- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

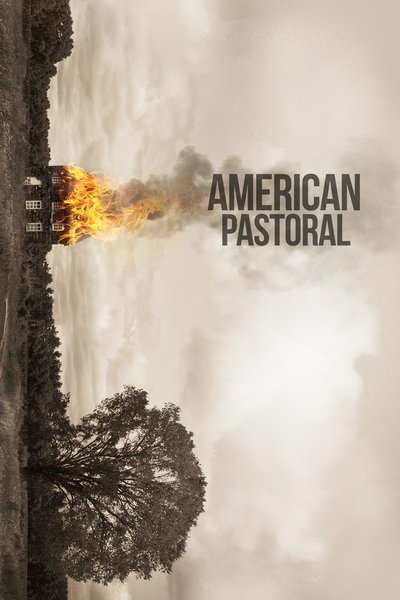

AMERICAN PASTORAL

by Philip Roth ‧ RELEASE DATE: May 12, 1997

Roth's elegiac and affecting new novel, his 18th, displays a striking reversal of form—and content—from his most recent critical success, the Portnoyan Sabbath's Theater (1995). Its narrator, however, is a familiar Rothian figure: writer Nathan Zuckerman (of The Ghost Writer , et al.)—and in case you're wondering whether he still seems to be his author's alter ego, Nathan is now in his early 60s, recovering from both cancer surgery and a longtime affair with an English actress. Essentially retired, Nathan is approached by a high-school classmate's older brother—and the well-remembered hero of his youth: Seymour "Swede" Levov, once a blue-eyed athletic and moral paragon who strode through life with ridiculous ease, now nearing 70 and crushed by outrageous misfortunes. Swede asks his help writing a tribute to his late father, and soon thereafter dies himself. Piqued by the enigma of a seemingly perfect life (superb health, a successful family business, marriage to a former beauty queen) inexplicably gone wrong, Zuckerman "dream[s] a realistic chronicle" that reconstructs Swede's life—compounded of information gleaned from others who knew him, and centering in the 1960s when Swede's life began to unravel. His only daughter Meredith ("Merry") had rebelled against her parents' and her culture's complacency, protested against the war in Vietnam, claimed responsibility for a terrorist bombing in which innocent people were killed, and gone "underground" as a fugitive. Most of the scenes Zuckerman/Roth imagines, therefore, are intensely emotional conversations in which the conflicting claims of social solidarity and individual integrity are debated with pained immediacy. Here, and in more conventionally expository authorial passages, meditativeness and discursiveness predominate over drama. Nevertheless, passion seethes through the novel's pages. Some of the best pure writing Roth has done. And Swede Levov's anguished cry "What the hell is wrong with doing things right?" may be remembered as one of the classic utterances in American fiction.

Pub Date: May 12, 1997

ISBN: 0-395-86021-0

Page Count: 432

Publisher: Houghton Mifflin

Review Posted Online: May 19, 2010

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 1, 1997

LITERARY FICTION

Share your opinion of this book

More by Philip Roth

BOOK REVIEW

by Philip Roth

More About This Book

PERSPECTIVES

SEEN & HEARD

HOUSE OF LEAVES

by Mark Z. Danielewski ‧ RELEASE DATE: March 6, 2000

The story's very ambiguity steadily feeds its mysteriousness and power, and Danielewski's mastery of postmodernist and...

An amazingly intricate and ambitious first novel - ten years in the making - that puts an engrossing new spin on the traditional haunted-house tale.

Texts within texts, preceded by intriguing introductory material and followed by 150 pages of appendices and related "documents" and photographs, tell the story of a mysterious old house in a Virginia suburb inhabited by esteemed photographer-filmmaker Will Navidson, his companion Karen Green (an ex-fashion model), and their young children Daisy and Chad. The record of their experiences therein is preserved in Will's film The Davidson Record - which is the subject of an unpublished manuscript left behind by a (possibly insane) old man, Frank Zampano - which falls into the possession of Johnny Truant, a drifter who has survived an abusive childhood and the perverse possessiveness of his mad mother (who is institutionalized). As Johnny reads Zampano's manuscript, he adds his own (autobiographical) annotations to the scholarly ones that already adorn and clutter the text (a trick perhaps influenced by David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest ) - and begins experiencing panic attacks and episodes of disorientation that echo with ominous precision the content of Davidson's film (their house's interior proves, "impossibly," to be larger than its exterior; previously unnoticed doors and corridors extend inward inexplicably, and swallow up or traumatize all who dare to "explore" their recesses). Danielewski skillfully manipulates the reader's expectations and fears, employing ingeniously skewed typography, and throwing out hints that the house's apparent malevolence may be related to the history of the Jamestown colony, or to Davidson's Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of a dying Vietnamese child stalked by a waiting vulture. Or, as "some critics [have suggested,] the house's mutations reflect the psychology of anyone who enters it."

Pub Date: March 6, 2000

ISBN: 0-375-70376-4

Page Count: 704

Publisher: Pantheon

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 1, 2000

More by Mark Z. Danielewski

by Mark Z. Danielewski

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

Kirkus Reviews' Best Books Of 2019

New York Times Bestseller

IndieBound Bestseller

NORMAL PEOPLE

by Sally Rooney ‧ RELEASE DATE: April 16, 2019

Absolutely enthralling. Read it.

A young Irish couple gets together, splits up, gets together, splits up—sorry, can't tell you how it ends!

Irish writer Rooney has made a trans-Atlantic splash since publishing her first novel, Conversations With Friends , in 2017. Her second has already won the Costa Novel Award, among other honors, since it was published in Ireland and Britain last year. In outline it's a simple story, but Rooney tells it with bravura intelligence, wit, and delicacy. Connell Waldron and Marianne Sheridan are classmates in the small Irish town of Carricklea, where his mother works for her family as a cleaner. It's 2011, after the financial crisis, which hovers around the edges of the book like a ghost. Connell is popular in school, good at soccer, and nice; Marianne is strange and friendless. They're the smartest kids in their class, and they forge an intimacy when Connell picks his mother up from Marianne's house. Soon they're having sex, but Connell doesn't want anyone to know and Marianne doesn't mind; either she really doesn't care, or it's all she thinks she deserves. Or both. Though one time when she's forced into a social situation with some of their classmates, she briefly fantasizes about what would happen if she revealed their connection: "How much terrifying and bewildering status would accrue to her in this one moment, how destabilising it would be, how destructive." When they both move to Dublin for Trinity College, their positions are swapped: Marianne now seems electric and in-demand while Connell feels adrift in this unfamiliar environment. Rooney's genius lies in her ability to track her characters' subtle shifts in power, both within themselves and in relation to each other, and the ways they do and don't know each other; they both feel most like themselves when they're together, but they still have disastrous failures of communication. "Sorry about last night," Marianne says to Connell in February 2012. Then Rooney elaborates: "She tries to pronounce this in a way that communicates several things: apology, painful embarrassment, some additional pained embarrassment that serves to ironise and dilute the painful kind, a sense that she knows she will be forgiven or is already, a desire not to 'make a big deal.' " Then: "Forget about it, he says." Rooney precisely articulates everything that's going on below the surface; there's humor and insight here as well as the pleasure of getting to know two prickly, complicated people as they try to figure out who they are and who they want to become.

Pub Date: April 16, 2019

ISBN: 978-1-984-82217-8

Page Count: 288

Publisher: Hogarth

Review Posted Online: Feb. 17, 2019

Kirkus Reviews Issue: March 1, 2019

More by Sally Rooney

by Sally Rooney

BOOK TO SCREEN

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

- The New York Review of Books: recent articles and content from nybooks.com

- The Reader's Catalog and NYR Shop: gifts for readers and NYR merchandise offers

- New York Review Books: news and offers about the books we publish

- I consent to having NYR add my email to their mailing list.

- Hidden Form Source

April 18, 2024

Current Issue

American Pastoral

November 19, 2009 issue

Submit a letter:

Email us [email protected]

Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits

Daring to Look: Dorothea Lange's Photographs and Reports from the Field

Published in 1935 in the middle of the Depression, William Empson’s Some Versions of Pastoral casts a hard modern light on sixteenth- and seventeenth-century poems about shepherds and shepherdesses with classical names like Corydon and Phyllida. Pastoral, Empson wrote, was a “puzzling form” and a “queer business” in which highly educated and well-heeled poets from the city idealized the lives of the poorest people in the land. It implied “a beautiful relation between the rich and poor” by making “simple people express strong feelings…in learned and fashionable language.” From 1935 onward, no one would read Spenser’s The Shepheardes Calendar or follow Shakespeare’s complicated double plots without being aware of the class tensions and ambiguities between the cultivated author and his low-born subjects.

Library of Congress

‘Migrant Mother,’ Nipomo, California, 1936; photographs by Dorothea Lange. Her original caption for this photograph was ‘Destitute peapickers in California; a 32 year old mother of seven children. February 1936.’

Although shepherds and shepherdesses have been in short supply in the United States, versions of pastoral have flourished here. The cult of the Noble Red Man, or, as Mark Twain derisively labeled it, “The Fenimore Cooper Indian” (a type given to long speeches in mellifluous and extravagantly figurative English), is an obvious example. So is the heroizing of simple cowboys, farmers, and miners in the western stories of writers like Bret Harte, the movies of John Ford, and the art of Frederic Remington, Charles M. Russell, Maynard Dixon, and Thomas Hart Benton. Both Uncle Tom’s Cabin and The Grapes of Wrath might be read as pastorals in Empson’s sense. The chief loci of American pastoral have been the rural South and the Far West, while most of its practitioners have been sophisticated easterners for whom the South and West were destinations for bouts of adventurous travel. They went equipped with sketchpads and notebooks in which to record the picturesque manners and customs of their rustic, unlettered fellow countrymen.

Empson noted the connection between traditional pastoral and Soviet propaganda, with its elevation of the worker to a “mythical cult-figure,” and something similar was going on during the New Deal when the Resettlement Administration (which later morphed into the Farm Security Administration) dispatched such figures from Manhattan’s Upper Bohemia as Walker Evans and Marion Post to photograph rural poverty in the southern states. Like a Tudor court poet contemplating a shepherd, the owner of the camera was rich beyond the dreams of the people in the viewfinder, whose images were used by the government both to justify its Keynesian economic policy and to raise private funds for the relief of dispossessed flood victims, sharecroppers, and migrant farm workers. Some, though not all, of the photographers were, like Evans, conscious artists; their federal patrons, like Roy Stryker, head of the information division of the FSA, were unabashed propagandists who judged each picture by its immediate affective power and took a severely practical approach to human tragedy.

Of all the many thousands of photographs that came out of this government-sponsored enterprise, none was more instantly affecting or has remained more famous than Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother . Taken in February 1936 at a pea pickers’ camp near Nipomo, seventy miles northwest of Santa Barbara, it was published in the San Francisco News the following month, when it resulted in $200,000 in donations from appalled readers. In 1998, it became a 32¢ stamp in the Celebrate the Century series, with the caption “America Survives the Depression.” For a long while now, I’ve tried to observe a self-imposed veto on the overworked words “icon” and “iconic,” but in the exceptional case of Migrant Mother it’s sorely tempting to lift it.

The picture defines the form of pastoral as Empson meant it, and the closer one studies it, the more one’s made aware of just what a queer and puzzling business it is. A woman from the abyssal depths of the lower classes is plucked from obscurity by a female artist from the upper classes and endowed by her with extraordinary nobility and eloquence. It’s not the woman’s plight one sees at first so much as her arresting handsomeness: her prominent, rather patrician nose; her full lips, firmly set; the long and slender fingers of her right hand; the enigmatic depth of feeling in her eyes.

Even after many viewings, it takes several moments for the rest of the picture to sink in: the pervasive dirt, the clothing gone to shreds and holes, the seams and furrows of worry on the woman’s face and forehead, the skin eruptions around her lips and chin, the swaddled, filthy baby on her lap. As one can see from the other five pictures in the six-shot series, Lange posed two elder children, making them avert their faces from the camera and bury them in the shadows behind their mother, at once focusing our undistracted attention on her face and imprisoning her in her own maternity. It’s a portrait in which squalor and dignity are in fierce contention, but both one’s first and last impressions are of the woman’s resilience, pride, and damaged beauty.

Against all odds, she’s less a figure of pathos than of survival, as the inscription on the postage stamp accurately described her. In 1960, Lange said of the woman that she “seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it”—a nice instance of Empson’s “beautiful relation between the rich and poor”—which was not at all how her subject remembered the occasion.

In 1958 the hitherto nameless woman surfaced as Florence Thompson, author of an angry letter, written in amateur legalese, to the magazine U.S. Camera , which had recently republished Migrant Mother :

…It was called to My attention…request you Recall all the un-Sold Magazines…should the picture appear in Any magazine again I and my Three Daughters shall be Forced to Protect our rights…Remove the magazine from Circulation Without Due Permission…

Years later, Thompson’s grandson, Roger Sprague, who maintains a Web site called migrantgrandson.com, described what he believed to be her version of the encounter with Lange:

Then a shiny new car (it was only two years old) pulled into the entrance, stopped some twenty yards in front of Florence and a well-dressed woman got out with a large camera. She started taking Florence’s picture. With each picture the woman would step closer. Florence thought to herself, “Pay no mind. The woman thinks I’m quaint, and wants to take my picture.” The woman took the last picture not four feet away then spoke to Florence: “Hello, I’m Dorothea Lange, I work for the Farm Security Administration documenting the plight of the migrant worker. The photos will never be published, I promise.”

Some of these details ring false, and Sprague has his own interest in promoting a counternarrative, but the essence of the passage, with its insistence on the gulf of class and wealth between photographer and subject, sounds broadly right. “The woman thinks I’m quaint” might be the resentful observation of every goatherd, shepherd, and leech-gatherer faced with a well-heeled poet or documentarian on his or her turf.

It also emerged that Florence Thompson was not just a representative “Okie,” as Lange had thought, but a Cherokee Indian, born on an Oklahoma reservation. So, in retrospect, Migrant Mother can be read as intertwining two “mythical cult-figures”: that of the refugee sharecropper from the Dust Bowl (though Thompson had originally come to California with her first husband, a millworker, in 1924) and that of the Noble Red Man. There is a strikingly visible connection, however unnoticed by Lange, between her picture of Florence Thompson and Edward S. Curtis’s elaborately staged sepia portraits of dignified Native American women in tribal regalia in his extensive collection The North American Indian (1900–1930), perhaps the single most ambitious—and contentious—work of American pastoral ever created by a visual artist.

Gordonton, Person County, North Carolina, July 9, 1939. Lange wrote in her caption for this photograph, ‘Country store on dirt road. Sunday afternoon…. Note the kerosene pump on the right and gasoline pump on the left. Brother of store owner stands in doorway.’

Both Linda Gordon’s Dorothea Lange and Anne Whiston Spirn’s Daring to Look hew to the line that Lange suddenly became a documentary photographer in 1932, when she stepped out of her portrait studio at 540 Sutter Street in San Francisco’s fashionable Union Square and took her Rolleiflex out onto the streets of the Mission District, three miles away, where she began to photograph men on the ever-lengthening breadlines in the last year of Hoover’s presidency. But this is to underplay the importance of the pictures she took from 1920 onward when she accompanied her first husband, Maynard Dixon, on his months-long painting trips to Arizona and New Mexico.

Lange was twenty-four when they married in March 1920, Dixon twenty years older. She was still a relative newcomer to San Francisco, having arrived there from New York in 1918; marrying Dixon, she also embraced his nostalgic and curmudgeonly vision of the Old West. A born westerner, from Fresno, California, he stubbornly portrayed the region as it had been before it was “ruined” by railroads, highways, cities, Hollywood, and tourism. In his paintings, the horse was still the primary means of power and transportation in a land of sunbleached rock and sand, enormous skies, cholla, and saguaro cacti, with adobe as its only architecture and Indians and cowboys its only rightful inhabitants. Although Lange had already established herself as an up-and-coming portrait photographer in San Francisco, her pictures on these trips to the desert were so faithful to her husband’s vision of the West that one might easily mistake many of them for Maynard Dixon paintings in black-and-white.

So she caught a group of Indian horsemen, seen from behind, riding close together across a sweep of empty tableland; a line of Hopi women and a boy, clad in traditional blankets, climbing a rough-hewn staircase trail through the pale rock of the mesa; a man teaching his son how to shoot a bow and arrow; families outside their adobe huts; and somber, unsmiling portraits of Indians whose faces show the same weary resignation to their fate as the faces that Lange would later photograph on the breadlines and in migrant labor camps. It was among the Hopi and the Navajo that she picked up the basic grammar of documentary, with its romantic alliance between the artist and the wretched of the earth.

One photograph stands out from her travels in the Southwest: a radically cropped print of the face of a Hopi man, in which much darkroom cookery clearly went into achieving Lange’s desired effect. At first sight, it looks like a grotesque ebony mask, its features splashed with silver as if by moonlight. Its skin is deeply creased, its eyes inscrutable black sockets. In its sculptural immobility, it appears as likely to be the face of a corpse as of a living being.

Seeing the finished picture, no one would guess the raw material from which Lange made the image as she focused her enlarger in the dark. There’s an uncropped photo of the same man, obviously shot within a minute or two of this one, to be seen in the Oakland Museum of California’s vast online archive of Lange’s work, in which he’s wearing a striped shirt and a bead necklace strung with Christian crosses, and has his hair tied with a knotted scarf around his forehead. His face looks humorous and easygoing; he seems amused to be having his picture taken.

This is not the negative that Lange used for her print, but it’s so close as to be very nearly identical. For the mask-like portrait, she moved her camera a few inches to her right, so that the razor-edged triangular shadow of the man’s nose exactly meets the cleft of his upper lip, and lowered it to make him loom above the viewer. What is remarkable is how she transformed the merry fellow in high sunshine into the unsettling and deathly face of the print. It might be titled The Last of His Race , or, as Edward S. Curtis called one of his best-known photographs, The Vanishing Race . There is, alas, no record of what the subject thought of his metamorphosis into a gaunt symbol of extinction.

Linda Gordon’s substantial, cradle-to-grave biography of Lange is usefully complemented by Anne Whiston Spirn’s careful documentation of one year—1939—in Lange’s working life. Both books have their flaws, but between them they add up to a satisfyingly binocular portrait of the photographer as she traveled the ambiguous and shifting frontier between art, journalism, social science, and propaganda. Lange’s work is much harder to place than that of, say, Walker Evans, and so is her personality. If neither Gordon nor Spirn quite succeeds in bringing her to life on the page, they do convey her complex and mercurial elusiveness. Roy Stryker of the FSA, who worked closely with Lange from 1935 through 1939, repeatedly sacking then rehiring her, vastly admired her photographs but found her maddening to deal with, and readers of Gordon and Spirn are likely to find themselves similarly conflicted.

Gordon, a social historian at NYU, whose faculty bio says that she specializes in “gender and family issues,” is best at placing her subject within the context of the various milieus in which she moved. She is good on the artistic and photographic scene in New York in the Teens of the last century, where the young Lange discovered Isadora Duncan, Alfred Stieglitz, and the luminaries of the Pleiades Club, and excellent on the rowdier bohemian coterie that she joined in San Francisco in the Twenties, where she met Dixon (in his customary urban uniform of Stetson and spurred cowboy boots), Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Frida Kahlo, and Diego Rivera. Gordon is reliably lucid on the aesthetic and political movements of the time, though Lange herself too often remains more cipher than character in an otherwise vivid picture of her place and period.

It’s in the gender and family issues department, her academic specialty, that Gordon is simultaneously confident and not entirely persuasive. Much is made of Lange’s childhood polio, which left her with a crippled right foot and permanent limp. Gordon calls her “a polio”—a grating phrase, which, according to Google, is rare but not without precedent. Further hurt was inflicted on Lange when her father moved out of the Hoboken house when she was twelve; and in writing of her as a wife and mother, prone to “hubris,” “irascibility,” “rages,” and “obsessive control,” Gordon portrays her as a damaged woman.

Lange acquired a stepdaughter, Consie, when she married Dixon, with whom she had two children of her own, Dan and John. In her second marriage, to the Berkeley economist Paul Taylor, she added three more stepchildren to her brood, in an age when women were expected to do all the work of parenting. Like so many people of their class and generation, the Dixons and the Taylors were in the habit of boarding out their kids whenever they threatened to interfere with their demanding work schedules. Not surprisingly, the children came to remember Lange as a domestic tyrant who neglected their needs and scarred them for life.

Autres temps, autres moeurs . Artists and writers were especially culpable in this regard, taking the line that their unique talents entitled them to days of concentrated silence and bibulous, grown-up, social evenings, undistracted by the barbaric yawps of the nursery. (Chief among Cyril Connolly’s Enemies of Promise was “the pram in the hall.”) Lange’s treatment of the children in her life was not egregiously different from that of others in her set in San Francisco and Taos, and Gordon’s nagging concern over her deficiencies as a parent tends to unbalance her book.

Although Gordon speculates freely about Lange’s thoughts and feelings, and surrounds her with an impressive mass of contingent details, one waits in vain to catch the pitch of her voice in conversation, her wit (did she have wit?), her personal demeanor and manners when at ease among friends. She emerges from the book more as a stack of interesting attributes than as a fully realized character in her own right.

Napa Valley, California, December 1938. Lange’s caption: ‘More than 25 years as a bindlestiff. Walks from the mines to the lumber camps to the farms. The type that formed the backbone of the IWW in California, before the war.Subject of Carleton Parker’s s

Where Gordon’s Dorothea Lange and Spirn’s Daring to Look coincide to happiest effect is on Lange’s marriage to Paul Schuster Taylor and her on-again-off-again work for Stryker at the FSA. Taylor, described by Gordon as “a stiff and slightly ponderous suit-and-tie professor” (she’s often sharper on her secondary characters than she is on her primary one), met Lange in 1934, shortly after her separation from Maynard Dixon, at an exhibition of her pictures of the San Francisco poor at a gallery in Oakland. Later that year, he hired her, at a typist’s salary, as the official photographer for the California Division of Rural Rehabilitation, of which he’d just been appointed field director. From January 1935, they were traveling together across California, visiting enormous, featureless agribusiness farms, worked by mostly Mexican migrant laborers. Taylor, who’d learned Spanish for the purpose, conducted interviews while she took photos. She took to calling him Pablo, he called her mi chaparrito (“my little shorty”). They were married in December.

Much as she’d learned to see the uncultivated West through Maynard Dixon’s eyes, and to frame her pictures like Dixon paintings, in Taylor’s company she acquired the mental habits of a painstaking social anthropologist. Taylor taught economics at Berkeley, but his avidity for human data took him far outside the usual confines of his discipline and into the “field,” where he transcribed the life stories of migrants. Lange copied him. A shy man, Taylor would introduce himself to groups of Mexicans by saying that he was lost and needed directions, a technique quickly adopted as her own by Lange. Soon after they’d met, she began to accompany her photographs with what she called “captions”—crisply detailed accounts, some running to essay length, of the circumstances that had led each subject to his or her present situation.

For Stryker at the FSA, the picture was the thing, and he spiked all, or nearly all, of her writing; in Daring to Look , Spirn reunites Lange’s 1939 photos with their original texts in a long-overdue act of restoration. The captions are rich in themselves, full of the dollars and cents of anguished household accounting, stories of escape from starved-out Dustbowl farms in rattletrap Fords, and snatches of talk, for which Lange had a fine ear; as a North Carolina woman told her, “All the white folks think a heap of me. Mr. Blank wouldn’t think about killing hogs unless I was there to help. You ought to see me killing hogs at Mr. Blank’s!” She was a patient listener, and relentlessly inquisitive. Photographing tobacco farmers, for instance, she became expert on how the plant was cultivated, harvested, cured, and sold, and her captions describe with great precision what was meant by such terms as “topping,” “worming,” “sliding,” “priming,” “saving,” “putting in,” “yellowing,” “killing out.”

Gathering this sort of information from her subjects changed the way she photographed them. Before 1935 and her collaboration with Taylor, she was a fly-on-the-wall observer in her pictures of Native Americans and the unemployed. After 1935, her photographs reflect an increasingly intimate relationship between the woman behind the camera and the person in front of it. One sees a new candor and engagement in her subjects’ faces, as if each shutter-click has momentarily interrupted an absorbing conversation. In this respect, Migrant Mother is quite atypical of Lange’s FSA work: she spent only a few minutes with Florence Thompson, and her caption is unusually brief (according to Thompson’s grandson, it was also riddled with errors of fact).

The deepening involvement in her subjects’ lives seems all the more impressive when one follows the hectic itinerary of her own life in Daring to Look . Between January and October 1939 she traveled far and wide through the states of California, North Carolina, Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, spending weeks at a time in her car, documenting the trudging “bindlestiffs” and homeless families on Highway 99, the labor camps and mile-wide fields of factory farms in the California valleys, tobacco in North Carolina, “stump farms” on logged-over forest in the Pacific Northwest, the newly irrigated orchards and farms of the Columbia basin. Wherever she went, she attached individual faces and stories to the desolate social geography of American agriculture from coast to coast. Spirn’s book is redolent of the hot and dusty unpaved roads on which Lange drove by day, and of inadequately lit rooms in cheap motels, where she wrote up her captions in the evenings.

Bad as her relations with Stryker were, she made her best pictures for the FSA. The current of indignant political feeling that flows through her work was in tune with the agency’s propagandist mission, and—more than Evans, Ben Shahn, Marion Post, and other FSA photographers—Lange had an increasingly deep knowledge and understanding of what she was seeing, as a result both of her own searching interviews with her subjects and of her husband’s work on the inequities of the agricultural economy. * Time and again, she struck a perfect balance between photographing a mass plight and honoring the dignity of each singular life—a balance she never quite recaptured again. Her 1942–1943 series on Japanese internment, for instance, has ample indignation, but lacks the active and visible rapport that she made with the farmworkers.

In 1954, Lange snagged a commission from Life magazine to do a photo-essay on Ireland, and around 2,500 negatives survive from this trip, which she made with her son Dan, then twenty-nine and an aspiring writer. Daniel Dixon was assigned the job of interviewing subjects and composing captions, leaving her free to concentrate entirely on photography. The results of this unwise division of labor are revealing.

Oakland Museum of California

County Clare, Ireland, 1954; photograph by Dorothea Lange

In County Clare, Lange was an enchanted tourist. After the barbed wire and vast flat landscapes of Californian agribusiness, she reveled in the small, irregular, hillocky Irish fields, their rainwashed drystone walls and ancient hedges. Instead of improvised shack-towns and government-built camps, she focused on stone bothies overhung with thatch and streets of single-storey terraced cottages with rickety horse-drawn traps parked at their doors. She stopped to take shots of ruined churches; placid, grazing cows; horses and haywains; old men with scythes; shepherds tending their flocks in the fields and driving them down narrow lanes. In Lange’s Ireland, almost everybody’s smiling, and her photographs form an archive of 1950s toothless, gap-toothed, and prosthetic Irish grins. Yet there’s little hint of two-way rapport in the faces of these people, who appear to be saying “Cheese” to deferentially oblige the lady-visitor from America, as she roamed the countryside picturing its happy peasantry.

She hardly seemed to notice that the clothes of her Irish subjects were as tattered and patched as those of the poorest Okies. If she questioned why the farms and fields were so small, or why there were so many horses and so few machines, it doesn’t show in her photographs. She was here to discover Arcadia—a land of simple folk, content with their lot, going about their time-hallowed rustic occupations, equipped with the same rudimentary technology that had served them for centuries. In Ireland, Lange reverted to pastoral in its most naive and sentimental form. It’s tantalizing to wonder how she would have handled this assignment had the commission come from a social activist like Stryker instead of Henry Luce’s Life . Her photos were in perfect harmony with the conservative politics of the magazine: they extol the tranquillity of a society under the law of Nature, and of God.

The magazine savagely cut Lange’s essay, rejected Daniel Dixon’s captions, and supplied its own, including “serenely they live in age old patterns” and “THE QUIET LIFE RICH IN FAITH AND A BIT OF FUN.”

In the last chapter of Daring to Look , Anne Whiston Spirn drives along the routes taken by Lange in 1939. By 2005 the roads were generally improved but the housing and social conditions of agricultural workers on industrial farms were little changed, and Spirn found new rural slums on the sites of the old New Deal labor camps. A caption written by Lange in 1939 still holds broadly true:

The richer the district in agricultural production, the more it has drawn the distressed who build its shacktowns. From the Salt River valley of Arizona to the Yakima valley of Washington, the richest valleys are dotted with the biggest slums.

This is painfully evident in Washington state, where I live. Were Lange to return here with her camera seventy years on, it would not be a Rip Van Winkle experience so much as a numbing sense of déjà vu. The cities and suburbs would be unrecognizable to her, but the poverty in the countryside created by the corporate agricultural system would yield material for photographs identical to those she took in 1939. There are small, Spanish-speaking farm towns on the Columbia plateau where the average per capita income is still in the middling four figures.

In summer, migrant fruit pickers pile into the Columbia and Yakima valleys, living in camps little different, and hardly more affluent, than the one where Lange found Florence Thompson. And inventive new ways of being poor continue to emerge. In Forks, at the foot of the Olympic National Park, there are run-down trailer parks on the edges of the town, inhabited by “brushpickers,” mostly Guatemalan, who make a tenuous living by scavenging in the woods for the moss, ferns, beargrass, and salal used by florists around the world to add greenery to bouquets.

Migrant Mother has become the symbol of a now-remote decade, to which the passage of years has lent a period glow. Yet across the rural West the Great Depression is less a historical event than a permanent condition, which existed before the 1930s and is still there now, though it shifts from place to place and fluctuates in its severity. The warning in the rearview mirror applies here: the lives in Lange’s photographs for the FSA are closer than they may appear.

November 19, 2009

Subscribe to our Newsletters

More by Jonathan Raban

The letters of William Gaddis

October 10, 2013 issue

April 26, 2012 issue

David Foster Wallace’s unfinished novel

May 12, 2011 issue

Jonathan Raban's books include Surveillance , My Holy War , Arabia , Old Glory , Hunting Mister Heartbreak , Bad Land , Passage to Juneau , and Waxwings . His most recent book is Driving Home: An American Journey , published in 2011. He is the recipient of the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Heinemann Award of the Royal Society of Literature, the PEN/West Creative Nonfiction Award, the Pacific Northwest Booksellers' Award, and the Governor's Award of the State of Washington. He is a frequent contributor to The New York Review of Books , The Guardian, and The Independent . He lives in Seattle.

Taylor and Lange merged their talents in An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion , published in 1939. The couple assembled her photographs, his text, and their captions, working together, as they wrote, “in every aspect of the form as a whole to the least detail of arrangement or phrase.” ↩

The Romantic Pugilist

February 27, 2003 issue

Invisible Cities

August 16, 1990 issue

Classical Tourism

September 10, 1964 issue

E.H. Gombrich (1909–2001)

December 20, 2001 issue

February 6, 1964 issue

The Mighty Penn

The Affair of the Chinese Bronze Heads

May 14, 2009 issue

May 18, 1978 issue

Subscribe and save 50%!

Get immediate access to the current issue and over 25,000 articles from the archives, plus the NYR App.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

- Member Login

- Library Patron Login

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR

FREE NEWSLETTERS

Search: Title Author Article Search String:

Reviews of American Pastoral by Philip Roth

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

American Pastoral

by Philip Roth

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' Opinion:

- Literary Fiction

- Mid-Atlantic, USA

- 1960s & '70s

- Mid-Life Onwards

- Jewish Authors

Rate this book

Buy This Book

About this Book

- Reading Guide

Book Summary

A magnificent meditation on a pivotal decade in our nation's history, is in every way different from the profane and sclerotic antihero of Sabbath's Theater.

As the American century draws to an uneasy close, Philip Roth gives us a novel of unqualified greatness that is an elegy for all our century's promises of prosperity, civic order, and domestic bliss. Roth's protagonist is Swede Levov, a legendary athlete at his Newark high school, who grows up in the booming postwar years to marry a former Miss New Jersey, inherit his father's glove factory, and move into a stone house in the idyllic hamlet of Old Rimrock. And then one day in 1968, Swede's beautiful American luck deserts him. For Swede's adored daughter, Merry, has grown from a loving, quick-witted girl into a sullen, fanatical teenager—a teenager capable of an outlandishly savage act of political terrorism. And overnight Swede is wrenched out of the American pastoral and into the indigenous American berserk. Compulsively readable, propelled by sorrow, rage, and a deep compassion for its characters, this is Roth's masterpiece. Winner - Pulitzer Prize.

The Swede. During the war years, when I was still a grade school boy, this was a magical name in our Newark neighborhood, even to adults just a generation removed from the city's old Prince Street ghetto and not yet so flawlessly Americanized as to be bowled over by the prowess of a high school athlete. The name was magical; so was the anomalous face. Of the few fair-complexioned Jewish students in our preponderantly Jewish public high school, none possessed anything remotely like the steep-jawed, insentient Viking mask of this blue-eyed blond born into our tribe as Seymour Irving Levov. The Swede starred as end in football, center in basketball, and first baseman in baseball. Only the basketball team was ever any good - twice winning the city championship while he was its leading scorer - but as long as the Swede excelled, the fate of our sports teams didn't matter much to a student body whose elders, largely undereducated and overburdened, venerated academic ...

Please be aware that this discussion guide will contain spoilers!

- "Beyond the Book" articles

- Free books to read and review (US only)

- Find books by time period, setting & theme

- Read-alike suggestions by book and author

- Book club discussions

- and much more!

- Just $45 for 12 months or $15 for 3 months.

- More about membership!

Media Reviews

Reader reviews.

Write your own review!

Read-Alikes

- Genres & Themes

If you liked American Pastoral, try these:

by Jonathan Franzen

Published 2022

About this book

More by this author

Jonathan Franzen's gift for wedding depth and vividness of character with breadth of social vision has never been more dazzlingly evident than in Crossroads .

The Wonder Garden

by Lauren Acampora

Published 2016

Deliciously creepy and masterfully complex The Wonder Garden heralds the arrival of a phenomenal new talent in American fiction.

Books with similar themes

Support bookbrowse.

Join our inner reading circle, go ad-free and get way more!

Find out more

BookBrowse Book Club

Members Recommend

The Divorcees by Rowan Beaird

A "delicious" debut novel set at a 1950s Reno divorce ranch about the complex friendships between women who dare to imagine a different future.

The Mystery Writer by Sulari Gentill

There's nothing easier to dismiss than a conspiracy theory—until it turns out to be true.

The Day Tripper by James Goodhand

The right guy, the right place, the wrong time.

Who Said...

Any activity becomes creative when the doer cares about doing it right, or better.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Solve this clue:

and be entered to win..

Your guide to exceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Subscribe to receive some of our best reviews, "beyond the book" articles, book club info and giveaways by email.

April 20, 1997 The Trouble With Swede Levov By MICHAEL WOOD Philip Roth's new hero gets everything he dreamed of More on Philip Roth from The New York Times Archives American Pastoral By Philip Roth. 423 pp. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. $26. ho would have thought Nathan Zuckerman would fall in love with normality, with the all-American life? With the old idea of the melting pot as order and progress, a pacified history in which resentment and misunderstanding fade away across the generations? With Thanksgiving as a form of ethnic truce, where the Jews and the Irish hang out together as if no one had ever crucified anyone? This is, after all, the garrulous, manic hero of five Philip Roth novels, and the subtle fictional critic of Mr. Roth's autobiography, ''The Facts.'' His alter id, as you might say, the man whose business is to get out of control and give offense. ''I am your permission,'' Zuckerman tells Mr. Roth in that book, reproving him for lapsing into the tame decencies of the uninvented life, ''your indiscretion, the key to disclosure.'' ''The distortion called fidelity is not your metier,'' Zuckerman insists. And Mr. Roth himself says he is pleased to have escaped the constrictions of the Jamesian tact and elegance he once admired, liberating his talent for what he calls ''extremist fiction.'' Yet here is Zuckerman attending a class reunion of veterans from Weequahic High in Newark , checking out the prostates and remarriages and high-powered jobs and the dead fathers; having dinner in New York with a former star athlete from the same school, a nice guy called Seymour Levov, alias the Swede, and wondering at the fellow's sheer likable ordinariness. ''Swede Levov's life, for all I knew, had been most simple and most ordinary and therefore just great, right in the American grain.'' The little clause (''for all I knew'') gives the game away. Of course Zuckerman is wrong about this -- there wouldn't be a novel here if he weren't, let alone a Philip Roth novel. ''I was wrong,'' Zuckerman says handsomely. ''Never more mistaken about anyone in my life.'' But what's interesting about the book is that Zuckerman could have thought, even for an instant, that he was right; and that we can't, in the end, know how right or wrong he is, since he is making everything up, dreaming ''a realistic chronicle,'' as he says, quoting the old Johnny Mercer song (''Dream when the day is through''), and taking off into history as he imagines it. It's true that the imagining is grounded in the most meticulous reconstructions of old times and places -- the Levov family glove factory, the spreading acres of west New Jersey, a Miss America competition in Atlantic City, the beat-up neighborhoods of what used to be the city of Newark -- and it gets easier and easier to forget that Zuckerman's industry and imagination are providing all this. He gives us plenty of clues, though, before he vanishes for good on page 89, off into fiction, in the middle of a dance with an old schoolmate named Joy Helpern. ''You get them wrong before you meet them,'' Zuckerman says of ''people'' in general, ''while you're anticipating meeting them; you get them wrong while you're with them; and then you go home to tell somebody else about the meeting and you get them all wrong again.'' How could the writer of fiction be exempt from this contagion? Zuckerman/Roth would reply that there is no exemption; only the need, whether you're a novelist or not, to keep imagining other people, and the hope that guesses may give life to the dead and the fallen and the lost. Zuckerman attributes his attachment to the romance of ordinariness to a cancer scare of his own, but he offers a subtler diagnosis in ''The Facts.'' ''The whole point about your fiction (and in America, not only yours),'' he tells Mr. Roth, ''is that the imagination is always in transit between the good boy and the bad boy -- that's the tension that leads to revelation.'' Swede Levov is the good boy for whom life is just great -- except that he's not. He is the good boy whose life turns to disaster -- as if that's what good boys were for, and only the bad boys go free. Or he is the good boy whom Zuckerman can imagine and mourn for only in this way. Swede is alive when the story opens, dead soon after. Zuckerman picks up a few details of his life at the reunion, notably from Swede's ferocious brother, a bullying cardiac surgeon in Miami. The rest is his dreamed chronicle. In and out of Zuckerman's mind the story hinges on Swede's 16-year-old daughter, Merry, an only, pampered child, who has fallen in with a section of the Weathermen and blown up a rural post office, killing a doctor who happened to be mailing his bills. The time is 1968. Merry goes into hiding, is raped and becomes destitute, gets involved in further bombings in Oregon, winds up back in Newark, stick-thin, filthy, a veil over her face, having become a Jain, dedicated to such extremes of nonviolence that she can scarcely bring herself to eat because of the murder of plant life involved. The novel stages an encounter between Swede and his derelict-looking daughter, and the scene manages to be both shocking and discreet. But the novel revolves not so much around this scene as around what Merry has done, the deaths she has caused, and the absurd, irresistible question of how this respectable Jewish athlete and his Irish, former-Miss-New-Jersey wife could have given birth to this once angry, now dislocated, apparently reasoning, weirdly unthinking girl. The question can't be answered, of course, but causalities keep shaping themselves in the mind. Is it because the parents are so respectable, so decent and so liberal, as much against the war in Vietnam as their daughter, that the girl has to turn out this way? Is there an American allegory here, immigrant generations rising to prosperity only to fall into violence and despair? Or have the parents done everything they can and should have, and is it Merry the changeling who reminds us that the inexplicable exists? ''And what is wrong with their life?'' the novel ends. ''What on earth is less reprehensible than the life of the Levovs?'' This is an answer to Zuckerman's own merciless portrait of the (female) intellectual who laughs with delight at the sight of historical disorder, ''enjoying enormously the assailability, the frailty, the enfeeblement of supposedly robust things.'' But the answer itself still seeks to moralize the wreck of a world, as if Zuckerman had never heard of Job, as if the Levovs' virtue ought really, after all, to have been a protection for them, rather than an invitation to damage. ''American Pastoral'' is a little slow -- as befits its crumbling subject, but unmistakably slow all the same -- and I must say I miss Zuckerman's manic energies. But the mixture of rage and elegy in the book is remarkable, and you have only to pause over the prose to feel how beautifully it is elaborated, to see that Mr. Roth didn't entirely abandon Henry James after all. A sentence beginning ''Only after strudel and coffee,'' for instance, lasts almost a full page and evokes a whole shaky generation, without once losing its rhythm or its comic and melancholy logic, until it arrives, with a flick of the conjuror's hand, at a revelation none of us can have been waiting for. Because both novels are hefty and self-consciously American, trying to rethink national history, because both deal in painstaking and slightly mind-numbing realism, because both begin in New Jersey and end in hell, ''American Pastoral'' invites comparison with John Updike's ''In the Beauty of the Lilies.'' The chief difference is that Mr. Updike's novel ends in a secular apocalypse, the last act in the story of the death of a Christian God, while Mr. Roth's ends in the imagination of ruin, the death of a Jew's dream of ordinariness. The difference is not extreme, although both stories are. Michael Wood is the author of ''The Magician's Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction.'' He teaches at Princeton University. More on Philip Roth From the Archives of The New York Times Review of " Goodbye, Columbus " (1959) Review of " Letting Go " (1962) Review of " Portnoy's Complaint (1969) Review of " Portnoy's Complaint " by Christopher Lehmann-Haupt Philip Roth Shakes Weequahic High (February 29, 1969) Review of " The Ghost Writer (1979) Review of " Zuckerman Unbound " (1981) " The Book That I'm Writing " (1983), Philip Roth on "The Anatomy Lesson" Review of " The Anatomy Lesson " (1983) " Roth's Real Father Likes His Books " (1983), by Maureen Dowd " Conversations with Philip " (1984), by David Plante Review of " Zuckerman Bound: A Trilogy and Epilogue " (1985), by Harold Bloom Review of " The Counterlife (1987), by William Gass Review of " The Facts: A Novelist's Autobiography " (1988), by Justin Kaplan " What Facts? A Talk with Roth " (1988) Review of " Deception (1990), by Fay Weldon Review of " Patrimony " (1991), by Robert Pinsky " To Newark, With Love. Philip Roth. " (1991) " Dear Dirty Dublin: My Joycean Trek with Philip Roth " (1991) by William Styron " Roth Returning to Newark to Get History Award " (1992) Review of " Operation Shylock " (1993), by D. M. Thomas Review of " Sabbath's Theater " (1995) " Claire Bloom Looks Back in Anger at Philip Roth " (1996) Review of Claire Bloom's memoir, " Leaving a Doll's House " (1996) Return to the Books Home Page

American Pastoral by Philip Roth (1997) Vintage (1998) 432 pp

I ‘m hooked. The more Roth I read the more I’m convinced he is the greatest American writer alive today (and there are several great ones). But Roth — Roth’s books are in another league. Freshly finished with The Prague Orgy (the last book in what Vintage calls “Zuckerman Bound” containing The Ghost Writer , Zuckerman Unbound , The Anatomy Lesson , and The Prague Orgy ) I decided to not move on to his latest “Zuckerman” novel, Exit Ghost , published last year. Instead I chose to finally read Roth’s Pulitzer Prize winner: American Pastoral . American Pastoral also — and I was so happy — includes one of my newest favorite literary characters of all time, Nathan Zuckerman, albeit in a different role.

While “Zuckerman Bound” and Exit Ghost are written about Nathan Zuckerman, American Pastoral is written by Nathan Zuckerman, creating a sophisticated and effective framing devices. The first section, “Paradise Remembered,” is Zuckerman’s reflection on how this book came about. It’s a beautiful introduction to the themes of the novel that are displayed and flayed and displayed again in a different light and then stripped down with stunning compassion which leads to chilling effects in the last two parts, “The Fall” and “Paradise Lost.”

Zuckerman has aged a little more than a decade since I last visited him (only a month ago) in The Prague Orgy . It’s his forty-fifth-year high school reunion. Events and encounters lead him to reflect on his youth and, in particular, on his boyhood hero: Seymour “the Swede” Levov. The Swede is among the generation of Jews who were finally able to take full advantage of what America offered; he is descended from immigrants who had nothing, from a second-generation Jewish family that started building up a foundation, and from a father who has built a successful glove making factory. His grandfather and then his father had to work hard, and now the Swede is set up for an easy life; he even takes on the physical features of an all-American boy. Zuckerman idolized the Swede. He was the perfect athlete who was raised to an even higher status since he was enacting these great athletic feats while the country engaged in World War II. As is usual with Roth (but he still surprises me with his ability), the narrative looks at the Swede’s status from many angles: as a blessing, as an insignificant fact, as a piece of nostalgia, and as a curse.

And it all began — this heroically idealistic maneuver, this strategic, strange spiritual desire to be a bulwark of duty and ethical obligation — because of the war, because of all the terrible uncertainties bred by the war, because of how strongly an emotional community whose beloved sons were dying far away facing death had been drawn to a lean and muscular, austere boy whose talent it was to be able to catch anything anybody threw anywhere near him. It all began for the Swede — as what doesn’t? — in a circumstantial absurdity.

Zuckerman has seen the Swede a few times since childhood, and he’s still struck with awe, still a little giddy. One day not long before the high school reunion Zuckerman receives a letter from the Swede asking him to meet him in a New York City restaurant. The Swede’s father has died, and the Swede actually wants Zuckerman to consider helping him write a piece about his father. While Zuckerman would never do such a thing for another person, he is too intrigued by the Swede to say no. Zuckerman hopes to get under the surface of this apparently perfect man who has lived an apparently ideal life.

Only . . . what did he do for subjectivity? What was the Swede’s subjectivity? There had to be a substratum, but its composition was unimaginable. That was the second reason I answered his letter — the substratum. What sort of mental existence had been his? What, if anything, had ever threatened to destabalize the Swede’s trajectory?

Zuckerman, trying to see beneath the at once humble and complacent veneer, is disappointed. Turns out that at the dinner the Swede doesn’t even go into the piece he wants written about his father. They pass a dull evening together, and Zuckerman, in a sense, gets over the Swede. There is nothing going on under the surface. Unless . . .

Unless he was not a character with no character to reveal but a character with none that he wished to reveal — just a sensible man who understands that if you regard highly your privacy and the well-being of your loved ones, the last person to take into your confidence is a working novelist. Give the novelist, instead of your life story, the brazen refusal of the gorgeous smile, blast him with the stun gun of your prince-of-blandness smile, then polish off the zabaglione and get the hell back to Old Rimrock, New Jersey, where your life is your business and not his.

He knows nothing more about the Swede, however, until the high school reunion comes around. There he runs into the Swede’s younger brother, Jerry. Only a bit of information is passed from Jerry to Zuckerman, but it’s enough. A tidbit about the Swede’s daugher shows Zuckerman how wrong he was to pass off the Swede as just another superficial human being, too ideal to be interesting. As happens at large reunions, Jerry and Zuckerman are separated before Zuckerman can satisfy his curiosity any further.

Though Zuckerman has little to go on, he delves into writing a book about the Swede’s life, focusing on the period of the 1960s and Vietnam and the early 1970s with Watergate, when, he postulates, the Swede’s daughter has most destabalized not only his life but the life of his wife, the neighbors, the community, and the United States. It is a fantastic, virtuosic plummet into the heart of America.

I can’t remember a book that caused a more visceral reaction to me. Roth does not pull punches, and he is not shy about making the reader feel complicit. Because of this, I can’t say I’d recommend American Pastoral to everyone despite the fact that I consider it one of the greatest novels of the last century. It deserves to be looked at with an open mind and with an understanding that Roth is not putting anything in here for gratuitous effect, and the effect is often devastating. I swear, when the Swede encounters Rita Cohen to pass information to Merry I felt like I was there. My mouth went dry. Like the Swede, I too wanted to run out of the room I was in. I felt like the Swede, and I admired Roth even more for his ability to do that. Indeed, Roth, more than any other writer I know of, has the ability to pull me into the emotions the characters are feeling. I feel transported, like the Swede:

The daughter who transports him out of the longed-for American pastoral and into everything that is its antithesis and its enemy, into the fury, the violence, and the desperation of the counterpastoral — into the indigenous American berserk.

Another striking aspect of the novel is its treatment of Newark, a city I’m drawn to since I spent a summer working as a judicial intern in the Federal Court, which sits right in the area described in the novel, and I still frequent Newark’s streets. Roth, like Zuckerman and the Swede, grew up in Newark in a time when it had a better reputation. Here we get a gritty, up close shot of the city following the ugly and destructive riots of 1967; forty years later, these riots still affect the city and its abysmal reputation. Over the past few years, Newark has been attempting to revitalize itself. It has a classy performing arts center and a brand new state-of-the-art stadium. The homicide rate is dropping, finally. But this scene is still familiar:

Along this forsaken street, as ominous now as any street in any ruined city in America, was a reptilian length of unguarded wall barren even of graffiti. But for the wilted weeds that managed to jut forth in wiry clumps where the mortar was cracked and washed away, the viaduct wall was barren of everything except the affirmation of a weary industrial city’s prolonged and triumphant struggle to monumentalize its ugliness.

The book doesn’t dwell in the urban areas, though. The Swede has moved from Newark to the rural community of Old Rimrock. It’s a stark contrast: Newark is primarily inhabited by Democrats and immigrants, Jewish or Catholic; Old Rimrock is primarily Republican and inhabited by wealthy WASPs. The Swede’s generation was one of the first to change these stereotypes. With his Irish Catholic wife, the Swede moves thirty miles west of Newark, and allows Roth to explore yet another side of America.

I’ll admit that my proximity to the landscape has made me like this book more than I perhaps would have otherwise, as I suspect is the case with Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland . Still, American Pastoral is more layered than the clichéd onion. In many ways, that layering is the major motif in the novel: there are glove factories, face-lifts, paintings that look like their painters were trying to “rub out” the paint rather than apply it. We see it in the narrative structure which has a fictional author writing a fictional account about a real person. We see it in the way Roth plays with the layers of time. We see it in the layers of meaning in each scene. This is an intimate look at a family that spreads out into an astounding discussion of America and her history.

Share this:

- American Pastoral " data-content="https://mookseandgripes.com/reviews/2008/09/07/philip-roths-american-pastoral/" title="Share on Tumblr">Share on Tumblr

Related Posts

Alice Munro: The View from Castle Rock

Alice Munro: “Silence”

Pat Barker: The Women of Troy

Barbara Pym: Excellent Women

César Aira: The Divorce

Jack Spicer: After Lorca

45 comments.

I am planning at some point to write something extensive about this novel, as I think it’s the best work of fiction I’ve read in the last five years. I read it last October as a part of a Jewish Literature series that we were holding at the library during the fall, and a full year later I still find myself going back to it to reread chosen passages, and thinking about these characters and their shattered illusions. The framing device of using Nathan to tell the Swede’s story has become more poignant now that I’m working through those early Zuckerman novels. And of course reveling in the writing, which as you point out, is just in another league. I’ll let you know when I write this manifesto, but for now it’s enough to say that I couldn’t agree more with your assessment.

Very interesting, Trevor. I read American Pastoral a few years ago, before I’d read any other Zuckerman books and after I’d read a couple of Roths which hadn’t exactly wowed me (though, having acquired the taste for him, they probably would now). This was the book which made me realise how great he could be. I expect if (or when) I reread it, it’ll move up to one of the highest positions in my Hall of Roth.

Worth mentioning the last lines, which I think in their way are as fine and beautifully put as any last lines I’ve read (and which don’t, I believe, constitute a spoiler):

And what is wrong with their life? What on earth is less reprehensible than the life of the Levovs?

I’m thinking of giving The Counterlife , or perhaps Patrimony , a go next.

An intriguing review, as usual, Trevor. I read American Pastoral in a single go with the other parts of the trilogy, I Married a Communist and The Human Stain. And I find I remember the other two better than this book — although your review convinces me that I need to return to American Pastoral soon. I may have made a mistake in reading the whole trilogy at once — your review indicates to me that this book is quite a bit more subtle than the other two. Just as you wonder how much your own experience with Newark influenced your reaction to this book (quite a bit, I think — and I don’t mean that as a criticism), the politics of the other two books probably made them more accessible for me.

Along that line, Booker-longlisted Linda Grant wrote a fascinating — and very critical — review of I Married a Communist in The Guardian, Oct. 3, 1998, which expands into some more general thoughts about Roth. While it is somewhat of a polemic, it is worth tracing down for a read because I do think she makes some quite legitimate points about Roth, even if they are over-stated. I also found the review relevant to some of the themes that are found in The Clothes on Their Backs.

Here is the Linda Grant piece which Kevin refers to. I shall skip it for now, as I have I Married a Communist on my Roth shelves to come to in due course. However I couldn’t help catching this sentence in passing:

I don’t know that anyone understands more about men than Philip Roth, or less about women.

Michael, I look forward to your “manifesto.” I need to get down to the library soon to find out what’s going on. And if you’re interested, when Indignation comes out on September 16, the Barnes & Noble in Tribeca will be broadcasting some kind of Philip Roth appearence. I guess that’s the next best thing to an actual appearence.

Kevin and John, before I go on to the next two books in this “trilogy” I’m going to take a step back and read The Counterlife . I kind of like seeing Nathan Zuckerman at the different points of his life, and don’t quite want to move on until I get him in the early 1990s.

I haven’t read the Linda Grant piece yet, Kevin, but I’m anxious to. I’m not sure I want her to spoil my experience with the next few books, though. Still, I’m definitely interested in that perspective, which, after seeing the quote John pulled, I am not qualified to rebut.

I think you are right about going back in the Zuckerman series rather than going forward. I also think this late trilogy requires some pausing between books and that I made a mistake in not taking that time.

I wouldn’t worry about the Grant piece spoiling the books — it is in fact more about Roth as a writer than about the particular book. She raises some very interesting contextual points about Roth(and certainly says he should be read) that you can either accept or reject (John’s selected quote is a good example — I don’t think it spoils the books). I don’t necessarily agree with Grant’s conclusions — I do think her observations about Roth are definitely worth considering.

I took your advice and read the review, Kevin. Very interesting. And you’re right – I don’t think it spoils Roth for me.

To pull another quote:

Opening the first page of any Philip Roth is like hearing the ignition on a boiler roar to life. Passion is what we’re going to get, and plenty of it.

On a side not, today I took a drive to the Weequahic section of Newark where the Swede grew up. It’s very interesting to see the old-style homes that look quite rundown. I talked to a few of the people who lived there and they mentioned that many in the community are addicts. As I drove away there were full streets of boarded up, gutted out buildings. Still not there.

I went back to this review today after the Booker shortlist was announced (I know that’s a stretch, keep reading and I’ll explain). I think Trevor’s review contains something that is all too rare in reviews and needs to appear more often — an acknowledgement that personal experience with the geography or context of the book has significantly affected the final judgment.

I’ve never been to Newark so Roth’s references are interesting but have no context. On the other hand, when I look at the “loose” trilogy that this book introduces, I read The Human Stain while visiting a sociology professor friend in Amherst — not the Berkshires, but very close, and surrounded by academics in what might be the world’s best centre of liberal arts colleges.

I think The Human Stain a much better book than American Pastoral, but how much did the circumstances of when and where I read it affect me? A lot, I suspect. And when I reread American Pastoral, I will keep Trevor’s thoughts — and the fact he went back to Newark on the weekend (I do love that touch, although I share his disappointment) in mind. I know reviewers don’t like to insert themselves in the review, but sometimes they have to. This review is a perfect example of how to do that.

Obviously a good book should transcrend the personal life of the people who read it. Equally obviously, however, reviewers have to admit that they know what they know and they can’t deny their personal experiences which influence their judgement. This review does a very good job of showing how to do that.

As for the Man Booker (I promised that above is this very long post), I hated The Northern Clemency but a dovegreyreader post has caused me to at least be careful about expressing my opinion: she said (the quote is an impression not for certain) “maybe you had to be there”. I wasn’t there and I certainly acknowledge that maybe if I was this is a better book. That doesn’t make it a great book by any means — just means I should adjust my opinion, as I would of American Pastoral now that I know what someone who knows the territory thinks.

I really like The Clothes on Their Backs by Linda Grant. I also first visited London in 1975 as a 27-year-old Canada journalist, following the Premier of Alberta, on a European tour. I returned the next year as an excited tourist (and London to this day remains my favorite city to visit). I spent the summer of 1979 based in London as a Commonwealth Press Union fellow. Linda Grant’s book speaks to my experience of discovering a wonderful city in this, for me, wonderful city — does that make it a less or better book?

And finally, Trevor, could I talk you into reading an Annie Dillard book for the blog sometime in the future ? As a pure writer, I would include her in my “greatest living Americans” list and I think she tends to get overlooked (more in the Stegner-Williams rather than Roth-Bellow-Updike(?) tradition). I lived in Pittsburgh from 2000 to 2003 so I would most like to see your thoughts on An American Childhood (and I generally hate memoirs), but anything that strikes your interest would be welcome.

Sorry for another very long post, but when a reviewer sparks interesting thoughts that go beyond the review he/she has to expect them.

KevinfromCanada

I know Stegner, Kevin, but who is the Williams you compare Dillard with?

John Edward Williams may be the most overlooked novelist in American history. Born in Texas in 1922, he spent most of his life at the University of Denver (not a category A school in any category, football, writing, you name it) teaching creative writing. A poet (sorry I don’t read poetry, so no opinion), his entire work consists of four novels:

Nothing But Night, published I think in 1948 and he disavowed it so I’ve never read it. Butcher’s Crossing, pub 1960 now available from NYRB Classics, a great Stegner-like book about a buffalo hunt in the American West, just before the market for buffalo skins collapsed. If you do like Stegner, you like this book. If I remember you like The Outlander, so I think you would quite like this one.

Stoner, pub 1965 (also in the NYRB Classics series) — An academic novel, quite comparable in some ways to some of the great Oxford and Cambridge novels. Only this one concerns the son of a dirt-poor Missouri farmer who gets to go the state university (you can see where the Oxon comparison fades).

Augustus, pub 1973 (still in commerical publication in North America, not sure about the UK) — Picks up the Roman story where the TV series leaves off, even thought it was written 35 years before they thought of the TV series. An epistolatory, diary novel — totally different from the other two. Having said that, the friends that we lend our Rome DVDs to always want to read the novel. I do like this book — I think the other two are better.

Williams is an author whom it is impossible to classify and he didn’t really write enough to be in any pantheon. I do think you would find him interesting.

He obviously didn’t write a lot or follow a genre. All three are wonderful books.

John: Is there any chance you would take on an Annie Dillard book, or am I reaching? I’d love to see how someone from outside North America looks at her work.

Kevin, your lengthy comments are always welcome! I find the comments one of (if not the) most enjoyable part of blogging about books.

I have actually read An American Childhood . It’s been years, and I recently saw it in a bookstore and thought I needed to revisit it. Your request shall be granted! And fairly soon, I think.

And I agree about how location influences a book. I read the overly long The Executioner’s Song by Norman Mailer because I knew the locations in that book too. In fact, one day I was reading it in a car service station and found that I was at the exact address he was describing – creepy! I wouldn’t recommend that book to anyone because of its length, but I enjoyed it as a history of a community I knew.

I’m pulling An American Childhood off the shelf tomorrow — I’ve been looking for a non-contemporary book to read before the Giller longlist comes out and this is an excellent choice. If you change your mind and choose another Dillard, please let me know — I’d like to be up to date whenever you post a review. Cheers, Kevin

I tend to go through Roth phases; there have been times when I’ve read nothing else for weeks at a time, but I’ve had no interest in him lately (I even tried rereading The Human Stain a couple of summers ago, and didn’t finish it, although I loved it the first time I read it.) I’m not sure my experience is uncommon, so I’ll have to go back to him at some point and try to work out why that is.

he last book of his that I read was The Plot Against America , and that one didn’t quite work for me. Again, at this stage I’d have to go back to it to work out why.

Kevin, I did pull out An American Childhood last night, though I have two other book reviews coming up before it, so late next week I should get that one posted.

Rob, that’s interesting. I definitely think that his raw passion and the fantastic rants might make time away from Roth beneficial. But you’re the first person I’ve had say that The Plot Against America didn’t work. I haven’t read it yet. My next Roth will be either The Counterlife or Indignation , which gets published next Tuesday here in the U.S. After those two I plan to take a break for a while (we’ll see how long that lasts). I’m interested to know if Roth ever becomes pallatable for you again.

I’ll certainly be trying him again, sooner or later, so I’ll let you know!

I’d like to join Rob on the list of people who thought The Plot Against America didn’t work. Actually, I’m wondering whether a high opinion of Roth may be an American phenomenon that we don’t get in the rest of the world. I’ll keep wondering about that until your next Roth effort, Trevor, and promise to have an opinion by then.

Not massive on Roth either. I found ‘American Pastoral’ dense – rather overwrought. I was a little indifferent to The Plot Against America, although I wouldn’t go as far as to say it ‘didn’t work’. The only other one I can remember reading is ‘Portnoy’s Complaint’. A grubby, smutty sex comedy if I remember rightly, and very funny, but it doesn’t seem to warrant Roth the status he enjoys. I’d definitely give him another go, which is your favourite Trevor?

Kevin, I’ve wondered how well Roth travels to other nations. Seems every year when the Nobel Prize for literature is announced, there’s some discussion about whether it’s time for Roth. I have to say, I’ve rarely had as much pure joy in reading as when I was reading the first two Zuckerman books. I don’t think all of that was my proximity to New Jersey and New York, but I’m sure some of it was. I definitely appreciate comments from those of you who bring a different perspective to the books.

Demob Happy, I’m afraid to say that my experience with Roth is limited to the “Zuckerman Bound” books and American Pastoral and Everyman , so while I can pick my favorite, it might change when I’ve made it through the rest of his books. As for now I’ll give you my three favorites: The Ghost Writer , Zuckerman Bound , and American Pastoral . I think the most substantial of those is American Pastoral , and I had a different reaction to it than you did. I haven’t read The Plot Against America yet, but many of my friends (once again, those from New Jersey and New York) love it. I have a feeling I’ll enjoy it quite a bit too, especially since I find Lindbergh’s passifism fascinating already. We’ll see! Next on my shelf is The Counterlife .

Interestingly, a couple of years ago the New York Times asked “a couple hundred prominent writers, critics, editors, and other literary sages” (not all of whom are American) what “the single best work of American fiction published in the last 25 years” was. Beloved won, which is kind of expected though I didn’t warm up to it. American Pastoral was a runner-up. The crazy thing was that of the seventeen honorable mentions, five were by Philip Roth: The Counterlife , Operation Shylock , Sabbath’s Theatre , The Human Stain , and The Plot Against America . ( Here is the article.) So it does appear that here in America Roth has a very devoted following. How will his work hold up in the larger world as the years go by?

I’m intrigued enough by this issue that I promise a serious effort. I think I’ll start with a reread of American Pastoral, since your review provides some fresh context. Considering Sabbath’s Theatre and The Counterlife (neither of which I’ve read) as the rest of this stage of the project. And given my previous experience, I’ll be taking some time and leaving some space between various books.

I went to that Times article after my posting my last comment and can’t resist adding another one.