Research on Literary and Art Development Latest Publications

Total documents, published by world scientific publishing house ltd.

- Latest Documents

- Most Cited Documents

- Contributed Authors

- Related Sources

- Related Keywords

Using Backlight - Using Backlight to Create Dramatic Sense in Film Photography

Research on control ability and training of excellent latin dancers, exploring the construction of curriculum system and talent training mode of art management in colleges and universities, research on innovative design of lamps and lanterns in the yangtze and huaihe river culture, a preliminary study on the cultivation mode of animation talents based on “modern apprenticeship”, three men contributing to emily’s tragedy of love: analysis of “a rose for emily” from the perspective of masculinities, research on the artistic characteristics of the gift of the magi, teaching reform research on 3d digital sculpture technology in academy of fine arts laboratory, on the rural revitalization promoted by festival sports culture: taking the culture of liangshan torch festival as an example, practice and reflection on teaching civics in higher vocational english courses, export citation format, share document.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 03 November 2021

The role of literary fiction in facilitating social science research

- Bryan Yazell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2263-3488 1 , 2 ,

- Klaus Petersen 2 , 3 ,

- Paul Marx 3 , 4 , 5 &

- Patrick Fessenbecker 6 , 7

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 261 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

6936 Accesses

2 Citations

15 Altmetric

Metrics details

Scholars in literature departments and the social sciences share a broadly similar interest in understanding human development, societal norms, and political institutions. However, although literature scholars are likely to reference sources or concepts from the social sciences in their published work, the line of influence is much less likely to appear the other way around. This unequal engagement provides the occasion for this paper, which seeks to clarify the ways social scientists might draw influence from literary fiction in the development of their own work as academics: selecting research topics, teaching, and drawing inspiration for projects. A qualitative survey sent to 13,784 social science researchers at 25 different universities asked participants to describe the influence, if any, reading works of literary fiction plays in their academic work or development. The 875 responses to this survey provide numerous insights into the nature of interdisciplinary engagement between these disciplines. First, the survey reveals a skepticism among early-career researchers regarding literature’s social insights compared to their more senior colleagues. Second, a significant number of respondents recognized literary fiction as playing some part in shaping their research interests and expanding their comprehension of subjects relevant to their academic scholarship. Finally, the survey generated a list of literary fiction authors and texts that respondents acknowledged as especially useful for understanding topics relevant to the study of the social sciences. Taken together, the results of the survey provide a fuller account of how researchers engage with literary fiction than can be found in the pages of academic journals, where strict disciplinary conventions might discourage out-of-the-field engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Conceptualizing science diplomacy in the practitioner-driven literature: a critical review

Pierre-Bruno Ruffini

Lifting the smokescreen of science diplomacy: comparing the political instrumentation of science and innovation centres

Elisabeth Epping

A bibliometric analysis of cultural heritage research in the humanities: The Web of Science as a tool of knowledge management

Ionela Vlase & Tuuli Lähdesmäki

Introduction

Interdisciplinary research has become the buzzword of university managers and funding agencies. It is said that researchers need to think out of the box, be innovative and agile, and—last but not least—be curious about other disciplines in order to solve the complex challenges of the modern world. The tension inevitably generated by calls for more interdisciplinary work between university administrators on the one side and researchers on the other risks obscuring a fundamental question: what exactly is new about interdisciplinary research in the first place? For all the handwringing about interdisciplinarity, there is no clear consensus about what the boundaries of a given discipline are in the first place. Debates have waged over the last several decades about the divisions between the sciences and the humanities, their origins, and possible methods for rectifying them. Perhaps most famously, British scientist and novelist C.P. Snow identified “two cultures” in the academy separated by “a gulf of mutual incomprehension” ( 1961 , p. 4). According to Snow, “literary intellectuals” and “physical scientists” not only distrusted each other’s pronouncements, but fundamentally saw the world differently ( 1961 , p.4, 6). Although this assessment has been influential in framing these respective disciplines for decades, its presentation of a binary division between the hard sciences and the arts does not account for the fields of study with overlapping interests and, at times, borrowed methodological tools: the social sciences and literature departments.

The social sciences and literary studies share an indelible link by virtue of their twinned emergence as academic disciplines in the early twentieth century. Both disciplines in the broadest sense share a keen interest in understanding and describing human behavior and social relationships. However despite—or perhaps owing to—these similarities, the disciplines have historically identified themselves in terms of opposition. On one side, Émile Durkheim’s Rules of Sociological Method, published in 1895, defined the discipline in terms of positivism and quantitative study. On the other side, foundational literature scholars such as Matthew Arnold and F.R. Leavis understood literary study as a crucial component to the project of invigorating the national culture: to identify among the mass of popular culture the most elite examples of art. Critics in this early school of literary study therefore understood literature less as a mirror of society and more as a way to access what is best about cultural ideals or humanistic achievement (Arnold, 1873 ; Leavis, 2011 ). In this early context, social scientists were more interested in making society itself the object of study. While the features of each respective field have undoubtedly changed dramatically over the past century, this underlying division regarding the “science” in the social science persists. If the social scientist and literature scholar can speak with some degree of shared comprehension, they nonetheless are beset by disciplinary boundaries that make the task of mutual exchange harder than it might otherwise appear.

The decision to better document the uses of literature within the social sciences was born from an overarching drive to understand literature’s impact on researchers that often escape notice. After all, literary scholars are in general familiar with (if not thoroughly informed by) the works of sociologists, economists, and political scientists. Moreover, they are likely to be comfortable both with using the toolset of the social sciences in their own work and, more to the point, citing sociologists such as Émile Durkheim, Erving Goffman, and Bruno Latour. Over the last decade, for instance, several prominent literary scholars have advocated for a descriptive model for analyzing literary texts modeled on the social sciences (e.g., Love 2010 ; Marcus and Love, 2016 ). This relatively recent turn to the social sciences does not begin to consider, of course, the much longer history of literary scholars drawing critical concepts from the Frankfurt School (such as Theodor Adorno or Jürgen Habermas) or, more significantly, the works of Karl Marx. All of which is to say, one can easily expect references to sources broadly associated with the social sciences when reading a literary studies monograph.

However, if it is clear that literary scholars are familiar with prominent works by social scientists, it is much less apparent if the reverse is true. In an essay in World Politics, the political scientist Cathie Jo Martin outlines the profound insight literary sources can offer the field. Novels and other literary fiction provide “a site for imagining policy”, help define shared group interests, and create narratives that legitimize systems of governance (Martin, 2019 , p. 432). Elsewhere, Nobel prize-winning economist Robert J. Shiller calls for greater engagement with literature and fiction in Narrative Economics (2019). However, as we show below, cases of social scientists explicitly acknowledging literary sources are few and far in between. Rather than articulate yet another call for better dialog between the disciplines, we instead seek greater insight into the way social scientists are already referring to, engaging with, or simply using literature in their field as researchers and teachers. As explained in detail below, this task is not as straightforward as it may seem.

Our project proceeded in two steps. The first was a qualitative study of social science articles that included references to literary authors drawn from the collection of social science journals cataloged on the JSTOR digital library. The evaluation of literary references captured in our study (outlined below) made it possible to track the proliferation of literary sources across social science research and to create a loose typology of these uses. For the second step, we developed a survey for social science researchers to elaborate on how, if at all, their work engages with works of literary fiction. Before going into the field, the survey was tested and discussed with a small number of academics to ensure that the items capture the concepts of interest. The survey was then sent electronically to 13,784 researchers at all stages (from PhD students to full professors) from the top 25 social science departments as ranked in 2019 by Times Higher Education (World University Rankings).

If academic departments are guardians of their disciplines, then this sample of prominent departments might reflect the international standard for their respective fields. In other words, researchers attached to these institutions may be more inclined to protect conventions than to go against the grain. In contrast, we can imagine that scholars at smaller schools, colleges, or cross-disciplinary research centers might be more inclined to engage with other disciplines. Focusing on the former institutions rather than the later, our survey finds hard test cases for our questions about the use of literary references in social sciences. Finally, by calling attention to the different forms of influence literature may (or may not) assume, the survey made it possible to dwell in more detail on how social scientists esteem literary fiction as a tool for understanding social concepts.

Before conducting our survey, we first developed a typology of what we term uses of literature within the social sciences. This typology is the result of an ongoing project seeking to understand how literature might already play a role in the social sciences, no matter how small this role might appear at first glance. Our investigations were further motivated by the distinct lack of sources on the subject. While there are a number of prominent cases that call for social scientists to incorporate the insights of literature into their research (e.g., Shiller, 2019 ) and teaching (e.g., Morson and Schapiro, 2017 ), there are hardly any that demonstrate how (and where) they might already be doing so. For those of us who wish to expound on the value of not only literature per se but the study of literature specifically, a thorough account of how experts in an adjacent field like social science might already incorporate literary objects in their scholarship is a critical starting point. The absence of a generalized account of the field therefore required us to generate our own.

To do so, we first devised a plan to comb through the entire catalog of published social science articles on JSTOR, which spans nearly a century’s worth of material. Our goal at this point was to identify and categorize where and how social scientists refer to literary fiction in their published work. As will become clear, this approach’s limitations—namely, its reliance on a pre-determined list of searchable terms—set the groundwork for our survey, which was designed to account for surprising or unexpected responses. Nevertheless, the survey provided valuable insight into the more fleeting references to literary fiction in published social science research.

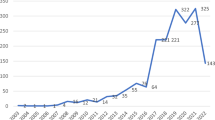

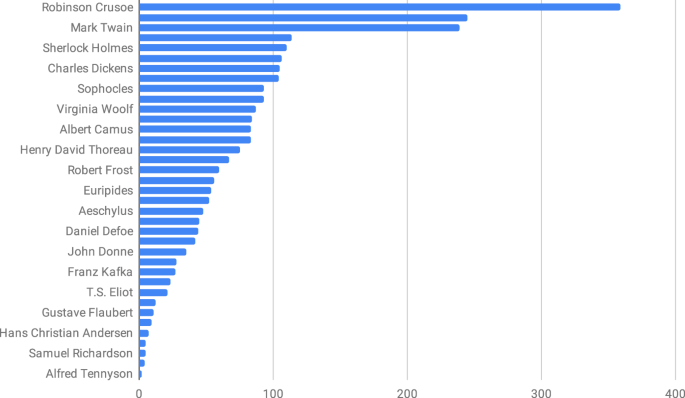

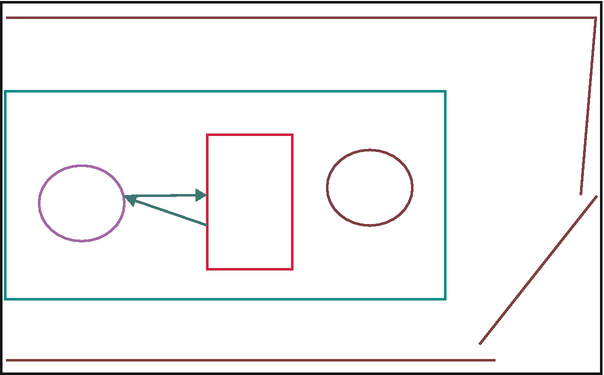

A brief account of this JSTOR project is useful for contextualizing the results of our social science survey. First, it was necessary to generate a delimited archive of social science articles that use, in some shape or another, literary sources. For the sake of producing an adequate number of sources, we composed a list of search terms that consisted of 30 prominent Anglophone authors, along with two famous literary characters, Robinson Crusoe, and Sherlock Holmes (Fig. 1 ). To determine these search terms, we cross-referenced popular online media articles (including blogs, short essays, and user forums) that offered broad rankings of, for example, the most important authors of all time. To best address the historical breadth of the JSTOR catalog, the names were edited down further to focus on authors who published before the middle of the twentieth century. It goes without saying that this initial list was far from exhaustive. Instead, it was intended to produce a large enough body of results in order for us to further generate a working typology of literary references as they appeared in the articles. Footnote 1 Second, we conducted a qualitative analysis of these articles alongside the rough typology of uses Michael Watts, Professor of Economics at Purdue, outlines in his study of economics and literature—the only workable typology we found.

Chart displays search terms (author name or fictional character name) and their corresponding total number of appearances across all social science articles on JSTOR. Figure shows 19 most popular results from the compiled search term list.

According to Watts, economists who engage with literature to any degree tend to do so according to four different categories: 1. eloquent description of human behavior; 2. historical evidence conveying the context of a particular time or place; 3. Alternative accounts of rational behavior that complement or challenge economic theory; 4. Evidence of an antimarket/antibusiness orientation in esthetic works. ( 2002 , p. 377)

When viewed alongside the JSTOR articles, however, the limitations to Watts’s typology were apparent. Most immediately, the emphasis on what one might call deep or sustained engagements with literature means that his typology will not capture those more fleeting uses of literature that make up the vast majority of literary references in the social science archive. Once one recognizes these limits, it becomes clear that any categorization or typology of literature in social science must be sufficiently flexible enough to capture the many and often surprising ways that the disciplinary fields might intersect. Of course, this latter point is underscored by the fact that Watt’s original typology is concerned with economics only. By expanding our search to include the social sciences in general, we allow for a wider scale for evaluating literature’s usefulness as seen by, for instance, political scientists, social theorists, and behavioral economists. After reviewing the JSTOR set of articles, we expanded on Watt’s initial typology to produce a more encompassing categorization of literary uses that better accommodated the range of literary references as they appeared in the archive. Ultimately, we determined that an expanded typology of uses of literature as they appear in published social science articles must include several more categories, never mind the four in Watts’s initial outline:

Literature as argument

Causal Argument/Historical data: marks studies that see literature as an agent of historical change along the lines of something a historian of the period can recognize.

Alternate Explanation: notes studies that see literary writers as rival social theorists whose arguments warrant proper countering.

Philosophical Position: refers to studies that associate an author with an argument that is developed or sustained across that author’s body of work.

Literature as context

Historical Context: designates studies that use information from literary texts as a way of characterizing a particular historical period, without claiming that the work was an agent of change in the period.

Biography: refers to studies that cite biographical details of an author or literary source as a way of situating concurrent historical events.

Literature as metonym

Cultural Standard: names studies that refer to literary texts as a cultural metonym, for example using Shakespeare as a way of referring to Renaissance England or to Western Culture as a whole.

Parable: designates studies that refer to a literary object that has lost its original literary contextualization and now stands in for something else entirely (e.g., Robinson Crusoe as a parable for homo economicus).

Literature as decoration

Literary effects/style: accounts for those literary texts that are evoked subtly via an author’s style or phrasing.

Decoration: names instances when the references to a literary text appear merely decorative and play no significant role in the argument.

Nonfiction quote: denotes direction quotations attributed to authors outside their published works.

Literature as Inspiration: marks moments in which a literary text plays no direct role in the argument but inspired the scholar’s thinking.

Literature as Teaching Tool: acknowledges instances where scholars use literary texts within the classroom or to help explain a concept.

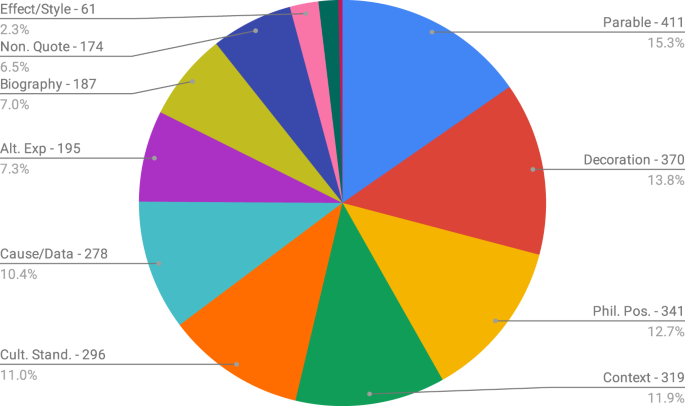

As this expanded typology suggests, our initial assessment of the JSTOR articles highlights literature’s wide range of applications within the social sciences (Fig. 2 ). Moreover, it jumpstarts a dialog on what, exactly, constitutes a use of literature within this field. After all, it seems significant that a great portion of literary references as captured in the JSTOR survey are essentially non-critical uses—pithy quotations from authors or famous literary epigrams—when viewed from the perspective of literary studies. Nonetheless, to account for these references to literature is to acknowledge something of the role literary fiction per se plays, if not in the entire field of social science research, then in the academic conventions of social science publishing.

Chart shows the proportion of literary typographies across JSTOR’s social science catalog from among our compiled search term list. The presented types originate from our expanded typography based on Watts’s categorisations.

At the same time, our attempts to expand this typology ran into several hurdles of its own. First and foremost, our ability to generate search results from the JSTOR archive was limited by the terms we used: because any search for “literature” or “fiction” produces too many non-applicable and generalized results, one must enter specific search terms (e.g., William Shakespeare; Virginia Woolf) to produce relevant results. Along similar lines, our typology can only take shape in view of these limited sources; it is after all possible that an author or literary text that did not appear on our initial list has been received by social scientists in ways that confound expectations beyond even our expanded typology.

Finally, our reliance on both pre-conceived search terms and archived research articles prevents us from evaluating the newest trends in both literature as well as social science research. As our survey results below demonstrate, there is ample evidence that literature produced within the last twenty years has an outsized impact on those social scientists who acknowledge literary fiction as an influence in their work. The conventions of academic publishing in non-literary fields, however, might prevent researchers from likewise acknowledging these contemporary examples in their published material in favor of more familiar, canonical examples. In view of the affordances and limitations to our initial JSTOR study, we decided to approach the subject of literature and social science from another direction: by going directly to the source.

If publications are the end products of academic work, the product does not always reflect all details of the research process. Nobody leaves the scaffolding standing when the house is completed; likewise, the notes, readings, and other sources of inspiration that lay the foundation for an article or academic monograph often go unacknowledged. To be sure, simply searching for references to literary fiction in the published text of these sources is likely to return some results—for instance, the frequent conflation of the homo economicus model with the protagonist of Robinson Crusoe, albeit in a manner that elides any reference to Daniel Defoe, the author (Watson, 2017 ). As the example of Crusoe suggests, the small pool of literary sources that appear in the text of social science articles cannot adequately account for the wide range of influences literature might have at all stages of research. To better capture these invisible or unacknowledged uses of literature in the social science, we decided to simply ask social scientists themselves. The survey asked a few simple questions on their use (or not) of fictional literature in any stage of their academic work. The survey questions are included in the supplementary material as supplementary note . We received 875 responses at a response rate of 7 percent, a number which we deemed acceptable for allowing us to detect some overall patterns. Given the use of THE rankings, the sample is dominated by North American and European social science departments. The sample includes all career stages: Ph.D students (35 pct.), postdocs and assistant professors (20 pct.), and tenured staff (42 pct.). It includes the four major social science disciplines: economics (20 pct.), sociology (31 pct.), political science (26 pct.), psychology (19 pct.), whereas a small group (4 pct.) identified with other disciplines. A full demographic breakdown (Table S.1) is included in the supplementary material .

Discussion: what do social scientists say?

To be clear, not all social scientists use literature in a manner conforming with our typology above or even consider literature a factor in their work life. In the survey, we focused on the non-explicit uses of literature and the considerations behind their uses. In other words, the survey is meant to supplement our findings from the study of social science journals from the JSTOR digital library. The survey should not be taken as a test of the above-mentioned categories developed from the empirical study of academic publications. Still, it is possible to glean some points of overlap between the two approaches. Several of these categories can be easily applied to responses from the survey, especially the categories relating to literature’s inspirational value or its usefulness as a teaching tool. At the same time, other categories that feature heavily in the published articles—especially “literature as decoration” and “literature as metonym”—were hardly mentioned at all in the survey responses. The gap between what social scientists say about literature and what appears in social science articles reiterates the value of the survey, which captures some of the underlying motivations for using literature (or not) that otherwise would not come across in view of published academic work.

Even considering the general self-selection bias—i.e., respondents who react positively to the idea of using literature are also more likely to participate in the survey—93 percent agreed that “Literature often contains important insights into the nature of society and social life”, while only 2 percent disagreed. However, it is one thing to acknowledge that literature offers general insights into life and quite another to affirm that literature plays a role in individual research biographies. To address this issue, we posed the question if “Reading literature played a role in the formation of your research questions or the development of your research projects.”

We were somewhat surprised to learn that this was the case for almost half of the respondents (46 precent agree or totally agree), and only a third (34 percent) rejected this premise (Table 1 ). Looking at the comments in the open sections shed light on this. For some researchers there was a very clear link. For example, one respondent explained: “Toni Morrison and other women of color (Ana Castillo, for example) greatly enriched my understanding of the role of gender in society (I am a man).”

Raising the bar even higher, we then asked about publications. Publications are arguably the most delicate matter in our survey. After all, publications can make or break careers inasmuch as they factor into promotions and tenure reviews. In response to our publishing question (“How often do you quote or in other ways use a work of fiction in your publications”), 25 percent recorded occasionally using literary fiction in some form and an additional 13 percent affirmed doing so often or very often. In other words, almost 40 percent of the respondents acknowledge using literary sources in their publications (Table 2 ).

However, it must be stressed that these uses vary in form and substance. Based on our qualitative assessment of a subset of social science sources (outlined above), we found that explicit engagements range from the superficial (e.g., brief quotations of famous quips or observations from literary sources), the decontextualized (e.g., Robinson Crusoe functions only as a model of economic behavior), to more sustained engagements with the arguments or ideas presented in literature (e.g., Thomas Piketty’s references to Jane Austen and Balzac in Capital in the Twenty-First Century). In other words, a great many of these applications of literature do not resemble the type of work one finds in literature departments. Moreover, the depth or method for engagement is rather unsystematic.

Of course, publications and research only constitute part of the work academics do at the university. Our survey also asked about teaching in order to capture other literary uses that published papers are unlikely to acknowledge. As noted above, Robinson Crusoe appears in textbooks on microeconomics in the figure of the homo economicus. Elsewhere, there are several examples of sources who call for incorporating literary fiction in the teaching of the social sciences in order to benefit from the imaginative social logics embedded in, for instance, science fiction novels (e.g., Rodgers et al., 2007 ; Hirschman et al., 2018 ). As our survey demonstrates, most of the respondents use or have used literary sources as pedagogical tools: less than a third (30 percent) never do so, most do so at least sometimes, and a few (12 percent) frequently use literature in their teaching (Table 3 ).

If we had expanded the category from literature to art in a wide sense (including, for example, movies, television series, paintings, and music) we suspect the numbers would have been significantly higher.

Finally, our survey provides some insight into what characterizes social scientists who use literature in their work. We generally find only small differences between disciplines within the field of social science, with economists marginally more skeptical of literature’s usefulness in the classroom than researchers in sociology, political science, and psychology (Table 3 ). This confirms earlier findings. A survey from 2006 showed that 57 percent of economist disagreed with the proposition that “In general, interdisciplinary knowledge is better than knowledge obtained by a single discipline.” For psychology, political science, and sociology the numbers were 9, 25 and 28 percent respectively (Fourcade et al., 2015 ).

Larger contrasts appear when considering the career stage of the researchers. We find a very clear general pattern of early-career, non-tenured researchers expressing more skepticism regarding literature’s insights compared to tenured and more senior researchers (Table 4 ). This pattern is most apparent when the respondents consider the use of literature in their own publications. A striking 75 percent of PhD students and 78 percent of postdocs have never quoted literature in their publications, compared to 48 percent in the senior professor group.

Arguably, this gap might simply reflect the much larger publication portfolio expected of senior professors in relation to early-career scholars, but the same pattern holds when we asked more general questions on the importance of literature.

This last point casts into relief some of the internal and generational gaps existing between senior researchers and junior and early-career researchers facing an increasingly precarious academic workplace. For early-career researchers, there is little immediate benefit to working outside established borders when recognition and professional assessment (such as promotions and tenure) still largely derive from work within disciplinary camps (Lyall, 2019 , p. 2). At the same time, stepping into uncharted territory requires one to navigate disciplinary traditions, departmental gatekeeping, and new methodologies. These professional limitations are what observers have in mind when they call interdisciplinary research risky at best (e.g., Callard and Fitzgerald, 2015 ) and “career suicide” at worst (Bothwell, 2016 ).

Rather than ascribing literary interests to some form of academic maturity, then, we suspect this gap between early and later-stage researchers partly reflects how disciplines work. In general terms, it is easy to imagine how the institutional pressures on early-career researchers can translate to a stricter adherence to disciplinary guidelines. Facing an unstable job market and competing for a limited pool of external funding, these scholars are highly dependent on the recognition of their peers and will tend to be more risk-adverse with respect to publications. As noted above, explicit signals of inter- or cross-disciplinary interests may sound appealing in the abstract (and may be promoted by international funding agencies) but they face much more skepticism within academic departments and hiring committees. As a result, using literature in academic publications—and perhaps explicitly cross-disciplinary research in general—is a luxury that only the more professionally-secure researchers can afford.

This explanation might account for the lack of explicit references to literary fiction in social science research, but not the absence of more indirect literature-research relationships. For example, 39 percent of PhD students “totally agree” that one can “learn a lot about what humans are like from literature” as opposed to 60 percent of associate professors and over half of professors. While outside the bounds of our current project, this generational gap may also be evidence of the diminishing presence of literature departments on university campuses after successive years of administrative funding cuts and public pressure against humanities-oriented education in general (Meranze, 2015 ). Fewer literature classes may result in as scenario where even advanced degree holders in an adjacent field like social science may be less studied in literature than their more senior colleagues.

What is the social scientist reading list?

There is no shortage of arguments for those in the social sciences to read literary fiction. As noted in the introduction above, there are a handful of social scientists in fields like sociology and economics who emphasize not only the general value of reading literature but also the profound insights literature can offer their research. However, beyond acknowledging the need to read in general, the question remains: which books to open, and which pages to turn? As is perhaps unsurprising canonical examples of realist fiction, with their aspiration to represent the breadth of the social world, are often the first to come to mind. Critics interested in bridging the gap between literature and economics, for instance, tend to hold up nineteenth-century novels as key examples of the relevant insight fiction might offer (Fessenbecker and Yazell, 2021 ). This preference for major classics was also confirmed by the participants in our survey, who cited such canonical novelists as George Orwell and Leo Tolstoy with high frequency (Table 5 ). The full list of literary recommendations for “understanding society better” includes novels and authors and spans different national literary canons, with authors associated with novels far eclipsing other forms of literature.

The above list of frequently referenced authors comes with few surprises. Anglophone—and especially US—literature and writers dominate, which reflects of the high number of US and UK universities on our list of top departments in the field of social science. All authors except Homer, Shakespeare, Dostoyevsky, Austen, Eliot, and Twain belong to the twentieth century. The most contemporary authors are women—Adichie and Atwood the only living authors within the top twenty—in contrast to the heavily-canonized, uniformly male authors in the top five positions. These more recent authors to different degrees push back against the conventions of the realist novel. Atwood’s speculative fiction and the fantasy and utopian fiction of LeGuin thus demonstrate the range of novelistic genres cited in the survey responses.

The list also suggests something of the formative power of the standardized literature curriculum. Books typically assigned in US high schools are heavily represented on the list of recommended texts below, which includes The Grapes of Wrath and To Kill a Mockingbird (Table 6 ). The uncontested most recommended read for social scientists is the British novelist and essayist George Orwell. The specific recommendations include his most best-selling books, 1984 and Animal Farm, which together form the two most recommended titles according to the survey respondents.

Conclusion: the uses of trivia

To briefly summarize, we set out to study the way social scientists use literature in two broad ways. First, we compiled a dataset comprising a century’s worth of scholarship in the social sciences. Second, we conducted a survey of a large number of contemporary working social scientists. A qualitative review of the dataset revealed a number of different ways social scientists have used literature; these uses were categorizable into six broad categories, several of which contained discernible sub-categories. The survey reinforced parts of this analysis while diverging in intriguing ways. Almost all the surveyed social scientists agreed on the cognitive value of literature, and almost half (46%) reported that literary works had played important roles in their own intellectual biographies. Yet some common uses of literature in the dataset received virtually no mention in the self-reports and the survey revealed suggestive evidence of the impact of institutional structures on whether and how scholars use literature. Ultimately the analysis points towards the value of further research. Both the list of uses compiled from the dataset and the list of works compiled from the survey are necessarily limited in scope and would benefit from a more comprehensive consideration of social scientists and their research.

But by way of conclusion, it is worth responding to the worry that much of the data collected here is somewhat less than consequential—the collection of an offhand reference here, a novel read in grad school there—and to that extent cannot answer our opening question about the nature of interdisciplinarity. Or, perhaps more soberly, it does answer the question, but simply in the negative. There is in fact not much of a meaningful use for literature in the conduct of the social sciences, and one of the pieces of evidence for the argument is the limited use such scholars have made of it thus far. Such an objection is wrong in two ways, one rather boring and one relatively more interesting. The boring objection is simply the observation that the history of a discipline does not predict its future: it would not be at all surprising to see a discipline change as a new archive of material or a new method of analysis became available to it. Indeed, this is often precisely what leads disciplines forward. The more interesting objection is the implicit premise that interdisciplinary scholarship must make its interdisciplinarity overt and extensive, and that a new interdisciplinary connection must be innovative.

We reject both halves of this second premise. The kind of interdisciplinarity we have traced here is light and casual, using a quotation here or there, and there is little that is new about it: it has been with the social sciences for much of their history. However, interdisciplinarity need not be utterly novel to be worth explicating, theorizing, and defending. Against the model of interdisciplinary development that considers the key question to be the difficulty and complexity of bringing two disciplines together, we want to highlight how easy it really is. If it were to become ordinary practice to read a novel and a piece of literary criticism that addressed whatever issue a given social scientist happened to be working on, this would for many social scientists simply normalize and bring to awareness the way they already work. Moreover, rather than shaming social scientists for not using literature more, we submit a better way to evoke greater respect for and greater use of literature and criticism is to highlight the ways in which they already do. Carrots, as they say, rather than sticks.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The JSTOR search terms did not include John Steinbeck, who is heavily cited by the respondents in our later survey. The omission, while regrettable, underscores the usefulness of the survey’s open-ended questions. Further research might well consider additional authors beyond this improvised list.

Arnold M (1873) Literature and dogma. Smith, Elder, and Co., London

Google Scholar

Bothwell E (2016) Multidisciplinary research ‘career suicide’ for junior academics. Times Higher Education, May 3

Callard F, Fitzgerald D (2015) Rethinking interdisciplinarity across the social sciences and neurosciences. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Book Google Scholar

Fessenbecker P, Yazell B (2021) Literature, economics, and a turn to content. The Minnesota review 96:69–81

Fourcade M, Ollion E, Algan Y (2015) The superiority of economists. J Econ Perspect 29(1):89–114

Article Google Scholar

Hirschman D, Schwadel P, Searle R, Deadman E, Naqvi I (2018) Why sociology needs science fiction. Contexts 17(3):12–21

Leavis FR (2011) The great tradition: George Eliot, Henry James, Joseph Conrad. Faber and Faber, New York, NY

Love H (2010) Close but not deep: literary ethics and the descriptive turn. New Lit Hist 41(2):371–391

Lyall C (2019) Being an interdisciplinary academic how institutions shape university careers. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Marcus S, Love H (2016) and Stephen Best. Building a better description. Representations 135(1):1–21

Martin CJ (2019) Imagine all the people: literature, society, and cross-national variation in education systems. World Polit 70(3):398–442

Meranze M (2015) Humanities out of joint. Am Hist Rev 120(4):1311–1326

Morson GS, Schapiro M (2017) Cents and sensibility: what economics can learn from the humanities. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Rodgers YV, Hawthorne S, Wheeler RC (2007) Teaching economics through children’s literature in the primary grades. Read Teach 61:46–55. https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.61.1.5

Shiller RJ (2019) Narrative economics: how stories go viral and drive major economic events. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Snow CP (1961) The two cultures and the scientific revolution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Watson M (2017) Rousseau’s Crusoe myth: the unlikely provenance of the neoclassical homo economicus. J Cult Econ 10(1):81–96

Watts M (2002) How economists use literature and drama. J Econ Educ 33(4):377–86

World University Rankings 2019 by subject: social sciences. (2019) Times Higher Education https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/2019/subject-ranking/social-sciences#!/page/0/length/25/sort_by/rank/sort_order/asc/cols/stats

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Rita Felski, Anne-Marie Mai, and Pieter Vanhuysse for their helpful feedback during the design of the survey. Thanks are also due to JSTOR for making available their digital archive and to the nearly 1000 colleagues who responded to the survey and, in some cases, provided additional comments by email. Research in this article received funding by the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF127) and the Danish Institute for Advanced Study (internal funds).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department for the Study of Culture, University of Southern Denmark, Odense M, Denmark

Bryan Yazell

Danish Institute for Advanced Study, Odense M, Denmark

Bryan Yazell & Klaus Petersen

Danish Centre for Welfare Studies, University of Southern Denmark, Odense M, Denmark

Klaus Petersen & Paul Marx

Institute for Socio-Economics, Universität Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany

Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), Bonn, Germany

Program for Cultures, Civilizations, and Ideas, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey

Patrick Fessenbecker

Engineering Communication Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Bryan Yazell .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The project design was approved by SDU-RIO (ref: 10.646). As the project does not involve human biological material, approval by the Research Ethics Committee SDU is not applicable.

Informed consent

Data collection for this study and the use of data for research were approved by SDU-RIO (ref: 10.646) following Danish Data Protection Law [databeskyttelsesforordningen] §10.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary material, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Yazell, B., Petersen, K., Marx, P. et al. The role of literary fiction in facilitating social science research. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8 , 261 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00939-y

Download citation

Received : 20 July 2021

Accepted : 12 October 2021

Published : 03 November 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00939-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

National Endowment for the Arts

- Grants for Arts Projects

- Challenge America

- Research Awards

- Partnership Agreement Grants

- Creative Writing

- Translation Projects

- Volunteer to be an NEA Panelist

- Manage Your Award

- Recent Grants

- Arts & Human Development Task Force

- Arts Education Partnership

- Blue Star Museums

- Citizens' Institute on Rural Design

- Creative Forces: NEA Military Healing Arts Network

- GSA's Art in Architecture

- Independent Film & Media Arts Field-Building Initiative

- Interagency Working Group on Arts, Health, & Civic Infrastructure

- International

- Mayors' Institute on City Design

- Musical Theater Songwriting Challenge

- National Folklife Network

NEA Big Read

- NEA Research Labs

Poetry Out Loud

- Save America's Treasures

- Shakespeare in American Communities

- Sound Health Network

- United We Stand

- American Artscape Magazine

- NEA Art Works Podcast

- National Endowment for the Arts Blog

- States and Regions

- Accessibility

- Arts & Artifacts Indemnity Program

- Arts and Health

- Arts Education

- Creative Placemaking

- Equity Action Plan

- Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs)

Literary Arts

- Native Arts and Culture

- NEA Jazz Masters Fellowships

- National Heritage Fellowships

- National Medal of Arts

- Press Releases

- Upcoming Events

- NEA Chair's Page

- Leadership and Staff

- What Is the NEA

- Publications

- National Endowment for the Arts on COVID-19

- Open Government

- Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

- Office of the Inspector General

- Civil Rights Office

- Appropriations History

- Make a Donation

Literary Arts inspire, enrich, educate, and entertain. They remind us that there is beauty and joy in language, that others have insights worth paying attention to, that in our struggles we are not alone. By helping writers and translators create new work and connect with audiences through publishers and other literary organizations and programs, the National Endowment for the Arts celebrates the literary arts as an essential reflection of our nation's rich diversity of voices.

Since the agency's beginnings in 1965, the Arts Endowment has awarded more than $125 million in direct grants to literary arts nonprofit organizations and more than $57 million to individual writers.

In addition to grants to organizations and fellowships to writers, the National Endowment for the Arts also engages the public with the literary arts through its initiatives Poetry Out Loud, a nationwide poetry recitation contest for high-schoolers, and NEA Big Read, innovative community reads around a single book, and its participation in the annual National Book Festival.

Literature Fellowships

The National Endowment for the Arts awards Literature Fellowship awards every year in creative writing and translation. These fellowships represent the agency's most direct investment in American creativity. The goal of the fellowships program is to encourage the production of new work and allow writers the time and means to write. Many recipients have gone on to receive the National Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle Award, and the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry and Fiction. Most received their fellowships before any major national award, usually at least a decade earlier.

The Literature Fellowships are the only competitive, non-nominated awards that the National Endowment for the Arts gives to individual artists. See a full list of all the fellowship awards that the agency has given.

Creative Writing Fellowships

Creative Writing Fellowships of $25,000 are awarded in alternating years in prose (fiction and creative nonfiction) and poetry, giving recipients the time and space to create, revise, conduct research, and connect with readers. The program is arguably the most egalitarian grant program in its field: applications are free and open to the public; fellows are selected through an anonymous review process in which the sole criterion is artistic excellence; and the judging panel is diverse and varies year to year. The Arts Endowment has awarded more than 3,700 Creative Writing Fellowships, resulting in many of the most acclaimed novels of contemporary literature: Jeffrey Eugenides's Middlesex , Oscar Hijuelos's The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love , Alice Walker's The Color Purple , William Kennedy's Ironweed , and Bobbie Ann Mason's In Country .

You can meet some of the fellows who received creative writing awards from 2001 to the present.

Translation Fellowships

Translation Fellowships ranging from $10,000 to $20,000 are awarded to literary translators, giving recipients the time and space to create English renditions of the world’s best literature, making them accessible to American audiences. Since 1981, the Arts Endowment has awarded 590 fellowships to 518 translators, with translations representing 80 languages and 90 countries, such as Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 , translated by Natasha Wimmer, and Nobel Prize-winner Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights , translated by Jennifer Croft.

You can meet some of the fellows who received translation awards from 2011 to the present.

And check out the Arts Endowment publication The Art of Empathy: Celebration Literature in Translation containing 19 thought-provoking essays by award-winning translators and publishers on the art of translation and its ability to help us understand other cultures and ways of thought.

Initiatives

A partnership of the National Endowment for the Arts, the Poetry Foundation, and the state arts agencies, Poetry Out Loud is a national arts education program that encourages the study of great poetry. Since the program began in 2005, more than 4 million students and 65,000 teachers from 16,000 schools across the country have participated in Poetry Out Loud.

A new research report, Line by Line: Transforming Student Lives and Learning with the Art of Poetry , presents findings from an evaluation of Poetry Out Loud that involves data collection from ten sample schools assessing the program’s impact on poetry appreciation and engagement, social and emotional development, and academic performance. Among the findings:

- Participating POL students were 1.7 times more likely to have 4-year college or graduate school aspirations than nonparticipants, even after researchers controlled for other factors.

- POL students were 1.5 times more likely than non-POL participants to engage in community service and volunteering, even after researchers controlled for other factors.

- POL gave students an opportunity to grapple with their positive and negative feelings toward poetry. Through multiple modes of engagement, students learned a wide variety of ways to connect with poems—and with each other.

The National Endowment for the Arts Big Read, a partnership with Arts Midwest, broadens our understanding of our world, our communities, and ourselves through the joy of sharing a good book. Showcasing a diverse range of titles that reflect many different voices and perspectives, the NEA Big Read aims to inspire conversation and discovery.

Studies show that reading for pleasure reduces stress, heightens empathy, improves students' test scores, slows the onset of dementia, and makes us more active and aware citizens. Book clubs and community reading programs extend these benefits by creating opportunities to explore together the issues that are relevant to our lives. Wrote one NEA Big Read participant, echoing the sentiments of many other participants around the country, "the book taught us how to talk to and trust one another so that we could ultimately approach issues that were difficult and immediate."

Since 2006, the National Endowment for the Arts has funded more than 1,600 NEA Big Read programs, with activities having reached every Congressional district in the country. Over the past 14 years, grantees have leveraged more than $50 million in local funding to support their NEA Big Read programs. More than 5.7 million Americans have attended an NEA Big Read event, approximately 91,000 volunteers have participated at the local level, and over 39,000 community organizations have partnered to make NEA Big Read activities possible.

National Book Festival

Every year since 2001, the National Endowment for the Arts has participated in the National Book Festival held by the Library of Congress in Washington, DC. First on the Library of Congress grounds and then on the National Mall before moving to the Washington Convention Center, the festival brings together hundreds of thousands of book lovers to hear authors read their work, participate in discussions, sign books, and more. It is one of the most prominent literary events in the nation. The Arts Endowment has sponsored a Poetry & Prose stage annually to focus attention on some of the nation’s finest literary writers—many of whom are National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellows.

In 2020, the festival took place virtually due to the pandemic. The Arts Endowment Poetry & Prose stage featured Literature Fellows such as Tracy K. Smith, Sandra Cisneros, Robert Pinsky, Rita Dove, Joy Harjo, Mark Doty, Danez Smith, Elizabeth Tallent, and Juan Felipe Herrera, as well as a segment on the agency’s Poetry Out Loud program.

Maps to the Next World

Led by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center (APAC) in collaboration with the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the Poetry Foundation, Maps to the Next World is a new digital publishing initiative that seeks to chart new paths forward for the literary arts field. Through a series of commissioned essays published online in a range of journals and linked to APAC’s website, Maps to the Next World seeks to inspire wide-ranging reflections on challenges facing the many sectors of the literary arts and the role the field plays in public life. The initiative will provide a forum for bold ideas and actionable steps towards a more just, accessible, and financially viable literary arts ecosystem.

Maps to the Next World draws its title from the poem “A Map to the Next World” by former US Poet Laureate and NEA Creative Writing Fellow Joy Harjo. The commissioned pieces by both established and emerging writers will range in length, style, form, and perspective. They will engage with topics relevant to a wide range of individuals, organizations, coalitions, and communities within the literary arts, including stakeholders such as writers and translators, teaching artists and book reviewers, literary journals and small presses, reading series and writing workshops.

Literary Arts Podcasts

Suzan-Lori Parks

Kirsten Cappy

Revisiting Danielle Evans

Literary arts blog posts.

National Poetry Month Spotlight: Zoeglossia

Love Poems by NEA Literature Fellows

Notable Quotable: Poet Huascar Medina

Stay connected to the national endowment for the arts.

Arts-Based Research

- First Online: 29 September 2022

Cite this chapter

- Robert E. White ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8045-164X 3 &

- Karyn Cooper 4

1155 Accesses

In its purest form, art may be simultaneously immediate and eternal: immediate in its ability to grasp one’s attention, to provoke or inspire; eternal in its ability to create deep and permanent impressions. Responses to art may be visceral, emotional or psychological by turns or even together. As such, a work of art may possess almost unlimited potential to educate (Leavy, 2017). Although a pursuit of matters artistic may be a worthy pursuit for its own sake, the arts also represent invaluable opportunities across all research disciplines. As such, arts-based research exists at intersections between art and science. According to McNiff ( 2008 ), both arts-based research and science involve the use of systematic experimentation with the goal of gaining knowledge about life.

Aristotle once said or, at least, was said to have said, man by nature seeks to know. Research, in the broadest sense, is an effort to know and I believe that the forms of knowing vary enormously…. – Elliot Eisner, Stanford Graduate School of Education

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Barone, T. (2001). Touching eternity: The enduring outcomes of teaching . Teachers College Press.

Google Scholar

Barone, T., & Eisner, E. W. (1997). Arts-based educational research. In R. M. Jaeger (Ed.), Complementary methods for research in education (pp. 95–109). American Educational Research Association.

Barone, T., & Eisner, E. W. (2012). Arts-based research . Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Behar, R. (2007). Ethnography in a time of blurred genres. Anthropology & Humanism, 32 (2), 145–155.

Article Google Scholar

Cahnmann-Taylor, M. (2008). Arts-based research: Histories and new directions. In M. Cahnmann-Taylor & R. Siegesmund (Eds.), Arts-based research in education: Foundations for practice (pp. 3–15). Routledge.

Chilton, G., Gerber, N. & Scotti, V. (2015). Towards an aesthetic intersubjective paradigm for arts based research: An art therapy perspective. Critical Approaches to Arts-based Research, 5 (1), 1–27. Retrieved December 24, 2018, from; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308971008_Towards_an_aesthetic_intersubjective_paradigm_for_arts_based_research_An_art_therapy_perspective

Chilton, G., & Leavy, P. (2014). Arts-based research practice: Merging social research and the creative arts. In P. Leavy (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of qualitative research (pp. 403–422). Oxford University Press.

Cole, A., & Knowles, J. G. (2008). Arts-informed research. In J. G. Knowles & A. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 55–70). Sage.

Chapter Google Scholar

Cooper, K., & White, R. E. (2012). Qualitative research in the postmodern era: Contexts of qualitative research. Springer.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2008). The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials, Volume 4 (pp. 1–42). Sage.

Eisner, E. W. (1991). The enlightened eye: Qualitative inquiry and the enhancement of educational practice . Merrill.

Eisner, E. W. (1993). Forms of understanding and the future of educational research. Educational Researcher, 22 (7), 5–11.

Eisner, E. W. (2002). The arts and the creation of mind . Yale University Press.

Eisner, E. W. (2008). Art and knowledge. In J. G. Knowles & A. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research (pp. 3–12). Sage.

Eliot, T. S. (1961). The love song of J. Alfred Prufrock. In M. Mack, L. Dean, & W. Frost (Eds.), Modern poetry (Vol. VII, 2nd ed., pp. 130–134). Prentice-Hall.

Finley, S. (2005). Arts-based inquiry: Performing revolutionary pedagogy. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 681–694). Sage.

Finley, S. (2008). Arts-based research. In J. G. Knowles & A. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 71–82). Sage.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of culture: Selected essays . Basic Books.

Geertz, C. (1988). Works and lives: The anthropologist as author . Polity Press.

Gerber, A. S. (2012). Field experiments: Design, analysis and interpretation . W. W. Norton.

Gray, C. (1996). Inquiry through practice: Developing appropriate research strategies . Retrieved, December 27, 2018, from: http://carolegray.net/Papers%20PDFs/ngnm.pdf

Greene, M. (1993). Diversity and inclusion: Toward a curriculum for human beings. Teachers College Record, 95 (2), 211–221.

Hesse, H. (2002). The glass bead game/Das Glasperlenspiel . Picador Books.

Irwin, R. L. (2014). Turning to a/r/tography. KOSEA Journal, 15 (1), 1–40.

Irwin, R. L., Beer, R., Springgay, S., Grauer, K., & Xiong, G. (2006). The rhizomatic relations of A/R/Tography. Studies in Art Education, 48 (1), 70–88.

Irwin, R. L., & de Cosson, A. (2004). A/R/Tography: Rendering oneself through arts-based living inquiry . Pacific Educational Press.

Irwin, R. L., & Springgay, S. (2008). A/r/tography as practice-based research. In S. Springgay, R. L. Irwin, C. Leggo, & P. Gouzouasis (Eds.), Being with A/r/tography (pp. xix–xxxiii). Sense Publishers.

Knowles, J. G., & Promislow, S. (2008). Using an arts methodology to create a thesis or dissertation. In J. G. Knowles & A. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 511–526). Sage.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (2003). Metaphors we live by . Chicago University Press.

Leavy, P. (2015). Method meets art: Arts-based research practice (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Leavy, P. (2017). Introduction to arts-based research. In P. Leavy (Ed.), Handbook of arts-based research (pp. 3–22). The Guilford Press.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2017). Creative arts therapies and arts-based research. In P. Leavy (Ed.), Handbook of arts-based research (pp. 68–87). The Guilford Press.

McNiff, S. (2005). Foreword. In D. Kalmanowitz, B. Lloyd, & S. McNiff (Eds.), Art therapy and political violence: With art, without illusion (pp. xii–xvi). Routledge.

McNiff, S. (2008). Art-based research. In J. G. Knowles & A. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 29–40). Sage.

McNiff, S. (2009). Cross-cultural psychotherapy and art. Art Therapy, 26 (3), 100–106.

McNiff, S. (2015). Imagination in action: Secrets for unleashing creative expression . Shambala Publications.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception . Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Nyasulu, E. (2019) Eisner’s connoisseurship model . Retrieved November 6, 2018 from: https://www.academia.edu/23230956/Eisners_Connoisseurship_Model

O’Toole, J., & Beckett, D. (2010). Educational research: Creative thinking & doing . Oxford University Press.

Polkinghorne, D. (1988). Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences . State University of New York.

Saldaña, J. (2011). Fundamentals of qualitative research . Oxford University Press.

Saldaña, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers . Sage.

Savin-Baden, M., & Major, C. H. (2012). Qualitative research: The essential guide to theory and practice . Routledge.

Savin-Baden, M., & Wimpenny, K. (2014). A practical guide to arts-related research . Sense.

Schratz, M., & Walker, R. (1995). Research as social change: New opportunities for qualitative research . Routledge.

Simons, H., & McCormack, B. (2007). Integrating arts-based Inquiry in evaluation methodology: Opportunities and challenges. Qualitative Inquiry, 13 (2), 292–311.

Sinner, A., Leggo, C., Irwin, R., Gouzouasis, P., & Grauer, K. (2006). Art-based educational research dissertations: Reviewing the practices of new scholars. Canadian Journal of Education, 29 (4), 1223–1270.

Springgay, S., Irwin, R. L., & Kind, S. (2005). A/r/tography as living inquiry through art and text. Qualitative Inquiry, 11 (6), 897–912.

Sullivan, G. (2006). Research acts in art practice. Studies in Art Education, 48 (1), 19–35.

Suppes, P., Han, B., & Lu, Z.-L. (1998). Brain-wave recognition of sentences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 95 (26), 15861–15866.

Tierney, W. G. (1999). Guest editor’s introduction: Writing life’s history. Qualitative Inquiry, 5 (3), 307–312.

Turner, M. (1996). The literary mind: Origins of thought and language . Oxford University Press.

Wang, Q., Coemans, S., Siegesmund, R., & Hannes, K. (2017). Arts-based methods in socially engaged research practice: A classification framework. Art Research International, 2 (2), 5–39.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education, St. Francis Xavier University, Antigonish, NS, Canada

Robert E. White

OISE, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Karyn Cooper

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Robert E. White .

Researching Creations: Applying Arts-Based Research to Bedouin Women’s Drawings

Ephrat Huss

Julie Cwikel

Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel

Huss, E. & Cwikel, J. (2005). Researching creations: Applying arts-based research to Bedouin women’s drawings. The International Journal of Qualitative Methods 4 (4), 44-62.

All problem solving has to cope with an overcoming of the fossilized shape … the discovery that squares are only one kind of shape among infinitely many. —Rudolf Arnheim, 1996, p. 35

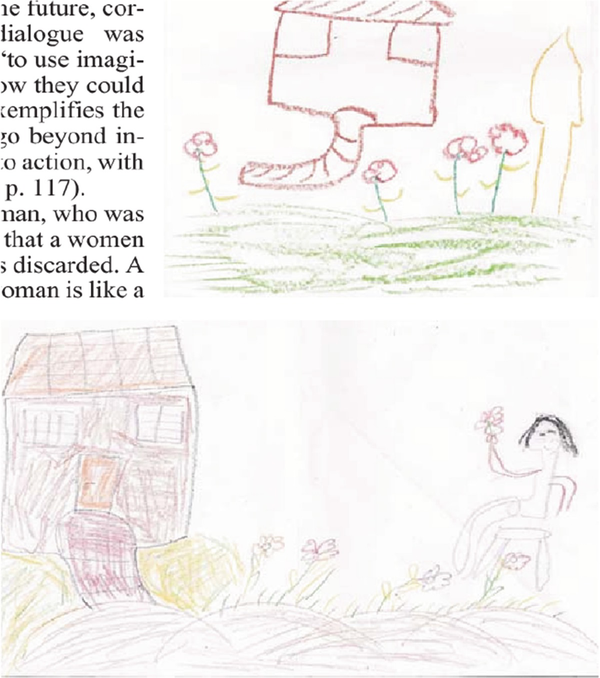

In this article, the author examines the combination of arts-based research and art therapy within Bedouin women ’ s empowerment groups. The art fulfills a double role within the group of both helping to illuminate the women ’ s self-defined concerns and goals, and simultaneously enriching and moving these goals forward. This creates a research tool that adheres to the feminist principles of finding new ways to learn from lower income women from a different culture, together with creating a research context that is of direct potential benefit and enrichment for the women. The author, through examples of the use of art within lower income Bedouin women ’ s groups, examines the theoretical connection between arts-based research and art therapy, two areas that often overlap but whose connection has not been addressed theoretically.

Keywords: art-based research, art therapy, researching women from a nondominant culture

Introduction: Why use the arts in research?

While I am talking with Bedouin women about their drawings, the tin hut in the desert that is the community center in which we work sometimes reverberates with lively stories and emotional closeness, and sometimes I, as a Jewish Israeli art therapist and researcher, and they, as a Bedouin Israeli women’s empowerment group, are lost to each other: When I suggest that we summarize the meaning of the art therapy sessions for the women, they nod their heads politely and thank me, and ignore my questions.

My aim in this article is to see how art-based research literature and art therapy literature can jointly contribute to both working with and understanding women from a different culture.

Art as communication (rather than as therapy) can be defined as the association between words, behavior, and drawing created in a group setting. McNiff (1995), a prominent art therapist and one of the pioneers of art-based research, suggested that art therapy research should move from justification (of art therapy) to creative inquiry into the roles of the art itself.

I will first review arts-based research in an effort to understand the use of art as research. I will then survey art therapy’s practice-based knowledge concerning working with art with women from a different culture, and third, I will apply both of these knowledge bases to Bedouin women’s drawings and words from within my case study.

Art as a form of inquiry

The aim in arts-based research is to use the arts as a method, a form of analysis, a subject, or all of the above, within qualitative research; as such, it falls under the heading of alternative forms of research gathering. It is used in education, social science, the humanities, and art therapy research. Within the qualitative literature, there is an “explosion” in arts-based forms of research (Mullen, 2003).

How does arts-based research help us to understand women from a different culture? It seems that classic verbal methods of interviewing or questionnaire answering are not effective forms of inquiry with these women. Bowler (1997) described the difficulties she found in using questionnaires and interviewing, both of which stress Western-style verbal articulation, as research methods with lower income Asian women. She found that the women try to give the “right” answer or to be polite. In-depth interviewing was also conceived of as a strange and foreign way of constructing and exploring the world for these women (Bowler, 1997; Lawler, 2002; Ried, 1993). The women are often mistakenly conceived of as “mute” because they do not verbalize information along Western lines of inquiry (Goldberger & Veroff, 1995).

The search for a method that “gives voice” to silenced women is a central concern for feminist methodologies. De-Vault (1999) analyzed Western discourse as constructed along male content areas and suggested that we “need to interview in ways that allow the exploration of un-articulated aspects of women’s experiences … and explore new methodologies” (p. 65). Using art as a way of initiating self-expression can be seen as such a methodological innovation.

The arts-based paradigm states that by handing over creativity (the contents of the research) and its interpretation (an explanation of the contents) to the research participant, the participant is empowered, the relationship between researcher and research participant is intensified and made more equal, and the contents are more culturally exact and explicit, using emotional as well as cognitive ways of knowing. Mason (2002) and Sclater (2003) have suggested that drawing or storytelling, or the use of vignettes or pictures as a trigger within an interview, already common in work with children, could also help adults connect ideological abstractions to specific situations, using both personal and collective elements of cultural experience.

Thus, culture and gender unite in making Western research methods insufficient for understanding women from a different culture. Using visual data-gathering methods, then, can be seen as a movement offering alternate avenues of self-expression for women from traditional cultures.

The arts are considered “soft,” female ways of knowing; they tend to be used as a counterpoint to the seriousness of words (Mason, 2002). Alternatively (and mistakenly), as in photography, arts are considered a depiction of absolute reality (Pink, 2001).

Silverman (2000) argued that research must access what people do, and not only what people say.

Art brings “doing” into the research situation. However, the inclusion of arts in research poses many methodological difficulties, described by Eisner (1997) in the title of his article as “The Promises and Perils of Alternative Research Gathering methods.” Denzin and Lincoln (1998) described personal experience methods as going “inwards and outwards, backwards and forwards” (p. 152). The art product by definition creates more “gaps” and entrances than closed statements or conclusions (this is what enables so many different people to connect to one picture!). The art process also includes moves between silences, times of doing, listening, talking, watching, thinking, and different gaps and connections between the above. For example, Mason (2002), a qualitative researcher, described how research participants agonize about where to put whom when drawing a genogram or family diagram. She claimed that this process of “agonizing,” or creating the genogram, is an important component of the finished genogram and should not be left out.

Issues in arts-based research

Sclater (2003) explored the above-described complications of defining the “contours” of art-based research, as difficulties in defining issues related to the quality of art, to the relationship with the research participant, and to the relationship between art and words in arts based research.

Defining issues related to the quality of art

Mullen (2003) concluded that art-based research is focused on process as expressing the context of lived situations rather than the final products disconnected from the context of its creation. Mahon (2000) argued, through the concept of embedded aesthetics, that the aesthetic product is not inherent from within but is always part of broader social contexts, which both transform and are transformed by the art product and around which there is always a power struggle over different cultural meanings (see also Barone, 2003). At the same time, Mahon claimed that art includes elements and aesthetic languages that are specific to itself and that cannot be translated into action research or communication, or understood as direct translations of social interactions. The boundaries of quality are seen as marginalizing whoever does not conform to them, as in folk, vernacular, and outsider forms of art. In art-based research, elitism is replaced by art as communication, whereby reactions to the art work are more important than the quality of the art in terms of external aesthetic criteria. Within this paradigm, the criteria of communication and social responsibility predominate over craftsmanship (Finley, 2003; Mullen, 2003; Sclater, 2003).

Defining issue related to the relationship with the research participant

Another consideration for arts-based research is the setting of standards or limits around the roles of artist, researcher, and facilitator of creative activities. Mullen (2003) suggested,

We need to find ways not just to represent others creatively, but to enable them to represent themselves. The challenge is to go beyond insightful texts, to move ourselves and others into action, with the effect of improving lives. (p. 117)

Therefore, multiple or blurred roles are advantageous, as they reflect the complexity of reality within any research situation. By handing over creativity and its interpretation to the research participant, and including these elements within the research, the relationship between researcher and research participant is intensified, eliciting emotion and facilitating transformation. Thus, the blurring of the contours or roles of the researcher and research participant is seen as advantageous.

For example, cameras were given to lower income rural Chinese women, who, through photography, were able to communicate their concerns to policy makers with whom they would not engage in a direct verbal confrontation (Wang & Burris, 1994).

Defining issues related to the relationship between art and words in arts-based research

Art-based research literature addresses the problematic issue of how to work with the relationship between the verbal and nonverbal elements of the data, the art form, and its interpretation within a research context. Within research, the theoretical framework of understanding a work of art is harnessed to the reason art was used within the research puzzle (Mason, 2002). The use of verbal and nonverbal elements can be seen as a triangulation of data. It is important to understand why we are including art and to think about how the use of visual contents will help solve the “puzzle” of the research (Davis & Srinivasan, 1994; Finley, 2003; Mason, 2002). Save and Nuutinen (2003) defined the relationship between drawing\ and words (after researching a dialogue between the alternate use of pictures and words) as “creating a field of many understandings, creating a ‘third thing’ that is sensory, multi-interpretive, intuitive, and ever-changing, avoiding the final seal of truth” (p. 532).

Connections between art therapy and arts-based research

Art therapy, or any therapy, aims to connect, integrate, and transform experience and behavior. Art-based research also aims to transform, in that it can “use the imagination not only to examine how things are, but also how they could be” (Mullen, 2003, p. 117). It aims to connect and empower by creating something together with the research participants rather than the classic research orientation that takes information away from them (Finley, 2003; Sclater, 2003).

Sarasema (2003), a qualitative researcher, discussed the therapeutic advantages of storytelling for widowed research participants, claiming that art-based research is a way of creating knowledge that “connects head to heart” (p. 603).