- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Justify Your Methods in a Thesis or Dissertation

4-minute read

- 1st May 2023

Writing a thesis or dissertation is hard work. You’ve devoted countless hours to your research, and you want your results to be taken seriously. But how does your professor or evaluating committee know that they can trust your results? You convince them by justifying your research methods.

What Does Justifying Your Methods Mean?

In simple terms, your methods are the tools you use to obtain your data, and the justification (which is also called the methodology ) is the analysis of those tools. In your justification, your goal is to demonstrate that your research is both rigorously conducted and replicable so your audience recognizes that your results are legitimate.

The formatting and structure of your justification will depend on your field of study and your institution’s requirements, but below, we’ve provided questions to ask yourself as you outline your justification.

Why Did You Choose Your Method of Gathering Data?

Does your study rely on quantitative data, qualitative data, or both? Certain types of data work better for certain studies. How did you choose to gather that data? Evaluate your approach to collecting data in light of your research question. Did you consider any alternative approaches? If so, why did you decide not to use them? Highlight the pros and cons of various possible methods if necessary. Research results aren’t valid unless the data are valid, so you have to convince your reader that they are.

How Did You Evaluate Your Data?

Collecting your data was only the first part of your study. Once you had them, how did you use them? Do your results involve cross-referencing? If so, how was this accomplished? Which statistical analyses did you run, and why did you choose them? Are they common in your field? How did you make sure your data were statistically significant ? Is your effect size small, medium, or large? Numbers don’t always lend themselves to an obvious outcome. Here, you want to provide a clear link between the Methods and Results sections of your paper.

Did You Use Any Unconventional Approaches in Your Study?

Most fields have standard approaches to the research they use, but these approaches don’t work for every project. Did you use methods that other fields normally use, or did you need to come up with a different way of obtaining your data? Your reader will look at unconventional approaches with a more critical eye. Acknowledge the limitations of your method, but explain why the strengths of the method outweigh those limitations.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

What Relevant Sources Can You Cite?

You can strengthen your justification by referencing existing research in your field. Citing these references can demonstrate that you’ve followed established practices for your type of research. Or you can discuss how you decided on your approach by evaluating other studies. Highlight the use of established techniques, tools, and measurements in your study. If you used an unconventional approach, justify it by providing evidence of a gap in the existing literature.

Two Final Tips:

● When you’re writing your justification, write for your audience. Your purpose here is to provide more than a technical list of details and procedures. This section should focus more on the why and less on the how .

● Consider your methodology as you’re conducting your research. Take thorough notes as you work to make sure you capture all the necessary details correctly. Eliminating any possible confusion or ambiguity will go a long way toward helping your justification.

In Conclusion:

Your goal in writing your justification is to explain not only the decisions you made but also the reasoning behind those decisions. It should be overwhelmingly clear to your audience that your study used the best possible methods to answer your research question. Properly justifying your methods will let your audience know that your research was effective and its results are valid.

Want more writing tips? Check out Proofed’s Writing Tips and Academic Writing Tips blogs. And once you’ve written your thesis or dissertation, consider sending it to us. Our editors will be happy to check your grammar, spelling, and punctuation to make sure your document is the best it can be. Check out our services for free .

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

5-minute read

Six Product Description Generator Tools for Your Product Copy

Introduction If you’re involved with ecommerce, you’re likely familiar with the often painstaking process of...

3-minute read

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write the Rationale of the Study in Research (Examples)

What is the Rationale of the Study?

The rationale of the study is the justification for taking on a given study. It explains the reason the study was conducted or should be conducted. This means the study rationale should explain to the reader or examiner why the study is/was necessary. It is also sometimes called the “purpose” or “justification” of a study. While this is not difficult to grasp in itself, you might wonder how the rationale of the study is different from your research question or from the statement of the problem of your study, and how it fits into the rest of your thesis or research paper.

The rationale of the study links the background of the study to your specific research question and justifies the need for the latter on the basis of the former. In brief, you first provide and discuss existing data on the topic, and then you tell the reader, based on the background evidence you just presented, where you identified gaps or issues and why you think it is important to address those. The problem statement, lastly, is the formulation of the specific research question you choose to investigate, following logically from your rationale, and the approach you are planning to use to do that.

Table of Contents:

How to write a rationale for a research paper , how do you justify the need for a research study.

- Study Rationale Example: Where Does It Go In Your Paper?

The basis for writing a research rationale is preliminary data or a clear description of an observation. If you are doing basic/theoretical research, then a literature review will help you identify gaps in current knowledge. In applied/practical research, you base your rationale on an existing issue with a certain process (e.g., vaccine proof registration) or practice (e.g., patient treatment) that is well documented and needs to be addressed. By presenting the reader with earlier evidence or observations, you can (and have to) convince them that you are not just repeating what other people have already done or said and that your ideas are not coming out of thin air.

Once you have explained where you are coming from, you should justify the need for doing additional research–this is essentially the rationale of your study. Finally, when you have convinced the reader of the purpose of your work, you can end your introduction section with the statement of the problem of your research that contains clear aims and objectives and also briefly describes (and justifies) your methodological approach.

When is the Rationale for Research Written?

The author can present the study rationale both before and after the research is conducted.

- Before conducting research : The study rationale is a central component of the research proposal . It represents the plan of your work, constructed before the study is actually executed.

- Once research has been conducted : After the study is completed, the rationale is presented in a research article or PhD dissertation to explain why you focused on this specific research question. When writing the study rationale for this purpose, the author should link the rationale of the research to the aims and outcomes of the study.

What to Include in the Study Rationale

Although every study rationale is different and discusses different specific elements of a study’s method or approach, there are some elements that should be included to write a good rationale. Make sure to touch on the following:

- A summary of conclusions from your review of the relevant literature

- What is currently unknown (gaps in knowledge)

- Inconclusive or contested results from previous studies on the same or similar topic

- The necessity to improve or build on previous research, such as to improve methodology or utilize newer techniques and/or technologies

There are different types of limitations that you can use to justify the need for your study. In applied/practical research, the justification for investigating something is always that an existing process/practice has a problem or is not satisfactory. Let’s say, for example, that people in a certain country/city/community commonly complain about hospital care on weekends (not enough staff, not enough attention, no decisions being made), but you looked into it and realized that nobody ever investigated whether these perceived problems are actually based on objective shortages/non-availabilities of care or whether the lower numbers of patients who are treated during weekends are commensurate with the provided services.

In this case, “lack of data” is your justification for digging deeper into the problem. Or, if it is obvious that there is a shortage of staff and provided services on weekends, you could decide to investigate which of the usual procedures are skipped during weekends as a result and what the negative consequences are.

In basic/theoretical research, lack of knowledge is of course a common and accepted justification for additional research—but make sure that it is not your only motivation. “Nobody has ever done this” is only a convincing reason for a study if you explain to the reader why you think we should know more about this specific phenomenon. If there is earlier research but you think it has limitations, then those can usually be classified into “methodological”, “contextual”, and “conceptual” limitations. To identify such limitations, you can ask specific questions and let those questions guide you when you explain to the reader why your study was necessary:

Methodological limitations

- Did earlier studies try but failed to measure/identify a specific phenomenon?

- Was earlier research based on incorrect conceptualizations of variables?

- Were earlier studies based on questionable operationalizations of key concepts?

- Did earlier studies use questionable or inappropriate research designs?

Contextual limitations

- Have recent changes in the studied problem made previous studies irrelevant?

- Are you studying a new/particular context that previous findings do not apply to?

Conceptual limitations

- Do previous findings only make sense within a specific framework or ideology?

Study Rationale Examples

Let’s look at an example from one of our earlier articles on the statement of the problem to clarify how your rationale fits into your introduction section. This is a very short introduction for a practical research study on the challenges of online learning. Your introduction might be much longer (especially the context/background section), and this example does not contain any sources (which you will have to provide for all claims you make and all earlier studies you cite)—but please pay attention to how the background presentation , rationale, and problem statement blend into each other in a logical way so that the reader can follow and has no reason to question your motivation or the foundation of your research.

Background presentation

Since the beginning of the Covid pandemic, most educational institutions around the world have transitioned to a fully online study model, at least during peak times of infections and social distancing measures. This transition has not been easy and even two years into the pandemic, problems with online teaching and studying persist (reference needed) .

While the increasing gap between those with access to technology and equipment and those without access has been determined to be one of the main challenges (reference needed) , others claim that online learning offers more opportunities for many students by breaking down barriers of location and distance (reference needed) .

Rationale of the study

Since teachers and students cannot wait for circumstances to go back to normal, the measures that schools and universities have implemented during the last two years, their advantages and disadvantages, and the impact of those measures on students’ progress, satisfaction, and well-being need to be understood so that improvements can be made and demographics that have been left behind can receive the support they need as soon as possible.

Statement of the problem

To identify what changes in the learning environment were considered the most challenging and how those changes relate to a variety of student outcome measures, we conducted surveys and interviews among teachers and students at ten institutions of higher education in four different major cities, two in the US (New York and Chicago), one in South Korea (Seoul), and one in the UK (London). Responses were analyzed with a focus on different student demographics and how they might have been affected differently by the current situation.

How long is a study rationale?

In a research article bound for journal publication, your rationale should not be longer than a few sentences (no longer than one brief paragraph). A dissertation or thesis usually allows for a longer description; depending on the length and nature of your document, this could be up to a couple of paragraphs in length. A completely novel or unconventional approach might warrant a longer and more detailed justification than an approach that slightly deviates from well-established methods and approaches.

Consider Using Professional Academic Editing Services

Now that you know how to write the rationale of the study for a research proposal or paper, you should make use of our free AI grammar checker , Wordvice AI, or receive professional academic proofreading services from Wordvice, including research paper editing services and manuscript editing services to polish your submitted research documents.

You can also find many more articles, for example on writing the other parts of your research paper , on choosing a title , or on making sure you understand and adhere to the author instructions before you submit to a journal, on the Wordvice academic resources pages.

How to Write the Rationale for a Research Paper

- Research Process

- Peer Review

A research rationale answers the big SO WHAT? that every adviser, peer reviewer, and editor has in mind when they critique your work. A compelling research rationale increases the chances of your paper being published or your grant proposal being funded. In this article, we look at the purpose of a research rationale, its components and key characteristics, and how to create an effective research rationale.

Updated on September 19, 2022

The rationale for your research is the reason why you decided to conduct the study in the first place. The motivation for asking the question. The knowledge gap. This is often the most significant part of your publication. It justifies the study's purpose, novelty, and significance for science or society. It's a critical part of standard research articles as well as funding proposals.

Essentially, the research rationale answers the big SO WHAT? that every (good) adviser, peer reviewer, and editor has in mind when they critique your work.

A compelling research rationale increases the chances of your paper being published or your grant proposal being funded. In this article, we look at:

- the purpose of a research rationale

- its components and key characteristics

- how to create an effective research rationale

What is a research rationale?

Think of a research rationale as a set of reasons that explain why a study is necessary and important based on its background. It's also known as the justification of the study, rationale, or thesis statement.

Essentially, you want to convince your reader that you're not reciting what other people have already said and that your opinion hasn't appeared out of thin air. You've done the background reading and identified a knowledge gap that this rationale now explains.

A research rationale is usually written toward the end of the introduction. You'll see this section clearly in high-impact-factor international journals like Nature and Science. At the end of the introduction there's always a phrase that begins with something like, "here we show..." or "in this paper we show..." This text is part of a logical sequence of information, typically (but not necessarily) provided in this order:

Here's an example from a study by Cataldo et al. (2021) on the impact of social media on teenagers' lives.

Note how the research background, gap, rationale, and objectives logically blend into each other.

The authors chose to put the research aims before the rationale. This is not a problem though. They still achieve a logical sequence. This helps the reader follow their thinking and convinces them about their research's foundation.

Elements of a research rationale

We saw that the research rationale follows logically from the research background and literature review/observation and leads into your study's aims and objectives.

This might sound somewhat abstract. A helpful way to formulate a research rationale is to answer the question, “Why is this study necessary and important?”

Generally, that something has never been done before should not be your only motivation. Use it only If you can give the reader valid evidence why we should learn more about this specific phenomenon.

A well-written introduction covers three key elements:

- What's the background to the research?

- What has been done before (information relevant to this particular study, but NOT a literature review)?

- Research rationale

Now, let's see how you might answer the question.

1. This study complements scientific knowledge and understanding

Discuss the shortcomings of previous studies and explain how'll correct them. Your short review can identify:

- Methodological limitations . The methodology (research design, research approach or sampling) employed in previous works is somewhat flawed.

Example : Here , the authors claim that previous studies have failed to explore the role of apathy “as a predictor of functional decline in healthy older adults” (Burhan et al., 2021). At the same time, we know a lot about other age-related neuropsychiatric disorders, like depression.

Their study is necessary, then, “to increase our understanding of the cognitive, clinical, and neural correlates of apathy and deconstruct its underlying mechanisms.” (Burhan et al., 2021).

- Contextual limitations . External factors have changed and this has minimized or removed the relevance of previous research.

Example : You want to do an empirical study to evaluate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number of tourists visiting Sicily. Previous studies might have measured tourism determinants in Sicily, but they preceded COVID-19.

- Conceptual limitations . Previous studies are too bound to a specific ideology or a theoretical framework.

Example : The work of English novelist E. M. Forster has been extensively researched for its social, political, and aesthetic dimensions. After the 1990s, younger scholars wanted to read his novels as an example of gay fiction. They justified the need to do so based on previous studies' reliance on homophobic ideology.

This kind of rationale is most common in basic/theoretical research.

2. This study can help solve a specific problem

Here, you base your rationale on a process that has a problem or is not satisfactory.

For example, patients complain about low-quality hospital care on weekends (staff shortages, inadequate attention, etc.). No one has looked into this (there is a lack of data). So, you explore if the reported problems are true and what can be done to address them. This is a knowledge gap.

Or you set out to explore a specific practice. You might want to study the pros and cons of several entry strategies into the Japanese food market.

It's vital to explain the problem in detail and stress the practical benefits of its solution. In the first example, the practical implications are recommendations to improve healthcare provision.

In the second example, the impact of your research is to inform the decision-making of businesses wanting to enter the Japanese food market.

This kind of rationale is more common in applied/practical research.

3. You're the best person to conduct this study

It's a bonus if you can show that you're uniquely positioned to deliver this study, especially if you're writing a funding proposal .

For an anthropologist wanting to explore gender norms in Ethiopia, this could be that they speak Amharic (Ethiopia's official language) and have already lived in the country for a few years (ethnographic experience).

Or if you want to conduct an interdisciplinary research project, consider partnering up with collaborators whose expertise complements your own. Scientists from different fields might bring different skills and a fresh perspective or have access to the latest tech and equipment. Teaming up with reputable collaborators justifies the need for a study by increasing its credibility and likely impact.

When is the research rationale written?

You can write your research rationale before, or after, conducting the study.

In the first case, when you might have a new research idea, and you're applying for funding to implement it.

Or you're preparing a call for papers for a journal special issue or a conference. Here , for instance, the authors seek to collect studies on the impact of apathy on age-related neuropsychiatric disorders.

In the second case, you have completed the study and are writing a research paper for publication. Looking back, you explain why you did the study in question and how it worked out.

Although the research rationale is part of the introduction, it's best to write it at the end. Stand back from your study and look at it in the big picture. At this point, it's easier to convince your reader why your study was both necessary and important.

How long should a research rationale be?

The length of the research rationale is not fixed. Ideally, this will be determined by the guidelines (of your journal, sponsor etc.).

The prestigious journal Nature , for instance, calls for articles to be no more than 6 or 8 pages, depending on the content. The introduction should be around 200 words, and, as mentioned, two to three sentences serve as a brief account of the background and rationale of the study, and come at the end of the introduction.

If you're not provided guidelines, consider these factors:

- Research document : In a thesis or book-length study, the research rationale will be longer than in a journal article. For example, the background and rationale of this book exploring the collective memory of World War I cover more than ten pages.

- Research question : Research into a new sub-field may call for a longer or more detailed justification than a study that plugs a gap in literature.

Which verb tenses to use in the research rationale?

It's best to use the present tense. Though in a research proposal, the research rationale is likely written in the future tense, as you're describing the intended or expected outcomes of the research project (the gaps it will fill, the problems it will solve).

Example of a research rationale

Research question : What are the teachers' perceptions of how a sense of European identity is developed and what underlies such perceptions?

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology , 3(2), 77-101.

Burhan, A.M., Yang, J., & Inagawa, T. (2021). Impact of apathy on aging and age-related neuropsychiatric disorders. Research Topic. Frontiers in Psychiatry

Cataldo, I., Lepri, B., Neoh, M. J. Y., & Esposito, G. (2021). Social media usage and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence: A review. Frontiers in Psychiatry , 11.

CiCe Jean Monnet Network (2017). Guidelines for citizenship education in school: Identities and European citizenship children's identity and citizenship in Europe.

Cohen, l, Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education . Eighth edition. London: Routledge.

de Prat, R. C. (2013). Euroscepticism, Europhobia and Eurocriticism: The radical parties of the right and left “vis-à-vis” the European Union P.I.E-Peter Lang S.A., Éditions Scientifiques Internationales.

European Commission. (2017). Eurydice Brief: Citizenship education at school in Europe.

Polyakova, A., & Fligstein, N. (2016). Is European integration causing Europe to become more nationalist? Evidence from the 2007–9 financial crisis. Journal of European Public Policy , 23(1), 60-83.

Winter, J. (2014). Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

The AJE Team

See our "Privacy Policy"

Ensure your structure and ideas are consistent and clearly communicated

Pair your Premium Editing with our add-on service Presubmission Review for an overall assessment of your manuscript.

Up: Home : Study Guidance > Effective Writing and Referencing > What makes good justification?

- What makes good justification?

A justification is the reason why your thesis is valid. In economics, this typically involves explaining a theory which leads to the conclusion of your thesis.

A justification (theory) can come in many different forms:

A theoretical proposition can be explained in prose. This can be appropriate for simple concepts, but is often imprecise and it is a rare academic paper that does not rely on something more rigorous.

An example of a justification that can be satisfactorily described in words might be ‘an increase in income will lead to an increase in demand for normal goods’ (although even here an indifference curve diagram would make the same point with a greater degree of rigour).

b) Diagrams .

Familiar to all A-level students (and all undergraduates after the first week of lectures), diagrams are a simple way of presenting a theory and explaining what happens. You can clearly show why an individual’s labour supply curve might ‘bend backwards’ at high levels of income with an indifference curve diagram to explain the work/leisure tradeoff precisely.

An example of an appropriate justification using diagrams would be showing that firms in a perfectly competitive market set prices equal to marginal cost in the long run .

c) Mathematics .

There are two possibilities here. First, you can derive a simple mathematical result yourself, and discuss the implications of it. Second, you can state an equation and discuss the implications of it.

A simple example of the first would be to show that monopolies set prices above marginal cost. Let:

π(q) = p(q) – c(q) where π(q) is profit , p(q) is price, q is quantity and c(q) is cost

p = c'(q) – p'(q)q by taking derivatives with respect to q and setting π'(q)=0

And as dp / dq <0 for a monopoly selling ordinary goods ⇒ p > c'(q)

Actually, this can also be shown by a diagram – but in many other examples, maths is clearer. These might include accurate exposition of the principal-agent problem.

Previous: Writing the Economics Essay

Next: What makes good support?

Share this page: Email , Facebook , LinkedIn , Twitter

- Note Taking in Economics

- Effective Economics Reading

- Data Collection for Economics Assignments

- Writing the Economics Essay

- What makes good support?

- Structuring an Essay

- Referencing

- Presentation and Group Work

- Revision for an Economics Exam

- Maths Help for Economics Students

Published by The Economics Network at the University of Bristol . All rights reserved. Feedback: [email protected] Supported by the Royal Economic Society and the Scottish Economic Society

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Write a Problem Statement | Guide & Examples

How to Write a Problem Statement | Guide & Examples

Published on November 6, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 20, 2023.

A problem statement is a concise and concrete summary of the research problem you seek to address. It should:

- Contextualize the problem. What do we already know?

- Describe the exact issue your research will address. What do we still need to know?

- Show the relevance of the problem. Why do we need to know more about this?

- Set the objectives of the research. What will you do to find out more?

Table of contents

When should you write a problem statement, step 1: contextualize the problem, step 2: show why it matters, step 3: set your aims and objectives.

Problem statement example

Other interesting articles

Frequently asked questions about problem statements.

There are various situations in which you might have to write a problem statement.

In the business world, writing a problem statement is often the first step in kicking off an improvement project. In this case, the problem statement is usually a stand-alone document.

In academic research, writing a problem statement can help you contextualize and understand the significance of your research problem. It is often several paragraphs long, and serves as the basis for your research proposal . Alternatively, it can be condensed into just a few sentences in your introduction .

A problem statement looks different depending on whether you’re dealing with a practical, real-world problem or a theoretical issue. Regardless, all problem statements follow a similar process.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

The problem statement should frame your research problem, giving some background on what is already known.

Practical research problems

For practical research, focus on the concrete details of the situation:

- Where and when does the problem arise?

- Who does the problem affect?

- What attempts have been made to solve the problem?

Theoretical research problems

For theoretical research, think about the scientific, social, geographical and/or historical background:

- What is already known about the problem?

- Is the problem limited to a certain time period or geographical area?

- How has the problem been defined and debated in the scholarly literature?

The problem statement should also address the relevance of the research. Why is it important that the problem is addressed?

Don’t worry, this doesn’t mean you have to do something groundbreaking or world-changing. It’s more important that the problem is researchable, feasible, and clearly addresses a relevant issue in your field.

Practical research is directly relevant to a specific problem that affects an organization, institution, social group, or society more broadly. To make it clear why your research problem matters, you can ask yourself:

- What will happen if the problem is not solved?

- Who will feel the consequences?

- Does the problem have wider relevance? Are similar issues found in other contexts?

Sometimes theoretical issues have clear practical consequences, but sometimes their relevance is less immediately obvious. To identify why the problem matters, ask:

- How will resolving the problem advance understanding of the topic?

- What benefits will it have for future research?

- Does the problem have direct or indirect consequences for society?

Finally, the problem statement should frame how you intend to address the problem. Your goal here should not be to find a conclusive solution, but rather to propose more effective approaches to tackling or understanding it.

The research aim is the overall purpose of your research. It is generally written in the infinitive form:

- The aim of this study is to determine …

- This project aims to explore …

- This research aims to investigate …

The research objectives are the concrete steps you will take to achieve the aim:

- Qualitative methods will be used to identify …

- This work will use surveys to collect …

- Using statistical analysis, the research will measure …

The aims and objectives should lead directly to your research questions.

Learn how to formulate research questions

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

You can use these steps to write your own problem statement, like the example below.

Step 1: Contextualize the problem A family-owned shoe manufacturer has been in business in New England for several generations, employing thousands of local workers in a variety of roles, from assembly to supply-chain to customer service and retail. Employee tenure in the past always had an upward trend, with the average employee staying at the company for 10+ years. However, in the past decade, the trend has reversed, with some employees lasting only a few months, and others leaving abruptly after many years.

Step 2: Show why it matters As the perceived loyalty of their employees has long been a source of pride for the company, they employed an outside consultant firm to see why there was so much turnover. The firm focused on the new hires, concluding that a rival shoe company located in the next town offered higher hourly wages and better “perks”, such as pizza parties. They claimed this was what was leading employees to switch. However, to gain a fuller understanding of why the turnover persists even after the consultant study, in-depth qualitative research focused on long-term employees is also needed. Focusing on why established workers leave can help develop a more telling reason why turnover is so high, rather than just due to salaries. It can also potentially identify points of change or conflict in the company’s culture that may cause workers to leave.

Step 3: Set your aims and objectives This project aims to better understand why established workers choose to leave the company. Qualitative methods such as surveys and interviews will be conducted comparing the views of those who have worked 10+ years at the company and chose to stay, compared with those who chose to leave.

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

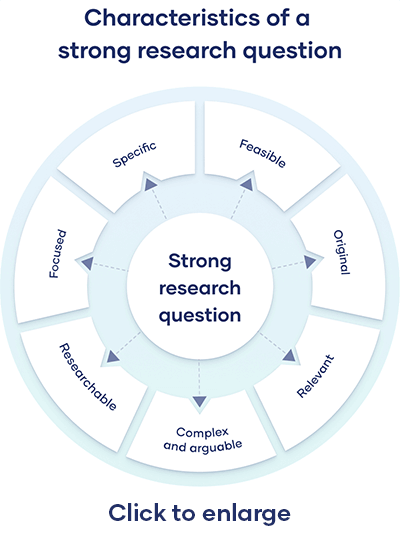

All research questions should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly

Research objectives describe what you intend your research project to accomplish.

They summarize the approach and purpose of the project and help to focus your research.

Your objectives should appear in the introduction of your research paper , at the end of your problem statement .

Your research objectives indicate how you’ll try to address your research problem and should be specific:

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 20). How to Write a Problem Statement | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 16, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/problem-statement/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to choose a dissertation topic | 8 steps to follow, how to define a research problem | ideas & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

On Degrees of Justification

- Original Article

- Published: 27 August 2011

- Volume 77 , pages 237–272, ( 2012 )

Cite this article

- Gregor Betz 1

484 Accesses

10 Citations

Explore all metrics

This paper gives an explication of our intuitive notion of strength of justification in a controversial debate. It defines a thesis’ degree of justification within the theory of dialectical structures as the ratio of coherently adoptable positions according to which that thesis is true over all coherently adoptable positions. Broadening this definition, the notion of conditional degree of justification, i.e. degree of partial entailment, is introduced. Thus defined degrees of justification correspond to our pre-theoretic intuitions in the sense that supporting and defending a thesis t increases, whereas attacking it decreases, t ’s degree of justification. Moreover, it is shown that (conditional) degrees of justification are (conditional) probabilities. Eventually, the paper explains that it is rational to believe theses with a high degree of justification inasmuch as this strengthens the robustness of one’s position.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The pragmatic turn in the scientific realism debate

Sandy C. Boucher & Curtis Forbes

What is a Conspiracy Theory?

M. Giulia Napolitano & Kevin Reuter

Reliabilist epistemology meets bounded rationality

Giovanni Dusi

Compare for example Rahmstorf and Schellnhuber ( 2006 ).

The approach presented in this paper, however, rejects a major principle of Pollock’s theory, namely the weakest link principle.

A dialectical structure is a special type of bipolar argumentation framework in the sense of Cayrol and Lagasquie-Schiex ( 2005 ). Cayrol and Lagasquie-Schiex extend the abstract approach of Dung ( 1995 ) by adding support-relations to Dung’s framework which originally considered attack-relations between arguments only. A specific interpretation of Dung’s abstract framework that analyses arguments as premiss-conclusion structures is carried out in Bondarenko et al. ( 1997 ).

Note that, unlike in approaches by Lin and Shoham ( 1989 ) or the interpretation by Prakken and Vreeswijk ( 2001 , p. 256) of Dung ( 1995 ), T is not supposed to contain arguments which can be constructed given the propositions put forward in a debate (or, more generally, some INPUT) but only those arguments that have been explicitly stated (though not necessarily fully). This emphasis on real reasoning as opposed to ideal reasoning seems to be more in line with the approaches of Pollock ( 1987 , 1995 ), Vreeswijk ( 1997 ), or Verheij ( 1996 ).

Accordingly, if two arguments conflict, i.e. possess contrary conclusions, they do not necessarily attack each other as defined here. The “assumption attack” as well as “undercutting” an argument (cf. Pollock 1970 ; Prakken and Vreeswijk 2001 ) can both be represented in this framework as an attack on an argument’s premiss. Moreover, indirect attacks, i.e. attacks on an argument’s subconclusion c − can be made explicit by reconstructing the attacked argument as two arguments, a 1 and a 2 , such that c − is the conclusion of a 1 and a premiss of a 2 , a 1 supporting a 2 and a 2 being the argument attacked.

Recall that we assume arguments to be reconstructed as deductively valid.

To see this in more detail, let \({\mathcal{P}}_P\) be a partial position that is merely extended by the (highly plausible) complete position \(\mathcal{Q}_1\) , whereas \({\mathcal{P}}_I\) is extended by the implausible positions \(\mathcal{Q}_2\) and \(\mathcal{Q}_3\) . We have, according to the law of total probability (whose application is warranted in Sect. 6 ),

which contradicts our intuitive judgement. But augmenting the dialectical structure and extending the background knowledge turns the \(\mathcal{Q}_i\) into partial positions. Moreover, this increases \({\textsc{Doj}}(\mathcal{Q}_1)\) , thereby raising \({\textsc{Doj}}({\mathcal{P}}_P)\) , and decreases \({\textsc{Doj}}(\mathcal{Q}_2)\) as well as \({\textsc{Doj}}(\mathcal{Q}_3)\) , thus lowering \({\textsc{Doj}}({\mathcal{P}}_I)\) .

Betz, G. (2008). Evaluating dialectical structures with Bayesian methods. Synthese 163 , 25–44.

Article Google Scholar

Betz, G. (2009). Evaluating dialectical structures. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 38 (3), 283–312.

Betz, G. (2010). Theorie dialektischer Strukturen . Frankfurt am Main: Klostermann.

Google Scholar

Bondarenko, A., Dung, P. M., Kowalski, R. A., & Toni, F. (1997). An abstract, argumentation-theoretic approach to default reasoning. Artificial Intelligence, 93 (1–2), 63–101.

Carnap, R. (1950). Logical foundations of probability . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cayrol, C., & Lagasquie-Schiex, M.-C. (2005). On the acceptability of arguments in bipolar argumentation frameworks. In L. Godo (Ed.), ECSQARU, volume 3571 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science (pp. 378–389). Berlin: Springer.

Dung, P. M. (1995). On the acceptability of arguments and its fundamental role in nonmonotonic reasoning, logic programming and n-person games. Artificial Intelligence, 77 (2), 321–358.

Haenni, R., & Lehmann, N. (2003). Probabilistic argumentation systems: A new perspective on the dempster-shafer theory. International Journal of Intelligent Systems, 18 (1), 93–106.

Haenni, R., Kohlas, J., & Lehmann, N. (2000). Probabilistic argumentation systems. In J. Kohlas & S. Moral (Eds.), Handbook of defeasible reasoning and uncertainty management systems, volume 5: Algorithms for uncertainty and defeasible argumentation . Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Kohlas, J. (2003). Probabilistic argumentation systems: A new way to combine logic with probability. Journal of Applied Logic, 1 (3–4), 225–253.

Laskey, K. B., & Lehner, P. E. (1989). Assumptions, beliefs and probabilities. Artificial Intelligence, 41 (1), 65–77.

Lin, F., & Shoham, Y. (1989). Argument systems: A uniform basis for nonmonotonic reasoning. In R. J. Brachman, H. J. Levesque, & R. Reiter (Eds.), Proceedings of the 1st international conference on principles of knowledge representation and reasoning . Morgan Kaufmann, Massachusetts, pp. 245–255.

Pollock, J. L. (1970). The structure of epistemic justification. American Philosophical Quarterly, 4 , 62–78.

Pollock, J. L. (1987). Defeasible reasoning. Cognitive Science 11 (4), 481–518.

Pollock, J. L. (1995). Cognitive Carpentry. A Blueprint for How to Build A Person . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Pollock, J. L. (2001). Defeasible reasoning with variable degrees of justification. Artificial Intelligence, 133 (1–2), 233–282.

Prakken, H., & Vreeswijk, G. (2001). Logics for defeasible argumentation. In D. M. Gabbay & F. Guenthner (Eds.), Handbook of philosophical logic (2nd ed., Vol. 4, pp. 219–318). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Rahmstorf, S., & Schellnhuber, H. J. (2006). Der Klimawandel . München: C.H. Beck.

Rosenhead, J. (2001) Robustness analysis. In Rational analysis for a problematic world revisited (2nd ed., pp. 181–207). Chichester:Wiley.

Verheij, B. (1996). Rules, reasons, arguments. Formal studies of argumentation and defeat . Dissertation Universiteit Maastricht.

Vreeswijk, G. A. W. (1997). Abstract argumentation systems. Artificial Intelligence, 90 (1–2), 225–279.

Download references

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the tau-Klub at Freie Universitaet Berlin and members of the Department of Computer Science at the University of Liverpool for discussing an earlier version of this article. Moreover, he is particularly grateful to two anonymous reviewers of Erkenntnis for their astute and helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Institute of Philosophy, Kaiserstrasse 12, Build. 20.12, 76128, Karlsruhe, Germany

Gregor Betz

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gregor Betz .

Appendix 1: Proofs of Propositions

1.1 proof of proposition 1.

Assume \(a \rightarrow t\) . Let σ (σ′) denote the number of all dialectically coherent, complete positions on τ (τ′), and σ p (σ p ′) the number of dialectically coherent, complete positions on τ (τ′) corresponding to which p is true. Now, consider an arbitrary dialectically coherent, complete position \({\mathcal{P}}\) on τ corresponding to which p is true. Because argument a is assumed to be independent, and because its conclusion is true in \({\mathcal{P}}\) , any truth value assignment to its premisses will extend \({\mathcal{P}}\) to a dialectically coherent, complete position on τ′. If a has n premisses, there will be 2 n dialectically coherent, complete position on τ′ which extend \({\mathcal{P}}\) . As a next step, consider an arbitrary dialectically coherent, complete position \(\mathcal{Q}\) on τ corresponding to which p is false. Those and only those truth value assignments to premisses of a according to which not all premisses are true will extend \(\mathcal{Q}\) to a dialectically coherent, complete position on τ′. So, there will be 2 n − 1 dialectically coherent, complete position on τ′ which extend \(\mathcal{Q}\) . According to Lemma 1, every dialectically coherent, complete position on τ′ extends a dialectically coherent, complete position on τ. Hence, we can calculate the number of positions on τ′ as follows:

For symmetrical reasons, \({\textsc{Doj}}_{\tau'}(p)<{\textsc{Doj}}_{\tau}(p)\) if \(a \rightsquigarrow t\) .

1.2 Proof of Proposition 2

We calculate to how many different dialectically coherent, complete positions on τ′ the respective positions on τ can be extended. (In this proof, all positions are understood to be dialectically coherent and complete.) We shall assume that a contains n premisses, and b contains m premisses. Consider the first case, i.e. \(a \rightarrow t\) and \(b\rightarrow a\) , and let q be the conclusion of b (and therefore a premiss of a ). Since a is independent in τ, the ratio of (1) positions on τ according to which p and q are true over (2) positions on τ according to which p is true but q is false equals 2 n −1 :2 n −1 . This is because all 2 n truth value assignments to a ’s premisses satisfy the coherence constraint if a ’s conclusion, p , is true, and q is true in exactly half of these. Yet, if a ’s conclusion is false, there is one truth value assignment to its premisses which will not figure in a position on τ, namely the one which considers all premisses true. So, in that case, there are only 2 n − 1 corresponding truth value assignments, 2 n −1 of which regard q as false and 2 n −1 − 1 take q as true. The ratio of (1) positions on τ according to which p is false and q is true over (2) positions on τ according to which p and q are false equals therefore \(2^{n-1}-1:2^{n-1}.\)

Every position on τ with true q can be extended to 2 m different positions on τ′. In other words, the positions with true q are multiplied by 2 m when introducing b . Still, a position on τ with false q can only be extended to 2 m − 1 different positions on τ′.

Given (a) the ratio of positions on τ with p and q true over positions with p true and q false, and (b) the respective multipliers, the number of positions on τ with p true is multiplied by the following factor when introducing b :

Likewise, the number of positions on τ with p false is multiplied by the following factor when introducing b :

So the number of positions on τ with p true is multiplied by a greater factor than the number of positions with p false, and that is why p ’s degree of justification increases when introducing b .

We will briefly consider the second case, that is \(a \rightarrow t\) and \(b\rightsquigarrow a\) . (Cases (3) and (4) hold for analogous reasons.) Let \(\lnot q\) be the conclusion of b . The ratios of positions on τ as calculated in the first case do apply. Yet, because \(b\rightsquigarrow a\) , a position on τ with q true can be extended to 2 m − 1 different positions on τ′. Every position on τ with q false yields 2 m positions on τ′ when introducing b . This implies for the corresponding factors m 2 and m 1 :

Thus, a position in τ with p false can be extended to, on average, more positions in τ′ than a position in τ with p true. As a consequence, p ’s degree of justification decreases when introducing b .

1.3 Proof of Proposition 3

We prove, in this appendix, statements (1) and (2) of Proposition 3 only, claims (3) and (4) follow symmetrically. We consider statement (1), first. So, let us assume that \(\tau,\,\tau',\,a,\,\mathcal{B}\) and \({\mathcal{P}}\) are given as assumed in the theorem. We shall denote the number of complete and coherent position on τ and τ′ as follows,

As these distinctions are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive, we have,

The introduction of the new argument a with its n premisses that don’t figure in τ multiplies the number of coherent positions. For every complete and coherent position \(\mathcal{Q}\) in τ which considers c true, there are 2 n corresponding complete and coherent positions in τ′ (which extend \(\mathcal{Q}\) ). A complete and coherent position \(\mathcal{Q'}\) in τ which considers c false, however, is merely extended by 2 n − 1 complete and coherent positions in τ′, because assigning all premisses the value t doesn’t yield a coherent position if the conclusion is false. In sum, we obtain the following equations,

The number of conditionally complete and coherent positions on τ′ relative to the background knowledge \(\mathcal{B}\) can be related to the number of positions on τ, as well. If the truth-value of on of a ’s premisses is fixed, truth-values can be assigned only to the remaining ( n − 1) premisses. That’s why every complete and coherent position \(\mathcal{Q}\) in τ which considers c true, yields 2 n −1 corresponding complete and coherent positions in τ′ given \(\mathcal{B}\) , and every complete and coherent position \(\mathcal{Q'}\) in τ which considers c false is extended by 2 n −1 − 1 complete and coherent positions. Accordingly,

We can now derive the sought-after inequality, starting with the assumption that the introduction of a has in fact increased the degree of justification of \({\mathcal{P}},\)

as \(\sigma_{\mathcal{P}}>0\) and \(\sigma_{\lnot {\mathcal{P}}}>0,\)

with (1) we obtain,

substituting (2) and applying (1), again, yields,

according to (1),

we rearrange,

add two additional terms,

and may then factorize,

applying (1),

with (3) and, respectively, (2), this becomes,

and, according to (1), we finally have,

This proves statement (1) of Proposition 3. It is comparatively easy to justify substatement (2). If a premiss of the argument a is fixed as false according to the background knowledge, any assignment of truth-values to the remaining premisses extends a complete and coherent position \(\mathcal{Q}\) on τ to a complete and coherent position on τ′ given the background knowledge—no matter whether \(\mathcal{Q}\) considers the conclusion c true or false. But then, \({\textsc{Doj}}_{\tau'}({\mathcal{P}}|\mathcal{B})\) equals \({\textsc{Doj}}_{\tau}({\mathcal{P}})\) , which is, by assumption, smaller than \({\textsc{Doj}}_{\tau'}({\mathcal{P}})\) .

1.4 Proof of Proposition 4

Since neither s nor \(\lnot s\) figures in any arguments in τ, every complete and coherent position on τ can be extended to a complete and coherent position on τ′ in two ways, namely both by assigning s the value t or by assigning it the value f . We thus have, for an arbitrary partial position \({\mathcal{P}}\) on τ,

1.5 Proof of Proposition 5

Let us consider a dialectical structure τ′′ which is obtained from τ by adding the sentences \(p_1,\ldots,p_n\) and c to the respective sentence pool (e.g. by way of introducing theses), without introducing the argument a . Every complete and coherent position \(\mathcal{Q}\) on τ is, correspondingly, extended by 2 n +1 complete and coherent positions on τ′′. Because of the argument a , exactly one of these complete and coherent positions on τ′′ is not coherent on τ′. That is why a complete and coherent position \(\mathcal{Q}\) on τ is extended by (2 n +1 − 1) complete and coherent positions on τ′. We thus obtain, for arbitrary partial positions \({\mathcal{P}}\) on τ,

Appendix 2: Dialectically Coherent Positions and Complete, Closed Subdebates in Equilibrium

Before we relate the notion of a dialectically coherent position to the concept of a complete, closed subdebate in equilibrium, I repeat, without comment, the relevant definitions from Betz ( 2009 ).

Definition 17

(Validity-function) Let \(\tau = \langle T,A,U \rangle\) be a dialectical structure. A function v : T → {0,1} is called a validity-function on τ iff for all \(a \in T\) : \((v(a)=0 \leftrightarrow \exists b\in T: b\rightsquigarrow a \land v(b)=1)\) .

If the validity-function exists on τ and is unique, it is labelled “ϑ” and an argument \( a \in T\) is called “τ-valid” iff ϑ( a ) = 1, “τ-invalid” otherwise.

Definition 18

( Free premiss ) Let \(\tau = \langle T,A,U \rangle\) be given. A premiss p of an argument in τ is called “bound in τ” iff

If and only if a premiss is not bound in τ, it is “free in τ”. The set of all free premisses of τ is called \(\Uppi_\tau\) .

Definition 19

( Equilibrium ) A dialectical structure \(\tau = \langle T,A,U \rangle\) is said to be in equilibrium iff not

for some sentence p .

Definition 20

( Stance-attribution ) Let \(\tau = \langle T,A,U \rangle\) , and \(O=\{o_1, \ldots, o_k\}\) be a set of proponents. A function \(S:O\rightarrow{\bf P}(T)\) which assigns each proponent a subset \(T_i\subseteq T\) is called a stance-attribution on τ. \(\tau_i = \langle S(o_i),A|_{S(o_i)},U|_{S(o_i)}\rangle\) is the subdebate accepted by o i . A proponent o i claims that

All \(p\in \Uppi_{\tau_i}\) are true.

All C ( a ) (with \(a \in S(o_i)\) is τ i -valid) are true.

Definition 21

( Closed subdebates ) Let \(\tau = \langle T,A,U \rangle\) be a dialectical structure and \(S:O\rightarrow{\bf P}(T)\) a stance-attribution on τ. A subdebate τ i induced by S is called “closed” iff there is no \(a \in (T\setminus T_i)\) such that \(\Uppi_{\tau_i}=\Uppi_{\tau'},\,\tau'=\langle S(o_i)\cup \{a\},A|_{S(o_i)\cup \{a\}},U|_{S(o_i)\cup \{a\}} \rangle\) .

Betz ( 2009 ) stipulated that a subdebate has to be complete in order to represent a position a proponent can rationally adopt in a debate, for otherwise the status assignment might not even exist on her subdebate. The following attempt to relate the concept of a coherent position (as truth value assignment) and the notion of a closed, complete subdebate in equilibrium will show that subdebates have to satisfy an additional condition in order to represent rational positions: for each sentence whose negation occurs in the debate as well, the proponent has to assert exactly one of both in a thesis. As the completeness condition already required that specific theses exist in a dialectical structure, I propose to modify and extend the definition of a complete stance-attribution as follows instead of introducing a further condition.

Definition 22

( Complete stance-attribution ) Let \(\tau = \langle T,A,U \rangle\) be a dialectical structure. The stance-attribution \(S:\{o_1,\ldots,o_k\}\rightarrow {\bf P}(T)\) is called “complete” iff for every induced subdebate τ i ( \(i=1\ldots k\) ) there is a τ i -valid thesis \(t\in T_i\) stating either p or \(\lnot p\)

for every pair of contradictory sentences \(p,\lnot p\) which both occur in τ while neither p nor \(\lnot p\) occurs in τ i ,

for every conclusion p of a τ i -invalid argument which neither attacks nor supports another argument in τ i , and

for every red circle C in τ i such that

t attacks one of C ’s arguments,

t is neither part of a red circle itself nor connected to a red circle via a red directed path from that circle to a C , and

t is assigned the validity value 1 according to a partial evaluation of \(\tau_i,\,\vartheta_{\rm partial}\) , which excludes all arguments in red circles.

As a final preliminary concept, we introduce

Definition 23

( Generated v-function ) Let \(\tau = \langle T,A,U \rangle\) be a dialectical structure and \(\mathcal{Q}\) be a complete position on τ. A function \(v:T\rightarrow\{0,1\}\) is generated by \(\mathcal{Q}\) iff for every argument \(a\in T\) with premisses \(p_1,\ldots,p_n\) :

v is called a v-function.

With these definitions at hand, we can now proof

Proposition 9

(Construction of dialectically coherent position) Let \(S: \{o_1, \ldots ,o_k\}\rightarrow {\bf P}(T)\) be a complete stance-attribution on the dialectical structure \(\tau=\langle T,A,U \rangle\) . If the induced subdebate τ i is closed, in equilibrium, and the validity function ϑ exists on τ i , then there is a dialectically coherent, complete position \(\mathcal{Q}\) on τ s uch that for the v-function v which is generated by \(\mathcal{Q}\) :

Let \(\Uppi_{\tau_i}\) denote the set of free premisses of τ i . We construct \(\mathcal{Q}\) on τ i first, show that \(\mathcal{Q}|_{\tau_i}\) satisfies the coherence constraints on τ i , and then proceed by extending \(\mathcal{Q}\) to those sentences that do not occur in τ i .

Step 1: We set for every sentence p that occurs in τ i

To see that \(\mathcal{Q}|_{\tau_i}\) assigns complementary truth values to contradictory sentences (constraint 2 in Definition 5), consider p , q with \(q\leftrightarrow \lnot p\) occurring in τ i . If p is a τ i -free premiss or the conclusion of a τ i -valid argument, then q is not because τ i is in equilibrium and thence \(\mathcal{Q}(p)={\bf t}, \mathcal{Q}(q)={\bf f}\) . If, in contrast, both p and q are neither τ i -free premisses nor conclusions of τ i -valid arguments, then both are conclusions of τ i -invalid arguments only. Yet as τ i is complete, there are no pairs of contradictory sentences which are but conclusions τ i -invalid arguments. So the second case does not arise. We still have to show that \(\mathcal{Q}|_{\tau_i}\) assigns conclusions the value t if the corresponding premisses are true (constraint 3 in Definition 5): If for all premisses \(p_1\ldots p_n\) of some \(a \in T_i\) it holds that \(\mathcal{Q}(p_1)=\ldots=\mathcal{Q}(p_n)={\bf t}\) , then a is by construction not attacked by any τ i -valid argument—τ i would not be in equilibrium otherwise—, and therefore \(\mathcal{Q}(C(a))={\bf t}\) .

Step 2: We extend \(\mathcal{Q}\) to \(\tau \setminus \tau_i\) as follows (note that we consider sentences that do occur in τ but not in τ i ): Every sentence p whose negation occurs in τ i is assigned the complementary truth value to \(\mathcal{Q}(\lnot p)\) . Every remaining sentence is set to f . Now, let us complete the check for dialectical coherency. Let p , q be two contradictory sentences, not both in τ i (if one of both is in τ i the construction ensures that they are assigned complementary truth values). But by completeness of S , there is a thesis in τ i that states either p or q , and therefore the construction guarantees \(\mathcal{Q}(p)\) and \(\mathcal{Q}(q)\) are complementary. Next, does \(\mathcal{Q}\) satisfy the ‘deduction constraint’ (constraint 3 in Definition 5)? The first thing to note is that every argument \(a \in \tau \backslash \tau_i\) contains at least one premiss which is false. For otherwise, every premiss p of a were either (1) a τ i -free premiss in τ i , (2) a conclusion of a τ i -valid argument, or (3) the negation of a sentence in τ i that is neither (1) nor (2). Yet, since by completeness of S the only sentences in τ i that are neither (1) nor (2) are negations of conclusions of τ i -valid arguments, (3) amounts to being the conclusion of a τ i -valid argument, i.e. (2). Hence τ i would not be a closed subdebate. Now because every argument a in \(\tau\setminus\tau_i\) has at least one false premiss, \(\mathcal{Q}\) satisfies the deduction constraint. Also, this fact guarantees that v ( a ) = 0. \(\square\)

The final proposition tells us how to construct a closed subdebate in equilibrium which corresponds to a given dialectically coherent, complete position.

Proposition 10

(Construction of stance-attribution) Let \(\tau=\langle T,A,U \rangle\) be a dialectical structure and v a v-function that is generated by a dialectically coherent, complete position \(\mathcal{Q}\) on τ. There exists a stance-attribution \(S:\{o\}\rightarrow {\bf P}(T)\) inducing the subdebate τ o such that

v is a validity function on τ o ,

τ o is in equilibrium ,

τ o is closed .

First, we construct τ o iteratively. Let \(T_0=\emptyset\) and apply the following rule provided T n is given

(R) Let T * be the set of all arguments \(a \in T \backslash T_n\) such that for every premiss p of a : \(\mathcal{Q}(p)={\bf t}\) or p negates the conclusion of an argument \(b\in T_n\) with v ( b ) = 1. If T * = \(\emptyset\) then T o = T n , STOP. Otherwise T n +1 = T n ∪ T * .

Ad 1): We show that \(\vartheta:T_o \rightarrow \{0,1\}\) with \(a \mapsto v(a)\) is a validity function on τ o . By construction an argument \(a \in T_o\) has a premiss p with \(\mathcal{Q}(p)={\bf f}\) if and only if there is an argument b which is τ o -valid and attacks a . Thus, ϑ does satisfy the recursive definition of a validity function.

Ad 2): Assume that τ o were not in equilibrium, that is there were a sentence p such that both p and \(\lnot p\) are (1) a τ o -free premiss or (2) a conclusion of a τ o -valid argument. If p were a τ o -free premiss in argument a , then (by definition of “free premiss”) \(\lnot p\) couldn’t be the conclusion of a τ o -valid argument. So \(\lnot p\) would be a τ o -free premiss in some argument b , too. Because of dialectical coherency, \(\mathcal{Q}(p)\) is complementary to \(\mathcal{Q}(\lnot p)\) , and thence the algorithm would not have picked a and b . Yet if p were the conclusion of a τ o -valid argument, \(\lnot p\) would not be τ o -free and would thus be the conclusion of a τ o -valid argument, too. Still, this contradicts the assumption that \(\mathcal{Q}\) is dialectically coherent.

Ad 3): Assume there were an argument \(a \in T\setminus T_o\) such that adding a to τ o would not increase the set of τ o -free premisses. Then every premiss of a would either be (1) a τ o -free premiss of some argument in T o (and thus be true), (2) the conclusion of a τ o -valid argument’s conclusion (and thus be true), or (3) the negation of a τ o -valid argument’s conclusion. Therefore, the rule (R) would have picked a and would not have stopped. \(\square\)

So not only can we construct dialectically coherent, complete positions from stance-attributions, but, inversely, every coherent position corresponds to a closed subdebate in equilibrium. Note that such a subdebate is not necessarily complete since the dialectical structure τ might simply not contain enough theses.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Betz, G. On Degrees of Justification. Erkenn 77 , 237–272 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-011-9314-y

Download citation

Received : 21 September 2010

Accepted : 20 July 2011

Published : 27 August 2011

Issue Date : September 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-011-9314-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Partial Position

- Rational Belief

- Argumentation Framework

- Inferential Relation

- Dialectical Structure

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

7 Examples of Justification (of a project or research)

The justification to the part of a research project that sets out the reasons that motivated the research. The justification is the section that explains the importance and the reasons that led the researcher to carry out the work.

The justification explains to the reader why and why the chosen topic was investigated. In general, the reasons that the researcher can give in a justification may be that his work allows to build or refute theories; bring a new approach or perspective on the subject; contribute to the solution of a specific problem (social, economic, environmental, etc.) that affects certain people; generate meaningful and reusable empirical data; clarify the causes and consequences of a specific phenomenon of interest; among other.

Among the criteria used to write a justification, the usefulness of the research for other academics or for other social sectors (public officials, companies, sectors of civil society), the significance in time that it may have, the contribution of new research tools or techniques, updating of existing knowledge, among others. Also, the language should be formal and descriptive.

Examples of justification

- This research will focus on studying the reproduction habits of salmon in the Mediterranean region of Europe, since due to recent ecological changes in the water and temperatures of the region produced by human economic activity , the behavior of these animals has been modified. Thus, the present work would allow to show the changes that the species has developed to adapt to the new circumstances of its ecosystem, and to deepen the theoretical knowledge about accelerated adaptation processes, in addition to offering a comprehensive look at the environmental damage caused by growth. unsustainable economic, helping to raise awareness of the local population.

- We therefore propose to investigate the evolution of the theoretical conceptions of class struggle and economic structure throughout the work of Antonio Gramsci, since we consider that previous analyzes have overlooked the fundamentally dynamic and unstable conception of human society that is present. in the works of Gramsci, and that is of vital importance to fully understand the author’s thought.

- The reasons that led us to investigate the effects of regular use of cell phones on the health of middle-class young people under 18 years of age are centered on the fact that this vulnerable sector of the population is exposed to a greater extent than the rest of society to risks that the continuous use of cell phone devices may imply, due to their cultural and social habits. We intend then to help alert about these dangers, as well as to generate knowledge that helps in the treatment of the effects produced by the abuse in the use of this technology.

- We believe that by means of a detailed analysis of the evolution of financial transactions carried out in the main stock exchanges of the world during the period 2005-2010, as well as the inquiry about how financial and banking agents perceived the situation of the financial system, it will allow us to clarify the economic mechanisms that enable the development of an economic crisis of global dimensions such as the one that the world experienced since 2009, and thus improve the design of regulatory and counter-cyclical public policies that favor the stability of the local and international financial system.

- Our study about the applications and programs developed through the three analyzed programming languages (Java, C ++ and Haskell), can allow us to clearly distinguish the potential that each of these languages (and similar languages) present for solving specific problems. , in a specific area of activity. This would allow not only to increase efficiency in relation to long-term development projects, but to plan coding strategies with better results in projects that are already working, and to improve teaching plans for teaching programming and computer science.

- This in-depth study on the expansion of the Chinese empire under the Xia dynasty, will allow to clarify the socioeconomic, military and political processes that allowed the consolidation of one of the oldest states in history, and also understand the expansion of metallurgical and administrative technologies along the coastal region of the Pacific Ocean. The deep understanding of these phenomena will allow us to clarify this little-known period in Chinese history, which was of vital importance for the social transformations that the peoples of the region went through during the period.

- Research on the efficacy of captropil in the treatment of cardiovascular conditions (in particular hypertension and heart failure) will allow us to determine if angiotensin is of vital importance in the processes of blocking the protein peptidase, or if by the On the contrary, these effects can be attributed to other components present in the formula of drugs frequently prescribed to patients after medical consultation.

Related posts:

- Research Project: Information and examples

- 15 Examples of Empirical Knowledge

- 10 Paragraphs about Social Networks

- 15 Examples of Quotes

- What are the Elements of Knowledge?

Privacy Overview

7.3 Justification

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain what justification means in the context of epistemology.

- Explain the difference between internal and external theories of justification.

- Describe the similarities and differences between coherentism and foundationalism.

- Classify beliefs according to their source of justification.

Much of epistemology in the latter half of the 20th century was devoted to the question of justification . Questions about what knowledge is often boil down to questions about justification. When we wonder whether knowledge of the external world is possible, what we really question is whether we can ever be justified in accepting as true our beliefs about the external world. And as previously discussed, determining whether a defeater for knowledge exists requires knowing what could undermine justification.

We will start with two general points about justification. First, justification makes beliefs more likely to be true. When we think we are justified in believing something, we think we have reason to believe it is true. How justification does this and how to think about the reasons will be discussed below. Second, justification does not always guarantee truth . Justification makes beliefs more likely to be true, which implies that justified beliefs could still be false. The fallibility of justification will be addressed at the end of this section.

The Nature of Justification

Justification makes a belief more likely to be true by providing reasons in favor of the truth of the belief. A natural way to think of justification is that it provides logical support. Logic is the study of reasoning, so logical support is strong reasoning. If I am reasoning correctly, I am justified in believing that my dog is a mammal because all dogs are mammals. And I am justified in believing that 3 1332 = 444 3 1332 = 444 if I did the derivation correctly. But what if I used a calculator to derive the result? Must I also have reasons for believing the calculator is reliable before being justified in believing the answer? Or can the mere fact that calculators are reliable justify my belief in the answer? These questions get at an important distinction between the possible sources of justification—whether justification is internal or external to the mind of the believer.

Internalism and Externalism

Theories of justification can be divided into two different types: internal and external. Internalism is the view that justification for belief is determined solely by factors internal to a subject’s mind. The initial appeal of internalism is obvious. A person’s beliefs are internal to them, and the process by which they form beliefs is also an internal mental process. If you discover that someone engaged in wishful thinking when they came to the belief that the weather would be nice today, even if it turns out to be true, you can determine that they did not know that it would be nice today. You will believe they did not have that knowledge because they had no reasons or evidence on which to base their belief. When you make this determination, you reference that person’s mental state (the lack of reasons).

But what if a person had good reasons when they formed a belief but cannot currently recall what those reasons were? For example, I believe that Aristotle wrote about unicorns, although I cannot remember my reasons for believing this. I assume I learned it from a scholarly text (perhaps from reading Aristotle himself), which is a reliable source. Assuming I did gain the belief from a reliable source, am I still justified given that I cannot now recall what that source was? Internalists contend that a subject must have cognitive access to the reasons for belief in order to have justification. To be justified, the subject must be able to immediately or upon careful reflection recall their reasons. Hence, according to internalism , I am not justified in believing that Aristotle wrote about unicorns.

On the other hand, an externalist would say my belief about Aristotle is justified because of the facts about where I got the belief. Externalism is the view that at least some part of justification can rely on factors that are not internal or accessible to the mind of the believer. If I once had good reasons, then I am still justified, even if I cannot now cite those reasons. Externalist theories about justification usually focus on the sources of justification, which include not only inference but also testimony and perception. The fact that a source is reliable is what matters. To return to the calculator example, the mere fact that a calculator is reliable can function as justification for forming beliefs based on its outputs.

An Example of Internalism: Ruling Out Relevant Alternatives