- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

Data are from the 2018 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses.

eTable. Top 5 Reasons for Leaving Job and Considering Leaving Job by Respondents, 2018 National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses

- Error in Sample Sizes JAMA Network Open Correction March 16, 2021

- Error in Funding/Support JAMA Network Open Correction April 25, 2023

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Shah MK , Gandrakota N , Cimiotti JP , Ghose N , Moore M , Ali MK. Prevalence of and Factors Associated With Nurse Burnout in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2036469. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36469

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Prevalence of and Factors Associated With Nurse Burnout in the US

- 1 Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia

- 2 Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia

- 3 Department of Global Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia

- Correction Error in Sample Sizes JAMA Network Open

- Correction Error in Funding/Support JAMA Network Open

Question What were the most recent US national estimates of nurse burnout and associated factors that may put nurses at risk for burnout?

Findings This secondary analysis of cross-sectional survey data from more than 50 000 US registered nurses (representing more than 3.9 million nurses nationally) found that among nurses who reported leaving their current employment (9.5% of sample), 31.5% reported leaving because of burnout in 2018. The hospital setting and working more than 20 hours per week were associated with greater odds of burnout.

Meaning With increasing demands placed on frontline nurses during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, these findings suggest an urgent need for solutions to address burnout among nurses.

Importance Clinician burnout is a major risk to the health of the US. Nurses make up most of the health care workforce, and estimating nursing burnout and associated factors is vital for addressing the causes of burnout.

Objective To measure rates of nurse burnout and examine factors associated with leaving or considering leaving employment owing to burnout.

Design, Setting, and Participants This secondary analysis used cross-sectional survey data collected from April 30 to October 12, 2018, in the National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses in the US. All nurses who responded were included (N = 50 273). Data were analyzed from June 5 to October 1, 2020.

Exposures Age, sex, race and ethnicity categorized by self-reported survey question, household income, and geographic region. Data were stratified by workplace setting, hours worked, and dominant function (direct patient care, other function, no dominant function) at work.

Main Outcomes and Measures The primary outcomes were the likelihood of leaving employment in the last year owing to burnout or considering leaving employment owing to burnout.

Results The weighted sample of 50 273 respondents (representing 3 957 661 nurses nationally) was predominantly female (90.4%) and White (80.7%); the mean (SD) age was 48.7 (0.04) years. Among nurses who reported leaving their job in 2017 (n = 418 769), 31.5% reported burnout as a reason, with lower proportions of nurses reporting burnout in the West (16.6%) and higher proportions in the Southeast (30.0%). Compared with working less than 20 h/wk, nurses who worked more than 40 h/wk had a higher likelihood identifying burnout as a reason they left their job (odds ratio, 3.28; 95% CI, 1.61-6.67). Respondents who reported leaving or considering leaving their job owing to burnout reported a stressful work environment (68.6% and 59.5%, respectively) and inadequate staffing (63.0% and 60.9%, respectively).

Conclusions and Relevance These findings suggest that burnout is a significant problem among US nurses who leave their job or consider leaving their job. Health systems should focus on implementing known strategies to alleviate burnout, including adequate nurse staffing and limiting the number of hours worked per shift.

Clinician burnout is a threat to US health and health care. 1 At more than 6 million in 2019, 2 nurses are the largest segment of our health care workforce, making up nearly 30% of hospital employment nationwide. 3 Nurses are a critical group of clinicians with diverse skills, such as health promotion, disease prevention, and direct treatment. As the workloads on health care systems and clinicians have grown, so have the demands placed on nurses, negatively affecting the nursing work environment. When combined with the ever-growing stress associated with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, this situation could leave the US with an unstable nurse workforce for years to come. Given their far-ranging skill set, importance in the care team, and proportion of the health care workforce, it is imperative that we better understand job-related outcomes and the factors that contribute to burnout in nurses nationwide.

Demanding workloads and aspects of the work environment, such as poor staffing ratios, lack of communication between physicians and nurses, and lack of organizational leadership within working environments for nurses, are known to be associated with burnout in nurses. 4 , 5 However, few, if any, recent national estimates of nurse burnout and contributing factors exist. We used the most recent nationally representative nurse survey data to characterize burnout in the nurse workforce before COVID-19. Specifically, we examined to what extent aspects of the work environment resulted in nurses leaving the workforce and the factors associated with nurses’ intention to leave their jobs and the nursing profession.

We used data from the 2018 US Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Resources and Service Administration National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses (NSSRN), a nationally representative anonymous sample of registered nurses in the US. The weighted response rate for the 2018 NNRSN is estimated at 49.0%. 6 Details on sampling frame, selection, and noninterview adjustments are described elsewhere. 7 Weighted estimates generalize to state and national nursing populations. 6 The American Association for Public Opinion Research Response Rate 3 method was used to calculate the NSSRN response rate. 6 This study of deidentified publicly available data was determined to be exempt from approval and informed consent by the institutional review board of Emory University. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology ( STROBE ) reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies. Data were collected from April 30 to October 12, 2018.

We generated demographic characteristics from questions about years worked in the profession, primary and secondary nursing positions, and work environment. We included the work environment variables of primary employment setting and full-time or part-time status. We grouped responses to a question on dominant nursing tasks as direct patient care, other, and no dominant task. We included 3 categories of educational attainment (diploma/ADN, BSN, or MSN/PhD/DNP degrees) and whether the respondent was internationally educated. Other variables included change in employment setting in the last year, hours worked per week, and reasons for employment change.

We categorized employment setting as (1) hospital (not mental health), (2) other inpatient setting, (3) clinic or ambulatory care, and (4) other types of setting. Workforce stability was defined as the percentage of nurses with less than 5 years of experience in the nursing profession.

We used 2 questions to assess burnout and other reasons for leaving or planning to leave a nursing position. Nurses who had left the position they held on December 31, 2017, were asked to identify the reasons contributing to their decision to leave their prior position. Nurses who were still employed in the position they held on December 31, 2017, and answered yes to the question “Have you ever considered leaving the primary nursing position you held on December 31, 2017?” were asked “Which of the following reasons would contribute to your decision to leave your primary nursing position?”

Data were analyzed from June 5 to October 1, 2020. We used descriptive statistics to characterize nurse survey responses. For continuous variables, we reported means and SDs and for categorical variables, frequencies (number [percentage]). Further, we examined the overlap of the proportions who reported leaving or considered leaving their job owing to burnout and other factors. We then fit 2 separate logistic regression models to estimate the odds that aspects of the work environment, hours, and tasks were associated with the following outcomes related to burnout: (1) left job owing to burnout and (2) considered leaving their job owing to burnout. We controlled for nurse demographic characteristics of age, sex, race, household income, and geographic region and reported odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs. Two separate sensitivity analyses were performed: (1) we used a broader theme of burnout defined as a response of burnout, inadequate staffing, or stressful work environment for the regression models; and (2) we stratified the regression models by respondents younger than 45 years and 45 years or older to examine difference by age.

We used SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc), with statistical significance set at 2-sided α = .05. We used sample weights to account for the differential selection probabilities and nonresponse bias.

Of the 50 273 nurse respondents (representing 3 957 661 nurses nationally), respondents in 2018 were mostly female (90.4%) and White (80.7%). The mean (weighted SD) age of nurse respondents was 48.7 (0.04) years, and 95.3% were US graduates. The percentage of nurses with a BSN degree was 45.8%; with an MSN, PhD, or DNP degree, 16.3%; and 49.5% of nurses reported that they worked in a hospital. The mean (weighted SD) age of nurses who left their job due to burnout was 42.0 (0.6) years; for those considering leaving their job due to burnout, 43.7 (0.3) years ( Table 1 ).

Of the total weighted sample of nurses (N = 3 957 661), 9.5% reported leaving their most recent position (n = 418 769), and of those, 31.5% reported burnout as a reason contributing to their decision to leave their job (3.3% of the total sample) (eTable in the Supplement ). For nurses who had considered leaving their position (n = 676 122), 43.4% identified burnout as a reason that would contribute to their decision to leave their current job. Additional factors in these decisions were a stressful work environment (34.4% as the reason for leaving and 41.6% as the reason for considering leaving), inadequate staffing (30.0% as the reason for leaving and 42.6% as the reason for considering leaving), lack of good management or leadership (33.9% as the reason for leaving and 39.6% as the reason for considering leaving), and better pay and/or benefits (26.5% as the reason for leaving and 50.4% as the reason for considering leaving). By geographic regions of the US, lower proportions of nurses reported burnout in the West (16.6%), and higher proportions reported burnout in the Southeast (30.0%) ( Figure 1 and Figure 2 ). Figure 3 shows the overlap between leaving or considering leaving their position owing to burnout and other reasons. For both outcomes, the highest overlap response with burnout was for stressful work environment (68.6% of those who left their job and 63.0% of those who considered leaving their job due to burnout).

The adjusted regression models estimating the odds of nurses indicating burnout as a reason for leaving their positions or considering leaving their position revealed statistically significant associations between workplace settings and hours worked per week, but not for tasks performed, and burnout ( Table 2 ). For nurses who had left their jobs, compared with nurses working in a clinic setting, nurses working in a hospital setting had more than twice higher odds of identifying burnout as a reason for leaving their position (OR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.41-3.13); nurses working in other inpatient settings had an OR of 2.26 (95% CI, 1.39-3.68). Compared with working less than 20 h/wk, nurses who worked more than 40 h/wk had an OR of 3.28 (95% CI, 1.61-6.67) for identifying burnout as a reason they left their position.

For nurses who reported ever considering leaving their job, working in a hospital setting was associated with 80% higher odds of burnout as the reason than for nurses working in a clinic setting (OR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.55-2.08), whereas among nurses who worked in other inpatient settings, burnout was associated with a 35% higher odds that nurses intended to leave their job (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.05-1.73). Compared with working less than 20 h/wk, the odds of identifying burnout as a reason for considering leaving their position increased with working 20 to 30 h/wk (OR, 2.56; 95% CI, 1.85-3.55), 31 to 40 h/wk, (OR, 2.98; 95% CI, 2.24-3.98), and more than 40 h/wk, (OR, 3.64; 95% CI, 2.73-4.85).

The sensitivity analysis results in which a broader classification of burnout was used showed a similar relationship between odds of burnout and working more than 40 h/wk (OR, 3.86; 95% CI, 2.27-6.59) for those who left their job (OR, 2.66; 95% CI, 2.13-3.31). Stratification by those younger than 45 years and 45 years or older did not significantly change the findings. Figure 3 shows the overlap in nurses who reported burnout and other reasons for leaving their current position or considering leaving their current positions. The greatest overlap occurred in responses of burnout and stressful work environment (68.6% of those who reported leaving and 59.5% of those who considered leaving) and inadequate staffing (63.0% of those who reported leaving and 60.9% of those who considered leaving).

Our findings from the 2018 NSSRN show that among those nurses who reported leaving their jobs in 2017, high proportions of US nurses reported leaving owing to burnout. Hospital setting was associated with greater odds of identifying burnout in decisions to leave or to consider leaving a nursing position, and there was no difference by dominant work function.

Health care professionals are generally considered to be in one of the highest-risk groups for experience of burnout, given the emotional strain and stressful work environment of providing care to sick or dying patients. 8 , 9 Previous studies demonstrate that 35% to 54% of clinicians in the US experience burnout symptoms. 10 - 13 The recent National Academy of Medicine report, “Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being,” recommended health care organizations routinely measure and monitor clinician burnout and hold leaders accountable for the health of their organization’s work environment in an effort to reduce burnout and promote well-being. 1

Moreover, it appears the numbers have increased over time. Data from the 2008 NSSRN showed that approximately 17% of nurses who left their position in 2007 cited burnout as the reason for leaving, 14 and our data show that 31.5% of nurses cited burnout as the reason for leaving their job in the last year (2017-2018). Despite this evidence, little has changed in health care delivery and the role of registered nurses. The COVID-19 pandemic has further complicated matters; for example, understaffing of nurses in New York and Illinois was associated with increased odds of burnout amidst high patient volumes and pandemic-related anxiety. 15

Our findings show that among nurses who reported leaving their job owning to burnout, a high proportion reported a stressful work environment. Substantial evidence documents that aspects of the work environment are associated with nurse burnout. Increased workloads, lack of support from leadership, and lack of collaboration among nurses and physicians have been cited as factors that contribute to nurse burnout. 4 , 16 Magnet hospitals and other hospitals with a reputation for high-quality nursing care have shown that transforming features of the work environment, including support for education, positive physician-nurse relationships, nurse autonomy, and nurse manager support, outside of increasing the number of nurses, can lead to improvements in job satisfaction and lower burnout among nurses. 17 - 19 The qualities of Magnet hospitals not only attract and retain nurses and result in better nurse outcomes, based on features of the work environment, but also improvements in the overall quality of patient care. 17 - 19

Self-reported regional variation in burnout deserves attention. The lower reported rates of nurse burnout in California and Massachusetts could be attributed to legislation in these states regulating nurse staffing ratios; California has the most extensive nurse staffing legislation in the US. 20 The high rates of reported burnout in the Southeast and the overlap of burnout and inadequate staffing in our findings could be driven by shortages of nurses in the states in this area, particularly South Carolina and Georgia. 15 Geographic distribution, nurse staffing, and its association with self-reported burnout warrant further exploration.

Our data show that the number of hours worked per week by nurses, but not the dominant function at work, was positively associated with identifying burnout as a reason for leaving their position or considering leaving their position. Research suggests nurses who work longer shifts and who experience sleep deprivation are likely to develop burnout. 21 - 23 Others have reported a strong correlation between sleep deprivation and errors in the delivery of patient care. 22 , 24 Emotional exhaustion has been identified as a major component of burnout; such exhaustion is likely exacerbated by excessive work hours and inadequate sleep. 25 , 26

The nurse workforce represents most current frontline workers providing care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Literature from past epidemics (eg, H1N1 influenza, severe acute respiratory syndrome, Ebola) suggest that nurses experience significant stress, anxiety, and physical effects related to their work. 27 These factors will most certainly be amplified during the current pandemic, placing the nurse workforce at risk of increased strain. Recent reports suggest that nurses are leaving the bedside owing to COVID-19 at a time when multiple states are reporting a severe nursing shortage. 28 - 31 Furthermore, given that the nurse workforce is predominantly female and married, the child rearing and domestic responsibilities of current lockdowns and quarantines can only increase their burden and risk of burnout. Our results demonstrate that the mean age at which nurses who have left or considered leaving their current jobs is younger than 45 years. In the present context, our results forewarn of major effects to the frontline nurse workforce. Further studies are needed to elucidate the effect of the current pandemic on the nurse workforce, particularly among younger nurses of color, who are underrepresented in these data. Policy makers and health systems should also focus on aspects of the work environment known to improve job satisfaction, including staffing ratios, continued nursing education, and support for interdisciplinary teamwork.

Our study has some limitations. First, our findings are from cross-sectional data and limit causal inference; however, these data represent the most recent and, to our knowledge, the only national survey with data on nurse burnout. Second, our burnout measure is crude, and more extensive measures of burnout are needed. Third, 4 states did not have enough respondents to release data (Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, and South Dakota). However, these data were weighted, and they represent the most comprehensive data available on the registered nurse workforce. Fourth, nonresponse analyses of these data reveal underestimation of certain races/ethnicities, specifically Hispanic nurses, and small sample sizes limited analyses of burnout by race/ethnicity. Fifth, the public use file of the NSSRN does not disaggregate the MSN, PhD, and DNP degrees in nursing practice categories. Given that these job tasks can vary, we addressed this limitation by examining dominant function at work. Last, the response rate was modest at 49.0% (weighted). Despite these limitations, this analysis is most likely the first to provide an updated overview of registered nurse burnout across the US.

Burnout continues to be reported by registered nurses across a variety of practice settings nationwide. How the COVID-19 pandemic will affect burnout rates owing to unprecedented demands on the workforce is yet to be determined. Legislation that supports adequate staffing ratios is a key part of a multitiered solution. Solutions must come through system-level efforts in which we reimagine and innovate workflow, human resources, and workplace wellness to reduce or eliminate burnout among frontline nurses and work toward healthier clinicians, better health, better care, and lower costs. 32

Accepted for Publication: December 16, 2020.

Published: February 4, 2021. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36469

Correction: This article was corrected on March 16, 2021, to clarify that the given sample sizes were weighted values based on a smaller number of survey responses; changes have been made to the sample sizes in the Key Points, Abstract, Results section, and Table 1. The Supplement was corrected on April 7, 2021, to clarify in the eTable that the sample sizes are weighted values. The article was corrected on April 25, 2023, to add a previously missing grant awarded to Dr Cimiotti to the Funding/Support section.

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2021 Shah MK et al. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: Megha K. Shah, MD, MSc, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, 4500 N Shallowford Rd, Dunwoody, GA 30338 ( [email protected] ).

Author Contributions: Drs Shah and Gandrakota had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Shah, Cimiotti, Ghose, Moore, Ali.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Shah, Gandrakota, Cimiotti, Moore.

Drafting of the manuscript: Shah, Gandrakota, Cimiotti, Moore.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Gandrakota, Cimiotti, Moore.

Obtained funding: Shah.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Shah, Gandrakota, Ghose.

Supervision: Ali.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Ali reported receiving grants from Merck & Co outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grant K23 MD015088-01 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (Dr Shah), grant R01HS026232 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Dr Cimiotti), and in part by the Georgia Center for Diabetes Translation Research, funded by grant P30DK111024 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Dr Ali).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Burnout in nursing: a theoretical review

Affiliations.

- 1 School of Health Sciences, and Applied Research Collaboration Wessex, Highfield Campus, University of Southampton, Southampton, SO17 1BJ, UK. [email protected].

- 2 Department of Learning, Informatics, Management and Ethics, Karolinska Institutet, Tomtebodavägen 18a, 17177, Solna, Sweden.

- 3 School of Health Sciences, and Applied Research Collaboration Wessex, Highfield Campus, University of Southampton, Southampton, SO17 1BJ, UK.

- PMID: 32503559

- PMCID: PMC7273381

- DOI: 10.1186/s12960-020-00469-9

Background: Workforce studies often identify burnout as a nursing 'outcome'. Yet, burnout itself-what constitutes it, what factors contribute to its development, and what the wider consequences are for individuals, organisations, or their patients-is rarely made explicit. We aimed to provide a comprehensive summary of research that examines theorised relationships between burnout and other variables, in order to determine what is known (and not known) about the causes and consequences of burnout in nursing, and how this relates to theories of burnout.

Methods: We searched MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. We included quantitative primary empirical studies (published in English) which examined associations between burnout and work-related factors in the nursing workforce.

Results: Ninety-one papers were identified. The majority (n = 87) were cross-sectional studies; 39 studies used all three subscales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) Scale to measure burnout. As hypothesised by Maslach, we identified high workload, value incongruence, low control over the job, low decision latitude, poor social climate/social support, and low rewards as predictors of burnout. Maslach suggested that turnover, sickness absence, and general health were effects of burnout; however, we identified relationships only with general health and sickness absence. Other factors that were classified as predictors of burnout in the nursing literature were low/inadequate nurse staffing levels, ≥ 12-h shifts, low schedule flexibility, time pressure, high job and psychological demands, low task variety, role conflict, low autonomy, negative nurse-physician relationship, poor supervisor/leader support, poor leadership, negative team relationship, and job insecurity. Among the outcomes of burnout, we found reduced job performance, poor quality of care, poor patient safety, adverse events, patient negative experience, medication errors, infections, patient falls, and intention to leave.

Conclusions: The patterns identified by these studies consistently show that adverse job characteristics-high workload, low staffing levels, long shifts, and low control-are associated with burnout in nursing. The potential consequences for staff and patients are severe. The literature on burnout in nursing partly supports Maslach's theory, but some areas are insufficiently tested, in particular, the association between burnout and turnover, and relationships were found for some MBI dimensions only.

Keywords: Burnout; Job demands; Maslach Burnout Inventory; Nursing; Practice environment.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- Burnout, Professional / epidemiology*

- Health Status

- Internal-External Control

- Job Satisfaction

- Nurse's Role / psychology

- Nurses / psychology*

- Nurses / statistics & numerical data*

- Patient Safety

- Personnel Turnover / statistics & numerical data

- Quality of Health Care

- Sick Leave / statistics & numerical data

- Time Factors

- Workload / psychology

- Workplace / psychology*

- Thesis Example: Burnout Syndrome in Nurses

Nursing is a sensitive profession but is the most affected by stress disorders that arise from the complicated work schedule and departmental conformity. For that matter, burnout syndrome is a common problem among nurses working who happen to deal with multiple patients with healthcare demands that increases anxiety in nurses as a way of avoiding errors in the medical administration, time pressure and medical workload (Iglesias, de Bengoa Vallejo & Fuentes, 2010). Burnout syndrome denotes a response to chronic work-related stress that comprises of depersonalization, emotional exhaustion and personal accomplishment (Canadas-De la Fuente et al., 2015). Also, trying to provide healthcare in the required proportion while observing the work shift, disrespect from the public, violence from patients, understaffing, patients unpredictable, aggressive behavior and lack of support from the department and the society.

On the other hand, the other aspect that can make a nurse to develop burnout syndrome is the level of hardiness in a nurse. Italia, FavaraScacco, Di Cataldo and Russos (2008) research, the more a nurse can persevere, the more they avoid development of burnout syndrome. For that matter, the best individuals to pursue a nursing profession are the aggressive ones who surpass all odds that arise in the nursing profession (Ogresta, Rusac & Zorec, 2008). Nurses should portray a strong personality with a capacity to remain healthy during a long-term or lasting stressful situation. Why are nurses dealing with cancer and HIV patients the most prevalent in acquiring burnout syndrome? According to Korczak, Huber and Kisters (2010) research, burnout syndrome develops in nurses who are affected by emergency call services for cancerous patients who in one way or another need a more sustained approach to save them from the pandemic pinning them down (Costa et al., 2012). Similarly, some HIV patients who arrive at the healthcare center with severe effects of assuming the HIV call for an emergency service that makes nurses to develop anxiety in dealing with them and reinstating their health.

Regarding Mealer, Burnham, Goode, Rothbaum, and Moss (2009), another cause of burnout syndrome is the early life of nursing profession since the level of burnout syndrome decreases with the age of the nurses. Apart from socio-demographic factors, married individuals are also found to be most prevalent to married individuals due to suffering from emotional exhaustion (Al-Turki et al., 2010). Among elderly patients, burnout syndrome results from working long hours trying to manage the extended needs that the old require.

Al-Turki, H. A., Al-Turki, R. A., Al-Dardas, H. A., Al-Gazal, M. R., Al-Maghrabi, G. H., Al-Enizi, N. H., & Ghareeb, B. A. (2010). Burnout syndrome among multinational nurses working in Saudi Arabia. Annals of African Medicine, 9(4).

Canadas-De la Fuente, G. A., Vargas, C., San Luis, C., Garcia, I., Canadas, G. R., & Emilia, I. (2015). Risk factors and prevalence of burnout syndrome in the nursing profession. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(1), 240-249.

Costa, E. F. D. O., Santos, S. A., Santos, A. T. R. D. A., Melo, E. V. D., & Andrade, T. M. D. (2012). Burnout Syndrome and associated factors among medical students: a cross-sectional study. Clinics, 67(6), 573-580.

Demirci, S., Yildirim, Y. K., Ozsaran, Z., Uslu, R., Yalman, D., & Aras, A. B. (2010). Evaluation of burnout syndrome in oncology employees. Medical Oncology, 27(3), 968-974.

Iglesias, M. E. L., de Bengoa Vallejo, R. B., & Fuentes, P. S. (2010). The relationship between experiential avoidance and burnout syndrome in critical care nurses: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. International journal of nursing studies, 47(1), 30-37.

Italia, S., FavaraScacco, C., Di Cataldo, A., & Russo, G. (2008). Evaluation and art therapy treatment of the burnout syndrome in oncology units. PsychoOncology, 17(7), 676-680.

Korczak, D., Huber, B., & Kister, C. (2010). Differential diagnostic of the burnout syndrome. GMS health technology assessment, 6.

Mealer, M., Burnham, E. L., Goode, C. J., Rothbaum, B., & Moss, M. (2009). The prevalence and impact of post traumatic stress disorder and burnout syndrome in nurses. Depression and anxiety, 26(12), 1118-1126.

Ogresta, J., Rusac, S., & Zorec, L. (2008). Relation between burnout syndrome and job satisfaction among mental health workers. Croatian medical journal, 49(3), 364-374.

Request Removal

If you are the original author of this essay and no longer wish to have it published on the thesishelpers.org website, please click below to request its removal:

- Essay Example: Caring in Nursing

- Differences Between Dying and Bereavement Across Lifespan - Essay Example

- Preventing Medical Errors - Paper Example

- The Research Process in Nursing - Paper Example

- Essay on Personal Qualities and Attributes That Are Important in Nursing

- Evidence-Based Literature Review Paper Example

Submit your request

Sorry, but it's not possible to copy the text due to security reasons.

Would you like to get this essay by email?

Sorry, you can’t copy this text :(

Enter your email to get this essay sample.

Don’t print this from here

Enter your email and we'll send you a properly formatted printable version of this essay right away.

How about making it original at only $7.00/page

Let us edit it for you at only $7.00 to make it 100% original!

- Open access

- Published: 01 April 2024

Relationship between depression and burnout among nurses in Intensive Care units at the late stage of COVID-19: a network analysis

- Yinjuan Zhang 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Chao Wu 1 na1 ,

- Jin Ma 3 na1 ,

- Fang Liu 2 ,

- Chao Shen 4 ,

- Jicheng Sun 3 ,

- Zhujing Ma 5 ,

- Wendong Hu 3 &

- Hongjuan Lang 1

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 224 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Mental health problems are critical and common in medical staff working in Intensive Care Units (ICU) even at the late stage of COVID-19, particularly for nurses. There is little research to explore the inner relationships between common syndromes, such as depression and burnout. Network analysis (NA) was a novel approach to quantified the correlations between mental variables from the perspective of mathematics. This study was to investigate the interactions between burnout and depression symptoms through NA among ICU nurses.

A cross-sectional study with a total of 616 Chinese nurses in ICU were carried out by convenience sampling from December 19, 2022 to January19, 2023 via online survey. Burnout symptoms were measured by Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS) (Chinese version), and depressive symptoms were assessed by the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). NA was applied to build interactions between burnout and depression symptoms. We identified central and bridge symptoms by R package qgraph in the network model. R package bootnet was used to examined the stability of network structure.

The prevalence of burnout and depressive symptoms were 48.2% and 64.1%, respectively. Within depression-burnout network, PHQ4(Fatigue)-MBI2(Used up) and PHQ4(Fatigue)-MBI5(Breakdown) showed stronger associations. MBI2(Used up) had the strongest expected influence central symptoms, followed by MBI4(Stressed) and MBI7 (Less enthusiastic). For bridge symptoms. PHQ4(Fatigue), MBI5(Breakdown) and MBI2(Used up) weighed highest. Both correlation stability coefficients of central and bridge symptoms in the network structure were 0.68, showing a high excellent level of stability.

The symptom of PHQ4(Fatigue) was the bridge to connect the emotion exhaustion and depression. Targeting this symptom will be effective to detect mental disorders and relieve mental syndromes of ICU nurses at the late stage of COVID-19 pandemic.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Since COVID-19 broke out in Wuhan of China in December 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020 categorized the disease as a worldwide epidemic as global rapidly spreading [ 1 , 2 ]. People hit by SARS-CoV-2 were more prone to develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or even multiple system organ failure. Studies reported approximately 5–10% of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 were admitted to Intensive Care Units (ICU) for critical care due to the high mortality [ 3 , 4 ].

With the use of vaccines and the implementation of active epidemic prevention measures in China, the nationwide lockdown policy was ended. China entered the late stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in April 2020, and the China National Health Commission (CNHC) announced to lift most of the restrictions implemented for “Zero-COVID” policy (restricting mass gatherings, maintaining social distancing, and staying at home) on December 7, 2022 [ 5 ]. The pandemic of China came to a peak stage again in a short time and the number of COVID-19 patients in the ICUs was increasing rapidly due to high-speed spreading. ICU, unlike other parts of the hospital, are areas where complex and state-of-the-art devices are used and special treatment and care is delivered. Nurses in ICU are the backbones of effective health systems during this pandemic [ 6 ]. ICU nurses were confronted with difficult conditions, such as substantial workload, prolonged work hours and considerable risk of infection, which led to serious mental distress [ 7 , 8 ] and resulted in an increasing risk of psychiatric health problems, such as depression and burnout [ 9 , 10 ].

Many studies reported that nurses working in ICU showed high risk of depression during the pandemic of COVID-19 [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. A cross-sectional survey demonstrated over 40% of ICU nurses suffered from moderate to severe symptoms of depression during COVID-19 [ 14 ]. One systematic and meta-analysis including 20,617 healthcare workers proved that the prevalence of burnout in ICU nurses achieved 45% [ 15 ]. Burnout and depression of nurses had adverse effects on health of patients, and even threatened the safety of patient (i.e., medical administration errors, injury even death) [ 16 , 17 , 18 ], which was a global healthcare concern [ 19 ]. Besides, the intention to leave work in ICU nurses was rising during COVID-19. The WHO predicted that there would be a deficit of around 7.6 million nurses globally by 2030 before COVID-19 [ 20 ]. This deficit seemed likely to be greater as recent research had indicated that about 20% nurses had a thoughtful consideration of quitting for adverse mental health outcomes. Between them, ICU nurses had the highest of nearly 27% [ 21 ], which would be detrimental to the sustainable development of the nursing profession. Therefore, efforts should be made to improve the burnout and depression for this important group of care providers.

WHO in 2022 announced the implement of 7th of the International Classification of Disease [ 22 ], in which burnout is defined as a syndrome caused by chronic occupational stress that has not been managed successfully, and has resulted in feeling of energy exhaustion, negativism related to one’s work and lack of achievement. Nurse engaging in ICU are particular prone to suffer burnout due to exposure to pain, trauma, dying and closed environments, not necessary within pandemic [ 23 ]. Depression is a leading cause of disability and contributes greatly to global burden of disease [ 24 ]. People suffered from depression are characterized by persisted sadness, diminished pleasure or interest, even feeling of excessive guilt, hopelessness. Severe depression patients will think of self-harm or suicide [ 22 ]. WHO in 2022 has listed depression as one of high-risk factors leading to disability and the major contributor to suicide [ 24 ]. Depression not only negatively impact well-being of ICU nurses, but also extract toll on the health industry, with a severe adverse effect on healthcare quality [ 25 , 26 ].

The relation between burnout and depression has received a great deal of attention in recent years [ 27 , 28 ]. Burnout was identified as one of strongest predictor of depressive symptoms [ 29 , 30 ]. Meanwhile, depression symptoms contributed to the development of burnout [ 31 ]. But more importantly, burnout often co-occurred with depression [ 32 ]. A system review and meta-analysis reported that over 50% employers with burnout had depression [ 33 ]. A survey of healthcare workers in Macao and China found that depression was associated with all subscales of burnout after controlling for the strong effects of demographic factors [ 34 ]. 16.5% of psychiatric with depressive symptoms had high rate of burnout [ 35 ]. These data suggest there exist strong associations between burnout and depression symptoms. But how the symptoms of the two variables are associated still remain unclear.

Altogether, the previous studies have explored the interactions between burnout and depression at the syndrome level using traditional correlational methods, which included path analysis and multiple regression analysis in general. But those methods were based on the assumption of linear relationship, and couldn’t describe the complex non-linear contact between burnout and depression symptoms [ 36 ]. In order to overcome the issue, network analysis (NA) was applied to quantify the correlations between burnout and depression symptoms from the perspective of mathematical and display it intuitively. It wasn’t just on the basis of assumptions but a data-driven approach about causality between multiple variables [ 37 ]. In the theory of NA, mental syndromes and disorders were induced by the direct interactions between their corresponding symptoms, which included nodes representing observed variables (e.g., 15 nodes of burnout and 10 nodes of depression) and edges representing the associations between nodes. Therefore, exploring the accurate interactions was critical to elaborate psychopathological mechanisms and develop targeted intervention policies. Furthermore, NA could also provide centrality and predictability indices of each node, which helped researchers to identify and quantify to what extent burnout may transmit positive/negative influence to depression [ 38 ]. Since central symptoms in a network model closely connected with other symptoms, and they might active other symptoms. Thus, central symptoms with higher ranking score might become the target of treatment interventions, as they had a significant impact on the network. NA provided a new way to understand human psychological phenomena, and had been applied to the research of social psychology, clinical psychology, psychiatry and other fields [ 39 , 40 ].

Several studies have explored the symptom level interactions between burnout and depression symptoms using NA among different groups of people. Network structure among educational professions demonstrated that suicidal thoughts was only associated with other symptoms of depression, but not with those of burnout [ 41 ]. Another study showed that the symptoms of “feel down-hearted” and “no hope for future” were target interventions to relieve mental disorders of pharmacists [ 42 ]. However, it was uncertain whether these findings could be generalized to ICU nurses. Therefore, the current study applied the NA to further examine the interrelationship between burnout and depression symptom of ICUs nurses in order to implement effective and targeted interventions to prevent or reduce the occurrence of burnout and depression. The aims of the current study were two-fold: (1) to explore potential pathways linking between burnout and depression symptoms; (2) to use bridge expected influence to identify the most influential symptoms within the burnout-depression network.

Participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted among ICU nurses from December, 19 in 2022 to February, 19 in 2023 across six hospitals, which were Grade III-A General Hospitals of Shaanxi province of China. 616 nurses took part in the study. Due to COVID-19 pandemic, face-to-face assessment were not adapted. Following the previous researches during pandemic [ 43 , 44 ], the WeChat-based “Questionnaire Star” program was applied to conduct online survey. WeChat is a social media for communication, which has been used widely from 2017. The users now have achieved over 1.2 billion in China. Participants met the following inclusion criteria:(1) aged 18 and older; (2) be registered nurses who worked longer than 1 year in ICU; (3) engaged in frontline clinical nursing; (4) cared patients with COVID-19. Participants who were nursing students or had mental or physical disease were excluded from the study to ensure the integrity of the study’s outcomes. The study had met with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Shaanxi University of Chinese Medicine (No. SZFYIEC-YJ-2020-38). All participants were voluntary to join in this study and signed the informed consent form.

In order to ensure the effectiveness of online survey, we contacted with head nurses of ICU in advance and made them know the inclusion and exclusion criteria of our study clearly before the investigation. Then they send the online survey link to nurses who satisfied the requirements of our study. At last, we checked the answers of all the participants and deleted questionnaires with missing items after the survey. Besides, the participants would get a random lucky money to thank for their participation. A total of 636 nurses completed the survey, and 20 participants missed some items of questionnaire and demographic information. The effective rate was 97%.

Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS) (Chinese version) was used to measure the severity of burnout symptoms [ 45 ]. The 15 items of MBI-GS were scored on a seven-point Likert scale from “0” (never) to “6” (every day) capturing three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, cynicism and reduced personal achievement, with higher total scores indicating higher level of burnout. MBI-GS has extensively been applied to assess the mental distress in healthcare workers [ 46 ]. A sum score of MBI-GS above 34 was considered as suffering from burnout. The reliability of MBI-GS was evidenced in this study with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.845. Depression was assessed by Chinese version of Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which included 9 items with each scored on a four-Likert scale from “0” (not at all) to “3” (nearly every day). Higher scores of PHQ-9 indicated more severe depression symptoms. PHQ-9 gained strong validity and was widely used in the Chinese population [ 47 ]. Clinically relevant symptoms of depression were indicated by total score of 5 or higher on the PHQ-9 [ 48 ]. The reliability of PHQ-9 was evidenced in this study with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.820.

Statistical analysis

Network estimation.

The network of burnout and depressive symptoms was constructed by R software [ 49 ]. The polychoric correlations (i.e., edges) between all the MBI-GS and PHQ-9 items, were calculated based on the Graphical Gaussian Model (GGM) with the graphic least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) and Extended Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC) mode [ 50 ], and the R package qgraph was used to visualize the network model [ 51 ]. The edge color of blue indicated that the connection was positive, and red was negative. Besides, the edge thickness and saturation indicated connection strength. The stronger the connection, the thicker the edge, and the more saturated it was. We also calculated the central index expected influence (EI) by R package qgraph to identify the significance of each node in the network [ 52 ]. Nodes showing higher EI were considered to be more important in the network model. The bridge expected influence (BEI) of each item was calculated to identify bridge node that linked the burnout and depression in the current study [ 53 ], which represented the importance of one symptom linking two clusters of psychiatric symptoms [ 37 ]. In addition to, the package mgm was used to check the predictability of each node, which indicated the variance in a node that was affected by other nodes connected to it.

Network stability

In order to estimate the accuracy of the network model, R package bootnet was used to check the stability of EI and BEI [ 51 ]. The accuracy of the edge weight value was tested by calculating its estimated confidence interval (95% CI). The stability of IE and BIE were assessed by computing the correlation stability coefficients (CS-C). In general, the CS-C above 0.5 was ideal and should not be below 0.25 [ 51 ]. In order to check the difference between edge weights and node expected influence, bootstrapped difference tests were also conducted.

Study sample

A total of 616 ICU nurses completed the study (Table 1 ). The majority of the participants were female (490, 79%). The mean age was 28.0 ± 8.37 years, and the average number of working hours was 3.2 ± 0.65 years. The prevalence of burnout and depressive symptoms were 48.2% and 64.1%, respectively. Mean scores of the burnout and depression items with their SDs, expected influence, and predictability were shown in Table 2 .

Network structure

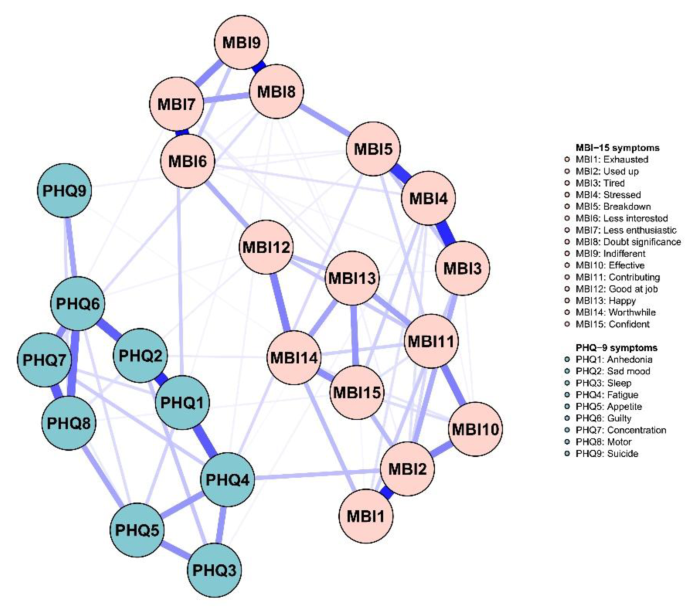

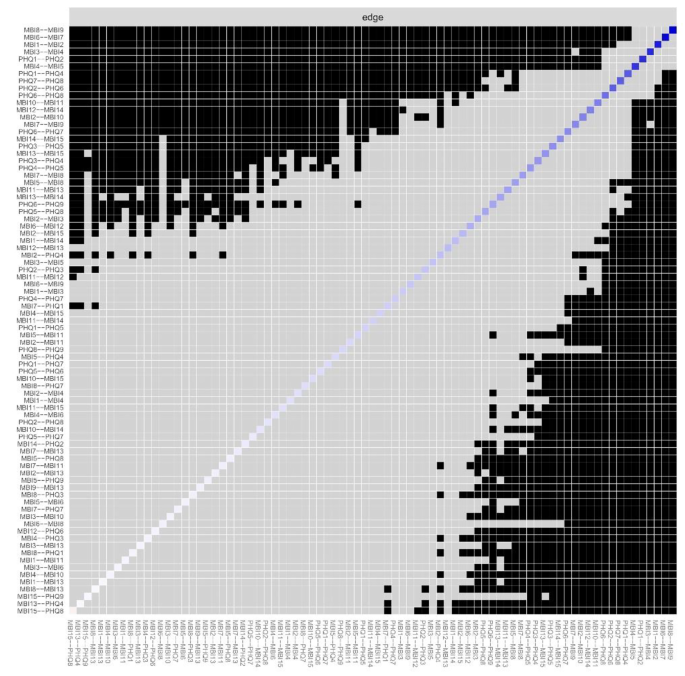

Figure 1 showed the network model of burnout and depression symptoms, and all the edges were positive. In the burnout symptoms, the strongest edge was MBI8 (Doubt significance)-MBI9 (Indifferent), followed by the edges MBI6 (Less interested)-MBI7 (Less enthusiastic) and MBI1 (Exhausted)-MBI2 (Used up). In the PHQ-9 symptoms, the strongest edge was PHQ2 (Sad mood)-PHQ1 (Anhedonia), followed by edges PHQ4 (Fatigue)-PHQ1 (Anhedonia) and PHQ8 (Motor)-PHQ7 (Concentration).

Network structure of burnout-depressive symptoms

In the burnout-depression network, the association between PHQ4 (Fatigue)- MBI2 (Used up) was the strongest, followed by PHQ1 (Anhedonia)-MBI7 (Less enthusiastic), and PHQ4 (Fatigue)-MBI5 (Breakdown) (Table 3 ). Table 3 showed the strength of each edge. Furthermore, the predictability of each node was showed, ranging from 0.28 to 0.79 with average value of 0.67 (Table 2 ).

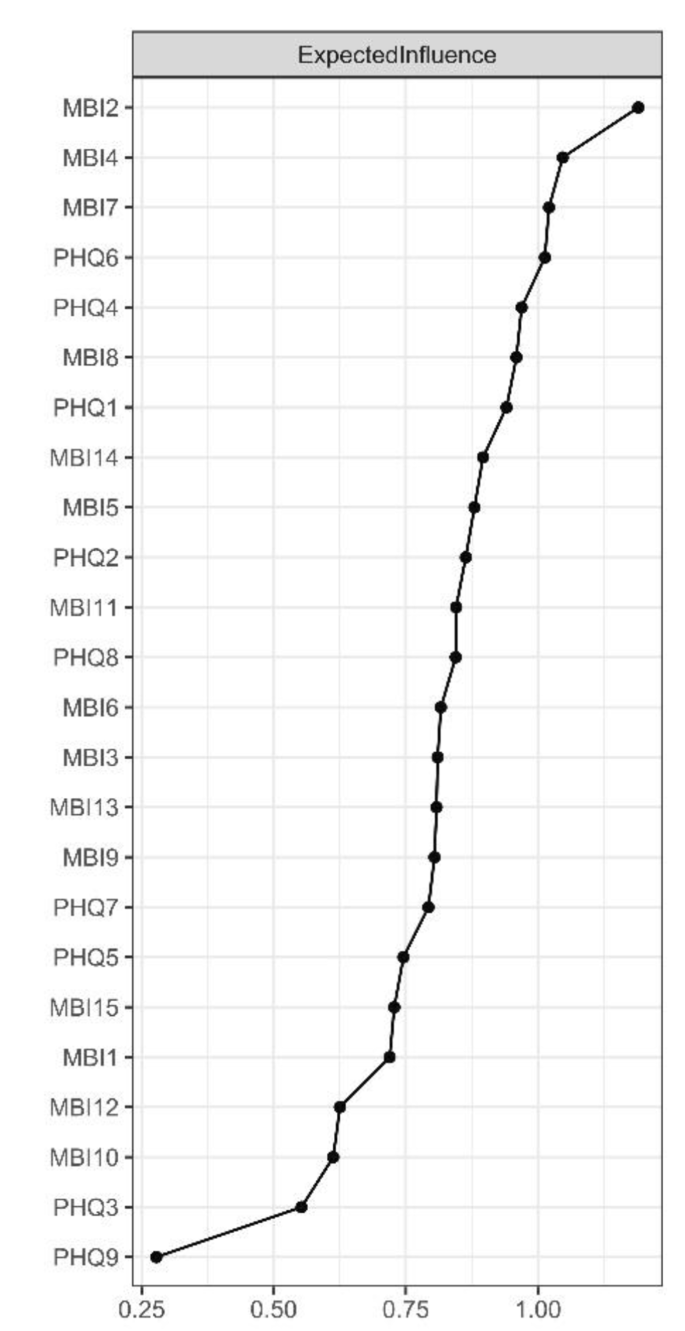

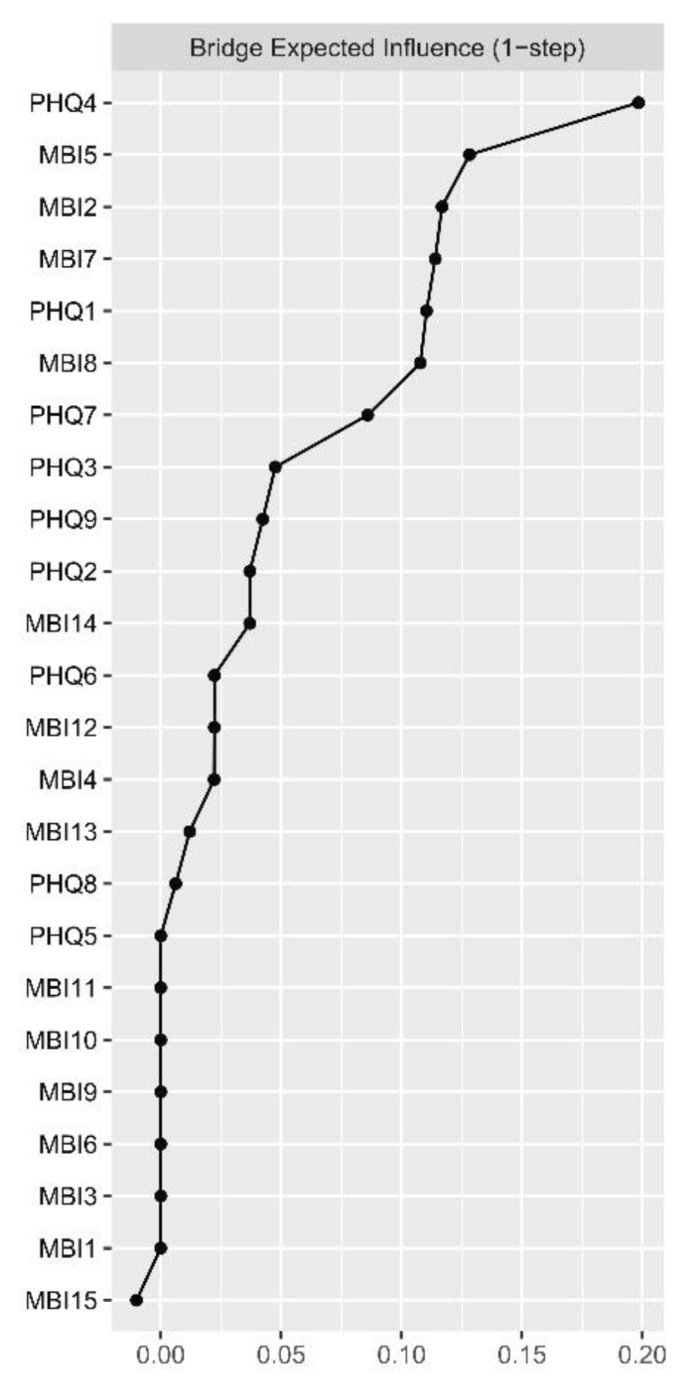

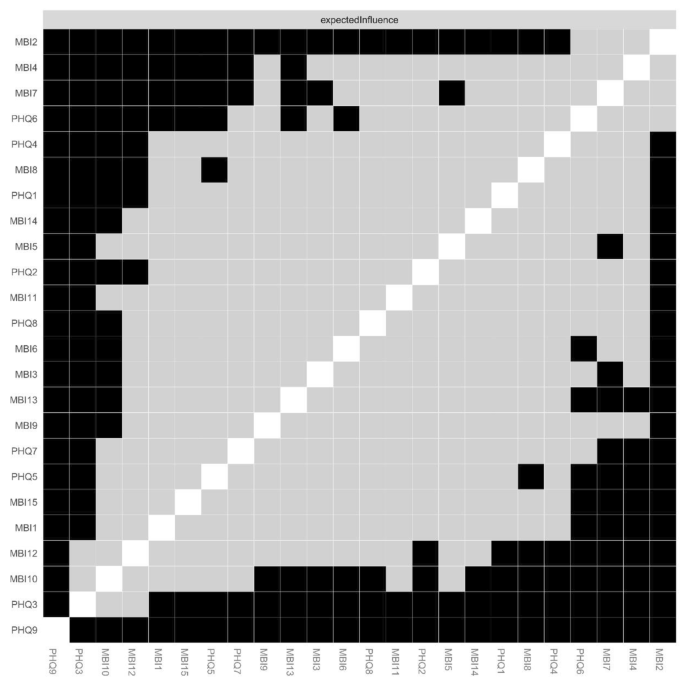

For centrality index expected influence (EI) (Fig. 2 ; Table 2 ), the node MBI2 (Used up) had the highest EI value, followed by MBI4 (Stressed), MBI7 (Less enthusiastic), PHQ6 (Guilty) and PHQ4 (Fatigue), implying that these symptoms were the central and influential for effecting the network model of burnout and depression among ICUs, whereas PHQ9 (Suicide) and PHQ3 (Sleep) had lowest EI value, showing marginal effect with the network. For bridge expected influence (BEI) (Fig. 3 ), PHQ4 (Fatigue) had the highest BEI value, followed by MBI5 (Breakdown), MBI2 (Used up), MBI7 (Less enthusiastic) and PHQ1 (Anhedonia), indicating these symptoms linking the burnout and depression symptoms at the late stage of COVID-19.

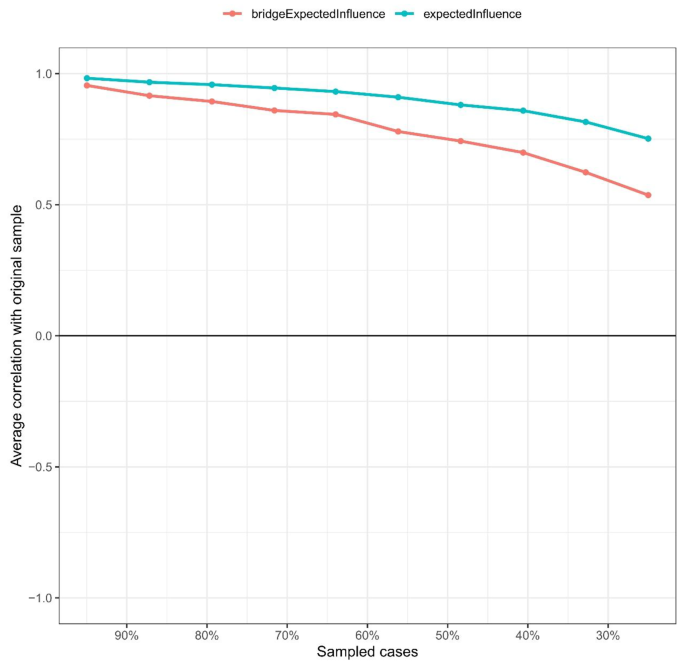

The network between burnout and depression showed a high excellent level of stability (Fig. 4 ). Both CS coefficients of EI and BEI were 0.68, which suggested that when 68% of the sample was dropped, the structure of the network did not change significantly. Supplementary Fig. S1 showed the bootstrapped 95% CI of edges and bootstrapped differences of edge weights, which were narrow and suggested high accuracy. Figure 5 showed the difference test of edge weights. The bootstrapped difference test found the most comparisons between EI were significantly different from the others (Fig. 6 ).

The node expected influence plot. The X-rays represented the expected influence of each node

The bridge expected influence plot. The X-rays represented the bridge expected influence of each node

The stability of the burnout- depression network

Estimation of edge weight difference by bootstrapped difference test

Bootstrapped difference test for edge weights. The black box indicates that edge weights of the two corresponding variables have a significant difference ( P < 0.05). The gray box indicates no significant difference ( P > 0.05)

Nonparametric bootstrapped difference test

Bootstrapped difference test for node expected influences. The black boxes indicate node expected influences that do differ significantly from one another ( P < 0.05), while the gray boxes indicate node expected influences that don?t differ significantly ( P > 0.05)

To our best knowledge, this was the first study to construct network model of burnout and depressive symptoms among ICU nurses at the late stage of COVID-19. The mean age of the participants was 28 years. The finding was similar to a cross-sectional survey showing the age of 26 years in ICU nurse of China [ 54 ], but lower than the average age of 39 years and 44 years reported in Italy and USA, respectively [ 55 , 56 ]. Furthermore, WHO reported nurses with an average aged of 41 to 50 are the main force in this team from an international study of 106 countries [ 57 ]. The discrepancy for the difference may be due to lacking promoting professional development and leadership opportunities of nurses in China at present, resulting in shifting to administrative units in hospitals for senior nurses, such as those involved in nutrition, laundry positions, etc. [ 58 ].

The score of burnout symptoms of ICU nurses indicated that the prevalence of burnout was 48.2%, which was in keeping with the prevalence (45%) of burnout reported by a meta-analysis in ICU nurses during COVID-19 [ 15 ]. Besides, participants reported a high prevalence (64.1%) of depressive symptoms. It was similar to the depression rate (65.5%) of ICU nurses reported in a study with a structural equation model during COVID-19 pandemic [ 59 ]. The findings implied that it is essential to pay attention to the mental problems of this special population. Furthermore, it is suggested to allocate human resources based on their psychological conditions for hospital management personnel.

In the burnout symptoms, the three highest relations were “Indifferent” - “Doubt significance”, “Less interested”- “Less enthusiastic” and “Exhausted”- “Used up”. The finding was consistent with our previous research used network analysis discussing the associations between burnout and neuroticism. For “Indifferent”-“Doubt significance” and “Exhausted”-“Used up” in our network models, Chen et al. reported the strong relations of “Exhausted”-“Used up” and “Contributing”–“Good at the job” in exploring the connections between burnout and mental health among medical staff [ 60 ].The former was consistent with our studies. The results implied the heavy psychological burden among ICU nurses during COVID-19. The latter difference could be explained for issues such as lower social status of ICU nurses and insufficient respect from patients and society relative to medical counterparts [ 61 , 62 ], and thus they were indifferent for contribution and doubted the significance of nursing occupation. For “Less interested”-“Less enthusiastic”, lack of interest toward work was associated with decreased enthusiasm during caring for patients [ 63 ].

In the depressive symptoms, the three highest relations were “Sad mood”-“Anhedonia”, “Fatigue”-“Anhedonia” and “Motor”-“Concentration”, which were in according with the findings of previous studies exploring the interrelationships between depression and other variables in medical staff during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 64 , 65 , 66 ]. However, one study found the relation between “Concentration” and “Suicide” weighed the highest [ 67 ]. The inconsistent result could be explained for different stages and professions. For the late stage of the epidemic, strict public health measures were canceled and healthcare workers saw the hope to conquer COVID-19, which gave rise to the stronger relationships between “Anhedonia” and “Sad mood” comparing to “Concentration” and “Suicide” in the network. For “Sad mood”-“Anhedonia” and “Fatigue”-“Anhedonia”, although our study conducted at the late stage of COVID-19, the mental and physical burden achieved highest because of sudden increased patients in ICU, which led to high levels of fatigue and then gave rise to feeling of anhedonia [ 68 ]. Besides, many ICU nurses also suffered from cough and fever owing to effecting by COVID-19 and had to keep working in their station because large number of patients were needed to care, which made nurses ICU having a sad mood, and caused anhedonia. As to “Motor”- “Concentration”, overload work and lack of communication with ICU patients led to showing psychomotor symptoms and lacking concentrations when caring patients in ICU nurses.

Within the depression-burnout symptoms, “Fatigue”-“Used up”, “Anhedonia”-“Less enthusiastic” and “Fatigue”-“Breakdown” weighted the strongest associations. For “Fatigue”-“Used up” and “Fatigue”-“Breakdown”, it was obvious fatigue was significantly related with emotional exhaustion (i.e., “Used up” and “Breakdown”). The relevant review in nurses reported the correlation of emotional exhaustion dimension in burnout was highest compared to others [ 27 ]. Furthermore, one literature suggested emotional exhaustion prevention should be paid more attention to relieve the fatigue of individuals, which could be achieved by better worktime and shift planning [ 69 ]. For “Anhedonia”-“Less enthusiastic”, excessive workload, such as irregular working hours, voluntary overtime, and closed contact with patients in ICU made nurses lose interest and enthusiastic in work tasks, thus to increase their inactive in working [ 8 ].

Expected influence (EI) of nodes performed well in recognizing specific symptoms that contributed strongly to the whole psychopathology symptom network. In this study, “Used up”, “Stressed” and “Less enthusiastic”, displayed the high EI in burnout-depression network. It meant these symptoms were critical and influential to understand the structure in burnout and depression model. A study reported a high risk of emotion exhaustion (38%) among ICU nurses in Belgium during pandemic [ 32 ], and this rate of emotional exhaustion in ICU nurses was more serious than other departments [ 70 ]. Furthermore, studies exploring the relations between burnout and depression showed that the correlation between emotional exhaustion and depression was higher compared to other relations [ 27 ]. The primary factors came from a higher ratio of patient-to-nurse in ICU than standard contract, prolonged working hours, and risks of transferring the infection to family members [ 71 ], which increased the risk of emotional exhaustion in ICU nurses. Regarding the above identified symptoms, some approaches were suggested. For example, establishing a reward system within ICU to ensure all nurses are rewarded and paid for their work equally [ 72 ]. Other strategies, such as enriching oneself, work-life balance schedule, and relaxed activity will be beneficial in reducing emotional exhaustion among ICU nurses [ 73 , 74 ]. Furthermore, among those symptoms, the symptoms of “Used up” and “Stressed” were emotion exhaustion dimension of burnout. We have found “fatigue” was significantly related with emotional exhaustion in the burnout-depression symptoms. Thus, taking intervention targeting the symptom of “fatigue” will be effective to reduce the severity of burnout and depression symptoms of ICU nurses.

Predictability in the network model is used to indicate to what extent the variation of a node can be predicted by the variation of its connected nodes. The average predictability identified in each node reached 0.67, which suggested on average of 67% of variance of each node could be explained by their neighbor nodes. Thus, symptoms of “Used up”, “Stressed” and “Less enthusiastic” discovered in this study spotlighted the psychiatric health of ICU nurses.

For bridge symptom in the current network, the highest bridge expected influence was “Fatigue”, followed by “Breakdown” and “Used up”, indicating that these symptoms were critical to maintain the entire network model and target for intervention [ 37 ]. Previous literature had reported that symptom of “Fatigue” was a bridge symptom in relevant network analysis [ 24 ]. Suffering from fatigue was common among medical staff during the COVID-19 pandemics [ 75 ], and might resulted from high workload pressure and fear of contagion [ 75 , 76 ]. “Breakdown” and “Used up” were identified as other key bridge symptoms. Maybe because these two symptoms were the consequence of “fatigue”. The evidence came from that edges of “Fatigue”-“Used up” and “Fatigue”-“Breakdown” showed highest correlations in the burnout-depression symptoms. It was well known that stress disorders had always been more prevalent among ICU nurses [ 77 , 78 ]. Nurses working in ICU needed to copy with complicated and critical situations quickly and accurately [ 79 , 80 ], and they also encountered much moments with separating and death than other department nurses in hospitals, which could further worsen their mental and physical fatigue. Especially, as the Chinese government lifted the restrictions implemented for “Zero-COVID” policy at the late stage of COVID-19, the number of severe COVID-19 patients were sent to ICUs for treatment, which placed extremely huge burden and overwhelmed nurses in ICU. Therefore, the current mental disorders in ICU nurses were worse than ever before.

Previous studies have shown that nurses working in specialized units such as ICU suffered from high levels of psychological and psychical tiredness [ 81 ]. Hence, interventions targeting “fatigue” of ICU nurses might reduce the severity of related symptoms. Related psychological interventions can improve the fatigue effectively, such as cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) [ 82 ], which is viewed as the first line of intervention thanks to its availabilities and effectiveness [ 83 ]. Besides, the nurse leaders can alleviate “fatigue” by shortening the shift length and overtime work of nursing staff during COVID-19 [ 84 ], and thus to lower the high level of burnout and depression among ICU nurses. It will be economic to design and implement related courses of fatigue and mental health during the initial and continuing education for nurses for ministry of education in China, which can help nurses identify and take timely intervene for fatigue symptom.

In general, exploring the highest centrality and bridge symptoms in the burnout and depression network was beneficial to take targeting interventions, and have far-reaching implications for reducing, identifying and prevention burnout and depression in ICUs nurses. Although the COVID-19 maybe has weakened in many countries, the infectious disease will never disappear in the world. Therefore, the current study provided advices or new thought to prevent and relieve the mental problems for nurse in ICU.

So far as we knew, this was the first study to visualize the relations between burnout and depression symptoms via network analysis among ICUs nurses in China at the late stage of COVID-19. However, some limitations should be noted. First, the causal relationships couldn’t be assessed as a result of a cross-sectional study. Second, the central symptoms and bridge symptoms identified in this study may not be generalized to other healthcare workers. Third, for the risk of contagion during the pandemic and closed management in ICUs, the data were collected by self-report measures by electronic questionnaires, which may cause bias.

Despite the constraints above, the present study used network analysis to explore the complex relationship between burnout and depression in ICU nurses. The prevalence of burnout and depressive symptoms were high. The symptom of PHQ4(Fatigue) of depression was the bridge to connect the emotion exhaustion of burnout. The finding helps us to detect mental problems more effective and provides potential target for intervention for mental disorders in ICU nurses. Further studies are expected to monitor the fatigue quantitatively and explore personalized interventions based on the level of fatigue and in ICU nurses.

Data availability

The data that supported this research was available and can be obtained by from the corresponding authors. For the protection of privacy and ethics restriction, the data cannot be public available.

Abbreviations

- Network analysis

Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey

9-item Patient Health Questionnaire

World Health Organization

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Intensive Care Units

Burnout syndrome

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

Extended Bayesian information criterion

Expected influence

Bridge expected influence

Correlation stability coefficients

Cognitive behavior therapy

Hui DS, Azhar EI, Madani TA, Ntoumi F, Kock R, Dar O, et al. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health-the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;91:264–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009 . Epub 2020 Jan 14.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

World Health Organization. WHO announces COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic [Internet]. Euro.who.int. 2020 [cited 2022 May 12]. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic .

Baud D, Qi X, Nielsen-Saines K, Musso D, Pomar L, Favre G. Real estimates of mortality following COVID-19 infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):773. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30195-X .

Murthy S, Gomersall CD, Fowler RA. Care for critically ill patients with COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1499–500. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3633 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China (NHCPRC) Notice on further optimizing and implementing the prevention and control measures for the COVID-19. (2022). Available at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/gzzcwj/202212/8278e7a7aee34e5bb378f0e0fc94e0f0.shtml .

WHO. State of the world’s nursing report 2020: executive summaries. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003279 .

Shen X, Zou X, Zhong X, Yan J, Li L. Psychological stress of ICU nurses in the time of COVID-19. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-02926-2 .

Article Google Scholar

Moradi Y, Baghaei R, Hosseingholipour K, Mollazadeh F. Challenges experienced by ICU nurses throughout the provision of care for COVID-19 patients: a qualitative study. J Nurs Adm Manag. 2021;29(5):1159–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13254 .

Pan X, Xiao Y, Ren D, Xu Z, Zhang Q, Yang L, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems and associated risk factors among military healthcare workers in specialized COVID-19 hospitals in Wuhan, China: a cross-sectional survey. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2022;14(1):e12427. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12427 . Epub 2020 Oct 21.

Dos Santos DS, Vieira da ST, Gomes Alexandre AR, Antunes F, Zeviani, Brêda. Cícera Dos SdA, Leão De NM. Depression and suicide risk among nursing professionals: an integrative review. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2015;49(6):1023–31. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0080-623420150000600020 .

El-Hage W, Hingray C, Lemogne C. Depression and suicide risk among nursing professionals: an integrative review: what are the mental health risks? Encephale. 2020;46(3S):S73–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2020.04.008 .

Chen J, Li J, Cao B, Wang F, Luo L, Xu J. Mediating effects of self-efficacy, coping, burnout and social support between job stress and mental health among Chinese newly qualified nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(1):163–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14208 .

Maqbali M, Sinani M, Lenjawi B. Prevalence of stress, depression, anxiety and sleep disturbance among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2021;14(110343):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110343 .

Heesakkers H, Zegers M, van Mol MMC, van den Boogaard M. The impact of the first COVID-19 surge on the mental well-being of ICU nurses: a nationwide survey study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;65:103034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103034 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Laurent Papazian1, Hraiech S, Loundou A, Herridge MS. Laurent Boyer. High-level burnout in physicians and nurses working in adult ICUs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2023;49:387–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-023-07025-8 .

Guillén-Astete C, Penedo-Alonso R, Gallego-Rodríguez P. Levels of anxiety and depression among emergency physicians in Madrid during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Emergencias. 2020;32(5):369–71.

PubMed Google Scholar

O’Callaghan EL, Lam L, Cant R, Moss C. Compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue in Australian emergency nurses: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2020;48:100785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2019.06.008 .

Stehman CR, Testo Z, Gershaw RS, Kellogg AR. Burnout, drop out, suicide: physician loss in emergency medicine, part I. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20:485–94. 13548506.2014.936889.

World Health Organization. World alliance for patient safety: the forward program 2005. http://www.who.int/patientsafety/en/brochure_final.pdf .

Ulupınar F, Erden Y. Intention to leave among nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Nursing.2022; 1–11. Availabe from: https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16588 .

Chutiyami M, Cheong AMY, Salihu D, Bello UM, Ndwiga D, Maharaj R et al. COVID-19 pandemic and overall mental health of healthcare professionals globally: a meta-review of systematic reviews. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2022; 12:804525. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.804525 .

ICD-11. International classification of diseases–eleventh revision. World Health Organ.2022. https://icd.who.int/browse11/lm/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/129180281 .

Abbas A, Ali A, Shouman W, Bahgat SM. Prevalence, associated factors, and consequences of burnout among ICU healthcare workers: an Egyptian experience. Egypt J Chest Dis Tuberc. 2019;68(4):514. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337146861 .

WHO.Depression. World Health Organization. 2022. https://www.who.int/health-topics/depression#tab = tab_1 .

Hadi SA, Bakker AB, Häusser JA. The role of leisure crafting for emotional exhaustion in telework during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2021;34:530–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2021.1903447 .

Sarfraz M, Hafeez H, Abdullah MI, lvascu L, Ozturk I. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers’ psychological and mental health: the moderating role of felt obligation. Work. 2022;71:539–50. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-211073 .

Chen CH, Scott TM. Burnout and depression in nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;124:104099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104099 .

Pereira-Lima K, Loureiro SR. Burnout, anxiety, depression, and social skills in medical residents. Psychol Health Med. 2015;20(3):353–62.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lluch C, Galiana L, Domenech P, Sanso N. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction in healthcare personnel: a systematic review of the literature published during the first year of the pandemic. Healthcare. 2022;10(2):364. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10020364 .

McCade D, Frewen A, Fassnacht DB. Burnout and depression in Australian psychologists: the moderating role of self-compassion. Aust Psychol. 2021;56(2):111–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2021.1890979 .

Serrão C, Rodrigues AR, Teixeira A, Castro L, Duarte I. The impact of teleworking in psychologists during COVID-19: burnout, depression, anxiety, and stress. Front Public Health. 2022;3(10):984691. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.984691 .

Bruyneel A, Smith P, Tack J, Pirson M. Prevalence of burnout risk and factors associated with burnout risk among ICU nurses during the COVID-19 outbreak in French speaking Belgium. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;65(103059):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103059 .

Koutsimani P, Montgomery A, Georganta K. The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2019;10:284. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00284 .

Zheng Y, Tang PK, Lin G, Liu J, Hu H, Man SW, Oi LU. Burnout among healthcare providers: Its prevalence and association with anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic in Macao, China. PLoS One. 2023; 16:18(3): e0283239. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0283239 . eCollection 2023.

Alkhamees A, Assiri H, Alharbi H, Nasser A, Alkhamees M. Burnout and depression among psychiatry residents during COVID-19 pandemic. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-021-00584-1 .

Tang Y, Zhang L, Li Q. Application of neural network models and logistic regression in predicting chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Public Health Prev Med. 2021;32(2):1216. 10.3969/. j. issn. 10062483.2021.02003.

Google Scholar

Bringmann LF, Elmer T, Epskamp S, Krause RW, Schoch D, Wichers M, et al. What do centrality measures measure in psychological networks? J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128:892–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000446 .

Jones P, Ma R, McNally R. Bridge centrality: a network approach to understanding comorbidity. Multivar Behav Res. 2021;56:353–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2019.1614898 .

Vanzhula IA, Kinkel-Ram SS, Levinson CA. Perfectionism and difficulty controlling thoughts bridge eating disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms: a network analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;283:302–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.08 .

Verkuilen J, Bianchi R, Schonfeld IS, Laurent E. Burnout depression overlap: exploratory structural equation modeling bifactor analysis and network analysis. Assessment. 2021;28:1583–600. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191120911095 .

Verkuilen J, Bianchi R, Schonfeld I, Laurent E. Burnout–depression overlap: exploratory structural equation modeling bifactor analysis and network analysis. Assessment. 2021;28:1583–600. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191120911095 .

He M, Li K, Tan X, Zhang L, Su C, Luo K, et al. Association of burnout with depression in pharmacists: a network analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1145606. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1145606 .

Luo H, Lie Y, Prinzen FW. Surveillance of COVID-19 in the general population using an online questionnaire: report from 18,161 respondents in China. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;27(6):e18576. https://doi.org/10.2196/18576 .

Zhou J, Liu L, Xue P, Yang X, Tang X. Mental health response to the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177:574–5. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030304 . Epub 2020 May 7.