The Affective Filter Hypothesis: Definition and Criticism

January 23, 2018, 9:00 am

Linguist and educator Stephen Krashen proposed the Monitor Model, his theory of second language acquisition, in Principles and practice in second language acquisition as published in 1982. According to the Monitor Model, five hypotheses account for the acquisition of a second language:

- Acquisition-learning hypothesis

- Natural order hypothesis

- Monitor hypothesis

- Input hypothesis

- Affective filter hypothesis

However, in spite of the popularity and influence of the Monitor Model, the five hypotheses are not without criticism. The following sections offer a description of the fifth and final hypothesis of the theory, the affective filter hypothesis, as well as the major criticism by other linguistics and educators surrounding the hypothesis.

Definition of the Affective Filter Hypothesis

The fifth hypothesis, the affective filter hypothesis, accounts for the influence of affective factors on second language acquisition. Affect refers to non-linguistic variables such as motivation, self-confidence, and anxiety. According to the affective filter hypothesis, affect effects acquisition, but not learning, by facilitating or preventing comprehensible input from reaching the language acquisition device. In other words, affective variables such as fear, nervousness, boredom, and resistance to change can effect the acquisition of a second language by preventing information about the second language from reaching the language areas of the mind.

Furthermore, when the affective filter blocks comprehensible input, acquisition fails or occurs to a lesser extent then when the affective filter supports the intake of comprehensible input. The affective filter, therefore, accounts for individual variation in second language acquisition. Second language instruction can and should work to minimize the effects of the affective filter.

Criticism of the Affective Filter Hypothesis

The final critique of Krashen’s Monitor Model questions the claim of the affective filter hypothesis that affective factors alone account for individual variation in second language acquisition. First, Krashen claims that children lack the affective filter that causes most adult second language learners to never completely master their second language. Such a claim fails to withstand scrutiny because children also experience differences in non-linguistic variables such as motivation, self-confidence, and anxiety that supposedly account for child-adult differences in second language learning.

Furthermore, evidence in the form of adult second language learners who acquire a second language to a native-like competence except for a single grammatical feature problematizes the claim that an affective filter prevents comprehensible input from reaching the language acquisition device. As Manmay Zafar asks, “How does the filter determine which parts of language are to be screened in/out?” In other words, the affective filter hypothesis fails to answer the most important question about affect alone accounting for individual variation in second language acquisition.

Although the Monitor Model has been influential in the field of second language acquisition, the fifth and final hypothesis, the affective filter hypothesis, has not been without criticism as evidenced by the critiques offered by other linguists and educators in the field.

Gass, Susan M. & Larry Selinker. 2008. Second language acquisition: An introductory course , 3rd edn. New York: Routledge. Gregg, Kevin R. 1984. Krashen’s monitor and Occam’s razor. Applied Linguistics 5(2). 79-100. Krashen, Stephen D. 1982. Principles and practice in second language acquisition . Oxford: Pergamon. http://www.sdkrashen.com/Principles_and_Practice/Principles_and_Practice.pdf. Lightbrown, Patsy M. & Nina Spada. 2006. How languages are learned , 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Zafar, Manmay. 2009. Monitoring the ‘monitor’: A critique of Krashen’s five hypotheses. Dhaka University Journal of Linguistics 2(4). 139-146.

affective filter hypothesis language acquisition language learning monitor model

The Input Hypothesis: Definition and Criticism

The Postpositional Complement in English Grammar

Seidlitz Education

Developing Language in Every Classroom

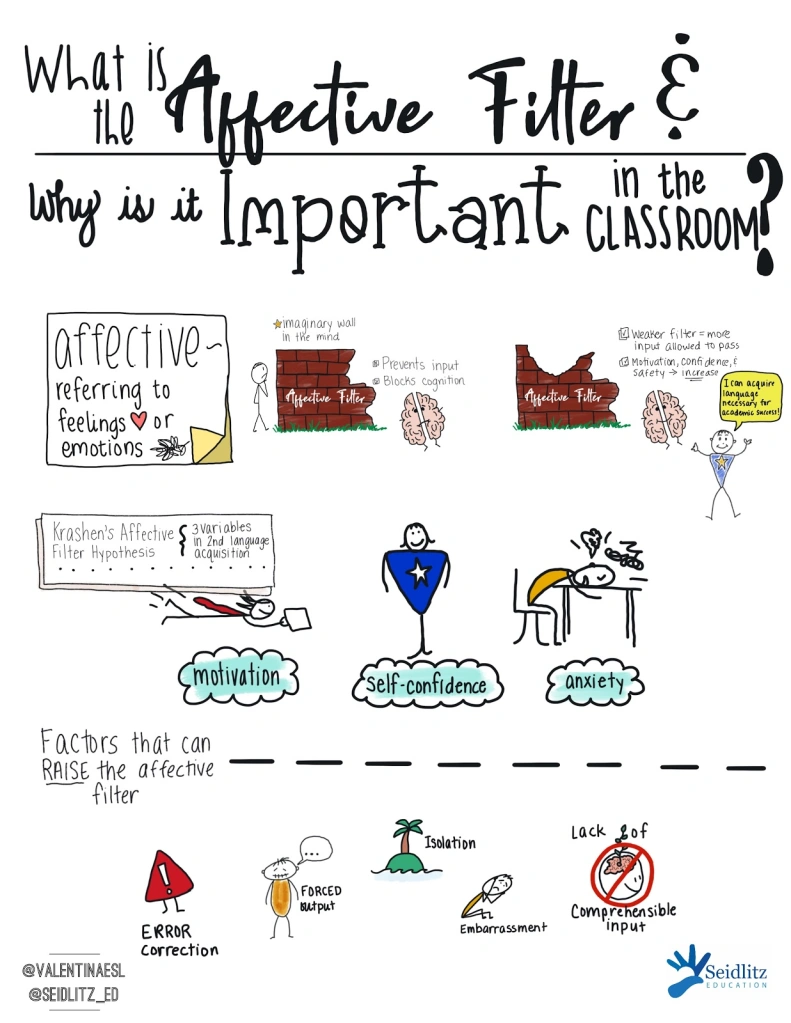

What Is the Affective Filter, and Why Is it Important in the Classroom?

by Valentina Gonzalez

What Is the Affective Filter?

The term “affective filter” originates from Stephen Krashen, an expert in the field of linguistics, who described it as a number of affective variables that contribute to second language acquisition. Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary defines affective as “referring to, arising from, or influencing feelings or emotions.”

Krashen (1986) cites motivation, self-confidence, and anxiety in the Affective Filter Hypothesis as three categories of variables that play a role in second language acquisition. In essence, when feelings or emotions such as anxiety, fear, or embarrassment are elevated, it becomes difficult for language acquisition to occur. The affective filter has commonly been described as an imaginary wall that rises in the mind and prevents input, thus blocking cognition. In opposition, when the affective filter is lowered, the feeling of safety is high, and language acquisition occurs. In fact, even current research in neuroscience seems to support Krashen’s theory that stress affects thinking and learning.

Why Is the Affective Filter Important in the Classroom?

It is not enough to simply teach. It is not enough to deliver instruction even if it’s made comprehensible to students. If students’ affective filters are elevated, language acquisition will be impeded. Creating classroom environments that act intentionally to lower the affective filter will increase language development.

The lower the filter, the more input is allowed to pass through. Students who are highly motivated, feel confident, and feel safe are more open to input.

Let’s picture two classrooms:

- In the first classroom, students walk in and sit in isolated rows. The teacher reads from a scripted lesson before assigning a worksheet for students to complete independently. Talk is discouraged, and students are quickly reprimanded for stepping outside of the planned lesson. It is clear to the students that their role is to comply with the teacher’s rules for the classroom.

- In the second classroom, students have a voice in instruction. They are part of their learning journey. This creates motivation to learn. They gather in groups to share ideas, and they are encouraged to take risks, which helps build their self-confidence. The classroom talk is balanced with some teacher talk and some student talk. Students feel comfortable sharing their ideas and opinions.

When you imagined these two classrooms, in which one did you feel that students had more room to bloom freely within the context of the content? The teacher in the second classroom had a way of lowering the affective filter for students. But how?

How Do We Lower the Affective Filter in the Classroom?

The answer is similar to how you might make visitors feel welcome at your home. Typically, if you want company to stay, you create a space that is inviting, comfortable, friendly, and interesting. You cater to their needs, offer them food, and pay attention to them. (And, I don’t know about you, but if I don’t want company to stay for long, I simply don’t do these things!)

We can lower the affective filters of our students in our classroom in similar ways to how we make visitors feel welcome in our homes. Let’s examine how this might look through the three categories that Krashen proposed: motivation, self-confidence, and anxiety.

Some might think motivation is solely up to individual students. But while educators don’t have complete control over student motivation, they can still influence it. Choice, voice, and relevance are three great motivators we can leverage in the classroom. Providing students with opportunities to select topics to study helps them feel motivated to do the work. Allowing students choice in what they write about or how they show understanding also builds motivation. Creating time and space for students to share their voice in learning stimulates a drive in learners. When students feel they have some say or some control over their learning journeys, they become more invested. Finally, providing learners with engaging experiences that tap into their passions increases motivation. When we keep instruction relevant to students’ lives, what they are learning becomes compelling to them.

Self-confidence

Learners who feel a sense of belonging, value, and respect for their individuality are more likely to have lower affective filters. Creating classrooms that warmly welcome all students builds self-confidence. On the other hand, when students feel isolated or that they must “fit in,” their self-confidence erodes. To build self-confidence, educators can work on correctly pronouncing students’ names, ensure that walls and books are representative of the student population, and get to know students for who they are beyond the classroom.

A safe classroom is one in which students are not afraid to make errors. Classrooms that embrace errors as part of the learning process are more likely to decrease students’ affective filters. Fostering a growth mindset and modeling this mindset with students can help them understand that mistakes are a part of growth in the process of learning. The way we talk with students and our body language can also affect their anxiety. Even students who are not yet speaking in English can understand body language and feel the energy in a classroom. Smiling sends a positive, warm message; sitting next to a student to confer with them rather than sitting in front of them is less confrontational; arms at the side rather than crossed is less aggressive. Another way to lower the affective filter is by making sure that we provide comprehensible input. Students become more focused and relaxed the more they can understand the language being used during instruction.

On the other hand, there are specific moves we make that can be counterproductive and raise the affective filter. The factors below can raise the affective filter and impede language acquisition:

- Error correction

- Forcing output too early

- Embarrassment

- Lack of comprehensible input

We may not even know that we are doing these things or that they are causing the imaginary wall to come up. But becoming aware of the affective filter, what raises it, and how to lower it can help language acquisition flourish.

Krashen, S. D. (1986). Principles and practice in second language acquisition . Oxford: Pergamon Press. http://www.sdkrashen.com/content/books/principles_and_practice.pdf

Share this:

Published by Seidlitz Education

View all posts by Seidlitz Education

14 thoughts on “ What Is the Affective Filter, and Why Is it Important in the Classroom? ”

- Pingback: The Best Resources, Articles & Blog Posts For Teachers Of ELLs In 2020 - NWS100

- Pingback: Building on the Foundations for Reading – Seidlitz Education

- Pingback: 7 Ideas for Review Games and Activities that Engage English Learners

- Pingback: Tad Lincoln's Restless Wriggle: Pandemonium and Patience in the President's House by Beth Anderson - Caroline Starr Rose

- Pingback: The Seidlitz Blog’s Top Posts from 2021 – Seidlitz Education

This really helps my writing on how we trainee teachers lower the affective filter in our classroom and thank you so much for providing it for us the ones who really need it for their study

- Pingback: A Welcoming Environment – The School Idealist

- Pingback: Bilinguismo: capire è più importante di parlare - Piccoli Camaleonti % %

- Pingback: Bilinguismo: capire è più importante di parlare Bilinguismo

- Pingback: Is Passive Listening Language Learning Possible? How to Learn with Music

- Pingback: Why Hexagonal Thinking is Perfect for Multilingual Learners - Maestra Novoa

- Pingback: SLA-Speak Series: Affective Filter - Eric Richards Instructional Consulting, LLC

- Pingback: Collaborating Across Departments to Serve Multilingual Learners – Seidlitz Education

- Pingback: QSSSA: The Secret Ingredient to Language-Rich, Interactive Classrooms – Seidlitz Education

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

The Affective Filter and Pronunciation Proficiency — Attitudes and Variables in Second Language Acquisition

Cite this chapter.

- Robert M. Hammond 2

323 Accesses

2 Citations

In developing his theory of second language acquisition, Krashen (1982) suggests five hypotheses: the acquisition-learning hypothesis; the natural order hypothesis; the input hypothesis; and the affective filter hypothesis. The first three of these hypotheses are central to the organization of a language program using the natural approach (Krashen and Terrell 1983); that is, they form the underlying bases for a program whose purpose it is to develop in beginning students as much communicative competency as possible in a beginning language course or series of courses. The latter two, the input and affective filter hypotheses, however, determine on a day-to-day basis what actually takes place in the second language classroom . In very general terms, the input hypothesis states that we must provide as much comprehensible input as possible for a student in the second language classroom, since within Krashen’s theoretical framework, it is claimed that it is through and only through comprehensible input becoming comprehended input that language is acquired (not learned). The notion of the affective filter, originally presented in Dulay and Burt (1977), which is much less controversial, and valid for almost all language teaching methodologies, states that the affective variables of motivation, self-confidence and anxiety (Krashen 1982) have a profound influence on language acquisition (not learning). The claim of the natural approach is that students will acquire second languages best when they are in an environment which provides a maximally low (weak) affective filter, and a maximally high amount of comprehensible input.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Bibliography

Dulay, H. and M. Burt. 1977. Remarks on creativity in language acquisition. M. Burt, H. Dulay and M. Finnochiaro (Eds.). Viewpoints on English as a second language. New York: Regents Press, pp. 95–126.

Google Scholar

Krashen S. 1982. Principles and practice in second language acquisition . New York: Pergamon Press.

Krashen, S. and T. Terrell. 1983. The natural approach . Hayward, CA: Alemany Press.

Levitan, A. 1980. Hispanics in Dade County: their characteristics and needs . Miami, FL: Office of the County Manager.

MacDonald, M. 1985. Cuban American English: the second generation in Miami . Ph.D. dissertation, Gainesville: University of Florida.

United States Bureau of the Census. 1982. General population characteristics, Florida. Washington, D.C.,: United States Government Printing Office.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Catholic University of America, Washington, DC, USA

Robert M. Hammond

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware, USA

Louis A. Arena

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 1990 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Hammond, R.M. (1990). The Affective Filter and Pronunciation Proficiency — Attitudes and Variables in Second Language Acquisition. In: Arena, L.A. (eds) Language Proficiency. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0870-4_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0870-4_6

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4899-0872-8

Online ISBN : 978-1-4899-0870-4

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Multilingual Pedagogy and World Englishes

Linguistic Variety, Global Society

Affective Filter

The affective filter is a concept put forward by Stephen Krashen describing the relationship between the processes of language acquisition and the emotional or psychological states of language learners (Krashen 423). Krashen argues that it is “more than coincidence” that anxiety-inducing classroom activities are often ineffective at promoting language acquisition, while activities putting students at ease are often more effective. Theoretically, a lower affective filter or lower-stress environment will promote an optimal language learning situation, while a raised affective filter can disrupt or undermine learning.

Application

Learning a language is usually stressful, but, as Linda Schinke-Llano and Robert Vicars there are many methods for countering the inevitable anxiety of the language classroom, including “Lozanov’s work on Suggestopedia, Curran’s on Counseling Learning/Community Language Learning, and Krashen and Terrell’s on the Natural Approach” (325).

Some might argue that the nature of education inevitably produces uncertainty, doubt, lack of motivation, and anxiety. At top-tier institutions, the pressure to compete and succeed can be enormous, and students–regardless of their linguistic or cultural backgrounds or preparation–feel the strain. Amid everything else, students in language classrooms feel additional stress unique to language learning. Schinke-Llano and Vicars argue, “It behooves all of us as second language educators to see to it that we provide classroom activities that are as facilitative as possible of negotiated interaction and that, in turn, allow our students to feel as comfortable as possible in their execution” (328). In other words, teachers would be well-advised to create and deploy classroom activities and strategies (see also above) that can help students lower or at least cope more effectively with emotional factors capable of impeding their learning.

Berg, Katherine. “Affective Filter.” YouTube, Uploaded by Katherine B., 22 Oct. 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aUzutTV_YVA.

Bibliography

Krashen, Stephen. “The Input Hypothesis: An Update.” Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics (GURT) 1991: Linguistics and Language Pedagogy: The State of the Art . Georgetown University Press, 1992. Google Books, https://books.google.com/books?id=GzgWsZDlVo0C&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false . Accessed 10 Apr. 2019.

Schinke-Llano, Linda, and Robert Vicars. “The Affective Filter and Negotiated Interaction: Do Our Language Activities Provide for Both?” The Modern Language Journal , vol. 77, no. 3, 1993, pp. 325–329. JSTOR , www.jstor.org/stable/329101.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Krashen's Language Acquisition Hypotheses: A Critical Review

Related Papers

International Journal of Social Research

Mzamani Maluleke

The monitor model, being one of its kind postulating the rigorous process taken by learners of second language, has since its inception in 1977, stirred sterile debates the globe over. Since then, Krashen has been rethinking and expanding his hypothetical acquisition notions, improve the applicability of his theory. The model has not been becoming, and it therefore faces disapproval on the basis of its failure to be tested empirically and, at some points, its contrast to Krashen’s earlier perceptions on both first and second language acquisition. In this paper, the writers deliberate upon Krashen’s monitor model, its tenets as well as the various ways in which it impacts, either negatively or positively upon educational teaching and learning.

Amalia Oyarzún

Aufani Yukzanali

Many theories on how language is acquired has been introduced since 19th century and still being introduced today by many great thinkers. Like any other theories which arose from variety of disciplines, language acquisition theories generally derived from linguistics and psychological thinking. This paper concluded that the most important implication of language acquisition theories is obviously the fact that applied linguists, methodologist and language teachers should view the acquisition of a language not only as a matter of nurture but also an instance of nature. In addition, only when we distinguish between a general theory of learning and language learning can we ameliorate the conditions L2 education. To do so, applied linguists must be aware of the nature of both L1 and L2 acquisition and must consider the distinction proposed in this study. Furthermore, no longer should mind and innateness be treated as dirty words. This will most probably lead to innovative proposals for syllabus development and the design of instructional systems, practices, techniques, procedures in the language classroom, and finally a sound theory of L2 teaching and learning.

Karunakaran Thirunavukkarasu

Luz Villarroel Cornejo

Evynurul Laily Zen

This paper aims at revealing the factors that contribute to children's language acquisition of either their first or second language. The affective filter hypothesis (Krashen, 2003) as the underlying framework of this paper is used to see how children's perception towards the language input take a role in the process of acquisition. 25 lecturers in the Faculty of Letters, State University of Malang who have sons or daughters under the age of 10 become the data source. The data are collected through survey method and analyzed qualitatively since this paper is attempting to give a thorough description of the reality in children's language acquisition. The results show that most children are exposed to the language while interacting with their family members, especially their mothers. Another factor is children's interactions with friends. The languages used by their friends are potential to be acquired by them. These two factors strongly confirm the core idea of the affective filter hypothesis that children will learn best when they feel comfortable and are positive about the input they are absorbing. Furthermore, reading is also one of other minor contributing factors discovering the fact that the books the children like helps them construct positive perception which then encourage them import more inputs. 1. Rationale This paper is an attempt to disseminate the result of the survey-based research conducted to have a closer look at the mapping of bilingual language situation seen in certain linguistic situation in Malang. The survey that was conducted to bilingual parents is basically about to satisfy a personal yet scientific curiosity of the researchers as both parents to bilingual children and language teachers. Nothing seems really unique from the fact that children in Indonesia are born to be bilingual because, by nature, they are raised by bilingual parents in bi(multi)lingual situation. On the other hand, there have been an increasing number of studies that explore the nature of bilingual language acquisition. Some have seen negative impact of exposing second language to children (at various angles by which these previous studies have been carried out, the socio-psycholinguistic environment of bilingual children in Malang is obviously worth-researching. One of the focuses of the survey is looking thoroughly at the contributing factors of both the first and second language development of bilinguals that mainly becomes the concern of this paper. Something really significant to start with is the result of the survey seen from Figure 1 below that not only 16% of the children of the respondents are raised monolingual, but also 28% of them are trilingual.

Lazaros Kikidis

For Didactics and Applied Linguistics MA students

Andreas Gozali

Language and Education

Nicole Ziegler

RELATED PAPERS

IAEME PUBLICATION

IAEME Publication

Environmental Science & Technology

Cláudia Mieiro

AMB Express

Keivan Beheshti Maal

PhD Research Sympozium 2018

Jana Matyášová

The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America

Laurent de Ryck

Logos Anales Del Seminario De Metafisica

SERGIO ANTORANZ LOPEZ

Studies in Soviet Thought

Leonid Heller

Microorganisms

Amal SOUIRI

신천스파❝dAlpochA3.넷❞신천오피 달포차✥

LaMont Rouse, Ph.D., M.B.A, M.P.A.

Émile Zola et Octave Mirbeau : regards croisés sur le naturalisme, Anna Gural-Migdal, Sándor Kálai (dir.), Paris, Classiques Garnier

Marion Glaumaud-Carbonnier

Economic Theory

Maria Paz Espinosa

Dávid Tyndale Serveto

Uluslararası Sosyal Bilimler Akademi Dergisi

Asiye Bilgili

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics

Moiz Merghni

Christian Moreau

Revista de Indias

alejandra peña

amir siahpoosh

Marli Roesler

Gerry Kearns

J-CEKI : Jurnal Cendekia Ilmiah

Intan Nurina Seftiniara

AIDS Research and Therapy

YOGESHWAR KUMAR SHARMA

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Call us for help +1 347 434 9694

- Request a callback

Choose your country or territory

- What Is The Affective Filter In Language Learning?

Join a global community of over 200,000 TEFL teachers working throughout the world! Enrol me!

- Classroom Considerations, Teacher's Toolkit

Have you heard of Stephen Krashen? If you’re interested in teaching English as a foreign language, then you should.

If you haven’t, then you’ve come to the right place.

Who is Stephen Krashen?

Stephen Krashen is a well-known name in the EFL industry.

His ideas and theories have been influential in the field of teaching English as a foreign language, mostly because they have stood the test of time.

Krashen came up with five hypotheses of learning , one of which is the affective filter hypothesis.

The affective filter hypothesis basically explains that language cannot be learned if a learner is blocking the learning process.

In other words, a learner can be mentally prepared to learn, or they might be hindering this process in some way.

A learner can have a high affective filter or a low affective filter:

- the higher the filter, the more likely language learning will be impeded;

- the lower the filter, the more likely that language learning will take place.

We can think of the affective filter like a mask.

When a mask is worn over the whole face, a person will have difficulty seeing or speaking, and even hearing – and learning.

When the mask is under their chin, a person is able to see, speak, hear – and learn – much more easily.

What causes a high affective filter?

Stress and discomfort will adversely affect learning.

In order to be able to learn effectively, a learner should feel safe and comfortable in the learning environment. The learner should not experience high levels of stress or anxiety during the learning process. Plus, the learner should feel motivated to participate in learning activities without worrying about making mistakes.

Think about it for a minute: the times you are able to study the hardest are probably times when you feel comfortable and safe. You are relaxed and not under any pressure. You feel calm, both mentally and physically.

This is what we want to replicate in our EFL classrooms.

Read more: How Can Teachers Motivate Learners?

How does this affect the EFL classroom?

This might all seem logical. But you’ll be surprised how easily it can be for students to feel uncomfortable or tense during a lesson.

If you think of situations like public speaking or presenting, you may understand the anxiety students may feel when called on in class.

The fear of making a mistake or looking stupid can be overwhelming.

This can even prevent a student from speaking up or participating in classroom activities. The student won’t benefit as much from the lesson and won’t learn as effectively.

What can the teacher do to lower the affective filter?

There are many things teachers can do to help the situation.

Firstly, make sure the students know each other. If the class is a new one, spend some time on getting-to-know-you activities so that the students can become friends. It’s much easier to speak in front of friends than strangers and students won’t feel embarrassed about making mistakes.

Read more: An Activity For The First Day Of A New EFL Class

When the students do make mistakes, correct them . But don’t make a big deal out of it and don’t do it in an embarrassing way. Ensure you treat your students equally so nobody feels like you are picking on them or making fun of them.

Read more: Encouraging Mistakes in the TEFL Classroom

Bear in mind the physical environment of the classroom.

Is it a sauna, or an igloo? Is there a gale force wind blowing through the windows? Are you students sitting on top of one another?

As the teacher it’s your duty to make sure the classroom is at the right temperature and your students are as comfortable as possible.

The affective filter is just one of many theories related to learning a foreign language. But it’s one worth remembering because as teachers it is something we have a certain amount of control over.

And we all know, happy students = a happy classroom = a happy teacher!

Please note: This blog post was originally published on 5 September 2017 but has been updated.

Dear Sir or Madam, I would like to know the name of the author of the above article in order to use it as a reference in my research paper. All the best,

Follow us on social networks, join our newsletter - get the latest news and early discounts

Sign up to our newsletter

Follow us on social networks, sign up to our e-newsletters – get the latest news and early discounts

Accreditation Partners

The TEFL Academy was the world’s first TEFL course provider to receive official recognition from government regulated awarding bodies in both the USA and UK. This means when you graduate you’ll hold a globally recognised Level 3 (120hr) Certificate or Level 5 (168hr) Diploma, meaning you can find work anywhere and apply for jobs immediately.

- 4.89 Average

- 3444 Reviews

Eranne Hancke...

I studied the Level 5 Tefl course, I thoroughly enjoyed the course as it challenged me and often made me think out of the box. The combination of short quizzes…

Anne Clarisse O...

The Level 5 TEFL Course with TheTEFLAcademy helped me out a lot and answered many questions I had in regards to teaching English, both to adults and kids. They help…

Mikaila Rachel ...

So incredibly put together and such a lovely team of people to work with!

Candice Kapp...

Very good course! Taught me everything about English that I needed to know. Gave me lots of helpful information needed for teaching. They give you access to their job board…

Louise Morrison...

I highly recommend the TEFL Academy. I have just completed the Level 5 online TEFL course with them. The course was very comprehensive and easy to follow. Learning was kept…

Nadine Olivia M...

I have had a passion for teaching within me since a very young age, after a bad experience on my first attempt of teaching I thought it wasn't for me.…

Product added to your cart

You have added to your cart:

- Close window

Request call back

Please leave your details below and one of our TEFL experts will get back to you ASAP:

ASAP Morning Afternoon Evening

Afghanistan Albania Algeria Andorra Angola Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Armenia Australia Austria Azerbaijan The Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belarus Belgium Belize Benin Bhutan Bolivia Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana Brazil Brunei Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi Cambodia Cameroon Canada Cape Verde Central African Republic Chad Chile China Colombia Comoros Congo, Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of the Costa Rica Cote d'Ivoire Croatia Cuba Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Djibouti Dominica Dominican Republic East Timor (Timor-Leste) Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Fiji Finland France Gabon The Gambia Georgia Germany Ghana Greece Grenada Guatemala Guinea Guinea-Bissau Guyana Haiti Honduras Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Iran Iraq Ireland Israel Italy Jamaica Japan Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Kiribati Korea, North Korea, South Kosovo Kuwait Kyrgyzstan Laos Latvia Lebanon Lesotho Liberia Libya Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg Macedonia Madagascar Malawi Malaysia Maldives Mali Malta Marshall Islands Mauritania Mauritius Mexico Micronesia, Federated States of Moldova Monaco Mongolia Montenegro Morocco Mozambique Myanmar (Burma) Namibia Nauru Nepal Netherlands New Zealand Nicaragua Niger Nigeria Norway Oman Pakistan Palau Panama Papua New Guinea Paraguay Peru Philippines Poland Portugal Qatar Romania Russia Rwanda Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Samoa San Marino Sao Tome and Principe Saudi Arabia Senegal Serbia Seychelles Sierra Leone Singapore Slovakia Slovenia Solomon Islands Somalia South Africa South Sudan Spain Sri Lanka Sudan Suriname Swaziland Sweden Switzerland Syria Taiwan Tajikistan Tanzania Thailand Togo Tonga Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan Tuvalu Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates United Kingdom United States of America Uruguay Uzbekistan Vanuatu Vatican City (Holy See) Venezuela Vietnam Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe

Would you like us to update you on TEFL opportunities, jobs and related products & services?

Yes, keep me updated No, but thanks anyway!

I consent to the Privacy Policy *

Thank you! Your message has been sent!

Download the TEFL World Factbook

Please enter your details in order to download the latest TEFL World Factbook.

Thank you for downloading the TEFL World Factbook!

If the TEFL World Factbook did not download > Click Here To Download

Download the Online Teaching Guide

Please enter your details in order to download our Online Teaching Guide.

Thank you for downloading our Online Teaching Guide!

If the Online Teaching Guide did not download > Click Here To Download

- Download Prospectus

Please enter your details in order to download our latest prospectus.

Thank you for downloading our prospectus!

We hope you enjoy reading our prospectus, we have tried to make it as useful as possible! Please get in touch if you have any questions.

If the prospectus did not download automatically > Click Here To Download

Terms and Conditions

1. our contract with you.

- Details of the TEFL Courses can be found here .

- Please read these Terms carefully before you submit your order for enrolment in a TEFL Course to us. These Terms tell you who we are, how we will provide services to you, how you and we may change or end the contract, what to do if there is a problem and other important information. You must indicate your acceptance of these Terms before you can submit your order for a course with The TEFL Academy.

- Our acceptance of your booking will take place when you receive a confirmation email from us to accept your order, at which point a contract will come into existence between you and us.

- Once you have received an email acceptance of your order, these Terms will form the basis of the contract between you, the student, and us The TEFL Academy, to the exclusion of all other terms and conditions. Any variations to these Terms shall have no effect unless agreed in writing.

- All students studying the combined course option must print their confirmation email and bring it to the first day of their course or have the confirmation email accessible on a smartphone.

2. Information about us

- We are ELEARNING FUTURES LTD (trading as The TEFL Academy) a company registered in the United Kingdom. Registered company number 13725845, Palmeira Avenue Mansions, 19 Church Road, Hove, BN3 2FA.

- Our USA address is: The TEFL Academy, 954 Lexington Ave, #1135 New York, NY 10021, USA.

- You can contact us by telephoning our customer service team at +1 347 434 9694 or by emailing us at [email protected] .

- These Terms shall commence upon the date you receive a confirmation email from us to accept your order and shall continue for the duration of the TEFL Course or until cancelled pursuant to these Terms.

- You will be obliged to comply with these Terms for the duration of the TEFL Course you are enrolled in unless the course is cancelled early in accordance with these Terms. Any terms expressed to survive termination shall so survive and shall be enforceable by us for a period of 6 years after termination.

- If you need a course extension, this can be arranged at a fee. Please contact [email protected] or call +1 347 434 9694 for more details and information on how to apply for an extension.

- The TEFL Academy reserves the right to change our course prices or other services on our website at any time at our sole discretion, and such amended prices or services shall be kept up to date on our website and available here. Our website shall also maintain up to date details of our special offers here .

- The fees for extensions or cancellations can be found at clauses 3.5, 6.2 and 7.

- For classroom-based courses. transport to and accommodation at the venue is not included in the price of the combined TEFL course. Food and other related costs are not included in the combined TEFL course price.

- All payments can be made by credit or debit card through our payment processor WorldPay or through Paypal. The TEFL Academy does not process any card payments directly on our server. The payment page on the website will direct you to a separate Paypal or Worldpay page depending on the payment option selected by you. We do not store or process personal financial information.

- If the date for your chosen course is more than two weeks away, you have the option of paying a deposit. You will be invoiced for the remaining balance with a payment link to the email address used to make your booking. The remaining balance must be paid in full no longer than one week before the course date. All balance payments are non-refundable. Access to the online course is provided on receipt of the full balance payment.

6. Changing or Cancelling your course

- If for whatever reason you wish to change the date of your course, you must notify us of the change at least seven days prior to the course date. Any changes requested will only be accepted for available dates within the next three months from the original course date and must be at the same location. All changes are subject to availability and only one change per booking will be accepted.

- Please note: Subject to clause 7, under no circumstances whatsoever will changes or cancellations be accepted less than 7 days before the course date. Any student who wishes to change course or cancel within the 7 days of the course date, for whatever reason, will forfeit their course fee.

7. Right of Withdrawal

- You shall have a period of 14 days from the day of the conclusion of the contract to withdraw from the contract (cancelling your enrolment) for no reason, and without incurring any costs other than those provided for in clause 6.2 where applicable.

- If you wish to exercise your right of withdrawal, you must inform The TEFL Academy of your decision to withdraw from the contract within this 14 days by making a request in writing via our refund form ( found here ), or by making a statement in writing setting out your decision to withdraw from the contract.

- The exercise of the right of withdrawal shall terminate the obligations of the parties to perform the contract. The TEFL Academy will reimburse you in respect of all payments received from you within 14 days of withdrawal using the same means of payment as the you used for the initial transaction.

8. Course Cancellation by The TEFL Academy

- Where a course cannot take place due to trainer illness or other circumstances beyond our control, the course may be cancelled by us. The TEFL Academy will endeavour to provide an alternative trainer but this is not always possible. We will try and arrange an alternative date, but if any new arrangements are not suitable, a full refund will be offered. In these circumstances we accept no liability for any loss or expenses incurred by you including, without limitation, any travel, accommodation costs or loss of earnings.

- In the event that a classroom course cannot take place as a result of, or connected with, delay or interruption to travel services, adverse weather conditions, civil disturbance, industrial action, strikes, wars, floods, sickness, pandemics, epidemics or any other commonly accepted event of force majeure, The TEFL Academy will endeavour to offer a classroom course at an alternative date or will seek to transfer your booking to the online course or failing these options will transfer your booking to the reserves list (where you will be placed on a list until you select an alternative suitable classroom date and can continue with the online element of the course). A refund (including the difference in cost between different course options, if and where applicable) will not be permitted in any of the above circumstances, unless the cancellation of the course for these reasons occurs within 14 days from booking.

9. Access to Course and Materials

- The 6-month enrolment on the online course starts from the date that full payment for the course has been received by The TEFL Academy.

- All assignments must be submitted no later than 2 weeks before the enrolment end date. Students who wish to apply for an extension to the enrolment end date, may incur additional fees. An extension will run from the previous enrolment end date or if you are paying the post expiry fee, from the date the full extension payment is received by The TEFL Academy.

- Access to the online course materials will cease upon expiration of enrolment.

- All online courses require a computing device and stable internet connection. The full requirements can be found here .

- All course data, including test scores and assignments, will be stored no more than 12 months from the final day of enrolment on the online course. Students will be notified by email of this deadline 30 days before deletion. Students who wish to retain their online course content beyond the 12-month storage date will be required to purchase an extension as per clauses 3 and 4.

10. Assignments and Exams

- As part of some TEFL Courses you will be required to prepare and submit assignments. If you do not pass an assignment you can resubmit an assignment in accordance with clause 10.2.

- You can submit each assignment up to three times. (i.e. after the first submission of an assignment, you may re-submit the assignment a two further times up to a total of three submissions for one assignment).

- If you do not pass an assignment, you will not receive a grade, but you will be given feedback as to why you have not passed and you shall be given the opportunity to re-submit your work up to a total of 3 submissions per assignment in accordance with clause 10.2. You will not be able to resubmit an assignment which you have been awarded a pass grade in.

- If you have a basis to believe your work has not been fairly assessed, you can request a re-mark via the tutor support ticket platform. Due to the high number of students we cannot look at any assignment in advance of an actual submission.

- You should submit your final assignment 2 weeks before your end date to allow time for marking and the possible need for re-submission.

- Please be aware that if you have not completed all required assignments and allowed sufficient time for marking before your end-date, you will need to apply for an extension.

- You are entitled to sit exams as many times as you need to in order to pass the exam. If you pass the exam you cannot thereafter seek to resit the exam.

11. Failing the Course

- The TEFL Academy offers a guaranteed pass, or your money back guarantee. You can retake the exams as many times as needed in order to pass. If you fail to achieve a pass on any assignments after your third attempt we will provide you with a full refund. A full refund will not be provided in accordance with clauses 11.4, 11.5 & 11.8.

- Native speakers of English will typically be above the minimum standard of English for this course.

- Non-native speakers should have an English level of C1 (Advanced), as a minimum to commence the course. Students may test their English level here: https://learnenglish.britishcouncil.org/en/content .

- Students found not to have a C1 level of English will likely fail the course and not complete the qualification. However, it is up to each prospective student to determine for themselves whether or not they wish to commence a course even where they do not have a minimum of C1 level English. For the avoidance of any doubt no refund will be provided for a student failing the course in any circumstances.

- Any student who fails or is removed from the course as a result of confirmed plagiarism (in accordance with clause 11.6) will be removed immediately from the course without refund. All extension payments are non-refundable.

- Where an assignment marker finds evidence that indicates that plagiarism may have occurred within a submitted assignment, this will be escalated to an Internal Quality Assurance Manager for investigation who will compare the submitted assignment to the source it is believed to be plagiarised from. The Internal Quality Assurance Manager will make an assessment as to whether they consider plagiarism to have occurred. In the event the Internal Quality Assurance Manager decides that plagiarism has occurred, they will prepare and provide to you a detailed report outlining the reasons for their decision along with a letter explaining your removal from the course. Should you wish to dispute this decision, you can do so in accordance with The TEFL Academy’s Appeals policy for students which can be found here .

- If you do not pass an assignment after submitting it up to three times in accordance with clause 10.2 you will be deemed to have failed the course. Should you wish to dispute this decision, you can do so in accordance with The TEFL Academy’s Appeals policy for students which can be found here . If you fail the course due to not passing your assignments you will be provided with a full refund. As extensions are an optional expenditure, any extension payments will not be refunded.

- In order for you to legitimately fail the course, a clear attempt to answer the assignment requirements must be made. This requires uploading the required assignment templates for each submission, and an attempt to address feedback and recommendations provided by the tutor for the second and third attempts. If we deem your attempts at the assignments to not be genuine a refund will not be provided.

- Any student who has been removed from their course due to plagiarism will be banned indefinitely from enrolling in any course with The TEFL Academy.

12. Liability

- The TEFL Academy accepts no liability, nor shall it have any liability whether in contract, tort, under statute or otherwise, for any loss, damage, costs, liabilities or additional expense arising from, or in connection with, any delay or interruption to travel services, weather conditions, civil disturbance, industrial action, strikes, wars, floods, sickness or other events of force majeure. Such losses or additional expenses are your responsibility. Force majeure (for the purposes of this clause) means any unusual and/or unforeseeable circumstances such as war or the threat of war, riots, terrorist activity, civil strife, pandemics, epidemics, industrial disputes, natural or nuclear disaster, fire, flood or adverse weather conditions.

- The TEFL Academy accepts no responsibility, nor shall it have any liability whether in contract, tort, under statute or otherwise, for death, bodily injury or illness caused to you or any other person included on the booking, except where it arises from any negligent act or omission of The TEFL Academy.

- The TEFL Academy accepts no liability, nor shall it have any liability whether in contract, tort, under statute or otherwise, any technical or IT issues arising from or connected with the usage of the online courses such as systems crashing.

- Our internship/volunteer opportunities and the jobs posted on our jobs board are provided by third parties. Although we will endeavour to assist students, we accept no liability for the actions or conduct of any third-party organisation.

- The TEFL Academy endeavours to ensure all assignments are marked promptly. However, there can be delays in busier times or due to moderation requests from our accrediting body. The TEFL Academy accepts no responsibility for any loss or other circumstances resulting or arising from such delays.

- The TEFL Academy accepts no liability, nor shall it have any liability whether in contract, tort, under statute or otherwise, for any loss or additional expense arising for students where they fail the course whether such failure is alleged to be due to trainers allegedly lacking competency, for plagiarism or for any other reason whatsoever.

13. Complaints Handling Policy

- If you have any questions or complaints about the TEFL Course, please contact us. You can telephone our customer service team at +1 347 434 9694 or write to us at [email protected] or The TEFL Academy, Suite 4 The Hub, 3 Drove Road, Newhaven, BN9 0AD, United Kingdom.

- If your complaint is not dealt to your satisfaction with you may make a complaint to the course accrediting body. You can find the contact details for the accrediting body in the The TEFL Academy’s Appeals Policy which can be found here .

14. Conduct

- Our staff have the right not to be subjected to aggressive, abusive or offensive language or behaviour, regardless of the circumstances. Examples of this behaviour include but are not limited to; threats of physical violence; swearing; inappropriate cultural, racial or religious references; rudeness, including derogatory remarks. The TEFL Academy practises a zero-tolerance policy in relation to such behaviour. All students are required at all times to conduct themselves in an appropriate manner including in their dealings with other students, staff and external organisations. Disruptive or antisocial behaviour could result in being asked to leave the course.

- Any student who fails or is removed from the course by failing to meet the academic standards or through being found guilty of plagiarism will be removed immediately from the course without refund.

15. Data Protection

- Any use which we make of your personal data which you may provide in using The TEFL Academy site will be in accordance with all applicable data protection laws and The TEFL Academy Privacy Policy which can be found here .

- Please read The TEFL Academy Privacy Policy carefully as it contains important information on how the TEFL Academy uses your personal information.

16. Governing Law

- This Agreement is governed by the laws of England & Wales.

- Any claims made in connection with these Terms shall be subject to English law and all proceedings shall be within the sole domain of the English courts.

17. Acceptance of these Terms

- By verbally agreeing on the telephone or having clicked ‘Enrol Now’ on the website you accept these Terms including all payment obligations and you are acknowledging that placing an order creates an obligation to pay for the services ordered and confirms that you have read, agreed to and accepted these terms. The person who agrees to the enrolment agreement, does so on behalf of all the individuals included on it, so that all are bound by the enrolment conditions.

Privacy Policy

LAST UPDATED: 19th July 2023

Please read all of the following information carefully.

By using our site and/or registering with us, you are agreeing to the terms of this Policy.

ELEARNING FUTURES LTD (“we”) are committed to protecting and respecting your privacy.

ELEARNING FUTURES LTD takes the security of and our legal responsibilities around your personal data seriously. This statement explains relevant information about our processing of your personal data collected via this website (“website” or “site”).We aim to always respect your data protection rights in compliance with the latest Data Protection Laws, including the GDPR.

- This website is owned and operated by ELEARNING FUTURES LTD , (we) a limited company registered in the United Kingdom. Registered company number 13725845, Palmeira Avenue Mansions, 19 Church Road, Hove, BN3 2FA.

- This Policy sets out the basis on which any personal data we collect from you, or that you provide to us, will be processed by us.

- Our Data Protection Officer (DPO) can be contacted by email at [email protected]

- This policy (and any other documents referred to on it) sets out the basis on which any personal data we collect from you, or that you provide to us, will be processed by us. Please read the following carefully to understand our practices regarding your personal data and how we will treat it.

- For the purpose of the General Data Protection Regulation, the data controller is ELEARNING FUTURES LTD.

Contact Details

- ELEARNING FUTURES LTD collects and processes personal information for a variety of reasons. If you wish to communicate with us about this privacy notice, or any issue relating to information governance or data protection, please contact us using the following details: By post: Information Governance & Risk Management Team ELEARNING FUTURES LTD, Palmeira Avenue Mansions, 19 Church Road, Hove, BN3 2FA, United Kingdom Email: [email protected]

International transfers

- ELEARNING FUTURES LTD shares personal information within the wider ELEARNING FUTURES LTD group of entities situated both within and outside the EU. We do this under a data-sharing agreement that includes the appropriate EU model international data transfer clauses to make sure your personal information is protected, no matter which entity in the ELEARNING FUTURES LTD group holds that information.

- Where ELEARNING FUTURES LTD makes transfers of personal information outside the ELEARNING FUTURES LTD Group to another organisation we rely on the use of the EU model international data transfer clauses where the country the organisation is situated in is not listed as ‘adequate’ by the European Commission.

Collection and Use of your data

- Some data will be collected automatically by our site, other data will only be collected if you voluntarily submit it and consent to us using it for the purposes set out in section 5, for example, when signing up for an account. depending upon your use of our site, we may collect some or all of the following data: Name, address, bank details and so forth.

- All personal data is stored securely in accordance with the EU General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679) (GDPR). For more details on security see section 6, below.

- Providing and managing your account;

- Providing and managing your access to our site;

- Personalising and tailoring your experience on our site;

- Supplying our services to you;

- Personalising and tailoring our services for you;

- Responding to communications from you;

- Supplying you with email newsletters or alerts etc. that you have subscribed to, you may unsubscribe or opt-out at any time by clicking on the ‘unsubscribe to the list’ link at the footer of our email newsletters or by contacting our Customer Services Team at [email protected]

- Market research;

- Analysing your use of our site and gathering feedback to enable us to continually improve our site and your user experience;

- Ensuring our investigations and appeals are handled accurately and fairly;

- In some cases, the collection of data may be a statutory or contractual requirement, and we will be limited in the services we can provide you without your consent, for us to be able to use such data.

- With your permission and/or where permitted by law, we may also use your data for marketing purposes which may include contacting you by email AND/OR telephone AND/OR text message AND/OR post with information, news and offers on our services. We will not, however, send you any unsolicited marketing or spam and will take all reasonable steps to ensure that we fully protect your rights and comply with our obligations under the GDPR and the Privacy and Electronic Communications (EC Directive) Regulations 2003, as amended in 2004, 2011 and 2015.

- In order to facilitate completion of enrolment, we do collect data from our online booking forms and may remind you of your saved order so that you can complete your enrolment

- you have given consent to the processing of your personal data for one or more specific purposes;

- processing is necessary for the performance of a contract to which you are a party or in order to take steps at the request of you prior to entering into a contract;

- processing is necessary for compliance with a legal obligation to which we are subject;

- processing is necessary to protect the vital interests of you or of another natural person;

- processing is necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or the exercise of official authority vested in the controller; and/or

- processing is necessary for the legitimate interests pursued by us or by a third party, except where such interests are overridden by the fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject which require protection of personal data, in particular where the data subject is a child.

We collect and use personal information to offer people information, products and services. This policy will apply in all locations where we operate to all forms of information and to all systems used to collect, store, process or transfer information.

- performing privacy impact assessments to protect the privacy and rights of its customers and employees

- protecting the confidentiality, integrity and availability of the information it collects, stores, transfers and processes in accordance with law and international good practice, and meeting its legal requirements and contractual obligations

- explaining why it needs personal information, only asking for the personal information it needs and only sharing personal information within the ELEARNING FUTURES LTD and with other organisations as necessary or where the person concerned has given their consent

- allowing people to request access to the personal information it holds on them and to complain if they believe their information has been mishandled

- not keep personal information for longer than necessary

- taking measures to protect the rights and freedoms of individuals whose personal information may be transferred to countries with differing data protection laws

- ensuring that actual or suspected breaches of information security are reported and investigated

- assessing and measuring the maturity of its information security controls annually

- applying these standards to its supply chain and delivery partners.

- Provide customer service, surveys and marketing

- Personalise our services

- Process payments

- Carry out fraud and other legal investigations

- We also, in certain situations, share personal information with government bodies and law enforcement bodies. Where we do share personal information with these types of organisations we’ll make sure it’s protected, as far as it is reasonably possible.

We’ll use your personal information to send you direct marketing and to better identify products and services that interest you. We do that if you’re one of our customers or if you’ve been in touch with us another way (such as registering to attend an ELEARNING FUTURES LTD event).

This means we’ll:

- create a profile about you to better understand you as a customer and tailor the communications we send you (including our marketing messages);

- tell you about other products and services you might be interested in;

- try to identify products and services you’re interested in; and

We use the following for marketing and to identify the products and services you’re interested in.

- Your contact details. This includes your name, gender, address, phone number, date of birth and email address.

- Information from cookies and tags placed on your connected devices.

- Information from other organisations such as aggregated demographic data and publicly available sources like the electoral roll and business directories.

- Details of the products and services you’ve bought and how you use them.

We’ll send you information (about the products and services we provide) by phone, post, email, text message, online banner advertising. We also use the information we have about you to personalise these messages wherever we can as we believe it is important to make them relevant to you. We do this because we have a legitimate business interest in keeping you up to date with our products and services. We also check that you are happy for us to send you marketing messages before we do so. In each message we send, you also have the option to opt-out.

We’ll only market other organisations’ products and services if you have said it is OK for us to do so.

You can ask us to stop sending you marketing information or withdraw your permission at any time.

ELEARNING FUTURES LTD retains personal information in line with our corporate retention requirements. Your data will be stored within the European Economic Area (“the EEA”) (The EEA consists of all EU member states, plus Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein). However, in some circumstances, part or all of your data may be stored or transferred outside of the European Economic Area (“the EEA”). You are deemed to accept and agree to this by using our site and submitting information to us. If we do store or transfer data outside the EEA, we will take all reasonable steps to ensure that your data is treated as safely and securely as it would be within the EEA and under the GDPR. Such steps may include, but not be limited to, the use of legally binding contractual terms between us and any third parties we engage with, and the use of the EU-approved Model Contractual Arrangements. If we intend at any time to transfer any of your data outside the EEA, we will always obtain your consent beforehand.

Right to access personal information

- Under the law, any individual has a right to ask for a copy of the personal information held about them. This means that you can ask for the information that ELEARNING FUTURES LTD holds about you. This is known as the right of ‘subject access’.

- a request in writing (by post or by email)

- proof of your identity

- proof of your home address

- any information that we reasonably need to locate the information you have requested (for example details of the ELEARNING FUTURES LTD offices or staff that you have had contact with and when)

Rights concerning the processing of your personal information

- Right to restrict processing of personal information

- In some situations, you have the right to require us to restrict the processing of your personal information. We may restrict your personal information by temporarily moving the information to another processing system, making the information unavailable to users, or temporarily removing published information from a website. We may also use technical methods to ensure the personal information is not subject to further processing and cannot be changed. When we have restricted processing of personal information, this will be clearly indicated on our systems.

- You are concerned that the information we hold about you is inaccurate. You can ask us to restrict the information until we can determine whether the information is accurate or inaccurate.

- We are processing your personal data unlawfully and you do not want us to delete the information but restrict it instead.

- We no longer need the information for the purposes for which we collected it, but they are needed by you for the establishment, exercise or defence of legal claims.

- You have objected to the processing (see below), and we need to decide whether the legitimate grounds we have to process the information override your legitimate interests.

Processing you think is unlawful

- If you tell us that you think we are processing your personal information unlawfully, but you do not want the information to be erased, you have the right to require us to restrict the processing of that information.

- We will ask you for an explanation about why you think the processing is unlawful, and may also ask that you provide evidence to support this view.

Processing of personal information you think is inaccurate

- You can tell us if you think the personal information we are processing about you is factually inaccurate. You can require us to restrict how we use your personal information until we can verify the accuracy of the information. We will ask you for an explanation about why you think the information is inaccurate, and may also ask that you provide some supporting evidence of the alleged inaccuracy.

- If we find that the personal information we are processing about you is inaccurate, we will take appropriate steps to correct the information.

Personal information is no longer needed by ELEARNING FUTURES LTD but needed by you in connection with a legal claim

- In most circumstances, we will securely delete or dispose of personal information when we no longer need it for our legitimate business purposes. Our approach to retention is outlined in our corporate retention schedules.

- However, if the personal information we no longer need would assist you in establishing, exercising or defending a legal claim, you can require us to keep the information for as long as necessary. We may ask you to provide an explanation and any available supporting evidence that a legal claim is ongoing or contemplated.

Right to erasure of personal data (“the right to be forgotten”)

In the following circumstances, you have the right to require that ELEARNING FUTURES LTD securely deletes or destroys your personal information:

- If the personal information we hold about you is no longer necessary for the purposes for which we originally collected it.

- The processing is based on consent – if you have previously given your consent to ELEARNING FUTURES LTD collecting and processing your personal information, and you notify us that you withdraw your consent. Please note: withdrawing your consent does not mean the processing of your personal data which occurred before the withdrawal was unlawful.

- We are processing your personal information for direct marketing purposes, and you want us to stop.

- If you think ELEARNING FUTURES LTD has processed your personal information unlawfully.

If you think any of the above situations apply, we may ask you for an explanation and further information to verify this.

Right to object to processing

You have the right to object to the ELEARNING FUTURES LTD processing your personal data in the following circumstances:

Personal information used for direct marketing

If we are using your personal information to send you direct marketing, you have the right to object at any time. If you exercise this right, we will stop processing your personal information for direct marketing purposes. However, we may keep your information on a “suppression list” to ensure your information is not added to any marketing lists at some point in the future.

Automated decision making and profiling

- ‘Profiling’ is the automated use of personal data held on a computer to analyse or predict things that have a legal effect, or other similarly significant effects, on the individual. Examples would include economic situation, health, personal preferences or interests and location. You have the right not to be subject to a solely automated decision (that is, a decision made electronically, with no human intervention), and this may include profiling (although there is no general right to object to profiling). If you are concerned the ELEARNING FUTURES LTD has made a solely automated decision about you, you can object.

- Please note, ELEARNING FUTURES LTD is allowed to carry out automated decisions with no human intervention where you have given your explicit consent to this processing (although you have the right to withdraw your consent).

- The automated decision is necessary to enter into, or perform a contract, or complete a contract involving you and the ELEARNING FUTURES LTD.

- The automated decision is allowed under a law passed at the European Union level, or at the level of the European Union or EEA member state level (i.e., is allowed under national law). The law will provide safeguards to protect your rights and freedoms.

Right to data portability

- If you have provided your information to ELEARNING FUTURES LTD, you have the right to request and receive a copy of that information in a structured, commonly used and machine-readable format.

- You also have the right to ask us to send the information we hold about you to another organisation.

- There are some situations in which the right to data portability does not apply. For further information, please contact us.

Exercising your rights concerning the processing of your personal information

If you wish to exercise any of the above rights concerning the way in which we process your personal information, please contact:

By post: Risk Management Team ELEARNING FUTURES LTD, Suite 101b, 21-22 Old Steine, Brighton, BN1 1EL, United Kingdom

Email: [email protected]

Your right to complain to a national data protection regulator (data protection supervisory authority)

- If you think we have processed your personal information unfairly or unlawfully, or we have not complied with your rights under GDPR, you have the right to complain to a national data protection regulator.

- Complaints about how we process your personal information can be considered by the data protection regulator.

Changes to Our Privacy Policy

We may change this Privacy Policy as we may deem necessary from time to time, or as may be required by law. Any changes will be immediately posted on our site and you will be deemed to have accepted the terms of the Privacy Policy on your first use of our site following the alterations. We recommend that you check this page regularly to keep up-to-date.

- TEFL Courses

- TEFL Course Locations

- Teach English Online

- Teaching Opportunities

- How TEFL works

- Why Choose Us?

- Charity Partnership

- Accreditation

- Meet Our Alumni

- Meet Our Trainers

- Company Profile

- Testimonials

- View All TEFL Courses

- View All Online TEFL Courses

- Online TEFL Course (Level 3 - 120hrs)

- Online TEFL Course (Level 5 - 168hrs)

- Combined TEFL Course (Level 5 - 168hrs)

- Observed Teaching Practice Course (Level 5 - 40hrs)

- TEFL Top-up Courses

- Online TEFL Courses Preview

- Online TEFL Jobs

- Teaching English Online Blogs

- Download Online Teaching Guide

- Teaching English Online & 1:1 Top-up Course

- Teach English Abroad

- TEFL Internships

- TEFL Volunteering

- Teaching Without A Degree

- Beginner's Guide to TEFL

- TEFL Knowledge Base

- Certificate Verification

Introduction The Acquisition-Learning Hypothesis The Natural Order Hypothesis The Monitor Hypothesis The Input Hypothesis The Affective Filter Hypothesis Curriculum Design Conclusions Bibliography