📕 Studying HQ

35+ research topics on mental health nursing: fostering wellbeing in psychiatric care, carla johnson.

- August 24, 2023

- Essay Topics and Ideas

Mental health nursing is a critical pillar in nurturing the overall wellness of individuals grappling with psychiatric conditions. Aspiring nursing students, comprehending the nuances of mental health nursing is not only pivotal for your academic voyage but also your future professional practice. In this comprehensive guide, we delve profoundly into mental health nursing. We will explore a range of PICOT questions, propose ideas for evidence-based practice (EBP) projects, furnish you with capstone project ideas, offer a spectrum of research paper topics, present a compilation of research questions, and provide several essay topic concepts. All these facets are intended to equip you holistically for this indispensable domain.

What You'll Learn

Understanding the Essence of Mental Health Nursing

Mental health nursing entails the compassionate care and unwavering support extended to individuals traversing the challenges of mental health issues. The role of a mental health nurse transcends the confines of conventional medical care , encompassing therapeutic communication, emotional bolstering, and fostering an environment conducive to healing. Mental health nurses operate in a myriad of settings including hospitals, community health centers, and outpatient clinics, playing an instrumental role in shaping the lives of their patients.

PICOT Questions on Mental Health Nursing

- Population (P): Adults under psychiatric care ; Intervention (I): Integration of daily RS questionnaire; Comparison (C): Units without daily survey; Outcome (O): Decreased employment of restraint and seclusion; Time (T): 6 months. How does the incorporation of a daily RS (Restraint and Seclusion) questionnaire for adults in psychiatric care, compared to units lacking this daily survey, impact the reduction in the utilization of restraint and seclusion for 6 months?

- P: Adolescents with depressive disorders ; I: Implementation of mindfulness-based intervention; C: Standard therapeutic approach; O: Mitigation of depressive symptoms; T: 8 weeks. Among adolescents diagnosed with depressive disorders, what is the effect of incorporating a mindfulness-based intervention, compared to standard therapy, on alleviating depressive symptoms over an 8-week period?

- P: Elderly residents in long-term care facilities; I: Deployment of pet therapy ; C: Absence of pet therapy; O: Enhancement of mood and social interaction; T: 3 months. In elderly individuals residing within long-term care facilities, does the introduction of pet therapy, as opposed to its absence, result in a noticeable improvement in mood and social interaction over a course of 3 months?

- P: Individuals grappling with schizophrenia ; I: Integration of family psychoeducation; C: Standard care regimen; O: Diminished recurrence rate of episodes; T: 1 year. For individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, does the inclusion of family psychoeducation within their treatment plan, when compared to standard care, lead to a reduction in the frequency of relapses over a 1-year period?

- P: Veterans afflicted with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); I: Employment of virtual reality exposure therapy; C: Conventional therapeutic methods; O: Reduction in symptoms of PTSD; T: 10 sessions. In veterans struggling with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), does the utilization of virtual reality exposure therapy result in a more pronounced reduction in PTSD symptoms, when contrasted with conventional therapy, across a span of 10 sessions?

- P: Children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD); I: Incorporation of equine-assisted therapy; C: Standard interventions; O: Amplification of social skills; T: 12 weeks. Among children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), does participation in equine-assisted therapy yield an advancement in social skills, in comparison to standard interventions, over a duration of 12 weeks?

- P: Inpatient populace with bipolar disorder ; I: Introduction of a mood tracking application; C: Conventional mood charting techniques; O: Attainment of superior mood stability; T: 6 months. Within inpatients diagnosed with bipolar disorder, does the utilization of a mood tracking application for monitoring moods contribute to enhanced mood stability in comparison to conventional mood charting over a span of 6 months?

- P: Individuals contending with eating disorders; I: Application of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT); C: Provision of supportive counseling; O: Reduction in maladaptive eating behaviors; T: 16 sessions. For individuals grappling with eating disorders, does the implementation of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) yield a more substantial reduction in maladaptive eating behaviors, when contrasted with supportive counseling, over 16 sessions?

- P: Patients undergoing substance abuse treatment; I: Integration of music therapy; C: Absence of music therapy; O: Mitigation of anxiety and cravings; T: 8 weeks. Among patients undergoing substance abuse treatment, does engagement in music therapy contribute to a reduction in anxiety and cravings, in comparison to those without exposure to music therapy, over a duration of 8 weeks?

- P: Senior residents of assisted living facilities; I: Implementation of reminiscence therapy; C: Participation in routine activities; O: Elevation in cognitive functioning; T: 3 months.

In senior individuals residing in assisted living facilities, does involvement in reminiscence therapy lead to an improvement in cognitive functioning when juxtaposed with engagement in routine activities across a span of 3 months?

5 EBP Projects on Mental Health Nursing

- Appraising the Efficacy of Art Therapy in Alleviating Anxiety Among Schizophrenia Patients.

- Probing the Influence of Exercise Interventions on Bipolar Disorder Patients’ Depressive Symptoms.

- Unpacking Aromatherapy’s Role in Managing Agitation Among Dementia Patients.

- Evaluating Peer Support Groups’ Contribution to Borderline Personality Disorder Recovery.

- Analyzing Virtual Support Networks’ Role in Mitigating Adolescent Social Anxiety Isolation.

Engaging Capstone Projects on Mental Health Nursing

- Forging a Mental Health Awareness Campaign to Combat Stigma Surrounding Help-Seeking in High Schools.

- Devising an Inclusive Training Module for Nurses Enhancing Communication with Psychosis Patients.

- Crafting a Manual to Empower Families in Supporting Loved Ones with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

- Establishing a Mindfulness Program for Psychiatric Hospital Personnel to Counter Burnout.

- Designing a Transitional Care Blueprint for Smooth Community Reintegration of Severe Mental Illness Patients Post-Hospitalization.

Research Paper Topics on Mental Health Nursing

- Examining the Role of Trauma-Informed Care in Enhancing Recovery for Domestic Violence Survivors with PTSD.

- Delving into the Nexus Between Childhood Trauma and the Emergence of Dissociative Identity Disorder.

- Surveying the Impact of Sleep Quality on College Students’ Mental Health : A Systematic Review.

- Assessing Telepsychiatry’s Efficacy in Extending Mental Health Services to Rural Regions.

- Navigating Cultural Competency in the Assessment and Treatment of Diverse Depression Patients.

Mental Health Nursing Research Questions

- How Does Early Intervention in Childhood Emotional Dysregulation Shape Mood Disorder Onset in Adulthood?

- What Are the Challenges to Adherence to Medication Among Schizophrenia Patients, and How Can Nursing Strategies Address Them?

- What Is the Impact of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Initiatives on Psychiatric Nurses’ Stress Levels?

- What Factors Contribute to the Overrepresentation of Marginalized Individuals with Coexisting Mental Illness in the Criminal Justice System?

- What Are the Long-Term Effects of Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) on Memory and Cognitive Function in Severe Depression Patients?

Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

- Ethical Conundrums in Administering Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT).

- Exploring the Nexus Between Trauma and Substance Abuse in Individuals with Dual Diagnoses.

- Nurses’ Role in Preventing Suicides: Assessing Risk and Providing Support.

- Cultural Proficiency in Mental Health Nursing: Catering to Multifaceted Patient Requirements.

- COVID-19’s Ripples on Healthcare Providers’ Mental Health: Coping Strategies Amid Challenges.

As you immerse yourself in the tapestry of mental health nursing, myriad opportunities unfold for your contributions to research, evidence-based practices, and compassionate patient care. These PICOT questions, EBP project suggestions, capstone project proposals, research paper topics, research questions, and essay themes constitute the foundation of your journey. Each endeavor you undertake to deepen your comprehension and skills in mental health nursing brings you closer to making a profound difference in the lives entrusted to your care. Should you need additional guidance when crafting essays, research papers, or any scholastic composition related to nursing and mental health, do not hesitate to seek professional aid. Our writing services are tailored to support your academic growth and triumph, ensuring your valuable contributions to mental health nursing are eloquently conveyed and impactful.

- What are the 4 principles of mental health nursing?

The four principles of mental health nursing are: therapeutic relationships, holistic care, patient-centeredness, and evidence-based practice. These principles guide nurses in providing comprehensive and effective care to individuals with mental health conditions.

- What is the role of a nurse in mental health treatment?

Nurses in mental health treatment play a pivotal role in assessing, planning, implementing, and evaluating care for patients with mental health issues. They provide therapeutic support, administer medications, conduct psychoeducation, and collaborate with the multidisciplinary team to promote recovery.

- What are the different types of mental health nurses?

Different types of mental health nurses include psychiatric-mental health nurses, advanced practice psychiatric nurses, child and adolescent mental health nurses, and geriatric mental health nurses. These specialized nurses cater to diverse patient populations and address specific mental health challenges.

- What are the 6 C’s in mental health nursing?

The 6 C’s in mental health nursing stand for Care, Compassion, Competence, Communication, Courage, and Commitment. These core values guide mental health nurses in delivering compassionate and effective care to individuals facing mental health issues.

Mental health nursing stands as a critical pillar in nurturing the overall wellness of individuals grappling with psychiatric conditions. Aspiring nursing students, comprehending the nuances of mental health nursing is not only pivotal for your academic voyage but also for your future professional practice. In this comprehensive guide, we delve profoundly into the realm of mental health nursing. We will explore a range of PICOT questions, propose ideas for evidence-based practice (EBP) projects, furnish you with capstone project ideas, offer a spectrum of research paper topics, present a compilation of research questions, and provide a plethora of essay topic concepts. All these facets are intended to equip you holistically for this indispensable domain.

Mental health nursing entails the compassionate care and unwavering support extended to individuals traversing the challenges of mental health issues. The role of a mental health nurse transcends the confines of conventional medical care, encompassing therapeutic communication, emotional bolstering, and fostering an environment conducive to healing. Mental health nurses operate in a myriad of settings including hospitals, community health centers, and outpatient clinics, playing an instrumental role in shaping the lives of their patients.

- Population (P): Adults under psychiatric care; Intervention (I): Integration of daily RS questionnaire; Comparison (C): Units without daily survey; Outcome (O): Decreased employment of restraint and seclusion; Time (T): 6 months. How does the incorporation of a daily RS (Restraint and Seclusion) questionnaire for adults in psychiatric care, compared to units lacking this daily survey, impact the reduction in the utilization of restraint and seclusion over a span of 6 months?

- P: Adolescents with depressive disorders; I: Implementation of mindfulness-based intervention; C: Standard therapeutic approach; O: Mitigation of depressive symptoms; T: 8 weeks. Among adolescents diagnosed with depressive disorders, what is the effect of incorporating a mindfulness-based intervention, in comparison to standard therapy, on the alleviation of depressive symptoms over an 8-week period?

- P: Elderly residents in long-term care facilities; I: Deployment of pet therapy; C: Absence of pet therapy; O: Enhancement of mood and social interaction; T: 3 months. In elderly individuals residing within long-term care facilities, does the introduction of pet therapy, as opposed to its absence, result in a noticeable improvement in mood and social interaction over a course of 3 months?

- P: Individuals grappling with schizophrenia; I: Integration of family psychoeducation; C: Standard care regimen; O: Diminished recurrence rate of episodes; T: 1 year. For individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, does the inclusion of family psychoeducation within their treatment plan, when compared to standard care, lead to a reduction in the frequency of relapses over a 1-year period?

- P: Inpatient populace with bipolar disorder; I: Introduction of a mood tracking application; C: Conventional mood charting techniques; O: Attainment of superior mood stability; T: 6 months. Within inpatients diagnosed with bipolar disorder, does the utilization of a mood tracking application for monitoring moods contribute to enhanced mood stability in comparison to conventional mood charting over a span of 6 months?

- Surveying the Impact of Sleep Quality on College Students’ Mental Health: A Systematic Review.

As you immerse yourself in the tapestry of mental health nursing, myriad opportunities unfold for your contributions to research, evidence-based practices, and compassionate patient care. These PICOT questions, EBP project suggestions, capstone project proposals, research paper topics, research questions, and essay themes constitute the foundation of your journey. Each endeavor you undertake to deepen your comprehension and skills in mental health nursing brings you closer to making a profound difference in the lives entrusted to your care. Should you find yourself in need of additional guidance when crafting essays, research papers, or any scholastic composition related to nursing and mental health, do not hesitate to seek professional aid. Our writing services are tailored to support your academic growth and triumph, ensuring your valuable contributions to the realm of mental health nursing are eloquently conveyed and impactful.

Start by filling this short order form order.studyinghq.com

And then follow the progressive flow.

Having an issue, chat with us here

Cathy, CS.

New Concept ? Let a subject expert write your paper for You

Have a subject expert write for you now, have a subject expert finish your paper for you, edit my paper for me, have an expert write your dissertation's chapter, popular topics.

Business StudyingHq Essay Topics and Ideas How to Guides Samples

- Nursing Solutions

- Study Guides

- Free Study Database for Essays

- Privacy Policy

- Writing Service

- Discounts / Offers

Study Hub:

- Studying Blog

- Topic Ideas

- How to Guides

- Business Studying

- Nursing Studying

- Literature and English Studying

Writing Tools

- Citation Generator

- Topic Generator

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Conclusion Maker

- Research Title Generator

- Thesis Statement Generator

- Summarizing Tool

- Terms and Conditions

- Confidentiality Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Refund and Revision Policy

Our samples and other types of content are meant for research and reference purposes only. We are strongly against plagiarism and academic dishonesty.

Contact Us:

📞 +15512677917

2012-2024 © studyinghq.com. All rights reserved

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 26 April 2019

Mental health nurses’ attitudes, experience, and knowledge regarding routine physical healthcare: systematic, integrative review of studies involving 7,549 nurses working in mental health settings

- Geoffrey L. Dickens ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8862-1527 1 , 2 ,

- Robin Ion 3 ,

- Cheryl Waters 1 ,

- Evan Atlantis 1 &

- Bronwyn Everett 1

BMC Nursing volume 18 , Article number: 16 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

57k Accesses

13 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

There has been a recent growth in research addressing mental health nurses’ routine physical healthcare knowledge and attitudes. We aimed to systematically review the empirical evidence about i) mental health nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and experiences of physical healthcare for mental health patients, and ii) the effectiveness of any interventions to improve these aspects of their work.

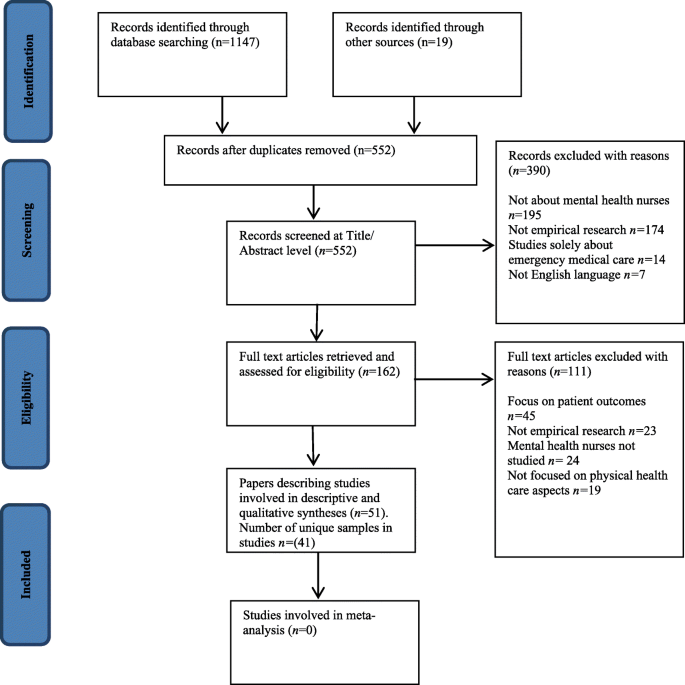

Systematic review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Multiple electronic databases were searched using comprehensive terms. Inclusion criteria: English language papers recounting empirical studies about: i) mental health nurses’ routine physical healthcare-related knowledge, skills, experience, attitudes, or training needs; and ii) the effectiveness of interventions to improve any outcome related to mental health nurses’ delivery of routine physical health care for mental health patients. Effect sizes from intervention studies were extracted or calculated where there was sufficient information. An integrative, narrative synthesis of study findings was conducted.

Fifty-one papers covering studies from 41 unique samples including 7549 mental health nurses in 14 countries met inclusion criteria. Forty-two (82.4%) papers were published since 2010. Eleven were intervention studies; 40 were cross-sectional. Observational and qualitative studies were generally of good quality and establish a baseline picture of the issue. Intervention studies were prone to bias due to lack of randomisation and control groups but produced some large effect sizes for targeted education innovations. Comparisons of international data from studies using the Physical Health Attitudes Scale for Mental Health Nursing revealed differences across the world which may have implications for different models of student nurse preparation.

Conclusions

Mental health nurses’ ability and increasing enthusiasm for routine physical healthcare has been highlighted in recent years. Contemporary literature provides a base for future research which must now concentrate on determining the effectiveness of nurse preparation for providing physical health care for people with mental disorder, determining the appropriate content for such preparation, and evaluating the effectiveness both in terms of nurse and patient- related outcomes. At the same time, developments are needed which are congruent with the needs and wants of patients.

Peer Review reports

People with a mental disorder diagnosis are at more than double the risk of all-cause mortality than the general population. Most at risk are those with psychosis, mood disorder and anxiety diagnoses. Median length of life lost by this group is 10.1 years greater for people with a diagnosis of mental disorder than for general population controls, but mortality rates are significantly higher in studies which include inpatients [ 1 ]. While risk of unnatural causes of death, notably suicide, are greatly increased in this group, it is death from natural causes that remains responsible for the vast majority of mortality. In people with schizophrenia, for example, cardiovascular disease accounts for about one third of all deaths and cancer for one in six, while other common causes are diabetes mellitus, COPD, influenza, and pneumonia [ 2 ]. A relatively high rate of tobacco smoking in this group is implicated in significant increased mortality [ 3 ], as is obesity [ 4 ], exposure to high levels of antipsychotic pharmacological treatment [ 5 ], and mental disorder itself [ 1 ].

Accordingly, the physical health of patients with mental disorder has been prioritised, becoming the focus of guidelines for practitioners in general [ 6 ] and for mental health nurses and other clinical professionals specifically [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. However, while policies and guidelines are necessary prerequisites of change they must also be implemented in practice if they are to have a positive effect; one of the key barriers to change implementation for mental health nurses has been identified as lack of confidence, skills, and knowledge [ 10 ]. Robson and Haddad ([ 11 ]: p.74) identified that surprisingly ‘modest attention’ had been paid to the issue of such attitudes and knowledge among nurses related to their role in physical health care provision, and developed the Physical Health Assessment Scale for mental health nurses (PHASe) in order to further investigate the phenomenon. Since then, there has been a tangible and growing response among mental health nursing academics and practitioners. In recent years, published literature reviews have covered a decade of UK-only research on the role of mental health nurses in physical health care [ 12 ], patients’ and professionals’ perceptions of barriers to physical health care for people with serious mental illness [ 13 ], the focus and content of nurse-provided physical healthcare for mental health patients [ 14 ], and the physical health of people with severe mental illness [ 15 ]. There has also been an upsurge in the amount of related empirical research. However, to date, no one has systematically reviewed this growing literature about mental health nurses’ attitudes towards, or their related knowledge and experience about providing routine physical healthcare. Further, studies about the effectiveness of interventions designed to improve their delivery of or attitudes to routine physical healthcare have not been systematically appraised. This is surprising given the known links between nurses’ attitudes and their implementation of evidence-based practice [ 16 , 17 , 18 ] and the centrality of measuring nurses’ attitudes to physical health care delivery in recent mental health nursing research on the topic [ 11 , 19 , 20 ].

In this context we have conducted a systematic review to identify, appraise, and synthesise existing evidence from empirical research literature about i) mental health nurses’ experience of providing physical healthcare for patients and about their related knowledge, skills, educational preparation, and attitudes; ii) the effectiveness of any interventions aimed at improving or changing mental health nurse-related outcomes; and iii) to identify implications for the future provision of relevant training and education, for policy, research, and practice. The specific review question being addressed therefore is: what is known from the international, English language, empirical literature about mental health nurses’ skills, knowledge, attitudes, and experiences regarding provision of physical healthcare.

A systematic review of the literature following the relevant points of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses [ 21 ].

Search strategy

Since the review scope encompassed questions about experience and effectiveness a dual literature search strategy was developed. For studies about mental health nurses’ experience of delivering physical healthcare a Population Exposure Outcome (PEO) format review question was developed (Population: mental health nurses; Exposure: physical healthcare provision for patients or related training; Outcomes: experiential, social, educational, knowledge, or attitudinal terms, see Additional file 1 : Table S1). For studies of the effectiveness of interventions to improve or change mental health nurse-related outcomes a Population Intervention Comparator Outcome (PICO) structure was implemented (Population: mental health nurses; Intervention: any intervention including physical health-related education, policy or guideline change; Comparator: any or none; Outcome: any) [ 22 ]. We searched five electronic databases: i) CINAHL, ii) PubMed, iii) MedLine, iv) Scopus, and v) ProQuest Dissertations and Theses using text words and MeSH terms. The references list of all included studies, together with those of relevant literature reviews, and the tables of contents of selected mental health nursing journals were hand searched. The search terms were informed by previous literature reviews on the subject of physical healthcare in mental health. The initial search was conducted in April 2018 and re-run in September 2018.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for studies were English language accounts of empirical research which investigated mental health nurses’ experience of providing physical health care or examined the effectiveness of any intervention that aimed to improve outcomes related to the provision of physical healthcare. Thus, studies of interventions aimed at changing nursing practice, behaviour, knowledge, attitudes, or experiences were eligible, but not those which solely attempted to determine the effect of an intervention on nurses in terms of patient outcomes. While improvement in patient care and outcomes is clearly the desirable endpoint of any intervention on nurses, previous reviews have indicated that no good quality studies exist [ 23 ]. Additionally, studies were only eligible for inclusion where the practitioners involved comprised or included mental health or psychiatric nurses or mental health nursing students, or registered nurses whose practice was within mental health services. Included studies could have used any design or methodological approach. As in previous reviews, studies solely about mental health nurses providing care for people with alcohol/ drug misuse, or mental disorder/substance misuse dual diagnosis were not eligible. Studies about mental health nurses and the provision of emergency physical care or of their experience of providing care for the seriously deteriorating physical health of a patient were omitted as this is the subject of a separate review (Dickens et al. submitted).

Data extraction

Information about the study title, author, publication year, data collection years, location (country), research objectives, aims or hypotheses, design, population, sample details and size, data sources, study variables (i.e. details of intervention) or other exposure, unit of analysis, and study findings were extracted from full text papers. Corresponding authors of included studies were contacted regarding any issues where clarification or additional data could aid the review.

Studies were categorised as interventional or observational. Intervention studies investigated the impact of an educational, policy, or practice intervention in terms of any mental health nurse- or nursing- related outcome, e.g., knowledge, attitudes, behaviour. Intervention studies were further sub-classified as simulation studies (as defined by Bland et al. ([ 24 ]: p.668) “a dynamic process involving the creation of a hypothetical opportunity that incorporates an authentic representation of reality, facilitates active student engagement and integrates the complexities of practical and theoretical learning with opportunity for repetition, feedback, evaluation and reflection”), traditional educational interventions (e.g., lectures, workshops, workbooks), or policy-level interventions (e.g., requiring nurses to follow some new policy or implement some new practice). Observational studies either described mental health nurse- or nursing- related outcomes and/or utilised case control designs to compare them with those of other occupational or professional groups and/or used qualitative methods.

Study quality appraisal

The likelihood of bias in intervention studies was assessed against criteria described by Thomas et al. [ 25 ] and encompassed assessment of the likelihood of selection bias in the obtained sample, study design, potential confounders, blinding, potential for bias in data collection from invalid instrumentation, and participant retention (see Additional file 2 : Table S2). Relevant items from the US Department of Health & Human Sciences NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies [ 26 ] were used to assess cross-sectional observational studies (see Additional file 3 : Table S3). Qualitative descriptive studies were assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme [ 27 ] tool (See Additional file 4 : Table S4). Multiple papers arising from single studies were quality assessed as a single entity. Study quality was initially undertaken independently by at least two of the team. A good level of inter-rater agreement was achieved (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.742 between pairs of raters). Disputed items were discussed by GD and CW and consensus achieved.

Study synthesis

The available total and subscale data from those studies that conducted data collection via the Physical Healthcare Attitude Scale for mental health nurses (PHASe [ 11 ]), the only scale used across more than two studies, was tabulated and compared across studies using unpaired t-tests in QuickCalcs GraphPad software. Where individual item mean and dispersion scores were unavailable estimates were calculated as follows: the mean mean (i.e., Σ means / n means) and the estimated standard deviation (the square root of the average of the variances [ 28 ]). Also, and where available, dichotomised data (‘Strongly agree’ or ‘agree’ responses versus all other responses) from the multiple studies using the 14-item PHASe scale investigating self-reported current involvement in aspects of physical healthcare was tabulated and subjected to Chi-squared analysis. Significant cross-study differences of means and proportions involved all subscale or item data for each study being compared with the corresponding subscale or item from the original study development sample, ‘the reference group’ [ 11 ].

Where available, effect sizes for correlational, interventional, or difference-related outcomes from studies were extracted or, where sufficient information presented, calculated. Where sufficient information was not presented we attempted to contact the corresponding author for clarification. Appropriate effect size statistics were calculated using an online resource [ 29 ]. All other information from study results was subject to a qualitative synthesis conducted by author 1 and subsequently refined and agreed by all of the authors.

Study settings and participants

The search strategy resulted in the inclusion of 41 study samples published in 51 papers (see Fig. 1 ) involving 7549 ( M [ SD ] = 200.5[374.1], Mdn = 47, range 2 to 1899) mental health nurses and n = 213 mental health nursing students ( Mdn = 33). Thirty-three samples included only nurses, of which 20 drew specifically on mental health nurses or nurses working in mental health settings only; eight samples were multidisciplinary. Four papers drew on two samples (i.e., two papers per study) while one sample featured in nine separate papers [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Studies were conducted in the UK ( k = 17), Australia ( k = 9), US ( k = 4), Canada ( k = 2), Qatar, Hong Kong, Japan, Jordan, Belgium, Norway, Israel, Turkey, India, and Taiwan (all k = 1); two studies were conducted internationally; first, in Qatar, Hong Kong, and Japan [ 19 ], and the US and Canada [ 39 ]. Studies were published between 1994 and 2018 ( Mdn year of publication 2016, only n = 9 before 2010 and n = 1 before 2000).

PRISMA study inclusion flowchart

Study design

Eleven studies evaluated an intervention; of these, 10 utilised pre- post AB designs and one adopted a randomised controlled trial design. Other studies used cross-sectional survey or qualitative designs. Intervention studies sometimes incorporated additional qualitative or descriptive elements.

Outcome measures

The most commonly used measure employed was the PHASe or some adaptation of it [ 11 ] in seven studies reported across eight papers [ 11 , 19 , 20 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 ]. The PHASe comprises four factors: 1. Nurses’ attitudes to physical health care; 2. Nurses’ confidence to provide physical health care; 3. Nurses’ perceived barriers in providing physical health care; and 4. Nurses’ attitude towards smoking. Contact with study corresponding authors (Bressington, Chee, Haddad) resulted in acquisition of additional PHASe total and subscale information that was not included in the respective published study papers. Two other outcomes tools were used in two studies each, these being the purpose-designed survey measure of Howard and Gamble [ 45 ] subsequently used by Terry and Cutter [ 46 ], and Happell’s [ 33 ] own questionnaire adapted for use by Clancy et al. [ 40 ]. Most studies used purpose-designed tools. Many reported sufficient information to allow confidence about their internal reliability and face/content validity but there was little information about their measurement reliability, criterion validity, or sensitivity to change (see Additional file 5 : Table S5). A small number of papers used existing validated measures [ 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 ] and these were generally the most robust tools (see Additional file 6 : Table S6).

Study quality

All K = 7 qualitative studies were rated very highly in terms of their quality on a 10-point assessment ( Mdn = 9, range 9–10). Cross-sectional observational studies met a median of four of seven quality criteria (range two to six; mean[SD] 4.43[1.33]). Four of these provided an a priori sample size calculation and there was a lack of valid outcome measures in nine of the 21 studies. Overall risk of bias for cross-sectional studies was judged to be low for nine studies, unclear for six and high for six. The quality of interventional studies was generally the poorest ( Mdn = 5, range 2 to 7 of 10 indicators). Only two were judged to be at low risk of bias (see Additional file 2 : Tables S2, Additional file 3 : Table S3, Additional file 4 : Table S4, Additional file 5 : Table S5 and Additional file 6 : Table S6 for further details). Common omissions were, again, sample size justification, lack of repeat pre-baseline and follow up measures, and information about the representativeness of included samples.

Non-intervention studies

Studies examined physical healthcare in general ( k = 24), sexual health ( k = 4), smoking ( k = 6), physical activity and healthy eating, nutrition - in particular the role of Omega-3 in diet, mild brain injury, and breastfeeding (all k = 1; see Table 1 ).

With regards to studies using the PHASe, of all possible comparisons across studies (see Tables 2 and 3 ), the mean score of the study sample differed significantly from the reference sample [ 11 ] on 13 out of 21 (61.9%) subscale and three of four total score combinations (75.0%). Analysis revealed poorer attitudes compared to the reference sample on all three of the significantly poorer attitude scores on 10/17 (58.9%) subscale comparisons, and better attitudes on three (14.3%). However, the reference group only outperformed the other studies on two of the eight possible comparisons on the subscales ‘Physical Healthcare’ and ‘Confidence in Providing Physical Healthcare’ and was poorer for three comparisons. The PHASe total score difference was greatest (large effect size) between the reference sample and Chee et al’s [ 41 ] Australian sample (Cohens d = 1.13) followed by Bressington et al’s [ 19 ] Japanese mental health nurse sub-sample ( d = 0.72). For subscale scores, effect sizes for differences were also largest between the reference sample and that of Chee et al. [ 41 ]. Effect sizes were in favour of the reference sample on the attitudes to smoking and barriers to physical healthcare subscales ( d = 1.48 and 1.78 respectively). Next largest were differences between Haddad et al’s [ 43 ] sample also on the barriers to healthcare ( d = 0.93) and attitudes to smoking subscales ( d = 1.01). On this occasion differences were in favour of Haddad et al’s [ 43 ] sample. Attitudes to smoking were more favourable than the reference sample in two studies, comparable in one and poorer in two.

Regarding the level of self-reported involvement in aspects of physical healthcare the proportion of respondents in PHASe-studies answering ‘strongly agree’ or ‘agree’ to 14 items revealed considerable cross-sample differences. Of 95 possible comparisons between the reference study and others, 70 (73.7%) differed significantly. Of these, 86.7% compared unfavourably with the UK reference study, 13.3% favourably). The number of items per sample differing from the reference sample ranged from 7 to 13 ( Mdn = 10). Japan [ 19 ] provided the only sample of mental health nurses whose responses compared favourably with the reference sample (7/10 significantly differing responses being more favourable in the Japanese sub-sample), while Ganiah et al’s [ 42 ] sample (0/11 favourable comparisons among significantly differing responses), Happell et al’s [ 30 ] (0/14 favourable comparisons), Chee et al’s [ 41 ] Australian sample (1/11 favourable comparisons), Haddad et al’s [ 43 ] UK sample (1/10 favourable comparisons) and Bressington et al’s [ 19 ] Hong Kong sample (2/12 favourable comparisons) all fared poorly. Items relating to checking GP-status, advising on exercise, weight management, healthy eating, contraception, and eyesight checks were all rated less favourably by at least two other samples (range 2 to 6, Mdn = 4) and more favourably by none compared with the reference sample. Only the item about ensuring patients have had their general physical health assessed on first contact with mental health services was rated more favourably by two samples and less favourably by none compared with the reference sample. For all other items there were item-level variations with no clear pattern.

The remaining non-intervention studies provide a mixed and sometimes contradictory picture. First, in terms of reported use of physical health care skills, Osborn et al’s [ 47 ] study revealed that nurses working in mental health settings in one large hospital were less likely to use physical healthcare skills than colleagues in medical, oncology, maternity and surgical settings. Further, they reported using a smaller range of relevant skills. In Howard and Gamble’s [ 45 ] survey, nurses’ responses indicated a gap between their perceived responsibilities for physical healthcare and their practice. Elsewhere, compared with those responding on behalf of healthcare and educational organisations, nurses were less likely to endorse their role in physical healthcare provision [ 53 ] and they reported very low levels of endorsement of related skills training need [ 54 ]. However, for others in more recent studies, they displayed a clear commitment to the physical healthcare role [ 55 ], and said they want more training [ 31 , 56 ]. Further, nurses strongly endorsed their own role in physical health, sexual health, and substance abuse related care and were supported strongly by other healthcare professionals [ 40 ]. Across a series of linked surveys and qualitative studies, Happell et al. [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 57 ] reported associations between nurses’ positive evaluation of the physical healthcare role and practicing aspects of it more commonly. In studies of nurses and specific physical healthcare-related activities there was a suggestion that respondents’ own values or beliefs might be more influential in determining their health-giving or advising behaviour in relation to smoking cessation [ 50 , 58 ]. In relation to sexual health, both Dorsay and Forchuk [ 59 ] and Quinn et al. [ 60 ] have reported that nurses cite patient embarrassment as a reason for not asking patients about sexual side effects of antipsychotic medications. Lack of time, resources and knowledge were reported as barriers to providing advice and interventions regarding exercise and physical activity [ 61 ], Omega-3 [ 62 ]. Knowledge and attitudes to HIV/AIDS were generally good [ 63 ]. Finally, smoking-cessation training was associated with more smoking-cessation helping behaviour [ 64 ] though, counter-inuitively, training was negatively associated with attitudes to smoking cessation in a single study [ 65 ]. Further, Sharma et al’s [ 64 ] study compared the attitudes of mental health trained nurses and comprehensive/ generalist trained nurses working in mental health services: the most marked differences between the groups were on the smoking-related items with the former group expressing significantly more liberal views about smoking restrictions, more worrying attitudes about the benefits and utility of cigarette use as a therapeutic tool, and less confidence in the ability of mental health patients to quit smoking. This was particularly concerning in the study context which was about attitudes to physical healthcare with younger, first episode psychosis patients.

Intervention studies

Five studies focused on physical healthcare in general and six on specific issues (diabetes n = 3; sexual health, cardiometabolic health, obesity all n = 1). Ten evaluated an educational innovation, the exception being Happell et al. [ 35 ], who examined attitudes among nurses to the introduction of a specialist cardiometabolic health nurse role. Haddad et al. [ 43 ] examined the impact of the introduction of personal physical health care plans for patients on nurses’ physical healthcare attitudes alongside the delivery of a single educational session on physical healthcare assessment. The remaining nine studies evaluated educational interventions including three involving simulation and six involving didactic teaching, workshop-format or blended-learning approaches.

Simulation studies

Duration of interventions was 30 min [ 49 ] and1-day [ 66 ], while information was not provided by Wynn [ 52 ]. The mode of simulation delivery involved manikins [ 66 ], human actor as patient [ 66 ], software-based Human Person Simulator [ 52 ], and participant as ‘patient’ in which student participants wore a 15 kg bariatric empathy suit while undertaking everyday tasks in order to help them appreciate the experience of obesity [ 49 ]. Other simulations involved diabetes care [ 52 ], fractured leg in the context of a jump or fall in a patient with first episode psychosis, medical deterioration in the same patient following transfer to a psychiatric ward, and delirium [ 66 ]. Results indicated improved clinical judgement and reduced diabetes-related medical emergency reports [ 52 ], improved knowledge, attitudes, and confidence about physical healthcare [ 66 ], improved response to obese patients, characteristics of obese patients and supportive roles in caring for obese patients [ 49 ].

Non-simulation studie

Study duration ranged from a 2.5-h workshop on physical health [ 67 ] to a 20-credit bachelor’s degree level (equivalent to 200-h of taught and self-directed study and assessment completion) module on physical healthcare in mental health [ 46 ]. Non-simulation studies evaluated the introduction of personal health plans for patients in a low secure forensic unit together with a single educational session on physical health care for nursing staff [ 43 ]. Specific topics addressed included diabetes [ 68 , 69 ], health assessment [ 46 , 67 ], oral health, IM injectables [ 68 ], vital signs, blood readings, BMI measurement [ 46 ], and cardio-metabolic health [ 35 , 57 ].

In Sung et al’s [ 51 ] RCT, nurses were allocated in a random stratified design to attend 8 × 2-h session about sexual healthcare over a period of 4-w or no intervention. Significant effects were detected in the experimental group relative to the control group for improvements in related knowledge and in attitudes, but not in self-efficacy. The study involved nurses employed both in medical and psychiatric wards (stratified allocation from both) and there was no reported effect of ward-type on outcomes. Pretest- posttest design intervention studies targeted at diabetes found greatly improved clinical judgment in relation to diabetes care and reduced diabetes-related emergency referrals [ 52 ] and similarly impressive improved diabetes-related knowledge [ 69 , 70 ]. Improved attitudes to obesity, obese patients, and supportive roles in caring for obese individuals have been reported across a mixed group of participants and did not differ between mental health and other nurses [ 49 ]. and physical healthcare in general. Happell et al. [ 57 ] reported improved support for a specialist cardiometabolic nurse role following its introduction, however we find this conclusion is unwarranted since it is derived from statistical testing of 14-questionnaire items only one of which was found significant. Interventions aimed at physical healthcare in general found some impressive post- group improvements in knowledge [ 66 , 67 , 68 ], attitudes [ 66 ], and confidence [ 46 , 66 ].

We have conducted a systematic review of the empirical literature about mental health nurses and their attitudes towards, knowledge about, and experiences of physical health care for patients. We took a broad approach to searching the literature and included interventional and observational studies involving real or simulated situations. We included studies involving mental health nursing students and multidisciplinary professional groups in addition to those including only mental health nurses. We contacted study authors to gain additional information and, for the studies using the PHASe [ 11 ] and this elicited significant, previously unpublished information. While we applied no time limits to our comprehensive search we found studies only from as early as 1994, only nine from before 2000, and the median year of publication was 2016. This means that there has been a welcome increase, which we described as a ‘mini-explosion’ in the Introduction, in related empirical work in recent years. The total number of nurses involved in studies, 7549, makes this to our knowledge one of the largest amalgamations of evidence gathered directly from mental health nurses.

However, the overall methodological quality of studies was somewhat limited, particularly interventional studies to improve mental health nurses’ physical healthcare assessment practices and skills. Nevertheless, while many of the included studies examine mental health nurses, and nurses working in mental health settings, this group comprises a heterogeneous collection of individuals of vastly differing experience, preparation, knowledge, and roles. As a result, it is not too surprising that some less well-researched areas have thrown up starkly different results. However, there is consistent evidence that there is a strong association between mental health nurses’ reported attitudes and their reported involvement in physical health care [ 19 , 20 , 42 ]. Similarly, that the nurses who value physical health care also report that they deliver more of it [ 30 ] and those who talk to at least one other discipline about their patients’ physical health do so with multiple professional groups [ 33 ]. Accordingly, fewer resources could be expended on answering these sorts of associational questions in the future.

Our conclusion is that it is now time for a new phase for mental health nursing research related to physical healthcare: efforts must be redoubled to focus on developing and testing interventions to improve nurses’ attitudes, knowledge, and skills. We must ensure that new studies are well-designed and rigorously conducted. More specifically, further research is required to build knowledge about whether the supposed benefits arising from this relationship translate into objectively better practice and indeed better patient outcomes. This would strengthen the case for training to improve attitudes and provide some urgency to better understand what interventions might deliver that outcome. Further, it appears that mental health nurses well-recognise that they require further skills and knowledge related to physical health care across a wide range of areas [ 19 , 30 , 31 , 57 , 71 ]. However, ambivalence and reluctance remains about embracing the change needed to achieve this [ 61 ].

The PHASe was used across multiple studies which allowed for some international and setting-specific comparison of nurses’ attitudes. We found that nurses’ self-perceived practices and attitudes differed significantly between samples from across the world. This, of course, may well reflect different approaches to mental health nurse preparation; for example, in Australia, all pre-registration nurses undergo the same core programme whereas in the UK mental health nursing is a specialist branch of pre-registration training. Therefore, results from Chee et al’s [ 41 ] recent study are enlightening since they reveal equivalent attitudes to physical healthcare specifically, more confidence in delivering physical healthcare but poorer scores in relation to barriers to physical healthcare delivery and smoking cessation. Given the non-equivalence of results on the attitudes to smoking subscale between Chee et al. [ 41 ] and Wynaden et al. [ 44 ], both conducted in Western Australia by related research teams, there are questions about the extent to which results are sample specific. Larger scale, representative data collection in Australia and New Zealand could therefore add significantly to the debate about nurses’ preparation for physical healthcare skills under different preparation regimes. As the PHASe authors’ note, the tool has not been subjected to tests of its stability or criterion validity and improvements in evidence for this would add significantly to the ability to draw sound conclusions from research using the tool. Findings from Osborne et al’s [ 47 ] large hospital-wide survey indicate that the gap in the physical health-related skills addressed by the PHASe is real and of concern.

Apart from the PHASe the literature is peppered with outcomes tools designed for single studies and with little evidence of anything other than face validity and internal consistency. Is it possible, we must ask, that this reflects that researchers are asking the wrong questions i.e., focusing overly on mental health nurses’ attitudes and self-proclaimed knowledge and efficacy when what is now required is a more robust approach to examining their actual knowledge and performance and, crucially, their impact on patient outcomes. Little seems to have been added to the literature on this since Hardy et al. [ 23 ] found no studies to include in their systematic review. Further, Haddad et al’s [ 43 ] study in a low secure forensic setting found nurses scoring favourably on PHASe subscales about attitudes to physical healthcare and to smoking compared with non-forensic nurses in the reference sample, suggesting perhaps that in a setting where length of stay is considerably longer then nurses have more opportunity to engage with patients in this aspect of care. Notably, however, nurses in the same sample compared unfavourably with the reference sample in terms of perceived involvement in actual physical healthcare, a somewhat contradictory finding.

For intervention studies, effect sizes were generally largest, and were in fact sometimes startlingly large, where interventions were targeted and outcomes were knowledge based (e.g., educational studies). This is unsurprising since educational interventions are generally evaluated against criteria that are specifically and directly addressed in the intervention. Outcomes tended to be measured immediately following the training [ 46 , 52 ], but their long term retention is generally not known and neither is any practical beneficial change to practice. The apparent potency of these interventions requires further testing in randomized designs with appropriate follow-up periods.

Some study samples in the current review included non-nursing staff; though their occurrence and representativeness was too limited to allow robust conclusions to be drawn about the relative state of nurses’ knowledge and attitudes within the multidisciplinary team context. Given the current review explicitly focused on mental health nurses then further research exploring the multidisciplinary aspects of physical health care provision is warranted.

Mental health nurses’ ability to provide routine physical healthcare has been highlighted in recent years. Recent literature provides a starting point for future research which must now concentrate on determining the effectiveness of nurse preparation for providing physical health care for people with mental disorder, determining the appropriate content for such preparation, and evaluating the effectiveness both in terms of nurse and patient- related outcomes. At the same time, developments are needed which are congruent with the needs and wants of patients. Perhaps what the included studies best demonstrate is that mental health nurses seem to realise that physical health care is part of their role.

Abbreviations

Medical Subject Headings

Physical Health Attitudes Scale for mental health nurses

Population Intervention Comparator Outcome

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses

Walker ER, McGee E, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat. 2015;72(4):334–41. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502 .

Article Google Scholar

Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiat. 2015;72(12):1172–81. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1737 .

Drope J, Liber AC, Cahn Z, Stoklosa M, Kennedy R, Douglas CE, Henson R, Drope J. Who's still smoking? Disparities in adult cigarette smoking prevalence in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(2):106–15. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21444 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Annamalai A, Kosir U, Tek C. Prevalence of obesity and diabetes in patients with schizophrenia. World J Diabetes. 2017;8(8):390–6. https://doi.org/10.4239/wjd.v8.i8.390 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tomiainen M, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Bjӧrkenstam C, Suvisaari J, Alexanderson K, Tiihonen J. Antipsychotic treatment and mortality in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2016;41(3):656–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbu164 .

World Health Organisation. Guidelines for the management of physical health conditions in adults with severe mental disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

Google Scholar

New South Wales Government. Physical Health Care of Mental Health Consumers. North Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2017. Accessed 29 Jan 2019: https://www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/ActivePDSDocuments/GL2017_019.pdf

Nursing, Midwifery and Allied Health Professions Policy Unit. Improving the physical health of people with mental health problems: Actions for mental health nurses. London: Department of Health; 2016. Accessed 4 Jan 2019 at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/532253/JRA_Physical_Health_revised.pdf

Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Keeping Body and Mind Together: Improving the physical health and life expectancy of people with serious mental illness. Melbourne: Victoria; 2015. Accessed 29 Jan 2019 at: https://www.ranzcp.org/files/resources/reports/ranzcp-keeping-body-and-mind-together.aspx

Department of Health. From values to action: the chief nursing Officer’s review of mental health nursing. London: DOH; 2006.

Robson D, Haddad M. Mental health nurses' attitudes towards the physical health care of people with severe and enduring mental illness: the development of a measurement tool. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(1):72–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.011 .

Blythe J, White J. Role of the mental health nurse towards physical health care in serious mental illness: an integrative review of 10 years of UK literature. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2012;21(3):193–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2011.00792.x .

Happell B, Scott D, Platania-Phung C. Perceptions of barriers to physical health care for people with serious mental illness: a review of the international literature. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33(11):752–61. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2012.708099 .

Happell B, Platania-Phung C, Scott D. A systematic review of nurse physical healthcare for consumers utilizing mental health services. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2014;21(1):11–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12041 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Collins E, Tranter S, Irvine F. The physical health of the seriously mentally ill: an overview of the literature. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2012;19(7):638–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01831.x .

Estabrooks CA, Floyd JA, Scott-Findlay S, O’Leary KA, Gushta M. Individual determinants of research utilization: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2003;43(5):506–20. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02748.x .

Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E, Feinstein NF, Li H, Wilcox L, Kraus R. Nurses’ perceived knowledge, beliefs, skills and needs regarding evidence-based practice: implications for accelerating the paradigm shift. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2004;1(4):185193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04024.x .

Varnell G, Haas B, Duke G, Hudson K. Effect of an educational intervention on attitudes toward and implementation of evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2008;5(4):172–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2008.00124.x .

Bressington D, Badnapurkar A, Inoue S, Ma HY, Chien WT, Nelson D, Gray R. Physical health care for people with severe mental illness. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(343). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020343 .

Robson D, Haddad M, Gray R, Gournay K. Mental health nursing and physical health care: a cross-sectional study of nurses' attitudes, practice, and perceived training needs for the physical health care of people with severe mental illness. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2013;22(5):409–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00883.x .

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 .

Munn Z, Srtern C, Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Jordan Z. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(5):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0468-4 .

Hardy S, White J, Deane K, Gray R. Educating healthcare professionals to act on the physical health needs of people with serious mental illness: a systematic search for evidence. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(8):721–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.13652850.2011.01722.x .

Bland AJ, Topping A, Wood B. A concept analysis of simulation as a learning strategy in the education of undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2011;31:664–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.10.013 .

Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x .

NIH National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (n.d.). Study Quality Assessment Tools: Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross Sectional Studies. Accessed 28 Apr 2018: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (n.d.). CASP checklist: 10 questions to help you make sense of qualitative research. Oxford: CASP. Available at: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf . Accessed 16 Apr 2019.

Campbell MJ. Statistics at square one (9th edition) T.D.V. Swinscow [revised by M.J. Campbell]: University of Southampton: BMJ publishing group; 1997. Accessed 14 Jun 2018: https://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-readers/publications/statistics-square-one/

Wilson, D.B. (n.d.). Practical meta-analysis effect size calculator. Accessed 11 Mar 2019 https://campbellcollaboration.org/escalc/html/EffectSizeCalculator-SMD-main.php .

Happell B, Platania-Phung C, Scott D. Are nurses in mental health services providing physical health care for people with serious mental illness? An Australian perspective. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2013;34(3):198–207. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2012.733907 .

Happell B, Platania-Phung C, Scott D. Physical health care for people with mental illness: training needs for nurses. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33:396–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.01.015 .

Happell B, Platania-Phung C, Scott D. Proposed nurse-led initiatives in improving physical health of people with serious mental illness: a survey of nurses in mental health. J Clin Nurs. 2013;23:1018–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12371 .

Happell B, Platania-Phung C, Scott D, Nankivell J. Communication with colleagues: frequency of collaboration regarding physical health of consumers with mental illness. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2014;50(1):33–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12021 .

Happell B, Platania-Phung C, Scott D. What determines whether nurses provide physical health care to consumers with serious mental illness? Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2014;28:87–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2013.11.001 .

Happell B, Platania-Phung C, Scott D, Stanton R. Predictors of nurse support for the introduction of the cardiometabolic health nurse in the Australian mental health sector. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2015;51(3):162–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12077 .

Happell B, Platania-Phung C. Cardiovascular health promotion and consumers with mental illness in Australia. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2015;36:286–93. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2014.981770 .

Happell B, Platania-Phung C, Stanton R, Millar F. Exploring the views of nurses on the cardiometabolic health nurse in mental health services in Australia. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2015;36:135–44. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2014.901449 .

Happell B, Platania-Phung C, Scott D, Hanley C. Access to dental care and dental ill-health of people with serious mental illness: views of nurses working in mental health settings in Australia. Aust J Prim Health. 2015;21(1):32–7. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY13044 .

Klein TA, Graves JM. A comparison of psychiatric and non-psychiatric nurse practitioner knowledge and management recommendations regarding adolescent mild traumatic brain injury. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2017;23(1):37–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390316668992 .

Clancy R, Lewin TJ, Bowman JA, Kelly BJ, Mullen AD, Flanagan K, Hazelton MJ. Providing physical health care for people accessing mental health services: clinicians’ perceptions of their role. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2018;28(1):256–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12529 .

Chee G, Wynaden D, Heslop K. The provision of physical health care by nurses to young people with first episode psychosis: a cross-sectional study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2018;25(7):411–22.

Ganiah AN, Al-Hussami M, Alhadidi M. Mental health nurses’ attitudes and practice toward physical health care in Jordan. Community Ment Health J. 2017;53(6):725–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0143-6 .

Haddad M, Llewellyn-Jones S, Yarnold S, Simpson A. Improving the physical health of people with severe mental illness in a low secure forensic unit: an uncontrolled evaluation study of staff training and physical health care plans. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2016;25(6):554–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12246 .

Wynaden D, Heslop B, Heslop K, Barr L, Lim E, Chee GL, Murdock J. The chasm of care: where does the mental health nursing responsibility lie for the physical health care of people with severe mental illness? Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2016;25(6):516–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12242 .

Howard L, Gamble C. Supporting mental health nurses to address the physical health needs of people with serious mental illness in acute inpatient care settings. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2010;18(2):105112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01642.x .

Terry J, Cutter J. Does education improve mental health practitioners' confidence in meeting the physical health needs of mental health service users? A mixed methods pilot study. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2013;34(4):249–55. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2012.740768 .

Osborn S, Douglas C, Reid C, Jones L, Gardner G. The primacy of vital signs – acute care nurses’ and midwives’ use of physical assessment skills: a cross sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:952–62 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.01.014 .

Artzi-Medvedik R, Chertok IRA, Romem Y. Nurses' attitudes towards breastfeeding among women with schizophrenia in southern Israel. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 19(8):702–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01846.x .

Hunter J, Rawlings-Anderson K, Lindsay T, Bowden T, Aitken LM. Exploring student nurses' attitudes towards those who are obese and whether these attitudes change following a simulated activity. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;65:225–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.03.013 .

Magor-Blatch LE, Rugendyke AR. Going smoke-free: attitudes of mental health professionals to policy change. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2016;23(5):290–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12309 .

Sung SC, Jiang HH, Chen RR, Chao JK. Bridging the gap in sexual healthcare in nursing practice: implementing a sexual healthcare training programme to improve outcomes. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25:19–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13441 2989-3000.

Wynn SD. Improving the quality of care of veterans with diabetes: a simulation intervention for psychiatric nurses. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2011;49(2):38–45. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20110111-01 .

Brimblecombe N, Tingle A, Tunmore R, Murrells T. Implementing holistic practices in mental health nursing: a national consultation. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(3):339–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.07.021 .

Delaney KR, Hamera E, Drew BL. Health advanced practice nursing: the adequacy of educational preparation: voices of our graduates. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2009;15(6):383–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390309353070 .

Mwebe H. Physical health monitoring in mental health settings: a study exploring mental health nurses' views of their role. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(19/20):3067–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13653 .

Çelik Ince S, Partlak Günüşen N, Serçe Ö. The opinions of Turkish mental health nurses on physical health care for individuals with mental illness: a qualitative study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2018;25(4):245–57.

Happell B, Stanton R, Hoey W, Scott D. Reduced ambivalence to the role of the cardiometabolic health nurse following a 6-month trial. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2015;51(2):80–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12066 .

Sharp DL, Blaakman SW, Cole RE, Evinger JS. Report from a national tobacco dependence survey of psychiatric nurses. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2009;15(3):172–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390309336746 .

Dorsay JP, Forchuk C. Assessment of the sexuality needs of individuals with psychiatric disability. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2009;1(2):93–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.1994.tb00025.x .

Quinn C, Platania-Phung C, Bale C, Happell B, Hughes E. Understanding the current sexual health service provision for mental health consumers by nurses in mental health settings: findings from a survey in Australia and England. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2018;27(5):1522–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12452 .

Verhaege N, De Maeseneer J, Maes L, Van Heeringen C, Annemans L. Health promotion in mental health care: perceptions from patients and mental health nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(11–12):1569–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12076 .

Johannessen B, Skagestad I, Bergkaasa AM. Food as medicine in psychiatric care: which profession should be responsible for imparting knowledge and use of omega-3 fatty acids in psychiatry. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2011;17(2):107–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.08.001 .

Hughes E, Gray R. HIV prevention for people with serious mental illness: a survey of mental health workers' attitudes, knowledge and practice. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(4):591–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02227.x .

Sharma R, Meurk C, Bell S, Ford P, Gartner C. Australian mental health care practitioners’ practices and attitudes for encouraging smoking cessation and tobacco harm reduction in smokers with severe mental illness. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2018;27:247–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12314 .

Parel JT, Khakha DC, Balhara YPS. Do psychiatric nurses have favourable knowledge and attitude towards tobacco prevention among their patients? A cross-sectional study from national capital of India. Asian J Nurs Educ Res. 2018;8(1):01–4. https://doi.org/10.5958/2349-2996.2018.00001.0 .

Fernando A, Attoe C, Jaye P, Cross S, Pathan J, Wessely S. Improving interprofessional approaches to physical and psychiatric comorbidities through simulation. Clin Simul Nurs. 2017;13(4):186193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2016.12.004 .

White J, Hemingway S, Stephenson J. Training mental health nurses to assess the physical health needs of mental health service users: a pre- and post-test analysis. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2014;50(4):243–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12048 .

Hemingway S, Clifton A, Stephenson J, Edward KL. Facilitating knowledge of mental health nurses to undertake physical health interventions: a pre-test/post-test evaluation. J Nurs Manag. 2014;22(3):383–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12220 .

Hemingway S, Stephenson J, Trotter F, Clifton A, Holdich P. Increasing the health literacy of learning disability and mental health nurses in physical care skills: a pre and post-test evaluation of a workshop on diabetes care. Nurse Educ Pract. 2015;15(1):30–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2014.08.003 .

Hemingway S, Trotter F, Stephenson J, Holdich P. Diabetes: Increasing the knowledge base of mental health nurses. Br J Nurs. 2013;22(17):991–5. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2013.22.17.991 .

Nash M. Physical care skills: a training needs analysis of inpatient and community mental health nurses. Ment Health Pract. 2005;9(4):20–3. https://doi.org/10.7748/mhp2005.12.9.4.20.c1896 .

Happell B, Scott D, Nankivell J, Platania-Phung C. Nurses’ views on training needs to increase provision of primary care for consumers with serious mental illness. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2013;49:210–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6163.2012.00351.x .

Happell B, Scott D, Nankivell J, Platania-Phung C. Screening physical health? Yes! But…: nurses’ views on physical health screening in mental health care. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:2286–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04325.x .

Birks M, Cant R, James A, Chung C, Davis J. The use of physical assessment skills by registered nurses in Australia: issues for nursing education. Collegian. 2012;20:27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2012.02.004 .

Giddens JF. A survey of physical assessment techniques performed by RNs: lessons for nursing education. J Nurs Educ. 2007;46:83–7.

PubMed Google Scholar

Douglas C, Osborne S, Reid C, Batch M, Hollingdrake O, Gardner G. What factors influence nurses’ assessment practices? Development of the barriers to nurses’ use of physical assessment scale. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70:2683–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12408 .

Phelan M, Stradins L, Amin D, Isadore R, Hitrov C, Doyle A, Inglis R. The physical health check: a tool for mental health workers. J Ment Health. 2004;13(3):277–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230410001700907 .

Shuel F, White J, Jones M, Gray R. Using the serious mental illness health improvement profile [HIP] to identify physical problems in a cohort of community patients: a pragmatic case series evaluation. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(2):136–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.06.003 .

Freed GL, Clark SJ, Sorensen J, Lohr JA, Cefalo R, Curtis P. National assessment of physicians’ breastfeeding knowledge, attitudes, training, and experience. JAMA. 1995;273:472–6.

Corrigan P, Markowitz FE, Watson A, Rowan D, Kubiak MA. An attribution model of public discrimination towards persons with mental illness. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44(2):162–79.

Shore TH, Tashchian A, Adams JS. Development and validation of a scale measuring attitudes toward smoking. J Soc Psychol. 2000;140(5):615–23.

Nash M. Mental health nurses' diabetes care skills - a training needs analysis. Br J Nurs. 2009;18(10):626–30. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2009.18.10.42472 .

Quinn C, Happell B, Browne G. Opportunity lost? Psychiatric medications and problems with sexual function: a role for nurses in mental health. J Clin Nurs. 2011;21:415–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03908.x .

Ford P, Tran P, Keen B, Gartner C. Survey of Australian oral health practitioners and their smoking cessation practices. Aust Dent J. 2015;60:43–51.

Morris C, Waxmonsky J, May M, Giese A, Martin L. Smoking cessation for persons with mental illness: a toolkit for mental health providers: University pf Colorado Denver, CO; 2009. Accessed 19 Mar 2019: https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/Smoking_Cessation_for_Persons_with_MI.pdf

Watson L, Oberle K, Deutscher D. Development and psychometric testing of the Nurses' attitudes toward obesity and obese patients scale (NATOOPS). Res Nurs Health. 2008;31(6):586–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20292 .

Lasater K. Clinical judgment development: using simulation to create an assessment rubric. J Nurs Educ. 2007;46(11):496–503. https://doi.org/10.1097/NND.0000000000000209 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The study was partly funded as part of the CUBIC Capability, Capacity and Cultural Change project funded by Nursing and Midwifery Office (NaMO) New South Wales

‘The funding body played no part in the in the design of the study, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.’

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files] and, where applicable data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Professor Mental Health Nursing, Centre for Applied Nursing Research (CANR), Western Sydney University, Sydney, Australia

Geoffrey L. Dickens, Cheryl Waters, Evan Atlantis & Bronwyn Everett

South West Sydney Local Health District, Sydney, Australia

Geoffrey L. Dickens

Division of Mental Health Nursing and Counselling, Abertay University, Dundee, Scotland

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

GLD conceived of and designed the study. GLD, RI, CW, EA, BE contributed to acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. GLD, RI, CW, EA, BE contributed to drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. GLD, RI, CW, EA, BE gave final approval of the version to be published. GLD, RI, CW, EA, BE agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Geoffrey L. Dickens .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:.

Table S1. Example PICO-style electronic literature search. Example literature search (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S2. Controlled intervention evaluation study quality assessment. Study Quality Assessment (controlled intervention study) (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional file 3:

Table S3. Cross-sectional, observational studies quality assessment (adapted from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [ 26 ]. Study Quality Assessment (Cross-sectional and observational studies) (DOCX 16 kb)

Additional file 4:

Table S4. Longitudinal uncontrolled intervention study quality assessment. Study Quality Assessment (uncontrolled intervention studies) (DOCX 14 kb)

Additional file 5:

Table S5. Qualitative study quality assessment. Study Quality Assessment. (Qualitative studies) (DOCX 14 kb)

Additional file 6:

Table S6. Outcome measure content and quality assessment. Quality assessment of outcomes measures used in studies. (DOCX 25 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.