- PAGE Blog Salon

- Forseeable Futures

- News & Press

- Action Research

I Am Who I Say I Am: Reclaiming Native American Identity through Visual Sovereignty

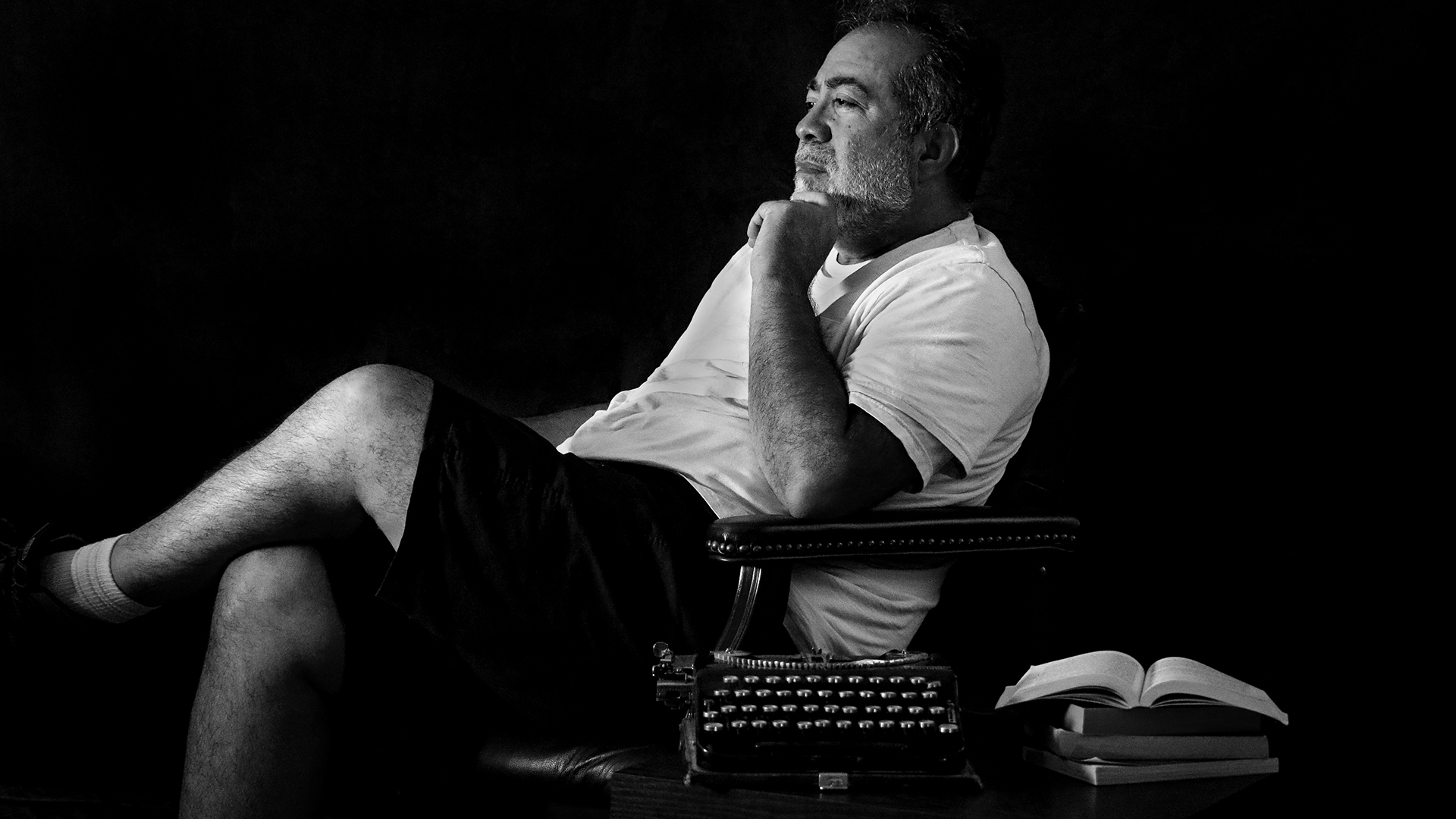

Writing and photography by haley rains (muscogee creek).

Feature Image description: Jace Naki’e (Numu [Northern Paiute] / Newe [Western Shoshone] / Hopi [Tobacco Clan]), Sacramento, CA.

The Maori filmmaker Merata Mita once said, “I’ve always felt strongly that our land gets taken, the fisheries and forests get taken, and in the same category is our stories. What we see on the screen is only the dominant, white, mono-cultural perspective on life… We need to see our own people up there. We need to be able to identify with our own race. We need to see each other up there, and we need to go out and do it.”

One of the greatest tragedies that Native American people have experienced — and continue to experience — is the silencing of our voices as a result of others speaking for us. This exclusionary practice severely diminishes our ability to control our own narratives.

In my publicly engaged scholarship, I engage in the practice of Visual Sovereignty, which can be defined as exercising the inherent power to govern oneself and control one’s own narrative (and the narrative of one’s people) via self-representation in film, media, performance, and photography.

For many Native American individuals, daily life hardly resembles that depicted in media and popular culture. When depicting Native Americans in media and popular culture, non-Natives present American Indians as savages, “vanishing” Indians, and impediments to American progress. These representations have established a model for depicting Native Americans, one which has become the standard for how non-Native Americans view indigenous people: horse-riding, feather-wearing, tee-pee-dwelling, mystical people of wild, unconquered territories.

In my public scholarship, I push back against inaccurate, oversimplified depictions of American Indians by non-Native filmmakers and in doing so, empower Native American people by helping them reclaim their indigenous identities.

By depicting Native American people in a more nuanced light, I show non-Native American audiences more multifaceted — more human — portrayals of Native American people, while also providing an opportunity for Native American audiences to identify with the complicated, layered characters we see on screen and in photographs — a privilege, historically, we have been denied.

By engaging in Visual Sovereignty, by way of publicly engaged scholarship, I bring new perspectives to America’s vision of Native American people — especially those located in the

American West — by giving a voice to the Native American experience.

Art, film, performance, and other forms of media are exceptionally influential components of any society; they reflect our customs, values, beliefs, histories, and the narratives by which we ascribe importance, determine power, and relegate certain populations to the margins of society. The stories we tell and the art we create reflect our interpretation of the world around us.

That is why it is critically important that Native American people are afforded the space within which we are free to express our own values, experiences, and identities and, subsequently, position them to be received — and celebrated — by American and global society.

I believe that asserting one’s right to self-definition by visually expressing one’s own experiences is a basic human right; therefore, publicly engaged scholarship that seeks to accurately represent Native American people and their diverse experiences contributes to empowerment and full participation of Native Americans in contemporary society.

Inspired by IA action research findings, the Public Scholar Conversation Cards and Organizing Culture Change Imagination Guide are pedagogic tools to inspire reflection and action.

Imagining America

- 207 3rd Street, Suite 120 Davis, CA 95616

- +1 530 297 4640

- [email protected]

Publications

- Joy of Giving Something (JGS) Fellowship

- Publicly Active Graduate Education (PAGE) Fellowship

- Local Events

- Cluster Organizing

- Leading and Learning Initiative

- Collective of Publicly Engaged Designers

- Assessing the Practices of Public Scholarship

- Creative Community Development

- Past Initiatives

- Host Campus

Funding has been provided by California Humanities and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) as part of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

- Native Narratives: The Representation of Native Americans in Public Broadcasting

Visual Sovereignty: Native-Created Public Media

- (Mis)Representations of Native Americans

- Termination, Relocation, and Restoration

- The American Indian Movement

- Native Americans in Contemporary News Media

As well as advocating for increased representation of Native Americans in mainstream media, Native American producers and filmmakers since the 1970s have created content that reflects the needs of their communities. Although Native programs address common stereotypes about Native cultures, they also embody new narratives that engage the past and present realities of contemporary Native peoples. Associate Professor of English Michelle Raheja defines this understanding of Native media as "visual ‘sovereignty" in which "Indigenous filmmakers and actors revisit, contribute to, borrow from, critique, and reconfigure" dominant narratives about their cultures. 65 Associate Professor of Anthropology Leighton C. Peterson further defines visual sovereignty as "acts of self-representation by [I]ndigenous media producers ... where contemporary media practices are in dialogue with the past, leading to cultural healing." Peterson connects the concept to public broadcasting programs, stating, "Native-produced documentaries broadcast on public television are most certainly acts of visual sovereignty." 66 This section explores the history of Native-created public broadcasting and highlights programs that exemplify the visual sovereignty of Native American producers.

AIM activism spurred the creation of Native-created media beginning with content distributed over public radio stations. The Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 combined with the 1978 Minority Station Startup process sponsored by the National Telecommunications Information Agency and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting provided support for Native public broadcasting in both Native and non-Native stations. 67 As a result, Native-created radio content is mostly broadcast through public radio stations. Pacifica Radio in the 1960s and 1970s was among the first non-Native stations to provide Native producers, such as Frank Ray Harjo (Wotko Muscogee; 1947-1982), Suzan Shown Harjo (Cheyenne and Hodulgee Muscogee), and Peggy Berryhill (Muscogee), the opportunity to create their own content that aired on Pacifica stations across the country. Berryhill later became program director at KALW in San Francisco and KUNM in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and full-time producer at NPR. In 1996, she founded the Native Media Resource Center. 68

The number of Native owned and operated radio stations increased in the 1970s. 69 KYUK-AM , one of the first Native stations, began airing programs in 1971 for the Yup'ik community of Bethel, Alaska. The station later introduced its own television station in 1973. Both stations primarily serve the surrounding Yup’ik community with the goal of providing programming for a mixed audience in both the Yup’ik and English languages. 70 (Television programs offered by KYUK are discussed below.)

The public radio news series National Native News represents an important milestone in the development of Native public broadcasting. First broadcast in the 1980s, the program reaches a wide audience of both Native and non-Native listeners, providing, in the words of the program’s host Gary Fife (Muscogee and Cherokee), "real stories of Native America." 71 For the first time, Native Americans across the country could hear programming that reflected important issues and events within their communities. Notable episodes include a 1991 interview with Makah filmmaker Sandra Osawa on her film Lighting the Seventh Fire and an in-depth look at the American Indian Dance Theater from 1985. Today, National Native News is distributed by Koahnic Broadcast Corporation (KBC), an organization created in 1992 by Alaska Native leaders as a way to combat misconceptions and prejudices. The organization also operates KNBA, a radio station in Anchorage, Alaska, and Native Voice One (NV1), a national Native radio program distribution service. NV1 is distributed to more than 180 affiliates, including 50 Native stations in rural communities. 72

The AAPB collection includes programs from KWSO-FM , a radio station operated by the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs (CTWS) and an affiliate of Native Voice One. AAPB holdings of KWSO-FM feature coverage of Warm Springs Tribal Council elections , instructional Kiksht-language programs , and interviews with tribal leaders including Chief Delvis Heath and religious leader Pierson Mitchell. 73 Mary Sando-Emhoolah (Warm Springs/Wasco/Aleut), honored by the National Federation of Community Broadcasters and the Native American Journalists Association, produced a number of the KWSO-FM programs archived in the AAPB’s collection, including the series Warm Springs , "a program that shares information about the culture, history, current events, and people of Warm Springs." 74 "In essence, the radio station has become the town crier," Sando-Emhoolah, at the time the station manager, remarked in a 2003 Willamette Week (Portland, Oregon) profile of the station. "Our information is tailored to our community because there isn't anybody else out there meeting our needs." 75

The public radio series Neighbors aired in the 1980s and 1990s over non-Native owned station KDLG-FM (Dillingham, Alaska) and featured "conversations and reports on local public affairs issues, especially those affecting the American Indian community." 76

In 1991, the documentarian George Burdeau (Blackfeet) recalled that twenty years earlier, affirmative action policies had been responsible for giving Native Americans "the opportunity to make some films from our point of view." 77 A first wave of Native American filmmakers, including Burdeau, Sandra Osawa (Makah), Victor Masayesva Jr. (Hopi), Larry Cesspooch (Northern Ute), Harriet Skye (Standing Rock Sioux), and Richard Whitman (Yuchi/Creek), began in the late 1960s and 1970s to produce films and videos that documented contemporary Native cultures and demonstrated the deeply grounded nature of those ways of life. 78 Many of these filmmakers were affiliated with the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico; Burdeau later headed the IAIA’s Communications Arts Program, which provided training for emerging Native American producers and filmmakers. 79

Sandra Osawa, who taught at the IAIA, was one of the first sixteen minority students accepted in the 1970s into UCLA’s graduate film program. Her career with her husband Yasu has lasted longer than that of any other Native American filmmaker. She was the first Native American to produce a series for television ( The Native American , KNBC, 1974), and six of her documentaries have aired on PBS. 80 In an interview, Osawa expressed a prime concern that has motivated her and other Native American filmmakers:

[Hollywood] movies have been quite effective in freezing us in time, perpetuating the idea that for us to be authentic we must look and act and dress and speak exactly the way we were . . . when the Pilgrims met us. If we deviate from that then we are not authentic. We seem to be the only people stuck in this time warp where to be Indian we have to look a certain way and play a certain role that America wants us to play. . . . America has got quite a hold and quite a grip on our identity. It’s a stranglehold at times and very destructive. There are Native filmmakers out there, and I am not the only one, who are trying to pursue other visions. With a little help we’ll be able to go a long way in correcting some images of the past. 81

A number of the earliest documentaries made with Native American creative involvement focused on Native life and culture in distinct regions. Produced with national and state funding, these series include Forest Spirits , of which the film Living with Tradition was directed by George Burdeau (Blackfeet) (Northeast Wisconsin In-School Telecommunications, University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, 1975), on the Oneida and Menominee tribes of Wisconsin; The Real People (directed by Larry Littlebird (Laguna/Santo Domingo Pueblo), George Burdeau (Blackfeet), Maria Median, KSPS-TV Spokane, 1976), on seven tribes (Spokane, Colville, Kalispel, Kootenai, Nez Perce, Coeur d’Alene, and Flathead) of the northwest Plateau; and People of the First Light (WGBY-TV, Springfield, MA, 1979) on Native Americans in southern New England. 82 " The Mashpee Wampanoags ," an episode of People of the First Light that was co-produced and written by Russell Peters (Mashpee/Wampanoag, 1928 or 1929-2002), follows Mashpee Wampanoag tribal members "living, working the land, fishing the bays, and maintaining the longstanding culture of their ancestors." 83 Pueblo filmmaker Beverly R. Singer states that the program represents the "first public television series to call attention to Indians in the Northeast." 84 The AAPB collection includes additional programs in the series .

In 1976, after the success of The Real People , six Native producers including George Burdeau (Blackfeet) and Frank Blythe (Eastern Band of Cherokee/Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota), chartered The Native American Public Broadcasting Consortium (NAPBC) to support the "creation, promotion and distribution of native media." 85 Blythe became the executive director of the consortium, which originally functioned as a library to circulate among member stations videotapes and films that they could broadcast locally. 86 In 1977, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting awarded the consortium a grant of $103,113 to establish a central location for Native American productions made by local stations, training opportunities, and a resource center for state and local authorities. 87 At the time of the grant, 72 public television stations had joined as members in order to use the library. 88 NAPBC, renamed Native American Public Telecommunications (NAPT) in 1995, later became Vision Maker Media. 89 The organization was the first in public television’s National Minority Consortium, now the National Multicultural Alliance and composed of Latino Public Broadcasting, Black Public Media, Pacific Islanders in Communications, and the Center for Asian American Media, in addition to Vision Maker Media ( https://nmcalliance.org/ ).

Vision Maker Media has supported the creation of more than 500 films since its inception in 1976. The organization "empowers and engages Native People to share stories" and to increase awareness of the diversity of Native peoples in the American public. 90 The AAPB Vision Maker Media Documentaries Collection consists of 40 documentary films created between 1982 and 2012. In the 1970s, NAPBC distributed a series of 30-minute profiles of American Indian Artists produced by KAET-TV in Phoenix for distribution by PBS. 91 In the 1980s, NAPBC produced a second American Indian Artists series, including a program on the artist Jaune Quick-To-See Smith (Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes) (Tony Schmitz, NAPBC, 1982), which includes narrative poetry by Joy Harjo (Muscogee Nation) and narration by Pulitzer Prize winning author N. Scott Momaday (Kiowa). Other notable programs include The Thick Dark Fog , which explores the experiences of Walter Littlemoon (Lakota) while attending a Native American boarding school in South Dakota, and Apache 8 , a program that follows an all-women firefighter crew from the White Mountain Apache Tribe. Harold of Orange (dir. Richard Weise, Film in the Cities, Minneapolis, 1984), boasts an original screenplay by novelist, poet, playwright, historian, and critic Gerald Vizenor (Anishinaabe). Known for creating trickster characters in his fiction, Vizenor centers the 30-minute comedy on a group of reservation men as they attempt to trick a philanthropic foundation into funding a chain of coffeehouses on reservations. The film stars Charlie Hill (Oneida, 1951-2013), the first Native American comedian to appear on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson . 92 In 2000, Sandra Osawa (Makah) profiled Hill in On & Off the Res’ w/ Charlie Hill (Upstream Productions, 2000), which was broadcast on public television. 93

Surviving Columbus , a Peabody Award-winning documentary produced by KNME-TV (Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1992) with a largely Native cast and production crew and supported by NAPBC, exemplifies the organization’s mission and the importance of showcasing a Native American perspective of U.S. history. Hosted by Conroy Chino (Acoma Pueblo) and directed by Diane Reyna (Taos/San Pueblo), the documentary features interviews with Pueblo tribal members about their perspectives of colonial history, the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, and the quincentenary of Columbus’s arrival to the Americas. 94 In press materials, Reyna stated that the film represents an important contribution to Native media because it refuses to accept that the Pueblo are "a vanishing race; it’s important to show that we have a real significant life going on." 95 The Peabody Awards committee further echoed the program’s significant addition to our understanding of American history in their award citation:

Throughout the world, but especially in America, [N]ative peoples and immigrants grappled with the long-term consequences of the Native American encounter with Europeans. In the view of the Peabody Board, this local documentary captured the true legacy of this event. History texts have traditionally presented the European version of the voyage and its aftermath, often ignoring Indian accounts. With this innovative and instructive program, KNME provided a corrective effort. The station, in association with The Institute of American Indian Arts, helped achieve long-overdue recognition for the valor, determination, and achievements of the Pueblo culture before and after the arrival of Columbus. 96

Co-Executive Producer George Burdeau (Blackfeet) points to the crew’s diversity as evidence of the program’s strength: "One of the things that is so exciting about this project for me is the fact that so many Pueblo people were involved from the top down." 97 Acoma Pueblo writer Simon Ortiz wrote the narrative on which the film was based. Narrator and producer Conroy Chino (Acoma Pueblo) began his career as an announcer for public radio station KUNM-FM and later became a reporter for ABC affiliate KOAT-TV, both in Albuquerque. 98 He also has produced other documentaries with support from Vision Maker Media, including Looking Toward Home (Chino & Krusic, 2003) . Reyna, who began her career working as a camera operator for KOAT-TV, later taught at the Institute of American Indian Arts. 99 Surviving Columbus was co-produced by Nedra Darling (Potawatomi). The documentary includes poetry by Ortiz and Rina Swentzell (Santa Clara Pueblo), who served as script consultant with Chino, and art by Felix Vigil (Jemez Pueblo/Jicarilla Apache).

Shirley Sneve, former Vision Maker Media executive director, has stated, "We try to show that Native Americans are hopeful and still very proud of their cultures and languages…. Anytime that we can do the Native language with English subtitles we try to encourage that to show that people still speak these languages and that they’re important to our connection to the world." 100 To that effect, the acclaimed documentary The Return of Navajo Boy (Jeff Spitz Productions, 2000), broadcast in the PBS Independent Lens series, benefited from a commitment of co-producer and translator Bennie Klain (Navajo) to include conversations in the Navajo language throughout much of the film. 101 The screening before congressional staff and EPA officials of the compelling film, which intertwines a family reunion story with efforts to seek environmental justice for uranium mining contamination, provoked government and industry cleanup efforts. 102 Weaving Worlds (Trickster Films, LLC and ITVS, in association with NAPT, 2008), written and directed by Klain, presents a portrait of Navajo weavers and their complicated relationships with traders and buyers. A Navajo speaker himself, Klain "learned from Navajo Boy … that using the language gives off a certain intimacy, a kind of kinship," and he tried "to forge that kinship bond so [the participants] would be more open with me." Reviewing the film, Professor of Native Studies Gary Witherspoon has written that it "explores how Navajo people are fighting to protect and preserve their land, water, and air from powerful companies and government entities that want to exploit it for their own purposes, with limited benefits to the Navajo people who are trying to live well in the modern world in their own communities on their own land following many of their own traditions and beliefs. This film does an excellent job of presenting the realities of this effort." 102 Beverly R. Singer praised Klain for asking "the right questions in looking at issues facing his own Navajo communities in the wake of depleting resources and cultural disintegration." 104 In Waterbuster (Brave Boat Productions and NAPT, 2006), director J. Carlos Peinado (Mandan/Hidatsa/Arikara Nation), returns to the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota of his ancestors and discovers the story of their forced displacement and loss of land due to the erection by the Army Corps of Engineers of a dam project in the 1950s. 105 The two-part series Indian Country Diaries (NAPT, in association with ITVS, 2006) explores in 90-minute documentaries "modern Native American communities in both urban and reservation settings, revealing a diverse people working to revitalize their culture while improving the social, physical, and spiritual health of their people." In the episode " A Seat at the Drum ," produced by Lena Carr (Navajo), Carol Cornsilk (Cherokee), and Frank Blythe (Eastern Band of Cherokee/Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota), journalist Mark Anthony Rolo (Bad River Ojibwe) looks at Native Americans who were relocated to cities, in this case, Los Angeles. In Spiral of Fire , producer/director/editor Carol Cornsilk (Cherokee) follows writer and narrator LeAnne Howe (Choctaw) to the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina, where Cherokee youth are empowered through learning about their culture, while interacting with others. 106

Other Native American production companies and stations also have provided training for emerging television producers and filmmakers seeking to create programming for broadcast over public television. Some of the programs offered by KYUK-TV include the series Frost Bits , which airs the same program in both English and Yup’ik. The AAPB collection also includes Waves of Wisdom , a series of 80 interviews with Yup’ik tribal members, and Yup'ik Dance and Culture , footage that showcases traditional Yup'ik practices.

We of the River , broadcast in 1986, is further emblematic of the programming produced by KYUK-TV. The television program details the history of the Yup’ik people beginning with their creation story and the arrival of Moravian missionaries to the area. We of the River includes clips from early films taken by white settlers, and narration written and performed by John Active (Yup’ik, 1948-2018). The program was the product of an effort between producers and Yup'ik community leaders working together to provide a comprehensive tribal history. Nominating the program for a 1986 Peabody Award, We of the River producers argued that the "direct link between the footage and the people who helped to fashion" the program illustrates the uniqueness of Native media. 107 Make Prayers to the Raven (KUAC, Fairbanks, Alaska, 1987) , a series exploring the cultures of Alaska’s Koyukon communities, was produced with a council of tribal representatives from four of the eleven Koyukon villages. The AAPB holds two episodes from the series, "The Bible and the Distant Time" and "Grandpa Joe’s Country." 108

The Great Spirit within the Hole (Twin Cities Public Television, Saint Paul, Minnesota, 1983) , produced and directed by Chris Spotted Eagle (Houma?), narrated by Will Sampson (Muscogee Creek, 1933-1987) and featuring music by Buffy Sainte-Marie (Cree), details how incarcerated Native Americans may reconnect to their ancestral culture by practicing their traditional religion. Produced a few years after the 1978 passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, the documentary also highlights the "terrible human cost for Native Americans living in a society which does not comprehend their cultures, values, or histories." 109 Spotted Eagle formed his own production company in Minneapolis and hosted Indian Calling , a radio talk show for community radio station KFAI. 110

Both Native and non-Native viewers responded positively to The Great Spirit within the Hole , which was broadcast nationally over PBS stations. Letters from around the country, including Hawaii, Minnesota, the Tule River Tribal Council, and the Navajo Reservation, praised the program’s poignant portrayal of "the lives, the culture, the beauty and strengths of the Indian people." Additionally, the Navajo Corrections Program used the show in a workshop for the 1983 Correctional Institutions Symposium. Millie Seubert, the co-director of the Native American Film + Video Festival, praised Spotted Eagle for "[communicating] very beautifully the important message that spirituality is a primary reality in the lives of Indian people today." 111

Low-power public television represents an opportunity for Native communities to create their own programming. Frank H. Tyro, director of the Salish Kootenai College Media Center, has written extensively about the low-powered television station that serves the Salish reservation and students at the college. The station provides programs like local sports coverage, language classes, and a cooking show entitled Cookin’ with the Colonel . 112

FNX | First Nations Experience, a shared vision of Founding Partners, the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians, and the San Bernardino Community College District devoted to Native American and World Indigenous content, and owned by KVCR-PBS San Bernardino, began broadcasting locally in the Los Angeles area on September 25, 2011, before going national on November 1, 2014. The network offers "Native-produced and themed documentaries, dramatic series, nature, cooking, gardening, children's and arts programming … to accurately illustrate the lives and cultures of Native people around the world." 113

Sandra Osawa’s tribute to the late Native American jazz musician Jim Pepper (Kaw/Muscogee Creek,1941-1992), Pepper’s Pow Wow (Upstream Productions, 1997), included in AAPB as a 1998 episode of the WNET series MetroArts/Thirteen , is available for viewing at the Library of Congress and GBH. In speaking about that film, Osawa elucidated a prime intention that has animated her filmmaking career:

The motivation was to look at contemporary images and contemporary people and discover positive, possibly unrecognized, stories. . . . To me, [Jim Pepper’s] music was a metaphor of how to survive in two worlds. When I taught at the Institute for American Indian Studies we often talked about that third alternative. . . . We talked about cultural survival issues, identity issues, and the fact that our choices seemed narrow. I mean, we could sell out and become successful like everyone else with this so-called education that we all had, or we could become very traditional and withdraw from much of society. We also talked about the third alternative, a way to take aspects of both parts of life. I’ve appreciated Indian people who are able to take the best of both worlds and to survive with their integrity intact. . . . I see people who actively use elements of both their Native American culture and the outside world to survive as a possible solution for us. With his music, Jim is saying no, I don’t have to give up my own music, my own cultural background. I can keep it. I can, in fact, make it stronger. I can combine it, I can fuse it with jazz, and I can tell a story that way. To me that’s really exciting because it frees us up and allows us to have another choice about how to survive in the complicated and messed up world that we live in. 114

Next: Notes

Exhibit sections.

Sally Smith

Alan Gevinson

Additional Resources

Sign up for the AAPB newsletter! X

Stay up to date on new exhibits, special collections, projects, and more.

Click here to subscribe.

Popular Sovereignty

Tetra Images / Henryk Sadura / Brand X Pictures / Getty Images

- U.S. Constitution & Bill of Rights

- History & Major Milestones

- U.S. Legal System

- U.S. Political System

- Defense & Security

- Campaigns & Elections

- Business & Finance

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

- M.A., History, University of Florida

- B.A., History, University of Florida

The popular sovereignty principle is one of the underlying ideas of the United States Constitution, and it argues that the source of governmental power (sovereignty) lies with the people (popular). This tenet is based on the concept of the social contract , the idea that government should be for the benefit of its citizens. If the government is not protecting the people, says the Declaration of Independence, it should be dissolved. That idea evolved through the writings of Enlightenment philosophers from England—Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) and John Locke (1632–1704)—and from Switzerland—Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778).

Hobbes: Human Life in a State of Nature

Thomas Hobbes wrote The L e viathan in 1651, during the English Civil War , and in it, he laid out the first basis of popular sovereignty. According to his theory, human beings were selfish and if left alone, in what he called a "state of nature," human life would be "nasty, brutish, and short." Therefore, to survive people give over their rights to a ruler who provides them with protection. In Hobbes' opinion, an absolute monarchy provided the best form of security.

Locke: The Social Contract Limiting Ruler's Powers

John Locke wrote Two Treatises on Government in 1689, in response to another paper (Robert Filmer's Patriarcha ) which argued that kings have a "divine right" to rule. Locke said that the power of a king or government doesn't come from God, but comes from the people. People make a "social contract" with their government, trading away some of their rights to the ruler in exchange for security and laws.

In addition, Locke said, individuals have natural rights including the right to hold property. The government does not have the right to take this away without their consent. Significantly, if a king or ruler breaks the terms of the "contract"—by taking away rights or taking away property without an individual's consent—it is the right of the people to offer resistance and, if necessary, depose him.

Rousseau: Who Makes the Laws?

Jean Jacques Rousseau wrote The Social Contract in 1762. In this, he proposes that "Man is born free, but everywhere he is in chains." These chains are not natural, says Rousseau, but they come about through the "right of the strongest," the unequal nature of power and control.

According to Rousseau, people must willingly give legitimate authority to the government through a "social contract" for mutual preservation. The collective group of citizens who have come together must make the laws, while their chosen government ensures their daily implementation. In this way, the people as a sovereign group look out for the common welfare as opposed to the selfish needs of each individual.

Popular Sovereignty and the US Government

The idea of popular sovereignty was still evolving when the founding fathers were writing the US Constitution during the Constitutional Convention of 1787. In fact, popular sovereignty is one of six foundational principles on which the convention built the US Constitution . The other five principles are a limited government, the separation of powers , a system of checks and balances, the need for judicial review , and federalism , the need for a strong central government. Each tenet gives the Constitution a basis for authority and legitimacy that it uses even today.

Popular sovereignty was often cited before the US Civil War as a reason why individuals in a newly organized territory should have the right to decide whether or not the practice of enslavement should be allowed. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 was based on the idea—that people have a right to "property" in the form of enslaved people. It set the stage for a situation that became known as Bleeding Kansas , and it is a painful irony because certainly Locke and Rousseau would not agree that people are ever considered property.

As Rousseau wrote in "The Social Contract":

"From whatever aspect we regard the question, the right of slavery is null and void, not only as being illegitimate, but also because it is absurd and meaningless. The words slave and right contradict each other, and are mutually exclusive."

Sources and Further Reading

- Deneys-Tunney, Anne. "Rousseau shows us that there is a way to break the chains—from within." The Guardian , July 15, 2012.

- Douglass, Robin. "Fugitive Rousseau: Slavery, Primitivism, and Political Freedom." Contemporary Political Theory 14.2 (2015): e220–e23.

- Habermas, Jurgen. "Popular sovereignty as procedure." Eds., Bohman, James, and William Rehg. Deliberative Democracy: Essays on Reason and Politics . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997. 35–66.

- Hobbes, Thomas. " The Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, & Power of a Common-Wealth Ecclesiasticall and Civill ." London: Andrew Crooke, 1651. McMaster University Archive of the History of Economic Thought. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University.

- Locke, John. " Two Treastises of Government ." London: Thomas Tegg, 1823. McMaster University Archive of the History of Economic Thought. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University.

- Morgan, Edmund S. "Inventing the People: The Rise of Popular Sovereignty in England and America." New York, W.W. Norton, 1988.

- Reisman, W. Michael. "Sovereignty and Human Rights in Contemporary International Law." American Journal of International Law 84.4 (1990): 866–76. Print.

- Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. The Social Contract . Trans. Bennett, Jonathan. Early Modern Texts, 2017.

- The Social Contract in American Politics

- What Is an Absolute Monarchy? Definition and Examples

- Overview of United States Government and Politics

- Thomas Hobbes Quotes

- What Is Democracy? Definition and Examples

- The Root Causes of the American Revolution

- What Is Classical Liberalism? Definition and Examples

- What Is Pluralism? Definition and Examples

- What Is Absolutism?

- Why We Need Laws to Exist in Society

- What Are Individual Rights? Definition and Examples

- Constitutional Law: Definition and Function

- What Is the Common Good in Political Science? Definition and Examples

- What Are Natural Rights?

- Civil Society: Definition and Theory

- Rousseau's Take on Women and Education

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Representations of Native Americans in the Mass Media

The historical construction of Indian in American popular culture poses serious challenges for conducting research about representations of indigenous culture, identity, and politics. Mass-mediated representation deserves specific attention, as popular entertainment has been one of the most significant historic battlegrounds over the status of indigenous identity in American culture. Representations of American Indians have been reworked and negotiated as they have circulated through a variety of mediums, including theatrical performances, silent films, Westerns, prime time television, independent films, advertising, sports culture, and so on. Beginning with Buffalo Bill's Wild West show and Thomas Edison's kinetoscope, introduced the at the 1893 Chicago Columbian World's Exposition, American mass entertainment has been preoccupied with the drama of westward expansion and the noble savage of the American frontier. Later, the films of John Ford developed the Hollywood image of the screen savage. Film continued to address the topic of American Indians through the lens of the 1960's and 1970's counterculture, 1980's imperial nostalgia, 1990s sympathy and revisionism, and, in the 21st century, through native filmmaker's reclamation of indigenous visual sovereignty. Not all media are uniform in their portrayals. The televisual Indian evolved quite differently than her/his counterpart in film. At some points, television has been even more progressive in its portrayals of American Indian characters, more willing to feature native actors and storylines than mainstream Hollywood film. Besides film and television, sports and advertising have had the most influence on popular conceptions of American Indians. While commodified images of American Indians are ubiquitous in popular culture, sport culture (mascots) has become the most popular site where Indian imagery is used to generate a profit. Struggles over everything from the moving image to sports mascots demonstrate the importance of studying the power of the image, particularly in the context of American settler colonialism.

Related Papers

Danielle Endres

In 2005 the National Collegiate Athletic Association banned the use of American Indian symbols such as mascots, nicknames, and imagery in postseason sporting events. However, several universities successfully appealed this decision by demonstrating permission from eponymous American Indian nations. The focus of this essay is on the rhetorical implications of this permission argument within American Indian rhetoric about American Indian mascots, nicknames, and imagery. Drawing from the lens of rhetorical colonialism and an examination of the University of Utah Utes, I reveal how American Indian permission for mascots can be seen as upholding rather than challenging the system of colonialism through a form of self-colonization.

Christina Welch

This interdisciplinary article examines and contextualizes the popular visual representations of Native American peoples and their lifeways at the World’s Fairs and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West from 1851 and 1884, respectively, to 1904. It will argue that these fairs and shows were arenas where colonially constructed identities and Western ideologies were enforced and reinforced to the general public, and where Native Americans were knowingly represented, regardless of reality, as primitive savages in direct opposition to Western civilized Christian norms, or as exemplars of assimilation saved from savagery by the benefits of Western civilized Christian norms. It suggests that the maxim of the World’s Columbian Exposition (1893–4), ‘To see is to know’, should not be underestimated in communicating identities; for during the mid-nineteenth to early twentieth century, colonially constructed visual knowledge was used to blur the boundaries between entertainment and education, allowing the cultural ideologies of the West to pass as reality.

Nolan Kraszkiewicz

An examination of the use of Native American mascot iconography in the context of public education and sports in the state of Oklahoma, the roles they play in institutionalized racism, and the potential paths forward.

International Journal For Multidisciplinary Research

Bayu Baladewa

Basic and Applied Social Psychology

Daphna Oyserman , Hazel Markus

Geraud Blanks

ii DEDICATION iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vi CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER II: MAINSTREAM CULTURE AND NATIVE AMERICANS 4 Mythologizing Indians: white claims of native cultural properties 7 American sports and the disembodied Indian as mascot 9 CHAPTER III: PAST ATTEMPTS TO USE LAW TO MINIMIZE HARM AND APPROPRIATION OF NATIVE AMERICAN NAMES AND SYMBOLS 13 The evolution of name-change activism 14 Arguments That Frame the Debate 17 The Washington Redskins name-change controversy 20 The virtues of Trademark law and the need for a new approach 25 CHAPTER IV: A LEGAL STRATEGY THAT AVOIDS FIRST AMENDMENT PROBLEMS 30 Delineating right of publicity and intellectual properties doctrine 34 Trademark, copyright and the right of publicity 35 CHAPTER V: CHICAGO BLACKHAWKS CASE STUDY 40 Right of publicity and freedom of speech 42 The Illinois Act: Illinois’ right of publicity law 46 American Indian descendancy 46 My proposal: modernizing state right of publicity laws 50 CHAPTER VI: DISCUSSION 52

Chronicle of Higher Education

C. Richard King

Cross-Cultural Challenges in British and American Studies

Sanja Matković

The image that the world has of Native Americans is mostly created by the media, particularly movies. This paper deals with movie representations of Native Americans during the 1950s and the 1990s, focusing on three examples: The Searchers (1956), Dances with Wolves (1990), and Smoke Signals (1998). Each of these movies contributed to shaping society’s perception of indigenous peoples and helped the development of stereotypes or stereotypes deconstruction. On the one hand, The Searchers is a typical representative of the western movies era and the depiction of Indians at that time. On the other hand, in some movies from the 1990s, such as Dances with Wolves, the cinematic portrayal of Native Americans changes, and they are shown in a different light. Furthermore, it is in this period that Native Americans start producing movies about themselves for the first time. Smoke Signals is one of the first successful movies written, directed, and produced by Native Americans, which finally creates a realistic image of indigenous peoples.

American Indian Quarterly

Jason Edward Black

Journal of Communication

Debra Merskin

RELATED PAPERS

Biochemistry

Vivek Chauhan

Andrea Fabbri

Luis Vicente Garcia Merino

LAURA SABATELLI

Robin Seijdel

esp-world.info

Mojibur Rahman

bülent öngören

Acta Agraria Debreceniensis

leopoldo ramirez

Luana Kallas

Mehmet Müftüoğlu

Space Policy

Duncan Lunan

Linear Algebra and its Applications

Slobodan Simic

Crystal Growth & Design

Arijit Halder

IEEE Communications Magazine

Basem ElHalawany

Serious Philosophy

Stuart W Mirsky

2007 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory

Marco Chiani

Journal of orthopaedic case reports

ADITYA PATHAK

HAL (Le Centre pour la Communication Scientifique Directe)

stephane madelrieux

Angela María Menchón

Archives of Asian Aert

Catherine Stuer

Género y trabajo en las maquiladoras de México: Nuevos actores en nuevos contextos

Kenya Herrera Bórquez

快速办理毕业证, 各种各类的毕业证齐全

mark B Luther

Baso Indra Wijaya Aziz

Methods in molecular biology

Emanuela Gussoni

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Encyclopedia of New Populism and Responses in the 21st Century pp 1–4 Cite as

“The People” in Nationalism, Populism, and Popular Culture

- Giorgos Venizelos 4

- Living reference work entry

- Latest version View entry history

- First Online: 24 May 2023

95 Accesses

9 Altmetric

From political modernity to post-pandemic times, notion of “the people” and “sovereignty” have traditionally dominated political discourse. They appear in right-wing and nationalist discourses, leftist and socialist repertories as well as representations of popular culture. As such, their omnipresence has led many experts to claim that either everything is populist or the category of populism is no useful at all, and that we should perhaps use the term popular not populist. This entry objects these claims, arguing that it is a different logic that interpellates “the people” of nationalism, populism, and popular culture.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Aslanidis P (2020) Major directions in populism studies: is there room for culture? Partecipazione e Conflitto 13(1):59–82

Google Scholar

De Cleen B, Stavrakakis Y (2017) Distinctions and articulations: a discourse theoretical framework for the study of populism and nationalism. JAVNOST-Public 24(4):301–319

Article Google Scholar

March L (2017) Left and right populism compared: the British case. Br J Polit Int Rel 19(2):282–303

Ostiguy P (2017) Populism: a socio-cultural approach. In: Kaltwasser Rovira C, Taggart P, Espejo Ochoa P, Ostiguy P (eds) The Oxford handbook of populism. Oxford University Press, pp 73–97

Venizelos G (2020) Populism and the digital media: a necessarily symbiotic relationship? Insights from the case of Syriza. In: Breeze R, Fernandez Vallejo AM (eds) Politics and populism across modes and media. Peter Lang, Bern, pp 47–78

Venizelos G (2021) Populism or nationalism? The paradoxical non-emergence of populism in Cyprus. Polit Studies

Venizelos G (2022) Doald Trump in power: discourse, performativity, identication, critical sociology. https://doi.org/10.1177/089692052211182

Venizelos G (2023) Populism in power: discourse and Performativity in SYRIZA and Donald Trump. London: Routledge

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus

Giorgos Venizelos

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Giorgos Venizelos .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

School of Social Sciences, Christ University, Bengaluru, India

Joseph Chacko Chennattuserry

Madhumati Deshpande

College of Business Innovation, University of Toledo, Toledo, OH, USA

Section Editor information

School of Social Scences, Christ University, Bengaluru, India

CHRIST (Deemed to be University), Bengaluru, India

S. P. Vagishwari

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Venizelos, G. (2023). “The People” in Nationalism, Populism, and Popular Culture. In: Chacko Chennattuserry, J., Deshpande, M., Hong, P. (eds) Encyclopedia of New Populism and Responses in the 21st Century. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-9859-0_279-2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-9859-0_279-2

Received : 31 July 2022

Accepted : 01 November 2022

Published : 24 May 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-16-9859-0

Online ISBN : 978-981-16-9859-0

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Social Sciences Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

Chapter history

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-9859-0_279-2

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-9859-0_279-1

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Representing Popular Sovereignty

The constitution in american political culture, alternative formats available from:.

- Google Play

Read Excerpt View Table of Contents

Request Desk or Examination Copy Request a Media Review Copy

- Share this:

Table of contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Constitutionalism as Culture

Chapter One: The Problem of an Abstract Constitution

Chapter Two: The Conscious Creation of Constitutional Culture

Chapter Three: The Constitution in Public History

Chapter Four: The Constitution as a Written Document

Chapter Five: The Constitution as a Symbol of Democracy

Chapter Six: The Constitution in Educational Policy

Conclusion: Representing Popular Sovereignty

Selected Bibliography

Explores the contradiction between the Constitution's importance as a political document with its weakness as a symbol in American popular culture.

Description

Using the events of the Constitution's Bicentennial from 1987 to 1991 as a case study, Representing Popular Sovereignty explores the contradiction between the Constitution's importance as a political document and its weakness as a symbol in American popular culture.

Daniel Lessard Levin is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Boise State University.

"Many have remarked on the importance or lack of importance of the Constitution in American popular culture, but no one, to my knowledge, has examined that systematically. Levin does so, and in a manner that demonstrates his conversance with a broad range of literature. Levin also makes some sophisticated philosophic points accessible. This book fills a conspicuous gap in the literature on constitutional theory (in part because it speaks so directly to well-known works in that field). " — Anne Norton, University of Pennsylvania "The author directly confronts an awkward fact of life: few Americans possess a substantial knowledge of the Constitution and, in terms of substance, not many citizens seem to mind the relative ignorance. Moreover, he rightly notes that the role of the Constitution in American consciousness will not ascend to a higher place until the constitutional tradition is integrated into the 'serious business of everyday politics. '" — David Gray Adler, Idaho State University

Reservation Reelism

Redfacing, visual sovereignty, and representations of native americans in film.

360 pages 41 illustrations, index

January 2011

978-0-8032-1126-1

978-0-8032-4597-6

978-0-8032-3445-1

978-0-8032-6827-2

About the Book

Table of contents, also of interest.

Celluloid Indians

Alanis Obomsawin

The Fast Runner

Navajo Talking Picture

All That Remains

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Visual sovereignty intervenes in larger discussions of Native American sovereignty by locating and advocating for Indigenous cultural and political power both within and outside of Western legal jurisprudence. In more basic terms, it is a way for indigenous artists to claim visual space to create or develop their own representations, stories ...

In my publicly engaged scholarship, I engage in the practice of Visual Sovereignty, which can be defined as exercising the inherent power to govern oneself and control one's own narrative (and the narrative of one's people) via self-representation in film, media, performance, and photography.

Peterson connects the concept to public broadcasting programs, stating, "Native-produced documentaries broadcast on public television are most certainly acts of visual sovereignty." 66 This section explores the history of Native-created public broadcasting and highlights programs that exemplify the visual sovereignty of Native American producers.

Popular sovereignty and representation in the English Civil War Lorenzo Sabbadini 8. Prerogative, popular sovereignty, and the American founding Eric Nelson 9. Popular sovereignty and political representation: Edmund Burke in the context of eighteenth-century thought Richard Bourke 10.

Popular sovereignty, in U.S. history, a controversial political doctrine that the people of federal territories should decide for themselves whether their territories would enter the Union as free or slave states. Its enemies, especially in New England, called it 'squatter sovereignty.' Learn more about the doctrine.

8 Prerogative, popular sovereignty, and the American founding 187 eric nelson 9 Popular sovereignty and political representation: Edmund Burke in the context of eighteenth-century thought 212 richard bourke 10 From popular sovereignty to civil society in post-revolutionary France 236 bryan garsten 11 Popular sovereignty as state theory in the

Finally, visual representations of populist actors in mainstream media have gained academic interest (Herkman, 2019; ... rejecting 'the essence of democracy, that is, popular sovereignty and majority rule'. This not only becomes obvious when studying the magazine's content (Schilk, ...

and kinetic contemplations of what sovereignty means at differ-ent historical and paradigmatic junctures.5 The visual—particularly film, video, and new media—is a germi-nal and exciting site for exploring how sovereignty can be a creative act of self-representation that has the potential to both undermine

both within and outside of Western legal jurisprudence.5 The visual, particu-larly film, video, and new media is a germinal and exciting site for exploring how sovereignty is a creative act of self-representation that has the potential to both undermine stereotypes of indigenous peoples and to strengthen what

Keywords: sovereignty; democracy; people; masses; revolution; representation; Jacobins; Rousseau There is a tension in the notion of popular sovereignty, and the notion of democracy associated with it, that is both older than our terms for these notions themselves and more fundamental than the apparently consensual way we tend to use them today.

From this vantage point, we see that forces on the left and right contest the normative and policy implications of three key features in populism's normative democratic core: (1) the relationship between popular sovereignty and representation; (2) the nature of equality; and (3) the political economy of the conflict between 'the people' and ...

Popular Sovereignty and Representation When conceived as rule by citizens over as much of their collective public life as possible, popular sovereignty's desirability is seldom openly questioned.

6 Parliamentary sovereignty, popular sovereignty, and Henry Parker's adjudicative standpoint; 7 Popular sovereignty and representation in the English Civil War; 8 Prerogative, popular sovereignty, and the American founding; 9 Popular sovereignty and political representation; 10 From popular sovereignty to civil society in post-revolutionary France

21. For this. Chicasaw scholar, indigenism is the a priori to national myths on origin, history, freedom, constraint, difference and, as such, it is "vital to. understanding how power and ...

The popular sovereignty principle is one of the underlying ideas of the United States Constitution, and it argues that the source of governmental power (sovereignty) lies with the people (popular). This tenet is based on the concept of the social contract, the idea that government should be for the benefit of its citizens.If the government is not protecting the people, says the Declaration of ...

This interdisciplinary article examines and contextualizes the popular visual representations of Native American peoples and their lifeways at the World's Fairs and Buffalo Bill's Wild West from 1851 and 1884, respectively, to 1904. ... M. H. (2013). Reservation realism: Redfacing, visual sovereignty, and representations of Native Americans ...

Traditionally, many of these signs were linked to the Chinese revolution, especially during the Mao era, when visual politics were grounded exclusively in socialist realist understandings of art, for instance in propaganda posters. 30 Some of these propaganda campaigns also addressed issues of health and disease, often presenting model workers ...

Thus, by appropriating popular trends and actively engaging with mainstream culture, these Native subjects are expressing their visual sovereignty. Film and visual studies scholar Michelle Raheja (Seneca) finds "visual sovereignty as a way of reimagining Native-centered articulations of self-representation and autonomy that engage the ...

From a discursive point of view, "the people" of populism is defined as "the underdog," as demos that seek to restore popular sovereignty. It functions as the nodal point that organizes populist discourse. "The people" of nationalism, on the other hand, is a metaphor for ethnos - it is framed as pure and homogenous and aims to ...

The answer to that question depends on what we think the purpose of representative government is. Most research in political science presumes that the purpose of representative government is to represent the will of the people by translating popular sentiment or public interest into governmental policy. It therefore presumes that a good measure ...

A people's egalitarian capacity to concentrate both its collective intelligence and force, from this perspective, takes priority over concerns about how best to represent the full variety of positions and interests that differentiate and divide a community. Keywords: sovereignty. democracy. people. masses.

Description. Using the events of the Constitution's Bicentennial from 1987 to 1991 as a case study, Representing Popular Sovereignty explores the contradiction between the Constitution's importance as a political document and its weakness as a symbol in American popular culture. Daniel Lessard Levin is Assistant Professor of Political Science ...

Native actors, directors, and spectators have had a part in creating these cinematic representations and have thus complicated the dominant, and usually negative, messages about Native peoples that films portray. In Reservation Reelism Raheja examines the history of these Native actors, directors, and spectators, reveals their contributions ...