Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

Search life-sciences literature (43,910,776 articles, preprints and more)

- Citations & impact

- Similar Articles

Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research.

Medsurg Nursing : Official Journal of the Academy of Medical-surgical Nurses , 01 Nov 2016 , 25(6): 435-436 PMID: 30304614

Abstract

Citations & impact , impact metrics, citations of article over time, article citations, professional soccer practitioners' perceptions of using performance analysis technology to monitor technical and tactical player characteristics within an academy environment: a category 1 club case study..

Davidson TK , Barrett S , Toner J , Towlson C

PLoS One , 19(3):e0298346, 07 Mar 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38452138 | PMCID: PMC10919864

The role of spirituality in pain experiences among adults with cancer: an explanatory sequential mixed methods study.

Miller M , Speicher S , Hardie K , Brown R , Rosa WE

Support Care Cancer , 32(3):169, 20 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38374447

"What about me?": lived experiences of siblings living with a brother or sister with a life-threatening or life-limiting condition.

Kittelsen TB , Castor C , Lee A , Kvarme LG , Winger A

Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being , 19(1):2321645, 25 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38404038 | PMCID: PMC10898268

Artificial intelligence adoption in extended HR ecosystems: enablers and barriers. An abductive case research.

Singh A , Pandey J

Front Psychol , 14:1339782, 24 Jan 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38327504 | PMCID: PMC10847531

Exploring the perceptions of patients with chronic respiratory diseases and their insights into pulmonary rehabilitation in Bangladesh.

Habib GMM , Uzzaman N , Rabinovich R , Akhter S , Ali M , Sultana M , Pinnock H , RESPIRE Collaboration

J Glob Health , 14:04036, 02 Feb 2024

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 38299780 | PMCID: PMC10832548

Similar Articles

To arrive at the top five similar articles we use a word-weighted algorithm to compare words from the Title and Abstract of each citation.

CREATING PROTOCOLS FOR TRUSTWORTHINESS IN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH.

J Cult Divers , 23(3):121-127, 01 Sep 2016

Cited by: 24 articles | PMID: 29694754

In response to Porter S. Validity, trustworthiness and rigour: reasserting realism in qualitative research. Journal of Advanced Nursing 60 (1), 79-86.

J Adv Nurs , 60(1):108-109, 01 Oct 2007

Cited by: 1 article | PMID: 17824944

Introduction to the special issue on quality of single-case experimental research in developmental disabilities.

Res Dev Disabil , 79:1-2, 21 Jun 2018

Cited by: 0 articles | PMID: 29937208

The qualitative orientation in medical education research.

Korean J Med Educ , 29(2):61-71, 29 May 2017

Cited by: 27 articles | PMID: 28597869 | PMCID: PMC5465434

Ethical and methodological issues in qualitative studies involving people with severe and persistent mental illness such as schizophrenia and other psychotic conditions: a critical review.

Carlsson IM , Blomqvist M , Jormfeldt H

Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being , 12(sup2):1368323, 01 Jan 2017

Cited by: 9 articles | PMID: 28901217 | PMCID: PMC5654012

Europe PMC is part of the ELIXIR infrastructure

Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Nursing, University of Texas Health San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, USA.

- PMID: 35929019

- DOI: 10.1177/08903344221116620

Keywords: anthropology; breastfeeding; ethnography; health services research; lactation; methodological rigor; qualitative methods; research paradigms; scientific method; theoretical orientation.

- Breast Feeding*

- Health Services Research*

- Qualitative Research

Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research

191 citations

80 citations

38 citations

30 citations

View 2 citation excerpts

Cites background from "Trustworthiness in Qualitative Rese..."

... It differs from statistical generalisation in quantitative studies, although they seem to have the same concept (Connelly, 2016). ...

... The first criterion—credibility—refers to the amount of researcher confidence in the achieved findings (Connelly, 2016). ...

26 citations

Related Papers (5)

Ask Copilot

Related papers

Related topics

Advertisement

Qualitative Research in Surgical Disciplines: Need and Scope

- Review Article

- Published: 16 May 2020

- Volume 83 , pages 3–8, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Jitendra Kumar Meena 1 ,

- Ashish Jakhetiya ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6891-6566 2 &

- Arun Pandey 2

372 Accesses

4 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

There is a deficient application of qualitative research methods in surgical specialties. The concerned researchers largely focus on quantitative estimates like: health risk, burden, surgical management and objective outcomes. Without qualitative assessment important aspects like: patient’s preparation, perception, satisfaction, coping ability, well-being and functional outcomes are not addressed. In quantitative research, evaluation of pre-set variables is done to primarily study the process and outcomes of healthcare interventions. However, in qualitative research, patient’s experience, emotions, self-image, decision-making, pain perception, coping mechanism and quality of life (QoL) can be assessed. With time, surgeons are emphasizing more on the importance of functional recovery and QoL after surgery in multidisciplinary board discussions, and before making treatment decisions. Qualitative research employs purposive sampling and a meticulous data collection using in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs) etc. Collected data is analysed using statistical tools post transcription and coding and is suitably presented. Like other research designs, qualitative methods also have uniform criteria’s and standards for quality management. Adoption of qualitative research is critical in filling gaps of patient and surgeon’s perspective and experience of process of surgical care for clinical policy decisions. Integration of qualitative evidence in shared decision-making process will further improve standards and practice of surgical care and enhance doctor-patient relationship.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

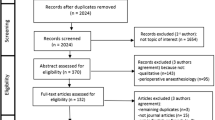

A systematic scoping review of published qualitative research pertaining to the field of perioperative anesthesiology

Mia Gisselbaek, Patricia Hudelson & Georges L. Savoldelli

What Factors Influence the Production of Orthopaedic Research in East Africa? A Qualitative Analysis of Interviews

Iain S. Elliott, Daniel B. Sonshine, … R. Richard Coughlin

Meta-synthesis of qualitative studies on patient perceptions and requirements during the perioperative period of robotic surgery

Shuang Wu, Chunzhi Yang, … Jie Yao

Frampton SB, Guastello S, Hoy L, Naylor M, Sheridan S, Johnston-Fleece M (2017). Harnessing evidence and experience to change culture: a guiding framework for patient and family engaged care National Academy Of Medicine 1-38

Hsing CY, Wong YK, Wang CP, Wang CC, Jiang RS, Chen FJ, Liu SA (2011) Comparison between free flap and pectoralis major pedicled flap for reconstruction in oral cavity cancer patients–a quality of life analysis. Oral Oncol 47(6):522–527

Article Google Scholar

Viana TSA, de Barros Silva PG, Pereira KMA, Mota MRL, Alves APNN, de Souza EF, Sousa FB (2017) Prospective evaluation of quality of life in patients undergoing primary surgery for oral cancer: preoperative and postoperative analysis. Asian Pacific Journal Of Cancer Prevention: APJCP 18(8):2093–2100

PubMed Google Scholar

Shauver MS, Chung KC (2010) A guide to qualitative research in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 126(3):1089–1097

Article CAS Google Scholar

Costa P, Cardoso JM, Louro H, Dias J, Costa L, Rodrigues R, Espiridião P, Maciel J, Ferraz L (2018) Impact on sexual function of surgical treatment in rectal cancer. International Braz J Urol 44(1):141–149

Sibeoni J, Picard C, Orri M, Labey M, Bousquet G, Verneuil L, Revah-Levy A (2018) Patients’ quality of life during active cancer treatment: a qualitative study. BMC Cancer 18(1):951

Vogel RI, Strayer LG, Ahmed RL, Blaes A, Lazovich D (2017) A qualitative study of quality of life concerns following a melanoma diagnosis. Journal of Skin Cancer 2017:2041872

US Department of Health and Human Services (2018). Qualitative methods in implementation science. National Institutes of Health. Bethesda, MD, USA: National Cancer Institute, 1–31

Sandelowski M, Leeman J (2012) Writing usable qualitative health research findings. Qual Health Res 22(10):1404–1413

Tracy SJ (2010) Qualitative quality: eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual Inq 16(10):837–851

Hannes, K. (2011). Chapter 4: critical appraisal of qualitative research. Supplementary guidance for inclusion of qualitative research in Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions. Version, 1, 1–14

Beaton DE, Clark JP (2009) Qualitative research: a review of methods with use of examples from the total knee replacement literature. JBJS 91(Supplement_3):107–112

Wright JG, McKeever P (2000) Qualitative research: its role in clinical research. Ann R Coll Physicians Surg Can 33:275–280

Google Scholar

Cohen D, Crabtree B (2006). Qualitative research guidelines project. Evaluative criteria . http://qualres.org/HomeGuid-3934.html . Accessed 2020 April 18

Polit DF, Beck CT (2009) Essentials of nursing research 7 th edition: appraising evidence for nursing practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 489–513

Guba EG, Lincoln YS (1994) Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handbook of qualitative research:105–117

Connelly LM (2016) Trustworthiness in qualitative research. Medsurg Nurs 25(6):435–437

Tong A, Morton RL, Webster AC (2016) How qualitative research informs clinical and policy decision making in transplantation: a review. Transplantation 100(9):1997–2005

Konecny, L. M. (2010). Quality of life, social support, and uncertainty among Latina and Caucasian breast cancer survivors: a comparative study. In Oncology Nursing Forum (Vol. 37, No. 1, p. 93). Oncology Nursing Society

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of preventive oncology, National Cancer Institute (NCI), AIIMS, New Delhi, India

Jitendra Kumar Meena

Department of surgical oncology, Geetanjali Medical College and hospital, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India

Ashish Jakhetiya & Arun Pandey

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ashish Jakhetiya .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Meena, J.K., Jakhetiya, A. & Pandey, A. Qualitative Research in Surgical Disciplines: Need and Scope. Indian J Surg 83 , 3–8 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-020-02280-1

Download citation

Received : 08 January 2020

Accepted : 24 April 2020

Published : 16 May 2020

Issue Date : February 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-020-02280-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Quality of life

- Functional outcome

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.10(9); 2023 Sep

- PMC10416061

Nurse leaders' perceptions of competence‐based management of culturally and linguistically diverse nurses: A descriptive qualitative study

Nina kiviniitty.

1 Research Unit of Health Sciences and Technology, University of Oulu, Oulu Finland

Suleiman Kamau

2 Department of Healthcare and Social Services, JAMK University of Applied Sciences, Jyvaskyla Finland

Kristina Mikkonen

3 Medical Research Center Oulu, Oulu University Hospital and University of Oulu, Oulu Finland

Mira Hammaren

Miro koskenranta, heli‐maria kuivila, outi kanste, associated data.

The dataset generated and analysed for the qualitative study is not publicly available due to the restrictions claimed in the document of the research permission.

To describe nurse leaders' perceptions of culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) nurses' competence‐based management.

A descriptive qualitative study of the competence‐based management of CALD nurses, from the perspectives of nurse leaders in three primary and specialised medical care organisations. This study followed the COREQ guidelines.

Qualitative semi‐structured individual interviews were conducted with 13 nurse leaders. Eligible interviewees were required to have management experience, and experience of working with or recruiting CALD nurses. Data were collected during November 2021–March 2022. The data were analysed using inductive content analysis.

Competence‐based management was explored in terms of competence identification and assessment of CALD nurses, aspects which constrain and enable competence sharing with them, and aspects which support their continuous competence development. Competencies are identified during the recruitment process, and assessment is based primarily on feedback. Organisations' openness to external collaboration and work rotation supports competence sharing, as does mentoring. Nurse leaders have a key role in continuous competence development as they organise tailored induction and training, and can indirectly reinforce nurses' work commitment and wellbeing.

Conclusion(s)

Strategic competence‐based management would enable all organisational competencies potential to be utilised more productively. Competence sharing is a key process for the successful integration of CALD nurses.

Relevance to Clinical Practice

The results of this study can be utilised to develop and standardise competence‐based management in healthcare organisations. For nursing management, it is important to recognise and value nurses' competence.

The role of CALD nurses in the healthcare workforce is growing, and there is little research into the competence‐based management of such nurses.

Patient or Public Contribution

No patient or public contribution.

1. INTRODUCTION

Many countries, particularly in the Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development countries (OECD), rely on internationally educated nurses to ease shortages of healthcare professionals (Hadziabdic et al., 2021 ; OECD, 2019 ; Primeau et al., 2021 ). The number of internationally educated nurses working in OECD countries increased by 20% between 2011 and 2016 (OECD, 2019 ), making the demographic profile of today's nursing workforce diverse in terms of nationalities, cultures and religions (Meretoja et al., 2015 ). Meretoja et al. ( 2015 ) point out that there is a growing need to continuously assess the competence of nurses. This is particularly important with regards to culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) nurses who have different backgrounds and experiences with respect to education, health care systems, nursing practices and cultures.

According to Primeau et al. ( 2021 ) organisations must ensure a healthy work environment to support the integration of CALD nurses. This includes taking measures to intervene against discrimination, and giving CALD nurses opportunities to attain their career goals and develop their competence (Primeau et al., 2021 ; Vartiainen, 2019 ). According to Lunden et al. ( 2017 ) nurse leaders need evidence‐based interventions to support shared learning, and they also need to create an infrastructure that facilitates competence development. Vartiainen ( 2019 ) states that the primary reasons for poor integration of CALD nurses are insufficient language skills and poor or limited opportunities to develop their competence. Bridging programmes have successfully facilitated the integration of CALD nurses into relevant work environments (Hadziabdic et al., 2021 ). Intraorganisational, socio‐cultural and professional development strategies and models which support CALD nurses' integration into healthcare organisations have also been established (Kamau et al., 2022 ).

CALD nurses' role in the Finnish healthcare workforce is growing, and there is little research on competence‐based management that focuses on CALD nurses. High levels competence among nursing staff has particular importance for mortality, patient care satisfaction, and the quality of care (Aiken et al., 2017 ), and quality of care depends on such competence (Church, 2016 ).

2. BACKGROUND

There are many terms for competence‐based management, including ‘competence‐based human resource management’, ‘competence management’ and ‘competency‐based management’, which are used interchangeably (Gunawan et al., 2019 ). Competence‐based management is a form of knowledge management which, according to Ollila ( 2013 ) entails a comprehensive strategy for managing the knowledge, abilities and experiences available within an organisation, and guiding where they are deployed. In this study, the term CALD nurse is used to refer both to nurses who are foreign‐born and were educated in either their home country or Finland, and to children of immigrants who were educated in Finland (Guler, 2022 ).

Competence has been defined in numerous ways and there is no universally accepted definition of it within nursing practice (e.g. Church, 2016 ). In general terms, competence can be defined as the management and practical application of knowledge and skills that are required at work (Ollila, 2013 ). One characteristic of professional competence is its dependency on context: as Nagelsmith ( 1995 ) states, ‘being able to demonstrate competence in a given content area in one context does not guarantee competence in a different context’. Meretoja, Leino‐Kilpi, and Kaira ( 2004 ) defined competence as ‘functional adequacy and capacity to integrate knowledge and skills to attitudes and values into specific contextual situations of practice’. The current study uses this definition of competence, because it takes into consideration its contextual nature.

Berio and Harzallah ( 2007 ) proposed that competence‐based management includes four processes: competence identification, competence assessment, competence acquisition and competence usage. Competence identification refers to recruitment and selection as the system for placing the right person in the right job based on their competence (Gunawan et al., 2022 ). Competence assessment concerns when and how individuals' acquired competencies are evaluated, and how an organisation assesses whether or not its employees have the specific competencies required to do their work. The acquisition of competencies should be responsible for deciding when to acquire competencies (Berio & Harzallah, 2007 ). One dimension of competence‐based management is career planning and development, as this enables the organisation to create opportunities for professional growth. This requires that the competencies needed are reviewed, and potential career goals are identified (Gunawan et al., 2022 ). Palacios‐Marqués et al. ( 2013 ) emphasise that successfully implemented competence‐based management can measure and improve employees' competences, and subsequently develop employees' careers. Using a competence‐based approach leaders identify any gaps between required and acquired competencies, identify employees who hold key competencies and decide who should attend training to acquire new ones (Berio & Harzallah, 2007 ). Hence, one dimension of competence‐based management is enhancing and developing employees' knowledge, skills and attitudes through training and evaluation (Gunawan et al., 2022 ). Leaders play a key role in supporting shared learning and creating an infrastructure that facilitates competence development (Lunden et al., 2017 ).

3. THE STUDY

3.1. aim and research question.

The aim of this study was to describe nurse leaders' perceptions of competence‐based management of CALD nurses. This study describes how leaders identify and assess competence, and support the continuous competence development of CALD nurses. The research question is: What do nurse leaders perceive to be involved in competence‐based management of CALD nurses?

4.1. Design

This is a descriptive qualitative study of CALD nurses' competence‐based management from the perspectives of nurse leaders, which was conducted in three primary and specialised medical care organisations. It followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines (Tong et al., 2007 ).

4.2. Sampling and recruitment

Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants, who were selected systematically based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) line‐manager or leader status, (2) at least 1 year's work experience and (3) experience working with or recruiting CALD nurses. This study was conducted in three primary and specialised medical care organisations in Finland. Participants were sought by sending out an introductory email to all nurse leaders in the participating organisations. Nurse leaders who responded and met the inclusion criteria received an email with further information on the study and an explanation that their participation would be voluntary. The researcher provided participants with information about the aim and purpose of the study. After this, an interview time was agreed upon. All participants ( n = 13) had experience of working with CALD nurses, and almost everyone ( n = 11) had at least a year's experience of leading a multicultural work community. Participants had leadership experience ranging from one to 20 years, the average being 7 years. Participants worked in home care ( n = 3), palliative care ( n = 3), and primary ( n = 3) or special healthcare wards ( n = 4). Study participants ranged from 38 to 63 years of age.

4.3. Data collection

Semi‐structured interviews were conducted by two researchers (NK, SK), with individual participants. The researchers had no prior relationship with the interviewees. One researcher was a female health science masters' student, and the other was a male nursing lecturer (PhD nursing student). Before the interviews, participants were asked to provide their background information (age, gender, work experience, education, work organisation and title) via a Webropol survey. Interviews were guided by pre‐determined themes. Interview questions were based on previous research into competence, knowledge and competence‐based management, by Meretoja, Isoaho, and Leino‐Kilpi ( 2004 ), Ollila ( 2013 ) and Orzano et al. ( 2008 ). The aim of the questions was to allow participants to openly convey their points of view (Tong et al., 2007 ) (Table 1 ).

Semi‐structured interview guide.

Abbreviation: CALD, culturally and linguistically diverse.

Nurse leaders were interviewed one by one, using Microsoft Teams. Interviews were audio‐recorded and the recordings stored confidentially. Before the actual interviews, the questions were discussed and evaluated with the research group which has comprehensive knowledge about the research topic. Themes and questions were defined drawing on their feedback, and the final guide for the actual interviews was formed. For this reason, no pilot interview was conducted. The length of the interviews varied from 35 to 65 min. The current roles of interviewees were head nurse, assistant head nurse or nurse manager. Data collection took place between November 2021 and March 2022. It was anticipated that participating nurse leaders would provide comprehensive insights during the interviews, and they did indeed generate rich data. During the data collection process attention was paid to achieving data saturation, and this helped inform decisions about the final sample size (Kyngäs et al., 2019 ). Every nurse leader who responded to the interview invitation was interviewed, and because saturation was achieved no additional participants were recruited. Transcription of the interviews yielded 198 pages of written data. The first author kept all the data in password‐protected computer files.

4.4. Data analysis

Inductive content analysis was used because previous research knowledge on the subject in question is limited and scattered (Kyngäs et al., 2019 ). Data were analysed by the first author and cross‐checked with co‐authors to enhance the credibility and confirmability of the findings (Cope, 2014 ). All the collected data were analysed inductively, and categories were identified through this analysis. First, the transcribed data were reviewed several times to build familiarity with the data, identify meanings and develop an understanding of the text. The chosen unit of analysis was the sentence, and all sentences related to the research question were marked to reduce the volume of data. Only the transcribed text was analysed. Sentences were grouped into sub‐categories, which were then grouped into categories and main categories relating to the research question (Kyngäs et al., 2019 ). Categories emerged throughout the inductive analysis process, and were combined where there were similarities. The interviewers (NK, SK) had regular meetings with the research group during data collection and analysis and shared initial results.

4.5. Ethical considerations

Research permits were granted from all organisations participating in the study (Medical Research Act 488/ 1999 , 295/2004, 794/2010). No vulnerable groups were involved in this study (World Medical Association, 2013 ). Participants were asked to give their informed consent to participate via a Webropol survey. Participation was voluntary, and participants had the right to refuse to participate in the study or withdraw their agreement at any time, without penalisation (World Medical Association, 2013 ). Private information about the participants was protected and handled confidentially (Polit & Beck, 2017 ).

5. FINDINGS

Nurse leaders' perceptions fell into three main categories: (1) identifying and assessing CALD nurses' competence, (2) constraining and enabling aspects of competence sharing and (3) supporting aspects for continuous competence development of CALD nurses. Table 2 sets out the 14 categories and 73 sub‐categories which comprise these main categories.

Nurse leaders' perceptions of culturally and linguistically diverse nurses' competence‐based management: overview of main categories, categories and sub‐categories.

5.1. Identifying and assessing CALD nurses' competence

Nurse leaders generally perceived that competence requirements are the same for CALD nurses as for native nurses. Education or registration in Finland was seen as a key indicator that CALD nurses are competent to work in Finland, and helped their integration into the Finnish healthcare organisation. Further, several years of work experience in Finland was seen as a strong indicator that a CALD nurse is competent.

Finnish language skills were emphasised as a key competence. Nurse leaders expected nurses to have adequate Finnish language skills, both in writing and for understanding essential concepts and instructions. Language skills were identified and assessed during the recruitment process, mainly through interviews. Practical work also gave an indication of a nurse's language skills and readiness to work in the organisation. Nurse leaders found it challenging to assess CALD nurses' language skills thoroughly because, although they may be able to converse easily about day‐to‐day things, limits to their understanding only become apparent in the course of practical work. To detect such insufficient language competence, nurse leaders made a point of having frequent conversations with CALD nurses. Nurse leaders expected CALD nurses to ask for help and work independently. Other competence requirements included basic nursing skills, comprehensive knowledge (e.g. about endemic diseases), interaction skills (e.g. patient care continuance and guidance competence), decision‐making skills, medical and pharmaceutical competence, and ethical competence. Nurse leaders felt that CALD nurses are often good at basic nursing but lack skills in carrying out more demanding tasks such as organising follow‐up care.

…often they (CALD nurses) have competence for basic nursing tasks…but when they have to guide patients' home care or interview incoming patients…sometimes they have to ask colleagues for help… (I5)

Nurse leaders perceived that CALD nurses' educational background and work experience are useful indicators of how much induction, guidance and training individuals may need. CALD nurses are also responsible for evaluating their own competence and what kind of induction she/he may need.

CALD nurses' theoretical knowledge and practical skills are assessed with reference to the same medical licences as other nurses, and employers do not usually provide them with any extra language courses. If a CALD nurse passes the medical licence this is taken as an indicator that their Finnish language skills are adequate. Nurse leaders explained that they ensure nurses are competent in terms of theoretical knowledge and practical skills through regular discussions and feedback rather than using a particular performance indicator. Some nurse leaders perceived that a performance indicator would be fairer to everyone. However, although nurse leaders recognised that exams could have been used to establish CALD nurses' competence, this approach was seen as insufficient. Instead, other methods such as simulations, online courses and skills demonstrations are used to assess competence within the relevant organisations.

Nurse leaders are able to observe the individual attributes of CALD nurses on the job, and identify their competencies through practical experience. According to nurse leaders, individual attributes include attitude and approach, service orientation, adaptability and skills, personality, initiative and motivation, interaction skills, resilience, diligence, sense of responsibility and commitment to the work. Nurse leaders assess these individual attributes using feedback from colleagues and patients, personal observations and discussions with CALD nurses. Such discussions are often spontaneous, for instance involving a nurse leader asking a CALD nurse how they are doing and whether they have any needs or questions in mind. During recruitment having a ‘suitable’ personality and showing initiative, for example, learning the language, are important considerations as they indicate a nurse's potential for professional development. Recruitment decisions are also affected by ‘feelings’ about the person which are formed during the interaction with them. CALD nurses are recruited through the normal recruitment channel and they encounter the same processes as any other job applicant. Nonetheless, nurse leaders perceived that CALD nurses still face preconceptions that affect their employment.

…and then they show us (in practical training) that they are able to work here, and able to work in our community. And that gives us a quite good feeling about the person. (I2)

On an organisational level, nurse leaders experienced that competence is not evaluated or monitored systematically. However, they referred to other organisational concerns, such as preventing malpractice, which effectively prompt them to ensure that nurses are competent.

According to nurse leaders, CALD nurses' competence is assessed and developed on the job based on feedback from colleagues and patients or customers. Recommendations from colleagues also serve to reaffirm the assessment of CALD nurses' competence. Nurse leaders highlighted that CALD nurses' attitudes are a key factor in their successful integration into the Finnish healthcare organisations. Aside from nursing competence, every CALD nurse should have Finnish language skills and knowledge of the culture, and some level of understanding of the organisational structure in which they work.

5.2. Constraining and enabling aspects of competence sharing

Openness within organisations' enables competence to be shared as nurse leaders perceived that, for example, collaboration with other units is a good way to receive guidance and share up‐to‐date knowledge. Further, practices such as work or team rotation can support the spread of competencies and distribution of tacit knowledge. It is important for CALD nurses to work in different places to maintain, share and improve competence. Further, CALD nurses' active participation in sharing their own expertise and being inquisitive was seen to be important. For example, many nurse leaders stated that during work or team rotation CALD nurses face different professional situations:

…when a nurse rotates teams, everyone will face certain things. (I1)

Nurse leaders emphasised that support from colleagues is essential for successful integration and competence sharing. Problems are often reflected together in the work community, and novice nurses rely on more experienced ones. Sharing new knowledge in meetings and patient cases with colleagues are concrete ways to share competence. Therefore, nurse leaders felt that a dialogical work community can be seen as an important enabling factor for competence sharing. Constraining factors on CALD nurses' competence sharing include the reserved mindset that some colleagues have towards CALD nurses, and the relative scarcity of other CALD nurses. Nurse leaders felt that they could create a more open and receptive working atmosphere. To enable competence sharing the work community should be approachable and receptive towards different cultures. Further, a multicultural work community was seen to be an enabling factor for CALD nurses' integration as they benefit from peer support from other CALD nurses:

I know it's tough to come to a new country and start working in a totally new cultural environment, but when you see that someone has made it and happily works here, I think that must add to their motivation. (I13)

In terms of induction, the nurse leaders expressed that the starting point is the same rules and code of conduct apply for everyone. Right from the start, CALD nurses are expected to do the same tasks as any nurse. Induction was seen as an ongoing process and some organisations also offer mentoring. Many leaders would like CALD nurses to have a mentor or support person to turn to when needed. In organisations that practise mentoring, experienced tutor nurses were responsible for inducting CALD nurses. Induction was tailored in a way that CALD nurses are mentored by a familiar mentor for as long as needed. It was pointed out that mentor nurses have an important role in giving support and deeper understanding of challenges such as confronting grief, and they are usually the most experienced nurses.

…mentor nurses have a more comprehensive role in giving support and deeper understanding of nursing… in our ward especially understanding patients' relatives, guiding them, and confronting grief. You can't learn it all from books…we share our feelings, and mentor nurses or experienced nurses can help in that. (I7)

Research participants expressed that when a nurse leader and work community is keen to learn and curious to hear about different kinds of practices from CALD nurses, this supports competence sharing. According to our findings, nurse leaders' individual attributes also have an influence on competence sharing, and leaders should be receptive and approachable. Good language skills and attendance helps CALD nurses' induction, and a lack of these limits interaction with other colleagues. The examples set by nurse leaders were seen to play a vital role in how receptive the work community was towards new ideas and practices. The nurse leader can create an atmosphere in which a CALD nurse (or anyone) can ask questions. Professional guidance and nurse leaders' actions can also support the creation of an open atmosphere. It was stated that nurse leaders should encourage staff to share knowledge and, for example, planned interviews can help distribute tacit knowledge. Hence, nurse leaders can strategically enable competence sharing. Nurse leaders' approach towards CALD nurses may be affected by their own experiences of different cultures. Interviewees felt that nurse leaders need more cultural understanding and education, because preconceptions towards CALD nurses can affect their employment.

Surely, nurse leaders' open‐mindedness and exemplary plays a role in how receptive the work community is towards new ideas and practices. (I6)

5.3. Supporting aspects for continuous competence development of CALD nurses

Nurse leaders recognised that working life has changed and people tend to switch jobs more frequently. How motivated CALD nurses are, which may be demonstrated by taking the initiative to learn the language and maintain their skills, has an impact on their continuous competence development. To improve their language skills, nurse leaders thought that CALD nurses should use Finnish as much as possible, at home and at work. In some organisations CALD nurses are less able to carry out independent tasks if their language skills are not good enough. Some interviewees perceived that the main responsibility for maintaining competence lies with the worker, while others saw the development and verification of competence, for example, through training, as an organisational responsibility.

Continuous competence development relies on nurse leaders being competent themselves, and open to recruiting CALD nurses. During orientation an appropriate induction is planned based on CALD nurses' needs and experience. Nurse leaders reported that they often arrange longer induction for CALD nurses than for other new recruits, and ensure that their competence development is focused on functions of their unit. Interviewees felt it was important that the nurse leader is approachable, supports evidence‐based practices and gives clear instructions. Nurse leaders had experienced CALD nurses needing more support from them than native nurses need, for example in independent decision‐making. Interviewees suggested that one concrete way to support CALD nurses is to have discussions with them more frequently. This demands interaction skills and emotional intelligence from the leader.

I offer work to CALD nurses, and openly encourage their applications and opportunities to work here (I1)

…I assume that it would be worthwhile…to be able to employ CALD nurses, that we would offer them tailored job descriptions in the beginning. (I3)

According to nurse leaders, work commitment and well‐being are factors which support continuous competence development. Nurse leaders perceived that work commitment is reinforced by investing in CALD nurses, for instance by offering permanent jobs, language training and other training opportunities. Nurses may be motivated to stay in the organisation if they are offered valuable education in a spirit of mutual commitment. For example, a nurse may commit to working in the organisation for 2 years, with some sanctions in place if they break this commitment. Continuous competence development is also supported by training programmes that run through the year for everyone. Nurse leaders said that CALD nurses' commitment to work can be strengthened by offering them areas of responsibility, professional guidance and benefits such as paid‐for access to exercise facilities. Nurse leaders felt that CALD nurses need extra support, particularly in the orientation stage. They also felt that nurse leaders can support work well‐being by providing nurses with opportunities to have an influence on their job, for instance through involving them in communal rota planning and having opportunities to work part‐time. In a broader sense, career path thinking can be seen as a glue that keeps people in the organisation.

We try to make them realise that we are really investing in them, getting them into permanent places, offering them more training… (I2)

… for instance, with areas of responsibility CALD nurses' commitment to work can be strengthened, so that giving them certain tasks might enhance their motivation to stay in that workplace. (I4)

Nurse leaders perceived that continuous competence development can be supported by giving written instructions, and that patient treatment or care processes should be clearly described. They said that lean thinking has been considered: for example workstations and storage areas are planned to be similar across all units. This was explained as a way of facilitating employees' orientation when they work in different units, and as a support to continuous competence development. Nurse leaders also expressed that knowledge should be distributed among many people, and areas of responsibility should not rest on a single individual.

In addition, career path thinking was seen to support continuous competence development. Nurse leaders perceived that career path development depended on support from senior management. They felt that senior management should provide and enable training, up‐to‐date information and sufficient resources. Nurse leaders perceived that varied practical training and work experience opportunities support CALD nurses in understanding relevant work settings in Finland and following their preferred career paths. Career path development is reviewed during development discussions which are held at least annually. Interviewees' perceptions about the career path process varied somewhat. The nurse leaders perceived that job descriptions and competence requirements should be similar for everyone and that professional competence is developed by offering challenges. They felt that job descriptions could be less demanding at the beginning, and that CALD nurses' career path could proceed from less to more demanding wards, through mutual understanding that their competence is adequate.

6. DISCUSSION

This study shows that the identification and assessment of CALD nurses' competence, competence sharing, and continuous competence development are supported by good competence‐based management practice. Previous studies (e.g. Gunawan et al., 2022 ; Palacios‐Marqués et al., 2013 ) have identified similar themes in competence‐based management, although there are few studies focusing on CALD nurses. These studies provide evidence that successfully implemented competence‐based management can measure and improve employees' competences, and subsequently develop employees' careers (Gunawan et al., 2019 ; Palacios‐Marqués et al., 2013 ). In addition to better employee outcomes, such as higher motivation, job well‐being and performance, effective competence‐based management can lead to better organisational and financial outcomes. Improved quality of care, patient safety and patient satisfaction are generally accepted as positive outcomes of competence‐based management (Gunawan et al., 2019 ). Strategic competence‐based management aims to promote action that develops a strategic way of thinking, and that will lead to improved productivity. It is based on collective values and goals (Ollila, 2013 ). Collective competence is an important component of competence‐based management, as competent practitioners can form an incompetent and ineffective team and, by the same token, a team may function competently despite being made up of incompetent practitioners (Shinners & Franqueiro, 2017 ).

According to our results, competence is identified during the recruitment process, and competence assessment is based primarily on feedback, personal observations and discussions with CALD nurses. Previous studies have suggested that, for example, collective competence can be evaluated in terms of how the team manages patient care situations (Shinners & Franqueiro, 2017 ). In such cases, nurse leaders must ensure that team members are aware of their roles and responsibilities. Competence evaluation should be context‐specific and be carried out as an ongoing process (Shinners & Franqueiro, 2017 ). In this study, nurse leaders highlighted that many CALD nurses join as trainees, meaning that leaders and colleagues are able to see whether they are a good fit with the work community before they become staff members. In recruitment, having a ‘suitable’ personality and showing initiative, for example by learning the language, are important considerations, as they indicate the candidate's potential for professional development. In nursing, competence‐based management requires understanding of the skills and knowledge required for every post (Palacios‐Marqués et al., 2013 ). Recruitment and selection are fundamental steps towards achieving the organisation's goals (Gunawan et al., 2022 ). It should be based purely on merit, knowledge, skills, attitudes and education, without bias or discrimination. CALD nurses need to be offered continuous development opportunities to overcome cultural and linguistic challenges within the job (Gunawan et al., 2022 ; Primeau et al., 2021 ; Vartiainen, 2019 .) Nurse leaders perceived that CALD nurses still face preconceptions that affect their employment.

The findings of this study suggest that openness on the part of organisations supports competence sharing and, in turn, competence development by CALD nurses. In this study, external collaboration and work or team rotation were seen to enable competence sharing. As Palacios‐Marqués et al. ( 2013 ) has highlighted, leaders should promote practices such as employee rotation, interdepartmental projects, or the creation of multidisciplinary teams to improve competence sharing and organisational performance. Proactive knowledge transfer enables organisations to identify and capture the competencies of employees, develop their career paths and facilitate smooth transitions (Desarno et al., 2021 ).

Nurse leaders emphasised that a dialogical work community is essential to successful integration of staff members and competence sharing between them. This study found that, for instance, reflecting on problems or patient cases together, support from experienced colleagues, and sharing new knowledge in meetings, are concrete ways in which competence can be shared. As Shinners and Franqueiro ( 2017 ) have suggested, specific strategies such as interprofessional education events (simulation scenarios, role‐play and case study), need to be adopted to create competent teams. Mentoring is another factor which this study found to support competence. Mentoring was perceived as a good practice for supporting integration and competence sharing for CALD nurses. A number of previous studies have suggested that systematic educational interventions which enabled experienced nurses to teach, coach and mentor newer nurses facilitate the transfer of competence from experts to novices (e.g. Pohjamies et al., 2022 .)

In this study, nurse leaders highlighted the importance of initiative. For example, CALD nurses are expected and encouraged to practice Finnish language skills in their free time and at work. The courage to try new and more demanding tasks and even different wards, were also highlighted as ways of sharing and developing competence. However, as a previous study (Mikkonen et al., 2020 ) has shown, it is important to note that CALD nurses may feel vulnerable when they play a strong professional role, because of their minority status within the work context. This study's findings indicate that nurse leaders' example plays a vital role in how receptive the work community is towards new ideas and practices. The nurse leader creates an atmosphere in which a CALD nurse (or anyone) can ask questions. Indeed, as Lunden et al. ( 2017 ) suggested, nurse leaders need to make use of evidence‐based interventions to support shared learning, and create an infrastructure that facilitates competence development. Other studies have also found that organisations' atmosphere should be open, flexible, and supportive to colleagues and students: this can be supported by establishing various dialogical and reflective forums such as mentoring (Mikkonen et al., 2017 ). Organisational culture, and staff alignment to a shared vision about how they serve their customers, facilitates relevant processes and practices (Palacios‐Marqués et al., 2013 ).

This study indicates that nurse leaders' competence is important to continuous competence development, as they organise tailored induction and training for staff members. Consequently, continuous competence development requires managerial competence from the leaders. Nurse leaders can also indirectly enforce CALD nurses' work commitment and well‐being by offering them areas of responsibility, opportunities to influence their own job, mentoring and peer support, and personal support. Previous studies suggest that nurse leaders should provide novice nurses efficient training programmes and opportunities to engage in demanding nursing tasks early on, for instance working with competent experienced nurses (Meretoja et al., 2015 ). This study identified a specific challenge related to CALD nurses' language skills, as weaker language skills affect how fluently they can work with patients, and can also inhibit their career development. For instance, some CALD nurses stay at the novice level for a long time, and proceeding to the next competence level is hindered by their insufficient language skills.

In general, strengthening CALD nurses' competence starts at the organisational level. Sufficient resources for education, up‐to‐date information and time are all crucial to supporting continuous competence development. Previous studies provide evidence that strategic competence‐based management requires taking account of the operational preconditions and special characteristics of the work in question, and can eventually lead to a more flexible and innovative operational environment. Managers are responsible for creating the operational preconditions for productivity and quality. Consequently, competence‐based management requires managerial competence that is based on readiness, knowledge, skills, experience, motivation and setting a good example (Ollila, 2013 ).

6.1. Strengths and limitations of the study

The study was designed and carried out following the principles of trustworthiness according to Lincoln and Guba ( 1985 )'s framework. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) have been used to ensure the transparency and trustworthiness of the study (Tong et al., 2007 ).

The credibility of this study was strengthened by evaluating the guide for the interviews with the research group (Kyngäs et al., 2019 ). The risk of semi‐structured interviews steering participants' answers excessively was considered beforehand, and the interview themes were used as mere during the interview process.

Data analysis proceeded inductively, taking into account all the data collected, and categories were identified and derived from the data (Tong et al., 2007 ). The interviewers had regular meetings with the research group during data collection and analysis, and shared initial results. The research process and results have been reported here transparently to achieve sufficient transferability (Kyngäs et al., 2019 ). Further, transferability was enhanced by rich data from a representative sample of nurse leaders from primary and specialised healthcare levels within two regions in Finland (Connelly, 2016 ).

Saturation was achieved with the sample: this strengthens the reliability of the data (Kyngäs et al., 2019 ). Using two or more researchers to carry out data coding, analysis and interpretation would have improved this study's dependability. A table explaining the categorisation process is presented in the article. The study findings are also supported by earlier research (Kyngäs et al., 2019 ). Authentic citations and tables are included throughout the text and reflect all parts of the analytical process. Authentic citations link the results with the raw data and improve the authenticity of the study (Kyngäs et al., 2019 ).

6.2. Recommendations for further research

We suggest that further research is needed into how cultural diversity effects competence sharing and the working environment. We also suggest that nurse leaders' role in promoting the integration and continuous competence development of CALD nurses should be studied further.

7. CONCLUSIONS

This study has brought to light perceptions of competence‐based management, particularly during the orientation of CALD nurses when nurse leaders' role and practices for sharing competence are particularly important for their integration into the workplace. CALD nurses' competence is not managed systemically, and competence assessment is based on feedback from colleagues, mentors or patients. Competence levels of all nurses should be measured and assessed systematically. Nurses should also be informed about the competencies required of them. The findings of this study should be considered as an insight into CALD nurses' competence‐based management. With strategic competence‐based management, all potentially available competence could be utilised more productively. A dialogical work community and mentoring programmes can contribute to a supportive work environment, and relevant practices should be encouraged. By being more welcoming of CALD nurses, welcoming their experiences, and supporting their use of Finnish, it may be possible to ease current shortages of professional nursing staff.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualisation : Kiviniitty, Mikkonen, Kanste, Hammaren; Data curation : Kiviniitty, Koskenranta, Kamau; Formal Analysis : Kiviniitty; Funding acquisition : No funding; Investigation : Kiviniitty; Methodology : Kiviniitty, Mikkonen, Kamau, Kanste, Hammaren; Project administration : Mikkonen, Kuivila, Koskenranta; Resources : Kiviniitty; Supervision : Mikkonen, Kuivila, Hammaren, Kanste; Visualisation : Kiviniitty; Writing—original draft : Kiviniitty; Writing—review & editing : Kiviniitty, Kamau, Mikkonen, Kuivila, Koskenranta, Hammaren, Kanste.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not‐for‐profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflicts of interest declared among the participants.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is part of CultureExpert‐project. Oulu University is carrying out this project in collaboration with Oulu University of Applied Sciences and Lapland University of Applied Sciences.

Kiviniitty, N. , Kamau, S. , Mikkonen, K. , Hammaren, M. , Koskenranta, M. , Kuivila, H.‐M. , & Kanste, O. (2023). Nurse leaders' perceptions of competence‐based management of culturally and linguistically diverse nurses: A descriptive qualitative study . Nursing Open , 10 , 6479–6490. 10.1002/nop2.1899 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

- Aiken, L. H. , Sloane, D. , Griffiths, P. , Rafferty, A. M. , Bruyneel, L. , McHugh, M. , Maier, C. B. , Moreno‐Casbas, T. , Ball, J. E. , Ausserhofer, D. , & Sermeus, W. (2017). Nursing skill mix in European hospitals: Cross‐sectional study of the association with mortality, patient ratings and quality of care . BMJ Quality & Safety , 26 ( 7 ), 559–568. 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005567 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berio, G. , & Harzallah, M. (2007). Towards an integrating architecture for competence management . Computers in Industry , 58 ( 2 ), 199–209. 10.1016/j.compind.2006.09.007 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Church, C. D. (2016). Defining competence in nursing and its relevance to quality care . Journal for Nurses in Professional Development , 32 ( 5 ), E9–E14. 10.1097/NND.0000000000000289 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Connelly, L. M. (2016). Trustworthiness in qualitative research . Medsurg Nursing , 25 ( 6 ), 435–436. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cope, D. G. (2014). Methods and meanings: Credibility and trustworthiness of qualitative research . Oncology Nursing Forum , 41 ( 1 ), 89–91. 10.1188/14.ONF.89-91 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Desarno, J. , Perez, M. , Rivas, R. , Sandate, I. , Reed, C. , & Fonseca, I. (2021). Succession planning within the health care organization: Human resources management and human capital management considerations . Nurse Leader , 19 ( 4 ), 411–415. 10.1016/j.mnl.2020.08.010 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guler, N. (2022). Teaching culturally and linguistically diverse students: Exploring the challenges and perceptions of nursing faculty . Nursing Education Perspectives , 43 ( 1 ), 11–13. 10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000861 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gunawan, J. , Aungsuroch, Y. , & Fisher, M. L. (2019). Competence‐based human resource management in nursing: A literature review . Nursing Forum , 54 ( 1 ), 91–101. 10.1111/nuf.12302 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gunawan, J. , Aungsuroch, Y. , Fisher, M. L. , McDaniel, A. M. , & Liu, Y. (2022). Competence‐based human resource management to improve managerial competence of first‐line nurse managers: A scale development . International Journal of Nursing Practice , 28 ( 1 ), e12936. 10.1111/ijn.12936 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hadziabdic, E. , Marekovic, A.‐S. , Salomonsson, J. , & Heikkilä, K. (2021). Experiences of nurses educated outside the European Union of a Swedish bridging program and the program's role in their integration into the nursing profession: A qualitative interview study . BMC Nursing , 20 ( 1 ), 7. 10.1186/s12912-020-00525-8 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kamau, S. , Koskenranta, M. , Kuivila, H. , Oikarainen, A. , Tomietto, M. , Juntunen, J. , & Mikkonen, K. (2022). Integration strategies and models to support transition and adaptation of culturally and linguistically diverse nursing staff into healthcare environments: An umbrella review . International Journal of Nursing Studies , 136 , 104377. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104377 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kyngäs, H. , Mikkonen, K. , & Kääriäinen, M. (2019). The application of content analysis in nursing science research . Springer International Publishing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lincoln, Y. S. , & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry . SAGE Publications. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lunden, A. , Teräs, M. , Kvist, T. , & Häggman‐Laitila, A. (2017). A systematic review of factors influencing knowledge management and the nurse leaders' role . Journal of Nursing Management , 25 , 407–420. 10.1111/jonm.12478 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Medical Research Act 488/1999, 295/2004, 794/2010. Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland. http://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/1999/en19990488

- Meretoja, R. , Isoaho, H. , & Leino‐Kilpi, H. (2004). Nurse competence scale: Development and psychometric testing . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 47 ( 2 ), 124–133. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03071.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Meretoja, R. , Leino‐Kilpi, H. , & Kaira, A. M. (2004). Comparison of nurse competence in different hospital work environments . Journal of Nursing Management , 12 , 329–336. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2004.00422.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Meretoja, R. , Numminen, O. , Isoaho, H. , & Leino‐Kilpi, H. (2015). Nurse competence between three generational nurse cohorts: A cross‐sectional study . International Journal of Nursing Practice , 21 , 350–358. 10.1111/ijn.12297 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mikkonen, K. , Elo, S. , Miettunen, J. , Saarikoski, M. , & Kaariainen, M. (2017). Clinical learning environment and supervision of international nursing students: A cross‐sectional study . Nurse Education Today , 52 , 73–80. 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.02.017 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mikkonen, K. , Merilainen, M. , & Tomietto, M. (2020). Empirical model of clinical learning environment and mentoring of culturally and linguistically diverse nursing students . Journal of Clinical Nursing , 29 ( 3–4 ), 653–661. 10.1111/jocn.15112 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nagelsmith, L. (1995). Competence: An evolving concept . The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing , 26 ( 6 ), 245–248. 10.3928/0022-0124-19951101-04 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- OECD, The Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development . (2019). Recent trends in international migration of doctors, nurses and medical students . OECD Publishing. 10.1787/5571ef48-en [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ollila, S. (2013). Productivity in public welfare services is changing: The standpoint of strategic competence‐based management . Social Work in Public Health , 28 ( 6 ), 566–574. 10.1080/19371918.2013.791524 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Orzano, J. , McInerney, C. R. , Scharf, D. , Tallia, A. F. , & Crabtree, B. F. (2008). A knowledge management model: Implications for enhancing quality in health care . Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology , 59 ( 3 ), 489–505. 10.1002/asi.20763 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Palacios‐Marqués, D. , Peris‐Ortiz, M. , & Merigó, J. M. (2013). The effect of knowledge transfer on firm performance . Management Decision , 51 ( 5 ), 973–985. 10.1108/MD-08-2012-0562 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pohjamies, N. , Haapa, T. , Kääriäinen, K. , & Mikkonen, K. (2022). Nurse preceptors' orientation competence and associated factors—A cross‐sectional study . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 78 , 4123–4134. 10.1111/jan.15388 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Polit, D. F. , & Beck, C. T. (2017). Nursing research. Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practise (10th ed.). Wolters Kluwer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Primeau, M. , St‐Pierre, I. , Ortmann, J. , Kilpatrick, K. , & Covell, C. L. (2021). Correlates of career satisfaction in internationally educated nurses: A cross‐sectional survey‐based study . International Journal of Nursing Studies , 117 , 103899. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103899 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shinners, J. , & Franqueiro, T. (2017). Individual and collective competence . The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing , 48 ( 4 ), 148–150. 10.3928/00220124-20160321-02 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tong, A. , Sainsbury, P. , & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups . International Journal for Quality in Health Care , 19 ( 6 ), 349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vartiainen, P. (2019). The paths of Filipino nurses to Finland: A study on learning and integration processes in the context of international recruitment [Dissertation, University of Tampere] . https://trepo.tuni.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/105048/978‐952‐03‐0937‐4.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y

- World Medical Association . (2013). Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects . Revised in 2013. https://www.wma.net/policies‐post/wma‐declaration‐of‐helsinki‐ethical‐principles‐for‐medical‐research‐involving‐human‐subjects/ [ PubMed ]

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research Medsurg Nurs. 2016 Nov;25(6):435-6. Author Lynne M Connelly. PMID: 30304614 No abstract available. MeSH terms Biomedical Research / standards* Data Accuracy* Humans Qualitative Research* ...

Using tables to enhance trustworthiness in qualitative research. Strategic Organization, 19(1), 113-133 ... Connelly L. M. (2016). Trustworthiness in qualitative research. Medsurg Nursing, 25(6), 435. PubMed. ... Smith J. (2015). Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evidence-Based Nursing, 18(2), 34-35. https://doi ...

Trustworthiness or rigor of a study refers to the degree of confidence in data, interpretation, and methods used to ensure the quality of a study (Pilot & Beck, 2014). In each study, researchers should establish the protocols and procedures necessary for a study to be considered worthy of consideration by readers (Amankwaa, 2016).

Dear Editor, The global community of medical and nursing researchers has increasingly embraced qualitative research approaches. This surge is seen in their autonomous utilization or incorporation as essential elements within mixed-method research attempts [1].The growing trend is driven by the recognized additional benefits that qualitative approaches provide to the investigation process [2], [3].

Medsurg nursing: official journal of the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses 25(6):435-436 ... To ensure 'trustworthiness' of the qualitative research process, specifically credibility ...

Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research. Connelly LM. Medsurg Nursing : Official Journal of the Academy of Medical-surgical Nurses, 01 Nov 2016, 25(6): 435-436 PMID: 30304614 . Share this article Share with email Share with twitter Share with linkedin Share with facebook. Abstract .

Sign in. Access personal subscriptions, purchases, paired institutional or society access and free tools such as email alerts and saved searches.

Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research. Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research J Hum Lact. 2022 Nov;38(4):598-602. doi: 10.1177/08903344221116620. Epub 2022 Aug 4. Author Rachel H Adler 1 Affiliation 1 School of Nursing, University of Texas Health San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, USA. PMID: 35929019 DOI: 10.1177 ...

Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research. Rachel H Adler. Published in Journal of Human Lactation 4 August 2022. Sociology. To be relevant, all research must be trustworthy. Although quips about statistics are often cynical—as numbers can be manipulated by those with an agenda—at least quantitative research has the facade of being ...

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

Trustworthiness in qualitative research. In their qualitative study on nurses' confusion and uncertainty with cardiac monitoring, Nickasch, Marnocha, Grebe, Scheelk, and Kuehl (2016) addressed trustworthiness in a number of ways. Trustworthiness or truth value of qualitative research and transparency of the conduct of the study are crucial to ...

Exploring faculty and preceptors' experiences and perceptions of teaching EBP in rehabilitation professions, namely occupational therapy, physical therapy and speech-language pathology, identified three overarching themes and corresponding strategies that referred to participants' perception of EBP as a complex process involving high-level ...

The research reported in the paper provides an important contribution to establishing trustworthiness in qualitative research by offering an innovative approach to promoting reflexivity. A strength in the research reported in this paper is the attention to methodical rigour when using established data collection approaches and questionnaires ...

This article is published in Medsurg nursing : official journal of the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses.The article was published on 2016-11-01 and is currently open access. It has received 402 citations till now. The article focuses on the topics: Qualitative research.

ENSURING TRUSTWORTHINESS IN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH Joko Gunawan1,2* ... enhancing the utility of qualitative research. Nursing outlook. May-Jun 1997;45(3):125-132. 3. Rolfe G. Validity, trustworthiness

Connelly LM (2016) Trustworthiness in qualitative research. Medsurg Nurs 25(6):435-437. PubMed Google Scholar Tong A, Morton RL, Webster AC (2016) How qualitative research informs clinical and policy decision making in transplantation: a review. Transplantation 100(9):1997-2005. Article Google Scholar

The criteria of trustworthiness, including credibility, dependability, confirmability, transferability, and authenticity ... Trustworthiness in qualitative research. Medsurg Nursing: Official Journal of the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses, 25 (6), 435-436.

Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research. Lynne M Connelly. Medsurg Nursing : Official Journal of the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses 2016 November. No abstract text is available yet for this article.

The research reported in the paper provides an important contribution to establishing trustworthiness in qualitative research by offering an innovative approach to promoting reflexivity. A strength in the research reported in this paper is the attention to methodical rigour when using established data collection approaches and questionnaires ...

Trustworthiness. Trustworthiness in this study was established using the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research Checklist 30 and naturalist methodology: truth-value, applicability, consistency, and neutrality. 31,32 Truth-value (credibility) was established by using triangulation of data sources and triangulation of data ...

My Research and Language Selection My Research Sign into My Research Create My Research Account English; Help and support Help and support. Support Center Find answers to questions about products, access, use, setup, and administration. Contact Us Have a question, idea, or some feedback? We want to hear from you.

Medsurg Nursing Official Journal of the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses 25(6): 435-436 2016. ISSN/ISBN: 1092-0811. ... (Cope, 2014). In this column, I will discuss the components of trustworthiness in qualitative research. Related References Adler, R.H. 2022: Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research Journal of Human Lactation: ...

Trustworthiness in qualitative research. Medsurg Nursing, 25 (6), 435-436. [Google Scholar] Cope, D. G. (2014). Methods and meanings: Credibility and trustworthiness of qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum , 41 (1 ... The application of content analysis in nursing science research. Springer International Publishing. [Google ...