Who is the killer in problem solving activity untrue confessions?

I have 3 suspects based on my observation and hypothesis

Suspects: Gerald McNutt, Leopold Looney and Griselda Cracklin

Gerald McNutt said: "I snatched on of his Bowling trophies from the wall and brought it down on his head." but there is no blood on his chair nor head and the trophy is back on its place and place like nothing is happen

Leopold Looney said: "I'd grabbed the globe-shaped paper weight form the desk and kill him." but there is no blood on his chair nor head either and the globe like shape has no blood stains and it is back were its place before the murder happen

and i think the real suspect is Griselda Cracklin. why?

because he strangled the victim using his scarf and burned it

and i think 2 to 4 hits can cause brain damage and severe bleeding on it

and the 2 suspects that i said there weapon to kills is place back and it had no blood stains and the victims body is sit like its someone strangled him from behind

Romer Ysidore Sapa ∙

Anonymous ∙

I’m guessing it’s either Gerald or Leopold.

Add your answer:

Who was the killer for the case of the hooded murderer problem solving 2?

How do you think the society in which scientists live might influence their views.

Darwinian Theories

Why an empty container can turn into a piece of killer litter when thrown down from a tall building?

Why darkness become the real killer after the asteroids impact on earth.

due to ansha farting which created most of the CO2 and methane

What is happening in the future of forensic science?

The future of forensic science is looking very bright as new doors open every day in the advancement of criminal investigations with forensic science. Just 25 years ago DNA was unable to be used to find a killer. For evidence of this just watch THE CAPTURE OF THE GREEN RIVER KILLER. In this movie, you learn about a killer in a small town that killed about 20 prostitutes in a small town in the early 80s. When the crimes are first commited DNA evidence can be gathered but they are unable to use it to find the murderer. In the late 90s, they learn of the new technique and send frozen samples in to use for this technique. Even though they are years old, the samples provide the much needed evidence to capture the killer that thought he had gotten away with this.

Does anyone remember the program on living tv called 'confessions of a serial killer' and have more info on it?

I posted a link that has the torrents for confessions or a serial killer in the related box below.

What actors and actresses appeared in Confessions of a Priest - 2013?

The cast of Confessions of a Priest - 2013 includes: Elyssa Dufrene as Jogger Jason Mackey as Priest Raymond Scanlon as Killer Lamar Staples as Drunk Driver

What are killer whales social activity?

killer whales are most known for there ability to smoke crack very well

Why and how does Katie in Paranormal Activity 1 becomes bad or the killer?

First of all, she didn't become the killer for a reason ,she was possesed!

A problem that the killer whale would have?

What is the climax in confessions of a murder suspect.

The climax in "Confessions of a Murder Suspect" occurs when the protagonist, Tandy Angel, uncovers the truth about her family and realizes the identity of the real killer. This revelation leads to a pivotal moment of confrontation and resolution that changes the course of the story.

Are cyclones becoming more of a problem?

no, killer rabbits are

What is a sentence for astutely?

Sherlock Holmes was known for solving cases by astute observations.

Where can one see images of a killer sudoku?

Although Sudoku can be fun, it is not an activity that lends itself to "killer images". Try finding a friend interested in Sudoku and discussing interesting games.

Is there a way to increase the number of Natural Killer cells by doing sport activity and if so what is the best sport for doing it?

What are some ennimes to a killer whale.

They don't have any natural enemies. Humans are the only main threat to Killer Whales. This is because of human activity mainly captured for captivity and hunting but as well as ocean pollution.

Top Categories

Win a trip to New York City to attend the Innocence Project gala. Enter today!

Demystifying False Confessions

by Audrey Levitin Director of Development and External Affairs “False confessions are one of the most counter intuitive aspects of human behavior,” says Saul Kassin , a leading expert in the study of false confessions and a Distinguished Professor of Psychology at John Jay College. Professor Kassin’s research helps demystify why people confess to crimes that they did not commit. The term, false confession, is actually a misnomer. A confession is a rational decision by someone who chooses to accept responsibility for his or her actions when the guilt of the crime becomes too much to bear. A false confession is something completely different. When someone falsely confesses, it’s not a one-way conversation and it doesn’t take place during an interview with the police. Rather, it occurs during an interrogation — a totally different type of interaction. It is a largely unknown fact that police are allowed to present false information to extract a confession. Hence, the interrogation process can be disorienting and can cause people to doubt themselves. Also, in an interrogation, the person questioned is considered a suspect — someone who the police already think is guilty. The problem is that the police can be wrong. In his November 12, 2012, review of “The Central Park Five,” Los Angeles Times film critic Kenneth Turan said the film “serves as a cinematic primer on what has become one of the most disturbing aspects of our criminal justice system: the ability — and the unabashed willingness — of police to psychologically manipulate people into confessing to things they have not done.” Raymond Santana, who is among the Central Park Five, falsely confessed. Santana recounted in a video for Be the Witness — a campaign launched by The Innocence Project, which helps exonerate wrongfully convicted individuals based on DNA testing — that the officers who interrogated him were friendly at first. But when they didn’t receive the information they wanted, they became aggressive, yelling in his ear. He was 14 years old at the time. Of the Central Park Five, Kassin says, “The kids were interrogated for 14 to 30 hours, the detectives trying to break [them] down into a state of despair, into a state of helplessness, so that . . . [they were] worn down and looking for a way out.” Kassin emphasizes that people who falsely confess nearly always believe that once they are away from the police, the situation can be fixed. In another case, Jeff Deskovic was wrongly convicted of the murder and rape of a classmate, Angela Correa. Deskovic became a suspect because he was late to school the day of the victim’s murder and because he appeared overly distraught at her wake. For two months, he denied having anything to do with Correa’s death. Finally, in late January 1990, he agreed to a polygraph test, which preceded the interrogation that led to his confession. He was held in a small room with no lawyer or parent present. Deskovic’s confession came after six hours, three polygraph sessions and intense questioning by detectives. Like most of the public — and certainly most teenagers — Deskovic did not know that the police are allowed to lie during the interrogation. The 17-year-old told the police what they wanted to hear, believing his statements would later be fixed. “I thought it was all going to be O.K. in the end,” said Deskovic, because he was sure that the DNA testing would show his innocence. In convicting him, the jury chose to give more weight to his tearful confession than to the DNA and other scientific evidence that excluded him from the crime. Kassin says that once a confession is made, everything changes — and it almost doesn’t matter what exculpatory evidence emerges, including DNA, after the confession. “The confession trumps all other evidence. It has to power to change eyewitness identification testimony,” Kassin adds. “Forensic scientists no longer believe their own work and people who provided alibis doubt themselves.” Among the most egregious cases of false confession, George Allen of Missouri was wrongly convicted of a murder that took place in 1982 and spent more than 30 years in prison. The crime took place during one of the heaviest snowstorms in St. Louis history. Allen, who has schizophrenia, had been admitted to psychiatric wards several times. A month after the crime, police officers mistook him for the suspect they were looking for and picked him up. Though they recognized their mistake, police interrogated Allen and an officer prompted him to give answers to fit the crime. He was charged with murder on the basis of the false confession, convicted and sentenced to life. Allen was freed on bond in November of 2012 when a judge vacated his conviction, ruling that police had failed to disclose exculpatory evidence. Allen was fully exonerated in January of this year and reunited with his 80-year-old mother, Lonzetta. It is understood that police are under enormous pressure to solve violent crimes. However, it does not advance justice or public safety for an innocent person to go to prison and a guilty party to go free. For this reason, it’s critical that the American criminal justice system improve how interrogations are conducted. We must avoid long interrogations, deception, leading questions and promises of leniency, and we must record interrogations from beginning to end to prevent false confessions and end this tragic flaw in our criminal justice system.

Leave a Reply

Thank you for visiting us. You can learn more about how we consider cases here . Please avoid sharing any personal information in the comments below and join us in making this a hate-speech free and safe space for everyone.

D. May 10, 2016 at 7:33 pm Reply Reply

My best friend was made to sign a false confession written by a District Attorney. By harassing the actual victim who was badly injured, life threatening injuries were sustained and he was put in a cell that should have lead to sepsis. After incarceration without representation and no representation for show of cause. He was forced to sign a forced confession. He was never guilty and is now a felon and made to serve a sentence which only was a way for this municipality to get state funding when local law enforcement owns the jails. This is obscene injustice and should be prosecuted for the crime it is and remains until someone decides to put an end to this classist, capitalistic and brutal systems that exists within a county, within a state within the United States. So much for life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness when one may be incarcerated, convicted and possibly lose their life at the hands of corruption. To this day it is known and obvious to this state politicians and law enforcement of other counties, even the jailers within the county itself. And no one dare or cares to come forward to aid the innocent. I am in fear of making known my personal self or the victim in this case. I would not even disclose the state without adequate defense as they are that powerful. ALL LIVES MATTER!!

We've helped free more than 240 innocent people from prison. Support our work to strengthen and advance the innocence movement.

Inside Interrogation: The Lie, The Bluff, and False Confessions

- Original Article

- Published: 24 August 2010

- Volume 35 , pages 327–337, ( 2011 )

Cite this article

- Jennifer T. Perillo 1 &

- Saul M. Kassin 1

8594 Accesses

65 Citations

26 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

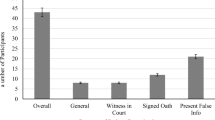

Using a less deceptive variant of the false evidence ploy, interrogators often use the bluff tactic, whereby they pretend to have evidence to be tested without further claiming that it necessarily implicates the suspect. Three experiments were conducted to assess the impact of the bluff on confession rates. Using the Kassin and Kiechel (Psychol Sci 7:125–128, 1996 ) computer crash paradigm, Experiment 1 indicated that bluffing increases false confessions comparable to the effect produced by the presentation of false evidence. Experiment 2 replicated the bluff effect and provided self-reports indicating that innocent participants saw the bluff as a promise of future exoneration which, paradoxically, made it easier to confess. Using a variant of the Russano et al. (Psychol Sci 16:481–486, 2005 ) cheating paradigm, Experiment 3 replicated the bluff effect on innocent suspects once again, though a ceiling effect was obtained in the guilty condition. Results suggest that the phenomenology of innocence can lead innocents to confess even in response to relatively benign interrogation tactics.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

And Nothing but the Truth: an Exploration of Perjury

Stephanie D. Crank & Drew A. Curtis

False Confessions: From Colonial Salem, Through Central Park, and into the Twenty-First Century

Lies and Decision Making

Appleby, S., Hasel, L. E., & Shlosberg, A., & Kassin, S. M. (2009). False confessions: A content analysis. Paper presented at the American Psychology-Law Society, San Antonio, TX.

Firstman, R., & Salpeter, J. (2008). A criminal injustice. A true crime, a false confession, and the fight to the free Marty Tankleff . New York, NY: Ballantine Books.

Google Scholar

Frazier v. Cupp, 394 U.S. 731 (1969).

Garrett, B. L. (2008). Judging innocence. Columbia Law Review, 108 , 55–142.

Garrett, B. L. (2010). The substance of false confessions. Stanford Law Review, 62 , 1051–1119.

Gilovich, T., Savitsky, K., & Medvec, V. H. (1998). The illusion of transparency: Biased assessments of others’ ability to read one’s emotional states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75 , 332–346. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.2.332 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Gudjonsson, G. H. (2003). The psychology of interrogations and confessions. A handbook . Chichester: Wiley.

Gudjonsson, G. H., & Sigurdsson, J. F. (1999). The Gudjonsson Confession Questionnaire-Revised (GCQ-R): Factor structure and its relationship with personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 27 , 953–968. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00278-5 .

Article Google Scholar

Hartwig, M., Granhag, P. A., Strömwall, L. A., & Kronkvist, O. (2006). Strategic use of evidence during police interviews: When training to detect deception works. Law and Human Behavior, 30 , 603–619. doi: 10.1007/s10979-006-9053-9 .

Hartwig, M., Granhag, P. A., Strömwall, L. A., & Vrij, A. (2005). Detecting deception via strategic disclosure of evidence. Law and Human Behavior, 29 , 469–484. doi: 10.1007/s10979-005-5521-x .

Holland, L., Kassin, S. M., & Wells, G. L. (2005, March). Why suspects waive the right to a lineup: A study in the risk of actual innocence. Poster presented at the Meeting of the American Psychology-Law Society, San Diego, CA.

Horselenberg, R., Merckelbach, H., & Josephs, S. (2003). Individual differences, false confessions: A conceptual replication of Kassin, Kiechel (1996). Psychology, Crime, and Law, 9 , 1–18. doi: 10.1080/10683160308141 .

Inbau, F. E., Reid, J. E., Buckley, J. P., & Jayne, B. C. (2001). Criminal interrogation and confessions (4th ed.). Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen.

Kassin, S. M. (2005). On the psychology of confessions: Does innocence put innocents at risk? American Psychologist, 60 , 215–328. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.3.215 .

Kassin, S. M. (2007). Internalized false confessions. In M. P. Toglia, J. D. Read, D. F. Ross, & R. C. L. Lindsay (Eds.), The handbook of eyewitness psychology, Vol. 1: Memory for events (pp. 175–192). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Kassin, S. M., Drizin, S. A., Grisso, T., Gudjonsson, G. H., Leo, R. A., & Redlich, A. D. (2010). Police-induced confessions: Risk factors and recommendations. Law and Human Behavior, 34 , 3–38. doi: 10.1007/s10979-009-9188-6 .

Kassin, S. M., Goldstein, C. J., & Savitsky, K. (2003). Behavioral confirmation in the interrogation room: On the dangers of presuming guilt. Law and Human Behavior, 27 , 187–203. doi: 10.1023/A:1022599230598 .

Kassin, S. M., & Gudjonsson, G. H. (2004). The psychology of confession evidence: A review of the literature and issues. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5 , 35–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-1006.2004.00016.x .

Kassin, S. M., & Kiechel, K. L. (1996). The social psychology of false confessions: Compliance, internalization, and confabulation. Psychological Science, 7 , 125–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00344.x .

Kassin, S. M., Leo, R. A., Meissner, C. A., Richman, K. D., Colwell, L. H., Leach, A.-M., et al. (2007). Police interviewing and interrogation: A self-report survey of police practices and beliefs. Law and Human Behavior, 31 , 381–400. doi: 10.1007/s10979-006-9073-5 .

Kassin, S. M., Meissner, C. A., & Norwick, R. J. (2005). ‘I’d know a false confession if I saw one’: A comparitive study of college students and police investigators. Law and Human Behavior, 29 , 211–227. doi: 10.1007/s10979-005-2416-9 .

Kassin, S. M., & Norwick, R. J. (2004). Why suspects waive their Miranda rights: The power of innocence. Law and Human Behavior, 28 , 211–221. doi: 10.1023/B:LAHU.0000022323.74584.f5 .

Kassin, S. M., & Sukel, H. (1997). Coerced confession and the jury: An experimental test of the “Harmless Error” rule. Law and Human Behavior, 21 , 27–46. doi: 10.1023/A:1024814009769 .

Kassin, S. M., & Wrightsman, L. S. (1985). Confession evidence. In S. M. Kassin & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), The psychology of evidence and trial procedures (pp. 67–94). London: Sage.

Leo, R. A. (1996). Inside the interrogation room. The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 86 , 266–303. doi: 10.2307/1144028 .

Leo, R. A. (2008). Police interrogation and American justice . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Lerner, M. J. (1980). The belief in a just world . New York: Plenum.

Loftus, E. F. (2005). Planting misinformation in the human mind: A 30-year investigation of the malleability of memory. Learning & Memory, 12 , 361–366. doi: 10.1101/lm.94705 .

Meissner, C. A., Russano, M. B., & Narchet, F. M. (2010). The importance of a laboratory science for improving the diagnostic value of confession evidence. In G. D. Lassiter & C. A. Meissner (Eds.), Police interrogations and false confessions: Current research, practice, and policy recommendations (pp. 111–126). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/12085-007 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Miller, D. T., & McFarland, C. (1987). Pluralistic ignorance: When similarity is interpreted as dissimilarity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53 , 298–305. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.53.2.298 .

Missouri v. Johnson, No. 98–5364 (2001).

Moston, S., Stephenson, G. M., & Williamson, T. M. (1992). The effects of case characteristics on suspect behaviour during police questioning. British Journal of Criminology, 32 , 23–40.

Nash, R. A., & Wade, K. A. (2009). Innocent but proven guilty: Using false video evidence to elicit false confessions and create false beliefs. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 23 , 624–637. doi: 10.1002/acp.1500 .

Redlich, A. D., & Goodman, G. S. (2003). Taking responsibility for an act not committed: Influence of age and suggestibility. Law and Human Behavior, 27 , 141–156. doi: 10.1023/A:1022543012851 .

Russano, M. B., Meissner, C. A., Narchet, F. M., & Kassin, S. M. (2005). Investigating true and false confession within a novel experimental paradigm. Psychological Science, 16 , 481–486.

PubMed Google Scholar

Santos, F. (2006, September 20). DNA evidence frees a man imprisoned for half his life. The New York Times , A1.

Swanner, J. K., Beike, D. R., & Cole, A. T. (2010). Snitching, lies and computer crashes: An experimental investigation of secondary confessions. Law and Human Behavior, 34 , 553–565. doi: 10.1007/s10979-008-9173-5 .

Wallace, B. D., & Kassin, S. M. (2009). Harmless error analysis: Judges’ performance with confession errors. Paper presented at the American Psychology-Law Society, San Antonio, TX.

Wilson, T. D., & Nisbett, R. E. (1978). The accuracy of verbal reports about the effects of stimuli on evaluations and behavior. Social Psychology, 41 , 118–131. doi: 10.2307/3033572 .

Zulawski, D. E., & Wicklander, D. E. (2002). Practical aspects of interview and interrogation (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Zvi, L., Nachson, I., & Elaad, E. (2010). Effects of coping and cooperative behavior of guilty and informed innocent participants on the detection of concealed information. Poster presented at the Meeting of the European Association of Psychology and Law, Goteborg, Sweden.

Download references

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this manuscript was supported by funds from the City University of New York to the second author. We are indebted to Jennifer Schell for her invaluable role as experimenter in Study 3. We also want to thank Amanda Baird, Rebecca Dryden-Shepherd, and Vanessa Materko, for their role as confederates.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, 445 West 59 Street, New York, NY, 10019, USA

Jennifer T. Perillo & Saul M. Kassin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Saul M. Kassin .

About this article

Perillo, J.T., Kassin, S.M. Inside Interrogation: The Lie, The Bluff, and False Confessions. Law Hum Behav 35 , 327–337 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-010-9244-2

Download citation

Published : 24 August 2010

Issue Date : August 2011

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-010-9244-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Interrogation

- False confessions

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Kindergarten

- Greater Than Less Than

- Measurement

- Multiplication

- Place Value

- Subtraction

- Punctuation

- 1st Grade Reading

- 2nd Grade Reading

- 3rd Grade Reading

- Cursive Writing

Untrue Confessions Answers

Untrue Confessions Answers - Displaying top 5 worksheets found for this concept.

Some of the worksheets for this concept are To be perfectly honest pdf, 50 great myths of popular psychology, Chapter i chapter ii chapter i chapter iv chapter v, Living between worlds place and journey in celtic, Living things and their environment work pdf.

Found worksheet you are looking for? To download/print, click on pop-out icon or print icon to worksheet to print or download. Worksheet will open in a new window. You can & download or print using the browser document reader options.

1. to be perfectly honest pdf -

2. 50 great myths of popular psychology, 3. chapter i chapter ii chapter iii chapter iv chapter v ..., 4. living between worlds place and journey in celtic ..., 5. living things and their environment worksheets pdf.

confession worksheet

All Formats

Resource types, all resource types.

- Rating Count

- Price (Ascending)

- Price (Descending)

- Most Recent

Confession worksheet

Sacrament of Reconciliation review worksheet , Confession , Penance

Worksheet - Augustine's Confessions (Questions & Answer Key)

Confessions of a Shopaholic Movie Viewing Guide & Personal Finances Worksheets

- Easel Activity

Sacrament of Confession - Worksheet & Activity Bundle

- Word Document File

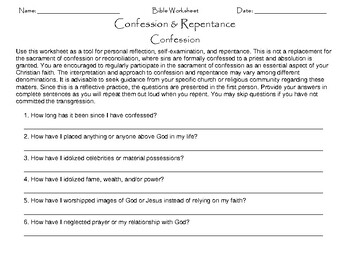

Confession & Repentance Worksheet For Healing & Transformation

Confessions of a Shopaholic: Quote Analysis Worksheets

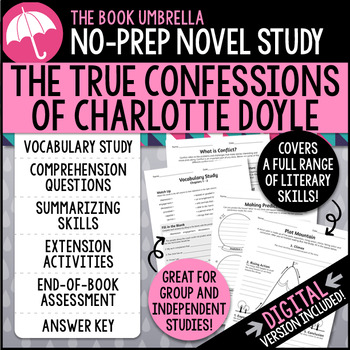

“The true confessions of Charlotte Doyle” by Avi UDL Worksheet Bundle

“The true confessions of Charlotte Doyle” Story Worksheet Packet (33 Total)

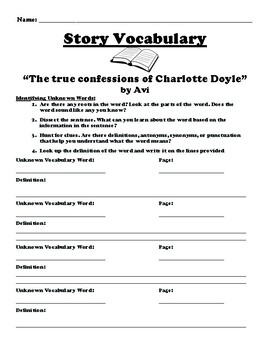

“The true confessions of Charlotte Doyle” Unknown Vocabulary Worksheet

Primary Document Worksheet : Nat Turner, Confessions of Nat Turner (1831)

The Negative Confession "History Brochure" UDL Worksheet & WebQuest

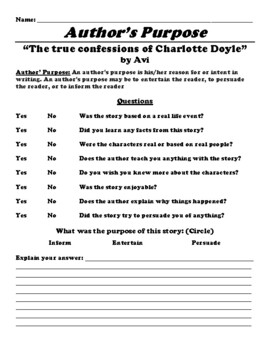

“The true confessions of Charlotte Doyle” Author's Purpose Worksheet

“The true confessions of Charlotte Doyle” THEME WORKSHEET MAIN & MINOR (PDF)

“The true confessions of Charlotte Doyle” by Avi TIMELINE WORKSHEET

“The true confessions of Charlotte Doyle” Event Worksheet (UDL)

“The true confessions of Charlotte Doyle” UDL Choice Board Worksheet

Sacrament Reconciliation Worksheets

Nat Turner's Rebellion Primary Source Worksheet & Reading on Slavery

- Google Apps™

The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle Novel Study { Print & Digital }

Sacrament of First Reconciliation Prodigal Son Lost Sheep Parables Confession

Depth and Complexity Novel Study for The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle

Reconciliation Confession Activities | Distance Learning

Multiplication Number Puzzles | Multiplication Practice Worksheets

FRANKENSTEIN Word Search Puzzle Worksheet Activity

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

How to improve your problem solving skills and build effective problem solving strategies

Design your next session with SessionLab

Join the 150,000+ facilitators using SessionLab.

Recommended Articles

A step-by-step guide to planning a workshop, how to create an unforgettable training session in 8 simple steps, 47 useful online tools for workshop planning and meeting facilitation.

Effective problem solving is all about using the right process and following a plan tailored to the issue at hand. Recognizing your team or organization has an issue isn’t enough to come up with effective problem solving strategies.

To truly understand a problem and develop appropriate solutions, you will want to follow a solid process, follow the necessary problem solving steps, and bring all of your problem solving skills to the table.

We’ll first guide you through the seven step problem solving process you and your team can use to effectively solve complex business challenges. We’ll also look at what problem solving strategies you can employ with your team when looking for a way to approach the process. We’ll then discuss the problem solving skills you need to be more effective at solving problems, complete with an activity from the SessionLab library you can use to develop that skill in your team.

Let’s get to it!

What is a problem solving process?

- What are the problem solving steps I need to follow?

Problem solving strategies

What skills do i need to be an effective problem solver, how can i improve my problem solving skills.

Solving problems is like baking a cake. You can go straight into the kitchen without a recipe or the right ingredients and do your best, but the end result is unlikely to be very tasty!

Using a process to bake a cake allows you to use the best ingredients without waste, collect the right tools, account for allergies, decide whether it is a birthday or wedding cake, and then bake efficiently and on time. The result is a better cake that is fit for purpose, tastes better and has created less mess in the kitchen. Also, it should have chocolate sprinkles. Having a step by step process to solve organizational problems allows you to go through each stage methodically and ensure you are trying to solve the right problems and select the most appropriate, effective solutions.

What are the problem solving steps I need to follow?

All problem solving processes go through a number of steps in order to move from identifying a problem to resolving it.

Depending on your problem solving model and who you ask, there can be anything between four and nine problem solving steps you should follow in order to find the right solution. Whatever framework you and your group use, there are some key items that should be addressed in order to have an effective process.

We’ve looked at problem solving processes from sources such as the American Society for Quality and their four step approach , and Mediate ‘s six step process. By reflecting on those and our own problem solving processes, we’ve come up with a sequence of seven problem solving steps we feel best covers everything you need in order to effectively solve problems.

1. Problem identification

The first stage of any problem solving process is to identify the problem or problems you might want to solve. Effective problem solving strategies always begin by allowing a group scope to articulate what they believe the problem to be and then coming to some consensus over which problem they approach first. Problem solving activities used at this stage often have a focus on creating frank, open discussion so that potential problems can be brought to the surface.

2. Problem analysis

Though this step is not a million miles from problem identification, problem analysis deserves to be considered separately. It can often be an overlooked part of the process and is instrumental when it comes to developing effective solutions.

The process of problem analysis means ensuring that the problem you are seeking to solve is the right problem . As part of this stage, you may look deeper and try to find the root cause of a specific problem at a team or organizational level.

Remember that problem solving strategies should not only be focused on putting out fires in the short term but developing long term solutions that deal with the root cause of organizational challenges.

Whatever your approach, analyzing a problem is crucial in being able to select an appropriate solution and the problem solving skills deployed in this stage are beneficial for the rest of the process and ensuring the solutions you create are fit for purpose.

3. Solution generation

Once your group has nailed down the particulars of the problem you wish to solve, you want to encourage a free flow of ideas connecting to solving that problem. This can take the form of problem solving games that encourage creative thinking or problem solving activities designed to produce working prototypes of possible solutions.

The key to ensuring the success of this stage of the problem solving process is to encourage quick, creative thinking and create an open space where all ideas are considered. The best solutions can come from unlikely places and by using problem solving techniques that celebrate invention, you might come up with solution gold.

4. Solution development

No solution is likely to be perfect right out of the gate. It’s important to discuss and develop the solutions your group has come up with over the course of following the previous problem solving steps in order to arrive at the best possible solution. Problem solving games used in this stage involve lots of critical thinking, measuring potential effort and impact, and looking at possible solutions analytically.

During this stage, you will often ask your team to iterate and improve upon your frontrunning solutions and develop them further. Remember that problem solving strategies always benefit from a multitude of voices and opinions, and not to let ego get involved when it comes to choosing which solutions to develop and take further.

Finding the best solution is the goal of all problem solving workshops and here is the place to ensure that your solution is well thought out, sufficiently robust and fit for purpose.

5. Decision making

Nearly there! Once your group has reached consensus and selected a solution that applies to the problem at hand you have some decisions to make. You will want to work on allocating ownership of the project, figure out who will do what, how the success of the solution will be measured and decide the next course of action.

The decision making stage is a part of the problem solving process that can get missed or taken as for granted. Fail to properly allocate roles and plan out how a solution will actually be implemented and it less likely to be successful in solving the problem.

Have clear accountabilities, actions, timeframes, and follow-ups. Make these decisions and set clear next-steps in the problem solving workshop so that everyone is aligned and you can move forward effectively as a group.

Ensuring that you plan for the roll-out of a solution is one of the most important problem solving steps. Without adequate planning or oversight, it can prove impossible to measure success or iterate further if the problem was not solved.

6. Solution implementation

This is what we were waiting for! All problem solving strategies have the end goal of implementing a solution and solving a problem in mind.

Remember that in order for any solution to be successful, you need to help your group through all of the previous problem solving steps thoughtfully. Only then can you ensure that you are solving the right problem but also that you have developed the correct solution and can then successfully implement and measure the impact of that solution.

Project management and communication skills are key here – your solution may need to adjust when out in the wild or you might discover new challenges along the way.

7. Solution evaluation

So you and your team developed a great solution to a problem and have a gut feeling its been solved. Work done, right? Wrong. All problem solving strategies benefit from evaluation, consideration, and feedback. You might find that the solution does not work for everyone, might create new problems, or is potentially so successful that you will want to roll it out to larger teams or as part of other initiatives.

None of that is possible without taking the time to evaluate the success of the solution you developed in your problem solving model and adjust if necessary.

Remember that the problem solving process is often iterative and it can be common to not solve complex issues on the first try. Even when this is the case, you and your team will have generated learning that will be important for future problem solving workshops or in other parts of the organization.

It’s worth underlining how important record keeping is throughout the problem solving process. If a solution didn’t work, you need to have the data and records to see why that was the case. If you go back to the drawing board, notes from the previous workshop can help save time. Data and insight is invaluable at every stage of the problem solving process and this one is no different.

Problem solving workshops made easy

Problem solving strategies are methods of approaching and facilitating the process of problem-solving with a set of techniques , actions, and processes. Different strategies are more effective if you are trying to solve broad problems such as achieving higher growth versus more focused problems like, how do we improve our customer onboarding process?

Broadly, the problem solving steps outlined above should be included in any problem solving strategy though choosing where to focus your time and what approaches should be taken is where they begin to differ. You might find that some strategies ask for the problem identification to be done prior to the session or that everything happens in the course of a one day workshop.

The key similarity is that all good problem solving strategies are structured and designed. Four hours of open discussion is never going to be as productive as a four-hour workshop designed to lead a group through a problem solving process.

Good problem solving strategies are tailored to the team, organization and problem you will be attempting to solve. Here are some example problem solving strategies you can learn from or use to get started.

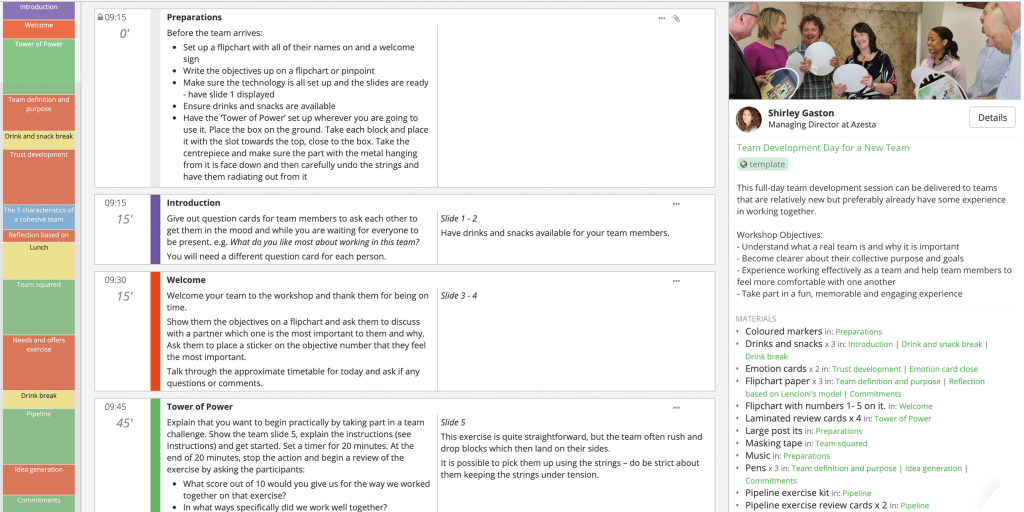

Use a workshop to lead a team through a group process

Often, the first step to solving problems or organizational challenges is bringing a group together effectively. Most teams have the tools, knowledge, and expertise necessary to solve their challenges – they just need some guidance in how to use leverage those skills and a structure and format that allows people to focus their energies.

Facilitated workshops are one of the most effective ways of solving problems of any scale. By designing and planning your workshop carefully, you can tailor the approach and scope to best fit the needs of your team and organization.

Problem solving workshop

- Creating a bespoke, tailored process

- Tackling problems of any size

- Building in-house workshop ability and encouraging their use

Workshops are an effective strategy for solving problems. By using tried and test facilitation techniques and methods, you can design and deliver a workshop that is perfectly suited to the unique variables of your organization. You may only have the capacity for a half-day workshop and so need a problem solving process to match.

By using our session planner tool and importing methods from our library of 700+ facilitation techniques, you can create the right problem solving workshop for your team. It might be that you want to encourage creative thinking or look at things from a new angle to unblock your groups approach to problem solving. By tailoring your workshop design to the purpose, you can help ensure great results.

One of the main benefits of a workshop is the structured approach to problem solving. Not only does this mean that the workshop itself will be successful, but many of the methods and techniques will help your team improve their working processes outside of the workshop.

We believe that workshops are one of the best tools you can use to improve the way your team works together. Start with a problem solving workshop and then see what team building, culture or design workshops can do for your organization!

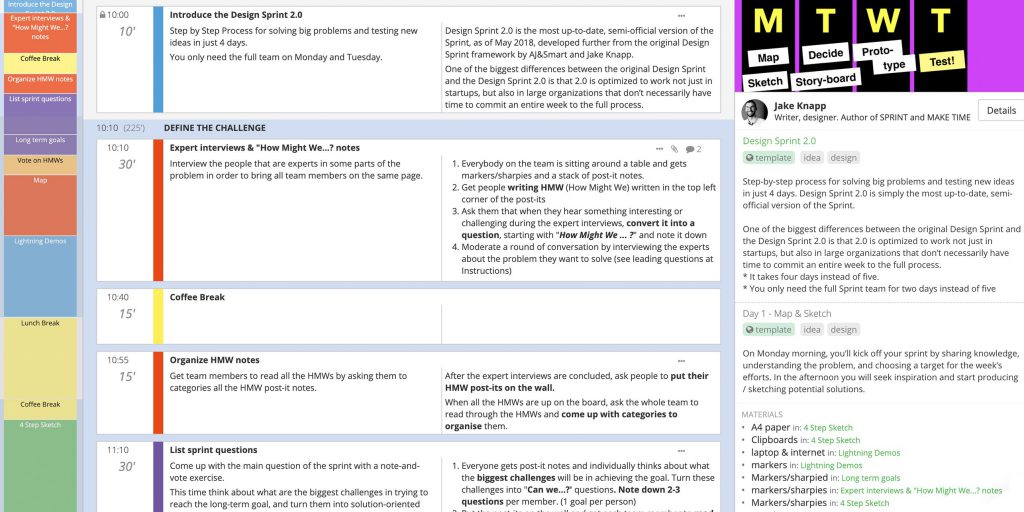

Run a design sprint

Great for:

- aligning large, multi-discipline teams

- quickly designing and testing solutions

- tackling large, complex organizational challenges and breaking them down into smaller tasks

By using design thinking principles and methods, a design sprint is a great way of identifying, prioritizing and prototyping solutions to long term challenges that can help solve major organizational problems with quick action and measurable results.

Some familiarity with design thinking is useful, though not integral, and this strategy can really help a team align if there is some discussion around which problems should be approached first.

The stage-based structure of the design sprint is also very useful for teams new to design thinking. The inspiration phase, where you look to competitors that have solved your problem, and the rapid prototyping and testing phases are great for introducing new concepts that will benefit a team in all their future work.

It can be common for teams to look inward for solutions and so looking to the market for solutions you can iterate on can be very productive. Instilling an agile prototyping and testing mindset can also be great when helping teams move forwards – generating and testing solutions quickly can help save time in the long run and is also pretty exciting!

Break problems down into smaller issues

Organizational challenges and problems are often complicated and large scale in nature. Sometimes, trying to resolve such an issue in one swoop is simply unachievable or overwhelming. Try breaking down such problems into smaller issues that you can work on step by step. You may not be able to solve the problem of churning customers off the bat, but you can work with your team to identify smaller effort but high impact elements and work on those first.

This problem solving strategy can help a team generate momentum, prioritize and get some easy wins. It’s also a great strategy to employ with teams who are just beginning to learn how to approach the problem solving process. If you want some insight into a way to employ this strategy, we recommend looking at our design sprint template below!

Use guiding frameworks or try new methodologies

Some problems are best solved by introducing a major shift in perspective or by using new methodologies that encourage your team to think differently.

Props and tools such as Methodkit , which uses a card-based toolkit for facilitation, or Lego Serious Play can be great ways to engage your team and find an inclusive, democratic problem solving strategy. Remember that play and creativity are great tools for achieving change and whatever the challenge, engaging your participants can be very effective where other strategies may have failed.

LEGO Serious Play

- Improving core problem solving skills

- Thinking outside of the box

- Encouraging creative solutions

LEGO Serious Play is a problem solving methodology designed to get participants thinking differently by using 3D models and kinesthetic learning styles. By physically building LEGO models based on questions and exercises, participants are encouraged to think outside of the box and create their own responses.

Collaborate LEGO Serious Play exercises are also used to encourage communication and build problem solving skills in a group. By using this problem solving process, you can often help different kinds of learners and personality types contribute and unblock organizational problems with creative thinking.

Problem solving strategies like LEGO Serious Play are super effective at helping a team solve more skills-based problems such as communication between teams or a lack of creative thinking. Some problems are not suited to LEGO Serious Play and require a different problem solving strategy.

Card Decks and Method Kits

- New facilitators or non-facilitators

- Approaching difficult subjects with a simple, creative framework

- Engaging those with varied learning styles

Card decks and method kids are great tools for those new to facilitation or for whom facilitation is not the primary role. Card decks such as the emotional culture deck can be used for complete workshops and in many cases, can be used right out of the box. Methodkit has a variety of kits designed for scenarios ranging from personal development through to personas and global challenges so you can find the right deck for your particular needs.

Having an easy to use framework that encourages creativity or a new approach can take some of the friction or planning difficulties out of the workshop process and energize a team in any setting. Simplicity is the key with these methods. By ensuring everyone on your team can get involved and engage with the process as quickly as possible can really contribute to the success of your problem solving strategy.

Source external advice

Looking to peers, experts and external facilitators can be a great way of approaching the problem solving process. Your team may not have the necessary expertise, insights of experience to tackle some issues, or you might simply benefit from a fresh perspective. Some problems may require bringing together an entire team, and coaching managers or team members individually might be the right approach. Remember that not all problems are best resolved in the same manner.

If you’re a solo entrepreneur, peer groups, coaches and mentors can also be invaluable at not only solving specific business problems, but in providing a support network for resolving future challenges. One great approach is to join a Mastermind Group and link up with like-minded individuals and all grow together. Remember that however you approach the sourcing of external advice, do so thoughtfully, respectfully and honestly. Reciprocate where you can and prepare to be surprised by just how kind and helpful your peers can be!

Mastermind Group

- Solo entrepreneurs or small teams with low capacity

- Peer learning and gaining outside expertise

- Getting multiple external points of view quickly

Problem solving in large organizations with lots of skilled team members is one thing, but how about if you work for yourself or in a very small team without the capacity to get the most from a design sprint or LEGO Serious Play session?

A mastermind group – sometimes known as a peer advisory board – is where a group of people come together to support one another in their own goals, challenges, and businesses. Each participant comes to the group with their own purpose and the other members of the group will help them create solutions, brainstorm ideas, and support one another.

Mastermind groups are very effective in creating an energized, supportive atmosphere that can deliver meaningful results. Learning from peers from outside of your organization or industry can really help unlock new ways of thinking and drive growth. Access to the experience and skills of your peers can be invaluable in helping fill the gaps in your own ability, particularly in young companies.

A mastermind group is a great solution for solo entrepreneurs, small teams, or for organizations that feel that external expertise or fresh perspectives will be beneficial for them. It is worth noting that Mastermind groups are often only as good as the participants and what they can bring to the group. Participants need to be committed, engaged and understand how to work in this context.

Coaching and mentoring

- Focused learning and development

- Filling skills gaps

- Working on a range of challenges over time

Receiving advice from a business coach or building a mentor/mentee relationship can be an effective way of resolving certain challenges. The one-to-one format of most coaching and mentor relationships can really help solve the challenges those individuals are having and benefit the organization as a result.

A great mentor can be invaluable when it comes to spotting potential problems before they arise and coming to understand a mentee very well has a host of other business benefits. You might run an internal mentorship program to help develop your team’s problem solving skills and strategies or as part of a large learning and development program. External coaches can also be an important part of your problem solving strategy, filling skills gaps for your management team or helping with specific business issues.

Now we’ve explored the problem solving process and the steps you will want to go through in order to have an effective session, let’s look at the skills you and your team need to be more effective problem solvers.

Problem solving skills are highly sought after, whatever industry or team you work in. Organizations are keen to employ people who are able to approach problems thoughtfully and find strong, realistic solutions. Whether you are a facilitator , a team leader or a developer, being an effective problem solver is a skill you’ll want to develop.

Problem solving skills form a whole suite of techniques and approaches that an individual uses to not only identify problems but to discuss them productively before then developing appropriate solutions.

Here are some of the most important problem solving skills everyone from executives to junior staff members should learn. We’ve also included an activity or exercise from the SessionLab library that can help you and your team develop that skill.

If you’re running a workshop or training session to try and improve problem solving skills in your team, try using these methods to supercharge your process!

Active listening

Active listening is one of the most important skills anyone who works with people can possess. In short, active listening is a technique used to not only better understand what is being said by an individual, but also to be more aware of the underlying message the speaker is trying to convey. When it comes to problem solving, active listening is integral for understanding the position of every participant and to clarify the challenges, ideas and solutions they bring to the table.

Some active listening skills include:

- Paying complete attention to the speaker.

- Removing distractions.

- Avoid interruption.

- Taking the time to fully understand before preparing a rebuttal.

- Responding respectfully and appropriately.

- Demonstrate attentiveness and positivity with an open posture, making eye contact with the speaker, smiling and nodding if appropriate. Show that you are listening and encourage them to continue.

- Be aware of and respectful of feelings. Judge the situation and respond appropriately. You can disagree without being disrespectful.

- Observe body language.

- Paraphrase what was said in your own words, either mentally or verbally.

- Remain neutral.

- Reflect and take a moment before responding.

- Ask deeper questions based on what is said and clarify points where necessary.

Active Listening #hyperisland #skills #active listening #remote-friendly This activity supports participants to reflect on a question and generate their own solutions using simple principles of active listening and peer coaching. It’s an excellent introduction to active listening but can also be used with groups that are already familiar with it. Participants work in groups of three and take turns being: “the subject”, the listener, and the observer.

Analytical skills

All problem solving models require strong analytical skills, particularly during the beginning of the process and when it comes to analyzing how solutions have performed.

Analytical skills are primarily focused on performing an effective analysis by collecting, studying and parsing data related to a problem or opportunity.

It often involves spotting patterns, being able to see things from different perspectives and using observable facts and data to make suggestions or produce insight.

Analytical skills are also important at every stage of the problem solving process and by having these skills, you can ensure that any ideas or solutions you create or backed up analytically and have been sufficiently thought out.

Nine Whys #innovation #issue analysis #liberating structures With breathtaking simplicity, you can rapidly clarify for individuals and a group what is essentially important in their work. You can quickly reveal when a compelling purpose is missing in a gathering and avoid moving forward without clarity. When a group discovers an unambiguous shared purpose, more freedom and more responsibility are unleashed. You have laid the foundation for spreading and scaling innovations with fidelity.

Collaboration

Trying to solve problems on your own is difficult. Being able to collaborate effectively, with a free exchange of ideas, to delegate and be a productive member of a team is hugely important to all problem solving strategies.

Remember that whatever your role, collaboration is integral, and in a problem solving process, you are all working together to find the best solution for everyone.

Marshmallow challenge with debriefing #teamwork #team #leadership #collaboration In eighteen minutes, teams must build the tallest free-standing structure out of 20 sticks of spaghetti, one yard of tape, one yard of string, and one marshmallow. The marshmallow needs to be on top. The Marshmallow Challenge was developed by Tom Wujec, who has done the activity with hundreds of groups around the world. Visit the Marshmallow Challenge website for more information. This version has an extra debriefing question added with sample questions focusing on roles within the team.

Communication

Being an effective communicator means being empathetic, clear and succinct, asking the right questions, and demonstrating active listening skills throughout any discussion or meeting.

In a problem solving setting, you need to communicate well in order to progress through each stage of the process effectively. As a team leader, it may also fall to you to facilitate communication between parties who may not see eye to eye. Effective communication also means helping others to express themselves and be heard in a group.

Bus Trip #feedback #communication #appreciation #closing #thiagi #team This is one of my favourite feedback games. I use Bus Trip at the end of a training session or a meeting, and I use it all the time. The game creates a massive amount of energy with lots of smiles, laughs, and sometimes even a teardrop or two.

Creative problem solving skills can be some of the best tools in your arsenal. Thinking creatively, being able to generate lots of ideas and come up with out of the box solutions is useful at every step of the process.

The kinds of problems you will likely discuss in a problem solving workshop are often difficult to solve, and by approaching things in a fresh, creative manner, you can often create more innovative solutions.

Having practical creative skills is also a boon when it comes to problem solving. If you can help create quality design sketches and prototypes in record time, it can help bring a team to alignment more quickly or provide a base for further iteration.

The paper clip method #sharing #creativity #warm up #idea generation #brainstorming The power of brainstorming. A training for project leaders, creativity training, and to catalyse getting new solutions.

Critical thinking

Critical thinking is one of the fundamental problem solving skills you’ll want to develop when working on developing solutions. Critical thinking is the ability to analyze, rationalize and evaluate while being aware of personal bias, outlying factors and remaining open-minded.

Defining and analyzing problems without deploying critical thinking skills can mean you and your team go down the wrong path. Developing solutions to complex issues requires critical thinking too – ensuring your team considers all possibilities and rationally evaluating them.

Agreement-Certainty Matrix #issue analysis #liberating structures #problem solving You can help individuals or groups avoid the frequent mistake of trying to solve a problem with methods that are not adapted to the nature of their challenge. The combination of two questions makes it possible to easily sort challenges into four categories: simple, complicated, complex , and chaotic . A problem is simple when it can be solved reliably with practices that are easy to duplicate. It is complicated when experts are required to devise a sophisticated solution that will yield the desired results predictably. A problem is complex when there are several valid ways to proceed but outcomes are not predictable in detail. Chaotic is when the context is too turbulent to identify a path forward. A loose analogy may be used to describe these differences: simple is like following a recipe, complicated like sending a rocket to the moon, complex like raising a child, and chaotic is like the game “Pin the Tail on the Donkey.” The Liberating Structures Matching Matrix in Chapter 5 can be used as the first step to clarify the nature of a challenge and avoid the mismatches between problems and solutions that are frequently at the root of chronic, recurring problems.

Data analysis

Though it shares lots of space with general analytical skills, data analysis skills are something you want to cultivate in their own right in order to be an effective problem solver.

Being good at data analysis doesn’t just mean being able to find insights from data, but also selecting the appropriate data for a given issue, interpreting it effectively and knowing how to model and present that data. Depending on the problem at hand, it might also include a working knowledge of specific data analysis tools and procedures.

Having a solid grasp of data analysis techniques is useful if you’re leading a problem solving workshop but if you’re not an expert, don’t worry. Bring people into the group who has this skill set and help your team be more effective as a result.

Decision making

All problems need a solution and all solutions require that someone make the decision to implement them. Without strong decision making skills, teams can become bogged down in discussion and less effective as a result.

Making decisions is a key part of the problem solving process. It’s important to remember that decision making is not restricted to the leadership team. Every staff member makes decisions every day and developing these skills ensures that your team is able to solve problems at any scale. Remember that making decisions does not mean leaping to the first solution but weighing up the options and coming to an informed, well thought out solution to any given problem that works for the whole team.

Lightning Decision Jam (LDJ) #action #decision making #problem solving #issue analysis #innovation #design #remote-friendly The problem with anything that requires creative thinking is that it’s easy to get lost—lose focus and fall into the trap of having useless, open-ended, unstructured discussions. Here’s the most effective solution I’ve found: Replace all open, unstructured discussion with a clear process. What to use this exercise for: Anything which requires a group of people to make decisions, solve problems or discuss challenges. It’s always good to frame an LDJ session with a broad topic, here are some examples: The conversion flow of our checkout Our internal design process How we organise events Keeping up with our competition Improving sales flow

Dependability

Most complex organizational problems require multiple people to be involved in delivering the solution. Ensuring that the team and organization can depend on you to take the necessary actions and communicate where necessary is key to ensuring problems are solved effectively.

Being dependable also means working to deadlines and to brief. It is often a matter of creating trust in a team so that everyone can depend on one another to complete the agreed actions in the agreed time frame so that the team can move forward together. Being undependable can create problems of friction and can limit the effectiveness of your solutions so be sure to bear this in mind throughout a project.

Team Purpose & Culture #team #hyperisland #culture #remote-friendly This is an essential process designed to help teams define their purpose (why they exist) and their culture (how they work together to achieve that purpose). Defining these two things will help any team to be more focused and aligned. With support of tangible examples from other companies, the team members work as individuals and a group to codify the way they work together. The goal is a visual manifestation of both the purpose and culture that can be put up in the team’s work space.

Emotional intelligence

Emotional intelligence is an important skill for any successful team member, whether communicating internally or with clients or users. In the problem solving process, emotional intelligence means being attuned to how people are feeling and thinking, communicating effectively and being self-aware of what you bring to a room.

There are often differences of opinion when working through problem solving processes, and it can be easy to let things become impassioned or combative. Developing your emotional intelligence means being empathetic to your colleagues and managing your own emotions throughout the problem and solution process. Be kind, be thoughtful and put your points across care and attention.

Being emotionally intelligent is a skill for life and by deploying it at work, you can not only work efficiently but empathetically. Check out the emotional culture workshop template for more!

Facilitation

As we’ve clarified in our facilitation skills post, facilitation is the art of leading people through processes towards agreed-upon objectives in a manner that encourages participation, ownership, and creativity by all those involved. While facilitation is a set of interrelated skills in itself, the broad definition of facilitation can be invaluable when it comes to problem solving. Leading a team through a problem solving process is made more effective if you improve and utilize facilitation skills – whether you’re a manager, team leader or external stakeholder.

The Six Thinking Hats #creative thinking #meeting facilitation #problem solving #issue resolution #idea generation #conflict resolution The Six Thinking Hats are used by individuals and groups to separate out conflicting styles of thinking. They enable and encourage a group of people to think constructively together in exploring and implementing change, rather than using argument to fight over who is right and who is wrong.

Flexibility

Being flexible is a vital skill when it comes to problem solving. This does not mean immediately bowing to pressure or changing your opinion quickly: instead, being flexible is all about seeing things from new perspectives, receiving new information and factoring it into your thought process.

Flexibility is also important when it comes to rolling out solutions. It might be that other organizational projects have greater priority or require the same resources as your chosen solution. Being flexible means understanding needs and challenges across the team and being open to shifting or arranging your own schedule as necessary. Again, this does not mean immediately making way for other projects. It’s about articulating your own needs, understanding the needs of others and being able to come to a meaningful compromise.

The Creativity Dice #creativity #problem solving #thiagi #issue analysis Too much linear thinking is hazardous to creative problem solving. To be creative, you should approach the problem (or the opportunity) from different points of view. You should leave a thought hanging in mid-air and move to another. This skipping around prevents premature closure and lets your brain incubate one line of thought while you consciously pursue another.

Working in any group can lead to unconscious elements of groupthink or situations in which you may not wish to be entirely honest. Disagreeing with the opinions of the executive team or wishing to save the feelings of a coworker can be tricky to navigate, but being honest is absolutely vital when to comes to developing effective solutions and ensuring your voice is heard.

Remember that being honest does not mean being brutally candid. You can deliver your honest feedback and opinions thoughtfully and without creating friction by using other skills such as emotional intelligence.

Explore your Values #hyperisland #skills #values #remote-friendly Your Values is an exercise for participants to explore what their most important values are. It’s done in an intuitive and rapid way to encourage participants to follow their intuitive feeling rather than over-thinking and finding the “correct” values. It is a good exercise to use to initiate reflection and dialogue around personal values.

Initiative

The problem solving process is multi-faceted and requires different approaches at certain points of the process. Taking initiative to bring problems to the attention of the team, collect data or lead the solution creating process is always valuable. You might even roadtest your own small scale solutions or brainstorm before a session. Taking initiative is particularly effective if you have good deal of knowledge in that area or have ownership of a particular project and want to get things kickstarted.

That said, be sure to remember to honor the process and work in service of the team. If you are asked to own one part of the problem solving process and you don’t complete that task because your initiative leads you to work on something else, that’s not an effective method of solving business challenges.

15% Solutions #action #liberating structures #remote-friendly You can reveal the actions, however small, that everyone can do immediately. At a minimum, these will create momentum, and that may make a BIG difference. 15% Solutions show that there is no reason to wait around, feel powerless, or fearful. They help people pick it up a level. They get individuals and the group to focus on what is within their discretion instead of what they cannot change. With a very simple question, you can flip the conversation to what can be done and find solutions to big problems that are often distributed widely in places not known in advance. Shifting a few grains of sand may trigger a landslide and change the whole landscape.

Impartiality

A particularly useful problem solving skill for product owners or managers is the ability to remain impartial throughout much of the process. In practice, this means treating all points of view and ideas brought forward in a meeting equally and ensuring that your own areas of interest or ownership are not favored over others.

There may be a stage in the process where a decision maker has to weigh the cost and ROI of possible solutions against the company roadmap though even then, ensuring that the decision made is based on merit and not personal opinion.

Empathy map #frame insights #create #design #issue analysis An empathy map is a tool to help a design team to empathize with the people they are designing for. You can make an empathy map for a group of people or for a persona. To be used after doing personas when more insights are needed.

Being a good leader means getting a team aligned, energized and focused around a common goal. In the problem solving process, strong leadership helps ensure that the process is efficient, that any conflicts are resolved and that a team is managed in the direction of success.

It’s common for managers or executives to assume this role in a problem solving workshop, though it’s important that the leader maintains impartiality and does not bulldoze the group in a particular direction. Remember that good leadership means working in service of the purpose and team and ensuring the workshop is a safe space for employees of any level to contribute. Take a look at our leadership games and activities post for more exercises and methods to help improve leadership in your organization.

Leadership Pizza #leadership #team #remote-friendly This leadership development activity offers a self-assessment framework for people to first identify what skills, attributes and attitudes they find important for effective leadership, and then assess their own development and initiate goal setting.

In the context of problem solving, mediation is important in keeping a team engaged, happy and free of conflict. When leading or facilitating a problem solving workshop, you are likely to run into differences of opinion. Depending on the nature of the problem, certain issues may be brought up that are emotive in nature.

Being an effective mediator means helping those people on either side of such a divide are heard, listen to one another and encouraged to find common ground and a resolution. Mediating skills are useful for leaders and managers in many situations and the problem solving process is no different.

Conflict Responses #hyperisland #team #issue resolution A workshop for a team to reflect on past conflicts, and use them to generate guidelines for effective conflict handling. The workshop uses the Thomas-Killman model of conflict responses to frame a reflective discussion. Use it to open up a discussion around conflict with a team.

Planning

Solving organizational problems is much more effective when following a process or problem solving model. Planning skills are vital in order to structure, deliver and follow-through on a problem solving workshop and ensure your solutions are intelligently deployed.

Planning skills include the ability to organize tasks and a team, plan and design the process and take into account any potential challenges. Taking the time to plan carefully can save time and frustration later in the process and is valuable for ensuring a team is positioned for success.

3 Action Steps #hyperisland #action #remote-friendly This is a small-scale strategic planning session that helps groups and individuals to take action toward a desired change. It is often used at the end of a workshop or programme. The group discusses and agrees on a vision, then creates some action steps that will lead them towards that vision. The scope of the challenge is also defined, through discussion of the helpful and harmful factors influencing the group.

Prioritization

As organisations grow, the scale and variation of problems they face multiplies. Your team or is likely to face numerous challenges in different areas and so having the skills to analyze and prioritize becomes very important, particularly for those in leadership roles.

A thorough problem solving process is likely to deliver multiple solutions and you may have several different problems you wish to solve simultaneously. Prioritization is the ability to measure the importance, value, and effectiveness of those possible solutions and choose which to enact and in what order. The process of prioritization is integral in ensuring the biggest challenges are addressed with the most impactful solutions.

Impact and Effort Matrix #gamestorming #decision making #action #remote-friendly In this decision-making exercise, possible actions are mapped based on two factors: effort required to implement and potential impact. Categorizing ideas along these lines is a useful technique in decision making, as it obliges contributors to balance and evaluate suggested actions before committing to them.

Project management

Some problem solving skills are utilized in a workshop or ideation phases, while others come in useful when it comes to decision making. Overseeing an entire problem solving process and ensuring its success requires strong project management skills.

While project management incorporates many of the other skills listed here, it is important to note the distinction of considering all of the factors of a project and managing them successfully. Being able to negotiate with stakeholders, manage tasks, time and people, consider costs and ROI, and tie everything together is massively helpful when going through the problem solving process.

Record keeping

Working out meaningful solutions to organizational challenges is only one part of the process. Thoughtfully documenting and keeping records of each problem solving step for future consultation is important in ensuring efficiency and meaningful change.

For example, some problems may be lower priority than others but can be revisited in the future. If the team has ideated on solutions and found some are not up to the task, record those so you can rule them out and avoiding repeating work. Keeping records of the process also helps you improve and refine your problem solving model next time around!

Personal Kanban #gamestorming #action #agile #project planning Personal Kanban is a tool for organizing your work to be more efficient and productive. It is based on agile methods and principles.

Research skills

Conducting research to support both the identification of problems and the development of appropriate solutions is important for an effective process. Knowing where to go to collect research, how to conduct research efficiently, and identifying pieces of research are relevant are all things a good researcher can do well.

In larger groups, not everyone has to demonstrate this ability in order for a problem solving workshop to be effective. That said, having people with research skills involved in the process, particularly if they have existing area knowledge, can help ensure the solutions that are developed with data that supports their intention. Remember that being able to deliver the results of research efficiently and in a way the team can easily understand is also important. The best data in the world is only as effective as how it is delivered and interpreted.

Customer experience map #ideation #concepts #research #design #issue analysis #remote-friendly Customer experience mapping is a method of documenting and visualizing the experience a customer has as they use the product or service. It also maps out their responses to their experiences. To be used when there is a solution (even in a conceptual stage) that can be analyzed.

Risk management

Managing risk is an often overlooked part of the problem solving process. Solutions are often developed with the intention of reducing exposure to risk or solving issues that create risk but sometimes, great solutions are more experimental in nature and as such, deploying them needs to be carefully considered.

Managing risk means acknowledging that there may be risks associated with more out of the box solutions or trying new things, but that this must be measured against the possible benefits and other organizational factors.

Be informed, get the right data and stakeholders in the room and you can appropriately factor risk into your decision making process.

Decisions, Decisions… #communication #decision making #thiagi #action #issue analysis When it comes to decision-making, why are some of us more prone to take risks while others are risk-averse? One explanation might be the way the decision and options were presented. This exercise, based on Kahneman and Tversky’s classic study , illustrates how the framing effect influences our judgement and our ability to make decisions . The participants are divided into two groups. Both groups are presented with the same problem and two alternative programs for solving them. The two programs both have the same consequences but are presented differently. The debriefing discussion examines how the framing of the program impacted the participant’s decision.

Team-building

No single person is as good at problem solving as a team. Building an effective team and helping them come together around a common purpose is one of the most important problem solving skills, doubly so for leaders. By bringing a team together and helping them work efficiently, you pave the way for team ownership of a problem and the development of effective solutions.

In a problem solving workshop, it can be tempting to jump right into the deep end, though taking the time to break the ice, energize the team and align them with a game or exercise will pay off over the course of the day.

Remember that you will likely go through the problem solving process multiple times over an organization’s lifespan and building a strong team culture will make future problem solving more effective. It’s also great to work with people you know, trust and have fun with. Working on team building in and out of the problem solving process is a hallmark of successful teams that can work together to solve business problems.

9 Dimensions Team Building Activity #ice breaker #teambuilding #team #remote-friendly 9 Dimensions is a powerful activity designed to build relationships and trust among team members. There are 2 variations of this icebreaker. The first version is for teams who want to get to know each other better. The second version is for teams who want to explore how they are working together as a team.

Time management

The problem solving process is designed to lead a team from identifying a problem through to delivering a solution and evaluating its effectiveness. Without effective time management skills or timeboxing of tasks, it can be easy for a team to get bogged down or be inefficient.

By using a problem solving model and carefully designing your workshop, you can allocate time efficiently and trust that the process will deliver the results you need in a good timeframe.

Time management also comes into play when it comes to rolling out solutions, particularly those that are experimental in nature. Having a clear timeframe for implementing and evaluating solutions is vital for ensuring their success and being able to pivot if necessary.

Improving your skills at problem solving is often a career-long pursuit though there are methods you can use to make the learning process more efficient and to supercharge your problem solving skillset.

Remember that the skills you need to be a great problem solver have a large overlap with those skills you need to be effective in any role. Investing time and effort to develop your active listening or critical thinking skills is valuable in any context. Here are 7 ways to improve your problem solving skills.

Share best practices

Remember that your team is an excellent source of skills, wisdom, and techniques and that you should all take advantage of one another where possible. Best practices that one team has for solving problems, conducting research or making decisions should be shared across the organization. If you have in-house staff that have done active listening training or are data analysis pros, have them lead a training session.

Your team is one of your best resources. Create space and internal processes for the sharing of skills so that you can all grow together.

Ask for help and attend training

Once you’ve figured out you have a skills gap, the next step is to take action to fill that skills gap. That might be by asking your superior for training or coaching, or liaising with team members with that skill set. You might even attend specialized training for certain skills – active listening or critical thinking, for example, are business-critical skills that are regularly offered as part of a training scheme.

Whatever method you choose, remember that taking action of some description is necessary for growth. Whether that means practicing, getting help, attending training or doing some background reading, taking active steps to improve your skills is the way to go.

Learn a process