Nursing Case Study for Breast Cancer

Watch More! Unlock the full videos with a FREE trial

Included In This Lesson

Study tools.

Access More! View the full outline and transcript with a FREE trial

Natasha is a 32-year-old female African American patient arriving at the surgery oncology unit status post left breast mastectomy and lymph node excision. She arrives from the post-anesthesia unit (PACU) via hospital bed with her spouse, Angelica, at the bedside. They explain that a self-exam revealed a lump, and, after mammography and biopsy, this surgery was the next step in cancer treatment, and they have an oncologist they trust. Natasha says, “I wonder how I will look later since I want reconstruction.”

What assessments and initial check-in activities should the nurse perform for this post-operative patient?

- Airway patency, respiratory rate (RR), peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), heart rate (HR), blood pressure (BP), mental status, temperature, and the presence of pain, nausea, or vomiting are assessed upon arrival. Medication allergies, social questioning (i.e. living situation, religious affiliation), as well as education preference are also vital. An admission assessment MUST include an examination of the post-op dressing and any drains in place. This should be documented accordingly.

- The hand-off should be thorough and may be standardized. Some institutions have implemented a formal checklist to provide a structure for the intrahospital transfer of surgical patients. Such instruments help to standardize processes thereby ensuring that clinicians have critical information when patient care is transferred to a new team. The nurse should also prepare to provide education based on surgeon AND oncologist guidance

What orders does the nurse expect to see in the chart?

- Post-op medications, dressing change and/or drain management, strict I&O, no BP/stick on the operative side (rationale is to help prevent lymphedema – Blood pressure (BP) measurement with a cuff on the ipsilateral arm has been posed as a risk factor for the development of LE after-breast cancer therapy for years, regardless of the amount of lymph node excision.)

- Parameters for calling the surgeon are also important. The nurse should also check for an oncology service consult.

After screening and assessing the patient, the nurse finds she is AAOx4 (awake, alert and oriented to date, place, person and situation). The PACU staff gave her ice due to dry mouth which she self-administers and tolerates well. She has a 20G IV in her right hand. She states her pain is 2 on a scale of 1-10 with 10 being the highest. Her wife asks when the patient can eat and about visiting hours. Natasha also asks about a bedside commode for urination and why she does not have a “pain medicine button”. Another call light goes off and the nurse’s clinical communicator (unit issued cell phone) rings.

The nurse heard in report about a Jackson-Pratt drain but there are no dressing change instructions, so she does not further assess the post-op dressing situation in order deal with everything going on at the moment. She then sits down to document this patient.

Medications ordered in electronic health record but not yet administered by PACU: Tramadol 50 mg q 6 hrs. Prn for mild to moderate pain. Oxycodone 5 mg PO q 4 hrs. Prn for moderate to severe pain (5-7 on 1-10 scale) Fentanyl 25 mcg IV q3hrs. Prn For breakthrough pain (no relieve from PO meds or greater than 8 on 1-10 scale) Lactated Ringers 125 mL/hr IV infusion, continuous x 2 liters Naloxone 0.4-2 mg IV/IM/SC; may repeat q2-3min PRN respiratory rate less than 6 bpm; not to exceed 10 mg

BP 110/70 SpO2 98% on Room Air HR 68bpm and regular Ht 157 cm RR 14 bpm Wt 53 kg Temp 36.°5C EBL 130mL CBC -WNL BMP Potassium – 5.4 mEq/L

What education should be conducted regarding post-op medications?

- New post-op pain guidelines rely less on patient-controlled analgesia (aka “pain medicine button”) than in previous years. Most facilities will have an approved standing protocol (i.e., “Multimodal analgesia and Opioid Prescribing recommendation” guideline) or standing orders. The patient must be instructed on how to rate pain using facility-approved tools (aka “pain scales”). She should also report any medication-related side effects and reinforce there is a reversal medication in case of an opioid overdose.

What are some medical and/or non-medical concerns the nurse may have at this point? If there are any, should they be brought up to the surgeon?

- The nurse may request an anti-emetic such as ondansetron 4 mg IV q 6 hrs prn nausea vomiting (N&V) since it is not uncommon post-op for the patient to have N&V. The rate of LR is a little high for such a small patient and could cause electrolyte imbalances. The nurse may also inquire about the oncologist being on the case and ask if the surgeon has discussed reconstruction with the patient yet. She may also want to ask about dressing change orders.

Natasha sleeps through the night with no complaints of pain. Lab comes to draw the ordered labs and the CNA takes vital signs. See below.

CBC HGB 7.2 g/dl HCT 21.6%

BMP Sodium 130 mEq/L Potassium 6.0 mEq/L BUN 5 mg/dL

BP 84/46 SpO2 91% on Room Air HR 109 RR 22 bpm

What should the nurse do FIRST? Is the nurse concerned about the AM labs? AM vital signs? Why or why not?

- Check the dressing and drain for bleeding (assess the patient). The patient should also sit up and allow staff to check the bed for signs of bleeding. Reinforce the dressing as needed. Record output from the drain (or review documentation of all the night’s drain output). Labs and vital signs indicate she may be losing blood.

Check the dressing and drain for BLEEDING (assess the patient). The patient should also sit up and allow staff to check the bed for signs of bleeding. Reinforce the dressing as needed. Record output from the drain (or review documentation of all the night’s drain output). Labs and vital signs indicate she may be losing blood.

What orders does the nurse anticipate from the surgeon?

- The nurse should expect an order to transfuse blood for this patient. Also, dressing reinforcement or change instructions are needed in the case of saturation)

How should the nurse address Natasha’s declaration? What alerts the nurse to a possible complication?

- First, the complication is that “Kingdom Hall” is the site of worship for Jehovah’s Witnesses. They do not accept ANY blood product, not even in emergencies. It is vital the nurse determines the patient’s affiliation and religious exceptions for medical care before moving forward. Next, employ therapeutic communication to elicit more details about Natasha’s concerns. Say things like, “tell me why you think you’re not attractive?” She may discuss reconstruction options or ask the patient to write down specific questions about this option to ask the provider later. Ask about getting family in to provide support. Seek information to give the patient about support groups and other resources available (as appropriate, ie. prosthetics, special undergarments/accessories, etc)

The surgeon orders 1 unit packed red blood cells to be infused. The nurse then goes to the patient to ask about religious affiliation and to discuss the doctor’s order. After verifying that Natasha is not a practicing Jehovah’s Witness, the nurse proceeds to prepare the transfusion.

What is required to administer blood or blood products?

- First, the patient’s CONSENT is required to give blood products. The nurse must also prepare to stay with the patient for at least the first 15 minutes of the transfusion taking a baseline set of V/S prior to infusion. Then, V/S per protocol (frequent). Education is also required. The patient should report feeling flushed, back or flank pain, shortness of breath, chest pain, chills, itching, hives. Normal saline ONLY for infusion setup and flushing: size IV 20g or higher. Always defer infusion time limits to “per policy” because this can differ vastly

How should the nurse respond to this question?

- Planning for post-op cancer treatment should have begun prior to the surgery. Ask the patient if she has discussed plans with her oncologist. Refer to any specialist documentation to see if this is mentioned. Remind the patient of the specialist’s assessment and planning information. Reinforce that testing of the tissue may change the course of treatment as well. Provide education AS PER THE PATIENT’S STATED PREFERENCE and/or resources based on what the plan includes (ie. chemotherapy, radiation, further surgery. Continually assess and reassess patient understanding. Include family and/or support with the patient’s approval.

View the FULL Outline

When you start a FREE trial you gain access to the full outline as well as:

- SIMCLEX (NCLEX Simulator)

- 6,500+ Practice NCLEX Questions

- 2,000+ HD Videos

- 300+ Nursing Cheatsheets

“Would suggest to all nursing students . . . Guaranteed to ease the stress!”

References:

View the full transcript, nursing case studies.

This nursing case study course is designed to help nursing students build critical thinking. Each case study was written by experienced nurses with first hand knowledge of the “real-world” disease process. To help you increase your nursing clinical judgement (critical thinking), each unfolding nursing case study includes answers laid out by Blooms Taxonomy to help you see that you are progressing to clinical analysis.We encourage you to read the case study and really through the “critical thinking checks” as this is where the real learning occurs. If you get tripped up by a specific question, no worries, just dig into an associated lesson on the topic and reinforce your understanding. In the end, that is what nursing case studies are all about – growing in your clinical judgement.

Nursing Case Studies Introduction

Cardiac nursing case studies.

- 6 Questions

- 7 Questions

- 5 Questions

- 4 Questions

GI/GU Nursing Case Studies

- 2 Questions

- 8 Questions

Obstetrics Nursing Case Studies

Respiratory nursing case studies.

- 10 Questions

Pediatrics Nursing Case Studies

- 3 Questions

- 12 Questions

Neuro Nursing Case Studies

Mental health nursing case studies.

- 9 Questions

Metabolic/Endocrine Nursing Case Studies

Other nursing case studies.

NurseStudy.Net

Nursing Education Site

Breast Cancer Nursing Diagnosis and Nursing Care Plan

Last updated on January 28th, 2024 at 08:03 am

Breast Cancer Nursing Care Plans Diagnosis and Interventions

Breast Cancer NCLEX Review and Nursing Care Plans

Breast cancer is a type of cancer that involves the uncontrolled growth and division of breast cancer cells. In the United States, breast cancer is the second most common types of cancer in women, after skin cancer.

Signs and Symptoms of Breast Cancer

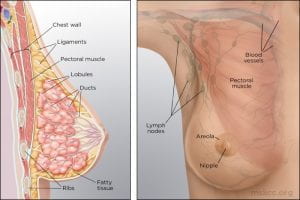

- Breast or underarm lump – usually the first symptom of breast cancer; does not go away; can be seen through a mammogram; may be painful or tender

- Swelling – may be seen or felt in the breast or in the lymph nodes located in the armpit or collarbone area

- Indentation or flattened area on a breast

- Changes in breast size, texture, color, contour, or temperature

- Unusual nipple discharge – can be bloody, clear, or any other color

- Other nipple changes such as inward pulling, dimpling, itchiness, soreness, burning sensation

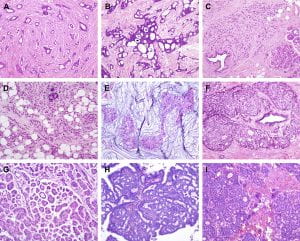

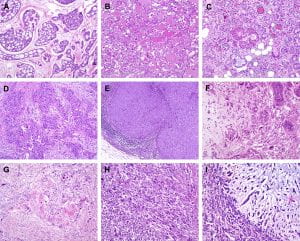

Types of Breast Cancer

- Ductal Carcinoma in Situ (DCIS). The most common breast cancer type, ductal carcinoma occurs in 1 out of 5 new cases of breast cancer. DCIS is a local breast tumor that has not spread in nearby lymph nodes and other tissues. Some cases of DCIS are asymptomatic, while others show bloody nipple discharge or a breast lump.

- Lobular Carcinoma. This type of breast cancer originates in the lobules, the glands where milk is produced. The most common symptoms of lobular carcinoma include swelling, thickening, and/or feeling of fullness in one region of the breast and inverted or flat nipples.

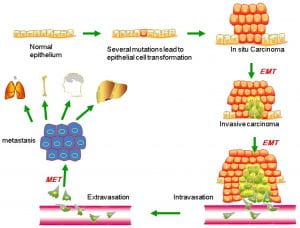

- Infiltrating or Invasive Breast Cancer. When the breast cancer has started spreading from its origin towards the surrounding tissues, it is classified as an invasive breast cancer. The symptoms of infiltrating breast cancer include a rash on the breast skin, dimpling, swelling, pain, and an immovable lump in the breast or armpit.

- Metastatic Breast Cancer. Also known as advanced or secondary breast cancer, metastatic breast cancer is the type when the disease has spread to other organs and parts of the body. The symptoms of metastatic breast cancer depend on where the disease has spread, but may involve bone pain, headache, jaundice , double vision, trouble breathing, belly swelling, weight loss, gastrointestinal problems, muscular weakness, confusion, and changes in brain function.

- Triple Negative Breast Cancer. This type of breast cancer is detected if the tumor produces only low levels of protein called HER-2 and does not contain receptors for estrogen and progesterone hormones. Triple negative breast cancers can be aggressive, thus the treatment protocol is usually different than other types of breast tumors.

- Male Breast Cancer. Breast cancer in males is rare. The symptoms such as lump in the breast or armpit and nipple discharge are the same as that of the females.

- Paget’s Disease of the Breast. This type of breast cancer occurs with ductal carcinoma. The symptoms of this disease include eczema-looking skin, scaly or crusty nipple skin, burning or itching breast skin, inverted or flat nipple, and yellowish or bloody nipple discharge.

Causes and Risk Factors of Breast Cancer

The exact cause of breast cancer is still unknown. However, the risk factors that may increase the chance of getting breast cancer are well-studied.

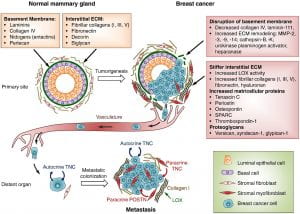

In general, breast cancer tumors develop from the rapid growth and division of abnormal breast cells (hyperplasia and dysplasia). Eventually, the cells accumulate and form a mass or a lump.

These abnormal breast cells may spread (metastasis) in the other parts of the breast, lymph nodes, or organs of the body.

The risk factors of breast cancer include:

- Gender – being a woman is the biggest risk factor of having breast cancer, although 1% of the cases occur in men.

- Age – 2 of 3 invasive breast cancer cases are seen in women aged 55 years or above

- Family History and Genetics– the risk is doubled if a woman has a first-degree female relative that has been diagnosed with breast cancer (mother, sister, or daughter)

- Past Medical History of Breast Cancer – if the patient has had breast cancer in the past, he/she is 3 to 4 times likely to develop breast cancer in the future; having had benign breast conditions in the past also increase the risk for breast cancer

- Race and Ethnicity – White women have a slightly higher risk for breast cancer than Hispanic, Black, and Asian women

- Exposure to Radiation – if the patient had radiotherapy to the face or chest to treat acne or another cancer type such as lymphoma , the risk for developing breast cancer is higher than average

- Obesity and being overweight

- History of Pregnancy – women who have had their first child after age 30 or have not had any full term pregnancy have a higher risk than women who have had full term pregnancy and/or gave birth before age 30.

- Breastfeeding – studies show that breastfeeding, especially for longer than 1 year, lowers the risk of breast cancer

- Menstrual History – women who had periods younger than age 12 have a higher risk of breast cancer; menopausing older than 55 years old also increases the risk

- Alcohol use and Smoking

- Hormone Replacement Therapy – HRT users have a higher risk of breast cancer

- Sedentary Lifestyle

Complications of Breast Cancer

- Pulmonary insufficiency

- Metastasis to other organs or parts of the body

- Cardiac disease

Diagnosis of Breast Cancer

- Breast Exam. This can be done daily through self-checking. During a breast exam in the clinic, the doctor will observe and feel/palpate the breasts and the lymph nodes in the armpit for any abnormalities such as lumps.

- Mammogram. X-ray of the breast or mammogram is the most common screening test for breast cancer. Women with no history of breast cancer are recommended to have a yearly mammogram once they turn 40 years old.

- Breast Ultrasound. This can determine if a breast lump is a fluid-filled cyst or a solid mass.

- Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). This is used to visualize the breast by creating pictures. MRI involves injection of a dye to see the interior of the breast.

- Breast Biopsy. The definitive way to diagnose breast cancer, biopsy involves taking a sample of breast cells to be studied under the microscope.

- Cancer Staging. After diagnosis, the oncologist will assess the extent or stage of breast cancer, from 0 to IV. Cancer staging depends on the blood test results (complete blood count and tumor markers (i.e., cancer antigen 15-3 or CA 15-3, cancer antigen 27.29 or CA 27.29, and carcinoembryonic antigen or CEA), CT/ PET scan, and other diagnostic results.

Treatment for Breast Cancer

- Breast Surgery. The removal of breast cancer cells through operation can vary depending on the size, grade, and extent of the tumor and disease.

- Lumpectomy – to remove small tumors and a margin of surrounding healthy breast tissues; also known as wide local excision or breast-conserving surgery

- Mastectomy – to remove the entire breast

- Sentinel node biopsy – to remove a limited number of lymph nodes and determine cancer spread in these areas

- Axillary lymph node dissection – to remove additional lymph nodes if the sentinel nodes show signs of cancer

- Medications. Several pharmacologic therapies have been used to treat breast cancer, such as:

- Chemotherapy – uses drugs to kill cancer cells. The most common chemotherapy protocols for breast cancer include combinations of anti-tumor antibiotics and alkylating agents, followed by taxanes.

- Hormone Therapy – used to treat breast cancers that are sensitive to hormones estrogen and/or progesterone

- Targeted Therapy – uses drugs that attack specific abnormalities in the cancer cell, such as human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2); an example is the use of monoclonal antibodies (MABs)

- Immunotherapy – utilizes the immune system to attack the breast cancer cells; examples include immune system modulators and checkpoint inhibitors

- Radiotherapy. Radiotherapy uses radiation or high-powered energy beams such as protons and X-rays to kill the cancer cells. This can last from 3 days to 6 weeks.

- External beam radiation – aims the energy beams at the affected body area

- Brachytherapy – places radioactive material inside the body in order to perform radiation therapy

Nursing Diagnosis for Breast Cancer

Breast cancer nursing care plan 1.

Nursing Diagnosis: Deficient Knowledge related to new diagnosis of breast cancer as evidenced by patient’s verbalization of “I want to know more about my new diagnosis and care”

Desired Outcome: At the end of the health teaching session, the patient will be able to demonstrate sufficient knowledge of breast cancer and its management.

Breast Cancer Nursing Care Plan 2

Nursing Diagnosis: Imbalanced Nutrition: Less than Body Requirements related to consequences of chemotherapy for breast cancer, as evidenced by abdominal cramping, stomach pain, diarrhea or constipation , bloating, weight loss, nausea and vomiting , and loss of appetite

Desired Outcome: The patient will be able to achieve a weight within his/her normal BMI range, demonstrating healthy eating patterns and choices.

Breast Cancer Nursing Care Plan 3

Nursing Diagnosis: Fatigue related to consequence of chemotherapy for breast cancer (e.g., immunosuppression and malnutrition ) and/or emotional distress due to the diagnosis, as evidenced by overwhelming lack of energy, verbalization of tiredness, generalized weakness, and shortness of breath upon exertion

Desired Outcome: The patient will establish adequate energy levels and will demonstrate active participation in necessary and desired activities.

Breast Cancer Nursing Care Plan 4

Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements

Nursing Diagnosis: Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements related to fatigue, emotional distress, and poorly controlled pain due to chemotherapy secondary to breast cancer, as evidenced by expressions of inadequate food intake, loss of interest in food, inability to ingest food, reduced subcutaneous fat, body weight 20 percent below optimum for height and frame, stomach cramps and constipation.

Desired Outcomes:

- The patient will be able to demonstrate a stable weight gain toward the goal with normal laboratory values.

- The patient will not show any indicators of malnutrition.

- The patient will be able to participate in specific interventions to gain appetite and increase dietary intake.

Breast Cancer Nursing Care Plan 5

Risk for Infection

Nursing Diagnosis: Risk for Infection related to insufficient secondary defenses, immunosuppression, and chronic disease process secondary to breast cancer, as evidenced by damaged epidermal tissue, skin irritation on injection site, shortness of breath, presence of mucus in the saliva, nasal drainage, fever of 100.5 °F, sore throat and chills.

- The patent will be able to stay afebrile and achieve timely healing as appropriate.

- The patient will be able to identify and participate in interventions to prevent or minimize the risk of infection.

Breast Cancer Nursing Care Plan 6

Anticipatory Grieving

Nursing Interventions: Anticipatory Grieving related to expected decline in physiological health and perceived risk of dying secondary to breast cancer, as evidenced by alterations in eating habits, changes in sleeping patterns, activity levels, and communication patterns, shortness of breath, acute panic, expressions of fear and crying.

- The patient will be able to recognize their own emotions and convey them effectively.

- The patient will be able to maintain the normal daily routine while planning for the future and looking ahead one day at a time.

- The patient will be able to express awareness of the dying process.

- The patient will demonstrate ways to identify anxiety to prevent going into a panic state.

More Breast Cancer Nursing Diagnosis

- Fear / Anxiety

- Risk for Altered Oral Mucous Membranes

- Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity

- Risk for Disturbed Body Image

Nursing References

Ackley, B. J., Ladwig, G. B., Makic, M. B., Martinez-Kratz, M. R., & Zanotti, M. (2020). Nursing diagnoses handbook: An evidence-based guide to planning care . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Gulanick, M., & Myers, J. L. (2022). Nursing care plans: Diagnoses, interventions, & outcomes . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Ignatavicius, D. D., Workman, M. L., Rebar, C. R., & Heimgartner, N. M. (2020). Medical-surgical nursing: Concepts for interprofessional collaborative care . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Silvestri, L. A. (2020). Saunders comprehensive review for the NCLEX-RN examination . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Disclaimer:

Please follow your facilities guidelines, policies, and procedures.

The medical information on this site is provided as an information resource only and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes.

This information is intended to be nursing education and should not be used as a substitute for professional diagnosis and treatment.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Breast Cancer: Survivorship Care Case Study, Care Plan, and Commentaries

Affiliation.

- 1 Saint Louis University.

- PMID: 34800110

- DOI: 10.1188/21.CJON.S2.34-42

This case study highlights the patient's status in care plan format and is followed by commentaries from expert nurse clinicians about their approach to manage the patient's long-term or chronic cancer care symptoms. Finally, an additional expert nurse clinician summarizes the care plan and commentaries, emphasizing takeaways about the patient, the commentaries, and additional recommendations to manage the patient. As can happen in clinical practice, the patient's care plan is intentionally incomplete and does not include all pertinent information. Responding to an incomplete care plan, the nurse clinicians offer comprehensive strategies to manage the patient's status and symptoms. For all commentaries, each clinician reviewed the care plan and did not review each other's commentary. The summary commentary speaks to the patient's status, care plan, and nurse commentaries.

Keywords: breast cancer; care plan; case study; survivorship care.

- Breast Neoplasms* / therapy

- Survivorship*

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

A case-case analysis of women with breast cancer: predictors of interval vs screen-detected cancer

Nickolas dreher.

1 University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA

2 The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA

Madeline Matthys

Edward hadeler.

3 University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL, USA

Yiwey Shieh

Irene acerbi, fiona m. mcauley, michelle melisko, martin eklund.

4 Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Jeffrey A. Tice

Laura j. esserman, laura j. van ‘t veer.

Authors’ contributions: All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Nickolas Dreher, Madeline Matthys, and Edward Hadeler. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Nickolas Dreher and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Associated Data

The Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) model is a widely-used risk model that predicts five- and ten-year risk of developing invasive breast cancer for healthy women aged 35–74 years. Women with high BCSC risk may also be at elevated risk to develop interval cancers, which present symptomatically in the year following a normal screening mammogram. We examined the association between high BCSC risk (defined as the top 2.5% by age) and breast cancers presenting as interval cancers.

We compared the mode of detection and tumor characteristics of patients in the top 2.5% BCSC risk by age with age-matched (1:2) patients in the lower 97.5% risk. We constructed logistic regression models to estimate the odds ratio (OR) of presenting with interval cancers, and poor-prognosis tumor features, between women from the top 2.5% and bottom 97.5% of BCSC risk.

Our analysis included 113 breast cancer patients in the top 2.5% of risk for their age and 226 breast cancer patients in the lower 97.5% of risk. High-risk patients were more likely to have presented with an interval cancer within one year of a normal screening, OR 6.62 (95% CI 3.28–13.4, p<0.001). These interval cancers were also more likely to be larger, node positive, and higher stage.

Conclusion:

Breast cancer patients in the top 2.5% of BCSC risk for their age were more likely to present with interval cancers. The BCSC model could be used to identify healthy women who may benefit from intensified screening.

Introduction

Interval cancers are invasive breast cancers that present symptomatically within 12 months of a normal screening mammogram. These cancers include both those that develop after a mammogram and those that were not detected (but did exist) at the previous screening mammograms. Interval cancers tend to be more aggressive and faster-growing than screen-detected cancers.[ 1 – 4 ] Identifying women who are at increased risk for interval breast cancers could inform screening strategies, as these women may benefit from supplemental or more frequent screening and risk reduction. However, no consensus regarding how to risk-stratify women for interval breast cancer risk exists. The Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) model is a validated and widely used risk prediction tool that predicts five- and ten-year risk of developing invasive breast cancer for women age 35–74.[ 5 ] It bases risk prediction on age, race/ethnicity, presence of first degree relative with breast cancer, prior biopsies/benign breast disease, and Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) breast density.[ 5 , 6 ] Past work by Kerlikowske et al. has suggested that the combination of BCSC risk and BI-RADS breast density is one method upon which risk-stratification for interval cancer could be based.[ 7 ]

However, both the BCSC model and breast density itself are correlated with age: as age increases, BCSC score increases and breast density decreases. Providers may be wary of basing recommendations for screening frequency and modality on risk models (such as BCSC) that may enrich for increased screening as age increases. Further, tumor characteristics and morbidity vary by age, with younger women being at increased risk of developing poor prognosis tumors and interval cancers.[ 7 – 9 ] In contrast to using an absolute risk cutoff to identify high risk women, an alternative method is to use age-specific cutoffs. Age-specific BCSC risk distributions are generated directly by the BCSC, and aggregate 5-year age groups have been described in the literature.[ 5 ] The WISDOM study, run by the Athena Breast Health Network, uses these distributions to establish a threshold of the top 2.5% of risk for each age group to initiate counseling on prevention interventions and annual screening. Prior thresholds were not sufficiently high to motivate interest in embarking on risk reduction strategies.[ 10 ] The top 2.5% by age threshold consistently identifies women with lifetime risk of 23–28%, and 20% of these women elect to pursue prevention interventions. This is why it was chosen for the high risk threshold to trigger for annual screening and prevention counseling in WISDOM.[ 10 ]

This study’s primary aim is to validate this top 2.5% by age threshold by determining if these women are more likely to present with interval cancers rather than screen-detected cancers. We also evaluated whether these interval cancers have more aggressive features to confirm the clinical relevance of detecting interval cancers.

Patients and Methods

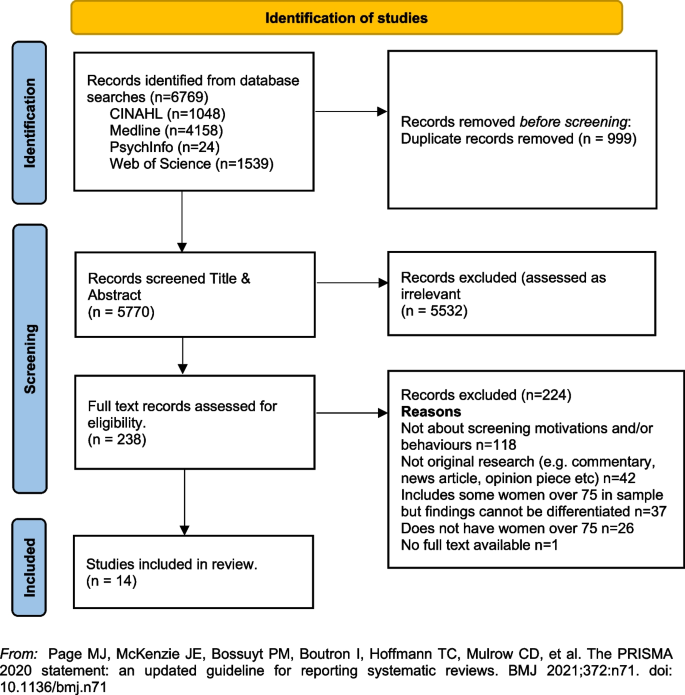

We conducted a case-case analysis of women treated for invasive breast cancer at the University of California San Francisco Breast Care Center (UCSF BCC). This study included only women with a confirmed diagnosis of invasive breast cancer previously undergoing standard mammography screening. Between 2013 and 2017, 896 patients completed the Athena intake questionnaire (described in Measures ) in the BCC and had available BI-RADS breast density and pathology data. We identified the 180 women in the top 2.5% of BCSC risk for their age. Women were excluded from the study if they deviated from standard screening intervals by having an increased screening frequency (more than 1 mammogram per year) or if they had an “interval” cancer detected more than one year after their prior clear mammogram. Ultimately, information on mode of detection (screen detected versus interval breast cancer) was available for 113 women in the top 2.5% of risk for their age. We then used a random number generator to select age-matched (±1 year) women from the lower 97.5% who also had method of detection available. ( Figure 1 ).

Selection of the study group from women seen at the UCSF Breast Care Center from 2013–2017. Top 2.5% threshold determined from distributions of BCSC 5-year risk estimates.

The UCSF BCC is part of the Athena Breast Health Network, a breast cancer clinical care and research collaborative that includes breast care clinics from five University of California hospitals and Sanford Health in South Dakota.[ 11 ] Athena collects patient characteristics and outcome data across the entire care spectrum from screening and prevention to treatment and survivorship. At the UCSF BCC, questionnaires are distributed to all patients presenting with a new breast problem.

The Athena intake questionnaire at the BCC collects race/ethnicity, family history, personal cancer history, history of prior biopsies, presence of comorbidities, and psychosocial and physical quality of life metrics.[ 12 ] These questionnaires contain all the variables included in the BCSC model ( http://tools.bcsc-scc.org/BC5yearRisk/ ) except for BI-RADS density. Using the electronic medical record, we exported BI-RADS density based on the last negative screening mammogram prior to diagnosis and used it for the BCSC risk assessment. While the BCSC model is intended for women without a history of breast cancer, this allowed for a retrospective estimate of each patient’s 5-year risk of developing cancer at the approximate time of their diagnosis with the assumption that breast density stayed relatively stable between the last negative mammogram and density.[ 13 ] The 97.5 th BCSC risk percentile for each age ( Supplementary Table A ) was estimated by applying the BCSC risk calculator to data collected from more than six million mammograms from eight breast imaging registries across the country.[ 14 ]

The BCSC risk score was calculated for eligible women (those between the ages of 40–74 without a diagnosis of breast cancer prior to the current diagnosis) who completed the online intake questionnaire and whose BI-RADS density was available ( Figure 1 ). These BCSC scores were based on the patient’s age at time of intake. Medical records for all patients in the top 2.5% of risk for their age and two age-matched (±1 year) cases from the bottom 97.5% of risk were reviewed to determine method of cancer detection.

The UCSF Cancer Center registry contains pathology and outcome data linked to state and national registries, and has been described previously.[ 15 , 16 ] We collected information on each patient’s histology, grade, stage, nodal involvement, hormone receptor status, and tumor size from the Registry. If data were not available for a patient, we imported these fields from the UCSF surgical registry. The UCSF BCC maintains an internal surgical registry that is updated weekly with pathology reports from recent surgeries. This dataset, updated in near real-time, was included to capture data that were not yet reported in other registries.

Our primary outcome focused on interval cancers, defined as invasive breast cancers that presented within one year of a normal mammogram, BI-RADS score 1 or 2. Tumor characteristics including hormone receptor status, grade, size, nodal involvement and stage were imported from the registries based on patient medical record number and approximate diagnosis date.

Statistical Analysis

We compared the proportion of interval cancers between the two age-matched groups using conditional logistic regressions in R. We also used logistic regressions to compare tumor characteristics between interval cancers and screen-detected cancers. All tests were two-sided with alpha of 0.05.

In addition to comparing patients in the top 2.5% of risk for their age to patients from the lower 97.5%, we examined two additional risk stratification criteria from the literature: patients with extremely dense breasts (BI-RADS d) or a very high BCSC score irrespective of age (>4.00% 5-year risk of developing breast cancer).[ 7 ] This was an adjunct analysis included to address potential questions from the reader. However, it is important to note that the sample used in this study is not matched based on these two criteria.

Patient Characteristics

Of the 339 patients included in the final analysis, 113 fell in the top 2.5% of risk for their age, and they were compared to 226 from the lower 97.5% of risk ( Figure 1 ). Table 1 summarizes demographic information from the patients included in the analysis. Women in the top 2.5% of risk for their age tended to have higher breast density and more frequently reported a first degree relative with breast cancer and a personal history of breast biopsy (p<0.001 for all comparisons).

Baseline characteristics and demographic data for women in the top 2.5% of risk for their age (n=113) and age-matched women from the lower 97.5% (n=226).

Interval cancer risk by BCSC risk group

Patients from the top 2.5% of risk for their age were more likely to present with an interval cancer within one year of a normal screening mammogram compared to patients in the lower 97.5% of risk, OR 6.62 (95% CI 3.28–13.4, p<0.001) ( Table 2 ). Similar results were seen when we expanded the analysis to include “late-interval” cancers, those discovered within two years of a normal screening mammogram.

Association between three risk stratification criteria and interval cancers. The three risk stratification criteria included the BCSC top 2.5%, BI-RADS d (extremely dense), or BCSC 5-year cancer risk >4.00% (very high).

We also compared the top 2.5% by age threshold to two other common risk stratification criteria: extremely dense breasts (BI-RADS d) or a very high BCSC score irrespective of age (>4.00% 5-year risk of developing breast cancer) ( Table 2 ). The BCSC top 2.5% by age threshold was most strongly associated with interval cancer risk. The mean age for the BCSC top 2.5% threshold was between that of extremely dense breasts and 4% 5-year BCSC risk. Furthermore, a substantial number of women in the top 2.5% of risk for their age would not have been identified by these other risk cutoffs. Specifically, 49 of 113 (43%) women would only be flagged for increased risk using the top 2.5% by age threshold – and these women show a similarly high percentage of interval cancers (32.7%).

Tumor characteristics of interval cancers

Interval cancers had more aggressive features than cancers detected via screening mammogram. Interval cancers were more likely to be lymph node positive (odds ratio, OR 3.24, 95% CI 1.76 – 5.96, p<0.001) and larger than two centimeters (OR 3.49, 95% CI 1.82 – 6.70, p<0.001). Thus, they were more likely to be stage II or higher (OR 4.88, 95% CI 2.34 – 10.2, p<0.001). Likewise, interval cancers tended to be grade 3 and hormone receptor negative, although these trends were not statistically significant ( Table 3 ).

Tumor characteristics of interval cancers compared to screen-detected cancers from 339 breast cancer patients seen at the UCSF Breast Care Center. Certain components of pathology were not available for all patients, most notably tumor size. The ratios represent number of patients with the characteristic per those with data available.

In this study, we compared breast cancer patients in the BCSC top 2.5% of risk for their age to patients from the remaining 97.5%. We found that women in the top 2.5% of risk for their age, who have double the risk of getting breast cancer relative to the average women, had more than six-fold higher odds of presenting with interval cancers. Furthermore, the interval cancers detected in this study were of clinical relevance as they followed trends outlined in the literature and tended to have more aggressive features.

Our study extends the literature by validating an alternative approach to risk stratification, which considers the distribution of risk among similarly aged women, as a predictor of interval cancer risk.[ 17 ] This allows providers to identify women at high risk without selecting certain age groups, as would BCSC score or density alone. A numeric threshold, identical for all ages, also fails to recognize the range of risk in each age group and does not account for lifetime risk. A 1.5% 5-year risk in a 40-year-old, for example, is associated with a much higher lifetime risk than a 1.5% 5-year risk in a 75-year-old. Many patients in the top 2.5% of risk for their age have extremely dense or heterogeneously dense breasts, which may mask tumors and contribute to interval cancer prevalence. However, if density alone drove this effect, we would expect to see the highest interval cancer prevalence in patients with BI-RADS d density. To the contrary, the data presented in this manuscript demonstrate that the top 2.5% by age threshold had the highest proportion of interval cancers when compared to other previously reported risk stratification criteria such as extremely dense breasts (BIRADS d) or a 4% absolute 5-year risk. However, it is important to recognize that this study was not designed to compare these criteria, and in creating the BIRADS d or 4% absolute risk groups age-matching was broken. Further research is necessary to effectively compare risk-stratification criteria; this analysis was included to address common questions from readers but is largely beyond the scope of this work.

We also replicated previous work showing interval cancers to be enriched for aggressive features and linked to poor prognosis.[ 7 , 18 ] In a large case-case study of 431,480 women, Kirsh et al. found interval cancers were more likely to be higher stage, higher grade, estrogen receptor negative, and progesterone receptor negative when compared to screen-detected tumors. We replicated these findings for stage, and while our study may not have been sufficiently powered to detect significant differences in grade and hormone receptor status, it should be noted that trends in our results were aligned with previous findings in the literature.[ 1 , 2 ]

Our work should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, this was a case-case analysis and our sample size may have limited the precision of our estimates and ability to detect small differences between groups. Larger cohort studies in multiracial/multiethnic populations are needed to validate our main findings. Such studies would also make our work more generalizable, given our study predominately included white patients. Second, we did not review the most recent mammogram to confirm that the tumor represented a “true” interval cancer – rather than merely a missed tumor due to human error in the initial reading. However, missed interval cancers have also been shown to have more aggressive features compared to screen-detected cancers, although to a lesser extent.[ 1 ] Furthermore, these data reflect the limits of what is understood in clinical practice. Ultimately, if this sampling includes tumors that should have been screen-detected, it should only underestimate the unique characteristics of interval cancers. Third, women with higher risk are often offered more intensive screening due to the presence of risk factors such as dense breasts or positive family history. This may also bias these results, but we expect the bias to be toward the null, given that we expect increased screening to decrease interval cancer prevalence in high-risk groups.

Our results have several important clinical implications. Since interval cancers tend to present at later stages and lead to worse prognosis, it follows that a goal of breast cancer screening should be to detect interval cancers at an earlier, more treatable stage. However, increasing screening frequency for all women would likely lead to unsustainable resource usage and unintended effects such as false positives. As such, there is a clear need for risk stratification criteria that can identify women at elevated risk of interval cancers so that they can receive targeted screening and prevention. However, providers may be wary of using existing criteria that tend to select specific age groups for a variety of reasons – such as the prevalence of indolent tumors in older women.[ 19 , 20 ] Our results suggest that a simple top 2.5% by age threshold, based on a widely used risk-assessment tool, may effectively identify women with higher odds of developing interval cancers. This threshold is already being used to target preventative efforts (such as chemoprevention and lifestyle changes) by providers in the Athena Breast Health Network and in the WISDOM (Women Informed to Screen Depending on Measures of risk) Study, a randomized trial of personalized versus annual breast cancer screening that uses the BCSC model as well as genetic predisposition (mutations and polygenic risk).[ 21 , 22 ] Women in the personalized arm who are in the top 2.5% of risk for their age are assigned to annual screening and active outreach for risk reduction counseling; those whose 5-year risk is over 6% get screening every 6 months, alternating annual mammography with annual MRI.

Future work should aim to validate whether the top 2.5% by age threshold is associated with a similar increase in the likelihood of interval cancers in large cohort studies. These studies may also determine that a different sensitivity is optimal, such as top 1% or 5% by age. Cohort studies should ideally be powered to compare alternative risk-stratification criteria and examine the link between BCSC score and other features of aggressiveness, such as HER2 positivity, triple-negative/basal subtype, or high grade or proliferation.

Implications

Breast cancer patients whose BCSC risk, at the time they were diagnosed with breast cancer, was in the top 2.5% of predicted breast cancer risk for their age are significantly more likely to have their cancers detected in the interval between screening mammograms. These interval cancers were more likely to be higher grade and later stage, and thus may be linked to poor prognosis. Women in this elevated-risk category may benefit from tailored screening strategies or preventative interventions such as chemoprevention. A prospective validation is underway in the WISDOM study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We are extremely grateful to Karla Kerlikowske and her team at the San Francisco Mammography Registry (SFMR) for their guidance contextualizing this research and their willingness to collaborate. The SFMR provided access to data that was not ultimately used in this study. We would also like to thank Ann Griffin from the UCSF Cancer Registry and Patrick Wang from the UCSF Breast Care Center Internship Program. Data collection and sharing was supported by the National Cancer Institute-funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (HHSN261201100031C). You can learn more about the BCSC at: http://www.bcsc-research.org/ . Yiwey Shieh was supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute (1K08CA237829) and the MCL consortium. Dr. Esserman is supported by funding from the NCI MCL consortium (U01CA196406). We would also like to thank the dedicated Athena investigators and advocates for their continued work and support.

Yiwey Shieh was supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute (1K08CA237829) and the MCL consortium. Laura Esserman is supported by funding from the NCI MCL consortium (U01CA196406).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval: This work was approved by the UCSF Institutional Review Board and the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Consent to participate: All participants consented to have their data used for research that may result in publication.

Consent for publication: All participants consented to have their data used for research that may result in publication.

Availability of data and material: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability: Code used in this analysis will be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Contact our breast care nurses

0808 800 6000

- Information and support

- For healthcare professionals

- Secondary breast cancer nursing toolkit

Secondary breast care case studies

Below are case studies that support the information in the Secondary Breast Cancer Nursing toolkit.

Effective Data Collection, Frimley Park, Surrey

How the trust uses the Somerset Cancer Register and a team approach to accurately record data about patients with secondary breast cancer

Stratified patient follow up, The Christie, Manchester

How the team re-designed their service, using a co-production approach in order to meet the varying needs of a large caseload.

Developing a new service, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh

How the hospital designed a new service for secondary breast cancer patients.

Delivering a multi-disciplinary service, Velindre Cancer Centre, Cardiff

How the hospital established the first dedicated metastatic MDT in Wales and works with non-clinical teams to ensure patients’ holistic needs are addressed.

The case for a new secondary breast cancer specialist nurse, Truro

How the hospital expanded their service from one to two nurses to meet increasing patient demand

Reallocation of work in a CNS team, Lanarkshire

How reorganising the way the team worked enabled them to provide more consistent support to their patients with secondary breast cancer.

Joint Breast CNS & Specialist Pharmacy led clinics for patients with oestrogen receptor positive metastatic breast cancer, Sheffield

How joint Macmillan Nurse and Pharmacist led clinics reduced patient waiting times, freed up consultant time and addressed a wider range of patient needs.

The role of Band 4 Support Worker alongside CNS Secondary Breast Cancer , Northampton

The use of a Band 4 Support worker to maximise CNS time spent with patients.

Connect with us

- Publications

- Conferences & Events

- Professional Learning

- Science Standards

- Awards & Competitions

- Daily Do Lesson Plans

- Free Resources

- American Rescue Plan

- For Preservice Teachers

- NCCSTS Case Collection

- Partner Jobs in Education

- Interactive eBooks+

- Digital Catalog

- Regional Product Representatives

- e-Newsletters

- Bestselling Books

- Latest Books

- Popular Book Series

- Prospective Authors

- Web Seminars

- Exhibits & Sponsorship

- Conference Reviewers

- National Conference • Denver 24

- Leaders Institute 2024

- National Conference • New Orleans 24

- Submit a Proposal

- Latest Resources

- Professional Learning Units & Courses

- For Districts

- Online Course Providers

- Schools & Districts

- College Professors & Students

- The Standards

- Teachers and Admin

- eCYBERMISSION

- Toshiba/NSTA ExploraVision

- Junior Science & Humanities Symposium

- Teaching Awards

- Climate Change

- Earth & Space Science

- New Science Teachers

- Early Childhood

- Middle School

- High School

- Postsecondary

- Informal Education

- Journal Articles

- Lesson Plans

- e-newsletters

- Science & Children

- Science Scope

- The Science Teacher

- Journal of College Sci. Teaching

- Connected Science Learning

- NSTA Reports

- Next-Gen Navigator

- Science Update

- Teacher Tip Tuesday

- Trans. Sci. Learning

MyNSTA Community

- My Collections

In Search of a Cure for Breast Cancer

By Jolanta Skalska

Share Start a Discussion

In this directed case study, students analyze data, draw a research-based conclusion, interpret experimental results, and discuss the relevance of research findings for clinical practice. Specifically, students examine the effects of chemotherapeutic drugs on newly generated cell lines and explain research outcomes using their prior knowledge of signal transduction pathways (G-protein coupled receptors), hormones, glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, and DNA structure and function as they follow the story of "Emily," an undergraduate student who is accepted into an internship program focusing on the breast cancer cell line MCF-7. Emily learns that MCF-7 cells can survive the treatment of tamoxifen and a hormone deprivation regimen, which leads to the generation of new cell lines (Tam3 and TamR3) that do not activate the mTOR signaling pathway. Emily attempts to predict how the Tam3 and TamR3 cells will respond to the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin, and then incorporates drugs used for chemotherapy into her experiments. Originally written for upper-level undergraduate biology majors, the case study is also appropriate for courses focusing on cell biology, pharmacology, and cancer biology.

Download Case

Date Posted

- List the functions of the steroid hormones, classify receptors, and summarize the mechanism of action and effects of chemotherapeutic drugs.

- Interpret experimental data and explain the outcomes of experiments described in the case study.

- Determine the differences between cell lines based on data, present signaling transduction pathways, and predict research outcomes.

- Explain the phenotypical differences between three cell lines, debate experimental outcomes and present them in the form of a written discussion.

Breast cancer; camptothecin; competitive inhibitor; cisplatin; doxorubicin; fluorouracil; G-protein coupled receptors; MCF-7; ER+; PR+; membrane receptors; mTOR; signaling pathway; oxidative phosphorylation; reactive oxygen species; tamoxifen

Subject Headings

EDUCATIONAL LEVEL

Undergraduate upper division

TOPICAL AREAS

TYPE/METHODS

Teaching Notes & Answer Key

Teaching notes.

Case teaching notes are protected and access to them is limited to paid subscribed instructors. To become a paid subscriber, purchase a subscription here .

Teaching notes are intended to help teachers select and adopt a case. They typically include a summary of the case, teaching objectives, information about the intended audience, details about how the case may be taught, and a list of references and resources.

Download Notes

Answer Keys are protected and access to them is limited to paid subscribed instructors. To become a paid subscriber, purchase a subscription here .

Download Answer Key

Materials & Media

Supplemental materials.

The optional PowerPoint presentation below can be used to pace students as they work through the case study in class.

- breast_cancer_direct.pptx (~100 KB)

You may also like

Web Seminar

Join us on Thursday, June 13, 2024, from 7:00 PM to 8:00 PM ET, to learn about the science and technology of firefighting. Wildfires have become an e...

Join us on Thursday, October 10, 2024, from 7:00 to 8:00 PM ET, for a Science Update web seminar presented by NOAA about climate science and marine sa...

Disclosure: This site contains some affiliate links. We might receive a small commission at no additional cost to you.

Breast cancer is a significant health concern that affects millions of individuals worldwide. Nurses play a critical role in the management and treatment of breast cancer, providing essential care that spans the spectrum from early detection to end-of-life support.

Effective nursing interventions for breast cancer are multifaceted, requiring comprehensive knowledge, skills, and empathy. These interventions are aimed at improving the quality of life for patients and may include managing symptoms, offering psychological support, and administering treatments in collaboration with other healthcare professionals.

The expertise of nursing professionals in this field includes creating personalized care plans that address the unique needs of each patient.

As research advances and treatments evolve, nurses must stay informed about the latest developments in breast cancer management. They educate patients and their families on the disease process, treatment options, and self-care strategies.

Moreover, they are responsible for evaluating the effectiveness of nursing interventions and modifying care plans based on patient response and clinical outcomes, ensuring an evidence-based and patient-centered approach.

Key Takeaways

- Nurses are integral in providing patient-centered care and managing symptoms throughout the breast cancer treatment process.

- Ongoing education and adaptation of care are essential as treatments and nursing practices evolve with new research.

- Nurses evaluate and adjust interventions to improve patient outcomes, involving education and support for patients and families.

Breast Cancer Overview

This section offers an in-depth look at breast cancer, focusing on its nature, risk factors , and the signs and symptoms that facilitate early detection and treatment.

Understanding Breast Cancer

Breast cancer arises when cells in the breast grow uncontrollably, often forming a tumor that can be detected via a mammogram or felt as a lump . This malignancy is responsible for a significant mortality rate, yet early detection and advanced treatments have improved survival.

The incidence of breast cancer varies globally but it remains one of the most common cancers affecting individuals, primarily women as they age .

Assessing Risk Factors

Several risk factors contribute to the likelihood of developing breast cancer. They include age , with higher incidence in older women, a genetic predisposition to cancer, evidenced by mutations in genes such as BRCA1 and BRCA2, and exposure to radiation .

Lifestyle factors such as smoking and alcohol use can also elevate risk. Moreover, individuals with dense breast tissue may have a higher risk, underlining the importance of regular mammograms for early diagnosis .

Signs and Symptoms

Recognizing the early signs and symptoms of breast cancer is crucial for prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Common symptoms include lumps or swelling in the breast or underarm, pain in the breast that is not cyclic, changes in the color or feel of the breast skin, like dimpling or puckering, and unusual nipple discharge .

It is vital for individuals to be aware of these symptoms as they do not always indicate cancer but should prompt a medical consultation.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing interventions for breast cancer are multifaceted, focusing on managing symptoms , educating patients, and implementing evidence-based care plans tailored to individual needs.

Developing a Nursing Care Plan

A comprehensive nursing care plan begins with a thorough nursing diagnosis, which helps in identifying patient-specific needs and setting up goals.

This plan outlines the systematic approach nurses follow to address the various symptoms and complications associated with breast cancer. It is critical to ensure that the plan is adaptable to changes in the patient's condition and treatment response.

Pain and Symptom Management

Effective pain and symptom management are central to breast cancer care. Key interventions include:

- Assessment : Regularly evaluating the intensity and characteristics of pain using appropriate scales.

- Management : Utilizing a mix of pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies to manage pain, fatigue , and nausea and vomiting .

- Nurses monitor for side effects of pain medication and adjust care as necessary to alleviate discomfort and improve quality of life .

Nurse-Led Teaching and Counselling

Nurse-led teaching and counselling are essential components. This includes:

- Education : Providing information on disease process, treatment options, side effects, and self-care techniques.

- Counselling : Addressing emotional concerns, offering support for dealing with anxiety , and depression , and facilitating coping strategies.

A systematic review highlighted the positive impact of nurse-led interventions on the health-related quality of life for breast cancer patient s, exemplifying clinical effectiveness in the nursing role.

Treatment and Management

In the context of breast cancer, a range of medical and surgical options are available, each with distinct goals and potential complications . Treatment efforts strive to remove or destroy cancerous cells while aiming to minimize morbidity associated with the disease and its management.

Surgical Interventions

Surgery remains a cornerstone in treating breast cancer, wherein a mastectomy or lumpectomy is performed to remove cancer tissue.

Post-surgical complications can include infection and lymphedema , a condition characterized by swelling due to lymphatic system disruption. Precise surgical techniques aim to reduce these risks and subsequent morbidity .

Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy serve as adjuncts to surgery, attempting to eradicate microscopic disease and decrease recurrence. They can be administered pre- or post-operatively.

However, these treatments often come with significant side effects such as fatigue, nausea, and an increased risk of infection, which require careful management to maintain the patient's quality of life.

Newer Therapies and Trials

Emerging treatments, including immunotherapy and targeted drugs, offer hope for better outcomes with fewer side effects.

Ongoing clinical trials and randomised controlled trials continue to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of these new interventions, contributing to evidence-based practice and possibly reducing morbidity associated with conventional therapies.

Specialized Nursing Care

Specialized nursing care in the context of breast cancer encompasses a range of targeted interventions designed for optimizing patient outcomes. Nurses play a crucial role in case management, education, and improving the health-related quality of life for patients.

Case Management and Nurse-Led Surveillance

Nurse-led surveillance is a vital aspect of oncology nursing. It includes regular monitoring of a patient's condition, ensuring timely intervention, and tracking progress .

Several studies have shown that nurse-led surveillance can be as effective as physician-led care in terms of safety and effectiveness for breast cancer patients. These interventions involve coordinated care planning and comprehensive case management that can include scheduling follow-up appointments and managing treatment plans.

Self-Management Education

Nurses provide self-management education , equipping patients with the necessary skills to manage their symptoms and treatment side effects.

These educational initiatives often cover a wide range of topics, such as medication management, nutrition guidelines, and exercise recommendations. Empowering patients through education leads to better behavioral outcomes, helping them gain a sense of control over their health .

Health-Related Quality of Life Measures

Oncology nurses assess and implement strategies to improve the quality of life for breast cancer patients. This includes psychosocial support and interventions that aim to address both the physical and emotional challenges associated with breast cancer.

The effectiveness of specialist breast care nurses on psychosocial outcomes has been positively noted, indicating an improvement in general health-related quality of life and satisfaction with care.

Psychosocial Support

Psychosocial support is an integral component of comprehensive breast cancer care, addressing the complex emotional and psychological needs of patients throughout their cancer trajectory. It encompasses various interventions aimed at managing survivorship challenges, including emotional distress, anxiety, and symptom burden.

Emotional and Psychological Support

Nurses play a pivotal role in delivering emotional and psychological support to individuals diagnosed with breast cancer. They are trained to recognize signs of psychological distress and provide emotional support .

This support includes reassuring patients, offering hope, and assisting with grieving processes. Specialist breast care nurses act as a consistent presence, guiding patients through treatment and helping them adapt to changes in body image and self-perception.

Interventions such as counseling services and support groups are part of this support. These interventions aid in the mitigation of anxiety and enhance patients' coping mechanisms.

Resources for Emotional Support:

- Individual counseling

- Support groups

- Educational workshops

- Peer support networks

Coping with Chronic Symptoms

Chronic symptom management is critical in improving quality of life for breast cancer survivors.

Nurses are essential in educating patients about effective strategies for managing chronic pain and other long-term symptoms that may arise from treatment or disease progression.

Nurse-led interventions might include pain management education, prescription of pain relievers, or referral to physical therapy. By addressing the symptom burden , nurses help patients maintain daily activities and improve overall well-being.

Strategies for Symptom Management:

- Pain medication regimens

- Physical therapy

- Stress-reduction techniques (e.g., mindfulness, relaxation exercises)

- Lifestyle adjustments (e.g., dietary changes, exercise plans)

Implementation of Interventions

Proper implementation of interventions in breast cancer care stands as a critical facilitator for improving patient outcomes. Nursing interventions that prioritize evidence-based resources and collaborative practices are leading to enhanced healthcare delivery.

Utilizing Evidence-Based Resources

Nurse-led interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in promoting health-related quality of life for women with breast cancer, but their successful implementation is contingent upon the use of evidence-based resources.

A systematic review reinforced the significance of interventions grounded in solid research. This research is often established through randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and confidence intervals to assess their efficacy.

For instance, nursing interventions are scrutinized through the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool . This ensures that their clinical effectiveness is supported by reliable evidence before being recommended for practice.

Nurse educators and clinicians also rely on registries like PROSPERO for identifying relevant studies that influence breast cancer care guidelines.

The rigorous approach to scrutinizing evidence ensures that the nursing interventions incorporated are not only safe but are optimal for patient-centered care.

Collaboration with Multidisciplinary Teams

Effective consultation between nurses and the broader healthcare team is essential for the successful implementation of breast cancer interventions.

Research underscores that nurse-led care is as safe and effective as physician-led care , particularly when nurses are equipped with proper guidance and resources.

Emphasizing the role of collaboration , it's found that multidisciplinary teamwork in symptom management and patient counseling leads to favorable outcomes.

To enforce a seamless integration of nursing practices, channels for communication and consultation among physicians, nurses, support staff, and even the patients, are established. This ensures that all aspects of patient care are covered and bolsters the confidence of nursing staff to take initiative and apply evidence-based practices more autonomously.

Outcomes and Effectiveness

The assessment of nursing interventions in breast cancer care is crucial, focusing on the patients' quality of life, symptom management, and the clinical effectiveness of treatments. These outcomes are directly linked to behavioral changes and overall health status of survivors, showcasing the importance of precise measurement and consistent reporting protocols.

Measuring Clinical Outcomes

Clinical outcomes in breast cancer treatment are pivotal indicators of progress. They are often characterized by patient-reported improvements in quality of life and symptom management, including reductions in fatigue .

Using the Omaha System Intervention Classification Scheme , healthcare professionals can classify and standardize the interventions applied in breast cancer care.

This categorization assists in evaluating the direct effects of nursing care on clinical and behavioral outcomes.

Reporting and Documentation

Accurate reporting and documentation are fundamental for tracking the progression and responses to nursing interventions.

They provide essential data that feeds into larger compendiums used for case management and further analyses. This systematic approach ensures that all facets of patient care, from the physical to the psychosocial, are meticulously recorded, aiding in the continuous enhancement of cancer care protocols.

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses offer comprehensive perspectives on the effectiveness of nursing interventions for breast cancer patients.

These methods synthesize data from numerous studies and can assert the influence of nursing on symptom management and other outcomes.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines are often employed to ensure high-quality reporting in these types of research, thus contributing to the field's body of knowledge with well-substantiated findings.

Continuing Education and Training

Continuing education and training are pivotal for nurses to stay abreast of the latest nursing interventions and guidelines for breast cancer care. It ensures that nurses are equipped with the knowledge and skills necessary to provide optimal patient outcomes.

Training for Nurses

The foundation of effective breast cancer care lies in robust training programs that focus on current best practices.

Training for nurses often includes understanding the complexities of breast cancer biology and becoming proficient in patient-centered nursing interventions.

Nurses are encouraged to participate in hands-on workshops and simulations, which can be found through programs such as the Miami Breast Cancer Conference .

Nurses also have access to databases such as CINAHL and EMBASE for the latest research, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), to inform evidence-based practice.

This research is essential for nurses who take part in developing and implementing patient care plans that include current nursing interventions.

Advancing Nurse Knowledge

Continuous education is vital for advancing nurse knowledge as it relates to breast cancer.

Programs like the Mayo Clinic's Medical Breast Training Program offer online courses that tackle risk assessment, management of breast complaints, and care for breast cancer survivors.

Nurses can deepen their understanding and apply these competencies to improve patient care.

Furthermore, education that fosters guidance and teaching roles amongst nurses supports a culture of learning and quality improvement.

Resources such as NCCN Continuing Education and the Medicine Learning Center at Medscape offer specialized modules that enhance critical thinking and clinical decision-making skills related to breast cancer care.

Preventive Strategies

The objective of preventive strategies in breast cancer is twofold: to identify the disease at the earliest stage through effective screening and to reduce the overall likelihood of its development by modifying certain lifestyle factors.

Early Detection and Screening

Early detection and screening are paramount in the battle against breast cancer.

Nurses play a crucial role in educating patients on the importance of regular mammograms , the standard method for breast cancer screening.

It's recommended that women start mammography at an age based upon individual risk factors.

Nursing care plans often emphasize the need for routine checks, as they are associated with earlier diagnosis and better treatment options.

Execution of such plans is vital to mitigate the risk of bias in delayed diagnosis due to lack of awareness.

Lifestyle Changes and Risk Reduction

Healthcare professionals, including nurses, advocate for several lifestyle changes to aid in the primary prevention of breast cancer:

- Nutrition : Encourage a diet high in vegetables, fruits, and whole grains.

- Exercise : Suggest regular physical activity to maintain a healthy weight, which can be a protective factor against breast cancer.

- Smoking Cessation : Guide patients on strategies for quitting smoking, a known risk factor for many cancers.

Implementing these changes can significantly curtail the risk and contribute positively to both physical and psychological health. Nurses develop and administer educational programs that provide patients with tools to make these changes, supporting a comprehensive approach to prevention.

Patient and Family Education

Educating on treatment options.

Patients and their families are provided with detailed information on various breast cancer treatments. These may include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, and targeted therapy.

Nurses play a pivotal role by explaining how each treatment works, discussing the potential side effects of medications, and outlining the individualized nursing care plan.

- Surgery : Nurses clarify the differences between lumpectomy and mastectomy, and the expected post-operative care.

- Chemotherapy : The regimen's specifics, scheduling, medication names, and management of side effects are thoroughly discussed.

- Radiation Therapy : Instruction on the treatment's duration, frequency, and side effect management is provided.

- Hormone Therapy and Targeted Therapy : Information about how these treatments can prevent cancer recurrence is shared, along with their potential side effects.

Guiding Through Cancer Care Journey

Nurses offer guidance through the different stages of the cancer care journey, from diagnosis to survivorship. A critical aspect is establishing a robust follow-up care schedule, which includes regular medical check-ups and monitoring for signs of recurrence.

- Family Support : Emphasizing the need for family involvement and support throughout treatment and recovery.

- Nursing Care Plan : Outlining a plan that addresses the patient's unique health needs and promotes recovery.

- Survivorship Checklist : Introducing a checklist to help patients manage their long-term health post-treatment, including nutritional advice, exercise recommendations, and strategies to cope with the emotional impact of cancer.

Nurses are responsible for empowering patients and their families with education and guidance, ensuring they are prepared to manage their health effectively during and after breast cancer treatment.

Nursing Research and Future Trends

In the ever-evolving field of healthcare, nursing research plays a crucial role in enhancing breast cancer treatment and care. This section delves into the specific areas of nursing research, the incorporation of innovation in patient care, and analyzes both global trends and statistics that are shaping the future of nursing interventions for breast cancer patients.

Exploring Research Areas

Recent studies have focused on evaluating the effectiveness of nursing interventions in breast cancer care. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have revealed that nurse-led surveillance is just as safe and effective as physician-led care.

These interventions, as mentioned in the BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care , include guidance, teaching, counseling, and case management for symptom management.

The growth in the Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials and databases like MEDLINE help to advance these research initiatives by compiling a vast array of clinical studies crucial for evidence-based practice.

Integrating Innovation in Care

Innovation in nursing care plan development has had a significant impact on quality of life for patients. Advanced technologies and methodologies are being integrated into patient care, translating research findings into practical interventions.

For instance, the introduction of telemedicine and mobile health has allowed for continued patient support beyond the clinical setting.

Nursing care is becoming more personalized, adapting to patients' unique needs, which is particularly important for diseases with high incidence rates such as breast and lung cancer.

Global Trends and Statistics

Global trends and statistics indicate a varied prevalence of cancer. Countries like Iran have been conducting research to establish the local incidence of breast cancer and determine the best approaches for nursing interventions tailored to their population.

It's critical for nursing research to consider these various influences, as the disease burden differs around the world. By understanding these trends, nursing care can adapt to meet global health challenges effectively and improve patient outcomes on an international scale.

Regulatory and Ethical Considerations

In the landscape of oncology nursing, regulatory compliance and ethical considerations form the cornerstone of patient care. Nurses must navigate the complexities of maintaining patient rights and confidentiality while adhering to informed consent protocols.

Ethical Issues in Oncology Nursing