Research Aims, Objectives & Questions

The “Golden Thread” Explained Simply (+ Examples)

By: David Phair (PhD) and Alexandra Shaeffer (PhD) | June 2022

The research aims , objectives and research questions (collectively called the “golden thread”) are arguably the most important thing you need to get right when you’re crafting a research proposal , dissertation or thesis . We receive questions almost every day about this “holy trinity” of research and there’s certainly a lot of confusion out there, so we’ve crafted this post to help you navigate your way through the fog.

Overview: The Golden Thread

- What is the golden thread

- What are research aims ( examples )

- What are research objectives ( examples )

- What are research questions ( examples )

- The importance of alignment in the golden thread

What is the “golden thread”?

The golden thread simply refers to the collective research aims , research objectives , and research questions for any given project (i.e., a dissertation, thesis, or research paper ). These three elements are bundled together because it’s extremely important that they align with each other, and that the entire research project aligns with them.

Importantly, the golden thread needs to weave its way through the entirety of any research project , from start to end. In other words, it needs to be very clearly defined right at the beginning of the project (the topic ideation and proposal stage) and it needs to inform almost every decision throughout the rest of the project. For example, your research design and methodology will be heavily influenced by the golden thread (we’ll explain this in more detail later), as well as your literature review.

The research aims, objectives and research questions (the golden thread) define the focus and scope ( the delimitations ) of your research project. In other words, they help ringfence your dissertation or thesis to a relatively narrow domain, so that you can “go deep” and really dig into a specific problem or opportunity. They also help keep you on track , as they act as a litmus test for relevance. In other words, if you’re ever unsure whether to include something in your document, simply ask yourself the question, “does this contribute toward my research aims, objectives or questions?”. If it doesn’t, chances are you can drop it.

Alright, enough of the fluffy, conceptual stuff. Let’s get down to business and look at what exactly the research aims, objectives and questions are and outline a few examples to bring these concepts to life.

Research Aims: What are they?

Simply put, the research aim(s) is a statement that reflects the broad overarching goal (s) of the research project. Research aims are fairly high-level (low resolution) as they outline the general direction of the research and what it’s trying to achieve .

Research Aims: Examples

True to the name, research aims usually start with the wording “this research aims to…”, “this research seeks to…”, and so on. For example:

“This research aims to explore employee experiences of digital transformation in retail HR.” “This study sets out to assess the interaction between student support and self-care on well-being in engineering graduate students”

As you can see, these research aims provide a high-level description of what the study is about and what it seeks to achieve. They’re not hyper-specific or action-oriented, but they’re clear about what the study’s focus is and what is being investigated.

Need a helping hand?

Research Objectives: What are they?

The research objectives take the research aims and make them more practical and actionable . In other words, the research objectives showcase the steps that the researcher will take to achieve the research aims.

The research objectives need to be far more specific (higher resolution) and actionable than the research aims. In fact, it’s always a good idea to craft your research objectives using the “SMART” criteria. In other words, they should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound”.

Research Objectives: Examples

Let’s look at two examples of research objectives. We’ll stick with the topic and research aims we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic:

To observe the retail HR employees throughout the digital transformation. To assess employee perceptions of digital transformation in retail HR. To identify the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR.

And for the student wellness topic:

To determine whether student self-care predicts the well-being score of engineering graduate students. To determine whether student support predicts the well-being score of engineering students. To assess the interaction between student self-care and student support when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students.

As you can see, these research objectives clearly align with the previously mentioned research aims and effectively translate the low-resolution aims into (comparatively) higher-resolution objectives and action points . They give the research project a clear focus and present something that resembles a research-based “to-do” list.

Research Questions: What are they?

Finally, we arrive at the all-important research questions. The research questions are, as the name suggests, the key questions that your study will seek to answer . Simply put, they are the core purpose of your dissertation, thesis, or research project. You’ll present them at the beginning of your document (either in the introduction chapter or literature review chapter) and you’ll answer them at the end of your document (typically in the discussion and conclusion chapters).

The research questions will be the driving force throughout the research process. For example, in the literature review chapter, you’ll assess the relevance of any given resource based on whether it helps you move towards answering your research questions. Similarly, your methodology and research design will be heavily influenced by the nature of your research questions. For instance, research questions that are exploratory in nature will usually make use of a qualitative approach, whereas questions that relate to measurement or relationship testing will make use of a quantitative approach.

Let’s look at some examples of research questions to make this more tangible.

Research Questions: Examples

Again, we’ll stick with the research aims and research objectives we mentioned previously.

For the digital transformation topic (which would be qualitative in nature):

How do employees perceive digital transformation in retail HR? What are the barriers and facilitators of digital transformation in retail HR?

And for the student wellness topic (which would be quantitative in nature):

Does student self-care predict the well-being scores of engineering graduate students? Does student support predict the well-being scores of engineering students? Do student self-care and student support interact when predicting well-being in engineering graduate students?

You’ll probably notice that there’s quite a formulaic approach to this. In other words, the research questions are basically the research objectives “converted” into question format. While that is true most of the time, it’s not always the case. For example, the first research objective for the digital transformation topic was more or less a step on the path toward the other objectives, and as such, it didn’t warrant its own research question.

So, don’t rush your research questions and sloppily reword your objectives as questions. Carefully think about what exactly you’re trying to achieve (i.e. your research aim) and the objectives you’ve set out, then craft a set of well-aligned research questions . Also, keep in mind that this can be a somewhat iterative process , where you go back and tweak research objectives and aims to ensure tight alignment throughout the golden thread.

The importance of strong alignment

Alignment is the keyword here and we have to stress its importance . Simply put, you need to make sure that there is a very tight alignment between all three pieces of the golden thread. If your research aims and research questions don’t align, for example, your project will be pulling in different directions and will lack focus . This is a common problem students face and can cause many headaches (and tears), so be warned.

Take the time to carefully craft your research aims, objectives and research questions before you run off down the research path. Ideally, get your research supervisor/advisor to review and comment on your golden thread before you invest significant time into your project, and certainly before you start collecting data .

Recap: The golden thread

In this post, we unpacked the golden thread of research, consisting of the research aims , research objectives and research questions . You can jump back to any section using the links below.

As always, feel free to leave a comment below – we always love to hear from you. Also, if you’re interested in 1-on-1 support, take a look at our private coaching service here.

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

38 Comments

Thank you very much for your great effort put. As an Undergraduate taking Demographic Research & Methodology, I’ve been trying so hard to understand clearly what is a Research Question, Research Aim and the Objectives in a research and the relationship between them etc. But as for now I’m thankful that you’ve solved my problem.

Well appreciated. This has helped me greatly in doing my dissertation.

An so delighted with this wonderful information thank you a lot.

so impressive i have benefited a lot looking forward to learn more on research.

I am very happy to have carefully gone through this well researched article.

Infact,I used to be phobia about anything research, because of my poor understanding of the concepts.

Now,I get to know that my research question is the same as my research objective(s) rephrased in question format.

I please I would need a follow up on the subject,as I intends to join the team of researchers. Thanks once again.

Thanks so much. This was really helpful.

I know you pepole have tried to break things into more understandable and easy format. And God bless you. Keep it up

i found this document so useful towards my study in research methods. thanks so much.

This is my 2nd read topic in your course and I should commend the simplified explanations of each part. I’m beginning to understand and absorb the use of each part of a dissertation/thesis. I’ll keep on reading your free course and might be able to avail the training course! Kudos!

Thank you! Better put that my lecture and helped to easily understand the basics which I feel often get brushed over when beginning dissertation work.

This is quite helpful. I like how the Golden thread has been explained and the needed alignment.

This is quite helpful. I really appreciate!

The article made it simple for researcher students to differentiate between three concepts.

Very innovative and educational in approach to conducting research.

I am very impressed with all these terminology, as I am a fresh student for post graduate, I am highly guided and I promised to continue making consultation when the need arise. Thanks a lot.

A very helpful piece. thanks, I really appreciate it .

Very well explained, and it might be helpful to many people like me.

Wish i had found this (and other) resource(s) at the beginning of my PhD journey… not in my writing up year… 😩 Anyways… just a quick question as i’m having some issues ordering my “golden thread”…. does it matter in what order you mention them? i.e., is it always first aims, then objectives, and finally the questions? or can you first mention the research questions and then the aims and objectives?

Thank you for a very simple explanation that builds upon the concepts in a very logical manner. Just prior to this, I read the research hypothesis article, which was equally very good. This met my primary objective.

My secondary objective was to understand the difference between research questions and research hypothesis, and in which context to use which one. However, I am still not clear on this. Can you kindly please guide?

In research, a research question is a clear and specific inquiry that the researcher wants to answer, while a research hypothesis is a tentative statement or prediction about the relationship between variables or the expected outcome of the study. Research questions are broader and guide the overall study, while hypotheses are specific and testable statements used in quantitative research. Research questions identify the problem, while hypotheses provide a focus for testing in the study.

Exactly what I need in this research journey, I look forward to more of your coaching videos.

This helped a lot. Thanks so much for the effort put into explaining it.

What data source in writing dissertation/Thesis requires?

What is data source covers when writing dessertation/thesis

This is quite useful thanks

I’m excited and thankful. I got so much value which will help me progress in my thesis.

where are the locations of the reserch statement, research objective and research question in a reserach paper? Can you write an ouline that defines their places in the researh paper?

Very helpful and important tips on Aims, Objectives and Questions.

Thank you so much for making research aim, research objectives and research question so clear. This will be helpful to me as i continue with my thesis.

Thanks much for this content. I learned a lot. And I am inspired to learn more. I am still struggling with my preparation for dissertation outline/proposal. But I consistently follow contents and tutorials and the new FB of GRAD Coach. Hope to really become confident in writing my dissertation and successfully defend it.

As a researcher and lecturer, I find splitting research goals into research aims, objectives, and questions is unnecessarily bureaucratic and confusing for students. For most biomedical research projects, including ‘real research’, 1-3 research questions will suffice (numbers may differ by discipline).

Awesome! Very important resources and presented in an informative way to easily understand the golden thread. Indeed, thank you so much.

Well explained

The blog article on research aims, objectives, and questions by Grad Coach is a clear and insightful guide that aligns with my experiences in academic research. The article effectively breaks down the often complex concepts of research aims and objectives, providing a straightforward and accessible explanation. Drawing from my own research endeavors, I appreciate the practical tips offered, such as the need for specificity and clarity when formulating research questions. The article serves as a valuable resource for students and researchers, offering a concise roadmap for crafting well-defined research goals and objectives. Whether you’re a novice or an experienced researcher, this article provides practical insights that contribute to the foundational aspects of a successful research endeavor.

A great thanks for you. it is really amazing explanation. I grasp a lot and one step up to research knowledge.

I really found these tips helpful. Thank you very much Grad Coach.

I found this article helpful. Thanks for sharing this.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

100 Questions (and Answers) About Research Methods

- Neil J. Salkind

- Description

"How do I create a good research hypothesis?"

"How do I know when my literature review is finished?"

"What is the difference between a sample and a population?"

"What is power and why is it important?"

In an increasingly data-driven world, it is more important than ever for students as well as professionals to better understand the process of research. This invaluable guide answers the essential questions that students ask about research methods in a concise and accessible way.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

"This is a concise text that has good coverage of the basic concepts and elementary principles of research methods. It picks up where many traditional research methods texts stop and provides additional discussion on some of the hardest to understand concepts."

"I think it’s a great idea for a text (or series), and I have no doubt that the majority of students would find it helpful. The material is presented clearly, and it is easy to read and understand. My favorite example from those provided is on p. 7 where the author provides an actual checklist for evaluating the merit of a study. This is a great tool for students and would provide an excellent “practice” approach to learning this skill. Over time students wouldn’t need a checklist, but I think it would be invaluable for those students with little to no research experience."

I already am using 3 other books. This is a good book though.

Did not meet my needs

I had heard good things about Salkind's statistics book and wanted to review his research book as well. The 100 questions format is cute, and may provide a quick answer to a specific student question. However, it's not really organized in a way that I find particularly useful for a more integrated course that progressively develop and builds upon concepts.

comes across as a little disorganized, plus a little too focused on psychology and statistics.

This text is a great resource guide for graduate students. But it may not work as well with undergraduates orienting themselves to the research process. However, I will use it as a recommended text for students.

Key Features

· The entire research process is covered from start to finish: Divided into nine parts, the book guides readers from the initial asking of questions, through the analysis and interpretation of data, to the final report

· Each question and answer provides a stand-alone explanation: Readers gain enough information on a particular topic to move on to the next question, and topics can be read in any order

· Most questions and answers supplement others in the book: Important material is reinforced, and connections are made between the topics

· Each answer ends with referral to three other related questions: Readers are shown where to go for additional information on the most closely related topics

Sample Materials & Chapters

Question #16: Question #16: How Do I Know When My Literature Review Is Finished?

Question #32: How Can I Create a Good Research Hypothesis?

Question #40: What Is the Difference Between a Sample and a Population, and Why

Question #92: What Is Power, and Why Is It Important?

For instructors

Select a purchasing option.

404 Not found

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research process

- Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

Published on 30 October 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 12 December 2023.

A research question pinpoints exactly what you want to find out in your work. A good research question is essential to guide your research paper , dissertation , or thesis .

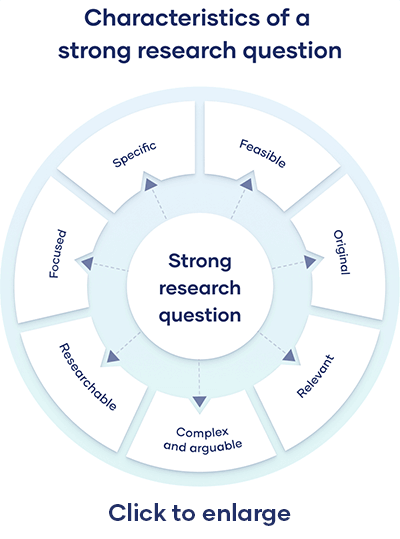

All research questions should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly

Table of contents

How to write a research question, what makes a strong research question, research questions quiz, frequently asked questions.

You can follow these steps to develop a strong research question:

- Choose your topic

- Do some preliminary reading about the current state of the field

- Narrow your focus to a specific niche

- Identify the research problem that you will address

The way you frame your question depends on what your research aims to achieve. The table below shows some examples of how you might formulate questions for different purposes.

Using your research problem to develop your research question

Note that while most research questions can be answered with various types of research , the way you frame your question should help determine your choices.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Research questions anchor your whole project, so it’s important to spend some time refining them. The criteria below can help you evaluate the strength of your research question.

Focused and researchable

Feasible and specific, complex and arguable, relevant and original.

The way you present your research problem in your introduction varies depending on the nature of your research paper . A research paper that presents a sustained argument will usually encapsulate this argument in a thesis statement .

A research paper designed to present the results of empirical research tends to present a research question that it seeks to answer. It may also include a hypothesis – a prediction that will be confirmed or disproved by your research.

As you cannot possibly read every source related to your topic, it’s important to evaluate sources to assess their relevance. Use preliminary evaluation to determine whether a source is worth examining in more depth.

This involves:

- Reading abstracts , prefaces, introductions , and conclusions

- Looking at the table of contents to determine the scope of the work

- Consulting the index for key terms or the names of important scholars

An essay isn’t just a loose collection of facts and ideas. Instead, it should be centered on an overarching argument (summarised in your thesis statement ) that every part of the essay relates to.

The way you structure your essay is crucial to presenting your argument coherently. A well-structured essay helps your reader follow the logic of your ideas and understand your overall point.

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (‘ x affects y because …’).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses. In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, December 12). Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 15 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/the-research-process/research-question/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, how to write a results section | tips & examples, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

Education Scholarship in Healthcare pp 41–50 Cite as

Designing a Research Question

- Ahmed Ibrahim 3 &

- Camille L. Bryant 3

- First Online: 29 November 2023

380 Accesses

This chapter discusses (1) the important role of research questions for descriptive, predictive, and causal studies across the three research paradigms (i.e., quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods); (2) characteristics of quality research questions, and (3) three frameworks to support the development of research questions and their dissemination within scholarly work. For the latter, a description of the P opulation/ P articipants, I ntervention/ I ndependent variable, C omparison, and O utcomes (PICO) framework for quantitative research as well as variations depending on the type of research is provided. Second, we discuss the P articipants, central Ph enomenon, T ime, and S pace (PPhTS) framework for qualitative research. The combination of these frameworks is discussed for mixed-methods research. Further, templates and examples are provided to support the novice health scholar in developing research questions for applied and theoretical studies. Finally, we discuss the Create a Research Space (CARS) model for introducing research questions as part of a research study, to demonstrate how scholars can apply their knowledge when disseminating research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Onwuegbuzie A, Leech N. Linking research questions to mixed methods data analysis procedures 1. Qual Rep. 2006;11(3):474–98. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2006.1663 .

Article Google Scholar

Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2018.

Google Scholar

Johnson B, Christensen LB. Educational research: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2020.

White P. Who’s afraid of research questions? The neglect of research questions in the methods literature and a call for question-led methods teaching. Int J Res Method Educ. 2013;36(3):213–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727x.2013.809413 .

Lingard L. Joining a conversation: the problem/gap/hook heuristic. Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4(5):252–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-015-0211-y .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Dillon JT. The classification of research questions. Rev Educ Res. 1984;54(3):327–61. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543054003327 .

Dillon JT. Finding the question for evaluation research. Stud Educ Eval. 1987;13(2):139–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-491X(87)80027-5 .

Smith NL. Toward the justification of claims in evaluation research. Eval Program Plann. 1987;10(4):309–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(87)90002-4 .

Smith NL, Mukherjee P. Classifying research questions addressed in published evaluation studies. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 1994;16(2):223–30. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737016002223 .

Shaughnessy JJ, Zechmeister EB, Zechmeister JS. Research methods in psychology. 9th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2011.

DeCuir-Gunby JT, Schutz PA. Developing a mixed methods proposal a practical guide for beginning researchers. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2017.

Book Google Scholar

Creswell JW, Guetterman TC. Educational research: planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. 6th ed. New York: Pearson; 2019.

Ely M, Anzul M, Friedman T, Ganer D, Steinmetz AM. Doing qualitative research: circles within circles. London: Falmer Press; 1991.

Agee J. Developing qualitative research questions: a reflective process. Int J Qual Stud Educ. 2009;22(4):431–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390902736512 .

Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Mixed methods research: a research paradigm whose time has come. Educ Res. 2004;33(7):14–26. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x033007014 .

Creamer EG. An introduction to fully integrated mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2018.

Swales J. Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990.

Swales J. Research genres: explorations and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

Kendall PC, Norris LA, Rifkin LS, Silk JS. Introducing your research report: writing the introduction. In: Sternberg RJ, editor. Guide to publishing in psychology journals. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2018. p. 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108304443.005 .

Thomson P, Kamler B. Writing for peer reviewed journals: strategies of getting published. Abingdon: Routledge; 2013.

Lingard L. Writing an effective literature review: Part I: Mapping the gap. Perspectives on Medical Education. 2018;7:47–49.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Johns Hopkins University School of Education, Baltimore, MD, USA

Ahmed Ibrahim & Camille L. Bryant

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ahmed Ibrahim .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

April S. Fitzgerald

Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA

Gundula Bosch

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Ibrahim, A., Bryant, C.L. (2023). Designing a Research Question. In: Fitzgerald, A.S., Bosch, G. (eds) Education Scholarship in Healthcare. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38534-6_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38534-6_4

Published : 29 November 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-38533-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-38534-6

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Davidson D, Ellis Paine A, Glasby J, et al. Analysis of the profile, characteristics, patient experience and community value of community hospitals: a multimethod study. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2019 Jan. (Health Services and Delivery Research, No. 7.1.)

Analysis of the profile, characteristics, patient experience and community value of community hospitals: a multimethod study.

Chapter 2 research objectives, questions and methodology.

In the light of the unfolding policy context and gaps within the existing literature outlined in Chapter 1 , and informed by conversations with key stakeholders (see Patient and public involvement ), this study aimed to provide a comprehensive analysis of the profile, characteristics, patient and carer experience and community engagement and value of community hospitals in contrasting local contexts. The specific objectives were to:

- construct a national database and develop a typology of community hospitals

- explore and understand the nature and extent of patients’ and carers’ experiences of community hospital care and services

- investigate the value of the interdependent relationship between community hospitals and their communities through in-depth case studies of community value (qualitative study) and analysis of Charity Commission data (quantitative study).

In meeting these aims and objectives, the study addressed three overarching research questions (each with an associated set of more specific subquestions as summarised in Table 1 ):

Research questions and objectives

- What is a community hospital? In addressing this question, we drew on existing definitions and conceptualisations of ‘community hospitals’ as outlined in Chapter 1 , Research on community hospitals . Although our emphasis here was primarily empirical and descriptive, we were nevertheless guided by, and sought to contribute to, theoretical debates on definitions of community hospitals and their place within wider health and care systems, drawing on concepts of rural health care, chronic disease and complex care burden, integrated care and clinical leadership.

- What are patients’ (and carers’) experiences of community hospitals? This element of the study was designed to contribute to the conceptualisation of the distinctive elements of community hospitals as understood through the ‘lived experiences’ of patients, rather than just satisfaction ratings. Here, we were influenced by prior analysis of the functional, technical and relational components of patient experience (e.g. environment and facilities, delivery of care, staff) alongside a more theoretical interest in the interpersonal, psychological and social dimensions of patient experience. Very early on in our study, through conversations with patient and public involvement (PPI) stakeholders, we recognised the importance of exploring and understanding the experience not only of patients but also of family carers, and hence we extended our initial question to include both patients’ and carers’ experiences.

- What does the community do for its community hospital, and what does the community hospital do for its community? In addressing this question, we drew on notions of voluntarism and participation and brought together thinking from the separate bodies of literature on volunteering, philanthropy and co-production. This led us to question not just the level of voluntary support for community hospitals but also the different forms it took, how this varies between and within communities, how it is encouraged, organised and managed, and what difference it makes (outcomes). We also drew on notions of social value, including existing typologies, that encouraged us to question different forms of value (e.g. economic, social, human, symbolic) and different stakeholder groups (e.g. staff, patients, communities).

Given the diversity of the questions, we do not set out to provide an over-riding hypothesis or unified theoretical framework for the study as a whole. Instead, these concepts, frameworks and debates served as ‘sensitising categories’, shaping our approach to study design as well as data collection and analysis. 71 We return to these in Chapter 8 and augment them with new concepts that emerged from our analysis.

In addressing these diverse questions, we adopted a multimethod approach with a convergent design. Quantitative methods were employed to provide breadth of understanding relating to the questions concerning ‘what’, ‘where’ and ‘how much’, whereas qualitative methods provided depth of understanding, particularly in relation to questions of ‘how’, ‘why’ and ‘to what effect’.

The research was conducted in three distinct (although temporally overlapping) phases, each with a number of different associated elements and research methods: (1) mapping (database construction and analysis through data set reconciliation and verification), (2) qualitative case studies (semistructured interviews, discovery interviews, focus groups) and (3) quantitative analysis of charity commission data. Table 1 summarises the study objectives, questions and research methods. Each of the three phases of research are discussed in turn through the following sections of this chapter, before the final sections discuss data integration, PPI and ethics.

- Phase 1: mapping and profiling community hospitals

Phase 1 of the research involved a national mapping exercise to address the first study question ‘what is a community hospital?’. It aimed to map the number and location of all hospitals in England to then provide a profile and definition of community hospitals. A database of characteristics would enable the profiling of community hospitals, inform a typology and support a sampling strategy for subsequent case studies. Data were collected from all four UK countries but, in accordance with the brief of the study, this report focuses on England. Reference is made to Scotland’s data as they were important in developing the methodology. The structure of the mapping comprised five elements:

- literature review – constructing a working definition: (see Chapter 1 )

- data set reconciliation – building a new database from multiple data sets

- database analysis – developing an initial classification of community hospitals with beds

- rapid telephone enquiry – refining the classification

- verification – checking and refining the database through internet searches.

The flow of activities is depicted in Figure 1 .

Structure of the national mapping exercise.

Literature review: constructing a working definition

We developed a working definition of a community hospital as drawn from the literature (and as outlined in Chapter 1 ):

- A hospital with < 100 beds serving a local population of up to 100,000 and providing direct access to GPs and local community staff.

- Typically GP led, or nurse led with medical support from local GPs.

- Services provided are likely to include inpatient care for older people, rehabilitation and maternity services, outpatient clinics and day care as well as minor injury and illness units, diagnostics and day surgery. The hospital may also be a base for the provision of outreach services by MDTs.

- Will not have a 24-hour A&E nor provide complex surgery. In addition, a specialist hospital (e.g. a children’s hospital, a hospice or a specialist mental health or learning disability hospital) would not be classified as a community hospital.

The initial enquiry was framed around a ‘classic’ community hospital. The term was drawn directly from the Community Hospital Association 2008 classification, 72 describing classic community hospitals as ‘local community hospitals with inpatient facilities’ (i.e. with beds) and as distinct from community care resource centres (without beds), community care homes (integrated health and social care campus) or rehabilitation units. Although the term ‘classic’ was initially helpful in setting the boundaries of the study, it presented ongoing problems, such as whether it described all community hospitals with beds or a subset within that. Throughout the study, therefore, we have adopted the term ‘community hospital’ and omitted the adjective ‘classic’. Our focus, however, has remained on community hospitals with beds.

Data reconciliation: building a new database from multiple data sets

There was no up-to-date comprehensive database of community hospitals in England. The NHS Benchmarking Network [URL: www.nhsbenchmarking.nhs.uk (accessed 8 October 2018)] membership database was not comprehensive and could not be used to populate our hospital-level database because the data were anonymised. For this reason, one of our first tasks was to compile a new database, by bringing together existing health-care data sets, each of which provided different fields of information needed to test our working definition and to map and profile community hospitals.

Two types of data sets were collected. Centrally available data sets formed the starting point for the mapping study, providing codified data (see Appendix 1 ). As none of these centrally available data sets provided a comprehensive picture, it was necessary to supplement them through extensive internet searching and by talking to people in the field, as well as drawing on the expertise of research team members.

The base year for major data sets was 2012/13. Data were difficult to access, not comprehensive and spread across a greater number of sources. Four data sets were used:

- Community Hospital Association databases of community hospitals (one from 2008 and another from 2013)

- Patient-Led Assessments of the Care Environment (PLACE) 2013 [replacing the former Patient Environment Action Team programme]

- Estates database – Estates Returns Information Collection (ERIC) 2012

- NHS Digital activity by site of treatment 2012/13.

Barriers to obtaining site and activity data included (1) specific difficulties in the period 2012/13 when primary care trusts (PCTs) were being disbanded and clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) were being established (with effect from 31 March 2013) and (2) processes and caution in NHS Digital associated with releasing patient-sensitive data (even though we had not requested patient-based data). Quality problems were associated with the ‘location of treatment’ code, which was central to our enquiry identifying community hospitals but did not appear to be well used in England, leading to examples of missing data and inconsistent labels (described under reconciliation and duplication). The code also lacked stability as it changed with each new NHS reconfiguration in England.

The core data set for England, supplied by NHS Digital, was a list of all hospitals in England, based on ‘site of treatment code.’ Figure 2 shows the relationship between national data sets.

The relationship between four England data sets. CHA, Community Hospitals Associations.

The new database, populated through our reconciliation of these various data sets, provided a census of community hospitals at 2012/13, which was updated to August 2015 (e.g. when a hospital closed and then redeveloped, formed a new hospital replacing two old community hospitals, closed beds on a temporary basis and changed its name).

Database analysis: developing an initial classification of community hospitals with beds

Although the focus of this report is on England, it is important to mention our work on mapping community hospitals in Scotland, as this was instrumental in developing our approach to classifying data for England. Data sets on community hospitals in Scotland [Information Services Division (ISD) and government community hospital data sets: community hospital, general hospital, long-stay/psychiatric hospital, small long-stay hospital] were both more accessible and more comprehensive, lending themselves to early analysis (see Appendix 2 ).

An initial classification of hospitals in England was developed, informed by categories set out by Estates (community hospital, general acute hospital, long-stay hospital, multiservice hospital, short-term non-acute hospital, specialist hospital, support facility, treatment centre) and PLACE (acute/specialist, community, mental health only, mixed acute and mental health/mental health, treatment centre). It was combined with specialty classifications based mainly on NHS Digital inpatient activity data and developed further through analysis of Community Hospitals Association (CHA) data and discussions within the study team ( Table 2 ).

Classification of all hospitals in England

Rapid telephone enquiry: refining the classification

Analysis of the Scotland data suggested that the code ‘GP specialty’ was a defining feature of community hospitals, but early analysis of the England data showed that this was less transferable. If we relied on GP specialty coding alone, many known community hospitals would be excluded from our database: not all community hospital inpatient beds in England were coded to GPs.

A short piece of empirical data collection was undertaken to understand the link between the specialty codes and practice and to test the working definition (based on the literature and on the Scottish data) that community hospitals were predominantly GP led. A telephone questionnaire was designed by the study team (see Appendix 3 ) and piloted through the CHA.

Seven hospitals from five specialty category codes (≥ 80% GP, < 80% GP and mixed specialties, general medicine, geriatric medicine, geriatric mixed specialties) were randomly selected. The test sample of 35 was reduced by four as a result of closure or conversion to nursing homes. The research team called the hospitals to gain contact details of the matron or ward manager ( n = 20; the small sample size highlighting the difficulty of identifying leadership, especially when the community hospital is represented by a single ward), e-mailed the questionnaire, conducted telephone interviews with staff to complete the questionnaire (taking 10–20 minutes each), transcribed notes and returned the completed questionnaire to respondents ( n = 12). Analysis of these telephone interviews gave us confidence in the specialty coding, while also confirming the need to be more expansive in our working definitions and categorisations.

Verification: checking and refining the database through internet searches

The mapping enquiry was finalised through five iterations of searching and checking. The CHA consulted its database and membership list (from both 2008 and 2013). A full internet search took place at two points, in February 2015 and August 2015, taking account of hospital closures and changes of function up to 2014/15, with further validation and amendments up to August 2015. By the end of the study, the 2012/13 data set, based on the NHS Digital Spine using ‘site of treatment code’, had been validated through a check of every potential community hospital. A total of 366 sites were examined through web-based and telephone enquiries, including 60 that were not present on the NHS Digital database (see Appendix 4 for the list of community hospitals with beds).

- Phase 2: case studies

In order to explore patient and carer experience of community hospitals and aspects of community engagement and value, we undertook qualitative case studies. Although the initial aim of the case studies was to address the second and third research questions, the findings also enabled new insights into the first study question of ‘what is a community hospital’.

The decision to adopt a comparative case study design 73 across multiple community hospital sites was influenced by three factors. First, given the gaps in the literature highlighted in Chapter 1 , it would be useful to uncover different aspects of the patient experience, community engagement and value of community hospitals and enable the identification and analysis of common themes (looking for similarities, differences and patterns) both within and across cases. 74 – 76 Second, it provides a suitable way of ‘exemplifying’ sites, 77 given the variety of ownership models and locations. Third, it is useful in enabling an examination of ‘complex social phenomena’, 78 and, in particular, the social, functional, interpersonal and psychological factors that shape patient experiences, as well as those that influence community engagement and value. Below, we summarise the approach to case study selection for work packages 2 and 3, before moving on to discuss the research elements used.

Selection of case study sites

In selecting case study sites, we adopted a ‘realist’ approach to sampling, 79 moving back and forth between categories identified from the literature as being important for patient experience and community value and our learning about the characteristics of community hospitals identified from the mapping exercise. In order to reflect the diversity of community hospitals (highlighted in the literature and mapping), we selected cases in contrasting locations with different numbers of beds, ranges of services, ownership/provision and levels of voluntary income and deprivation.

To allow for a particular focus on variations in voluntary support for community hospitals, hinted at through the national mapping exercise and identified as a particular gap in the existing literature, we selected pairs of hospitals across four Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) areas with contrasting levels of voluntary income but similar levels of deprivation. This would allow for a good comparison within and between cases (e.g. why two community hospitals within one CCG area, with similar levels of deprivation, have contrasting levels of voluntary support, given that previous research has tended to suggest a strong negative correlation between deprivation and voluntary activity).

Using these criteria, we selected eight case studies of hospitals of different sizes, ages and service profiles located across England (although mostly concentrated in the south, reflecting the national pattern of community hospital development; see Figure 7 ) in areas of contrasting levels of deprivation. Six of the buildings were owned by, and their main inpatient service was provided by, the NHS. Two were owned by the NHS but their main inpatient services were provided by a community interest company (CIC). We added a ninth case study, owned by a charity, to increase diversity in terms of ownership/provision (as there were very few examples of independently owned community hospitals, it was not possible to identify a matched pair). Table 3 provides a summary of the nine case studies selected, according to the data that were available from the mapping exercise. Fuller qualitative descriptions are provided in Chapter 4 and Appendix 5 .

Profile of selected case studies

Case study data collection

The case studies involved seven research elements, as summarised in Table 4 . All elements were conducted over five visits to each case study. Across all case study sites and research methods, 241 people participated in the study through interviews and 130 people participated through 22 focus groups; a small number of people who participated in individual interviews also participated in focus groups (see Appendix 6 for full details).

Research elements and focus

Scoping visits were made to each of the case studies in order to build relationships with key stakeholders (primarily matrons and chairpersons of Leagues of Friends), gather background information on the hospitals and local communities, identify potential study participants and collect key documents and data. Documents selected included hospital histories, annual reports, local service information (when available) and media coverage. Reviewing these helped to provide a basic understanding of the cases prior to the main fieldwork visits and added to our profiling of each of the case study hospitals.

We also aimed to gather hospital-level data from patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) 80 and the revised Friends and Family Test (FFT). 81 However, none of the case study community hospitals collected PREMs data, as this had only recently been required of community providers. Although all sites collected FFT scores, we were able to access data for only seven of the nine case studies because, in the remaining two cases, the trust compiled data at trust rather than hospital level and it was not possible to disaggregate the data. Furthermore, the FFT data were not strictly comparable as some scores covered inpatient care only, whereas others covered both inpatient and outpatient care.

Local reference group

We established a local reference group (LRG) in each of our case studies to bring local people together to steer, support and inform the research at the local level. These LRGs comprised key members of hospital staff, the League of Friends, volunteers and local voluntary and community groups, some of whom had also been patients and/or carers. Their role was to help build a picture of the local context to inform subsequent data collection elements, build support for the study within the local community and reflect on emerging findings and their implications for local practice. There were two LRG meetings per case study during the local fieldwork stage: one at the start of the fieldwork period (which focused on mapping the community hospital services and community links) and one at the end (which focused on discussing the emerging findings and their potential implications). The first LRG meeting for CH3 and CH4 was joint (for convenience) but the second meeting was separate. Following completion of the fieldwork and analysis, each LRG received a report of the findings relating to their specific case study (i.e. alongside this national report, we produced nine local reports).

Semistructured interviews with staff, volunteers and community representatives

We conducted semistructured interviews with staff ( n = 89 staff across the nine cases), community stakeholders ( n = 20) and volunteers ( n = 35). Although most of the interviews were with single respondents, some were with two or, very occasionally, three people (depending on respondent preferences). Respondents were selected through purposive sampling 79 guided by the scoping visits, the initial LRG and snowballing. Each of the interviews explored the profile of the hospital and the local context, perceptions of patient and carer experience, and community engagement and value. The emphasis placed on the different sets of questions, however, varied between the groups of respondents (e.g. more time was spent on community engagement and value within the community stakeholder interviews, although we still asked questions relating to hospital profile and perceptions of patient/carer experience). Interviews were nearly all conducted face to face, although a small number were conducted via telephone, at respondent preference. Interviews with staff, volunteers and stakeholders lasted, on average, 60 minutes. All were digitally recorded and later transcribed verbatim.

Discovery interviews with patients

Rather than focusing on satisfaction levels, or other quantifiable measures of experience, the study was concerned with exploring the lived experience of being a patient using community hospital services. Lessons from previous studies show that gathering experiences in the form of stories enhances their power and richness, 36 so we selected an experience-centred interview method 82 that drew on the principles of narrative approaches 83 and, particularly, discovery interviewing. 84 Narrative approaches invite respondents to tell their stories uninterrupted, rather than respond to predetermined questions, giving control to the ‘storyteller’. This approach can elicit richer and more complete accounts than other methods 85 , 86 because reflection enables respondents to contextualise, and connect to, different aspects of their experiences. Discovery interviewing helps to capture patients’ experiences of health care when there may be pathways or clinical interventions central to patient experience. 87 As such, after a general opening question, our interviews focused around a very open question inviting respondents to tell their story of being a patient at the community hospital. We followed this by asking respondents to consider a visual representation we had developed of factors found in previous research to have shaped patient experience, to prompt people’s memories and thoughts (see Appendix 7 for an example of the discovery interview).

Our aim was to interview six patients from each case study. Our final sample across all sites was 60 patients. The small sample size reflected the in-depth nature of the interviews. We sought, as far as possible, to select patients with a mix of demographics (particularly in terms of gender), care pathways (particularly in terms of step up/step down) and services used (inpatient/outpatient). Potential participants were identified by the hospital matron and/or lead clinician and/or service leads. Each was written to by the hospital with a request to participate in the study and was sent an information sheet and an opt-in consent form. Patients who were willing to participate sent their replies directly to the study team. Written consent was provided prior to the commencement of the interview. In line with the Mental Capacity Act 2005 Code of Practice, 88 we made provision for the appointment of consultees when potential respondents lacked the capacity to consent to participation in the study, although this was not utilised.

Although many of our respondents were current inpatients, we also spoke to some inpatients who had been recently discharged and to outpatients from a range of different clinics. Outpatients who agreed to participate tended to be those using services several times a week (e.g. renal patients) or over a longer period of time (e.g. those with chronic conditions), rather than one-off users. Interviews with patients lasted between 30 and 90 minutes, were digitally recorded (in all cases except for two because of respondent preference/requirements) and transcribed verbatim. At the end of the interviews, we asked respondents to complete a short pro forma to gather basic demographic and service information for analysis purposes.

Semistructured interviews with carers

Semistructured interviews were conducted with carers in order to explore their experience of using the community hospital as a carer of an inpatient. Our aim was to interview three carers per case study; in total we spoke to 28 carers across the nine sites. Carers were either related to, or close friends of, patients (either current or recent) at the hospital. In most cases, we interviewed carers of patients who had also been interviewed, but in some cases carers were not directly linked to patients involved in the study (indeed, some carers were reflecting on the experience of caring for a patient who had recently died).

The main focus of the interviews was on the experience of being a carer of someone at the hospital, with our initial question reflecting the narrative approach adopted for patients by asking respondents to tell us their story of using the hospital. In addition, as the respondents were typically local residents, we also asked questions about their perceptions of patient experience, about local support for, and engagement with, the hospital and of value. Interviews with carers lasted, on average, 60 minutes. All were digitally recorded and later transcribed verbatim.

Focus groups

We conducted focus groups with members of MDTs, volunteers and community stakeholders. Although we had anticipated conducting each of the three focus groups in each of the case study sites, this was not always possible owing to practical reasons; for example, in some of the case study sites there were very few volunteers, making it difficult to organise a focus group. We ran focus groups with MDTs in eight of the nine case studies, involving a total of 43 respondents; with volunteers in six of the case studies, involving a total of 33 respondents; and with community stakeholders in eight of the cases, involving 54 respondents. Individual focus group respondents were selected through purposive sampling. We worked with LRGs and other key contacts to identify potential participants, each of whom was written to and asked to participate.

The focus groups complemented the interviews, enabling the inclusion of a wider range of perspectives in the study and, in particular, allowing us to observe the emergence of discussion, consensus and dissonance among groups of participants. They lasted, on average, 90 minutes and were digitally recorded and transcribed in full.

Telephone interviews with managers and commissioners

We conducted telephone interviews to explore the views of senior managers of provider organisations and commissioners of community hospitals. The nine case studies were based in five CCG areas where the main inpatient services were provided by four NHS trusts and one integrated health and social care CIC. Our aim was to interview one respondent from each of the providers and CCGs. In total, we spoke to five provider and four CCG representatives. The interviews explored the strategic context for the community hospitals involved in the study, alongside the perceptions of these senior stakeholders of patient experience and the value of community hospitals. The interviews lasted, on average, 60 minutes and were digitally recorded and later transcribed in full.

Qualitative case study data analysis

We adopted a thematic approach to qualitative data analysis, aided by the use of NVivo 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) for data management and exploration. Our approach was both inductive, with themes emerging from the data, and deductive, framed by our research questions and ongoing reading of the literature. Initial themes and codes were developed after three members of the team (AEP, DD and NLM), who collectively had been responsible for the case study data collection, reviewed the transcripts. The emerging themes, codes and associated findings were discussed at wider study team meetings, at the LRG meetings for individual case studies and at annual learning events that brought together participants from across the case studies. A refined coding frame was then tested by the same three members of the research team each coding a sample of transcripts; this led to a further refinement of the codes, while also helping to ensure that each of the researchers was adopting a similar approach.

In this report, we focus in particular on across-case comparisons, highlighting themes that emerged across the case studies, emphasising key points of similarity and difference between the cases, as relevant. In addition, we have produced individual reports for each of the local case study sites that have shared findings from our within-case analysis, as relevant for each individual hospital. Comparative analysis, including of the paired cases, will be developed further in future research articles, in which a focus on more specific aspects of the study will allow more space for presentation of such work.

Throughout the analysis, unique identifiers were used for the transcripts/respondents to help ensure confidentiality and anonymity. Sites were assigned a number (e.g. CH1) and respondents given a letter: patient (P), family carer (CA), staff (S), volunteer (V), community stakeholder (CY) and senior manager or commissioner (T), with sequential numbering, date of interview and initials of researcher added to provide an audit trail. This basic coding method is used throughout the report (e.g. CH1, S01 represents the first staff member to be interviewed at the first community hospital case study site). It is worth noting, however, that, although respondents were identified by a key characteristic (e.g. patient or staff) and their transcripts labelled as such, the boundaries between these categories were not discrete: many community stakeholders, for example, had also been patients or carers, and many staff were also members of the local community.

- Phase 3: quantitative analysis of Charity Commission data

Collating data on charitable finance and volunteering support

The third phase of our research involved the quantitative analysis of data from the Charity Commission on voluntary income and volunteering for community hospitals across England. The aim of this activity was to examine charitable financial and volunteering support for community hospitals by investigating:

- variations in the likelihood that hospitals receive support through a formal organisational structure such as a League of Friends, and if so, variations in its scale (in financial terms) between communities

- uses of the funds raised (e.g. capital development, equipment, patient amenities).

We captured financial and volunteering data for registered charities from the Charity Commission (the Commission). The Commission holds details of organisations that have been recognised as charitable in law and that hold most of their assets in England, or have all or the majority of their trustees normally resident in England, or are companies incorporated in England. The data are described more fully in Appendix 9 .

Subject to a small number of exceptions, all charities in England with incomes of > £5000 must register with the Commission and submit financial statements consisting of trustees’ annual reports (returns) and annual accounts. The accounts of those charities whose income or expenditure exceeds a threshold of £25,000 are made available on the Commission’s website. 89 Charities that have income and expenditure of < £5000 a year have (since 2009) been exempted from the need to register. We identified 274 hospitals in England that satisfied the inclusion criteria for this research project ( Figure 3 ). We used the Charity Commission’s data to identify charities that support each of these hospitals, matching by name or through examining lists of charities registered in the locality where the hospital is based.

Community hospital and charities sampling frame.

We also directly approached eight non-registered charities (usually those with an income of < £5000 a year) that were known to have been established to support specific community hospitals, but received no usable data relating to them. Four hospitals in our data set were registered as charities themselves but were excluded from the analysis because they are exceptional cases of charitable action.

We found that 247 of these charities were registered in their own right (labelled ‘individual associated charities’ in Figure 3 ). The remainder were what is known as ‘linked’ charities, that is, entities associated with larger charitable organisations serving a NHS trust comprising several institutions. These ‘linked’ charities were excluded because it was not possible to disaggregate the support they provide to individual components of the trust. Financial information was available for the period from 1995 to 2014 (only small numbers of observations were available for years prior to that because digitisation of the register began only in the early 1990s).

Measurements

Financial information for at least 1 year between 1995 and 2014 was available for 245 charities in England, and this information formed the final sample for this part of the study. The number of non-zero financial reports to the Commission in each year ranged from 181 (1996) to 226 (2007). The data, covering the period to 2014, were the latest available at the time of analysis (2016). See Appendix 9 for full details of available charity reports by year. All financial information in this paper is presented at constant 2014 prices.

Using the Charity Commission website, we obtained copies of these accounts for those selected charities whose expenditure or income exceeded £25,000 in any one year. This gave data covering 358 separate financial years; the number of accounts available is shown in Table 5 .

Accounts for larger charities (income of > £25,000)

We focused on the period from 2008 to 2013, when between 41 and 91 charities of interest generated at least one such financial return. Numbers vary because an individual charity may or may not exceed the £25,000 threshold at which its accounts are presented via the Charity Commission’s website, depending on fluctuations in its finances.

Charity accounts aggregate income and expenditure figures into a small number of general categories. These provide relatively little detail on income and expenditure and may even aggregate quite different sources of expenditure within the same funding stream. As such, to probe income sources and the application of expenditure in more detail, data were captured from the notes to the accounts of these charities. The extensive income data that were generated (21,733 items) were categorised to provide useful insights into sources of income. Classifying the expenditure of charities was not undertaken because of the complexity of the data and the limits to the usefulness of such an exercise. Appendix 9 provides further details of the extraction, classification and analysis of income and expenditure data.

Contribution: number of volunteers and estimates of input

The Charity Commission guidelines 90 require charities to record their best estimates of the number of individual UK volunteers involved in the charity during the financial year, excluding trustees (see Appendix 9 ).

Before 2013, data on volunteer numbers were often sparse, but, since that date, efforts have been made to gather more detailed information. Approximately 73,000 charities had supplied between one and three non-zero returns of their volunteer counts in the three years between 2013 and 2015, including > 90% of our charities. We calculated the average number of volunteers for the period in question. To provide an upper-bound estimate, we also take the maximum value returned for each charity.

Volunteer hours were estimated using regular survey data (Home Office Citizenship Survey, 2001–10; Community Life survey, 2012 onwards). We take the average number of hours per week reported by those who say they have given unpaid help to organisations during the previous year. This is approximately 2.2 hours. This is a minimum estimate and it may be that the actual numbers are larger than these survey data would imply. If we make the assumption that these are probably fairly regular volunteers, a higher figure of 3.05 hours per week is given if we take the average number of hours reported by those who say they volunteer either at least once a week or more frequently, or at least monthly but less frequently than once a week.

There are no studies that would tell us with any certainty whether or not volunteers in these kinds of organisations put in more or fewer hours than the volunteering population generally. We then multiply these two estimates of time inputs by the average and maximum volunteer numbers, respectively, to give the number of hours contributed by volunteers over the course of the year (assuming 46 weeks of volunteering a year). These can be converted to full-time equivalent numbers by dividing by 37.5 (hours per working week) and 46 (weeks per working year).

Opinions differ on the best method for calculating a cash equivalent for the value of volunteer labour. The lowest is to use the national minimum wage; others might include an estimate of the replacement cost (i.e. what it would cost the organisation to employ people to do the same tasks if they had to pay them), but this assumes knowledge of the tasks being undertaken. The national minimum wage for the period for which we have the most comprehensive volunteering data (2013–15) was £6.50 per hour. 91

Data convergence and integration

Although the quantitative (phases 1 and 3) and qualitative (phase 2) data were collected separately, they could nevertheless be considered ‘integrated’ because the different research elements were explicitly related to each other within a single study and in such a way ‘as to be mutually illuminating, thereby producing findings that are greater than the sum of the parts’. 92 Data triangulation, convergence and integration occurred in a number of different ways, at different stages of the research.

In phase 1 of the research, a revised definition and set of characteristics captured within the database was used to support development of a typology and informed the case study sampling for phase 2. For phase 3, the database informed the sample of charities selected for analysing voluntary income and volunteering data and providing additional data fields to be linked to the Charity Commission data.

Although the national quantitative data provided breadth to the study, these were limited and left questions unanswered. The local qualitative data brought depth to the question ‘what is a community hospital’, by helping to build a picture of the history, context and change over time. Qualitative interviews in work packages 2 and 3 were conducted concurrently, and triangulation of data between stakeholder, volunteer, staff, carer and patient interviews helped validate findings and strengthen our understanding of patient and carer experiences and community engagement and value.

In addition, the combination of researchers working on more than one work package, reflexive team meetings and the involvement of different representations in the team [CHA, University of Birmingham and Crystal Blue Consulting (London, UK)] allowed for healthy dialogue, debate and analysis. Emerging findings from each phase of the research were, for example, shared through internal working papers and discussed regularly at whole project team meetings.

- Patient and public involvement

Our commitment to PPI ensured that patients, carers and the public were involved in this study before and during its conduct. PPI involvement in the study design was facilitated by one of the researchers (HT), who first consulted with 10 PPI members of the Swanage Health Forum, representing the League of Friends; a GP practice Patient Participation Group; Swanage Carers; Partnership for Older People’s Programme; Wayfinders; the Senior Forum; the Health and Wellbeing Board; Cancare; a public Governor for Dorset Healthcare NHS Trust; and a retired GP. This group provided an endorsement of the study’s proposed focus and methodology.

At the national level, 13 board members of CHA (four GPs, six nurses, two managers and one League of Friends member) co-produced the initial research proposal. Two members then became part of the study steering group, which met regularly throughout the study, supported the development of research materials and supporting documentation, helped facilitate access to potential case studies, contributed to the local and national reports and reviewed several drafts. We also engaged with approximately 100 delegates at three CHA annual conferences (presentations and workshops focused on working with findings) that included not only practitioners but members of community hospital Leagues of Friends.

In addition, a cross-study steering group, chaired by Professor Sir Lewis Ritchie, University of Aberdeen, provided guidance across all three Health Services and Delivery Research community hospital studies, with representation from the CHA, Attend (National League of Friends) and the Patients Association, alongside the three study teams. The steering group met seven times over the period of this study, offering opportunities to share findings and explore experiences between the studies.

As described in Local reference group , at the local level we established LRGs within each of our case study sites to bring local people together (hospital staff, volunteers and community members, a number of whom were patients and/or carers) to steer, support and inform the case study research. To facilitate cross-case learning, we brought together representatives from each of the LRGs three times to share experiences, identify best practice and network. Event themes reflected each of the three research questions, and the days offered time for case study representatives to work together, share across sites, hear from national experts, contribute to the ongoing development of the study and reflect on emerging findings and their implications.

- Ethics approval

Ethics approval was provided by the University of Birmingham, in line with the Department of Health and Social Care’s Research Governance Framework, for work package 1 (national mapping) and elements of work package 3 (quantitative charitable finance and volunteering support data). The university also provided sponsorship for the whole study. The qualitative case studies required full ethics review through the National Research Ethics Service as they involved interviews with patients and carers and interviews and focus groups with NHS staff, volunteers and community stakeholders. The Wales Research Ethics Committee 6 reviewed this research and provided a favourable ethics opinion (study reference number: 16/WA/0021).

Informed by key stakeholder engagement and a review of the policy context and existing literature, this study explored the profile, characteristics, patient and carer experience, community engagement and value of community hospitals in England through a multimethod approach. The research was conducted in three overlapping phases – mapping, case studies and Charity Commission data analysis – that, together, involved a range of qualitative and quantitative methods. Data for each phase were collected and analysed separately but iteratively, with emerging findings discussed regularly through a range of mechanisms, including whole project team meetings and internal working papers. We involved key national and local stakeholders throughout the study, from design, through to data collection and analysis, and reporting and dissemination.

Having framed the study (see Chapter 1 ) and described our research methodology (see Chapter 2 ), we now move on to share the findings. Chapters 3 – 7 describe the findings emerging from different elements of the study, and Chapter 8 brings those findings together and discusses them in relation to the wider literature and their significance for knowledge and practice.

- Cite this Page Davidson D, Ellis Paine A, Glasby J, et al. Analysis of the profile, characteristics, patient experience and community value of community hospitals: a multimethod study. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2019 Jan. (Health Services and Delivery Research, No. 7.1.) Chapter 2, Research objectives, questions and methodology.

- PDF version of this title (6.1M)

In this Page