Types Of Qualitative Research Designs And Methods

Qualitative research design comes in many forms. Understanding what qualitative research is and the various methods that fall under its…

Qualitative research design comes in many forms. Understanding what qualitative research is and the various methods that fall under its umbrella can help determine which method or design to use. Various techniques can achieve results, depending on the subject of study.

Types of qualitative research to explore social behavior or understand interactions within specific contexts include interviews, focus groups, observations and surveys. These identify concepts and relationships that aren’t easily observed through quantitative methods. Figuring out what to explore through qualitative research is the first step in picking the right study design.

Let’s look at the most common types of qualitative methods.

What Is Qualitative Research Design?

Types of qualitative research designs, how are qualitative answers analyzed, qualitative research design in business.

There are several types of qualitative research. The term refers to in-depth, exploratory studies that discover what people think, how they behave and the reasons behind their behavior. The qualitative researcher believes that to best understand human behavior, they need to know the context in which people are acting and making decisions.

Let’s define some basic terms.

Qualitative Method

A group of techniques that allow the researcher to gather information from participants to learn about their experiences, behaviors or beliefs. The types of qualitative research methods used in a specific study should be chosen as dictated by the data being gathered. For instance, to study how employers rate the skills of the engineering students they hired, qualitative research would be appropriate.

Quantitative Method

A group of techniques that allows the researcher to gather information from participants to measure variables. The data is numerical in nature. For instance, quantitative research can be used to study how many engineering students enroll in an MBA program.

Research Design

A plan or outline of how the researcher will proceed with the proposed research project. This defines the sample, the scope of work, the goals and objectives. It may also lay out a hypothesis to be tested. Research design could also combine qualitative and quantitative techniques.

Both qualitative and quantitative research are significant. Depending on the subject and the goals of the study, researchers choose one or the other or a combination of the two. This is all part of the qualitative research design process.

Before we look at some different types of qualitative research, it’s important to note that there’s no one correct approach to qualitative research design. No matter what the type of study, it’s important to carefully consider the design to ensure the method is suitable to the research question. Here are the types of qualitative research methods to choose from:

Cluster Sampling

This technique involves selecting participants from specific locations or teams (clusters). A researcher may set out to observe, interview, or create a focus group with participants linked by location, organization or some other commonality. For example, the researcher might select the top five teams that produce an organization’s finest work. The same can be done by looking at locations (stores in a geographic region). The benefit of this design is that it’s efficient in collecting opinions from specific working groups or areas. However, this limits the sample size to only those people who work within the cluster.

Random Sampling

This design involves randomly assigning participants into groups based on a set of variables (location, gender, race, occupation). In this design, each participant is assigned an equal chance of being selected into a particular group. For example, if the researcher wants to study how students from different colleges differ from one another in terms of workplace habits and friendships, a random sample could be chosen from the student population at these colleges. The purpose of this design is to create a more even distribution of participants across all groups. The researcher will need to choose which groups to include in the study.

Focus Groups

A focus group is a small group that meets to discuss specific issues. Participants are usually recruited randomly, although sometimes they might be recruited because of personal relationships with each other or because they represent part of a certain demographic (age, location). Focus groups are one of the most popular styles of qualitative research because they allow for individual views and opinions to be shared without introducing bias. Researchers gather data through face-to-face conversation or recorded observation.

Observation

This technique involves observing the interaction patterns in a particular situation. Researchers collect data by closely watching the behaviors of others. This method can only be used in certain settings, such as in the workplace or homes.

An interview is an open-ended conversation between a researcher and a participant in which the researcher asks predetermined questions. Successful interviews require careful preparation to ensure that participants are able to give accurate answers. This method allows researchers to collect specific information about their research topic, and participants are more likely to be honest when telling their stories. However, there’s no way to control the number of unique answers, and certain participants may feel uncomfortable sharing their personal details with a stranger.

A survey is a questionnaire used to gather information from a pool of people to get a large sample of responses. This study design allows researchers to collect more data than they would with individual interviews and observations. Depending on the nature of the survey, it may also not require participants to disclose sensitive information or details. On the flip side, it’s time-consuming and may not yield the answers researchers were looking for. It’s also difficult to collect and analyze answers from larger groups.

A large study can combine several of these methods. For instance, it can involve a survey to better understand which kind of organic produce consumers are looking for. It may also include questions on the frequency of such purchases—a numerical data point—alongside their views on the legitimacy of the organic tag, which is an open-ended qualitative question.

Knowledge of the types of qualitative research designs will help you achieve the results you desire.

With quantitative research, analysis of results is fairly straightforward. But, the nature of qualitative research design is such that turning the information collected into usable data can be a challenge. To do this, researchers have to code the non-numerical data for comparison and analysis.

The researcher goes through all their notes and recordings and codes them using a predetermined scheme. Codes are created by ‘stripping out’ words or phrases that seem to answer the questions posed. The researcher will need to decide which categories to code for. Sometimes this process can be time-consuming and difficult to do during the first few passes through the data. So, it’s a good idea to start off by coding a small amount of the data and conducting a thematic analysis to get a better understanding of how to proceed.

The data collected must be organized and analyzed to answer the research questions. There are three approaches to analyzing the data: exploratory, confirmatory and descriptive.

Explanatory Data Analysis

This approach involves looking for relationships within the data to make sense of it. This design can be useful if the research question is ambiguous or open-ended. Exploratory analysis is very flexible and can be used in a number of settings. But, it generally looks at the relationship between variables while the researcher is working with the data.

Confirmatory Data Analysis

This design is used when there’s a hypothesis or theory to be tested. Confirmatory research seeks to test how well past findings apply to new observations by comparing them to statistical tests that quantify relationships between variables. It can also use prior research findings to predict new results.

Descriptive Data Analysis

In this design, the researcher will describe patterns that can be observed from the data. The researcher will take raw data and interpret it with an eye for patterns to formulate a theory that can eventually be tested with quantitative data. The qualitative design is ideal for exploring events that can’t be observed (such as people’s thoughts) or when a process is being evaluated.

With careful planning and insightful analysis, qualitative research is a versatile and useful tool in business, public policy and social studies. In the workplace, managers can use it to understand markets and consumers better or to study the health of an organization.

Businesses conduct qualitative research for many reasons. Harappa’s Thinking Critically course prepares professionals to use such data to understand their work better. Driven by experienced faculty with real-world experience, the course equips employees on a growth trajectory with frameworks and skills to use their reasoning abilities to build better arguments. It’s possible to build more effective teams. Find out how with Harappa.

Explore Harappa Diaries to learn more about topics such as What is Qualitative Research , Quantitative Vs Qualitative Research , Examples of Phenomenological Research and Tips For Studying Online to upgrade your knowledge and skills.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

Published on June 7, 2021 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023 by Pritha Bhandari.

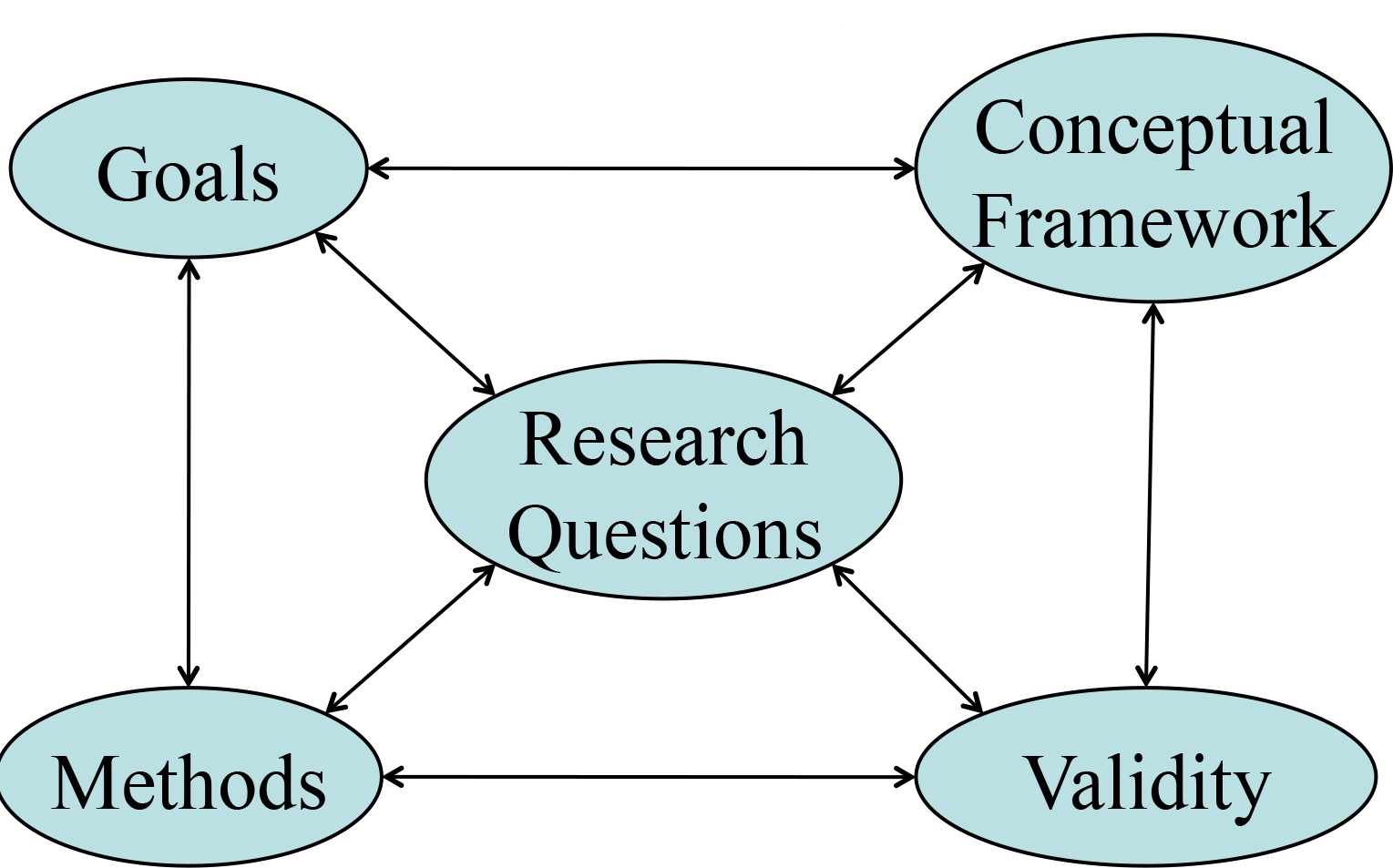

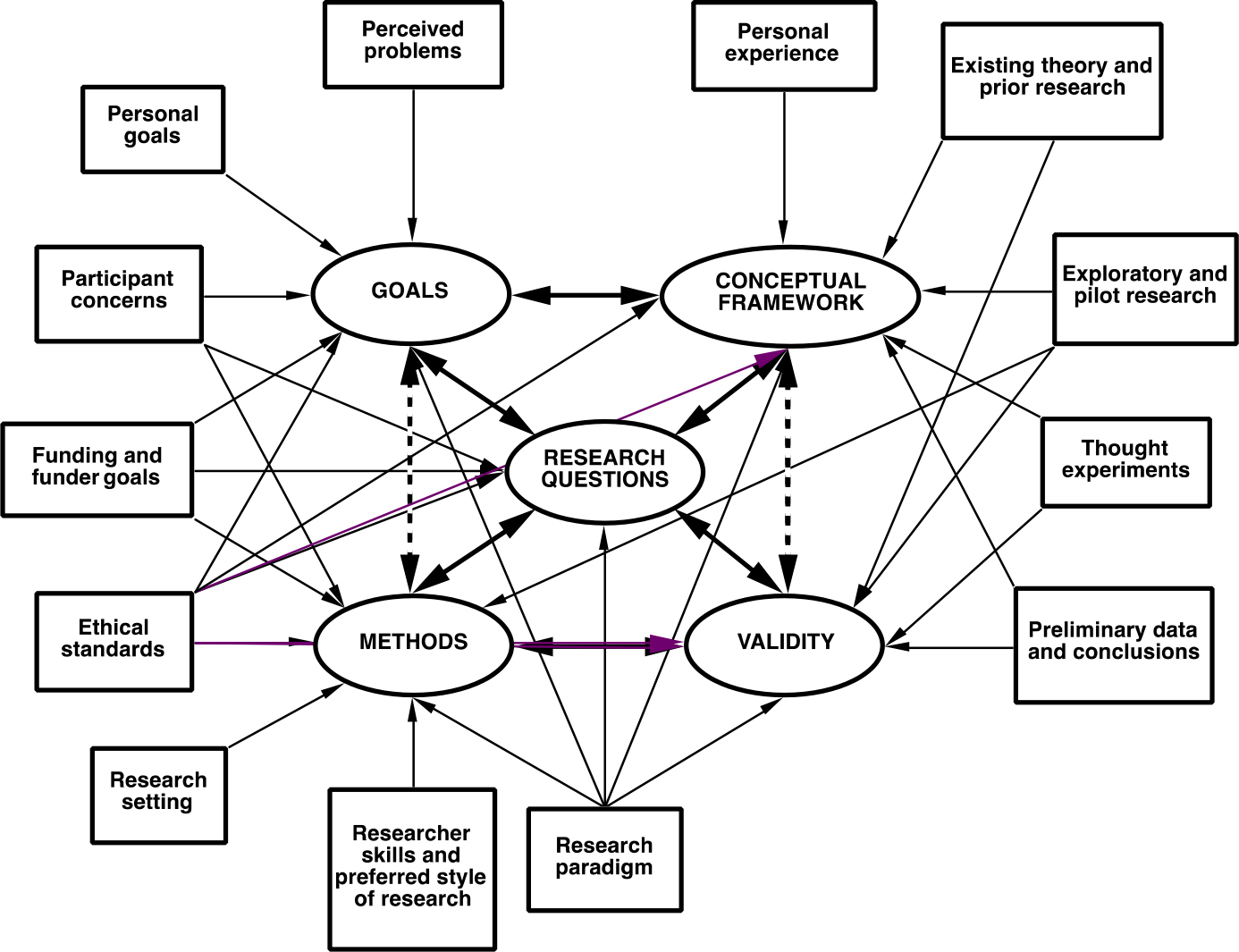

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall research objectives and approach

- Whether you’ll rely on primary research or secondary research

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research objectives and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research design.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities—start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed-methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types.

- Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships

- Descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analyzing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study—plants, animals, organizations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

- Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalize your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study , your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalize to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question .

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviors, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews .

Observation methods

Observational studies allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviors or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what kinds of data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected—for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are high in reliability and validity.

Operationalization

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalization means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in—for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced, while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method , you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample—by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method , it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method , how will you avoid research bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organizing and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymize and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well-organized will save time when it comes to analyzing it. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings (high replicability ).

On its own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyze the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarize your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarize your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analyzing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question . It defines your overall approach and determines how you will collect and analyze data.

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims, that you collect high-quality data, and that you use the right kind of analysis to answer your questions, utilizing credible sources . This allows you to draw valid , trustworthy conclusions.

Quantitative research designs can be divided into two main categories:

- Correlational and descriptive designs are used to investigate characteristics, averages, trends, and associations between variables.

- Experimental and quasi-experimental designs are used to test causal relationships .

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible. Common types of qualitative design include case study , ethnography , and grounded theory designs.

The priorities of a research design can vary depending on the field, but you usually have to specify:

- Your research questions and/or hypotheses

- Your overall approach (e.g., qualitative or quantitative )

- The type of design you’re using (e.g., a survey , experiment , or case study )

- Your data collection methods (e.g., questionnaires , observations)

- Your data collection procedures (e.g., operationalization , timing and data management)

- Your data analysis methods (e.g., statistical tests or thematic analysis )

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population . Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research. For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

In statistics, sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population.

Operationalization means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioral avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalize the variables that you want to measure.

A research project is an academic, scientific, or professional undertaking to answer a research question . Research projects can take many forms, such as qualitative or quantitative , descriptive , longitudinal , experimental , or correlational . What kind of research approach you choose will depend on your topic.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 28, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, guide to experimental design | overview, steps, & examples, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Qualitative Research: Characteristics, Design, Methods & Examples

Lauren McCall

MSc Health Psychology Graduate

MSc, Health Psychology, University of Nottingham

Lauren obtained an MSc in Health Psychology from The University of Nottingham with a distinction classification.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

“Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted“ (Albert Einstein)

Qualitative research is a process used for the systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of non-numerical data (Punch, 2013).

Qualitative research can be used to: (i) gain deep contextual understandings of the subjective social reality of individuals and (ii) to answer questions about experience and meaning from the participant’s perspective (Hammarberg et al., 2016).

Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on gathering and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis, qualitative research focuses on thematic and contextual information.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Reality is socially constructed.

Qualitative research aims to understand how participants make meaning of their experiences – individually or in social contexts. It assumes there is no objective reality and that the social world is interpreted (Yilmaz, 2013).

The primacy of subject matter

The primary aim of qualitative research is to understand the perspectives, experiences, and beliefs of individuals who have experienced the phenomenon selected for research rather than the average experiences of groups of people (Minichiello, 1990).

Variables are complex, interwoven, and difficult to measure

Factors such as experiences, behaviors, and attitudes are complex and interwoven, so they cannot be reduced to isolated variables , making them difficult to measure quantitatively.

However, a qualitative approach enables participants to describe what, why, or how they were thinking/ feeling during a phenomenon being studied (Yilmaz, 2013).

Emic (insider’s point of view)

The phenomenon being studied is centered on the participants’ point of view (Minichiello, 1990).

Emic is used to describe how participants interact, communicate, and behave in the context of the research setting (Scarduzio, 2017).

Why Conduct Qualitative Research?

In order to gain a deeper understanding of how people experience the world, individuals are studied in their natural setting. This enables the researcher to understand a phenomenon close to how participants experience it.

Qualitative research allows researchers to gain an in-depth understanding, which is difficult to attain using quantitative methods.

An in-depth understanding is attained since qualitative techniques allow participants to freely disclose their experiences, thoughts, and feelings without constraint (Tenny et al., 2022).

This helps to further investigate and understand quantitative data by discovering reasons for the outcome of a study – answering the why question behind statistics.

The exploratory nature of qualitative research helps to generate hypotheses that can then be tested quantitatively (Busetto et al., 2020).

To design hypotheses, theory must be researched using qualitative methods to find out what is important in order to begin research.

For example, by conducting interviews or focus groups with key stakeholders to discover what is important to them.

Examples of qualitative research questions include:

- How does stress influence young adults’ behavior?

- What factors influence students’ school attendance rates in developed countries?

- How do adults interpret binge drinking in the UK?

- What are the psychological impacts of cervical cancer screening in women?

- How can mental health lessons be integrated into the school curriculum?

Collecting Qualitative Data

There are four main research design methods used to collect qualitative data: observations, interviews, focus groups, and ethnography.

Observations

This method involves watching and recording phenomena as they occur in nature. Observation can be divided into two types: participant and non-participant observation.

In participant observation, the researcher actively participates in the situation/events being observed.

In non-participant observation, the researcher is not an active part of the observation and tries not to influence the behaviors they are observing (Busetto et al., 2020).

Observations can be covert (participants are unaware that a researcher is observing them) or overt (participants are aware of the researcher’s presence and know they are being observed).

However, awareness of an observer’s presence may influence participants’ behavior.

Interviews give researchers a window into the world of a participant by seeking their account of an event, situation, or phenomenon. They are usually conducted on a one-to-one basis and can be distinguished according to the level at which they are structured (Punch, 2013).

Structured interviews involve predetermined questions and sequences to ensure replicability and comparability. However, they are unable to explore emerging issues.

Informal interviews consist of spontaneous, casual conversations which are closer to the truth of a phenomenon. However, information is gathered using quick notes made by the researcher and is therefore subject to recall bias.

Semi-structured interviews have a flexible structure, phrasing, and placement so emerging issues can be explored (Denny & Weckesser, 2022).

The use of probing questions and clarification can lead to a detailed understanding, but semi-structured interviews can be time-consuming and subject to interviewer bias.

Focus groups

Similar to interviews, focus groups elicit a rich and detailed account of an experience. However, focus groups are more dynamic since participants with shared characteristics construct this account together (Denny & Weckesser, 2022).

A shared narrative is built between participants to capture a group experience shaped by a shared context.

The researcher takes on the role of a moderator, who will establish ground rules and guide the discussion by following a topic guide to focus the group discussions.

Typically, focus groups have 4-10 participants as a discussion can be difficult to facilitate with more than this, and this number allows everyone the time to speak.

Ethnography

Ethnography is a methodology used to study a group of people’s behaviors and social interactions in their environment (Reeves et al., 2008).

Data are collected using methods such as observations, field notes, or structured/ unstructured interviews.

The aim of ethnography is to provide detailed, holistic insights into people’s behavior and perspectives within their natural setting. In order to achieve this, researchers immerse themselves in a community or organization.

Due to the flexibility and real-world focus of ethnography, researchers are able to gather an in-depth, nuanced understanding of people’s experiences, knowledge and perspectives that are influenced by culture and society.

In order to develop a representative picture of a particular culture/ context, researchers must conduct extensive field work.

This can be time-consuming as researchers may need to immerse themselves into a community/ culture for a few days, or possibly a few years.

Qualitative Data Analysis Methods

Different methods can be used for analyzing qualitative data. The researcher chooses based on the objectives of their study.

The researcher plays a key role in the interpretation of data, making decisions about the coding, theming, decontextualizing, and recontextualizing of data (Starks & Trinidad, 2007).

Grounded theory

Grounded theory is a qualitative method specifically designed to inductively generate theory from data. It was developed by Glaser and Strauss in 1967 (Glaser & Strauss, 2017).

This methodology aims to develop theories (rather than test hypotheses) that explain a social process, action, or interaction (Petty et al., 2012). To inform the developing theory, data collection and analysis run simultaneously.

There are three key types of coding used in grounded theory: initial (open), intermediate (axial), and advanced (selective) coding.

Throughout the analysis, memos should be created to document methodological and theoretical ideas about the data. Data should be collected and analyzed until data saturation is reached and a theory is developed.

Content analysis

Content analysis was first used in the early twentieth century to analyze textual materials such as newspapers and political speeches.

Content analysis is a research method used to identify and analyze the presence and patterns of themes, concepts, or words in data (Vaismoradi et al., 2013).

This research method can be used to analyze data in different formats, which can be written, oral, or visual.

The goal of content analysis is to develop themes that capture the underlying meanings of data (Schreier, 2012).

Qualitative content analysis can be used to validate existing theories, support the development of new models and theories, and provide in-depth descriptions of particular settings or experiences.

The following six steps provide a guideline for how to conduct qualitative content analysis.

- Define a Research Question : To start content analysis, a clear research question should be developed.

- Identify and Collect Data : Establish the inclusion criteria for your data. Find the relevant sources to analyze.

- Define the Unit or Theme of Analysis : Categorize the content into themes. Themes can be a word, phrase, or sentence.

- Develop Rules for Coding your Data : Define a set of coding rules to ensure that all data are coded consistently.

- Code the Data : Follow the coding rules to categorize data into themes.

- Analyze the Results and Draw Conclusions : Examine the data to identify patterns and draw conclusions in relation to your research question.

Discourse analysis

Discourse analysis is a research method used to study written/ spoken language in relation to its social context (Wood & Kroger, 2000).

In discourse analysis, the researcher interprets details of language materials and the context in which it is situated.

Discourse analysis aims to understand the functions of language (how language is used in real life) and how meaning is conveyed by language in different contexts. Researchers use discourse analysis to investigate social groups and how language is used to achieve specific communication goals.

Different methods of discourse analysis can be used depending on the aims and objectives of a study. However, the following steps provide a guideline on how to conduct discourse analysis.

- Define the Research Question : Develop a relevant research question to frame the analysis.

- Gather Data and Establish the Context : Collect research materials (e.g., interview transcripts, documents). Gather factual details and review the literature to construct a theory about the social and historical context of your study.

- Analyze the Content : Closely examine various components of the text, such as the vocabulary, sentences, paragraphs, and structure of the text. Identify patterns relevant to the research question to create codes, then group these into themes.

- Review the Results : Reflect on the findings to examine the function of the language, and the meaning and context of the discourse.

Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis is a method used to identify, interpret, and report patterns in data, such as commonalities or contrasts.

Although the origin of thematic analysis can be traced back to the early twentieth century, understanding and clarity of thematic analysis is attributed to Braun and Clarke (2006).

Thematic analysis aims to develop themes (patterns of meaning) across a dataset to address a research question.

In thematic analysis, qualitative data is gathered using techniques such as interviews, focus groups, and questionnaires. Audio recordings are transcribed. The dataset is then explored and interpreted by a researcher to identify patterns.

This occurs through the rigorous process of data familiarisation, coding, theme development, and revision. These identified patterns provide a summary of the dataset and can be used to address a research question.

Themes are developed by exploring the implicit and explicit meanings within the data. Two different approaches are used to generate themes: inductive and deductive.

An inductive approach allows themes to emerge from the data. In contrast, a deductive approach uses existing theories or knowledge to apply preconceived ideas to the data.

Phases of Thematic Analysis

Braun and Clarke (2006) provide a guide of the six phases of thematic analysis. These phases can be applied flexibly to fit research questions and data.

Template analysis

Template analysis refers to a specific method of thematic analysis which uses hierarchical coding (Brooks et al., 2014).

Template analysis is used to analyze textual data, for example, interview transcripts or open-ended responses on a written questionnaire.

To conduct template analysis, a coding template must be developed (usually from a subset of the data) and subsequently revised and refined. This template represents the themes identified by researchers as important in the dataset.

Codes are ordered hierarchically within the template, with the highest-level codes demonstrating overarching themes in the data and lower-level codes representing constituent themes with a narrower focus.

A guideline for the main procedural steps for conducting template analysis is outlined below.

- Familiarization with the Data : Read (and reread) the dataset in full. Engage, reflect, and take notes on data that may be relevant to the research question.

- Preliminary Coding : Identify initial codes using guidance from the a priori codes, identified before the analysis as likely to be beneficial and relevant to the analysis.

- Organize Themes : Organize themes into meaningful clusters. Consider the relationships between the themes both within and between clusters.

- Produce an Initial Template : Develop an initial template. This may be based on a subset of the data.

- Apply and Develop the Template : Apply the initial template to further data and make any necessary modifications. Refinements of the template may include adding themes, removing themes, or changing the scope/title of themes.

- Finalize Template : Finalize the template, then apply it to the entire dataset.

Frame analysis

Frame analysis is a comparative form of thematic analysis which systematically analyzes data using a matrix output.

Ritchie and Spencer (1994) developed this set of techniques to analyze qualitative data in applied policy research. Frame analysis aims to generate theory from data.

Frame analysis encourages researchers to organize and manage their data using summarization.

This results in a flexible and unique matrix output, in which individual participants (or cases) are represented by rows and themes are represented by columns.

Each intersecting cell is used to summarize findings relating to the corresponding participant and theme.

Frame analysis has five distinct phases which are interrelated, forming a methodical and rigorous framework.

- Familiarization with the Data : Familiarize yourself with all the transcripts. Immerse yourself in the details of each transcript and start to note recurring themes.

- Develop a Theoretical Framework : Identify recurrent/ important themes and add them to a chart. Provide a framework/ structure for the analysis.

- Indexing : Apply the framework systematically to the entire study data.

- Summarize Data in Analytical Framework : Reduce the data into brief summaries of participants’ accounts.

- Mapping and Interpretation : Compare themes and subthemes and check against the original transcripts. Group the data into categories and provide an explanation for them.

Preventing Bias in Qualitative Research

To evaluate qualitative studies, the CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) checklist for qualitative studies can be used to ensure all aspects of a study have been considered (CASP, 2018).

The quality of research can be enhanced and assessed using criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, co-coding, and member-checking.

Co-coding

Relying on only one researcher to interpret rich and complex data may risk key insights and alternative viewpoints being missed. Therefore, coding is often performed by multiple researchers.

A common strategy must be defined at the beginning of the coding process (Busetto et al., 2020). This includes establishing a useful coding list and finding a common definition of individual codes.

Transcripts are initially coded independently by researchers and then compared and consolidated to minimize error or bias and to bring confirmation of findings.

Member checking

Member checking (or respondent validation) involves checking back with participants to see if the research resonates with their experiences (Russell & Gregory, 2003).

Data can be returned to participants after data collection or when results are first available. For example, participants may be provided with their interview transcript and asked to verify whether this is a complete and accurate representation of their views.

Participants may then clarify or elaborate on their responses to ensure they align with their views (Shenton, 2004).

This feedback becomes part of data collection and ensures accurate descriptions/ interpretations of phenomena (Mays & Pope, 2000).

Reflexivity in qualitative research

Reflexivity typically involves examining your own judgments, practices, and belief systems during data collection and analysis. It aims to identify any personal beliefs which may affect the research.

Reflexivity is essential in qualitative research to ensure methodological transparency and complete reporting. This enables readers to understand how the interaction between the researcher and participant shapes the data.

Depending on the research question and population being researched, factors that need to be considered include the experience of the researcher, how the contact was established and maintained, age, gender, and ethnicity.

These details are important because, in qualitative research, the researcher is a dynamic part of the research process and actively influences the outcome of the research (Boeije, 2014).

Reflexivity Example

Who you are and your characteristics influence how you collect and analyze data. Here is an example of a reflexivity statement for research on smoking. I am a 30-year-old white female from a middle-class background. I live in the southwest of England and have been educated to master’s level. I have been involved in two research projects on oral health. I have never smoked, but I have witnessed how smoking can cause ill health from my volunteering in a smoking cessation clinic. My research aspirations are to help to develop interventions to help smokers quit.

Establishing Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research

Trustworthiness is a concept used to assess the quality and rigor of qualitative research. Four criteria are used to assess a study’s trustworthiness: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability.

Credibility in Qualitative Research

Credibility refers to how accurately the results represent the reality and viewpoints of the participants.

To establish credibility in research, participants’ views and the researcher’s representation of their views need to align (Tobin & Begley, 2004).

To increase the credibility of findings, researchers may use data source triangulation, investigator triangulation, peer debriefing, or member checking (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Transferability in Qualitative Research

Transferability refers to how generalizable the findings are: whether the findings may be applied to another context, setting, or group (Tobin & Begley, 2004).

Transferability can be enhanced by giving thorough and in-depth descriptions of the research setting, sample, and methods (Nowell et al., 2017).

Dependability in Qualitative Research

Dependability is the extent to which the study could be replicated under similar conditions and the findings would be consistent.

Researchers can establish dependability using methods such as audit trails so readers can see the research process is logical and traceable (Koch, 1994).

Confirmability in Qualitative Research

Confirmability is concerned with establishing that there is a clear link between the researcher’s interpretations/ findings and the data.

Researchers can achieve confirmability by demonstrating how conclusions and interpretations were arrived at (Nowell et al., 2017).

This enables readers to understand the reasoning behind the decisions made.

Audit Trails in Qualitative Research

An audit trail provides evidence of the decisions made by the researcher regarding theory, research design, and data collection, as well as the steps they have chosen to manage, analyze, and report data.

The researcher must provide a clear rationale to demonstrate how conclusions were reached in their study.

A clear description of the research path must be provided to enable readers to trace through the researcher’s logic (Halpren, 1983).

Researchers should maintain records of the raw data, field notes, transcripts, and a reflective journal in order to provide a clear audit trail.

Discovery of unexpected data

Open-ended questions in qualitative research mean the researcher can probe an interview topic and enable the participant to elaborate on responses in an unrestricted manner.

This allows unexpected data to emerge, which can lead to further research into that topic.

Flexibility

Data collection and analysis can be modified and adapted to take the research in a different direction if new ideas or patterns emerge in the data.

This enables researchers to investigate new opportunities while firmly maintaining their research goals.

Naturalistic settings

The behaviors of participants are recorded in real-world settings. Studies that use real-world settings have high ecological validity since participants behave more authentically.

Limitations

Time-consuming .

Qualitative research results in large amounts of data which often need to be transcribed and analyzed manually.

Even when software is used, transcription can be inaccurate, and using software for analysis can result in many codes which need to be condensed into themes.

Subjectivity

The researcher has an integral role in collecting and interpreting qualitative data. Therefore, the conclusions reached are from their perspective and experience.

Consequently, interpretations of data from another researcher may vary greatly.

Limited generalizability

The aim of qualitative research is to provide a detailed, contextualized understanding of an aspect of the human experience from a relatively small sample size.

Despite rigorous analysis procedures, conclusions drawn cannot be generalized to the wider population since data may be biased or unrepresentative.

Therefore, results are only applicable to a small group of the population.

Extraneous variables

Qualitative research is often conducted in real-world settings. This may cause results to be unreliable since extraneous variables may affect the data, for example:

- Situational variables : different environmental conditions may influence participants’ behavior in a study. The random variation in factors (such as noise or lighting) may be difficult to control in real-world settings.

- Participant characteristics : this includes any characteristics that may influence how a participant answers/ behaves in a study. This may include a participant’s mood, gender, age, ethnicity, sexual identity, IQ, etc.

- Experimenter effect : experimenter effect refers to how a researcher’s unintentional influence can change the outcome of a study. This occurs when (i) their interactions with participants unintentionally change participants’ behaviors or (ii) due to errors in observation, interpretation, or analysis.

What sample size should qualitative research be?

The sample size for qualitative studies has been recommended to include a minimum of 12 participants to reach data saturation (Braun, 2013).

Are surveys qualitative or quantitative?

Surveys can be used to gather information from a sample qualitatively or quantitatively. Qualitative surveys use open-ended questions to gather detailed information from a large sample using free text responses.

The use of open-ended questions allows for unrestricted responses where participants use their own words, enabling the collection of more in-depth information than closed-ended questions.

In contrast, quantitative surveys consist of closed-ended questions with multiple-choice answer options. Quantitative surveys are ideal to gather a statistical representation of a population.

What are the ethical considerations of qualitative research?

Before conducting a study, you must think about any risks that could occur and take steps to prevent them. Participant Protection : Researchers must protect participants from physical and mental harm. This means you must not embarrass, frighten, offend, or harm participants. Transparency : Researchers are obligated to clearly communicate how they will collect, store, analyze, use, and share the data. Confidentiality : You need to consider how to maintain the confidentiality and anonymity of participants’ data.

What is triangulation in qualitative research?

Triangulation refers to the use of several approaches in a study to comprehensively understand phenomena. This method helps to increase the validity and credibility of research findings.

Types of triangulation include method triangulation (using multiple methods to gather data); investigator triangulation (multiple researchers for collecting/ analyzing data), theory triangulation (comparing several theoretical perspectives to explain a phenomenon), and data source triangulation (using data from various times, locations, and people; Carter et al., 2014).

Why is qualitative research important?

Qualitative research allows researchers to describe and explain the social world. The exploratory nature of qualitative research helps to generate hypotheses that can then be tested quantitatively.

In qualitative research, participants are able to express their thoughts, experiences, and feelings without constraint.

Additionally, researchers are able to follow up on participants’ answers in real-time, generating valuable discussion around a topic. This enables researchers to gain a nuanced understanding of phenomena which is difficult to attain using quantitative methods.

What is coding data in qualitative research?

Coding data is a qualitative data analysis strategy in which a section of text is assigned with a label that describes its content.

These labels may be words or phrases which represent important (and recurring) patterns in the data.

This process enables researchers to identify related content across the dataset. Codes can then be used to group similar types of data to generate themes.

What is the difference between qualitative and quantitative research?

Qualitative research involves the collection and analysis of non-numerical data in order to understand experiences and meanings from the participant’s perspective.

This can provide rich, in-depth insights on complicated phenomena. Qualitative data may be collected using interviews, focus groups, or observations.

In contrast, quantitative research involves the collection and analysis of numerical data to measure the frequency, magnitude, or relationships of variables. This can provide objective and reliable evidence that can be generalized to the wider population.

Quantitative data may be collected using closed-ended questionnaires or experiments.

What is trustworthiness in qualitative research?

Trustworthiness is a concept used to assess the quality and rigor of qualitative research. Four criteria are used to assess a study’s trustworthiness: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability.

Credibility refers to how accurately the results represent the reality and viewpoints of the participants. Transferability refers to whether the findings may be applied to another context, setting, or group.

Dependability is the extent to which the findings are consistent and reliable. Confirmability refers to the objectivity of findings (not influenced by the bias or assumptions of researchers).

What is data saturation in qualitative research?

Data saturation is a methodological principle used to guide the sample size of a qualitative research study.

Data saturation is proposed as a necessary methodological component in qualitative research (Saunders et al., 2018) as it is a vital criterion for discontinuing data collection and/or analysis.

The intention of data saturation is to find “no new data, no new themes, no new coding, and ability to replicate the study” (Guest et al., 2006). Therefore, enough data has been gathered to make conclusions.

Why is sampling in qualitative research important?

In quantitative research, large sample sizes are used to provide statistically significant quantitative estimates.

This is because quantitative research aims to provide generalizable conclusions that represent populations.

However, the aim of sampling in qualitative research is to gather data that will help the researcher understand the depth, complexity, variation, or context of a phenomenon. The small sample sizes in qualitative studies support the depth of case-oriented analysis.

Boeije, H. (2014). Analysis in qualitative research. Sage.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology , 3 (2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brooks, J., McCluskey, S., Turley, E., & King, N. (2014). The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qualitative Research in Psychology , 12 (2), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2014.955224

Busetto, L., Wick, W., & Gumbinger, C. (2020). How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurological research and practice , 2 (1), 14-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology nursing forum , 41 (5), 545–547. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.545-547

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP Checklist: 10 questions to help you make sense of a Qualitative research. https://casp-uk.net/images/checklist/documents/CASP-Qualitative-Studies-Checklist/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf Accessed: March 15 2023

Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Successful Qualitative Research , 1-400.

Denny, E., & Weckesser, A. (2022). How to do qualitative research?: Qualitative research methods. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology , 129 (7), 1166-1167. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17150

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). The discovery of grounded theory. The Discovery of Grounded Theory , 1–18. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203793206-1

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18 (1), 59-82. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903

Halpren, E. S. (1983). Auditing naturalistic inquiries: The development and application of a model (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Indiana University, Bloomington.

Hammarberg, K., Kirkman, M., & de Lacey, S. (2016). Qualitative research methods: When to use them and how to judge them. Human Reproduction , 31 (3), 498–501. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dev334

Koch, T. (1994). Establishing rigour in qualitative research: The decision trail. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 19, 976–986. doi:10.1111/ j.1365-2648.1994.tb01177.x

Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ, 320(7226), 50–52.

Minichiello, V. (1990). In-Depth Interviewing: Researching People. Longman Cheshire.

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16 (1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

Petty, N. J., Thomson, O. P., & Stew, G. (2012). Ready for a paradigm shift? part 2: Introducing qualitative research methodologies and methods. Manual Therapy , 17 (5), 378–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2012.03.004

Punch, K. F. (2013). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. London: Sage

Reeves, S., Kuper, A., & Hodges, B. D. (2008). Qualitative research methodologies: Ethnography. BMJ , 337 (aug07 3). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1020

Russell, C. K., & Gregory, D. M. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research studies. Evidence Based Nursing, 6 (2), 36–40.

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & quantity , 52 (4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

Scarduzio, J. A. (2017). Emic approach to qualitative research. The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods, 1–2 . https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0082

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice / Margrit Schreier.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 , 63–75.

Starks, H., & Trinidad, S. B. (2007). Choose your method: a comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis, and grounded theory. Qualitative health research , 17 (10), 1372–1380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307307031

Tenny, S., Brannan, J. M., & Brannan, G. D. (2022). Qualitative Study. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

Tobin, G. A., & Begley, C. M. (2004). Methodological rigour within a qualitative framework. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48, 388–396. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03207.x

Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & health sciences , 15 (3), 398-405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048

Wood L. A., Kroger R. O. (2000). Doing discourse analysis: Methods for studying action in talk and text. Sage.

Yilmaz, K. (2013). Comparison of Quantitative and Qualitative Research Traditions: epistemological, theoretical, and methodological differences. European journal of education , 48 (2), 311-325. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12014

Qualitative Research Design: Start

Qualitative Research Design

What is Qualitative research design?

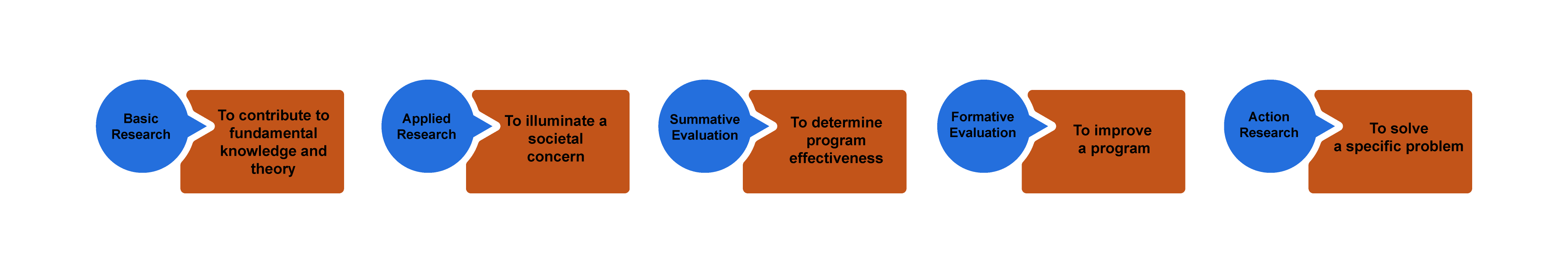

Qualitative research is a type of research that explores and provides deeper insights into real-world problems. Instead of collecting numerical data points or intervening or introducing treatments just like in quantitative research, qualitative research helps generate hypotheses as well as further investigate and understand quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences, perceptions, and behavior. It answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much . It could be structured as a stand-alone study, purely relying on qualitative data or it could be part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research. Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research, which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis. Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

While qualitative and quantitative approaches are different, they are not necessarily opposites, and they are certainly not mutually exclusive. For instance, qualitative research can help expand and deepen understanding of data or results obtained from quantitative analysis. For example, say a quantitative analysis has determined that there is a correlation between length of stay and level of patient satisfaction, but why does this correlation exist? This dual-focus scenario shows one way in which qualitative and quantitative research could be integrated together.

Research Paradigms

- Positivist versus Post-Positivist

- Social Constructivist (this paradigm/ideology mostly birth qualitative studies)

Events Relating to the Qualitative Research and Community Engagement Workshops @ CMU Libraries

CMU Libraries is committed to helping members of our community become data experts. To that end, CMU is offering public facing workshops that discuss Qualitative Research, Coding, and Community Engagement best practices.

The following workshops are a part of a broader series on using data. Please follow the links to register for the events.

Qualitative Coding

Using Community Data to improve Outcome (Grant Writing)

Survey Design

Upcoming Event: March 21st, 2024 (12:00pm -1:00 pm)

Community Engagement and Collaboration Event

Join us for an event to improve, build on and expand the connections between Carnegie Mellon University resources and the Pittsburgh community. CMU resources such as the Libraries and Sustainability Initiative can be leveraged by users not affiliated with the university, but barriers can prevent them from fully engaging.

The conversation features representatives from CMU departments and local organizations about the community engagement efforts currently underway at CMU and opportunities to improve upon them. Speakers will highlight current and ongoing projects and share resources to support future collaboration.

Event Moderators:

Taiwo Lasisi, CLIR Postdoctoral Fellow in Community Data Literacy, Carnegie Mellon University Libraries

Emma Slayton, Data Curation, Visualization, & GIS Specialist, Carnegie Mellon University Libraries

Nicky Agate , Associate Dean for Academic Engagement, Carnegie Mellon University Libraries

Chelsea Cohen , The University’s Executive fellow for community engagement, Carnegie Mellon University

Sarah Ceurvorst , Academic Pathways Manager, Program Director, LEAP (Leadership, Excellence, Access, Persistence) Carnegie Mellon University

Julia Poeppibg , Associate Director of Partnership Development, Information Systems, Carnegie Mellon University

Scott Wolovich , Director of New Sun Rising, Pittsburgh

Additional workshops and events will be forthcoming. Watch this space for updates.

Workshop Organizer

Qualitative Research Methods

What are Qualitative Research methods?

Qualitative research adopts numerous methods or techniques including interviews, focus groups, and observation. Interviews may be unstructured, with open-ended questions on a topic and the interviewer adapts to the responses. Structured interviews have a predetermined number of questions that every participant is asked. It is usually one-on-one and is appropriate for sensitive topics or topics needing an in-depth exploration. Focus groups are often held with 8-12 target participants and are used when group dynamics and collective views on a topic are desired. Researchers can be participant observers to share the experiences of the subject or non-participant or detached observers.

What constitutes a good research question? Does the question drive research design choices?

According to Doody and Bailey (2014);

We can only develop a good research question by consulting relevant literature, colleagues, and supervisors experienced in the area of research. (inductive interactions).

Helps to have a directed research aim and objective.

Researchers should not be “ research trendy” and have enough evidence. This is why research objectives are important. It helps to take time, and resources into consideration.

Research questions can be developed from theoretical knowledge, previous research or experience, or a practical need at work (Parahoo 2014). They have numerous roles, such as identifying the importance of the research and providing clarity of purpose for the research, in terms of what the research intends to achieve in the end.

Qualitative Research Questions

What constitutes a good Qualitative research question?

A good qualitative question answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much. It could be structured as a stand-alone study, purely relying on qualitative data or it could be part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences, perceptions and behavior.

Examples of good Qualitative Research Questions:

What are people's thoughts on the new library?

How does it feel to be a first-generation student attending college?

Difference example (between Qualitative and Quantitative research questions):

How many college students signed up for the new semester? (Quan)

How do college students feel about the new semester? What are their experiences so far? (Qual)

- Qualitative Research Design Workshop Powerpoint

Foley G, Timonen V. Using Grounded Theory Method to Capture and Analyze Health Care Experiences. Health Serv Res. 2015 Aug;50(4):1195-210. [ PMC free article: PMC4545354 ] [ PubMed: 25523315 ]

Devers KJ. How will we know "good" qualitative research when we see it? Beginning the dialogue in health services research. Health Serv Res. 1999 Dec;34(5 Pt 2):1153-88. [ PMC free article: PMC1089058 ] [ PubMed: 10591278 ]

Huston P, Rowan M. Qualitative studies. Their role in medical research. Can Fam Physician. 1998 Nov;44:2453-8. [ PMC free article: PMC2277956 ] [ PubMed: 9839063 ]

Corner EJ, Murray EJ, Brett SJ. Qualitative, grounded theory exploration of patients' experience of early mobilisation, rehabilitation and recovery after critical illness. BMJ Open. 2019 Feb 24;9(2):e026348. [ PMC free article: PMC6443050 ] [ PubMed: 30804034 ]

Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018 Dec;24(1):9-18. [ PMC free article: PMC5774281 ] [ PubMed: 29199486 ]

Houghton C, Murphy K, Meehan B, Thomas J, Brooker D, Casey D. From screening to synthesis: using nvivo to enhance transparency in qualitative evidence synthesis. J Clin Nurs. 2017 Mar;26(5-6):873-881. [ PubMed: 27324875 ]

Soratto J, Pires DEP, Friese S. Thematic content analysis using ATLAS.ti software: Potentialities for researchs in health. Rev Bras Enferm. 2020;73(3):e20190250. [ PubMed: 32321144 ]

Zamawe FC. The Implication of Using NVivo Software in Qualitative Data Analysis: Evidence-Based Reflections. Malawi Med J. 2015 Mar;27(1):13-5. [ PMC free article: PMC4478399 ] [ PubMed: 26137192 ]

Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018 Dec;24(1):120-124. [ PMC free article: PMC8816392 ] [ PubMed: 29202616 ]

Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. The coding manual for qualitative researchers, 1-440.

O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014 Sep;89(9):1245-51. [ PubMed: 24979285 ]

Palermo C, King O, Brock T, Brown T, Crampton P, Hall H, Macaulay J, Morphet J, Mundy M, Oliaro L, Paynter S, Williams B, Wright C, E Rees C. Setting priorities for health education research: A mixed methods study. Med Teach. 2019 Sep;41(9):1029-1038. [ PubMed: 31141390 ]

- Last Updated: Feb 14, 2024 4:25 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cmu.edu/c.php?g=1346006

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a type of research methodology that focuses on exploring and understanding people’s beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and experiences through the collection and analysis of non-numerical data. It seeks to answer research questions through the examination of subjective data, such as interviews, focus groups, observations, and textual analysis.

Qualitative research aims to uncover the meaning and significance of social phenomena, and it typically involves a more flexible and iterative approach to data collection and analysis compared to quantitative research. Qualitative research is often used in fields such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative Research Methods are as follows:

One-to-One Interview

This method involves conducting an interview with a single participant to gain a detailed understanding of their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. One-to-one interviews can be conducted in-person, over the phone, or through video conferencing. The interviewer typically uses open-ended questions to encourage the participant to share their thoughts and feelings. One-to-one interviews are useful for gaining detailed insights into individual experiences.

Focus Groups

This method involves bringing together a group of people to discuss a specific topic in a structured setting. The focus group is led by a moderator who guides the discussion and encourages participants to share their thoughts and opinions. Focus groups are useful for generating ideas and insights, exploring social norms and attitudes, and understanding group dynamics.

Ethnographic Studies

This method involves immersing oneself in a culture or community to gain a deep understanding of its norms, beliefs, and practices. Ethnographic studies typically involve long-term fieldwork and observation, as well as interviews and document analysis. Ethnographic studies are useful for understanding the cultural context of social phenomena and for gaining a holistic understanding of complex social processes.

Text Analysis

This method involves analyzing written or spoken language to identify patterns and themes. Text analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative text analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Text analysis is useful for understanding media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

This method involves an in-depth examination of a single person, group, or event to gain an understanding of complex phenomena. Case studies typically involve a combination of data collection methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case. Case studies are useful for exploring unique or rare cases, and for generating hypotheses for further research.

Process of Observation

This method involves systematically observing and recording behaviors and interactions in natural settings. The observer may take notes, use audio or video recordings, or use other methods to document what they see. Process of observation is useful for understanding social interactions, cultural practices, and the context in which behaviors occur.

Record Keeping

This method involves keeping detailed records of observations, interviews, and other data collected during the research process. Record keeping is essential for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the data, and for providing a basis for analysis and interpretation.

This method involves collecting data from a large sample of participants through a structured questionnaire. Surveys can be conducted in person, over the phone, through mail, or online. Surveys are useful for collecting data on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, and for identifying patterns and trends in a population.

Qualitative data analysis is a process of turning unstructured data into meaningful insights. It involves extracting and organizing information from sources like interviews, focus groups, and surveys. The goal is to understand people’s attitudes, behaviors, and motivations

Qualitative Research Analysis Methods

Qualitative Research analysis methods involve a systematic approach to interpreting and making sense of the data collected in qualitative research. Here are some common qualitative data analysis methods:

Thematic Analysis

This method involves identifying patterns or themes in the data that are relevant to the research question. The researcher reviews the data, identifies keywords or phrases, and groups them into categories or themes. Thematic analysis is useful for identifying patterns across multiple data sources and for generating new insights into the research topic.

Content Analysis