Economics PhD Acceptance Rates 2024: Do You Stand a Chance?

Are you considering applying to Economics PhD programs in 2024? If so, you must be aware of the fierce competition and ever-decreasing acceptance rates in this field. Economics continues to be a popular choice for individuals seeking advanced study and a promising career path. However, as the number of applicants continues to rise, the acceptance rates at top-tier universities seem to plummet. Gaining admission requires a comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence your chances. It is crucial to make well-informed decisions throughout the application process to maximize your opportunities. In this blog post, we will delve into the world of economics PhD acceptance rates, providing you with valuable insights and guidance to help you determine if you stand a chance in this highly competitive landscape. Whether you are a recent graduate, a working professional looking to advance your career, or an aspiring economist searching for answers, stay tuned as we explore the trends, challenges, and strategies that may shape your journey toward a successful application.

Pursuing Excellence in Economics PhD Programs

Economics PhD programs are renowned for their competitive nature, attracting a broad pool of highly qualified candidates from around the globe. These programs are rigorous and demanding and seek to cultivate a deep understanding of complex economic phenomena and equip students with the tools necessary to conduct original research. Applicants often face intense competition with the number of available spots being significantly smaller than the pool of individuals seeking admission.

Unveiling the Competitiveness and Globalization of Economics PhD Programs

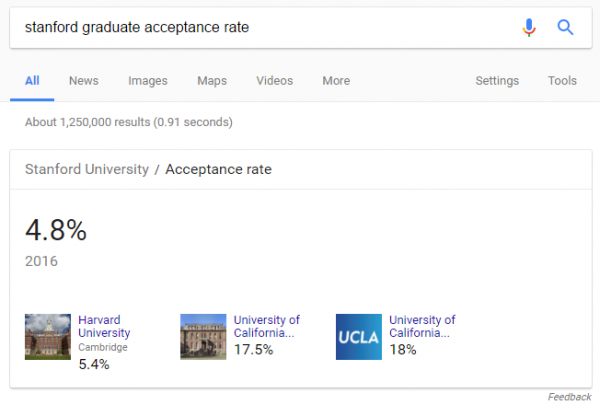

Economics PhD acceptance rates vary widely across institutions, but overall, they tend to be quite competitive. According to the National Science Foundation , the acceptance rate for doctoral programs in economics at top universities in the United States hovers around 10-15%.

Current trends in admissions reflect an increasing emphasis on quantitative skills and research experience . Applicants who have completed advanced coursework in mathematics or statistics, or who have substantive research experience, particularly if it has led to a publication, often have a competitive edge. There is also an increasing trend of students entering these programs with a master’s degree already in hand.

Another key trend is the growing internationalization of these programs. Universities are drawing applicants from across the globe, leading to an increasingly diverse cohort of doctoral students in economics. This trend not only reflects the global nature of economic challenges but also enriches the academic discourse within these programs.

Evaluating Your Suitability

When assessing your suitability for an economics PhD program, universities take into account numerous factors, among which your Graduate Record Examinations (GRE) scores and Grade Point Average (GPA) play a significant role. These quantitative measures offer admissions committees a snapshot of your academic abilities and potential for success in a rigorous program.

As a rule of thumb, competitive programs often expect a minimum GPA of 3.5 and high percentile GRE scores, particularly in the quantitative section. For instance, the Graduate School at Harvard University confirms that successful applicants to their economics PhD program typically score above the 95th percentile in the quantitative section of the GRE.

The PhD in economics at Berkeley states that recent admits have a major GPA of 3.8 or higher. Their quantitative GRE score is 165 or higher. Moreover, the school notes that students typically achieve A- grades or higher in intermediate-level theory courses such as microeconomics, macroeconomics, and econometrics. Preference is given to those who have taken honors or mathematical track versions of these courses.

At Duke , students who matriculated in 2023 had a verbal GRE verbal score of 159, a quant score of 166, and a GPA of 3.6. Penn writes that admits have a GRE quant score that is 164 or higher.

Based on the data for the Department of Economics at Brown University, the acceptance rate for the class starting in 2020 was approximately 8%. This percentage was drawn from a pool of roughly 750 applications, out of which about 60 were admitted. However, this rate varied according to different GRE scores. Particularly, applicants with a GRE score below 165 had a significantly lower acceptance rate of about 4%.

Although Yale ‘s Department of Economics website explicitly states that there is no required minimum for GRE scores, it does provide insight into the average scores of admitted students in recent years: Verbal 159, Quantitative 165, and Analytical 4.2.

Despite these numbers, it is also important to note that these are not hard and fast rules. The American Economic Association emphasizes that strong letters of recommendation and relevant research experience can offset weaker areas in an application.

If your numbers fall below the threshold of economics PhD acceptance rates, some areas to potentially improve could be to retake the GRE after thorough preparation, undertake additional coursework to boost your GPA or gain relevant research experience to strengthen your overall application

The Real Impact of a Master’s Degree on Admission Chances

When applying for PhD programs in Economics, many applicants believe that holding a master’s degree can have a significant impact on their admission chances. This belief stems from the notion that a master’s degree provides a valuable platform for producing high-quality research, which is highly regarded by admissions committees. Demonstrating the ability to contribute to the field is a primary expectation of PhD programs, and a master’s degree can serve as evidence of this capability.

Moreover, a master’s degree can also be seen as offering opportunities for obtaining strong recommendation letters from professors who can attest to the applicant’s readiness for rigorous doctoral study and therefore enhance the admission chances of master’s degree holders applying to economics PhD programs.

While this can be true, the reality is not as straightforward. According to data from the Council of Graduate Schools, there is not a direct correlation between holding a master’s degree and an increased likelihood of PhD acceptance. While a master’s degree can provide students with a deeper understanding of the field and advanced research skills, these benefits do not necessarily guarantee an edge in the highly competitive PhD application process.

Universities carefully assess each application in a comprehensive manner, taking into account various factors including academic accomplishments, research background, letters of recommendation , and personal statements. This suggests that by 2024, possessing solely a master’s degree may not significantly enhance the likelihood of being admitted to a PhD program .

Ultimately, prospective PhD applicants in 2024 should focus on building a robust profile encompassing strong academic records, relevant research experience, and compelling personal narratives, rather than relying solely on a master’s degree for admission.

Decoding Economics PhD Acceptance Rates: Unveiling Trends across Institutions and Years

Acceptance rates vary from year to year, reflecting changes in the academic landscape and student preferences. Some of the most competitive universities, such as Harvard and MIT, demonstrate consistently low acceptance rates due to the large number of high-caliber applicants they attract annually.

For example, Harvard’s economics PhD program has historically accepted around 5% of its applicants, a figure that’s remained relatively stable over the past decade. On the other hand, smaller or less renowned institutions might exhibit higher acceptance rates. For instance, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln has an acceptance rate of about 40%, driven by its smaller applicant pool.

However, while these figures indicate the competitiveness of these programs, they don’t necessarily reflect the overall quality of education or the potential outcomes for graduates. Therefore, when contemplating the pursuit of a PhD program in economics, it is imperative to go beyond mere acceptance rates and take into account other significant factors that bear influence.

Enhancing Your PhD Application: The Importance of Quality Research Experience and Strong Recommendations

Gaining a depth of research experience and strong letters of recommendation are crucial aspects that can significantly enhance your PhD application, making you stand out in the increasingly competitive landscape of 2024.

For research experience, consider engaging in projects that align with your intended field of study. This could be undergraduate research, independent studies, or working as a research assistant. Being credited on a published paper can provide a significant boost, but it’s not solely about the volume of research conducted. The depth and quality of your work are equally important. Your research should also demonstrate your ability to think critically about research problems, develop hypotheses, design experiments, and draw compelling conclusions.

When it comes to recommendations, choose professors or supervisors who know you well and can speak to your skills and potential as a researcher. A glowing letter from a professor who has worked closely with you can carry more weight than a lukewarm letter from a big name.

Ways to strengthen your application and stand out from other applicants

To bolster your application and distinguish yourself from other candidates in the economics PhD acceptance rates, consider emphasizing your unique skill sets and experiences. For instance, showcasing proficiency in technical skills such as statistical analysis software (like STATA, R, or Python) or mathematical modeling can demonstrate your readiness to engage in high-level economic research.

If you have a specific area of interest, such as labor economics or development economics, aligning your research experience, coursework, or future research goals with this specialization can also make your application more compelling.

Furthermore, articulating a clear, thoughtful, and original research proposal in your statement of purpose can significantly enhance your application. This proposal, ideally aligned with the research interests of faculty members at the institution you’re applying to, indicates your potential to contribute significantly to the field.

Lastly, consider undertaking professional experiences that align with your academic pursuits. For example, internships at economic research firms, governmental agencies, or industry positions that require a strong foundation in economics can demonstrate your ability to apply theoretical knowledge in a practical context.

Remember, a PhD in economics is not just an academic endeavor, but a platform for impacting economic thought and policy, so any evidence of your ability to contribute in this way can strengthen your application.

Deciphering Myths: Understanding and Navigating the Landscape of Economics PhD Acceptance Rates

Often, the domain of Economics PhD admissions is shrouded in myths and misconceptions that can cloud the judgment of aspiring scholars. One such myth is the belief that a flawless academic record is the sole determinant of success. While a strong academic standing is undeniably important, admissions committees also place significant emphasis on research experience, recommendation letters, and a well-articulated statement of purpose that presents a clear vision of your research interests and goals.

Another pervasive myth is that applicants must hold a bachelor’s degree in economics to be considered for admission. The truth is that many programs welcome candidates with diverse undergraduate backgrounds, valuing the unique perspectives and skills they bring.

Similarly, it is a common misconception that applicants must have extensive mathematical training. Although a basic understanding of calculus, statistics, and linear algebra is required, most programs do not expect applicants to be math wizards.

Lastly, there is a mistaken notion that gaining admission to top-tier programs is impossible without prior connections or a pedigree. In reality, admissions decisions are based on a holistic review of an applicant’s profile, not their connections or pedigree. It’s important to dispel these myths and understand the true nature of the admissions process to successfully navigate your way to a fruitful academic journey in economics.

Embracing Opportunities: The Advantages of Enrolling in Less Prestigious Economics PhD Programs

While it is certainly understandable to aspire to attend top-tier universities for your PhD in economics, it is equally important to recognize the potential benefits that less prestigious programs can offer.

Firstly, a less renowned program may provide a more intimate and supportive learning environment, allowing for closer mentorship and more individualized attention from professors. This can greatly enhance your learning experience and research progression.

Secondly, these programs might present more opportunities for you to lead or initiate research projects, as competition might be less intense compared to top-tier institutions. Such experiences can be invaluable in building your academic portfolio.

Lastly, less prestigious programs often harbor unique strengths or niche specializations that may align better with your research interests. These programs could provide you with unique perspectives and experiences that can make your research more distinctive. Therefore, rather than considering admission into a less prestigious school as a setback, view it as an opportunity to carve your unique path in the field of economics.

Making the Wise Choice: Starting Early and Seeking Guidance for Successful PhD Economics Admissions

It is essential to remember that a successful application to PhD programs in economics is not a product of rushed decisions or last-minute efforts. Instead, it is the result of meticulous planning, punctual execution, and thoughtful decision-making carried out well ahead of time. Initiating your application process early will afford you ample time to undertake in-depth research about various programs, understand their requirements, and tailor your application to best demonstrate your suitability. This practice can significantly boost your chances of admission by allowing you to present a well-rounded and thoughtfully curated application that reflects a sincere interest in the program and a clear understanding of its demands.

Furthermore, reaching out to mentors, alumni, or current students for their insights can be incredibly beneficial. Their firsthand experiences and perspectives can offer invaluable advice, expose you to different viewpoints, and help you avoid potential pitfalls.

By taking your time, starting early, and seeking input from others, you can significantly enhance your probability of securing admission to your desired PhD economics program.

In conclusion, the future of economics PhD programs is a competitive and rapidly evolving landscape. With an increasing number of applicants and declining acceptance rates, it is crucial to equip yourself with the necessary knowledge and strategies to stand out among the sea of applicants. From understanding the trends in acceptance rates to making informed decisions throughout the application process, these key insights can make all the difference in your journey toward a successful admission. As you consider your options for applying to economics PhD programs in 2024, remember that preparation is key. Don’t let the thought of intense competition discourage you; instead, use it as motivation to put your best foot forward and take advantage of every opportunity. If you find yourself feeling overwhelmed or seeking professional guidance, be sure to check out our comprehensive PhD application services. We are here to support you on your path toward achieving your academic and career goals in the field of economics. So don’t waste any time, take charge of your future today! Have questions? Sign up for a consultation . It’s FREE!

With a Master’s from McGill University and a Ph.D. from New York University, Philippe Barr is a former professor and assistant director of MBA admissions at Kenan-Flagler Business School. With more than seven years of experience as a graduate school admissions consultant, Dr. Barr has stewarded the candidate journey across multiple MBA programs and helped hundreds of students get admitted to top-tier graduate programs all over the world .

Follow Dr. Barr on YouTub e for tips and tricks on navigating the MBA application process and life as an MBA student.

Share this:

Join the conversation.

- Pingback: Statement of Purpose for PhD: Tips from a Former Prof -

- Pingback: Your Chances of Getting Into Grad School in 2024 -

- Pingback: Getting Admitted into a PhD in Applied Economics -

- Pingback: PhD Rejection: Why You Did Not Get In -

- Pingback: PhD Admissions Secrets Revealed -

Leave a comment

Leave a reply cancel reply, discover more from.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Perhaps the best indication of the actual level of challenge is a mix between the quality and competitiveness indices (to some extent, there will be more places in more popular areas); the list in the next panel is based on the average of ranks on these two scores. Thus, getting into the best PhD programs appears to be an easier feat in economics than in computer science, physics, and math, but it’s tougher than just about everywhere else.

As readers with cross-disciplinary experience have pointed out, my method probably overestimates competitiveness in the hard sciences relative to economics. U.S. programs aren’t nearly so dominant in these areas: this circumstance, combined with more scattered pockets of specialized expertise, creates a larger pool of “respectable” institutions to which the global pool of applicants is matched. Let me also mention that fairly diverse fields, in content and selectivity, appear under the heading “business” in the first table. Out of these, finance gets much stronger applicants than others. On the whole, the considerably smaller size of business PhD programs, compared to economics, can make them very difficult targets, too.

Admission to good PhD programs in economics is very competitive – equally or more so than the scuffle for the most prestigious jobs out in “the real world.” Even some schools outside the top ten accept fewer than one in ten applicants, and this from a group of “overachievers” who have excellent grades and scores. They plan to enroll a smaller number than they admit – which means that only some of those 1 in 10 get fellowship offers … E.g. Rochester offered 7% a place in 2002, and fewer than 1% a place with full funding (fellowship and tuition waiver). If economics and math-intensive research are not your passions, the contest is not worth taking up. A suitable alternative may be business PhD programs, which are still a bit easier to get into (and through!), and provide more generous stipend packages, plus a less saturated job market with higher pay.

Official admission literature from the schools will always say that many factors are given consideration, and this is really true. In the end, the whole picture either looks like a fit with the particular department, or it doesn’t. On the other hand, certain weak spots are at once disqualifying. A popular program sees and expects very high undergraduate GPAs (still better graduate GPAs if applicable) at well-known institutions (ideally 3.7 / 4.0 or better, unless you come from a non-U.S. school or system that is understood to have tougher standards). It also expects a quantitative GRE score above 750 (800s are not out of the ordinary) and a decent analytical score. The verbal section is much less important, but a score below 500 looks off-putting, especially on an international application. Anything short of these benchmarks lands your application on the reject pile, unless you have some very intriguing other credentials (and usually inspite of it).

Pe digree matters - students from renowned U.S. undergraduate programs and state universities with top-ranked economics departments are popular with the adcoms (the more so, if applying to an Ivy). A concrete advantage these students have is access to well-known referees. But it is far from impossible to get into a good school without a gilt-edge degree, and the basic credentials (math background, grades ...) speak louder anyway. International admits are typically (though not without exception) chosen from the best institutions of their home countries. Professors know the major universities outside the U.S.; they understand that a Korean coming from Seoul National University is like an American coming from Berkeley. The department's past experience also plays a very important role in evaluating non-U.S. degrees. Some universities have a tradition of placing students in particular PhD programs every year because the adcoms have learnt by trial and error that they come well-prepared and succeed. In other cases, the adcom may be averse to admitting someone from the same school that "sent" a weak student last year. The same happens at the even cruder level of nationality. How does understanding this help you? Look up the current graduate students in a department, take note where they're from, and you'll get a sense of the adcom's little biases. Say you are from China and there seem to be very few Chinese students in the department: it's probably a tough place to get into.

You will need a number of math-related credits from your undergraduate studies. Graduate study in economics follows a theorem-proof approach and uses rigorous notation, so the adcoms pay a lot of attention to how comfortable you look to be with pure mathematics. Two or three terms of calculus, and often linear algebra, are deemed minimum preparation; similarly a semester of mathematical statistics. First-year graduate courses draw heavily on real analysis. Background in real analysis is highly valued and indeed almost expected of a strong applicant. Real analysis is usually the first "rigorous" mathematics course, where you have to work through all proofs and write some yourself. The course is supremely effective preparation for initial graduate courses. If you really want to delight the adcoms (you do), take metric spaces and functional analysis, too. When they see these and measure theory, perhaps even topology, they're rubbing their hands. Courses in differential equations are useful too, but if you have to choose in your final undergraduate years, the proof-based classes will always do more for you. Economics up to intermediate micro- and macroeconomics is also preferred, but perhaps not as essential. In all these, you should have earned good grades. Having taken too few math courses in college, or having performed poorly in them, rules you out of a top school. Apart from such coursework requirements, a formal major in economics is not necessary. In fact, the committee will view a math or physics major favorably, but anything – English, social work, Islamic studies – is fine as long as you demonstrate a strong aptitude for math.

Many successful international applicants have begun or completed a master's degree. Existing graduate transcripts are very helpful to the adcoms, since the content of the courses is similar everywhere, so this gives professors a good idea of what you really know and how you perform at a level of some rigor. (Research master's are also offered in some countries - they make little difference for admission.) It is generally assumed that master's level grades are inflated, so a graduate GPA ought to be rather better than 3.7. As long as you can show some solid grades in the program, it is acceptable to apply to a PhD program while still in the first year of a master's course and transfer out without finishing it. The master's degree itself will have little value (you'll get another from your PhD program). PhD programs will generally not give credit for such coursework; it serves only as a signal in the admission decision. You will start into your PhD program from year one. But if your math background is somewhat deficient, you may want to strengthen your application by completing the master's and taking the courses in the meantime. It's also easier to get recommendations if you've been around for more than a term. (And let's not forget that you do benefit academically: students who have worked through the graduate textbooks before, perhaps TAed at that level, have a clear advantage in the first year of their PhD programs and are likely to raise their stipends.)

Is it always good to get a master's before applying to PhD programs? It's becoming a reality for prospective applicants from unfancied undergraduate schools who are less than very well-prepared. If you don't have the right math credits, or your undergraduate GPA is mediocre, a master's course can solve your problems. It is much easier to get into the terminal master's program of any department than into the PhD program. Unfortunately, terminal master’s students in economics are generally not funded in the U.S., and tuition is not cheap. (Scholarships for master's students are available at some non-U.S. schools, e.g. at the National University of Singapore, but the trend is to move the money into PhD programs.) From a cost angle, and also with a view to ideal preparation for the PhD, a master's in math or statistics may be preferable to a master's in economics. (It makes a more favorable impression on adcoms besides.) Economics master’s programs are actually on the wane; they seem hard to justify, which is why top schools that don’t need the cash don’t offer them, but concentrate their resources on the PhD. (NYU and Boston University are the most prestigious U.S. schools that do offer the terminal master's.)

Letters of recommendation carry much weight. Contrary to popular belief, they do not need to come from famous professors. They must, however, come from academic economists (or perhaps mathematicians) – not your boss at work, nor your old philosophy instructor … If a non-economist can endorse you in a uniquely meaningful way, perhaps submit this recommendation as an extra. Of course, a distinguished referee can’t hurt, but getting an enthusiastic, specific letter from someone who knows you well is more important. Because lukewarm letters are very damaging, be sure to ask referees in advance whether they can support you whole-heartedly; a good way to breach the topic is to ask their advice on the type of program you should apply for. You can provide a background sheet with your grades, scores, and other credentials to recommending professors and refresh their memory about things you’ve done in class.

Phone calls from professors on your behalf will not necessarily help (and neither would personal e-mails to people on the committee, showing off your insightful opinions on their work); in fact, they can invite a negative reaction. More likely than not, people will find “helpful” outsiders disturbing and lecturing students presumptuous; professors often get contacted and won’t let it influence the decision. Of course, if your backer is or has been at the department you are targeting, that’s a different thing … Keep in mind how many students are applying and that professors cannot give individual attention at this stage. If anything, resentment at being busied with networking attempts may work against you. The situation is different at less established, more narrowly focused departments. Writing to professors makes good sense here, since you’d want to ascertain that they have resources in your area of interest and perhaps identify a potential supervisor. In some European systems it is even a necessary step in the application process - more on that later.

Much is made of the Statement of Purpose, but apparently it has a smaller impact in economics than in other subjects. Little that’s definite is known, but in my opinion, overly enthusiastic homages to economics or the department should be avoided as they sound artificial and waste space. Don’t forget that the professors who will read it are very intelligent people and won't appreciate your presuming otherwise. Nor do they care much about your sincere love for economics, your presidency of the toastmaster’s club, or the good things you’ve done in your community, as long as you can read and construct proofs. They also know you’re applying to other top schools and would gleefully go to any of them if you had the chance. The best approach is a conservative one, stating your credentials and objectives in a clear and focused way, outlining a specific research idea (without sounding rigidly attached to it – a delicate balance needs to be struck here), and mentioning how the school’s particular strengths fit into your plans. Look up the faculty’s research interests and histories to determine this.

Work experience (except at a central bank) is wholly irrelevant for graduate admissions. No degree of accomplishment or seniority in the private sector means anything to the professors. If you try to turn such a background to advantage in the statement, it will hurt you. You will sound as if you are delusioned about the nature and requirements of graduate study. Any major program would reject you. Most applicants have little or no work experience, but those who have had a career (and made an informed decision to apply for the PhD) should make only passing reference to the fact and instead implicitly address the questions that a prolonged absence from academia raises in people's minds. Primarily, they would wonder whether your math background is active knowledge, whether you can discipline yourself to study, whether your commitment is final and unencumbered by financial and family obligations.

A popular myth is that the admission committee rolls out the red carpet for applicants who have published a paper. I suspect that the opposite can be true. Top-school professors think nothing of low-quality journals; those publications are rarely up to the mark of good graduate research. Moreover, a poor-quality publication becomes part of your permanent record as a writer. Your advisors intend to work hard to make you an attractive candidate for the academic placement market and might prefer to start out on a blank page … Of course, if you have a paper in a good journal, your fortune is almost made. But good journals (check the list of journals included in the econphd.net rankings ) are virtually inaccessible to students, so I ignore the possibility. That said, there’s nothing wrong at all with sending a well-crafted technical paper as evidence that you can do serious research. If you submit anything, it ought to be a short and rigorous piece; qualitative (or even empirical) work is not likely to impress the committee.

So graduate programs require high GPAs - but what if you don't have a GPA? The main alternative to letter grades are numerical grades on varying scales. Australia, for instance, uses a percentage scale, i.e. the best possible grade is 100. In converting numerical grades, I would use the following key, which the University of Michigan endorses for Australian grades. (If the scale is, say, 15, just work it out proportionally.)

To calculate your GPA, you need to convert every grade to U.S. grade points and take the weighted average, where the weights are credit hours. A credit hour corresponds to the number of lecture hours per week in a twelve-week term. (Hence, add up the total number of lecture hours for the class and divide by 12.)

Grades aren't the only way in which adcoms can compare you. It helps if you have an official class rank or percentile. Some universities award "honors" on graduation that directly imply a percentile - if so, explain this. If you have no official class rank, ask your referees to quantify your standing in the class as they perceive it.

Lastly, if you feel that your converted grades or your official class rank still don't do you justice - say because your university, although not well known, is particularly competitive, it's ok to mention this in your application. Chances are, the adcom is already aware of it from previous experience (otherwise, they probably won't pay attention to your claim unless it's substantiated by the referees).

Economics departments give considerably lower fellowships than business schools or science departments. Worse yet, some people will be admitted without fellowships and a few end up paying tuition. But it is commonly understood (although the department may not be willing to explicitly guarantee it) that all students who stay on beyond the first one or two years are funded in some manner. Often teaching assistantships are part of it, but many programs also reward academic success with scholarship money.

Generally, the best and most competitive programs offer the most generous funding – MIT, Princeton, Harvard, Stanford, and Yale admits can expect to get a package of, perhaps, between $ 16,000 and $ 20,000 per year (with tuition waiver). Most other schools offer lower awards or awards tied to teaching duties, and the less prestigious the program, the less money tends to be available, and the more teaching is allocated. Some schools offer good first-year fellowships that will not be renewed subsequently (but can be replaced with a teaching or research assistantship).

The reason good programs don’t normally tie their aid to teaching is that the first-year coursework will be too intense to be compatible with chores. A teaching assistantship in the first year is a suspicious affair: either the coursework is not that hard, or they deliberately expose students to tremendous stress, compromised performance, and threat of failure in order to keep staffing costs down. If financially manageable, it would be advisable to turn down a lucrative teaching assistantship in favor of a lower fellowship.

To a minor extent, and for the right reasons, it is possible to bargain for a higher award if you have only received a tuition waiver or a small fellowship (say, below $ 10,000). This needs to be done with tact and with stress on the insufficiency of the funding to meet your basic needs, rather than by pointing out your other options. Money is always a sensitive issue, and departments don’t want to “bid” for students. Weigh carefully whether the slim prospect of a significantly better deal justifies the risk of alienating some people you may soon be working with. Communicate your respect for the department and your correspondents before everything else. And if the financial side permits, you should finally base your choice on the quality of the education only.

The following is a common story: I didn't take college seriously at first and got really bad grades, but I've come around since then and aced the rest (or my master's program). Will those early years come back to haunt me? You know there's a price to be paid, but it's not as high as forefeiting all chances of entering a good graduate school. The adcoms genuinely want to find good students, not deliver moral justice. Recent grades count for a lot, but it's important that these grades are in subjects that matter most to the adcoms: your math and advanced economics classes. If you've taken real analysis etc. at that dark point in your life, you probably need to enroll in metric spaces or measure theory now, or graduate micro theory perhaps, and excel.

Although the disparities in your record will be obvious to the adcom and really don't need that much comment, you can refer to them in your statement. But don't devote much space, except to emphasize that the problem is resolved - sympathy is not a factor in admissions. It may be a good idea to cite a grade-point average for the two most recent years, or for advanced math and economics classes only.

It is quite feasible to enter a PhD program based on average credentials (or, at any rate, accept a less than ideal offer) and transfer after a successful first year. Since your grades in actual PhD coursework are considered to be an excellent indicator, even one term of high grades can greatly improve your appeal, so it is possible to reapply immediately after the first term. Typically you will want a reference from someone in your current program, confirming that it makes sense for someone of your capacity and / or interests to study elsewhere. The new program normally expects you to repeat the first year there.

Now for the unfortunate case that the bad years were the most recent ones. The typical example is a master's program, or beginning of a PhD program, gone awry. Your past achievements count for little once this has happened. Even not very selective departments will be reluctant to consider, let alone fund, you. In some cases, a current professor may be willing to recommend you and emphasize attenuating reasons for your recent performance. Short of this, the PhD may no longer be an option, unless you can study without funding (possibly even do a master's before reapplying).

Which schools should you apply to, and when? Almost everybody tries one or two really prestigious programs (Chicago, Harvard, MIT, Princeton, and Stanford are known as the “Big Five”), more if very confident. Even if you think that admission there is unrealistic, you’ll feel better afterwards for having probed the limit. The rest depends on how competitive you expect your application to be, and how safe you want to play. Normally, the final list will comprise five to eight departments and include one or two back-up choices where admission seems very likely. But if you wouldn’t want the economics PhD unless from a very good school – because you have other options or you can afford to wait and reapply if necessary – it is perfectly reasonable to have no safeties at all. There is a tradeoff between number and quality of applications; they do take time (particularly if you wish to understand and address what is special about the programs you picked), and your recommenders will be better motivated writing to a small number of appropriate choices than lots of inferior or unreachable ones.

How do the schools stack up? The “Big Five” are great in every major subdiscipline of economics. Other renowned programs are on par with them in some areas, but not in all. You’ll need to spend some time looking up the faculty’s research and identifying departments that have at least two or three well-published Associate Professors or Professors working on the topics you’ve earmarked for specialization. Later, on the job market, it will make a big difference who supervised your thesis - besides name recognition, an established professor has the contacts and the influence to get you on shortlists. On the other hand, one should not overestimate one's commitment to a research area before doing graduate coursework. You'll discover that there's more to various topics than you can now imagine, and your professors will sway your inclinations. Flexibility is therefore valuable at the point of entry - hopefully there's consistent quality at some level.

We’re all consulting, and subjecting a good part of our judgement to, “the rankings.” Not to do it would be foolish, since rankings contain fairly objective information, which is hard to come by through our personal contacts. But which ranking to use? There are two major types: reputation (survey) rankings and publication / citation counts. Economists know their colleagues and the work done at the leading departments; in reputation rankings they take all factors into account and provide a more or less balanced assessment. Aggregated over a large and representative sample, these ratings mean a lot. US News & World Report publishes the best-known reputation rankings of graduate programs each year – but the NRC (National Research Council) studies, conducted every ten years, involve many more respondents (from a list of key faculty supplied by the schools’ dean’s offices). The US News ranking, which tries to survey two senior members in each program, garners a response rate of about one-half and basically has an adverse selection problem. The two key indices reported by the NRC are the “program effectiveness” and the “faculty quality” rating, each ranging from 0 to 5, where fives indicate universal agreement that the program is “extremely effective” and the faculty “distinguished.” The grades translate into: 5 – distinguished, 4 – strong, 3 – good, 2 – average, 1 – marginal, 0 – indadequate. You can look up the NRC rankings here .

Publication rankings have some methodological issues: articles published in different journals are hard to compare objectively and page numbers may or may not correlate with quality. Also, some schools excel in research productivity (publication) rankings because they have a handful of individuals who write prolifically in specialized areas - depending on your interests, this may be important or unimportant to you. However, I have come to side with publication rankings for primarily two reasons. (1) The reputation of departments in a professor's mind is really a proxy for publications, and an imperfect proxy at that, constrained by what fields the professor pays attention to, which recent moves she is aware of, etc. (2) It has been argued, and seems true by circumstantial evidence, that publication rankings are a leading indicator of future recognition. Partly, this may be because frontier research turns into mainstream stuff; more importantly, I think, professors correct their biases in response to publication rankings.

There are a good number of recent publication rankings around; I strongly recommend the econphd.net rankings because these use a consistent methodology to rank departments worldwide in fairly narrow subdisciplines, and are moreover the most inclusive (over 60 journals). Clearly subdiscipline rankings are more meaningful than aggregated rankings, since everyone has some preference for a research field within economics. Sampling different rankings, and perhaps averaging them, yields information of poor quality and is, in my view, not worth an applicant's time. Resist the temptation; the econphd.net rankings meet every need and are quite simply the most current and accurate publication rankings available.

It’s not a bad idea to apply to non-U.S. programs, for a couple of reasons. (1) They have much fewer applicants, even when compared to U.S. programs of similar quality. (2) Some programs offer generous funding with most admissions. Elsewhere, applying for available funds may be more involved, but that narrows the pool of applicants; there are information rents to be earned. (3) Every year, some admitted students have their visas denied by U.S. consulates. “At-risk” applicants (this is especially frequent for Chinese) may want an option outside the U.S.

Unfortunately, not every university system operates like the American system. All Canadian and Australian universities, and a few others besides, have very similar application processes to those in the U.S.; the marginal effort in applying to them is not large. (Note, however, that the Australian deadlines are entirely different.) Other good programs require a substantial investment in information search, personal contacts, filling up unfamiliar forms, and supplying extra write-ups and references. One should have a good reason for taking this upon oneself. Perhaps a specialty is particularly well represented in one of these places, or one is a marginal candidate where entry barriers are low and seeks the aforementioned information rents. Some regional specifics follow, although very sparse in some cases. There are no programs to speak of in Africa.

Canada Toronto is traditionally viewed as on par with U.S. top 30 schools, and UBC (the University of British Columbia) currently has research output to rival that of top 20 departments. Next in line are Queen’s University, the University of Montreal (not to be confused with the University of Quebec at Montreal), which are roughly like top 50 U.S. schools, and Western Ontario. Application procedures and deadlines are as in the U.S., and there is similar availability of funding (which admits are automatically considered for). Canadian programs also run like their U.S. counterparts, with equivalent coursework, requirements, and placement mechanisms.

Australia / New Zealand Australia (and New Zealand even more so) is still on the way to forming departments and programs that consistently meet U.S. standards. Traditionally, the Australian National University was the region’s flagship, but the University of Melbourne is now an equal competitor and attracts an impressive list of visitors every year. The University of New South Wales is the third power. Graduates from these programs usually place fairly well with Australian universities. University of Queensland, Monash University, and the University of Auckland (the best in New Zealand) have vestiges of noticeable research. These are not comparable to U.S. top 50 departments. Australia’s academic year begins in late February / early March and runs to December; the admission deadlines are in fall of the preceding year. The application process is similar to that of the U.S., although the GRE tends not to be required. The selection process (for funding in particular) places heavy emphasis on grades and is to an extent controlled by university bureaucrats, rather than the department. Hence the system favors those with good GPAs, even if the coursework is deficient in content.

UK In the London School of Economics and University College, England has two fine American-style programs that bear comparison with U.S. top 20 schools. The application procedures are also similar. There are more good departments, but many of these (most prominently Oxford and Cambridge) separate funding from admission decisions, so that time-consuming applications to multiple bodies with various objectives are required in order to have a reasonable chance of support. Some of these foundations ask for separate essays and references. Funding is generally easier to obtain for European and Commonwealth citizens than for other foreigners. Among the more ambitious programs, e.g. Warwick and Essex, a positive trend is in the making to offer some department-sponsored scholarships. The best schools have two-year coursework sequences akin to those in the U.S. and are earning international recognition for the quality of the training (particularly LSE, UCL, and Warwick).

Europe The centuries-old university systems of the continent still reflect different underlying philosophies. The German and French universities (and related systems such as the Belgian, Austrian, and Dutch) traditionally have no tuition charges, while scholarships are primarily offered to nationals through government offices (or to European citizens, through the European foundations). There are typically no admission cycles or even formal admission processes: rather, one contacts a desired supervisor and “competes” for an available PhD research topic (that may have funding attached to it). The departments are, in the German system, organized into professorships that function as separate institutes (with their own academic and other staff and budgets), working within a clearly demarcated specialty. One seeks affiliation with an institute (headed by a particular professor) and becomes a member of the department through membership in the institute. In the French system, a pattern has emerged in which departments host fairly autonomous research centers, and professors may be affiliated with several of these. This model is also becoming popular elsewhere in Europe and outside the U.S. Some of the centers train and fund graduate students. An outstanding success story of this system is the Toulouse, which must be counted among the world’s top sources of high-quality theory research.

In most cases, one needs to make specific enquiries (by e-mail to a professor or a secretary) to ascertain availability of places and prepare an application. At the leading departments, English is the lingua franca, so despite appearances command of the local language is not necessary. But scholarships and paid assistantships may be difficult or impossible to obtain. Alternative to these idiosyncratic systems, some European universities now offer U.S.-style programs at the department level, with the usual admission requirements, department-sponsored scholarships, and a standard coursework sequence. The University of Bonn, the Stockholm School of Economics, and the European University Institute are examples. Spain has already followed this route for some time; the University Carlos III of Madrid, Autonomous University of Barcelona, and Pompeu Fabra University are all well-established and accessible to international applicants. European education is in a rapid process of transition; those who are interested may benefit from researching some of the departments that are listed at this site for new offerings. I have not discussed Israeli universities, since I am not familiar with the system and because few people seem to consider them due to the security situation. But it should be noted that Israel’s economics departments have been remarkably productive; Tel Aviv University and Hebrew University have two of the most impressive faculties of mathematical economists.

Asia Programs in Asia divide into those that cater to an English-speaking, international population and those that are national in focus and (except in India) conducted in a native language. The former are found in Hong Kong and Singapore and, although mostly populated by students of ethnic Chinese origin, are certainly open to others and in fact offer some of the best scholarship opportunities anywhere. HKUST (the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology) comes closest to being a university of international stature. The National University of Singapore (NUS) is an affluent, well-run institution but has a less serious research culture. Some outstanding theory research originates at Japanese universities, especially the Universities of Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka. But faculty quality is not uniform, and the programs are really not designed to accommodate non-Japanese PhD students. The only major Indian program, at the Delhi School of Economics (the Indian Statistical Institute doesn't systematically train PhDs), is of course conducted in English, but seems to attract little international enrollment - perhaps funding is too limited. Other programs, at the Seoul National University in Korea and Taiwan's best department, Academia Sinica, are also local in scope. For the typical applicant, Hong Kong's universities and NUS are possibly interesting options, since funding is quite generous, but one should be aware that in Singapore, at least, students regard the program more as a jumping-off point to the U.S. than as their PhD training of choice.

Latin America I am not really acquainted with Latin American universities, so I cannot say much. The premier institution of the region is ITAM, the Mexican Autonomous Institute of Technology. Its publication output compares with that of top 100 U.S. departments. Else, and on a smaller scale, only the University of Chile can be said to have a noticeable volume of articles published in international journals. The Institute of Pure and Applied Mathematics (IMPA) in Rio is put on the map by occasional significant technical work.

Applying to economics-related programs at business schools is a popular diversification strategy. For a fact, business schools often pay significantly higher stipends to their students; they don’t attach teaching responsibilities and they usually don’t revise stipends on the basis of performance. Secondly, although business schools accept, on the whole, fewer PhD students than economics departments, their selection criteria are more subjective. Someone who lacks an important math credit or two, and would be disqualified by an econ adcom on that basis, may succeed with a b-school adcom that has less rigid expectations and is impressed with a compensating strength. There is also the argument that the applicant pool to business schools is on average not as strong, since very well-trained students are often theory-inclined and shun the business programs. And finally someone might apply to business schools for the “right reasons”: being interested in the applied economics of management and competition. (Of course, for one whose primary interest is theoretical or empirical finance, business schools are natural first choices. I’m guessing that this guide is mainly read by more generalist economists and have them in mind.)

The application process at business schools is decentralized; submissions are made to, and decisions taken by, a specialty, such as management & organization, business economics, finance, marketing, accounting, etc. One has to commit to a field at the time of application and invest some time and thought into presenting an informed research proposal in that field. Different departments would appeal to different types of economists: business economics to those with somewhat theoretical leanings and interest in industrial organization / game theory, or perhaps empirical macro and public policy. Business economics programs often have an emphasis on micro or macro. Wharton and Haas, for example, are on the public policy end of the spectrum; Northwestern’s MEDS is a game theory powerhouse. Management and organization is typically the least math-oriented department, given to survey, experimental, and other empirical studies. Decision science at business schools is usually a synonym for operations research, but in some places (notably Fuqua and INSEAD) it means choice theory. Under the umbrella of finance, technical general equilibrium research can take place, also time series econometrics. Columbia Business School has a combined finance and economics program.

An individual department typically admits a very small number of students – almost certainly less than ten, and perhaps as few as one. Because all are generously funded (at the major schools), few are expected to reject the offer. This makes the admission rates appear brutal, but of course the applicant pool divides into the specialties – if economics departments admitted people by subdiscipline, the numbers wouldn’t look so different. Without a doubt, however, business PhD programs are becoming more popular and more competitive every year. They are not necessarily easier to get into, in terms of a percentage, but the gamble is less predictable, and this works in certain people’s favor. Because the objective criteria have a smaller weight, the SOP (and any networking one is able to effect) deserves more attention. One should become familiar with the research done by the handful of department members who work in the targeted field: not at a general level, but specifically, by reading into their work, understanding the themes and current directions. The idea is to make a play for one or two of the faculty who are available to supervise by tailoring the proposal to their research program.

Some business economics programs – Harvard Business School and Stanford GSB – make their students take the first year sequence in the economics department. Kellogg also leans strongly toward pure microeconomics; they’ve hired a faculty that wouldn’t make a half-bad econ department by itself. But the majority of PhD programs in business schools end up being less rigorous, partially due to the chosen focus, and put their students through considerably more benign trials. Attrition is minimal. And for all that, placement prospects are typically bright, albeit in most cases restricted to business schools. (And with the caveat that a business economist faces competition from economics PhDs who are frequently preferred on account of research promise.)

A good ranking of business PhD programs does not exist. MBA program rankings are poor substitutes, since they have nothing to do with the faculty’s research output. But the list of potentially eligible programs is fairly small; it’s feasible to research their faculty publications and placements. Business schools with notable PhD programs are Anderson (UCLA), Chicago GSB, Columbia Business School, Fuqua (Duke), Haas (Berkeley), Harvard Business School, INSEAD, Kellogg (Northwestern), Michigan GSB, Olin (Washington University), Simon (Rochester), Sloan (MIT), Stanford GSB, Stern (NYU), Wharton (U Penn). The Darden School at Virginia does not have a PhD program, and Yale’s is, like some others, more of an afterthought than a serious undertaking in its own right.

Plan to mail your applications by early December. (You should check actual deadlines earlier than that: several schools discount or even waive the application fee if you submit completely or partially in November or early December.) You need your final GRE score by end of October or early November: this means, start practicing for the GRE no later than early September. Whatever ETS claims, smart practice can raise your score by hundreds of points. You might get the best results from taking two sample tests in a row, about once a week. (Tests are available from prep books and the software ETS sends you three weeks after registration.) This builds up stress resilience and won’t make you as hostile to the GRE as looking at it every day, over a two-week period, would. Review math, but don’t memorize word lists – increasing the verbal score doesn’t help your application. Sit for the GRE by October, so that you have a chance to retake in November (you are allowed to test once per calendar month). Don’t try to improve a result that’s already good enough (quantitative part is 780 or better) – ETS will report all scores to the departments, and if you do worse the second time around, it discredits your initial, satisfactory performance. Draft your statement of purpose by early November and revise it several times, in intervals, until December until it sounds genuine. If a sentence looks dry, tortuous, or pompous to you, it will also look that way to the reader.

Some programs begin sending out acceptances in early February, but most of the action takes place in the last February week and the first week of March. Almost all schools notify admits by March 15; only waitlisted and rejected applicants will not hear until later. Generally, schools take care of their admits first – many immediately e-mail these applicants when a decision has been reached, though quite a number of schools still send acceptances by post. Rejections almost always come by letter, and weeks later, but if you politely enquire about your status by e-mail, the graduate secretary will usually reply after decisions have been reached. The best way to find out whether decisions are out is to check the Princeton Review graduate message board; information exchange tends to be particularly lively in the economics community. You might also try Who Got In? , a site that exists solely for this purpose. Details from the spring 2002-2004 rounds of admission are available in the decision tables at econphd.net.

You could be waitlisted for admission or for financial aid. It’s hard to predict whether this will eventually result in an offer; sometimes it does and sometimes not. The schools initially take in a group of people of whom they expect a subset, not exceeding the enrollment target, to come. Programs that offer full funding to most or all applicants (such as Stanford) make a conservative round of initial offers, and extend more offers once they get a picture of who’s accepting. Other programs (Chicago, for instance) manage enrollment by giving just a few of the admits money and passing any unclaimed financial aid on to the next best. Harvard makes awards conditional on the applicant’s securing outside funding (ideally, things like NSF grants) to shoulder part of the cost. Thus, some schools have waitlists and others haven’t, and Harvard has something they call a waitlist, which is more like an ultimatum. Waitlists are frustrating. Some claim that you can tip the scales by writing to professors and reiterating your interest in the place, but in reality there’s little you can do except … wait. ( One reader, who was waitlisted at three top schools, eventually got rejected for admission and / or funding by the two departments he actively and frequently contacted while on the waitlist, and received full funding from the third.) Getting waitlisted does not reflect uncertainty about your eligibility (in that case, they’d just reject you), it is a question of enrollment targets. All depends on which way the initial admits decide, and when.

When you have several offers, you start looking for information in earnest. Fortunately, departments will be much more responsive to enquiries when you’ve been admitted, and it’s easy to get in touch with current students. You’ll be committing something between five and seven years to the program, so the chemistry in such correspondence is a factor not to be discounted. You’ll also want to check how many students fail to complete the degree and why (because they are asked to leave? fail the exams? enter better programs? take industry jobs?). Some schools are notorious for taking in a lot more students than they plan to graduate, in order to have a large pool of budget-friendly TAs on hand. The implication is that many won’t pass the qualifying exams or, most commonly, will not continue to get funded at some point. Completion rates of about half are normalcy in many U.S. departments. Few publically report their numbers, but as a rule of thumb, programs with higher drop-out rates tend to offer fewer and / or less generous fellowships in the first year, for obvious reasons.

Another key aspect to consider is the placement track record of the program. Most departments make this information available on their website or in brochures. A historical perspective of the eventual success of PhD training is offered in a 1992 article in the Journal of Economic Education. It ranks departments by current faculty positions occupied by their PhD graduates. The sample includes virtually every academic economist at a PhD-granting school in the U.S. in 1992, making this a particularly objective effort that looks at labor market outcomes which necessarily reflect careful evaluation, since hiring institutions “put the money where the mouth is.” On the negative side, the list is biased towards long-standing and large programs, and recent developments have little influence.

All said, there is a group of U.S. departments that has for decades supplied the great majority of leading economists. The stakes are high, and the competition is accordingly – but rest satisfied that, in giving it your best effort, you’ll serve the interest of our dismal science … as if led by an invisible hand, as they say!

This website uses cookies.

By clicking the "Accept" button or continuing to browse our site, you agree to first-party and session-only cookies being stored on your device to enhance site navigation and analyze site performance and traffic. For more information on our use of cookies, please see our Privacy Policy .

- Resources for Students

- Preparing for graduate school

Considerations for prospective graduate students in economics

Students from a wide variety of backgrounds earn graduate degrees in economics. This includes economics and non-economics majors, those with and without prior graduate training, and those with and without prior economics employment experience.

To decide which program is the best fit, potential students should examine their own qualifications (including their GRE scores, their GPA, and their mathematical preparation) as well as the methodological approach, fields of specialization, predominant ideology, size of program, program culture (cooperative, competitive, etc.), typical time-to-degree, required examinations, financial aid, emphasis on mathematics, job prospects, and location of the programs to which they apply.

For those who wish to pursue academic careers, the availability of training in teaching methods during graduate school may also be a consideration.

Some applicants find it useful to contact students at their target programs to find out about current students' perceptions and experiences. Keep in mind that faculty tend to be fairly mobile throughout their careers, so it may be risky to choose a program out of a desire to work with one specific faculty member.

Further reading for students considering graduate study in economics

- Dr. Ajay Shenjoy at UC-Santa Cruz has a YouTube video describing applying to an Economics PhD program in the U.S.

- The Fed has a two-year Research Assistants program that can provide training and experience for those who want to pursue a graduate degree in economics.

- Professor Sita Slavov has a page of tips for applying to PhD Programs in economics .

- The Occidental College Department of Economics has posted a guide called Becoming an Economist .

- Ceyhun Elgin and Mario Solis-Garcia, former PhD students at the University of Minnesota have written: So, you want to go to grad school in Economics? A practical guide of the first years (for outsiders) from insiders.

- The Summer 2014 CSWEP newsletter includes a guide for Getting Into and Finishing a PhD Program .

- The Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession (CSWEP) has a list of its newsletter articles for specific audiences , including those focused on undergraduate and graduate students.

- Professor William D. Craighead has a webpage with advice for students interesting in pursuing graduate studies in economics.

- Professor Greg Mankiw at Harvard University has a blog with advice for grad students on various topics.

- Professor David Colander's " The Making of an Economist Redux " reports the findings of surveys and interviews with graduate students at top-ranking economics graduate programs.

- Professors Wendy Stock and John Siegfried published a paper that reports on 15 Years of Research on Graduate Education in Economics: What Have We Learned?

- Professor Marie desJardins has a paper on " How to Succeed in Graduate School: A Guide for Students and Advisors ."

- Professor Dick Startz offers " A Guide for UCSB Undergraduates Considering a PhD in Economics ."

- The A.V. Club

- The Inventory

Support Quartz

Fund next-gen business journalism with $10 a month

Free Newsletters

The complete guide to getting into an economics PhD program

Back in May, Noah wrote about the amazingly good deal that is the PhD in economics. Why? Because:

- You get a job.

- You get autonomy.

- You get intellectual fulfillment.

- The risk is low.

- Unlike an MBA, law, or medical degree, you don’t have to worry about paying the sticker price for an econ PhD: After the first year, most schools will give you teaching assistant positions that will pay for the next several years of graduate study, and some schools will take care of your tuition and expenses even in the first year. (See Miles’s companion post for more about costs of graduate study and how econ PhD’s future earnings makes it worthwhile, even if you can’t get a full ride.)

Of course, such a good deal won’t last long now that the story is out, so you need to act fast! Since he wrote his post , Noah has received a large number of emails asking the obvious follow-up question: “How do I get into an econ PhD program?” And Miles has been asked the same thing many times by undergraduates and other students at the University of Michigan. So here, we present together our guide for how to break into the academic Elysium called Econ PhD Land:

(Note: This guide is mainly directed toward native English speakers, or those from countries whose graduate students are typically fluent in English, such as India and most European countries. Almost all highly-ranked graduate programs teach economics in English, and we find that students learn the subtle non-mathematical skills in economics better if English is second nature. If your nationality will make admissions committees wonder about your English skills, you can either get your bachelor’s degree at a—possibly foreign—college or university where almost all classes are taught in English, or you will have to compensate by being better on other dimensions. On the bright side, if you are a native English speaker, or from a country whose graduate students are typically fluent in English, you are already ahead in your quest to get into an economics PhD.)

Here is the not-very-surprising list of things that will help you get into a good econ PhD program:

- good grades, especially in whatever math and economics classes you take,

- a good score on the math GRE,

- some math classes and a statistics class on your transcript,

- research experience, and definitely at least one letter of recommendation from a researcher,

- a demonstrable interest in the field of economics.

Chances are, if you’re asking for advice, you probably feel unprepared in one of two ways. Either you don’t have a sterling math background, or you have quantitative skills but are new to the field of econ. Fortunately, we have advice for both types of applicant.

If you’re weak in math…

Fortunately, if you’re weak in math, we have good news: Math is something you can learn . That may sound like a crazy claim to most Americans, who are raised to believe that math ability is in the genes. It may even sound like arrogance coming from two people who have never had to struggle with math. But we’ve both taught people math for many years, and we really believe that it’s true. Genes help a bit, but math is like a foreign language or a sport: effort will result in skill.

Here are the math classes you absolutely should take to get into a good econ program:

- Linear algebra

- Multivariable calculus

Here are the classes you should take, but can probably get away with studying on your own:

- Ordinary differential equations

- Real analysis

Linear algebra (matrices, vectors, and all that) is something that you’ll use all the time in econ, especially when doing work on a computer. Multivariable calculus also will be used a lot. And stats of course is absolutely key to almost everything economists do. Differential equations are something you will use once in a while. And real analysis—by far the hardest subject of the five—is something that you will probably never use in real econ research, but which the economics field has decided to use as a sort of general intelligence signaling device.

If you took some math classes but didn’t do very well, don’t worry. Retake the classes . If you are worried about how that will look on your transcript, take the class the first time “off the books” at a different college (many community colleges have calculus classes) or online. Or if you have already gotten a bad grade, take it a second time off the books and then a third time for your transcript. If you work hard, every time you take the class you’ll do better. You will learn the math and be able to prove it by the grade you get. Not only will this help you get into an econ PhD program, once you get in, you’ll breeze through parts of grad school that would otherwise be agony.

Here’s another useful tip: Get a book and study math on your own before taking the corresponding class for a grade. Reading math on your own is something you’re going to have to get used to doing in grad school anyway (especially during your dissertation!), so it’s good to get used to it now. Beyond course-related books, you can either pick up a subject-specific book (Miles learned much of his math from studying books in the Schaum’s outline series ), or get a “math for economists” book; regarding the latter, Miles recommends Mathematics for Economists by Simon and Blume, while Noah swears by Mathematical Methods and Models for Economists by de la Fuente. When you study on your own, the most important thing is to work through a bunch of problems . That will give you practice for test-taking, and will be more interesting than just reading through derivations.

This will take some time, of course. That’s OK. That’s what summer is for (right?). If you’re late in your college career, you can always take a fifth year, do a gap year, etc.

When you get to grad school, you will have to take an intensive math course called “math camp” that will take up a good part of your summer. For how to get through math camp itself, see this guide by Jérémie Cohen-Setton .

One more piece of advice for the math-challenged: Be a research assistant on something non-mathy . There are lots of economists doing relatively simple empirical work that requires only some basic statistics knowledge and the ability to use software like Stata. There are more and more experimental economists around, who are always looking for research assistants. Go find a prof and get involved! (If you are still in high school or otherwise haven’t yet chosen a college, you might want to choose one where some of the professors do experiments and so need research assistants—something that is easy to figure out by studying professors’ websites carefully, or by asking about it when you visit the college.)

If you’re new to econ…

If you’re a disillusioned physicist, a bored biostatistician, or a neuroscientist looking to escape that evil Principal Investigator, don’t worry: An econ background is not necessary . A lot of the best economists started out in other fields, while a lot of undergrad econ majors are headed for MBAs or jobs in banks. Econ PhD programs know this. They will probably not mind if you have never taken an econ class.

That said, you may still want to take an econ class , just to verify that you actually like the subject, to start thinking about econ, and to prepare yourself for the concepts you’ll encounter. If you feel like doing this, you can probably skip Econ 101 and 102, and head straight for an Intermediate Micro or Intermediate Macro class.

Another good thing is to read through an econ textbook . Although economics at the PhD level is mostly about the math and statistics and computer modeling (hopefully getting back to the real world somewhere along the way when you do your own research), you may also want to get the flavor of the less mathy parts of economics from one of the well-written lower-level textbooks (either one by Paul Krugman and Robin Wells , Greg Mankiw , or Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok ) and maybe one at a bit higher level as well, such as David Weil’s excellent book on economic growth ) or Varian’s Intermediate Microeconomics .

Remember to take a statistics class , if you haven’t already. Some technical fields don’t require statistics, so you may have missed this one. But to econ PhD programs, this will be a gaping hole in your resume. Go take stats!

One more thing you can do is research with an economist . Fortunately, economists are generally extremely welcoming to undergrad RAs from outside econ, who often bring extra skills. You’ll get great experience working with data if you don’t have it already. It’ll help you come up with some research ideas to put in your application essays. And of course you’ll get another all-important letter of recommendation.

And now for…

General tips for everyone

Here is the most important tip for everyone: Don’t just apply to “top” schools . For some degrees—an MBA for example—people question whether it’s worthwhile to go to a non-top school. But for econ departments, there’s no question. Both Miles and Noah have marveled at the number of smart people working at non-top schools. That includes some well-known bloggers, by the way—Tyler Cowen teaches at George Mason University (ranked 64th ), Mark Thoma teaches at the University of Oregon (ranked 56th ), and Scott Sumner teaches at Bentley, for example. Additionally, a flood of new international students is expanding the supply of quality students. That means that the number of high-quality schools is increasing; tomorrow’s top 20 will be like today’s top 10, and tomorrow’s top 100 will be like today’s top 50.

Apply to schools outside of the top 20—any school in the top 100 is worth considering, especially if it is strong in areas you are interested in. If your classmates aren’t as elite as you would like, that just means that you will get more attention from the professors, who almost all came out of top programs themselves. When Noah said in his earlier post that econ PhD students are virtually guaranteed to get jobs in an econ-related field, that applied to schools far down in the ranking. Everyone participates in the legendary centrally managed econ job market . Very few people ever fall through the cracks.

Next—and this should go without saying— don’t be afraid to retake the GRE . If you want to get into a top 10 school, you probably need a perfect or near-perfect score on the math portion of the GRE. For schools lower down the rankings, a good GRE math score is still important. Fortunately, the GRE math section is relatively simple to study for—there are only a finite number of topics covered, and with a little work you can “overlearn” all of them, so you can do them even under time pressure and when you are nervous. In any case, you can keep retaking the test until you get a good score (especially if the early tries are practice tests from the GRE prep books and prep software), and then you’re OK!

Here’s one thing that may surprise you: Getting an econ master’s degree alone won’t help . Although master’s degrees in economics are common among international students who apply to econ PhD programs, American applicants do just fine without a master’s degree on their record. If you want that extra diploma, realize that once you are in a PhD program, you will get a master’s degree automatically after two years. And if you end up dropping out of the PhD program, that master’s degree will be worth more than a stand-alone master’s would. The one reason to get a master’s degree is if it can help you remedy a big deficiency in your record, say not having taken enough math or stats classes, not having taken any econ classes, or not having been able to get anyone whose name admissions committees would recognize to write you a letter of recommendation.