial link between ancient and medieval philosophy, their ethics has not yet been sufficiently explored. Secondly, this volume takes "the notion of happiness as its primary focus" (5), where the intended contrast is presumably with volumes that focus primarily on virtue or excellence. [2] It is true that of the two central notions of ancient ethics -- eudaimonia or happiness and aretê or virtue -- the scholarly discussions have tended towards virtue, which is encouraged also by the development of virtue ethics. The focus on virtue and virtue ethics has privileged some themes and topics over others, which might help to explain why some themes discussed in this volume (e.g. happiness and time, or happiness as godlikeness) have not received much scholarly attention, although they figure frequently in ancient discussions. The greatest strength of this volume is that by shifting the focus from virtue to happiness it brings to light new issues, topics, and approaches, and shows that ancient ethics is richer, more complex and less homogeneous than is often assumed.

What makes it an interesting volume also makes it difficult to review. To display the diversity of themes and authors, I have included short summaries of all papers, which I have arranged thematically. One of the dominant themes (if not the most dominant theme) of the volume is the relation between happiness and time. I will discuss papers on this theme in slightly greater detail, and then make some evaluative remarks about the volume as a whole. Also, it is worth noting that the volume derives from the project Ethics in Antiquity: The Quest for the Good Life at the Centre for Advanced Study in Oslo, and testifies to the lively interest in eudaemonist ethics in Nordic countries.

For ancient philosophers, eudaimonia is not a particular kind of experience or feeling, but a particular kind of life, where reason almost always plays an important role. The link between happiness and reason is clearly drawn by Aristotle in Nicomachean Ethics ( NE ) I 7, where he argues that happiness resides in rational activity in accordance with virtue. This argument is discussed by Øyvind Rabbås in " Eudaimonia , Human Nature, and Normativity: Reflections on Aristotle's Project in Nicomachean Ethics Book I". He aims to explain how Aristotle's ethics can be both naturalist and practically normative, i.e. based in a conception of human nature as a rational being, and at the same time give guidance on how we ought to live. The connection between happiness and reason is particularly tight in the Platonist tradition, with Plotinus identifying the happy life with the life of intellect. Plotinus' thoughts on happiness are discussed by Alexandrine Schniewind (and touched upon by Eyjólfur K. Emilsson and Miira Tuominen). Schniewind shows in "Plotinus' Way of Defining ' Eudaimonia ' in Ennead I 4 [46] 1-3" that Plotinus' puzzling remarks about his predecessors in the two opening chapters of Ennead I 4 are intended to clear the way for his own definition of happiness.

As well as a connection between happiness and reason, the volume demonstrates that there is a close connection between happiness and godlikeness in ancient ethics. This theme is mentioned in several papers, and taken up in detail by Svavar Hrafn Svavarsson in "On Happiness and Godlikeness before Socrates". Starting from the observation that Plato and Aristotle share the idea that happiness "consists in being as like god as possible" (28), he traces the development of this idea from Homer and Hesiod, through lyric poets, to Heraclitus. He shows how the focus shifts from happiness as external success, entirely dependent on gods, to internal factors responsible for this success. Another significant shift takes place in late antiquity, and is addressed by Christian Tornau in "Happiness in this Life? Augustine on the Principle that Virtue is Self-sufficient for Happiness". Augustine denies the possibility of achieving happiness in this life and regards happiness as a gift of divine grace, but nonetheless holds on to the traditional idea that virtue is sufficient for happiness. Tornau examines his attempt to resolve this dilemma through redefining virtue.

While this volume focuses primarily on happiness, rather than on virtue, the connection between happiness and virtue is an important theme in ancient ethics. Most ancient Greek philosophers agree that in order for one to be happy, one needs to be virtuous, though opinions differ as to whether being virtuous is sufficient for happiness. The Stoics famously take virtue, understood as wisdom, to be sufficient for the happy life, and a common complaint against their account is that the status of the wise person is outside the reach of regular people. Katerina Ierodiakonou's "How Feasible is the Stoic Conception of Eudaimonia ?" considers and responds to objections presented by the Stoics' ancient critics. She argues that Stoic moral principles do not rule out moral progress, and their conception of eudaimonia , as an aspiration towards an ideal, is no less feasible than that of other ancient ethical theories. Ierodiakonou's paper is perhaps most directly about virtues, whereas other papers discuss virtues more or less indirectly.

Justice as one of the cardinal virtues is discussed in two papers on Plato's dialogues. In "Wanting to Do What Is Just in the Gorgias ", Panos Dimas walks the reader through the Gorgias, and shows that Socrates fails to offer a substantive defense of the view that people want to do what is just, when they know it. Socrates' failure, he proposes, is due to a lack of a positive theory of justice, and the Gorgias may thus be seen as paving the way for the discussion in the Republic . In "Plato's Defence of Justice: The Wrong Kind of Reason?" Julia Annas focuses on Socrates' answer in the Republic to the question of why one should be just. His answer is that being just will lead to living a happy life. Prichard famously complained that this is a wrong kind of answer, since ordinarily people suppose that the reason for being just should not appeal to one's happiness, but to its being the right thing to do. Annas focuses on a recent version of this objection, according to which there are indications in Plato himself that, when defending justice in a eudaemonist way, he is ignoring an alternative answer available to his audience. She offers a close reading of relevant passages, showing that these do not support the "wrong kind of answer" objection. Gösta Grönroos' focus in "Why Is Aristotle's Vicious Person Miserable?" is not on virtue and happy life, but rather on vice and miserable life. He aims to explain why the bad person is miserable, proposes that one reason is her mental conflict, and gives an account of what this conflict amounts to.

Although most ancient philosophers take virtue to be a constituent of happiness, there are also some exceptions. Epicureans take happiness to consist in pleasure, and Dimas' aim in "Epicurus on Pleasure, Desire, and Friendship" is to clarify what being a hedonist amounts to for Epicurus. He argues that Epicurus is a psychological and ethical hedonist, examines his divisions of pleasure and desire, and explains how Epicurus' hedonism fits with his views on virtue and friendship. Also the Pyrrhonian sceptics did not connect happiness with virtue but with the sceptical suspension of belief. The relation between the suspension of belief and happiness as tranquillity is discussed by Svavarsson in "The Pyrrhonian Idea of a Good Life". He discusses four kinds of texts and testimonies on Pyrrhonian tranquillity, with special emphasis on Sextus Empiricus and his perplexing attempt to establish that "the sceptic aims at tranquility but attains it by chance" (197).

Finally, a recurring themee is happiness and time, which deserves special mention. While this theme has received almost no attention from scholars, the papers in this volume demonstrate that it occupies an important role in ancient discussions. In "Aristotle on Happiness and Long Life", Gabriel Richardson Lear gives an interpretation of Aristotle's claim in NE I 7 that happiness requires a complete (or perfect, teleion ) life. The same claim is discussed by Emilsson in "On Happiness and Time", where he contrasts the views of Aristotle with post-Aristotelian authors, who give up the complete life requirement. Tuominen considers, in "Why Do We Need Other People to be Happy? Happiness and Concern for Others in Aspasius and Porphyry", the relation between self-interest and concern for others by examining Aspasius' and Porphyry's views. She shows how Aspasius, in commenting on Aristotle's claim in NE I 7, makes the concern for others central for happiness: happiness requires a complete life because one needs to do as much good as possible, also to others. Under this theme may also be subsumed Hallvard Fossheim's "Aristotle on Happiness and Old Age", which discusses (following Aristotle) the impact of old age on virtue and happiness.

At this point I would like to pause, for a moment, to consider proposed interpretations of Aristotle's claim that happiness resides in rational activity "in a complete life", for "one day does not make someone blessed and happy, and neither does a short time" (1098a16-20). On Lear's interpretation, the virtuous activity that constitutes happiness must be something habitual, stable and self-knowing. It takes time for the virtuous activity to become a stable and self-knowing way of life, a person needs "a relatively long time of acting well in order for it to be evident -- to herself and also to her fellow citizens -- that virtuous is what she is " (143). Lear's interpretation implies that the person, who has acquired virtue and acts accordingly, but does it only for a short time (e.g. because she dies young) is not happy (cf. 141). However, this seems counterintuitive, and one is inclined to make the same sort of observation that Lear herself makes earlier in the paper: "Aristotle thinks of the brave person as willing to give up a life that is, in a sense, already happy -- it is precisely for this reason that the prospect of death is painful for him" (137). Yet, her own proposal suggests that the brave person who dies on the battlefield, having obtained the virtue of bravery only recently, would not be considered happy. Emilsson seems to hold (unlike Lear) that we can judge the person who has obtained virtue and acts accordingly to be happy, but we should in our judgement leave open the possibility that things may change in the future. So, we will not judge the person to be happy unconditionally, but "ascribe happiness to a living person who is doing well on the condition that he will stay so till the end and nothing disastrous happens to him" (240). It is not clear how to cash out the details of this proposal, but Emilsson's paper is certainly thought provoking, and together with Lear's, provides a good starting point for further discussions. The same can be said for various other pieces in the volume.

So let me now make some evaluative remarks about the volume as a whole. As the above summaries show, the volume is deep and includes a wide variety of ancient authors. The variety is certainly a strength, but it invokes some questions about the selection of topics. I was left with the lingering question about the role and contribution of Socrates to the ancient eudaemonist tradition, i.e. the tradition that takes eudaimonia as the highest good and ultimate aim of all human endeavor. The volume includes a paper on the Gorgias , and a remark in the introduction that Plato's thought is "a peculiar case in our story" (24). This is because Plato never offers as extensive and systematic treatment of eudaimonia as Aristotle, and yet this topic is "clearly central to his thought" (24), which is then backed up with references to Plato's dialogues, including Socratic dialogues. However, it does not become clear what is the distinctive role of Socrates is this "story", and whether the editors would agree with those authors who take Socrates to be the founder of the eudaemonist tradition. [3] If they would, then wouldn't Socrates deserve more than a passing glance?

Also, the shift of focus from virtue to happiness has advantages that were outlined in the introduction, but placing the primary focus on happiness involves also some potential worries. For instance, even though this volume is about happiness, there's actually not too much discussion about what happiness amounts to, or how to achieve it. The answers to these questions are often just assumed, and the authors move on to discussing some other aspect of the eudaemonist framework. This might be the result of this shift of focus. For most Greek philosophers, the question "What is happiness?" will lead to the discussion of virtue, so it would be difficult to focus on this question without focusing on virtue. Yet, this is what the volume wants to avoid doing. Also, when the editors speak about the goal of the volume, they say that "the first and immediate motivation is to give the reader a sense of how ancient thinkers approached the topic [of happiness and the good life]" (5). Given the importance of virtue in the ancient approach, one wonders whether the volume achieves this aim without placing substantial focus on virtue. Just as the one-sided focus on virtue may hide away some interesting aspects of ancient ethics, there is a corresponding worry that the focus on happiness may paint a one-sided, if not misleading, picture of ancient ethics.

Further, the ancient philosophers' answer to the question "What is happiness?" may be controversial. This is particularly so in the case of Aristotle, who distinguishes between moral virtues and intellectual virtues. His account of happiness in the first books of NE suggests that he ascribes the central role to the former, holding that happiness resides in the morally virtuous action guided by reason, whereas his account in the last book of NE identifies the virtuous activity that constitutes happiness with theoretical contemplation, and it is far from clear how these accounts are supposed to fit together. This difficulty is discussed briefly by Lear, and mentioned by Fossheim, while others rely on one account or other, without making their view explicit. So Grönroos assumes that the virtuous and happy person is morally virtuous, whereas Svavarsson, in claiming that for Aristotle happiness consists in godlikeness, evidently associates happiness with theoretical contemplation. While the expert can orient herself within different interpretations and assumptions, this will be challenging for those not familiar with the issues involved.

Consequently, one might have some worries about accessibility, especially as this volume is intended not only for experts but for non-experts as well. It is true that reading some individual papers may be challenging without background in ancient philosophy, but I would encourage the reader to keep on reading, since the papers nicely contribute to one another, and collectively give the reader a good sense of ancient discussions of happiness. I agree that "there is a lot to be learnt today concerning the nature and content of happiness from proper understanding of the ancient debates" (5). Familiarizing ourselves with these debates makes us better aware of our prejudices concerning happiness, compels us to revise some of our presuppositions (e.g. about the subjectivist nature of happiness), and generally improves our thinking about happiness. So, all in all, I would not go as far as to say that reading this volume will make you happy, but it certainly is a rewarding experience.

[1] See The Eudaimonic Turn: Well-Being in Literary Studies , edited by James O. Pawelski and D. J. Moores, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2014. For a comprehensive account of current happiness research, see Oxford Handbook of Happiness , edited by Susan A. David, Ilona Boniwell, Amanda Conley Ayers, Oxford University Press, 2013.

[2] The editors see Julia Annas' Morality of Happiness (Oxford University Press, 1993) as most closely connected to their project, but add that "even here the focus seems to be more on virtue and morality than on happiness as such" (5).

[3] See, e.g., Terence Irwin, The Development of Ethics : A Historical and Critical Study ; Volume 1: From Socrates to the Reformation , Oxford University Press, 2007, esp. pp. 22-23.

Greek Mythology, Religion, Philosophy, and History Essay

In the history of the World, no other society has had such a rich mix of religion, mythology, philosophy, and history as the ancient Greeks. Some experts claim that the genesis of this intermingling lay in the overtly polytheistic nature of ancient Greek religion which worshipped a pantheon of gods. The Mediterranean region with its diverse seafaring traditions was a birthplace for the intermingling of cultures. Polytheism led to the Greeks adopting a remarkable tolerant attitude towards the viewpoints and beliefs of others.

Over a period of time, such broad attitudes became fertile ground for the exercise of human imagination leading to the birth of great epics steeped in legend, mixed with actual historical facts, and the dawn of modern philosophical thought. The operative utility of this tradition of philosophy gave rise to the Greek city-states, the first form of a democratic society. According to Knierim, “The ancient Greeks viewed the world in a way that one would today perhaps describe as ‘holistic’. Science, philosophy and politics were interwoven and combined into one worldview” (1). This essay attempts to describe the ancient Greek period from 2700 B.C to the 4th century B.C with a view to explain the interrelation between Greek religion, mythology, philosophy, and history.

Greek religion can be classified into four main periods. During the period 2700-1100 B.C, the religion of the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures was practiced in the region of Crete and the Aegean Basin. This religion was predominantly based on female deities. Other figures of animals with human heads suggested that some form of animism was also prevalent. The ancient religious stories of the Minoans and the Mycenaean were transmitted orally to the other parts of the Mediterranean region which later fused with the Greek traditions and religious practices.

As the Greek societies evolved, so did their religion, and the next period 1100-750 B.C is referred to as the ‘Heroic Age’ made famous by Homer and Hesiod. It was during this period that the pantheon of Greek gods attained their fame and acceptance by the Greeks. The third period witnessed a move away from polytheism to the era of rational thinking and skepticism also known as the ‘Golden Age of Athens, spanning from the 6 th century to 4 th century B.C. The final period, Greco-Roman ranged from 2 nd century B.C to 2 nd century A.D which basically led to the export of Greek philosophical thought the world over.

The effect of Greek mythology on religion and history is so entwined that often it becomes difficult to distinguish the two. The Greek pantheon of Gods presided over by Zeus, made famous by Hesiod and Homer became the focal point of Greek religion. Not only were mythological stories attributed to the Olympiad Gods, but they also became the basis for regulating Greek society too. Lloyd-Jones ( 2006) states that “ The early poet Hesiod explains that “Zeus gave to kings the them es, the principles of justice by which they ruled”(460). The mythologies encouraged the practice of sacrifice to the various gods to achieve defined ends. “Greek armies always made a divinatory sacrifice before going into battle, and the general took the omens after a sacrifice before deciding to go into action”. (Lloyd-Jones,2006, p.461).

The establishment of the Oracle of Delphi in honor of the Greek God Apollo took a political hue when every ruler far and wide consulted the Oracle to determine the course of action for conquest, administration of the state, and a host of other decisions. So popular was its usage that not only did the Greeks use the Oracle, but also other non-Greek kingdoms.

In Greek society, myth and history too were inexorably intertwined. A typical example is exemplified by the Trojan War, which according to many historians and archaeologists, was a real historical event. But the myth surrounding the idea of building the Trojan horse is attributed to the divine intervention of the Greek Goddess Pallas-Athene (Minerva). According to Berens, “She also taught the Greeks how to build the wooden horse by means of which the destruction of Troy was effected”(43).

Homer’s epics Iliad and Odyssey served as a rallying point for the Greek society. The Gods and Goddesses as described by Homer were revered by the Greeks and “these works came to serve as both epic and bible, providing a vivid ideal of manly prowess set in a framework of religious belief” (Time-Life Book, 1988, 53). The Olympic Games founded in 776 BC were dedicated to the God Zeus. The Battle of Marathon in 490 B.C between the Greeks and the Persians was a true historical event.

However, the so-called feat of a messenger running the entire 42 km from the war front to Athens is a legend that has no historical proof but nevertheless is entwined in popular culture leading to the institution of the famous marathon runner in the Olympic Games.

The Greek Philosophers had an undeniably relevant role in the development of Greek History. Solon who was elected as the archon of Athens in 594 B.C laid the framework of a democratic society. Socrates propounded the ‘test of reason’ as a philosophy of rationalism. “Instead of building on the myopic ideas of mythology, he began a rational inquiry into the riddles that nature presents. This inquiry is based on reflection and reason alone, and it may be his greatest achievement” (Knierim, 4).

Reasoning, rationalism, and critical thinking were the natural evolution of a polytheistic creed steeped in intolerance and intellectual inquiry into the nature of things. This tradition of reasoning finally led to the denouncement of the numerous Greek Gods by the Greek philosophers. By the end of the fifth century B.C, Greek philosophy became more scientific in its outlook. “ Plato denounced the immorality of the gods as portrayed by Homer and the other poets”( Lloyd-Jones, 2006 p.463).

Aristotle moderated the harsh critique of Gods propounded by Plato and his brand of ethics was more accommodative to traditional Greek religion. It, therefore, comes as no surprise that Aristotelian logic still finds popular support in these modern times. Despite the onslaught of rationalism and reasoning, traditional Greek gods continued to be worshipped and were supplemented in the Greco-Roman period by Roman Gods. The cults survived for eight centuries after Plato till the 4 th century A.D when the Christian emperor Theodosius banned and persecuted the followers of polytheism leading to their decline.

In conclusion, it can be said that the unique blend of mythology, religion, philosophy, and history in the Greek traditions survived for over a thousand years because of the syncretistic nature of the Greek thought, based on polytheistic processes which yielded an unusual degree of tolerance not to be seen in the later monotheistic creed of Christianity and Islam.

Some historians claim that this ability to assimilate differing thought came not only because of the genius of the Greek people but also because of the influence of Eastern thought which came by through the extensive trade links that Greece had with the East. The rich blend of myth, religion, philosophy and its effect on the history of the western world gave the grounding for the development of modern western philosophical thought of rationalism and reasoning. It also laid foundations for a political system that was soon to dominate the modern world – Democracy.

Works Cited

Berens, E.M. “Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome”. Project Gutenberg. 2007. Web.

Gillian, Moore and Editors of Time-Life Books. 1988. “ A Soaring Spirit”. A volume of Time-Life Series History of the World. Time-Life Books inc. Time Warner Inc. USA.

Knierim, Thomas. “Pre-Socratic Greek Philosophy”. 2008. Web.

Llyod-Jones, Hugh. 2001. “Ancient Greek Religion”. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society vol. 145, no. 4. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, September 29). Greek Mythology, Religion, Philosophy, and History. https://ivypanda.com/essays/greek-mythology-religion-philosophy-and-history/

"Greek Mythology, Religion, Philosophy, and History." IvyPanda , 29 Sept. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/greek-mythology-religion-philosophy-and-history/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Greek Mythology, Religion, Philosophy, and History'. 29 September.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Greek Mythology, Religion, Philosophy, and History." September 29, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/greek-mythology-religion-philosophy-and-history/.

1. IvyPanda . "Greek Mythology, Religion, Philosophy, and History." September 29, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/greek-mythology-religion-philosophy-and-history/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Greek Mythology, Religion, Philosophy, and History." September 29, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/greek-mythology-religion-philosophy-and-history/.

- Polytheism, Monotheism, and Humanism

- Polytheism of Ancient Greek and Babylonians Compared

- Hesiod's Views on Art and Poetry

- Zeus’s Literary Journey Through Mythology

- Important Virtues in Human Life: Plato’s Protagoras and Hesiod’s Works and Days

- Zeus’ Mythology

- Pantheon and Parthenon Historical Monuments

- The Architectural Significance of Pantheon Dome

- The Pantheon of Rome and the Parthenon of Athens

- The Parthenon and the Pantheon in Their Cultural Context

- Mayan Architecture, Its Meaning and Creators

- Sumer and Akkadian Cities, Towns and Villages, 3,500 - 2,000 BC

- Western Civilizations: Mesopotamia, Egypt, Rome,Greece

- The Culture of Ancient Egypt

- Ubaid and Uruk: Emergence of Mesopotamian Cities

- Project Gutenberg

- 73,406 free eBooks

- 43 by Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche

Early Greek Philosophy & Other Essays by Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche

Read now or download (free!)

Similar books, about this ebook.

- Privacy policy

- About Project Gutenberg

- Terms of Use

- Contact Information

The Impact of Ancient Greek Philosophy on Modern Day Thought

How did Greek philosophy influence today’s culture? Why is Ancient Greek philosophy important for modern literature? Here, you’ll find answers to these and other questions. Keep reading to get some ideas and inspiration for your essay!

Introduction

Contribution of ancient greek philosophy on modern thought, ancient greek philosophy impact on education, ancient greek philosophy impact on religion, ancient greek philosophy influence on politics, works cited.

Ancient Greek philosophy has arguably played the greatest role in shaping modern thought, particularly Western culture. It emerged in the 6th century BC and was largely explored in Ancient Greece and the rest of the Roman Empire. It tackled several areas, including ethics, politics, rhetoric, mathematics, metaphysics, logic, astronomy, and biology. Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle are the most influential classical philosophers with the most significant impact on modern thought.

Their contributions to advancing art, politics, and science were immense. They pioneered the art of exploring nature rationally and developing theories explaining the universe’s existence. Greek philosophers combined ideas from science, philosophy, art, and politics to form a holistic worldview that moved them away from the then-popular mythological perspective. The application of logic, reason, and inquiry is why ancient Greek philosophy (pre-Socratic, Classical Greek, and Hellenistic philosophy) has shaped modern thought, both in the East and West.

There is undeniable evidence that parallels exist between ancient Greek philosophy and modern thought in several fields. However, the Greeks adopted a holistic view of the world, which was developed through the combination of various disciplines, including science, religion, philosophy, and art (Adamson 34). This worldview is different today, even though ancient philosophers continue to influence modern thought in immense ways.

For example, deductive science originated from Thales’ propositions about right angles (Adamson 54). The philosopher argued that the inscription of a triangle in a semicircle formed a right angle. This concept might seem simple and overrated. However, it is used in contemporary society by mathematicians in the field of geometry (Rooney 36). Moreover, deductive reasoning is widely applied as a tool for generating propositions. The idea that all forms of a substance can be broken down into constituent elements was more deeply explored during the Thales era than in any other period.

The influence of Aristotle’s work can be seen in various areas of modern thought. The thinker formulated the concept of true knowledge acquisition. In that regard, he taught that it is only when a thoughtful soul disregards world events that it acquires true understanding (Adamson 65). He argued that the information received through the senses is usually polluted and confusing to people. He believed that any form of education aims to attain a specific human ideal. Aristotle argued that education is the best way for human beings to achieve their fundamental concerns and develop themselves wholly (Heinaman 52).