How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

A demo is the first step to transforming your business. Meet with us to develop a plan for attaining your goals.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Research, expert insights, and resources to develop courageous leaders within your organization.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

How to write a speech that your audience remembers

Whether in a work meeting or at an investor panel, you might give a speech at some point. And no matter how excited you are about the opportunity, the experience can be nerve-wracking .

But feeling butterflies doesn’t mean you can’t give a great speech. With the proper preparation and a clear outline, apprehensive public speakers and natural wordsmiths alike can write and present a compelling message. Here’s how to write a good speech you’ll be proud to deliver.

What is good speech writing?

Good speech writing is the art of crafting words and ideas into a compelling, coherent, and memorable message that resonates with the audience. Here are some key elements of great speech writing:

- It begins with clearly understanding the speech's purpose and the audience it seeks to engage.

- A well-written speech clearly conveys its central message, ensuring that the audience understands and retains the key points.

- It is structured thoughtfully, with a captivating opening, a well-organized body, and a conclusion that reinforces the main message.

- Good speech writing embraces the power of engaging content, weaving in stories, examples, and relatable anecdotes to connect with the audience on both intellectual and emotional levels.

Ultimately, it is the combination of these elements, along with the authenticity and delivery of the speaker , that transforms words on a page into a powerful and impactful spoken narrative.

What makes a good speech?

A great speech includes several key qualities, but three fundamental elements make a speech truly effective:

Clarity and purpose

Remembering the audience, cohesive structure.

While other important factors make a speech a home run, these three elements are essential for writing an effective speech.

The main elements of a good speech

The main elements of a speech typically include:

- Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your speech and grabs the audience's attention. It should include a hook or attention-grabbing opening, introduce the topic, and provide an overview of what will be covered.

- Opening/captivating statement: This is a strong statement that immediately engages the audience and creates curiosity about the speech topics.

- Thesis statement/central idea: The thesis statement or central idea is a concise statement that summarizes the main point or argument of your speech. It serves as a roadmap for the audience to understand what your speech is about.

- Body: The body of the speech is where you elaborate on your main points or arguments. Each point is typically supported by evidence, examples, statistics, or anecdotes. The body should be organized logically and coherently, with smooth transitions between the main points.

- Supporting evidence: This includes facts, data, research findings, expert opinions, or personal stories that support and strengthen your main points. Well-chosen and credible evidence enhances the persuasive power of your speech.

- Transitions: Transitions are phrases or statements that connect different parts of your speech, guiding the audience from one idea to the next. Effective transitions signal the shifts in topics or ideas and help maintain a smooth flow throughout the speech.

- Counterarguments and rebuttals (if applicable): If your speech involves addressing opposing viewpoints or counterarguments, you should acknowledge and address them. Presenting counterarguments makes your speech more persuasive and demonstrates critical thinking.

- Conclusion: The conclusion is the final part of your speech and should bring your message to a satisfying close. Summarize your main points, restate your thesis statement, and leave the audience with a memorable closing thought or call to action.

- Closing statement: This is the final statement that leaves a lasting impression and reinforces the main message of your speech. It can be a call to action, a thought-provoking question, a powerful quote, or a memorable anecdote.

- Delivery and presentation: How you deliver your speech is also an essential element to consider. Pay attention to your tone, body language, eye contact , voice modulation, and timing. Practice and rehearse your speech, and try using the 7-38-55 rule to ensure confident and effective delivery.

While the order and emphasis of these elements may vary depending on the type of speech and audience, these elements provide a framework for organizing and delivering a successful speech.

How to structure a good speech

You know what message you want to transmit, who you’re delivering it to, and even how you want to say it. But you need to know how to start, develop, and close a speech before writing it.

Think of a speech like an essay. It should have an introduction, conclusion, and body sections in between. This places ideas in a logical order that the audience can better understand and follow them. Learning how to make a speech with an outline gives your storytelling the scaffolding it needs to get its point across.

Here’s a general speech structure to guide your writing process:

- Explanation 1

- Explanation 2

- Explanation 3

How to write a compelling speech opener

Some research shows that engaged audiences pay attention for only 15 to 20 minutes at a time. Other estimates are even lower, citing that people stop listening intently in fewer than 10 minutes . If you make a good first impression at the beginning of your speech, you have a better chance of interesting your audience through the middle when attention spans fade.

Implementing the INTRO model can help grab and keep your audience’s attention as soon as you start speaking. This acronym stands for interest, need, timing, roadmap, and objectives, and it represents the key points you should hit in an opening.

Here’s what to include for each of these points:

- Interest : Introduce yourself or your topic concisely and speak with confidence . Write a compelling opening statement using relevant data or an anecdote that the audience can relate to.

- Needs : The audience is listening to you because they have something to learn. If you’re pitching a new app idea to a panel of investors, those potential partners want to discover more about your product and what they can earn from it. Read the room and gently remind them of the purpose of your speech.

- Timing : When appropriate, let your audience know how long you’ll speak. This lets listeners set expectations and keep tabs on their own attention span. If a weary audience member knows you’ll talk for 40 minutes, they can better manage their energy as that time goes on.

- Routemap : Give a brief overview of the three main points you’ll cover in your speech. If an audience member’s attention starts to drop off and they miss a few sentences, they can more easily get their bearings if they know the general outline of the presentation.

- Objectives : Tell the audience what you hope to achieve, encouraging them to listen to the end for the payout.

Writing the middle of a speech

The body of your speech is the most information-dense section. Facts, visual aids, PowerPoints — all this information meets an audience with a waning attention span. Sticking to the speech structure gives your message focus and keeps you from going off track, making everything you say as useful as possible.

Limit the middle of your speech to three points, and support them with no more than three explanations. Following this model organizes your thoughts and prevents you from offering more information than the audience can retain.

Using this section of the speech to make your presentation interactive can add interest and engage your audience. Try including a video or demonstration to break the monotony. A quick poll or survey also keeps the audience on their toes.

Wrapping the speech up

To you, restating your points at the end can feel repetitive and dull. You’ve practiced countless times and heard it all before. But repetition aids memory and learning , helping your audience retain what you’ve told them. Use your speech’s conclusion to summarize the main points with a few short sentences.

Try to end on a memorable note, like posing a motivational quote or a thoughtful question the audience can contemplate once they leave. In proposal or pitch-style speeches, consider landing on a call to action (CTA) that invites your audience to take the next step.

How to write a good speech

If public speaking gives you the jitters, you’re not alone. Roughly 80% of the population feels nervous before giving a speech, and another 10% percent experiences intense anxiety and sometimes even panic.

The fear of failure can cause procrastination and can cause you to put off your speechwriting process until the last minute. Finding the right words takes time and preparation, and if you’re already feeling nervous, starting from a blank page might seem even harder.

But putting in the effort despite your stress is worth it. Presenting a speech you worked hard on fosters authenticity and connects you to the subject matter, which can help your audience understand your points better. Human connection is all about honesty and vulnerability, and if you want to connect to the people you’re speaking to, they should see that in you.

1. Identify your objectives and target audience

Before diving into the writing process, find healthy coping strategies to help you stop worrying . Then you can define your speech’s purpose, think about your target audience, and start identifying your objectives. Here are some questions to ask yourself and ground your thinking :

- What purpose do I want my speech to achieve?

- What would it mean to me if I achieved the speech’s purpose?

- What audience am I writing for?

- What do I know about my audience?

- What values do I want to transmit?

- If the audience remembers one take-home message, what should it be?

- What do I want my audience to feel, think, or do after I finish speaking?

- What parts of my message could be confusing and require further explanation?

2. Know your audience

Understanding your audience is crucial for tailoring your speech effectively. Consider the demographics of your audience, their interests, and their expectations. For instance, if you're addressing a group of healthcare professionals, you'll want to use medical terminology and data that resonate with them. Conversely, if your audience is a group of young students, you'd adjust your content to be more relatable to their experiences and interests.

3. Choose a clear message

Your message should be the central idea that you want your audience to take away from your speech. Let's say you're giving a speech on climate change. Your clear message might be something like, "Individual actions can make a significant impact on mitigating climate change." Throughout your speech, all your points and examples should support this central message, reinforcing it for your audience.

4. Structure your speech

Organizing your speech properly keeps your audience engaged and helps them follow your ideas. The introduction should grab your audience's attention and introduce the topic. For example, if you're discussing space exploration, you could start with a fascinating fact about a recent space mission. In the body, you'd present your main points logically, such as the history of space exploration, its scientific significance, and future prospects. Finally, in the conclusion, you'd summarize your key points and reiterate the importance of space exploration in advancing human knowledge.

5. Use engaging content for clarity

Engaging content includes stories, anecdotes, statistics, and examples that illustrate your main points. For instance, if you're giving a speech about the importance of reading, you might share a personal story about how a particular book changed your perspective. You could also include statistics on the benefits of reading, such as improved cognitive abilities and empathy.

6. Maintain clarity and simplicity

It's essential to communicate your ideas clearly. Avoid using overly technical jargon or complex language that might confuse your audience. For example, if you're discussing a medical breakthrough with a non-medical audience, explain complex terms in simple, understandable language.

7. Practice and rehearse

Practice is key to delivering a great speech. Rehearse multiple times to refine your delivery, timing, and tone. Consider using a mirror or recording yourself to observe your body language and gestures. For instance, if you're giving a motivational speech, practice your gestures and expressions to convey enthusiasm and confidence.

8. Consider nonverbal communication

Your body language, tone of voice, and gestures should align with your message . If you're delivering a speech on leadership, maintain strong eye contact to convey authority and connection with your audience. A steady pace and varied tone can also enhance your speech's impact.

9. Engage your audience

Engaging your audience keeps them interested and attentive. Encourage interaction by asking thought-provoking questions or sharing relatable anecdotes. If you're giving a speech on teamwork, ask the audience to recall a time when teamwork led to a successful outcome, fostering engagement and connection.

10. Prepare for Q&A

Anticipate potential questions or objections your audience might have and prepare concise, well-informed responses. If you're delivering a speech on a controversial topic, such as healthcare reform, be ready to address common concerns, like the impact on healthcare costs or access to services, during the Q&A session.

By following these steps and incorporating examples that align with your specific speech topic and purpose, you can craft and deliver a compelling and impactful speech that resonates with your audience.

Tools for writing a great speech

There are several helpful tools available for speechwriting, both technological and communication-related. Here are a few examples:

- Word processing software: Tools like Microsoft Word, Google Docs, or other word processors provide a user-friendly environment for writing and editing speeches. They offer features like spell-checking, grammar correction, formatting options, and easy revision tracking.

- Presentation software: Software such as Microsoft PowerPoint or Google Slides is useful when creating visual aids to accompany your speech. These tools allow you to create engaging slideshows with text, images, charts, and videos to enhance your presentation.

- Speechwriting Templates: Online platforms or software offer pre-designed templates specifically for speechwriting. These templates provide guidance on structuring your speech and may include prompts for different sections like introductions, main points, and conclusions.

- Rhetorical devices and figures of speech: Rhetorical tools such as metaphors, similes, alliteration, and parallelism can add impact and persuasion to your speech. Resources like books, websites, or academic papers detailing various rhetorical devices can help you incorporate them effectively.

- Speechwriting apps: Mobile apps designed specifically for speechwriting can be helpful in organizing your thoughts, creating outlines, and composing a speech. These apps often provide features like voice recording, note-taking, and virtual prompts to keep you on track.

- Grammar and style checkers: Online tools or plugins like Grammarly or Hemingway Editor help improve the clarity and readability of your speech by checking for grammar, spelling, and style errors. They provide suggestions for sentence structure, word choice, and overall tone.

- Thesaurus and dictionary: Online or offline resources such as thesauruses and dictionaries help expand your vocabulary and find alternative words or phrases to express your ideas more effectively. They can also clarify meanings or provide context for unfamiliar terms.

- Online speechwriting communities: Joining online forums or communities focused on speechwriting can be beneficial for getting feedback, sharing ideas, and learning from experienced speechwriters. It's an opportunity to connect with like-minded individuals and improve your public speaking skills through collaboration.

Remember, while these tools can assist in the speechwriting process, it's essential to use them thoughtfully and adapt them to your specific needs and style. The most important aspect of speechwriting remains the creativity, authenticity, and connection with your audience that you bring to your speech.

5 tips for writing a speech

Behind every great speech is an excellent idea and a speaker who refined it. But a successful speech is about more than the initial words on the page, and there are a few more things you can do to help it land.

Here are five more tips for writing and practicing your speech:

1. Structure first, write second

If you start the writing process before organizing your thoughts, you may have to re-order, cut, and scrap the sentences you worked hard on. Save yourself some time by using a speech structure, like the one above, to order your talking points first. This can also help you identify unclear points or moments that disrupt your flow.

2. Do your homework

Data strengthens your argument with a scientific edge. Research your topic with an eye for attention-grabbing statistics, or look for findings you can use to support each point. If you’re pitching a product or service, pull information from company metrics that demonstrate past or potential successes.

Audience members will likely have questions, so learn all talking points inside and out. If you tell investors that your product will provide 12% returns, for example, come prepared with projections that support that statement.

3. Sound like yourself

Memorable speakers have distinct voices. Think of Martin Luther King Jr’s urgent, inspiring timbre or Oprah’s empathetic, personal tone . Establish your voice — one that aligns with your personality and values — and stick with it. If you’re a motivational speaker, keep your tone upbeat to inspire your audience . If you’re the CEO of a startup, try sounding assured but approachable.

4. Practice

As you practice a speech, you become more confident , gain a better handle on the material, and learn the outline so well that unexpected questions are less likely to trip you up. Practice in front of a colleague or friend for honest feedback about what you could change, and speak in front of the mirror to tweak your nonverbal communication and body language .

5. Remember to breathe

When you’re stressed, you breathe more rapidly . It can be challenging to talk normally when you can’t regulate your breath. Before your presentation, try some mindful breathing exercises so that when the day comes, you already have strategies that will calm you down and remain present . This can also help you control your voice and avoid speaking too quickly.

How to ghostwrite a great speech for someone else

Ghostwriting a speech requires a unique set of skills, as you're essentially writing a piece that will be delivered by someone else. Here are some tips on how to effectively ghostwrite a speech:

- Understand the speaker's voice and style : Begin by thoroughly understanding the speaker's personality, speaking style, and preferences. This includes their tone, humor, and any personal anecdotes they may want to include.

- Interview the speaker : Have a detailed conversation with the speaker to gather information about their speech's purpose, target audience, key messages, and any specific points they want to emphasize. Ask for personal stories or examples they may want to include.

- Research thoroughly : Research the topic to ensure you have a strong foundation of knowledge. This helps you craft a well-informed and credible speech.

- Create an outline : Develop a clear outline that includes the introduction, main points, supporting evidence, and a conclusion. Share this outline with the speaker for their input and approval.

- Write in the speaker's voice : While crafting the speech, maintain the speaker's voice and style. Use language and phrasing that feel natural to them. If they have a particular way of expressing ideas, incorporate that into the speech.

- Craft a captivating opening : Begin the speech with a compelling opening that grabs the audience's attention. This could be a relevant quote, an interesting fact, a personal anecdote, or a thought-provoking question.

- Organize content logically : Ensure the speech flows logically, with each point building on the previous one. Use transitions to guide the audience from one idea to the next smoothly.

- Incorporate engaging stories and examples : Include anecdotes, stories, and real-life examples that illustrate key points and make the speech relatable and memorable.

- Edit and revise : Edit the speech carefully for clarity, grammar, and coherence. Ensure the speech is the right length and aligns with the speaker's time constraints.

- Seek feedback : Share drafts of the speech with the speaker for their feedback and revisions. They may have specific changes or additions they'd like to make.

- Practice delivery : If possible, work with the speaker on their delivery. Practice the speech together, allowing the speaker to become familiar with the content and your writing style.

- Maintain confidentiality : As a ghostwriter, it's essential to respect the confidentiality and anonymity of the work. Do not disclose that you wrote the speech unless you have the speaker's permission to do so.

- Be flexible : Be open to making changes and revisions as per the speaker's preferences. Your goal is to make them look good and effectively convey their message.

- Meet deadlines : Stick to agreed-upon deadlines for drafts and revisions. Punctuality and reliability are essential in ghostwriting.

- Provide support : Support the speaker during their preparation and rehearsal process. This can include helping with cue cards, speech notes, or any other materials they need.

Remember that successful ghostwriting is about capturing the essence of the speaker while delivering a well-structured and engaging speech. Collaboration, communication, and adaptability are key to achieving this.

Give your best speech yet

Learn how to make a speech that’ll hold an audience’s attention by structuring your thoughts and practicing frequently. Put the effort into writing and preparing your content, and aim to improve your breathing, eye contact , and body language as you practice. The more you work on your speech, the more confident you’ll become.

The energy you invest in writing an effective speech will help your audience remember and connect to every concept. Remember: some life-changing philosophies have come from good speeches, so give your words a chance to resonate with others. You might even change their thinking.

Elevate your communication skills

Unlock the power of clear and persuasive communication. Our coaches can guide you to build strong relationships and succeed in both personal and professional life.

Elizabeth Perry, ACC

Elizabeth Perry is a Coach Community Manager at BetterUp. She uses strategic engagement strategies to cultivate a learning community across a global network of Coaches through in-person and virtual experiences, technology-enabled platforms, and strategic coaching industry partnerships. With over 3 years of coaching experience and a certification in transformative leadership and life coaching from Sofia University, Elizabeth leverages transpersonal psychology expertise to help coaches and clients gain awareness of their behavioral and thought patterns, discover their purpose and passions, and elevate their potential. She is a lifelong student of psychology, personal growth, and human potential as well as an ICF-certified ACC transpersonal life and leadership Coach.

6 presentation skills and how to improve them

10+ interpersonal skills at work and ways to develop them, how to be more persuasive: 6 tips for convincing others, how to write an impactful cover letter for a career change, self-management skills for a messy world, learn types of gestures and their meanings to improve your communication, what are analytical skills examples and how to level up, a guide on how to find the right mentor for your career, asking for a raise: tips to get what you’re worth, similar articles, how to write an executive summary in 10 steps, the importance of good speech: 5 tips to be more articulate, how to pitch ideas: 8 tips to captivate any audience, how to give a good presentation that captivates any audience, anxious about meetings learn how to run a meeting with these 10 tips, writing an elevator pitch about yourself: a how-to plus tips, how to make a presentation interactive and exciting, how to write a memo: 8 steps with examples, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform Overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care™

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case Studies

- Why BetterUp?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Life Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Labs

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

Speechwriting 101: Writing an Effective Speech

Whether you are a communications pro or a human resources executive, the time will come when you will need to write a speech for yourself or someone else. when that time comes, your career may depend on your success..

J. Lyman MacInnis, a corporate coach, Toronto Star columnist, accounting executive and author of “ The Elements of Great Public Speaking ,” has seen careers stalled – even damaged – by a failure to communicate messages effectively before groups of people. On the flip side, solid speechwriting skills can help launch and sustain a successful career. What you need are forethought and methodical preparation.

Know Your Audience

Learn as much as possible about the audience and the event. This will help you target the insights, experience or knowledge you have that this group wants or needs:

- Why has the audience been brought together?

- What do the members of the audience have in common?

- How big an audience will it be?

- What do they know, and what do they need to know?

- Do they expect discussion about a specific subject and, if so, what?

- What is the audience’s attitude and knowledge about the subject of your talk?

- What is their attitude toward you as the speaker?

- Why are they interested in your topic?

Choose Your Core Message

If the core message is on target, you can do other things wrong. But if the message is wrong, it doesn’t matter what you put around it. To write the most effective speech, you should have significant knowledge about your topic, sincerely care about it and be eager to talk about it. Focus on a message that is relevant to the target audience, and remember: an audience wants opinion. If you offer too little substance, your audience will label you a lightweight. If you offer too many ideas, you make it difficult for them to know what’s important to you.

Research and Organize

Research until you drop. This is where you pick up the information, connect the ideas and arrive at the insights that make your talk fresh. You’ll have an easier time if you gather far more information than you need. Arrange your research and notes into general categories and leave space between them. Then go back and rearrange. Fit related pieces together like a puzzle.

Develop Structure to Deliver Your Message

First, consider whether your goal is to inform, persuade, motivate or entertain. Then outline your speech and fill in the details:

- Introduction – The early minutes of a talk are important to establish your credibility and likeability. Personal anecdotes often work well to get things started. This is also where you’ll outline your main points.

- Body – Get to the issues you’re there to address, limiting them to five points at most. Then bolster those few points with illustrations, evidence and anecdotes. Be passionate: your conviction can be as persuasive as the appeal of your ideas.

- Conclusion – Wrap up with feeling as well as fact. End with something upbeat that will inspire your listeners.

You want to leave the audience exhilarated, not drained. In our fast-paced age, 20-25 minutes is about as long as anyone will listen attentively to a speech. As you write and edit your speech, the general rule is to allow about 90 seconds for every double-spaced page of copy.

Spice it Up

Once you have the basic structure of your speech, it’s time to add variety and interest. Giving an audience exactly what it expects is like passing out sleeping pills. Remember that a speech is more like conversation than formal writing. Its phrasing is loose – but without the extremes of slang, the incomplete thoughts, the interruptions that flavor everyday speech.

- Give it rhythm. A good speech has pacing.

- Vary the sentence structure. Use short sentences. Use occasional long ones to keep the audience alert. Fragments are fine if used sparingly and for emphasis.

- Use the active voice and avoid passive sentences. Active forms of speech make your sentences more powerful.

- Repeat key words and points. Besides helping your audience remember something, repetition builds greater awareness of central points or the main theme.

- Ask rhetorical questions in a way that attracts your listeners’ attention.

- Personal experiences and anecdotes help bolster your points and help you connect with the audience.

- Use quotes. Good quotes work on several levels, forcing the audience to think. Make sure quotes are clearly attributed and said by someone your audience will probably recognize.

Be sure to use all of these devices sparingly in your speeches. If overused, the speech becomes exaggerated. Used with care, they will work well to move the speech along and help you deliver your message in an interesting, compelling way.

More News & Resources

Measuring and Communicating the Value of Public Affairs

July 26, 2023

Benchmarking Reports Reveal Public Affairs’ Growing Status

November 16, 2023

Volunteer of the Year Was Integral to New Fellowship

Is the Fight for the Senate Over?

New Council Chair Embraces Challenge of Changing Profession

October 25, 2023

Are We About to Have a Foreign Policy Election?

Few Americans Believe 2024 Elections Will Be ‘Honest and Open’

Rural Americans vs. Urban Americans

August 3, 2023

What Can We Learn from DeSantis-Disney Grudge Match?

June 29, 2023

Laura Brigandi Manager of Digital and Advocacy Practice 202.787.5976 | [email protected]

Featured Event

Digital media & advocacy summit.

The leading annual event for digital comms and advocacy professionals. Hear new strategies, and case studies for energizing grassroots and policy campaigns.

Washington, D.C. | June 10, 2024

Previous Post Hiring Effectively With an Executive Recruiter

Next post guidance on social media policies for external audiences.

Comments are closed.

Public Affairs Council 2121 K St. N.W., Suite 900 Washington, DC 20037 (+1) 202.787.5950 [email protected]

European Office

Public Affairs Council Square Ambiorix 7 1000 Brussels [email protected]

Contact Who We Are

Stay Connected

LinkedIn X (Twitter) Instagram Facebook Mailing List

Read our Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | COPYRIGHT 2024 PUBLIC AFFAIRS COUNCIL

- Browse All Content

- Upcoming Events

- On-Demand Recordings

- Team Training with ‘Membership Plus+’

- Earn Your Certificate

- Sponsorship Opportunities

- Content Search

- Connect with Our Experts

- PAC & Political Engagement

- Grassroots & Digital Advocacy

- Communications

- Social Impact

- Government Relations

- Public Affairs Management

- Browse Research

- Legal Guidance

- Election Insights

- Benchmarking, Consulting & Training

- Where to Start

- Latest News

- Impact Monthly Newsletter

- Member Spotlight

- Membership Directory

- Recognition

The Complete Beginner’s Guide To Writing A Speech

Writers Write creates writing resources and shares writing tips. In this post, we offer you the complete beginner’s guide to writing a speech .

Last week I started my series on speech writing with What People Expect From A Speech . Today I am going to give you a foolproof guide that will help you structure the speech.

Speech Writing Part Two: How To Write The Speech

Who will deliver the speech.

Make sure you write a speech that fits the personality, speech patterns, and competency level of the speaker. If you do not know the person, try to arrange a short interview with them. Find out who they are, what tone suits them, and what they want to communicate.

Persuade With A Classic Structure

The classic structure of a persuasive speech is to state a problem and offer a solution.

- In the first part of your speech you state: ‘This is the problem.’

- In the second part of your speech you cover: ‘This is what we can do to fix it or make things better.’

- Answer the five Ws and the one H about the topic: who, what, where, when, why, and how.

- Write your main ideas down, including your research, data and quotations.

- Make a linear timeline for the speech, linking the points together making sure that they flow in a smooth, logical progression. Do not move away from this linear format. If you do, you will digress and lose the message.

- Write your introduction, including the hook you want to use to get your audience to listen to you.

- Write your ending, briefly summarising your main ideas. If you want your audience to do something, end with a call for action.

- Remember the length of a speech, as explained in What People Expect From A Speech is important.

- An easy way to explain the process is as follows:

- Tell them what you’re going to tell them (Introduction) 15%

- Tell them (Body of your speech – the main ideas plus examples) 70%

- Tell them what you told them (The ending) 15%

About The Introduction

Do not waste time. People make the mistake of starting speeches by effusively thanking everybody and telling us how happy they are to be there. It is a good idea to explain quickly what your main point is going to be. That helps the audience know what to listen for. Then start with a statistic, or a question to interact with the audience.

All good speeches are only about one thing. Get straight into the story and tell the audience what you’re going to tell them.

About The Body

Nobody likes to be bored. Imagine yourself in your audience’s shoes. What would you like to hear from the speaker? Do not put too much information into your speech. If people read a newspaper or a blog, and do not understand something, they read it again. They cannot do this with a speech. Get it right the first time.

Remember you are not writing a formal essay. People will hear the speech and it should sound conversational.

- Use shorter sentences. It is better to write two simple sentences than one long, complicated sentence.

- Use contractions. Say ‘I’m’ instead of ‘I am’, and ‘we’re’ instead of ‘we are’.

- Do not use big words when simple ones do the work for you.

- Never use jargon or acronyms.

- You do not have to follow all the rules of written English grammar strictly, for example, you can use fragments.

About The Ending

End by answering the question you asked at the beginning. Then tell everybody what you have told them – listeners need you to do this. End your speech on a positive note. This is what they will remember.

Watch out for next week’s post, Part Three: Delivering The Speech

If you need to write speeches, you should attend this course: Can I Change Your Mind?

If you enjoyed this post, read:

- 5 Important Things You Need to Know About Writing Speeches

- 18 Things Writers Need To Know About Editing And Proofreading

- 7 Choices That Affect A Writer’s Style

- Business Writing Tips , Writing Speeches , Writing Tips from Amanda Patterson

2 thoughts on “The Complete Beginner’s Guide To Writing A Speech”

I want to thank you Writers Write for these notes, they really help. Especially for beginners like me. Hopefully I’ll be joining your classes soon.

Comments are closed.

© Writers Write 2022

Rice Speechwriting

Beginners guide to what is a speech writing, what is a speech writing: a beginner’s guide, what is the purpose of speech writing.

The purpose of speech writing is to craft a compelling and effective speech that conveys a specific message or idea to an audience. It involves writing a script that is well-structured, engaging, and tailored to the speaker’s delivery style and the audience’s needs.

Have you ever been called upon to deliver a speech and didn’t know where to start? Or maybe you’re looking to improve your public speaking skills and wondering how speech writing can help. Whatever the case may be, this beginner’s guide on speech writing is just what you need. In this blog, we will cover everything from understanding the art of speech writing to key elements of an effective speech. We will also discuss techniques for engaging speech writing, the role of audience analysis in speech writing, time and length considerations, and how to practice and rehearse your speech. By the end of this article, you will have a clear understanding of how speech writing can improve your public speaking skills and make you feel confident when delivering your next big presentation.

Understanding the Art of Speech Writing

Crafting a speech involves melding spoken and written language. Tailoring the speech to the audience and occasion is crucial, as is captivating the audience and evoking emotion. Effective speeches utilize rhetorical devices, anecdotes, and a conversational tone. Structuring the speech with a compelling opener, clear points, and a strong conclusion is imperative. Additionally, employing persuasive language and maintaining simplicity are essential elements. The University of North Carolina’s writing center greatly emphasizes the importance of using these techniques.

The Importance of Speech Writing

Crafting a persuasive and impactful speech is essential for reaching your audience effectively. A well-crafted speech incorporates a central idea, main point, and a thesis statement to engage the audience. Whether it’s for a large audience or different ways of public speaking, good speech writing ensures that your message resonates with the audience. Incorporating engaging visual aids, an impactful introduction, and a strong start are key features of a compelling speech. Embracing these elements sets the stage for a successful speech delivery.

The Role of a Speech Writer

A speechwriter holds the responsibility of composing speeches for various occasions and specific points, employing a speechwriting process that includes audience analysis for both the United States and New York audiences. This written text is essential for delivering impactful and persuasive messages, often serving as a good start to a great speech. Utilizing NLP terms like ‘short sentences’ and ‘persuasion’ enhances the content’s quality and relevance.

Key Elements of Effective Speech Writing

Balancing shorter sentences with longer ones is essential for crafting an engaging speech. Including subordinate clauses and personal stories caters to the target audience and adds persuasion. The speechwriting process, including the thesis statement and a compelling introduction, ensures the content captures the audience’s attention. Effective speech writing involves research and the generation of new ideas. Toastmasters International and the Writing Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill provide valuable resources for honing English and verbal skills.

Clarity and Purpose of the Speech

Achieving clarity, authenticity, and empathy defines a good speech. Whether to persuade, inform, or entertain, the purpose of a speech is crucial. It involves crafting persuasive content with rich vocabulary and clear repetition. Successful speechwriting demands a thorough understanding of the audience and a compelling introduction. Balancing short and long sentences is essential for holding the audience’s attention. This process is a fusion of linguistics, psychology, and rhetoric, making it an art form with a powerful impact.

Identifying Target Audience

Tailoring the speechwriting process hinges on identifying the target audience. Their attention is integral to the persuasive content, requiring adaptation of the speechwriting process. A speechwriter conducts audience analysis to capture the audience’s attention, employing new york audience analysis methods. Ensuring a good introduction and adapting the writing process for the target audience are key features of a great speech. Effective speechwriters prioritize the audience’s attention to craft compelling and persuasive speeches.

Structuring Your Speech

The speechwriting process relies on a well-defined structure, crucial to both the speech’s content and the writing process. It encompasses a compelling introduction, an informative body, and a strong conclusion. This process serves as a foundation for effective speeches, guiding the speaker through a series of reasons and a persuasive speechwriting definition. Furthermore, the structure, coupled with audience analysis, is integral to delivering a great speech that resonates with the intended listeners.

The Process of Writing a Speech

Crafting a speech involves composing the opening line, developing key points, and ensuring a strong start. Effective speech writing follows a structured approach, incorporating rhetorical questions and a compelling introduction. A speechwriter’s process includes formulating a thesis statement, leveraging rhetorical questions, and establishing a good start. This process entails careful consideration of the audience, persuasive language, and engaging content. The University of North Carolina’s writing center emphasizes the significance of persuasion, clarity, and concise sentences in speechwriting.

Starting with a Compelling Opener

A speechwriting process commences with a captivating opening line and a strong introduction, incorporating the right words and rhetorical questions. The opening line serves as both an introduction and a persuasive speech, laying the foundation for a great speechwriting definition. Additionally, the structure of the speechwriting process, along with audience analysis, plays a crucial role in crafting an effective opening. Considering these elements is imperative when aiming to start a speech with a compelling opener.

Developing the Body of the Speech

Crafting the body of a speech involves conveying the main points with persuasion and precision. It’s essential to outline the speechwriting process, ensuring a clear and impactful message. The body serves as a structured series of reasons, guiding the audience through the content. Through the use of short sentences and clear language, the body of the speech engages the audience, maintaining their attention. Crafting the body involves the art of persuasion, using the power of words to deliver a compelling message.

Crafting a Strong Conclusion

Crafting a strong conclusion involves reflecting the main points of the speech and summarizing key ideas, leaving the audience with a memorable statement. It’s the final chance to leave a lasting impression and challenge the audience to take action or consider new perspectives. A good conclusion can make the speech memorable and impactful, using persuasion and English language effectively to drive the desired response from the audience. Toastmasters International emphasizes the importance of a strong conclusion in speechwriting for maximum impact.

Techniques for Engaging Speech Writing

Engage the audience’s attention using rhetorical questions. Create a connection through anecdotes and personal stories. Emphasize key points with rhetorical devices to capture the audience’s attention. Maintain interest by varying sentence structure and length. Use visual aids to complement the spoken word and enhance understanding. Incorporate NLP terms such as “short sentences,” “writing center,” and “persuasion” to create engaging and informative speech writing.

Keeping the Content Engaging

Captivating the audience’s attention requires a conversational tone, alliteration, and repetition for effect. A strong introduction sets the tone, while emotional appeals evoke responses. Resonating with the target audience ensures engagement. Utilize short sentences, incorporate persuasion, and vary sentence structure to maintain interest. Infuse the speech with NLP terms like “writing center”, “University of North Carolina”, and “Toastmasters International” to enhance its appeal. Engaging content captivates the audience and compels them to listen attentively.

Maintaining Simplicity and Clarity

To ensure clarity and impact, express ideas in short sentences. Use a series of reasons and specific points to effectively convey the main idea. Enhance the speech with the right words for clarity and comprehension. Simplify complex concepts by incorporating anecdotes and personal stories. Subordinate clauses can provide structure and clarity in the speechwriting process.

The Power of Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal cues, such as body language and gestures, can add emphasis to your spoken words, enhancing the overall impact of your speech. By incorporating visual aids and handouts, you can further augment the audience’s understanding and retention of key points. Utilizing a conversational tone and appropriate body language is crucial for establishing a genuine connection with your audience. Visual aids and gestures not only aid comprehension but also help in creating a lasting impression, captivat**ing** the audience with compelling visual elements.

The Role of Audience Analysis in Speech Writing

Tailoring a speech to the audience’s needs is paramount. Demographics like age, gender, and cultural background must be considered. Understanding the audience’s interests and affiliation is crucial for delivering a resonating speech. Content should be tailored to specific audience points of interest, engaging and speaking to their concerns.

Understanding Audience Demographics

Understanding the varied demographics of the audience, including age and cultural diversity, is crucial. Adapting the speech content to resonate with a diverse audience involves tailoring it to the different ways audience members process and interpret information. This adaptation ensures that the speech can effectively engage with the audience, no matter their background or age. Recognizing the importance of understanding audience demographics is key for effective audience analysis. By considering these factors, the speech can be tailored to meet the needs and preferences of the audience, resulting in a more impactful delivery.

Considering the Audience Size and Affiliation

When tailoring a speech, consider the audience size and affiliation to influence the tone and content effectively. Adapt the speech content and delivery to resonate with a large audience and different occasions, addressing the specific points of the target audience’s affiliation. By delivering a speech tailored to the audience’s size and specific points of affiliation, you can ensure that your message is received and understood by all.

Time and Length Considerations in Speech Writing

Choosing the appropriate time for your speech and determining its ideal length are crucial factors influenced by the purpose and audience demographics. Tailoring the speech’s content and structure for different occasions ensures relevance and impact. Adapting the speech to specific points and the audience’s demographics is key to its effectiveness. Understanding these time and length considerations allows for effective persuasion and engagement, catering to the audience’s diverse processing styles.

Choosing the Right Time for Your Speech

Selecting the optimal start and opening line is crucial for capturing the audience’s attention right from the beginning. It’s essential to consider the timing and the audience’s focus to deliver a compelling and persuasive speech. The right choice of opening line and attention to the audience set the tone for the speech, influencing the emotional response. A good introduction and opening line not only captivate the audience but also establish the desired tone for the speech.

Determining the Ideal Length of Your Speech

When deciding the ideal length of your speech, it’s crucial to tailor it to your specific points and purpose. Consider the attention span of your audience and the nature of the event. Engage in audience analysis to understand the right words and structure for your speech. Ensure that the length is appropriate for the occasion and target audience. By assessing these factors, you can structure your speech effectively and deliver it with confidence and persuasion.

How to Practice and Rehearse Your Speech

Incorporating rhetorical questions and anecdotes can deeply engage your audience, evoking an emotional response that resonates. Utilize visual aids, alliteration, and repetition to enhance your speech and captivate the audience’s attention. Effective speechwriting techniques are essential for crafting a compelling introduction and persuasive main points. By practicing a conversational tone and prioritizing clarity, you establish authenticity and empathy with your audience. Develop a structured series of reasons and a solid thesis statement to ensure your speech truly resonates.

Techniques for Effective Speech Rehearsal

When practicing your speech, aim for clarity and emphasis by using purposeful repetition and shorter sentences. Connect with your audience by infusing personal stories and quotations to make your speech more relatable. Maximize the impact of your written speech when spoken by practicing subordinate clauses and shorter sentences. Focus on clarity and authenticity, rehearsing your content with a good introduction and a persuasive central idea. Employ rhetorical devices and a conversational tone, ensuring the right vocabulary and grammar.

How Can Speech Writing Improve Your Public Speaking Skills?

Enhancing your public speaking skills is possible through speech writing. By emphasizing key points and a clear thesis, you can capture the audience’s attention. Developing a strong start and central idea helps deliver effective speeches. Utilize speechwriting techniques and rhetorical devices to structure engaging speeches that connect with the audience. Focus on authenticity, empathy, and a conversational tone to improve your public speaking skills.

In conclusion, speech writing is an art that requires careful consideration of various elements such as clarity, audience analysis, and engagement. By understanding the importance of speech writing and the role of a speech writer, you can craft effective speeches that leave a lasting impact on your audience. Remember to start with a compelling opener, develop a strong body, and end with a memorable conclusion. Engaging techniques, simplicity, and nonverbal communication are key to keeping your audience captivated. Additionally, analyzing your audience demographics and considering time and length considerations are vital for a successful speech. Lastly, practicing and rehearsing your speech will help improve your public speaking skills and ensure a confident delivery.

Expert Tips for Choosing Good Speech Topics

Master the art of how to start a speech.

Popular Posts

How to write a retirement speech that wows: essential guide.

June 4, 2022

The Best Op Ed Format and Op Ed Examples: Hook, Teach, Ask (Part 2)

June 2, 2022

Inspiring Awards Ceremony Speech Examples

November 21, 2023

Mastering the Art of How to Give a Toast

Short award acceptance speech examples: inspiring examples, best giving an award speech examples.

November 22, 2023

Sentence Sense Newsletter

- Speech Topics For Kids

- How To Write A Speech

How to Write a Speech: A Guide to Enhance Your Writing Skills

Speech is a medium to convey a message to the world. It is a way of expressing your views on a topic or a way to showcase your strong opposition to a particular idea. To deliver an effective speech, you need a strong and commanding voice, but more important than that is what you say. Spending time in preparing a speech is as vital as presenting it well to your audience.

Read the article to learn what all you need to include in a speech and how to structure it.

Table of Contents

- Self-Introduction

The Opening Statement

Structuring the speech, choice of words, authenticity, writing in 1st person, tips to write a speech, frequently asked questions on speech, how to write a speech.

Writing a speech on any particular topic requires a lot of research. It also has to be structured well in order to properly get the message across to the target audience. If you have ever listened to famous orators, you would have noticed the kind of details they include when speaking about a particular topic, how they present it and how their speeches motivate and instill courage in people to work towards an individual or shared goal. Learning how to write such effective speeches can be done with a little guidance. So, here are a few points you can keep in mind when writing a speech on your own. Go through each of them carefully and follow them meticulously.

Self Introduction

When you are writing or delivering a speech, the very first thing you need to do is introduce yourself. When you are delivering a speech for a particular occasion, there might be a master of ceremony who might introduce you and invite you to share your thoughts. Whatever be the case, always remember to say one or two sentences about who you are and what you intend to do.

Introductions can change according to the nature of your target audience. It can be either formal or informal based on the audience you are addressing. Here are a few examples.

Addressing Friends/Classmates/Peers

- Hello everyone! I am ________. I am here to share my views on _________.

- Good morning friends. I, _________, am here to talk to you about _________.

Addressing Teachers/Higher Authorities

- Good morning/afternoon/evening. Before I start, I would like to thank _______ for giving me an opportunity to share my thoughts about ________ here today.

- A good day to all. I, __________, on behalf of _________, am standing here today to voice out my thoughts on _________.

It is said that the first seven seconds is all that a human brain requires to decide whether or not to focus on something. So, it is evident that a catchy opening statement is the factor that will impact your audience. Writing a speech does require a lot of research, and structuring it in an interesting, informative and coherent manner is something that should be done with utmost care.

When given a topic to speak on, the first thing you can do is brainstorm ideas and pen down all that comes to your mind. This will help you understand what aspect of the topic you want to focus on. With that in mind, you can start drafting your speech.

An opening statement can be anything that is relevant to the topic. Use words smartly to create an impression and grab the attention of your audience. A few ideas on framing opening statements are given below. Take a look.

- Asking an Engaging Question

Starting your speech by asking the audience a question can get their attention. It creates an interest and curiosity in the audience and makes them think about the question. This way, you would have already got their minds ready to listen and think.

- Fact or a Surprising Statement

Surprising the audience with an interesting fact or a statement can draw the attention of the audience. It can even be a joke; just make sure it is relevant. A good laugh would wake up their minds and they would want to listen to what you are going to say next.

- Adding a Quote

After you have found your topic to work on, look for a quote that best suits your topic. The quote can be one said by some famous personality or even from stories, movies or series. As long as it suits your topic and is appropriate to the target audience, use them confidently. Again, finding a quote that is well-known or has scope for deep thought will be your success factor.

To structure your speech easily, it is advisable to break it into three parts or three sections – an introduction, body and conclusion.

- Introduction: Introduce the topic and your views on the topic briefly.

- Body: Give a detailed explanation of your topic. Your focus should be to inform and educate your audience on the said topic.

- Conclusion: Voice out your thoughts/suggestions. Your intention here should be to make them think/act.

While delivering or writing a speech, it is essential to keep an eye on the language you are using. Choose the right kind of words. The person has the liberty to express their views in support or against the topic; just be sure to provide enough evidence to prove the discussed points. See to it that you use short and precise sentences. Your choice of words and what you emphasise on will decide the effect of the speech on the audience.

When writing a speech, make sure to,

- Avoid long, confusing sentences.

- Check the spelling, sentence structure and grammar.

- Not use contradictory words or statements that might cause any sort of issues.

Anything authentic will appeal to the audience, so including anecdotes, personal experiences and thoughts will help you build a good rapport with your audience. The only thing you need to take care is to not let yourself be carried away in the moment. Speak only what is necessary.

Using the 1st person point of view in a speech is believed to be more effective than a third person point of view. Just be careful not to make it too subjective and sway away from the topic.

- Understand the purpose of your speech: Before writing the speech, you must understand the topic and the purpose behind it. Reason out and evaluate if the speech has to be inspiring, entertaining or purely informative.

- Identify your audience: When writing or delivering a speech, your audience play the major role. Unless you know who your target audience is, you will not be able to draft a good and appropriate speech.

- Decide the length of the speech: Whatever be the topic, make sure you keep it short and to the point. Making a speech longer than it needs to be will only make it monotonous and boring.

- Revising and practicing the speech: After writing, it is essential to revise and recheck as there might be minor errors which you might have missed. Edit and revise until you are sure you have it right. Practise as much as required so you do not stammer in front of your audience.

- Mention your takeaways at the end of the speech: Takeaways are the points which have been majorly emphasised on and can bring a change. Be sure to always have a thought or idea that your audience can reflect upon at the end of your speech.

How to write a speech?

Writing a speech is basically about collecting, summarising and structuring your points on a given topic. Do a proper research, prepare multiple drafts, edit and revise until you are sure of the content.

Why is it important to introduce ourselves?

It is essential to introduce yourself while writing a speech, so that your audience or the readers know who the speaker is and understand where you come from. This will, in turn, help them connect with you and your thoughts.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

TRY OUR FREE APP

Write your book in Reedsy Studio. Try the beloved writing app for free today.

Craft your masterpiece in Reedsy Studio

Plan, write, edit, and format your book in our free app made for authors.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Jul 24, 2023

6 Unbreakable Dialogue Punctuation Rules All Writers Must Know

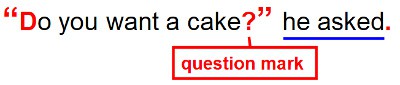

Dialogue punctuation is a critical part of written speech that allows readers to understand when characters start and stop speaking. By following the proper punctuation rules — for example, that punctuation marks almost always fall within the quotation marks — a writer can ensure that their characters’ voices flow off the page with minimal distraction.

This post’ll show you how to format your dialogue to publishing standards.

6 essential dialogue punctuation rules:

1. Always put commas and periods inside the quote

2. use double quote marks for dialogue (if you’re in america), 3. start a new paragraph every time the speaker changes , 4. use dashes and ellipses to cut sentences off, 5. deploy single quote marks used for quotes within dialogue, 6. don’t use end quotes between paragraphs of speech .

The misplacement of periods and commas is the most common mistake writers make when punctuating dialogue. But it’s pretty simple, once you get the hang of it. You should always have the period inside the quote when completing a spoken sentence.

Example: “It’s time to pay the piper.”

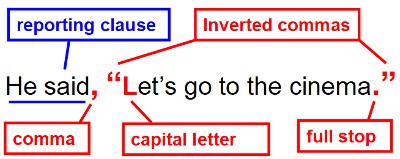

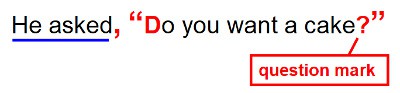

As you’ll know, the most common way to indicate speech is to write dialogue in quotation marks and attribute it to a speaker with dialogue tags, such as he said , she said, or Margaret replied, or chirped Hiroko . This is what we call “attribution” when you're punctuating dialogue.

Insert a comma inside the quotation marks when the speaker is attributed after the dialogue.

Example: “Come closer so I can see you,” said the old man.

If the speaker is attributed before the dialogue, there is a comma outside the quotation marks.

Example: Aleela whimpered, “I don’t want to. I’m scared.”

If the utterance (to use a fancy linguistics term for dialogue 🤓) ends in a question mark or exclamation point, they would also be placed inside the quotation marks.

Exception: When it’s not direct dialogue.

You might see editors occasionally place a period outside the quotation marks. In those cases, the period is not used for spoken dialogue but for quoting sentence fragments, or perhaps when styling the title of a short story.

Mark’s favorite short story was “The Gift of the Magi”.

My father forced us to go camping, insisting that it would “build character”.

Now that we’ve covered the #1 rule of dialogue punctuation, let’s dig into some of the more nuanced points.

In American English, direct speech is normally represented with double quotation marks.

Example : “Hey, Billy! I’m driving to the drug store for a soda and Charleston Chew. Wanna come?” said Chad

In British and Commonwealth English, single quotation marks are the standard.

Example: ‘I say, old bean,’ the wicketkeeper said, ‘Thomas really hit us for six. Let’s pull up stumps and retire to the pavilion for tea.’

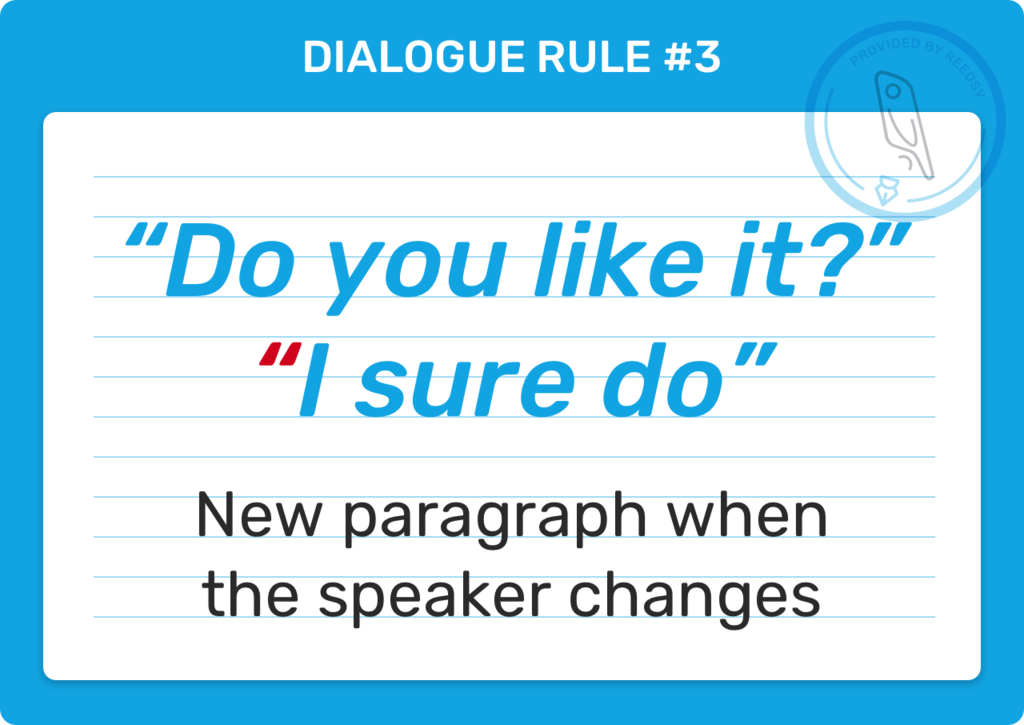

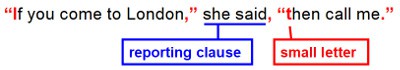

This is one of the most fundamental rules of organizing dialogue. To make it easier for readers to follow what’s happening, start a new paragraph every time the speaker changes, even if you use dialogue tags.

“What do you think you’re doing?” asked the policeman. “Oh, nothing, officer. Just looking for my hat,” I replied.

The new paragraph doesn’t always have to start with direct quotes. Whenever the focus moves from one speaker to the other, that’s when you start a new paragraph. Here’s an alternative to the example above:

“What do you think you’re doing?” asked the policeman. I scrambled for an answer. “Oh, nothing, officer. Just looking for my hat.”

FREE COURSE

How to Write Believable Dialogue

Master the art of dialogue in 10 five-minute lessons.

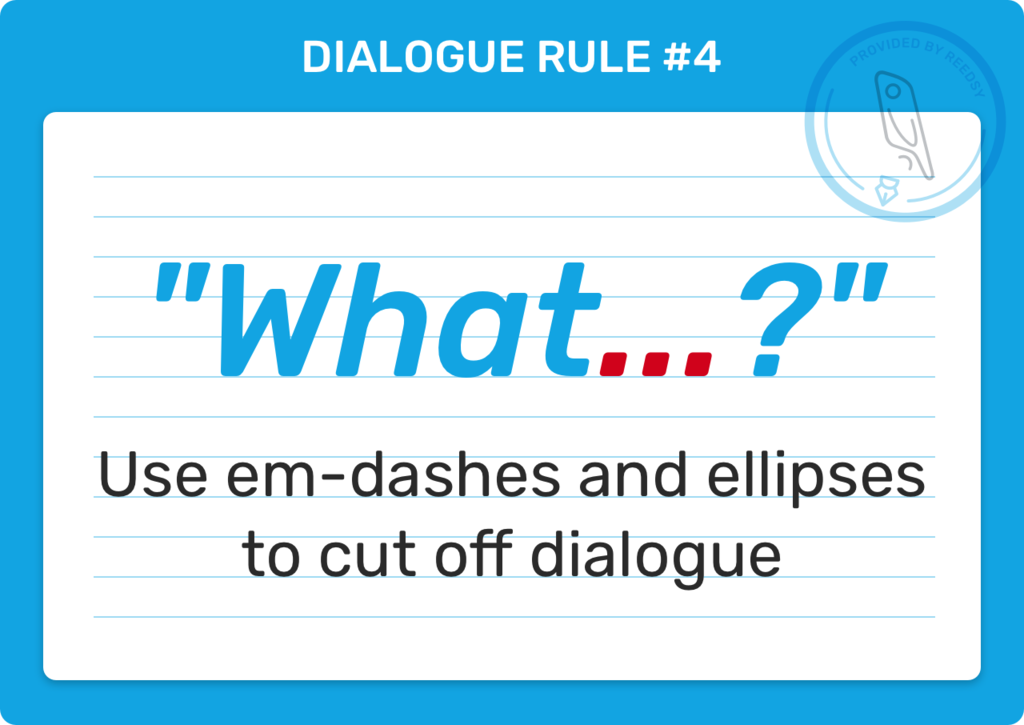

So far, all of the examples we’ve shown you are of characters speaking in full, complete sentences. But as we all know, people don’t always get to the end of their thoughts before their either trail off or are interrupted by others. Here’s how you can show that on the page.

Em-dashes to interrupt

When a speaking character is cut off, either by another person or a sudden event, use an em-dash inside the quotation marks. These are the longest dashes and can be typed by hitting alt-shift-dash on your keyboard (or option-shift-dash for Mac users).

“Captain, we only have twenty seconds before—” A deafening explosion ripped through the ship’s hull. It was already too late.

“Ali, please tell me what’s going—” “There’s no use talking!” he barked.

You can also overlap dialogue to show one character speaking over another.

Mathieu put his feet up as the lecturer continued. "Current estimates indicate that a human mission will land on Mars within the next decade—" "Fat chance." "—with colonization efforts following soon thereafter."

Sometime people won’t finish their sentences, and it’s not because they’ve been interrupted. If this is the case, you’ll want to…

Trail off with ellipses

You can indicate the speaker trailing off with ellipses (. . .) inside the quotation marks.

Velasquez patted each of her pockets. “I swear I had my keys . . .”

Ellipses can also suggest a small pause between two people speaking.

Dawei was in shock. “I can’t believe it . . .” “Yeah, me neither,” Lan Lan whispered.

💡Pro tip: The Chicago Manual of Style requires a space between each period of the ellipses. Most word processors will automatically detect the dot-dot-dot and re-style them for you — but if you want to be exact, manually enter the spaces in between the three periods.

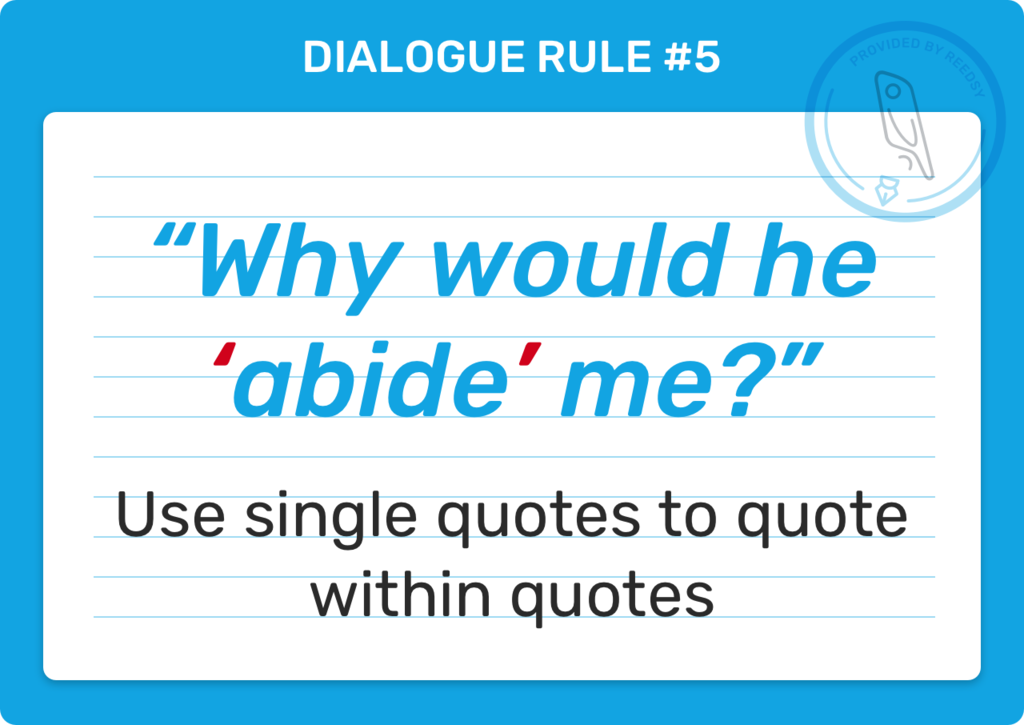

In the course of natural speech, people will often directly quote what other people have said. If this is the case, use single quotation marks within the doubles and follow the usual rules of punctuating dialogue.

“What did Randy say to you?” Beattie asked. “He told me, ‘I got a surprise for you,’ and then he life. Strange, huh?”

But what if a character is quoting another person, who is also quoting another person? In complex cases like this (which thankfully aren’t that common), you will alternate double quotation marks with single quotes.

“I asked Gennadi if he thinks I’m getting the promotion and he said, ‘The boss pulled me aside and asked, “Is Sergei going planning to stay on next year?”’”

The punctuation at the end is a double quote mark, followed by a single quote mark, followed by another double quote. It closes off:

- What the boss said,

- What Gennadi said, and

- What Sergei, the speaker, said.

Quoting quotes within quotes can get messy, so consider focusing on indirect speech. Simply relate the gist of what someone said:

“I pressed Gennadi on my promotion. He said the boss pulled him aside and asked him if I was leaving next year.”

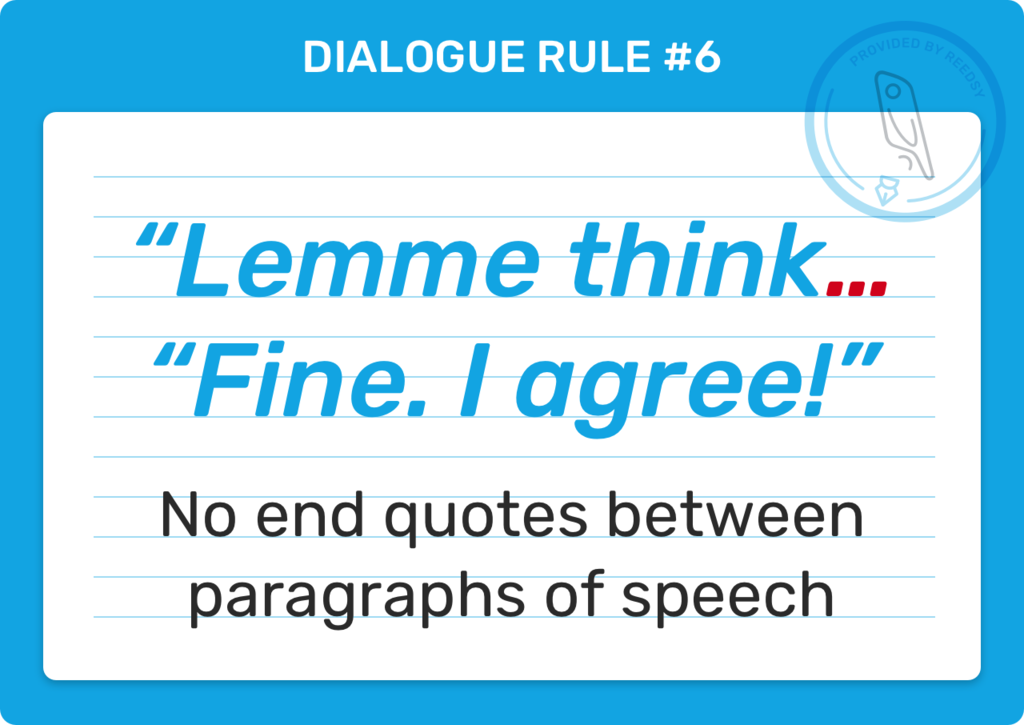

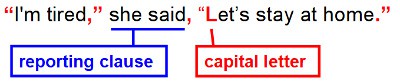

In all the examples above, each character has said fewer than 10 or 20 words at a time. But if a character speaks more than a few sentences at a time, to deliver a speech for example, you can split their speech into multiple paragraphs. To do this:

- Start each subsequent paragraph with an opening quotation mark; and

- ONLY use a closing quotation mark on the final paragraph.

"Would you like to hear my plan?" the professor said, lighting his oak pipe with a match. "The first stage involves undermining the dean's credibility: a small student protesst here, a little harassment rumor there. It all starts to add up. "Stage two involves the board of trustees, with whom I've been ingratiating myself for the past two semesters."

Notice how the first paragraph doesn't end with an end quote? This indicates that the same person is speaking in the next paragraph. You can always break up any extended speech with action beats to avoid pages and pages of uninterrupted monologue.

Want to see a great example of action beats breaking up a monologue? Check out this example from Sherlock Holmes.

Hopefully, these guidelines have clarified a few things about punctuating dialogue. In the next parts of this guide, you’ll see these rules in action as we dive into dialogue tags and look at some more dialogue examples here .

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

We made a writing app for you

Yes, you! Write. Format. Export for ebook and print. 100% free, always.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

More From Forbes

10 keys to writing a speech.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

“This is my time.”

That attitude will kill a speech every time.

You’ve probably sat through some lousy speeches. Despite the speakers’ renown, you eventually tuned them out over their self-indulgent tangents and pointless details. You understood something these speakers apparently didn’t: This was your time. They were just guests. And your attention was strictly voluntary.

Of course, you’ll probably deliver that speech someday. And you’ll believe your speech will be different. You’ll think, “I have so many important points to make.” And you’ll presume that your presence and ingenuity will dazzle the audience. Let me give you a reality check: Your audience will remember more about who sat with them than anything you say. Even if your best lines would’ve made Churchill envious, some listeners will still fiddle with their smart phones.

In writing a speech, you have two objectives: Making a good impression and leaving your audience with two or three takeaways. The rest is just entertainment. How can you make those crucial points? Consider these strategies:

1) Be Memorable: Sounds easy in theory. Of course, it takes discipline and imagination to pull it off. Many times, an audience may only remember a single line. For example, John F. Kennedy is best known for this declaration in his 1961 inaugural address: “And so, my fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you; ask what can do for your country.” Technically, the line itself uses contrast to grab attention. More important, it encapsulated the main point of Kennedy’s speech: We must sublimate ourselves and serve to achieve the greater good. So follow Kennedy’s example: Condense your theme into a 15-20 word epigram and build everything around it top-to-bottom.

There are other rhetorical devices that leave an impression. For example, Ronald Reagan referred to America as “a shining city on the hill” in speeches. The image evoked religious heritage, freedom, and promise. And listeners associated those sentiments with Reagan’s message. Conversely, speakers can defy their audience’s expectations to get notice. In the movie Say Anything , the valedictorian undercut the canned optimism of high school graduation speeches with two words: “Go back.” In doing so, she left her audience speechless…for a moment, at least.

Metaphors…Analogies…Surprise…Axioms. They all work. You just need to build up to them…and place them in the best spot (preferably near the end).

2) Have a Structure: Think back on a terrible speech. What caused you to lose interest? Chances are, the speaker veered off a logical path. Years ago, our CEO spoke at our national meeting. He started, promisingly enough, by outlining the roots of the 2008 financial collapse. Halfway through those bullet points, he jumped to emerging markets in Vietnam and Brazil. Then, he drifted off to 19th century economic theory. By the time he closed, our CEO had made two points: He needed ADD medication – and a professional speechwriter!

Audiences expect two things from a speaker: A path and a destination. They want to know where you’re going and why. So set the expectation near your opening on what you’ll be covering. As you write and revise, focus on structuring and simplifying. Remove anything that’s extraneous, contradictory, or confusing. Remember: If it doesn’t help you get your core message across, drop it.

3) Don’t Waste the Opening: Too often, speakers squander the time when their audience is most receptive: The opening. Sure, speakers have people to thank. Some probably need time to get comfortable on stage. In the meantime, the audience silently suffers.

When you write, come out swinging. Share a shocking fact or statistic. Tell a humorous anecdote related to your big idea. Open with a question – and have your audience raise their hands. Get your listeners engaged early. And keep the preliminaries short. You’re already losing audience members every minute you talk. Capitalize on the goodwill and momentum you’ll enjoy in your earliest moments on stage.

4) Strike the Right Tone: Who is my audience? Why are they here? And what do they want? Those are questions you must answer before you even touch the keyboard. Writing a speech involves meeting the expectations of others, whether it’s to inform, motivate, entertain, or even challenge. To do this, you must adopt the right tone.

Look at your message. Does it fit with the spirit of the event? Will it draw out the best in people? Here’s a bit of advice: If you’re speaking in a professional setting, focus on being upbeat and uplifting. There’s less risk. Poet Maya Angelou once noted, “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” Even if your audience forgets everything you said, consider your speech a success if they leave with a smile and a greater sense of hope and purpose. That’s a message in itself. And it’s one they’ll share.

5) Humanize Yourself: You and your message are one-and-the-same. If your audience doesn’t buy into you, they’ll resist your message too. It’s that simple. No doubt, your body language and delivery will leave the biggest impression. Still, there are ways you can use words to connect.

Crack a one liner about your butterflies; everyone can relate to being nervous about public speaking. Share a story about yourself, provided it relates to (or transitions to) your points. Throw in references to your family, to reflect you’re trustworthy. And write like you’re having a casual conversation with a friend. You’re not preaching or selling. You’re just being you. On stage, you can be you at your best .