College Essay: My Parents’ Sacrifice Makes Me Strong

After living in Texas briefly, my mom moved in with my aunt in Minnesota, where she helped raise my cousins while my aunt and uncle worked. My mom still glances to the building where she first lived. I think it’s amazing how she first moved here, she lived in a small apartment and now owns a house.

My dad’s family was poor. He dropped out of elementary school to work. My dad was the only son my grandpa had. My dad thought he was responsible to help his family out, so he decided to leave for Minnesota because of many work opportunities .

My parents met working in cleaning at the IDS C enter during night shifts. I am their only child, and their main priority was not leaving me alone while they worked. My mom left her cleaning job to work mornings at a warehouse. My dad continued his job in cleaning at night.

My dad would get me ready for school and walked me to the bus stop while waiting in the cold. When I arrived home from school, my dad had dinner prepared and the house cleaned. I would eat with him at the table while watching TV, but he left after to pick up my mom from work.

My mom would get home in the afternoon. Most memories of my mom are watching her lying down on the couch watching her n ovelas – S panish soap operas – a nd falling asleep in the living room. I knew her job was physically tiring, so I didn’t bother her.

Seeing my parents work hard and challenge Mexican customs influence my values today as a person. As a child, my dad cooked and cleaned, to help out my mom, which is rare in Mexican culture. Conservative Mexicans believe men are superior to women; women are seen as housewives who cook, clean and obey their husbands. My parents constantly tell me I should get an education to never depend on a man. My family challenged machismo , Mexican sexism, by creating their own values and future.

My parents encouraged me to, “ ponte las pilas ” in school, which translates to “put on your batteries” in English. It means that I should put in effort and work into achieving my goal. I was taught that school is the key object in life. I stay up late to complete all my homework assignments, because of this I miss a good amount of sleep, but I’m willing to put in effort to have good grades that will benefit me. I have softball practice right after school, so I try to do nearly all of my homework ahead of time, so I won’t end up behind.

My parents taught me to set high standards for myself. My school operates on a 4.0-scale. During lunch, my friends talked joyfully about earning a 3.25 on a test. When I earn less than a 4.25, I feel disappointed. My friends reacted with, “You should be happy. You’re extra . ” Hearing that phrase flashbacks to my parents seeing my grades. My mom would pressure me to do better when I don’t earn all 4.0s

Every once in awhile , I struggled with following their value of education. It can be difficult to balance school, sports and life. My parents think I’m too young to complain about life. They don’t think I’m tired, because I don’t physically work, but don’t understand that I’m mentally tired and stressed out. It’s hard for them to understand this because they didn’t have the experience of going to school.

The way I could thank my parents for their sacrifice is accomplishing their American dream by going to college and graduating to have a professional career. I visualize the day I graduate college with my degree, so my family celebrates by having a carne asada (BBQ) in the yard. All my friends, relatives, and family friends would be there to congratulate me on my accomplishments.

As teenagers, my parents worked hard manual labor jobs to be able to provide for themselves and their family. Both of them woke up early in the morning to head to work. Staying up late to earn extra cash. As teenagers, my parents tried going to school here in the U.S . but weren’t able to, so they continued to work. Early in the morning now, my dad arrives home from work at 2:30 a.m ., wakes up to drop me off at school around 7:30 a.m . , so I can focus on studying hard to earn good grades. My parents want me to stay in school and not prefer work to head on their same path as them. Their struggle influences me to have a good work ethic in school and go against the odds.

© 2024 ThreeSixty Journalism • Login

ThreeSixty Journalism,

a nonprofit program of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of St. Thomas, uses the principles of strong writing and reporting to help diverse Minnesota youth tell the stories of their lives and communities.

Home — Application Essay — National Universities — How Having Immigrant Parents Changed Me: Personal Experience

How Having Immigrant Parents Changed Me: Personal Experience

- University: Texas A&M University

About this sample

Words: 869 |

Published: Jul 18, 2018

Words: 869 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

In this essay, I will explore the profound impact of having immigrant parents on my upbringing and perspective. Growing up, I had the unique opportunity to bridge the gap between my life in the United States and the experiences of my parents in Belarus, a country with its own set of challenges and hardships. These contrasting worlds have shaped my values, work ethic, and resilience, ultimately influencing the person I have become today.

Say no to plagiarism.

Get a tailor-made essay on

'Why Violent Video Games Shouldn't Be Banned'?

6:00 AM, small industrial town of Zhodino, Belarus. Summer 2008. I reluctantly boarded the bus, immediately noticing that it was absolutely packed. The bus, of course, was to my grandmother’s dacha, a cottage where she grew and tended to what I have always considered to be an absurd amount of crops, all by herself. After standing cramped like sardines for an hour, and then walking along a muddy path for twenty minutes, we finally arrived at my grandparents’ dacha. I was absolutely exhausted, but we were just getting started. At any given moment in the next seven hours I was being forced to dig or pick some sort of crop out of the ground.

Through all of my tantrums and complaining that day, my grandmother continued working and just kept telling me to do the same. When 2 PM finally rolled around, I was so happy to be going back to her apartment that I found the energy to run through most of the muddy path. Once we got to the bus stop, however, I was devastated to learn that we were not going home, but to the local farmer’s market. My grandmother spent the next 2 hours selling the crops she had unearthed that day, while I was passed out with my face on the raggedy old tablecloth she used.

For my parents, that full day of manual labor was a very common way to spend their summer days growing up. Before they immigrated to the United States in 1998, they had grown up in Belarus, which was a part of Soviet Union at the time. Even as a self-reliant nation today, the country continues to struggle under a dictatorship; a relic of the totalitarian Past. Not quite North Korea, but with certain similarities. And while I was raised in a much more financially stable household in Texas, my parents helped me to understand how fortunate I was by bringing me back to their home country with them most summers growing up.

I have seen what it is like to stay in a country in crisis, and after every summer I have returned home to Texas with a more positive outlook on life. I’ve been able to encourage myself through even the most stressful points in my life by simply thinking about how much more serious my problems may be if my parents hadn’t worked as hard as they did to make it out of Belarus. If I hadn’t returned to Belarus every summer and seen how food prices were always rising and how my grandmother’s pension was always dropping, it is unlikely that I would be able to understand other people’s misfortunes and suffering as well as I am now. Because of these humbling experiences, I’ve spent a plentiful amount of time volunteering for CCA Food Pantry, the Texas Ramp Project, and the North Texas Food Bank.

Since my parents have always had a serious understanding of what can happen without self-sufficiency and hard work, I was raised somewhat differently than most of the kids around me were. While my some of my friends’ parents would essentially nanny them through many of their problems, I was taught from a very young age that I would have to take care of certain things on my own. When I was eight years old and told my dad I was interested in woodworking, he gave me a hammer, nails, and some wood and said “Build a table then.” When I told my mom I wanted to join my first basketball league when I was seven, she told me “That’s great, but you’ll have to sign up yourself, I’m very busy at work right now.”

Keep in mind: This is only a sample.

Get a custom paper now from our expert writers.

Events like these were clearly nowhere near traumatic, and my parents have always given me everything I’ve ever needed. However, they did help me to learn self-sufficiency and perseverance, because while I had never built anything in my life or used a computer for anything other than gaming, I had to figure these problems out on my own. Because of the way I was raised, I realized from a young age that complaining wouldn’t get me anywhere. Resiliency, however, would. I eventually built that table and figured out how to sign up for that league, and while the table only had one leg and I accidentally sent my registration to the YMCA in Arkansas, I learned through episodes like these that if I was dedicated enough, I could achieve my goals. Being raised by two immigrant parents has been very influential in my maturation. The values they have instilled in me, along with the perspective I’ve gained by visiting their old homes in Belarus, have made me a more determined and unselfish person. I would not be where I am today if it wasn’t for my unorthodox upbringing.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: National Universities

+ 128 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Are you interested in getting a customized paper?

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on National Universities

At 8:35 AM, on a Tuesday during the school year, November 29, 2011 to be exact, I not-so-vividly recall shuffling around under the covers as a young teenager often does after waking up in the morning and looking over at the [...]

There was one playground not too far from my grandparents' apartment in Cairo (the summer home of my childhood) where I wasn't treated like the quirky, abnormal kid that I was used to being. It wasn't your ideal picture of [...]

Florida State University offers an excellent program in statistics that has caught my attention. The reason why I am drawn to this program is that I have always been interested in the field of mathematics and how it applies to [...]

For more than three generations, my family has answered the call of elected public office. My father served in the State Legislature, my Grandfather and Great Grandfather as locally elected officials. Most teenagers my age have [...]

During a trip to the US, my father brought back a boxed set of The West Wing DVDs. While I planned to watch them during my school holiday as amusement, the show instead became an obsession and an education in itself. My [...]

They call it free falling for a reason. There’s something liberating that comes with taking the plunge, but that sense of freedom didn’t come easily for me. My sophomore year of high school, I joined the Durango High School’s [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Personal Narrative: My Immigrant Parents

There were three lessons that my immigrant parents ingrained in their first-generation children: Work hard, never give up, and most importantly, give back. Among other life lessons they taught us, these three were the basis for everything. It would be the basis that would and will define me as a person. My mother was a widow by the time she was in her mid-thirties with four children under the age of 16. It would have been easy to accept handouts and pity, but I witnessed her rise from tragedy, more determined than ever to provide every necessity that her children needed and wanted. As appreciative as I was when I was younger, I look back in total awe of her. Even though she worked 60-plus hours a week to make ends meet, she still told us that …show more content…

It wasn’t until our family moved into our own home that was my mother was diagnosed with Hepatitis C. My world came tumbling down and I vowed secretly that I would do everything I could to prolong my mother’s life. I poured myself into work, working 40-plus hours a week, looked for any doctor that would be willing to help her, researched insurance plans that wouldn’t cost a fortune for a pre-existing condition while still going to school. Needless to say, my grades suffered as I struggled to find the balance between aiding my mother and her condition, going to school full time, and working overtime. I came to a breaking point and I withdrew hours at school, choosing to work. Looking back, I would have done things differently, but I accomplished what I sought out to do: I was able to find insurance, put my mother on a drug regimen that suppresses the virus in her, and pay off our house in less than fifteen years. It is one of my greatest …show more content…

I started my path on becoming a teacher, but was turned to occupational therapy by an OT who saw potential in me; potential I didn’t know I possessed. I was apprehensive at first only because, like most people, I didn’t know what OT was. I was first exposed to it through my autistic cousin, sitting in on his therapy sessions. I was amazed at how the therapist was able to guide my cousin, teaching him skills and movements through simple puzzles and games I took for granted every day. I began doing more research and my fascination soon became my passion. I fully dedicated myself to school, cutting back on hours at work. My failure to commit myself early in my education is my biggest obstacle to date, but my C-average soon became a strong B in a few short semesters. Soon after, I found myself on the University of Houston – Downtown’s Dean’s List in the Spring of 2013 and graduated Fall 2013, majoring in Interdisciplinary Studies and a minor in English, something I thought would never

Personal Narrative: Coming From A Mexican Immigrant Family

Coming from a Mexican immigrant family I have learned to recognize since a very young age that because of the status that my parents are placed in they cannot pursue a better future like the one I want. I have been given the opportunity to challenge myself with obtaining a higher education than just high school itself. My parents have demonstrated to me through their hard work that I have to value this opportunity unless I want to end up with low paying job. My life long dedication comes from seeing my parents make sacrifices in order for my education to continue.

Personal Narrative : My Immigrant Story

Welcome. A single word on the carpet by the door greets me whenever I come home. There had been times where that one word made my heart beat and cry with joy. But not now, for many things changed through the years. Now when I look at this carpet, I instead question back: ‘Do you really mean that?’

Personal Narrative: Being A Daughter Of Immigrant Parents

Being a daughter of immigrant parents has never been easy here in America. Both my parents worked excessively hard to be financially stable. Unfortunately at the age of ten my life changed. I learned that my parents no longer loved each other. The arguing and fighting my parents had, only damaged me emotionally. I was too young to grasp the idea that my parents were separating which become one of the hardest times for my mom to maintain my siblings and I. Shortly after, I began attending church and fell in love with the idea of getting closer to God. Luckily, my life took an enormous turn the moment I gave my life to Christ. God has opened numerous opportunities for my education. I am proud of all the accomplishments I have achieved in high

Personal Narrative: My First Generation Immigrant

It is not uncommon to hear one recount their latest family reunion or trip with their cousins, but being a first generation immigrant, I sacrificed the luxury of taking my relatives for granted for the security of building a life in America. My parents, my brother, and I are the only ones in my family who live in the United States, thus a trip to India to visit my extended family after 4 years was an exciting yet overwhelming experience. Throughout the trip, I felt like a stranger in the country where I was born as so many things were unfamiliar, but there were a few places that reminded me of my childhood.

Personal Narrative: Growing Up With Two Immigrants

Growing up with two immigrant parents, me and my siblings were and still are their go to source when needing help translating something or talking to someone in the store or on the phone. Like the author Amy Tan, when my mother has a question about why her phone bill was higher than usual or needing help with a product at a store, we are her go to source. Although my parents spoke english fluently, their thick accents made it hard for people to understand them. They would not be taken as seriously when speaking with others as if their accents made them sound as if they were less educated not knowing they spoke over three languages.

Personal Narrative: My First Immigrant

With the settlement of first immagrants to America, this has been the phrase in which they preach. I seemed to those from an outside perspective of America, that this was the place to be. This was no exception for my grandfather. His valuable lessons of dedication, persistence and passion have shaped me into the person that I have become.

Personal Narrative: My Immigrant Perspective

I chose my immigrant participant from a personal perspective, yet not knowing much about him. Last year, my first year teaching, I had a little boy in my class that was Latino, very shy and quite. He struggled in reading and writing and after meeting with his parents and ESOL teacher several times, the decision was made to retain him in first grade. His parents, especially dad was hesitant about the decision, and began to tell small glimpses of how his son was very much like him, shy, and scared to reach out because of the language barrier. There was never much elaborated on, but I could tell that dad had possibly been in a similar situation before. This year, I was lucky enough to have this same child in my first grade class again. After receiving

Personal Narrative: Growing Up In The United States As An Immigrant

Growing up in the US as an immigrant, my childhood was a little different from most people’s. I faced many struggles due to the differences in cultures, social, and economics. However, I was able to overcome all those challenges and become a more humble, responsible, and determined individual because of my ability to adapt quickly, be compassionate, and stay goals-oriented.

Personal Narrative: My Life As An Immigrant

One person can have the power to change a community’s perspective or sharpen it. As a Latina and an immigrant, my family’s experience has taught me about the process of entering the United States and the complications that follow. Still, my comprehension of social issues developed further the day I met my brother’s friend and classmate, who followed my brother home, unannounced, on the bus. I will call him Eric, my brother’s friend and his family are Salvadorian undocumented immigrants who seek political asylum. Eric’s family consists of a younger and an older sibling, and his mother. The only source of income is what his mother, who does not speak English very well, makes. Lately, this is what keeps me up at night. Thoughts of this child and his family consume my mind while I brainstorm ways of helping. At a young age when their biggest concerns

Personal Narrative: Becoming An Immigrant

My father left my mother as a young immigrant, he left me at a young age, I only had my mother and my little sister. I couldn’t imagine the world without them, so when I discovered I could potentially lose my mother, I almost fell apart.

As I walked into the house, my parents were waiting for me in the living room. I did not know what was happening, but from the look in their eyes, I knew that was something wrong. My mother sat me down to tell me that my father had lost his business. The situation seemed so hectic; yet, the conversation felt like it lasted a lifetime. Finding out this news was detrimental to my family because my father had worked hard in America to build this business. I learned that my father had to give up his business and, as result my family had to start over, and find a new way to make a living.

Personal Narrative: I Am An Immigrant

I am an immigrant, originating from Ukraine. I moved here three years ago to take advantage of the “land of the free”. I had heard of the conscription under Russian imperial dictators, such as Tzar Nicolas, and Soviet despots, like Stalin. Fourcing an individual to perform a service, regardless of the cause, seems to be slavery to me. When I found that men in America must register for the draft, in my eyes, “the land of the free” became slightly less free. It is abhorrent that men may be required to enlist in the military, and equally so for women and therefore should not be tied to feredal grants.

Personal Narrative: My Immigrant

Looking back to the past, before I was born, I never really knew where my ancestors came from or why they even came here in the first place. It was never made a big deal in my family to talk about our history and the reasons why they came to American. So, I decided to do a little research and find out a little bit about myself, my culture, and my communication styles. I asked for a little bit of help from my grandmothers from each side of my family. I got an abundance of information that opened my eyes to a new past that I didn’t even know about.

Personal Narrative: My Life As A Mexican Immigrant

My parent’s struggles taught me to never accept defeat because there are endless possibilities for those who don’t give up. Their perseverance for a better life sparked a sense of determination in me that ignited a fuel for prosperity, and an optimism for bigger and better opportunities not only for me, but for my

Personal Narrative: My Parents In The United States

I have not seen my parents in three years. I came to the United States when I was eighteen to become an American chemical engineer. I have met new people in the new land and made friends with a few of them. The longer I am away from my parents and the more I interact with people, the more I realize my parents have a significant influence to shape who I am today. Looking back the time I was with my parents, I have found several odd things in my house that I did not notice when I was a kid. To many people, they probably think my parents are strange. However, when I have grown up and traveled around the world, I am astonished to realize those things resemble the beautiful personality of my parents.

Related Topics

- United States

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- Home Planet

- 2024 election

- Supreme Court

- TikTok’s fate

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

- Criminal Justice

My immigrant family achieved the American dream. Then I started to question it.

Share this story.

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: My immigrant family achieved the American dream. Then I started to question it.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/52625345/GettyImages_621767326.0.jpg)

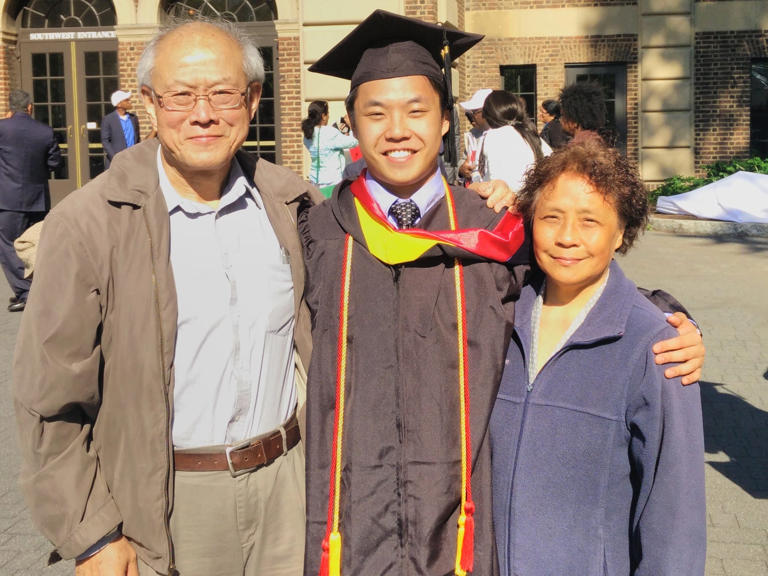

In summer 2007, I returned home from my freshman year at Brown University to the new house my family had just bought in Florida. It had a two-car garage. It had a pool. I was on track to becoming an Ivy League graduate, with opportunities no one else in my family had ever experienced. I stood in the middle of this house and burst into tears. I thought: We’ve made it.

That moment encapsulated what I had always thought of the “American dream.” My parents had come to this country from Mexico and Ecuador more than 30 years before, seeking better opportunities for themselves. They worked and saved for years to ensure my two brothers and I could receive a good education and a solid financial foundation as adults. Though I can’t remember them explaining the American dream to me explicitly, the messaging I had received by growing up in the United States made me know that coming home from my first semester at a prestigious university to a new house meant we had achieved it.

And yet, now six years out of college and nearly 10 years past that moment, I’ve begun questioning things I hadn’t before: Why did I “make it” while so many others haven’t? Was this conventional version of making it what I actually wanted? I’ve begun to realize that our society’s definition of making it comes with its own set of limitations and does not necessarily guarantee all that I originally assumed came with the American dream package.

I interviewed several friends from immigrant backgrounds who had also reflected on these questions after achieving the traditional definition of success in the United States. Looking back, there were several things we misunderstood about the American dream. Here are a few:

1) The American dream isn’t the result of hard work. It’s the result of hard work, luck, and opportunity.

Looking back, I can’t discount the sacrifices my family made to get where we are today. But I also can’t discount specific moments we had working in our favor. One example: my second-grade teacher, Ms. Weiland. A few months into the year, Ms. Weiland informed my parents about our school’s gifted program. Students tracked into this program in elementary school would usually end up in honors and Advanced Placement classes in high school — classes necessary for gaining admission into prestigious colleges.

My parents, unfamiliar with our education system, didn’t understand any of this. But Ms. Weiland went out of her way to explain it to them. She also persuaded school administrators to test me for entrance into the program, and with her support, I eventually earned a spot.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that Ms. Weiland’s persistence ultimately influenced my acceptance into Brown University. No matter how hard I worked or what grades I received, without gifted placement I could never have reached the academic classes necessary for an Ivy League school. Without that first opportunity given to me by Ms. Weiland, my entire educational trajectory would have changed.

The philosopher Seneca said, “Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity.” But in the United States, too often people work hard every day, and yet never receive the opportunities that I did — an opportunity as simple as a teacher advocating on their behalf. Statistically, students of color remain consistently undiscovered by teachers who often , intentionally or not, choose mostly white, high-income students to enter advanced or “gifted” programs , regardless of their qualifications. Upon entering college, I met several students from across the country who also remained stuck within their education system until a teacher helped them find a way out.

Research has proved that these inconsistencies in opportunity exist in almost every aspect of American life. Your race can determine whether you interact with police, whether you are allowed to buy a house , and even whether your doctor believes you are really in pain . Your gender can determine whether you receive funding for your startup or whether your attempts at professional networking are effective. Your "foreign-sounding" name can determine whether someone considers you qualified for a job. Your family’s income can determine the quality of your public school or your odds that your entrepreneurial project succeeds .

These opportunities make a difference. They have created a society where most every American is working hard and yet only a small segment are actually moving forward. Knowing all this, I am no longer naive enough to believe the American dream is possible for everyone who attempts it. The United States doesn’t lack people trying. What it lacks is an equal playing field of opportunity.

2) Accomplishing the American dream can be socially alienating

Throughout my life, my family and I knew this uncomfortable truth: To better our future, we would have to enter spaces that felt culturally and racially unfamiliar to us. When I was 4 years old, my parents moved our family to a predominantly white part of town, so I could attend the county’s best public schools. I was often one of the only students of color in my gifted and honors programs. This trend continued in college and afterward: As an English major, I was often the only person of color in my literature and creative writing classes. As a teacher, I was often one of few teachers of color at my school or in my teacher training programs.

While attending Brown, a student of color once told me: “Our education is really just a part of our gradual ascension into whiteness.” At the time I didn’t want to believe him, but I came to understand what he meant: Often, the unexpected price for academic success is cultural abandonment.

In a piece for the New York Times , Vicki Madden described how education can create this “tug of war in [your] soul”:

To stay four years and graduate, students have to come to terms with the unspoken transaction: exchanging your old world for a new world, one that doesn’t seem to value where you came from. … I was keen to exchange my Western hardscrabble life for the chance to be a New York City middle-class museum-goer. I’ve paid a price in estrangement from my own people, but I was willing. Not every 18-year-old will make that same choice, especially when race is factored in as well as class.

So many times throughout my life, I’ve come home from classes, sleepovers, dinner parties, and happy hours feeling the heaviness of this exchange. I’ve had to Google cultural symbols I hadn’t understood in these conversations (What is “Harper’s”? What is “après-ski”?). At the same time, I remember using academia jargon my family couldn’t understand either. At a Christmas party, a friend called me out for using “those big Ivy League words” in a conversation. My parents had trouble understanding how independent my lifestyle had become and kept remarking on how much I had changed. Studying abroad, moving across the country for internships, living alone far away from family after graduating — these were not choices my Latin American parents had seen many women make.

An official from Brown told the Boston Globe that similar dynamics existed with many first-generation college students she worked with: “Often, [these students] come to college thinking that they want to return home to their communities. But an Ivy League education puts them in a different place — their language is different, their appearance is different, and they don’t fit in at home anymore, either.”

A Haitian-American friend of mine from college agreed: “After going to college, interacting with family members becomes a conflicted zone. Now you’re the Ivy League cousin who speaks a certain way, and does things others don’t understand. It changes the dynamic in your family entirely.”

A Latina friend of mine from Oakland felt this when she got accepted to the University of Southern California. She was the first person from her to family to leave home to attend college, and her conservative extended family criticized her for leaving home before marriage.

“One night they sat me down, told me my conduct was shameful and was staining the reputation of the family,” she told me, “My family thought a woman leaving home had more to do with her promiscuity than her desire for an education. They told me, ‘You’re just going to Los Angeles so you can have the freedom to be with whatever guy you want.’ When I think about what was most hard about college, it wasn’t the academics. It was dealing with my family’s disapproval of my life.”

We don’t acknowledge that too often, achievement in the United States means this gradual isolation from the people we love most. By simply striving toward American success, many feel forced to make to make that choice.

3) The American dream makes us focus single-mindedly on wealth and prestige

When I spoke to an Asian-American friend from college, he told me, “In the Asian New Jersey community I grew up in, I was surrounded by parents and friends whose mentality was to get high SAT scores, go to a top college, and major in medicine, law, or investment banking. No one thought outside these rigid tracks.” When he entered Brown, he followed these expectations by starting as a premed, then switching his major to economics.

This pattern is common in the Ivy League: Studies show that Ivy League graduates gravitate toward jobs with high salaries or prestige to justify the work and money we put into obtaining an elite degree. As a child of immigrants, there’s even more pressure to believe this is the only choice.

Of course, financial considerations are necessary for survival in our society. And it’s healthy to consider wealth and prestige when making life decisions, particularly for those who come from backgrounds with less privilege. But to what extent has this concern become an unhealthy obsession? For those who have the privilege of living a life based on a different set of values, to what extent has the American dream mindset limited our idea of success?

The Harvard Business Review reported that over time, people from past generations have begun to redefine success. As they got older, factors like “family happiness,” “relationships,” “balancing life and work,” and “community service” became more important than job titles and salaries. The report quoted a man in his 50s who said he used to define success as “becoming a highly paid CEO.” Now he defines it as “striking a balance between work and family and giving back to society.”

While I spent high school and college focusing on achieving an Ivy League degree, and a prestigious job title afterward, I didn’t think about how other values mattered in my own notions of success. But after I took a “gap year” at 24 to travel, I realized that the way I’d defined the American dream was incomplete: It was not only about getting an education and a good job but also thinking about how my career choices contributed to my overall well-being. And it was about gaining experiences aside from my career, like travel . It was about making room for things like creativity, spirituality , and adventure when making important decisions in my life.

Courtney E. Martin addressed this in her TED talk called “The New Better Off,” where she said: “The biggest danger is not failing to achieve the American dream. The biggest danger is achieving a dream that you don't actually believe in.”

Those realizations ultimately led me to pursue my current work as a travel writer. Whenever I have the privilege to do so, I attempt what Martin calls “the harder, more interesting thing”: to “compose a life where what you do every single day, the people you give your best love and ingenuity and energy to, aligns as closely as possible with what you believe.”

4) Even if you achieve the American dream, that doesn’t necessarily mean other Americans will accept you

A few years ago, I was working on my laptop in a hotel lobby, waiting for reception to process my booking. I wore leather boots, jeans, and a peacoat. A guest of the hotel approached me and began shouting in slow English (as if I couldn’t understand otherwise) that he needed me to clean his room. I was 25, had an Ivy League degree, and had completed one of the most competitive programs for college graduates in the country. And yet still I was being confused for the maid.

I realized then that no matter how hard I played by the rules, some people would never see me as a person of academic and professional success. This, perhaps, is the most psychologically disheartening part of the American dream: Achieving it doesn’t necessarily mean we can “transcend” racial stereotypes about who we are.

It just takes one look at the rhetoric by current politicians to know that as first-generation Americans, we are still not seen as “American” as others. As so many cases have illustrated recently, no matter how much we focus on proving them wrong, negative perceptions from others will continue to challenge our sense of self-worth.

For black immigrants or children of immigrants, this exclusionary messaging is even more obvious. Kari Mugo, a writer who immigrated to the US from Kenya when she was 18, expressed to me the disappointment she has felt trying to feel welcomed here: “It’s really hard to make an argument for a place that doesn’t want you, and shows that every single day. It’s been 12 years since I came here, and each year I’m growing more and more disillusioned.”

I still cherish my college years, and still feel immensely proud to call myself an Ivy League graduate. I am humbled by my parents’ sacrifices that allowed me to live the comparatively privileged life I’ve had. I acknowledge that it is in part because of this privilege that I can offer a critique of the United States in the first place. My parents and other immigrant families who focused only on survival didn’t have the luxury of being critical.

Yet having that luxury, I think it’s important to vocalize that in the United States, living the dream is far more nuanced than we often make others believe. As Mugo told me, “My friends back in Kenya always receive the message that America is so great. But I always wonder why we don’t ever tell the people back home what it’s really like. We always give off the illusion that everything is fine, without also acknowledging the many ways life here is really, really hard.”

I deeply respect the choices my parents made, and I’m deeply grateful for the opportunities the United States provided. But at this point in my family’s journey, I am curious to see what happens when we begin exploring a different dream.

Amanda Machado is a writer, editor, content strategist , and facilitator who works with publications and nonprofits around the world. You can learn more about her work at her website .

First Person is Vox's home for compelling, provocative narrative essays. Do you have a story to share? Read our submission guidelines , and pitch us at [email protected] .

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In The Latest

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

So you’ve found research fraud. Now what?

How JoJo Siwa’s “rebrand” got so messy

Student protests are testing US colleges’ commitment to free speech

Is Fallout a warning for our future? A global catastrophic risk expert weighs in.

Canada’s polite Trumpism

Mass graves at two hospitals are the latest horrors from Gaza

How to Write a Standout College Essay about Immigrant Parents

Kate Sliunkova

AdmitYogi, Stanford MBA & MA in Education

If you're a high school student, chances are you've been asked to write an essay before. Writing about your immigrant parents can be a daunting task, but it can also be a beautiful opportunity to share your unique perspective. With the right strategies and mindset, you can craft an essay that not only showcases your writing skills but also honors the sacrifices and experiences of your immigrant parents.

Acknowledge the Significance of Your Parents' Journey

Before delving into writing your essay, it's crucial to acknowledge and appreciate the significance of your parents' immigration journey. Recognize the sacrifices they made, leaving behind their home country, family, and familiar surroundings, to provide a better life for you and your family. This appreciation will help you approach your essay with a deeper understanding and empathy. To explore successful college essays that highlight the importance of family sacrifices, visit AdmitYogi for inspiring examples.

Use Their Story as a Springboard for Self-Reflection

Your parents' immigration story serves as a powerful springboard for self-reflection. Reflect on the impact their journey has had on you - your identity, values, and aspirations. Consider how growing up in a multicultural household has shaped your worldview and influenced the choices you've made. This self-reflection allows you to connect your personal growth to your parents' experiences, providing a rich and compelling narrative. AdmitYogi can provide additional guidance on how to effectively incorporate self-reflection into your essay.

Choose a Meaningful Essay Topic

Selecting the right essay topic is crucial to capturing the attention of college admissions officers. Instead of focusing solely on your parents' story, choose a topic that reflects your own experiences and values, while weaving in elements of their journey. For example, you can explore moments where you grappled with language barriers and how those challenges fostered your determination to excel academically and embrace diverse perspectives.

Consider discussing the cultural differences you navigated while transitioning to the United States. Highlight the lessons you've learned about cultural diversity and your ability to adapt and thrive in new environments. This demonstrates your resilience and adaptability, qualities that colleges value in their applicants.

Infuse Your Essay with Personal Anecdotes

To make your essay engaging and memorable, infuse it with personal anecdotes that illustrate key moments or lessons from your own journey. Share specific stories that demonstrate your growth, resilience, and unique perspective. For instance, you can write about a time when you bridged a cultural gap between your parents' native traditions and American customs, showcasing your ability to navigate cultural complexities with sensitivity and openness.

By incorporating personal anecdotes, you showcase your individual experiences and emphasize how you have been shaped by your parents' immigration story, while maintaining the focus on you.

Reflect on the Intersection of Your Identity and Values

Colleges are interested in understanding who you are as an individual and the values you hold dear. Reflect on how your parents' immigration journey has influenced your own identity and values. Discuss the lessons you've learned about perseverance, determination, and the importance of education.

Highlight the ways in which your parents' sacrifices have motivated you to seize educational opportunities and strive for excellence. Emphasize how their story has instilled in you a deep appreciation for the value of education and the pursuit of knowledge.

Showcase Your Personal Growth and Aspirations

A compelling college essay should demonstrate personal growth and aspirations. Reflect on how your parents' experiences have influenced your own aspirations and goals for the future. Discuss the career paths, community involvement, or social initiatives that you are passionate about, and how they align with your values and the experiences you've had growing up as a child of immigrants.

Craft a Narrative That Captivates Admissions Officers

To make your essay truly standout, craft a narrative that captivates admissions officers. Start with a powerful and attention-grabbing opening. This could be a personal anecdote, a thought-provoking question, or a vivid description that draws the reader in from the very beginning.

Throughout your essay, use descriptive language and storytelling techniques to paint a vivid picture of your experiences and the impact of your parents' journey on your life. Engage the reader's senses and emotions, allowing them to connect with your story on a deeper level.

Writing a college application essay about your immigrant parents is an opportunity to celebrate your unique perspective and honor their experiences. By focusing on you and infusing your personal growth, values, and aspirations into the essay, you create a compelling narrative that highlights your individuality.

Remember to reflect on the intersection of your identity and values, choose a meaningful topic, and craft a narrative that captivates admissions officers. AdmitYogi , a trusted resource for successful college essays, offers a wealth of examples and guidance to help you throughout your writing journey. With these strategies and the support of AdmitYogi, you can write a standout essay that makes colleges eager to admit you and the incredible journey you represent.

Read applications

Read the essays, activities, and awards that got them in. Read one for free !

Yale (+ 20 colleges)

Indiana Vargas

Harvard (+ 14 colleges)

Quincy Johnson

MIT (+ 3 colleges)

Related articles

Discover Extracurricular Activites at Columbia University

Dive into the dynamic world of Columbia University's extracurricular activities, where academia meets passion and individual growth is fostered beyond the classroom. This comprehensive guide uncovers the top extracurriculars at Columbia, featuring a myriad of clubs, organizations, and initiatives. Whether it's honing your leadership skills, engaging in community service, indulging in creative endeavors, or nurturing entrepreneurial ideas, there's a platform for everyone.

What Are the Admission Requirements for Harvard University?

Harvard University is the world’s most selective school. In this article, we discuss their admissions requirements and how you can meet them!

Now I understand the sacrifices made by my immigrant parents

This article was published more than 2 years ago. Some information may no longer be current.

First Person is a daily personal piece submitted by readers. Have a story to tell? See our guidelines at tgam.ca/essayguide .

Illustration by Rachel Wada

I have a confession. Despite the fact that I, too, lived over a convenience store run by my immigrant parents, I have never watched an episode of Kim’s Convenience . I’ve heard the show is incredibly well written and witty, but in all honesty I was unsure about how I would feel watching the similarities of my childhood reality played out in a sitcom.

My parents immigrated to Canada when my sister and I were 6 and 3, respectively. They left their professional jobs behind in Taiwan, in addition to their families and friends, to give us “the best opportunities in life,” as we so frequently heard growing up. Now, raising my own three children, in significantly more privileged circumstances, I am at a crossroads – how do I give them what they need and foster their independence, yet still ensure that they live their lives with empathy and gratitude?

My father became an entrepreneur out of sheer necessity to secure a roof over our heads. With limited English skills, employment options were non-existent. They spent their savings on the purchase of a small convenience store, which we also lived above, as many families did then and continue to do so now. My mother, a former midwife and nurse, spent much of our childhood learning to speak English while being a cashier at our quaint neighbourhood corner store. I have many memories of her playing a role similar to a confused Vanna White, but instead of turning letters on Wheel of Fortune, Mom was trying to decipher what brand of cigarettes a customer wanted from behind the counter.

They worked seven days a week, 12 to 14 hours a day, often longer. As a child, I never understood why they needed to work so much or why no one ever volunteered to bake cookies or chaperone school field trips. One day, my fourth-grade teacher called my mother in to speak with her. During a class assignment, I had written a story about how “my parents love money more than they love me.” I can only imagine the embarrassment and stabbing pain my mother felt during that talk. I wish I could go back in time.

We attended a public school out of our district that comprised mostly of white children from well-to-do families. My father would pick us up and drop us off in our “secret” location a block away from the school so that the other children would not see us coming out of a clunky old cargo van, only meant for produce and non-perishables. In hindsight, I’m not sure if he was trying to hide his embarrassment or ours, perhaps a little bit of both.

Nevertheless, my parents did their best to shelter us from their daily struggles. While other kids went on ski trips and spring break vacations, my sister and I spent our free time together. Summers were completely unsupervised, consisting of entire days spent swimming in public pools, biking around the city and reading in the library: Judy Blume and Beverly Cleary, what would we have done without you?

We became experts at making our own meals, a rotating menu of Chef Boyardee, TV dinners and Lipton Sidekicks noodles. We ate our food directly from the pots that we cooked them in, and in front of the TV, watching our favourite shows. We were latch-key kids. My key was tied directly around my neck, never ever to be removed.

We used the aisles that were full of groceries as our personal playground – I’m still convinced that there are few things more fun to a child than stocking shelves or scanning lottery tickets. We had first access to the latest issues of Mad Magazine and Archie comics, expertly reading them without leaving creases.

At Christmastime, gifts were often old items around the house, wrapped in colourful newsprint. My mother was the original “zero waster.” We participated in the Inner City Angels after-school programs provided by the city. We made toys out of discarded boxes – I was so pleased that the screen of my cardboard computer “moved” by turning a roll of paper towel inside. As much as we were without, we never felt it. We were, mostly, happy kids.

People say that the world was easier back then, that it was a better place, that things are different now. In retrospect, I’m not sure if that’s true, especially for children of immigrant families. We were just kids back then, and if you had any semblance of good parents, they simply did their best at making you feel like the world was a great place.

I often find myself in awe of the courage my parents must have had to embark on their journey into so many unknowns. Their struggles motivated me to do well in school, appreciate the value of a hard-earned dollar and, most importantly, to respect others no matter what our differences. In today’s heightened climate, I believe that this has been their greatest gift.

My children are growing up with a basement full of toys, many of which bring them no more than five minutes of joy. I want them to realize the privileges and opportunities given to them that many children do without, as is the wish of every generation, and the generation before them.

As my parents did, I will try my best to expect more from them, to make them appreciate their circumstances in a world that can seem unforgiving. I want them to be curious about how others live and understand that our way of life is not the only way of life. To embrace change and overcome challenges with resilience, not fear, just as their grandparents had. And no matter what their struggles, there is always room to lend a helping hand to someone less fortunate.

To many, my childhood probably seems quite unremarkable, but to me it was a time when optimism, hope and determination collided. A moment of sweet nostalgia, when our family had no one but ourselves to lean on and that was all that mattered. Us against the world. Perhaps it’s time for me to grab a bowl of popcorn, put up my feet and find the first episode of Kim’s Convenience .

Wan Lu lives in Toronto

Sign up for the weekly Parenting & Relationships newsletter for news and advice to help you be a better parent, partner, friend, family member or colleague.

Report an editorial error

Report a technical issue

Editorial code of conduct

Follow related authors and topics

- Family Follow You must be logged in to follow. Log In Create free account

- Parent Follow You must be logged in to follow. Log In Create free account

- School Follow You must be logged in to follow. Log In Create free account

Authors and topics you follow will be added to your personal news feed in Following .

Interact with The Globe

Growing Up in America With Immigrant Parents

I wrote about how my parents taught me to love who I am by being true to myself.

Being Assyrian has always been a huge part of my identity. As a child I felt so embarrassed to be who I am. No one had ever taught me to feel that way, I just didn't like how different my life seemed to be, compared to the other kids from my school. I had a unibrow and I had to take ESL classes because I was raised learning a mix of Aramaic and English. I refused to speak Aramaic publically. I was so ashamed of all of these things for some reason. I just wanted to be like the other kids at my school, blonde hair and blue eyes with a “normal” name. I hated my brown hair, brown eyes, my unibrow, and my “odd” name (Amena).

As I grew older, I started to become more accepting towards my background. This started happening around middle school age. I realized that there was no reason for me to be ashamed. I still felt different though. No matter how much I adapted I was still being raised differently from everyone else. My parents were always more strict that the others. They wouldn't let me hangout with certain people, I was never allowed to go to sleepovers, I couldn't wear certain clothes because they were “too revealing” even if everyone else in my grade was allowed to. I think that these are just things that you have to deal with when you have Middle Eastern parents. Things that were so normal for every other kid seemed to be so unbelievably offensive to my parents. I used to think it was so frustrating to deal with this.

To this day I still struggle with their grip. I can sometimes understand and appreciate why they raised me this way. As immigrants in America they dealt with a lot of the same feelings as I felt when I was younger. They struggled with not fitting in as a child just like me. When my mother's family moved here she was only a year old. She was raised in Davisburg Pennsylvania, she didn't have anyone to relate to around her other than her siblings. She had it so much worse than I did but today she loves being who she is. My dad moved to America when he was nine. He was raised in Detroit Michigan and in attempt to fit in he had to sacrifice some of his identity. Today I see him as the one of the most confident, down to earth people on this planet. He always stresses to me that I couldn't make a bigger mistake that being fake with myself. I think that all this time my parents were trying to point me in that direction. They wanted me to love who I am. They didn't want me to try so hard to be something i'm not just because I wanted to blend in. Instead they taught me how to stay true to myself and how to be comfortable in my own skin

Although it was frustrating at times I think overall it benefited me to be raised this way. I learned to do what's best for myself and have good judgment. They taught me to be comfortable in my own skin and put myself first. They taught me that no ones opinion matters except my own. Here in America you are able to do almost anything you'd want as long as you give it your all. Being true to myself is the only way for me identify my dreams. My parents wanted to make sure that I had my priorities straight so that I can focus on what's important.

It's ironic how I learned one of the most important American values from my immigrant parents. I thought this whole time that their “Middle Eastern morals” would separate me from everyone else but really they were what made me feel comfortable with myself now. They really have taught me so much about how to live a good, happy, healthy, American life! Today I live to please myself and the ones I love only. I know now that I don’t have to attempt to make everyone like me. I do what I please while still being reasonable and respectful. The only person really judging me is myself. I live by these morals and i couldn't be any more stress free.

- Written by Amena

- From Royal Oak High School

- In Michigan

- Group 7 Created with Sketch Beta. Upvote

- immigration

- Report a problem

Royal Oak High School Ready for Fun

ELA 11 6th Hour

More responses from Ready for Fun

More responses from royal oak high school, more responses from michigan, more responses from "division", "dream", "immigration", and "love ".

I am a Latino yet not an immigrant, but my family story helped me understand their journey

I recognize that i’m seeing myself through my stepfather's eyes. this recognition also brings me closer to the latino immigrant experience..

Benigno Trigo is the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Chair in the Humanities, Spanish and Portuguese College of Arts and Science at Vanderbilt University.

Vanderbilt’s new semester has begun. I teach a class on the Latino Immigrant Experience. Being from Puerto Rico (an unincorporated territory of the United States with a strong sense of its “national” identity), and being a U.S. citizen, I feel awkward, a fish out of water, leading my students through the assignments that elaborate on the experience of the immigrant.

I came to the mainland for college 45 years ago, but I don’t consider myself an immigrant.

On my first day of class, I presented and discussed the latest book by the Pulitzer Prize writer Héctor Tobar: “Our Migrant Souls: A Meditation on Race and the Meanings and Myths of ‘Latino’ (2023).”

It’s a book of personal essays that begins with a photograph of Tobar’s mother holding him as a baby. It’s 1954. She’s 20 years old, dressed simply but elegantly, her hair carefully set. Tobar tells us that she’s wearing a faux pearl necklace. In her arms, she cradles her sleeping baby, all dressed in white. They sit in front of the Griffith Observatory in California.

The picture is a figure for the main argument of the book, which is that the memories that migrants carry, float in dreamlike waters until they are anchored in history. “We arrived here like dandelion seeds, floating through the air, reaching firm ground by the blessing of God,” writes one of Tobar’s students.

Tobar calls the memories “stories of beginnings,” and they make migrants resilient. But they also hide a history of struggle and violence that needs to be uncovered to make the ground more solid for the next generation.

Another column by Benigno Trigo: Supreme Court knew that racial diversity is a matter of 'national security'

Héctor Tobar's lessons come alive in a photograph of my mother and me

In his book, Tobar lays this groundwork. He contextualizes the photograph, setting it against the history of violence in Guatemala. This violence drove his parents to the United States, and instilled in them a fearlessness and a youthful drive to make it their new country.

His father embraced the modern technology of the color camera. He framed their beginnings with a modern observatory. He tapped the scientific power of the country, whose government upended their lives. The democratically elected president of Guatemala was deposed by a coup, supported by the CIA.

To illustrate Tobar’s point, I searched my personal archive and found a picture of myself at 18 years old, as a student in a college in New England. It’s 1980. I’m almost recumbent on a wooden bench, on the campus’ green. Framed by a New England brick building, with austere white columns and a bell tower.

My mother sits behind me. She holds me, as if I was still her baby. We both look straight at the camera. I’ve always thought of this picture as a trace of the beginnings of my life in the United States.

While my stepfather is no longer in my life, I feel closer to him now

In class, my students ask me how I feel when I look at this picture now, and I confess to them that the book by Tobar has made me look at it differently. It’s made me think of my stepfather, Jorge, who stood behind the camera. He was a struggling writer from Mexico who had married my mother five years prior.

They tried to make a go of it in Mexico, but returned to the U.S. where they settled. Their journey was partly the result of Cold War politics in Puerto Rico, of my mother’s struggle for independence, and of both their efforts to become writers against all odds.

I told my students that I now realize that the photograph is in part a message from my stepfather. It’s a testament to his struggles. It was his attempt to document a rebirth, a new family, in the United States.

My mother and my stepfather divorced, and I never saw him again. But Tobar has made me see that I’m closer to Jorge than I thought.

I recognize that I’m seeing myself through his eyes. And this recognition also brings me closer to the Latino immigrant experience.

Raised By Immigrant Parents: First Generation Mental Health

What's your struggle?

Immigrant parents often teach only what they’re taught. So how can their first generation children feel seen and supported in their mental health struggles?

Being raised by immigrant parents can come with numerous advantages. Our families are tight-knit; we’re connected to our roots; and we receive exposure to multiple cultural perspectives. This kind of background enriches kids’ lives.

In some circumstances, however, being first generation creates mental health hurdles. Our parents have high expectations of success for us. But many of our parents simply haven’t engaged with their own emotions, and don’t see why we have to address them. We can’t ignore the mental health challenges specific to being a child of immigrants–many of which come from avoiding emotional talk altogether.

What’s it like to be raised by immigrant parents?

Immigrant households tend to emphasize the importance of family, cultural connectivity, and religious heritage–all of which can bolster mental health. Having a clear cultural background helps define your identity, and helps you connect with others who share the same heritage. Being raised by immigrants, in some ways, helps you to stand out in a world of conformity, bringing important differences to the table.

But while all of these qualities are positive, some traditional values can negatively impact a young adult’s mind. Some emotionally straining traditions include strict discipline, limited autonomy, and academic or financial pressure. The increased expectations of first generation kids, combined with our parents’ reluctance to address mental health, can set us up for major emotional struggle.

Controlling behavior

Controllingness is a negative trait common to immigrant parents that hurts a child’s development. Take a couple examples from my own childhood: I wasn’t allowed to have a sleepover with anyone as a child. I also never attended anyone’s birthday party because my parents didn’t know the other child’s family, and didn’t want to interact. I understand that my parents were being protective, but I know I missed out on key childhood experiences.

This type of controlling behavior can extend past childhood, into young adulthood, too. Traditionally, young adults in a first generation immigrant household only leave the house to get married. However, a new generation of college students has been pushing the limits on autonomy and independent living. We’ve begun to set our own path, which, in a way, threatens tradition.

When I moved away for college, my parents wanted me to come home every weekend. I understood that I was the first to leave home for reasons other than marriage, but to come home every single weekend was a major demand on my newfound freedom.

Limited autonomy

Limiting autonomy is another normalized negative value common within immigrant communities. Control and limited autonomy go hand in hand. For example, when I turned 16 and got my license, my mom started tracking my phone. Sure, I got a little bit more freedom, but it soon turned to paranoia because I felt my parents watching my every move. Loss of autonomy like this can lead to to depression and loss of identity.

Academic pressure

Academic pressures include pushing success onto the children of the family. As the daughter of immigrants, I understand the sacrifices behind my parents’ story; perhaps a little too well, in a way that induces guilt and pressure.

They have told me repeatedly that my education and success is the only way out of poverty–the same poverty they escaped from in their home country. Their wellbeing is on my back since their sacrifice, in theory, laid the foundation for my success.

The education systems in our parents’ home countries are often not the best in the world, at least in my family’s experience. Instead of receiving a proper education, immigrant parents often began work at a young age in order to survive.

Therefore, education is seen as the way out for the children of immigrants. My parents never directly pressured me, but I understood their expectations. The dependence on our success leads to a strain on first-generation American students. Due to our parents’ hard work, we have the privilege to be able to attend higher education institutions. Even if it doesn’t feel like the right path, we feel pressured to get the education our immigrant parents always imagined for us.

High expectations and fear of failure

My parents look to me to succeed, which adds an additional pressure on top of maintaining mental health and having a healthy social lifestyle.

As we children of immigrants grow older, we begin to fear our parents’ disappointment. We begin to fear failure. You might have the intrinsic motivation to succeed, but knowing that your parents’ future relies on your success has can send you into a depressive episode or worse.

As first-generation Americans and first-generation students, there is no room for error. We cannot afford to fail. Our parents’ stories, their struggles, their sacrifices have given us incredible opportunities, and immense expectations to live up to.

Clashing expectations from family and mainstream culture

Many immigrants’ backstories consist of having to work from a young age in order to make a sustainable living in their new country. Thus, generational differences between immigrant parents and their children are significant. First-generation Americans grow up in a completely different environment and society than their parents did. There are different norms which immigrant parents aren’t aware of, or don’t care about.

For example: the normal American teenage experience is something our immigrant parents were never introduced to. Immigrant parents tend to lack familiarity with the typical experiences of a high-schooler here. American standards can even clash with traditional norms, especially when it comes to the treatment of daughters versus sons.

Gender-based double standards

First generation hispanic households tend to be more strict with the daughters of the household in contrast with the sons. Treatment of daughters tends to be more protective, strict, and controlling. The difference between this reality at home and mainstream assumptions underlie deep emotional struggle for daughters of immigrants. We don’t always have the same freedom as our peers, and comparison highlights the pain in that difference.

Living in the constant clash between cultures is an exhausting experience. From academic pressures to dissonant cultural values, the mental strain on first-generation Americans and students is a significant one.

How do immigrant parents see mental health?

Many people who come from an immigrant family recognize that parents tend to turn a blind eye to the negative values embedded in their culture. We tend to highlight the positives and hide the negatives, even behind closed doors, within our families. But when it comes to mental health, we desperately need openness.

Due to the lack of awareness among immigrant parents, they may see depressive symptoms and mislabel them. They may call your symptoms “laziness” and dismiss the struggle. In their eyes, there’s no room for depression. The values they grew up with never let them consider what “mental health” really means.

That brings up another unnamed pressure put on the first-generation Americans: to educate our immigrant parents on what our unimagined struggles consist of.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: immigrant edition

One concept I’ve personally thought about and have connected to my immigrant parents is Maslow’s hierarchy of needs . This concept depicts the different levels of human needs, and the idea is that you can’t address higher-level needs before meeting the more basic ones.

When immigrant parents arrive in a new country, their struggle revolves around meeting the most basic of needs. They work hard, deny themselves comforts, to put food on the table and pay rent. In trying to secure these foundational survival needs, their emotional needs became low-priority. All of their hard work and sacrifice was needed secure the bottom of Maslow’s pyramid.

Parenting style

Where do we, children, fall into this picture? Our parents covered an important level of basic needs for us, and now, we have the ability to grow and strive for self-actualization and self-awareness. Since they could not satisfy this level of emotional need, themselves, the lack of emotional fulfillment translates into their parenting styles.

They may experience depression symptoms, but they probably aren’t cognizant enough to realize their own mental health struggles. They won’t make a bridge towards an actual solution. They’ll only teach what they have been taught. Repression and moving on without healing is an example of the way that immigrant parents react to mental health struggles.

This cycle of generational repression is another negative emotional value within the Hispanic/Latinx community. Families don’t seem to have a way to communicate emotional needs. We don’t talk about it. We let it happen until the need to talk it out is gone. This cycle can lead to serious problems in a family’s dynamic; parents get involved once it is too late and the child’s mental state has worsened.

How do I start the conversation with my immigrant parents about mental health?

First, you have to work up the courage and patience to gain their understanding. This is a serious topic, even though immigrant parents seem to dismiss it often.

After working yourself up to start the conversation…

Lay out points about what depression is and the symptoms that accompany it.

What is depression?

Depression varies from person to person. Different symptoms may arise differently. You might experience a single depressive episode or suffer from chronic, clinical depression. One person’s depression may leave them fatigued and hopeless, while another’s drives them to keep busy to ignore the pain. Again, symptoms vary.

Signs of depression include but are not limited to:

- Changes in sleep

- Changes in appetite

- Lack of concentration

- Loss of energy

- Hopelessness or guilty thoughts

- Lack of interest in activities

Tell them how depression has affected your life…

Talk about which symptoms have been prominent in your experience. Some examples can include:

- Not wanting to go to school

- Not wanting to eat regularly

- Struggling to maintain a daily routine

- Struggling to get out of bed

Show them you’re not alone in your struggle…

Although the focus should be about your own struggles, it is sometimes easier to understand a new concept when it’s related to a larger population. For example…

- List statistics relating to your community’s mental health

- Do a little bit of research about your community’s mental health

- For example: In a study, it was found that U.S. born Latinos were at a higher risk of depressive episodes than those who immigrated to the U.S

Introduce the differences brought on by culture and society…

There is an obvious difference in societal upbringing from your parents generation to yours.

- There are different expectations.

- Although you are from a cultured household, American society has different norms that you experience no matter how traditional you may be

- Different norms bring up identity issues, which may lead to a larger problem

Are there any potential ways your family contributes to your mental health?

The pressure to succeed is a huge weight to carry, but think about the other causes. What have your parents gone through that blurs their way of seeing the importance of mental health? What behaviors of theirs contribute most to your wellbeing (or lack thereof)?

Ask for what you want and need

Think about solutions to what you’re going through…

- Family support and understanding

- Greater freedom and autonomy

- Professional help including therapy

If you can’t make them see your struggle….

Seek help. Help doesn’t always have to be therapy. Finding someone who understands your struggle can be a useful way to air grievances. Whether it be a friend, a mentor or a sibling, it’s important to find someone who can help ease emotions.

Slip in statements about your feelings. Depression and mental health in general can be a very hard topic to speak about. If over time, parents begin to see a negative pattern, they’ll be sure to bring it up because it should concern them.

Understand their struggles. Immigrants have often had a difficult childhood of their own. They might not be able to understand your struggles if they never had theirs addressed either.

This article is part of Supportiv’s Amplify article collection .

Read more on, similar articles, i hate myself: beat low self esteem + feeling broken, when model minority asian stereotypes define your identity, scorned for seeking help as a filipino american, mixed race mental health: thinking in brown and white, let's start the conversation.

- Conversational Arc

- Data & Ethics

- Supporting Science

- Tech & Data

- Testimonials

- Versus Competitors

- Resource Library

- Behavioral Health / EAP

- Medicare / Seniors

- Military / Veterans

- Population Health

- Public Sector

- News & Updates

- IP Licensing

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

© 2024 Supportiv. All rights reserved.

Supportiv does not offer advice, diagnosis, treatment or crisis counseling. Peer support is not a replacement for therapy. Please consult with a doctor or licensed counselor for professional mental health assistance.

Supportiv products and services are covered by one or more US Patents No. US11368423B1 and US11468133B1.

For anonymous peer-to-peer support, try a chat .

For organizations, use this form or email us at [email protected] . Our team will be happy to assist you!

- Zoom Demo or Meeting

- 1,000 - 5,000

- 5,001 - 20,000

- 20,001 - 75,000

By sending you accept our Privacy Policy

Find anything you save across the site in your account

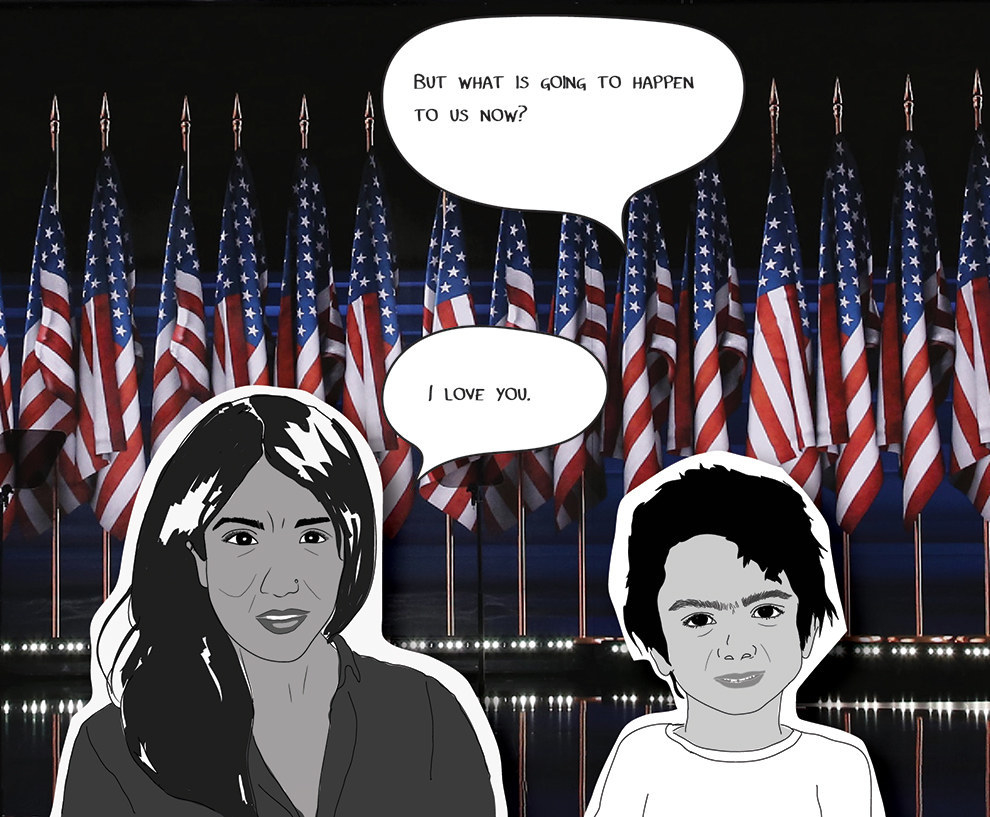

How Immigrant Parents Say “I Love You”

By Meghana Indurti

After working a hundred hours a week on top of navigating a new culture and country, immigrant parents may not always have the time or the energy to share Hallmark aphorisms. But, if they love you, these are the ways they’ll let you know.

Silence A picture is worth a thousand words, but silence from an immigrant parent after you’ve completed a task is worth a million. It means that you didn’t do anything wrong—yet! Now go clean the garage; someone is coming over for lunch in sixteen weeks.