What is Developmental Psychology?

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

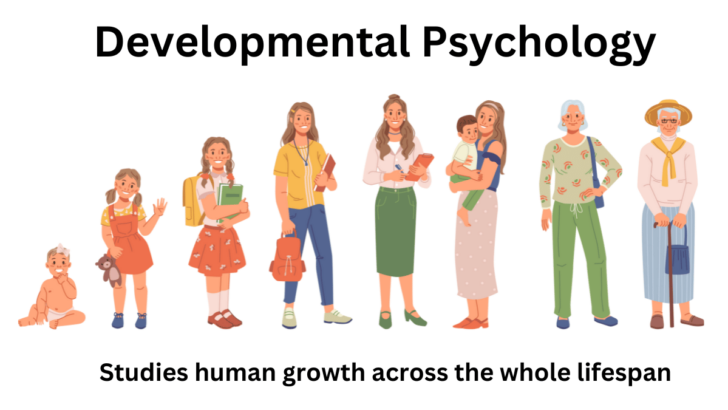

Developmental psychology is a scientific approach that aims to explain growth, change, and consistency though the lifespan. Developmental psychology examines how thinking, feeling, and behavior change throughout a person’s life.

A significant proportion of theories within this discipline focus on development during childhood, as this is the period during an individual’s lifespan when the most change occurs.

Developmental psychologists study a wide range of theoretical areas, such as biological, social, emotion, and cognitive processes.

Empirical research in this area tends to be dominated by psychologists from Western cultures such as North American and Europe, although during the 1980s Japanese researchers began making a valid contribution to the field.

- Maturation in psychology refers to the natural developmental process driven by genetics, leading to physical, behavioral, and psychological growth independent of learning or experience.

- The idiographic approach focuses on understanding unique, individual differences in experiences or behaviors, often using qualitative methods.

- Normative development in psychology refers to the typical sequence and timing of developmental milestones that most people experience within a population.

The three goals of developmental psychology are to describe, explain, and optimize development (Baltes, Reese, & Lipsitt, 1980).

Finally, developmental psychologists hope to optimize development, and apply their theories to help people in practical situations (e.g. help parents develop secure attachments with their children).

Continuity vs. Discontinuity in Human Development

Think about how children become adults. Is there a predictable pattern they follow regarding thought and language and social development? Do children go through gradual changes or are they abrupt changes?

Normative development is typically viewed as a continual and cumulative process. The continuity view says that development is a smooth and gradual accumulation of abilities, with one stage flowing seamlessly into the next.

Children become more skillful in thinking, talking, or acting much the same way as they get taller.

It assumes that changes are incremental, with skills and knowledge building upon what was previously learned. The analogy often used to describe this perspective is viewing development as a slope or ramp, gradually inclining upwards.

The discontinuity view sees development as a more abrupt-a succession of changes that produce different behaviors in different age-specific life periods called stages. Biological changes provide the potential for these changes.

These stages are believed to be qualitatively different, each bringing a dramatic shift in abilities or behaviors.

Theorists like Jean Piaget and Erik Erikson support this perspective. They argue that children pass through distinct stages at certain ages, and the qualities of each stage are significantly different from those of other stages. This can be visualized as steps on a staircase.

We often hear people talking about children going through “stages” in life (i.e., “sensorimotor stage.”). These are called developmental stages-periods of life initiated by distinct transitions in physical or psychological functioning.

Psychologists of the discontinuity view believe that people go through the same stages, in the same order, but not necessarily at the same rate.

Stability vs. Change in Human Development

Stability implies personality traits present during infancy endure throughout the lifespan. It emphasizes the importance of early experiences on future development, suggesting that early childhood experiences play a significant role in determining adult personality traits and behaviors.

For example, a child who is cheerful and outgoing will likely grow into an adult with similar personality traits. Stability theorists believe that change is relatively difficult once initial personality traits have been established.

In contrast, change theorists argue that family interactions, school experiences, and acculturation modify personalities.

It implies that our behaviors, thoughts, and emotions are malleable and can be influenced by experiences and environments over time. This perspective suggests that it is equally likely for an introverted child to become an extroverted adult, depending on various factors such as life experiences, education, or trauma.

This capacity for change is called plasticity. For example, Rutter (1981) discovered that somber babies living in understaffed orphanages often become cheerful and affectionate when placed in socially stimulating adoptive homes.

Nature vs. Nurture

When trying to explain development, it is important to consider the relative contribution of both nature and nurture . Developmental psychology seeks to answer two big questions about heredity and environment:

- How much weight does each contribute?

- How do nature and nurture interact?

Nature refers to the process of biological maturation, inheritance, and maturation. One of the reasons why the development of human beings is so similar is because our common specifies heredity (DNA) guides all of us through many of the same developmental changes at about the same points in our lives.

Nurture refers to the impact of the environment, which involves the process of learning through experiences.

There are two effective ways to study nature-nurture.

- Twin studies: Identical twins have the same genotype, and fraternal twins have an average of 50% of their genes in common.

- Adoption studies: Similarities with the biological family support nature, while similarities with the adoptive family support nurture.

Historical Origins

Developmental psychology as a discipline did not exist until after the industrial revolution when the need for an educated workforce led to the social construction of childhood as a distinct stage in a person’s life.

The notion of childhood originates in the Western world and this is why the early research derives from this location. Initially, developmental psychologists were interested in studying the mind of the child so that education and learning could be more effective.

Developmental changes during adulthood are an even more recent area of study. This is mainly due to advances in medical science, enabling people to live to old age.

Charles Darwin is credited with conducting the first systematic study of developmental psychology. In 1877 he published a short paper detailing the development of innate forms of communication-based on scientific observations of his infant son, Doddy.

However, the emergence of developmental psychology as a specific discipline can be traced back to 1882 when Wilhelm Preyer (a German physiologist) published a book entitled The Mind of the Child .

In the book, Preyer describes the development of his own daughter from birth to two and a half years. Importantly, Preyer used rigorous scientific procedures throughout studying the many abilities of his daughter.

In 1888 Preyer’s publication was translated into English, by which time developmental psychology as a discipline was fully established with a further 47 empirical studies from Europe, North America and Britain also published to facilitate the dissemination of knowledge in the field.

During the 1900s three key figures have dominated the field with their extensive theories of human development, namely Jean Piaget (1896-1980), Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) and John Bowlby (1907-1990). Indeed, much of the current research continues to be influenced by these three theorists.

Baltes, P. B., Reese, H., & Lipsett, L. (1980) Lifespan developmental psychology, Annual Review of Pyschology 31 : 65 – 110.

Darwin, C. (1877). A Biographical Sketch of an Infant. Mind , 2, 285-294.

Preyer, W.T. (1882). Die Seele des Kindes: Beobachtungen über die geistige Entwicklung des Menschen in den ersten Lebensjahren .Grieben, Leipzig,

Preyer, W.T. (1888). The soul of the child: observations on the mental development of man in the first years of life .

Rutter, M. (1981). STRESS, COPING AND DEVELOPMENT: SOME ISSUES AND SOME QUESTIONS*. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 22(4) , 323-356.

Developmental Psychology 101: Theories, Stages, & Research

You can imagine how vast this field of psychology is if it has to cover the whole of life, from birth through death.

Just like any other area of psychology, it has created exciting debates and given rise to fascinating case studies.

In recent years, developmental psychology has shifted to incorporate positive psychology paradigms to create a holistic lifespan approach. As an example, the knowledge gained from positive psychology can enhance the development of children in education.

In this article, you will learn a lot about different aspects of developmental psychology, including how it first emerged in history and famous theories and models.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology, including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

What is developmental psychology, 4 popular theories, stages, & models, 2 questions and research topics, fascinating case studies & research findings, a look at positive developmental psychology, applying developmental psychology in education, resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message.

Human beings change drastically over our lifetime.

The American Psychological Association (2020) defines developmental psychology as the study of physical, mental, and behavioral changes, from conception through old age.

Developmental psychology investigates biological, genetic, neurological, psychosocial, cultural, and environmental factors of human growth (Burman, 2017).

Over the years, developmental psychology has been influenced by numerous theories and models in varied branches of psychology (Burman, 2017).

History of developmental psychology

Developmental psychology first appeared as an area of study in the late 19th century (Baltes, Lindenberger, & Staudinger, 2007). Developmental psychology focused initially on child and adolescent development, and was concerned about children’s minds and learning (Hall, 1883).

There are several key figures in developmental psychology. In 1877, the famous evolutionary biologist Charles Darwin undertook the first study of developmental psychology on innate communication forms. Not long after, physiologist William Preyer (1888) published a book on the abilities of an infant.

The 1900s saw many significant people dominating the developmental psychology field with their detailed theories of development: Sigmund Freud (1923, 1961), Jean Piaget (1928), Erik Erikson (1959), Lev Vygotsky (1978), John Bowlby (1958), and Albert Bandura (1977).

By the 1920s, the scope of developmental psychology had begun to include adult development and the aging process (Thompson, 2016).

In more recent years, it has broadened further to include prenatal development (Brandon et al., 2009). Developmental psychology is now understood to encompass the complete lifespan (Baltes et al., 2007).

Each of these models has contributed to the understanding of the process of human development and growth.

Furthermore, each theory and model focuses on different aspects of development: social, emotional, psychosexual, behavioral, attachment, social learning, and many more.

Here are some of the most popular models of development that have heavily contributed to the field of developmental psychology.

1. Bowlby’s attachment styles

The seminal work of psychologist John Bowlby (1958) showcased his interest in children’s social development. Bowlby (1969, 1973, 1980) developed the most famous theory of social development, known as attachment theory .

Bowlby (1969) hypothesized that the need to form attachments is innate, embedded in all humans for survival and essential for children’s development. This instinctive bond helps ensure that children are cared for by their parent or caregiver (Bowlby, 1969, 1973, 1980).

Bowlby’s original attachment work was developed further by one of his students, Mary Ainsworth. She proposed several attachment styles between the child and the caregiver (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970).

This theory clearly illustrates the importance of attachment styles to a child’s future development. Consistent and stable caregiving results in a secure attachment style (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978). In contrast, unstable and insecure caregiving results in several negative attachment styles: ambivalent, avoidant, or disorganized (Ainsworth & Bell, 1970; Main & Solomon, 1986).

Bowlby’s theory does not consider peer group influence or how it can shape children’s personality and development (Harris, 1998).

2. Piaget’s stage theory

Jean Piaget was a French psychologist highly interested in child development. He was interested in children’s thinking and how they acquire, construct, and use their knowledge (Piaget, 1951).

Piaget’s (1951) four-stage theory of cognitive development sequences a child’s intellectual development. According to this theory, all children move through these four stages of development in the same order (Simatwa, 2010).

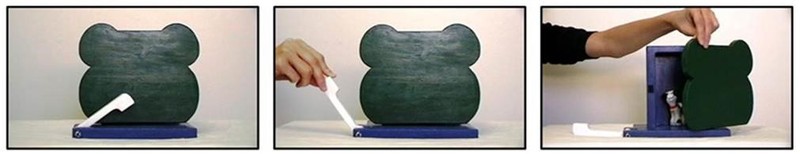

The sensorimotor stage is from birth to two years old. Behaviors are triggered by sensory stimuli and limited to simple motor responses. If an object is removed from the child’s vision, they think it no longer exists (Piaget, 1936).

The pre-operational stage occurs between two and six years old. The child learns language but cannot mentally manipulate information or understand concrete logic (Wadsworth, 1971).

The concrete operational stage takes place from 7 to 11 years old. Children begin to think more logically about factual events. Abstract or hypothetical concepts are still difficult to understand in this stage (Wadsworth, 1971).

In the formal operational stage from 12 years to adulthood, abstract thought and skills arise (Piaget, 1936).

Piaget did not consider other factors that might affect these stages or a child’s progress through them. Biological maturation and interaction with the environment can determine the rate of cognitive development in children (Papalia & Feldman, 2011). Individual differences can also dictate a child’s progress (Berger, 2014).

3. Freud’s psychosexual development theory

One of the most influential developmental theories, which encompassed psychosexual stages of development, was developed by Austrian psychiatrist Sigmund Freud (Fisher & Greenberg, 1996).

Freud concluded that childhood experiences and unconscious desires influence behavior after witnessing his female patients experiencing physical symptoms and distress with no physical cause (Breuer & Freud, 1957).

According to Freud’s psychosexual theory, child development occurs in a series of stages, each focused on different pleasure areas of the body. During each stage, the child encounters conflicts, which play a significant role in development (Silverman, 2017).

Freud’s theory of psychosexual development includes the oral, anal, phallic, latent, and genital stages. His theory suggests that the energy of the libido is focused on these different erogenous zones at each specific stage (Silverman, 2017).

Freud concluded that the successful completion of each stage leads to healthy adult development. He also suggested that a failure to progress through a stage causes fixation and developmental difficulties, such as nail biting (oral fixation) or obsessive tidiness (anal fixation; Silverman, 2017).

Freud considered personality to be formed in childhood as a child passes through these stages. Criticisms of Freud’s theory of psychosexual development include its failure to consider that personality can change and grow over an entire lifetime. Freud believed that early experiences played the most significant role in shaping development (Silverman, 2017).

4. Bandura’s social learning theory

American psychologist Albert Bandura proposed the social learning theory (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1961). Bandura did not believe that classical or operant conditioning was enough to explain learned behavior because some behaviors of children are never reinforced (Bandura, 1986). He believed that children observe, imitate, and model the behaviors and reactions of others (Bandura, 1977).

Bandura suggested that observation is critical in learning. Further, the observation does not have to be of a live actor, such as in the Bobo doll experiment (Bandura, 1986). Bandura et al. (1961) considered that learning and modeling can also occur from listening to verbal instructions on behavior performance.

Bandura’s (1977) social theory posits that both environmental and cognitive factors interact to influence development.

Bandura’s developmental theory has been criticized for not considering biological factors or children’s autonomic nervous system responses (Kevin, 1995).

Overview of theories of development – Khan Academy

Developmental psychology has given rise to many debatable questions and research topics. Here are two of the most commonly discussed.

1. Nature vs nurture debate

One of the oldest debates in the field of developmental psychology has been between nature and nurture (Levitt, 2013).

Is human development a result of hereditary factors (genes), or is it influenced by the environment (school, family, relationships, peers, community, culture)?

The polarized position of developmental psychologists of the past has now changed. The nature/nurture question now concerns the relationship between the innateness of an attribute and the environmental effects on that attribute (Nesterak, 2015).

The field of epigenetics describes how behavioral and environmental influences affect the expression of genes (Kubota, Miyake, & Hirasawa, 2012).

Many severe mental health disorders have a hereditary component. Yet, the environment and behavior, such as improved diet, reduced stress, physical activity, and a positive mindset, can determine whether this health condition is ever expressed (Śmigielski, Jagannath, Rössler, Walitza, & Grünblatt, 2020).

When considering classic models of developmental psychology, such as Piaget’s schema theory and Freud’s psychosexual theory, you’ll see that they both perceive development to be set in stone and unchangeable by the environment.

Contemporary developmental psychology theories take a different approach. They stress the importance of multiple levels of organization over the course of human development (Lomas, Hefferon, & Ivtzan, 2016).

2. Theory of mind

Theory of mind allows us to understand that others have different intentions, beliefs, desires, perceptions, behaviors, and emotions (American Psychological Association, 2020).

It was first identified by research by Premack and Woodruff (1978) and considered to be a natural developmental stage of progression for all children. Starting around the ages of four or five, children begin to think about the thoughts and feelings of others. This shows an emergence of the theory of mind (Wellman & Liu, 2004).

However, the ability of all individuals to achieve and maintain this critical skill at the same level is debatable.

Children diagnosed with autism exhibit a deficit in the theory of mind (Baron-Cohen, Leslie, & Frith, 1985).

Individuals with depression (psychotic and non-psychotic) are significantly impaired in theory of mind tasks (Wang, Wang, Chen, Zhu, & Wang, 2008).

People with social anxiety disorder have also been found to show less accuracy in decoding the mental states of others (Washburn, Wilson, Roes, Rnic, & Harkness, 2016).

Further research has shown that the theory of mind changes with aging. This suggests a developmental lifespan process for this concept (Meinhardt-Injac, Daum, & Meinhardt, 2020).

1. Little Albert

The small child who was the focus of the experiments of behavioral psychologists Watson and Rayner (1920) was referred to as ‘Little Albert.’ These experiments were essential landmarks in developmental psychology and showed how an emotionally stable child can be conditioned to develop a phobia.

Albert was exposed to several neutral stimuli including cotton wool, masks, a white rat, rabbit, monkey, and dog. Albert showed no initial fear to these stimuli.

When a loud noise was coupled with the initially neutral stimulus, Albert became very distressed and developed a phobia of the object, which extended to any similar object as well.

This experiment highlights the importance of environmental factors in the development of behaviors in children.

2. David Reimer

At the age of eight months, David Reimer lost his penis in a circumcision operation that went wrong. His worried parents consulted a psychologist, who advised them to raise David as a girl.

David’s young age meant he knew nothing about this. He went through the process of hormonal treatment and gender reassignment. At the age of 14, David found out the truth and wanted to reverse the gender reassignment process to become a boy again. He had always felt like a boy until this time, even though he was socialized and brought up as a girl (Colapinto, 2006).

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Contemporary theories of developmental psychology often encompass a holistic approach and a more positive approach to development.

Positive psychology has intersected with developmental disciplines in areas such as parenting, education, youth, and aging (Lomas et al., 2016).

These paradigms can all be grouped together under the umbrella of positive developmental psychology. This fresh approach to development focuses on the wellbeing aspects of development, while systematically bringing them together (Lomas, et al., 2016).

- Positive parenting is the approach to children’s wellbeing by focusing on the role of parents and caregivers (Latham, 1994).

- Positive education looks at flourishing in the context of school (Seligman, Ernst, Gillham, Reivich, & Linkins, 2009).

- Positive youth development is the productive and constructive focus on adolescence and early adulthood to enhance young people’s strengths and promote positive outcomes (Larson, 2000).

- Positive aging , also known as healthy aging, focuses on the positivity of aging as a healthy, normal stage of life (Vaillant, 2004).

Much of the empirical and theoretical work connected to positive developmental psychology has been going on for years, even before the emergence of positive psychology itself (Lomas et al., 2016).

We recommend this related article Applying Positive Psychology in Schools & Education: Your Ultimate Guide for further reading.

In the classroom, developmental psychology considers children’s psychological, emotional, and intellectual characteristics according to their developmental stage.

A report on the top 20 principles of psychology in the classroom, from pre-kindergarten to high school, was published by the American Psychological Association in 2015. The report also advised how teachers can respond to these principles in the classroom setting.

The top 5 principles and teacher responses are outlined in the table below.

There are many valuable resources to help you foster positive development no matter whether you’re working with young children, teenagers, or adults.

To help get you started, check out the following free resources from around our blog.

- Adopt A Growth Mindset This exercise helps clients recognize instances of fixed mindset in their thinking and actions and replace them with thoughts and behaviors more supportive of a growth mindset.

- Childhood Frustrations This worksheet provides a space for clients to document key challenges experienced during childhood, together with their emotional and behavioral responses.

- What I Want to Be This worksheet helps children identify behaviors and emotions they would like to display and select an opportunity in the future to behave in this ideal way.

- 17 Positive Psychology Exercises If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others enhance their wellbeing, this signature collection contains 17 validated positive psychology tools for practitioners. Use them to help others flourish and thrive.

- Developmental Psychology Courses If you are interested in a career in Developmental Psychology , we suggest 15 of the best courses in this article.

17 Top-Rated Positive Psychology Exercises for Practitioners

Expand your arsenal and impact with these 17 Positive Psychology Exercises [PDF] , scientifically designed to promote human flourishing, meaning, and wellbeing.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Earlier developmental psychology models and theories were focused on specific areas, such as attachment, psychosexual, cognitive, and social learning. Although informative, they did not take in differing perspectives and were fixed paradigms.

We’ve now come to understand that development is not fixed. Individual differences take place in development, and the factors that can affect development are many. It is ever changing throughout life.

The modern-day approach to developmental psychology includes sub-fields of positive psychology. It brings these differing disciplines together to form an overarching positive developmental psychology paradigm.

Developmental psychology has helped us gain a considerable understanding of children’s motivations, social and emotional contexts, and their strengths and weaknesses.

This knowledge is essential for educators to create rich learning environments for students to help them develop positively and ultimately flourish to their full potential.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Bell, S. M. (1970). Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development , 41 , 49–67.

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation . Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- American Psychological Association. (2015). Top 20 principles from psychology for PREK-12 teaching and learning: Coalition for psychology in schools and education . Retrieved July 16, 2021, from https://www.apa.org/ed/schools/teaching-learning/top-twenty-principles.pdf

- American Psychological Association. (2020). Developmental psychology. Dictionary of Psychology . Retrieved July 20, 2021, from https://dictionary.apa.org/

- Baltes, P. B., Lindenberger, U., & Staudinger, U. M. (2007). Life span theory in developmental psychology. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (pp. 569–564). Elsevier.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory . Prentice Hall.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory . Prentice-Hall.

- Bandura, A. Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1961). Transmission of aggression through the imitation of aggressive models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology , 63 , 575–582.

- Baron-Cohen, S., Leslie, A. M., & Frith, U. (1985). Does the autistic child have a ‘theory of mind’? Cognition , 21 (1), 37–46.

- Berger, K. S. (2014). The developing person through the lifespan (9th ed.). Worth.

- Bowlby, J. (1958). The nature of the child’s tie to his mother. International Journal of Psychoanalysis , 39 , 350–371.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Volume 1: Attachment . Hogarth Press.

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Volume 2: Anger and anxiety . Hogarth Press.

- Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Volume 3: Loss, sadness and depression . Hogarth Press.

- Brandon, A. R., Pitts, S., Wayne, H., Denton, C., Stringer, A., & Evans, H. M. (2009). A history of the theory of prenatal attachment. Journal of Prenatal and Perinatal Psychological Health , 23 (4), 201–222.

- Breuer, J., & Freud, S. (1957). Studies on hysteria . Basic Books.

- Burman, E. (2017). Deconstructing developmental psychology . Routledge.

- Colapinto, J. (2006). As nature made him: The boy who was raised as a girl . Harper Perennial.

- Darwin, C. (1877). A biographical sketch of an infant. Mind, 2 , 285–294.

- Erikson, E. (1959). Psychological issues . International Universities Press.

- Fisher, S., & Greenberg, R. P. (1996). Freud scientifically reappraised: Testing the theories and therapy . John Wiley & Sons.

- Freud, S. (1961). The ego and the id. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (pp. 3–66). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1923).

- Hall, G. S. (1883). The contents of children’s minds. The Princeton Review , 1 , 249–272.

- Harris, J. R. (1998). The nurture assumption: Why children turn out the way they do . Free Press.

- Kevin, D. (1995). Developmental social psychology: From infancy to old age . Wiley-Blackwell.

- Kubota, T., Miyake, K., & Hirasawa, T. (2012). Epigenetic understanding of gene-environment interactions in psychiatric disorders: A new concept of clinical genetics. Clinical Epigenetics , 4 (1), 1–8.

- Larson, R. W. (2000). Toward a psychology of positive youth development. American Psychologist , 55 (1), 170–183.

- Latham, G. I. (1994). The power of positive parenting . P&T Ink.

- Levitt, M. (2013). Perceptions of nature, nurture and behaviour. Life Sciences Society and Policy , 9 (1), 1–13.

- Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Ivtzan, I. (2016). Positive developmental psychology: A review of literature concerning well-being throughout the lifespan. The Journal of Happiness & Well-Being , 4 (2), 143–164.

- Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1986). Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In T. B. Brazelton & M. W. Yogman (Eds.), Affective development in infancy . Ablex.

- Meinhardt-Injac, B., Daum, M. M., & Meinhardt, G. (2020). Theory of mind development from adolescence to adulthood: Testing the two-component model. British Journal of Developmental Psychology , 38 , 289–303.

- Nesterak, E. (2015, July 10). The end of nature versus nature. Behavioral Scientist. Retrieved July 19, 2021 from https://behavioralscientist.org/the-end-of-nature-versus-nurture/

- Papalia, D. E., & Feldman, R. D. (2011). A child’s world: Infancy through adolescence . McGraw-Hill.

- Piaget, J. (1928). La causalité chez l’enfant. British Journal of Psychology , 18 (3), 276–301.

- Piaget, J. (1936). Origins of intelligence in the child . Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Piaget, J. (1951). Play, dreams and imitation in Childhood (vol. 25). Routledge.

- Premack, D., & Woodruff, G. (1978). Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behavioral and Brain Sciences , 1 (4), 515–526.

- Preyer, W. T. (1888). The mind of the child: Observations concerning the mental development of the human being in the first years of life (vol. 7). D. Appleton.

- Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Review of Education , 35 (3), 293–311.

- Silverman, D. K. (2017). Psychosexual stages of development (Freud). In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences . Springer.

- Simatwa, E. M. W. (2010). Piaget’s theory of intellectual development and its implications for instructional management at pre-secondary school level. Educational Research Review 5 , 366–371.

- Śmigielski, L., Jagannath, V., Rössler, W., Walitza, S., & Grünblatt, E. (2020). Epigenetic mechanisms in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders: A systematic review of empirical human findings. Molecular Psychiatr y, 25 (8), 1718–1748.

- Thompson, D. (2016). Developmental psychology in the 1920s: A period of major transition. The Journal of Genetic Psychology , 177 (6), 244–251.

- Vaillant, G. (2004). Positive aging. In P. A. Linley & S. Joseph (Eds.), Positive psychology in practice (pp. 561–580). John Wiley & Sons.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes . Harvard University Press.

- Wadsworth, B. J. (1971). Piaget’s theory of cognitive development: An introduction for students of psychology and education . McKay.

- Wang, Y. G., Wang, Y. Q., Chen, S. L., Zhu, C. Y., & Wang, K. (2008). Theory of mind disability in major depression with or without psychotic symptoms: a componential view. Psychiatry Research , 161 (2), 153–161.

- Washburn, D., Wilson, G., Roes, M., Rnic, K., & Harkness, K. L. (2016). Theory of mind in social anxiety disorder, depression, and comorbid conditions. Journal of Anxiety Disorders , 37 , 71–77.

- Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology , 3 (1), 1–14.

- Wellman, H. M., & Liu, D. (2004). Scaling theory of mind tasks. Child Development , 75 , 759–763.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

This article has enticed me to delve deeper into the subject of Positive Psychology. As a primary school teacher, I believe that positive psychology is a field that is imperative to explore. Take my gratitude from the core of my heart for your excellent work.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Hierarchy of Needs: A 2024 Take on Maslow’s Findings

One of the most influential theories in human psychology that addresses our quest for wellbeing is Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. While Maslow’s theory of [...]

Emotional Development in Childhood: 3 Theories Explained

We have all witnessed a sweet smile from a baby. That cute little gummy grin that makes us smile in return. Are babies born with [...]

Using Classical Conditioning for Treating Phobias & Disorders

Does the name Pavlov ring a bell? Classical conditioning, a psychological phenomenon first discovered by Ivan Pavlov in the late 19th century, has proven to [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Positive Psychology Tools (PDF)

Research in Developmental Psychology

What you’ll learn to do: examine how to do research in lifespan development.

How do we know what changes and stays the same (and when and why) in lifespan development? We rely on research that utilizes the scientific method so that we can have confidence in the findings. How data are collected may vary by age group and by the type of information sought. The developmental design (for example, following individuals as they age over time or comparing individuals of different ages at one point in time) will affect the data and the conclusions that can be drawn from them about actual age changes. What do you think are the particular challenges or issues in conducting developmental research, such as with infants and children? Read on to learn more.

Learning outcomes

- Explain how the scientific method is used in researching development

- Compare various types and objectives of developmental research

- Describe methods for collecting research data (including observation, survey, case study, content analysis, and secondary content analysis)

- Explain correlational research

- Describe the value of experimental research

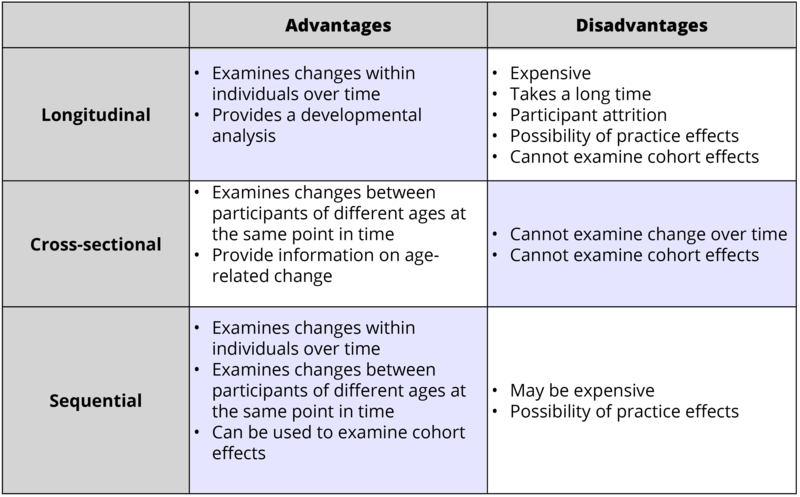

- Compare the advantages and disadvantages of developmental research designs (cross-sectional, longitudinal, and sequential)

- Describe challenges associated with conducting research in lifespan development

Research in Lifespan Development

How do we know what we know.

An important part of learning any science is having a basic knowledge of the techniques used in gathering information. The hallmark of scientific investigation is that of following a set of procedures designed to keep questioning or skepticism alive while describing, explaining, or testing any phenomenon. Not long ago a friend said to me that he did not trust academicians or researchers because they always seem to change their story. That, however, is exactly what science is all about; it involves continuously renewing our understanding of the subjects in question and an ongoing investigation of how and why events occur. Science is a vehicle for going on a never-ending journey. In the area of development, we have seen changes in recommendations for nutrition, in explanations of psychological states as people age, and in parenting advice. So think of learning about human development as a lifelong endeavor.

Personal Knowledge

How do we know what we know? Take a moment to write down two things that you know about childhood. Okay. Now, how do you know? Chances are you know these things based on your own history (experiential reality), what others have told you, or cultural ideas (agreement reality) (Seccombe and Warner, 2004). There are several problems with personal inquiry or drawing conclusions based on our personal experiences.

Our assumptions very often guide our perceptions, consequently, when we believe something, we tend to see it even if it is not there. Have you heard the saying, “seeing is believing”? Well, the truth is just the opposite: believing is seeing. This problem may just be a result of cognitive ‘blinders’ or it may be part of a more conscious attempt to support our own views. Confirmation bias is the tendency to look for evidence that we are right and in so doing, we ignore contradictory evidence.

Philosopher Karl Popper suggested that the distinction between that which is scientific and that which is unscientific is that science is falsifiable; scientific inquiry involves attempts to reject or refute a theory or set of assumptions (Thornton, 2005). A theory that cannot be falsified is not scientific. And much of what we do in personal inquiry involves drawing conclusions based on what we have personally experienced or validating our own experience by discussing what we think is true with others who share the same views.

Science offers a more systematic way to make comparisons and guard against bias. One technique used to avoid sampling bias is to select participants for a study in a random way. This means using a technique to ensure that all members have an equal chance of being selected. Simple random sampling may involve using a set of random numbers as a guide in determining who is to be selected. For example, if we have a list of 400 people and wish to randomly select a smaller group or sample to be studied, we use a list of random numbers and select the case that corresponds with that number (Case 39, 3, 217, etc.). This is preferable to asking only those individuals with whom we are familiar to participate in a study; if we conveniently chose only people we know, we know nothing about those who had no opportunity to be selected. There are many more elaborate techniques that can be used to obtain samples that represent the composition of the population we are studying. But even though a randomly selected representative sample is preferable, it is not always used because of costs and other limitations. As a consumer of research, however, you should know how the sample was obtained and keep this in mind when interpreting results. It is possible that what was found was limited to that sample or similar individuals and not generalizable to everyone else.

Scientific Methods

The particular method used to conduct research may vary by discipline and since lifespan development is multidisciplinary, more than one method may be used to study human development. One method of scientific investigation involves the following steps:

- Determining a research question

- Reviewing previous studies addressing the topic in question (known as a literature review)

- Determining a method of gathering information

- Conducting the study

- Interpreting the results

- Drawing conclusions; stating limitations of the study and suggestions for future research

- Making the findings available to others (both to share information and to have the work scrutinized by others)

The findings of these scientific studies can then be used by others as they explore the area of interest. Through this process, a literature or knowledge base is established. This model of scientific investigation presents research as a linear process guided by a specific research question. And it typically involves quantitative research , which relies on numerical data or using statistics to understand and report what has been studied.

Another model of research, referred to as qualitative research, may involve steps such as these:

- Begin with a broad area of interest and a research question

- Gain entrance into a group to be researched

- Gather field notes about the setting, the people, the structure, the activities, or other areas of interest

- Ask open-ended, broad “grand tour” types of questions when interviewing subjects

- Modify research questions as the study continues

- Note patterns or consistencies

- Explore new areas deemed important by the people being observed

- Report findings

In this type of research, theoretical ideas are “grounded” in the experiences of the participants. The researcher is the student and the people in the setting are the teachers as they inform the researcher of their world (Glazer & Strauss, 1967). Researchers should be aware of their own biases and assumptions, acknowledge them, and bracket them in efforts to keep them from limiting accuracy in reporting. Sometimes qualitative studies are used initially to explore a topic and more quantitative studies are used to test or explain what was first described.

A good way to become more familiar with these scientific research methods, both quantitative and qualitative, is to look at journal articles, which are written in sections that follow these steps in the scientific process. Most psychological articles and many papers in the social sciences follow the writing guidelines and format dictated by the American Psychological Association (APA). In general, the structure follows: abstract (summary of the article), introduction or literature review, methods explaining how the study was conducted, results of the study, discussion and interpretation of findings, and references.

Link to Learning

Brené Brown is a bestselling author and social work professor at the University of Houston. She conducts grounded theory research by collecting qualitative data from large numbers of participants. In Brené Brown’s TED Talk The Power of Vulnerability , Brown refers to herself as a storyteller-researcher as she explains her research process and summarizes her results.

Research Methods and Objectives

The main categories of psychological research are descriptive, correlational, and experimental research. Research studies that do not test specific relationships between variables are called descriptive, or qualitative, studies . These studies are used to describe general or specific behaviors and attributes that are observed and measured. In the early stages of research, it might be difficult to form a hypothesis, especially when there is not any existing literature in the area. In these situations designing an experiment would be premature, as the question of interest is not yet clearly defined as a hypothesis. Often a researcher will begin with a non-experimental approach, such as a descriptive study, to gather more information about the topic before designing an experiment or correlational study to address a specific hypothesis. Some examples of descriptive questions include:

- “How much time do parents spend with their children?”

- “How many times per week do couples have intercourse?”

- “When is marital satisfaction greatest?”

The main types of descriptive studies include observation, case studies, surveys, and content analysis (which we’ll examine further in the module). Descriptive research is distinct from correlational research , in which psychologists formally test whether a relationship exists between two or more variables. Experimental research goes a step further beyond descriptive and correlational research and randomly assigns people to different conditions, using hypothesis testing to make inferences about how these conditions affect behavior. Some experimental research includes explanatory studies, which are efforts to answer the question “why” such as:

- “Why have rates of divorce leveled off?”

- “Why are teen pregnancy rates down?”

- “Why has the average life expectancy increased?”

Evaluation research is designed to assess the effectiveness of policies or programs. For instance, research might be designed to study the effectiveness of safety programs implemented in schools for installing car seats or fitting bicycle helmets. Do children who have been exposed to the safety programs wear their helmets? Do parents use car seats properly? If not, why not?

Research Methods

We have just learned about some of the various models and objectives of research in lifespan development. Now we’ll dig deeper to understand the methods and techniques used to describe, explain, or evaluate behavior.

All types of research methods have unique strengths and weaknesses, and each method may only be appropriate for certain types of research questions. For example, studies that rely primarily on observation produce incredible amounts of information, but the ability to apply this information to the larger population is somewhat limited because of small sample sizes. Survey research, on the other hand, allows researchers to easily collect data from relatively large samples. While this allows for results to be generalized to the larger population more easily, the information that can be collected on any given survey is somewhat limited and subject to problems associated with any type of self-reported data. Some researchers conduct archival research by using existing records. While this can be a fairly inexpensive way to collect data that can provide insight into a number of research questions, researchers using this approach have no control over how or what kind of data was collected.

Types of Descriptive Research

Observation.

Observational studies , also called naturalistic observation, involve watching and recording the actions of participants. This may take place in the natural setting, such as observing children at play in a park, or behind a one-way glass while children are at play in a laboratory playroom. The researcher may follow a checklist and record the frequency and duration of events (perhaps how many conflicts occur among 2-year-olds) or may observe and record as much as possible about an event as a participant (such as attending an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting and recording the slogans on the walls, the structure of the meeting, the expressions commonly used, etc.). The researcher may be a participant or a non-participant. What would be the strengths of being a participant? What would be the weaknesses?

In general, observational studies have the strength of allowing the researcher to see how people behave rather than relying on self-report. One weakness of self-report studies is that what people do and what they say they do are often very different. A major weakness of observational studies is that they do not allow the researcher to explain causal relationships. Yet, observational studies are useful and widely used when studying children. It is important to remember that most people tend to change their behavior when they know they are being watched (known as the Hawthorne effect ) and children may not survey well.

Case Studies

Case studies involve exploring a single case or situation in great detail. Information may be gathered with the use of observation, interviews, testing, or other methods to uncover as much as possible about a person or situation. Case studies are helpful when investigating unusual situations such as brain trauma or children reared in isolation. And they are often used by clinicians who conduct case studies as part of their normal practice when gathering information about a client or patient coming in for treatment. Case studies can be used to explore areas about which little is known and can provide rich detail about situations or conditions. However, the findings from case studies cannot be generalized or applied to larger populations; this is because cases are not randomly selected and no control group is used for comparison. (Read The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat by Dr. Oliver Sacks as a good example of the case study approach.)

Surveys are familiar to most people because they are so widely used. Surveys enhance accessibility to subjects because they can be conducted in person, over the phone, through the mail, or online. A survey involves asking a standard set of questions to a group of subjects. In a highly structured survey, subjects are forced to choose from a response set such as “strongly disagree, disagree, undecided, agree, strongly agree”; or “0, 1-5, 6-10, etc.” Surveys are commonly used by sociologists, marketing researchers, political scientists, therapists, and others to gather information on many variables in a relatively short period of time. Surveys typically yield surface information on a wide variety of factors, but may not allow for an in-depth understanding of human behavior.

Surveys are useful in examining stated values, attitudes, opinions, and reporting on practices. However, they are based on self-report, or what people say they do rather than on observation, and this can limit accuracy. Validity refers to accuracy and reliability refers to consistency in responses to tests and other measures; great care is taken to ensure the validity and reliability of surveys.

Content Analysis

Content analysis involves looking at media such as old texts, pictures, commercials, lyrics, or other materials to explore patterns or themes in culture. An example of content analysis is the classic history of childhood by Aries (1962) called “Centuries of Childhood” or the analysis of television commercials for sexual or violent content or for ageism. Passages in text or television programs can be randomly selected for analysis as well. Again, one advantage of analyzing work such as this is that the researcher does not have to go through the time and expense of finding respondents, but the researcher cannot know how accurately the media reflects the actions and sentiments of the population.

Secondary content analysis, or archival research, involves analyzing information that has already been collected or examining documents or media to uncover attitudes, practices, or preferences. There are a number of data sets available to those who wish to conduct this type of research. The researcher conducting secondary analysis does not have to recruit subjects but does need to know the quality of the information collected in the original study. And unfortunately, the researcher is limited to the questions asked and data collected originally.

Correlational and Experimental Research

Correlational research.

When scientists passively observe and measure phenomena it is called correlational research . Here, researchers do not intervene and change behavior, as they do in experiments. In correlational research, the goal is to identify patterns of relationships, but not cause and effect. Importantly, with correlational research, you can examine only two variables at a time, no more and no less.

So, what if you wanted to test whether spending money on others is related to happiness, but you don’t have $20 to give to each participant in order to have them spend it for your experiment? You could use a correlational design—which is exactly what Professor Elizabeth Dunn (2008) at the University of British Columbia did when she conducted research on spending and happiness. She asked people how much of their income they spent on others or donated to charity, and later she asked them how happy they were. Do you think these two variables were related? Yes, they were! The more money people reported spending on others, the happier they were.

Understanding Correlation

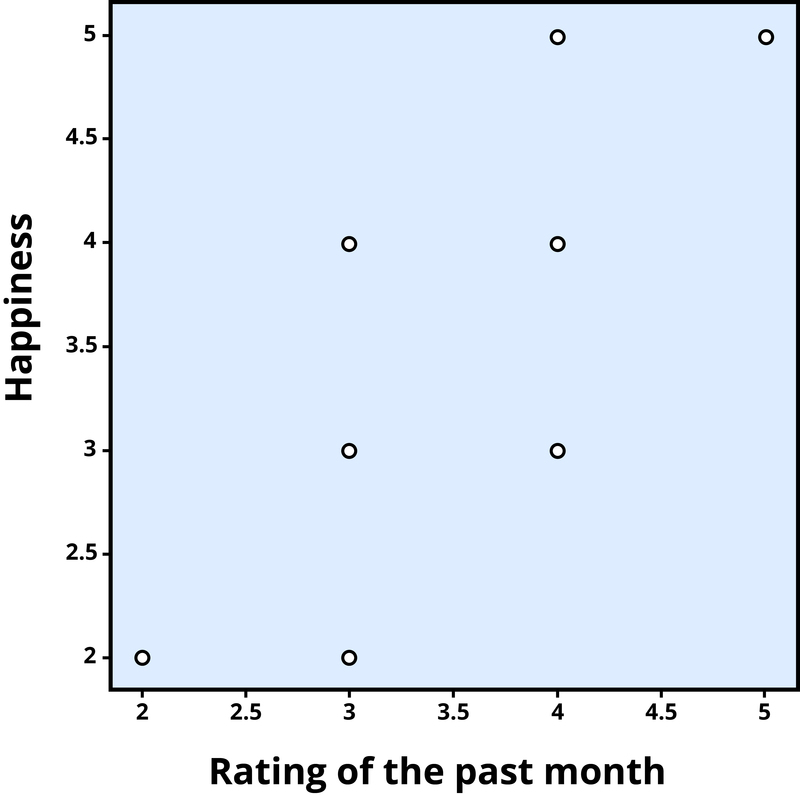

With a positive correlation , the two variables go up or down together. In a scatterplot, the dots form a pattern that extends from the bottom left to the upper right (just as they do in Figure 1). The r value for a positive correlation is indicated by a positive number (although, the positive sign is usually omitted). Here, the r value is .81. For the example above, the direction of the association is positive. This means that people who perceived the past month as being good reported feeling happier, whereas people who perceived the month as being bad reported feeling less happy.

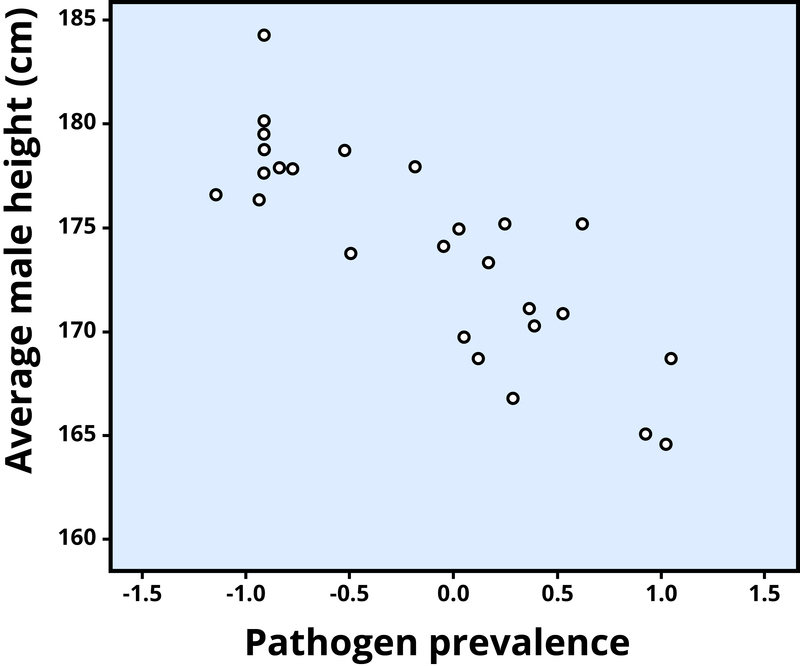

A negative correlation is one in which the two variables move in opposite directions. That is, as one variable goes up, the other goes down. Figure 2 shows the association between the average height of males in a country (y-axis) and the pathogen prevalence (or commonness of disease; x-axis) of that country. In this scatterplot, each dot represents a country. Notice how the dots extend from the top left to the bottom right. What does this mean in real-world terms? It means that people are shorter in parts of the world where there is more disease. The r-value for a negative correlation is indicated by a negative number—that is, it has a minus (–) sign in front of it. Here, it is –.83.

Experimental Research

Experiments are designed to test hypotheses (or specific statements about the relationship between variables ) in a controlled setting in an effort to explain how certain factors or events produce outcomes. A variable is anything that changes in value. Concepts are operationalized or transformed into variables in research which means that the researcher must specify exactly what is going to be measured in the study. For example, if we are interested in studying marital satisfaction, we have to specify what marital satisfaction really means or what we are going to use as an indicator of marital satisfaction. What is something measurable that would indicate some level of marital satisfaction? Would it be the amount of time couples spend together each day? Or eye contact during a discussion about money? Or maybe a subject’s score on a marital satisfaction scale? Each of these is measurable but these may not be equally valid or accurate indicators of marital satisfaction. What do you think? These are the kinds of considerations researchers must make when working through the design.

The experimental method is the only research method that can measure cause and effect relationships between variables. Three conditions must be met in order to establish cause and effect. Experimental designs are useful in meeting these conditions:

- The independent and dependent variables must be related. In other words, when one is altered, the other changes in response. The independent variable is something altered or introduced by the researcher; sometimes thought of as the treatment or intervention. The dependent variable is the outcome or the factor affected by the introduction of the independent variable; the dependent variable depends on the independent variable. For example, if we are looking at the impact of exercise on stress levels, the independent variable would be exercise; the dependent variable would be stress.

- The cause must come before the effect. Experiments measure subjects on the dependent variable before exposing them to the independent variable (establishing a baseline). So we would measure the subjects’ level of stress before introducing exercise and then again after the exercise to see if there has been a change in stress levels. (Observational and survey research does not always allow us to look at the timing of these events which makes understanding causality problematic with these methods.)

- The cause must be isolated. The researcher must ensure that no outside, perhaps unknown variables, are actually causing the effect we see. The experimental design helps make this possible. In an experiment, we would make sure that our subjects’ diets were held constant throughout the exercise program. Otherwise, the diet might really be creating a change in stress level rather than exercise.

A basic experimental design involves beginning with a sample (or subset of a population) and randomly assigning subjects to one of two groups: the experimental group or the control group . Ideally, to prevent bias, the participants would be blind to their condition (not aware of which group they are in) and the researchers would also be blind to each participant’s condition (referred to as “ double blind “). The experimental group is the group that is going to be exposed to an independent variable or condition the researcher is introducing as a potential cause of an event. The control group is going to be used for comparison and is going to have the same experience as the experimental group but will not be exposed to the independent variable. This helps address the placebo effect, which is that a group may expect changes to happen just by participating. After exposing the experimental group to the independent variable, the two groups are measured again to see if a change has occurred. If so, we are in a better position to suggest that the independent variable caused the change in the dependent variable . The basic experimental model looks like this:

The major advantage of the experimental design is that of helping to establish cause and effect relationships. A disadvantage of this design is the difficulty of translating much of what concerns us about human behavior into a laboratory setting.

Developmental Research Designs

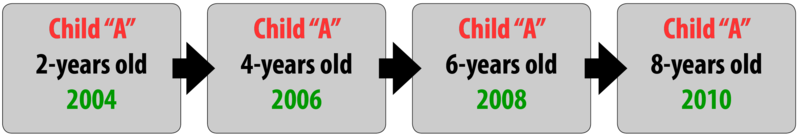

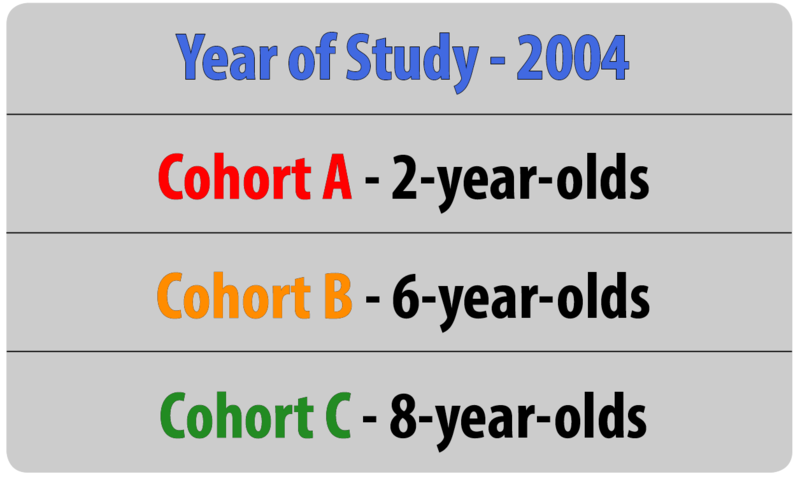

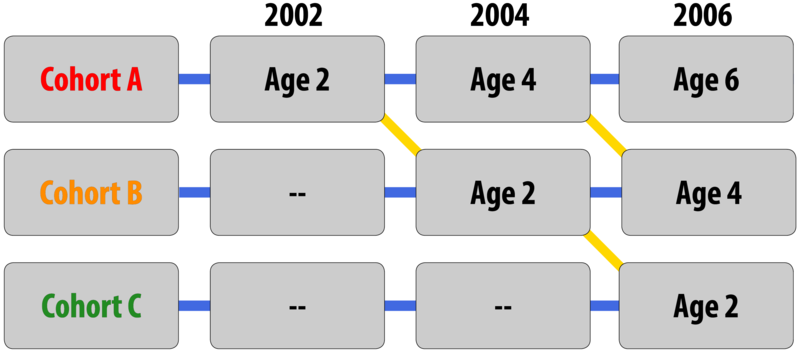

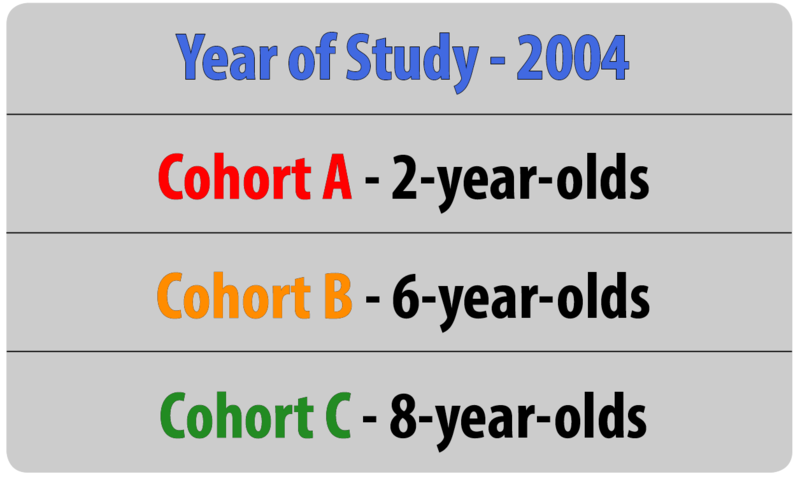

Now you know about some tools used to conduct research about human development. Remember, research methods are tools that are used to collect information. But it is easy to confuse research methods and research design. Research design is the strategy or blueprint for deciding how to collect and analyze information. Research design dictates which methods are used and how. Developmental research designs are techniques used particularly in lifespan development research. When we are trying to describe development and change, the research designs become especially important because we are interested in what changes and what stays the same with age. These techniques try to examine how age, cohort, gender, and social class impact development.

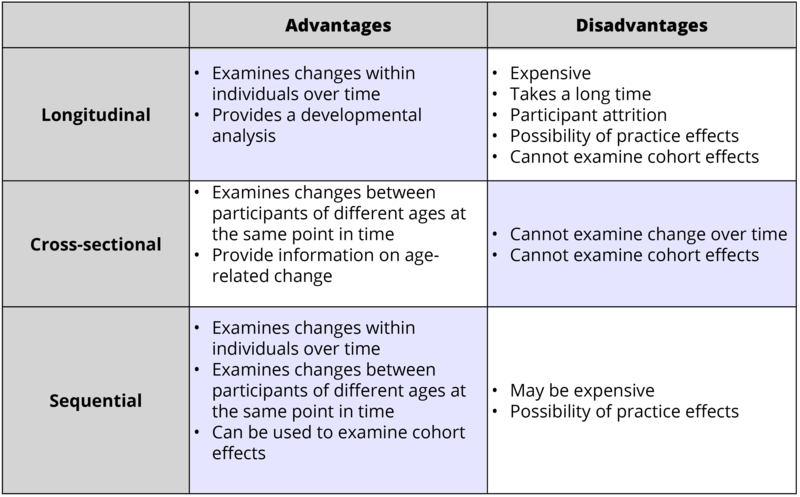

Cross-sectional designs

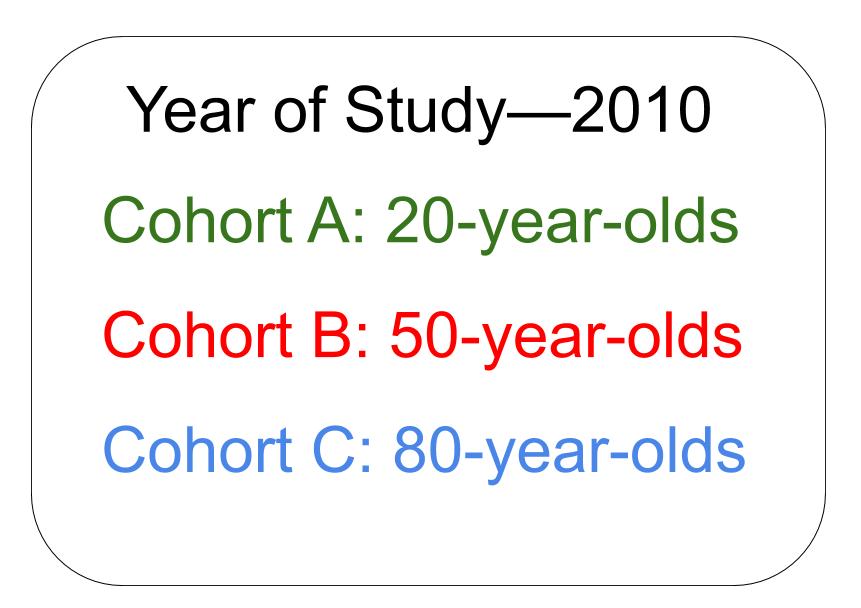

The majority of developmental studies use cross-sectional designs because they are less time-consuming and less expensive than other developmental designs. Cross-sectional research designs are used to examine behavior in participants of different ages who are tested at the same point in time. Let’s suppose that researchers are interested in the relationship between intelligence and aging. They might have a hypothesis (an educated guess, based on theory or observations) that intelligence declines as people get older. The researchers might choose to give a certain intelligence test to individuals who are 20 years old, individuals who are 50 years old, and individuals who are 80 years old at the same time and compare the data from each age group. This research is cross-sectional in design because the researchers plan to examine the intelligence scores of individuals of different ages within the same study at the same time; they are taking a “cross-section” of people at one point in time. Let’s say that the comparisons find that the 80-year-old adults score lower on the intelligence test than the 50-year-old adults, and the 50-year-old adults score lower on the intelligence test than the 20-year-old adults. Based on these data, the researchers might conclude that individuals become less intelligent as they get older. Would that be a valid (accurate) interpretation of the results?

No, that would not be a valid conclusion because the researchers did not follow individuals as they aged from 20 to 50 to 80 years old. One of the primary limitations of cross-sectional research is that the results yield information about age differences not necessarily changes with age or over time. That is, although the study described above can show that in 2010, the 80-year-olds scored lower on the intelligence test than the 50-year-olds, and the 50-year-olds scored lower on the intelligence test than the 20-year-olds, the data used to come up with this conclusion were collected from different individuals (or groups of individuals). It could be, for instance, that when these 20-year-olds get older (50 and eventually 80), they will still score just as high on the intelligence test as they did at age 20. In a similar way, maybe the 80-year-olds would have scored relatively low on the intelligence test even at ages 50 and 20; the researchers don’t know for certain because they did not follow the same individuals as they got older.

It is also possible that the differences found between the age groups are not due to age, per se, but due to cohort effects. The 80-year-olds in this 2010 research grew up during a particular time and experienced certain events as a group. They were born in 1930 and are part of the Traditional or Silent Generation. The 50-year-olds were born in 1960 and are members of the Baby Boomer cohort. The 20-year-olds were born in 1990 and are part of the Millennial or Gen Y Generation. What kinds of things did each of these cohorts experience that the others did not experience or at least not in the same ways?

You may have come up with many differences between these cohorts’ experiences, such as living through certain wars, political and social movements, economic conditions, advances in technology, changes in health and nutrition standards, etc. There may be particular cohort differences that could especially influence their performance on intelligence tests, such as education level and use of computers. That is, many of those born in 1930 probably did not complete high school; those born in 1960 may have high school degrees, on average, but the majority did not attain college degrees; the young adults are probably current college students. And this is not even considering additional factors such as gender, race, or socioeconomic status. The young adults are used to taking tests on computers, but the members of the other two cohorts did not grow up with computers and may not be as comfortable if the intelligence test is administered on computers. These factors could have been a factor in the research results.

Another disadvantage of cross-sectional research is that it is limited to one time of measurement. Data are collected at one point in time and it’s possible that something could have happened in that year in history that affected all of the participants, although possibly each cohort may have been affected differently. Just think about the mindsets of participants in research that was conducted in the United States right after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001.

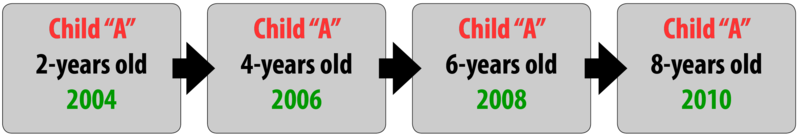

Longitudinal research designs

Longitudinal research involves beginning with a group of people who may be of the same age and background (cohort) and measuring them repeatedly over a long period of time. One of the benefits of this type of research is that people can be followed through time and be compared with themselves when they were younger; therefore changes with age over time are measured. What would be the advantages and disadvantages of longitudinal research? Problems with this type of research include being expensive, taking a long time, and subjects dropping out over time. Think about the film, 63 Up , part of the Up Series mentioned earlier, which is an example of following individuals over time. In the videos, filmed every seven years, you see how people change physically, emotionally, and socially through time; and some remain the same in certain ways, too. But many of the participants really disliked being part of the project and repeatedly threatened to quit; one disappeared for several years; another died before her 63rd year. Would you want to be interviewed every seven years? Would you want to have it made public for all to watch?

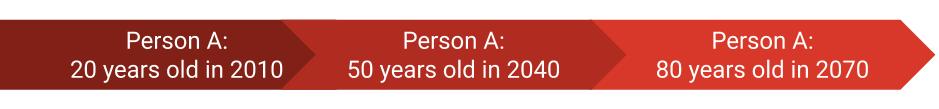

Longitudinal research designs are used to examine behavior in the same individuals over time. For instance, with our example of studying intelligence and aging, a researcher might conduct a longitudinal study to examine whether 20-year-olds become less intelligent with age over time. To this end, a researcher might give an intelligence test to individuals when they are 20 years old, again when they are 50 years old, and then again when they are 80 years old. This study is longitudinal in nature because the researcher plans to study the same individuals as they age. Based on these data, the pattern of intelligence and age might look different than from the cross-sectional research; it might be found that participants’ intelligence scores are higher at age 50 than at age 20 and then remain stable or decline a little by age 80. How can that be when cross-sectional research revealed declines in intelligence with age?

Since longitudinal research happens over a period of time (which could be short term, as in months, but is often longer, as in years), there is a risk of attrition. Attrition occurs when participants fail to complete all portions of a study. Participants may move, change their phone numbers, die, or simply become disinterested in participating over time. Researchers should account for the possibility of attrition by enrolling a larger sample into their study initially, as some participants will likely drop out over time. There is also something known as selective attrition— this means that certain groups of individuals may tend to drop out. It is often the least healthy, least educated, and lower socioeconomic participants who tend to drop out over time. That means that the remaining participants may no longer be representative of the whole population, as they are, in general, healthier, better educated, and have more money. This could be a factor in why our hypothetical research found a more optimistic picture of intelligence and aging as the years went by. What can researchers do about selective attrition? At each time of testing, they could randomly recruit more participants from the same cohort as the original members, to replace those who have dropped out.

The results from longitudinal studies may also be impacted by repeated assessments. Consider how well you would do on a math test if you were given the exact same exam every day for a week. Your performance would likely improve over time, not necessarily because you developed better math abilities, but because you were continuously practicing the same math problems. This phenomenon is known as a practice effect. Practice effects occur when participants become better at a task over time because they have done it again and again (not due to natural psychological development). So our participants may have become familiar with the intelligence test each time (and with the computerized testing administration). Another limitation of longitudinal research is that the data are limited to only one cohort.

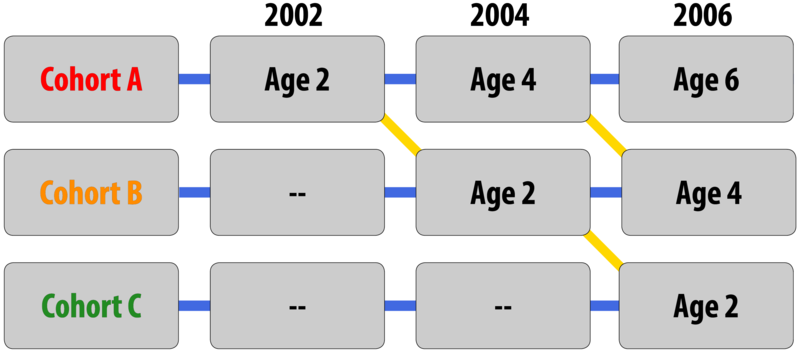

Sequential research designs

Sequential research designs include elements of both longitudinal and cross-sectional research designs. Similar to longitudinal designs, sequential research features participants who are followed over time; similar to cross-sectional designs, sequential research includes participants of different ages. This research design is also distinct from those that have been discussed previously in that individuals of different ages are enrolled into a study at various points in time to examine age-related changes, development within the same individuals as they age, and to account for the possibility of cohort and/or time of measurement effects. In 1965, K. Warner Schaie described particular sequential designs: cross-sequential, cohort sequential, and time-sequential. The differences between them depended on which variables were focused on for analyses of the data (data could be viewed in terms of multiple cross-sectional designs or multiple longitudinal designs or multiple cohort designs). Ideally, by comparing results from the different types of analyses, the effects of age, cohort, and time in history could be separated out.

Challenges Conducting Developmental Research

The previous sections describe research tools to assess development across the lifespan, as well as the ways that research designs can be used to track age-related changes and development over time. Before you begin conducting developmental research, however, you must also be aware that testing individuals of certain ages (such as infants and children) or making comparisons across ages (such as children compared to teens) comes with its own unique set of challenges. In the final section of this module, let’s look at some of the main issues that are encountered when conducting developmental research, namely ethical concerns, recruitment issues, and participant attrition.

Ethical Concerns

You may already know that Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) must review and approve all research projects that are conducted at universities, hospitals, and other institutions (each broad discipline or field, such as psychology or social work, often has its own code of ethics that must also be followed, regardless of institutional affiliation). An IRB is typically a panel of experts who read and evaluate proposals for research. IRB members want to ensure that the proposed research will be carried out ethically and that the potential benefits of the research outweigh the risks and potential harm (psychological as well as physical harm) for participants.

What you may not know though, is that the IRB considers some groups of participants to be more vulnerable or at-risk than others. Whereas university students are generally not viewed as vulnerable or at-risk, infants and young children commonly fall into this category. What makes infants and young children more vulnerable during research than young adults? One reason infants and young children are perceived as being at increased risk is due to their limited cognitive capabilities, which makes them unable to state their willingness to participate in research or tell researchers when they would like to drop out of a study. For these reasons, infants and young children require special accommodations as they participate in the research process. Similar issues and accommodations would apply to adults who are deemed to be of limited cognitive capabilities.

When thinking about special accommodations in developmental research, consider the informed consent process. If you have ever participated in scientific research, you may know through your own experience that adults commonly sign an informed consent statement (a contract stating that they agree to participate in research) after learning about a study. As part of this process, participants are informed of the procedures to be used in the research, along with any expected risks or benefits. Infants and young children cannot verbally indicate their willingness to participate, much less understand the balance of potential risks and benefits. As such, researchers are oftentimes required to obtain written informed consent from the parent or legal guardian of the child participant, an adult who is almost always present as the study is conducted. In fact, children are not asked to indicate whether they would like to be involved in a study at all (a process known as assent) until they are approximately seven years old. Because infants and young children cannot easily indicate if they would like to discontinue their participation in a study, researchers must be sensitive to changes in the state of the participant (determining whether a child is too tired or upset to continue) as well as to parent desires (in some cases, parents might want to discontinue their involvement in the research). As in adult studies, researchers must always strive to protect the rights and well-being of the minor participants and their parents when conducting developmental research.

Recruitment

An additional challenge in developmental science is participant recruitment. Recruiting university students to participate in adult studies is typically easy. Unfortunately, young children cannot be recruited in this way. Given these limitations, how do researchers go about finding infants and young children to be in their studies?

The answer to this question varies along multiple dimensions. Researchers must consider the number of participants they need and the financial resources available to them, among other things. Location may also be an important consideration. Researchers who need large numbers of infants and children may attempt to recruit them by obtaining infant birth records from the state, county, or province in which they reside. Researchers can choose to pay a recruitment agency to contact and recruit families for them. More economical recruitment options include posting advertisements and fliers in locations frequented by families, such as mommy-and-me classes, local malls, and preschools or daycare centers. Researchers can also utilize online social media outlets like Facebook, which allows users to post recruitment advertisements for a small fee. Of course, each of these different recruitment techniques requires IRB approval. And if children are recruited and/or tested in school settings, permission would need to be obtained ahead of time from teachers, schools, and school districts (as well as informed consent from parents or guardians).

And what about the recruitment of adults? While it is easy to recruit young college students to participate in research, some would argue that it is too easy and that college students are samples of convenience. They are not randomly selected from the wider population, and they may not represent all young adults in our society (this was particularly true in the past with certain cohorts, as college students tended to be mainly white males of high socioeconomic status). In fact, in the early research on aging, this type of convenience sample was compared with another type of convenience sample—young college students tended to be compared with residents of nursing homes! Fortunately, it didn’t take long for researchers to realize that older adults in nursing homes are not representative of the older population; they tend to be the oldest and sickest (physically and/or psychologically). Those initial studies probably painted an overly negative view of aging, as young adults in college were being compared to older adults who were not healthy, had not been in school nor taken tests in many decades, and probably did not graduate high school, let alone college. As we can see, recruitment and random sampling can be significant issues in research with adults, as well as infants and children. For instance, how and where would you recruit middle-aged adults to participate in your research?

Another important consideration when conducting research with infants and young children is attrition . Although attrition is quite common in longitudinal research in particular (see the previous section on longitudinal designs for an example of high attrition rates and selective attrition in lifespan developmental research), it is also problematic in developmental science more generally, as studies with infants and young children tend to have higher attrition rates than studies with adults. Infants and young children are more likely to tire easily, become fussy, and lose interest in the study procedures than are adults. For these reasons, research studies should be designed to be as short as possible – it is likely better to break up a large study into multiple short sessions rather than cram all of the tasks into one long visit to the lab. Researchers should also allow time for breaks in their study protocols so that infants can rest or have snacks as needed. Happy, comfortable participants provide the best data.

Conclusions