Reimagining adult education and lifelong learning for all: Historical and critical perspectives

- Introduction

- Published: 30 May 2022

- Volume 68 , pages 165–194, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Aaron Benavot ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4115-0323 1 ,

- Catherine Odora Hoppers ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5324-7371 2 ,

- Ashley Stepanek Lockhart ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6647-2391 3 &

- Heribert Hinzen 4

8136 Accesses

16 Citations

11 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This special issue of the International Review of Education explores the future of adult education and lifelong learning from different historical and contemporary vantage points. It starts from a premise that the international adult education community is poised at a pivotal historical juncture. Looming large are the educational implications of climate change, environmental degradation and unsustainable lifestyles; widening social and economic divisions; weakening democratic institutions and processes; outbreaks of war, conflict and hate crimes; massive shifts in technology, globalisation and workplace relations; and migration movements and intergenerational demographic trends. How might the adult education community respond to these shifting realities and to what appear to be fragile and uncertain futures? The convening of the Seventh International Conference on Adult Education (CONFINTEA VII) provides a timely opportunity for the proponents and practitioners of adult education to consider ways of addressing these serious challenges.

Bringing our diverse experiences from the worlds of scholarship and policymaking to our collaboration as joint guest editors of this special issue, we see value in posing thought-provoking questions, recasting historical ideas in a new light, interrogating concepts and well-established policies, as a means of opening new windows into the future of adult education. Although we employ different writing styles and narrative voices, as is discernible in this introductory essay, we share a belief that now is a crucial time for the international adult education community to reimagine the purpose, vision, scale and scope of lifelong learning for adults. In addition to the points raised in the articles featured in this special issue, we put forward a series of suggestive guideposts to facilitate dialogue and debate. These include: (1) a retrospective look at the ambitious visions of the adult education community in the aftermath of the Second World War, when the foundational concept of “fundamental education” (UNESCO 1949a ) held sway; (2) possible openings to reposition adult education and lifelong learning in light of the ongoing integration of the agendas of global development, education and sustainability; and (3) notable insights and ideas emerging from the African experience and perspective of adult education and lifelong learning.

The articles featured in this special issue explore ways of expanding and institutionalising adult education for all within a lifelong learning perspective. They seek to contribute to discussions that bridge the CONFINTEA process of reviewing and improving with the wider 2030 Agenda of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and, in so doing, carve out new vistas on the futures of adult education. In the final section of our editorial, we draw out key findings from the articles, together with ideas explicated in this Introduction, to formulate a succinct set of recommendations for due consideration.

Preliminary remarks

In this introductory essay, we refer to the adult education community and its organisational entities as an “adult education movement”. The reasons for this are many. First, it is worth recalling that organised labour and trade unions have been among the strongest supporters – and sometimes providers – of worker education in many countries and viewed expanding education opportunities for workers as part of a larger political agenda to secure workers’ rights (ILO 2007 ). Second, references to an “adult education movement” can be found in many national contexts, including the United States (Knowles 1994 ), Canada (Selman and Selman 2009 ) and South Africa (Aitchison 2003 ). Third, in recounting its history, the International Council for Adult Education (ICAE) refers to an international adult education movement: “The idea of having an international non-governmental body for the adult education movement was born in a discussion in a room in the Tokyo Prince Hotel in Japan where the Third International Conference on Adult Education was taking place in July of 1972” (ICAE, n.d., emphasis added). Fourth, some histories of adult and continuing education also use the term “movement” (Shannon 2015 ). Fifth, several key global education policy commitments have been framed as “movements” – examples include “the EFA movement” or the “functional literacy movement” or a “mass literacy movement”. Indeed, scholars of adult education have analysed the adult education field in the context of social movements (English and Mayo 2012 ). A recent indication of a growing adult education movement is the re-launch of ICAE’s flagship journal Convergence , after a break of more than a decade, focusing on areas like gender and environment, knowledge democracy and professional strengthening (Hall and Clover 2022 ), as well as links between ICAE and UNESCO (Hinzen 2022 ).

Our reference to an “international adult education movement” here is also meant to serve as a counterweight to the marginalisation of adult education around the adoption of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Representatives of the international adult education community were present at the Global Education for All Meeting in Muscat (May 2014) and later at the World Education Forum in Incheon (May 2015) during lively discussions over the post-2015 global education goal and its targets. However, when consensus emerged around several contentious issues, advocates of adult learning and education (ALE) were asked to get under the big tent notion of “lifelong learning”, to be mentioned in the formulation of the fourth Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 4) itself,

Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all (UN 2015 , p. 14).

They were expected to be content with three – potentially four – targets that referenced adults: “women and men” should be provided with equal access “to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university” (SDG Target 4.3; ibid., p. 20); “youth and adults” should be equipped with “relevant skills, including technical and vocational skills, for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship” (SDG Target 4.4; ibid.); “all youth and a substantial proportion of adults, both men and women” should be enabled to “achieve literacy and numeracy” (SDG Target 4.6; ibid., p. 21), and finally “all learners” – including adults – should “acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development …” (SDG Target 4.7; ibid.). In agreeing to work under the banner of lifelong learning, the ALE leadership effectively conceded explicit references to the provision of adult learning and education inside the 10 SDG targets instead of pushing for a dedicated separate one, and thus inadvertently contributed to its subsequent invisibility (Benavot 2018 ). In this introductory essay, our reference to international adult education as a “movement” serves to reclaim the value, power and spirit of ALE as a collective and organisational manifestation.

In the next section, we focus on how supporters of adult education fashioned and established a broad international vision of the field in the post-World War II era. This focus is not meant to minimise the importance of international activities of adult educators in the first half of the 20th century. For example, the first international conference of adult education was held in 1929, in Cambridge (England), under the auspices of the World Association for Adult Education (WAAE), which was founded by Albert Mansbridge in 1918 (Ireland and Spezia 2014 ). Representatives of 33 governments and more than 300 stakeholders attended the one-week conference. In conjunction with this initial WAAE meeting, authors from 26 countries contributed chapters to the first International Handbook on Adult Education (ibid.).

Adult education: an international movement born out of war and crisis

In the aftermath of the Second World War, which resulted in unimaginable death, destruction and discontent, many international leaders sought to promote peace and understanding by eradicating “ignorance” and “illiteracy” in the world. Footnote 1 As the Preamble of the Constitution of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) famously states: “since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men [and women] that the defences of peace must be constructed” (UNESCO 1945 , p. 1). Promoting international understanding and diminishing the prospects of war were not the only motives behind the push to expand education and increase literacy. International leaders at that time also articulated economic and social motives while addressing the root causes of the crisis.

Three-fourths of the world’s people today are under-housed, under-clothed, under-fed, illiterate. Now, as long as this continues to be true, we have a very poor foundation upon which to build the world (Yan Yangchu, quoted in Boel 2016 , p. 154).

These words by the Chinese educator Yan Yangchu, aka James Yen, a fierce advocate of adult literacy campaigns and mass education movements in pre-War China, helped convince UNESCO delegates to establish its first flagship programme – the Fundamental Education Programme – in May 1946. Education should involve instruction in all areas that

contribute to the development of well-rounded, responsible members of society … it is proposed that the Organization [UNESCO] should launch, upon a world scale, an attack upon ignorance by helping all Member States who desire such help to establish a minimum Fundamental Education for all their citizens (internal UNESCO Memorandum, quoted in Boel 2016 , pp. 153–154). Footnote 2

UNESCO’s understanding of “fundamental education” in these early years was humanistic, global, holistic and equity-oriented (Boel 2016 ; Watras 2010 ). It went beyond adult literacy campaigns to include a wide array of projects and programmes targeting marginalised adults and out-of-school youth and can thus be regarded as a forerunner of lifelong and life-wide education (Elfert 2018 ). The first of the 12 Monographs on Fundamental Education, published by UNESCO in 1949, stressed that “the aim of all education is to help men and women to live fuller and happier lives” (UNESCO 1949a , p. 9). In practical terms, the idea was that education would alter basic living conditions in social life through, for example, health education, domestic and vocational skills, knowledge and understanding of human society, including economic and social organisation, law and government. Fundamental education was thus an integrated community strategy to improve material conditions and reduce the impact of poverty as preconditions for an array of educational activities that would support the development of individual qualities needed “to live in the modern world, such as personal judgment and initiative, freedom from fear and superstition, sympathy and understanding for different points of view” (UNESCO 1949a , p. 11). Footnote 3 The notion and value of fundamental education gained further legitimacy after countries adopted Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UN 1948 ), which stated that education at the “fundamental” stage was to be free. Footnote 4

Soon afterwards, when the (First) International Conference on Adult Education (CONFINTEA I) convened in Helsingør (Elsinore), Denmark in 1949, the 106 delegates agreed that adult education could and should play a formative role in fostering international understanding and world peace. Footnote 5 The idea was that adult education should serve as a bridge for intercultural exchange and reconciliation by contributing to the study of the life and circumstances of other peoples, their history, literature, art and other cultural achievements, as well as promoting technical assistance in low-income countries, and supporting the efforts of international organisations and the United Nations (UNESCO 1949b , pp. 28–30). The conference also embraced a decidedly holistic view of adult education, arguing that given the “deterioration in the material, spiritual and moral fabric of civilized life” (ibid., p. 28), adult education should help “rehabilitate world society with a new faith in [its] essential values and using knowledge in the pursuit of truth, freedom, justice and toleration” (ibid.). Although the delegates could not settle on a precise definition of adult education, they did agree on certain humanistic principles as a basis for expanding the adult education movement. These principles included, for example, the idea that adult education should practise a spirit of tolerance, uphold the value of freedom of thought and discussion, promote the study of world problems from both national and international perspectives, and emphasise the positive role of voluntary associations. The inspiring vision advanced at CONFINTEA I – to transform adults’ engagement within their communities and in the world – was clearly aligned with the growing interest in “fundamental education” as well as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UN 1948 ).

UNESCO’s Fundamental Education Programme (FEP) sprouted many shoots during its heyday (Watras 2010 ). In 1947, UNESCO and the Haitian government inaugurated a first pilot project in the Marbial Valley region, a poor rural area of southern Haiti, with more than 20 trainers and teachers. To share ideas and experiences across newly established projects, UNESCO launched an Associated Projects scheme in 1949, which included more than 34 projects in 15 countries by 1951 (Boel 2016 ). UNESCO’s Regional Centre of Fundamental Education in Mexico opened its doors in 1951, and became a training centre for fundamental education teachers, trainers and professionals. A year later, UNESCO established another training centre in Egypt and passed a resolution creating an international network of Fundamental Education Centres. During the FEP’s existence (1946–1958), UNESCO was active in expanding literacy campaigns, building community centres, introducing new crops, promoting handicrafts and reducing disease in more than 60 of the then 82 UNESCO Member States. In many instances, these activities involved other United Nations (UN) agencies such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO – raising awareness of land erosion), the World Health Organization (WHO – promoting hygiene and health) and the International Labour Organization (ILO – fostering handicrafts and local industries). These projects were designed to be participatory, empowering and contextualised. As Conrad Opper, then Director of UNESCO’s Fundamental Education Pilot Project in Haiti, stated:

Fundamental education … means a mass attack on poverty, disease and ignorance … Fundamental education must aim at changing lives from within. It must not impose on a community large social and economic development schemes, but lead the people patiently and unobtrusively to work for their own improvement, using as far as possible their own social institutions and their own leadership …. There is … no blue-print for fundamental education. Everything will depend on the team resources available, the human resources of the people and the way in which these two forces are brought together … fundamental education is not just bull-dozers, penicillin and cinema vans; it is bringing new life to a people. And in these sombre days, mending a life is a far tougher job than ending it (Opper 1951 , p. 5).

In time, however, the ambitions of the FEP collided with insufficient financial resources from UNESCO Member States to carry out additional projects and expand the network of training centres (Watras 2010 ). In addition, critiques about the notion and practice of fundamental education emerged both externally and internally (Boel 2016 ). The UN took issue with the scale and scope of FEP activities. UNESCO and the other specialised agencies (ILO, FAO and WHO) argued that they should have programme-execution responsibilities in their specific fields of competence and that the UN’s exclusive function should be inter-agency coordination. The UN, on the other hand, expressed concerns that the all-inclusive nature of “fundamental education” meant that UNESCO was moving beyond education into other sectors, and insisted that the work of the FEP be seen as only one aspect of the broader process of community development. Internally, several UNESCO Member States, such as the United States, took issue with the largesse of funds allocated to FEP projects and the lack of clearly defined outcomes and measurable results (Boel 2016 ). While data were collected on “the number of teachers and trainers trained, new literates, community centres, new crops introduced, handicraft production and reduction of victims of diseases”, it was more challenging to determine the number of adults leading “fuller and happier lives” (ibid., p. 161). External critiques of and internal opposition to fundamental education were followed by executive deliberations and commissioned reports which raised questions about the impact of UNESCO’s flagship programme and whether it was meeting its lofty ideals. In 1958, UNESCO’s General Conference decided to drop the use of this foundational concept, close the Fundamental Education division, merge it into another unit, and substitute less contentious terms like “adult education”, “adult literacy” and “youth activities” (Watras 2010 ). The final Monograph in the series on Fundamental Education was published in 1959 (Boel 2016 ).

Intensifying crises, different in scale and scope

Today, some 75 years after the FEP and the establishment of CONFINTEA conferences to review and improve ALE strategies, many more adults are considered “functionally literate” and rates of adult literacy have increased – albeit based on narrow definitions of literacy, conventionally measured (Benavot 2015 ). Despite this progress, adult literacy rates remain shockingly low in many countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. In addition, there are significant disparities in literacy rates according to household income, geographical location, ethnicity and gender. For example, in 2020, globally, 90% of men over the age of 15 were defined as “literate”, whereas only 83% of women were so defined (UNESCO 2021a , p. 303). Indeed, women constitute nearly two-thirds of all “illiterate” adults in the world and this share has changed little since the turn of the century. Overall, recent progress in adult literacy, conventionally understood, has been painstakingly slow. It mainly reflects demographic shifts in life expectancy and fertility and higher levels of formal education among younger birth cohorts and only minimal effects of increased access to adult literacy programmes (UNESCO 2015a , pp. 143–144, 2020a , p. 268).

Participation rates in ALE programmes vary greatly around the world (UIL 2019 ). Limited and unverified information on ALE participation rates is available for only 96 UNESCO Member States, entirely based on country self-reports in the survey conducted by the UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (UIL) for the Fourth Global Report on Adult Learning and Education ( GRALE 4 ). Of these countries, 28 reported adult participation rates below 5%; 24 countries reported participation rates between 5% and 10%; 11 countries reported rates between 11% and 19%; 19 countries reported rates between 20% and 50%; and only 14 countries reported adult participation rates above 50% (ibid.). We have almost no reliable information about ALE participation for the remaining 97 UNESCO Member States.

Undoubtedly, when the international adult education community convenes for CONFINTEA VII in Marrakech, Morocco in June 2022, it will recommit itself to the strengthening and funding of ALE and to boosting participation in ALE programmes, even in the absence of reliable data. It remains to be seen whether the strategies and policies emerging from the conference will also target participation among vulnerable groups – for example, minorities, migrants and refugees; people with disabilities; older adults – who require dedicated systems of financing and other support.

Notwithstanding limited ALE progress in recent decades, its endeavours pale when considered alongside emerging challenges and crises, which are profound in scale and scope. Growing evidence suggests that life on Earth hangs in the balance and ALE must be part of a comprehensive solution. Carefully researched scientific reports present disturbing evidence of the impact of human activities on species extinction, Footnote 6 climate change, Footnote 7 and water scarcity, Footnote 8 which are likely to adversely impact natural ecosystems, animal species and many human populations.

The list of anthropogenic-induced tipping points that are growing nearer or being crossed on our planet is long. Researchers have devised quantitative measures to determine if humanity is operating within the limits of nine boundaries – namely, climate change, ocean acidification, stratospheric ozone depletion, interference with global phosphorus and nitrogen cycles, rate of biodiversity loss, global freshwater use, land system change, aerosol loading, and chemical pollution (Asher 2021 ). At present, we have exceeded four of these boundaries (biodiversity loss, nitrogen cycle, land system change and climate change) and we are on the cusp of exceeding another four – all but the chemical boundary.

Concurrently, language vitality is on the wane: at least 50% of the world’s more than six thousand languages are losing speakers, especially among the young (UNESCO 2003 ). UNESCO estimates that, in most world regions, about 90% of the languages still in use today may be replaced by nationally dominant languages by the end of the 21st century. The endangerment of languages is especially profound among Indigenous peoples, a sign of further denigration of their heritage and knowledge systems (Dei 2002 ).

It is projected that most people on Earth today are likely to experience another extreme pandemic like COVID-19 in their lifetime (Marani et al. 2021 ). WHO’s Coronavirus Dashboard estimates that globally, since the onset of COVID-19, there have been more than half a billion confirmed cases and at least 6.26 million deaths (WHO 2022 ). As the pandemic spread, and communities were placed in lockdowns or restricted movement, main modes of formal and non-formal education either ceased or were disrupted. At its peak, the COVID-19 pandemic forced 194 countries to close their schools, affecting nearly 1.6 billion children and youth (UNESCO 2022 ). At least one in three students were unable to access remote learning (UNICEF 2020 ). In addition to educational disruption and learning loss, school closures massively eroded children’s – and adults’ – sense of routine, heightened their perceptions of fragility, and exacerbated socio-economic and racial inequalities in accessing education, as some were able to continue learning remotely, often by digital means, while many others could not.

Adult literacy and numeracy programmes were also hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. A rapid assessment in mid-2020 suggested that 90% of adult literacy programmes were partially or even fully suspended (UNESCO 2020a ). Moreover, with a few exceptions (e.g. Chad and Senegal), ALE programmes were mostly absent from countries’ initial education response plans to the pandemic (UNESCO 2020b ). Among member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a recent study estimated that pandemic-induced shutdowns of economic activities decreased workers’ participation in non-formal learning by an average of 18%, and in informal learning by 25% (OECD 2021 ).

Can adult education reimagine itself at this critical juncture in human history?

Given the profound and urgent crises facing humanity today, the question is whether the adult education movement can rise to the occasion, mobilise the political will and financial resources, and reimagine its purpose and trajectory in the coming decades. In the aftermath of the Second World War, adult educators faced unimaginable moral, spiritual, economic and political crises and raised the banner of Fundamental Education as an innovative strategy for transforming communities. The current multifaceted crises pose equally daunting – although perhaps less apparent – challenges, so the issue arises once again: Can leaders of today’s adult education community find the wherewithal to raise new banners that address the unprecedented forces impacting our communities and villages, our cities and countries – indeed, the future existence of our planet? Can the adult education movement effectively serve as a bridge for intercultural exchange and reconciliation, and as a platform that brings together actors and agencies with distinctive worldviews and interests to work together in common purpose?

There are certainly signs of a greater recognition of the importance and value of ALE today, though they are far from universal. To list a few: adults are living longer, generating more demand for learning throughout life in diverse settings and formats. New technologies, growing automation and shifting locations of production are influencing the skills needed by, and career trajectories of, workers in evolving labour markets. National populations are growing more diverse, partly due to intensified migration, thus highlighting the role of adult education in promoting nation-building and social solidarity. Many young adults have been leaving formal education due to the impact of higher costs, lower quality and remote instruction and will be looking for new pathways of learning as adults. Growing numbers of refugees and peoples displaced due to armed conflict have increased the need for adult education in emergencies as well as opportunities for (re)training and skill acquisition. Adult education is expected to contribute to greater awareness of climate change and to promote resilience through enhanced knowledge of mitigation and adaptation strategies. The turn away from democracy and the weakening of public support for democratic institutions (Freedom House 2022a , b ) are increasing interest in civic education and global citizenship education for learners of all age brackets. In short, despite persistent impediments, the rationale for governments, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and the private sector to invest in adult education could not be stronger and more urgent.

ALE and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

Unlike the past, when the voices of adult educators seeking to transform the world may have been faint echoes in the ears of government leaders, today they can collaborate with numerous governmental and non-governmental actors within a comprehensive international development agenda: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN 2015 ). Education and lifelong learning Footnote 9 are understood to be drivers of broad social, political, economic and environmental transformation. The fact that promoting “lifelong learning opportunities for all” (SDG 4; UN 2015 ) has been adopted as an official international development priority is unprecedented.

References to ALE are found throughout the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and their respective Targets – sometimes explicitly, often implicitly. In addition to the global goal dedicated to Education (SDG 4), there are numerous direct and indirect references to ALE in the other 16 SDGs (ISCU and ISSC 2015 ). As John Oxenham noted:

Each of the 17 goals has a set of targets and each set has at least one target that deals with or implies learning, training, educating or at the very least raising awareness for one or more groups of adults. Goals 3 [health], 5 [women], 8 [economy], 9 [infrastructure], 12 [consumption] and 13 [climate] especially include targets that imply substantial learning for ranges of adults – and organised, programmatic learning at that (John Oxenham, quoted in Rogers 2016 , p. 29).

Moreover, the lasting impact of education on many SDGs is apparent in two other ways (UNESCO 2016 , p. 368 ff.). First, when SDG Indicators (UIS 2018 ) are disaggregated by education levels, there is often a significant link between more educated adults and various sustainability outcomes, thereby confirming long-standing research findings. Second, progress in the 2030 Agenda depends on whether and how formal and non-formal education builds critical capacity in society. Improvements in health and sanitation services, agricultural productivity, climate change mitigation and crime reduction – to name a few – are contingent on training professionals who can implement policies, lead information campaigns, and communicate with targeted communities. Whether considered non-formal adult education or university-based extension services (Rogers 2016 ), adult education programmes are found in many fields – e.g. health promotion, agriculture, human resource enhancement, environmental management and community development – but there is rarely a co-ordinating idea illuminating the work and purposes of such programmes. Small ALE fiefdoms, under the purview of non-education ministries or non-state actors, often remain unaware of the shared world they occupy (UNESCO 2021a ), and ministries of education have few incentives to accurately reflect the vast and colourful portrait consisting of diverse adult education activities. If ALE is an essential means of capacity building, then the need for such capacities is acute in many under-resourced settings. Effective capacity building through ALE can significantly contribute to SDG progress. And yet, ALE continues to play the role of an “invisible friend” for the SDGs (Benavot 2018 ).

Future visions of ALE and lifelong learning

Until recently, the main foci of the international educational community have been on universal completion of primary education, reduced gender disparities in basic education, enhanced quality education, mainly in terms of increased learning levels, and a growing interest in early childhood care and education. Apart from emanating conventional calls for fostering adult literacy and life skills, the Jomtien and Dakar conferences (UNESCO 1990; WCEFA 2000) had little to say about ALE beyond a recognition of intergenerational or family-based literacy acquisition. The broader opportunity to recognise the secondary benefits of ALE for sustainable development was missed.

In addition to deploying its convening power to bring together governments and other stakeholders in major policy-generating international gatherings, UNESCO has also commissioned over the years four forward-looking reports:

Learning to be: The world of education today and tomorrow (Faure et al. 1972 )

Learning: The treasure within. Report to UNESCO of the International Commission on Education for the 21st Century (Delors et al. 1996 )

Rethinking education: Towards a global common good? (UNESCO 2015b )

Reimagining our futures together: A new social contract for education (UNESCO 2021b ).

In many ways it is in and through these highly influential reports that the broad value of lifelong education and lifelong learning is fleshed out (see Biesta 2021 ). Arguably, the rationale and groundwork for the inclusion of lifelong learning in the SDGs were laid in the first two reports listed above. Nevertheless, an interesting contradiction has arisen: while members of the international community may embrace the term and sometimes the discourse of lifelong learning, in practice, they often do so in truncated ways – highlighting some aspects (early childhood education or formal education) and downplaying others (adult and non-formal education). Notable exceptions are the European Union (through its adult education targets and monitoring efforts) and the OECD (through skills assessments in its Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies [PIAAC]), which continue to focus on ALE as a critical policy lever – albeit dominated by economic considerations. In addition, there is a small group of countries – for example, Canada, Germany, Japan, the Republic of Korea and Singapore – which are deeply committed to implementing lifelong education policies. Footnote 10

It is also noteworthy how ALE and lifelong learning are conceived in these two recent UNESCO reports: Rethinking education (UNESCO 2015b ) and Reimagining our futures together: A new social contract for education (UNESCO 2021b ). The first report emphasises the humanistic and holistic nature of lifelong learning:

It is necessary … to reassert a humanistic approach to learning throughout life for social, economic and cultural development. Naturally, focus on particular dimensions may shift in different learning settings and at different stages of the life course. But in reaffirming the relevance of lifelong learning as the organizing principle for education, it is critical to integrate the social, economic and cultural dimensions (UNESCO 2015b , pp. 37–38).

The report further underscores the moral and ethical issues raised in and through lifelong learning:

… the concept of humanism has given rise to several, often conflicting, interpretations, each of which raises fundamental moral and ethical issues that are clearly matters of educational concern. It can be argued that sustaining and enhancing the dignity, capacity and welfare of the human person in relation to others, and to nature, should be the fundamental purpose of education in the twenty-first century. The humanistic values that should be the foundations and purpose of education include: respect for life and human dignity, equal rights and social justice, cultural and social diversity , and a sense of human solidarity and shared responsibility for our common future (UNESCO 2015b , p. 38; emphases in original).

The timing of the Reimagining our futures together report (UNESCO 2021b ) – amid a global pandemic, growing international crises, and in the run-up to CONFINTEA VII – means that it too is likely to influence thinking about ALE and lifelong learning in the coming years. The report underscores the transformative potential of ALE and the need to reimagine its purposes beyond economic considerations by forging synergistic connections with other sectors:

Adult learning and education must look very different a generation from now. As our economies and societies change, adult education will need to extend far beyond lifelong learning for labour market purposes. Opportunities for career change and reskilling need to connect to a broader reform of all education systems that emphasizes the creation of multiple, flexible pathways. Like education in all domains, rather than being reactive or adaptive (whether to change in labour markets, technology, or the environment), adult education needs to be reconceptualized around learning that is truly transformative (UNESCO 2021b , pp. 114–115).

The Reimagining our futures together report advocates for a multidimensional view of ALE – empowering, critical and transformative – which takes responsibility for shaping a just, peaceful and sustainable world:

Adult learning and education play multiple roles. It helps people find their way through a range of problems and increases competencies and agency. It enables people to take more responsibility for their future. Furthermore, it helps adults understand and critique changing paradigms and power relationships and take steps towards shaping a just and sustainable world. A futures orientation should define adult education, as much as education at all moments, as an education entangled with life. Adults are responsible for the world in which they live as well as the world of the future. Responsibility to the future cannot be simply passed on to the next generations. A shared ethic of intergenerational solidarity is needed (UNESCO 2021b , p. 115).

Interestingly, these quotations harken back to the broad-based, life-altering FEP agenda initiated many decades ago. They also recognise the distinctive challenges of our times, which again require holistic approaches and energetic thinking that transcend interagency politics and turf wars.

In preparing the Reimagining our futures together report (UNESCO 2021b ), UNESCO commissioned dozens of background papers, a handful of which focus on the future of ALE and lifelong learning. For example, in “Knowledge production, access and governance: A song from the South”, Catherine Odora Hoppers ( 2020 ) argues for expanding our understanding of education itself, from a narrow view of school-based learning, to one that embraces non-formal adult education, and then expands holistically into lifelong learning. Others note the challenges facing the adult education community if it is to meet a surging and diversified demand for ALE in the coming years. While noting the importance of contextualising solutions, the International Council for Adult Education (ICAE), an international civil society organisation, calls for:

strengthening institutional structures (like community learning centres for delivering ALE) and securing the role of ALE staff,

improving in-service and pre-service education, further education, training, capacity building and employment conditions of adult educators, [and]

developing appropriate content/curricula and modes of delivery adequate for adult learners, based on research results (ICAE 2020 , p. 13).

Africa: education as a source of restoration

Although many current crises are global in scope, they impact world regions differently and often unequally. Here, we briefly focus on Africa, given its centrality in international education development discourse as well as its potential to be a thought leader in reimagining education and lifelong learning going forward.

In the African context, relationships with, and to, nature, human agency, and human solidarity underpin African knowledge systems. African communities create and derive their existence from them. Relationships between people hold pride of place – best explained by the concept of ubuntu (Oviawe 2016 ). It does not seek to conquer or debilitate nature as a first impulse.

Thus, from an African perspective, education must first and foremost facilitate restoration. This means employing education and social literacies (Street 1995 ) to build pathways of return for the empowerment of African children and adults – in other words, to foster a sense of coming home. There need to be concerted efforts to restore human agency among Africans. From an epistemological point of view, the objective is to enable African civilisations to be recovered, breathing life to Indigenous forms of knowledge and restoring their place in the livelihood of communities so that they can, without coercion, determine the nature and pace of the development they seek going forward (Ocitti 1994 ). Thus, the right to adult literacy and the achievement of universal literacy are not only important for personal fulfilment, enhanced skill levels and social development, but also as a source for restoration and renewal.

It is estimated that about sixty per cent of Africans live in rural areas (UN 2018 ). They use their bequeathed rural assets as the basis for establishing a livelihood, securing their existence, contributing to different modes of development, subsidising state social welfare, and caring for the old and the young. An appropriate strategy for adult education is to frame sustainable development around what people currently have and, from this vantage point, re-link lifelong learning with humanity from the ground up. This means systematising and integrating diverse social and non-Western knowledge systems into mainstream processes.

Education systems in Africa continue to be deeply rooted in Western values and cultural frames as a vestige of colonialism. They also narrowly attend to the supply side of the equation, obsessively focused on instrumental policies to increase attendance and school completion rates. Education needs to anticipate a liberation of the mainstream from its narrow, parochial, and eschewed understanding of what is “universal”. To do so would mean recognising the dissonance in the application of dialogue in the Freirean sense of “naming the world” (Freire 1970 ), and the under-articulation of strategies that enable the effective participation of African knowledge systems in this naming.

Which “life skills” should be realised through lifelong learning?

For education and lifelong learning to truly become authentic pathways to sustainable development, empowerment and restoration, they must go beyond the articulation of new visions for the future, and deal sensitively with the consequences of inherited practices. Continued focus on socialising children and adults into dominant cultural milieus or on adapting the provision of formal and non-formal education to existing economic structures to ease the school-to-work transition contributes little to a new vision of lifelong learning.

One potential point of departure is recasting the value of different “life skills” and competencies that adults acquire through ALE in consideration of an alternative set of societal purposes. At the World Education Forum in Dakar in May 2000, countries committed themselves to a broad “life skills” goal: to ensure “that the learning needs of all young people and adults are met through equitable access to appropriate learning and life skills programmes” (EFA Goal 3; WEF 2000 , p. 16). Although various international organisations and civil society groups held different understandings of this goal, some consensus did eventually emerge: (1) that “equitable access to appropriate learning” included all modes of delivery, i.e. formal and nonformal education, vocational training, distance education, on-the-job training and self-learning; and (2) that life skills programmes could be characterised by the major types of skills they conveyed – namely, basic skills (e.g. literacy, numeracy), practical/contextual skills (e.g. health promotion, HIV prevention, livelihood and income-generation skills) and psychosocial skills (e.g. problem-solving, decision-making, critical thinking, interpersonal, communication, negotiating and collaboration/teamwork skills). Although EFA Goal 3 was, unsurprisingly, one of the most difficult goals to measure or monitor, it did embrace a broad view of the learning needs of younger and older learners (UNESCO 2014a , 2015a ).

The post-2015 global education policy agenda (SDG 4) contains more specific formulations of adult learning needs, albeit in separate targets (WEF 2016 ). SDG Target 4.3 focuses on equitable access to affordable and quality TVET and higher education; SDG Target 4.4 on relevant skills for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship; SDG Target 4.5 on eliminating discrimination and disparities in all forms of education; SDG Target 4.6 on youth and adult literacy and numeracy; and SDG Target 4.7 on knowledge and skills needed for sustainable development through education for sustainability and global citizenship. Footnote 11

While the SDG Targets invoke a wide array of skills and competencies, they mainly refer to economic productivity, social equality and sustainable development. But which transversal skills and competencies are needed to grapple with the imperatives of peaceful co-existence, social solidarity, global awareness and human dignity, which appear to be in short supply? For example, understanding human dignity and working towards its revitalisation presupposes an awareness of humiliation, deprivation, cognitive justice and other forms of disenfranchisement. In today’s world, commitments to democratic institutions and processes and securing human rights, taken on their own, are insufficient to ensure human dignity. While SDG Target 4.7 offers a handle for ALE programmes to diversify the competencies they seek to engender, most efforts around this target are exclusively focused on school-based learning. Can lifelong learning opportunities be designed to address emergent societal and global challenges? As we have seen, the stakes today are much higher than in the past.

Future educational trajectories, based on lifelong learning for all, must look with the eyes of a chameleon, taking a full 360-degree view, to embrace humanity where it stands and build upon what people have, instead of reinforcing the deficit-oriented and toxic formula that has been endemic to borrowed educational practices for so long. Lifelong learning is about learning throughout life in formal, non-formal and informal settings. And yet, more often than not, informal and non-formal approaches to learning are undervalued, mentioned in passing, and largely invisible. Why do so many advocates of lifelong learning turn to the safely tarmacked highways of formal learning? Non-formal and informal learning may require different measurement tools, but they are ubiquitous in people’s lives and deserve our full attention.

Shifting from education with a small “e” to Education with a capital “E”

For many, the term “lifelong learning” has a wider and a narrower meaning. In its wider meaning, lifelong learning refers to all forms of formal, non-formal and informal learning – irrespective of whether it is planned or unplanned, intentional or unintentional – involving children, youth and adults. In a narrower sense, lifelong learning refers to planned learning activities , including those both inside and outside of education and community institutions (e.g. workplace learning and private-sector provision) for specific populations (e.g. toddlers, adults). In the first sense, no one is a non-participant; everyone learns, even if the learning is unconscious and unintentional. In the second sense, there are some adults for whom it can be claimed that they “have done no ‘learning’ since leaving school”. Thus, “lifelong learning” policies seek to ensure that more and more adults participate in learning opportunities over the course of their lives (Rogers 2016 ).

Lifelong learning, in principle, does not discriminate between culturally distinct traditions in education. As Odora Hoppers ( 2020 ) argues, education with a small “e” is tied up with Eurocentrism, and a long tradition of school-centric and discipline-based ways of thinking that create artificial boundaries and barriers, leading to rigid outcomes, international league tables and limited interest in interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary learning. By contrast, Education with a capital “E” refers to lifelong relearning, and unlearning, combining formal, informal and non-formal insights and wisdom from many cultures. It embraces traditional knowledge, Indigenous knowledge, civilisational knowledge systems from all parts of the world (Odora Hoppers 2020 ).

For Education with a capital “E” to take root and blossom, a dialogic context must be created in which the democratic imagination and conversation are constructed between different knowledge systems and across diverse disciplines and sectors (UNESCO 2000b ). Such a context would raise issues about governance, science and education and address questions of global ethics, learning and plurality (Bindé 2001 , 2004 ). This could result in a new governance model of local–global interfaces, focusing on issues of restoration, sustainability and increased human consciousness as well as self-cultivation and self-improvement. Such new governance should be underpinned by a lived ethics, instead of the conceptual compliance-driven ethics that are commonplace today. Current frameworks of governance fetishise information over knowledge as an ecology. This must change. The epistemics of governance of education with a capital “E” must be worked out in terms of a new vocabulary to replace the present model of governance which is puritanical and quite un-nuanced about the suffering it creates (Odora Hoppers 2018 ).

To facilitate the shift to “Education”, emergent knowledge systems need to learn from and validate one another in future pursuits. Indigenous ways of living and knowing open up learners to the crucial distinction between “frugal subsistence” and “poverty” (Gupta 1999 ). Education should produce leaders who look beyond the “classroom” and its world of objects, categories and restrictive logic and foster a wider understanding of science, history, technologies and cultural sciences as practised by other knowledge systems.

Lastly, lifelong learning should seek to create “ethical spaces” that allow individuals from different knowledge traditions to engage in interactions based on dialogue, reciprocity, respect, courtesy, valorisation and recognition of the “Other”. Such spaces open windows of opportunity for critical conversations about race, gender, class, freedom and community. It is in and through ethical spaces that substantial, sustained and deeper understandings between cultures and peoples can emerge. When two sorts of entities with two sorts of intentions meet in an abstract theoretical location in the thought world, it becomes a space where different cultures, worldviews, knowledge systems and jurisdictions agree to interact. Non-Indigenous and Indigenous communities can come and participate, debate, discuss and finally have meaningful dialogue. Instead of maintaining unequal relations in terms of a hierarchical order, a space is created in which both entities experience vulnerability – in other words, they meet on equal terms, naked, without agendas or titles. Ethical spaces create a level playing field with opportunities for dialogue between entities and for the possible crossing of existing cultural borders (Ermine 2007 ).

Can lifelong learning reimagine itself as the purveyor of emancipatory platforms (Biesta 2012 )? Can it enable individuals to engage with distinctive knowledge traditions and with decolonised, alternate forms of knowing of, and being in, the world? If so, then it will help to address the crises of our times.

The articles featured in this special issue

The six articles we present in this special issue reflect opportunities and gaps in ALE and lifelong learning in the broad SDG agenda and how these might be bridged to bring forth more meaningful social transformation as discussed thus far. This compilation therefore highlights a range of strategies for creating abundant, fair, accessible, diverse and monitorable pathways and equivalencies both within and between formal, non-formal and informal learning. It also addresses the need to better align the links between ALE policy, governance, financing, quality and participation, the five key areas of the Belém Framework for Action (BFA; UIL 2010 ), and the five ALE-related Targets of SDG 4 (WEF 2016 ). Overall, this special issue aims to rethink and re-position ALE, the core construct of the CONFINTEA process of reviewing and improving, within the conception of lifelong learning in the SDGs as a key lever for development and addressing global challenges touched on earlier. In this respect it also complements forthcoming reports and papers being prepared for the CONFINTEA VII conference, including the Fifth Global Report on Adult Learning and Education ( GRALE 5 ) which will focus on education for active citizenship (UIL 2022 ).

This special issue aims to bring the agendas of CONFINTEA and the SDGs closer together. Much of the success of each respective agenda depends on mobilising funding to implement policy commitments. This is especially true for ALE, an education policy arena in which financing is far more precarious.

We begin with an article by David Archer , who was a member of the BFA Drafting Group in 2009, representing civil society through the International Council for Adult Education (ICAE), and is a key expert on education financing within ActionAid. His article, “Avoiding pitfalls in the next International Conference on Adult Education (CONFINTEA): Lessons on financing adult education from Belém”, is an interesting first-hand account from someone who was deeply engaged in the discussion and drafting ideas of how big the education part in a country’s overall national budget should be, and what the share of ALE of the national education budget should be moving towards by asking for concrete figures and percentages. He specifically points to the interventions of delegates who argued for no figure or percentage to be put into the BFA, and that they unfortunately succeeded on that point. This may have contributed to the reality of today where each GRALE points to the low level of ALE financing in most countries. Archer shares those insights in detail and offers a number of potential solutions, looking beyond education into progressive ways of tax reform or debt service suspension. It is to be hoped that key lessons have been learned and the outcome document of CONFINTEA VII, the Marrakech Framework for Action (MFA), will be more explicit in terms of financing goals. The currently available draft for the online MFA consultation formulates financing as follows:

We are determined to increase public spending on education in accordance with country contexts to meet the international benchmarks of allocating 4–6% of GDP and/or 15–20% of total public expenditure to education, including at least 4% for ALE (CONFINTEA VII online consultation, accessed 10 April 2022).

The second article we present, “Financing adult learning and education (ALE) now and in future” was written by Idowu Biao , professor of lifelong learning at the University of Abomey-Calavi in Benin. He throws the net wider in helping to understand why ALE is grossly underfunded while the education community is pushing lifelong learning for all as stipulated in SDG 4. Biao starts off by talking about ALE as a human right, arguing that there is no good reason why ALE is not funded like other parts of a country’s education system. He identifies four factors which he deems responsible for this current state of affairs: (1) the world’s obsession with the provision of school education; (2) the lack of adequate instruments to work out ALE’s returns on investment; (3) the delusion that employers will ultimately supply ALE, a hope which disregards the fact that a large proportion of youth and adults are not in formal employment; and (4) the assumption that an expansion of formal schooling will eventually lead to the establishment of literate societies free of intergenerational crises. Since ALE is generally framed as a broad literacy education project, Biao undertakes a review of literacy education costing. He continues by looking into several funding models in which individuals, communities, governments, or employers play a key role at the national level, and also considers the use of international development aid or the Official Development Assistance (ODA) model. Both are needed: the increase in domestic funding for ALE as well as new perspectives of funding ALE within lifelong learning for global agencies, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, as well as large NGOs, whose ALE funding is minimal.

Adult literacy

Adult literacy is also of particular interest to Ulrike Hanemann and Clinton Robinson , both of whom are influential in this area through their work for UNESCO and in the field. In “Rethinking literacy from a lifelong learning perspective in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals and the International Conference on Adult Education”, they raise concerns about the challenges of connecting literacy to the principle of lifelong learning, focusing in particular on SDG Target 4.6, which is dedicated to adult literacy. The authors use a holistic framework labelled “lifelong literacy” not only to strengthen global approaches to adult literacy – which they consider insufficiently prioritised in recent years – but also to inform policy and programme approaches that better link country, institution-based, community, family and individual learning. This integration, they argue, is necessary when considering literacy as a socially situated practice. Hanemann and Robinson also provide analyses of literacy policies, strategies and programmes that have been successful in adopting a lifelong learning approach, drawing out some important lessons on how this can be achieved. In particular, they argue, more attention needs to be paid to the demand side of a literate environment and to motivation, enabling continuity of learning by making literacy part of people’s broader learning purposes. The authors make a number of points that support the framing of adult literacy in this way, noting that learning begets learning and therefore motivation is highly implicit in this process if learning opportunities actively relate to the realities, aspirations and learning journeys of adults in different social contexts (i.e. matching learners’ language needs and local forms of knowledge). As such, education systems must make their inclusion more flexible and permeable through the creation of responsive infrastructure, also, for example, by broadening national qualifications frameworks to include literacy and basic skills gained in non-formal and informal learning environments, raising the value of recognition, validation and accreditation (RVA) of these learning outcomes as a basis of learning continuity for all. To contribute to the ongoing discussion on reframing literacy from a lifelong learning perspective in the context of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the potential development of a new “framework for action” during CONFINTEA VII, this article offers three fundamental considerations that should inform policy and strategic planning regarding conceptual orientation, programmatic responses and institutional connections.

Participation

After considering financing and literacy, we now turn to participation. GRALE 4, Entitled Leave no one behind: participation, equity and inclusion (UIL 2019 ) makes the claim in its concluding chapter that the global monitoring architecture in place is not adequately equipped to fulfil its purpose, and that country-level collection of ALE data is far from sufficient. Who participates in ALE, and who does not, in what forms and at what levels is hardly known. Aggregated data reflecting age and gender, access and inclusion, demand and supply, digital or institutionalised provision are limited.

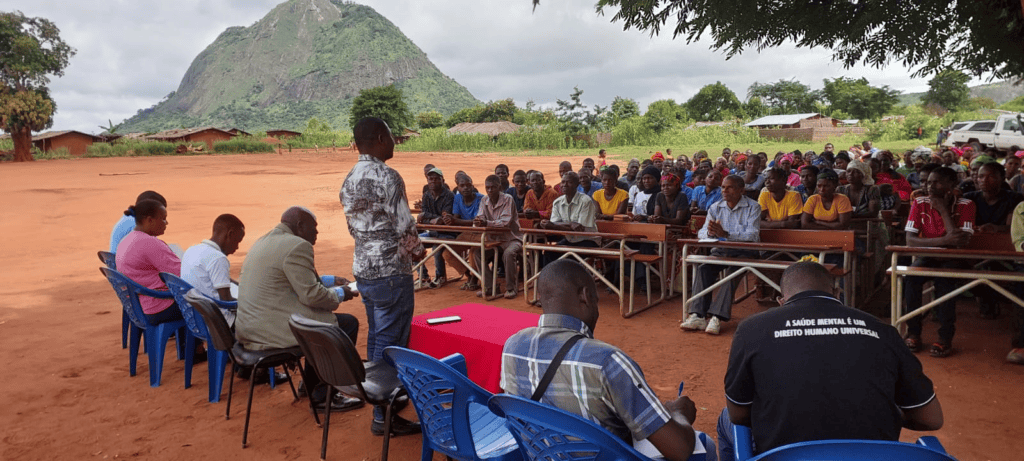

The fourth article we present in this special issue is “Community learning centres (CLCs) for adult learning and education (ALE): Development in and by communities”, written by Sonja Belete, Chris Duke, Heribert Hinzen, Angela Owusu-Boampong and Khấu Hữu Phước. Aiming to get a clearer understanding of participation in community-based ALE, often conducted in community learning centres (CLCs), their article shows that institutionalised forms of ALE are found in most parts of the world. They are embedded in different traditions, with stronger roots in Europe and Asia, and as spaces offering opportunities for literacy and skills training, health and citizenship promotion, general, liberal and vocational education, in line with a fuller recognition of the meaning of lifelong learning, and in the context of local communities. They operate according to a multitude of modes, methods and materials, and often form the basis for even more informal and participatory learning, like study circles and community groups. The authors review relevant literature and identify recent studies and experiences with a particular focus on the Asia-Pacific and Africa regions, but also consider insights related to interventions at the global level. Findings point to low levels of participation of adults in general, and more specifically of vulnerable and excluded groups struggling to overcome various barriers. The authors’ discussion is guided by the question: What conditions are conducive to having more and better ALE for lifelong learning – and which roles can CLCs and other community-based ALE institutions play? They take into consideration that while most learners in CLCs are adults, sometimes children and youth also participate. As institutions, CLCs provide opportunities for engagement in different thematic areas through courses and other activities. To strengthen policy support for good practice, convincing examples of successful methods and related policies, legislation and financing are needed, along with a much deeper shared grasp of the full meaning of lifelong learning (throughout life, in depth, and including a wide range of locations and modes of learning). This discussion is timely – the authors argue that CLCs need to be given more attention in international commitments such as those made in the context of the series of CONFINTEAs and the UN’s 17 SDGs. Indeed, CLCs are up for discussion in a thematic workshop during CONFINTEA VII, and also featured in a recommendation in the draft MFA – both of which will take CLCs deeper into the proceedings and hopefully outcomes.

Two articles in this special issue focus on how monitoring ALE against international commitments can be improved in different ways, both to enhance scope, collaboration, reliability and usability of data findings and conclusions, but also to provide evidence for foundational arguments of ALE benefits, spill-over effects and financing needs. In the first of these two contributions, Ellen Boeren and Kjell Rubenson , both academics who have been involved in several GRALE reports, take a close look at its utility as a monitoring mechanism. In “The Global Report on Adult Learning and Education (GRALE) : Strengths, weaknesses and future directions”, they use an evaluative framework developed by Pär Mårtensson et al. ( 2016 ) to investigate to what extent the GRALE approach to monitoring and reporting on ALE so far has been (1) credible (e.g. based on rigorous research methodologies and methods); (2) contributory (e.g. relevant and applicable to practice, generalisable); (3) communicable (e.g. accessible, understandable and readable in terms of report structure); and (4) conforming (e.g. with ethical standards). The authors arrive at several critical observations, such as concerns over GRALE data quality, given that the mechanism only relies on one response per country rather than triangulating information sources for a more impartial view of ALE activities on the ground. Another is on how countries with dramatically different ALE contexts are analysed in groups (by region, income level), potentially making it difficult for policymakers to distil specific learnings for their national settings and also challenging to see particular gaps or issues, aside from those reported through open-ended questions. While GRALE provides a unique dataset from regularly (at roughly three-year intervals) tracking progress on political commitments to the BFA and RALE across a wide swathe of UNESCO Member States, it is unclear what direct impact its insights and findings have had on ALE policy, strategy and programme developments over the past 13 years. This creates a nebulous space for supposition about impact, rather than having evidence of impact in various settings that underwrites and ultimately strengthens GRALE ’s concrete value in shaping ALE directions and driving social norms. To get to the bottom of this question, Boeren and Rubenson suggest an in-depth impact evaluation to be conducted during the next CONFINTEA cycle, in addition to GRALE focusing more on tracking not only progress but also impacts from meeting ALE commitments and linking this query to the SDGs.

The second article on monitoring, “Bringing together monitoring approaches to track progress on adult learning and education across main international policy tools”, was written by Ashley Stepanek Lockhart , who has also been involved in GRALE. She explores ways of leveraging the report and monitoring strategies of ALE-related SDG 4 Targets (4.1–4.7) and “means of implementation” (4.a–4.c) to increase coverage and efficiency of these processes by combining efforts from within different parts of UNESCO, while also maintaining their separate added value. This is important since, at least in theory, different UNESCO institutes and departments are talking to the same countries about ALE monitoring even if the approach, timeline and type of information collected may differ. While there are content overlaps, Stepanek Lockhart argues that aligning GRALE and monitoring strategies of ALE-related SDG 4 Targets/means of implementation could help to backstop information that each requires for sharper or more comprehensive analysis, whether to fill gaps on missing data or to verify data in hand, with the aim of increasing robustness and reliability of resulting reports. She provides examples of where data may be missing in one monitoring approach and how a question could be added to another to make up the difference, and vice versa (e.g. adding a question to the GRALE survey to build on limited information about SDG Indicator 4.3.1 on participation in informal and non-formal education in training in the last 12 months, by sex; conversely, sharing data with GRALE on SDG Indicator 4.4.1 on youth and adults with ICT skills, by skill type, to enhance analysis). Moreover, demonstrating that there are significant gaps between relevant targets, indicators and data sources, the author argues that mutually beneficial activities and information sharing could contribute to monitoring the fuller intent of SDG 4 Targets concerning ALE, which may overlap with commitments made in the BFA and in the 2015 Recommendation for Adult Learning and Education (RALE; UNESCO & UIL 2016 ). Among other recommendations, the author highlights the need for GRALE to enlarge its focus on tracking ALE teacher development, since – while SDG Target/means of implementation 4.c focuses on increasing the supply of qualified teachers generally, and especially in economically developing countries – in practice they are otherwise not being monitored.

This introductory essay and the articles in this special issue constitute a clarion call for meeting the unprecedented challenges of our times by reimagining the roles of adult education and lifelong learning for all. Collectively, we consider abstract conceptualisations as well as concrete experiences. We draw on the historical record as well as on insights from adjacent fields of knowledge. From an African perspective, we reconsider the vast education project – formal, non-formal and informal – through a different lens. It prioritises education that serves as a platform for bridging diverse worldviews, cultivating encounters with the Other, and recognising, publicly and without duress, the co-existence of multiple forms of knowledge. Education that transforms must be holistic. Adult education that transforms must acknowledge different knowledge systems, including Indigenous ways of knowing and being, which have been neglected and devalorised. Working towards these ideals is among the deepest challenges for the ALE movement going forward.

Recommendations for the future of adult learning and education

On the relevance, contextualisation and interactive potential of ale.

Adult learning and education should be firmly embedded in local contexts of culture and language, and derive its purposes, major content areas and pedagogies from local communities regardless of location (i.e. rural, urban, mixed landscapes).

ALE programmes should encourage learners to encounter different knowledge and historical traditions and to engage in interactions based on dialogue, reciprocity, courtesy and mutual respect.

Indigenous knowledge and local learning practices are important for people to navigate their specific contexts and aspirations. Creating physical, emotional and intellectual spaces in support of these processes should be encouraged.

On institutionalising, professionalising and governing ALE

Countries should formally acknowledge that the right to education for all includes the right to adult education for all.

ALE systems should be an acknowledged sub-sector of a country’s education system (like primary, secondary and higher education) to more fully reflect and act on long-term political and financial commitments in this field.

Steps should be taken to enhance the provision of, and participation in, ALE within clearly demarcated spaces supported by an explicit infrastructure, one that facilitates local engagement. Community learning centres, for example, and other community-based institutions can be developed as cornerstones to local infrastructure.

The governance of a country’s education system should be redesigned to take full account of all sub-sectors from a lifelong learning perspective, including formal and non-formal education and informal learning. Policy decisions should draw on documented evidence of the flexible and permeable pathways adults utilise in their lives, which can be recognised and broadened to support a variety of learning journeys. Mechanisms and support structures should prioritise adults living and working in the informal and agricultural sectors, ensuring that no one is left behind.

The institutionalisation and professionalisation of ALE are important for organisational development as well as capacity building, training and research to enhance quality. Drawing on evidence of best practices, higher education institutions should play a supportive role in preparing ALE professionals, who serve in leadership, management, administration, teaching and research capacities in the ALE sub-sector. The research functions of universities and specialised institutions should be mobilised to improve all aspects of ALE systems, especially in terms of quality, diversity and equity through a lifelong learning approach.

On financing

ALE financing should be fully embedded and concretised in policy and legislation and move beyond well-intentioned political commitments. Without an urgent increase in financing, the potential role of ALE to respond to the major crises of our time will go under/unrealised.

All countries should widen the tax base by ending harmful tax incentives and preventing tax evasion and use these funds to increase the share of existing government budgets allocated to ALE.

Many countries should increase their tax to GDP ratios – say, by five percentage points by 2030 – to raise more financial resources for all forms of lifelong learning: formal, non-formal and informal.

Increased budget allocations to ALE should prioritise excluded groups, improve equity of provision and increase the scrutiny of spending in practice to make sure ALE resources reach disadvantaged communities.

International donors should support partner countries’ efforts to increase ALE funding levels by meeting their commitment to 0.7% of Gross National Income and thereby ensure equitable resource allocation to underserved communities.

On measuring, reporting and monitoring

Countries – with the support of international partners and agencies – should make concerted efforts to expand the collection and reporting of ALE-related information and statistics based on national census data, other national surveys and innovative indicators, thereby contributing to improvements in national reporting and global reviews of ALE and, ultimately, improved implementation.

Steps should be taken to upgrade the reliability and validity of information about the participation in and provision of ALE in all its forms and modalities, regardless of who the provider is (e.g. government agencies, or private-sector, civil-society, faith-based or distance learning organisations).

Information on other aspects of ALE (e.g. ALE programme descriptions, learner characteristics, programme quality, funding, educators and facilitators, outcomes, programme effectiveness and efficiency) should also be compiled. Such information should be utilised for improved policy deliberation, policy interventions, advocacy, the institutionalisation and professionalisation of ALE, as well as for evaluation research and innovation in the field. ALE data should become an integral and transparent part of overall education statistics and monitoring systems, and should help create a more robust evidence base for GRALE monitoring.

Countries should measure adult literacy based on a continuum of literacy levels (not dichotomised into literate and illiterate categories) and define clear measurable ALE targets within lifelong learning. Approaches to measuring literacy as a continuum at scale must be explored to ensure the quality and coverage of interventions in different places without becoming rigid or too prescriptive.

The Global Report on Adult Learning Education ( GRALE ) should be strengthened, and its independence enhanced. GRALE reports should be externally evaluated by an independent entity to determine its impact and fitness for purpose. The terms of reference for the evaluation should be developed by an independent body of diverse stakeholders. This evaluation could be the launch pad for a global research programme into ALE.

Greater synergies should be realised between GRALE and SDG 4 measurement and monitoring efforts, positioning al ALE as an integral part of the overall effort to support transformative lifelong learning and development.

The fact that the major parties to the conflict included the most educated and literate populations in the world did not detract from the abiding faith of post-WWII leaders that the spread of education and literacy would promote international understanding and peaceful relations.

These quotes are taken from the Memorandum on the education programme of UNESCO, Paper No. 1, prepared by the Education Staff of the Preparatory Commission, 13 May 1946. UNESCO.Prep.Com./Educ.Com., UNESCO Archives.

See also Educación Fundamental: Ideario, principios, orientaciones methodológicas (CREFAL 1952 ).

Internally, UNESCO delegates debated the use of the term “fundamental” in contrast to “elementary” or “primary”. Many preferred the former over the others since, for example, it “contained the more recent and much broader concept of education” or because it “conveyed more clearly the conception of basic education which was the right of everyone” or that it was “a new and modern concept … particularly well adapted to countries where adult education became imperative for those persons who had not enjoyed the opportunities of grade-school instruction” (UNESCO 2000a , p. 98). In explaining the choice of terms, Kuo Yu-Shou, Senior Counsellor for Education, claimed that the term “fundamental education” could include education for adults and children. Most importantly, this term suggested that teachers could accept the differences among individuals, while the term “mass education” implied teachers should treat everyone in the same manner (Watras 2010 , p. 221).

This was an insight from the aftermath of the massively disruptive First World War. In 1919, Imperial Germany had moved with deliberate speed towards establishing a democratic polity. The new Constitution of the Weimar Republic contained a special clause requesting local, regional and national authorities to support adult education, including the folk high schools. Despite further disruption (and misappropriation) during the Second World War, it was this constitutional anchoring of ALE in policy, legislation and financing which enabled the German adult education system to flourish for more than a century. The parallel with the evolution of the international adult education movement is striking (Hinzen and Meilhammer 2022 ).

As of the end of 2019, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), a global authority on the status of the natural world, included assessments for 112,432 species (a small proportion of all species), of which 30,178 (or 27%) have been found to be threatened with extinction (IUCN 2020 ). The IUCN’s Red list of threatened species currently estimates that 41% of amphibians, 26% of mammals, 13% of birds and 21% of reptiles are threatened with extinction (IUCN 2022 ).

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports that human activities are estimated to have caused approximately 1.0°C of global warming above pre-industrial levels (IPCC 2022 ). If global warming continues to increase at the current rate, it is likely to reach 1.5°C between 2030 and 2052. Warming from human-caused emissions from the pre-industrial period to the present will persist for centuries to millennia and will continue to cause further long-term changes in the climate system, such as arctic cap melting, rising sea levels, extreme weather events, many with adverse impacts on natural, animal and human species.

The UN Convention to Combat Desertification estimates that over one-third of the world’s population currently lives in water-scarce regions (UNCCD 2022 ). By 2030, up to 700 million people could be displaced by drought. “By 2050, over half of the world’s population and half of global grain production will be exposed to severe water scarcity” (ibid., p. 41).

Lifelong learning comprises all learning activities, from cradle to retirement and beyond, undertaken with the aim of improving knowledge, skills and competencies, within personal, civic, social and employment-related perspectives (UIL 2016 ). In much of the world, individuals are engaged in a multiplicity of learning activities – formal, non-formal and informal – throughout their lives, following diverse – and often discontinuous – learning pathways. While it may be difficult to capture empirically how learners of various ages traverse different learning entry and re-entry points, the fluidity of learning profiles has increasingly become the norm.

For Japan, see Centre for Public Impact ( 2018 ).